ABSTRACT

As women’s presence in higher education grows, their limited representation in academic leadership roles remains a critical concern. This study investigates the complex institutional barriers hindering women’s advancement into leadership positions. Drawing on in-depth interviews with 37 women in academia, our analysis reveals multifaceted challenges rooted in institutional, organisational, and individual factors. Institutionally, cultural and societal norms, including those influenced by religious traditions, profoundly influence gender dynamics within specific contexts. Organizational factors, such as a predominantly male workforce and entrenched practices, pose significant obstacles to women’s career progression in academic institutions. At a personal level, we introduce the concept of internalisation of subjugation, which captures women academics’ tendency to adopt more masculine practices, echoing observations from traditional leadership models. This research offers valuable insights into the nuanced barriers constraining women’s path to academic leadership. A comprehensive understanding of these challenges is essential for developing targeted strategies and policies to promote gender equality and inclusivity in higher education institutions.

Introduction

The issue of gender inequality has garnered considerable research attention, particularly in light of the challenging circumstances faced by women in Pakistan (e.g. Ashraf and Pianezzi Citation2023; Ali and Syed Citation2017, Masood and Azfar Nisar Citation2019; Citation2020; Masood Citation2018; Syed and Ali Citation2013). Some scholars argue that gender disparities are entrenched within cultural and institutional frameworks, especially in patriarchal societies. In such societies, women encounter cultural barriers that hinder their economic, political, and social participation (Ali Citation2013; Syed and Dawn Metcalfe Citation2017). Within Pakistani society, there appears to be a prevailing belief that women should assume a societal role distinct from that of men, leading to a dependence on men in various aspects of life (Habiba, Ali, and Ashfaq Citation2016). The deeply rooted legacy of male dominance and gender segregation has resulted in limited, sporadic, and often temporary participation of women in the public sphere.

Individually and collectively, both in private and public spheres, women find themselves confronted with challenging political and ethical decisions within organisational contexts (Aldossari and Calvard Citation2022). These decisions revolve around navigating the complexities of resistance or accommodation to diverse cultural and patriarchal influences. In specific societal contexts, such as Pakistan, a convergence of various traditions, customs, and codes significantly influences how individuals experience and respond to conflicts, power relations, interactions, and the potential for change (Masood Citation2019). Despite regulatory measures aimed at promoting gender equality, women in such contexts continue to face entrenched barriers that hinder their career growth (Alvesson and Due Billing Citation2009; Kossek, Su, and Wu Citation2017). Specifically, in patriarchal environments, women often encounter cultural obstacles that impede their economic, political, and social participation (McCarthy and Muthuri Citation2018). Additionally, women grapple with career challenges stemming from context-specific impediments, as limited research has explored the interplay of multi-level institutional barriers to their academic advancement (Taser-Erdogan Citation2022; Ali and Syed Citation2017). This study, providing a Pakistani perspective, contributes to understanding the institutionalised barriers hindering women’s advancement and explores the potential role of Human Resource Development (HRD) in mitigating gender inequality.

Although women now constitute nearly half of the student population across various university programmes and disciplines (Rivera Citation2017), their presence in higher education has grown in Pakistan (Khokhar Citation2018), including the establishment of women-only universities with women in leadership roles. Despite these positive developments, women remain underrepresented in leadership positions within higher education institutions. Previous studies have been primarily focused on uncovering societal and organisational gendered barriers to women’s engagement in work beyond the confines of the home (Ali and Syed Citation2017; Masood and Azfar Nisar Citation2020; Mohsin and Syed Citation2020), ignoring their career advancement. Additionally, there is limited research on the complex interplay of institutional impediments at various levels affecting women’s academic career progression. With the increasing number of women in universities, an investigation into women’s careers can expand empirical knowledge beyond what is already known. Nonetheless, recent research has challenged depictions of Muslim women in similar contexts as lacking agency or being weak by illustrating their longstanding efforts to assert their right to work, advance their careers, and actively resist gender inequity and discrimination (Jamjoom and Mills Citation2023; Taser-Erdogan Citation2022; Rodriguez and Ridgway Citation2019). As Tlaiss and Khanin (Citation2023) suggest that future research endeavours need to employ a multi-level approach to analyse the experiences of senior, middle, and junior women leaders to gain insights into whether career advancement strategies differ based on an employee’s position in the organisational hierarchy. Against this background, this study delves into the question of why women continue to be underrepresented in leadership positions, notwithstanding their growing presence within Pakistani universities. It specifically centres on exploring the impact of religious values and cultural traditions on the current status of women in leadership roles.

This study draws upon the institutional work theory (Lawrence and Suddaby Citation2006), which extends beyond the traditional institutional theory proposed by DiMaggio and Powell (Citation1983), emphasising conformity to institutional pressures. Instead, it shifts the focus towards agency within institutional theory (Battilana and D’aunno Citation2009). By broadening the perspective of agency concerning institutions, institutional work avoids depicting actors as either passive cultural dopes confined by institutional arrangements or hyperactive institutional entrepreneurs (Lawrence et al. Citation2009, 1). Institutions do not emerge ex nihilo, nor are they inherently inscribed into society from its inception. Instead, they are considered social accomplishments, akin to ‘social facts’ in a Durkheimian terminology. This perspective emphasises agency – the active actions and initiatives of social and organisational actors. It also conceptualises institutions as semi-stable social arrangements that are constantly susceptible to modification or change (Styhre Citation2014). One of the most noteworthy institutional changes in the past century is the integration of women into the labour market across various occupational groups and professions. Despite the progress towards a more equitable working environment, gender equality should not be taken for granted or assumed (McCarthy and Muthuri Citation2018). It is a social accomplishment grounded in everyday practices and, at times, forms of resistance. Examining the institutionalised barriers that women encounter in their journey towards leadership positions, and understanding how they navigate these challenges, closely aligns with the concept of institutional work proposed by Lawrence and Suddaby (Citation2006).

Utilizing in-depth semi-structured interviews, our research delves into the narratives of Pakistani women who have successfully attained decision-making positions across various university departments. This study contributes to the existing literature on gender (in)equality in academia by illustrating how individuals within organisations engage in institutional work, influencing the status quo through the dominant interplay of three factors: cultural, organisational, and individual influences. Additionally, it sheds light on how organisational systems and cultures persist in excluding women from equal opportunities, aligning with insights from previous studies (Roos et al. Citation2020). Lastly, our research introduces the concept of the internalisation of subjugation. This concept reflects women academics’ willingness to adopt more masculine practices, as observed in the traditional leadership model. They do so due to the perception that holding a leadership position could adversely affect their psychological well-being. The internalisation of subjugation manifests through institutional, organisational, and societal practices, which are not only seen as oppressive but also contribute to the reproduction of subjugation, shaping the identities of women within academic settings.

Theoretical background

Given that levels of analysis are crucial in shaping HRD research and practice and recognising the underutilisation of macro sociological lenses in HRD research, institutional theory offers a suitable framework for analysing research from a macro level (Abadi, Dirani, and Dena Rezaei Citation2022; Garavan et al. Citation2018; Scully-Russ and Torraco Citation2020). Rooted in sociology, institutional theories emphasise the influence of institutional pressures originating from the social and cultural contexts in which these theories are situated. Researchers in HRD who subscribe to institutional theory argue that organisational structures and practices are not primarily the result of rational decision-making aimed solely at efficiency (see e.g. Kuchinke Citation2000; Tkachenko et al. Citation2022). Instead, they posit that these structures and practices largely emerge from the imperative of conforming to institutional pressures.

As a corollary, Lawrence and Suddaby (Citation2006) introduced the concept of institutional work to emphasise the role of individuals in processes of change, seeking to advance existing institutional theory. They defined institutional work as ‘purposeful action by individuals and organizations aimed at creating, maintaining, and disrupting institutions’ (Lawrence and Suddaby Citation2006, 215). In this view, institutions are not seen as pre-existing structures but as social accomplishments or social facts, as per Durkheim’s vocabulary (Styhre Citation2014). This understanding of agency portrays institutions as semi-stable structures susceptible to change. A significant institutional change in recent decades, particularly in developing countries, has been the increased participation of women in labour markets and various professions. The primary theoretical objective of this study is to contribute to existing knowledge by exploring how women respond to multi-level institutional demands in their pursuit of leadership positions, influenced by contextual factors. The concept of institutional work helps elucidate such practices (Leca et al. Citation2009) especially within HRD context. Gender inequality persists despite the existence of national laws, international standards, and advocacy efforts.

In essence, the concept of institutional work involves the interaction between institutions and actions, where actions within institutional structures simultaneously produce, reproduce, and transform those very structures (Lawrence et al. Citation2011; Lawrence et al. Citation2013). This perspective on institutional work is a valuable analytical tool because it recognises agency and establishes recursive connections with past institutional settings. Institutional work encompasses the entirety of actions necessary to create, sustain, or disrupt an institution, rather than assuming that institutions are rigid monoliths that unilaterally shape social action. When studying gender inequality in leadership positions within universities, adopting such a perspective allows for the examination of how new institutional practices and actors, such as women faculty and staff, can either hinder or facilitate the advancement of women. While the majority of studies on the underrepresentation of women are based on the institutional environments of developed countries (Calás, Smircich, and Holvino Citation2013), it is important to acknowledge that underdeveloped countries face unique challenges that serve as obstacles to achieving gender parity in academia.

Muslim women and leadership positions

In the career literature, there is a general consensus among scholars that the trajectories of women’s careers may follow distinct paths in non-Western contexts due to variations in national and cultural factors. Career advancement is defined as promotions to higher levels in a management hierarchy, and it is a multi-layered phenomenon (Taser-Erdogan Citation2022). External macro environmental factors, encompassing broader structural and situational elements, have the potential to significantly impact organisational careers (Aldossari and Calvard Citation2022). These factors may also shape individuals’ perceptions and motivations regarding their careers and advancement. Syed and Dawn Metcalfe (Citation2017) urge HRD scholars to conduct more in-depth research into the experiences of women leaders, emphasising the importance of considering the role of context. Similarly, Bierema (Citation2020) call for a more comprehensive conceptualisation of social culture within HRD. While developed countries have implemented regulatory reforms empowering women, significant disparities persist in developing nations, especially Muslim women in South Asia. In Islam, women are typically expected to navigate and balance their gender roles, encompassing responsibilities as mothers and wives, with their societal roles as workers or leaders (Grünenfelder Citation2013).

According to certain scholars, a meticulous examination of Islamic texts reveals directives that endorse complementarity between the sexes and advocate for broader strategies to promote diversity while avoiding gender discrimination and inequality (Syed and Dawn Metcalfe Citation2017; Syed and Van Buren Citation2014). While others put it differently, asserting that in Islamic understanding, males and females should be treated differently, not unequally (Koburtay and Abuhussein Citation2021). In Islam, justice is considered paramount rather than strict equality (Khan, Osama Nasim Mirza, and Vine Citation2023). Within the Islamic faith, justice is defined by adherence to God’s commands, even if these directives may entail unequal rights in certain instances.

Scholars have contended that passivity can be considered a form of agency in Muslim countries like Indonesia (Parker Citation2005). Rather than engaging in active resistance, Muslim women may opt for strategic manoeuvres, expressing their resistance covertly (Mustafa Citation2017). The historical evolution and nature of early Muslim societies have significantly influenced the development and transformation of women’s roles. For example, in a survey involving women leaders (Al-Ahmadi Citation2011), endeavours to highlight the challenges faced by women leaders in the public sectors of Saudi Arabia. The results indicate that the primary challenges revolve around structural issues, insufficient resources, and a lack of empowerment. Surprisingly, cultural and personal challenges ranked lower, contrary to common perceptions. In another study conducted in Jordanian settings, Koburtay et al. (Citation2020) discovered that despite Islamic guidelines promoting fairness and justice in employment, gender discrimination and power imbalances persisted due to the influence of tribal traditions and Bedouin customs. These were perpetuated through patriarchal interpretations of Islam. Recently, Oktaviani (Citation2023) has attempted to understand how women leaders adopt, modify, or reject forms of hegemonic femininity that shape their constructions of subjectivity in Muslim majority, Indonesia. Her findings illuminate how participants navigate hegemonic femininity by constructing their own versions of feminine subjectivity, thereby negotiating their roles in gendered leadership in diverse ways. Similarly, in the quest to understand why women continue to be underrepresented in management positions despite their growing presence in the Turkish banking sector, Taser-Erdogan (Citation2022) reveals that women’s limited representation at the managerial level is an outcome of the interplay between macro-, meso-, and micro-level issues. Research conducted by Ali and Syed (Citation2017) within the Pakistani context has demonstrated that women persist in facing substantial challenges in their careers due to local cultural practices. Specifically, it highlights issues such as societal norms related to female modesty and gender segregation at the macro level, sexual harassment, career-related challenges, and income gaps at the meso level, and considerations related to family status and agency at the micro level. In a recent study, Gul et al. (Citation2023) delve into the political engagement of Pakistani women in a society marked by sex-based discrimination and within a heavily patriarchal political system. The findings of the study indicate that women’s political engagement and decision-making face numerous hindrances. Dominated by a male-centric culture, hindered by a lack of social acceptance, impeded by structural barriers, influenced by gender-imbalanced political parties, susceptible to societal threats, and constrained by a failure to empower women, these challenges emerge as key concerns.

Specifically, it delves into the actions of women who actively endorse and sustain patriarchal ideologies and this reflects in their career choices and progression. This novel manifestation of power, denoted as ‘internalisation of subjugation’, engenders hierarchical structures within households, ultimately placing women at a disadvantage. In Pakistan, for example, women depend on man for every walk of life (Habiba, Ali, and Ashfaq Citation2016). The male domination is internalised through range of institutional forces which are embedded within the family system, cultural norms and organisational practices. Furthermore, dynamics of power operative within intimate relationships, encompassing roles such as mothers-in-law, daughters-in-law, and sisters-in-law, as they contribute to the reinforcement of patriarchal norms. This perspective shifts the focus away from scrutinising the behaviour of women and places it on the organisational structure and actions themselves. Earlier studies also shed light on women’s strategies for advancement, showcasing the utilisation of hard tactics involving assertive and aggressive behaviours, along with rational tactics emphasising exchange and compromise (Bolino, Long, and Turnley Citation2016; Smith et al. Citation2013; Tlaiss and Khanin Citation2023). Building upon these previous analyses of women’s career advancement, our study delves into the narratives of senior Pakistani women faculty members within the Higher Education Institutions (HEIs).

Barriers to Pakistani women’s careers advancement

Pakistan’s unique blend of indigenous culture and Islamic influence shapes the distinctiveness of women’s experiences in research. The country’s colonial past has left it with diverse and competing discourses. Islamist perspectives, in particular, challenge Western values such as women’s mobility and independence, aligning with Islamist views of women’s exclusivity (Mohsin and Syed Citation2020). In Pakistan, women typically marry soon after completing their education, and many are restricted from working (Rizvi Citation2014). Even for those who enter the workforce, their job options are often limited, with higher education being one of the few avenues. Women’s representation in decision-making roles within academic institutions remains low, primarily due to a complex interplay of organisational, cultural, and institutional barriers.

The experiences of Pakistani women in academia reflect this intricate interplay of cultural norms, societal expectations, and organisational dynamics, all influencing their career progression. Malik’s (Citation2011) study highlights positive factors contributing to women’s success, including family support, inspiration, commitment, self-confidence, ambition, a conducive organisational culture, and a supportive socio-cultural environment fostering women’s leadership roles in higher education. However, these positive factors coexist with deeply ingrained cultural concepts like ‘izzat’ (honour), which exert control over women in both public and private domains, reinforcing male dominance (Bhatti and Ali Citation2020). The patriarchal social structure in Pakistan often marginalises women from positions of power and influence, as emphasised by scholars like Ali and Rasheed (Citation2021). Additionally, organisational factors such as male-dominated networks and gender stereotypes, coupled with individual-level challenges like significant time spent on familial roles, present additional hurdles impeding women’s career advancement in Pakistani academia. Facing these multifaceted obstacles, women academics in Pakistan often confront challenges in advancing their careers, influenced by a complex web of socio-political factors (Mansoor and Bano Citation2022).

Furthermore, Taj’s (Citation2016) in-depth interviews shed light on the challenges faced by women managers in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) Province of Pakistan. The findings revealed numerous obstacles, including a lack of networking opportunities, corruption in the hiring process, familial issues, organisational constraints, gender biases, and political factors. Women managers, however, identified strategies for overcoming these challenges, including engaging in professional development, fostering collaboration, seeking acknowledgement, advocating for flexibility, and emphasising greater accountability.

Despite these challenges, a small percentage of women have successfully risen to leadership positions in higher education institutions across Pakistan, as depicted in Photo illustration 1. Discrimination, male-dominated networks, harassment, and being silenced have been common experiences for many of these women (Ali and Syed Citation2017; Naz, Fazal, and Ilyas Khan Citation2017). These tendencies present a significant challenge for academics, prompting the need to identify institutional processes hindering women’s professional growth and limiting their chances of reaching top positions. Affirmative action measures, such as anti-discrimination laws and diversity programs, are often employed to address serious gender inequalities in senior leadership roles. To pursue such initiatives effectively, it is crucial to identify institutional barriers at the individual, organisational, and institutional levels. Consequently, an increasing number of studies conducted in various countries, including Lebanon (Jamali Citation2009), Turkey (Taser-Erdogan Citation2022), India (Barhate et al. Citation2021), and the UK (Pryce and Sealy Citation2013), have adopted a comprehensive approach, examining the multifaceted conditions influencing women’s career trajectories. This research adopts a multilevel perspective to investigate the barriers hindering women’s career advancement, considering individual, organisational, and macro-contextual factors. Through an institutional work perspective, the study aims to provide a holistic insight into the subjective experiences of women and the structural and institutional influences shaping their career realities.

Methodology

This study utilised an interpretive qualitative approach to explore the institutional barriers that hinder Pakistani women from advancing into leadership positions within HEIs. The interpretive epistemology chosen for this research enabled an examination of how the social context influenced the career paths of women who had attained high levels of education (Denzin and Lincoln Citation2011). Participants contributed to the study by sharing their personal experiences through guided reflections in response to the researcher’s inquiries. This approach allowed participants to attribute meaning to their past experiences. After analysis, a shared pattern of lived experiences became evident among all participants.

Data collection

We employed qualitative data collection methods to investigate the personal experiences of women employed in academic roles. Our study included the participation of four universities located in the Hazara region of Pakistan. Over a period of six months, we extended invitations to 64 women, comprising 15 professors, 9 associate professors, 17 assistant professors, 11 lecturers, 9 administrators, and 3 hostel wardens. We reached out to them through a combination of email invitations and personal connections, seeking their participation in our study. Our initial outreach for participation involved personalised email and telephone solicitations, with some contacts made through relevant departments. Alongside these invitations, we provided a comprehensive letter that detailed the purpose, process, potential benefits, and implications of their involvement in the study. One of the co-authors utilised her network, including her thesis supervisor and those of her colleagues, to identify potential informants. Additionally, online social media platforms such as LinkedIn and the snowballing technique were employed to expand the search for potential participants. Subsequently, initial respondents referred potential participants to us. A total of thirty-seven interviews were conducted to elucidate the ways in which women attribute significance to their work within HEIs. Twenty-three interviews were conducted in a face-to-face format, taking place either in the informants’ offices or at locations of their choice to accommodate their convenience. Additionally, fourteen interviews were conducted via Microsoft TeamsTM and ZoomTM. Four respondents chose to receive, respond to, and return the interview questionnaire as a text file via email.

KPK is recognised as a province in Pakistan with a predominantly conservative character, largely shaped by tribal culture, traditions, and beliefs (Yousaf, Citation2017). Engaging in research within this context can have implications for the reputation of women within their respective organisations. As noted by Woodley and Lockard (Citation2016), various forms of patriarchy can influence women’s participation. This assurance was upheld due to the data collection being carried out by a woman who possessed a deep familiarity with the cultural context and maintained personal contacts within HEIs. Therefore, we employed a purposeful sampling strategy (Pratt Citation2009) to gain access to potential respondents, utilising our network ties and reference sampling methods (Patton Citation2014). This approach allowed us to deliberately select participants who could provide valuable insights and experiences relevant to our study.

Throughout the interviews, participants were guaranteed anonymity, and their responses were assured confidentiality. The adoption of semi-structured interviews aimed to facilitate open expression of participants’ thoughts. The interview questions were strategically crafted to encourage reflection on their self-perception, organisational experiences, and broader societal perspectives. This approach was chosen to gather rich and nuanced insights from the participants. The interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview protocol. This protocol encompassed a range of questions addressing various aspects of women academics’ career paths, including their administrative positions, the obstacles they encountered in their academic careers, how they exercised agency in their roles, opportunities for career advancement, systemic constraints hindering their progression to leadership positions, necessary measures to address these constraints, and coping strategies employed by women in higher education, among other topics. The interviews were conducted in private office settings, primarily in the English language, occasionally interspersed with Urdu. On average, each interview lasted approximately 73 minutes. As a result, the transcribed interview data accumulated to a total of 259 pages of double-spaced text. All interviews were audio-recorded and conducted in person by two of the authors. A summary of the characteristics of the study respondents is presented in .

Table 1. Details of respondents.

Analysis of interviews

Before commencing data collection, we diligently addressed both the considerations of validity and reliability. To ensure the validity of our approach, we adopted a comprehensive strategy. Initially, we recorded interviews and took meticulous notes during and immediately after each interview, aiming to capture any non-verbal cues that might have influenced the interview process. Subsequently, we transcribed each interview and cross-referenced it with the original recording to assess reliability. In order to maintain consistency in the meaning conveyed through language choices by the respondents, we implemented a translation-backed-translation procedure, following the guidelines established by Brislin (Citation1970). Three of our co-authors, proficient in both Urdu and English, played the role of experts in this process.

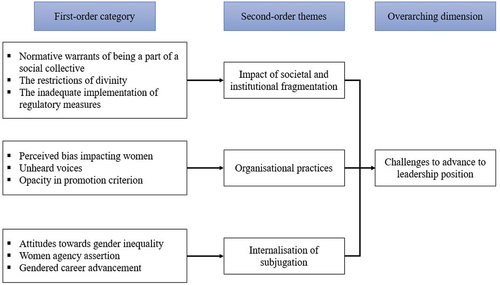

The analysis of the data followed Gioia et al. (Citation2013) three-stage process for theory development. This method entails progressing from first-order data themes to second-order themes, culminating in overarching dimensions. Our approach began with the identification of first-order data themes, achieved through a meticulous review of interview transcripts and attentive listening to tape recordings. Open coding was employed to establish an initial set of first-order concepts for classifying the data (Magnani and Gioia Citation2023). Despite maintaining an open mind throughout the analysis, sub-categories and main categories began to emerge early on. The open coding procedure facilitated the identification and categorisation of initial concepts, with multiple readings of interview transcripts ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the subtleties within the responses. At the institutional level, categories emerged related to normative warrants of being part of a social collective and the restriction of divinity. Organizational level barriers included the absence of regulatory enforcement and issues related to unheard voices in the workforce. At the individual level, our results focused on subjugated behaviour in the workplace.

In the second stage of our study, axial coding (Magnani and Gioia Citation2023) was applied to further develop and integrate findings from stage 1. The overarching goal was to construct theoretical labels in accordance with Gioia et al. (Citation2013) guidelines. Through a systematic review and revisiting of the data, key challenges faced by women in ascending the leadership hierarchy within HEIs were identified. Our exploration centred on women’s experiences with social norms, the predominantly male-dominated workforce, work-family conflicts, as well as religious and legal obstacles. Second-order themes emerged and were distilled further into five aggregate themes, serving as the central, overarching dimensions of the study. We elucidate our approach to conceptualising the empirical material, progressing from the raw interviewee statements to the identification of second-order themes. Subsequently, we consolidate these second-order themes, leveraging the most compelling evidence to construct overarching theoretical dimensions. This methodological progression aligns with Pratt (Citation2009) framework, emphasising the selection of robust evidence to vividly illustrate the prevalence of key themes, thereby enriching the theoretical underpinnings of our study. Prominent data excerpts were coded to capture essential elements of institutional work as a priori themes, expediting the initial coding phase and ensuring the inclusion of themes highlighted in the literature (D. Gioia Citation2021). We sought similarities and differences among the first-order concepts, engaging in discussions to elucidate their interrelated nature. This collaborative exploration enhanced the development of new theoretical insights. The first-order concepts were systematically organised into broader conceptual categories, forming the foundation for a set of original second-order themes.

Finally, in the third stage, our attention shifted towards delving into the relationships between second-order themes to establish overarching patterns, a process in line with the methodology proposed by Corley and Gioia (Citation2004). This involved the formulation of aggregate dimensions, such as ‘cultural disruption’ and ‘internalisation of subjugation’, with a careful delineation of the interconnections between these dimensions, as per the guidance provided by Cardador et al. (Citation2022). provides an overview of the three stages comprising the data analysis process. This phase is particularly significant as it allows researchers to expand the analysis of categories and relationships, offering valuable insights beyond the immediate study that can benefit other researchers. To elucidate, this stage encompassed the following key steps: (a) Scrutinizing each participant’s response individually. (b) Evaluating the consistency of responses across all participants. (c) Deriving theoretically explanatory categories from the emergent codes. (d) Repeatedly reviewing and refining various coding approaches until the data structure reached a state of stability. (e) Subsequently abstracting these emergent codes into higher-order aggregate categories. In accordance with the framework outlined by Gioia et al. (Citation2013), our analysis yielded categories that were directly relevant to our specific research inquiry. Subsequently, sub-categories emerged, including the role of culture and society, the prevalence of a male-dominated workforce, and the internalisation of subjugation. The outcome of this rigorous analysis is visually represented in , illustrating the resulting data structure.

In accordance with the methodological recommendations put forth by Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985), our study rigorously adhered to a threefold approach aimed at ensuring the utmost trustworthiness of our dataset. Initially, three of the authors possess extensive first-hand experience in Pakistani HEIs, having dedicated a minimum of ten years to active involvement in the region. This commitment involved immersing ourselves in the rich tapestry of Pakistani culture. This intensive engagement facilitated what Beigi et al. (Citation2017) termed as prolonged engagement, enabling us to cultivate a profound understanding of Pakistan’s culture, customs, and codes of conduct. As a second measure to enhance the credibility of our findings, we undertook a process of peer debriefing in accordance with Beigi et al. (Citation2017). Two colleagues, not directly associated with this study but well-versed in qualitative research are gender in developing countries, were invited to review the emerging themes. Their insightful feedback on our overall findings provided a valuable external perspective, aligning with the practice advocated by (Corley and Gioia, Citation2004). These peers, played a crucial role in vetting our ideas and ensuring the robustness of our interpretations. For the third step, we enlisted the expertise of an experienced qualitative researcher to conduct a comprehensive audit of our empirical data. This involved a meticulous examination of the interview protocol, our coding process, and random samples of interview transcripts. The purpose was to evaluate the reasonableness of the conclusions drawn from our analysis, aligning with the methodological standards set by Corley and Gioia (Citation2004). These methodological safeguards collectively contribute to the rigour and trustworthiness of our research, ensuring a robust foundation for the interpretation of our findings discussed in the next section.

Findings

The interviewees extensively discussed the conspicuous absence of women in decision-making roles within the universities under examination. Our finding primarily comprises of three subsections namely, impact of patriarchal norms and religious fragmentation, organisational construction of leadership articulation in terms of gender, and the internalisation of subjugation. More specifically, in terms internalisation of subjugation, we analyse attitudes towards gender inequality, agency assertion and gendered career advancement strategies. The internalisation of cultural values serves as a normative warrant, overshadowing organisational perspectives on women’s career choices and advancement. Societal and cultural norms, essential in shaping the subjectivities of women in Pakistan, prioritise obligations over collective feminine considerations, even amidst gendered exclusions. As a result, individuals adhere to these ingrained norms without explicit consent, indicating the internalisation of subjugation infused by cultural norms and leading to behavioural adjustments. Our interviews with women faculty members affirm the widespread existence of this phenomenon.

Impact of societal and institutional fragmentation

Within the broader cultural, religious, and institutional domains, female faculty members in Pakistan consistently recounted encountering substantial impediments to career advancement. Cultural expectations, constraints imposed by religious norms, and the inadequate implementation of governmental policies were prominently identified as major obstacles within this context.

Normative warrants of being a part of a societal collective

In a collectivistic society like Pakistan, cultural and societal factors wield significant influence. Participants from all the universities uniformly expressed a common viewpoint regarding the prevailing impact of traditional gender roles, which predominantly prescribe societal expectations for women, highlighting their primary roles as wives and mothers. Pakistani women also shared narratives recounting instances of community members protesting against their pursuit of professional careers. Such opposition was framed as a perceived violation of entrenched traditional gender roles, deemed sacred by societal norms. The career decisions, workplace progression, and career choices of women are intricately intertwined with meeting the societal obligations dictated by the collectivistic culture. For example, the respondents in our study said.

In higher education, women often outperform men. However, after graduation, many women, upon marriage, face constraints that limit their professional engagement, leading to an automatic exit from the workforce. (ASP3).

Women are predominantly permitted to work in specific professions, such as teaching, often dictated by societal expectations, with the constraint of being home by 2:00 pm to prepare meals before their husbands return. Opportunities for women in the corporate world remain limited.

The significance of cultural and societal values in assigning gender-based social roles is underscored by insights (Koburtay, Abuhussein, and Sidani Citation2023). Our analysis provides a nuanced perspective, highlighting the creation of normative warrants that reinforce adherence to societal codes. The women we interviewed stressed the societal expectations they must meet, with one common South Asian expectation being the traditional responsibility of women to manage household tasks (Habiba, Ali, and Ashfaq Citation2016), often alongside full-time employment. The onus of everyday life in a household, including the chores, is on women. Our respondents reaffirmed this and said:

As a married woman, navigating the intersection of cultural and family norms becomes a constant challenge, requiring a delicate balance between familial responsibilities and work commitments. The inherent obligation to manage all aspects of life is a demanding reality. (AM5).

When faced with the choice between my career and family, I would unequivocally choose the latter. However, I am reluctant to relinquish my job, as it aligns with my passion. The reality is that sacrifices are inevitable at every stage of life. (ASP9).

Women in the study exhibited a tendency to prioritise domestic duties over their professional commitments. The struggle with work-family conflicts is evident as they navigate multiple roles simultaneously, often leading to career sacrifices. This underscores the influential role of societal expectations as a compelling institutional force impeding women’s career advancement. Moreover, the interviews unanimously emphasise the substantial role assigned to Pakistani women within the family. Yet, societal expectations for women to seamlessly fulfil both domestic responsibilities and professional roles pose a significant hindrance to their career progression. This is also apparent in another participant’s response.

Women continue to grapple with distinct challenges, juggling multiple roles as a daughter, wife, mother, daughter-in-law, and a working professional. The expectation is to skilfully navigate and manage both personal relationships and work responsibilities. (HW1).

Overall, the interviewees frequently cite family and societal influences as primary factors shaping their prioritisation of family responsibilities, both immediate and extended, over their careers. This prioritisation inevitably impacts their career prospects and often leads to a diminished interest in pursuing leadership positions within HEIs.

The restrictions of divinity

Muslim women are often depicted as submissive, passive, and subject to dominance within a confluence of Islamic values in a patriarchal society, there is a growing body of knowledge challenging the mainstream narrative that attributes Muslim women’s suppression solely to Islam (Tlaiss and McAdam Citation2023). In Pakistan, being an Islamic State where religion plays a pivotal role in governance, women find themselves disadvantaged in active workplace participation. This disadvantage is especially pronounced in networking and engagement in training and development programmes, where women frequently encounter additional challenges. The following quotes underscore these perspectives.

… … in my opinion, most men at universities do not feel comfortable sitting with women colleagues due to social imbalance or religious beliefs, which are based on sheer misconceptions. (ASP8).

The interviewees were aware of what Islam says about the rights of men and women and their privileges, as another participant asserted,

Islam has similar moral standards for women and men, but the women have to observe them all, in kind, as compared to men. (LT4).

In the context of a woman occupying a leadership position, it is crucial to acknowledge that she may need to engage with male subordinates, especially in faculties predominantly comprised of men. This interaction has the potential to disrupt the established practice of sex segregation in Muslim societies, thereby restricting the career roles available to women to those with minimal such interaction. An unintended consequence of this dynamic may be some men feeling threatened when led by a woman, as it challenges established religious norms, where compliance with women’s directives can be perceived as a threat to male honour. The prevailing patterns of gendered power ultimately perpetuate the notion that women lack the capabilities to assume leadership positions at HEIs. Nevertheless, in contrast to women in previous categories, some describe working at universities as a rewarding and empowering activity. For instance, one woman emphasises:

While gender-related issues may exist within the university, I have personally not encountered any such incidents in my department. I’ve never experienced differential treatment based on my gender. It’s essential to acknowledge that there are flaws in the system, but these issues are faced by male faculty members as well. (AM2).

Even with a higher representation of women in the workplace, structural and religious impediments remain unchallenged, thus perpetuating the status quo.

The inadequate implementation of regulatory measures

In our investigation, the female participants illuminate various instances where legislative measures aimed at fostering women’s participation faltered in actual implementation within organisational frameworks, notably concerning issues of equality and promotional procedures. A respondent, serving as a member of an organisational committee within her department, articulated the view that the inclusion of women in such committees often transpires as a token appointment, serving primarily to espouse the discourse of diversity without effecting substantive change.

I was part of a search committee in my university just to fulfil the requirement of having a woman onboard. I personally know that women do not willingly enter such roles as they are forced to be part of the system, but their recognition is limited. (ASP1).

Additionally, the women indicate various organisational-level practices that are against legislation and processes. While some women fight against the oppression, others do not. Such practices are well-explained by the following quote.

As women faculty, we contemplate many fears in the form of threats, scandals, harassment, and sympathy. The best choice for every woman should be to step forward. (ASP1).

A woman faculty member also mentions the process of promotion that is lopsided even though a policy is in place:

I faced discrimination based on merit and transparency during the selection process. As time passed, I realized these practices are deeply rooted in our system. I’ve learned to navigate and move forward despite these challenges. (LT3).

Additionally, the women indicate various university-level practices that are against legislation and processes. One interviewee said:

As per the university policy, I was entitled to study leave. However, I had to advocate for this right by challenging the dominance of specific individuals through legal arguments and presenting evidence. (LT1).

The predominance of men in the workforce leads to a variety of problems. In Pakistan, this issue is not just symbolic but literal, as highlighted by another woman.

It seems our minds are conditioned to perpetuate patriarchy. For example, if a husband earns a certain amount, women might feel inclined to maintain their pay at a similar or lower level. The dynamics of power could shift if women were to earn more.

Organisational practices

Three main organisational level barriers emerged from the interviews including perceived biases impacting women faculty, unheard women voices and opacity in promotion criteria.

Perceived biases impacting women faculty

When aiming for promotions to senior positions, a common them emerged, emphasising the necessity to emulate male managers. The challenge was not about gender itself, but rather the demand to exhibit traits traditionally associated with masculinity and assertiveness. A feminine leadership style was deemed unsuitable for the competitive nature of the organisation. However, many women faced difficulties in adopting these traits while also striving to maintain a sense of authenticity. Most of the time, they were unwelcome, and their views were undermined, as the following quote depicts.

In HEIs, upper administrative roles are predominantly held by men who exhibit a preference for male candidates when faced with equally qualified men and women. Women often yield to the prevailing masculine culture in the workplace without even engaging in fair competition, solely based on their gender, which is a particularly troubling and unjustifiable reason. (LT5).

Implicit biases frequently led to the side-lining of women for senior roles and exclusion from challenging tasks crucial for their career advancement. This is evident by the following response of one of the professors being interviewed.

There’s a prevailing perception that men excel at decision-making, even if not explicitly stated. I personally sense this, particularly when comparing my tasks with those of my male colleague. I notice a disparity in the institutional support I receive, as my boss tends to assign more thought-intensive tasks to my male colleague.

The male-dominated workforce provides a fertile ground for the tendency of men to stick to the gendered institution in organisational practices. This can also be related to the old boy network. Access to the network means word-of-mouth recommendations and fluidity in communicating capabilities to promote career advancement (Lalanne and Seabright Citation2016), which at the same time excludes women and other marginalised groups who are outside of this network. This would further reinforce gender inequalities in the workplace. One participant reports.

Women often find themselves on the outskirts of the old boy network. They are side-lined with seemingly illogical reasons, such as training being conducted far from local stations. Despite these challenges, I personally value and enjoy participating in such training sessions and workshops.

In summary, while the stories shared by women faculty indicate a higher prevalence of implicit bias in the form of double standards, these narratives also bring to light the existence of both implicit and explicit biases against female faculty.

Unheard women voices

The women indicated that their presence, even in leadership positions, is ignored, and their opinions or participation, is often neglected. This is because many of the women interviewed believe they felt like an outsider in top-level meetings. A respondent explained the systemic constraints for women in academia.

We exist within a system that is favourably inclined towards males. The legislators in universities are predominantly men, and they often overlook issues specific to women. Rules seem to be absent for men, with the enforcement and implementation of regulations disproportionately impacting women faculty. Flexible timings, intended to benefit men more than women, are often observed. Men tend to fulfil a significant portion of their domestic responsibilities during work hours, leveraging strong networks that offer them secure havens in the workplace. (ACP1).

This suggests that the institutionalised gendered culture perpetuates in HEIs (Cook and Glass Citation2014), portrayed by the absence of women in higher echelon in universities. Such mindset further affects the diversity at the workplace as some male workers consider women as threat, as one of the participants reports.

Men like to be dominant but, at the same administrative level men perceive women as a threat on basis of their knowledge and skills. Sometimes, they do not want to work under a woman. (ASP7).

Even when women hold a senior position, their peers will not take them seriously, as can be seen in the quote below.

As a HOD (Head of Department), when I interact with other HODs, who are men, their views always get more spotlight. During meetings men do not like to invite women of executive position because they consider them with less cognitive ability as well as bad decision-making power. (ASP7).

This quote highlights that leadership is all men domain, and there are gendered practices that manifest in the form of talk, action, interaction, and performance throughout the organisational regimes. Similarly, Masood (Citation2019) also shows that women in senior positions would not integrate well among their peers as there are activities that are only attended by men. Such regimes seemingly result in taking the opinions of women at executive positions lightly without any sensitisation towards them. In line with this, women faculty members state.

I sometimes feel my opinions are being overlooked in the board meeting that we had. I would say something in a meeting, and no one will give any ears. Four seats down the row, a man talks about the same thing and suddenly everyone thinks it’s a great idea. (ASP5).

The system is run by men, and they do not try to address the problems faced by the women.

These quotes narrate how women’s lack of voice in decision-making positions persists and the depth of the issues they face in top-level meetings.

Opacity in promotion criteria

Interviewees in the study on participation acknowledged the absence of objective criteria for senior roles as a significant barrier to their career progression at the universities. This situation resulted in promotions favouring individuals with access to influential organisational networks.

It took three attempts for me to become the Department Head. In the first two instances, someone else, usually a man, was chosen, and it remains unclear if gender played a role. Despite consistently being the more qualified candidate in terms of knowledge and experience, the ambiguous promotion criteria, such as a longer or closer acquaintance with the Dean, seemed to overshadow merit. Only after the initial selections faltered did the Dean recognise my capabilities and choose me based on merit, as the individual with superior knowledge and experience.

Furthermore, the demand for frequent travel not only consumes time that could be spent with the family but also introduces added anxiety for women, who still bear the responsibility of managing domestic affairs. A participant highlighted the challenges of her profession, requiring international travel, especially during her children’s formative years. The participant expressed that travel heightened anxiety, as she felt compelled to plan and prepare family meals in advance before her trips. Consequently, when presented with the option, she strives to limit their career progression. However, she acknowledged the inherent difficulty in achieving this goal, a sentiment echoed by the following women who reflects:

Maintaining a balance between caring for my young ones, my husband, his parents, and pursuing my career is an exceptionally challenging task. However, I consciously prioritize what is acceptable for me, leaning towards my career. Although it might take a longer time to reach my desired position, I find solace in the fact that it allows me to spend precious time with my children while they are young. I recognize that this phase is irreplaceable, and I am willing to make the trade-off for these invaluable moments.

I harbour doubts about the possibility of further promotion within this university. It seems likely that I may retire in my current position. While I desire to be promoted, there comes a point where interpersonal relationships become pivotal, and navigating this terrain becomes intricate. The organizational landscape, being heavily male dominated, adds another layer of complexity to this challenge.

Overall, the lack of clear criteria for promotions and the prevalent male homophily culture within the university marginalised female managers, relegating them to mere tokens. This compounded the existing biases against them, erecting formidable barriers to their career progression.

Internalisation of subjugation

The social and religious prescriptions, many times based on contorted interpretation of Islam and power structures, serve as normative warrants for male hegemony (McCarthy, Soundararajan, and Taylor Citation2020), which is further augmented by the internalisation of the norms by women. The production and reproduction of discourses shape regimes of truth within which women normalise the male hegemony, and sometimes promote it. For example, one of the respondents in our study said,

The predominant factor fuelling the underrepresentation of women in top-tier positions within higher education stems from the psychological challenges associated with being a woman in Pakistan. Frequently, women opt not to engage in competitive scenarios with their male counterparts, solely on account of their gender, a factor deemed highly detrimental to their professional advancement.

The respondent’s account, in its most general sense, refers to the nexus between individual self-governance such as behaviour or conduct of women, and the moral warrants produced by discursive practices realised through production and reproduction of moral warrant through discourses. The prescriptive power of such warrants results in women becoming docile subjects who not only comply with inhibiting prescriptions but also popularise and ceremonise such practices. The women incriminate themselves and their behaviour in being modest and cautious, which ultimately hamper their perception towards career advancement. For instance, one of the interviewees revealed such tendencies as follows.

I want to grow but I do not have enough confidence to express myself. I want my superiors to recognise my effort and promote me accordingly. (ACP2).

A significant challenge hindering women from advocating for their growth opportunities in the workplace is their perceived lack of confidence. This modesty is further exacerbated by sociocultural norms that legitimise gendered practices. The respondents often refrain from applying for promotions, showcasing a self-imposed barrier. This underscores the institutional dynamics where internalised subordination and the persistent perception of women in a special piety status prevail. However, the individual’s actions here are normatively embedded in the logics of collective identity, which is highly gendered and self-responsibility of reinstating that logic.

Success, in my opinion, stems from consistency, hard work, sincerity, and overall dedication. To gain recognition in a predominantly male-driven system, I believe that women need to cultivate psychological strength. It’s essential for them to view themselves as individuals rather than solely through the lens of their gender when in the workplace. Respecting oneself as a person is crucial; this means avoiding the exploitation of others by leveraging one’s status as a woman and, at the same time, not allowing anyone to exploit them based on their gender.

Another participant who was at a leadership position painfully asserted.

Women who reach decision making positions do not stay true to their nature. As a leader, they need to highlight the problems faced by others rather than saying that I have reached this position because I never considered myself a woman. My parents brought me up like a boy. This is normal narrative that we hear from the women at the top.

This respondent is demonstrating her leadership experiences to further understand gendered practices. She elaborates on the historicity of the gender as institution, where losing the softness behind is considered as the only way to reach the top positions. This suggest that male-dominant workplace led women to consider themselves as weak whereby only gender that can progress to leadership position is being a male. Furthermore, according to one of the participants, cohesion among women decreases when there are more women at leadership positions:

There is a strong bond among women with a small group, but such ties gradually diminish with the increase in number. It may be due to professional jealousy or many factors.

These quotes provide a very interesting view regarding how other women see leaders of their own kind. These views are primarily informed by the ideologies and social structures, where women subservience is considered strongest when they associate themselves with male-like characteristics (as mentioned in the previous quote) or prefer to have more males in top-level meetings. These are novel institutionalised obstacles to gender equality in academic institutions.

The expectations to fulfil obligations at home and at work create a struggle for women in Pakistan to achieve work-life balance. The study by Naz et al. (Citation2017) concludes that when women find it hard to have time for themselves, this will effectively have a toll on their mental and physical wellbeing. A significant number of the participants shared that the major challenge for them has been finding a work-life balance between domestic and career responsibilities. A participant shared how managing undergraduate programmes had forced her to work late nights and during weekends. This has resulted in difficulty in living a healthy lifestyle (PF5).

Personal commitments also limit the amount of time for the women to interact in informal or social activities. Familial commitments are usually more prioritised. This is apparent by one participant.

Due to busy schedule, I could not find time to interact with my colleagues of the same university. I have long and tough working hours; have to balance family and work life, long travelling so I could not find time for networking.

This shows the overall narratives of women interviewed who capture the pressures they felt to conform to the traditional gendered institution and mould their focus more towards the parental self. Additionally, the women studied derive value from having quality relationships with their children. A common theme in the women’s responses was the description that they would attempt to go into decision-making positions and invest further in their careers with children being older. Another interviewee admits that women tend to be more emotional, and the issues faced by them will add to the pressure:

Being a woman, I consider that women have to sacrifice their emotions at every stage of life. women are bit emotional, and majority of their decisions are taken emotionally … . The best choice for every woman should be to step forward, I got married at early stage of life, but I continue my journey, as a result today I am here [assistant professor position]. Women are bounded by the society in the name of norms, culture, and other taboo. To reach a certain level, she has to face more psychological pressure than men.

These quotes highlight the discriminatory sociocultural practices and lack of supportive organisational policies that result in having an impact on women’s health.

Discussion

Our examination of the challenges faced by women striving for leadership positions underscores the significant impact of Pakistan’s socio-cultural and economic environment on the progression of women’s careers. Our conceptual framework sheds light on the complex interplay among three crucial factors: institutional, organisational, and individual dynamics. We aim to understand how institutional and organisational elements intersect with women’s perspectives, resulting in the internalisation of oppression. HRD scholars argue that careers are deeply intertwined with their sociocultural context, influenced by socially constructed notions (Abadi, Dirani, and Dena Rezaei Citation2022; Garavan et al. Citation2018; Scully-Russ and Torraco Citation2020). This study’s findings highlight the interconnectedness of macro and micro-level analyses in elucidating the managerial careers of Pakistani women. While these careers are individually experienced and shaped, they are also influenced by entrenched social and cultural norms. We examine the dynamic interaction of institutions, organisational frameworks, and individual agency, all within the context of a developing country’s institutional landscape.

The perpetuation of male dominance in Pakistan is exacerbated by societal and religious justifications, often rooted in a distorted interpretation of Islam and power dynamics (Ali and Rasheed, Citation2021; Ali and Syed Citation2017). Women internalising these norms further exacerbates the issue, resulting in their passive acceptance of restrictive norms and, in some cases, active promotion of such practices. The intersection of patriarchy and religion is a multifaceted issue extensively explored by scholars (Avishai, Jafar, and Rinaldo Citation2015; Ghafournia Citation2017; Perales and Bouma Citation2019). Religious interpretations are frequently used to justify gender inequality, with religion serving as a barrier for women in various spheres. In Pakistan, patriarchy and religion intersect in various ways, utilising religious interpretations to uphold gender-based practices. The study argues that patriarchal norms and religious interpretations present contextual challenges hindering women’s advancement in academia. The persistence of patriarchy, particularly in developing nations, is reinforced by societal pressures, while inadequate regulatory mechanisms in Pakistan allow patriarchal and religious practices to persist.

Despite legislative frameworks promoting gender equality in Pakistan, weak regulatory and enforcement mechanisms often hinder practical implementation (Shaheed Citation2010). Cultural and social norms deeply embed these practices, posing obstacles for educated women, especially those in higher education institutions, to challenge them. Despite laws against them, honour killings continue, highlighting the deficiencies in enforcement and prosecution. The effective enforcement of gender equality laws remains a significant challenge in developing countries, impeding the realisation of gender parity.

At the organisational level, gender inequality in the workplace often originates from broader institutional factors. Social stereotypes create barriers, necessitating additional effort from women to ensure their voices are heard and decisions are implemented. Gender-biased selection processes hinder women’s advancement to senior positions, excluding them from leadership roles. Our research aligns with previous studies, indicating that assertive women may not always be valued, requiring them to adapt their communication styles for effective task completion.

Existing research in HRD emphasises the crucial role of advancement programmes, such as leadership training, in creating supportive environments that foster self-assurance and adaptability (Abadi, Dirani, and Dena Rezaei Citation2022, Barhate et al., Citation2021; Dirani and Silva Hamie Citation2017; Tlaiss and Dirani Citation2015). Insufficient skills and training leave women susceptible to gender stereotypes, falsely implying their unsuitability for leadership positions due to perceived nurturing qualities. Comprehensive training, both formal and informal, is essential to prepare women for leadership roles (Yesilirmak, Tayfur Ekmekci, and Bayhan Karapinar Citation2023). A prevailing male-dominated culture within organisations exacerbates challenges for women, leading to underrepresentation in senior leadership, gender pay disparities, and limited presence in certain academic fields. Insufficient support and mentoring compound these challenges, making career advancement more difficult for women in academia.

Furthermore, women often internalise institutionalised inequalities, with institutional structures and male-dominated cultures becoming integral aspects of their identities as female academics. Discrimination often originates in familial environments, where favouritism towards male offspring is evident (Malik and Courtney, Citation2011). This bias persists throughout a woman’s life, relegating her to a subordinate position within societal structures. Systematic exclusion from participatory roles in decision-making processes and inequitable resource allocation exacerbate these disparities. Importantly, this bias hinders the development of self-assurance in women’s abilities. Girls are consequently assigned passive and subordinate roles, with the educational system inadvertently perpetuating these prejudicial norms and reinforcing their societal status. The cumulative effect of these deeply ingrained cultural influences impedes the realisation of women’s full potential, limiting opportunities to cultivate their self-esteem and resulting in diminished self-worth.

Our analysis reveals that some women internalise institutional structures and organisational practices, perpetuating gender inequalities and a male-dominated culture, which become integral to their identities as academics. Normalized logics with normative warrants, rooted in culture and religion, are propagated through regimes of truth produced via discourses to justify practices that may otherwise be deemed unacceptable, in the pursuit of a ‘greater good’ rearticulated within supposedly unchallengeable and accepted rationality. This suggests that the subordination of women in academic institutions stems from power relations, whereby social structures become ingrained in individuals’ sense of self. The intricate interplay of institutional and organisational factors is evident in women’s agency and their reluctance to address gender inequalities. For example, patriarchal interpretations of religious and cultural norms prevalent in the Indian subcontinent reinforce gender stereotypes, positioning women as secondary citizens (Ali and Syed Citation2017). Even when women have access to employment opportunities, institutional constraints such as limited transportation options, domestic responsibilities, and childcare obligations restrict their career choices (Roomi and Harrison Citation2010). Moreover, traditional religious beliefs are prevalent in such institutional settings, with religious leaders promoting the idea that it is inappropriate for women to work outside the home and interact with unfamiliar men (Ellick Citation2010). Consequently, women employed in these environments often find themselves in a constrictive setting, lacking the empowerment necessary to engage in decision-making processes.

Implications for future higher education research

While our study makes a meaningful contribution for research in academia, it is essential to acknowledge its limitations. The interviews were conducted exclusively within universities situated in a conservative region, and we recognise that women in different geographic areas may have distinct experiences regarding work and leadership opportunities. To address this limitation, we recommend that future research endeavours incorporate diverse perspectives by including women from both large urban centres and smaller cities within higher education. This would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the nuanced experiences of women in various settings.

One of the paramount contributions of our paper lies in exploring the internalisation of subjugation, emphasising the influence of situated learning experiences shaped by patriarchy and other pertinent factors. To further advance this aspect, future studies could dedicate focused attention and develop a more in-depth literature review, specifically delving into the nuanced dynamics of internalisation and its intersection with contextual elements within academia. Such a targeted exploration would undoubtedly enhance our collective understanding of the complexities surrounding the internalisation of subjugation in diverse settings.

Finally, while our study endeavours to illuminate gender-related practices in academia, we recognise the broader prevalence of these issues across various sectors within developing countries. It’s important to acknowledge that our analysis is focused and constrained in scope. We advocate for future studies to engage in more detailed investigations across diverse organisational settings, leveraging ethnographic observations to enrich our comprehension of the wider implications of gender-related challenges. Incorporating ethnographic data is anticipated to introduce a heightened level of subjectivity for researchers, thereby yielding novel and insightful perspectives.

Implications for future HRD research

Our findings provide an avenue for prospective researchers to explore the intricacies of women’s career development across diverse global societal and cultural contexts. While historical theories have acknowledged societal expectations placed on women, encompassing roles such as childbirth and domestic responsibilities, there exists a noticeable gap in comprehensive theories elucidating the challenges faced by Pakistani women in making career choices and progressing in their careers. To develop a more inclusive theoretical framework, HRD researchers should expand their investigations by integrating sociocultural factors into their research inquiries. Such a holistic approach would contribute to the development of a comprehensive theory explicating how individuals navigate career-related decisions.

As demonstrated by our research findings, study participants share distinct and unique career progression experiences, often grappling with a pervasive sense of limited agency in decision-making, significantly influenced by their socio-cultural milieu. Recognizing the formidable challenges faced by Pakistani women navigating a vastly divergent socio-cultural landscape compared to their counterparts in Western countries is crucial. HRD researchers can enrich their research by incorporating theories and insights from diverse disciplines, such as sociology, to examine the career-related experiences of individuals with diminished autonomy and influence over their career trajectories.

Moreover, our analysis underscores the critical importance of institutional diversity, particularly within decision-making bodies, in enhancing the representation of women in senior leadership roles. Diversity not only increases the likelihood of women ascending to leadership positions but also empowers them to assert their agency. Future HRD studies could extend our research by exploring whether diversity among decision-makers similarly impacts the advancement of other underrepresented leaders, including individuals from different gender backgrounds and ethnic minorities. For example, our findings suggest that some women in leadership positions perceive that success in a patriarchal and religious society that values stereotypically male attributes necessitates neglecting women’s inherent leadership capabilities.

Finally, social norms, primarily rooted in a distorted interpretation of Islam and power structures reinforcing male dominance (McCarthy, Soundararajan, and Taylor Citation2020), gain even greater strength when some women internalise these norms. Further research delving into how women internalise subjugation through the intersection of various institutional and organisational forces is essential for advancing the HRD research agenda.

Implications for HRD practice

The study underscores the imperative for policymakers, academics, and practitioners to cultivate a comprehensive and contextual understanding of the myriad issues and challenges confronting women in HEIs. Bridging the gap between governmental policies and actual practices necessitates the development a diverse workplace. The multilevel approach adopted in this study can potentially guide policymakers and managers in both public and private sector organisations to comprehend a spectrum of issues. This approach is equally valuable for stakeholders, including academics and human resource practitioners, facilitating a nuanced understanding of gender equality policies in diverse societies and organisations within the framework of HRD in HEIs.

The study underscores that attributing sole responsibility to organisations for diversity policies may prove inadequate, as the practices of diversity management and gender equality are intricately linked to both macro-societal and micro-individual issues. Particularly in the context of Pakistan, policymakers should concentrate on multi-level challenges confronting women to enhance comprehension and address the intricacies of female economic activity and employment within the broader framework of HRD policies and practices in higher education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abadi, M., K. M. Dirani, and F. Dena Rezaei. 2022. “Women in Leadership: A Systematic Literature Review of Middle Eastern Women managers’ Careers from NHRD and Institutional Theory Perspectives.” Human Resource Development International 25 (1): 19–39.

- Al-Ahmadi, H. 2011. “Challenges Facing Women Leaders in Saudi Arabia.” Human Resource Development International 14 (2): 149–166.

- Aldossari, M., and T. Calvard. 2022. “The Politics and Ethics of Resistance, Feminism and Gender Equality in Saudi Arabian Organizations.” Journal of Business Ethics 181 (4): 873–890.

- Ali, F. 2013. “A Multi‐Level Perspective on Equal Employment Opportunity for Women in Pakistan.” Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 32 (3): 289–309.

- Ali, R., and A. Rasheed 2021. “Women Leaders in Pakistani Academia: Challenges and Opportunities.” Asian Journal of Women’s Studies 27 (2): 208–231.

- Ali, F., and J. Syed. 2017. “From Rhetoric to Reality: A Multilevel Analysis of Gender Equality in Pakistani Organizations.” Gender, Work, & Organization 24 (5): 472–486.

- Alvesson, M., and Y. Due Billing. 2009. Understanding Gender and Organizations. London: Sage Publications.

- Ashraf, M. J., and D. Pianezzi. 2023. “Gender, M-Money, and Sexuality: An Exploration into the Relational Work of Pakistani Khwajasiras.” Work, Employment and Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/09500170231188672.

- Avishai, O., A. Jafar, and R. Rinaldo. 2015. “A gender lens on religion.” Gender & Society 29 (1): 5–25.

- Barhate, B., M. Hirudayaraj, K. Dirani, R. Barhate, and M. Abadi. 2021. “Career Disruptions of Married Women in India: An Exploratory Investigation.” Human Resource Development International 24 (4): 401–424.

- Battilana, J., and T. D’aunno. 2009. “Institutional Work and the Paradox of Embedded Agency.” Institutional Work: Actors and Agency in Institutional Studies of Organizations 31:58. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511596605.002.

- Beigi, M., J. Wang, and M. B. Arthur. 2017. “Work–Family Interface in the Context of Career Success: A Qualitative Inquiry.” Human Relations 70 (9): 1091–1114.

- Bhatti, A., and R. Ali. 2020. “Gender, Culture and Leadership: Learning from the Experiences of Women Academics in Pakistani Universities.” Journal of Education & Social Sciences 8 (2): 16–32.

- Bierema, L. L. 2020. “HRD Research and Practice After ‘The Great COVID-19 Pause’: The Time Is Now for Bold, Critical, Research.” Human Resource Development International 23 (4): 347–360.

- Bolino, M., D. Long, and W. Turnley. 2016. “Impression Management in Organizations: Critical Questions, Answers, and Areas for Future Research.” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology & Organizational Behavior 3:377–406. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-041015-062337.

- Brislin, R. W. 1970. “Back-Translation for Cross-Cultural Research.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 1 (3): 185–216.