Abstract

This photo essay is an exploration of how monuments, that try to give coherence to our shared past and identity, can be rethought through modern art. Specifically, it centres on an art festival in Balaguer, Spain, where an art installation titled MONUMENT by the MITO Collective was set up close to an existing monument of a 18th century Spanish conquistador. During the festival, the monument of the conquistador was vandalised and subsequently removed. The photo essay shows that instead of being static symbols, monuments can be lively spaces that encourage us to talk, question the usual stories told by history, and engage more actively with our collective memories. By presenting reactions to the MONUMENT installation, which featured slogans from various social movements, it suggests that monuments can be places where ongoing stories and conflicts are acknowledged. This shift in perspective invites us to keep rethinking how history can be negotiated in public places, making room for a wider range of voices and stories.

In the public spaces of our cities, monuments—made of stone and metal—act as markers of our history and collective memory, integrating it into the urban landscape. These pillars not only mark the physical coordinates of our environment but also aim to delineate and give coherence to the communities that erect them, with the risk of becoming elements that prevent change in the readings of our pasts (Nietzsche Citation1874).

On the 12th of October 2022, the monument dedicated to Gaspar de Portolá, in Balaguer (Spain), was vandalised by anti-racist activists, ( and ) then removed a few months later by the City Council to clean it up and put it back. Gaspar de Portolá was a military officer and explorer who held, among other positions, that of first Governor of the California’s between 1767 and 1770. The activists’ act of vandalism coincided with a significant date—the day of Hispanic Heritage, a day widely celebrated by Spanish institutions. By chance, it also coincided with the day we—MITO Collective—dismantled our artistic installation MONUMENT. MITO is a collective of artists and academic researchers that works in and on the myths that give meaning to our reality, including those represented by monuments. Whilst MITO Collective had nothing to do with the vandalisation of the Portolá monument, it seemed significant to us as part of our exploration of the collective meaning of monuments.

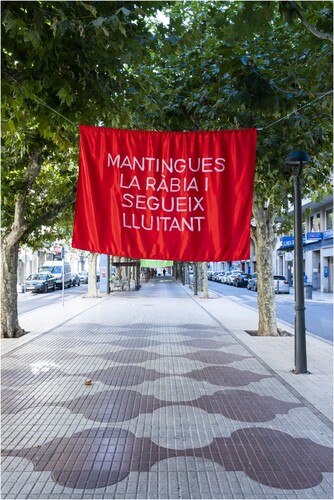

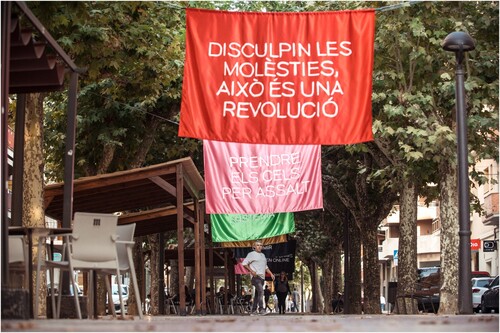

The installation we designed consisted of displaying 23 banners made of brightly coloured satin fabrics with handwritten slogans collected from movements fighting for the rights of submerged, annihilated and marginalised groups. We chose slogans from diverse groups, from the 19th century suffragettes to the Black Lives Matter movement, including slogans from various movements such as LGBTQ+, the feminist movement, the Civil Rights Movement, and revolutions such as the Arab Spring, the anti-austerity and outraged 15-M movement in Spain, the Spanish Civil War and May 68 (). When first creating our installation, we discussed the idea of a monument as a repository in the public space of collective memory. We decided the installation should be a series of banners with revolutionary slogans, but without citing a source and all translated into the same language, Catalan. There were several reasons for this. Translating them into the local language made them easier to understand, but at the same time represented the messages with the same level of importance. We also felt that this would help the viewers to create their own narratives about the slogans and installation. Our aim was that the installation would function as a kind of anti-monument or alternative monument in which each user could, as they passed through the installation, read the banners, and through the amalgam of messages question their ideas about the meaning of a monument.

Be realistic, demand the impossible

Stay angry and keep fighting

The installation occupied the central space of a boulevard as part of the urban art festival FORMA, that year dedicated to the theme of memory. The Boulevard is one of the city’s main gathering points and one of its main arteries, both for vehicles and pedestrians. The Gaspar de Portolà monument was located at one end of the boulevard. So, we proposed the installation of MONUMENT on this boulevard due to its centrality and relation to one of the most important monuments in Balaguer. We hoped that its juxtaposition with our MONUMENT would further trigger the viewer’s reflection on the meaning and significance of monuments.

I can’t breathe

Sorry for the inconvenience, this is a revolution

The act of vandalism on the monument to Gaspar de Portolá was linked with a series of protests and actions in the context of the Black Lives Matter movement, and other anti-racist and anti-colonialist struggles. We felt their action related to a series of questions that we wanted to raise with our installation: What is the role of monuments in contemporary society? How can monuments equitably reflect the diversity of memories and historical experiences of a community? Should monuments be permanent or evolve along with changes in social and historical perception?

Sorry for the inconvenience, this is a revolution

Storm the sky

System error

These critical questions on the value, meaning, and future of monuments in our societies suggest a continuous review of how and what we choose to commemorate in our shared spaces. Our research into monuments led us to consider that, to be functional, monuments have traditionally had three characteristics: partial, pure, and simple. Partial because they represent the perspective of the dominant group in a society or community. The Portola statue, for example, was partial by showing an 18th century Spanish conquistador, but with no recognition of the disturbed native cultures and people who suffered and resisted during that conquest. Pure because monuments typically represent only one dimension of the story being remembered. And simple in terms of carrying messages that are easy to grasp without too much complexity. For example, the Portola statue of the famous officer stands tall, sword in hand, looking heroic. This simplicity in design and message—celebrating bravery and leadership—makes it straightforward to understand what is being honoured, without the nuances of the officer's decision-making or the conquest's controversies. This conceptualisation opened a window to our thinking through new ways of understanding and presenting monuments, viewing them not as simple emblems of remembrance based on the partial, pure and simple, but rather as living complex entities that enter into dialogue with, confront, and transform the communities that host them. We wanted a monument that transcended the traditional commemorative function to become spaces of active reflection, interrogation, and potential change.

And it wasn't my fault, nor where I was, nor how

I was dressed.

Freedom by any means necessary

Figure 7: ‘Opinion divided in Balaguer on whether it is necessary to relocate the statue of Gaspar de Portolá’: Local newspaper debate about the return of the monument (Source: La Mañana 24 April 2023).

As we saw, monuments in public space generate debates, to which we wanted to contribute with our installation MONUMENT. By employing slogans used by oppressed and/or marginalised people in their struggles, the work sought to challenge dominant majorities and their monuments, creating a space for alternative and resisting voices. This approach diversifies the discourse, challenging the notion of a single dominant narrative about the past. Our installation played with the idea of monuments by disrupting any sense of conceptual purity. Mixing slogans from different movements and translating them into one language transformed them into an anonymised amalgam, questioning the notion of the single voice or simple message. The work opposed the traditional idea of a monument that seeks to commemorate the past or build a memory or displace a previous collective memory. Instead, it aspired to create new and diverse stories and perspectives that interact creatively with our own memories and ideas. Rather than consolidating the supremacy of the few, the installation encouraged free readings of the many, open to multiple forms of appropriation by the citizens of Balaguer, aimed at nourishing the experience and transformation of their perceptions as citizens (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1975; O’Sullivan Citation2006). A good example of this was the vandalisation of the monument to Gaspar de Portolá.

We hoped that this open and multiple approach turned the installation into a cultural force field able to challenge, interrogate, and reimagine dominant narratives, exploiting the capacity of art to provoke discussion and reflection in public space. Our aim was for our monument to be an active participant in the construction of fragmented memories, with the collective character of the multiple slogans suggesting a bottom-up movement, rather than an expression of dominant power relations, as in the Portolá monument. The dynamic of our MONUMENT and the subsequent actions around the Portolá monument showed how monuments can act as catalysts for dialogue and reflection within the community, offering a platform for alternative narratives and marginalised memories. At the same time the debate over whether or not to reinstall the Gaspar de Portolá statue for the first time since its erection opened up a public discussion about its suitability as a monument.

In conclusion, our installation MONUMENT sought to offer a new perspective on how monuments in our cities are not just physical structures but can be dynamic entities that have the power to shape, and be shaped by, the communities that host them. It was an invitation to rethink the role of monuments in contemporary urban life, not just as static reference points, but as living spaces of memory, conflict, and potential transformation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the FORMA Balaguer art festival for selecting the work and making its production and exhibition in the public space of Balaguer possible. Also to the photographer David del Val and the festival curator Irma Secanell for allowing the dissemination of their photographs. Also to the newspaper La Manyana for lending and allowing the diffusion of a page of their publication. Also to the editors of the section Scenes Sounds Action for their suggestions to improve this text.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Quim Bonastra

Quim Bonastra combines his tasks as a geographer at the University of Lleida (Spain) and as an artist within MITO Collective carrying out research at the intersection of art and geography. Email: [email protected]

Joan Deulofeu

Joan Deulofeu is a researcher that uses art, especially images, as his main tools to think about territories and identities. He’s also part of the artistic collective MITO. Email: [email protected]

References

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 1975. Kafka. Pour une littérature mineure. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit .

- Nietzsche, F. 1874. Unzeitgemässe Betrachtungen. Vom Nutzen und Nachtheil der Historie für das Leben. Leipzig: Verlag von E. W. Fritzsch .

- O’Sullivan, S. 2006. Art Encounters Deleuze and Guattari. Thought Beyond Representation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan .