ABSTRACT

The article explores the ‘making of martyrs’ at the intersection of media (especially cinema), propaganda, and body politics in Iran. Martyrs are not only highly contested bodies, but also surrounded by diverse media techniques which compete for the right to re-make these bodies and organize the visual economy of witnessing. In the Islamic Republic of Iran, the cultural industry called Cinema of Sacred Defence sought to monopolize the right to make martyrs after the 1979 Revolution, pursuing a strategy of ascribing different qualities of witnessing to different media. Along films such as Ebrahim Hatamikia’s Damascus Time (2018) and Mohammad Hossein Mahdavian’s Standing in the Dust (2016), the article examines the new ciné-martyrographies of the Sacred Defence and demonstrates how the Islamic Republic's visual propaganda machinery uses old and new digital media as 'messages’ – in terms of boundary building as well as the ability to generate genuine Islamic witnessing. In contrast, counter-martyrographies – such as Shahram Mokri’s Fish and Cat (2013) and Careless Crime (2020)— are explored that challenge the state’s iconology of the martyr and its monopoly on (blood) testimony by depicting media techniques of witnessing that remember those who have no right to be remembered as martyrs by the state.

Introduction

The history of martyrdom is the history of relations between media, propaganda, and body politics. Claiming a body as ‘sacrifice in the name of’ also means using the media in a certain way in order to make people believe in a heroic act of decisiveness and death-defying commitment. Thus, martyrdom has to find a spectacular audio-visual body—a body of display—and a sociotechnical, viral promotion in order to be witnessed as such. The following article subsumes these audio-visual practices under the keyword martyrographies: the medio-technical making (‘writing’) of a martyr as well as the media rituals of re-membering a martyred body. Using a discourse analytical and especially media archaeological approach, this article focuses on the analogue and digital media techniques of witnessing as represented and negotiated in the Iranian cinema after the 1979 Revolution. The film-immanent media constellations are examined both as forms of propagandistic reinforcement of the ideology of state martyrdom and as challenges to the state’s monopoly on making martyrs. The case studies will include recent re-brandings of the Sacred Defence Cinema as well as examples of—what will be called – counter-martyrographies: The ‘counter’ refers to subjugated memories and repressed (media-)histories of witnessing that have the potential to destabilize the hegemonic body politics of state martyrdom—provided that we take into account that the state martyrographies themselves are inherently unstable since they are the products of different (and sometimes conflicting) groups and interests. The underlying conflict between mystical and clerico-legal concepts of martyrdom in state martyrographies is such a sign of instability that also shaped the contradictions of state projects like the Cinema of Sacred Defence (Sīnimā-yi Difāʿ-i Muqaddas).

Shahādat

Before dealing with the manifold facets of media witnessing in Iranian cinema between martyr propaganda and its refined subversion, it is necessary to take a closer look at the role of martyrdom and witnessing in Shiʼite culture—and especially at how the post-revolutionary Islamic ʻmartyrocracyʼFootnote1 appropriated this culture and put cinema technology at the service of their body politics.

There are two classical meanings of shahādat (martyrdom): bearing witness and sacrificing oneself for the sake of a higher truth. These two meanings were not always interconnected. While shahīd in the sense of ‘witness’ is ʻfairly common in the Qur’an’,Footnote2 the compatibility of this meaning with the later prevailing aspect of ʻself-sacrifice’ was not self-evident from the beginning. Rather, the ‘Muslim tradition had to invent this connection’, be it (a) as ‘a reflex of late antique Christian usage’,Footnote3 (b) as an effect of the gradual establishment of a modern battlefield martyrdom,Footnote4 or (c) in the sense of a ‘mysticism of suffering’Footnote5 and the lover’s devoted willingness to sacrifice him-/herself for the mystical union with the beloved, and thus become a witness of divine beauty (cf. Mantiq al-tayr [The Conference of Birds] by Farid al-Din ʿAttar, d. 1221).

Even though the Shiʼite catalogue of martyrs is very extensive, a death cult already existed around pre-Islamic heroes, and the Shahnamah – the Persian national epic, believed to have been composed between 977 and 1010 CE—provides a rich archive of appropriations of the pre-Islamic martyr myths. The passion of Siyavash, for example, can certainly be read as a prefiguration of the passion of Husayn Ibn ʿAli (626–680 CE) as staged and re-enacted in the only Shi’ite form of drama, the Taʿziyah.Footnote6 The strictly coded mourning ritual commemorates the martyrdom of Husayn—the king of martyrs and grandson of Prophet Muhammad—not only as the topological centre of the battle and martyr field called Karbala, but also as the ur-model for witnessing through tragic passion (in Greek as well as in Persian/Arabic mártys/šahīd means ‘witness’).

There is, however, an ambiguity as well as a hermeneutics of suspicion that surrounds every martyr’s body. What exactly can be witnessed through the blood witness of a martyr? In contrast to the figure of the surviving eye-witness, the body of the martyr is first and foremost a silenced, destroyed, no longer living body that is supposed to articulate a truth in the moment of self-destruction, and especially through subsequent media-technological proliferations. Thus, we are dealing with a paradoxical form of transmission: It is precisely through ‘disarticulation’Footnote7 that the martyr has to articulate a (transcendent) truth. This makes the martyr a threshold figure on the edge of silence, a black box surrounded by claims and inscriptions—let’s call it a whole market of propaganda interests attempting to reduce ambiguity and eliminate doubts.

As a ‘limit case of persuasion’,Footnote8 as a threshold figure between the visible and the invisible (or unsayable), the martyr has to find a spectacular audio-visual body—a body of display—and a socio-viral promotion in order to find (second hand) witnesses, and transform his real body into a second, allegorical body that survives. Since there are always ruptures in the chains of transmitting testimonies—who, for example, could have witnessed Husayn’s martyrdom if all his companions had died with him?Footnote9 – strong persuasive media techniques and practices are needed to render the shahīd ‘present’ and ‘visible’, as ʿAli Shariʿati (1933–1977) would have said, who, after he was released from prison in 1965 appeared ‘in a Western style business suit with tie’Footnote10 at the new Islamic Center, the Husayniyyah-yi Irshad in northern Tehran to propagate the shahīd as the one who bears witness by his ‘presence’ and exposes ‘what is being denied’.Footnote11 Without intending to do so, Shariʿati’s presence-ontological theory of martyrdom developed a highly contradictory theory of the martyr’s constitutional mediality: While the worldly limitations imposed by technology are to be overcome by a new spirituality, the martyr’s appearance must be reproduced and iterated by means of media technology (audio tapes, murals, moving images etc.)—in order to become omnipresent, visible everywhere as a moral paragon (‘always in front of us’).Footnote12

The power of cinema to make the shahīd visible as a ubiquitous role model and to produce witnesses is not to be underestimated—and the ulama was well aware of this, even if popular cinema before 1979 was criticized by the religious authorities as a westoxified culture of idolatry (farhang-i ṭāghūtī) and ‘a corruptive site of sociability, dominating over the traditional, religious and local aspects of Iranian life’, as film scholar Golbar Rekabtalaei points out.Footnote13 However, it was not least the popularity of cinema that persuaded Ayatollah Khomeini and the architects of the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) not to ban this powerful medium after the Iranian Revolution, but to use it as a means of ‘educating the people’,Footnote14 as Khomeini announced in his famous speech delivered at the cemetery Bihisht-i Zahra on February 1st (1979) after his return to Iran. Thus, the ‘clerico-engineers’Footnote15 of the theocracy faced the challenge of reprogramming and purifying a ‘westoxified’Footnote16 technology. After a few years of uncertainty about how cinema could be put at the service of Islamic guidance, it was especially after 1983 that the cinematic apparatus was ‘charged with re-educating the national sensorium’,Footnote17 and the Iran-Iraq War (1980–88) not only gave new legitimacy to film as a propaganda instrument, but also gave birth to a new film genre industry, the Cinema of Sacred Defence. In order to understand the contradictions that from within haunt this industry, it is necessary to explore more closely the relationship between religion and technology (especially of cinema).

Technology and religion

The new-born cultural industry of war became a vehicle for promoting a ‘necropolitics’Footnote18 of martyrdom in the name of the Sacred Defence. Thus, we are no longer talking about martyrs of resistance (against state oppression), but martyrs as a necropolitical instrument of governmentality. With the category of ‘state martyrdom’,Footnote19 not only is resistance turned into ‘defence’, but people are transformed into symbolic capital and undead role models who are compelled to continue their sacred service even (and perhaps especially) after death. In this regard, the war cinema became a powerful propaganda tool to arouse the soldiers’ desire to transform their bodies into ‘metaphors’ (of devotion) and to ‘become meaningful’.Footnote20 In Mehran Tamadon’s documentary film Bassidji (2009), we can find a vivid example of this mode of self-transformation through metaphorization, particularly at one point in the film when an interviewed soldier describes his visions of martyrdom with a very common mystical trope: ‘The closer you get to the light, the more you burn’, comparing martyrs to butterflies, which are said to melt in the light of the candle (i.e. god).Footnote21

Just as the Iran-Iraq War poetry ‘exploited’ the themes of martyrdom ‘with a heavy reliance on classical Persian poetry in terms of imagery’ and on the ‘Ashura paradigm’,Footnote22 so too did the Sacred Defence Cinema co-opt mystical imaginaries, which, quite remarkably, often had a strong anti-clerical bent. Medieval metaphors of lovers’ devotion, madness (junūn), sacrifice and mystical guidance became an instrument of the state’s necropolitics. Part of the Shi’ification of cinema and cinematographization of Shi’a Islam in accordance with the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance (MCIG) was what one might call the taming, disambiguation and uniformization of previously highly ambiguous martyr symbols. The resistant symbols, religious codes and gestures of bearing witness to injustice and state violence, socially endorsed and broadly practiced before the Revolution as part of an ‘unofficial, popular civil religion’,Footnote23 were appropriated after 1979 by ‘the governmental habitus’ that transformed the organic symbols of everyday struggle into fixed signs, empty categories, and ‘marks of a sovereign state that governs both its living as well as its dead population’.Footnote24

Also the underclass heroes, lūtī-hā (or lāt-hā),Footnote25 neighbourhood protectors and screen martyrs of the pre-revolutionary popular Iranian cinema had to undergo a post-revolutionary appropriation, purification (pāksāzī) and transformation process. Paradigmatically, this can be shown with Hūviyyat/Identity (1986) by Ebrahim Hatamikia, an icon of the Sacred Defence Cinema, who came to be a filmmaker through war. Hatamikia’s first feature film Identity introduces us to a hooligan biker as the main character who—in the style of a film noir – loses his memory and his face after an accident, subsequently leaving behind his former, pre-revolutionary thug identity (). After a process of inner purification and outer transformation, he finally is allowed to remove the face bandages, in order to uncover a new Shi’a face. The final moment of unveiling—the removal of the bandages—becomes the ultimate moment of return to a religious self (bāzgasht bah khvīshtan).Footnote26 The eventually awakened, illuminated protagonist looks—via mirror—at the camera, addressing the audience, so that his gaze becomes an Islamic interpellation of the spectator, inviting the viewer to convert as well and to adopt a new Basiji identity.

It was above all Morteza Avini, the pioneer of Sacred Defence imagery, who developed an influential state TV martyrography by means of a trance-like combination of camera work, montage technique, and the soundscape. Avini was not only influenced by Martin Heidegger—or, rather, by Ahmad Fardid’s reading and interpretation of Heidegger—but also by Western media theory, especially by Marshall McLuhan’s dictum ‘The medium is the message’ from Understanding Media (1964).Footnote27 With reference to McLuhan, Avini criticized the message of Western media grammars and, in particular, the power of computers:

Our time is a time of imprisonment in the hands of instruments that possess a cultural identity. The products of Western civilization are all, more or less, embodied forms of Western culture, and what Marshall McLuhan says about this is quite valid. If we look at technology products wisely, we will find the computer much more dangerous than video. The computer is ‘sinful’: Idol of Evil. And although it is not suitable for us to prevent the entry of technological products into our country, if we were to choose between banning either the computer or video, we should definitely ban the computer.Footnote28

Since the engineers and architects of the Islamic guidance of culture claimed a fundamental incompatibility of technology and Islamic art (and poetry),Footnote31 Avini and other representatives of the Sacred Defence Cinema sought to put film technology in the sacred service of a simulated breakthrough to a non-technological, spiritual sphere: ‘The cinema of sacred defense is a religious cinema where the essential struggle or jihad is not with the enemy but with the self, of which the ultimate goal is surrendering oneself to God’s love and seeking union with Him through martyrdom. […] There are no scenes of mourning over the bodies of the dead in these films because there is no death, only martyrdom.’ This is how Pedram Partovi summarizes the ‘Theory of Sacred Defense Cinema’ as developed by Akbar Muhammadabadi.Footnote32

With the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, we can add that the cult of martyrdom as promoted by the Iranian martyrocracy is a shared, sense-making space of symbolic principles that serve to disguise economic interests through a structural ‘double habitus’ inherent to the ‘religious enterprise’: ‘The truth of the religious enterprise is that of having two truths: economic truth and religious truth, which denies the former. […] This ambiguity is a very general property of the economy of the offering, in which exchange is transfigured into self-sacrifice to a sort of transcendental entity’.Footnote33 Viewed from this perspective, the ‘martyr’s welfare state’Footnote34 becomes decipherable as a refined ideological field of orchestrated metaphors and allegories that apply ‘principles of vision and division’,Footnote35 as Bourdieu would say. ‘Vision’ in the sense of seeing something, which is in fact an entrepreneurial recruitment policy, as something different: a religious truth. ‘Division’ in the sense of establishing class distinctions, and insider (khudī)/outsider (ghayr-i khudī) schemas.Footnote36 The martyr is a disguised homo oeconomicus – and inside the garden of martyrs, one could, say, there are hidden corporate interests and a ‘bank denied as such’:Footnote37 an inexhaustible reservoir for the (re-)distribution of symbolic and economic capital. Part of this system of euphemizations is the sacralization of cinema as a transcendent and transparent medium of holy witnessing—while the economic and technical dimensions are concealed.

On the bases of this double game of internalized visions (seeing something as something else) and divisions (symbolic forms that divide people into insiders and outsiders), two classes of media are established, as I will argue below: ‘westoxified’ media, which are rooted in materialism and the colonialism of technology, and those ‘purified’ media that guarantee the vision of truth and engagement with spirituality. Crucial, however, as will become apparent, is that this boundary between insider and outsider media is in constant flux, and state martyrographies are inherently unstable as they are challenged by new media. The new technologies of witnessing constantly destabilize the state’s monopoly on ‘making martyrs’ – and its control over the division between official (khudī) and unofficial (ghayr-i khudī) media. Thus, in order to keep up with the times, the state’s ‘sacred media channels’ must allow themselves to be contaminated (westoxified) by new media in order to stay technologically well-equipped enough to guarantee new purity.

The state should not be conceived as a monolithic entity, but rather as an ensemble of power relations and institutions. In an analogous way, the state’s ciné-martyrographies are the products of a network that constantly reorganizes itself—a dispositif of regulations, interests, groups, and institutions such as the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance (Irshād), the Farabi Cinema Foundation, and—as will be shown—an increasing number of (pseudo-)private media arms connected to the state-run media economy.

State of the (Propaganda) art: a media cultural dualism

Like Avini, many current representatives of the Sacred Defence Cinema still use film technology and digital media in the service of religious state art, simulating a breakthrough to a non-technological, otherworldly sphere. Nevertheless, the denial of technological mediation precisely in the heart of media technology has reached a new level: Since 1988, there have not only been various—more or less successful—attempts to rebrand Sacred Defence Cinema and redesign its aesthetics and tropes. Looking at contemporary Iranian cinema, we can also discern a hypertrophic thematization of media techniques of witnessing and questions of trans-generational transmission. It may hardly come as a surprise that these issues are negotiated quite differently in pro-regime ciné-martyrographies than in dissident counter-martyrographies, which will be the focus of the last part of this article.

What the Sacred Defence Cinema 2.0 has been trying to establish for quite some time, is what can be called a two-class system or two-worlds ontology of media: The class of state-sanctioned ‘truth media’ is juxtaposed with the class of supposedly westoxified media technologies. Media and their (di-)visions are in fact used by propaganda as messages (McLuhan) in order to establish different classes of witnessing. In many cases analogue media with a claimed, indexical relationship to body witnessing—such as handwritings, signatures or audio cassettes (reminiscent of Khomeini’s speeches and sermons, distributed via ‘small media’)Footnote38 —are used as ‘truth media’ for insiders, while digital media are associated with the terrorist ‘other’. What used to be videocassettes and satellite dishes for a long time, banned for spreading Western values—needless to say: this spell failed spectacularlyFootnote39 –, have now become other, digital media. In this respect, Ebrahim Hatamikia’s epic war movie Bah Vaqt-i Shām/Damascus Time (2018) is a most revealing example, a film that re-directs the attention from Sacred Defence to ‘Sacred Intervention’, as Nikki Akhavan would say.Footnote40 The purpose of Hatamikia’s—special effects packed—action movie is to tell the story of those whose heroic struggle is not covered by the Western media: It’s about the involvement of the IRGC (Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps) in the Syrian Civil War and their fight against the terrorism of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, also called DAESH), condensed in the story of pilot Younes (Babak Hamidian) and his pilot father ʿAli (Hadi Hejazifar)—who looks strikingly like Qasem Soleimani, the commander of the Quds Forces (assassinated on 3 January 2020 by a US drone strike). The mission of father and son is to evacuate refugees from Palmyra airport by a cargo plane—before DAESH can tighten its siege ring around the city. Remarkable in this context are the different roles attributed to the various media in this film: Media of true witnessing are opposed to media that fake witnessing.

Throughout the film, the conflict between technology and the spirit, which—as Roxanne Varzi and Nacim Pak-Shiraz have shownFootnote41 – has long been a part of the Cinema of Sacred Defence—is taken to a new media level: The propaganda machinery of DAESH is associated with digital media tools and a westernized selfie-culture, while, in contrast, true blood witnessing is ascribed to the members of the IRGC (Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps). As some of them are about to be executed by the henchmen of the DAESH in the arena of the ancient city of Palmyra, we are dealing with two competing technologies of witnessing. On the one side, the outside, we have a westoxified way of fake witnessing: The long bearded, ‘barbarian’ warriors of the DAESH stage their executions for the drone’s eye as the epitome of their toxic image economy. The cruel blockbuster spectacle is directed by a crazy media terrorist who gives instructions in front of a wall of loudspeakers like the capitalist manager of a Western rock concert. In contrast, the warriors on the side of Sacred Defence and Intervention are associated with body media of true, indexical witnessing: When father and son are about to be executed with their fellow fighters in the arena, the eyes of true witnessing suddenly appear at the horizon, ready to transform the death of the revolutionary guardians into true sacrifice. On the tribune of the arena appears ‘mothervatan’Footnote42 – an allegorical imagination of homeland as an old mother with chador, who co-witnesses the martyrdom like a descendant of Zaynab, Husayn’s sisterFootnote43 () Ali). ʿAli and Younes, who are close to be martyred in the arena of Palmyra (as it will turn out, they should be spared for now),Footnote44 subsequently try to turn away from the drone’s eye and salute the real witnesses: ‘Yā Ḥusayn! Yā Fāṭimah!’

The geopolitical construction of ‘imagined communities’Footnote45 and the classification of people into insiders and outsiders is rendered by a binarized class system of media technologies: state media and media non grata. This media distinction is particularly tricky when we consider that the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Aerospace Force (IRGC-ASF) and the Quds Force have been using drones since 2013, significantly called ‘Shāhid’. As unmanned successors to the martyr’s death drive, as self-destruction mechanisms guided by algorithms of (self-)destruction, the aerial combat vehicles were not only used in the Syrian Civil War, but also delivered to support Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine in 2022.

And, not to be overlooked: Even though Damascus Time attributes the inner diegetic drone perspectives—as well as GoPro-Action Cams—to DAESH’s image economies, the film itself makes frequent use of drone perspectives to develop certain aesthetics of aerial mapping. Thus, admittedly or not, the Cinema of Sacred Defence itself had to appropriate new digital media in order to keep up with the times—just as Hatamikia broke away from his principles and explicitly embraced digital special effects in the service of re-branding the Sacred Defence as Sacred Intervention.

Khuṣūlatī industry

How to re-brand the core values of the Islamic Revolution and the Sacred Defence, in a society that finds itself increasingly detached from the rhetorics and interests not only of the current regime, but the entire system? How to reanimate the credibility of eroded, emptied categories for a young generation barely in touch with the formative experiences of war and revolution? These are the major concerns and challenges the pro-regime cultural producers are facing in an ideologically fragmented ‘granular society’Footnote46 under conditions of new digital media. Since a language of prohibition and policy of censorship can only survive if it keeps pace with technological changes, the bureaucrats of Islamic culture also made concessions to the digital culture. In other words, if power always said ‘no’, then no one would obey it.Footnote47

This can be shown by the changing stance of the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance—and, connected to it, the Farabi Cinema Foundation—towards digital filmmaking: While at the beginning of the era of digitally shot films, the Islamic Republic’s cultural managers tried to maintain control over film equipment by ascribing ‘a higher value’ to films ‘shot with analogue cameras’ and on 35 mm film material (provided by Farabi), producers and distributors loyal to the regime adapted step by step to the digital transformation of the image economy. With their ability to operate in digital media environments, pro-regime cultural producers have developed new techniques to camouflage their monopoly over image production and diversify propaganda through private, yet regime loyal companies—often with a close connection to the IRGC. Part of this new media strategy is the production of what can be called Khuṣūlatī films. Iranian director Shahram Mokri gives a very precise description of this category of fake independent films:

After several failures, in 2004 the state-run economy was supposed to be handed to the private sector. This was something at which other countries in the world had already succeeded. But what occurred in Iran was the distribution of the state’s industry into the hands of newly formed state-related branches of the military and politicians. As if, in the absence of a real private sector and foreign investors, the state bought parts of its own body. Thus, a new term formed in Farsi which was similar to filmfarsi. ‘Khusūlatī industry’ was a combination of two words: private (khuṣūsī) and state (dawlatī). Khuṣūlatī agencies also formed in the film industry. They claimed to be independent while being funded by the state […].Footnote48

In terms of technical and aesthetic standards, the film can be considered as cutting-edge. We are dealing with an aesthetics that is based on a restless, shaky cam style, a kind of ‘direct cinema’-mimicry. At the same time, the film makes use of lip syncing: a technique for matching the lip movements of a speaking or singing person with pre-recordings. The actors’ voices are replaced by voice-overs from family members, friends, eye-witness reports from other commanders, and in some rare instances, by real audio clips of Motevaselian’s speeches or snippets of his strategic walkie-talkie-communication on the battlefield. Already at the beginning of the film, during the title credits, we are shown audio cassettes spinning in a tape recorder as iconic allusions to Khomeini’s messages and sermons (which circulated on tapes during the Revolution 1978/79). Thus, the film makes every effort to re-mediate small, indexical media associated with revolution and war, in order to re-present them as Islamic identity techniques and indigenous media that guarantee community building and true, continuous witnessing.

The term ‘bearing witness’ is crucial in this respect: the film re-inscribes past (body) testimonies into the present and puts the viewer in a cleverly-constructed position of trans-temporal eye and ear witnessing. This access to the past is reinforced through a constant tele-lens perspective on past events from the present point of view, or better: point of listening. In this way, the spectator is able to listen to audio documents, oral reports and speeches, while watching their trans-visualization like a spyglass-witness who has ‘first-hand’ access to the past. The events are presented as if they were simultaneously ‘here and now’, ‘there and then’, and the aura of the shahīd is generated not only through establishing trans-temporal contact, but also through partly obscured, obstructed views, since we are dealing with a persona who, like Imām Zamān disappeared into occultation ().

Figure 3. Screen grabs from Istādah dar Ghubār/Standing in the Dust, 2016, Mohammad Hossein Mahdavian.

Crucial to my argument is that films like Standing in the Dust address small, iconic media (audio tapes, walkie talkies, radio equipment) with a strong ideological appeal and a revolution history, capable of carrying on the socio-religious network (of symbols, rituals, etc.) and creating a mytho-historical time arc, that welds past, present and future into a continuous chain of self-sacrifices as part of a divine programme of probation, improvement, and fulfilment. The time of the martyr is a mythopoetic construction that intertwines circularity with an eschatological-messianic conception of time, promising a way out of the circle, once Mahdi, the Shi’ite messiah and hidden, twelfth Imam has arrived. Media—both how they are used (as soft power) and how they are depicted (by other media)—make a significant contribution to this construction of time. Nevertheless, one can find a whole range of films—either shot in Iran or by Iranian directors who left the country—that develop what I want to call counter-martyrographies, questioning the time manipulations of iconic state media, and ‘counter’ them by the use and the depiction of media techniques that, instead of perpetuating the (floating) boundary between state media of true witnessing and westoxified media of fake witnessing, bear witness to those who have no right to be remembered and redeemed as martyrs by state’s boundary building (and shifting) between insiders and outsiders.

Counter-Martyrographies

Who has the right to be remembered as a martyr by the dominant institutions and media, and whose stories are excluded? How to turn the grand narratives of revolution, war and martyrdom into minor or singular stories of revolt, grassroot movements, and dissidence? Who has the media power to make, unmake or remake martyrs, to transform them from insiders into outsiders (and vice versa)? Who has the monopoly on the ‘final cut’ (by means of media) that retroactively establishes a cause (for which somebody supposedly gave his/her life), converts the gaze, and creates a medial, senso-aesthetical archive of affects? What if martyrs are created by accidents that are retroactively transformed into sense making events and sacrificial acts? What if the hidden, displaced flipside of martyrdom is suicide (as a last exit strategy)? Much less doubt about the compatibility of martyrdom and suicide is left by Kazem Masoumi’s counter- or even radical anti-martyrography Ṭabl-i Buzurg Zīr-i Pā-i Chap/Big Drum Under Left Foot (2004). What the anti-sacred defence movie Big Drum Under Left Foot tackles quite directly at the end of the war film is suicide through the hand of the enemy: After realizing that he falsely suspected an Iraqi soldier of an ambush, the commander (Hossein Mahjoub) kills himself in the bunker with the hand grenade of the dying Iraqi soldier (). Thus, the film confronts us with a displaced narrative about the suicidal tendencies in the heart of the martyr welfare state, just as Ali Abbasi’s recent film Holy Spider (2022) develops a dark socio-pathology of martyrdom and purification phantasies as the death drive of a misogynist society.

Figure 4. Screen grabs from Ṭabl-i Buzurg Zīr-i Pā-i Chap/Big Drum Under Left Foot, 2004, Kazem Masoumi.

What if discourses of martyrdom are primarily invoked when it is a matter of turning a defeat into victory, transforming victims of state violence, suicidal tendencies or unintentional, contingent accidents into intentional, heroic (self-)sacrifices for a cause? The ‘Cinema Rex Fire Martyrs’ of 1978, the dead bodies of the Iranian military plane C-130 that crashed on 6 December 2005,Footnote50 or the 176 dead passengers of the Boeing 737 shot down on 8 January 2020 – in all these cases, and many more, the state sought to claim the victims as state martyrs and sacralize the bodies. In contrast to the message that Khomeini issued at the time, declaring the victims of the Rex Cinema Fire to be martyrs of the revolution Revolution who had ‘watered the roots of the tree of Islam with their blood’,Footnote51 Shahram Mokri’s film Jināyat-i bī-diqqat/Careless Crime (2020)—despite playing a game with poly-perspectivism and trans-temporal loops—leaves little doubt that those (probably more than) 400 burned at the Rex Cinema were no martyrs or necessary sacrifices, but casualties of a deadly interweaving of multiple probabilities: a conjunction of contingency (stuck doors, that lacked handles and opened inward; fire engines arriving late with an empty tank), carelessness, the capitalism of the culture industry (number of sold tickets was beyond standard) and a planned, religiously inspired crime, that—as a revenant in history—continues to suffocate the lives of the younger generation. With his technique of looping time, Mokri has found an adequate cinematic form to show how the mythological time of state martyrdom threatens and imprisons the younger generation again and again—also as an ideology that prevents times from passing. The time performances of the state propaganda’s media short-circuit past, present, and future into a mytho-historical loop of constant re-purification, just as cinemas—before Khomeini ‘rescued’ them as a means of education—were burned down and the casualties claimed as sacrifices for the Revolution. Mokri’s films—besides Careless Crime also Hujūm/Invasion (2017) and Māhī va Gurbah/Fish and Cat (2013)—confront us with a powerful and hidden machine whose mechanisms keep the characters trapped in loops, creating stagnation that transforms diachronicity in synchronicity. This time critical dimension of Mokri’s films will now be examined in more detail along Fish and Cat, a film that is particularly noteworthy in terms of its media depictions, and the differences they inscribe.

Like hardly any other film, Mokri’s internationally acclaimed, time-looped, one-long-take-horror-film Fish and Cat was deciphered by his audience—not least on social media platforms—in terms of socio-political implications. What the film basically demonstrates is the appropriation of a public space, a lakeside, by a community of young campers who transform this space into a counter-public sphere, only reserved for ‘insiders’, here in a subversive, dissident sense. At the same time, this closed community is highly porous, vulnerable to forgotten, insisting pasts and present threats, embodied by ‘hunters’, i.e. representatives of the older generations: Basijis, veterans, living martyrs of the sacred defence, hillbillies—who sneak around the lake like cats around fishes. Already the opening text insert of Mokri’s horror film tells us that the story is inspired by a real-life backwoods restaurant that served human flesh in Northern Iran.

What connects and separates the two worlds, is the perpetual travelling of the camera, which returns over and over again to the same locations, and by doing so, transforming them into time forks where the spatiotemporal looped trajectories of the characters intersect. Thus, the different generations are conjoined by a very powerful force that keeps all the characters trapped in intertwined loops. What they share is what separates them: space and time. What is important in this context is that the teenagers use completely different media than the older generation—cell phones, digital voice recorders, iPads, various headsets—and through those new socio-media-techniques they create a different kind of connectedness, also to the ghosts of the past. And this is where the counter-martyrography comes in.

The opening text insert of the film does not only tell us about a real-life backwoods restaurant (with dubious meat sources) that served as an inspiration for the film. It also tells us that the case fell into oblivion, ‘similar to other stories about murder and bloodshed’. There are many of these stories hidden in the woods and in the time structure of the film—untold, half-told or insisting stories of political dissidence and violence, haunting the characters like ghosts. There is even a real ghost called Jamshid, a former journalist, whom we see for eight minutes (1:42:00–1:50:00), communicating with the present via Nadiya, a girl that can see ghosts, and by the help of a digital voice recorder held by a reporter ().

The appearance of the ghost (long raincoat, long shawl) is a traceable marker, especially for the Iranian audience, pointing back to those more than eighty intellectuals (writers, translators, poets, political activists; among others, Dariush Forouhar and his wife Parvaneh Eskandari Forouhar) who were victims of the so-called ‘Chain Murders of Iran’ (qatl-hā-i zanjīrahʾī): a series of murders from 1988 to 1998 carried out by internal agents of the government. The fact that more and more critical intellectuals—like fishes coming to the surface—dared to express their opinions on public media became an opportunity for the governmental authorities and agents to ‘fish them out’. Thus, also Fish and Cat establishes a dual class system of media that creates different presents, pasts, and ghosts. Unlike the hunters, the fishes use new media—or make new use of old media—to re-member those martyrs of resistance (against the system) who have no right to be remembered by the state media, and who therefore rely on the witnessing techniques of a counter-public. New and old media techniques also criss-cross each other, for example, when a teenager is told by a representative of the hunters that cell phones are not working in the forest—while old telephone cables stick out of the ground, connecting the old generation. At the end of the film, however, there is a remarkable moment in which a new media technology brings the generations—outsiders and insiders—together: Fish and hunter, a teenage girl (Maral) and an old man sit leaning against a tree, connected by a cable that originates in an iPod. Both are listening to the same music, with one headphone in each ear ().

For a moment we get the chance to witness a utopia of trans-generational understanding, and Hamid seems to like the girl’s music (especially the song Fish and Cat by Pallett Group)—just as the movie theatre in Careless Crime seems to be the only place where the generations, just for a moment (as a brief possibility that flashes up) sit peacefully side by side.

But the idyll is deceptive. A few seconds later, we hear the girl’s thoughts, describing a vision of being slaughtered with a knife by Hamid, the old hunter. The imagery of her descriptions—‘My eyes are staring at the sky and blood is pouring out of my mouth and nose […]’ – evoke memories of another counter-martyr’s death, as has been documented by several mobile phone cameras on 20 June 2009: the dying of twenty-six-year-old Neda Agha-Soltan, who had been shot by a Basij member, and bled to death.

What Mokri’s counter-martyrography undertakes is to relate the dual class system of media (insider/outsider) no longer to the dichotomy ‘westoxified/purified’, but to different ways of remembering, witnessing, and dealing with the past. Instead of imagining an eternal return to a mythological past and to a ‘purified self’ (facilitated through shahādat), the digital socio- and mnemo-techniques used by the younger generation rely on body-media-relations that facilitate networked solidarity, shared (and thus re-appropriated) images, and viral transmissions of current witnessing. Memory becomes an effect of the present and the co-presence between the body (as a medium) and the medium (as a body), out of which relations to the past as an archive of forgotten, lost traces are created—while the state’s propaganda strives to close the past forever through final meanings and totalitarian conclusions. Counter-martyrographies retranslate the sacralizing vocabulary of martyrdom back into resistant, secular and material gestures of bearing witness to injustice. And it is about such a corporeal sign of witnessing, which has stubbornly resisted any appropriation by state propaganda, that the last section will be dealing with.

Between screen and street: the red hand

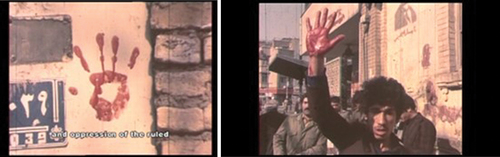

Throughout history, the ‘blood-red hand (print)’ has been—and continues to be—a strong sign and gesture of first-hand witnessing. Remarkably, we can trace the ‘microhistory’Footnote52 of this—also transculturally significant—sign of resistance and decolonization not only back to the street protests in Tehran around the Revolution 1979 (and to the ways it is well documented by numerous films and photographs, ), but even further back, to the popular cinema before 1979. Thus, we are dealing with the microstoria of a martyrological sign whose street history is closely intertwined with screen history—and particularly with the passionate screen martyrdom of the lūtī/lāt/jāhilī.

Figure 7. Caption: Kaveh Golestan, Untitled (Revolution ’78-’79 series), photograph, 1979, Tehran. © Kaveh Golestan, Courtesy of Archaeology of the Final Decade.

Figure 8. Screen grab from Conversation with the Revolution/Guftūgū bā inqilāb, 2011, Robert Safarian.

Let me give two examples: (a) At the end of Masoud Kimiai’s film Riza Mūtūrī/Reza Motorcyclist (1970), when Riza (Behrouz Vossoughi) is stabbed in a movie theatre, he leaves a memorable, indexical and iconic trace: a bloody handprint on the inner diegetic cinema screen—as if to pass on his blood testimony to the cinema audience, and turn them into witnesses (). (b) At the beginning of Gavazn-ha/The Deer (1974), when Qudrat (Faramarz Gharibian) is on the run from the police with a gunshot wound and a bag full of stolen money, he wipes his bloodstained hand on a house wall as if to leave a public trace of blood testimony. Remarkably, it was exactly this film that was shown before the Cinema Rex burned down in 1978 – and the casualties had been claimed as holy sacrifices for the state to come.Footnote53

What is crucial to my final argument is that this indexical as well as symbolic and iconic sign of the blood-red hand has been remarkably stubborn in resisting appropriation by state propaganda. As a corporal trace of violence that will (re-)appear in different times and movements (The Green Movement 2009, Jin, Jiyan, Azadî 2022ff.), the red hand (and its print) retained the ability to give a strong counter-statement to the state’s body- and bloodless, purified martyrography. As Olmo Gölz has worked out in detail, the martyr propaganda developed after 1979 and especially during the Iran-Iraq War (on murals, posters, photographs, in films and TV series) followed a strategic disembodiment of the martyr—in the sense of concealing the destructibility, vulnerability, and mortality of the soldier’s body through depictions of redeemed, smiling martyrs amid flowers of paradise and sweet musky fragrance, expressing the otherworldly bliss of purification, liberated from bodily torture and lower nature (nafs).Footnote54

Taking this into consideration, we can better grasp why the blood-red hand—as a body politics that remembers the resistant, shattered body—confronts us with the microhistory of a resistant sign and a sign of resistance that, until today, persistently eluded complete integration into the machinery of governmental imagery; in stark contrast to numerous symbols derived from Persian poetry, Sufi mysticism, and Islamic imaginaries (such as tulips, roses, candles, birds like doves, butterflies and moths) that were increasingly incorporated by the iconography of the IRI. In the gesture of showing or imprinting the blood-red hand, the sacredFootnote55 and the profane, the symbolic and the indexical intersect in complex ways.

Between screen and street, before and after 1979, the symbolism around the red hand provided an uncontrollable, resistant counter-narrative to the disembodied, abstract martyr symbols produced by the necropolitical rhetoric of the state. That is, we are dealing with a true counter-martyrography (rather than an anti-martyrography): The blood-red hand is committed to the dual class system of the media in that it very much follows the body politics of indexical transmission (at least at a first, bodily level), but at the same time refuses to be instrumentalized by a state propaganda rooted in a body politics of purification and abstraction from bodily dimensions. In addition, and perhaps most crucially: Unlike the symbols of governmental martyr imagery, the red hand continues to be preserved for general use: ‘socially sanctioned’Footnote56 as a ritual that helps to pattern the ‘social world’, as a class-transgressive, counter-hegemonic way to connect and as a ‘non-verbal channel’ or ‘style’Footnote57 that—between street, screen, and viral transmissions through social media—still coordinates the use of the body as a medium of bearing witness to injustice.

Conclusion with outlook

As has been shown, martyrs are not only highly contested bodies, they are also surrounded by diverse media techniques that compete for the right to re-make this body and transform it in a second, allegorical body. The visual propaganda machinery of the IRI—and the cultural industry of Sacred Defence in particular—has spared no effort to establish a dual class system of media and, accordingly, implement a two-world ontology of witnessing, opposing media for insiders and for outsiders, ‘purified’ media that guarantee the vision of transcendent truth and ‘westoxified’ media that provide fake witnessing. As was also shown, state propaganda spares no effort to keep the boundary between insider and outsider media in flux—in order to keep up with technology (and its possibilities).

Thus, the axiom ‘the medium is the message’ can also imply that within one medium—in our case: film—other media techniques are staged, depicted and negotiated, in order to ascribe (or deny) to them different qualities of creating witnesses and regulating the visibility of the martyr, as has been demonstrated with Hatamikia’s Damascus Time and Mahdavian’s Standing in the Dust. In contrast, the term counter-martyrographies has been used to examine films that challenge the iconic state media, questioning their monopoly on creating true witnesses through counter-hegemonic aesthetic strategies. Instead of perpetuating the boundary between state media (of true witnessing) and westoxified media (of fake witnessing), films like Mokri’s Fish and Cat apply, negotiate and depict (social) media techniques in order to facilitate gestures of witnessing that refer to those who have no right to be remembered as martyrs by the state. Finally, with the blood-red hand, a gesture and sign of witnessing has been found that, between the screen and the street, stubbornly refused to be coopted by the state propaganda of martyrdom.

‘Jin, Jiyan, Azadî’ (‘Woman—Life—Freedom’), the central slogan of the feminist, class-transgressive uprising in Iran, sparked by the murder of young Kurdish woman Jina Mahsa Amini (1999–2022) after her arrest by the ‘morality police’ (Gasht-i Irshād), just also means, that the majority of the population no longer wants to be instrumentalized by the martyr’s welfare state. The reclaiming of bodily autonomy inherent to the slogan challenges the necropolitical state doctrine of self-sacrifice in the name of Sacred Defence—and its monopoly on gestures and media techniques of witnessing. Many Shi’a symbols of martyrdom—even though they have been used throughout history also in the name of anti-establishment resistance—are replaced by revolutionary signs that stubbornly resist being appropriated by the IRI’s visual propaganda machinery. Remarkably, also the sign of the blood-red hand is re-emerging, going viral online and on the streets. Red hands were displayed prominently after security forces attacked students staging a sit-in at Sharif University on 2 October () and brought into play by protesting art students of Azad University Tehran on 9 October 2022 (). In examples like these, it becomes especially clear that the blood-red hand very directly challenges the necropolitical state doctrine of self-sacrifice in the name of holy defence and its monopoly on gestures and media techniques of witnessing. Instead of witnessing the achievements of the martyr’s welfare state, the blood-red hand bears witness to its injustice. And we can be curious to see when the blood-red hand will migrate again from the street (via social media) to the cinema screens, and back again, as was the case around and before the revolutionary years 1978/79.

With the black of your black eyes

I

Will write,

On every end of this garden:

‘there is always a hand writing for another hand;

There is always an eye that does not go to sleep’.

Khosrow Gholsorkhi, Sleeping in the Rain (Khuftah dar Baran)

(ca. 1972, translated by Golnar Narimani)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Robert Fisk, The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East (London: Harper Perennial, 2006), 356.

2 Ravinder Kaur, ‘Sacralising Bodies: On Martyrdom, Government and Accident in Iran’, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 20, no. 3 (2010): 442–60, 447.

3 Keith Levinstein, ‘The Revaluation of Martyrdom in Early Islam’, in Sacrificing the Self: Perspectives on Martyrdom and Religion, ed. Margaret Cormack (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 78–92, 79. It was the early Christians in the middle of the second century A.D. who, by their (more or less) voluntary death in the arena, appeared as witnesses to a higher truth, thus also giving a new meaning to the commonly used term for witness, namely martyr (Greek martys; Latin martyres). Thus, a term initially used in a juridical context was transformed into the new and until today more dominant meaning of blood testimony in the sense of ‘sacrificial death for the faith’.

4 Cf. Talal Asad, On Suicide Bombing (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), 52.

5 Asghar Seyed-Gohrab, Martyrdom, Mysticism and Dissent: The Poetry of the Iranian Revolution and the Iran-Iraq War 1980–1988 (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2021), 37.

6 Cf. Ehsan Yarshater, ‘Ta’ziyeh and Pre-Islamic Mourning Rites’, in Ta’ziyeh: Ritual and Drama in Iran, ed. Peter Chelkowski (New York: New York University Press, 1979), 88–94, 93.

7 Niklaus Larhier, ʻDas Theater der Askeseʼ, in Askese und Identität in Spätantike, Mittelalter und Früher Neuzeit, ed. Werner Röcke and Julia Weitbrecht (Berlin/New York: De Gruyter, 2010), 207–222, 209.Werner Röcke and Julia Weitbrecht (Berlin/New York: De Gruyter, 2010), 207–222, 209.

8 John Durham Peters, ‘Witnessing’, Media, Culture & Society 23, no.6 (2001): 707–723, 713.

9 In his speech ‘Jihad and Shahadat’ - delivered in 1963 in the Hidayat Mosque (Tehran)—the Shi’a liberation theologian Mahmud Taliqani raises the question of how the martyrs of Karbala managed to pass on their testimony when all witnesses to the vision of truth were slaughtered. Taliqani declares this impossible testimony to be a miracle of recording in ‘the system of creation’, combined with the obligation to continue the ‘chain of sacrifice toward evolution’. – Mahmud Taliqani, ‘Jihad and Shahadat’, in Jihād and Shahādat. Struggle and Martyrdom in Islam, ed. Mehdi Abedi and Gary Legenhausen (Houston: Institute for Research and Islamic Studies, 1986), 47–80, 68f.

10 Ali Mirsepassi, Intellectual Discourse and the Politics of Modernization: Negotiating Modernity in Iran (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 92.

11 Shari’ati, ‘Shahādat’, in Jihād and Shahādat. Struggle and Martyrdom in Islam, ed. Mehdi Abedi and Gary Legenhausen (Houston: Institute for Research and Islamic Studies, 1986), 153–229, 206, 213; Shari’ati, ‘A Discussion of Shahid’, in Jihād and Shahādat, 230–243, 235.

12 Ibid., 234.

13 Golbarg Rekabtalaei, Iranian Cosmopolitanism: A Cinematic History (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 235.

14 Quoted according to: Hamid Naficy, Social History of Iranian Cinema (Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2012), 7.

15 Mohamad Tavakoli-Targhi, ‘The Emergence of Clerico-Engineering as a Form of Governance in Iran’, Iran Nameh 27, no.2–3 (2012): 14f.

16 Cf. Jalal Al-e Ahmad: Gharbzadegi [Weststruckness] (Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers, 1997).

17 Negar Mottahedeh, Displaced Allegories: Post-Revolutionary Iranian Cinema (Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2008), 56.

18 ‘Moreover I have put forward the notion of necropolitics and necro-power to account for the various ways in which, in our contemporary world, weapons are deployed in the interest of maximum destruction of persons and the creation of death-worlds, new and unique forms of social existence in which vast populations are subjected to conditions of life conferring upon them the status of living dead. […] under conditions of necropower, the lines between resistance and suicide, sacrifice and redemption, martyrdom and freedom are blurred’. – Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics (Durham/London: Duke University Press 2019), 92.

19 Cf. Baldessare Scolari, State Martyr: Representation and Performativity of Political Violence (Nomos: München, 2018).

20 Seyed-Gohrab, Martyrdom, Mysticism, and Dissent, 26f.

21 On the recurring mystical theme of the ‘moth and the candle flame’ compare also: Seyed-Gohrab, Martyrdom, Mysticism, and Dissent, 61f.

22 Ibid., 26.

23 Pedram Partovi, Popular Iranian Cinema before the Revolution (London/New York: Routledge, 2017), 21.

24 Kaur, ‘Sacralising Bodies: On Martyrdom, Government and Accident in Iran’, 447.

25 If there is one body that suffered a particularly spectacular, multifaceted martyrdom in the Iranian cinemas of the 1960s and 1970s, it is the body of the so-called lūtī (alternatively lāt, dash-mashtī or jāhil). However, it is not only a film genre character we are dealing with, but also an extra-cinematic social phenomenon of vernacular (anti-, pre- and high-)modernity, ‘tracing back to pre-Islamic Iran’: ‘The line between luti and laat is a thin and often blurry one. Laat (meaning “ruffian”) is in a sense the villainous opposite of luti, and often, one neighborhood’s luti is another neighbourhoodneighbourhood’s laat. Both lutis and laats have been used as middlemen between rival land-owners, clerics, and government officials throughout Iranian history. […] Over time, the term luti came to refer to two distinct groups: the first group was composed of entertainers (jugglers, clowns), while the second group was formed by the urban social bandits in local neighbourhoods’. – Narges Bajoghli, ‘The Outcasts: The Start of “New Entertainment” in Pro-Regime Filmmaking in the Islamic Republic of Iran’, Middle East Critique 26, no.1 (2017): 61–77, 69f.

26 Cf. Arash Davari, ‘A Return to Which Self? Ali Shari’ati and Frantz Fanon on the Political Ethics of Insurrectionary Violence’, Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 34, no.1 (2014)), 86–105.

27 McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Men (London/New York: MIT, 1994), 7; Cf. Kaveh Abbasian, ‘The Iran-Iraq War and the Sacred Defence Cinema’ (lecture given on 16 February), Journal of the Iran Society, Vol. 22, no.16 (September 2017): 34–40.

28 Morteza Avini, interview by Farabi Editorial Team, ‘Video vs. Man’s Historical Resurgence’ (ویدئو در برابر رستاخیز تاریخی انسان), Farabi 5, no.1 (Winter 1993): 117. Quoted according to Amirali Ghasemi, ‘Honar-e Jadid: A New Art in Iran’, https://mohit.art/video-as-an-artistic-medium-in-iran-from-the-1990s-to-the-mid-2000s/ (accessed November 15, 2022).

29 Michael Fischer, Iran: From Religious Dispute to Revolution (Cambridge/Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1980), 13f.

30 Walter Benjamin coined the term ‘Aesthetization of Politics’ as a characteristic of fascist regimes, in contrast to the ‘politicization of aesthetics’ associated with revolutionary practices. – Walter Benjamin, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Its Mechanical Reproducibility’, in Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, Vol. 4 1938–40, eds. Howard Eiland and Michael Jennings (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006), 251–283, 270.

31 Nacim Pak-Shiraz, Shi’i Islam in Iranian Cinema: Religion and Spirituality in Film (London: I.B. Tauris, 2011), 47f.

32 Pedram Partovi, ‘Martyrdom and the “good life” in Iranian Cinema of Sacred Defence’, Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 28, no.3 (2008): 513–532, 519.

33 Pierre Bourdieu, Practical Reason: On the Theory of Action (Stanford/California: Stanford University Press, 1988), 113.

34 Cf. Kevan Harris, A Social Revolution: Politics and the Welfare State in Iran (Oakland: University of California Press, 2017). – Martyrdom was monopolized and institutionalized by the architects of the martyr’s welfare state, among other things, through the establishment of a Martyrs’ Foundation (Bunyād-i Shahīd).

35 Bourdieu, Practical Reason, 53.

36 Cf. Narges Bajoghli, Iran Reframed: Anxieties of Power in the Islamic Republic (Stanford/California: Stanford University Press, 2019), 65ff.

37 Bourdieu, Practical Reason, 114.

38 Annabelle Sreberny-Mohammadi, ‘Small Media for a Big Revolution: Iran’, International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 3, no.3: The Sociology of Culture (Spring 1990): 341–371.

39 Cf. Blake Atwood, The Secret Life of Videocassettes in Iran (Cambridge/Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2021).

40 Cf. Nikki Akhavan, ‘From Defense to Intervention: Iran-Iraq War Cinema in a New Millenium’, lecture on OCT 28 (2022), as part of the Elahé Omidyar Mir-Djalali Lecture Series (University of Toronto).

41 Cf. Varzi, Warring Souls: Youth, Media, and Martyrdom in Post-Revolutionary Iran (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006); Pak-Shiraz, Shi’i Islam in Iranian Cinema.

42 ‘Iranian nationalism was formed around khāk-i pāk-i vaṭan (the pure soil of homeland), which reconfigured vaṭan from its earlier Perso-Islamic meaning as one’s birthplace to a modern territorialized homeland imagined as a female body. This new vaṭan was a territory with clear borders, within which the collectivity of national brothers (barādarān-i vaṭani) resided’. – Afsaneh Najmabadi, Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of Iranian Modernity (Berkeley/Los Angeles/London: University of California Press, 2005), 97f; Cf. also: Michelle Langford, Allegory in Iranian Cinema (London: Bloomsbury, 2019), 174f.

43 See ‘Negotiating Gender During Times of Crisis: Visual Propaganda from the Iran-Iraq War to Covid-19’, this issue’s article by Kevin Schwartz and Olmo Gölz.

44 At the end, the son will get a chance to truly sacrifice himself for the motherland, when he prevents the bomb-laden cargo plane from crashing over Iranian soil by detonating himself together with the plane (above deserted land)—after all the Iranian hostages have been released to freedom with parachutes.

45 Cf. Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London/New York: Verso, 2006).

46 Cf. Christoph Kucklick, Die granulare Gesellschaft: Wie das Digitale unsere Wirklichkeit auflöst (Berlin: Ullstein, 2016).

47 Cf. Michel Foucault, Dispositive der Macht: Michel Foucault über Sexualität, Wissen und Wahrheit (Berlin: Merve, 1978), 35, 106 (Translation by the author).

48 Shahram Mokri, ‘A Shadow for Invisible Films: A Way to Break the Monopoly of Image Production in Iran’, in Counter-Memories in Iranian Cinema, ed. Matthias Wittmann and Ute Holl (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021), 216–228, 226.

49 See also: Matthias Wittmann, ‘Towards an Impure Memory: An Archaeology of Counter-Memories through Telescoping Lenses’, in Counter-Memories in Iranian Cinema, Wittmann and Holl ed. 121–145, 137ff.

50 Cf. Ravinder Kaur, ‘Sacralising Bodies’, 447.

51 Quoted according to: Hamid Algar (ed.), Islam and Revolution: Writings and Declarations of Imam Khomeini (Berkeley: Mizan Press, 1981), 231f.

52 Cf. Carlo Ginzburg, ‘Microhistory: Two or Three Things That I Know about It’, Critical Inquiry 20/, no./1 (1993), 10–35.

53 Cf. Ehsan Khoshbakht’s documentary film Filmfarsi (2019).

54 Cf. Olmo Gölz ‘Gemartert, gelächelt, geblutet für alle: Der Märtyrer als Gedächtnisfigur in Iran‘, in Gewaltgedächtnisse: Analysen zur Präsenz vergangener Gewalt, ed. Nina Leonhard and Oliver Dimbath (Wiesbaden: Springer, 2021), 127–150, 133ff.

55 When it comes to Shi’a Islamic framings, the bloody hand sign can be brought into dialogue with several motifs: the bloody feather of the dove as a form of transmission; the right hand of ʿAbbas; the hand of Fatimah; drumming blood hands as a motif in war poems; sīnah zanī (breast beating) etc.

56 Kaur, ‘Sacralising Bodies’, 447.

57 Mary Douglas, Natural Symbols: Explorations in Cosmology (London/New York: Routledge, 1996), 53, 71ff.