Abstract

Objective: Patients with chronic schizophrenia suffer a huge burden, as do their families/caregivers. Treating schizophrenia is costly for health systems. The European Medicines Agency has approved paliperidone palmitate (PP-LAI; Xeplion), an atypical antipsychotic depot; however, its pharmacoeconomic profile in Portugal is unknown. A cost-effectiveness analysis was conducted from the viewpoint of the Portuguese National Health Service.

Methods: PP-LAI was compared with long acting injectables risperidone (RIS-LAI) and haloperidol (HAL-LAI) and oral drugs (olanzapine; oral-OLZ) adapting a 1-year decision tree to Portugal, guided by local experts. Clinical information and costs were obtained from literature sources and published lists. Outcomes included relapses (both requiring and not requiring hospitalization) and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). Costs were expressed in 2014 euros. Economic outcomes were incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs); including cost-utility (outcome = QALYs) and cost-effectiveness analyses (outcomes = relapse/hospitalization/emergency room (ER) visit avoided).

Results: The base-case cost of oral-OLZ was 4447€ (20% drugs/20% medical/60% hospital); HAL-LAI cost 4474€ (13% drugs/13% medical/74% hospital); PP-LAI cost 5326€ (49% drugs/12% medical/39% hospital); RIS-LAI cost 6223€ (44% drugs/12% medical/44% hospital). Respective QALYs/hospitalizations/ER visits were oral-OLZ: 0.761/0.615/0.242; HAL-LAI: 0.758/0.623/0.250; PP-LAI: 0.823/0.288/0.122; RIS-LAI: 0.799/0.394/0.168. HAL-LAI was dominated by oral-OLZ and RIS-LAI by PP-LAI for all outcomes. The ICER of PP-LAI over oral-OLZ was 14,247€/QALY, well below NICE/Portuguese thresholds (≈24,800€/30,000€/QALY). ICERs were 1973€/relapse avoided and 2697€/hospitalization avoided. Analyses were robust against most variations in input values, as PP-LAI was cost-effective over oral-OLZ in >99% of 10,000 simulations.

Conclusion: In Portugal, PP-LAI dominated HAL-LAI and RIS-LAI and was cost-effective over oral-OLZ with respect to QALYs gained, relapses avoided, and hospitalizations avoided.

Introduction

The World Health Organization has listed schizophrenia among the top 10 causes of disability in the world and it is well known that health and social problems are worse in countries with lower GDP, such as PortugalCitation1,Citation2. It exerts a tremendous negative impact on healthcare in terms of cost, service provision, and support systemsCitation3,Citation4. As well, the quality-of-life is substantially lower in patients with schizophrenia than in those without, and is highly correlated with psychopathologyCitation5,Citation6.

This disease has no known cure; many patients endure a chronic and erratic clinical path that often involves numerous psychotic relapses which can frequently result in hospital admission or incarcerationCitation7. Patients suffering from this form of schizophrenia have been referred to as “revolving door” patients due to their frequent hospitalizationsCitation8. Investigations have identified non-adherence to medication and lack of response to medication as the most common causes for this phenomenonCitation9,Citation10. As a result, efforts have been made to find approaches to improve both adherence and response rates.

Two such innovations have been depot injections, also known as long-acting injectables (LAIs), and the development of atypical anti-psychotics. Depot forms help to decrease both intentional and unintentional non-adherenceCitation11. Drugs of this type have been available for decades; however, until this century, only the “typical” anti-psychotics such as haloperidol (HAL-LAI) were available. The first atypical LAI was risperidone (RIS-LAI; Risperdal Consta)Citation12,Citation13. The European Medicines Agency has also approved paliperidone palmitate (PP-LAI; Xeplion)Citation14,Citation15 which has also been approved for reimbursement in Portugal.

RIS-LAI is administered every 2 weeksCitation13, while PP-LAI may be injected monthlyCitation15. This difference may have implications for the cost of patient management, since administration interval may affect adherence. Currently, it is not known whether clinical differences reflect economic differences in actual practice. Thus, the pharmacoeconomics of these drugs for treating “revolving door” patients have not been established in Portugal. Therefore, we undertook the present investigation.

The primary goal of this research was to determine the cost-effectiveness of PP-LAI as compared with other commonly used treatments for such patients, including RIS-LAI, HAL-LAI and oral anti-psychotics. Secondary goals were to determine the cost-effectiveness of these dug in preventing relapses of the symptoms of schizophrenia.

Methods

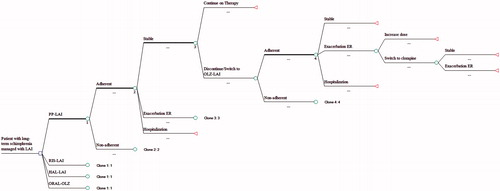

This pharmacoeconomic analysis was conducted according to the Portuguese Medicines Agency guidelines for economic drug evaluation studiesCitation16. We adapted a decision tree that had been previously validated and used in another European countryCitation17 for use in the Portuguese National Health Service (PNHS). The population of interest was the group of “revolving door” patients with schizophrenia. The term “revolving door” refers to patients who had longstanding disease with multiple recurrences of psychoses and hospitalizationsCitation8. A more recent paper defines them as “frequently admitted patients undergoing one or more admissions per year on average”Citation18. Because these patients adhere poorly to both appointments and medication regimens, they are frequently prescribed LAIs. The atypical drugs compared in this analysis were RIS-LAI and PP-LAI. We used haloperidol decanoate (HAL-LAI) to represent the traditional depots, as it is the most widely used traditional LAI in Portugal and systematic reviews have found little clinical difference among the available traditional depotsCitation19. Also, we included one oral drug to represent all orals, olanzapine (oral-OLZ), as it is commonly used. provides a summary of the doses used and sources for that informationCitation12,Citation13,Citation15,Citation19–38.

Table 1. Doses used to treat patients and data sources.

depicts the model used to analyze the data. Patients began with one of the LAIs or oral-OLZ, then followed clinical paths as determined by literature-based probabilities. Adherence to medication was first considered in the model and rates were adjusted accordingly using data from Weiden et al.Citation39. Patients could remain stable or could incur a relapse; some would be treated through the emergency room (i.e. the milder cases), while others would require hospitalization to stabilize their condition (i.e. the more severe cases). Those not successfully treated at the initial dose were titrated to its maximum dose. Patients receiving PP-LAI, RIS-LAI, or oral-OLZ who failed to respond to the maximum dose or who were unable to tolerate the drug were switched to a traditional depot anti-psychotic (i.e. HAL-LAI). After a subsequent failure or intolerance to HAL-LAI, they were given clozapine, as per the NICE guidelinesCitation39. Patients initiating with HAL-LAI and failing to achieve resolution of symptoms or who were intolerant to the drug were switched to oral-OLZ. provides a summary of the rates used as clinical inputs into the modelCitation29,Citation37,Citation40–57.

Table 2. Clinical input rates, utility scores, and their sources.

This model examined all direct costs of care that would be accrued by the PNHS in treating patients over a 1-year period of time. This time horizon precluded the need for discounting. Manufacturers’ price lists were used to determine drug costs; other costs were identified from the literature and expressed in 2014 euros, using the Consumer Price Index for Portugal as an inflatorCitation58. Clinical rates were also obtained from literature sources. lists the cost inputsCitation59.

Table 3. Resources consumed and their costs.Table Footnote*

The decision tree generated a set of clinical and economic outcomes for the average patient treated using standard approaches. The first outcome was the average (expected) cost per patient treated. Clinical events measured were relapses (including both those requiring hospitalization and those treated in the emergency room as out-patients), numbers of days in remission and relapse, and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) associated with each LAI. QALYs were determined using utilities derived from the literature, as presented in Citation50–54.

We conducted two types of analyses, including cost-utility and cost-effectiveness. As recommended by the CHEERS StatementCitation60, the economic outcome for these analyses was the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), which is the amount needed to pay to produce one unit of outcome. In accordance with the Portuguese guidelines for pharmacoeconomic studies, the primary economic outcome (ICER) was expressed in terms of the incremental cost per QALY gainedCitation16. NICE has established a threshold for cost-effectiveness of £20,000/QALYCitation61, which would be ∼24,800€/QALY at the average exchange rate for 2014 (£1 = 1.240 17€)Citation62. Also, Yazdanpanah et al.Citation63 have suggested that the Portuguese National Authority of Medicines (INFARMED) customarily adopts an informal threshold of 30,000€/QALY to indicate cost-effectiveness. These values were considered when assessing cost-effectiveness results.

In the secondary cost-effectiveness analyses, we determined the incremental cost per relapse, hospitalization, and emergency room (ER) visit avoided. Results were tested for sensitivity using 1-way analyses on all major inputs. Also, probabilistic analyses with 10,000 pairwise replications between LAIs was performed involving all inputs varied across plausible ranges using standard distributions such as gamma for costs and beta for rates.

Results

Overall results of the cost-utility analysis for the base case are presented in . Oral-OLZ had the lowest expect cost per patient treated. PP-LAI had the most QALYs, followed by RIS-LAI, then oral-OLZ, with HAL-LAI having the least. HAL-LAI was dominated by oral-OLZ since it had a higher cost and generated fewer QALYs. Similarly, RIS-LAI was dominated by PP-LAI. Thus, those two options were eliminated from consideration and the final two choices were compared (). The ICER for PP-LAI over oral-OLZ was 14,247€, which falls well below the usually accepted Portuguese threshold of 30,000€/QALY and the NICE threshold for cost-effectiveness of £20,000 (24,800€)/QALY.

Table 4. Results of the overall cost-utility analysis.

Table 5. Results of the final incremental analysis of PP-LAI over oral-OLZ.

Table 6. Clinical outcomes.

In the cost-effectiveness analyses, similar results were obtained. PP-LAI had the lowest rates of hospitalization, ER visits, and days in relapse (). As with QALYs, RIS-LAI was second lowest, oral-OLZ third lowest, and HAL-LAI had the highest rates for those outcomes. Both HAL-LAI and RIS-LAI were dominated, leaving oral-OLZ and PP-LAI for analysis. The ICER for PP-LAI over oral-OLZ was 1973€/relapse avoided and 2697€/hospitalization avoided.

One-way sensitivity analyses were robust for all parameters (see the Appendix for break-even values). PP-LAI would always cost the most, but would remain cost-effective over a very wide range of assumptions. When all inputs were varied across plausible ranges of values, PP-LAI was cost-effective over oral-OLZ in >99% of the 10 000 simulations. Overall, oral-OLZ cost significantly less (p = 0.006), as PP-LAI was less costly in only 12 simulations. On the other hand, PP-LAI generated more QALYs more than 99.8% of the time (p < 0.001).

Discussion

This analysis has demonstrated that PP-LAI is a cost-effective alternative for chronic schizophrenia in Portugal. According to these results, only oral drugs and PP-LAI should be considered as alternatives. Results were similar for both the cost-utility analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis which used relapses as its primary outcomes. The other choices considered (RIS-LAI and oral-OLZ) were found not to be cost-effective and, therefore, should not be considered further.

Results were robust, as demonstrated by the many sensitivity analyses performed. Although PP-LAI had a higher cost, it was cost-effective when judged by the prevailing standards. The cost-effectiveness was largely due to PP-LAI having a greater number of QALYs, which was statistically significant (p < 0.001).

An important factor in this model was adherence. The rates of adherence that were input into the model were 82.3% for RIS-LAI and 87.2% for PP-LAI. These rates are very close to the self-reported adherence rate of 89% in a study in which 125 Portuguese patients with schizophrenia were interviewedCitation64. Similarly, Lambert et al.Citation65 reported that the remission rate in patients who started in remission on conversion to RIS-LAI was 85% after 1 year of treatment. In our analysis, patients receiving RIS-LAI were in remission for 313.1 days or 85.8% of the time. Finally, the QALYs experienced by patients (i.e. 0.823 for PP-LAI and 0.799 for RIS-LAI) were comparable to what was reported by Lambert et al.Citation65, who stated that quality-of-life was rated adequate in 81.5% of 526 patients. These similarities provide a measure of external validation of the model.

As well, our estimated costs are remarkably lower than those previously found in European countries with stronger economiesCitation66,Citation67. However, they were quite similar to the costs estimated for other European countries having similar economic situationsCitation68,Citation69.

A search of both Medline and Embase located only two studies of the cost of anti-psychotics in PortugalCitation70–72. The abstract by Garrido et al.Citation70 indicated that they compared first and second generation drugs, but they did not present any actual results. The other study appeared both as an abstractCitation71 and a full text articleCitation72. Heeg et al.Citation72 reported that RIS-LAI dominated HAL-LAI and also oral drugs when used with this type of patient. Over a 5-year time horizon, RIS-LAI saved 3603€ and avoided 0.44 relapses compared with HAL-LAI. With respect to oral risperidone, RIS-LAI saved 4682€ and avoided 0.59 relapses.

The results from that study are similar to those from the present analysis in that the newer LAIs were cost-effective when compared with traditional LAIs or oral atypical anti-psychotics. However, there were a number of differences between these analyses. Different oral drugs were used by Heeg et al.Citation72 for both second and third line. Since that time, NICE has recommended that clozapine be used as third line in all casesCitation73. Heeg et al.Citation72 did not calculate QALYs; however, they did determine the number of outpatient days. Their calculations were very close to those in our model, which differed by 3.6% for RIS-LAI and 11% for HAL-LAI. The greatest difference was in the cost outcomes. The largest cost centers were drugs and hospitalization. In the analysis by Heeg et al., the price of RIS-LAI was 67% higher than the current price and HAL-LAI was 38% higher. Also, there has been a change in the method of reimbursement for acute care in the hospital in Portugal. They now have a fixed payment for hospital stays ranging from 5–89 days, much like a Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) payment as done in the USCitation74 and other countriesCitation75. Decreases in overall costs have similarly been observed after the introduction of DRGs in the USCitation76. To our knowledge, no other study has addressed the issue of the economics of anti-psychotics in Portugal.

The results found in this analysis parallel those we recently obtained in a similar analysis in Finland in that PP1M was the cost-effective choice over the same time frameCitation77. However, there were many differences in that study with respect to outcomes. For example, the costs were dramatically higher in Finland and the QALYs were much lower. Costs were higher for several reasons. First, all patients entered the model in acute relapse and were hospitalized, which also accounts for lower QALYs. Therefore, all patients incurred at least one hospitalization, which is quite costly, whereas most patients in Portugal remained stable as outpatients. Second, the costs of healthcare are much higher in Finland than in Portugal. Third, patients remain in hospital longer in Finland. Finally, as already mentioned, Portugal has implemented a DRG system to limit hospital costs. Another differences is that only LAIs were studies in Finland. In another economic analysis from France, Druais et al.Citation78 used a 5-year Markov model comparing six anti-psychotics. They also found oral-OLZ to have the lowest cost, with three of the comparison drugs being dominated. In their final analysis, only three drugs were considered. PP-LAI was cost-effective compared with oral-OLZ and RIS-LAI had an ICER per QALY (>4 million euros) that was far beyond the accepted threshold for cost-effectiveness. With respect to relapses, PP-LAI had an ICER of 1782€per relapse avoided, which approximates our ICER of 1973€.

Recently, there have been several clinical trials comparing PP-LAI to other atypical anti-psychotics, which adds clinical support to our findings. In the PROSIPAL Study, Schreiner et al.Citation79 found a 44% reduction in relapses between PP-LAI and oral drugs over a 2-year period. Similarly, Alphs et al.Citation80,Citation81 reported a 26% reduction over 15 months in the PRIDE Study. In our model, relapses were 48% lower with PP-LAI. In another study by Schreiner et al.’sCitation82 group, patients who did not respond to other depot anti-psychotics were switched to PP-LAI. Among those switched from RIS-LAI, 61.1% incurred a reduction in PANSS total score ≥20% within 6 months and 31.5% experienced a reduction ≥50%. That group reported similar results in patients unsuccessfully treated with oral drugs who were switched to PP-LAI, with ≥64% showing 20% improvement in PANSS total scoreCitation83. Finally, in a head-to-head comparison between PP1M (n = 381) and risperidone LAI (n = 366), efficacy results were similar, but slightly favored PP1MCitation84. Responder rates (i.e. ≥30% improvement in PANSS total score) were numerically higher with PP1M (56.7%) than for risperidone LAI (52.2%). These findings are similar to those in the present study.

Limitations

One limitation to this analysis is that the model had a 1-year analytic time horizon, whereas schizophrenia is a chronic, incurable disease with an erratic path over time. An analysis over the expected lifetime may provide further insights into long-term outcomes. To do so would require longitudinal data which are not often available.

Also, results are limited to the specific patients under study, who had chronic relapsing schizophrenia and required depot medications. They may not apply to persons with less severe symptoms who constitute the majority of those with the disease.

Furthermore, we are limited by the fact that the data were derived from RCTs conducted with highly selected patients under closely monitored conditions. Also, trials are often of limited duration (e.g. we used mostly trials with a 1-year duration). They may not entirely reflect what happens in real life. We did try to address this issue to some degree by incorporating such factors as patient adherence to treatment regimens. In addition, there is inherent uncertainty in modeling; hence, the application of numerous sensitivity analyses. Thus, these limitations should be kept in mind when interpreting these results or applying them to clinical practice. A need exists for real world data observed over time in these patients.

Finally, we did not conduct a budget impact analysis. Since the acquisition cost of PP1M is higher than that of oral drugs, its adoption would likely increase the drug budget. On the other hand, some of that increase would be offset by reduced hospitalizations and emergency room visits.

Conclusions

In this analysis, PP-LAI was cost-effective over oral-OLZ from the point of view of the PNHS; RIS-LAI and HAL-LAI were dominated. This and other factors, such as the impact on the drug budget (which would probably increase), should be considered when selecting drugs for patients with chronic relapsing schizophrenia.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This research was funded by Janssen A/S, Beerse, Belgium.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

TRE and BGB received funding from the sponsor for this research. SML, PG, and KvI are employees of Janssen. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Supported by Janssen Pharmaceutica NV, Beerse, Belgium.

References

- Mathers C, Boerma T, Ma Fat D. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2008

- Wilkinson R, Pickett K. The spirit level: why equality is better for everyone. London: The Equality Trust, 2009. http://www.equalitytrust.org.uk/. Accessed July 7, 2015

- Knapp M, Mangalore R, Simon J. The global costs of schizophrenia. Schiz Bull 2004;30:279-93

- Karagianis J, Novick D, Pecanek J, et al. Worldwide-Schizophrenia Outpatient Health Outcomes (W-SOHO): baseline characteristics of pan-regional observational data from more than 17,000 patients. Int J Clin Pract 2009;63:1578-88

- Brissos S, Dias VV, Carita AI, et al. Quality of life in bipolar type I disorder and schizophrenia in remission: clinical and neurocognitive correlates. Psychiatry Res 2008;160:55-62

- Brissos S, Dias VV, Balanzá-Martinez V, et al. Symptomatic remission in schizophrenia patients: relationship with social functioning, quality of life, and neurocognitive performance. Schizophr Res 2011;129:133-6

- Baillargeon J, Binswanger IA, Penn JV, et al. Psychiatric disorders and repeat incarcerations: the revolving prison door. Am J Psychiatry 2009;166:103-9

- Glazer W, Ereshefsky L. A pharmacoeconomic model of outpatient antipsychotic therapy in “revolving door” schizophrenic patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1996;57:337-45

- Weiden P, Glazer W. Assessment and treatment selection for “revolving door” inpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Q 1997;68:377-92

- Haywood TW, Kravitz HM, Grossman LS, et al. Predicting the “revolving door” phenomenon among patients with schizophrenic, schizoaffective, and affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:856-61

- Nasrallah H. The case for long-acting antipsychotic agents in the post-CATIE era. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2007;115:260-7

- Kane J, Eerdekens M, Lindenmayer J-P, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone: efficacy and safety of the first long-acting atypical antipsychotic. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:1125-32

- European Medicines Agency. Risperdal Consta® summary of product characteristics. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Referrals_document/Risperdal_Consta_30/WC500008170.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2015

- European Medicines Agency. Xeplion® opinion. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Summary_of_opinion_-_Initial_authorisation/human/002105/WC500099946.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2015

- European Medicines Agency. Xeplion® summary of product characteristics. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002105/WC500103317.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2015

- Alves da Silva E, Gouveia Pinto C, Sampaio C, et al. Guidelines for economic drug evaluation studies. Lisbon: INFARMED, 1998. http://www.ispor.org/PEguidelines/source/PE%20guidelines%20in%20English_Portugal.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2015

- Einarson TR, Vicente C, Zilbershtein R, et al. Pharmacoeconomics of depot antipsychotics for treating chronic schizophrenia in Sweden. Nord J Psychiatry 2014;68:416-27

- Martínez-Ortega JM, Gutiérrez-Rojas L, Jurado D, et al. Factors associated with frequent psychiatric admissions in a general hospital in Spain. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2012;58:532-5

- Adams CE, Fenton MP, Quraishi S, et al. Systematic meta-review of depot antipsychotic drugs for people with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 2001;179:290-9

- Gopal S, Hough D, Xu H, et al. Efficacy and safety of paliperidone palmitate in adult patients with acutely symptomatic schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2010;25:247-56

- Fleischhacker W, Gopal S, Lane R, et al. A randomized trial of paliperidone palmitate and risperidone long-acting injectable in schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2011;22:1-12

- Kissling W, Heres S, Lloyd K, et al. Direct transition to long-acting risperidone - analysis of long-term efficacy. J Psychopharmacol 2005;19:15-21

- Lee M, Ko Y, Lee S, et al. Long-term treatment with long-acting risperidone in Korean patients with schizophrenia. Hum Psychopharmacol 2006;21:399-407

- Olivares J, Rodrigues-Morales A, Diels J, et al. Long-term outcomes in patients with schizophrenia treated with risperidone long-acting injection or oral antipsychotics in Spain: Results from the electronic Schizophrenia Treatment Adherence Registry (e-STAR). Eur Psychiatry 2009;24:287-96

- Lindenmayer J-P, Khan A, Eerdekens M, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of long-acting injectable risperidone in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2007;17:138-44

- Quraishi SN, David A, Brasil MA, et al. Depot haloperidol decanoate for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1999;Issue 1:CD001361

- Komossa K, Rummel-Kluge C, Hunger H, et al. Olanzapine versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;Issue 3:CD006654

- Pandina G, Lane R, Gopal S. A double-blind study of paliperidone palmitate and risperidone long-acting injectable in adults with schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2011;35:218-26

- Hough D, Gopal S, Vijapurkar U. Paliperidone palmitate maintenance treatment in delaying the time-to-relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res 2010;116:107-17

- Nasrallah HA, Gopal S, Gassmann-Mayer C. A controlled, evidence-based trial of paliperidone palmitate, a long-acting injectable antipsychotic, in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010;35:2072-82

- Pandina GJ, Lindenmayer J-P, Lull JM. A randomized, placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy and safety of 3 doses of paliperidone palmitate in adults with acutely exacerbated schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2010;30:235-44

- Jayaram MB, Hosalli P, Stroup TS. Risperidone versus olanzapine for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;Issue 2:CD005237

- Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1209-23

- Meltzer HY, Lindenmayer JP, Kwentus J. A six month randomized controlled trial of long acting injectable risperidone 50 and 100mg in treatment resistant schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2014;154:14-22

- Chue P, Eerdekens M, Augustyns I, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of long-acting risperidone and risperidone oral tablets. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2005;15:111-17

- Eerdekens M, Van Hove I, Remmerie B, et al. Pharmacokinetics and tolerability of long-acting risperidone in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2004;70:91-100

- Gopal S, Vijapurkar U, Lim P, et al. A 52-week open-label study of the safety and tolerability of paliperidone palmitate in patients with schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol 2010;25:685-97

- Hough D, Lindenmayer J-P, Gopal S, et al. Safety and tolerability of deltoid and gluteal injections of paliperidone palmitate in schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2009;33:1022-31

- Weiden P, Kozma C, Grogg A, et al. Partial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 2004;55:886-91

- Olivares JM, Peuskens J, Pecenak J, et al. Clinical and resource-use outcomes of risperidone long-acting injection in recent and long-term diagnosed schizophrenia patients: results from a multinational electronic registry. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:2197-206

- Mehnert A, Diels J. Mehnert A, Diels J. Impact of administration interval on treatment retention with long-acting antipsychotics in schizophrenia. Presented at the Tenth Workshop on Costs and Assessment in Psychiatry -Mental Health Policy and Economics; 25-27 March 2011, Venice, Italy

- Bartkó G, Herceg I, Zador G. Clinical symptomatology and compliance in schizophrenia patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1988;77:74-6

- Heyscue BE, Levin GM, Merrick JP. Compliance with depot antipsychotic medication by patients attending outpatient clinics. Psychiatr Serv 1998;49:1232-4

- Guo X, Fang M, Zhai J, et al. Effectiveness of maintenance treatments with atypical and typical antipsychotics in stable schizophrenia with early stage: 1-year naturalistic study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;216:475-84

- Hamilton SH, Revicki DA, Edgell RT, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of olanzapine compared with haloperidol for schizophrenia: results from a randomised clinical trial. Pharmacoeconomics 1999;15:469-80

- Yu AP, Ben-Hamadi R, Birnbaum HG, et al. Comparing the treatment patterns of patients with schizophrenia treated with olanzapine and quetiapine in the Pennsylvania Medicaid population. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:755-64

- Ascher-Svanum H, Faries D, Zhu B. Medication adherence and long-term functional outcomes in the treatment of schizophrenia in usual care. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;2006:453-60

- Csernansky JG, Mahmoud R, Brenner R, et al. A comparison of risperidone and haloperidol for the prevention of relapse in patients with schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2002;346:16-22

- Rabinowitz J, Lichtenberg P, Kaplan Z, et al. Rehospitalization rates of chronically ill schizophrenic patients discharged on a regimen of risperidone, olanzapine, or conventional antipsychotics. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:266-9

- Briggs A, Wild D, Lees M. Impact of schizothrenia and schijophrenia treatmeft-related adverse events on qua,ity of mife: direct utimitx elicitation. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:105

- Cummins C, Stevens A, Kisely S. The use of olanzapine as a first and second choice treatment in schizophrenia. A West Midlands Development and Evaluation Committee Report. Birmingham, UK: Department of Public Health & Epidemiology, University of Birmingham; 1998

- Lenert LA, Sturley AP, Rapaport MH, et al. Public preferences for health states with schizophrenia and a mapping function to estimate utilities from positive and negative symptom scale scores. Schiz Res 2004;71:155-75

- Oh PI, Lanctôt KL, Mittmann N, et al. Cost-utility of risperidone compared with standard conventional antipsychotics in chronic schizophrenia. J Med Econ 2001;4:137-56

- Revicki DA, Shakespeare A, Kind P. Preferences for schizophrenia-related health states: a comparison of patients, caregivers and psychiatrists. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1996;11:101-8

- Rittmannsberger H, Pachinger T, Keppelmuller P, et al. Medication adherence among psychotic patients before admission to inpatient treatment. Psychiatr Serv 2004;55:174-9

- Valenstein M, Copeland LA, Owen R, et al. Adherence assessments and the use of depot antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62:545-51

- Ascher-Svanum H, Zhu B, Faries DE, et al. Adherence and persistence to typical and atypical antipsychotics in the naturalistic treatment of patients with schizophrenia Patient Prefer Adherence 2008;2:67-77

- Portugal inflation rate (consumer prices). http://www.indexmundi.com/portugal/inflation_rate_(consumer_prices).html. Accessed April 17, 2015

- Ministério da Saúde. Portaria n.° 20/2014, de 29 de Janeiro. Diário da República, 1.a série — N.° 20. http://www.acss.min-saude.pt/Portals/0/DownloadsPublicacoes/Tabelas_Impressos/Portaria%20132_2014.pdf. Accessed June 15, 2015

- Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. Pharmacoeconomics 2013;31:361-7

- McCabe C, Claxton K, Culyer AJ. The NICE cost-effectiveness threshold: what it is and what that means. Pharmacoeconomics 2008;26:733-44

- European Central Bank. Exchange rates pound. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/exchange/eurofxref/html/eurofxref-graph-gbp.en.html. Accessed June 15, 2015

- Yazdanpanah Y, Perelman J, DiLorenzo MA, et al. Routine HIV screening in Portugal: clinical impact and cost-effectiveness. PLoS One 2013;8:e84173

- Ferreira L, Belo A, Cassiano Abreu-Lima C. A case-control study of cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular risk among patients with schizophrenia in a country in the low cardiovascular risk region of Europe. Rev Port Cardiol 2010;29:1481-93

- Lambert M, De Marinis T, Pfeil J, et al. Establishing remission and good clinical functioning in schizophrenia: predictors of best outcome with long-term risperidone long-acting injectable treatment. Eur Psychiatry 2010;25:220-9

- Einarson TR, Vicente C, Zilbershtein R, et al. Pharmacoeconomics of depot antipsychotics for treating chronic schizophrenia in Sweden. Nord J Psychiatry 2014;68:416-27

- Einarson TR, Pudas H, Zilbershtein R, et al. Pharmacoeconomic analysis of atypical antipsychotic depots for chronic schizophrenia in Finland J Med Econ 2013;16:1096-105

- Jukic V, Jakovljevic M, Filipcic I, et al. Cost-utility analysis of depot antipsychotics for chronic schizophrenia in Croatia. Value Health Reg J Central East Europe 2013:181-8

- Einarson TR, Zilbershtein R, Skoupá J, et al. Economic and clinical comparison of atypical depot antipsychotic drugs for treatment of chronic schizophrenia in the Czech Republic. J Med Econ 2013;16:1089-95

- Garrido P, Pereira C, Craveiro A. Atypical antipsychotics versus first generation antipsychotics: comparison of overall efficacy and costs in a Portuguese sample. Abstract P.3.c.044. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2011;21(3 Suppl):S493-S4

- Heeg BM, Buskens E, Vaz Serra A, et al. Costs and effects of Risperdal Consta in comparison to conventional depot and short-acting atypical formulations in Portugal. Value Health 2004;7:778

- Heeg BM, Antunes J, Figueira ML, et al. Cost-effectiveness and budget impact of long-acting risperidone in Portugal: a modeling exercise Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:349-58

- Schizophrenia. The NICE guidelines on core interventions in the treatment and management of schizophrenia in adults in primary and secondary care. Updated edition. National Clinical Guideline Number 82. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2010

- Rosenheck R, Massari L, Astrachan BM. The impact of DRG-based budgeting on inpatient psychiatric care in Veterans Administration medical centers. Med Care 1990;28:12-34

- Frick U, Barta W, Binder H. [Hospital financing in in-patient psychiatry via DRG-based prospective payment–The Salzburg experience]. Psychiatr Prax 2001;28(1 Suppl):S55-62

- Rosenheck R, Massari L. Psychiatric inpatient care in the VA: before, during, and after DRG-based budgeting. Am J Psychiatry 1991;148:888-91

- Einarson TR, Pudas H, Goswami P, et al. Pharmacoeconomics of long-acting atypical antipsychotics for acutely relapsed chronic schizophrenia in Finland. J Med Econ 2016;19:111-20

- Druais S, Doutriaux A, Cognet M, et al. Cost effectiveness of paliperidone long-acting injectable versus other antipsychotics for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia in France. Pharmacoeconomics 2016;34:363-91

- Schreiner A, Aadamsoo K, Altamura AC, et al. Paliperidone palmitate versus oral antipsychotics in recently diagnosed schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2015;169:393-9

- Alphs L, Mao L, Lynn Starr H, et al. A pragmatic analysis comparing once-monthly paliperidone palmitate versus daily oral antipsychotic treatment in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2016;170:259-64

- Alphs L, Benson C, Cheshire-Kinney K, et al. Real-World outcomes of paliperidone palmitate compared to daily oral antipsychotic therapy in schizophrenia: a randomized, open-label, review board-blinded 15-month study. J Clin Psychiatry 2015;76:554-61

- Schreiner A, Bergmans P, Cherubin P, et al. Paliperidone palmitate in non-acute patients with schizophrenia previously unsuccessfully treated with risperidone long-acting therapy or frequently used conventional depot antipsychotics. J Psychopharmacol 2015;29:910-22

- Schreiner A, Bergmans P, Cherubin P, et al. A prospective flexible-dose study of paliperidone palmitate in nonacute but symptomatic patients with schizophrenia previously unsuccessfully treated with oral antipsychotic agents. Clin Ther 2014;36:1372-88.e1

- Alphs L, Bossie CA, Sliwa JK, et al. Paliperidone palmitate and risperidone long-acting injectable in subjects with schizophrenia recently treated with oral risperidone or other oral antipsychotics. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2013;9:341-50