ABSTRACT

Despite the benefits of school meals, their provision is often not universal, being it an on-demand, pay-for-service, with the risk of creating significant disparities in their accessibility across schools, regions and social groups. In this paper, we explore food school food policies in Italy from this perspective, analysing the unequal distribution of the service and reflecting upon the implications. Our findings reveal huge disparities that reflect and exacerbate wider social, economic, territorial, employment and gender inequalities. We argue that the current regulatory approach contributes to exacerbating those disparities, and present policy recommendations aimed at extending the service.

1. Introduction

Since the early 2000s, there has been a growing interest in school food policies (SFPs) and school meal programmes due to the increasing health problems associated with poor nutrition in high-income and low-income countries. More recently, the importance of SFPs has expanded to encompass broader environmental, social and economic sustainability goals. School meals are seen as crucial for providing millions of children and adolescents with access to nutritious and healthy diets, especially in times of recession when many families struggle to afford fresh and protein-rich food.

However, despite the well-documented benefits of SFPs, their implementation remains inconsistent and fragmented across countries and regions of the same country. In the European Union, for instance, school meal programmes are still voluntary in at least half of the member states (Bonsmann et al., Citation2014). This voluntary nature, combined with the autonomy of municipalities and schools, leads to significant disparities in the provision, availability and accessibility of the service, ultimately undermining children's rights to food, health and education, and exacerbating socio-economic inequalities.

This paper examines the case of SFPs in Italy and conducts an exploratory analysis of the regional variations in providing and accessing school meal services in Italy, to identify who is excluded from such services. The paper also focuses on the interplay between the regulation and implementation of school meal services and discusses the social, economic, gender and territorial implications of their uneven distribution. While the existing literature and the policy guidance provided by organizations such as FAO or the WHO, have predominantly focused on best practices and successful examples of school meal provision to highlight the benefits and encourage their adoption, and on cross-country differences (Swensson et al., Citation2021; WHO, Citation2006, Citation2021), there is limited knowledge about the implementation of SFPs at the regional level and the wide differences that persist within countries. The absence of data and studies leaves unanswered questions about which groups are left behind and about the causes and consequences of such disparities. This paper aims to fill this gap by investigating the intersection between the regulation of school meal services at the national, regional and local scales and territorial inequalities, seeking to understand the plurality of drivers and implications of the lack of minimum standards for the provision of school meals.

In this respect, Italy serves as an illustrative case study due to its peculiar regulatory framework, a problematic subdivision of policy responsibilities between levels of government, and the huge socio-economic differences which historically, and still today, split the country according to very clearly north–south and urban-rural divides. To explore such divides can, therefore, be particularly effective in highlighting the difficulties in translating existing laws and policy schemes into practice effectively and consistently across the country. The strong regional autonomy in Italy and the resulting territorial differences have significant implications for the provision of school meal services and raise questions about the fulfilment of fundamental rights and the role of the state and local authorities in ensuring these rights.

Italy is also interesting as a case study due to the substantial funding it received from the European Union as part of the post-COVID resilience and recovery plan (PNRR), including funds allocated to extend school meal services. Understanding how SFPs operate in Italy, identifying existing gaps and addressing the uneven distribution of the service across the country are urgent and crucial tasks to ensure funds are allocated to where they are needed the most.

The structure of the article is as follows: the next section focuses on the organization of school food services in Italy, highlighting the negative consequences of conceiving it as a voluntary, on-demand, pay-for-service. Section three discusses the evolution of school food services, contextualizing the trend towards decentralization and outsourcing within broader EU policies aiming for the marketization of essential services. Section four presents an analysis of data on the provision of school meal services for primary school children (6–10 years of age) at various sub-national scales, considering several parameters, such as gender-disaggregated employment data, economic wealth, etc. The aim is to highlight the huge disparities in the access to full-time schooling and, consequently, food school services throughout the country, and how those reflect wider social, economic, territorial, infrastructural, institutional, employment and gender imbalances. Section five explores the normative and institutional complexity of SFPs and their distribution across different levels of governance, examining how this contributes to further inequalities, and impacts the capacity of public authorities to establish adequate services and access national funds. Finally, the conclusions summarize the main findings, highlighting the most problematic dimensions of SFPs in Italy and proposing some potential solutions.

Given that school meal services are still treated as a voluntary service in many countries, this analysis will be of interest to academics and policy-makers beyond Italy who may face similar problems and outcomes. The aim is to stimulate further debate and research, moving beyond the demonstrated benefits of school meals to identifying and addressing the gaps in their provision.

2. Food for school in Italy: an individual–voluntary service

The provision of school meal services in Italy was established in the early 1900s, a time when the country was undergoing significant socio-economic transformations. The primary objective was to make schooling more appealing to families from lower socio-economic backgrounds,Footnote1 to increase attendance rates and reducing illiteracy. For example, school meals played a crucial role in the process of defamiliarization (Esping-Andersen, Citation1990), a process which has yet to be fully realized in a country like Italy (Andreotti et al., Citation2014), where gender roles remain asymmetrical, care responsibilities are unbalanced and participation in the labour market is highly unequal between men and women.

The historical absence of universal welfare policies in Italy can be traced back to the traditional family and charitable approach to welfare, where families were responsible for meeting their members’ needs with support from local associations and religious institutions, i.e. public bodies without a clear regulatory framework and with discretionary decision-making power in terms of citizens’ accesses to benefits and provisions. The lack of a comprehensive public provision and the reliance on charitable and discretionary services have further perpetuated regional and social inequalities. The lack of recognition of ‘assistance’ as a right and the further decentralization of welfare policies, have hindered the development of national policy instruments and the establishment of a robust administrative-bureaucratic culture able to implementing measures uniformly in the country (Ranci, Citation2015).

Initially, school meal services contributed, therefore, to a ‘democratization’ effect (Dewey, Citation1916) and the reduction of inequalities. This trend changed with the advent of compulsory education and the strengthening of coercive measures to ensure school attendance. In this context, the dual function of school meals as an instrument to alleviate hunger and as an instrument to encourage school attendance, diminished. As mechanisms enforcing compulsory education strengthened and school attendance became mandatory, the need to entice families with the benefits of school meals decreased. The service became voluntary, offered only upon request and not mandatory: its provision is demanded by each school in agreement with local authorities. Families can access the service only by selecting schools where it is available. In practice, not all schools offer the service, and finding a school that provides it is challenging in many areas. Consequently, the demand for the service is influenced not only by the number of families requiring it but also by its availability.

It also needs to be added that school meals in Italy are not for free. A complex system, tied to family income and the number of underage children in each family, determines how much each student pays. Only in very few cases is the service free for families with meagre income. Eligibility for free school meals is determined at a local level, and additionally, in some cases, families are entitled to the free service only if they are residents within the Municipality where the school is based. This is particularly problematic in rural areas, where often one school covers catchment for more than one municipality. As a result, students are usually expected to make an (expensive) contribution ranging between approximately 4 and 6 euros per meal (Rete Commissione Mense Nazionale, Citation2019, p. 18).

The fact that school meals have a cost for the families affects their willingness to opt-in for such services and to choose schools that offer full-day schooling. This, in turn, impacts the provision of school meal services and the perception of the service as non-essential due to the lack of demand. As a result, the demand and supply of this service vary significantly at the territorial level as we will show in the next sections.

The original vision of school meals in Italy, which aimed to provide a social service and reduce inequalities, has been lost. It is interesting to note that this change coincided with the substantial entry of women into the labour market in the second half of the 1970s. As women gained increased education levels and began to emancipate themselves from their exclusive roles in caregiving and non-market labour, the social system, which previously had a strong patriarchal influence (Beccalli, Citation1994), was transformed.

In addition, the increased demand for workers in the service sector encouraged families, especially those from rural and marginal areas, to send their children to school and break free from a socio-economic reproduction system where education was not considered a requirement for entering the labour market. Instead of being viewed as a service that frees up women's time for work, full-time schooling became a support for families already consisting of dual earners (Del Boca et al., Citation2005). The allocation of scores in childcare access rankings, for example, favours households where both adults are employed. In this context, school meal services play more of a substitute role for other forms of welfare, whether family-based or public, for those already active in the labour market, rather than serving as a means to support gender equality or to assist employment-seeking.

This situation increases the risk that areas with lower employment rates for women coincide with areas where school meals are less available. Furthermore, as women enter the workplace, at least in certain areas, a dichotomy seems to emerge between families who opt-in to school meals because both parents/carers work, and those who don't because one family member, usually the mother, stays at home. This could also impact working mothers’ willingness to use the service for fear of stigmatization as being ‘unable to care’ for their children (Marra, Citation2012).

3. School food policies: some recent trends

Since the early 2000s, European countries have shown a growing interest in SFPs, largely influenced by actions taken by the WHO and the UN. These actions are mostly in response to health problems associated with poor nutrition in Western capitalist states and the rise in poverty in urban and marginalized areas. Child obesity and overweight, especially among 6–9-year-olds, have become a significant concern as they can have long-lasting effects on the physical and mental development of children. This renewed attention has inspired numerous studies and policy guidelines emphasizing the benefits of school meals. The WHO published a crucial study in 2006, recognizing the central role of school meals in providing healthy nutrition, educating on proper eating habits and addressing nutritional deficiencies related to poverty in European countries. Since then, attention to SFPs has remained central in public and institutional discourses (Schmidt, Citation2008), with debates focused especially on the benefits they can entail.

Research has highlighted the educational benefits of healthy eating and the importance of involving students and parents in decision-making processes related to the implementation of the service (Swensson et al., Citation2021). Examples of successful programmes have been highlighted worldwide, including cases in Brazil, Ethiopia, France and Italy. These studies have also explored the economic value of school meal programmes and their potential for promoting organic food production and for the local economy.

Surprisingly, instead, SFPs have received little attention from other perspectives. The lack of analysis from political and socio-legal perspectives may be attributed to the integration of SFPs into broader policies with greater political and financial impact, such as health and educational policies. In this context, SFPs often play a secondary role within transversal inter-ministerial public policies, making it challenging to identify their specificities and monitor their implementation. The fragmentation of these policies across different public authorities and their association with experimental school food programmes (Levesque et al., Citation2020) makes it difficult to gain an overall understanding of their functioning and effects.

The 2014 research ‘Mapping of National School Food Policies across the EU28 plus Norway and Switzerland’ by the EC JRC (Bonsmann et al., Citation2014) shows that around 50% of SFPs result from decisions made by a combination of ministries. The remaining 50% are under the responsibility of the Ministries of Health (29%), Education (18%) and Agriculture (3%). At the same time, for just under half of the EU28 countries, SFPs are voluntary (13 countries) and non-mandatory (15 countries). This same pattern can be found in Italy, where SFPs often are the result of the joint effort of the Ministries of Education, Health and Agriculture. Additionally, regional authorities in Italy can issue specific guidelines and norms to complement national ones.

Over the past two decades, many European countries have shifted from in-house provision to externalizing the service and procuring food through public contracts. In Europe, approximately 50,000 public authorities are engaged in food procurement, with an annual investment of around 82 billion euros (Caldeira et al., Citation2017). In Italy, recent data released by Rete Commissioni Mensa Nazionale (Citation2019) show that, among a sample of 257 municipalities offering school meals, 71.43% of the sample cases entrust the canteen service to an external company selected through a public tender and only in 8.4% of cases schools manage the service internally.

This heavy reliance on procurement reflects a broader trend in Europe towards liberalization and outsourcing of public services, which has severely and increasingly impacted the welfare state (Ferrera & Rhodes, Citation2000), particularly due to the austerity politics adopted after the 2008 financial crisis. The rules and conditions of public procurement, as well as the power dynamics between public, private and third-sector actors, cannot but exacerbate the differences and inequalities between and within countries, also due to the variety of regional and local regulations.

These discrepancies are even more evident if we consider how SFPs have become ever more complex over time as they are seen as instruments to achieve multiple strategic objectives, including poverty reduction and food security. In some contexts, these policies support specific food production and distribution networks and local producers or aim to achieve environmental goals by favouring, among other things, transport on hybrid vehicles or organic food (European Commission, Citation2021).

From a regulatory perspective, some efforts have been made to guarantee some uniformity in the delivery of school meal services. At the European level, the public contracts directives (2014/24/UE 2014/23 and 2014/25) provide, for example, a general framework for public procurement. However, the 2014 Directives have granted broad autonomy to member states regarding the implementation of the procurement process (Andhov et al., Citation2022). These approaches have led to the adoption of different measures by EU countries, raising the potential for conflict with the principles of non-discrimination and liberalization endorsed by the Directives (see Article 18 of the 2014/24/UE Directives).

Furthermore, regional and local administrations often supplement the national norms, as we will discuss in the next sections. In the case of school meals, the responsibility to regulate and implement the procurement process lies primarily with local administrators and individual schools, as already mentioned. The varying capacity and awareness of the importance of SFPs among different regions and places conditions their success in enacting supplementary legislation creating uncertainty and potentially amplifying existing disparities (Pavolini & Saraceno, Citation2022).

4. Regional disparities in the access to school meals in Italy

The fact that school meal services are individual/voluntary, on-demand services and their provision is left to the autonomy of each Municipality and school, risks leading to unequal availability and access. This has two consequences: first, it reflects pre-existing inequalities, and second, it exacerbates these differences along a plurality of socio-economic boundaries, such as regional disparities and gender imbalances in labour market participation. This differentiation is particularly problematic in light of the dramatic increase in the socioeconomic distance between the wealthiest, most dynamic and urbanized areas and the rest of the country, which can be observed in the last decades in Italy and in other advanced countries. A regional analysis of the unequal access to school food services can, therefore, be relevant per se as it highlights an important dimension of such inequalities, and indicative of wider imbalances in the access to the service and of their implications for families’ well-being, gender differences socio-economic and labour market outcomes.

Methodologically, the analysis presented hereafter is mainly exploratory and descriptive. The aim is not to outline an overall explanation but to highlight the plurality of dimensions that, in our view, are relevant when approaching the topic from a non-reductive perspective. This is particularly needed, we believe when it comes to designing appropriate policy and regulatory schemes, which will be discussed in the next section. Analytically, the regional analysis is performed at different geographical scales, to avoid results being affected by the specific partition used in aggregating the data, and because each of those scales can provide different insights about the drivers and consequences of existing inequalities.

No official statistics exist about school meal services in Italy. Recently, the Ministry of Education has made available some schools’ microdata which include detailed information on students, teachers, school facilities, etc.Footnote2 To understand the distribution of school meal services on the Italian territory, we, therefore, elaborated microdata concerning the number of students in all public or quasi-public primary schoolsFootnote3 opting for ‘tempo pieno’ (literally ‘full-day schooling’). The ‘tempo pieno’ is chosen voluntarily by families and allows students to stay at school until around 3–5 pm instead of 12.30/1.00 pm (the latter being the time when primary school usually finishes in Italy). ‘Full-day schooling’ in Italy always requires the provision of school meals; vice versa, no school meals are provided in schools that do not offer ‘full-day’ schooling.Footnote4 Therefore, the availability of full-day schooling coincides with the availability of the school meal service.

The two services are, in fact, often dealt with together in policy documents and debates about schooling in Italy. For instance, in the Italian Post-COVID Recovery Plan financed by the EU (the so-called PNRR) investments and targets for building school meal facilities are linked to the objective of increasing the number of schools providing full-day schooling.Footnote5 Yet the absence of official data denotes a problematic lack of attention on these crucial services and, together with the absence of any official report on the matter, puts under question the role played by the Ministry of Education in ensuring that a minimum level of service is guaranteed across the country. It is not clear whether the Ministry even investigates the impact, or the causes, linked to the absence of school meal services in certain areas. It would be helpful to have data also on the way the service is provided (for example, whether the meal is cooked in-house or outsourced, whether the service is offered in conjunction with other schools, the quality and costs of food, etc.) and on the users of the service (for example, gender-disaggregated data, performance, etc.). The absence of such information constrains the capacity to monitor the quality of the service, its impact and its effectiveness, and, arguably, curtails the debate on the topic.

Our elaboration of country-level data shows that afternoon schooling is indeed not very common in Italy. Approximately 54% of all Italian primary schools declare having no students opting for ‘tempo pieno’.

This data can be disaggregated, as already mentioned, at different administrative levels. The regional level is the first and most relevant, given that the 20 Italian Administrative Regions are primarily responsible for education and schooling.

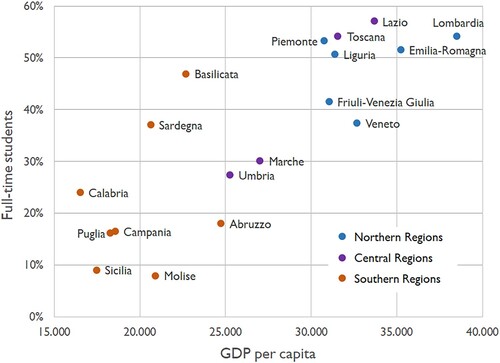

Regional data in show heavy geographical imbalances: access to school in the afternoon ranges from 8% in Molise – where 90% of schools declare having no full-time student – to 57% in Lazio, the Region where the Italian capital, Rome, is situated. The diagram compares data on ‘tempo pieno’ with the average per-capita income. In most regions in the South of Italy – notoriously lower-income than the more prosperous North – just a quarter of primary school students benefit from full-day education, while in most Northern Regions, they represent a majority. The data, therefore, seem to highlight a correlation between access to full-time schooling and wider north–south disparities linked to GDP per capita.

Figure 1. Full-day schooling students over total students in primary schools, per-capita income and territorial division, Italian Administrative Regions (with the exclusion of Val d'Aosta and Trentino-Alto Adige), 2020. Source: Italian Ministry of Education, Istat.

However, the same data aggregated at the level of each of the 105 Italian provinces show an even more fragmented and uneven country. Access to ‘tempo pieno’ ranges from 96% of students in the Province of Milan – where only 1% of schools declare having no full-day students – to 4.9% of full-day students in the Sicilian Province of Ragusa. Such an extreme disparity is quite surprising, even for a highly diverse and geographically uneven country like Italy.

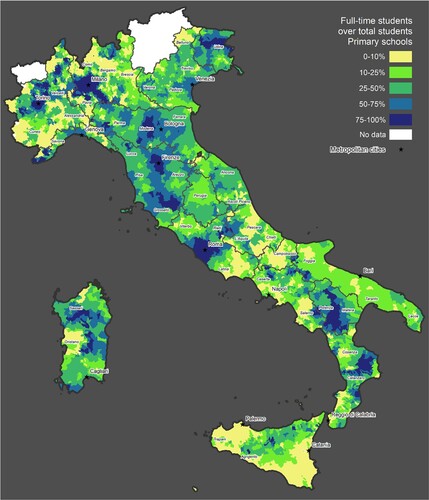

To further appreciate the variability of the service within the same region, we have disaggregated data at the municipal level (). To ‘regionalize’ the variable, obtain a clearer representation and eliminate missing data (i.e. Municipalities with no primary schools), in , the number of students is calculated by summing up the values per Municipality with that of their neighbouring municipalities.

Figure 2. Full-time students over total students in primary schools in Italian municipalities and their contiguous areas, 2020–2021. Source: Italian Ministry of Education.

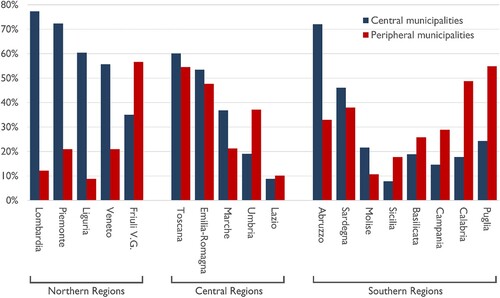

Despite such correction, the map does not seem to display any clear geographical pattern. Areas with very few students opting for full-time are frequent in the South, and also in Northern and particularly North-Western regions. Metropolitan cities are among the areas where the percentage of full-time students is the highest, but not everywhere in the country. In most of the North and Central of Italy, access to ‘tempo pieno’ ranges from 70% to 80% in more urbanized and metropolitan areas, while this goes down to 10–20% in peripheral and ultra-peripheral areas.Footnote6 However, this is not the case for many Southern regions, where metropolitan and ‘central’ places rank relatively low in terms of full-day students, while marginal, low-urbanized, inner areas show surprisingly high access rates. It is mainly the case of the Southern Regions of Puglia and Calabria and, to a lesser extent, Basilicata, Campania and Sicilia. Still, it is also the case of the central-northern Regions of Umbria and Friuli Venezia-Giulia (). This may be due to the poor accessibility of schools in those areas, or due to the lack of any alternative activity for children in the afternoon, which may increase the convenience of keeping students in school over lunch. Interestingly, no Administrative Region, even in the North, seems to display a territorially homogeneous pattern.

Figure 3. Full-time students over total students in primary schools in Italian municipalities classified as either ‘central’ or ‘peripheral’ by the National Strategy for Inner Areas, 2020–2021. Source: Italian Ministry of Education.

This evidence shows the complexity of the processes that may explain the uneven access to full-day schooling and school meals. Such unevenness may be associated with women's participation in the labour market, the role of domestic labour and the organization of family welfare, and/or due to cultural differences, which are also associated with more general socio-economic and territorial conditions. Access to full-time may be limited by structural deficiencies of schools such as the absence of adequate school spaces and facilities. It is beyond the scope of this paper to delve into what these causes might be or, worse, to second guess them. However, looking at how access to full-time correlates with other variables can provide interesting insights and enrich the descriptive analysis presented above. Such analysis is conducted at the level of each of the 105 Provinces for which data on full-time students are available. The complete list of correlations is in .

Table 1. Correlation between full-time schooling in Italian primary schools per Province, and several social, economic, employment, education and territorial indicators, 2020.

A first set of conditions that may explain the unequal access to ‘tempo pieno’ could be due, as already mentioned, to structural deficiencies, particularly in the spaces that schools can dedicate to the consumption of meals. This dimension is particularly relevant given that policies that promote ‘tempo pieno’ aim almost exclusively at addressing these structural deficiencies. A paradigmatic and recent example in this regard is the above-mentioned PNRR plan, which promotes an extension of the number of students that opt for ‘tempo pieno’ through the construction or restructuring of the school's canteens.Footnote7 Access to food school services is strongly correlated with the presence of a space dedicated to delivering those services (line 1 in ), but this may be the consequence rather than the cause of the low access rate to those services. However, the correlation is significant, although moderate, also with other indicators of schools’ structural deficiencies, such as the presence of ‘special’ spaces such as gyms, PC/technical rooms, collective spaces or auditoriums (line 2 in ), indicating that such structural deficiencies may also concur to explain the unequal distribution of the service. As a confirmation of this, access to ‘tempo pieno’ is also moderately correlated with school buildings’ average age (line 3 in ).

A second set of conditions may be due to socio-economic well-being, as already observed at the regional scale. Among all the variables we considered, the strongest correlation is with value-added per inhabitant (+0.59, line 4 in ). The correlation with the level of education, exemplified by the percentage of graduates in the total population, is also significant although lower (line 5 in ).

At the same time, the analysis of correlations confirms that access to food school services does not seem to be associated with strictly territorial conditions of marginality such as the extension of mountainous areas and forests (lines 8 and 9 in ). It is correlated to the degree of urbanization as expressed by population densities (+ 0.334, line 7 in ), but this is probably due to the correlation of this variable with other socio-economic indicators, more than a direct association, given the differences described above in terms of access rates between central vs. marginal municipalities ().

A fourth set of conditions may be due to access to employment. Correlations with labour market indicators are always significant and substantial (lines 10, 11 and 12 in ), particularly in the case of the labour force participation rate (+0.52) and employment rate (+0.51) and less in the case of unemployment (−0.43). The association seems, therefore, stronger with the structural conditions of the labour market than with conjunctural circumstances.

A fifth set of conditions is again related to the labour market, but specifically to women’s employment. Women's activity and employment rates (lines 13 and 14 in ) show some of the strongest correlations (+0.54). Still, this evidence may reflect the association between access to ‘tempo pieno’ and the general (male and female) employment rates. To appreciate to what extent such access is specifically associated with gender inequalities, we used the difference in labour force participation and employment rates between males and females (lines 16 and 17 in ): the correlation is strong (+0.53) and highly significant.

Moreover, and not surprisingly, areas where full-time students are fewer are also areas where access to pre-primary school services is low as expressed by the number of places available for the total population of potential beneficiaries (+0.515, line 18 in ) and the budget Municipalities allocate to childcare services (+0.5, line 19 in ).

Finally, access to ‘tempo pieno’ could also be associated with students’ learning achievements and school careers, due to the better learning opportunities enjoyed by students staying in schools over the afternoon. No significant correlations appear between those variables at the provincial level (lines 20 and 21 in ).

What the above indicates is that the highly uneven access to school food services observable in Italian provinces is indeed associated with many sources and dimensions of inequality. The analysis did not highlight any primary association, confirming that the unequal access to food school services is due to various interrelated causes. Finding a solution or a single driver that may promote higher access is, therefore, equally challenging. The institutional conditions within which such a strategy should be implemented, as discussed in the next section, are also differentiated.

Given that we considered a wide range of indicators, which in many cases are also correlated with each other, and in order to highlight what are the most significant and explanatory variables, we run a ‘partial correlation’ among a sub-set of indicators,Footnote8 i.e. calculated each correlation by including all the other indicators as control variables.

Among the eight indicators considered, the analysis of partial correlations returned only three significant associations. The strongest is between access to full-time schooling and the school’s structural deficiencies, also because this indicator is loosely correlated with the others. Interventions aimed to solve those deficiencies, like those funded by the PNRR, may, therefore, have an impact but, also due to their scarcity, cannot be expected to significantly alter the unequal geographies described in this section, unless a much more comprehensive structural adjustment plan for school buildings is launched. The second significant correlation is with the wealth and quality of the local economy as expressed by the value-added per inhabitant. The third and most peculiar significant correlation is with the difference in employment rates between men and women. Full-time schooling seems, therefore, not significantly correlated with the general conditions of the labour market, but specifically with gender inequalities. In this respect, it is challenging to discern if women's low participation in the labour market is the cause or consequence of the low demand for full-time schooling. The same applies to the other variables. In any case, the situation described above reflects and actively contributes to keeping women out of the labour market and amplifies substantial social, economic and gender inequalities.

5. The regulation and unevenness of school food policies in Italy

School food policies are complex and characterized by a high level of autonomy at the sub-national level. National rules and guidelines set standards on the quality of food, the organization and management of the service and purchasing procedures. Regions and other local authorities can supplement these regulations, and some have done so to varying degrees of success. The Regions’ ability and political will to regulate and implement SFPs affects how the service is provided, whether it is provided at all, and the funding each Region gets for the service, as we will explain below. The way SFPs are designed and implemented in Italy, in this framework, not only raises social justice concerns but may even breach the constitutional obligation to guarantee a minimum level of essential services across the national territory.

At the central level, school meal services are regulated by the National Guidelines for School Catering,Footnote9 which focus on the management of the service, the attribution of competence between municipalities and the rules to follow for food purchase. The guidelines also promote the Mediterranean diet and establish quality and nutritional standards. It is not our intention to downplay the importance of those provisions and, more in general, of using SFPs to educate children about healthy diets, especially in light of increasing obesity rates. However, the Guidelines do not mandate the provision of the service, leaving the decision to each municipality and school, therefore, also limiting their impact to only those who can access it. Notwithstanding those country-wide standards, moreover, each municipality is ultimately responsible for organizing and procuring the service.Footnote10 The guidelines acknowledge the social and cultural value of school meals but do not require their provision or establish control mechanisms to ensure their availability, not even in terms of an obligation to guarantee at least a minimum level of service.

The guidelines refer to international human rights norms, such as the ‘Convention on the Rights of the Child’ adopted by the UN in 1989 – where children's right to a healthy diet is recognized – and to the ‘European Social Charter’ of 1996. However, they do not go beyond general statements of endorsement. No mechanism is in place to understand whether the absence of the service is linked to the absence of an actual or potential demand from families, or by municipalities’ lack of resources or capacity to set up the service. Given the huge disparities described in the previous section, this approach is internally contradictory as well as in conflict with the constitutional mandate to ensure equality in the access to essential services nationwide (arts. 117–119 of the Italian Constitution).

Notwithstanding the autonomy Regions enjoy in this as in other policy domains, the state must guarantee a minimum level of provision and performance for essential services in all the country, also by providing additional resources to Regions unable to guarantee these standards. Yet the Italian state does not put in place any such guarantee but it tends to provide additional funding to Regions that already provide school meals. For example, data on organic school feeding programmes (mense bio in Italian) show that the major recipients of these funds are the regions where access to school meals is the highest: the Southern Region of Calabria does not even feature in the list of beneficiaries, while the Central-Northern Region Emilia Romagna obtain more funds than all the regions of the South taken together.Footnote11

Another relevant case is the above-mentioned investment in school food services included in the PNRR to promote full-time schooling.Footnote12 The investment aims mainly to extend the service by creating spaces for the distribution of meals in school buildings where they are absent, but approximately one-third of the projects fund the improvement of existing spaces, hence favouring those who already provide the service. Only 60% of the funding available has been allocated through the first tender. Southern Regions obtained less than expected: 35% of total funds (the target was 40%). However, the distribution of funding is varied, also among Southern Regions, very much depending upon the ability of municipalities to present valid proposals. In the South, the highest ratio between the funding obtained and the number of schools is registered in the Regions Basilicata and Abruzzo whereas Sicily, Sardinia, Campania and Molise rank very low. Overall, however, the correlation between the ratio of new school food services funded over the total number of schools without such service, and the ratio of schools without food services over total schools per region, is negative (−0.52), and highly significant. This indicates that, on average, Regions that needed such funding the most obtained the least. In other words, even funding schemes that have the explicit objective of reducing territorial inequalities end up paradoxically increasing them, i.e. incur the so-called Matthew effect: they reward the regions with the best endowments and starting conditions at the expense of the most disadvantaged ones (Cantillon, Citation2011; Merton, Citation1968).

One could argue that school meal services are not essential services whose provision must meet a minimum level of performance. It may be contended that only teaching activities are deemed essential within schools. However, this argument fails to acknowledge the numerous benefits of school meals and their instrumental role in fulfilling numerous human rights, including education. Being closely linked to full-time schooling, the availability of school food services raises also concerns about the advantages in terms of learning for those who access them. The above-mentioned argument now contradicts a landmark decision of the Italian Supreme Court of Cassation, which equated school meal services with other school activities, and established that they are integral to the education service as they contribute to the overall function of education.Footnote13

The absence of minimum standards for essential services, also known as minimum levels of performance in Italy, is a widespread issue affecting many public services provided at the regional level. This problem stems from a poorly designed and frequently criticized reform of regional autonomy (as outlined in Legislative Decree 267/2000) that has not yet been fully completed and that disattends the mandate of the Italian Constitution. What is particularly striking in the case of school meals is not only the absence of a policy aimed at addressing regional disparities in their provision but also the complete disregard for the unequal access to the service and the discriminatory effects it may have. This disregard is further evidenced by the lack of any monitoring system and even official data regarding school food provision, as already mentioned.

The service is also subject to the rules outlined in the Procurement Code, which has been amended and updated several times since its enactment in 2016.Footnote14 The Code ensures, at least in theory, a certain degree of uniformity across the country as it establishes comprehensive rules that all public entities must adhere to, including principles of open competition, non-discrimination and equal treatment of suppliers. The Code also mandates that all contracting authorities apply specific ‘Minimum Environmental Criteria’ designed to promote energy efficiency and environmental sustainability as well as minimum social standards.Footnote15 As a result, specific regulations have been introduced to promote so-called short supply chains or to encourage the adoption of environmental certifications such as the Ecolabel. Interestingly, Italy was among the first European countries to adopt mandatory environmental criteria for contracting authorities. However, a national survey conducted by the 'Osservatorio Appalti Verdi' (observatory on green procurement) in Citation2018 revealed that only about 28% of municipalities consistently implemented these green criteria in food tenders (Swensson et al., Citation2021), confirming how even the setting of country-wide standards ends up exacerbating rather than reducing existing disparities. A recent judgement by the Consiglio di Stato, the Italian supreme administrative Court, had, therefore, established that tenders failing to comply with Minimum Environmental Criteria must always be re-issued.Footnote16 Finally, there are specific rules, such as Law 199/2016, aimed at combatting the exploitation of agricultural work and realigning wages in the agricultural sector.Footnote17

Regarding procurement, Regions can supplement but cannot substantially deviate from the rules and principles outlined in the Code, including market access, equal treatment, non-discrimination and environmental standards, along with other specific norms related to transparency, advertisement, thresholds, etc. At the regional level, additional laws and guidelines have been implemented to encourage, for example, the use of organic or quality products in public school canteens. The absence of consistent guidance on how to implement these standards is contributing to a lack of adequate enforcement. As a result, significant disparities arise in the success with which Regions pursue such aims and utilize food procurement to promote environmentally friendly products and support local businesses.

Veneto was the first Italian Region to introduce a law on so-called km zero products,Footnote18 i.e. locally produced food, and other regions in Central and Northern Italy have followed suit. Southern regions, such as Puglia and Basilicata, attempted to introduce similar criteria with a focus on regional food, but their laws were revoked by the Constitutional Court for violating European principles of market access, competition and non-discrimination.Footnote19 These laws were reminiscent of the ‘buy Irish’ measures in the 1970s, which were also deemed non-compliant with EU rules by the Court of Justice of the EU.

The inability to implement rules and measures that comply with European and constitutional norms is not merely a legal matter but affects also a Region's ability to access additional funds, as discussed above.

Other national policy measures – in most cases non-binding – concern more specifically the organizational and economic management of canteens: the National Action Plans on Green Public Procurement, the Responsible Business Plan and the National Plan on Sustainable Development Goals. These Plans, although comprehensive, have not yet been fully implemented at the national or regional level, thus remaining only good intentions.

As a result, the policy and legislative framework is fragmented and complex, and this poses challenges for local authorities, particularly those with limited capacity, fewer staff and less experience in managing public services, especially in socio-economic disadvantaged contexts. Currently, there is a lack of any explicit effort to bridge these gaps.

Moreover, national rules and guidelines almost exclusively focus on service management, food safety and nutrition standards, and neglect almost completely their role in realizing fundamental economic and social rights, while public funding schemes allow for an even more unequal distribution of resources favouring the more competitive and skilled at applying for funding, rather than being allocated to regions most in need of assistance and where the service is lacking.

6. Discussion and conclusions

In this article, we have discussed the evolution of SFPs in Italy, presented a regional analysis of the access and distribution of full-time schooling across the national territory, and described the main rules regulating this policy domain. While the literature has so far mainly focused on best practices and examples of excellence in the provision of school meals, to emphasizing their benefits and encourage their uptake, our approach has been to explore where and who is left out. We have examined whether school meal services are available on the national territory and considered the possible impact of their uneven distribution. Understanding and addressing such a gap is necessary, particularly given the importance of school meals and full-time schooling as instruments of social justice. The significant normative and organizational autonomy enjoyed by Regions and municipalities in establishing and implementing SFPs has resulted in a multitude of approaches, with the potential not only to consolidate but also to exacerbate existing inequalities and gaps.

In Italy, SFPs are viewed as measures to support dual-earner families, leaving broad autonomy to municipalities in whether and how they meet the existing and potential demand for the service, and not considered proactive tools for social cohesion, women's employability, improving food security in disadvantaged contexts and a multiplicity of social rights.

The outcome, as we have shown, is a significant territorial discontinuity and huge geographical disparities, albeit those have different forms across the country. In most of the northern and central regions, access to school meals is concentrated in highly urbanized areas and significantly reduced in peripheral ones. The opposite pattern seems to emerge in some southern regions. Hypothetically, the broader access to these services in peripheral places compensates for the lack of local activities for children and may be due to poor accessibility conditions. Generally, areas with better socio-economic conditions have greater access to school meals, which primarily serve as indirect and voluntary support for those families where all parents are employed.

We have also highlighted a deficient service supply in regions with substantial gender disparities in the labour market. Gender inequalities, we have shown, emerge as the most significant association when it comes to labour market conditions, while more general indicators such as low employment rates seem to play a secondary role. While it is understandable that areas with lower women’s labour market participation have less demand and, subsequently, a lower supply of school meal services, this inevitably leads to reduced women’s employability, in a country that has some of the worst indicators among all EU countries in terms of gender disparities in the labour market (European Institute for Gender Equality, Citation2022).

The broad range of goals that school food services aim to achieve makes such significant disparities cast a shadow over the state's obligation to provide a minimum level of essential services. In Italy, these services are provided voluntarily and on demand, placing a heavy financial burden on most families. While national and regional guidelines offer specific instructions on nutritional aspects and other management issues, local administrators are responsible for establishing precise operational procedures for practical implementation. Unfortunately, no standards have been set regarding the availability of the service, such as ensuring a minimum number of schools offering it. The question of whether the service is present is simply neglected, as confirmed by the lack of official data on the issue.

Regions that have attempted to promote such services have done so often solely to capitalize on the indirect benefits they provide to the local economy. However, southern regions have faced difficulties in their legislative strategies and accessing public funding. The current policies aimed at providing additional funding for full-day schooling or the purchase of organic food are not designed or allocated on a compensatory basis to guarantee a minimum level of services. Instead, they are highly competitive, contributing to the disadvantage further those who are already marginalized.

The continuation of SFPs as voluntary and individual policies results in their dependence on territorial economic and institutional factors, leading to significant inequalities. The approach to SFPs in Italy needs to be reconsidered, and the state should define rigorous minimum standards related not only to the quality of the service but also to its availability. It is time to enforce the decision of the Court of Cassation which established that school meals are an integral part of educational activities. This implies that the voluntary and on-demand nature of the service should be questioned and reconsidered.

In the short term, the resources available through the PNRR (National Recovery and Resilience Plan) present an insufficient opportunity for the country to bridge existing gaps. Adequate, ordinary, additional and equitable financing should be guaranteed to ensure equal access across the entire territory.

Based on our analysis, we believe it is time for the Italian state to recognize the broader social significance of school meals and give actual implementation to the so far only generic endorsement of human rights norms. This implies that school meal policies should not solely focus on supporting dual-earner families but also aim to pro-actively promote social mobility, women's employability and food security in disadvantaged contexts. National and local authorities need to gain awareness about the multiple objectives and social rights associated with school meals. Efforts should be made to provide adequate funding and support in regions with low employment rates, particularly for women, to reduce gender disparities and enhance women's employability. National guidelines should at least include provisions to ensure a minimum number of schools offering the service in each place. Finally, the state should ensure equitable access to additional financing: the current competitive nature of this funding cannot but perpetuate existing inequalities. A more radical option that should be considered is to make food school services compulsoryacross the country. While this undoubtedly carries financial implications for the state, it wouldensure crucial support for children's development and for reducing labour and gender inequalities.

In all of those respects, further research is necessary. The regional analysis we presented is mainly descriptive of the huge disparities persisting in a country like Italy, and merely indicative of the main drivers and consequences that, in our view, may explain such inequalities. We tried to address these differences, and the variety of the structural, institutional and policy conditions that may explain them, comprehensively. Our results should be complemented with more specific quantitative and qualitative research, including the in-depth analysis of relevant case studies. Our invitation is, more in general, to go beyond the identification of best practices and successful examples of school meal provision to explore who and where is excluded from such benefits, reflect upon the causes and implications of the significant disparities that emerge and how those intersect wider social, economic, territorial, institutional, employment and gender inequalities.

Further research is also needed to explore whether the policy recommendations we outlined would be feasible to address current deficiencies and their implications, and the extent to which they would meet the favour of parents and children. Making school meals mandatory certainly requires additional resources and higher immediate costs for public finances, but those costs need to be evaluated in light of the overall, long-term benefit of such policies.

By implementing these recommendations, we believe, Italy can take significant strides towards achieving equitable access to school meals and full-day schooling, and use school food policies as a crucial instrument of social justice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Filippo Celata

Filippo Celata is full professor at the University of Rome La Sapienza where he teaches Economic Geography, Local Development and Spatial Data Analysis. His research is about urban and regional economies and policies, with a particular focus on regional disparities and sociospatial inequalities. His work has been published in some of the main international journals in human geography and urban studies.

Annamaria La Chimia

Annamaria La Chimia is Professor of Law and Development and Director of the Public Procurement Research Group at the School of Law, University of Nottingham and Research Fellow at Stellenbosch University.

Silvia Lucciarini

Silvia Lucciarini, MA in Economic Sociology and PhD in Urban Studies, is Associate Professor of Economic Sociology at the Department of Social and Economic Sciences, Sapienza University of Rome. Her main research fields focus on the mechanisms of (re)production of inequalities, privileging both the spatial and the organizational dimensions of public and/or experimental policies. Her contributions have appeared in journals such as International Review of Sociology, International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, Cities, Policy and Society, Space and Polity.

Notes

1 This is similar to what still happens today in many low-income countries. See, for example, the school feeding programmes implemented by WFP: info available at https://www.wfp.org/school-feeding.

3 By ‘quasi-public’ school we intend the so-called scuole paritarie which, despite being owned and managed by non-public entities, are formally part of the Italian public school system. See: https://www.miur.gov.it/sapere-la-differenza-tra-le-scuole-paritarie-e-le-scuole-private.

4 Different from other countries, such as the U.K., children are not allowed in Italy to bring a packed lunch to school and must use the school meal service when opting for full-day schooling. Such position has been confirmed by the Supreme Court of Cassation in 2019, with decision in 2050419.

6 The distinction between ‘central’ and ‘peripheral’ municipalities is based on the classification adopted within the National Policy for Inner Areas (Strategia Nazionale per le Aree Interne). The classification method is described in https://www.agenziacoesione.gov.it/strategia-nazionale-aree-interne/la-selezione-delle-aree/.

7 See the National Plan for Recovery and Resilience, Mission M4C1.1, Investment 1.2 (https://www.governo.it/sites/governo.it/files/PNRR.pdf).

8 As long as some of the indicators are basically similar, and to avoid redundancy, we selected the indicators with the strongest Pearson correlation for each sub-set of variables, i.e. indicators 2, 4, 7, 10, 14, 17, 19 and 20 in .

9 National Guidelines for School Catering (Rep. N°. 2/C.U.) (G.U. n. 134 of11 June 2010).

10 Circolare Minister of Education 2270 del 9.12.2019. for further information on the organization of the service and the responsibility of the head teachers and teachers see http://www.flpscuola.org/2020/10/19/mensa-scolastica-compiti-e-funzioni-del-personale-docente-e-collaboratore-scolastico-competenze-degli-enti-locali/.

11 Fund for organic school canteens established by paragraph 5a of Article 64 of Decree-Law No. 50 of 24 April 2017. The allocation of the Fund pursuant to Ministerial Decree of 22/02/2018 No.2026 can be found at https://www.politicheagricole.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/12466.

12 See the ‘Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza’, Mission M4C1.1, Investment 1.2, on the ‘extension of full-day schooling and school canteens’ [https://www.governo.it/sites/governo.it/files/PNRR.pdf; last accessed, 30 November 2022].

13 Judgement by the Corte di Cassazione of 9.12.2019, n. 20509.

14 Legislative Decree in 50 of 2016, reformed subsequently with Legislative Decree 56/2017 and again subject to numerous amendments during the COVID-19 emergency.

15 See the Decree of 11 October 2017 published in the Gazzetta Ufficiale of 6 November 2017, and the ‘social clause’ provided for in Article 50 of the Procurement Code. The ‘Minimum Environment Criteria’ (known as Criteri Ambientali Minimi in Italian, hereafter CAM) underwent revision: see Annex 1 of Ministerial Decree No. 65 of 10 March 2020 published in the Gazzetta Ufficiale No. 90 of 4 April 2020.

16 Consiglio di Stato; section III; Judgment No. 8773 of 14 October 2022.

17 Law No. 199 of 29 October 2016 came into force on 4 November 2016 and was published in the Gazzetta Ufficiale No. 257 of 3 November 2016.

18 Regional Law No. 7 of 25 July 2008 on ‘Norms for orienting and supporting the consumption of agricultural products of regional origin’.

19 Constitutional Court, judgement No. 292 of 3 December 2013.

References

- Andhov, M., Caranta, R., Janssen, W. A., & Martin-Ortega, O. (2022). Shaping sustainable public procurement laws in the European Union. The Greens/EFA in the European Parliament. Retrieved July 1, 2023, from https://extranet.greens-efa.eu/public/media/file/1/8361

- Andreotti, A., Mingione, E., & Pratschke, J. (2014). Female employment and the economic crisis: Social change in Northern and Southern Italy. In F. J. Moreno-Fuentes & P. Mari-Klose (Eds.), The Mediterranean welfare regime and the economic crisis (pp. 146–164). Routledge.

- Beccalli, B. (1994). The modern women's movement in Italy. New Left Review, I/204.

- Bonsmann, G., Storcksdieck, S., Kardakis, T., Wollgast, J., Nelson, M., & Caldeira, S. (2014). Mapping of National School Food Policies across the EU28 plus Norway and Switzerland. Joint Research Centre.

- Caldeira, S., Stefan Bonsmann Storcksdieck, S., & Bakogianni, I. (2017). Public procurement of food for health. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Cantillon, B. (2011). The paradox of the social investment state: Growth, employment and poverty in the Lisbon era. Journal of European Social Policy, 21(5), 432–449. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928711418856

- Del Boca, D., Locatelli, M., & Vuri, D. (2005). Child-care choices by working mothers: The case of Italy. Review of Economics of the Household, 3(4), 453–477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-005-4944-y

- Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education an introduction to the philosophy of education. MacMillan.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton University Press.

- European Commission. (2021). Provision of school meals across the EU. Publications Office of the European Union, Directorate-General for Employment Social Affair and Inclusion.

- European Institute for Gender Equality. (2022). Gender equality index (Online report).

- Ferrera, M., & Rhodes, M. (Eds.). (2000). Recasting European welfare states. Routledge.

- Levesque, C., Murray, G., Morgan, G. D., & Roby, N. (2020). Disruption and re-regulation in work and employment: From organisational to institutional experimentation. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 26(2), 135–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024258920919346

- Marra, M. (2012). The missing links of the European gender mainstreaming approach: Assessing work–family reconciliation policies in the Italian Mezzogiorno. European Journal of Women's Studies, 19(3), 349–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506812443631

- Merton, K. R. (1968). The Matthew effect in science. Science, 159(3810), 56–63. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.159.3810.56

- Osservatorio Appalti Verdi. (2018). Legambiente (Online Report).

- Pavolini, E., & Saraceno, C. (2022). 2021: A year of transition for social security and welfare policies in Italy? Contemporary Italian Politics, 14(2), 260–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/23248823.2022.2064129

- Ranci, C. (2015). The long-term evolution of the government–third sector partnership in Italy: Old wine in a new bottle? VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 26(6), 2311–2329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-015-9650-7

- Rete Commissione Mense Nazionale. (2019). V indagine sulle mense scolastiche (Online Report).

- Schmidt, V. A. (2008). Discursive institutionalism: The explanatory power of ideas and discourse. Annual Review of Political Science, 11(1), 303–326. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.060606.135342

- Swensson, L., Hunter, D., Schneider, S., & Tartanac, F. (2021). Public food procurement for sustainable food systems and healthy diets (volume 1 and 2). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, and Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul.

- World Health Organization. (2006). The world health report.

- World Health Organization. (2021). Action framework for developing and implementing public food procurement and service policies for a healthy diet.