ABSTRACT

While the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement was proliferating in the United States, the movement did not gain similar degrees of support in Taiwan. Instead, on social media there is even a term, ‘Black Self-serve,’ meaning that Black people always use race as an ‘excuse’ to demand whatever they want. Analyzing computer-mediated communication about blackness from the largest bulletin board system in Taiwan – PTT, this article highlights how and why Taiwanese netizens used the term ‘Black self-serve’ to accuse Black people of fighting for rights. Centering cultural processes of racialized vision and division, this article shows that the depreciation of blackness is deeply connected to Taiwanese navigation of its tenuous status along the racial hierarchy, sense of inferiority, colonization experience, cultural alienation, and the image of Black people as accomplices of anti-Asian racism – all are deeply embedded in systemic racism.

Introduction

The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement has attracted massive attention and discussion regarding issues of racial justice and solidarity across different racial groups (Vani et al., Citation2023; White et al., Citation2021). By creating large-scale affiliations and a sense of broader racial solidarity (e.g., between people of color, Native Americans, Latinos, or Asians), more people can come together to fight for shared interests or against racial injustice. Scholars have speculated as to whether anti-Asian racism and the violation of minorities’ rights could trigger a common foundation for anti-racism in its broadest sense and challenge the ideology of white supremacy (Ho, Citation2021; Lee et al., Citation2020).

Meanwhile, research on race and ethnicity has sought to identify challenges to cross-racial coalitions. On one hand, scholars (Espiritu, Citation2016; Yellow Horse et al., Citation2021) have pointed out that every racial group has different experiences with discrimination and perceptions of racism. On the other hand, when examining the barriers to Asian-Black solidarity, research has found the persisting cultural stereotypes and inter-racial tensions and hierarchy between White people, Asian Americans, and Black people (Gonzalez, Citation2022; Kim, Citation1999; Liu, Citation2018).

The challenges to cross-racial solidarity reflect the conflation of cultural understandings of race and biological divisions. For example, studies have examined the different attitudes among Asian Americans and Latino/as toward anti-Black racism or Black Lives Matter (Corral, Citation2020; Yellow Horse et al., Citation2021; Merseth, Citation2018). Beyond the location of the United States, however, discourses of anti-Black racism from a neither a Black nor White perspective remain understudied. For example, when the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement was booming in cities across the United States, the movement did not gain similar degrees of support or attention in Taiwan. There were hardly any solidarity protests or reports about BLM on news media. Instead, on social media Taiwanese netizens were skeptical about the legitimacy of the movement and even used a sarcastic term, ‘Black self-serve,’ meaning that Black people always use race as a convenient claim for entitlements – just like in a self-service restaurant where people can order whatever they want. The term Black self-serve may conflate with BLM yet it reflects Taiwanese netizens’ stereotype of Black people – questioning the legitimacy of the protests as well as perceiving the other group’s cultural characteristics in a specific (negative) way. Examining Taiwanese perception of blackness – a non-US based, and non-Black/White group – is important because it allows us to better understand the complicated relationship between non-white racial groups’ experiences of white supremacy and the continuing legacies of colonialism in its current cultural and psycho-social forms. It also helps evaluate how the racialization process in another context creates challenges to global racial solidarity and brainstorm alternative tactics to establish the relatedness of Black people’s experiences to non-Black/White groups in different countries.

To this end, this article begins with an exploration of the meanings of ‘Black self-serve’ among Taiwanese netizens (rather than Taiwanese Americans). I analyzed 63,293 posts and replies (from July 2013 to November 2021) on the largest bulletin board system in Taiwan, PTT.Footnote1 The posts and replies contain keywords including ‘Black Self-serve,’ ‘Black people,’ ‘Nigger,’ ‘Racial Discrimination,’ ‘Racist,’ and ‘Black Lives Matter/BLM.’ The results show that Taiwanese netizens’ navigation of perceived tenuous status along the racial hierarchy manifests in their online expressions of anti-Black sentiment, which can be seen from their perceptions of Black people as: (1) being over-sensitive about their marginal status; (2) being lazy, hedonistic, and violent – such cultural characteristics are genetically inherent and unchangeable; and (3) having double standards regarding the fair treatment of other groups and themselves.

Echoing racial hierarchy theory (Berry et al., Citation2022; Craig & Lee, Citation2022), this article further presents the online discussion associated with different races (Black people, White people, Latino/as, and Asians) in various domains (socio-economic, physical, intelligence, and cultural attributes) among Taiwanese. Moving biological and cultural racism forward, however, this article highlights that the depreciation of blackness among Taiwanese is deeply connected to how they perceive their position within the established racial hierarchy (through history and cultural experiences, and the influence of Western media portrayals), and distance themselves from Black people/blackness. As part of the ‘Han people’ or ‘Asians,’Footnote2 on one hand, Taiwanese people internalize and reproduce the model minority myth to avoid the ‘courtesy stigma’ (Goffman, Citation1963) associated with ‘self-serve’ Black people, while on the other they also develop justifications to navigate their sense of inferiority (e.g., perceived inferiority to White people in the socio-economic sense, and to Black people in terms of sports, physical attractiveness, and willingness to fight for rights). This seemingly contradictory navigation process and the one-dimensional discussion within the affective online community reinforce the impact of white supremacy and the stereotype of Black people for Taiwanese. It also presents race as simultaneously a source of moral vision (conceptions about another race, themselves, and racial differences between ‘us’ and ‘them’) and division (group differentiation and unequal outcomes as represented in racial hierarchy) (Bourdieu, Citation1990; Gilroy, Citation2004).

Conceptually, this article contributes to the literature on information, communication, and the challenges to global racial solidarity, by highlighting how social media – as a deliberative space for receiving and delivering discussion on race, manifests the intersection of self-perception and anti-blackness in the wake of colonization. It also shows the legacy of racialized ideology, culture, and colonialism entrenched the racialized vision and division on the Internet. To deal with racial antagonism or to dissolve competing racial visions between different groups, I argue that there is a need to systematically examine the roots of cultural conceptions pertaining to race and racism. For all people – although here the focus is on the Taiwanese – the first step is not to debate whose lives matter but is instead to understand the cultural and historical roots of courtesy stigma and establish the relatedness to Black people’s experiences and sense of inferiority to the understanding of systemic racism.

Literature review

Culturalization of biological difference and biologization of cultural difference

Cultural racism refers to the belief that there is a hierarchy of superior and inferior cultures based on biological (‘racial’) difference (Blaut, Citation1992; Bratt, Citation2022). The reason why such racism is labeled ‘cultural’ is because racial discrimination was no longer to be justified by references to biological/racial difference, but instead would involve a hierarchy of better vs. worse cultures among ethnic or racial groups. For example, model minority theory suggests that compared to Black people, White people are more likely to have more favorable views of Asian-Americans, not just for their perceptions of their socio-economic success but also for other cultural elements such as their perceived academic success, Confucianism, work ethics, family commitment, and appreciation of nonviolence (Yu, Citation2006; Xu & Lee, Citation2013).

Although cultural racism has been criticized for replacing biological racism and obscuring structural racism under ‘colorblind’ or ‘post-race’ language (Chou, Citation2008; Feagin & Elias, Citation2013), Bonilla-Silva (Citation2001, Citation2003a) uses the term of ‘biologization of culture’ – one of the important frames of color-blind racism – to explain the difficulty of separating biological and socio-cultural meanings of race. The frames, for example, convey biological racism via culturally-based arguments such as ‘Black people are inborn lazy, violent, or have too many babies’ (Bonilla-Silva, Citation2003b; Nielsen et al., Citation2010), ‘Latinos have not assimilated into mainstream US culture’ (Waters & Jiménez, Citation2005), or ‘Asians are good at Math’ (Shah, Citation2019), among others. To be specific, the biologization of culture suggests that racial minorities’ cultural attribute, like biological difference, is something inherent and unchangeable.

While acknowledging the conflation of biological and cultural racism, I argue that what remains understudied is the cultural and racial position of the people in the racial hierarchy and how they navigate their own (tenuous) status. For example, the experiences of colonization and the influence from racialized rhetoric on social media, gave fuel for internalizing the racialized beliefs and allowed individuals to express less ‘politically correct’ views such as racist remarks in the online context (Chaudhry & Gruzd, Citation2019). Focusing on the mentality and subjectivity of ‘colonized’ subjects, this article highlights the cultural processes of how Taiwanese people have adopted the racialized discourse about Black Americans in the affective online community – PTT.

Race as a source of competing vision and division

Seeing race through either a cultural lens or as based on biological difference suggests that race is a social construct, that can be considered in relation to concepts such as power and ‘us vs. others’ (Brubaker, Citation2006; Gavrielides, Citation2014). Whenever there is power, it always involves differences and social divisions, and race is no exception. As a result, a consequence of race and racism is, in Bourdieu’s (Citation1990) terminology, both a vision and division of the social world.

Visions can be in a competitive relationship between different racial groups and create divisions, such as regarding which groups are superior or inferior in various domains (e.g., socio-economic, physical, intelligence, and cultural attributes). For example, based on ‘relative valorization’ (White people valorizing Asian Americans relative to Black people) and the opposite discourse of ‘civic ostracism’ (White people constructing Asian Americans as ‘foreigners’ and ‘Others’), the dominant group (White people) has positioned Asian Americans as both the model minority and the perpetual foreigner, racializing them as members of a group that is inferior to White people but superior to Black people and as permanently foreign and unassimilable (Kim, Citation1999, Citation2003). Similarly, reflecting one’s position, Asian Americans or Latinos will compare themselves with other reference groups (e.g., White or Black people) and position/reposition themselves in different domains of the racial hierarchy (see for example, Fraga & Perez, Citation2020; Tsunokai et al., Citation2014). Studies also found that cross-racial solidarity is subject to one’s immigration status, the likelihood of perceiving connected fate with other non-white groups, and everyday encounters and interactions between racial groups (Merseth, Citation2018; Shah, Citation2008).

Highlighting race as a source of vision and division, this article presents the cultural and discursive dimensions of racism and their deployment among Taiwanese netizens when constructing ‘others’ and ‘selves’ along the racial lines within the affective online community. I argue that one’s cultural reflection and navigation of racial status are reinforced by the one-dimensional discussion on social media, which reinforce the effects of ‘courtesy stigma’ – stigma by association with stigmatized persons (Goffman, Citation1963). Such effects led Taiwanese to distance themselves from understanding Black people’s experience and instead made quick comments on social media, such as one race is superior than the other. The entrenched racialized vision/division also explains why anti-Asian racism and BLM/anti-Black racism could not find a solidarity narrative on social media, especially when ‘Black people’ is portrayed by news media as a potential physical threat, as a culturally-alien and different ‘other,’ and as a potential accomplice to anti-Asian racism (Keum et al., Citation2024).

The global understanding of Black Lives Matter

Initiated after the extrajudicial killing of Trayvon Martin in 2012, #BlackLivesMatter reached international prominence. It triggered an extensive use of the hashtags #BlackLivesMatter or #BLM on social media in which individuals shared personal reasons regarding why Black Lives Matter and counter-movement sentiments (Garza, Citation2020). Among these personal frames, anti-Black harassment and police violence were often highlighted, while other frames also incorporated the quality of life in the Black community, as well as gender, racial, and LGBTQ + identities (Jackson, Citation2016; Tillery, Citation2019). Different frames (Black Nationalist, Feminist, and LGBTQ + Rights) and the evolution (from the police-citizen interaction to highlighting white supremacy) generated differential effects on the mobilization of African Americans to support the movement (Bonilla & Tillery, Citation2020; Ray et al., Citation2017). As the movement is intentionally intersectional, the communication of different frames and goals reifies contrasting visions of what blackness is and the nature of the movement (Ince et al., Citation2017).

The global diffusion of BLM further raises the issue of how the movement develops and is perceived in other countries (Della Porta et al., Citation2022; Gaines, Citation2022). Studies have found that BLM, as a digitally networked connective action, provides a chance for other countries to resonate with their local struggles such as fighting police violence and decolonial practice on social media (Beaman, Citation2021; Solomon, Citation2023). Yet, reactionary frames that are hostile to movement values can also be found (Shahin et al., Citation2024). This could be due to the mis-portrayals in the media and some who seek to discredit the movement (Hoffman et al., Citation2016). Understanding the discussion and perception of blackness in the non-US context such as Taiwan explains the challenges to cross-racial solidarity with the BLM movement, both online (e.g., the lack of solidarity narratives on social media) and offline (e.g., unwilling to understand and sympathize Black people’s status). This can be productive as the cross-racial perceptions and challenges to global racial solidarity have gone beyond the same geographical location. Exploring Taiwanese netizens’ attitudes about BLM helps us better understand the influence of media portrayals and discussion about another group in a different country and the continuing legacies of colonialism in relation to race.

Data and methods

Dataset description

The data were collected from the largest bulletin board system (BBS) in Taiwan, PTT. It has more than 1.5 million registered users, most of whom are in their 20s to mid-40s. PTT has more than 20,000 discussion boards related to various topics. 20,000 posts with more than 500,000 comments are made daily. The online site is a place where Taiwanese can voice their disapproval of the government, big corporations, and local elites (Tseng et al., Citation2011). They share the most updated news and exchange opinions regarding (local and global) politics and everyday life. Although it is hard to get a full picture in terms of gender, age, education background of the PTT users, the samples collected by some research suggested that the gender distribution of users on PTT is even (slightly skewed toward males), relatively young-aged (in their 30s and 40s). About half of the users had a bachelor’s degree or above, and the other half were college students (Ho et al., Citation2020; Lin & Lu, Citation2011). The BBS culture and the online affective community made PTT a sensational site where fake news and rumors proliferate. The anonymity further led users to express extreme views and to post misogynistic, racist, and anti-immigrant remarks (Ahn, Citation2019; Li & Song, Citation2020).

By using pttR (Liao, Citation2022) and rvest (Wickham, Citation2021), posts, replies, and comments containing the keywords: ‘Black people’ (in Mandarin), ‘BLM,’ ‘Black Lives Matter,’ ‘Nigger’ (in Mandarin), ‘racial discrimination’ (in Mandarin), ‘racist,’ and ‘Black self-serve’ (in Mandarin) between 16 July 2013 and 9 November 2021 were scrapped. After removing all duplicates and missing data, 63,293 rows of data in total were retrieved.

Topic modeling

This study utilizes Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques to conduct textual analysis: latent Dirichlet allocation for topic modeling (Blei et al., Citation2003). With the tremendous increase in the volume and variety of unstructured text documents (e.g., social media data), topic models have been increasingly used to explore hidden thematic structure of text (Li & Song, Citation2020). Topic modeling can help analyze a large collection of text by categorizing them into different recurring themes/topics based on their similarity or closeness (Zvornicanin, Citation2022); it also measures the degree to which each document exhibits those topics. In other words, it is an unsupervised machine learning technique that detects word and phrase patterns within them and automatically clusters word groups and similar expressions that best characterize the textual data. In this study, I used Latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) to determine which terms and phrases are commonly used together to form topics when Taiwanese netizens discussed blackness and BLM on PTT.

To conduct the analysis, the content of every post, reply, and comment in the dataset is broken down into word tokens using the R package JiebaR (Qin & Wu, Citation2019). JiebaR used a Chinese word dictionary to recognize sentences cut into separate Chinese word tokens. Some commonly used words, such as conjunctives or prepositions, were filtered out to allow for a more robust analysis. The list of stop-words used in this analysis was imported from the stop-word dictionary from the R packages JiebaR and Tmcn (Li, Citation2019). In the end, 608,250 word tokens were generated. Another R package, Topicmodels (Grün & Hornik, Citation2011), was used to generate the results.

Sentiment analysis

To understand how Taiwanese netizens perceive the other racial group, in addition to ‘what’ is narrated in their discourse, sentiment analysis helps to capture the emotions and ‘how’ one describes the other groups (Liu, Citation2020). Sentiment analysis is generally carried out by two approaches: machine learning-based and dictionary-based. The machine learning-based approach trains the program to identify positive and negative sentences by supplying a sample of pre-coded training data on what constitutes a positive or negative sentiment. The dictionary-based method uses a sentiment dictionary with opinion words and matches them with the data to determine polarity. This method assigns sentiment scores to the dictionary of words classified as positive, negative, or neutral words (Hardeniya & Borikar, Citation2016). In this article, the dictionary approach was adopted to enhance a more defined and accurate sentiment evaluation.

The word tokens were matched with the National Taiwan University Sentiment Dictionary (NTUSD) developed by Natural Language Processing and Sentiment Analysis Lab (NLPSA) to determine whether each word token expresses a positive or negative sentiment.Footnote3 Among 608,250 word tokens, NTUSD detected the sentiment of 32,635 word tokens in total, with 17,689 words containing negative sentiment (54%) and 14,946 containing positive sentiment (46%).

Results

Text analysis

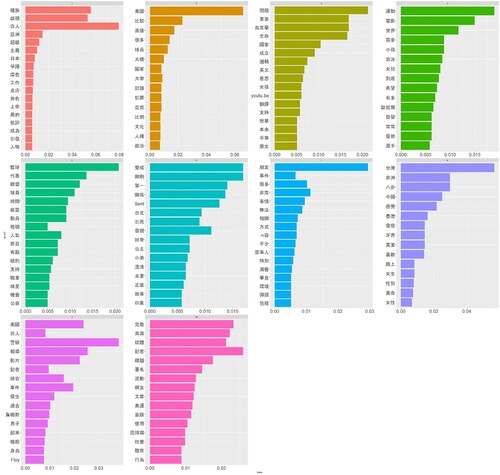

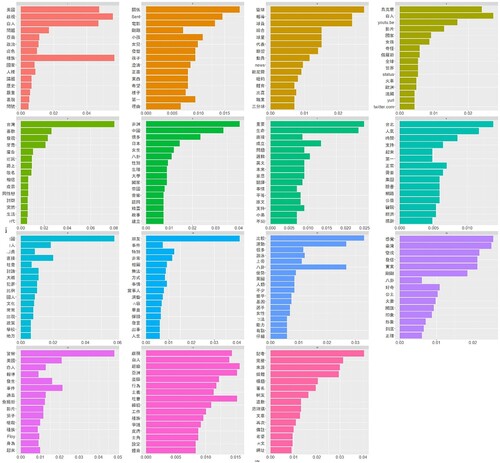

The results of the 10-topic and 15-topic models are presented below (see and ). These topics can be categorized into several themes, including ‘perceptions of racial discrimination against Black people,’ ‘perceptions of police and BLM,’ ‘perceptions of Black culture,’ ‘perceptions of Black people’s biological traits,’ ‘meanings of Black self-serve,’ ‘perceived racial hierarchy,’ and ‘Taiwanese netizens’ own cultural reflections.’ The first four themes resonate with racist discourse about Black people found on social media sites in the US (Cisneros & Nakayama, Citation2015; Nishi et al., Citation2015), which also suggests that Taiwanese netizens’ discussion topics are somewhat influenced by the media portrayals of Blacks in the US (e.g., on protesters/police violence). The fifth theme, however, presents a cultural analysis of how and why the discourse in Taiwan perseveres and resonates with the ‘old racism’ in other contexts.

Theme 1: beware of political correctness: black people are over-sensitive

Post Title: [News] The Louisiana Supreme Court suspends Judge Michelle Odinet after a video surfaced of her for using n-word

Content: Lafayette City Court Judge Michelle Odinet watched security footage of what appears to be a failed burglary at her home. In the video she was caught saying the term ‘nigger’ multiple times and calling an alleged Black burglar a ‘roach.’ The video went viral and yielded a lot of criticisms. She resigned after weeks of public scrutiny.

Theme 2: culturalization of biological differencePost Title: [Inquiry] What caused the high crime rates among Black communities?Content: We all know that there are high crime rates among Black communities. In some instances, they even use BLM as an excuse to rob and vandalize properties, and the government cannot do anything about them. Why are there high crime rates among Black-dominant neighborhoods, is it because the government ignores them?

Theme 3: from culture to gene: biological racismPost Title: [Inquiry] Are American Black people always having trouble and fighting the police every day?Content: There are a lot of YouTube channels nowadays about American Black people fighting the armed policemen with knives and sticks. Is it real? Are Black people crazy?

Theme 4: the meaning of self-serve: double standards and a ‘convenient’ claim

The above three themes constitute the basis of ‘Black self-serve’ – the belief that race (or racial injustice) can be strategically deployed by Black people to demand rights and entitlements, and to justify Black people’s behavior on any occasion. This term has negative associations for these Taiwanese netizens. It is associated with accusations that race (or racism) becomes a ‘convenient’ excuse for Black people’s bad behavior – with political correctness, anything that disregards Black people’s interests would be seen as racism. A good example can be substantiated from the misunderstanding of the slogan: ‘All Lives Can’t Matter Until Black Lives Matter’ in a discussion thread on NBA board.

Post Title: [Information] Kawhi Leonard wears an ‘All lives can’t matter until Black lives matter’ shirt in Clippers’ practice

Content: The incident of Jacob Blake has triggered more follow-up responses, Kawhi’s standpoint also incurred different interpretations. How do you guys see this?

Theme 5: perceived racial hierarchy and Taiwanese’ own cultural reflection

When commenting on BLM or Black people’s demands for racial justice, Taiwanese netizens’ discourse revealed a perceived racial hierarchy in different domains. Such a perceived hierarchy relates to cultural processes including colonization experiences, internal colonial logic, and sense of inferiority. For example, in terms of social economic status, the hierarchy often starts with White people at the top, followed by Asians or Latinos, and Black people on the bottom. In other contexts, like sports or physical attraction, White and Black people are seen as superior to Latinos and Asians. Group differences and conflicts are intensified when Black people is framed as a potential physical threat due to the prevailing stereotypes of cultural and biological racism, and as a potential aggressor of anti-Asian racism, particularly during COVID-19 (Ho, Citation2021; Wang & Santos, Citation2022).

Post Title: [Inquiry] Can we stop showing sympathy with Black people when seeing them being mistreated in the future?

Content: I saw the news saying a female Taiwanese student was hit by a Black only because she wore a mask. This really pissed me off! Seems American Black people are really problematic, why do we need to show sympathy with them?

These comments present how Taiwanese netizens are influenced by Western dominant racialized beliefs through media portrayals and see their positions within the racial hierarchy in different domains. Connecting to the previous four themes, Taiwanese netizens attempted to avoid the ‘courtesy stigma’ (Goffman, Citation1963) by distancing themselves from ‘self-serve’ Black people in the US and arguing that they (and Asians) are the ‘real’ disadvantaged group. This claim often aligns with the model minority stereotype and sees Asian people’s working ethics as superior to Black people’s cultural characteristics (e.g., laziness). At the same time, however, they attribute the fact of ‘Asians are below Black people’ to their own stereotypical cultural characteristics, particularly that of being obedient and therefore ‘deserve’ to live at the bottom of the hierarchy. On PTT, some posts manifested this sense of self-depreciation: ‘Black people would fight for their rights while Asians normally tolerate injustices happened to them so they deserve to be on the bottom.’

Another reply attributes Taiwanese’ obedience to the cultural and historical colonization experience. The author of the reply wrote:

We have been brainwashed by Western culture and values, so we think White people look prettier than Black people and Asians. And Taiwan used to be a colony of other countries like Japan, so we are obedient and have a sense of inferiority compared to other people. You can see that Asians work the hardest, taking jobs that other people don’t want to do, but on their inner side they still feel inferior to others.

Sentiment analysis

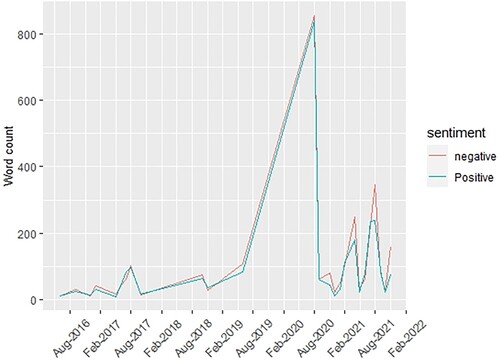

To understand the sentiments associated with posting/replying/commenting on matters related to ‘Black self-serve’ or ‘BLM,’ this study conducted a further sentiment analysis. The word level sentiment (see below) shows that positive and negative sentiments appear in a consistent trend over time, except there is a small shift in sentiment which happened around February of 2021. The amounts of sentiments also align with major movement events such as BLM in 2019 and anti-Asian hate crimes in the United States during the pandemic (Gover et al., Citation2020; Ho, Citation2021), which can be seen from an increase of negative sentiments in the early half of 2021. The presence of ‘positive’ sentiments here could mean that some Taiwanese netizens are supportive of BLM or global racial solidarity, even though such sentiments often involve the resonance of Asian people’s experience, such as ‘standing together against white supremacy.’ Yet, one thing that needs to be noted is that people may also use sarcastic language (such as ‘how great/convenient the self-serve is!’ ‘Righteous Black people are fighting for human rights!’ ‘Support BLM, so I am not a racist!’) to mock Black people’s fight for racial justice. Such mockery discourses reflect how the racialized beliefs of blackness are entrenched among Taiwanese netizens and reinforce the adherence to the racialization processes.

Discussion and conclusion

The symbiosis of self-perception and anti-blackness

Drawing on the major themes from posts, responses, comments, and sentiments containing the term ‘Black self-serve’ on the Taiwanese largest bulletin board system, this article examines how Taiwanese netizens perceived blackness in the absence of direct intergroup tensions or everyday encounters. The results suggest that racist and stereotypical comments are prevalent which reflect both self-perception in the global racial hierarchy and vision of blackness. Consistent with the racist rhetoric about blackness in the US, Taiwanese netizens associate Black people’s stereotypical cultural traits with biological ones (e.g., the tendency to engage in criminal activities, hedonism, etc.) and assign these traits in different domains of the social hierarchy. Although there are some replies and comments supporting BLM and against the racial injustices that Black people face (e.g., criticizing racist comments), they are the minority voices and are often seen as ‘awakened’ (or ‘woke’) youth, which is associated with negative meanings (i.e., too idealistic, supporting all kinds of social issues including feminism, ending the death penalty, legalizing marijuana, supporting abortion rights, etc.).

‘Black self-serve’ echoes Bonilla-Silva’s idea of the ‘biologization of culture’ (Citation2001, Citation2003a) – the conflation of biological and socio-cultural meanings of race. It also expresses Taiwanese people’s depreciation of Black people’s double standards, justifies Black people’s mistreatment and lower status in the racial hierarchy, and accuses Black people of conveniently using ‘race’ to fight for rights to which they are not entitled. However, Taiwanese netizens’ remarks do not simply reflect their stereotype of the other racial group. From their remarks we can see that the depreciation of blackness is deeply connected to Taiwanese historical experience of being colonized and their own self-perceptions (e.g., Confucius culture and being obedient), which led to two seemingly contradictory claims. On one hand, Taiwanese people compared their obedience to the Black revolt and detached themselves from ‘self-serve’ Black people. They internalize and reproduce the model minority myth which refers to having a hard-working ethic and high levels of socio-economic status achievement. On the other hand, obedience is one of the justifications they developed to navigate their sense of inferiority (e.g., inferiority to White people in the socio-economic sense, and the perception of their being worse than Black people in terms of sports, physical attractiveness, and the willingness to fight for rights).

How does anti-blackness shape the racial hierarchy within Taiwanese society? Through social media discussion and the echo chamber effects in the affective online communities such as PTT, the impact of white supremacy and global racial hierarchy is reinforced in the local context, which can be seen in Taiwanese preference for whiteness and prejudice against Black people, immigrants of color, and indigenous people in everyday life (Huang & Liu, Citation2016; Lan, Citation2011; Tierney, Citation2011).

Mediating conflicting visions and divisions: the potential for establishing the relatedness of Black people’s experiences

The data presented above show that due to historical and cultural legacy, Taiwanese netizens highlighted the negative traits of Black people – a mixture of cultural or biological – and reinforced their racialized visions and divisions. The racist comments may not be unique in Taiwan. Taiwanese netizens’ comments, however, reveal how people perceive the other racial group in the other side of the world, even without having direct encounters and interaction experiences. The vision, or image, of the other group also shows how people reflect upon their racial status in the racial hierarchy and attach specific racialized meanings in accordance with the dominant hierarchy. The meaning-making process of Taiwanese netizens’ discourse presents race as simultaneously a source of vision (conceptions about another race and racial difference between ‘us’ and ‘them’) and division (in terms of group differentiation and accepted conceptions, such as racial hierarchy) (Bourdieu, Citation1990; Gilroy, Citation2004).

Understanding the racialized vision of Taiwanese netizens contributes to the field of information and communication because it helps better evaluate how social media discussion reflects and reinforces the challenges to global racial solidarity, in addition to institutional constraints. The findings highlight that the legacy of racialized ideology, culture, and colonialism entrenched the racialized vision and division and offset common solidarity narratives for anti-Asian racism and BLM/anti-Black racism. The internalization of an existing racial hierarchy through own cultural self-reflection and the process of navigating one’s sense of inferiority, together decreases the potential for challenging the dominant racialized discourses and established racial hierarchy.

Scholars have drawn our attention to the racialization processes which lead to differentials in power and opportunity among minority groups (Shah, Citation2008; Lin, Citation2020). To deal with racial antagonism or to dissolve competing racial visions, I argue that there is a need to systematically examine the cultural formation and historical root pertaining to social media discussion on race and racism. The first step is not to debate whose lives matter over others, but rather it is to establish the relatedness of Black people’s experiences to the understanding of systemic racism and white supremacy. Only by realizing own sense of ascribed inferiority, cultural alienation from Black people, the colonization experience which led to the internalization of the dominant racial rhetoric, and the portrayal of Black people as accomplices to anti-Asian racism – all of which are deeply embedded within systemic racism – that Taiwanese people will be more likely to relate to other people’s demands and actions, such as in the case of BLM. At the policy level, activists and organizations can brainstorm initiatives to facilitate dialogue through social media and increase understanding about of Black peoples’ participation in protest movements in the context of their history/experience. The initiatives should also provide opportunities for people to critically reflect on their own position in society.

There remain some limitations in this article. First, it is invalid to claim that the findings are generalizable to all Taiwanese citizens. As mentioned, social media is a unique space where people may leave quick and ‘irresponsible’ remarks due to anonymity. The posts and comments may not represent one’s real opinions (Viviani & Pasi, Citation2017). Yet, this does not mean we should dismiss social media as an important channel of understanding one’s thoughts on race. Through exploring the meanings of ‘Black self-serve’ and Taiwanese netizens opinions of BLM, we can nevertheless understand the idea of why blackness is depreciated by and among another races. Second, social media and online discussion platforms often generate quick and short responses. Future scholars can conduct interviews, which provide a more substantial understanding of the contexts and experiences one has in relation to his/her perception of another group. Finally, discussions of cross-racial solidarity need not be limited to that of Asians-Black people; anti-Latino racism is another important issue (Gómez, Citation2020). Further research should explore the dynamics of the multiple intersections between, for example, Asian-Latino, Latino-Black, and Black-Asian-Latino groups.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Mei Ling (Jay) Chan and Adrian Lui for scraping and analyzing data, as well as generating figures. The earlier draft was presented at the Global Black Lives Matter Conference. I appreciate the valuable feedback from the organizers and the participants, especially Bin Xu, Karida Brown, and Jean Beaman. Some parts of the findings were translated into Chinese and posted on an academic blog: Streetcorner Sociology, the first website initiated by a group of scholars to promote accessibility of sociological knowledge. I extend thanks to two anonymous reviewers and the editor for their constructive comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yao-Tai Li

Yao-Tai Li is a Senior Lecturer of Sociology and Social Policy in the School of Social Sciences at University of New South Wales, Australia. He holds a Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of California, San Diego. His research interests include race and ethnicity, identity politics, discourse analysis, and social media. His work has been published in several scholarly journals including British Journal of Sociology, International Affairs, World Development, Urban Studies, New Media and Society, Big Data & Society, The Sociological Review, Current Sociology, Ethnic and Racial Studies, Discourse & Society, Identities, Social Movement Studies, Social Science Computer Review, among others. [email: [email protected]]

Notes

2 Note that Taiwanese people do not necessarily see themselves as ‘one race,’ the self-identification is quite diverse and may include Asians, Han people, Taiwanese Americans, and (indigenous) Taiwanese. What this article tries to present, is their perceived difference from Black people, and how netizens highlight the difference through online narratives.

References

- Ahn, J.-H. (2019). Anti-Korean sentiment and online affective community in Taiwan. Asian Journal of Communication, 29(6), 445–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2019.1679853

- Beaman, J. (2021). Towards a Reading of Black Lives Matter in Europe. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 59(S1), 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13275

- Berry, J. A., Cepuran, C., & Garcia-Rios, S. (2022). Relative group discrimination and vote choice among Blacks, Latinos, Asians, and Whites. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 10(3), 410–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2020.1842770

- Blaut, J. M. (1992). The theory of cultural racism. Antipode, 24(4), 289–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.1992.tb00448.x

- Blei, D. M., Ng, A. Y., & Jordan, M. I. (2003). Latent dirichlet allocation. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 3, 993–1022. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555944919.944937.

- Bonilla, T., & Tillery, A. (2020). Which identity frames boost support for and mobilization in the #BlackLivesMatter movement? An experimental test. American Political Science Review, 114(4), 947–962. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000544

- Bonilla-Silva, E. (2001). White supremacy and racism in the post–civil rights era. Lynne Rienner.

- Bonilla-Silva, E. (2002). The linguistics of color blind racism: How to talk nasty about Blacks without sounding “racist”. Critical Sociology, 28(1-2), 41–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/08969205020280010501

- Bonilla-Silva, E. (2003a). Racial attitudes or racial ideology? An alternative paradigm for examining actors’ racial views. Journal of Political Ideologies, 8(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569310306082

- Bonilla-Silva, E. (2003b). Racism without racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in the United States. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Bourdieu, P. (1990). Social space and symbolic power. In P. Bourdieu (Ed.), In other words: Towards a reflexive sociology (pp. 123–139). Stanford University Press.

- Bratt, C. (2022). Is it racism? The belief in cultural superiority across Europe. European Societies, 24(2), 207–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2022.2059098

- Brubaker, R. (2006). Ethnicity without groups. Harvard University Press.

- Carney, N. (2016). All lives matter, but so does race: Black Lives Matter and the evolving role of social media. Humanity & Society, 40(2), 180–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160597616643868

- Chaudhry, I., & Gruzd, A. (2019). Expressing and challenging racist discourse on Facebook: How social media weaken the “spiral of silence” theory. Policy & Internet, 12(1), 88–108. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.197

- Chou, C.-C. (2008). Critique on the notion of model minority: An alternative racism to Asian American? Asian Ethnicity, 9(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631360802349239

- Cisneros, J. D., & Nakayama, T. K. (2015). New media, old racisms: Twitter, Miss America, and cultural logics of race. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 8(2), 108–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/17513057.2015.1025328

- Corral, ÁJ. (2020). Allies, antagonists, or ambivalent? Exploring Latino attitudes about the Black Lives Matter movement. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 42(4), 431–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986320949540

- Craig, M. A., & Lee, M. M. (2022). Status-based coalitions: Hispanic growth affects Whites’ perceptions of political support from Asian Americans. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 25(3), 661–681. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684302211032286

- Della Porta, D., Lavizzari, A., & Reiter, H. (2022). The spreading of the Black Lives Matter movement campaign: The Italian case in cross-national perspective. Sociological Forum, 37(3), 700–721. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12818

- Edgar, A. N., & Johnson, A. E. (2018). The struggle over Black Lives Matter and All Lives Matter. Books.

- Espiritu, Y. L. (2016). Race and U.S. panethnic formation. In R. H. Bayor (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of American immigration and ethnicity (pp. 213–228). Oxford University Press.

- Feagin, J., & Elias, S. (2013). Rethinking racial formation theory: A systemic racism critique. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 36(6), 931–960. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2012.669839

- Fraga, L. R., & Perez, N. (2020). Latinos in the American racial hierarchy: The complexities of identity and group formation. In R. T. Teranishi, B. M. D. Nguyen, C. M. Alcantar, & E. R. Curammeng (Eds.), Measuring race: Why disaggregating data matters for addressing educational inequality (pp. 29–45). Teachers College Press.

- Gaines, K. (2022). Global Black Lives Matter. American Quarterly, 74(3), 626–634. https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2022.0042

- Garza, A. (2020). The purpose of power: How we come together when we fall apart. One World.

- Gavrielides, T. (2014). Bringing race relations into the restorative justice debate: An alternative and personalized vision of “the other”. Journal of Black Studies, 45(3), 216–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934714526042

- Gilroy, P. (2004). Between camps: Nations, cultures and the allure of race. Routledge.

- Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Prentice-Hall.

- Gómez, L. E. (2020). Inventing Latinos: A new story of American racism. The New Press.

- Gonzalez, A. (2022). Creating coalitions: Culture centers, anti-Asian violence, and Black Lives Matter. Journal of College and Character, 23(2), 180–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/2194587X.2022.2053294

- Gover, A. R., Harper, S. B., & Langton, L. (2020). Anti-Asian hate crime during the COVID-19 pandemic: Exploring the reproduction of inequality. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 647–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09545-1

- Grün, B., & Hornik, K. (2011). Topicmodels: An R package for fitting topic models. Journal of Statistical Software, 40(13), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v040.i13

- Hardeniya, T., & Borikar, D. A. (2016). Dictionary based approach to sentiment analysis—A review. International Journal of Advanced Engineering, Management and Science, 2(5), 317–322. https://www.neliti.com/publications/239438/dictionary-based-approach-to-sentiment-analysis-a-review.

- Ho, H.-Y., Chen, Y.-L., & Yen, C.-F. (2020). Different impacts of COVID-19-related information sources on public worry: An online survey through social media. Internet Interventions, 22, 100350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2020.100350

- Ho, J. (2021). Anti-Asian racism, Black Lives Matter, and COVID-19. Japan Forum, 33(1), 148–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/09555803.2020.1821749

- Hoffman, L., Granger, N., Vallejos, L., & Moats, M. (2016). An existential–humanistic perspective on Black Lives Matter and contemporary protest movements. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 56(6), 595–611. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167816652273

- Huang, S.-M., & Liu, S.-H. (2016). Discrimination and incorporation of Taiwanese indigenous Austronesian peoples. Asian Ethnicity, 17(2), 294–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631369.2015.1112726

- Ince, J., Rojas, F., & Davis, C. (2017). The social media response to Black Lives Matter: How Twitter users interact with Black Lives Matter through hashtag use. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40(11), 1814–1830. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1334931

- Jackson, S. (2016). (Re)imagining intersectional democracy from Black feminism to hashtag activism. Women's Studies in Communication, 39(4), 375–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/07491409.2016.1226654

- Keum, B. T. H., Nguyen, M. M. G., Ahn, L. H. R., Wong , M. J., Wong, L. J., Miller, M. J (2024). Fostering Asian American emerging adults’ advocacy against anti-Black racism through digital storytelling. The Counseling Psychologist, 52(4), 581–613. https://doi.org/10.1177/00110000241227994

- Kim, C. J. (1999). The racial triangulation of Asian Americans. Politics & Society, 27(1), 105–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329299027001005

- Kim, C. J. (2003). Bitter fruit: The politics of Black-Korean conflict in New York City. Yale University Press.

- Kumah-Abiwu, F. (2020). Media gatekeeping and portrayal of Black men in America. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 28(1), 64–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1060826519846429

- Lan, P.-C. (2011). White privileges, linguistic capital, and cultural ghettoization: Western skilled migrants in Taiwan. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 37(10), 1669–1693. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2011.613337

- Lee, S. J., Xiong, C. P., Pheng, L. M., & Vang, M. N. (2020). “Asians for Black lives, not Asians for Asians”: Building Southeast Asian American and Black solidarity. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 51(4), 405–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/aeq.12354

- Li, J. (2019). tmcn: A text mining toolkit for Chinese. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tmcn.

- Li, Y.-T., & Song, Y. (2020). Taiwan as ghost island? Ambivalent articulation of marginalized identities in computer-mediated discourses. Discourse & Society, 31(3), 285–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926519889124

- Liao, Y. (2022). pttR: Retrieve and process textual data from PTT. https://yongfu.name/pttR/.

- Lin, K.-Y., & Lu, H.-P. (2011). Why people use social networking sites: An empirical study integrating network externalities and motivation theory. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(3), 1152–1161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.12.009

- Lin, M. (2020). From alienated to activists: Expressions and formation of group consciousness among Asian American young adults. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(7), 1405–1424. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1495067

- Liu, B. (2020). Sentiment analysis: Mining opinions, sentiments, and emotions. Cambridge University Press.

- Liu, W. (2018). Complicity and resistance: Asian American body politics in Black Lives Matter. Journal of Asian American Studies, 21(3), 421–451. https://doi.org/10.1353/jaas.2018.0026

- Merseth, J. L. (2018). Race-ing solidarity: Asian Americans and support for Black Lives Matter. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 6(3), 337–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2018.1494015

- Nielsen, A. L., Bonn, S., & Wilson, G. (2010). Racial prejudice and spending on drug rehabilitation: The role of attitudes toward Blacks and Latinos. Race and Social Problems, 2(3-4), 149–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-010-9035-x

- Nishi, N. W., Matias, C. E., & Montoya, R. (2015). Exposing the White avatar: Projections, justifications, and the ever-evolving American racism. Social Identities, 21(5), 459–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630.2015.1093470

- Qin, W., & Wu, Y. (2019). jiebaR: Chinese text segmentation. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=jiebaR.

- Ray, R., Brown, M., & Laybourn, W. (2017). The evolution of# BlackLivesMatter on Twitter: Social movements, big data, and race. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40(11), 1795–1796. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1335423

- Shah, B. (2008). ‘Is Yellow Black or White?’: Inter-minority relations and the prospects for cross-racial coalitions between Laotians and African Americans in the San Francisco Bay Area. Ethnicities, 8(4), 463–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796808097074

- Shah, N. (2019). “Asians are good at math” is not a compliment: Stem success as a threat to personhood. Harvard Educational Review, 89(4), 661–686. https://doi.org/10.17763/1943-5045-89.4.661

- Shahin, S., Nakahara, J., & Sánchez, M. (2024). Black Lives Matter goes global: Connective action meets cultural hybridity in Brazil, India, and Japan. New Media & Society, 26(1), 216–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211057106

- Solomon, T. (2023). Up in the air: Ritualized atmospheres and the global Black Lives Matter movement. European Journal of International Relations, 29(3), 576–601. https://doi.org/10.1177/13540661231181989

- Taylor, E., Guy-Walls, P., Wilkerson, P., & Addae, R. (2019). The historical perspectives of stereotypes on African-American males. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work, 4(3), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-019-00096-y

- Tierney, R. (2011). The class context of temporary immigration, racism and civic nationalism in Taiwan. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 41(2), 289–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2011.553047

- Tillery, A. (2019). What kind of movement is Black Lives Matter? The view from Twitter. The Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics, 4(2), 297–323. https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2019.17

- Tseng, S.-F., Chen, W.-C., & Chi, C.-L. (2011). Online social media in a disaster event: Network and public participation. In H. Cherifi, J. M. Zain, & E. El-Qawasmeh (Eds.), Digital information and communication technology and its applications (pp. 256–264). Springer.

- Tsunokai, G. T., McGrath, A. R., & Kavanagh, J. K. (2014). Online dating preferences of Asian Americans. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 31(6), 796–814. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407513505925

- Vani, P., Alzahawi, S., Dannals, J. E., & Halevy, N. (2023). Strategic mindsets and support for social change: Impact mindset explains support for Black Lives Matter across racial groups. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 49(8), 1295–1312. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672221099710

- Viviani, M., & Pasi, G. (2017). Credibility in social media: Opinions, news, and health information—A survey. WIRES Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 7(5), e1209. https://doi.org/10.1002/widm.1209

- Wang, S. C., & Santos, B. M. C. (2022). Go back to China with your (expletive) virus: A revelatory case study of anti-Asian racism During COVID-19. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 13(3), 220–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/aap0000287

- Waters, M. C., & Jiménez, T. R. (2005). Assessing immigrant assimilation: New empirical and theoretical challenges. Annual Review of Sociology, 31(1), 105–125. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100026

- West, K., Greenland, K., & van Laar, C. (2021). Implicit racism, colour blindness, and narrow definitions of discrimination: Why some White people prefer ‘All Lives Matter’ to ‘Black Lives Matter’. British Journal of Social Psychology, 60(4), 1136–1153. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12458

- White, K., Stuart, F., & Morrissey, S. L. (2021). Whose lives matter? Race, space, and the devaluation of homicide victims in minority communities. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 7(3), 333–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649220948184

- Wickham, H. (2021). rvest: Easily harvest (scrape) web pages. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rvest.

- Xu, J., & Lee, J. C. (2013). The marginalized “model” minority: An empirical examination of the racial triangulation of Asian Americans. Social Forces, 91(4), 1363–1397. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sot049

- Yellow Horse, A. J., Kuo, K., Seaton, E. K., & Vargas, E. D. (2021). Asian Americans’ indifference to Black Lives Matter: The role of nativity, belonging and acknowledgment of anti-Black racism. Social Sciences, 10(5), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10050168

- Yu, T. (2006). Challenging the politics of the “model minority” stereotype: A case for educational equality. Equity & Excellence in Education, 39(4), 325–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665680600932333

- Zvornicanin, E. (2022). Topic modeling and Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA). DataScience+. https://datascienceplus.com/topic-modeling-and-latent-dirichlet-allocation-lda.