ABSTRACT

This paper argues that the pairings of citizenship and immigration, territory and mobility – pairings often considered distinct to or even opposite of one another – are critically interconnected. These links are particularly visible in the experiences of Chinese-born children of U.S.-born fathers. These children secured jus sanguinis birthright citizenship from their fathers, fathers who secured jus soli birthright citizenship under the Wong Kim Ark decision. They were ‘immigrant citizens’ who were allowed to immigrate to the United States only because they were U.S. citizens. Wong Kim Ark’s children, along with other Chinese Americans under exclusion, upend the assumed teleology of immigration preceding citizenship and the association of citizenship with territorial presence. Although they were targeted by U.S. immigration authorities, Chinese immigrant citizens fought for their right to migrate between China and the United States. In the process, they exposed some of the ways in which presumed distinctions between citizenship and alienage were blurred during Chinese exclusion, as well as the ways in which citizenship is legally constructed.

Introduction

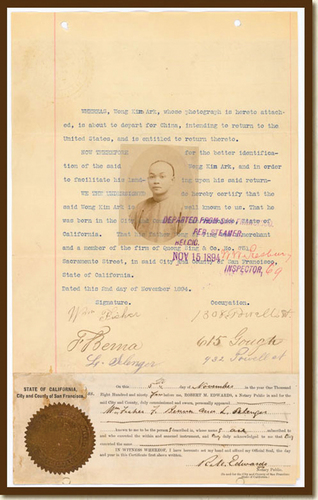

Less than two weeks before his departure from the United States in Citation1894, Wong Kim Ark obtained a notarized certificate with a photographic image of his face and upper body fixed in the center (). Across the certificate and overlapping the edges of the photograph, blue type attested that Wong Kim Ark was the individual identified in the photograph, that he was born in the City and County of San Francisco, and that he intended and was entitled to return to the United States. He was depicted with an open and calm expression looking slightly to the left of the viewer. This photographic profile echoed the gold-embossed seal of the State of California on the lower left edge of the document which depicted Roman goddess of wisdom Minerva looking westward, the direction that Wong traveled. The sepia image was printed in an oval, suggesting that the portrait might have been framed as a memento if it had not been used as part of an affidavit. The document was signed by three white witnesses on November 2, notarized on November 5, and stamped by a customs inspector on November 15, showing that Wong had departed from San Francisco on board the SS Belgic. Return certificates were introduced with the 1882 Chinese restriction law, which barred most Chinese immigration but included exemptions for U.S. citizens and other groups such as merchants and students (Lee Citation2003, 103–06; Lew-Williams Citation2018, 51–62). Even though the law didn’t require it, officials in San Francisco required two white witnesses to attest to the identity and nativity of Chinese American travelers (Salyer Citation1995, 65). Wong may have secured a third witness because on a previous trip to China an inspector had raised doubts about one of his witnesses (McKenzie Citation2017, 120–21). The typed text and the photographic image are clear. However, Wong’s return certificate is only fully legible in the context of birthright citizenship under Chinese exclusion, and the ways in which intersecting regimes of citizenship addressed questions of territory and mobility.

Figure 1. Departure statement of Wong Kim Ark, November 5, 1894, in the matter of Wong Kim Ark for a writ of habeas corpus, U.S. District Court for the Southern (San Francisco) division of the Northern District of California, Records of District Courts of the United States, 1865–2009 (Record Group 21), NAID: 2641490, National Archives at San Francisco, San Bruno, California.

According to immigration case files, when Wong Kim Ark first traveled to China in 1889, he married and his wife conceived a son who was named Wong Yoke Fun. On an 1894 trip as well as subsequent trips in 1905 and 1914, Wong Kim Ark testified that he fathered three additional sons: Wong Yook Thue, Wong Yook Sue, and Wong Yook Jim (Wong Yoke Fun; Wong Yook Thue; Wong Yook Jim; Berger Citation2016, 1228). The four children whom Wong Kim Ark claimed as his sons were born physically outside the United States, in China, to a U.S.-born father. Along with other territorially Chinese-born children of U.S.-born fathers, they secured jus sanguinis citizenship (through descent or ‘blood’) at birth from their fathers, fathers who secured jus soli citizenship (birth in a given territory or ‘soil’) under the Fourteenth Amendment’s extension of citizenship to persons born in the United States. In fact, Wong Kim Ark secured these rights for himself and, by extension, other U.S.-born Chinese in a landmark case, United States v. Wong Kim Ark (Citation1898).

In this article, I develop three related claims. First, that the experiences of Wong Kim Ark’s children disrupt the conventional opposition between citizen and immigrant, as well as the assumed progression from immigrant to citizen. Like other Americans who secured jus sanguinis birthright U.S. citizenship upon their births outside U.S. territory then immigrated to the United States, they were both citizens and immigrants. They were citizens before they were immigrants. And, as Chinese Americans, they were allowed to be immigrants (to enter and reside in U.S. territory) only because they were U.S. citizens. For Wong Kim Ark’s children and similarly situated Chinese Americans, citizenship and immigration status were not separate statuses. Such individuals can be considered ‘immigrant citizens’. Second, immigrant citizens dislocate the presumed connection between citizenship and territorial presence, as well as the assumption that citizenship is primarily valuable in allowing settlement and rights within a given territory. Wong Kim Ark’s children were U.S. citizens outside of and prior to their presence in U.S. territory. Like their father and other Chinese Americans, they valued U.S. citizenship because it allowed them mobility as well as U.S. residence, especially the ability to move between the United States and China. However, individuals who were highly mobile were grandfathered out of immigrant citizenship. Although U.S. citizen fathers transmitted jus sanguinis birthright citizenship to their children, the fathers were required to have resided in the United States (Act of 26 March 1790, 1 Stat. 103; Weedin v. Chin Bow Citation1927). In this way, immigrant citizens dislocated the connection between citizenship and territoriality rather than making a complete break. Third, immigrant citizenship was strongly opposed by nativists, including anti-Chinese activists within the Immigration Bureau. Although immigrant citizenship was not racially based, in the context of Chinese exclusion, it was one of the most important means for Chinese to immigrate to the United States as well as to travel between the United States and China. Other immigrants could fall out of legal status because of their actions or redefinitions of their status in regulations. In contrast, once recognized, U.S. citizenship was generally a permanent status. As a result, immigration authorities were particularly concerned about immigrant citizenship and attempted to the prevent the entry of immigrant citizens of Chinese descent through stringent implementation of the exclusion laws.

As immigrant citizens show, citizenship is a legally constructed status fashioned through conflicting political imperatives and inconsistent administrative procedures informed by both racially inclusionary and exclusionary aims. Citizenship status is often viewed as a binary: under current immigration law, people are either citizens or noncitizens, also legally defined as immigrants. They cannot be simultaneously both. However, in practice, these legal distinctions are not always clear cut. During Chinese exclusion, U.S. authorities and Chinese immigrants blurred these boundaries. Supporters of Chinese exclusion negotiated conflicting imperatives: they wanted to ensure that most U.S. citizens who fathered children overseas could extend U.S. citizenship, immigration and territorial residency rights to their children while excluding similarly situated fathers of Chinese descent. In cases before U.S. courts, in immigration regulations, and in immigration investigations, ethnic Chinese pressed on these tensions to secure citizenship, immigration and residency rights. At the same time, U.S. authorities pushed back, using rhetoric, regulations and strict immigration investigations to limit access to immigrant citizenship and the accompanying right to migration and mobility. Historians of Chinese American citizenship have focused mostly on the contestation and denial of Chinese American claims to citizenship within the United States. Following scholars of citizenship who have long recognized jus sanguinis citizenship and the transmission of citizenship to children born outside their parent’s place of nationality, this article explores the complex history and significance of Chinese American immigrant citizens.

United States v. Wong Kim Ark

Although Wong Kim Ark’s certificate was on file with the Customs Office, when he returned to San Francisco in August 1895 after his visit to China, he was denied entry. U.S. officials had decided upon Wong as a case to challenge Chinese birthright citizenship. During the exclusion era, many cases focused on whether a Chinese arrival had adequately proven their exemption from exclusion law, including their status as a merchant, student, traveler or U.S. citizen. Wong’s case was different. The customs collector who detained him acknowledged that Wong had the necessary certification of his birth in the United States and that his ‘papers were all straight’ (Salyer Citation2005, 51, 66). However, the collector claimed that, even if Wong was born in the United States, this did not make him a U.S. citizen. Wong argued that he was a U.S. citizen under the Fourteenth Amendment (CitationU.S. Const. amend. XIV 1868). He prevailed in the lower courts, but the U.S. government appealed his case to the Supreme Court. In this way, Wong’s efforts to return home became the test case of birthright citizenship.

At the U.S. Supreme Court, as Justice Horace Gray wrote for the majority, ‘the question presented by the record is whether a child born in the United States, of parents of Chinese descent, who, at the time of his birth, are subjects of the Emperor of China, but have a permanent domicile and residence in the United States … becomes at the time of his birth a citizen of the United States by virtue of the first clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution, All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside’ (Wong Kim Ark, 653). The question was presented as a matter of territorial presence; however, it was raised by Wong Kim Ark’s territorial absence and because of his mobility, his traveling between the United States and China.

As is well-known, the Supreme Court ruled that Wong Kim Ark was a U.S. citizen. The phrase ‘all persons born’ – and by extension birthright citizenship – was ‘general, not to say universal, restricted only by place and jurisdiction, and not by color or race’ (Wong Kim Ark, 693). Place trumped race. Chief Justice Melville Fuller dissented from this claim, arguing that ‘the true bond which connects the child with the body politic is not the matter of an inanimate piece of land, but the moral relations of his parentage’ (Wong Kim Ark, 708). He was in the minority. In terms of birthright citizenship, it did not matter if nativists believed that Chinese were racially alien to the United States; the Court ruled that they were not territorially alien. They were therefore citizens. Citizenship was more secure than other forms of immigration status, but it was not a fully secure status (Lew-Williams Citation2023). Wong Kim Ark was successful in obtaining his own jus soli birthright citizenship; however, only three of his four claimed children were able to acquire jus sanguinis U.S. citizenship and admission to the United States. When the eldest, Wong Yoke Fun, arrived at Angel Island in October Citation1910, his answers to the questions asked in the interrogation did not match those of his father. After two months in detention and an appeal, immigration authorities determined that his claim to citizenship was fraudulent and that he was a paper son. Wong Yoke Fun was denied admission (Wong Yoke Fun). At the same time, one of Wong Kim Ark’s legally recognized children later claimed to be a paper son. In 1960, Wong Hang Juen acknowledged that he had entered the United States 36 years earlier with the paper name and identity of Wong Yook Sue (Wong Hang Juen; Frost Citation2021, 73).

Immigrant citizen status

Many scholars have considered the central importance of citizenship to Chinese Americans and Asian Americans (Lowe Citation1996; Ong Citation1999; Volpp Citation2007; Ngai Citation2004; Park Citation2004; Salyer Citation2004; Perez Citation2008; Jun Citation2011). Historians and legal scholars have focused on efforts to secure naturalized U.S. citizenship (Haney López Citation2006; Lew-Williams Citation2023; Salyer Citation2004) as well as Wong Kim Ark’s fight to secure jus soli birthright U.S. citizenship (Berger Citation2016; Lee Citation2002; Ngai Citation2007; Salyer Citation2005; Phan Citation2006; Nackenoff and Novkov Citation2021). However, fewer scholars have addressed the ways that Wong Kim Ark’s jus soli birthright citizenship extended jus sanguinis citizenship to his sons (Collins Citation2014; Frost Citation2021; McKenzie Citation2017). They have not explored the critical importance of U.S. citizens born outside the United States, or the ways that such immigrant citizens disrupt conventional understandings of citizenship and immigration.

The opposition between citizen and immigrant, citizen and alien has been central to the ways that Asians have been viewed in the United States. As scholar Lisa Lowe notes in Immigrant Acts, during ‘the last century and a half, the American citizen has been defined over against the Asian immigrant, legally, economically, and culturally’ (Citation1996, 4). Lucy Salyer notes that Asians have been ‘in American rhetoric, anti-citizens, embodying values and characteristics antithetical to those of the ideal American citizen’ (Citation2004, 856). ‘Through a halting process of exclusion’, Beth Lew-Williams has argued, ‘the Chinese migrant became the quintessential alien in America by the turn of the twentieth century’ (Citation2018, 8). Mae Ngai’s analysis of ‘impossible subjects’ explores how Asian Americans disrupt ‘the telos of immigrant settlement, assimilation, and citizenship’ (5). Ngai develops the category of ‘alien citizens’ to describe ‘Asian Americans and Mexican Americans born in the United States with formal U.S. citizenship but who remained alien in the eyes of the nation’ (8). Although they possessed birthright U.S. citizenship, Asian Americans and Mexican Americans were not recognized by white Americans as U.S. citizens.

However, the telos of ‘immigrant settlement, assimilation, and citizenship’ can be disrupted in a different direction. Instead of Ngai’s formulation of ‘alien citizens’, Wong Kim Ark’s children were immigrant citizens. While Ngai’s formulation focuses substantially on individuals ‘born in the United States’ and seeking rights within America, immigrant citizens were born outside the United States and sought the right to migrate. They were citizens before they were immigrants, reversing the traditionally assumed passage from immigration to citizenship. And they were allowed to be immigrants (to enter and reside in U.S. territory) only because they were U.S. citizens. As demonstrated in the efforts to limit Wong Kim Ark’s U.S. citizenship, nativists believed that Chinese were socially and culturally alien, whether they were citizens or not, and whether they lived territorially within or outside the United States. However, for Wong Kim Ark’s children, citizenship status and immigration rights were not contradictory but complementary.

In popular understanding and in immigration law, immigrants are aliens. This distinction is enacted in current immigration law where immigrants are defined as noncitizens or aliens (Immigration and Nationality Act, 8 U.S.C. § Citation1101(a)(15)). In common speech, however, an immigrant is ‘a person who comes to settle permanently in another country or region’ (Oxford English Dictionary, s.v., Citation2023). Wong Kim Ark’s children were both immigrants and citizens. They were immigrants at the same time that they were citizens, mixing these categories that are assumed to exist in opposition to one another.

In addition, Wong Kim Ark’s children disrupt the common assumption that individuals move from immigration to citizenship status. And they do so in ways that are different from how this has previously been considered in Asian American history. Legal scholars such as Ian Haney López have shown how this trajectory was disrupted for Asian immigrants who attempted to naturalize as U.S. citizens. With limited exceptions, most Asian immigrants were not able to become U.S. citizens until the mid-20th century (Haney López Citation2006; Lew-Williams Citation2023; Motomura Citation2007; Salyer Citation2004; Volpp Citation2001).

The U.S. Constitution gives Congress the power to regulate naturalization and it requires that the U.S. President be ‘natural born’ (U.S. Const. art. I, § 8; art. II, § 1). However, it did not initially define the qualifications for natural-born citizens. In 1790, Congress passed a statute ‘to establish an uniform Rule of Naturalization’. The law is widely known for racially limiting naturalization to free whites; however, it also included temporal and territorial restrictions. The law limited the acquisition of U.S. citizenship to ‘any alien, being a free white person, who shall have resided within the limits and under the jurisdiction of the United States for the term of two years’ (Act of 26 March 1790, 1 Stat. 103; Haney López Citation2006).

Chinese and other Asian immigrants were excluded from naturalized citizenship in the 1790 Naturalization Act and all nineteenth-century revisions of naturalization law. Lew-Williams explores the relatively small but significant number of Chinese immigrants who became U.S. citizens despite laws preventing their naturalization. In 1900, she has shown that the U.S. Census listed 6.7% of the Chinese population in the United States as naturalized citizens. This was in addition to 20% of the U.S. Chinese population who were jus soli or jus sanguinis birthright citizens. Lew-Williams notes that naturalized citizens’ precarious legal status meant that they, like native-born Chinese Americans, ‘blurred the line between citizen and alien’ (Citation2023, 527).

After the Civil War, as members of Congress sought to ensure birthright citizenship was extended to formerly enslaved Black Americans, they introduced the Civil Rights Act of 1866 (Act of 9 April 1866, 14 Stat. 27, ch. 31, § 1) and the Fourteenth Amendment (U.S. Const. amend. XIV 1868). Although congressional debates about the amendment focused on Black American citizenship, they also addressed whether it extended U.S. citizenship to Chinese born in the United States. ‘Is the child of the Chinese immigrant in California a citizen?’ Senator Edgar Cowan asked. ‘If so, what rights have they? Have they any more rights than a sojourner?’ Most citizenship rights are understood to be secured within the territory of one’s citizenship; however, debates about birthright citizenship for ethnic Chinese addressed immigration rights. Cowan continued ‘is it proposed that the people of California are to remain quiescent while they are overrun by a flood of immigration of the Mongol race?’ (Cong. Globe 39th Cong. 1st sess. 2890–91; Wyatt Citation2015, 6). In this question, Cowan recognized immigration was a fundamental citizenship right.

With expansions on access to citizenship, anti-Chinese legislators decided to reiterate the bar on Chinese naturalization in 1882 (Cong. Rec. Appendix 47th Cong. 1st sess., 127). The law clearly and completely excluded Chinese from naturalized citizenship stating that ‘hereafter no state court or court of the United States shall admit Chinese to citizenship’ (Act of 6 May 1882, 22 Stat. 58, ch. 126, § 14.) This ban on Asian naturalization was consolidated in 1922 and 1923, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Japanese immigrants and Asian Indian immigrants were not entitled to naturalize as U.S. citizens (Ozawa v. United States; United States v. Thind). Chinese immigrants secured naturalization rights with the end of Chinese exclusion in 1943 (Act of 17 December 1943, 57 Stat. 600); most Asian immigrants were prevented by U.S. law from becoming U.S. citizens until 1952 (Act of 27 June 1952, 66 Stat. 163).

Between 1882 and 1943, commonly considered the Chinese exclusion era, ethnic Chinese could legally secure U.S. citizenship only through birth in the United States to Chinese national fathers (jus soli) or through birth outside the United States via U.S. citizen fathers (jus sanguinis). Married U.S. citizen mothers were able to transmit their citizenship to foreign-born children starting in 1934, although gendered differences in jus sanguinis citizenship continued (Collins Citation2014, 2155–57). Enterprising men claimed to have fathered children during visits to their wives in China, shared this information with U.S. immigration authorities, and thus created identities for paper sons to use in the future. U.S. citizenship status became the most reliable way around Chinese exclusion laws, fostering an extensive trade in paper identities (Daniels Citation2004, 24–25; Ngai Citation2004, 204). Wong Hang Juen, who claimed to be Wong Kim Ark’s youngest son Wong Yook Sue, was one of these paper sons (Wong Hang Juen Citation1924-1966).

The legal status of children born outside the territory of the United States had long been countenanced in American law. In addition to naturalization restrictions, the 1790 naturalization law also addressed the question of jus sanguinis birthright citizenship and territoriality by defining the children of U.S. citizens as natural-born citizens even if they were ‘born beyond sea, or out of the limits of the United States’ (Act of 26 March 1790, 1 Stat. 103).

The delineation of jus sanguinis birthright citizenship in the 1790 law is statutory. However, it also drew on longstanding understandings of the transmission of citizenship status from parent to child as part of natural law and common law. In congressional discussions of the statute, there were only two brief comments about the birthright citizenship provisions. ‘The case of children of American parents born abroad ought to be provided for’, Representative Aedanus Burke noted, ‘as was done in the case of English parents’ under William III. Representative Thomas Hartley noted that he would present a clause to this effect, without further discussion (Annals of First Congress, 1160, 1164; Weedin v. Chin Bow (Citation1927), 661). The birthright provisions and restrictions were accepted without debate.

Jus sanguinis immigrant citizenship existed before the Wong Kim Ark decision, but became increasingly important for ethnic Chinese after the imposition of exclusion and the recognition of birthright citizenship for Wong Kim Ark in Citation1898. The status of immigrant citizens was not racially defined. However, Chinese practices of transnational marriage and migration combined with U.S. restrictions on Chinese migration meant that ethnic Chinese were the most significant and consistent group to use this immigrant citizenship (McKeown Citation1999; Hsu Citation2000). Between 1905 and 1940, roughly 100,000 jus soli and jus sanguinis birthright citizens used their citizenship status to return to or enter the United States; about half of all ethnic Chinese admitted by the immigration authorities. The numbers of citizens increased over time from one-fifth of all ethnic Chinese entrants in 1905 to three quarters in 1940 (Lee Citation2003, 101–02). Starting in 1920, jus sanguinis citizen children started to outnumber returning jus soli birthright citizens (Hsu Citation2000, 79–80). Throughout this time, Chinese Americans fought to ensure that they were recognized as U.S. citizens whether they were born within U.S. territory or outside the United States to U.S. citizen fathers. They were frequently successful.

Immigrant citizenship and mobility

Immigrant citizens not only disrupt the opposition between immigrants and citizens, they also dislocate the presumed connection between citizenship and territorial presence. Unlike state citizenship, which requires territorial presence, national citizenship does not. In a decision preceding the U.S. Supreme Court decision, Judge William Morrow ruled that Wong Kim Ark was a citizen of the United States, stating that ‘A man must reside within a State to make him a citizen of it, but it is only necessary that he should be born or naturalized in the United States to be a citizen of the Union’ (cited in ‘Native-Born Chinese’).

Lisa Lowe has written that ‘citizens inhabit the political space of the nation, a space that is, at once, juridically legislated, territorially situated, and culturally embodied’ (Citation1996, 2). However, immigrant citizens were territorially situated outside the United States. In contrast to assumptions about citizens residing within the territorial nation of their citizenship, they acquired U.S. citizenship before and without U.S. residence. Although immigrant citizens were territorially outside the nation, they were – as birthright citizens – legal insiders.Footnote1

Immigrant citizens also challenge the assumption that immigrants move from noncitizen to citizenship status to secure more rights within the territorial United States. Birthright citizenship worked in various ways to enable mobility. Jus soli birthright citizenship – provided by the Fourteenth Amendment and confirmed in Wong Kim Ark – is grounded in birth within U.S. territory, but it provided Chinese Americans with mobility to move between the United States and China. Similarly, jus sanguinis immigrant citizens born outside the United States used their citizenship not only to be physically present in the United States, but also to become transnationally mobile, moving between China and the United States. These transnational migration and citizenship practices disrupt the assumed association of citizenship with settlement and immigration with sojourning. They are early forms of ‘flexible citizenship’, as anthropologist Aihwa Ong has explored in her study of contemporary Chinese diasporic professionals under current forms of globalization (Ong Citation1999).

Although freedom of movement is a key component of citizenship rights and an important reason that nativists opposed Chinese birthright citizenship, it has generally been neglected in U.S. analyses of citizenship. ‘Within the hegemonic liberal historiography of American citizenship’, legal scholar Kunal Parker notes, ‘the narrative of citizenship is confidently plotted from the “inside”. Thus, citizenship acquires meaning principally in terms of the experiences of individuals already inside a territorial community organized on the basis of citizenship, whether these happen to be those to whom “full membership” was historically available (propertied white males) or those from whom “full membership” was historically withheld (indigent white males, women, and racial minorities)’ (Parker Citation2001, 584).

Scholars of African American history have extensively explored the relationships between citizenship and freedom of movement, considering restrictions on the mobility of enslaved people and escaped slaves, enslaved people in free states, free Blacks, and Black immigrants (Litwack Citation1961; Wilkerson Citation2010; Putnam Citation2013; Audain Citation2014; Teague Citation2015; Stordeur Pryor Citation2016). Legal historian Martha Jones has explored the ways that antebellum Black activists worked to secure citizenship rights, concerned not only about the franchise, education, and military service but also because they feared forced removal from individual states or from the United States (Jones Citation2018, 4, 35–49). As Devon Carbado notes, the Dred Scott decision was centrally concerned with the possibility that Black citizenship would guarantee freedom of movement (Citation2005, 654–5). Taney’s ruling expressed concern that Blacks recognized as citizens in any state would have ‘the right to enter every other State wherever they pleased, singly or in companies, without pass or passport, and without obstruction, to sojourn there as long as they pleased’ (cited in Carbado Citation2005, 654). Dred Scott was overturned by the Fourteenth Amendment, which recognized both birthright citizenship and freedom of movement.

Kunal Parker is precisely right about the ‘inside’ narratives of citizenship and how they overlook the ways that citizenship is both constituted by territory and conveys rights of territorial mobility. At the same time, however, he reinscribes the opposition between insider and outsider. Parker critiques liberal histories for focusing on the citizenship of territorial insiders rather than exploring the ways that citizenship works to exclude those territorially outside. However, citizens are not always territorially inside in the nation and aliens always outside. Immigrant citizens traverse the borders between territorial outsider and insider.

Mae Ngai discusses how ‘alien citizenship’ involves ‘the nullification of the rights of citizenship – from the right to be territorially present to the range of civil rights and liberties – without formal revocation of citizenship’ (Ngai Citation2007, 2522). Territorial presence in the country of one’s citizenship is a foundational citizenship right. As Leti Volpp notes, it is so fundamental that it is often presumed, even though ‘U.S. law is silent as to the internationally guaranteed right of return, or a person’s right to return to his own country’ (Volpp Citation2007, 2579–80; Edwards v. California (Citation1941); Saenz v. Roe (Citation1999); Kahn Citation2013, 60–71). Following from presence, most discussions of citizenship focus on civil rights within a given territory. U.S. citizenship provided rights to Asian Americans, such as the right to own property at a time when many states barred Asian noncitizens from such purchases (Salyer Citation2004, 856; Haney López Citation2006, 130–31).

As scholars have explored, U.S. citizens of Chinese descent, including Wong Kim Ark and his children, fought for the right to be territorially present in the United States (Berger Citation2016; Lee Citation2002; Salyer Citation2005; Ngai Citation2007; Phan Citation2006; Nackenoff and Novkov Citation2021; Frost Citation2021; McKenzie Citation2017). However, they also fought for citizenship rights of territorial absence and mobility, the right not to be required to stay in the United States. Like other Chinese Americans, Wong Kim Ark and his family used this mobility extensively. Wong Kim Ark traveled between the United States and China six times between 1877 and 1931. With the exception of his oldest claimed son whose application was denied, his admitted sons also traveled between China and the United States. Wong Kim Ark’s return certificate certified his California birthplace ‘in order to facilitate his landing upon his said return’, linking his birth within U.S. territory to freedom of movement (Wong Kim Ark). Later applications for investigation of his status as a U.S. citizen prior to his departure show his ongoing migration, as well as immigration authorities’ increasing control over and regularization of the migration process.

In congressional debates about the Fourteenth Amendment, in the Wong Kim Ark decision, and in the Immigration Bureau’s responses to this decision, critics of Chinese birthright citizenship expressed concerns about the migration rights that such citizenship afforded. In contrast to understandings of citizenship as the acquisition and use of rights within a given territory, these experiences illustrate the importance of the citizenship right to mobility (Ong Citation1999; Torpey Citation2000). The San Francisco Chronicle recognized this in its headline on an early court decision in the Wong Kim Ark case: ‘The Native-Born Chinese are Legally Adjudged to be Citizens; They Have a Right to Land Here Again after Taking a Trip to China or Elsewhere’ (1896, 12).

Although immigrant citizens sought and secured rights to territorial absence and mobility, they could not secure recognition as U.S. citizens if their fathers were territorially absent or highly mobile. The transmission of jus sanguinis birthright U.S. citizenship was limited by territorial presence. Since 1790, U.S. law stated that children born overseas were natural-born citizens ‘Provided, That the right of citizenship shall not descend to persons whose fathers have never been resident in the United States’ (Act of 26 March 1790, 1 Stat. 103). Through subsequent changes in citizenship law, the right to transmit citizenship to children born overseas and the restrictions on this right generally remained (Weedin v. Chin Bow (Citation1927), 661–5). Married U.S. citizen fathers could transmit their citizenship status to children born overseas; however, this was good for just one generation.

The U.S. Supreme Court affirmed this restriction in 1927 in Weedin v. Chin Bow. Chin Bow was the grandchild of a jus soli birthright U.S. citizen; however, his U.S. citizen father had not moved to the United States until 1922, after Chin was born in China. In 1925, ten-year-old Chin applied for entry to the United States in Seattle, but was denied because his father’s lack of residency in the United States prior to his birth meant that Chin was not a U.S. citizen (Weedin v. Chin Bow (Citation1927)). Interpreting the statutory language and citing Wong Kim Ark, Weedin supported jus sanguinis citizenship transmission only if the father was resident in the United States (Weedin v. Chin Bow (Citation1927)).

Ethnic Chinese were not the only group affected by the requirement that U.S. citizen fathers be U.S. residents to transmit their citizenship. Highly mobile individuals with no territorial home were also denied immigrant citizenship. If they were not Asian, such individuals could naturalize as U.S. citizens. Richard Nicolai Belling, for example, was born in China in 1906 to a U.S. citizen father. However, although his grandfather was born in Philadelphia, his father was born in Paris and had never lived in the United States. Therefore, he was not able to transmit his U.S. citizenship to his children. As members of a family of acrobats for eight generations, Belling explained about his siblings that ‘Bob was born in Chita, Siberia; Tom was born in Manila; I was born in Harbin, China; Victoria was born in Hungary; Maude was born in Copenhagen’. When Belling applied for a U.S. passport in 1932, he was informed that he was not a U.S. citizen but Chinese through his birth in Harbin (Tangle Leaves, Citation1932). Recognized by U.S. authorities as white, Belling naturalized as a U.S. citizen in 1944 (Ancestry.com, Citation2012). By this time, ethnic Chinese were also able to naturalize, followed by other Asian immigrants in 1952.

Regulating immigrant citizens

Ethnic Chinese were not only the most significant and consistent group to use immigrant citizenship, they were the immigrant citizens whose citizenship was most consistently challenged. Even though Wong Kim Ark secured jus soli birthright citizenship for himself, each of his legally claimed children had to fight to secure their own jus sanguinis immigrant citizenship status. Nativists who opposed Chinese migration were especially concerned about immigrant citizens, both because U.S. citizen status was more secure than other immigration statuses and because their numbers threatened to undercut efforts at Chinese exclusion.

Following Wong Kim Ark, anti-Chinese activists worked to prevent Chinese Americans’ children from obtaining U.S. citizenship. Nativists claimed that most immigrant citizen arrivals were not true U.S. citizens and, even if they were recognized, they were accidental Americans. However, despite massive opposition to Chinese immigrant citizen migration and multiple exclusion laws introduced in the early 1900s, U.S. congressmen did not introduce legislation to limit the transmission of jus sanguinis citizenship to Chinese-born children of U.S. citizen fathers. Legally, statutory jus sanguinis citizenship was less secure than constitutionally guaranteed jus soli citizenship. Statutory transmission of citizenship could have been restricted for Chinese children through legislation, just as naturalization had been barred. It is not clear why such legislation was not introduced. However, one possible reason is that, even though jus sanguinis citizenship was provided by U.S. law, under Chinese exclusion it was not secure in practice. After the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in United States v. Ju Toy (Citation1905), arrivals whose U.S. citizenship claims were denied by immigration authorities had no judicial recourse. As Lucy Salyer has written, with this decision, ‘the Court appeared to blur the distinction between aliens and citizens and to subject both to the same bureaucratic discretion and authority’ (Citation1995, 114).

In place of legislation, U.S. authorities attempted to deny immigrant citizenship through two key means: they created new regulations in an attempt to end jus sanguinis immigrant citizenship and they closely questioned every Chinese arrival’s claim to U.S. citizenship. The regulations were struck down. However, jus sanguinis and jus soli birthright citizenship remained provisional, dependent upon arrivals’ ability to prove their birthplace or family relationship during U.S. immigration investigations (Salyer Citation1995, 209–11).

In 1915, the Department of Labor developed a rule that the foreign-born children of U.S. citizens of Chinese descent were not U.S. citizens (Treaty, Laws, and Rules Governing the Admission of Chinese, Citation1915, 30; Weedin v. Chin Bow (Citation1927), 659). The Department also required that male children provide satisfactory evidence not only of their relationship to their father but also their dependency as a member of their father’s household, evidence that was required only of ethnic Chinese (Treaty, Laws, and Rules Governing the Admission of Chinese, Citation1915, 30; Quan Hing Sun).

In Citation1916, the Attorney General invalidated the Department of Labor rule which claimed that Chinese – and only Chinese – children were not U.S. citizens by jus sanguinis descent (cited in Weedin v. Chin Bow (Citation1927), 659). In 1918, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit struck down the Department of Labor rule requiring proof of dependency as it created additional restrictions upon ‘the sons of citizens of the United States of Chinese birth’. Somewhat surprisingly given the racial restrictions on Asian naturalization, the court claimed that ‘we know of no law making a race distinction in American citizenship’ (Quan Hing Sun, 405). Although they overlooked laws that made Asians the only group ineligible for naturalized U.S. citizenship at this time, the court’s ruling made jus sanguinis birthright citizenship more accessible to Chinese immigrant citizens.

Nativists, including federal officials, who opposed the rights of Chinese Americans often impugned them as ‘accidental’ citizens. They protested that Chinese had become U.S. citizens only because of their chance presence in U.S. territory, but this territorial presence gave them global mobility, including the unqualified right to reenter the United States. At the same time, and somewhat contradictorily, they also claimed that Chinese were instrumental citizens because they used their citizenship to secure rights without fully assimilating to white American cultural norms.

After the Attorney General’s 1916 ruling, Commissioner-General of Immigration Anthony Caminetti protested that ‘a person of the Mongolian race who is so fortunate as to be born here is vested by the “accident of birth” with American citizenship’ (Annual Report Citation1916, xv). This language echoed earlier arguments made against Wong Kim Ark’s U.S. citizenship in both the federal circuit court in San Francisco and at the U.S. Supreme Court (Wong Kim Ark, 649, 731). Caminetti continued, including the second generation:

And no matter how thoroughly foreign he may be in his ideas, ideals, and aspirations, even though he be brought up in the midst of a ‘colony’ of his own people and never learns to speak English (and many such cases have occurred), and even though he demonstrates his foreign inclinations by going to the native country of his parents and marrying and establishing a home there and there begets children and rears them to maturity, having them in turn marry among their own people, the children of such a person, born and reared abroad and having not the least idea of what American citizenship means, may at any time … come to the United States, be freely admitted at our ports (irrespective of their moral, mental, or physical condition) and on the very day of landing claim and exercise all the rights, immunities and privileges of American citizenship. (Annual Report Citation1925, xv-xvi)

In Caminetti’s estimation, people of ‘the Mongolian race’ remain foreign whether they are territorially inside or outside the United States. This foreignness is emphasized by his repetition of Chinese territory over ‘there’ and ‘their own people’ in contrast with ‘our ports’.

Linking concerns about jus soli and jus sanguinis citizenship, Caminetti demonstrates how citizenship acquisition was intimately connected with freedom of movement. And how, for nativists at the Immigration Bureau, this was a key source of concern. Caminetti expressed dismay at the fact that native-born U.S. citizens were free to leave the United States and territorially foreign-born U.S. citizens were ‘freely admitted at our ports’, not subject to exclusion restrictions. The Commissioner-General conveniently overlooked both anti-miscegenation laws in California and restrictions on the immigration of Chinese women, laws that pushed Chinese to ‘marry among their own people’ and live in transnational marriages (Pascoe Citation2009; Peffer Citation1999; Stevens Citation2002). He also discounted immigration officials’ extensive efforts to reduce the free movement of immigrant citizens into the United States. However, Caminetti’s opposition to Chinese American birthright citizenship on the basis of both supposed foreignness and actual mobility was consistent with many nativists’ concerns.

As the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) noted in a Senate Immigration Committee hearing in 1930, ‘not only citizens but the children of citizens have come under attack by the Labor Department and had to appeal to the courts for redress’. ‘The court’, according to the ACLU, ‘is the only curb on the Labor Department. And this curb it resents’ (Pinchot Citation1930, 66). Although regulatory efforts to restrict ethnic Chinese jus sanguinis citizenship were overturned in 1916 and 1918, legal scholar Kristin Collins notes that immigration officials were effective at denying citizenship to applicants suspected of being the children of second wives, when their U.S. citizen fathers were simultaneously married to first wives, a polygamous relationship that brought the children’s legitimacy and therefore their citizenship into question (2168–2183).

In addition to attempting to restrict Chinese mobility through regulations, the Immigration Bureau also strictly enforced the law, carefully scrutinized citizenship documentation and interrogated immigrant citizens about their family relationships. Immigration officials – rightly – suspected that many immigrant citizens made fraudulent claims. ‘Since the Supreme Court rendered its decision in the Wong Kim Ark case’, Commissioner-General Daniel Keefe wrote in 1909, ‘it has been necessary to recognize as American citizens Chinese born in the United States; and now that the second generation of the class is coming forward in such numbers the matter becomes more grave than ever. Thousands of Chinese have availed themselves of this claim and “established” American birth by fraudulent means’ (Annual Report Citation1909, 126; Lew-Williams Citation2021, 111).

Immigration officials questioned Chinese arrivals in detail about their relationships (Quock Ting Citation1891, 417). Contemporary commentators, both officials and immigrants themselves, noted that the investigations were so complex and far-flung that even legitimate children needed to rehearse their identities (Lai, Mark, and Yung Citation1991). In the cases of Wong Kim Ark’s children, their immigration outcomes do not necessarily reflect their legitimate or paper relationships to Wong Kim Ark, but their ability to effectively navigate the investigation process. According to Wong Yoke Fun’s Citation1910 immigration file, Wong Kim Ark was not aware of his son’s impending arrival. As a result, they likely didn’t coordinate, as was common with both legitimate and paper families. Inspectors in the case asked both Wong Kim Ark (‘the alleged father’) and Wong Yoke Fun detailed questions, ‘particular attention being paid to the occupants of the houses in the home village, concerning which minute details should be obtained’ (Wong Yoke Fun). These ‘minute details’ may have been used to establish identity, but they also made it more likely that the testimonies would not align, and Wong Yoke Fun would be rejected. Wong Kim Ark’s second claimed son was initially rejected but successfully appealed and entered the United States, while his younger claimed children were all successful in entering the United States (Wong Yook Thue, Wong Hang Juen, Wong Yook Jim). Chinese immigrants were successful at circumventing exclusion laws through claims of citizenship. But the denial of Wong Yoke Fun suggests the limitations of these strategies. In practice, both jus soli and jus sanguinis citizenship were limited for Chinese Americans, dependent upon both correct documentation and congruent testimony.

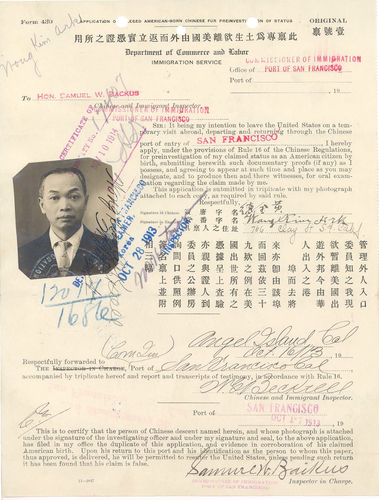

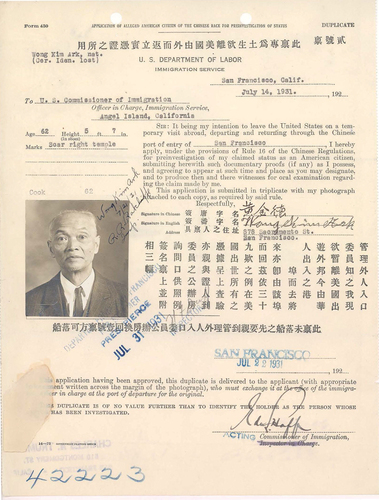

Immigration officials’ terminology in describing immigrant citizens of Chinese descent reflected their assumptions that all such applicants were fraudulent. As forms such as the departure declaration were regularized, they defined each applicant as an ‘alleged American citizen of the Chinese race’ (see ). This is striking as applicants completing these forms prior to traveling to China had already proven their U.S. citizenship to the satisfaction of immigration authorities. In case files, officials repeatedly described ‘alleged’ family relationships (Wong Yoke Fun; Wong Yook Thue). They continued to describe paternal connections as ‘alleged’ relationships long after they had legally acknowledged an applicant’s citizenship and family relationship. When Wong Yook Jim, the youngest son claimed by Wong Kim Ark, arrived in San Francisco in 1926, his relationship with Wong Kim Ark and his family was recognized and his entry was approved. Nonetheless, the formal language of the administrative ruling was begrudging, never fully accepting any of his relatives’ legal statuses or their relationship to one another. The decision reads in part:

Figure 2. Application for alleged American-born Chinese for preinvestigation of status by Wong Kim Ark, 1913, Return Certificate Application Case Files of Chinese Departing, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (Record Group 85), NAID: 18556185, National Archives at San Francisco, San Bruno, California.

Figure 3. Application of alleged American citizen of the Chinese race for preinvestigation of status by Wong Kim Ark, 1931, Return Certificate Application Case Files of Chinese Departing, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (Record Group 85), NAID: 18556185, National Archives at San Francisco, San Bruno, California.

Applicant is claimed as the 4th and last and youngest son of Wong Kim Ark, recognized by this service as a native. The alleged father last arrived at this port and was landed as a native on Form 430 Nov. 2, 1914. The applicant is claimed to have been born Jan. 5, 1915. An alleged brother of applicant was admitted on appeal in Sept. 1924 and another brother admitted by a board at this station March, 1925. The alleged father in testifying in those cases claimed a son of applicant’s name and age. (Wong Yook Jim)

The Immigration Bureau’s reporting of immigrant citizen arrivals similarly reproduced the assumption that Chinese applicants who claimed to be sons of natives were fraudulent. Until 1924, the Immigration Bureau recorded the number of Chinese who applied for admission by various classes, including the number of U.S. citizen applicants who were admitted and debarred. However, starting in 1925, the Bureau only recorded admitted U.S. citizens of Chinese descent (Annual Report Citation1925, 179). If they were not legally recognized or admitted as U.S. citizens, they ceased to be counted. By not recording U.S. citizen applicants who were denied entry, the annual reports replicated their alienation.

Conclusion

Immigrant citizens of Chinese descent – Wong Kim Ark’s children – show that immigration and citizenship statuses are not opposites. They challenge the antithesis between immigrants and citizens because they are simultaneously immigrants and citizens. As U.S. citizens who immigrated to the United States, they were citizens before they were immigrants, reversing the assumed telos from immigrant to citizen and replacing it with a new route from citizen to immigrant. Their acquisition of jus sanguinis birthright U.S. citizenship in China also unsettles the common assumption that citizens are territorially present within the nation of their citizenship. Immigrant citizens are territorially but not legally alien. In their efforts to secure citizenship rights to enter the United States, immigrant citizens demonstrated that citizenship entails not only the right to territorially presence but also the right to territorial absence and mobility.

Nativists in Congress, in the Immigration Bureau and in general connected their concerns about Chinese American citizenship to fears of the United States being overrun by Chinese immigrants. In this way, they recognized the critical connections between citizenship and immigration, acknowledging that migration and mobility were critical citizenship rights for Chinese Americans. After Wong Kim Ark, U.S. immigration officials developed rules and regulations to prevent immigrant citizens of Chinese descent from entering the United States. Their efforts were rejected by the courts. Nonetheless, the transmission of U.S. citizenship was territorially limited through statute for all citizens. Starting with the first U.S. naturalization law in 1790, U.S. citizen fathers were allowed to pass their citizenship status to their children only if they themselves had resided in the territory of the United States. In addition, immigrant citizenship status and migration rights were limited in practice. Under extensive interrogations, many immigrant citizens, including one of Wong Kim Ark’s four claimed sons, were rejected in their efforts to immigrate to the United States. Others were successful, even though they were, as a different son claimed by Wong Kim Ark later acknowledged, not lawfully entitled to entry. As jus sanguinis birthright citizens claimed the right to immigrate to the United States, U.S. officials sought to restrict their immigration by not recognizing their citizenship. In attempting to distinguish between birthright citizens and paper sons, U.S. authorities introduced policies that blurred the distinction between citizens and aliens, highlighting the ways in which citizenship is a legally constructed status. In this way, Wong Kim Ark and his children shaped the uneven terrain on which U.S. citizenship was constructed.

While nativists claimed that Chinese American citizens were accidental citizens, the term ‘accident of birth’ has been used more neutrally to contrast ascribed birthright citizenship with consensual and intentional process of naturalization (Smith Citation1997, 13). However, barred from naturalization, Chinese Americans were not accidental but very intentional about securing birthright citizenship. Some immigrant citizens embodied the U.S. Immigration Bureau’s concern that ‘the cloak of American citizenship would not embrace persons without a real desire to become an integral part of the body politic, but who sought citizenship merely for convenience or for selfish ends’ (Cushman Citation1943, 14). They took the United States’ grudging recognition of formal legal citizenship and used it for their own ends. In the process, immigrant citizens secured broad and vital immigration and citizenship rights, and they made a place for themselves in the United States.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Michael Bernath, John Cheng, Kirsten Fermaglich, Scott Heerman, Stephanie Hinnershitz, Andrea Louie, Natalia Molina, Mindy Morgan, Mae Ngai, David Thronson, Judy Wu, and participants in The Many Fourteenth Amendments Conference at the University of Miami. Many thanks to Sean Heyliger and John Seamans at the National Archives in San Bruno, the anonymous reviewers and the outstanding editorial staff at Citizenship Studies. Very special thanks to my excellent and persistent undergraduate research assistants Julia Lee and Trenton Sabo.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Of course, we should not uncritically accept U.S. claims of territory. There are other groups who also occupy interstitial relationships between citizenship, immigration and alienage, including especially historical and contemporary U.S. imperial subjects such as Filipinos, Puerto Ricans and Pacific Islanders. Debates about Pacific Islanders’ access to birthright citizenship under the Fourteenth Amendment continue today. See, for example: Ngai Citation2004, 96–126; Perez Citation2008; Punzalan Isaac Citation2006, 23–47; Neuman and Brown-Nagin Citation2015; ‘Developments’ 2017.

References

- Ancestry.com. 2012. Mississippi, U.S., Naturalization Records, 1907–2008 [Database On-Line].

- Annual Report of the Commissioner-General of Immigration. 1909. Washington, D.C: G.P.O.

- Annual Report of the Commissioner-General of Immigration. 1916. Washington, D.C: G.P.O.

- Annual Report of the Commissioner-General of Immigration. 1925. Washington, D.C: G.P.O.

- Audain, M. 2014. “Mexican Canaan: Fugitive Slaves and Free Blacks on the American Frontier, 1804-1867.” PhD diss., Rutgers University.

- Berger, B. 2016. “Birthright Citizenship on Trial: Elk v. Wilkins and United States v. Wong Kim Ark.” Cardozo Law Review 37 (4): 1185–1258.

- Carbado, D. 2005. “Racial Naturalization.” American Quarterly 57 (3): 633–658. doi:10.1353/aq.2005.0042.

- Collins, K. 2014. “Illegitimate Borders: Jus Sanguinis Citizenship and the Legal Construction of Family, Race, and Nation.” Yale Law Journal 123: 2134–2235.

- Cushman, J. “The Naturalization of Alien Seamen” Lecture, May 6, 1943, File 165/253A, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (Record Group 85), National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

- Daniels, R. 2004. Guarding the Golden Door: American Immigration Policy and Immigrants Since 1882. New York: Hill and Wang.

- Edwards v. California, 314 U.S. 160 (1941).

- Frost, A. 2021. “‘By Accident of Birth’: The Battle Over Birthright Citizenship After United States v. Wong Kim Ark.” Yale Journal of Law & Humanities 32 (1): 38–76.

- Haney López, I. 2006. White by Law: The Legal Construction of Race. New York: New York University Press.

- Hsu, M. 2000. Dreaming of Gold, Dreaming of Home: Transnationalism and Migration Between the United States and South China, 1882–1943. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Immigration and Nationality Act, 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(15).

- Jones, M. S. 2018. Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jun, H. H. 2011. Race for Citizenship: Black Orientalism and Asian Uplift from Pre-Emancipation to Neoliberal America. New York: New York University Press.

- Kahn, J. 2013. Mrs. Shipley’s Ghost: The Right to Travel and Terrorist Watchlists. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Lai, H., G. L. Mark, and J. Yung. 1991. Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island 1910–1940. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Lee, E. 2002. “Wong Kim Ark: Chinese American Citizens and U.S. Exclusion Laws, 1882–1943.” In The Human Tradition in California, edited by C. Davis and D. Igler. Wilmington: Scholarly Resources, 65–80.

- Lee, E. 2003. At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration During the Exclusion Era, 1882–1943. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Lew-Williams, B. 2018. The Chinese Must Go: Violence, Exclusion, and the Making of the Alien in America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Lew-Williams, B. 2021. “Paper Lives of Chinese Migrants and the History of the Undocumented.” Modern American History 4 (2): 109–130. doi:10.1017/mah.2021.9.

- Lew-Williams, B. 2023. “Chinese Naturalization, Voting, and Other Impossible Acts.” The Journal of the Civil War Era 13 (4): 515–536. doi:10.1353/cwe.2023.a912400.

- Litwack, L. F. 1961. North of Slavery: The Negro in the Free States, 1790-1860. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lowe, L. 1996. Immigrant Acts: On Asian American Cultural Politics. Durham: Duke University Press.

- McKenzie, B. 2017. “To Know a Citizen: Birthright Citizenship Documents Regimes in U.S. History.” In Citizenship in Question: Evidentiary Birthright and Statelessness, edited by B. Lawrance and J. Stevens. Durham: Duke University Press, 117–131.

- McKeown, A. 1999. “Transnational Chinese Families and Chinese Exclusion, 1875–1943.” Journal of American Ethnic History 18 (2): 73–110.

- Motomura, H. 2007. Americans in Waiting: The Lost Story of Immigration and Citizenship in the United States. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nackenoff, C., and J. Novkov. 2021. American by Birth: Wong Kim Ark and the Battle for Citizenship. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

- “Native-Born Chinese Are Legally Adjudged to Be Citizens,” San Francisco Chronicle, January 4, 1896.

- Neuman, G., and T. Brown-Nagin, eds. 2015. Reconsidering the Insular Cases: The Past and Future of the American Empire. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Ngai, M. 2004. Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Ngai, M. 2007. “Birthright Citizenship and the Alien Citizen.” Fordham Law Review 75: 2521–2530.

- Ong, A. 1999. Flexible Citizenship: The Cultural Logics of Transnationality. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. December 2023. “immigrant (n.), sense 1.” doi:10.1093/OED/8792844680.

- Ozawa v. United States, 260 U.S. 178 (1922).

- Park, J. S. W. 2004. Elusive Citizenship: Immigration, Asian Americans, and the Paradox of Civil Rights. New York: New York University Press.

- Parker, K. 2001. “State, Citizenship, and Territory: The Legal Construction of Immigrants in Antebellum Massachusetts.” Law and History Review 19 (3): 583–643. doi:10.2307/744274.

- Pascoe, P. 2009. What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Peffer, G. A. 1999. If They Don’t Bring Their Women Here: Chinese Female Immigration Before Exclusion. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Perez, L. M. 2008. “Citizenship Denied: The Insular Cases and the Fourteenth Amendment.” Virginia Law Review 94: 1029–1081.

- Phan, H. G. 2006. “Imagined Territories: Comparative Racialization and the Accident of History in Wong Kim Ark.” Genre 39 (3): 21–38. doi:10.1215/00166928-39-3-21.

- Pinchot, A. 1930. “Statement of the American Civil Liberties Union and American Committee Opposed to Alien Registration.” Authorizing the Issuance of Certificates of Admission to Aliens: Hearings Before the Committee on Immigration, U.S. 50–68. Senate, 71st Cong., 2nd sess.

- Punzalan Isaac, A. 2006. American Tropics: Articulating Filipino America. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Putnam, L. 2013. Radical Moves: Caribbean Migrants and the Politics of Race in the Jazz Age. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Quan Hing Sun v. White, 254 F. 405 (1918).

- Quock Ting v. United States, 140 U.S. 417 (1891).

- Saenz v. Roe, 526 U.S. 489 (1999).

- Salyer, L. E. 1995. Laws Harsh As Tigers: Chinese Immigrants and the Shaping of Modern Immigration Law. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Salyer, L. E. 2004. “Baptism by Fire: Race, Military Service, and U.S. Citizenship Policy, 1918-1935.” The Journal of American History 91 (3): 847–876. doi:10.2307/3662858.

- Salyer, L. E. 2005. “Wong Kim Ark: The Contest Over Birthright Citizenship.” In Immigration Stories, edited by D. A. Martin and P. H. Schuck. New York: Foundation Press, 89–109.

- Smith, R. M. 1997. Civic Ideals: Conflicting Visions of Citizenship in U.S. History. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Stevens, T. 2002. “Tender Ties: Husbands’ Rights and Racial Exclusion in Chinese Marriage Cases, 1882-1924.” Law & Social Inquiry 27 (2): 271–305. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4469.2002.tb00805.x.

- Stordeur Pryor, E. 2016. Colored Travelers: Mobility and the Fight for Citizenship Before the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- “Tangle Leaves Man without a Country.” 1932. New York Times, February 4, 1932.

- Teague, J. 2015. “I, Too, Am America: African-American and Afro-Caribbean Identity, Citizenship and Migrations to New York City, 1830s to 1930s.” PhD diss., UCLA.

- Torpey, J. 2000. The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship and the State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Treaty, Laws, and Rules Governing the Admission of Chinese. 1915. Rules Approved October 15, 1915. Washington, D.C: G.P.O.

- United States v. Ju Toy, 198 U.S. 253 (1905).

- United States v. Thind, 261 U.S. 204 (1923).

- United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898).

- U.S. Const. amend. XIV 1868

- Volpp, L. 2001. “‘Obnoxious to Their Very Nature:’ Asian Americans and Constitutional Citizenship.” Asian Law Journal 5 (1): 71–87. doi:10.1080/13621020020025196.

- Volpp, L. 2007. “Citizenship Undone.” Fordham Law Review 75: 2579–2586.

- Weedin v. Chin Bow, 274 U.S. 657 (1927).

- Wilkerson, I. 2010. The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration. New York: Random House.

- Wong Kim, Ark. Application for Alleged American Citizen of the Chinese Race for Preinvestigation of Status by Wong Kim Ark. Return Certificate Application Case Files of Chinese Departing, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (Record Group 85), NAID: 18556185. San Bruno, California: National Archives at San Francisco.

- Wong Kim Ark Departure Statement. 1894. November 5, 1894, in the Matter of Wong Kim Ark for a Writ of Habeas Corpus, Admiralty Case Files, 1851–1966, Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685-2009 (Record Group 21), NAID: 2641490. San Bruno, California: National Archives at San Francisco.

- Wong Yook Jim. 1925-1931. File 30980-007-05. Immigration Arrival Case Files, 1884–1944, Records of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (Record Group 85), NAID: 296445. San Bruno, California: National Archives at San Francisco.

- Wong Hang Juen (aka Wong Yook Sue). 1924-1966. A-File A12267981. Alien Case Files, 1944–2020, Records of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (Record Group 566), NAID: 6105565. San Bruno, California: National Archives at San Francisco.

- Wong Yoke Fun. 1910. File 9079-590C, Immigration Arrival Case Files, 1884-1944, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (Record Group 85). San Bruno, California: National Archives at San Francisco.

- Wong Yook Thue. 1924-1949. File 29438-005-23. Immigration Arrival Case Files, 1884-1944, NAID 296445, Records of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (Record Group 85). San Bruno, California: National Archives at San Francisco.

- Wyatt, A. 2015. “Birthright Citizenship and Children Born in the United States to Alien Parents: An Overview of the Legal Debate.” Congressional Research Service Report 28 October.