ABSTRACT

Urban research is becoming more representative of multifaceted urban conditions, but even a more inclusive urban lens often gravitates towards the metropolis. In this paper, I introduce metropolitan bias as the excessive concentration of people, economic activity, resources, and knowledge production in and on an urban system’s largest city. I illustrate the dynamics of metropolitan bias in the evolution of the Angolan system of cities and call for a perspective that recognizes the variegated political implications of metropolitan dominance for smaller cities. To this end, I highlight three entry points for future research: economic development, climate change, and governance.

Introduction

Urban studies as a discipline is founded on the intellectual prioritization of a specific space, the urban. Globally, this space presents itself in great variety, and the field is, consequently, in constant debate about its empirical scope and the distinction between the universal and the particular in its object of inquiry (Robinson, Citation2016; Robinson & Roy, Citation2016; Scott, Citation2022; Storper & Scott, Citation2016). This is a necessary and beneficial self-reflection and one that, in recent years, has been enriched by a novel array of voices. Post-colonial, feminist, and post-structural accounts have sought to call into question many of the discipline’s tenets derived from cities such as Chicago and Los Angeles (Parnell & Oldfield, Citation2017). And while the consequences of these developments for urban theory are controversial, the minimum consensus is that for research to arrive at meaningful conclusions and valuable policy advice, it must consider the full range of global urban conditions.

As a result, the urban lens has become more inclusive and ventured further south, but it has also continued to gravitate mostly towards the largest and most prominent of cities – the metropolises. Even though urban research has not been oblivious to city size (a mainstay of many academic and policy debates), its reflections frequently suffer from two shortcomings. First, studies that problematize the dominance of large cities do not necessarily share a common frame of reference. With little engagement between the different bodies of work, research is, for instance, concerned with the cost–benefit calculations around ‘optimal city size’, the relationship between primacy and growth, or elites that channel money to the national capital. A shared conception of metropolitan bias could create synergies between these often disconnected discussions. Second, empirical research on excessive concentration predominantly takes the form of econometric assessments analysing the effects of urban concentration on agglomeration economies, growth, or other macro-level indicators. This literature holds that real costs are incurred through spatial imbalances, but urban research has seldom gone on to examine the political or social specificities of the concerned systems. This is particularly puzzling considering that unease with a ‘large city bias’ has reached the highest levels in international urban development (UN-Habitat, Citation2022c, p. 116). For this reason, I attempt to provide an impetus towards a more encompassing research agenda in this paper.

The following sections make three contributions. First, I will draw on different writings on large city dominance to conceptualize metropolitan bias and introduce its main forms: structural, political, and research bias. Addressing the second shortcoming outlined above, I will then turn to the Angolan system of cities, an extreme case of metropolitan bias. I will first trace the evolution of metropolitan bias in Angola and, after that, outline a research agenda with concrete entry points for future assessments of biased urban systems. I thereby hope to counteract a singular focus on primacy and growth.

Metropolitan bias

Metropolitan bias is the excessive concentration of people, economic activity, resources, and knowledge production in and on an urban system’s largest city to the detriment of secondary or smaller cities. Research has approached bias towards the largest cities with different emphases. While many are concerned with the relationship between urban concentration and economic growth (Bertinelli & Strobl, Citation2007; Castells-Quintana & Wenban-Smith, Citation2020; Frick & Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018), others have focused on resource availability and inequalities across the urban hierarchy (Christiaensen & Kanbur, Citation2017; Ferré et al., Citation2012), or on the political-economy determinants of metropolitan dominance (Ades & Glaeser, Citation1995; Chen et al., Citation2017). Although united in their interest in imbalanced urban systems in one way or another, the lack of a shared concept can complicate a clear understanding of metropolitan bias and obfuscates the interconnection between its separate dimensions. Synthesizing the literature, I suggest understanding metropolitan bias as the interconnected whole of three main forms: structural, political, and research bias. Although deeply intertwined, each bias poses distinct questions and demands distinct approaches in research and practice. At the same time, an improved grasp of how the different forms of metropolitan bias interact can afford a more complete picture of urban dynamics and facilitate thinking across the separate debates.

Structural metropolitan bias is the outsized concentration of people and economic activity in one city of the urban system. In urban economics and economic geography, studying imbalances in the structure of urban systems is a well-trotted path whose themes are, among others, urban primacy, agglomeration (dis-) economies, or city size distributions as described by Zipf’s law. In its ‘rank-size rule’ formulation, the latter holds that the population of the nth largest city equals 1/n times the largest city’s population (Gabaix, Citation1999). Urban primacy can then be defined as a deviation at the top end of the urban system (usually within a country), by definition of a threshold for the largest city’s share of the total urban population or, in a classic expression, as the existence of a dominant city unrivalled in ‘magnitude and significance’ (Jefferson, Citation1939, p. 226). The reason why excessive concentration of this kind matters has to do with the contingency of agglomeration economies, the productivity increases through sharing, matching, and learning usually associated with dense urban settings (Duranton & Puga, Citation2004). In particular, the fast-paced rise of megacities in developing countries amid ‘urbanization without growth’ (Fay & Opal, Citation2000; Fox & Goodfellow, Citation2022; Glaeser, Citation2014; Jedwab & Vollrath, Citation2015) has turned scholarly attention towards the ‘discontents’ (Glaeser, Citation2020) of urbanization, or agglomeration diseconomies, such as congestion, pollution, or elevated housing prices. The evidence indicates that neither the desirable nor the less-desirable features of large cities depend on size alone but are rather a function of investments in infrastructure, sound governance, and a variety of other factors (Castells-Quintana, Citation2017; Frick & Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2016; Glaeser & Henderson, Citation2017). Still, size remains a shaping factor for many urban dynamics (Bettencourt, Citation2013; Bettencourt et al., Citation2007), and one may expect systems with a structural inclination towards their dominant city to be particularly prone to the liabilities that come with size. Hence, structural metropolitan bias demands a detailed understanding of such systems’ properties and their implications for policy intervention.

Political metropolitan bias is the overallocation of resources to the dominant city of the urban system. This is reminiscent of many 1980s debates that revolved around so-called urban bias. At the time, Michael Lipton famously argued that developmental efforts were biased towards cities and thereby disadvantaged rural populations and inhibited agricultural development (Lipton, Citation1977). This bias was, as he claimed, partly a result of the distortion of public spending orchestrated by well-organized urban elites. Today, an understanding of cities as ‘engines of growth’ (Collier et al., Citation2020) prevails, and discussions of Lipton’s urban bias have mostly subsided (Jones & Corbridge, Citation2010). However, the argument of those criticizing a political metropolitan bias follows a similar reasoning. The United Nations, for instance, cautions against ‘big-city bias’ and developments towards a ‘winner takes-all urbanism’ that ignores secondary cities and deprives them of essential resources (UN-Habitat, Citation2022c, p. 116). Even though hard evidence is challenging to obtain, many researchers are outspoken about central government neglect of this kind or political favouritism towards the metropolis (Rodríguez-Pose & Griffiths, Citation2021). Similarly, case evidence on the political economy of secondary cities highlights their struggle for policy attention, resources, and investments amid spatial inequality (Ammann et al., Citation2022). While a definite answer as to whether this kind of bias operates in a given case requires the fine-grained analysis of institutional relationships and resource allocation, political metropolitan bias is undoubtedly a widespread concern.

The third form of metropolitan bias is the disproportionate concentration of knowledge production and research on the metropolis. Early critics, Bell and Jayne, articulate this tendency in their observation that while ‘the urban world is not made up of a handful of global metropolises’ (Bell & Jayne, Citation2009, p. 683), our perspective is almost exclusively shaped by them. In recent years, this view has been echoed by many scholars who point to our precariously limited knowledge regarding the ‘missing middle’ (Christiaensen & Todo, Citation2014) of the urban system despite the vital role that is now more routinely ascribed to intermediary settlements (Satterthwaite, Citation2021). As appeals to shift our view to ‘overlooked cities’ (Ruszczyk et al., Citation2021) become more frequent, Kumar and Sternberg have given quantitative backing to many researchers’ long-standing impression (Kumar & Stenberg, Citation2022). Their findings of city size distribution in the most influential political science and urban studies journals corroborated (for these disciplines) the disproportionate attention paid to the largest cities. One can presume different factors to have precipitated this distorted representation of the urban world. Following an ‘urban turn’ (Parnell, Citation2016) in many disciplines, the early scholarly focus on ‘global cities’ (Sassen, Citation2005) has certainly shaped academia’s trajectory and made smaller and apparently less connected cities seem uninteresting. In addition, research follows incentive structures where studying a large city may hold the promise of addressing a wider scientific and political audience. And finally, place bias may have played a role as most universities are located in large cities and tend to prioritize their immediate environment (Grossmann & Mallach, Citation2021).

The reason why one should worry about the resulting bias is straightforward. Most urban dwellers do not live in the largest metropolises but in cities with less than one million inhabitants, a share projected at 54% for 2030 (United Nations, Citation2019). This would not be too concerning as long as one could confidently generalize findings from the metropolis to the larger urban system. Yet, there is ample evidence that this is not the case. Secondary cities are different regarding social composition, economic structure, resource availability, and processes of governance (Roberts, Citation2014). The academic community can, therefore, not afford to disregard smaller cities and the implications of their subordinate position relative to the metropolis.

In conclusion, a clear conception of what metropolitan bias entails can help to structure debates in research and practice as each form poses distinct questions and challenges. At the same time, their interconnection is just as important. The disproportionate growth of a dominant city may be the result, among other factors, just as well as the cause of political favouritism towards the metropolis. And academia is, for the reasons above, far from immune to replicating and furthering these imbalances. An undue focus of knowledge production on the dominant city precludes countervailing developments as it fails to support an environment conducive to alternatives and ultimately reproduces metropolitan bias. We must therefore start to see beyond the metropolis.

Angola and the virtues of extreme cases

While large-n assessments of urban concentration are legion, our understanding of metropolitan bias could benefit greatly from more comparative and case studies. It is for this reason that I want to outline the interplay of its different elements in the evolution of a neglected country case of metropolitan bias, the Angolan system of cities. But before doing so, I will briefly justify my case selection.

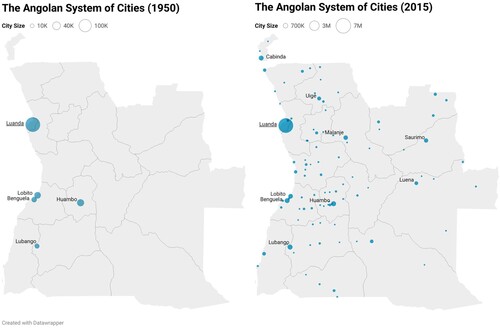

Angola has for decades been one of the fastest urbanizing countries in the world. Throughout its post-independence history after 1975, it experienced urban growth rates of more than 6% annually, well above the sub-Saharan average of 4,4% and the global average of 2,4% during the same period (). The United Nations estimates that Angola will reach a population of 72 million in 2050, more than 80% of which will live in the country’s cities (United Nations, Citation2019). But rapid urbanization is not the only reason why Angola merits greater scholarly attention. The Angolan system of cities also constitutes an outstanding example of metropolitan bias since Angola’s urban structure is firmly dominated by Luanda, political constellations at various points in its history have favoured the capital, and research attention is strongly centred on its metropolis.

Figure 1. Annual urban population growth in Angola, Sub-Saharan Africa, and the world. Author’s illustration. Data source: World Bank Development Indicators.

Looking at the quantifiable elements of Angola’s urban system today, its structural inclination towards Luanda is undeniable. UN estimates see Angola’s total urban population at roughly 22 million people, 8.3 million of which are thought to reside in Luanda, close to 40% of the total urban population (United Nations, Citation2019). Luanda is also ten times as large as the country’s second largest city, Lubango with about 830,000 inhabitants. This is clearly far from any regular rank-size distribution and also quite exceptional in international comparison.Footnote1 Luanda’s dominance is just as apparent in economic terms. Its province, according to data from the Angolan National Statistics Institute (INE), accounts for 51% of national non-farm employment (Instituto Nacional de Estatística, Citation2023). Moreover, 59% of all active companies are based in the province, including 80% of the extractive industry, a sector that still contributes a third of GDP and 96% of exports (Instituto Nacional de Estatística, Citation2019; International Monetary Fund, Citation2022).

Methodologically, the structural dominance of Luanda meets all the criteria to classify Angola as an ‘extreme case’ of urban primacy and holds the potential to generate insights of interest to wider urban scholarship (Seawright & Gerring, Citation2008). In this regard, Angola’s urban system may serve as a starting point for maximum variation comparisons or as a case study exploring the effects of extreme primacy on so far understudied elements of urban development (Seawright, Citation2016). Furthermore, focusing on an extreme case allows the researcher to make an argument in an, as Flyvbjerg argues, ‘especially dramatic way’ (Flyvbjerg, Citation2006, p. 229). The lack of scholarly attention beyond Luanda can, in this sense, serve as an ideal background to shed light on a neglected element of urban research and provide an impetus for more research on metropolitan dominance and its implications for the wider urban system.

In conclusion, Angola is an ideal case to broaden the established perspective on urban development as seen from the metropolis. The remainder of this paper now seeks to accomplish two things. First, I will trace the evolution of Angola’s urban system to show how metropolitan bias and its different elements evolved and interacted in this particularly salient case. And second, I will substantiate my appeal to see beyond the metropolis by outlining how this can be achieved in Angola.

Making the ‘Republic of Luanda' – a brief history of the Angolan system of cities

Observed from the outside, urban Angola has often been described in superlatives. Whereas post-slave trade Luanda was at times referred to as ‘the poorest city in the world’ (Amaral, Citation1978, p. 295), the concentration of oil wealth in post-war Angola earned its capital the dubious honour of being recognized as the ‘most expensive city in the world’ (Antunes, Citation2017). Classified here as an outstanding case of metropolitan bias, it is instructive to see how what has been called the ‘Republic of Luanda’ (de Oliveira, Citation2015, p. 20) evolved and what shaped its development.

Tracing this evolution also connects what follows to the literature on the determining factors of urban primacy. Many studies in this research strand have shown that urban systems do not always follow a clear path from high initial levels of primacy to a more balanced pattern over the course of their economic development. Instead, different economic, geographic, and political factors (total population, country size, degree of centralization, capital city status, coastal position, or the financial industry, among others) may intervene to shape the flow of people and economic activity (Castells-Quintana, Citation2017; Ioannou & Wójcik, Citation2021; Moomaw & Alwosabi, Citation2004). Meanwhile, case evidence, despite being crucial to a nuanced understanding of primacy dynamics, continues to be rare (Bo & Cheng, Citation2021; Wilkinson et al., Citation2022). It is therefore a worthwhile undertaking to briefly sketch the evolution of urban Angola.

In any discussion of Angola’s urban history, one should not tacitly assume the city’s arrival only with colonization. Larger urban settlements had existed before the Portuguese spread along Angola’s coast and eventually penetrated the hinterland. The former capital of the Kongo Kingdom, Mbanza Kongo, known during colonial times as São Salvador, is the best-documented case (Freund, Citation2007, pp. 8–9; Heywood, Citation2014). The royal seat was a city of considerable size when the Portuguese first arrived in 1483 and home to an estimated 60,000 people in 1548 (Heywood, Citation2014, p. 369). Notwithstanding patchy evidence, one may reasonably assume that Mbanza Kongo was not the only pre-colonial urban centre. For example, early visitors compared Cabaça, the capital of the Kingdom of Ndongo, to the Portuguese town of Évora as it reportedly consisted of 5,000–6,000 houses (Heintze, Citation1977, p. 792).

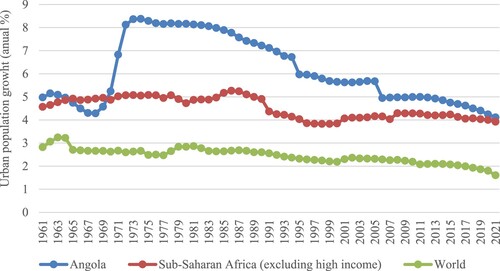

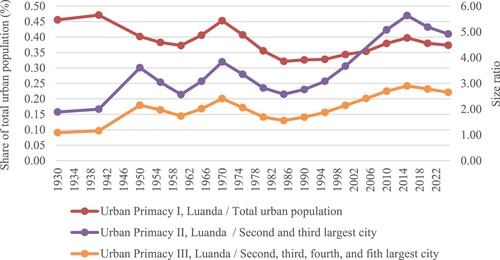

This said, there are three driving factors behind the evolution of Angola’s urban system and Luanda’s dominance: colonialism, war, and reconstruction. While highlighting all elements of metropolitan bias in the following discussion, I underpin the structural component by calculating Angolan urban primacy from 1930 to the present. I use United Nations estimates starting from 1950 in addition to estimates and census data for 1930 and 1940 given by Amaral (Citation1978) to calculate Luanda’s share of the total urban population as well as the size ratios between Luanda and the two as well as four next largest cities. The resulting tendencies are robust for each type of calculation (see ) and for different population estimates from either national sources or the OECD’s Africapolis project, which relies on a unified definition of urban areas (OECD & ECA, Citation2022).

Figure 2. Angolan urban primacy 1930–2022. Author’s illustration. Data source: United Nations (Citation2019) and Amaral (Citation1978).

Much of Angola’s urban system today is the fruit of its colonial past. Venturing further south, driven, among other motivations, by needed supply for the nascent slave trade, a Portuguese expedition arrived at the site of today’s Luanda in 1575 (Wheeler & Pélissier, Citation2016, pp. 66–69). Soon, the city came to be the ‘capital of the slave trade’ (Marques, Citation2004, p. 51). Home to as little as 5,600 people in 1844, the population of the fortified town fluctuated with the trans-Atlantic demand for enslaved labour (Curto & Gervais, Citation2001). Despite its relatively small population, and notwithstanding the foundation of the southern slaving port of Benguela in 1617, Luanda was the undisputed centre of colonial Angola, serving as administrative seat and main embarkation port for the all-dominating slave trade. With the end of the commerce in enslaved people, the city, unlike Benguela, quickly more than doubled its population as the colonial economy shifted to the more labour-intensive commerce in raw goods (Curto, Citation1999). Eventually, by the mid-nineteenth century, Luanda was, as a result of significant public works programmes, transformed from a ‘military encampment’ to a genuine ‘urban centre’ (Curto, Citation1999, p. 397). Only briefly was its standing ‘severely challenged’ (Tomás, Citation2022, p. 62) when the Portuguese contemplated the newly built city of Huambo, Nova Lisboa between 1928 and 1975, as a potential replacement. It was the construction of Luanda’s port and railway, the higher productivity in Angola’s north, and the only incipient growth of Huambo that ultimately secured Luanda’s position (Neto, Citation2012, p. 150; Tomás, Citation2022, pp. 65–70). In 1930, the capital with its 51,000 inhabitants accounted for 45% of Angola’s total urban population and was almost twice the size of Benguela and Huambo combined, with populations of 13,000 and 14,000 respectively. Looking at Angola’s urban development before the mid-nineteenth century, one can, of course, hardly speak of bias since no interconnected urban system existed. One may, however, conclude that its role as political centre and its centrality in the slave trade paved the way for its later dominance, while public investments based on the city’s integration into the international economy further strengthened and secured its singular position entering the twentieth century.

During the early years of António de Oliveira Salazar’s authoritarian ‘Estado Novo’, there was little interest in the colonies’ economic development (Tostões & Bontio, Citation2015). Angola’s cities grew slowly, and the overall composition of the urban system remained stable. This changed in the 1940s. On the one hand, the increased global demand for colonial goods created an economic boom in Angola, most noticeably in the coffee sector, Angola’s primary export product between 1946 and 1972 (Pacheco et al., Citation2018; Valério & Fontoura, Citation1994). On the other hand, the Portuguese government responded to international demands for decolonization by doubling down on colonial investments, planning activities, and support for white settler migration. This strategy is well encapsulated by the foundation of the ‘Gabinete de Urbanização Colonial’ (GUC) [Office for Colonial Urbanization] in 1944, which had a vital role in organizing the creation and expansion of colonial settlements (Milheiro, Citation2021a; Tostões & Bontio, Citation2015). Moreover, this was also the first period of extensive modern scientific knowledge production on urban Angola, and the GUC was an integral part of a general Portuguese effort to foster a scientific foundation for its colonial policies (Milheiro, Citation2021a). It was, as a result, not only Luanda that saw its first urban plan with the unrealized proposal of Étienne De Groër and David Moreira de Silva in 1943 but many settlements for which new plans were elaborated, the GUC being responsible for most of them until 1959 (Milheiro, Citation2012). With the deliberate intention to ‘intensificar uma ocupação planificado do território mais desconhecido’ [intensify a planned occupation of the least known territory] (Da Fonte, Citation2007, p. 169), these efforts counteracted Luanda’s structural dominance. Even though the capital retained a certain pre-eminence, for instance, with a first book-length treatment (Amaral, Citation1968), research and planning spanned the entire urban system. Simultaneously, Angola’s cities started undergoing unprecedented expansion. As the economy grew and white settlers flocked to the colony, Luanda’s population rose from 60,000 in 1940 to 220,000 in 1960. Yet, and in accordance with a series of national development plans (Silva, Citation2015), the economic boom was accompanied by investments in settlements and, importantly, infrastructure across the urban system (Milheiro, Citation2021b). As a result, smaller places, such as Uíge, the centre of the coffee plantations in Angola’s North, grew into towns, and larger railway-connected cities, such as Huambo or Lobito, with its prospering port, developed faster than the capital. For this reason, after 1950, all measures of primacy decline as Angola’s urban system increasingly curbed metropolitan dominance.

This development was interrupted by the onset of the colonial war in 1961. As the conflict intensified and external pressure further increased, the Portuguese government launched a military campaign. Although colonial migration only briefly plummeted that year and recovered strongly afterwards (Castelo, Citation2013), the data indicates a shift in settlement patterns. First, the white population became even more urban. Whereas 60% of those who the census classified as ‘white’ lived in Angola’s cities in 1960, this share had jumped to 77% in 1970 (Castelo, Citation2013). Second, Angola’s white population not only turned to the cities in general but especially to the capital. According to the population data for Angola’s main cities given by Castelo (Citation2007, p. 222), Luanda accounted for around 52% of the white urban population in 1960 and 64% in 1970. Of course, the white population rarely comprised more than 40% of the urban total, but general population movements closely followed colonial settlement patterns. As a result, the structural inclination towards Luanda reached a new high point in 1970. This is despite continued public investment and planning activities up until 1975 (Da Fonte Citation2007). As Cláudia Castelo remarks, it was during this time that a veritable exodus of the African population towards the cities took place, and Luanda’s informal settlements expanded significantly (Castelo, Citation2007, p. 112).

Following a military coup in Lisbon that overthrew the regime of Marcelo Caetano on the 25th of April 1974, Angola gained its independence in November of the following year. Decades of war and political instability ensued. Until the mid-1980s, the post-independence period coincides with a decline in Luanda’s structural dominance. While Angola continued to grow and urbanize rapidly, Luanda was affected by the departure of most of the 335,000 settlers who lived in the colony in 1974 (Pimenta, Citation2017). If we conservatively assume that the distribution of Angola’s white population remained roughly the same at independence as it was in 1970, more than 160,000 settlers would have left the city of Luanda, around a quarter of its total population at the time. Moreover, a number of secondary cities experienced comparatively rapid growth. Benguela, Lobito, Huambo, Lubango and Cabinda all more than doubled their population between 1975 and 1985 (United Nations, Citation2019).

The war years were characterized by armed conflict of varying intensity and fragile periods of peace. When insecurity spread through the Angolan countryside and infrastructure fell into disrepair or was destroyed, roughly four million Angolans were internally displaced (UNHCR, Citation2002). As they flew to the cities, it was most of all Luanda to once more assume the role of a ‘wartime safe space’ (Udelsmann Rodrigues, Citation2022a, p. 10), replicating earlier population dynamics. At the same time, the MPLA-government (‘Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola’) exercised control over ‘an archipelago of cities’ (de Oliveira, Citation2015, p. 117) but was unable to continue late colonial investments or planning activities as most resources were tied up by the continuous war effort (Soma, Citation2018, p. 133). As for the money that was available in a system progressively more centred on the presidency, it is not unreasonable to assume that, as Birmingham puts it, ‘the presidential bounty was predominantly spent in the capital’ (Birmingham, Citation2015, p. 114). Regarding knowledge production, one may contend that while some interest remained, for instance, in the historical evolution of Angola’s cities (e.g. Amaral, Citation1978; Torres, Citation1986), the war did not allow for much new research to emerge. In sum, the long years of war not only consumed lives and resources but also entrenched the structural and political dominance of the metropolis as the capital experienced an overwhelming population surge from 770,000 people in 1980 to almost three million in 2000. When Angola entered the new millennium, the capital’s growth outpaced the rest of the urban system despite the fact that its infrastructure was crumbling under the weight of its own growth.

After the war, Angola started to reconstruct a war-ravaged country. Its rebuilding was facilitated by abundant oil revenues and oil-backed loans from China that spared the government of Western-style conditionality (Power, Citation2012). Although reliable numbers are difficult to come by, large-scale investments were strongly concentrated in the metropolis as Luanda embarked on an ambitious pursuit of ‘world city’ status with a skyline of international-style high-rises and costly mega projects such as the redevelopment of the city’s bay area (Croese, Citation2018; Ovadia & Croese, Citation2016). The ‘oil-fuelled urbanization’ (Cain, Citation2017a, p. 483) of post-war Angola was, as Claudia Gastrow has argued, largely shaped by the presidency (Gastrow, Citation2020). Special offices were created to bypass the regular state administration as President dos Santos tightened his grip on urban development, and the list of projects directly or indirectly linked to the centre of political power grew ever longer. This prime example of political metropolitan bias exacerbated the country’s already pronounced regional asymmetries (Da Rocha, Citation2010; Dos Santos, Citation2011). Unsurprisingly then, Luanda’s structural dominance further increased, reaching a peak in 2011 with a population almost six times that of the two next largest cities. It was also during the time of post-war reconstruction that academic work on urban Angola surged. There are several reasons for this rise in scientific interest, among them a general ‘sub-national turn’ in scholarship, the sheer scale of urban transformation in Angola, and the fact that the country became gradually more accessible for research after the war. While the rich literature on urban Angola cannot in its entirety be recounted here, common and interconnected themes are, for example, the political economy of Luanda’s rapid transformation (Cardoso, Citation2022; Croese, Citation2016, Citation2018; Jorge & Viegas, Citation2021; Udelsmann Rodrigues, Citation2022a, Citation2022b), its unequal social implications (Cain, Citation2007; Tvedten et al., Citation2018; Udelsmann Rodrigues & Frias, Citation2016; Waldorff, Citation2016), or persistent issues related to land rights and housing provision (Cain, Citation2020; Croese, Citation2017; Dias, Citation2021). The inclination of this research towards Luanda is not absolute, and there is, for instance, insightful work on the Lobito corridor (Duarte & Santos, Citation2023; Schubert, Citation2023), Benguela (Roque, Citation2009), Huambo (Neto, Citation2012; UN-Habitat, Citation2013) or Uíge (Capitão, Citation2014). In general, however, knowledge production on urban Angola and especially its post-war development is mostly in line with the capital’s political and economic pre-eminence. It is for this reason that, as I will explore in more detail below, important questions relating to Angola’s wider urban system remain underexplored.

In this section, I have briefly shown how the structural, political, and research dimensions of metropolitan bias evolved throughout the history of Angola’s system of cities. Recent years have seen a slight decrease in primacy indicators in Angola, and political agendas have restated the ambition to promote a more spatially balanced system. With this in mind, it is the following section’s objective to outline how future research can contribute to more inclusive urban development by successfully seeing beyond the metropolis in Angola.

Three entry points to see beyond the metropolis

Angola is a suitable starting point to approach several topics that have been left neglected due to metropolitan bias in urban research. Substantiating this paper’s call to see beyond the metropolis, the following section provides an outline of how and where to overcome research bias in the Angolan context of economic development, climate change, and governance. While not meant as an exhaustive list, these are pertinent topics in urban studies that cover the established perspective on cities as growth engines, the more recent sub-national turn in climate action, and governance as a ubiquitous factor in all urban developments. All of these fields can only benefit from the inclusion of the non-metropolitan urban into their agendas.

Economic development

The conditions of ‘late urbanization’ (Fox & Goodfellow, Citation2022) in the Global South have provoked a discursive shift towards the discontents of the city. Still, as the promise of ‘urban growth engines’ continues to loom large, research has sought to understand how inhibiting factors to the city’s virtues can be overcome. Pointing to excessive concentration as one such factor, remedies highlighted by research usually include infrastructure investments, sound governance, and the promotion of secondary city development (Castells-Quintana, Citation2017; Henderson, Citation2002; Rodríguez-Pose & Griffiths, Citation2021). Additionally, the role of smaller cities as urban-rural linkages with a vital impact on poverty alleviation is well established (Agergaard et al., Citation2019; Christiaensen & Kanbur, Citation2017; Christiaensen & Todo, Citation2014).

A promising next step for research may be the study of urban policies as seen from a system of cities perspective. Focusing on smaller cities, Grossmann and Mallach, for instance, call for ‘research that identifies pathways to greater economic success’ (Grossmann & Mallach, Citation2021, p. 171). Yet, despite an apparent consensus regarding the policy potential to avert the negative repercussions of excessive concentration, few studies have gone on to empirically assess questions of policy in secondary cities or in the particular context of biased urban systems.

The Angolan system of cities is an intriguing case to approach these issues. Throughout the last century, the country has developed an extensive system of secondary cities (see ) and, soon after the war’s end, adopted a growth-pole agenda in its long-term development plan (República de Angola, Citation2007). The plan stipulates the development of different economic clusters across the country’s urban system with the ambition to mitigate the adverse effects of Luanda’s dominance. This strategy has been reiterated in the latest national development plan emphasizing the desire to support urban specialization for Angola’s centres beyond Luanda (República de Angola, Citation2018). And although Angola’s oil-dependent economy faces great challenges, its secondary cities hold significant economic potential. In a country where around 52% of all employment is in agriculture, the largest concentrations of highly qualified workforces and incipient industries outside the capital are found in the provinces of Angola’s growing secondary cities such as Benguela or Lubango (Instituto Nacional de Estatística, Citation2023). Recent investments and policy attention, for instance, regarding the Lobito transport corridor, underline this potential (Jornal de Angola, Citation2023). How the economic fortunes of Angola’s smaller cities and their promise to diversify the country’s economy are affected by the dominance of Luanda, what role long-standing policy efforts to promote growth poles play, and to what extent the metropolis shapes financial and economic policies, are then the type of questions worth asking.

Climate change

In climate action, cities are at the forefront of both mitigation and adaptation efforts (Angelo & Wachsmuth, Citation2020; Bartlett & Satterthwaite, Citation2016). Crucially, this must not be thought from a metropolitan perspective alone. As Adelina et al. have argued in a rare study focusing on the climate change experiences of secondary cities, these often-neglected places hold significant potential to save CO2 emissions and attenuate future repercussions (Adelina et al., Citation2020). This is because they are home to the majority of urban dwellers, and their growth, in particular in developing countries, will entail large-scale infrastructure built-up with potential lock-in effects for carbon-intensive structures (Creutzig et al., Citation2016). Moreover, we know that climate change adaptation is most challenging in resource-constrained places and, in these contexts, more likely to disadvantage vulnerable groups (Dodman et al., Citation2022; Ziervogel, Citation2021). One may expect these issues to be all the more pertinent in cities of biased urban systems. Yet, case studies on climate change in smaller urban settlements continue to be scarce (Pasquini, Citation2020). And it is not only the local case evidence that is missing but also a more systematic understanding of smaller cities in the wider agenda. As the UN-Habitat highlights, secondary cities often find themselves in a disadvantaged position to access funding for climate action (UN-Habitat, Citation2022a). A point in case, the European Investment Bank’s ‘African Sustainable Cities Initiative’ aspires to counter the tendency of donor climate funding to be primarily directed at the largest cities (UN-Habitat, Citation2022a, p. 46). Metropolitan bias of this kind further strains already scarce resources outside the metropolis and underlines a troublesome gap within the global architecture of climate governance.

The Angolan system of cities is symptomatic of the need to approach cities and climate change with more than a metropolitan lens. Even the most benign projections show that the country’s inland settlements will, in the future, suffer from more frequent droughts and extreme heat, while population centres along the coast will be affected by rising sea levels and high rainfall variability (Carvalho et al., Citation2017; Udelsmann Rodrigues, Citation2019). These risks are further aggravated for dwellers of low-lying settlements with poor infrastructure that are more prone to flooding (Cain, Citation2017b). As far as mitigation is concerned, Angola is faced with the task of considering the future of its fossil-fuel based economy (República de Angola, Citation2017). The country’s urban growth pole agenda, as mentioned above, is one of the building blocks of a desired diversification. And, given the climate sensitivity of many non-extractive sectors and the importance of fostering urban economies, this diversification is also tightly linked to successful climate adaptation (World Bank, Citation2022). Noticeably, Angola has passed a national climate change strategy, adopted national targets under the Paris Agreement, and is in the process of filling these goals with policy action (República de Angola, Citation2021). Further research in the Angolan context can provide valuable insights into the challenges that climate change and climate action pose for smaller cities in primacy systems, into how climate policy plays out in these settings, and it can ultimately improve evidence-based policymaking as the foundation for sustainable development in all cities amid a climate crisis.

Governance

Governance is the final entry point for future research to be highlighted here. Understood as the complex interactions between public and private actors at multiple levels, we know that urban governance is a crucial factor for a city’s development (Da Cruz et al., Citation2019). At the same time, challenges to the ‘successful’ governance of cities abound. For the African case, Smit highlights, for instance, fragmented and sometimes conflicting authorities as well as capacity gaps in the context of scarce resources (Smit, Citation2018).

Scholars of governance should be wary of metropolitan bias since there is good reason to believe that smaller cities’ social, political, and economic characteristics produce markedly different governance dynamics (Djurfeldt, Citation2021). Moreover, political metropolitan bias may circumscribe the ability of lower tiers of government to voice their concerns to their regional or national counterparts (UN-Habitat, Citation2022b). In this regard, it is just as important to consider multi-level interactions within a country as exchanges between secondary cities and international public and private actors. These topics are increasingly well explored for ‘global cities’ (Davidson et al., Citation2019; Hickmann, Citation2021) but have rarely been raised for secondary cities (for an exception on Kisumu, Kenya, see Croese et al., Citation2021), let alone in the context of metropolitan dominance.

In Angola, effective urban governance is, of course, essential for the country’s secondary cities. While Angola’s protracted process of political decentralization is yet to culminate in the establishment of elected local governments, deconcentration has, over the years, transferred several responsibilities to local governments (Dos Santos & Lopes, Citation2015). Yet, regional asymmetries appear to leave many municipalities bereft of the capacity to adequately fulfil their role in governance (Teixeira & Santin, Citation2019). To what extent and how metropolitan bias has driven this is an open question. Furthermore, Angola has moved to adopt several innovative governance arrangements that merit consideration amid the country’s particular urban conditions. The country has, for instance, been developing a National Urban Policy (NUP) (UN-Habitat, Citation2018), an instrument that has, in recent years, found vocal support on the international stage (OECD, UN-Habitat & United Nations., Citation2021; Schindler et al., Citation2018). Aspiring to promote a more balanced urban system in Angola, it is a pressing question how such instruments play out in a country so strongly inclined towards its metropolis. Another governance innovation, Angola introduced participatory budgeting, a much-regarded element of participatory governance (Cabannes & Lipietz, Citation2018), for improved citizen engagement and communal development in 2019 (Kituxi, Citation2023). While it has been praised as a promising step in the country’s democratic development (Esteves, Citation2023), its future certainly demands critical scrutiny amid the Angolan process of decentralization. Assessing how these variegated processes of governance function in cities that are less in the limelight of policy attention than Luanda could significantly improve our grasp of urban governance in primate city systems.

Conclusion

In this article, I have tried to make the case for and contribute to urban research that sees beyond the metropolis. To this end, I have made three contributions.

First, synthesizing often disconnected bodies of literature, I have introduced metropolitan bias as the excessive concentration of people, economic activity, resources, and knowledge production in and on an urban system’s largest city. In a second step, I have outlined the evolution of metropolitan bias in the Angolan system of cities and traced its development to the forces of colonialism, war, and reconstruction. And finally, I have sketched concrete entry points for future research and illustrated several open questions with recourse to Angola’s cities.

Metropolitan dominance is never the full story of any urban system. And yet, it is a factor pervasive enough to warrant a view beyond established patterns of research. While urban economics has highlighted the costs of excessive concentration, it is time to understand the full breadth of its impact. This includes a more detailed perspective, in addition to primacy and growth, on the developmental fortunes of secondary cities in structurally biased systems, a deeper understanding of political biases that may, nationally and internationally, distort resource allocation to the detriment of smaller cities, and a critical self-reflection on how to readjust the analytical lens to fully capture the non-metropolitan world. Ultimately, the different dimensions and effects of metropolitan bias are deeply intertwined, and successfully seeing beyond the metropolis can not only afford a more complete view of the city in all its variety but also lay the foundation for cities of all sizes to strive.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Daniel Tjarks

Daniel Tjarks is a PhD candidate in Development Studies at the University of Lisbon. His research interests include urban development, governance, and political economy.

Notes

1 Among countries with more than 10 million inhabitants, very few (e.g. Guatemala, Peru, or Haiti) have a larger gap between their two main cities (United Nations, Citation2019).

References

- Adelina, C., Johnson, O., Archer, D., & Opiyo, R. (2020). Governing sustainability in secondary cities of the Global South: SEI Report. Stockholm.

- Ades, A. F., & Glaeser, E. L. (1995). Trade and circuses: Explaining urban giants. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(1), 195–227. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118515

- Agergaard, J., Tacoli, C., Steel, G., & Ørtenblad, S. B. (2019). Revisiting rural–urban transformations and small town development in sub-Saharan Africa. The European Journal of Development Research, 31(1), 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-018-0182-z

- Amaral, I. (1968). Luanda: Estudo de geografia urbana.

- Amaral, I. (1978). Contribuição para o conhecimento do fenómeno de urbanização em Angola. Finisterra, 13(25). https://doi.org/10.18055/Finis2258

- Ammann, C., Sanogo, A., & Heer, B. (2022). Secondary cities in West Africa: Urbanity, power, and aspirations. Urban Forum, 33(4), 445–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-021-09449-1

- Angelo, H., & Wachsmuth, D. (2020). Why does everyone think cities can save the planet? Urban Studies, 57(11), 2201–2221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020919081

- Antunes, M. (2017, July 24). Luanda é a cidade mais cara do mundo. Expresso. Retrieved March 21, 2023, from, https://expresso.pt/internacional/2017-06-24-Luanda-e-a-cidade-mais-cara-do-mundo.

- Bartlett, S., & Satterthwaite, D. (Eds.). (2016). Cities on a finite planet: Towards transformative responses to climate change. Routledge.

- Bell, D., & Jayne, M. (2009). Small cities? Towards a research agenda. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 33(3), 683–699. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00886.x

- Bertinelli, L., & Strobl, E. (2007). Urbanisation, urban concentration and economic development. Urban Studies, 44(13), 2499–2510. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980701558442

- Bettencourt, L. M. A. (2013). The origins of scaling in cities. Science, 340(6139), 1438–1441. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1235823

- Bettencourt, L. M. A., Lobo, J., Helbing, D., Kühnert, C., & West, G. B. (2007). Growth, innovation, scaling, and the pace of life in cities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(17), 7301–7306. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0610172104

- Birmingham, D. (2015). A short history of modern Angola. Hurst & Company.

- Bo, S., & Cheng, C. (2021). Political hierarchy and urban primacy: Evidence from China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 49(4), 933–946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2021.05.001

- Cabannes, Y., & Lipietz, B. (2018). Revisiting the democratic promise of participatory budgeting in light of competing political, good governance and technocratic logics. Environment and Urbanization, 30(1), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247817746279

- Cain, A. (2007). Housing microfinance in post-conflict Angola. Overcoming socioeconomic exclusion through land tenure and access to credit. Environment and Urbanization, 19(2), 361–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247807082819

- Cain, A. (2017a). Alternatives to African commodity-backed urbanization: The case of China in Angola. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 33(3), 478–495. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grx037

- Cain, A. (2017b). Water resource management under a changing climate in Angola’s coastal settlements. International Institute for Environment and Development, Working Paper.

- Cain, A. (2020). Housing for whom? In N. Marrengane, & S. Croese (Eds.), Reframing the urban challenge in Africa (pp. 183–207). Routledge.

- Capitão, R. (2014). Planeamento Urbano e Inclusão Social: O Caso de Uíge. Mayamba.

- Cardoso, R. (2022). Seeing Luanda from Salvador: Lineaments of a Southern Atlantic Urbanism. Antipode, 54(3), 729–751. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12824

- Carvalho, S. C. P., Santos, F. D., & Pulquério, M. (2017). Climate change scenarios for Angola: An analysis of precipitation and temperature projections using four RCMs. International Journal of Climatology, 37(8), 3398–3412. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.4925

- Castells-Quintana, D. (2017). Malthus living in a slum: Urban concentration, infrastructure and economic growth. Journal of Urban Economics, 98, 158–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2016.02.003

- Castells-Quintana, D., & Wenban-Smith, H. (2020). Population dynamics, urbanisation without growth, and the rise of megacities. The Journal of Development Studies, 56(9), 1663–1682. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2019.1702160

- Castelo, C. (2007). Passagens para África: O Povoamento de Angola e Mocambique com Naturais da Metrópole. Edições Afrontamento.

- Castelo, C. (2013). Colonial migration to Angola and Mozambique: Constraints and illusions. In E. Morier-Genoud & M. Cahen (Eds.), Imperial migrations (pp. 107–128). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Chen, Y., Henderson, J. V., & Cai, W. (2017). Political favoritism in China’s capital markets and its effect on city sizes. Journal of Urban Economics, 98, 69–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2015.10.003

- Christiaensen, L., & Kanbur, R. (2017). Secondary towns and poverty reduction: Refocusing the urbanization agenda. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 9(1), 405–419. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-100516-053453

- Christiaensen, L., & Todo, Y. (2014). Poverty reduction during the rural–urban transformation – The role of the missing middle. World Development, 63, 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.10.002

- Collier, P., Jones, P., & Spijkerman, D. (2020). Cities as engines of growth: Evidence from a new global sample of cities. Journal of Applied Business and Economics, 22(2), 158–188. https://doi.org/10.33423/jabe.v22i2.2808

- Creutzig, F., Agoston, P., Minx, J. C., Canadell, J. G., Andrew, R. M., Le Quéré, C., Peters, G. P., Sharifi, A., Yamagata, Y., & Dhakal, S. (2016). Urban infrastructure choices structure climate solutions. Nature Climate Change, 6(12), 1054–1056. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3169

- Croese, S. (2016). Urban governance and turning African cities around: Luanda case study, Nairobi.

- Croese, S. (2017). State-led housing delivery as an instrument of developmental patrimonialism: The case of post-war Angola. African Affairs, 116(462), 80–100. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adw070

- Croese, S. (2018). Global urban policymaking in Africa: A view from Angola through the redevelopment of the Bay of Luanda. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 42(2), 198–209. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12591

- Croese, S., Oloko, M., Simon, D., & Valencia, S. C. (2021). Bringing the global to the local: The challenges of multi-level governance for global policy implementation in Africa. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 13(3), 435–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463138.2021.1958335

- Curto, J. C. (1999). The anatomy of a demographic explosion: Luanda, 1844–1850. The International Journal of African Historical Studies, 32(2/3), 381–405. https://doi.org/10.2307/220347

- Curto, J. C., & Gervais, R. R. (2001). The population history of Luanda during the Late Atlantic Slave Trade, 1781–1844. African Economic History, 29(29), 1–59. https://doi.org/10.2307/3601706

- Da Cruz, N. F., Rode, P., & McQuarrie, M. (2019). New urban governance: A review of current themes and future priorities. Journal of Urban Affairs, 41(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2018.1499416

- Da Fonte, M. M. A. (2007). Urbanismo e Arquitectura em Angola: de Norton de Matos à Revolução [PhD thesis]. Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, Lisbon.

- Da Rocha, M. J. A. (2010). Desigualdades e assimetrias regionais em Angola: Os factores de competitividade territorial, Luanda.

- Davidson, K., Coenen, L., Acuto, M., & Gleeson, B. (2019). Reconfiguring urban governance in an age of rising city networks: A research agenda. Urban Studies, 56(16), 3540–3555. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018816010

- de Oliveira, S. R. (2015). Magnificent and beggar land. Angola since the civil war. Hurst & Company.

- Dias, M. (2021). Centralized clientelism, real estate development and economic crisis: The case of postwar Luanda. African Geographical Review, 40(3), 309–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2021.1933555

- Djurfeldt, A. A. (2021). Theorising small-town urbanisation in sub-Saharan Africa: A multi-scalar approach. Town Planning Review, 92(6), 667–676. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2021.16

- Dodman, D., Hayward, B., Pelling, M., Castan Broto, V., Chow, W. T. L., Chu, E., Dawson, R., Khirfan, L., McPhearson, P., Prakash, A., Zheng, Y., & Ziervogel, G. (2022). Cities, settlements and Key infrastructure. In H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E. S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, & B. Rama (Eds.), Climate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press.

- Dos Santos, B. (2011). Descentralização e governação local em Angola: Os desafios em termos de cidadania e de concentração dos recursos na capital do país. In Y.-A. Fauré, & C. U. Rodrigues (Eds.), Descentralização e desenvolvimento local em Angola e Moçambique: Processos, terrenos e atores (pp. 200–212). Coimbra: Edições Almedina.

- Dos Santos, B., & Lopes, C. M. (Eds.). (2015). Dez anos de desconcentração e descentralização administrativas. Luanda.

- Duarte, A., & Santos, R. (2023). The rehabilitation of the Benguela Railway and the reactivation of the Lobito Corridor. In T. Zajontz, P. R. Carmody, M. Bagwandeen, & A. Leysens (Eds.), Africa's railway renaissance: The role and impact of China (pp. 222–241). Routledge.

- Duranton, G., & Puga, D. (2004). Micro-foundations of urban agglomeration economies. In J. V. Henderson & J.-F. Thisse (Eds.), Handbook of regional and urban economics: Cities and geography (pp. 2063–2117). Elsevier.

- Esteves, C. (2023, March 18). Yves Cabannes considera orçamento participativo um “programa raro no continente africano”. Jornal de Angola. Retrieved June 8, 2023, from, https://www.jornaldeangola.ao/ao/noticias/yves-cabannes-considera-orcamento-participativo-um-programa-raro-no-continente-africano/.

- Fay, M., & Opal, C. (2000). Urbanization without growth: A not so uncommon phenomenon. World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper.

- Ferré, C., Ferreira, F. H., & Lanjouw, P. (2012). Is there a metropolitan bias? The relationship between poverty and city size in a selection of developing countries. The World Bank Economic Review, 26(3), 351–382. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhs007

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363

- Fox, S., & Goodfellow, T. (2022). On the conditions of ‘late urbanisation’. Urban Studies, 59(10), 1959–1980. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980211032654

- Freund, B. (2007). The African city: A history. Cambridge University Press.

- Frick, S. A., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2016). Average city size and economic growth. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 9(2), 301–318. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsw013

- Frick, S. A., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2018). Change in urban concentration and economic growth. World Development, 105, 156–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.12.034

- Gabaix, X. (1999). Zipf’s law for cities: An explanation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(3), 739–767. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355399556133

- Gastrow, C. (2020). Urban states: The presidency and planning in Luanda, Angola. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 44(2), 366–383. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12854

- Glaeser, E., & Henderson, J. V. (2017). Urban economics for the developing world: An introduction. Journal of Urban Economics, 98, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2017.01.003

- Glaeser, E. L. (2014). A world of cities: The causes and consequences of urbanization in poorer countries. Journal of the European Economic Association, 12(5), 1154–1199. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeea.12100

- Glaeser, E. L. (2020). Urbanization and its discontents. Eastern Economic Journal, 46(2), 191–218. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41302-020-00167-3

- Grossmann, K., & Mallach, A. (2021). The small city in the urban system: Complex pathways of growth and decline. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 103(3), 169–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2021.1953280

- Heintze, B. (1977). Unbekanntes Angola: Der Staat Ndongo im 16. Jahrhundert. Anthropos, 72(5/6), 749–805.

- Henderson, V. (2002). Urban primacy, external costs, and quality of life. Resource and Energy Economics, 24(1-2), 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0928-7655(01)00052-5

- Heywood, L. (2014). Mbanza Kongo/São Salvador: Culture and the transformation of an African city, 1491 to 1670s. In E. Akyeampong, R. H. Bates, N. Nunn, & J. Robinson (Eds.), Africa’s development in historical perspective (pp. 366–390). Cambridge University Press.

- Hickmann, T. (2021). Locating cities and their governments in multi-level sustainability governance. Politics and Governance, 9(1), 211–220. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v9i1.3616

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística. (2019). Anuário Estatístico de Angola 2015–2018, Luanda.

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística. (2023). Inquérito ao Emprego em Angola: Relatório Anual 2021, Luanda.

- International Monetary Fund. (2022). Angola - Selected Issues, Washington, D.C.

- Ioannou, S., & Wójcik, D. (2021). Finance, globalization, and urban primacy. Economic Geography, 97(1), 34–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2020.1861935

- Jedwab, R., & Vollrath, D. (2015). Urbanization without growth in historical perspective. Explorations in Economic History, 58, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2015.09.002

- Jefferson, M. (1939). The law of the primate city. Geographical Review, 29(2), 226–232. https://doi.org/10.2307/209944

- Jones, G. A., & Corbridge, S. (2010). The continuing debate about urban bias. Progress in Development Studies, 10(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/146499340901000101

- Jorge, S., & Viegas, S. L. (2021). Neoliberal urban legacies in Luanda and Maputo. African Geographical Review, 40(3), 324–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2021.1937664

- Jornal de Angola. (2023, July 04). João Lourenço: “Corredor do Lobito vai dinamizar as exportações intra-africanas”. Jornal de Angola. Retrieved October 30, 2023, from, https://www.jornaldeangola.ao/ao/noticias/joao-lourenco-corredor-do-lobito-vai-dinamizar-as-exportacoes-intra-africanas/.

- Kituxi, F. M. (2023). Orçamento participativo em Angola: Um instrumento democrático de promoção da cidadania. Whereangola.

- Kumar, T., & Stenberg, M. (2022). Why political scientists should study smaller cities. Urban Affairs Review, 59(6), 2005–2042. https://doi.org/10.1177/10780874221124610

- Lipton, M. (1977). Why poor people stay poor: A study of urban bias in world development. Temple Smith.

- Marques, J. P. (2004). Portugal e a escravatura dos africanos. Imprensa de Ciências Sociais.

- Milheiro, A. V. (2012). O Gabinete de Urbanização Colonial e o traçado das cidades luso-africanas na última fase do período colonial português. Revista Brasileira de Gestão Urbana, 4(446), 215–232. https://doi.org/10.7213/urbe.7397

- Milheiro, A. V. (2021a). Colonial landscapes in former Portuguese Southern Africa. A brief historiographical analysis based on the colonial transport networks. African Geographical Review, 40(3), 214–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2021.1910851

- Milheiro, A. V. (2021b). Late Portuguese colonialism, research, and propaganda in Africa: The promotion of territorial occupation and architectural infrastructure by the general agency for overseas. The Journal of Architecture, 26(2), 212–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2021.1897644

- Moomaw, R. L., & Alwosabi, M. A. (2004). An empirical analysis of competing explanations of urban primacy evidence from Asia and the Americas. The Annals of Regional Science, 38(1), 149–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-003-0137-x

- Neto, M. C. (2012). In town and out of town: A social history of Huambo (Angola), 1902–1961 [PhD thesis]. SOAS, London.

- OECD, U. N., & ECA, A. (2022). Africa’s urbanisation dynamics 2022: The economic power of Africa’s cities. OECD Publishing.

- OECD, UN-Habitat & United Nations. (2021). Global state of national urban policy 2021: Achieving sustainable development goals and delivering climate action. OECD Publishing.

- Ovadia, J. S., & Croese, S. (2016). Towards developmental states in southern Africa: The dual nature of growth without development in an oil-rich state. In G. Kanyenze, H. Jauch, A. D. Kanengoni, M. Madzwamuse, & D. Muchena (Eds.), Towards democratic development states in Southern Africa (pp. 257–304). Weaver Press.

- Pacheco, L., Costa, P., & Oliveira Tavares, F. (2018). História económico-social de Angola: do período pré-colonial à independência. População e Sociedade, 29, 82–98.

- Parnell, S. (2016). Defining a global urban development agenda. World Development, 78, 529–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.028

- Parnell, S., & Oldfield, S. (Eds.). (2017). The Routledge handbook on cities of the global south. Routledge.

- Pasquini, L. (2020). The urban governance of climate change adaptation in least-developed African countries and in small cities: The engagement of local decision-makers in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and Karonga, Malawi. Climate and Development, 12(5), 408–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2019.1632166

- Pimenta, F. T. (2017). Causas do êxodo das minorias brancas da África Portuguesa: Angola e Moçambique (1974/1975). Revista Portuguesa de História, 48, 99–124. https://doi.org/10.14195/0870-4147_48_5

- Power, M. (2012). Angola 2025: The future of the “world’s richest poor country” as seen through a Chinese rear-view mirror. Antipode, 44(3), 993–1014. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2011.00896.x

- República de Angola. (2007). Angola 2025: Angola um País com Futuro.

- República de Angola. (2017). Estratégia nacional para as alterações climáticas.

- República de Angola. (2018). Plano de Desenvolvimento Nacional 2018–2022.

- República de Angola. (2021). Nationally Determined Contributions of Angola.

- Roberts, B. (2014). Managing Systems of Secondary Cities: Policy Responses in International Development, Brussels.

- Robinson, J. (2016). Thinking cities through elsewhere. Progress in Human Geography, 40(1), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132515598025

- Robinson, J., & Roy, A. (2016). Debate on global urbanisms and the nature of urban theory. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 40(1), 181–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12272

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Griffiths, J. (2021). Developing intermediate cities. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 13(3), 441–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12421

- Roque, S. (2009). Ambitions of cidade: War-displacement and concepts of the urban among bairro residents in Benguela, Angola [PhD thesis]. University of Cape Town, Cape Town.

- Ruszczyk, H. A., Nugraha, E., & Villiers, I. de. (Eds.). (2021). Overlooked cities: Power, politics and knowledge beyond the urban south. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Sassen, S. (2005). The global city: Introducing a concept. The Brown Journal of World Affairs, 11(2), 27–43.

- Satterthwaite, D. (2021). The often forgotten role of small and intermediate urban centres. Retrieved February 16, 2022, from, https://www.iied.org/often-forgotten-role-small-intermediate-urban-centres.

- Schindler, S., Mitlin, D., & Marvin, S. (2018). National urban policy making and its potential for sustainable urbanism. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 34, 48–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2018.11.006

- Schubert, J. (2023). Dreams of extractive development: Reviving the Benguela Railway in central Angola. In P. R. Gilbert, C. Bourne, M. Haiven, & J. Montgomerie (Eds.), The entangled legacies of empire (pp. 171–181). Manchester University Press.

- Scott, A. J. (2022). The constitution of the city and the critique of critical urban theory. Urban Studies, 59(6), 1105–1129. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980211011028

- Seawright, J. (2016). The case for selecting cases that are deviant or extreme on the independent variable. Sociological Methods & Research, 45(3), 493–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124116643556

- Seawright, J., & Gerring, J. (2008). Case selection techniques in case study research. Political Research Quarterly, 61(2), 294–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912907313077

- Silva, C. N. (2015). Colonial urban planning in Lusophone African countries: A comparison with other colonial planning cultures. In C. N. Silva (Ed.), Urban planning in Lusophone African countries (pp. 7–29). Ashgate.

- Smit, W. (2018). Urban governance in Africa: An overview. Revue internationale de politique de développement, (10), 55–77.

- Soma, P. (2018). Políticas Pública de Urbanismo em Angola [PhD thesis]. Universidade de Coimbra.

- Storper, M., & Scott, A. J. (2016). Current debates in urban theory: A critical assessment. Urban Studies, 53(6), 1114–1136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016634002

- Teixeira, C., & Santin, J. R. (2019). Poder local em Angola. Desafios e possibilidades. Revista Jurídica (FURB), 23(50), e7907.

- Tomás, A. (2022). In the skin of the city: Spatial transformation in Luanda. Duke University Press.

- Torres, A. (1986). Le processus d'urbanisation de l’Angole das la période coloniale (années 1940-1970). Estudos de Economia, 7(1), 29–50.

- Tostões, A., & Bontio, J. (2015). Empire, image and power during the Estado Novo period: Colonial urban planning in Angola and Mozambique. In C. N. Silva (Ed.), Urban planning in Lusophone African countries (pp. 43–57). Ashgate.

- Tvedten, I., Lázaro, G., Jul-Larsen, E., & Agostinho, M. (2018). Urban poverty in Luanda, Angola.

- Udelsmann Rodrigues, C. (2019). Climate change and DIY urbanism in Luanda and Maputo: New urban strategies? International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 11(3), 319–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463138.2019.1585859

- Udelsmann Rodrigues, C. (2022a). From Musseques to highrises: Luanda’s renewal in times of abundance and crisis. In L. Stark & A. B. Teppo (Eds.), Power and informality in urban Africa: Ethnographic perspectives (pp. 215–236). Zed Books an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Udelsmann Rodrigues, C. (2022b). Hesitant migration to emergent cities: Angola’s intentional urbanism of the ‘centralidades’. City, 26(5–6), 848–869. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2022.2126172

- Udelsmann Rodrigues, C., & Frias, S. (2016). Between the city lights and the shade of exclusion: post-war accelerated urban transformation of Luanda, Angola. Urban Forum, 27(2), 129–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-015-9271-7

- UN-Habitat. (2013). Huambo Land Readjustment, Nairobi.

- UN-Habitat. (2018). Documento do programa país Habitat-Minoth para o desenvolvimento urbano sustentável de Angola.

- UN-Habitat. (2022a). Financing Sustainable Urban Development.

- UN-Habitat. (2022b). Multi-Level Governance for effective Urban Climate Action in the Global South.

- UN-Habitat. (2022c). World cities report 2022: Envisaging the future of cities, Nairobi.

- UNHCR. (2002). The Global Report 2001, Geneva.

- United Nations. (2019). World urbanization prospect: The 2018 revision. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

- Valério, N., & Fontoura, M. P. (1994). A evolução económica de Angola durante o segundo período colonial - uma tentativa de síntese. In Análise Social, 29(129), 1193–1208.

- Waldorff, P. (2016). The law is not for the poor’: Land, law and eviction in Luanda. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 37(3), 363–377. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjtg.12155

- Wheeler, D. L., & Pélissier, R. (2016). História de Angola. Tinta-da-China.

- Wilkinson, G., Haslam McKenzie, F., & Bolleter, J. (2022). Federalism and urban primacy: Political dimensions that influence the city–country divide in Australia. International Journal of Urban Sciences, 26(3), 438–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/12265934.2021.1997631

- World Bank. (2022). Angola. Country climate and development report, Washington, D.C.

- Ziervogel, G. (2021). Climate urbanism through the lens of informal settlements. Urban Geography, 42(6), 733–737. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2020.1850629