ABSTRACT

Over the last 25 years, a number of concepts that broadly centre on human suffering, conflict, and death have developed and proliferated in heritage studies. As a ‘trauma and truth telling’ discourse is embraced globally, there is a marked increase in the recognition of heritage connected to trauma, suffering and tragedy. Yet, despite the breadth and depth of research in this space, psychological trauma has been largely unexamined in the field of heritage studies. Therefore in this interdisciplinary paper, we ask: what is trauma? What is the relationship between trauma and heritage? And what does it mean to be trauma-informed? We introduce the concept of trauma-informed heritage (TIH) and suggest that heritage connected to traumatic events can be conceived as trauma-heritage (TH). Together, the TIH and TH concepts shine a light on heritage connected to trauma, which is multiplex and multiscalar. We offer this framework to better acknowledge and understand trauma and critically explore the relationships between trauma and heritage. This frame will provide awareness of the impact of trauma on people in the wake of traumatic events and help mitigate the risk of re-traumatising, now and for the future.

Trauma is not what happens to you. Trauma is what happens inside you, as a result of what happens to you (Maté Citation2021)

Over the last 25 years, research on ‘dissonant’ (Graham, Ashworth, and Tunbridge Citation2000; Tunbridge and Ashworth Citation1996a, Citation1996b), ‘negative’ (Meskell Citation2002), ‘difficult’ (Macdonald Citation2009), ‘dark’ (Lennon and Foley Citation2000), and more recently ‘displaced’ (Ian, Gerard, and Peter Citation2014) and ‘disaster’ (De et al. Citation2021) heritage has developed and proliferated. These concepts have featured in multitudes of publications exploring heritage that broadly centres on human suffering, conflict, and death. Subsequent discourse has examined the potential for heritage to facilitate ‘healing’, particularly in post-conflict environments (Cooke et al. Citation2020; Giblin Citation2014; Daly and Chan Citation2015; Ian, Gerard, and Peter Citation2014). While consensus over these concepts and their meanings remain an ongoing point of discussion, both within and between frames, they share a common thread. That is, they centre on heritage connected to traumatic events and therefore, all intimately entangle with human trauma. In this paper, we introduce the concept of trauma-heritage (TH). We use the concept as an agent of social activism in the heritage space, serving as a vehicle to emphasise the ethical responsibility of being trauma-informed and as a tool for doing trauma-informed heritage (TIH).

Heritage scholarship relating to traumatic events is broad and diverse. Case examples range from the intentional destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan (Janowski Citation2020; Manhart Citation2015; Meskell Citation2002; Nagaoka and Nagaoka Citation2020); and post-conflict reconstruction in Syria (Harrowell Citation2016; Munawar Citation2019); to the personal accounts from survivors of the 9/11 terrorist attacks (Micieli-Voutsinas Citation2021; Sather-Wagstaff Citation2011). However, heritage that is tied to tragedy and imbued with a sense of trauma can be conceived more broadly, for example, the heritage of Pompeii, the collapse of the Maya civilisation, the sinking of the Titanic, the Second World War, the Indonesian mass killings of 1965–66, the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, Indigenous massacre sites, the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami, the 2019–20 Australian Black Summer bushfires, the 2023 earthquake in Türkiye, ongoing processes of colonisation, homelessness, and the current Israeli war on Gaza. This list exemplifies the diversity, ubiquity, and varying scales of traumatic events connected with heritage, and therefore trauma, present in the past and currently unfolding in the now. While traumatic events such as these can serve as a tangible nexus to locate trauma, the effects of trauma are far more insidious and often less visible.

The scale and intensity of devastation caused by powerful, destructive events can be difficult to comprehend. Their toll on lives, livelihoods, and emotional well-being is both profound and complicated. They affect individuals, families, and communities and can result in trauma that extends far beyond the events through minds, brains, bodies, relationships, and practices and can – and often do – reverberate across generations. For example, the Second World War and the Holocaust claimed the lives of many millions of Jewish individuals. It left an indelible mark on survivors and has resulted in a legacy of intergenerational trauma (Alexander Citation2016; Bloch Citation2021). Or currently, the estimated 65.6 million ‘persons of concern’ worldwide who are exposed to traumatic war experiences, including detention in concentration camps, separation from family, forced displacement, witnessing violence, sexual abuse, and physical torture (Abu Suhaiban, Grasser and Javanbakht Citation2019). Or within the next 50 years, the 1–3 billion people who are projected to be living in areas too hot for human survival (Xu et al. Citation2020). These examples demonstrate that trauma is a phenomenon we can observe historically; in the present; and expect in the future.

Whilst these examples are demonstrative of macro-level events that have affected millions of people in myriad ways, trauma is also caused by relatively more localised events, such as car accidents or bushfires; and everyday, ongoing occurrences that can be hidden, systemic and structural, such as domestic violence, bullying, racism and childhood neglect. Or vicariously, such as encountering graphic images and stories of suffering on social media platforms or as a first responder. An important aspect to note, however, is that trauma begets trauma and individuals previously affected by trauma are more susceptible to its impacts including an increased risk of serious adverse health outcomes (Gelkopf Citation2018). There are a range of personal and socio-political variables that account for each individual’s experience of trauma. Therefore, identifying and understanding trauma is critical if we are to actively prevent trauma, provide safe spaces for recovery and healing, and strengthen post-traumatic resilience in the present, and proactively for the future.

Since the 1990s, historical traumatic events and experiences have been a focus among several disciplines and inter-disciplinary fields of study in the humanities, namely trauma studies, Holocaust Studies, memory studies and more recently genocide studies and geography (Coddington and Micieli-Voutsinas Citation2017; Traverso and Broderick Citation2010). Yet, despite the breadth and depth of literature on heritage related to traumatic events in heritage studies, and related fields of archaeology and tourism studies, there has been little attention given to the concept of psychological trauma (trauma), as a phenomenon, or on the interconnectedness of trauma, as lived experience, and heritage. In general, there is a dearth of information in these fields, about what trauma explicitly is, and what trauma does (Feakins Citation2024).

Although interest in subjects associated with human suffering, conflict, disasters, and death continues to grow in these fields, we argue that there needs to be a more comprehensive theoretical and also practical understanding of trauma – how it affects individuals and collectively across personal, social and political intersections, historically and in the present; how trauma and heritage entangle; and in turn, how to engage with people who have experienced trauma to avoid causing trauma or risking re-traumatisation. Therefore, our aim in this paper is to throw light on trauma. It explores some of these key ideas and themes and recognises potential trauma-heritage (TH) entanglements that can, in turn, inform and frame the development of trauma-informed heritage (TIH) methodologies. As Ireland and Schofield (Citation2014) note, we need approaches that conceptualise ethical responsibilities not as pertaining to the past but to a future-focused domain of social action.

Positioning TH and TIH

Within the heritage studies literature related to traumatic events, empirical definitions of trauma appear to be largely eschewed in favour of broad terms, personal narratives, and sociological concepts. When the term ‘trauma’ is used, it typically denotes a general sense of pain, suffering and atrocity. When the concept of trauma is considered, the language is filled with circumlocutory expression that dances around the topic and frames such as ‘affect’ (Micieli-Voutsinas Citation2021; Tolia-Kelly, Waterton, and Watson Citation2016) and the more recent catch-all, ‘well-being’, are employed (Everill and Burnell Citation2022; Sofaer et al. Citation2021; Taçon and Baker Citation2019).

This may represent a discursiveness that has recently been realised in the humanities in a shift towards a more relational ontology that transcends the subject/object binary (Connor Citation2015). It may also reflect the effectiveness of using ‘emotion language’ to assist in articulating the ‘unspeakable’ (Balaev Citation2018) and supporting healing through the process of writing (Harrington, Porter Morrison, and Pascual-Leone Citation2018; Wardecker et al. Citation2017). This is evident when authors have reflected on their own personal and often profound experiences of trauma (e.g. Atkinson Citation2000; Micieli-Voutsinas Citation2021; Tumarkin Citation2001, Citation2005, Citation2019).

Although autoethnography can offer critical and deeper understandings of individual and embodied experiences of trauma and support healing processes, it can also lack conceptualisation of both broader and more specific understandings of trauma. Likewise, when trauma is intimated using oblique language and euphemisms, trauma can appear amorphous, elusive and for some, unknowable. For example, whilst there have been numerous invaluable studies exploring the potential for heritage to heal (Giblin Citation2014; Harrowell Citation2016; Meskell and Scheermeyer Citation2008; Rowlands Citation2008), explicit readings of trauma have been largely overlooked, even though trauma is central to the concept of such healing. The notion of healing is difficult to conceive unless the ‘other’ can be understood, that is, what trauma is and how it affects people.

Research developed by advisory bodies has largely overlooked lived experiences of trauma. The International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM) and the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) have typically focused on the preservation and restoration of built fabric in connection with disaster events, not on the people who have experienced, or been affected by, the traumatic event (e.g. ICOMOS Citation2017; Kealy et al. Citation2021). As Smith (Citation2012, 2) has argued, this focus on the tangible aspects of heritage represents Authorised Heritage Discourse (AHD) which, ‘advocates a “conserve as found” conservation ethic that assumes that value is innate within heritage sites. It privileges material heritage over the intangible, and emphasises monumentality and the grand, the old and the aesthetically pleasing’. In this space and across more positivist forms of research, emphasis on the material can silence the social and emotional dimensions of heritage, thus rendering individual and collective forms of trauma invisible and therefore unimportant for heritage practices.

The examples mentioned above fall under the rubric of heritage, from theory to practice. They illustrate their opposing positions along a relational-rational continuum and differing epistemes and practices within diverse disciplines. They also exemplify the need to develop an effective theoretical frame and practice tool to better understand and engage with trauma in the heritage space that can interface with individual and collective trauma across social and political intersections.

In the broader trauma studies landscape, debates continue around the representation of trauma, whether focus should be on lived experiences of pain and suffering or survival, resilience, and recovery (Traverso and Broderick Citation2010). As Traverso and Broderick (Citation2010, 3) argue, ‘to reduce all representation of memories and experiences marked by conflict, violence and atrocity to trauma is problematic as it emphasises a victim position and potentially fails to give due attention to the expression of agency’. Yet, trauma is defined by absence and invisibility, not recognising, acknowledging or witnessing trauma is also deeply problematic. By overlooking trauma in the process of heritage-making, the risk of traumatising and re-traumatising is increased through words and actions, especially when working with and for individuals and communities who have experienced trauma.

In psychology and trauma studies, the idea of ‘bearing witness’ is an important aspect of the trauma landscape and supporting social action. It denotes trauma as a ‘story that has to be told in order for healing to begin’ (Caruth and Laub Citation2014, 47). Providing trauma-informed safe spaces for individual and collective trauma to be expressed and witnessed is fundamental to healing, in other words, for people who have experienced trauma to be seen and heard. A trauma-informed approach is guided by the following four assumptions: the realisation of trauma and how it can affect people and groups; recognising the signs of trauma; having a system that can respond to trauma; and resisting re-traumatisation (SAMHSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative Citation2014). The following section offers an in-depth analysis of trauma, including its definition and effects.

The trouble with trauma: what trauma is and does

As a concept, trauma has become a modern-day zeitgeist in developed countries and as a term, has proliferated in everyday discourse. The words ‘trauma’ and ‘traumatic’ are ubiquitous (Altmaier Citation2019). For example, at the end of 2022, the hashtag #traumatok received 2.4 billion internet views (Bogle Citation2022). Trauma has become a popular idiom that holds a broad range of meanings and represents a wide range of cultural phenomena. Hence, ‘trauma’ is also a decidedly slippery term.

In current psychological practice and research, ‘trauma’ is both the causative event and the range of psychological and physical responses that follow the event that impact the individual (Altmaier Citation2019). At some point in their lives, most people will experience a serious traumatic event, be it the death of a loved one, natural disasters, serious accidents or physical or sexual assault. Current global epidemiological studies estimate that over 70% of people will be exposed to extremely traumatic or life-threatening events (Benjet et al. Citation2016; Kessler et al. Citation2017). Further, large-scale traumatic events are set to increase in the future, particularly in connection to climate change and disaster displacement (Woodbury Citation2019). Consequently, having an accurate understanding of trauma in the present is critical for the future.

The term ‘trauma’ was initially conceptualised as a physical injury but later incorporated emotional or psychological forms of distress (Altmaier Citation2019; Kolaitis and Olff Citation2017). It developed alongside ideas of Victorian-era female hysteria and post-World War One ‘shell shock’ (Altmaier Citation2019; Coddington and Micieli-Voutsinas Citation2017). However, it was not until the 1980-90s that the topic had sufficient interdisciplinary support to develop into a field of research. As Coddington and Micieli-Voutsinas (Citation2017) note, its capacity to incorporate individual trauma within collective responses to crises, prompted its theoretical renewal by a diverse coalition of activists, Holocaust survivors, Vietnam veterans, and feminists concerned with sexual assault. They pushed to have past experiences of trauma incorporated into understandings of trauma.

Today, there are several key definitions of trauma in the psychology discipline. The American Psychological Association (APA) define trauma as,

An emotional response to a terrible event like an accident, rape, or natural disaster. Immediately after the event, shock and denial are typical. Longer-term reactions include unpredictable emotions, flashbacks, strained relationships, and even physical symptoms like headaches or nausea. (APA Citation2022)

Similarly, the Australian Psychological Society (APS) define trauma as frightening or distressing events that may result in psychological harm and can affect a person’s ability to cope or function normally (APS Citation2023). The United States of America (USA) based Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) define trauma more broadly as resulting from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.

Trauma causes

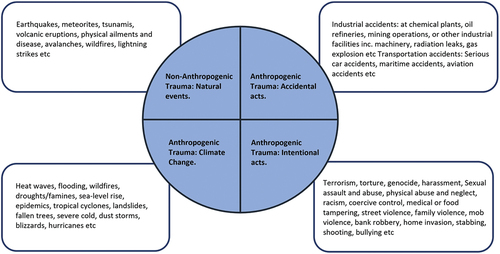

There are numerous events in our contemporary world that now are recognised as traumatic. SAMHSA provides some examples of forms and types of traumas (; NREPP Citation2016). They classify traumatic events as either anthropogenic (caused by humans) or non-anthropogenic. They stress that anthropogenic trauma can be caused by either accidental acts including technological failures, or intentional acts, such as wars. However, climate change caused by human activity can also serve as an additional category. We have classified this as a type of anthropogenic trauma (). Whilst this is not an exhaustive list, it does provide some understanding of events that can lead to trauma, from large-scale events to more localised events.

Traumatic events () can impact individuals and groups, directly or indirectly. This includes individuals and groups directly impacted by the traumatic event, as well as witnesses, first responders and surrounding communities. For instance, an anthropogenic traumatic event can directly affect a single person or a small group of people, such as an electrocution or car accident. Or it can impact many people and communities, as in the case of an aeroplane crash or a radiation leak. Whereas climate change, caused by human activity, also has the potential to impact individuals in a direct way, such as destroying homes through bushfires, as well as entire communities on a global scale, like low-lying islands and communities facing rising sea levels. For example, the people currently living in Tuvalu and Kiribati.

The impacts of trauma can be conceived along a continuum, from a single event (acute trauma) to ongoing and repeated experiences (chronic and complex trauma). However, trauma experienced in childhood can be particularly damaging, altering development and having profound and lasting effects on health and well-being, including the development of chronic illness in adulthood (Kimberg and Wheeler Citation2019). Trauma can also be conceptualised as large ‘T’ trauma, including neglect, abuse, and disasters and small ‘T’ trauma, including childhood bullying, financial issues, and social rejection. While the latter does not threaten a person’s physical safety per se, they can produce the same trauma responses as large T trauma (Straussner and Josephine Calnan Citation2014; Van Der; Kolk Citation2014). Furthermore, the rate at which these events occur can be sudden or slow onset.

Trauma effects and experiences

Trauma effects can be felt on individual, familial, community, and global levels and across generations. However, trauma is a highly subjective phenomenon, and each person’s experience of a traumatic event and their subsequent experiences will differ. Typically, during a traumatic event, the instinctive survival reflex known as the fight, flight or freeze response is triggered. This activates the sympathetic nervous system and the release of adrenaline and cortisol from the adrenal glands. These stress hormones can produce physiological changes in the body at the time of the event including an increase in heart rate, blood pressure, and breathing. Other changes include an increase in alertness, blood sugar, muscle tension, and sweating (Chu et al. Citation2022).

After experiencing the event, most people will have strong emotional or physical reactions that subside within a few days or weeks, including disorganised thinking, altered reaction time, impaired judgement, hypervigilance, and unhelpful attempts at coping (Straussner and Josephine Calnan Citation2014). While most people will experience time-limited reactions, for others, the symptoms may last longer and be more severe. This can lead to substance use disorders, depression, panic disorders, as well as post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD (APS Citation2023).

PTSD and other stressor or trauma-related disorders are classified as psychopathologies in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5th Edition (DSM-5) (Caruth Citation1995; Dolezal and Gibson Citation2022). PTSD is a mental health condition that is triggered after directly (or indirectly) experiencing, witnessing, or learning of trauma. PTSD is associated with a host of physical and psychological concomitants including re-experiencing the event, avoidance, negative cognitions, and hyperarousal. Furthermore, symptoms last for more than one month and create significant distress and or functional impairment.

The prevalence of PTSD is higher among certain populations exposed to traumatic events including, combat exposure, physical injury, disaster and rape. People exposed to these events have demonstrated much higher rates of PTSD than the general population with estimates ranging between 10% and 40% (Sareen Citation2014). Further, some people are at greater risk of developing PTSD including women, war veterans, Indigenous people, refugees, children in abusive situations or in foster care, and emergency workers. For example, women have a higher risk of developing PTSD compared to men and are typically exposed to more interpersonal and high-impact trauma, such as sexual assault (Olff Citation2017). It is estimated that 6% of men and 14% of women who experience a traumatic event will go on to develop PTSD (Yehuda Citation2002).

People who have been exposed to trauma can re-experience the event through stimuli known as triggers (Van Der Kolk Citation2014). For example, someone who has been raped may view someone walking towards them in the street as a potential attacker, or a child who has experienced family violence may view a stern adult as a threat to their life (Van Der Kolk Citation2014). Symptoms of re-experiencing or ‘intrusion’ symptoms can occur whenever an individual has intrusive memories, nightmares or experiences distress or physical reactions to reminders of the traumatic event(s) (DSM-5). For some people, this stress reaction known as a flashback, can feel as intense as the original event and triggers can include sounds, smells, situations, sights, and emotions. For example, hearing a car backfiring like a gunshot; smelling smoke reminiscent of a bushfire; or seeing footage of war on the news.

Re-experiencing can also relate to people’s experience of historical or cultural trauma, or the use of ‘power-over’ relationships that reproduce power and powerlessness by discounting the views, experiences, and preferences of the individual (Sweeney et al. Citation2018). Some individuals who have experienced trauma will continue to live their life as if the trauma were still going on. Every new encounter becomes tainted by the past or they can find it impossible to integrate new experiences into their lives (Van Der Kolk Citation2014). Although traumatic events cause people great pain, the traumatic event itself can become the sole source of meaning for many people who have experienced trauma (Van Der Kolk Citation2014).

The effect of trauma on an individual depends on many factors including gender identity, age, pre-morbid ego strength, family history of trauma, the chronicity of the trauma, the context in which the trauma is experienced, current life stressors, social supports, cultural, religious or spiritual attitude towards adversity, and whether they have experienced trauma previously (Straussner and Josephine Calnan Citation2014). The latter speaks to sociocultural factors, such as whether the person is from a marginalised and or minority group (SAMHSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative Citation2014). For example, the collective experience of oppression in and of itself can feed into the development of trauma amongst marginalised communities, and traumatic events tend to occur more in the lives of people in these groups. Historical and intergenerational trauma, which is defined as the subjective remembering and experiencing of events in the mind of an individual or life of a community, is passed from adults to children in cyclic processes (Judy, Jeffrey, and Caroline Citation2010).

In the Australian context, research led by Jiman and Bundjalung trauma scholar Judy Atkinson, is significant in this area. Atkinson’s research (e.g. Atkinson Citation2000; Judy, Jeffrey, and Caroline Citation2010, 2014) exposes the role of intentional racism in the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait peoples, including racist government policies and traumatic interventions which have compounded the trauma of already distressed lives. Atkinson linked the historical events associated with the colonisation of Aboriginal lands (massacres, ‘accidental’ epidemics, famine, and displacement) to increases in the rates of family violence, child sexual abuse and family breakdown in Indigenous society. She traced one family line across six generations, listing the known memories of victims of sexual and/or physical violence, suffering from mental health illness, attempting suicide, being a perpetrator of violence, and having substance abuse problems (Judy Atkinson etal. Citation2010). Broadly, Atkinson’s research has revealed significant findings on the ongoing impacts of trauma on Aboriginal women, men and children caused by racial and colonial oppression; the connection between childhood trauma and incarceration; and the intergenerational transmission of trauma (Judy Atkinson pers. comm., December 6, 2023).

For some people, trauma causes stress that can manifest physically in the body, such as chronic fatigue, fibromyalgia and other autoimmune diseases (Van Der Kolk Citation2014). Traumatic effects are also cumulative, the more traumatic events an individual is exposed to, the greater the impact on physical and mental health (Sweeney et al. Citation2018). The effects of trauma can also have significant consequences on whether individuals feel ashamed as a result of the trauma (Dolezal and Gibson Citation2022; SAMHSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative Citation2014). Further, traumas that are perceived as intentionally harmful, such as torture, sexual assault, or racism, can be particularly traumatic for individuals and entire communities.

For example, according to Amnesty International, in 2015–16 torture was perpetrated in over 140 countries. They define torture as when somebody in an official capacity inflicts severe mental or physical pain or suffering on somebody else for a specific purpose (Schippert et al. Citation2021). Torture methods vary and can be primarily physical in nature, like electric shocks and beatings, or primarily psychological, such as prolonged solitary confinement or sleep deprivation. Mental health problems common among torture survivors include difficulty in concentrating, memory disturbances, lack of energy, emotional irritability, sexual dysfunction, loss of trust, insomnia, nightmares, phobias, depression, anxiety, and psychosis (Schippert et al. Citation2021). Today, torture survivors are estimated to constitute 5–35% of refugees and asylum seekers worldwide, and up to 76% of adult refugees (AI Citation2022). As Altmaier (Citation2019) notes, studies show that refugees also experience forced labour, destruction of homes, bombing, and injury. In-transit traumas are also common, such as being attacked and injured, witnessing violence, and fearing death. Therefore, the mental health of refugee and migrant people is significantly compromised by pre-migration events, the difficulties of transit, and post-migration and settlement uncertainties. Traumas are widespread during these stages.

By the end of 2021, there were an estimated 89.3 million people forcibly displaced globally as a result of conflict, persecution or human rights violations in countries including Syria, South Sudan, Iraq and Central America (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Citation2023). This figure includes the 27.1 million refugees and 53.2 million internally displaced peoples. In the coming years, refugee numbers are expected to surge from the impacts of armed conflicts, economic instability and climate change, including relentless drought and catastrophic flooding (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Citation2023). Those living in some of the most fragile and conflict-affected countries are likely to be disproportionately affected (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Citation2023). Thus, this culmination of factors means that trauma is set to increase globally and will affect people unevenly. The people who have been previously exposed to trauma are more vulnerable to the effects of new traumatic events.

Locating trauma-heritage (TH) and mobilising trauma-informed heritage (TIH)

As research under the banner of heritage studies continues to grow so too does the concept and definition of heritage. As Lowenthal (Citation2015) emphasised, heritage is everywhere. Generally, heritage refers to intangible cultural practices and tangible materials that are related to broad cultural processes in which meaning is continuously created, recreated, and validated in the present (Harrison Citation2012; Liu, Dupre, and Jin Citation2021; Smith Citation2006). As Waterton and Watson (Citation2015, 1) note, it is a ‘version of the past received through objects and display, representations and engagements, spectacular locations and events, memories and commemorations, and the preparation of places for cultural purposes and consumption’.

In turn, Gentry and Smith (Citation2019) note that critical heritage studies (CHS) is a growing body of scholarship that seeks to move beyond the traditional focus of heritage studies as technical issues of practice and management, to one emphasising cultural heritage as a social, cultural and political phenomenon. For Harrison (Citation2012), CHS is an interdisciplinary assemblage of ideas that has formed as part of a broader consideration of heritage. It explores research themes about what is chosen to conserve and why, the politics of the past, the processes of heritage management, and the relationship between commemorative acts and public and private memory. Importantly, the discourses in CHS frame heritage as a performance in which the meaning of the past is continuously negotiated in the context of the needs of the present (Gentry and Smith Citation2019). Thus, CHS is well-positioned to discuss the nuances of trauma-heritage (TH) and trauma-informed heritage (TIH), towards bridging theory and practice.

Locating TH and mobilising TIH can be realised through either top-down or bottom-up processes, such as place-based or stories-based. Anthropogenic and non-anthropogenic traumatic stressors can be identified in the heritage context, for example roadside memorials to national memorials, or through stories and experiences across individual, family, and or community levels. As illustrated (), stressors can include war, genocide, terrorism, torture, slavery, car accidents, epidemics, colonisation, tsunamis, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, bushfires, floods, industrial accidents, abuse etc.

In the table below (), a range of TH entanglement examples are detailed based on information presented in the previous section. Importantly, they all illustrate the necessity for developing TIH methodologies. For example, a mining accident is a historical and single event. It may have caused loss of life and injuries, resulting in trauma. This can affect individuals, families and communities, including first responders and witnesses. In the heritage context, the event may be commemorated with a memorial or plaque. A range of investigations, across research and industry, may be carried out at the site including archaeology, interviews and or social values or built heritage assessments.

Table 1. Examples of trauma-heritage (TH) entanglements and potential external triggers.

In this process of heritage-making and working with and for individuals and communities who may have experienced trauma at the local level, recognising the potential risks of re-traumatisation is important and therefore doing TIH to mitigate the risk. Potential external triggers could include returning to the place, talking about the event, hearing stories, or seeing objects, archaeology, buildings, images, or news related to the event. Many of these ‘things’ are also used in the representation of the event in heritage-making and may also contribute to the reification of trauma through this process. Other considerations to note are whether the act was intentional or accidental and that each individual’s experience of trauma will be different. Trauma is complex, personal, and nuanced and affects people differently and in myriad ways. Similarly, the trauma can become the sole source of meaning for the individual or group who has experienced the event.

Importantly, TH also shines a light on complex and ongoing processes of trauma across personal, social and political intersections, for example migration and settler-colonial heritage (). In the settler-colonial context, creating spaces for trauma to be witnessed can disrupt normative assumptions, assumed certainties and established hegemonies across research and practice. However, cultural heritage legislation is inextricably tied to harmful policies, programmes and practices in settler-colonial contexts that continue to cause trauma (Vivian and Halloran Citation2022). Trauma-informed care means considering not only how safe the service delivery environment actually is, but also how safe it is perceived to be by the individuals or groups you are working with (Charles, Pence, and Conradi Citation2013). As Nguyen (2011, 29) notes, ‘re-traumatization of the traumatized subjects may occur in the hands of agents that purport to treat and advocate for them’. Therefore, can we meaningfully create safe spaces in these contexts?

Case study: Blacktown Native Institution, Australia

Since 2021, one of the authors (CF) has been collaborating with the Dharug Strategic Management Group (DSMG) at the Blacktown Native Institution (BNI) in western Sydney in developing a trauma-informed approach to frame community engagement and the co-development of the Conservation Management Plan (CMP). The BNI is registered on the NSW Heritage List and the DSMG is responsible for caring for that area of Dharug Nura (Country).

The BNI is a profoundly significant heritage place for First Nations people. It is connected to the historical processes of dispossession, colonisation, and the implementation of successive governments’ policies for ‘protection’, assimilation, integration and reconciliation. Returning the BNI to Dharug ownership in 2018 was a seminal moment in the story of the place and holds significant meaning for the Dharug community today. It reinforces the deeply felt narrative that Nura bayali (Country Still Speaks). It is also a pivotal point in journeys of activism, truth-telling, healing, resilience and learning to belong together with Dharug Nura.

Broadly, a trauma-informed approach has helped to realise and respond to the personal and profound nature and implications of trauma and healing at the BNI. It has recognised the prevalence and pervasive impact of colonisation on the Dharug community historically and today, including how current NSW heritage legislation is unable to accurately represent and respond to Dharug attachments to Nura (Country) and the BNI and therefore impacts the Dharug-centred vision for the BNI and opportunities for healing. It has also built understanding and recognition of the heavy toll on Dharug members in navigating heritage legislation and the ways that it continues to stymie progress towards healing people and Country at the BNI. In the CMP, the principles of trauma-informed heritage management have been central to developing practices that will support, maintain and enhance the significance of the BNI and its place in the cultural landscape for the futures of the Dharug and broader community.

Towards a trauma-informed heritage (TIH)

As illustrated at the beginning of this paper, trauma and heritage are intimately intertwined. We suggest that mobilising TIH in everyday heritage practice can help mitigate the risk of re-traumatisation, and support resilience, empowerment and ethical practices. TIH is guided by evidence-based research in the understanding of and responsiveness to the impact of trauma, that emphasises psychological, emotional and physical safety for people who have experienced trauma and practitioners. It supports the mitigation of re-traumatisation by consciously and compassionately creating an environment where people will not be triggered by situations they may encounter in the heritage setting, such as objects and archaeology; subjects and stories; providing warning; ensuring consent; not forcing someone to talk about the traumatic experience and re-live the event as a flashback. It creates opportunities for individuals who have experienced trauma to feel a sense of control, empowerment, and understanding (Kimberg and Wheeler Citation2019; SAMHSA 2014). It supports cultural humility (as opposed to cultural competence), self-awareness, and respect for self-determination, and can help to abate power differentials (Kimberg and Wheeler Citation2019).

Broadly, in the context of heritage management, conservation, and restoration connected to traumatic events, TIH can disrupt the AHD (Smith Citation2006). Smith (Citation2012, 5) argues, ‘this professional discourse is often involved in the regulation and legitimisation of cultural and historical narratives, and the work that these narratives do in negotiating or maintaining certain societal values and the hierarchies that these underpin’. As TIH emphasises emotion and centres on people with lived experiences of trauma at the local level, it can help shift focus away from the tangible, technical and aesthetic forms of expert knowledge (Smith Citation2006) and towards people-place-centred heritage and understandings of the social and emotional aspects of heritage (Brown Citation2015).

Johnston (Citation1994) defines social value as the ‘collective attachment to places that embody meanings important to a community’. These values are fluid and culturally specific forms embedded in practice and experience. Some may align with official, state-sponsored ways of valuing the historic environment, but many aspects of social value are created through unofficial and informal modes of engagement (Jones Citation2017). However, as Jones (Citation2017) states, the need to identify, narrate and measure value is a complex and difficult issue within the heritage sector. TH and TIH are important concepts in understanding social value, social impact, and social sustainability of heritage places. Individual and collective experiences of trauma as they relate to heritage places are important considerations, as the trauma itself can become the sole source of meaning for people (Van Der Kolk Citation2014). Therefore, creating space for trauma narratives and expressions across various media in understanding social value opens up opportunities for people with lived experiences of trauma to be seen and heard.

Participatory approaches that centre power on the community in research and collaborative decision making are important (Jumarali et al. Citation2021). Integral to this aspect of TIH is listening and creating safe spaces for people who have experienced trauma to speak and holding space for them to do so (Laub Citation2014). Engaging with community members who have experienced trauma and developing methods to support people in the processes of articulating trauma and bearing witness is key and will be explored in more detail in subsequent research. As Stroinska et al (Citation2014, 18) highlight, trauma may not be expressed in words but can be ‘communicated through silences and omissions. It can be represented in pictures or in a composition of colours or textures. It may be said through music or expressed through laughter’. Further, Balaev (Citation2018, 364) notes, ‘since traumatic experience enters the psyche differently than normal experience and creates an abnormal memory that resists narrative representation, the unique process of this remembering results in an approximate recall but never determinate knowledge’.

TIH disrupts biases in the interpretation of the past and helps interrupt the cycle of trauma. For example, disrupting official settler-colonial narratives with First Nations accounts of local and everyday lives that speak to the historical and ongoing trauma of colonial invasion (Feakins Citation2019). It disrupts heritage that has a self-affirming, positive, and contemporary identity (Macdonald Citation2009) a phenomenon conceived as the ‘touristic utopic landscape’ in heritage tourism (Byrne Citation2009) with everyday accounts that reflect painful emotions and memories. Importantly, being trauma-informed doesn’t mean we must all become health care professionals, merely that we must have enough understanding to be able to build, implement, and review with a trauma lens. Above all, feeling safe is an essential aspect of TIH. As Van Der Kolk (Citation2014) notes, being truly heard and seen by the people around us and being held in the mind and heart of someone is key for healing and post-traumatic growth.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Charlotte Feakins

Charlotte Feakins teaches heritage studies and historical and contemporary archaeology at the University of Sydney. She is a heritage practitioner, researcher, and lecturer with a background in historical archaeology. She is particularly interested in topics of trauma and heritage; trauma-informed heritage; emotion and affect; narrative and identity; community heritage; social values; social and climate justice; anti-colonialism; heritage interpretation; heritage tourism; and methodological innovation. Charlotte is a Partner Investigator (PI) on the ARC-Linkage project, Everyday Heritage. She is an Honorary Researcher at the College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University (ANU) and a Collaborating Scholar at the Research Centre for Deep History at the ANU.

Emma Barrett

Emma Barrett is an Associate Professor and Psychologist at the Matilda Centre for Research in Mental Health and Substance Use at the University of Sydney. She is currently an NHMRC Emerging Leadership Fellow and is leading a program of work to understand and address the impact of child and adolescent trauma across the lifespan. Using epidemiological, longitudinal and clinical trial methodologies spanning key populations in clinical, school and forensic settings, her research aims to generate new knowledge on early trauma and develop innovative, scalable interventions to improve the wellbeing of people impacted by this pervasive public health issue.

Marlee Bower

Marlee Bower is a Research Fellow at the Matilda Centre for Research in Mental Health and Substance Use at the University of Sydney. Marlee’s work focuses on the broader social determinants of mental health, particularly in understanding loneliness and isolation amongst marginalised individuals and how this relates to their built environment. She is currently Academic Lead of Australia’s Mental Health Think Tank.

References

- Abu Suhaiban, H., L. R. Grasser, and A. Javanbakht. 2019. “Mental Health of Refugees and Torture Survivors: A Critical Review of Prevalence, Predictors, and Integrated Care.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16 (13): 2309. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132309.

- AI. 2022. Amnesty International, ‘Refugees, Asylum Seekers and Migrants’.Accessed November 11, 2023. https://www.amnesty.org/en/what-we-do/refugees-asylum-seekers-and-migrants/

- Alexander, J. C. 2016. “Culture Trauma, Morality and Solidarity: The Social Construction of ‘Holocaust’ and Other Mass Murders.” Thesis Eleven 132 (1): 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0725513615625239.

- Altmaier, E. M. 2019. “1 - an Introduction to Trauma.” In Promoting Positive Processes After Trauma, edited by E. M. Altmaier, 1–15. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-811975-4.00001-0.

- APA (American Psychological Association). 2022. “Trauma.” Apa Org/Topics/Trauma/. https://www.apa.org/topics/trauma/.

- APS (Australian Psychological Society). 2023. “Trauma.” https://Psychology.Org.Au/for-the-Public/Psychology-Topics/Trauma. February 21.

- Atkinson, T. 2000. Trauma Trails, Recreating Song Lines: The Transgenerational Effects of Trauma in Indigenous Australia. North Melbourne: Spinifex Press.

- Balaev, M. 2018. “Trauma Studies.” A Companion to Literary Theory 360–371. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118958933.ch29.

- Benjet, C., E. Bromet, G. Karam, R. C. Kessler, K. A. McLaughlin, A. M. Ruscio, V. Shahly, et al. 2016. “The Epidemiology of Traumatic Event Exposure Worldwide: Results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium.” Psychological Medicine 46 (2): 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715001981.

- Bloch, A. 2021. “How Memory Survives: Descendants of Auschwitz Survivors and the Progenic Tattoo.” Thesis Eleven 168 (1): 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/07255136211042453.

- Bogle, A. 2022. “#TraumaTok: How Trauma Took over the Internet.” ABC Radio National. https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/allinthemind/trauma-tok-internet/14110822.

- Brown, S. 2015. “Place-Attachment in Heritage Theory and Practice: A Personal and Ethnographic Study.” PhD., Sydney: University of Sydney.

- Byrne, D. 2009. “A Critique of Unfeeling Heritage.” In Intangible Heritage, 243–266. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203884973-19.

- Caruth, C., ed. 1995. Trauma: Explorations in Memory. Baltimore, MD, and London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Chu, B., K. Marwaha, T. Sanvictores, and D. Ayers. 2022, September 12. “Physiology, Stress Reaction.” StatPearls [Internet]. reasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Accessed January, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541120/.

- Coddington, K., and J. Micieli-Voutsinas. 2017. “On Trauma, Geography, and Mobility: Towards Geographies of Trauma.” Emotion, Space and Society 24:52–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2017.03.005.

- Connor, A. 2015. “Heritage in an Expanded Field.” In A Companion to Heritage Studies, edited by W. Logan, M. N. Craith, and U. Kockel, 254–267. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118486634.ch18.

- Cooke, S., S. Hayes, E. Kay, and A. Catrice. 2020. “Managing Difficult Heritage at Kildonan/Allambie: The Heritage Values of Former Orphanages and Children’s Homes.” Historic Environment 32 (2): 28–43.

- Daly, P., and B. Chan. Putting Broken Pieces Back Together, 491–506. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118486634.ch33.

- De, M. F., F. Larosa, D. Porrini, and J. Mysiak. 2021. “Cultural Heritage and Disasters Risk: A Machine-Human Coupled Analysis.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 59:102251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102251.

- Dolezal, L., and M. Gibson. 2022. “Beyond a Trauma-Informed Approach and Towards Shame-Sensitive Practice.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 9 (1): 214. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01227-z.

- Everill, P., and K. Burnell. 2022. Archaeology, Heritage, and Wellbeing Authentic, Powerful, and Therapeutic Engagement with the Past. 1st ed. Oxon: Routledge.

- Feakins, C. 2019. “Buffalo Shooting in the ‘Wild’ North: The Forgotten Heritage of Kakadu National Park.” Historic Environment 31 (1): 10–26. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.997410022831113.

- Feakins, C. 2024. “Traumatic Pasts, Presents and Futures: Trauma and Archaeology.” Australian Archaeology 90 (1). https://doi.org/10.1080/03122417.2024.2317526.

- Gelkopf, M. 2018. “Social Injustice and the Cycle of Traumatic Childhood Experiences and Multiple Problems in Adulthood.” JAMA Network Open 1 (7): e184488. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4488.

- Gentry, K., and L. Smith. 2019. “952-Article Text-2808-2954-10-20200813 (3).” International Journal of Heritage Studies 25 (11). https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2019.1570964.

- Giblin, J. D. 2014. “Post-Conflict Heritage: Symbolic Healing and Cultural Renewal.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 20 (5): 500–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2013.772912.

- Graham, B., G. Ashworth, and J. Tunbridge. 2000. A Geography of Heritage. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315824895.

- Harrington, S. J., O. Porter Morrison, and A. Pascual-Leone. 2018. “Emotional Processing in an Expressive Writing Task on Trauma.” Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice 32 (August): 116–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CTCP.2018.06.001.

- Harrison, R. 2012. Heritage: Critical Approaches. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203108857.

- Harrowell, E. 2016. “Looking for the Future in the Rubble of Palmyra: Destruction, Reconstruction and Identity.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 69:81–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.12.002.

- Ian, C., C. Gerard, and D. Peter. 2014. “Introduction.” In Displaced Heritage, edited by I. Convery, G. Corsane, and P. Davis, 1–6, NED-New ed. Responses to Disaster, Trauma, and Loss. Boydell & Brewer. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.library.sydney.edu.au/stable/10.7722/j.ctt6wp8nw.7.

- ICOMOS. 2017. Post Trauma Recovery and Reconstruction for World Heritage Cultural Properties, 16. Paris: ICOMOS.

- Ireland, T., and J. Schofield. 2014. The Ethics of Cultural Heritage. New York, NY, UNITED STATES: Springer New York. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/usyd/detail.action?docID=1968114.

- Janowski, J. 2020. “Bamiyan’s Echo: Sounding Out the Emptiness.” In Philosophical Perspectives on Ruins, Monuments, and Memorials, 215–227. 1st ed. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315146133-19.

- Johnston, C. 1994. What Is Social Value? : A Discussion Paper. Technical Publications Series ; No. 3. Canberra. Canberra: Australian Govt. Pub. Service.

- Jones, S. 2017. “Wrestling with the Social Value of Heritage: Problems, Dilemmas and Opportunities.” Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage 4 (1): 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/20518196.2016.1193996.

- Judy, A., N. Jeffrey, and A. Caroline. 2010. “Trauma Transgenerational Transfer and Effects on Community Wellbeing.” In Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice, edited by N. Purdie, P. Dudgeon, and R. Walker, 135–144. Canberra, ACT: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

- Jumarali, S. N., N. Nnawulezi, S. Royson, C. Lippy, A. N. Rivera, and T. Toopet. 2021. “Participatory Research Engagement of Vulnerable Populations: Employing Survivor-Centered, Trauma-Informed Approaches.” Journal of Participatory Research Methods 2 (2). https://doi.org/10.35844/001c.24414.

- Kealy, L., Z. Aslan, L. DeMarco, A. Hadzimuhamedovic, and T. Kono. 2021. “ICOMOS-ICCROM Analysis of Case Studies in Recovery and Reconstruction Report.” Charenton-le-Pont & Sharjah.

- Kessler, R. C., S. Aguilar-Gaxiola, J. Alonso, C. Benjet, E. J. Bromet, G. Cardoso, L. Degenhardt, et al. 2017. “Trauma and PTSD in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys.” European Journal of Psychotraumatology 8 (sup5): 1353316–1353383. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1353383.

- Kimberg, L., and M. Wheeler. 2019. Trauma and Trauma-Informed Care. 25–56. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04342-1_2.

- Kolaitis, G., and M. Olff. 2017. “Psychotraumatology in Greece.” European Journal of Psychotraumatology 8 (sup4). https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1351757.

- Kolk, B. V. D. 2014. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Viking Penguin.

- Laub, D. 2014. “A Record That Has to Be Made: An Interview with Dori Laub.” In Listening to Trauma: Conversations with Leaders in the Theory & Treatment of Catastrophic Experience, edited by C. Caruth, 1–392. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Lennon, J., and M. Foley. 2000. Dark Tourism. London: Continuum.

- Liu, Y., K. Dupre, and X. Jin. 2021. “A Systematic Review of Literature on Contested Heritage.” Current Issues in Tourism 24 (4): 442–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1774516.

- Lowenthal, D. 2015. “Introduction.” In The Past Is a Foreign Country – Revisited, edited by D. Lowenthal, 1–22. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139024884.002.

- Macdonald, S. 2009. Difficult Heritage. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203888667.

- Manhart, C. 2015. “The Intentional Destruction of Heritage.” A Companion to Heritage Studies 280–294. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118486634.ch20.

- Maté, G. 2021. The Wisdom of Trauma. US: The Hive Studios, Maurizio Benazzo.

- Meskell, L. 2002. “Negative Heritage and Past Mastering in Archaeology.” Anthropological Quarterly 75 (3): 557–574. https://doi.org/10.1353/anq.2002.0050.

- Meskell, L., and C. Scheermeyer. 2008. “Heritage As Therapy: Set Pieces from the New South Africa.” Journal of Material Culture 13 (2): 153–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183508090899.

- Micieli-Voutsinas, J. 2021. Affective Heritage and the Politics of Memory after 9/11 : Curating Trauma at the Memorial Museum. Abindon, Oxon, UK: Routledge.

- Munawar, N. A. 2019. “Competing Heritage: Curating The Post‐Conflict Heritage Of Roman Syria.” Bulletin - Institute of Classical Studies 62 (1): 142–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-5370.12101.

- Nagaoka, M., and M. Nagaoka. 2020. The Future of the Bamiyan Buddha Statues Heritage Reconstruction in Theory and Practice. 1st ed. Cham: Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51316-0.

- NREPP (National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices). 2016. Behind the Term: Trauma. Maryland: Prepared in 2016 by Development Services Group, Inc.

- Olff, M. 2017. “Sex and Gender Differences in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: An Update.” European Journal of Psychotraumatology 8 (sup4). https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1351204.

- Rowlands, M. 2008. “Civilization, Violence and Heritage Healing in Liberia.” Journal of Material Culture 13 (2): 135–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183508090900.

- SAMHSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative. 2014. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. USA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHA), Office of Policy, Planning and Innovation.

- Sareen, J. 2014. “Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Adults: Impact, Comorbidity, Risk Factors, and Treatment.” The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 59 (9): 460–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371405900902.

- Sather-Wagstaff, J. 2011. Heritage That Hurts: Tourists in the Memoryscapes of September 11. Taylor & Francis Group. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/usyd/detail.action?docID=684529.

- Schippert, A. C. S. P., E. Grov, A. Kristin Bjørnnes, and A. M. Kamperman. 2021. “Uncovering Re-Traumatization Experiences of Torture Survivors in Somatic Health Care: A Qualitative Systematic Review.” PLOS ONE 16 (2): e0246074. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246074.

- Smith, L. 2006. Uses of Heritage. New York: Routledge.

- Smith, L. 2012. “Discourses of Heritage : Implications for Archaeological Community Practice.” Nuevo Mundo Mundos Nuevos, October. https://doi.org/10.4000/nuevomundo.64148.

- Sofaer, J., B. Davenport, M. Louise Stig Sørensen, E. Gallou, and D. Uzzell. 2021. “Heritage Sites, Value and Wellbeing: Learning from the COVID-19 Pandemic in England.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 27 (11): 1117–1132. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2021.1955729.

- Straussner, S. L. A., and A. Josephine Calnan. 2014. “Trauma Through the Life Cycle: A Review of Current Literature.” Clinical Social Work Journal 42 (4): 323–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-014-0496-z.

- Stroinska, M., V. Cecchetto, and K. Szymanski. 2014. The Unspeakable: Narratives of Trauma. Frankfurt a.M: Peter Lang GmbH, Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften.

- Sweeney, A., B. Filson, A. Kennedy, L. Collinson, and S. Gillard. 2018. “A Paradigm Shift: Relationships in Trauma-Informed Mental Health Services.” BJPsych Advances 24 (5): 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2018.29.

- Taçon, P., and S. Baker. 2019. “New and Emerging Challenges to Heritage and Well-Being: A Critical Review.” Heritage 2 (2): 1300–1315. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2020084.

- Tolia-Kelly, D. P., E. Waterton, and S. Watson, eds. 2016. Heritage, Affect and Emotion. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315586656.

- Traverso, A., and M. Broderick. 2010. “Interrogating Trauma: Towards a Critical Trauma Studies.” CONTINUUM: Lifelong Learning in Neurology 24 (1): 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304310903461270.

- Tumarkin, M. 2001. “‘Wishing You Weren’t Here … ’: Thinking about Trauma, Place and the Port Arthur Massacre.” Journal of Australian Studies 25 (67): 196–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/14443050109387653.

- Tumarkin, M. 2005. Traumascapes: The Power and Fate of Places Transformed by Tragedies. Melbourne: Melbourne University Publishing.

- Tumarkin, M. 2019. “Twenty Years of Thinking about Traumascapes.” Fabrications : The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand 29 (1): 4–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10331867.2018.1540077.

- Tunbridge, J. E., and G. J. Ashworth. 1996a. Dissonant Heritage : The Management of the Past as a Resource in Conflict. Chichester: J. Wiley.

- Tunbridge, J. E., and G. J. Ashworth. 1996b. Dissonant Heritage : The Management of the Past as a Resource in Conflict. Chichester: J. Wiley.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2023. Refugee Statistics.

- Vivian, A., and Halloran, M. J. 2022. Dynamics of the policy environment and trauma in relations between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the settler-colonial state. Critical Social Policy 42 (4): 626–647. https://doi.org/10.1177/02610183211065701.

- Wardecker, B. M., R. S. Edelstein, J. A. Quas, I. M. Cordón, and G. S. Goodman. 2017. “Emotion Language in Trauma Narratives Is Associated with Better Psychological Adjustment Among Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 36 (6): 628–653. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X17706940.

- Waterton, E., and S. Watson. 2015. The Palgrave Handbook of Contemporary Heritage Research. London, UNITED KINGDOM: Palgrave Macmillan UK. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/usyd/detail.action?docID=1953015.

- Wilson, C., D Pence, and L. Conradi. 2013, November 4. “Trauma-Informed Care.” In Encyclopedia of Social Work, edited by C., Franklin. NASW Press and Oxford University Press. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://oxfordre.com/socialwork/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.001.0001/acrefore-9780199975839-e-1063.

- Woodbury, Z. 2019. “Climate Trauma: Toward a New Taxonomy of Trauma.” Ecopsychology 11 (1): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2018.0021.

- Xu, C., T. A. Kohler, T. M. Lenton, J.-C. Svenning, and M. Scheffer. 2020. “Future of the Human Climate Niche.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (21): 11350–11355. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1910114117.

- Yehuda, R. 2002. “Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.” New England Journal of Medicine 346 (2): 108–114. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra012941.