Abstract

The election of Muyiwa Oki in 2022 as the youngest, the first worker and the first Black president of the Royal Institute of British Architects signified a break with a centuries-old status quo. The open and vocal campaign, led by a wide collective of early-career architects and built environment professionals, contrasted with the traditional behind-the-scenes machinations of an established architectural elite. This narrative aims to report the foundations of the campaign by plotting the chronological movements of the constituent activists both within and without the institute. We examine the mechanisms through which we were able to leverage our collective positions to tip the balance of power in favour of a youth-led movement founded on conditions of social and ecological justice. We reflect on changing voting rules, establishing governance positions, consolidating public perception, exerting pressures by grassroots campaigners, and finally challenging the status quo of the traditional seat of architectural power. We discuss the campaign's strengths in operating in a transparent and open manner. We present key learnings about the levers of power within established learned societies and professional institutes.

Introduction

In 2022, one of us—Muyiwa Oki—made history as the youngest ever president-elect of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), the only worker (meaning an employee without the power to fire or hire) to ever be in the position, as well as the first Black person to be elected to the post. The RIBA was founded in 1834, the oldest architectural institute in the world, carrying a well-established and respected international brand. Shaped in the age of Empire, the institution has retained many features of that period—opaque structures, perceptions of a London-centric boys’ club and an affinity to privilege. For an institution that has never officially acknowledged and reflected on its colonial past, a president-elect with Nigerian heritage carries with it a charged symbolism and hope for many (Gordon Citation2022). The concurrent appointment of the first Black RIBA CEO in 2022—Valerie Vaughan-Dick—means that, of the three most important governance positions, in September 2023 only the chair of the Board carries the associations of the ‘old guard’ (Carlson Citation2022; Marshall Citation2020). We, the Just Transition Lobby campaign group, coordinated Muyiwa’s election as a collective of early-career architects, activists and professionals, interested in reforming the institute from the inside out, with a particular focus on addressing the climate and biodiversity crisis (Jessel Citation2022a). We hope to initiate a process of solidarity with the early-career and marginalised communities of our sister institutes representing regulated or self-regulated professions, such as engineers, planners, surveyors, builders and others, so they may reclaim and reform their own professional bodies.

Reforming the professions

Professionalisation of the built environment disciplines since the 19th century has seen architects, engineers, planners and urban designers, formalise their status and establish professional bodies. At the core of professionalism sit trust and the exercise of judgement based on specialist knowledge (Duffy and Rabeneck Citation2013). Professional institutes’ role is to maintain the trust of the public and to regulate the standards its members must meet. It is in this context of self-regulation that professions hold a potential for rapid reform of knowledge and practice to serve the general public.

The RIBA is a charity in UK law and as such is governed by trustees (the Board) and led by a Chair. The President on the other hand leads the Council: a bigger, elected policy-making body with the power to appoint and recall trustees. The president is also a trustee, therefore bound by the legal dutiesFootnote1 and collective responsibility all trustees must observe as mandated by the Charity Commission. To succeed in delivering meaningful action on climate change, equity and workers’ rights, the majority of the Board (headed by the Chair) and Council (headed by the President) must agree with a buy-in by the executives who are the employees of the institute. Such reforms are currently a challenge considering the institutional inertia for which the RIBA has become known. Yet, professional institutes can mandate standards far exceeding government policy and legislation, holding an immense potential to accelerate the transition to a new more equitable economy. It is this challenge of leadership by professional institutes to engage with wider societal issues and lead transformative change that we want to address.

The just transition lobby

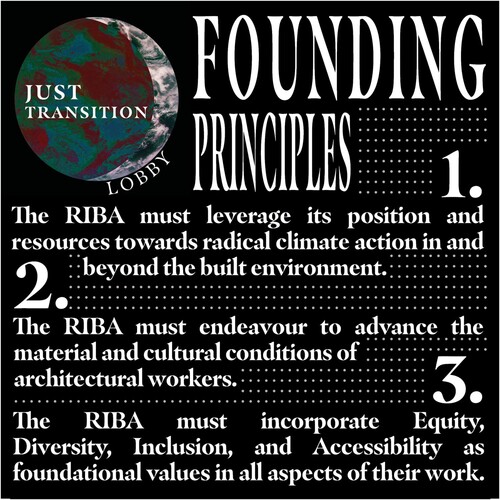

This article is focusing on the activist-led campaign of the 2022 RIBA presidential elections which culminated in the formalisation of the Just Transition Lobby campaign group—a cross-institute informal network of professionals who are interested in reforming our professional membership bodies. We believe that people committed to a progressive set of principles in leadership positions can lead to cultural and organisational change. We have three key principles focusing on radical climate action, advancing the material and cultural conditions of workers and incorporation of Equity, Diversity, Inclusion and Accessibility (EDIA) as foundational values in all professional standards (see ). We want to develop a strong lobby that can grow over time to influence all built environment institutes on the road to a just transition (Shtebunaev Citation2023).

Prepping the grounds

The RIBA has historically held a fraught relationship with its emerging professionals and it was from this group that the Just Transition Lobby campaign arose (The Just Transition Lobby Citation2023). We describe here the background and give credit to the people who enabled three key changes: the election of new and fresh voices to decision-making organs of the institute; securing senior leadership around which a movement can coalesce and changes to internal rules to remove existing barriers to inclusion.

A long-standing internal campaign by Albena Atanassova, Vinesh Pomal, Lily Ingleby, Marie Braithwaite and other past RIBA Council members paved the way by enfranchising students and associates in the vote for the RIBA president in 2020, as well as establishing the role of Vice President for Students and Associates in 2017. The ‘+25’ Council election campaign in 2017 led by Elsie Owusu (architect and a founding member of the Society of Black Architects) to elect a more diverse council resulted in the election of eight new Council members from historically underrepresented ethnic backgrounds, thus shifting the internal balance of power (Braidwood Citation2017). After the 2017 Council election, the post of RIBA Vice President for students was transformed into a collaborative one, shared between the newly elected Selasi Setufe and one of the authors, Simeon Shtebunaev. All these internal movements eroded the historical barriers faced by younger generations and laid the grounds to develop a movement which could influence the leadership of the institute.

This new positionality allowed for better opportunities to advocate for the role of ‘future architects’ within the institute. In the formal governance review of the RIBA Constitution chaired by Jane Duncan in 2018/19, the only two (out of seven) senior Vice-President (VP) posts to be retained were the ‘Membership’ and ‘Students and Associates’ posts. However, the VP Student and Associates post was not made a full Board member, and the trustee body lost an early-career representative. Since, the ‘Student and Associates’ VP post has developed as an observer seat on the RIBA Board, following lobbying by previous council members Victoria Adegoke, Lewis North, Stephen Drew and Maryam Al-Irhayim.

Importantly, the same governance review took away a restrictive condition requiring any future candidate for the post of RIBA president to have served for several years on the internal structures of the institute. This paved the way for architects from diverse backgrounds to contest the position and bring in new ideas to the institute. However, the poor 2020 elections turn-out by early-career architects and election of another perceived insider—Simon Allford—to the position of president were the catalyst for the organisation of our campaign for the 2022 presidential elections (Shtebunaev Citation2020).

Carving a space

Unlike other professional institutes, such as the Young Planners at the Royal Town Planning Institute and Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors’ MatRICS, the RIBA lacked a coordinated support and networking provision for emerging professionals. In 2018, the then RIBA Council members together with the Architecture Students Network (a non-RIBA student-led organisation supported by the Standing Conference of Heads of Schools of Architecture), held an open event in Birmingham to establish the business case for the creation of an early-career network (Shtebunaev Citation2018). The business case was accepted by the RIBA Council and the Future Architects network launched in December 2019 (RIBA Citation2019).

The network was to serve Student, Associates and recently qualified Chartered members of the institute, but the initiative immediately faced the challenge of the pandemic, which it navigated by scaling down activities and focusing on online outreach. As a direct result the RIBA gained a significant increase in student members. The network, however, was reduced from the original proposal for an entrepreneurial, regionally devolved and financially independent network, to a marketing campaign. Whereas much progress was achieved, a patronising discourse persisted and early-career professionals were often seen by the institute as solely ‘students’. This simplification erases the multitude of issues architecture graduates face in their years post-graduation as full-time employees, studying towards chartership. It also obfuscated the worrying cut-off of support once chartered status is acquired. The Future Architects initiative appeared to have lost its dedicated budget and full-time coordinator in 2021 as a result of an internal organisational restructure (Jessel Citation2022b).

The RIBA Future Architects network, a few years after inception, was at risk of becoming a branding exercise. A key lesson we learned was that in order to create organisational structures that can last and challenge the status quo, we needed to first make sure that the budget and leadership buy-in was in place. Following this experience, we then decided to aim for the top of the institute to ensure that early career architects have a sustainable and powerful voice within the RIBA.

Holding to account

For architecture students and graduates, however, RIBA Future Architects initiative was not delivering meaningful change quickly enough. Independently of the actions described above, the informal network Future Architects Front (FAF) (Raja Citation2021), (created in 2021 by one of the authors, Charlie Edmonds, together with Priti Mohandas), critiqued RIBA’s lack of transformative action. They highlighted how RIBA shied away from addressing issues such as underpaid hours, payments below the minimum wage and students struggling to find jobs due to job adverts asking for unrealistic years of experience.

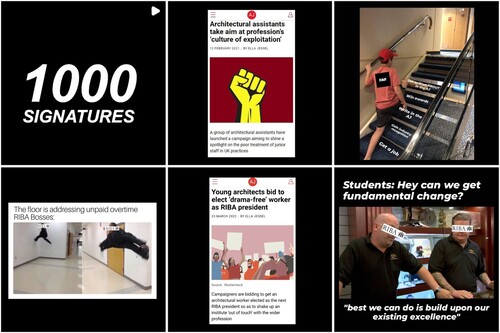

In January 2021 an open letter was written to the RIBA, signed by hundreds of early-career architects, including anonymous comments by young professionals highlighting these issues in the profession (Future Architects Front Citation2021). Future Architects Front (FAF) discussed the letter with the RIBA during a series of formal meetings, but unfortunately not all demands were taken forward. Issues that many early-career professionals cared about—radical climate action, tackling employment standards, and reforming the profession—were not addressed by the institute. FAF quickly established itself as a voice of the disenfranchised architectural worker—and one with teeth. Utilising Instagram’s potential for dynamic, responsive media (see ), the organisation’s wide-ranging critique was deployed via memes, data-analysis, long-form writing, and an emergent peer-to-peer learning in the form of open polls, discussion and informal sessions for students, graduates and workers alike.

Figure 2: Future architects front utilising social media communication strategies. Source: Future Architects Front public Instagram account, https://www.instagram.com/fa.front.

Getting together

Disillusioned by the often protective and exclusionary nature of the RIBA, an informal WhatsApp group was created where we could all discuss how we could accelerate the pace of change. We had all worked to change individual elements of the institute and realised that the traditional industry lobbying approach had failed, and that instead viable alternatives existed via the grassroots. For too long the professional body, which supposedly represented all architects, had been headed by company directors, those most divorced from the material interests of workers, driven by the interests of profit. We were also aware that the extractive colonial past of western-based built environment professions also had facilitated the development of the climate crisis we are currently facing. We identified the work of two organisations as critical to any future policies of a reformed institute: Architects Climate Action Network (ACAN) and the Union Section of Architectural Workers (SAW-UVW).

In a series of informal online meetings in the first weeks of March 2022 we agreed on the wording of a Call to Action to be published, as well as a process for selecting an alternative candidate for the RIBA presidential elections (Call to Action Citation2022). It was important to us that we led a transparent campaign and we were open to any nominations provided the person aligned with the principles in our collective manifesto and fitted the union definition of a ‘worker’—an individual without the power to fire or hire. Before launching the campaign widely in the media, we distributed an open letter with the initial Call to Action, which was signed by 54 individuals and six organisations. We put forward clear aspirations for a president who would represent workers, pursue ambitious climate action, respect early-career professionals and promote equality, equity, inclusion and diversity.

Capturing the collective imagination

The campaign to identify our nominee was launched officially on 23 March 2022, with a call in the Architects Journal and on social media for early-career architects to nominate themselves for the post (Jessel Citation2022a). In total nine people came forward, of which four could commit to the role: Hannah Deacon, Henry Pelly, Benjamin Champion and Muyiwa Oki. The independent hustings were hosted on the Architecture Social platform run by Stephen Drew (see ). The hustings were an opportunity for the candidates to express themselves, be asked questions and share their ideas about changing the profession for the better. Online polls distributed to husting attendees led to Muyiwa Oki being selected.

Figure 3: Architecture Social’s advert for Presidential Hustings. Source: Stephen Drew https://architecturesocial.com/elections/.

Former RIBA presidents Ben Derbyshire and Alan Jones publicly supported the hustings. Following a series of live broadcasts and online discussions, the architectural industry began to awaken to the prospects of a new face of leadership. Members and non-members alike became excited by the serious potential for change from within the RIBA. Once Muyiwa was selected, we facilitated the collection of 60 signatures from RIBA Chartered Members, which were required to formally nominate a candidate.

As well as achieving the nomination, the campaign represented hopeful possibilities for a new era of grassroots organising, aided by a digital media landscape. The ability to collectively leverage organisational bases underpinned by the themes of the labour movement, climate action and social justice enabled the campaign to threaten established well-networked candidates. The grassroots approach allowed organisers to address concerns over material conditions of unpaid overtime, low pay and climate anxiety. Whereas traditional candidates would return to tired stereotypes of ‘promoting value’ and ‘best-practice’ (Young Citation2022), the grassroots campaign promised a radical new vision of an institution governed by and inclusive of the majority of its worker-members.

In addition to the power of bottom-up organising we observed a generational advantage in this campaign—that of digital literacy. This was perhaps most evident when comparing the independent husting hosted by Architecture Social with the official RIBA hustings. Whereas the independent hustings were accessible, functional and programmed smoothly, the RIBA’s own hustings were plagued by a lack of technical literacy, unmuted microphones and digital exclusion. Online election processes present an ever-increasing opportunity for young organisers to fully leverage their digital fluency.

The campaign aimed to re-energise architects to be part of the RIBA. We received a lot of interest from eligible individuals asking how they could sign up to the RIBA and vote. Quickly, the RIBA introduced a highly contested modification to the official Regulations, demonstrating institutional momentum to maintain the status-quo:

But a rule change for 2022 means that members must have joined 10 or more days before the official notice of the election – published on 3 May. This means any architects or students who have joined RIBA since 23 April will be ineligible. (Gayne Citation2022)

The overall voting share for the presidential candidate was 12.4 per cent of the membership, revealing wider disengagement within the architectural profession. However, the impact of Muyiwa Oki winning the role was seen on the national and international stage, including an in-depth feature in the Guardian (Wainwright Citation2022).

The nitty-gritty of running a campaign

There were key practical lessons that emerged from our experience of running a successful election campaign aimed to reform a professional institute.

Find your tribe. The connection between all campaigners was our desire to reform the architectural profession. Throughout the years we had met, spoken, acted, reflected and been frustrated together. Keep note of these people and keep engaging with them, they are your biggest asset.

Know the rules! In the case of our campaign, many of us had been inside the institution and had intimate understanding of the changing rules. Having a person on the inside who knows the rules helps. This is important, as it speaks to the power of institutions to leverage structures and regulations in their favour. The strength of the campaign relied on the care and diligence of those campaigning, and how they maintained a close but critical perspective on the institution.

Organise flexibly, pool resources. We all volunteered as much time and resources to the campaign as we could. Our hustings were held virtually with the support of Architecture Social, in an open, multi-platform, easy-to-access format. This put the closed official RIBA hustings on Teams to shame, proving our point that collaboration and trust yields better results.

Maintain strong principles. We adjusted our pitch with every new conversation, but the core principles never changed. When Muyiwa was selected as our candidate, we were very clear that it was his campaign and his manifesto, but our principles had to be incorporated in it for our support to continue (Lowe Citation2022). This allowed him to take ownership of his own campaign and election whilst retaining our core social justice values.

You need the press! A big reason why our campaign was successful was that it broke into the Architects Journal and from there it was picked up by other news outlets. We circulated a press release the week before we went public and utilised existing relationships we had with journalists. We were also clear with the press that we didn’t want anything we put out to be behind a paywall (Jessel Citation2022a).

Activate your networks! Each one of our own networks of friends, classmates, colleagues and old employers is a sizeable minority, able to shift the tide of the profession. We messaged all key communities—the union, the climate network, large and small organisations, asking them to share the message.

Keep your friends close and your institute closer! Capturing the imagination of established ‘elders’ in the community without sacrificing our principles helped to reassure voters and build a larger coalition.

Be prepared, they play dirty! Be prepared for anything and always stick to the principles of fairness, transparency and openness. The attempt by RIBA to disenfranchise new members galvanised existing ones to our cause.

Next steps on the road towards a just transition

Muyiwa Oki’s name will be carved in the stone walls of the lobby of the RIBA Headquarters at 66 Portland Place. Whether it is an aberration or a transformative beginning, it is a tangible mark of a shift in the history of the 19th-century institution. In a world where we desperately need nimble and flexible organisations can the election of a single man at the top lead to a transformative change?

In 2023, we led another campaign after formalising the Just Transition Lobby: a broader coalition centred around three key principles of climate action, workers’ rights and equity. We secured seven seats out of 23 contested in the 2023 RIBA Council Elections. Oluwafunmbi Adeagbo, Greta Jonsson, Callum Duncan, Richard Timmins, Philippa Birch-Wood, Nenpin Dimka and Paul MacMahon were elected as Council members developing a strong voting minority block able to progress the principles in our manifesto (Spocchia Citation2023).

The Just Transition Lobby will continue to push for change in the make-up of decision-making chambers within the RIBA and beyond. We are optimistic that a reformed leadership of the built environment institutes holds the potential to advance built environment professions and support society’s just transition to a new economy respectful of climate and natural systems.

Acknowledgements

The campaign was primarily led and supported by a wide consortium of organisations and individuals including, in alphabetical order: Abigail Patel, ACAN (climate group), Albena Atanassova, Amy Francis-Smith, Architecture Social, Benjamin Champion, Charlie Edmonds, Chris Simmons, Dani Reed, Daniel Dehghani, Future Architects Front, Hannah Deacon, Henry Pelly, Jake Arnfield, Jason Boyle, Jordan Whitewood-Neal, Lewis North, Maryam Al-Irhayim, Muyiwa Oki, SAW-UVW (workers union), Scott McAulay, Selasi Setufe, Senaka Weeraman, Stephen Drew, Simeon Shtebunaev, Tamara Kahn, Victoria Adegoke and others. Muyiwa Oki was elected by 2967 RIBA members, we want to acknowledge their support.

Disclosure statement

We declare conflict of interest with elements of current RIBA governance by the virtue of this narrative detailing an election campaign for the Presidency and the Council of the institute. Some authors are members (different classes) of the RIBA at the time of submission. The campaign received no external funding, and it was entirely volunteer based.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Simeon Shtebunaev

Simeon Shtebunaev is an Associate member of the RIBA in 2023. They are a researcher at Social Life and a Visiting Lecturer in Urban Planning at Birmingham City University. Simeon is a PhD candidate in the Built Environment at Birmingham City University focusing on the role of teenagers in creating future city visions. They are a trustee of the Royal Town Planning Institute (2024–26). Email: [email protected]

Charlie Edmonds

Charlie Edmonds is a London-based designer and writer working across the fields of architecture, climate transition and political economy. He is a graduate of the University of Cambridge where he co-founded Future Architects Front with Priti Mohandas. Charlie is a systems designer at CIVIC SQUARE in Birmingham where he works to demonstrate the potential of grassroots retrofit and a devolved urban climate transition. Email: [email protected]

Maryam Al-Irhayim

Maryam Al-Irhayim is a Student Member of the RIBA in 2023. Maryam is Vice-President for students and associates at the RIBA and Part II Architectural Assistant at Fosters and Partners. She is a graduate of Manchester University. Email: [email protected]

Victoria Adegoke

Victoria Adegoke is a Chartered member of the RIBA in 2023. Victoria is on the validation board for education and teaches BA1 at Manchester School of Architecture. She works in practice in Stockport and is part of the practice and education committee in RIBA North West. Email: [email protected]

Muyiwa Oki

Muyiwa Oki is a Chartered member of the RIBA in 2023. He is an Architect in the Design and Digital team at construction consultancy Mace Group. He is the current President of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Email: [email protected]

Jordan Whitewood-Neal

Jordan Whitewood-Neal is an architectural researcher, designer and artist whose work addresses disability, domesticity, pedagogy and cultural infrastructure. He is currently co-leading a Design Think Tank at the London School of Architecture on Retrofitting as a process of civic reparation. Email: [email protected]

Stephen Drew

Stephen Drew is the Founder of the Architecture Social. He worked in the Architecture industry at EPR Architects for three years after completing a degree and diploma in Architecture at the University of Westminster and Manchester School of Architecture. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Also known as fiduciary duties check “The Essential Trustee Guide”, UK Government https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-essential-trustee-what-you-need-to-know-cc3/the-essential-trustee-what-you-need-to-know-what-you-need-to-do.

References

- Braidwood, E. 2017. “RIBA Council Elections a “huge success” in Improving Diversity.” The Architects’ Journal. https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/riba-council-elections-a-huge-success-in-improving-diversity.

- Call to Action. 2022. “Call to Action: The Next RIBA President needs to be Representative of its Members! Time for the first worker at the helm.” https://docs.google.com/document/d/1In0uMgOvrrd3U_rm8RcQz_zqfrji1q6nsoJVvGhQW_g/edit?usp = sharing.

- Carlson, C. 2022. “RIBA Names Valerie Vaughan-Dick as New Chief Executive.” Dezeen. https://www.dezeen.com/2022/11/02/riba-valerie-vaughan-dick-new-ceo/.

- Duffy, F., and A. Rabeneck. 2013. “Professionalism and Architects in the 21st Century .” Building Research & Information 41 (1): 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2013.724541.

- Future Architects Front. 2021. “An Open Letter to the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA).” Future Architects Front. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1RqqvgV-LBbWToAXmy136 ( 2PZ8D3fUj5R/view.

- Gayne, D. 2022. “New Rule Blocks New Members Voting in RIBA Elections.” Building Design. https://www.bdonline.co.uk/news/new-rule-blocks-new-members-voting-in-riba-elections/5117499.article.

- Gordon, A. 2022. “The Secret Architect: Muyiwa Oki’s Election Gives me Hope.” The Architects’ Journal. https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/opinion/the-secret-architect-what-muyiwa-okis-victory-says-about-the-riba.

- Ing, W. 2022. “RIBA Presidential Election: Rule Change Blocks New Members from Voting.” The Architects’ Journal. https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/riba-presidential-election-rule-change-blocks-new-members-from-voting.

- Jessel, E. 2022a. “Young Architects Bid to Elect ‘Drama-Free’ Worker as RIBA President.” The Architects’ Journal. https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/young-architects-bid-to-elect-drama-free-worker-as-riba-president.

- Jessel, E. 2022b. “RIBA Faces Backlash Over Plans for ‘Super Region’ Mergers.” The Architects’ Journal. https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/riba-faces-backlash-over-plans-for-super-region-mergers.

- The Just Transition Lobby. 2023. “The Just Transition Lobby, RIBA Council Elections 2023 Call to Action!” https://docs.google.com/document/d/16rduCZZwf_kkF1wn-xTQvisWq64Zmg3V7L_ncqwzpOs/edit.

- Lowe, T. 2022. “Interview | Muyiwa Oki: ‘There was this Opportunity to Actually do the Things That I want. and I Thought This Opportunity Might Not Come Again.” Building Design. https://www.bdonline.co.uk/briefing/interview-muyiwa-oki-there-was-this-opportunity-to-actually-do-the-things-that-i-want-and-i-thought-this-opportunity-might-not-come-again/5118004.article.

- Marshall, J. 2020. “Ex-RIBA president Jack Pringle to Take Charge of Board.” Building Design. https://www.bdonline.co.uk/news/ex-riba-president-jack-pringle-to-take-charge-of-board/5109262.article.

- Raja, A. 2021. “Future Architects Front is Campaigning to End Exploitation of U.K.’s architectural assistants.” The Architect’s Newspaper. https://www.archpaper.com/2021/05/future-architects-front-campaigns-end-exploitation-of-uk-architectural-assistants/.

- RIBA. 2019. “Introducing Future Architects.” RIBA News. https://www.architecture.com/knowledge-and-resources/knowledge-landing-page/introducing-future-architects.

- Shtebunaev, S. 2020. “Why Students Didn’t Vote in the RIBA Election – and What to do About it?” Building Design. https://www.bdonline.co.uk/briefing/why-students-didnt-vote-in-the-riba-election-and-what-to-do-about-it/5107510.article.

- Shtebunaev, S. 2023. “Why We Need Wholesale New Leadership for a ‘Just Transition’ in the Built Environment.” Building Design. https://www.bdonline.co.uk/opinion/why-we-need-wholesale-new-leadership-for-a-just-transition-in-the-built-environment/5123534.article.

- Shtebunaev, S. [@shtebunaev]. 2018. “The @RICSnews have @RICSMatrics, The @RTPIPlanners have @RTPIYPs, The @ICE_engineers have @ICE_GSNet, etc. Where is the @RIBA's #network for #students and #graduates? Come join us in #Birmingham and let's push for it's establishment internationally! #architecture [Tweet].” Twitter. https://twitter.com/shtebunaev/status/1043942879180345344?cxt = HHwWgMC-9Y-h6vwcAAAA.

- Spocchia. 2023. “Radical Reformers Elected to RIBA Council.” Architects Journal. https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/radical-reformers-elected-to-riba-council.

- Wainwright, O. 2022, October 19. “‘Our Time has Come’ – Muyiwa Oki, First Black President of RIBA, reveals his shakeup plans.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/oct/12/muyiwa-oki-black-president-riba-.

- Young, E. 2022b, June 20. “The 2022 RIBA Presidential Candidates Set out Their Stalls.” RIBA Journal. https://www.ribaj.com/culture/riba-president-candidates-2022-jo-bacon-muyiwa-oki-sumita-singha.