ABSTRACT

How does government ideology, measured by the ideology of the chief executive and the ideology of the largest government party, influence the implementation of civil war peace agreements? In this study, I address this research question by analysing the Peace Accords Matrix (PAM) dataset that covers 34 comprehensive peace agreements of 31 countries from 1989 to 2015. The results of feasible generalised least squares (FGLS) regressions demonstrate that the likelihood of implementing peace agreements increases when chief executives and the largest government parties of the left-wing are in office. In contrast, the likelihood of implementing peace agreements decreases when chief executives and the largest government parties of the right-wing stay in power. Consistent with the party-policy literature and the hawkish-dovish assumptions, I find that left-wing governments positively impact the implementation of peace agreements more than right-wing governments, indicating the statistically significant relationship between the government ideology and the implementation of peace agreements.

Introduction

Civil war peace agreements have increased dramatically worldwide in the post-Cold War period.Footnote1 It has been observed that 83 per cent of all peace agreements signed between 1990 and 2019 were related to intrastate conflicts.Footnote2 The conflicting parties sign peace agreements to reduce their distrust, address their incompatibilities, rebuild their war-torn relationship, and promote reconciliation to build a shared peaceful future.Footnote3 Surprisingly, on average, peace agreements survive three and a half years before the conflicts resume.Footnote4 The Conflict Recurrence Database of Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), developed mainly existing data on organised violence by the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), claims that about half of all conflict episodes between 1989 and 2018 recurred, with 20 per cent having recurred three or more times over the same issues (64 per cent), overlapping issues or grievances (27 per cent), new incompatibility (3 per cent) and unrelated issues to the previous episode (less than 1 per cent).Footnote5 Collier and SambanisFootnote6 have described the failure of peace agreements and the recurrence of the conflicts as a ‘conflict trap’ that presents a puzzle – why peace agreements fail in some countries but not in others.

Research to date has developed several theoretical perspectives to address this puzzle. For example, Stedman and RothchildFootnote7 argue that civil war spoilers can undermine the implementation of peace agreements using violence. To make the implementation of peace agreements more effective, Joshi, Lee, and Mac GintyFootnote8 have emphasised the three built-in safeguards: transitional power-sharing, dispute resolution, and verification mechanisms. Maekawa, Arı, and GizelisFootnote9 have underscored the intervention of the United Nations as the third party in implementing peace agreements.

However, the impacts of government ideology on the implementation of peace agreements have remained unexplored in the scholarship. Existing studiesFootnote10 claim that political leaders are responsive to their party since they need support from party members to stay in power. Due to leaders’ accountability to their parties, they pursue their policies in line with the preferences of their party members and supporters. Koch and CranmerFootnote11 argue that partisan supporters constrain leaders in policymaking by withdrawing their support to punish those leaders who fail to deliver on their promises.

Following the logic of the party-policy literature, I expect the influence of government ideology on the implementation of peace agreements since conservatives and liberals hold different worldviews about the legitimacy of the use of force. Ryckman and BraithwaiteFootnote12 argue that some leaders favour peace negotiation, while others prefer military victory. Palmer, London, and ReganFootnote13 have found the link between ideology and hawkish-dovish behaviour of the government parties. According to them, right-wing governments are more likely to be hawkish since they do not have a fear of electoral punishment for their hawkish policies. ClareFootnote14 and Bertoli, Dafoe, and TragerFootnote15 argue that the likelihood of conflict increases following the right-wing parties taking office, indicating the influence of ideology on state behaviour.Footnote16 While scholars of comparative politics have found the relationship between government decisions and positions of the government parties on the left-right spectrum,Footnote17 international relations literatureFootnote18 has recently confirmed the impacts of government ideology on international conflict and international agreements.

Despite a growing body of literature on the impacts of government ideology in comparative politics and international relations, peace research has still paid insufficient attention to government ideology. It is mainly limited to different ethnopolitical and religious ideologies of rebel groups by focusing on three main functions of ideology: ideology as a normative commitment of rebels, ideology as an instrument for political mobilisation, and ideology as a predominant determinant of rebel behaviour.Footnote19 This study has addressed this gap in the existing literature by examining the impacts of government ideology on the implementation of peace agreements. Consistent with the party-policy literature and hawkish-dovish assumptions, I find that the likelihood of implementing peace agreements increases when left-wing government parties are in power. In contrast, the likelihood of implementing peace agreements is lower when right-wing government parties stay in power following the signing of peace agreements.

The article proceeds as follows. In the first section, I have introduced the research puzzle of the study, which is vital to understand the success and failure of peace agreements. In the second section, I have illustrated the role of ideology from the civil war to the peace process. In the third section, I have developed the theoretical framework for this study and formulated a set of hypotheses to test my theoretical expectations. In the fourth section, I have discussed the research design, focusing on the operationalisation of variables. In the fifth section, I have provided an empirical analysis based on the statistical results of feasible generalised least squares (FGLS) regressions. The sixth section summarises the findings and highlights this study’s limitations.

The role of political ideology from civil war to peace process

The term ‘political ideology’ can be traced back to the political texts of the sixteenth century.Footnote20 Since then, scholars have defined political ideology in various ways. For instance, Ugarriza and CraigFootnote21 have defined ideology as a set of beliefs that promotes a thorough understanding of the world and shapes relations between the in-group and out-group members. According to Sanín and Wood,Footnote22 ideology is a set of ideas that identifies a referent group, enunciates the grievances that the group confronts, and prescribes a programme of action to defend the group’s interests. MaynardFootnote23 conceives ideology as the distinctive political worldviews of individuals, groups, and organisations.

Existing peace researchFootnote24 has used ideology to explain several dimensions of intrastate armed conflicts, such as the higher recruitment of female combatants in the Marxist and leftist insurgent groups and the lower prevalence of female fighters in the Islamist rebel groups. Besides, ideology influences the behaviour of rebel groups in using selective and indiscriminate violence, as observed in the practice of restraint in violence against civilians by the Marxist-Leninist groups, namely, the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and Mozambican Liberation Front (FRELIMO).Footnote25 Apart from this, insurgent groups’ ideology is decisive in improving women’s social and economic rights in the post-war context.Footnote26 This scholarly line of investigation concentrates only on insurgent groups’ ideology but has overlooked the role of government ideology in understanding civil war and the implementation of peace agreements.

Hence, this cross-national research has focused on government ideology, which influences government parties’ behaviour and policy position on the implementation of peace agreements in conflict-affected countries. Following Koch and Cranmer,Footnote27 I define government ideology as political orientations that revolve around policies, issues, and ideas necessary to the political parties. Why does government ideology matter? The idea is that incumbent leaders and government parties are held accountable for their policy performances.Footnote28 Greene and LichtFootnote29 find a link between party ideology and government policies. For instance, right-wing governments are generally pro-military and more concerned with self-defence, whereas left-wing governments are anti-military and believe in a more peaceful world.Footnote30 However, there are some exceptions, such as Germany’s right-wing party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), which opposed the military deployments in the Middle East.Footnote31

Similarly, a few exceptions exist in intrastate peace processes. For instance, conservative parties, such as both the centre-right Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) and Democratic Rally (DISY), which built their party images around ethnic or religious boundaries and enjoyed support from conservative constituencies, traditionally refused reconciliation or negotiation with the ’other’, Irish nationalists and Turkish Cypriots, respectively. They altered their party position to support peace agreements due to the impacts of their political learning through sustained interactions with external pro-peace allies. But, leftist parties, such as the Republican Turkish Party (CTP) in Turkey and the Socialist Party (PSOE) in post-Franco Spain, have mainly led the pro-peace campaigns across countries.Footnote32

Since both types of war differ, a question might also arise about integrating the hawkish-dovish literature of interstate conflict and agreements into the study on peace agreement implementation. Notably, a substantial amount of literatureFootnote33 argues that applying international relations theory has benefited the civil war research programme in developing theories of how civil wars end. ReganFootnote34 adds that foreign policymakers have devoted their energy to containing intrastate conflicts since the end of the Cold War. MasonFootnote35 also asserts that the boundary line between interstate and civil wars has become increasingly blurred in the post-Cold War period. In their study, Mattes and SavunFootnote36 applied the bargaining model of war to explain how to endure peace after the civil war. Drawing on this growing body of research, I develop the theoretical framework, combining the party-policy literature, the hawkish-dovish literature, and intrastate peace agreement literature that has focused on several case studies, such as Northern Ireland, Israel, and Colombia in the third section of the paper. More importantly, the role of government ideology in implementing peace agreements has remained unexplored in civil war research, which has compelled this study to borrow theories from comparative politics and international relations to explain why left parties facilitate the implementation of peace agreements more than the right-wing parties.

Left-right ideology and the implementation of peace agreements

Political parties are ideologically driven and want to maintain their party identity.Footnote37 They interpret the same political world from distinct perspectivesFootnote38 and adopt different policy positions on similar issues.Footnote39 Besides, the issue ownership theory argues that political parties and their candidates emphasise those issues on which they have ownership and comparative advantage during political campaigns.Footnote40 When they are in office, they enact policies that align with their partisans’ preferences and support bases. Otherwise, domestic and international support bases can withdraw support from incumbent parties that fail to deliver on their promises.Footnote41 Due to the fear of electoral punishment, the left-wing parties are more likely to favour social insurance than the right-wing parties.Footnote42 Left-wing government parties prioritise the benefits of the working class, while right-wing government parties focus on the interests of the capitalist class.Footnote43

A similar fundamental distinction between right-wing and left-wing parties exists on the issues of war and peace. In general, the right-wing government parties favour hawkish policies and state aggression, while others oppose using force.Footnote44 The reason is that right-wing governments believe in military solutions to problems, whereas left-wing governments hold the opposite perspective.Footnote45 The Comparative Manifesto Project (CMP) develops an international peace index based on those indicators that cover statements of political parties concerning their policy positions on the military and peaceful settlement of conflicts. It has been observed that the left ideology of government parties is positively associated with the international peace index.Footnote46

International relations literature suggests that government ideology determines the financial contribution of the member states of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Countries that have experienced a significant change in government ideology from right to left have halted their financial contribution to this military alliance.Footnote47 Palmer, London, and ReganFootnote48 demonstrate that the shift in power from the left-wing government to the right-wing government raises the initiation of armed conflict by double. Similarly, ClareFootnote49 observes that the likelihood of military conflict increases twofold when the right-wing parties come to power. Bertoli, Dafoe, and TragerFootnote50 also find that countries with the right governments are more likely to experience militarised conflicts than countries with left governments.

A group of scholars explains why ideology fundamentally determines government parties’ hawkish and dovish behaviour. Bertoli, Dafoe, and TragerFootnote51 argue that right-wing governments take hawkish policies since they have a low risk of losing power for their aggressive policy stances.Footnote52 Besides, the use of force is legitimised by their support base, which is more concerned with national security, military superiority, and the defence budget.Footnote53 In contrast, left governments are more likely to oppose using force since war can damage the reputation and credibility of dovish political parties since left voters are pacifists who oppose realpolitik and aggressive policy.Footnote54 For example, politicians and voters aligned with Labour and Democratic parties were more supportive of the Good Friday Agreement (1998) than those with the Conservative Party of the United Kingdom.Footnote55

Israel can also offer fresh insights into the relationship between government ideology and the implementation of a peace agreement. Left-wing Labour Party government signed the Oslo peace agreement (1993) with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), but the right-wing Likud Party government jeopardised this peace process initiated by the previous government.Footnote56 One of the key explanations is that the right-wing hawks and left-wing doves have different views of the Israel-Palestinian conflict. Doves believe in peace, while hawks refuse to negotiate with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). The dovish coalition under the left-wing Labour Party came to power in 1992 and signed the Oslo Accord with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) on 13 September 1993. In contrast, hawkish leader Benjamin Netanyahu and his right-wing party won the 1996 election and made no effort to implement the Oslo Accord. Instead, he gave priority to the national security of Israel.Footnote57 The case of Israel suggests that left-wing parties facilitate the peace agreement more than right-wing parties, which obstruct the implementation of the peace agreement as spoilers when they are in office.

In the same way, Colombia exhibits an ideological divide between left-wing and right-wing political parties over the 2016 peace agreement signed between the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). Political polarisation at the elite level shaped the public’s attitudes on the 2016 referendum to ratify this peace agreement with broader public support. Influenced by narratives and framing of political leaders, conservative voters who identified themselves with the Democratic Centre Party and viewed this peace agreement as a contrast to their religious and traditional values voted ‘no’ in the referendum to reject this agreement. Conversely, voters from left-dominated regional and conflict-affected areas voted ‘yes’ to support this peace deal.Footnote58 In brief, these three cases – Northern Ireland, Israel, and Colombia – demonstrate the influence of political ideology in the implementation of civil war peace agreements. Drawing on existing party-policy literature, hawkish-dovish literature, and these three cases, I develop the following hypotheses to test the effects of government ideology on the implementation of peace agreements.

Hypothesis 1:

Left-wing chief executives are more likely to implement peace agreements than chief executives of other ideological orientations.

Hypothesis 2:

Right-wing chief executives are less likely to implement peace agreements than chief executives of other ideological orientations.

Hypothesis 3:

Left-wing government parties are more likely to implement peace agreements than government parties of other ideological orientations.

Hypothesis 4:

Right-wing government parties are less likely to implement peace agreements than government parties of other ideological orientations.

Data and method

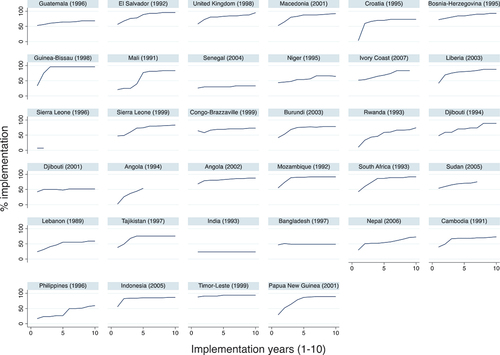

To test the impacts of government ideology on the implementation of peace agreements, I have used the Peace Accord Matrix (PAM) dataset,Footnote59 which covers 34 comprehensive peace agreements in 31 countries from 1989 to 2015 (see ), as a principal source of information for the dependent variable. I have used the Database of Political Institutions (DPI)Footnote60 for independent variables: chief executives’ ideology and government parties’ ideology. I have also collected information on control variables, such as the number of battle-related deaths, conflict duration, the level of democracy, and GDP per capita, from several existing datasets, such as the Polity dataset and World Development Indicators (WDIs).Footnote61 The unit of analysis of this study is agreement-year, whereas I have determined the temporal scope between 1989 and 2015 based on data availability. In the following sub-sections, I have explained the operationalisation of dependent, independent, and control variables for this study. presents the descriptive statistics of the variables of this study.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the variables of the study.

Dependent variable

There are two main approaches to measuring the implementation of peace agreements: one is the binary measure, and the other is the continuous scale. In their Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) Peace Agreements dataset, Pettersson, Högbladh, and ÖbergFootnote62 measure the implementation of peace agreements on a binary scale by coding 1 if a peace agreement fails and one or more warring parties that signed contest and officially withdraw from a peace agreement and 0 otherwise. However, the binary measure cannot capture the degree of implementation and those peace agreements that are neither ‘fully implemented’ nor ‘failed with the return to violence’. Consequently, a binary approach potentially leads to the estimation of inefficient parameters due to its limitation in explaining the variation of the implementation of peace agreements. In contrast, implementing peace agreements is an incremental outcome instead of a binary outcome: implemented or not implemented.Footnote63

Hence, Joshi, Quinn, and ReganFootnote64 have developed a 4–point ordinal scale (0=no implementation, 1=minimal implementation, 2=intermediate implementation, and 3=full implementation) to measure the implementation of every provision of the peace agreements. They have used the following formula to calculate the annual implementation rate: (actual implementation value/expected implementation value) x 100. It first sums up the actual implementation value of a peace agreement’s provisions. Then it divides the sum by the expected value of a peace agreement’s provisions. Finally, the outcome is multiplied by 100. They have standardised implementation scores to make them comparable given different lengths of peace agreements across countries by using this formula in their PAM dataset.

Notably, the implementation variable of peace agreements is additive and reflects the number of points achieved in previous accord years plus the current accord year.Footnote65 Besides, aggregate (rather than specific) implementation is vital for post-conflict outcomes since only an aggregate score captures progress relative to milestones.Footnote66 Besides, the length of peace agreements varies, with Sudan having the highest number of 43 provisions and Guinea-Bissau having the lowest number of 8 provisions. It can be challenging to conduct cross-national comparative research on provision-by-provision. Hence, previous studiesFootnote67 have used an aggregated implementation score as the outcome variable. Following earlier research, I have used this measure of aggregated implementation of peace agreements – IMPLEM – as the dependent variable of this study (N = 323, Mean = 65.95, and SD = 21.73). shows the implementation rate of peace agreements, with a comparatively higher implementation rate in El Salvador, the UK, Macedonia, and South Africa and a relatively lower implementation rate in the Philippines, Senegal, and India.

Independent variables

The impacts of government ideology on the implementation of peace agreements are the fundamental interest of this empirical research. Gul, Podder, and ShariarFootnote68 measure the government ideology with two variables: the political ideology of the chief executives and the political ideology of the largest government parties on the left-right spectrum. Following Gul, Podder, and Shariar,Footnote69 I have used these two variables to measure the government ideology for this study. The primary motivation for using this measure of government ideology for this cross-national research is data limitations which did not allow me to construct a government ideological turnover index and estimate its effects on the implementation. Apart from the lack of data on the political ideology of many developing countries, such as Djibouti and DR Congo, many regional political parties have come to power as junior coalition partners in several countries, for example, India, Indonesia, and Senegal. However, no secondary sources of information exist on the political ideologies of regional political parties, which work on ethno-religious lines. Also, locating them on the left-right spectrum based on their election platforms is methodologically challenging.

I have operationalised the ideology of the chief executive with two binary variables: LEFTEXEC and RIGHTEXEC. I have constructed the LEFTEXEC by coding 1 if a left-wing chief executive is in power and 0 otherwise following a peace agreement. In contrast, I have generated the RIGHTEXEC by coding 1 if a right-wing chief executive is in office and 0 otherwise following a peace agreement (see and for the descriptive statistics on chief executives’ ideologies in democratic and non-democratic countries of this study). To test the impacts of the ideology of the largest government parties, I have constructed the LPARTY by coding 1 if a left-wing largest government party is in power following a peace agreement and 0 otherwise. Similarly, I have generated the RPARTY by coding 1 if the right-wing party is in office and 0 otherwise following a peace agreement (see and for the descriptive statistics of ideologies of largest government parties of this research).

Table 2. Cross-tabulation of the chief executives’ ideology.

Table 3. Cross-tabulation of the largest government parties’ ideology.

However, a crucial question might arise whether all left-wing former rebel parties are comparable in their leftist ideology to the incumbent (non-rebel) left-wing parties. To reduce this ambiguity, I have operationalised the ideology of the chief executives and the largest government parties for this research following the DPI.Footnote70 For instance, rebel parties have come to power in several countries, such as the Communist Party of Nepal Maoist (CPN-M) in Nepal and the African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa. I have coded the ideologies of CPN-M in Nepal and ANC in South Africa as ‘left’ following the DPI coding procedure.

Control variables

I have included several control variables in my empirical analysis presented in to account for the rival explanations of the implementation of peace agreements. First, I have constructed a variable – YCOUNT – to control the temporal dependence of this study following Joshi, Lee, and Mac Ginty.Footnote71 Second, the higher causality rate of previous civil wars determines the level of recruitment of rebels for a new rebellion. Costly wars might be less vulnerable to another round of civil war due to the lack of resources, the reluctance of soldiers, and the absence of public support.Footnote72 To control the impacts of the cost of war, I have constructed a logged transformed continuous variable – BDEATH – that counts the total number of people killed in the civil war until a peace agreement is signed.

Table 4. Effects of the chief executives’ ideology on peace agreement implementation.

Table 5. Effects of the largest government parties’ ideology on peace agreement implementation.

Third, the world is populated with multiethnic states, with 82 per cent of all independent states comprising two or more ethnic groups, often involved in disputes with each other or the state itself. Previous studies argue that controlling territory is vital to ethnic groups and states because both believe their survival depends on it. For ethnic groups, territory is often a defining attribute of their identity, intimately connected to their past and continued existence as a distinct group. In contrast, territorial borders define states that tend to view challenges to those borders as threats to their very existence. In addition, states will regard territory as indivisible when they believe that allowing one group to gain territorial sovereignty will set a precedent that will encourage other ethnic groups to demand sovereignty. Consequently, conflicts over territory involving the demand for autonomy and secession are more likely to be challenging to resolve than governmental conflicts.Footnote73 Hence, I expect the implementation to be lower for territorial than governmental conflicts. Following previous studies,Footnote74 I have constructed a dichotomous variable – CONTYPE – by coding 1 for governmental conflicts and 0 for territorial conflicts to rule out the effects of the conflict type on the implementation.

Fourth, conflicting parties do not accept compromise and negotiation to settle the conflict peacefully when the conflict endures with increased costs of war.Footnote75 Consistent with earlier research, the longer the conflict lasts, the lower the implementation scores. To control the effects of conflict duration on the implementation, I have constructed – CONDUR – as a logged transformed continuous variable that counts the number of days a conflict endures until conflicting parties reach a peace agreement. Fifth, a militant group may hesitate to lay down its weapons as it would lose its principal leverage point without them.Footnote76 Rebels can also thwart the implementation of peace agreements when they lose their confidence and trust in the government’s ability and willingness to implement provisions related to the root causes of the conflict, such as autonomy provisions. Besides, rebel leaders might not cooperate with the government to implement a deal when they fear internal resistance.Footnote77 Thus, rebels might play the role of spoilers in implementing peace agreements. Hence, I have controlled the number of rebel groups – REBGRP – in the empirical analysis following the spoiler literature.Footnote78

Sixth, successful peace agreements contain a broad range of provisions that shape public support for the contents of peace agreements.Footnote79 Hence, I expect the more a peace agreement has provisions, the more its implementation will be. To rule out the design effect of the peace agreements, I have constructed a continuous variable – TOTPROV – that counts the number of provisions every deal contains. Seventh, the democratic civil peace literatureFootnote80 argues that democracy reduces the likelihood of conflict and violence by peacefully addressing dissidents’ grievances. Besides, ordinary citizens can constrain democratic leaders from initiating a war. In contrast, non-democratic leaders can start a war without public approval.Footnote81 Hence, I expect that democracy would improve the implementation of peace agreements. Following earlier research,Footnote82 I have used the 21–point scale of the Polity IV to define democracies (countries with scores between 6 and 10) and non-democracies (countries with scores between −6 and 5) and then conduct sub-sample analyses to explain whether the impacts of government ideology on the implementation of peace agreements varies across democratic and non-democratic countries. In contrast, I have included the V-Dem electoral democracy index – EDINDEX – and V-Dem liberal democracy index – LDINDEX – to control the effects of democracy in the empirical analysis on the entire PAM dataset.

Eighth, existing literatureFootnote83 has found that state capacity positively impacts the implementation and used GDP per capita as the proxy measure of state capacity. To rule out the positive effects of state capacity on the implementation of peace agreements, I have constructed a logged transformed continuous variable – GDPLOG – using data from World Development Indicators. Ninth, the United Nations’ intervention can make the implementation process effective,Footnote84 and hence I expect positive impacts of the United Nations’ intervention in implementing peace agreements. To account for the effects of United Nations intervention on the implementation, I have constructed a dichotomous variable – POLMIS – by coding 1 for the deployment of the political mission of the United Nations and 0 otherwise.

Results and discussion

The statistical results of cross-sectional dependence, group-wise heteroskedasticity, and serial correlation tests confirm that the PAM dataset has serial correlation, suggesting classical panel data models – pooled OLS, fixed effects model, random-effects model, and linear mixed-effects – will not be appropriate estimation techniques for this time-series dataset. Joshi, Lee, Mac GintyFootnote85 and ChakmaFootnote86 used feasible generalised least squares (FGLS) regressions with a first–order auto-regressive process or AR(1) to address serial correlation. Similarly, to deal with serial correlation, parameters are estimated in models 1–8 in using FGLS with AR(1), which have fixed effects and recognise the serial autocorrelation in the error structure. Besides, I have included the number of years that have passed in the implementation process to deal with the temporal dependence issue.

I have used three types of predictors in the empirical analysis: the government ideology variables (the main explanatory variables), potentially confounding political variables (such as the level of democracy and GDP per capita as a proxy measure of state capacity), and the United Nations’ intervention as the thrid party. Due to a higher correlation between LEFTEXEC and LPARTY, I have not included both explanatory variables in the same regression model. Similarly, I have run separate regressions for the RIGHTEXEC and RPARTY because of the higher correlation between these two variables.

Another main distinction in the FGLS models also lies in the sample size. Models 1–4 in are limited to the sub-samples of democratic and non-democratic countries, whereas models 5–8 in provide deeper insights into the impacts of government ideology on the implementation of peace agreements for the entire sample of this study. Besides, models 5–8 in have included – POLMIS – the deployment of the political mission of the United Nations, whereas models 1–4 in do not account for the impacts of third-party intervention in the implementation of peace agreements. Besides, I have also included V-Dem electoral democracy index and V-Dem liberal democracy index in models 5–8 in since many political scientistsFootnote87 are critical of the Polity IV due to its endogeneity problems with civil war.

My theoretical expectation was that government ideology, measured by the ideology of the chief executive and the ideology of the largest government party, would influence the implementation of comprehensive peace agreements. The results of the t-test in Appendix and FGLS regressions in models 1–2 and 5–6 in support my Hypothesis 1 that left chief executives are more likely to implement peace agreements than chief executives of other ideological orientations. The results are statistically significant at β = 8.07and p < 0.001 (model 1), β = 5.32and p < 0.001 (model 5), and β = 5.19and p < 0.01 (model 6). In contrast, the results of the t-test in Appendix and FGLS regressions in models 3–4 and 7–8 in support my Hypothesis 2 that the right-wing ideology of chief executives negatively influences the implementation of peace agreements. The results are statistically significant at β = −9.38 and p < 0.001 (model 3), β = −19.80 and p < 0.001 (model 4), β = −10.67 and p < 0.001 (model 7), and β = −11.16 and p < 0.001 (model 8). These statistical results demonstrate the impacts of chief executives’ ideology on implementing peace agreements.

As expected, the results of the t-test in Appendix suggest that the largest government parties of the left-wing are more likely to implement peace agreements than those of other ideological orientations. The results of FGLS regressions are also statistically significant at β = 8.07and p < 0.001 (model 1 in ), β = 4.28 and p < 0.01 (model 5 in ) and β = 4.14 and p < 0.05 (model 6 in ). These statistical results support my Hypothesis 3 that the largest government parties of the left-wing are more likely to implement peace agreements than the largest parties of other ideological orientations. On the contrary, the statistical results of the t-test in Appendix and FGLS regressions in models 3–4 and 7–8 in support my Hypothesis 4 that the right-wing parties are less likely to implement peace agreements than the largest parties of other ideological orientations. The results are statistically significant at β = −9.38 and p < 0.001 (model 3 in ), β = −4.47 and p < 0.05 (model 4 in ), β = −6.49 and p < 0.001 (model 7 in ), and β = −6.63 and p < 0.001 (model 8 in ). Based on these statistical results, I argue that peace agreement implementation depends on which party controls the government.

Overall, the results of this study are consistent with the party–policy literature of comparative politics and the hawkish-dovish literature of international relations, as discussed above, that left governments are more likely to adopt dovish policies, as opposed to hawkish right-wing governments. Several case studies could be used to triangulate the statistical results of this study. For example, the case of Israel explains the impacts of government ideology on the implementation of the Oslo Peace Accord (1993), although there might be several plausible explanations for the failure of this peace process. In the 1996 election, the right-wing voters, who did not believe in the Oslo Peace Accord, actively supported Netanyahu and his Likud Party. The principal reason for the popularity of the hawkish party was the vulnerable security environment.Footnote88 TorgovnikFootnote89 argues that personal security became a salient issue in the election due to the rise of terrorist attacks by Palestinian religious fanatics in major Israeli cities. Getmansky and ZeitzoffFootnote90 find that people who reside within the range of rocket fire are more likely to vote for the right-wing Likud Party. Berribi and KlorFootnote91 conclude that one suicide attack three months before an election increases vote shares of the right-wing party by 1.35 per cent. As expected, the Likud Party’s electoral victory under Netanyahu’s leadership hindered the Oslo peace process in several ways. For instance, Netanyahu refused to meet and discuss with Arafat as a partner for peace. In contrast, Arafat declined to meet and have a dialogue with Netanyahu after the attack on the archaeological tunnel of Jerusalem.Footnote92

The control variables of this study also provide insights into the implementation of peace agreements. The temporal dependence variable – YCOUNT – positively influences the implementation of peace agreements at p < 0.001 across all the models in . This result is consistent with Joshi, Lee, and Mac GintyFootnote93 that the implementation scores of the current year positively correlate with the implementation scores of the previous years. In line with Walter,Footnote94 I find that the implementation of peace agreements is higher for costly wars, indicating the lower likelihood of recurrence of civil conflicts. The results are statistically significant at p < 0.001 in models 5–8 in . Similar to Duffy Toft,Footnote95 I find that the implementation scores of peace agreements for territorial conflicts are lower than governmental conflicts in all the models in , except for model 2 and model 4 in and model 2 in . Models 1–8 in suggest that the duration of conflict decreases the likelihood of the implementation of peace agreements at p < 0.01, and the results are consistent with Maekawa, Arı and Gizelis.Footnote96

Similarly, the number of rebel groups decreases the implementation of peace agreements, and this result is in line with Maekawa, Arı, and Gizelis.Footnote97 The number of provisions also positively impacts the implementation of peace agreements, and the results are statistically significant p < 0.01 in model 2 and models 5–8 in and models 5–8 in . Both democracy variables – EDINDEX and LDINDEX – positively influence the implementation of peace agreements at p < 0.01 across all the models in except for model 6 in . The results are in line with the democratic peace thesis literature.Footnote98 Similar to Maekawa, Arı and Gizelis,Footnote99 I also find the positive influence of GDP and the intervention of the United Nations – POLMIS on the implementation - of peace agreements at p < 0.01 across models 1–8 in .

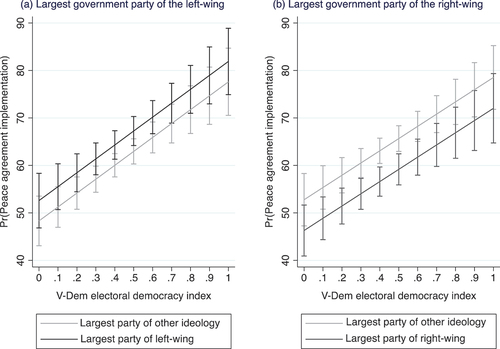

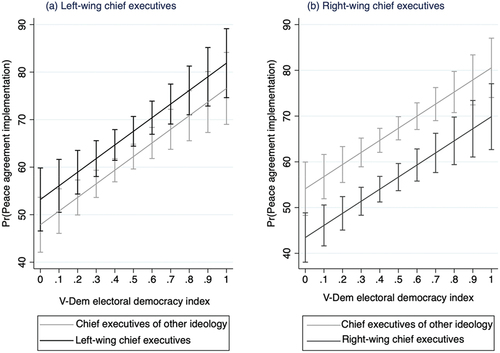

Based on the estimates of model 5 and model 7 in , I have produced , which shows the predicted marginal effects of chief executives’ ideology on implementing peace agreements. As shown in panel (a) in , the mean predicted level of implementing peace agreements is higher when left-wing chief executives remain in office. This result supports Hypothesis.1. In contrast, panel (b) in demonstrates that the mean predicted level of implementing peace agreements is lower when the right-wing chief executive is in office, which supports my Hypothesis 2.

Figure 3. Predicted marginal effects of the chief executives’ ideology on peace agreement implementation with 95 per cent CIs.

I have also generated to display the predicted marginal effects of the largest partiesy-’s ideology on the implementation of peace agreements based on the estimates of model 5 and model 7 in . As can be seen from panel (a) in , the mean predicted level of implementing peace agreements increases when the largest government party of the left-wing remain in office. This result supports Hypothesis 3. Contrastingly, panel (b) in reveals that the mean predicted level of implementing peace agreements decreases when the largest government party of the right-wing is in office, which supports my Hypothesis 4.

Conclusion

The findings of this study confirm the impacts of government ideology on the implementation of comprehensive civil war peace agreements. The left-wing chief executives and largest government parties positively impact the implementation more than the right-wing chief executives and largest government parties. The results of this cross-national research align with the party-policy literature in comparative politicsFootnote100 and the hawkish-dovish literature in international relationsFootnote101 that left-wing governments are more likely to be dovish than hawkish right-wing governments. Besides, the cases of Israel,Footnote102 Northern IrelandFootnote103 and ColombiaFootnote104 discussed above support the hypotheses of this study. Hence, this study contributes to understanding the role of government ideology in implementing peace agreements across countries.

Nevertheless, the scope of this study is limited to comprehensive peace agreements. Consequently, the effects of government ideology on peace process agreements and partial peace agreements have remained beyond the scope of this study. Besides, some provisions of peace agreements might be easier to implement than others. Mac GintyFootnote105 argues that parties will implement those provisions that suit them and ignore or delay the implementation of those that do not work for them. However, the question of what specific provisions is less or more likely to facilitate the implementation of peace agreements in the context of government ideological changes has yet to be explored since this study has focused on aggregate (rather than specific) implementation, which can only capture progress relative to milestones.Footnote106 Besides, conducting cross-national research on provision-by-provision is challenging because of the variation in the length of peace agreements.

In addition, this research has focused only on the ideology of the chief executives and the largest government parties because of data limitations. For instance, no database exists on the ideological orientations of regional political parties, which work as junior coalition partners with mainstream dominant parties in many countries such as Indonesia, India, and Senegal. Coding political ideologies of regional political parties on the left-right spectrum has remained another practical challenge since they emphasise a particular ethnic group or geographical region.

Despite its data limitations, this study might contribute to international peacebuilding missions led by several states, for instance, India in Nepal’s civil war and Japan’s Mindanao conflict.Footnote107 Moreover, several regional and international organisations, including the United Nations (UN), European Union (EU), and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), carry out three types of peace-brokering roles – mediation, economic sanctions, and peacekeeping – in settling civil conflicts.Footnote108 In particular, the end of the Cold War has brought a radical shift in the United Nations-led international peacebuilding missions both qualitatively and quantitatively to assist many conflict-affected countries such as El Salvador, Namibia, Cambodia, and Mozambique in implementing peace agreements.Footnote109

Because of the war-ravaged economy and dysfunctional state institutions in conflict-affected countries, international assistance is instrumental in the post-conflict reconstruction phase. However, international peacebuilding missions sometimes fail to produce the expected outcomes due to multiple factors that include but are not limited to insufficient international aid, state capacity, the emergence of spoilers, and the government’s willingness.Footnote110 Acknowledging the importance of these explanatory variables in implementing peace agreements, this study suggests that the success of international peacebuilding might also be influenced by government ideology – which party is in power following the signing of peace agreements. Hence, International peacebuilding policy research could explore how peace agreements can survive in the political transition when hawkish parties come to power following peace agreements.

Acknowledgement

This research article is partially connected to my doctoral project, overseen by the School of Politics and International Relations (SPIR) at the Australian National University (ANU). I sincerely appreciate Distinguished Professor of Political Science Ian McAllister, Professor Benjamin Goldsmith, and Dr Svitlana Chernykh for their invaluable guidance and unwavering support during my PhD program. Additionally, I would like to express gratitude to Dr Dylan Hendrickson and the two anonymous reviewers whose insightful feedback significantly enhanced the quality of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anurug Chakma

Dr Anurug Chakma is a Research Fellow within the Migration Hub at the School of Regulation and Global Governance (RegNet) at the Australian National University (ANU), Canberra, Australia. His diverse research portfolio spans from civil war, terrorism, and peacebuilding to indigenous rights, diaspora affairs, and the innovative application of text-as-data methods. For inquiries or further communication, Dr Chakma can be reached at [email protected].

Notes

1. Badran, ‘Intrastate Peace Agreements’; Joshi et al., ‘Built-in Safeguards’.

2. Bell and Wise, ‘Peace Processes’.

3. Joshi and Quinn, ‘Implementing the Peace’; Braniff, ‘After Agreement’.

4. Hartzell et al., ‘Stabilizing the Peace after Civil War’.

5. Jarland et al., ‘How Should We Understand Patterns of Recurring Conflict?’

6. Collier and Sambanis, ‘Understanding Civil War’.

7. Stedman and Rothchild, ‘Peace Operations’.

8. Joshi et al., ‘Built-in Safeguards’.

9. Maekawa et al., ‘UN Involvement’.

10. Imbeau et al., ‘Left-Right Party Ideology’.

11. Koch and Cranmer, ‘Testing the “Dick Cheney” Hypothesis’.

12. Ryckman and Braithwaite, ‘Changing Horses in Midstream’.

13. Palmer et al., ‘What’s Stopping You?’

14. Clare, ‘Ideological Fractionalization’.

15. Bertoli et al., ‘Is There a War Party?’

16. Ahmadov and Hughes, ‘Ideology and Civilian Victimization’.

17. For example, Beck et al., ‘New Tools in Comparative Political Economy’.

18. For instance, Bertoli et al., ‘Is There a War Party?’

19. Thaler, ‘Ideology and Violence in Civil Wars’; Sanín and Wood, ‘Ideology in Civil War’.

20. Maynard, ‘Ideology and Armed Conflict’.

21. Ugarriza and Craig, ‘The Relevance of Ideology’.

22. Sanín and Wood, ‘Ideology in Civil War’.

23. Maynard, ‘Ideology and Armed Conflict’.

24. For instance, Wood and Thomas, ‘Women on the Frontline’.

25. Thaler, ‘Ideology and Violence in Civil Wars’.

26. Gurses et al., ‘Women and War’.

27. Koch and Cranmer, ‘Testing the “Dick Cheney” Hypothesis’.

28. Bueno de Mesquita et al., The Logic of Political Survival.

29. Greene and Licht, ‘Domestic Politics’.

30. For example, Koch and Sullivan, ‘Should I Stay or Should I Go Now?’; Clare, ‘Ideological Fractionalization’.

31. Böller, ‘Fuelling Politicisation’.

32. Sandal and Loizides, ‘Center – Right Parties’.

33. For instance, Mason, ‘International Relations Theory’; Regan, ‘Conditions of Successful Third-Party Intervention’.

34. Regan, ‘Conditions of Successful Third-Party Intervention’.

35. Mason, ‘International Relations Theory’.

36. Mattes and Savun, ‘Fostering Peace after Civil War’.

37. Budge et al., ‘Ideology, Party Factionalism and Policy Change’; Stravers, ‘Pork, Parties, and Priorities’.

38. Graham et al., ‘Liberals and Conservatives’.

39. For instance, Imbeau et al., ‘Left-Right Party Ideology’; Tavits and Letki, ‘When Left is Right’; Blum and Potrafke, ‘Does a Change of Government Influence Compliance’; Mattes and Weeks, ‘Hawks, Doves, and Peace’.

40. Kim, ‘Issue Ownership’.

41. Koch and Cranmer, ‘Testing the “Dick Cheney” Hypothesis’; Grieco et al., ‘When Preferences and Commitments Collide’.

42. Donder and Hindriks, ‘Equilibrium Social Insurance’.

43. Potrafke, ‘The Growth of Public Health Expenditures in OECD Countries’; Brender, ‘Government Ideology and Arm Exports’.

44. Danzell, ‘Political Parties’; Whitten and Williams, ‘Buttery Guns and Welfare Hawks’; Koch and Cranmer, ‘Testing the “Dick Cheney” Hypothesis’; Stravers, ‘Pork, Parties and Priorities’.

45. Koch and Cranmer, ‘Testing the “Dick Cheney” Hypothesis’.

46. Brender, ‘Government Ideology and Arm Exports’.

47. Blum and Potrafke, ‘Does a Change of Government Influence Compliance with International Agreements?’

48. Palmer et al., ‘What’s Stopping You?’

49. Clare, ‘Ideological Fractionalization’.

50. Bertoli et al., ‘Is There a War Party?’

51. Ibid.

52. Arena and Palmer, ‘Politics or the Economy?’

53. Rathbun, ‘Partisan Interventions’.

54. Ibid.

55. Liendo and Braithwaite, ‘Determinants of Colombian Attitudes’.

56. Maoz, ‘Peace-building with the Hawks’.

57. Ibid.

58. Liendo and Braithwaite, ‘Determinants of Colombian Attitudes’.

59. Joshi et al., ‘Annualized Implementation Data’.

60. Beck et al., ‘New Tools in Comparative Political Economy’.

61. The World Bank, ‘World Development Indicators’.

62. Pettersson et al., ‘Organized Violence’.

63. Joshi et al., ‘Annualized Implementation Data’.

64. Ibid.

65. For instance, Hauenstein and Joshi, ‘Remaining Seized of the Matter’; Maekawa et al., ‘UN Involvement’.

66. Kerreth et al., ‘International Third Parties’; Hauenstein and Joshi, ‘Remaining Seized of the Matter’; Maekawa et al., ‘UN Involvement’.

67. Ibid.

68. Gul et al., ‘Performance of Microfinance Institutions’.

69. Ibid.

70. Beck et al., ‘New Tools in Comparative Political Economy’.

71. Joshi et al., ‘Built-in Safeguards’.

72. Walter, ‘Does Conflict Beget Conflict?’.

73. Duffy Toft, ‘Indivisible Territory’; Walter, ‘Bargaining Failures’; Joshi et al., ‘Built-in Safeguards’.

74. Mason and Grieg, ‘State Capacity’; Krause et al., ‘Women’s Participation’.

75. Badran, ‘Intrastate Peace Agreements’.

76. Mac Ginty, ‘Time, Sequencing and Peace Processes’.

77. Duursma and Fliervoet, ‘Fuelling Factionalism?’.

78. Maekawa et al., ‘UN Involvement’; Stedman and Rothchild, ‘Peace Operations’.

79. Joshi and Quinn, ‘Implementing the Peace’.

80. Bartusevičius and Skaaning, ‘Revisiting Democratic Civil Peace’; Francois et al., ‘Revolutionary Attitudes’.

81. Fjelde et al., ‘Which Institutions Matter?’.

82. For instance, Mattes et al., ‘Measuring Change in Source of Leader Support’.

83. Fearon and Laitin, ‘Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War’; DeRouen Jr et al., ‘Civil War Peace Agreement Implementation’.

84. Maekawa et al., ‘UN Involvement’.

85. Joshi et al., ‘Built-in Safeguards’.

86. Chakma, ‘Leadership Changes’.

87. For instance, Vreeland, ‘The Effects of Political Regime on Civil War’.

88. Sela, ‘Difficult Dialogue’.

89. Torgovnik, ‘Strategies under a New Electoral System’.

90. Getmansky and Zeitzoff, ‘Terrorism and Voting’.

91. Berribi and Klor, ‘Are Voters Sensitive to Terrorism?’

92. Sela, ‘Difficult Dialogue’.

93. Joshi et al., ‘Built-in Safeguards’.

94. Walter, ‘Does Conflict Beget Conflict?’

95. Duffy Toft, ‘Indivisible Territory’.

96. Maekawa et al., ‘UN Involvement’.

97. Ibid.

98. Bartusevičius and Skaaning, ‘Revisiting Democratic Civil Peace’; Francois et al., ‘Revolutionary Attitudes’.

99. Maekawa et al., ‘UN Involvement’.

100. For instance, Palmer et al., ‘What’s Stopping You?’; Beck et al., ‘New Tools in Comparative Political Economy’.

101. For instance, Bertoli et al., ‘Is There a War Party?’; Clare, ‘Ideological Fractionalization’.

102. Maoz, ‘Peace-building with the Hawks’.

103. Liendo and Braithwaite, ‘Determinants of Colombian Attitudes’.

104. Ibid.

105. Mac Ginty, ‘Time, Sequencing and Peace Processes’.

106. Hauenstein and Joshi, ‘Remaining Seized of the Matter’.

107. Lundgren, ‘Conflict Management Capabilities’.

108. Ibid.

109. Paris, ‘Saving Liberal Peacebuilding’.

110. Paris, ‘Saving Liberal Peacebuilding’; Mac Ginty, ‘No War, No Peace’.

References

- Ahamadov, Anar K. and James Huges, 2019. ‘Ideology and Civilian Victimization in Northern Ireland’s Civil War’. Irish Political Studies 35(4), 531–565.

- Arena, Philip and Glenn Palmer, 2009. ‘Politics or the Economy? Domestic Correlates of Dispute Involvement in Developed Democracies’. International Studies Quarterly 53(4), 955–975.

- Badran, Ramzi, 2014. ‘Intrastate Peace Agreements and the Durability of Peace’. Conflict Management and Peace Science 31(2), 193–217.

- Bartusevičius, Henrikas and Svend-Erik Skaaning, 2018. ‘Revisiting Democratic Civil Peace: Electoral Regimes and Civil Conflict’. Journal of Peace Research 55(5), 625–640.

- Beck, Thorsten, George Clarke, Alberto Groff, Philip Keefer and Patrick Walsh, 2001. ‘New Tools in Comparative Political Economy: The Database of Political Institutions’. The World Bank Economic Review 15(1), 165–176.

- Bell, Christine and Laura Wise, 2022. ‘Peace Processes and Their Agreements’. In Contemporary Peacemaking: Peace Processes, Peacebuilding and Conflict, eds. Roger Mac Ginty and Anthony Wanis-St. John. Springer Nature, Gewerbestrasse, 381–406.

- Berrebi, Claude and Esteban F. Klor, 2008. ‘Are Voters Sensitive to Terrorism? Direct Evidence from the Israeli Electorate’. American Political Science Review 102(3), 279–301.

- Bertoli, Andrew, Allan Dafoe and Robert F. Trager, 2019. ‘Is There a War Party? Party Change, the Left-Right Divide, and International Conflict’. Journal of Conflict Resolution 63(4), 950–975.

- Blum, Johannes and Niklas Potrafke, 2020. ‘Does a Change of Government Influence Compliance with International Agreements? Empirical Evidence for the NATO Two Percent Target’. Defence and Peace Economics 31(7), 743–761.

- Böller, Florian, 2022. ‘Fuelling Politicisation: The AfD and the Politics of Military Interventions in the German Parliament’. German Politics, 1–23.

- Braniff, Máire, 2012. ‘After Agreement: The Challenges of Implementing Peace’. Shared Space 14, 15–28.

- Brender, Agnes, 2018. ‘Government Ideology and Arm Exports’. ILE Working Paper No. 21. Institute of Law and Economics: University of Hamburg.

- Budge, Ian, Lawrence Ezrow and Michael D. McDonald, 2010. ’Ideology, Party Factionalism and Policy Change: An Integrated Dynamic Theory’. British Journal of Political Science 40(4), 781–804.

- Chakma, Anurug, 2023. ‘Leadership Changes and Civil War Peace Agreements: Does Who Comes to Power Influence the Implementation?’ International Peacekeeping 30(1), 24–52.

- Clare, Joe, 2010. ‘Ideological Fractionalization and the International Conflict Behaviour of Parliamentary Democracies’. International Studies Quarterly 54(4), 965–987.

- Clare, Joe, 2014. ‘Hawks, Doves and International Cooperation’. Journal of Conflict Resolution 58(7), 1311–1337.

- Collier, Paul and Nicholas Sambanis, 2002. ‘Understanding Civil War: A New Agenda’. Journal of Conflict Resolution 46(1), 3–12.

- Danzell, Orlandrew E, 2011. ‘Political Parties: When Do They Turn to Terror?’ Journal of Conflict Resolution 55(1), 85–105.

- De Donder, Philippe and Jean Hindriks, 2007. ‘Equilibrium Social Insurance with Policy-Motivated Parties’. European Journal of Political Economy 23(3), 624–640.

- De Mesquita, Beuno Bruce, Alastair Smith, Randolph M. Siverson and James D. Morrow, 2003. The Logic of Political Survival. The MIT Press, Cambridge.

- DeRouen, Karl, Jr, Mark J. Ferguson, Samuel Norton, Young Hwan Park, Jenna Lea and Ashley Streat-Bartlett, 2010. ‘Civil War Peace Agreement Implementation and State Capacity’. Journal of Peace Research 47(3), 333–346.

- Duffy Toft, Monica, 2002. ‘Indivisible Territory, Geographic Concentration, and Ethnic War’. Security Studies 12(2), 82–119.

- Duursma, Allard and Feike Fliervoet, 2021. ‘Fuelling Factionalism? The Impact of Peace Processes on Rebel Group Fragmentation in Civil Wars’. Journal of Conflict Resolution 65(4), 788–812.

- Fearon, James D. and David D. Laitin, 2003. ‘Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War’. American Political Science Review 97(1), 75–90.

- Fjelde, Hanne, Carl Henrik Knutsen and Håvard Mokleiv Nygård, 2021. ‘Which Institutions Matter? Re-Considering the Democratic Civil Peace’. International Studies Quarterly 65(1), 223–237.

- François, Abel, Raul Magni-Berton and Simon Varaine, 2021. ‘Revolutionary Attitudes in Democratic Regimes’. Political Studies 69(2), 214–236.

- Getmansky, Anna and Thomas Zeitzoff, 2014. ‘Terrorism and Voting: The Effect of Rocket Threat on Voting in Israeli Elections’. American Political Science Review 108(3), 588–604.

- Graham, Jesse, Jonathan Haidt and Brian A. Noesk, 2009. ‘Liberals and Conservatives Rely on Different Sets of Moral Foundations’. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 96(5), 808–822.

- Greene, Zachary D. and Amanda A. Licht, 2018. ‘Domestic Politics and Changes in Foreign Aid Allocation: The Role of Party Preferences’. Political Research Quarterly 71(2), 284–301.

- Grieco, Joseph M., Christopher F. Gelpi and T. Camber Warren, 2009. ‘When Preferences and Commitments Collide: The Effect of Relative Partisan Shifts on International Treaty Compliance’. International Organization 63(2), 341–355.

- Gul, Ferdinand A., Jyotirmoy Podder and Abu Zafar M. Shahriar, 2017. ‘Performance of Microfinance Institutions: Does Government Ideology Matter?’ World Development 100, 1–15.

- Gurses, Mehmet, Aimee Arias and Jeffrey Morton, 2020. ‘Women and War: Women’s Rights in Post-Civil War Society’. Civil Wars 22(2–3), 224–242.

- Hartzell, Caroline A., Mathew Hoddie and Donald Rothchild, 2001. ‘Stabilizing the Peace After Civil War: An Investigation of Some Key Variables’. International Organizations 55(1), 183–208.

- Hauenstein, Matthew and Madhav Joshi, 2020. ‘Remaining Seized of the Matter: UN Resolutions and Peace Implementation’. International Studies Quarterly 64(4), 834–844.

- Imbeau, Louis M., François Pétry and Moktar Lamari, 2001. ‘Left-Right Party Ideology and Government Policies: A Meta-Analysis’. European Journal of Political Research 40(1), 1–29.

- Jarland, Julie, Håvard Mokleiv Nygård, Scott Gates, Emilie Hermansen and Vilde Bergstad Larsen, 2020. ‘How Should We Understand Patterns of Recurring Conflict?’ Conflict Trends 3, 1–4.

- Joshi, Madhav, Sung Yong Lee and Roger Mac Ginty, 2017. ‘Built-In Safeguards and the Implementation of Civil War Peace Accords’. International Interactions 43(6), 994–1018.

- Joshi, Madhav and Jason Michael Quinn, 2015. ‘Implementing the Peace: The Aggregate Implementation of Comprehensive Peace Agreements and Peace Duration After Intrastate Armed Conflicts’. British Journal of Political Science 47(4), 869–892.

- Joshi, Madhav, Jason Michael Quinn and Patrick M Regan, 2015. ‘Annualized Implementation Data on Comprehensive Intrastate Peace Accords, 1989–2012’. Journal of Peace Research 52(4), 551–562.

- Kerreth, Johannes, Jason Quinn, Madhav Joshi and Jaroslav Tir, 2022. ‘International Third Parties and the Implementation of Comprehensive Peace Agreements After Civil War’. Journal of Conflict Resolution 67(2–3), 494–521.

- Kim, Eun Kyung, 2019. ‘Issue Ownership and Strategic Policy Choice in Multiparty Africa’. Politics & Policy 47(5), 956–983.

- Koch, Michael T. and Skyler Cranmer, 2007. ‘Testing the “Dick Cheney” Hypothesis: Do Governments of the Left Attract More Terrorism Than Governments of the Right?’ Conflict Management and Peace Science 24(4), 311–326.

- Koch, Michael T. and Patricia Sullivan, 2010. ‘Should I Stay or Should I Go Now? Partisanship, Approval, and the Duration of Major Power Democratic Military Interventions’. The Journal of Politics 72(3), 616–629.

- Krause, Jana, Werner Krause and Piia Bränfors, 2018. ‘Women’s Participation in Peace Negotiations and the Durability of Peace’. International Interactions 44(6), 985–1016.

- Liendo, Nicolás and Jessica Maves Braithwaite, 2018. ‘Determinants of Colombian Attitudes Toward the Peace Process’. Conflict Management and Peace Science 35(6), 622–636.

- Lundgren, Magnus, 2016. ‘Conflict Management Capabilities of Peace-Brokering International Organizations, 1945–2010: A New Dataset’. Conflict Management and Peace Science 33(2), 198–223.

- Mac Ginty, Roger, 2010. ‘No War, No Peace: Why so Many Peace Processes Fail to Deliver Peace’. International Politics 47(2), 145–162.

- Mac Ginty, Roger, 2022. ‘Time, Sequencing and Peace Processes’. In Contemporary Peacemaking: Peace Processes, Peacebuilding and Conflict, eds. Roger Mac Ginty and Anthony Wanis-St. John. Springer Nature, Gewerbestrasse, 181–195.

- Maekawa, Wakako, Barış Arı and Theodora-Ismene Gizelis, 2019. ‘UN Involvement and Civil War Peace Agreement Implementation’. Public Choice 178(3–4), 397–416.

- Maoz, Ifat, 2003. ‘Peace-Building with the Hawks: Attitude Change of Jewish-Israeli Hawks and Doves Following Dialogue Encounters with Palestinians’. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 27(6), 701–714.

- Mason, T. David, 2009. ‘International Relations Theory and How Civil Wars End’. International Interactions 25(3), 341–351.

- Mason, T. David and J. Michael Greig, 2017. ‘State Capacity, Regime Type, and Sustaining the Peace After Civil War’. International Interactions 43(6), 967–993.

- Mattes, Michaela, Brett Ashley Leeds and Naoko Matsumura, 2016. ‘Measuring Change in Source of Leader Support: The CHISOLS Dataset’. Journal of Peace Research 53(2), 259–267.

- Mattes, Michaela and Burcu Savun, 2009. ‘Fostering Peace After Civil War: Commitment Problems and Agreement Design’. International Studies Quarterly 53(3), 737–759.

- Mattes, Michaela and Jessica L. P. Weeks, 2019. ‘Hawks, Doves, and Peace: An Experimental Approach’. American Journal of Political Science 63(1), 53–66.

- Maynard, Jonathan Leader, 2019. ‘Ideology and Armed Conflict’. Journal of Peace Research 56(5), 635–649.

- Muñoz Fuerte, Manuela, 2018. ‘Why Oppose a Peace Agreement? The Relationship Between Belief Systems, Informational Shortcuts, and Attitudes Towards the 2016 Referendum in Colombia’. Available at: https://repositorio.uniandes.edu.co/handle/1992/40729

- Palmer, Glenn, Tamar London and Patrick Regan, 2004. ‘What’s Stopping You? The Sources of Political Constraints on International Conflict Behaviour in Parliamentary Democracies’. International Interactions 30(1), 1–24.

- Paris, Roland, 2010. ‘Saving Liberal Peacebuilding’. Review of International Studies 36(2), 337–365.

- Pettersson, Therése, Stina Högbladh and Magnus Öberg, 2019. ‘Organized Violence, 1989–2019’. Journal of Peace Research 57(4), 597–613.

- Potrafke, Niklas, 2010. ‘The Growth of Public Health Expenditures in OECD Countries: Do Government Ideology and Electoral Motives Matter?’ Journal of Health Economics 29(6), 797–810.

- Rathbun, Brian C, 2004. Partisan Interventions: European Party Politics and Peace Enforcement in the Balkans. Cornell University Press, New York.

- Regan, Patrick M., 1996. ‘Conditions of Successful Third-Party Intervention in Intrastate Conflicts’. Journal of Conflict Resolution 40(2), 336–359.

- Ryckman, Kirssa Cline and Jessica Maves Braithwaite, 2020. ‘Changing Horses in Midstream: Leadership Changes and the Civil War Peace Process’. Conflict Management and Peace Science 37(1), 83–105.

- Sandal, Nukhet and Neophytos Loizides, 2013. ‘Center-Right Parties in Peace Processes: “Slow Learning” or Punctuated Peace Socialization?’ Political Studies 61(2), 401–421.

- Sanı´n, Francisco Gutie´rrez and Elisabeth Jean Wood, 2014. ‘Ideology in Civil War: Instrumental Adoption and Beyond’. Journal of Peace Research 51(2), 213–226.

- Sela, Avraham, 2009. ‘Difficult Dialogue: The Oslo Process in Israeli Perspective’. Macalester International 23, 105–138.

- Stedman, Stephen John and Donald Rothchild, 2013. ‘Peace Operations: From Short-Term to Long-Term Commitment’. In Beyond the Emergency: Development within UN Peace Missions, ed. Jeremy Ginifer. New York: Routledge, 17–35.

- Stravers, Andrew, 2018. ‘Pork, Parties and Priorities: Partisan Politics and Overseas Military Deployments’. Conflict Management and Peace Science 38(2), 156–177.

- Tavits, Margit and Natalia Letki, 2009. ‘When Left is Right: Party Ideology and Policy in Post-Communist Europe’. American Political Science Review 103(4), 555–569.

- Thaler, Kai M, 2012. ‘Ideology and Violence in Civil Wars: Theory and Evidence from Mozambique and Angola’. Civil Wars 14(4), 546–567.

- Toft, Monica Duffy, 2002. ‘Indivisible Territory, Geographic Concentration, and Ethnic War’. Security Studies 12(2), 82–119.

- Torgovnik, Efraim, 2000. ‘Strategies Under a New Electoral System: The Labor Party in the 1996 Israeli Elections’. Party Politics 6(1), 95–106.

- Ugarriza, Juan E. and Matthew J. Craig, 2013. ‘The Relevance of Ideology to Contemporary Armed Conflicts: A Quantitative Analysis of Former Combatants in Colombia’. Journal of Conflict Resolution 57(3), 445–477.

- Vreeland, James Raymond, 2008. ‘The Effect of Political Regime on Civil War: Unpacking Anocracy’. Journal of Conflict Resolution 52(3), 401–425.

- Walter, Barbara F., 2004. ‘Does Conflict Beget Conflict? Explaining Recurring Civil War’. Journal of Peace Research 41(3), 371–388.

- Walter, Barbara F., 2009. ‘Bargaining Failures and Civil War’. Annual Review of Political Science 12(1), 243–261.

- Whitten, Guy D. and Laron K. Williams, 2011. ‘Buttery Guns and Welfare Hawks: The Politics of Defense Spending in Advanced Industrial Democratic Countries’. American Journal of Political Science 55(1), 117–134.

- Wood, Reed M. and Jakana L. Thomas, 2017. ‘Women on the Frontline: Rebel Group Ideology and Women’s Participation in Violent Rebellion’. Journal of Peace Research 54(1), 31–46.

- The World Bank, 2022. ‘World Development Indicators’. Available at: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators

Appendices

Appendix A

Table A1. Results of the t-test on the left-wing chief executives and peace agreement implementation.

Appendix B

Table B1. Results of the t-test on the right-wing chief executives and peace agreement implementation.

Appendix C

Table C1. Results of the t-test on the left-wing largest government parties and peace agreement implementation.

Appendix D

Table D1. Results of the t-test on the right-wing largest government parties and peace agreement implementation.