ABSTRACT

This study aimed to explore ESL teachers’ perceptions of online teaching during the COVID-19 outbreak in Hong Kong. A qualitative multiple-case study approach was employed, focusing on the online teaching experiences of three teachers in primary school contexts. Through semi-structured interviews and thematic analysis, rich data were collected and analysed. The findings revealed five prominent challenges faced by the teachers, including inadequate infrastructure, limited technical support and training, classroom management issues, teachers’ limited technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK) in ELT, students’ unreadiness and lack of parental support. The study also identified three opportunities arising from online teaching, such as changes in teachers’ attitudes and beliefs in technology, opportunities for teacher learning and experimenting with online teaching practice for pedagogical innovations. Despite the significant challenges encountered, the teachers perceived the online teaching experiences as opportunities to enhance their teaching competence with technology. This study has substantial implications, calling for strategic governmental measures to improve online learning in schools, highlighting the need to integrate technology-focused pedagogies into teacher education, revising outdated school curriculums to enhance students’ digital literacy, providing financial support for disadvantaged students, encouraging parental involvement in online learning and fostering collaborative professional learning communities to enhance English teachers’ TPACK.

Introduction

In the 2019–20 school year, given the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Hong Kong Education Bureau suspended classes after the Chinese New Year Holiday in 2020 (i.e. late January 2020) to safeguard school members. In order to suspend classes without suspending learning (Education Bureau, Citation2020), schools adopted synchronous or asynchronous online instructional approaches as alternatives. Nevertheless, prolonged school closure presented unprecedented challenges to most schools and teachers because all teaching and learning activities had to be converted into e-learning. Few schools and teachers were sufficiently prepared for such a substantial need for full online instruction, despite the government having invested a total of HK$14 billion in launching a series of four strategies on information technology in education (ITE) for over 20 years (Yeung, Citation2020) to build infrastructure (Education and Manpower Bureau, Citation1998), provide e-resources (Education and Manpower Bureau, Citation2004), train e-leadership (Education Bureau, Citation2008) and boost training in e-pedagogies (Education Bureau, Citation2015). Thus, the education policy, school practice, and teacher training failed to respond to the situation.

English language teachers, in particular, experienced notable strain (MacIntyre et al., Citation2020) due to teaching a second language, alongside other pedagogical and administrative tasks. Although English is taught as a second language in Hong Kong (Education Bureau, The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Citationn.d.), reflecting the city’s bilingual environment, Cantonese, being the mother tongue, is culturally predominant in the community. Therefore, instruction, especially for younger students, often weaves elements from both languages to enhance understanding.

The role of English language teachers in local primary schools is multifaceted and dynamic. Besides imparting English language skills to students, teachers significantly contribute to curriculum development, innovative lesson design, and student performance evaluation through both formative and summative assessments. Pedagogical approaches such as the Communicative Language Approach and Task-based Language Teaching, endorsed by the Education Bureau (Curriculum Development Institute, Citation2017), are widely used in the local primary classrooms to emphasise real-world communication and interactive activities, thereby promoting language acquisition.

During the COVID-19 outbreak, local English language teachers—much like their counterparts worldwide—experienced tremendous challenges as their original teaching plans and lesson designs, which heavily relied on face-to-face interactions with young learners, were disrupted. In addition, their knowledge and skills of technology integration in online teaching were challenged, and their abilities to provide technical support to students were suddenly required. Under such a strenuous situation that required a shift from in-person to online teaching, English language primary school teachers surely underwent substantial changes in their cognitions about English language teaching and education, questioned the effectiveness of online teaching and felt hesitant to teaching online.

Given the significant influence of teachers’ cognitions on the development of English language education in primary schools, it is highly worth investigating how ESL teachers have perceived the transition to online teaching amid COVID-19 in terms of the potential challenges and opportunities. Despite the importance of this topic, there has been a dearth of research exploring the impact of this adaptation on ESL teachers’ cognitions, particularly in the primary school context. Addressing this critical research gap, this paper, as part of a broader study, seeks to understand how ESL teachers in Hong Kong primary schools have perceived the shift to online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic and how they have viewed these changes in terms of challenges and opportunities for English language education.

Language teacher cognition

Studies about teacher cognition have been flourishing since the late 20th century. The earlier research focused on examining the relationship between teachers’ in-class behaviours and students’ learning outcomes to investigate behavioural traits of effective teaching for generalising models of efficient teachers (Borg, Citation2006). Later, research shifted towards examining teachers’ mental constructs and cognitive processes (e.g. Jackson, Citation1968; Kounin, Citation1970) with the development of cognitive psychology in the late 1960s.

In the 1980s, research related to teachers’ thinking emerged to investigate teachers’ decision-making (e.g. Shavelson & Stern, Citation1981). Clandinin and Connelly (Citation1987) argued that teachers’ thinking is based on their theories and beliefs, which are in turn shaped by their personal experiences and life histories. These are then transformed into personal practical, knowledge.

Moreover, other research has revealed that teacher knowledge contributes to teachers’ capacity to shape curricula and solve practical teaching problems (Elbaz, Citation1981). L. Shulman (Citation1987) concluded that teacher knowledge includes an awareness of the subject matter, general pedagogy, curriculum, learners’ features, the contexts and ends of education and pedagogical content knowledge (PCK). Among these, PCK is the most influential to teachers’ cognitions as it represents ‘the blending of content and pedagogy into an understanding of how particular topics, problems, or issues are organised, represented, and adapted to the diverse interests and abilities of learners, and presented for instruction’ (p.8) and ‘implies that teachers transform their knowledge of the subject matter into a form which makes it amenable to teaching and learning’ (Borg, Citation2006, p. 19).

Later, researchers turned towards teachers’ practical theories, beliefs and attitudes in order to understand their cognitions. At the same time, the importance of contextual factors was highlighted as teachers’ decision-making in natural classroom settings may be constrained and facilitated by existing or emerging (Clark, Citation1986).

As a whole, research on teacher cognition has covered an array of constructs and concepts, revealing the phenomenon’s complexity. Through understanding the different factors influencing teachers’ cognitions, Borg (Citation2006) concluded that language teacher cognition concerns ‘what language teachers think, know and believe—and of its relationship to teachers’ classroom practices’ (p.1). Moreover, teachers’ ‘self-reflections’ (Kagan, Citation1990, p. 419) on their learning, professional training and teaching experience shape their cognition, leading to certain practices. Hence, research into language teachers’ cognitions can yield insights into the relationship between intentions and behaviour, and reveal how language teachers perceive educational innovations (Borg, Citation2006).

While the practices of language teachers are contingent upon their knowledge, beliefs and thoughts, their cognitions and practices do not necessarily always align, which is attributed to the intermediary role of contextual factors. Moreover, this relationship is not rigidly unidirectional, as teachers’ cognitions are also moulded by classroom occurrences (Borg, Citation2006).

With an extensive review of the substantial literature on language teacher cognition in grammar teaching and literacy instruction, Borg (Citation2006) proposed a language teacher cognition framework which describes three significant aspects that shape such cognition. They are schooling, professional coursework and classroom practice influenced by contextual factors. Besides, the framework indicates that a language teacher’s pedagogical beliefs and teacher knowledge contribute to decision-making and shape cognition. These two aspects are especially important for understanding how ESL teachers integrate technology into online teaching and are further discussed below.

English language teachers’ pedagogical beliefs, second language acquisition (SLA) and technology use

When English language teachers integrate technology into their instructional practices, they often encounter unique considerations that set them apart from teachers in other subject areas. This distinction arises from their pedagogical beliefs, which are shaped by a diverse range of theories on SLA. These theories play a pivotal role in shaping the specific ways in which technology is utilised within and out of the English language classroom.

For example, ESL teachers who adhere to the Behaviorist Theory (Skinner, Citation1957) and agree with the analogy of learning as a process of habit formation might adopt a traditional teaching system with technology. They could use drill-and-practice software or flashcard apps for repetitive practice and immediate feedback (Semple, Citation2000).

On the other hand, teachers who credit Krashen’s (Citation1982) Input Hypothesis might utilise authentic audio resources, online videos, reading materials, or language learning apps. These tools provide comprehensible input at levels slightly above students’ current competence.

Informed by the Interaction Hypothesis (Long, Citation1996), which highlights the importance of interaction and negotiation for meaning in language acquisition, some teachers may use technology to facilitate interactive communication. Such tools as online discussion forums, video conferencing, and social media can be particularly useful in this regard.

Additionally, those who value the Sociocultural Theory (Vygotsky, Citation1978) could adopt collaborative tools, such as Google Docs or learning management systems (LMS) to encourage collaboration. They might also incorporate websites for exploring cultural contexts (Semple, Citation2000).

These examples show how SLA theories can influence and shape pedagogical practices and beliefs, particularly in the integration of technology in ESL teaching.

Therefore, in response to the sudden shift to online teaching necessitated by the COVID-19 crisis, ESL teachers leveraged their existing pedagogical beliefs, informed by various SLA theories, to employ technology in diverse ways for educational purposes within their specific teaching contexts.

However, to effectively use technology in a way that aligns with their pedagogical beliefs in online teaching, ESL teachers need to possess the necessary knowledge and skills, which would enable them to harness technology effectively to achieve a range of teaching objectives.

TPACK as the essential teacher knowledge for online teaching

To understand ESL teachers’ cognitions during online teaching, the specific knowledge they possess to conduct online teaching must be considered. Online teaching is highly related to integrating technology into teaching and e-learning in the curriculum. They all require teachers’ knowledge and skills to leverage the affordances of technology as media or tools for teaching and learning. Mishra and Koehler (Citation2006) argued that successful technology integration hinges on how well teachers master the specific knowledge to ‘reconfigure not just their understandings of technology but of all three components (of content, pedagogy and technology)’ (p.1030). This essential teacher knowledge is referred to as technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK, or TPACK). Built on L. S. Shulman’s (Citation1986) pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), TPCK is a kind of emergent knowledge resulting from the interplay of content knowledge (CK), pedagogy knowledge (PK) and technology knowledge (TK), but transcends all three (Mishra & Koehler, Citation2006). The three knowledge domains are not viewed separately but rather overlap to form new knowledge constructs in the emergent concept. Hence, they are ‘pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), technological content knowledge (TCK), technological pedagogical knowledge (TPK) and technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK)’ (p.1026).

In the application of the seven constructs of TPCK within the context of ESL instruction, CK, being ‘knowledge about the actual subject matter that is intended to be learned or taught’ (Angeli et al., Citation2016, p. 15), encompasses a diverse array of elements. These include phonetics, grammatical structures, the four cardinal English language skills, communication techniques and cultural aspects pertinent to the language (van Olphen, Citation2008).

PK, which pertains to the understanding of teaching strategies and learning practices (Angeli et al., Citation2016), refers to the practical knowledge required for the English curriculum and lesson plan design, the management of classroom dynamics in an English learning setting and the application of different literacy approaches underpinned by SLA theories.

TK, defined as the ‘knowledge about operating digital technologies’ (Angeli et al., Citation2016, p. 15), equips ESL teachers with the skills necessary for using Web 2.0 and computer-mediated resources effectively for teaching. This includes communication, sourcing online literacy resources and manipulating digital tools for the creation of pedagogical materials. Mastery of such technology-driven competencies is crucial in the modern education landscape.

PCK, which refers to the ‘knowledge of pedagogy that is applicable to the teaching of specific content’ (Koehler & Mishra, Citation2008, p. 14), implies that within the ESL context, teachers must employ a variety of teaching approaches, methods and strategies tailored to distinct language skills and components. For instance, the communicative approach may be adopted for grammar instruction, the process writing approach for writing and self-regulated strategies for reading. This diversification of teaching techniques is essential for addressing the multifaceted nature of language learning.

TCK, defined as ‘a deep understanding of the manner in which the subject matter (or the kinds of representations that can be constructed) can be transformed by the application of technology’ (Koehler & Mishra, Citation2008, p. 16), pertains to the knowledge of new literacy representations that have arisen due to technological advancements. This includes multiliteracies and new literacies, with such examples as webpages, fanfiction, blogs, and instant messaging illustrating these emerging text formats. Understanding these formats is crucial to effectively integrating technology into language teaching.

TPK is described as ‘an understanding of how teaching and learning change when specific technologies are employed…a deeper comprehension of the constraints and affordances of technologies and the disciplinary contexts within which they operate’ (Koehler & Mishra, Citation2008, p. 16). It assumes a distinct form in the ESL context. It pertains to the knowledge required for leveraging educational technologies or repurposing them to fulfil diverse pedagogical objectives in the teaching and learning process. Examples include the use of mobile devices to augment collaboration, the Internet as a research tool, and video conferencing platforms for communication.

Finally, TPCK is ‘the contextualised and situated synthesis of teacher knowledge about teaching specific content through the use of educational technologies that best embody and support it in ways that optimally engage students of diverse needs and preferences in learning’ (Angeli et al., Citation2016, p. 16). In the ESL context, teachers possessing TPCK should be able to use technology to represent linguistic and cultural concepts, leverage socio-constructivist philosophies in teaching and apply computer-assisted language learning to address language acquisition challenges. They should also recognise students’ prior knowledge, understand SLA theories and capitalise upon emerging technologies to advance learning (van Olphen, Citation2008)

The TPCK framework has been widely adopted as a theoretical and analytical framework to assess and develop pre- and in-service teachers’ knowledge and skills in technology integration (e.g. Mouza, Citation2016; Niess, Citation2012; Pamuk, Citation2012). The expanding literature on TPACK for investigating authentic classroom teaching has been developed with ESL/EFL (e.g. Asik, Citation2016; Paneru, Citation2018; van Olphen, Citation2008; Wang, Citation2016; Wu & Wang, Citation2015).

English language teaching cognition (ELTC) about online teaching

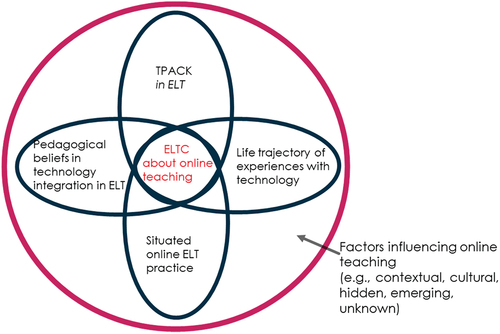

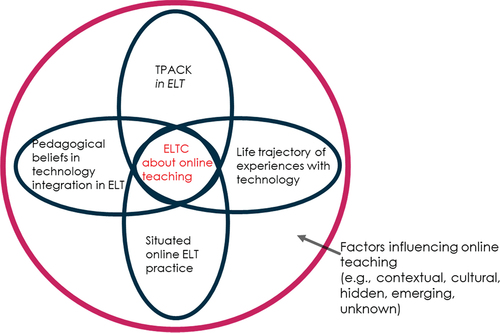

In this study, the constructs of Borg’s (Citation2006) language teacher cognition framework and the TPCK framework (Mishra & Koehler, Citation2006) are incorporated to form an enhanced framework, known as the English language teaching cognition (ELTC) about online teaching () to guide the investigation of teachers’ perception of online teaching amid COVID-19.

Further to emerging contextual factors, the enhanced framework indicates four significant aspects affecting ELTC in terms of technology integration. First, it represents an ESL teacher’s life trajectory of their experiences with technology. This includes their personal digital experiences, experiences of learning supported by technology in past schooling and professional IT training.

Second, it is an English language teacher’s pedagogical beliefs in technology integration in ELT. This aspect depicts how the teacher’s existing perception and beliefs of effective technology integration practices are influenced by their pedagogical beliefs about how best to teach children learning a second or additional language, which is based on their understanding of SLA theories. For example, if the teacher believes that children best learn a second language through behaviour building, they may use technology to provide learning opportunities for drilling and rehearsing the target language items. If the teacher perceives interaction to be the optimal method, they may use technology to enhance collaborative learning and idea sharing among students.

Third, an ESL teacher’s TPCK in ELT refers to their knowledge and skills of integrating technology into teaching various language skills and elements of the language effectively in their teaching context.

Fourth is an ESL teacher’s situated online ELT practice, which allows them to implement their beliefs in technology use in teaching and provides opportunities for reflecting on the effectiveness of the actual online teaching practice with technology for adjustments of future online teaching.

As shown in , the four aspects intersect with one another, indicating their interrelationship to influence and shape ELTC about online teaching. On the one hand, an ESL teacher’s life trajectory of experiences with technology essentially influences and shapes their pedagogical beliefs of technology integration in teaching. On the other hand, it informs the teacher’s ICT knowledge and skills (TK), as well as their knowledge about the change in literacy with the advent of technology (TCK). It further builds up the teacher’s TPACK in ELT and prompts particular technology use in situated online teaching. Last, but by no means, the entire system is influenced by various contextual, cultural, hidden, emerging and unknown factors to form ELTC about online teaching.

The study

Research purpose and question

Considering the complicated factors that influence ELTC about online teaching, this study addresses the following research question by studying three teacher participants’ experiences of online teaching:

What challenges and opportunities did English language teachers face in online teaching in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak?

Methods

This study adopted a qualitative multiple-case study approach (Creswell, Citation2014) to investigate the teaching experiences of ESL teachers in both synchronous and asynchronous virtual teaching contexts during the spread of COVID-19. This approach allowed for a detailed, contextual analysis of each case, while also enabling cross-case comparisons.

The study was framed in Chronotope II, a theoretical and methodological framework that allows for an understanding and interpretation of language learning and literacy practices by examining the intricate interplay of social, cultural and historical factors within educational contexts, with a particular emphasis on the spatio-temporal relationship (Kamberelis & Dimitriadis, Citation2005). This framework supports the analysis of how these factors, in the context of the shift to online teaching during the pandemic, impacted the teaching experiences of ESL instructors.

Moreover, this study embraced a social constructionist epistemology, which asserts that reality is not a fixed entity, but is rather constructed through collaborative interactions between the researcher and the researched (Hatch, Citation2002). This perspective allows for a nuanced understanding of the teachers’ experiences, acknowledging that these are shaped by, and contribute to, their individual and shared realities. This multifaceted approach to understanding teachers’ experiences in the online teaching context can provide valuable insights for policymakers, teacher educators, school administrators, and practitioners in navigating future disruptions in the teaching and learning landscape.

Participants

Sampling strategy

The participating teachers were selected under two criteria to ensure that they had witnessed and experienced the COVID-related teaching challenges which occurred in the middle of the school year and could provide detailed information about how their schools and the English panels responded to the situation.

The participant was teaching in a local primary school in the 2019-20 school year;

The participant was a core member of the emergency committee at the senior administrative level for sustaining English teaching and learning in school amidst the influence of COVID-19.

Due to the unprecedented situations which occurred during the pandemic, including the school lockdown, restrictions on in-person interactions and social distancing, the feasibility of conventional recruitment strategies, such as random, stratified and quota sampling, faced tremendous challenges. Convenience and snowball sampling became the most practical approaches (Yin, Citation2014). Although both are non-probability sampling strategies, convenience sampling allowed me to recruit from my own professional network and snowball sampling extended recruitment through the social networks of the participants’.

During the recruitment process, I leveraged my past experience working in several primary schools to reach out to former colleagues at different schools. At first, many declined my invitations due to the overwhelming online teaching workload during the pandemic. However, some redirected my invitation to their own colleagues. Finally, three participants—Jane, Fred and Kenny (pseudonyms)—were recruited from three different primary schools. Jane was a former colleague, Fred was referred by another former colleague and Kenny was introduced to me by my husband, also a teacher. The brief backgrounds of the participants and their teaching contexts for reference are as follows.

Participants’ backgrounds and teaching contexts

Jane

Jane was the English department head at a primary school in a low-income area in Kowloon. She had fourteen years of teaching experience. During COVID-19, she was teaching Primary 1, 3 and 5 classes where students had low English abilities and little family support.

Jane’s school provided basic technology, such as computers and tablets. In the 2018–19 school year, they piloted a BYOD (bring your own device) scheme in Jane’s two elite classes. However, the school generally adopted a traditional teaching approach. Before the pandemic, most teachers, including Jane, had limited experience with educational technology, mainly using PowerPoint and occasional apps for polls, games or quizzes. The school promoted e-learning through a top-down approach with prescribed guidelines and lesson plans.

Jane’s pre-pandemic classroom teaching incorporated some elements of the Situational Language Teaching approach, moving through presentation, practice and production stages. She often introduced new grammar structures using real-world situations. To support diverse students, Jane sometimes codeswitched to Cantonese, the students’ first language, to clarify vocabulary and grammar points. While also maintaining some traditional drilling with published and custom worksheets, Jane aimed to develop communicative abilities through simulated scenarios and language games.

In February 2020, Hong Kong schools closed due to the outbreak. Jane’s school was unprepared. To sustain teaching and learning, teachers created asynchronous video lessons on Google Classroom with textbook exercises for self-study. The arrangement continued until early August 2020. After basic in-house training during a two-week summer break, the school began live online teaching for core subjects, including English, which was then expanded to all subjects with a full timetable by December 2020.

Fred

Fred was an ESL teacher with four years of teaching experience at a traditional private primary school on Hong Kong Island. He taught a Primary 3 class during the pandemic. The English proficiency of his (mostly middle class) students was above average.

Fred’s classroom teaching incorporated elements of both the Situational Language Teaching and Task-based Language Teaching approaches. Fred often had his advanced students share useful writing ideas and vocabulary about a topic before they wrote individually and creatively.

Before the pandemic, teachers at Fred’s school depended on such traditional materials as textbooks and worksheets, with limited educational technology experience among staff and students. As such, the pandemic immediately disrupted teaching and learning activities.

Soon after the school closure, the school formed an IT team, which included Fred, to support online teaching. The team quickly conducted simple workshops to teach the staff basic technological skills and tools for asynchronous online teaching. As in Jane’s school, the teachers struggled to create video lessons for core subjects uploaded on YouTube for students to self-learn. The one-size-fits-all approach, with only one set of videos for each level of students without differentiation of difficulties and interaction, was not very useful because the learning predominantly relied on students’ self-discipline.

With help from a start-up in developing an online homework system, the school shifted to real-time online teaching when the 2020–21 school year commenced.

Kenny

Kenny was the English department head and e-learning coordinator of a primary school in the New Territories. His students were mainly middle-class, with above-average English proficiency and supportive families. Kenny taught Primary 4 and 5 classes during the pandemic. He had roughly six years of teaching experience.

Before COVID-19, Kenny incorporated Task-based Language Teaching (TBLT), Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) and the Flipped Classroom model. He designed meaningful tasks to help students relate learning to real life. Kenny occasionally asked students to conduct projects to learn more about other subject contents (e.g. history, science and geography) in his Primary 5 class. To prepare his students’ learning, Kenny assigned pre-lesson homework, like watching relevant videos with simple tasks to complete, before in-class discussions and project work. He also integrated digital games and technology into lessons to enrich students’ learning. The school used textbooks plus tailor-made booklets with e-learning elements for each student level to support pre-, during- and post-task learning activities.

A few years before the pandemic, Kenny began promoting e-learning at his school. He organised in-house professional training workshops and shared digital materials and ideas with his colleagues. Although his school had already initiated e-learning before the pandemic, the abrupt shift to online teaching still worried the staff. Kenny quickly ran workshops to equip teachers with basic online teaching skills. Immediately following the school closure in 2019, his school conducted synchronous online teaching for the core subjects, which was soon expanded to all subjects under a regular timetable. A summary of the three participants’ demographics and teaching contexts is shown in .

Table 1. An overview of participants’ demographics and teaching contexts.

Ethical consideration

The three participants voluntarily consented (in written form) to participate in the study after being fully informed of the research aim, data collection procedures and intended uses of the data. The recruitment process strictly followed the university’s ethical codes and procedures to protect the rights of the participants. Their identities were protected through pseudonyms and any potential identifying details were removed from the interview transcripts. All the collected data were kept confidential and stored securely with access restricted to only the primary researcher. The participants were also informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. Furthermore, the research design and methodology received ethical approval from the university’s human research ethics committee prior to the commencement of the study.

Data collection strategy

Three one-to-one semi-structured interviews (Silverman, Citation2010) were conducted via Zoom video conferencing in November and December 2020 to allow for in-depth data collection while adhering to pandemic safety guidelines (Jane: 34 minutes; Fred: 48 minutes; Kenny: 1 hour 36 minutes). First, semi-structured interviews were adopted because of their flexibility in collecting rich, descriptive data (Hamilton & Corbett-Whittier, Citation2013) about the participants’ lived experiences. Moreover, a semi-structured format with open-ended questions allowed the participants to express their views and enabled me to probe for further explanation and understanding. Besides, selecting video conferencing as a channel to conduct interviews addressed health and safety concerns and enabled the recording of both verbal and non-verbal data.

In each interview, I asked predetermined open-ended questions based on the study’s interview protocol which contained prompts covering the four aspects described in the guiding framework of ELTC about online teaching (Appendix 1). Follow-up questions tailored to each participant’s specific responses were added, where necessary, to generate rich data in natural conversations. The entire process facilitated an understanding of the natural world by ‘obtaining descriptions of the life world of the interviewee to interpret the meaning of the described phenomena’ (Kvale & Brinkmann, Citation2015, p. 6).

The interviews were conducted in Cantonese (the participants’ first language) so as to enable the natural and comfortable expression of ideas (Lopez et al., Citation2008). As I shared this same first language and being the interviewer and an insider in the field, I was able to translate the interview data into English, comprehending nuanced meanings shaped by shared cultural and contextual understandings and then translating without altering original meanings (Birbili, Citation2000; Squires, Citation2009). Where necessary, follow-up calls were made to clarify meanings and details with the participants. Afterwards, the translated interview data were examined by the participants through member-checking to ensure validity (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985).

Data analysis

Two levels of analysis, within- and cross-case, were conducted. In each within-case analysis, three steps suggested by Silverman (Citation2010) were adopted. First, the data were thoroughly read through as a stand-alone entity. Then, they were reduced by labelling and grouping through open coding (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990). The coding process involved line-by-line and segment-by-segment examinations of the transcripts so as to label or name significant units in words, phrases or sentences relevant to the research topic as codes. The codes could be descriptive, conceptual, theoretical, and metaphorical. Finally, the codes were further examined to identify key themes which were conceptualised into a framework of the case (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008).

In the cross-case analysis, the findings of the three teachers’ cases were compared and contrasted to identify similarities and differences. The process aimed to interpret patterns and relationships between the three cases so as to arrive at analytic generalisations about the challenges and opportunities the teachers experienced in online teaching, as well as to establish a theory across cases to explain ESL teachers’ cognition about online teaching in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak (Yin, Citation2018).

Findings

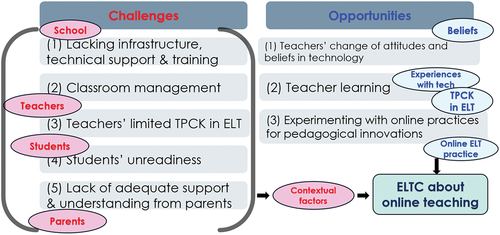

The data analysis yielded five important final themes answering the research question regarding the challenges ESL teachers faced in online teaching during COVID-19 and three significant final themes regarding the opportunities they simultaneously obtained. These themes, discussed below, contributed to understanding the three teachers’ cognition about online teaching.

Challenges

The five themes regarding the challenges were ‘lacking infrastructure, technical support and training’, ‘classroom management, “teachers” limited TPCK’, ‘students’ unreadiness’ and ‘lack of adequate support and understanding from parents’.

Lacking infrastructure, technical support and training

It was found that the incompatible technological facilities and the lack of technical support and training in technology integration before the school closure hindered the implementation of online teaching and led to further challenges.

Jane encountered many technical problems while teaching online, stating that, ‘I was unable to conduct lessons interactively. On Meet, there were various technical problems lessons. For example, I could not hear my students and vice versa.’ (personal communication, 28 November 2020, p. 7). She added, ‘There was inadequate and insufficient training before and during the school closure’ (personal communication, 28 November 2020, p. 7). She expressed, ‘Suddenly, we had to use Meet to teach online. It took a lot of time to learn and get used to it. Therefore, most of us simply used PowerPoint as the main tool to give one-way lectures to students’ (personal communication, 28 November 2020, p. 11). Jane’s narrative reveals that a lack of online teaching training impacted teachers’ initial lesson planning and detrimentally affected teaching quality. This is because online teaching involves different pedagogical knowledge and skills in general.

In the interview, Jane used the terms ‘helpless’ (personal communication, 28 November 2020, p. 3) and ‘negative’ (personal communication, 28 November 2020, p. 11) to describe her feelings and experience of online teaching. Like many other teachers, she was left to manage the unfamiliar online teaching environment and felt tremendous stress.

Fred’s school was only equipped with minimal technological facilities. ‘Our school is a traditional private primary school. We encountered many challenges initially when we implemented online teaching as we lacked basic facilities and training. Also, we didn’t have many e-learning elements in teaching’ (Fred, 17 December 2020, p. 1). Lacking infrastructure, technical support and training, the school spent over six months strengthening its Wi-Fi access points, purchasing tablets for teachers’ use, digitalising the school homework system and providing basic training for its staff before synchronous online teaching could be implemented. ‘We don’t have teaching assistants or technicians’, Fred (personal communication, 17 December 2020, p. 4) pointed out. He shouldered the responsibilities of training and supported his panel members in making video lessons and uploading them online for students’ self-learning. Simultaneously, he and his colleagues needed to solve different technical problems to prepare synchronous online instruction with teachers’ real-time guidance and support.

Kenny and the other senior teachers led the staff in an unusual teaching experience. Although his school was more advanced in terms of e-learning implementation, he still felt the pressure due to inadequate training in online teaching. Kenny used the word ‘alone’ (personal communication, 11 December 2020, p. 7) and ‘helpless’ (personal communication, 11 December 2020, p. 7) to express his initial feelings about the pandemic and ‘frustrated’ (personal communication, 11 December 2020, p. 7) to describe his experience of tackling the challenges at the beginning of the school closure because ‘no one knew what to do!’ (personal communication, 11 December 2020, p. 7). Kenny further explained that they ‘were not taught online teaching before’ (personal communication, 11 December 2020, p. 7) and ‘had not been trained to teach online’ (personal communication, 11 December 2020, p. 7).

Overall, the three teachers encountered significant challenges in online teaching at the beginning of COVID-19. They all felt unprepared for the sudden switch to online teaching and struggled significantly throughout the process. The stress caused negative emotions in the teachers and affected their teaching quality.

Classroom management

Another challenge was how to manage a virtual classroom to sustain smooth teaching and learning. There were three aspects of classroom management that the teachers were committed to achieving but found challenging in an online environment: the classroom routines requested by the school administrative level, the virtual classroom discipline and real-time assessments of students’ learning during online lessons.

Jane found it time-consuming to perform roll calls in each online lesson and remind the students to switch on their cameras. In addition, the school’s rules and regulations of maintaining control and supervision in the same manner as physical classes increased her workload.

Moreover, all three teachers expressed great difficulties in supervising and assessing students’ learning processes. Jane expressed her concern over classroom management:

I feel negative because I cannot monitor my students’ learning process. … They might have just been gaming! They could not learn. That made me doubt the teaching effectiveness. I really feel ‘negative’ about that.

The change to the teaching and learning environment disrupted Jane’s usual control and supervision of her students’ learning. This sense of a loss of control frustrated her and eroded her teaching confidence.

Teachers’ limited TPCK in ELT

The findings revealed that Kenny possessed advanced knowledge and skills (TPCK) about technology integration in English language teaching. He was able to employ various digital tools to enhance students’ participation and promote collaboration in online lessons.

However, the findings indicated that Jane and Fred’s limited TPCK constrained their teaching effectiveness and confined the teaching and learning dynamic in the virtual classroom. For example, both Jane and Fred had limited technological knowledge (TK). They could only use PowerPoint, YouTube videos, and e-books for direct knowledge transmission in online teaching. Indeed, they primarily used low-level technology to directly substitute conventional teaching practices (Puentedura, Citation2006).

Besides, Jane and Fred could not incorporate other e-tools (e.g. Google Slides, Google Docs) or manage various functions (e.g. breakout rooms and the chatboxes) of the digital platform for online teaching to enhance collaboration, creativity and critical thinking, thus demonstrating their lack of TPK. In short, due to this lack, Jane and Fred were confined to one-way lecturing and unable to increase interaction in online teaching.

Students’ unreadiness

Both Jane and Kenny found that students were not ready to learn online because they lacked self-discipline, knowledge, and technology skills. In Fred’s situation, some students did not have adequate tools for online learning. However, Fred reported no important data on this theme, possibly because his school mainly implemented asynchronous online instruction within the research period.

In Jane’s case, she noticed that her students lacked technological knowledge and skills in using digital tools. When asked whether she had used any digital tools to design online lesson activities, Jane replied:

Rarely! Imagine that if we ask our students to log in to Nearpod, it will take ten minutes. Lower primary students will find it challenging to navigate the function buttons. They need someone around to support them. … Students’ limited information literacy limits online teaching and learning.

Jane’s responses indicated that her students’ weak technological knowledge and digital literacy affected online learning. The students’ unreadiness in using technology for learning discouraged Jane from designing technology-based learning tasks.

In Kenny’s situation, although his students were comparably more able to use technology in face-to-face learning, they were unfamiliar with virtual learning environments and became less motivated and self-disciplined. Kenny shared his observations:

As a panel head, I needed to observe other teachers’ classes. Sometimes, I found that the students’ responses were not desirable because, as I mentioned, there were lots of distractions at home. Teachers could not notice that their students were not paying attention. Then the students felt it was okay not to listen to their teachers.

Kenny’s remark reflected students’ unreadiness to take responsibility for their learning during online instruction. Their learning became more casual, and some students might instead have been surfing the Internet or gaming. As Kenny (personal communication, 11 December 2020) pointed out, teachers wasted significant amounts of time checking students’ attention to ensure they were learning.

Lack of adequate support and understanding from parents

Parents’ support during online lessons and their knowledge of online learning were crucial for teaching primary students online. The absence of these significantly hindered online learning. The support needed was suitable technical devices and adequate parents’ guidance on learning online.

For example, Fred (personal communication, 17 December 2020) noticed that some students from low socio-economic family backgrounds were often absent from his class because they did not have suitable digital tools for online learning. Besides, some students could not access the self-learning videos or print out assignments due to having neither Wi-Fi access nor printers at their homes.

Jane (personal communication, 28 November 2020) also reported that her younger students could not participate in digital games when their parents did not resolve any technical issues or provide guidance on her instructions. Therefore, she often resorted to using her students’ first language to provide explicit instructions to avoid misunderstandings. While some students lacked such support, some parents closely monitored the online lessons. Jane said, ‘Once I asked a student to answer my question, but I heard that my student was told how to answer the question by his parent. In fact, the student did not learn it (personal communication, 28 November 2020, p.11). She found the parent’s enthusiasm for helping her child give a correct response interfered with her teaching.

Kenny became upset by the parents’ misunderstanding of online teaching and learning and recalled that a parent had called him to ask why her daughter did not have paper-based assignments to complete after class (personal communication, 11 December 2020). Kenny found that many parents still held a conventional mindset about ESL teaching, believing that lecturing and drilling were the only ways to learn a language. The ideas of online learning and digital assignments were new to them. On one occasion, Kenny received a parent’s call asking him why her daughter played online games in lessons, querying whether she was learning English. Kenny explained:

When their children use Kahoot! on their iPads with the ‘doo doo’ sound, parents ask ‘why’. Are you playing? They don’t understand that their children are learning. They ask, ‘Why do you watch YouTube? Are you watching videos about gaming?’ … Adults often think narrowly. They feel that their children were playing with a computer most of the time but not learning. Parents are the primary resistance, and we spend lots of time explaining to them that children can learn online in a fun way. When students have online lessons, they are really learning, and they also need to observe specific rules.

Kenny compared ‘laying with a computer’ to ‘learning with a computer’ (personal communication, 11 December 2020, p.28) and contrasted two different gaming perspectives. His positive attitude towards the use of technology reflected a more modern mindset of how a language could be taught and learnt ‘in a fun way’ (personal communication, 11 December 2020, p.28). Nonetheless, the parents seemingly rejected this notion and revealed their sceptical thinking over online teaching. Kenny used the phrase ‘the main resistance’ (personal communication, 11 December 2020, p.28) to describe some parents who misunderstood online teaching and learning, showing that parents were key to successful online teaching.

Further explaining parents’ negative attitudes, Kenny (personal communication, 11 December 2020) pointed out that some parents were not serious about their children’s online learning and did not care whether they attended his lessons punctually. He speculated that parents’ misunderstanding of online teaching influenced students’ seriousness of learning online, causing lagged learning in the lessons.

Although the three participants faced many challenges in online teaching during COVID-19, they also gained valuable opportunities.

Opportunities obtained

The findings revealed three opportunities for ESL teachers due to the online teaching experiences during the pandemic. They were ‘teachers’ change of attitudes and beliefs in technology’, ‘teacher learning’ and ‘experimenting with online practices for authentic English use and collaborative learning.

Teachers’ changes of attitudes and beliefs in technology

During the pandemic, the urgent need to implement online teaching helped many teachers realise the importance of technology integration. Jane confessed that her original negative attitude changed after experiencing online teaching. Jane explained how online teaching and technology could assist her teaching:

I notice the advantages and flexibility offered by online teaching and technology. That is, you can communicate with students anytime and anywhere. You don’t have to teach in a classroom. For example, now [after the school closure], we have a half-day school. I can still use online teaching in the afternoon to supplement the morning teaching [in the afternoon] … I feel more positive about technology in teaching and online teaching now.

The online teaching experience prompted Jane to realise the affordances of technology in ESL teaching and offered her practical help to solve the problem of less teaching time during COVID-19.

Kenny witnessed the change in attitude of his colleagues towards technology during the pandemic:

At the beginning of the school closure, there was a ‘vacuum’ period between February and April when teachers got paid without working or paid to do very little. During that period, teachers had space to reflect on what current education needed. I never expected that several teachers would approach me to ask me how to conduct e-learning in a better way … I think the pandemic has led to lots of reflections from teachers. It has also given me many opportunities to reflect on how to use my lessons or whether what I teach is what my students need because I did not have the time to think before that.

Kenny pointed out that the ‘vacuum’ (personal communication, 11 December 2020, p.10) period in which the staff had less administrative work due to the sudden school closure provided a precious opportunity for reflection on their teaching practices. Such reflection is essential and significant for professional development in that it helps practitioners reconsider their practices in the ever-changing teaching contexts and enables them to examine pedagogic issues from another perspective.

Teacher learning

The findings showed that all three teachers’ TK, TPK and TPCK increased during online teaching. In addition, the analysis indicated that their learning was enhanced and promoted in various ways.

For Jane, her TK was greatly improved through learning in stand-alone in-house professional training workshops and self-learning through watching instructional YouTube videos. Nonetheless, her limited use of technology in online teaching indicates little growth in TPCK. Her learning only enabled her to survive online teaching during the pandemic.

For Fred, his TP and TPK increased by participating in a purposefully formed learning community (Pyhältö et al., Citation2015), receiving outsourcing and collaborative teaching (Farrell Buzbee Little, Citation2005). At the start of the pandemic, Fred’s school formed an IT team, of which Fred was one of the six members. The members discussed how to solve technical problems for online teaching and gave on-the-spot technical support to other teachers. Accordingly, while Fred supported his colleagues, he also learnt from the team, which served as a learning circle.

Fred also learnt from outsourcing. As the school closure prolonged, his school invited a start-up to develop a school-based digital homework system to deliver, collect and mark assignments. Fred and his IT team members first learnt the new tool from the start-up and then shared how to use it with the other teachers in in-house training workshops. Fred (personal communication, 17 December 2020) perceived that external support was indispensable in overcoming their challenges and enhancing efficient and constructive crisis-management collaboration to manage the crisis.

Moreover, Fred learnt through collaborative teaching with his panel members as they conducted online teaching. Fred and his colleagues were engaged in peer coaching activities to support one another throughout the process (explained in greater detail in the next section).

Kenny learnt from an outside school learning community (Pyhältö et al., Citation2015) via connectivity during the pandemic period:

Some people are good at IT outside my school and have innovative pedagogies. … So, these external professionals formed a learning group. It was formed voluntarily … we gathered together to discuss how to solve the problems as we had similar concerns and bring back some good practices to the school. There are many different teachers. They teach different subjects. Also, there are teachers from Apple Educators, teachers from Flipped Educators, and other teachers from Google Educators. These teachers have become my support. We once felt helpless but learnt to help one another in the learning community … After sharing ideas, I got more precise ideas about managing the situation.

In short, Kenny learnt through sharing ideas with different professionals who possessed diverse expertise and excellent TPCK. Though there was a social distancing barrier, his connectivity with external teaching communities was achieved via various means, such as instant messaging and video conferencing tools. The positive effects of this connectivity included providing emotional support to Kenny, offering him knowledge and skills of online technology integration in online and inspiring him with suitable strategies to tackle the emergent technical problems during the pandemic.

Experimenting with online practices for pedagogical innovations

The online teaching experience during COVID-19 provided space and opportunities for Jane and Kenny to experiment with technology in the authentic use of English and innovative pedagogical teaching practice both in and out of class. For them, the experiences of leveraging technology in their respective teaching practices had not previously occurred.

In Jane’s situation, although her original Situational Language Teaching was severely disrupted, she managed by resorting to direct instruction to teach, model and give guidelines explicitly to avoid misunderstandings and use her limited online teaching time economically. Jane (personal communication, 28 November 2020) expressed that teaching and learning then became less effective and authentic communication was largely constrained in the virtual classroom. However, Jane deftly remedied the situation by posting extra and useful instructions and announcements in English on Google Classroom after class to instruct and remind her students about their learning. ‘They would try to reply in English and make fun of it. I find that technology enables a space for them to use English in active and authentic ways’, (Jane, 28 November 2020, p.8). For example:

I left a message on Google Classroom to a student who had failed to hand in homework. Then the student wrote me a paragraph in English to explain why he could not hand it in and promised to hand in homework punctually. … Although my students’ language proficiency was not high, they used English to reply to me online since they were interested in technology. … They didn’t respond like that in a routine English classroom context.

Jane valued the authentic, communicative discourse supported by technology during online teaching as a strategy to promote English teaching and learning. She was impressed by her student’s appropriate online response in English, which showcased his communicative competence (Hymes, Citation1972) in using the language to negotiate a social transaction.

On the other hand, Fred was one of the key staff members who needed to seek and provide solutions to overcome the pandemic-based challenges. Working with a panel of teachers who were more experienced than him but had little TK, Fred experimented with collaborative teaching (Farrell Buzbee Little, Citation2005) with the other teachers and developed his own TPCK in ESL teaching.

Whenever we needed to upload a video lesson, we did the video recording together. So, for example, when my colleague was recording, I would be around to control the audio function and share the screen with various files.

In the early stages of the pandemic, Fred’s school executed an asynchronous online teaching approach by uploading YouTube video lessons for students to self-learn. Those videos mirrored a typical, face-to-face lesson. The entire process, from planning a lesson to creating a lesson video, was conducted collaboratively by two same-level teachers, demonstrating the evolution of a supportive and complementary culture in the panel. Moreover, peer coaching (Parker et al., Citation2008) was developed, with Fred having more TK to coach the other colleagues to resolve technological and pedagogical problems in their contexts.

Later, a synchronous online teaching approach was adopted, after which educators taught online classes separately. Fred regained the autonomy to design his own lessons and explained how a typical online reading lesson of his was conducted in class,

Usually, when I taught a reading text, I would ask them to do some pre-tasks and other tasks from the textbook in their GE exercise books. I would also ask them to do some practice in the book when I expected them to internalise some grammar structures. I seldom used the PowerPoints from the publisher … I like to have pre-tasks, tasks and post-tasks in my teaching. In the pre-task, I pre-teach vocabulary to familiarise them with the useful words and concepts related to the reading topic before introducing the reading passage.

Fred highlighted the use of pre-, during- and post-tasks in his online reading lessons that reflected his cognition about advocating Task-based Language Teaching (TBLT) in practice. He provided the following example to illustrate how he implemented the during- and post-task stages in his online teaching:

I used the breakout room function to put students into groups of two to three. They discussed some reading comprehension questions after reading a passage. Afterwards, I led a whole class discussion to get their responses to the questions. I found that it was quite successful! I also entered each small breakout room to observe how well they did the task and found that they could arrive at some conclusions from discussions. It was seen that students learnt through interacting in discussions, rather than learning through a one-way knowledge transmission from the teacher.

Fred’s experimentation with new technology to enable him to actualise the practice of TBLT in an online environment could well be called a success. From his observations, the students engaged in active learning in the online environment to practise critical thinking skills and co-construct knowledge to draw conclusions from reading input. Moreover, he was also able to effectively leverage technology to sustain his usual pedagogies for teaching, unlike Jane, who encountered some unsolved hiccups that continuously disrupted her choice of pedagogies.

Finally, in Kenny’s situation, he spent the first two months of online teaching conducting two projects which had never previously been conducted online. ‘At first, I doubted if it could be done online. But I believed that it would pay off in the end’ (Kenny, 11 December 2020, p.15). Kenny picked one project by way of an example:

The whole class worked on the same Google Slides. As the students wrote the biography [of Martin Luther King], they all got the information … It was a research project … First, I designed six questions. I let the students group themselves freely into six groups. Each group chose one of the questions to research … Then, they searched online to find relevant information … I gave feedback on their slides … In the end, it was like a food party. They shared what they had found. My role was to conclude and generalise their ideas.

Instead of resorting to Jane’s method of direct knowledge transmission, or mirroring Fred’s usual face-to-face teaching practice in an online environment, Kenny took a risk to experiment with a project-based approach (Dewey, Citation1938) in an online learning environment to promote ‘students’ autonomy, constructive investigations, goal setting, collaboration, communication and reflection within real-world practices’ (Kokotsaki et al., Citation2016, p. 267).

He also advocated learning through doing, collaborating, and co-constructing knowledge in his teaching. For example, Kenny used ‘a food party’ (personal communication, 11 December 2020, p.17) as an analogy to indicate how he upheld collective intelligence in teaching and learning and celebrated his students’ learning achievements.

Kenny’s teaching practice reflected a combination of the TBLT and Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) pedagogies, with a clear learning task for students to research a celebrity in order to understand some significant historical events. In leveraging technology to support teaching and learning, Kenny gained precious hands-on online teaching experience and vastly improved his TPCK through exploring new teaching methods.

As a whole, facing the new mode of teaching, the three teachers’ choices of pedagogies were influenced to some extent according to their respective contexts. Jane and Fred circumvented the obstacles and explored different means to sustain teaching and learning. As to Kenny, he chose to take risks to experiment with new learning experiences. Moreover, their approaches can be concluded as being blended in various ways. For example, the curriculum and instruction were available online from an asynchronous to synchronous format at different timelines. Students learnt in both live and online lessons and underwent digital learning experiences with self-learning materials, research work and collaborative work after formal online lessons.

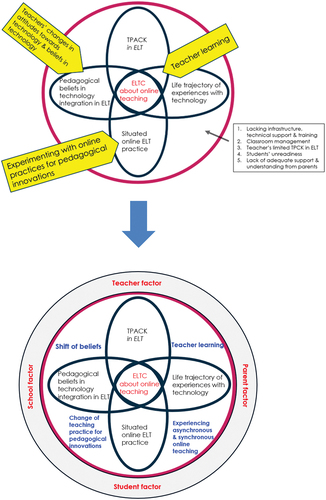

After the explication of the themes about the challenges and opportunities the three teachers encountered, the themes were further synthesised to reveal the complexity of English language teachers’ cognition about online teaching.

The complexity of ELTC about online teaching

The themes () holistically contributed to the understanding of the three teachers’ cognition about online teaching in the context of COVID-19. The findings show that the contextual factors (i.e. the challenges of online teaching), were exerted by various stakeholders, including the schools, the participating teachers, the students, and parents. They caused tremendous stress and pressure on the teachers throughout the implementation of online teaching. Nonetheless, the crisis also became the catalyst for the teachers’ shift of pedagogical beliefs, the improvement of the teachers’ TK, TPK and TPCK, and the development of their pedagogical and technological innovation in teaching (Moorhouse & Wong, Citation2021). The findings show that the teachers perceived online teaching as both a challenge to manage and an unexpected opportunity to enhance their knowledge and skills in teaching.

Figure 2. The relationship between the themes about challenges and opportunities of online teaching and teacher cognition.

With the understanding of the cognition of the three teachers’ online teaching situations, an enhanced framework () prompted the conclusion of how various factors influence the formation of ELTC about online teaching.

Discussion and implication

The current study concludes with an enhanced theoretical framework that contributes to the understanding of ESL teachers’ cognition about online teaching.

In the same context of Hong Kong, Bai and Lo’s (Citation2018) survey study likewise found that technological resources, technical support, professional training, teachers’ knowledge and skills and students’ unreadiness were significant barriers to technology integration in primary school English education. Both these findings and those of the current study indicate that the implementation and execution of ESL e-learning and online teaching have encountered similar challenges. This could imply that a school that had already implemented e-learning before the pandemic outbreak would have been more ready to execute online teaching. Indeed, implementing e-learning successfully requires well-planned preparation of installing infrastructure, purchasing hardware and software, and professional training (Assareh & Bidokht, Citation2011). These also form the basics of online instruction. This inference is supported by the findings of the current study, whereby the three schools began to implement synchronous online teaching during the pandemic at different times due to the differences in the availability of equipment and teachers’ technological abilities.

Although the Hong Kong government has already introduced four Five-Year Strategies on IT in education since 1997 (Education Bureau, Citation2015), some schools, like those of Jane and Fred, were not yet equipped with adequate facilities and tools for e-learning and online teaching. Furthermore, the earlier e-learning initiatives in general could not elevate English language teachers’ TPCK. The findings of this study, reflecting the teachers’ unreadiness of teaching online or managing virtual classrooms during the pandemic, align with those of Moorhouse’s (Citation2021) findings. Worse still, due to the unreadiness of adopting online teaching during the pandemic, teachers were placed under tremendous stress to determine how best to manage the novel situation (MacIntyre et al., Citation2020). Consequently, as reported by both Jane and Kenny, teachers’ well-being was hampered and their negative emotions increased.

Therefore, in order to effectively manage teaching and learning in the short term during similar, possible crises in future, the government should implement immediate remedial measures to support schools, teachers, and students. For example, advisors may be sent to schools to improve online learning. Online professional workshops should be provided quickly for teachers to bolster their online teaching capacity. Urgent funds need to be offered to support economically disadvantaged families in purchasing necessary online learning devices. In the long term, the government should evaluate the effectiveness of IT in education strategies to ensure that school funding for the promotion of e-learning has been well spent. It is also essential for the government to supervise, review and follow up on the progress of e-learning development in all schools, including public and private ones and those that receive subsidies from the government, to ensure quality online teaching and learning for future unpredictable situations.

For teacher education, ICT courses related to language teaching should be embedded (Park & Son, Citation2020). Besides, pedagogies and curricular designs related to technology integration in ESL teaching in face-to-face, online and hybrid teaching should also be highlighted (Starkey, Citation2020). Furthermore, both pre- and in-service ESL teachers should be given opportunities to explore the possibilities and affordances of hybrid learning in schools to prepare for any necessary or unplanned changes in teaching modes.

Schools need to provide immediate technical support for online learning to students from lower socioeconomic status families to narrow the gap in learning opportunities during emergent situations, such as a pandemic, to reduce inequality in education. In addition, adopting a school-wide approach, they need to refine the curriculum to boost students’ digital literacy and technological knowledge and skills for e-learning. Schools should also promote parent education to help parents understand the importance of technology in ESL learning and explain how parents can support their children’s education through technology.

For ESL teachers, ‘technological proficiency’ and ‘pedagogical compatibility’ (Moorhouse, Citation2021, p. 9) are crucial for online teaching, meaning that it is essential to develop their TPCK. Apart from self-learning various technologies, ESL teachers are recommended to attend related seminars. Moreover, collaborative teaching can be an effective strategy to help ESL teachers develop essential knowledge and skills in online teaching (Chong & Kong, Citation2012). They are also advised to participate in learning communities (Stoll, Citation2010) with heterogeneous professionals to exchange ideas about using technology to facilitate ESL teaching and learning in different school contexts.

Conclusion

In conclusion, many ESL teachers encountered unprecedented teaching experiences when instruction was switched to an online format during the outbreak of COVID-19. This study sought to understand the different online teaching experiences of three Hong Kong ESL teachers in the context of the pandemic. The findings indicated that while the teachers faced immense challenges in implementing online teaching, they also found opportunities to advance their professional competence in using technology.

The understanding of the challenges and opportunities of the three primary ESL teachers’ online instruction experiences during the pandemic revealed implications for the government, teacher education, ESL teachers and schools. However, the study’s limited sample size of three teacher cases restricts the generalisability of findings and the diversity of perspectives. Therefore, when interpreting the study’s results, it should be acknowledged that its transferability was limited. Further research could examine how online teaching impacts ESL teachers’ choices of pedagogies and their teaching effectiveness, as well as primary students’ ESL learning regarding different familial and technical support.

Ethical statement

The Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) of the Education University of Hong Kong

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Angeli, C., Valanides, N., & Christodoulou, A. (2016). Theoretical considerations of technological pedagogical content knowledge. In M. C. Herring, M. J. Koehler, & P. Mishra (Eds.), Handbook of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) for educators 2nd edition (pp. 11–32). Routledge.

- Asik, A. (2016). Digital storytelling and its tools for language teaching: Perceptions and reflections of pre-service teachers. International Journal of Computer-Assisted Language Learning and Teaching, 6(1), 55–68. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJCALLT.2016010104

- Assareh, A., & Bidokht, M. H. (2011). Barriers to e-teaching and e-learning. Procedia Computer Science, 3, 791–795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2010.12.129

- Bai, B., & Lo, C. K. (2018). The barriers of technology integration in Hong Kong primary school English education: Preliminary findings and recommendations for future practices. International Journal of Languages, Literature and Linguistics, 4(4), 290–297. https://doi.org/10.18178/IJLLL.2018.4.4.189

- Birbili, M. (2000). Translating from one language to another. Social Research Update, 31(1), 1–7.

- Borg, S. (2006). Teacher cognition and language education: Research and practice. Continuum.

- Chong, W. H., & Kong, C. A. (2012). Teacher collaborative learning and teacher self-efficacy: The case of lesson study. The Journal of Experimental Education, 80(3), 263–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2011.596854

- Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (1987). Teachers’ personal knowledge: What counts as ‘personal’ in studies of the personal. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 19(6), 487–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022027870190602

- Clark, C. M. (1986). Ten Years of conceptual development in research on teacher thinking. Advances of Research on Teacher Thinking, 7–20.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Strategies for qualitative data analysis. In J. Corbin & A. Strauss (eds.), Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed., pp. 65–86). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452230153

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (Fourth ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Curriculum Development Institute. (2017). English language education: Key learning area curriculum guide (primary 1 – secondary 6). Education Bureau. https://www.edb.gov.hk/attachment/en/curriculum-development/kla/eng-edu/Curriculum%20Document/ELE%20KLACG_2017.pdf

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Simon and Schuster.

- Education and Manpower Bureau. (1998). Information technology for learning in a new era: Five-year strategy – 1998/99 to 2002/03.

- Education and Manpower Bureau. (2004). Empowering learning and teaching with information technology.

- Education Bureau. (2008). The third strategy on information technology in education: Right technology at the right time for the right task.

- Education Bureau. (2015). Report on the fourth strategy on information technology in education: Realising it potential, unleashing learning power – a holistic approach.

- Education Bureau. (2020). 運用電子學習平台及翻轉教室策略支援學生在家持續學習. https://www.edb.gov.hk/tc/edu-system/primary-secondary/applicable-to-primary-secondary/it-in-edu/flipped.html

- Education Bureau, The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. (n.d). Language Education Policy. https://www.edb.gov.hk/en/curriculum-development/major-level-of-edu/preprimary-sec/languages/lep/index.html

- Elbaz, F. (1981). The teacher’s “practical knowledge”: Report of a case study. Curriculum Inquiry, 11(1), 43–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.1981.11075237

- Farrell Buzbee Little, P. (2005). Peer coaching as a support to collaborative teaching. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 13(1), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611260500040351

- Hamilton, L., & Corbett-Whittier, C. (2013). Using case study in education research. SAGE.

- Hatch, J. A. (2002). Doing qualitative research in education settings. State University of New York Press.

- Hymes, D. (1972). On communicative competence. In J. B. Pride & J. Holmes (Eds.), Sociolinguistics (pp. 269–293). Penguin.

- Jackson, P. W. (1968). Life in classrooms. Teachers College Press.

- Kagan, D. M. (1990). Ways of evaluating teacher cognition: Inferences concerning the Goldilocks Principle. Review of Education Research, 60(3), 419–469. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543060003419

- Kamberelis, G., & Dimitriadis, G. (2005). Qualitative inquiry: Approaches to language and literacy research. Teachers College Press.

- Koehler, M., & Mishra, P. (2008). Introducing TPCK. AACTE Committee on Innovation and Technology. Ed, Handbook of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK) for educators (pp. 3–30). American Association of Colleges of Teacher Education and Routledge.

- Kokotsaki, D., Menzies, V., & Wiggins, A. (2016). Project-based learning: A review of the literature. Improving Schools, 19(3), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480216659733

- Kounin, J. S. (1970). Discipline and group management in classrooms. Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Pergamon.

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2015). InterViews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications.

- Long, M. (1996). The role of the linguistic environment in second language acquisition. In W. Ritchie & T. Bhatia (Eds.), Handbook of language acquisition. Academic Press.

- Lopez, G. I., Figueroa, M., Connor, S. E., & Maliski, S. L. (2008). Translation barriers in conducting qualitative research with Spanish speakers. Qualitative Health Research, 18(12), 1729–1737. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732308325857

- MacIntyre, P. D., Gregersen, T., & Mercer, S. (2020). Language teachers’ coping strategies during the covid-19 conversion to online teaching: Correlations with stress, well-being and negative emotions. System, 94, 102352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102352

- Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00684.x

- Moorhouse, B. L. (2021). Beginning teaching during COVID-19: Newly qualified Hong Kong teachers’ preparedness for online teaching. Educational Studies, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2021.1964939

- Moorhouse, B. L., & Wong, K. M. (2021). Blending asynchronous and synchronous digital technologies and instructional approaches to facilitate remote learning. Journal of Computers in Education, 9(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-021-00195-8

- Mouza, C. (2016). Developing and assessing TPACK among pre-service teachers: A synthesis of research. In M. C. Herring, M. J. Koehler, & P. Mishra (Eds.), Handbook of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) for educators (2nd ed., pp. 179–200). Routledge.

- Niess, M. L. (2012). Teacher knowledge for teaching with technology: A TPACK lens. In R. N. Ronau, C. R. Rakes, & M. L. Niess (Eds.), Educational technology, Teacher knowledge, and classroom impact: A research handbook on frameworks and approaches (pp. 1–15). Information Science Reference.

- Pamuk, S. (2012). Understanding pre-service teachers’ technology use through TPACK framework. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 28(5), 425–439. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2011.00447.x

- Paneru, D. R. (2018). Information communication technologies in teaching English as a foreign language: Analysing EFL teachers’ TPACK in Czech elementary schools. CEPS Journal, 8(3), 141–163. https://doi.org/10.26529/cepsj.499

- Parker, P., Hall, D. T., & Kram, K. E. (2008). Peer coaching: A relational process for accelerating career learning. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 7(4), 487–503. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2008.35882189

- Park, M., & Son, J. B. (2020). Pre-service EFL teachers’ readiness in computer-assisted language learning and teaching. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 42(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2020.1815649

- Puentedura, R. (2006). Transformation, technology, and education in the state of Maine [Web Log Post]. Retrieved from http://hippasus.com/resources/tte/