ABSTRACT

Existing educational and social inequalities within colonised nations have been amplified by multitudinous health, racial, climate, and social crises. It is a time to act collectively and boldly pivot towards equitable, socially-just futures. This perspective article contextualises schools within a social eco-system contending with the convergence of childhood adversity, pandemics, increasing climate, human-rights, political, and economic crisis around the globe. Profound uncertainty has shaken the expectations and systems that have been relied-on by those communities which they privilege. We call for educators to apply a transformative praxis with critical and cultural pedagogy to disrupt the educational status-quo that privileges Western-colonial epistemologies – knowledge and ways of knowing; the ‘whitewashing’ of schools and curriculums. Leveraging comprehensively applied trauma-informed principles within a social justice agenda is presented as a way of positioning schools to be way-finders and change-makers as they partner with communities. The time is now to (re)construct a fully rights-based school (r)evolution. Humility and courage will be required to lean into the hard questions and challenges; to revolutionise and humanise education. This paper presents schools as potential truth-hearing and historical truth-telling agents of urgent social change building communities of healing and audacious hope, led by communities.

We do not remain untouched by crisis. The global confluence of health, social, humanitarian, economic, and environmental crises continue. These have, and continue, to exact an enormous human toll. The UN Humanitarian Data Exchange (Citation2024, 1) reports One in 73 people worldwide is now displaced. This figure has doubled in the past 10 years, nearly one child in every five worldwide is living in, or has fled from, conflict zones, and 258 million people face acute hunger. During the pandemic years (primarily 2020–2022) across the world multitudes isolated at home ‘sheltering in place’ attempting to slow the spread of the deadly COVID-19 (CoV) pandemic. School closures alone impacted 80% of the world’s school children. Relentless pressure and uncertainty affected health and mental health in unprecedented ways (OECD Citation2020; UNESCO Citation2020) and exposed deep pre-existent chasms of oppression and injustice created by Euro-Western systems. From such extensive suffering and loss, an irreconcilable outcome would be to remain as societies, unchanged. The question is, whatever our role in education, health, or social care, will these harms awaken a response in and from us; one that sustains? This is a time for total re-calibration, healing and restoring individuals and communities facing collective burden and critical need. We believe that schools can emerge with insight and a hunger for bettering that reaches far beyond raising academic grade-levels, to fuelling a collectivist movement for social justice, equity, and relational connection.

As a team of researchers (she/they) working across health, disability, education, and social care, we bring to you our combined perspectives from varied knowledges: interwoven Aboriginal, immigrant, coloniser, and European cultural heritages. We sense a shift in the wind, a change towards community led and ‘partnered’ schooling (r)evolution, challenging systemic levels of injustice and re-empowering the disempowered. This period calls us to ‘Ka mua, ka muri’, (Māori proverb); to look back in order to move forward, as the anchor of a transformational education and social journey. A journey where harms, inhumanity, and gross injustices are recognised by dominant peoples and systems. A journey of knowledge-humility, deep listening to non-majority voice(s). A journey of self-reflection and humility-centred partnering with communities in devolving the status quo, and the (re)evolving of cultural wealth, critical pedagogies, and methodologies. We believe that critical inquiry and reflexivity can create a seismic shift towards mutuality and a seismic growth in hearts – elevating divergence.

Intersecting adversities and inequities

Embarking on a (r)evolutionary and transformative journey is one we contend is best supported by the energy of hope. However, before we wrestle with this concept, it is necessary to recognise and acknowledge the specific ways that historic oppression has manifested throughout the global pandemic. We will then turn towards the ways disenfranchised communities have continued to initiate change and generate knowledge on ways to address the systemic issues of our time. The burdens of the pandemic were not equally shared. Pre-existing inequities amassed atop historic personal and collective experiences of trauma and oxidative stress. Enduring injustices – many the legacy of colonisation and slavery – are evidenced in rampant racism (James Citation2020), the grossly disproportionate Black and Indigenous experience of violence from law-enforcement (as tragically evidenced in the murder of George Floyd), disproportionate incarceration rates and deaths in custody (International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs Citation2021; Nellis Citation2021), refugee and immigrant crises, war and conflict (Drane, Vernon, and O’Shea Citation2021; Whitaker Citation2020), and the ongoing over-representation of Indigenous and Black children in Western, statutory child protection systems (Dettlaff and Boyd Citation2021; Liddle et al. Citation2021; Waitangi Tribunal Citation2021). The rapid globalisation of the Black Lives Matter movement bears witness to the global canker that is racism (Ladson-Billings Citation2021; Shah and Shaker Citation2020). There is a terrible toll, an ever-escalating allostatic load for generations of colonised and non-dominant cultures enduring racialised disadvantage, systemic violence, and oppression; eroding scarce resources in disempowered communities; amidst relentless exposure to media that centre-stages and recycles devastation and vulnerability, underwriting a visual soundscape of fear and powerlessness, offering little hope and even less change.

Interconnectivity: trauma, social justice, and education

As educators strive to support students through chronic uncertainty it is essential that we understand pre-existing stressors as well as the impact of childhood adversity and trauma in the present, and the many ways in which social injustice underpins, amplifies, and perpetuates adversity. This knowledge will influence decisions made and actions taken. As defined by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA Citation2014) there is potential for trauma to result from:

an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life-threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual wellbeing. (7)

Trauma is both a universal and an alarmingly prevalent human experience (Clinton Citation2020; SAMHSA, Citation2022). Extensive research connects early years adversity, toxic stress, persistent fear, and anxiety, with decreased wellbeing, poor educational outcomes (Perfect et al. Citation2016), compromised health and employment (Merrick et al. Citation2019), and increased incarceration and drug and alcohol issues (Shonkoff, Slopen, and Williams Citation2021). CoV undeniably exacerbated social disadvantage; however, it also created experiences of adversity for children, evidenced in escalating rates of family violence, suicide, anxiety, and depression (Leeb et al. Citation2020), compounded by long periods of home-isolation. Social fault-lines have intensified, born out of severe economic stressors and relentless uncertainty. Children caught in spiralling disadvantage shouldered untenable burdens and loss.

The reach and impact of co-occurring crises have reached unfathomable levels, what is unseen and underreported is the devastating pandemic of childhood adversity that spans generations. Pre-Covid, two out of three school-aged children in the US had experienced or witnessed harms such as chronic bullying, abuse, neighbourhood violence, loss of loved-ones, poverty, homelessness, having a family member with a mental health or substance use disorder, discrimination, racism, terrorism or natural disaster (NCTSN Citation2017), with evidence indicating that exposure to one trauma increases the likelihood of experiencing other traumas (Asmussen et al. Citation2020). Such statistics are found across the world, upwards of 70% of Australian students have been exposed to one or more traumatic events, with a benchmark study (Scott and Matthews Citation2023) reporting that 62.2% of Australians have experienced multi-type maltreatment. Still higher rates of trauma are experienced by Australian Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander, and refugee populations (Emerging Minds Citation2020) impacted by collective and intergenerational trauma and a social context of colonisation and cultural oppression. Historic and systemic trauma includes the preferencing of colonised curriculum and pedagogy in schools, and reliance on western-dominent sciences. The magnitude of dominant-culture impact on children and families from non-dominant groups is poorly understood and barely recognised within education. The depth of impact cannot be overstated. It effects a child’s sense of personal value, identity, belonging, efficacy, safety and trust – elements that are fundamental to a student’s state of readiness to learn and problem-solve. Toxic stress that is linked to student adversity and perpetuated by a lack of understanding and responsivity in schools can account for high levels of student disconnection from education and poor academic and social outcomes; students not impacted by toxic stress are almost twice as likely to remain connected to education and experience success at school (Camp et al. Citation2022; Petrone and Rogers Stanton Citation2021).

The effects of CoV widened pre-existing disparities in access to mental health care for children of colour and children in low-income households. Key UK findings for children and young people include an 81% increase in referrals for children and young people’s mental health services between April – September 2021 (Iacobucci Citation2022). In the US from March 2020–October 2020, mental health-related emergency department visits increased 24% for children ages 5 to 11 and 31% for those aged 12 to 17 compared with 2019 (Leeb et al. Citation2020). Data on family violence (FV) indicate increases of 25% or more during CoV (Boserup, McKenney, and Elkbuli Citation2020), which can have devastating impacts on children into the future (Norbert et al. Citation2023; Queen Citation2023). The immense focus on CoV may have past and feel ‘old news’, however, trauma that has remained unaddressed and unprocessed will compound and further impact students, families, educators, and communities. The resources and energy that propelled changes in social services and education during CoV is waning in the wake of the economic flow-on effects and outbreaks of violence (Norbert et al. Citation2023). As a global community, we cannot afford the luxury of short memories. Certainly, those most impacted by CoV, environmental events, economic crisis, and war, do not have that luxury.

Missing in action: rights-based wholistic education

The human rights imperative for all children to access education that develops their capacities and personalities to their full potential (Universal Declaration of Human Rights Citation1948, Article 26) remains unfulfilled globally. The World Health Organisation (WHO) Global Standards for Health Promoting Schools declares health and education to be an interdependent basic human right for all, playing a vital role in the well-being of students, families, and their communities (WHO Citation2021). Nevertheless, educational efforts have not decreased disparities nor increased equal access to the improved prospects that educational achievement brings. Neither have endeavours to promote respect for human rights and tolerance among nations and social groups been achieved. Atrocities such as the forced removal of Native American children to boarding schools, and mission schools for Aboriginal Australians in the Stolen Generation is not distant history. Cycles of disadvantage are continuing. Student disparities are racialised and historically contextualised in the interaction between racism, education, poverty, health needs, and unsafe communities (Castrellón et al. Citation2021; Davis et al. Citation2022; Drane, Vernon, and O’Shea Citation2021). The educational debt owed to disempowered folx is exponentially compounding with major incongruities between those students that can and those that cannot consistently access internet, technology, or the physical environments amenable to learning online or otherwise (Beaunoyer, Dupéré, and Guitton Citation2020). To progress educationally students first need safety, shelter, and food security (González, Etow, and De La Vega Citation2019; A. P. Harris and Pamukcu Citation2019; Willis Citation2021), quality teachers and leaders in their community (Jones et al. Citation2021), sufficient school resources (Jones et al. Citation2021), and adequate access to healthcare (A. P. Harris and Pamukcu Citation2019; Healthy People Citation2020). Addressing these factors cannot be overlooked.

Education, politics, Power

Education is never neutral, it is political (Freire Citation1970). It can reinforce power structures and prevailing norms that oppress, or it can challenge thinking and espouse social transformation, personal freedoms, rights, and responsibilities towards each-other. The reality for each of us is to either be active supporters of equity or be oppressors via actions or inaction. There is no neutral position. Equitable education necessitates action against and action for, action against injustice and bias in all its forms and platforms, and the active pursuit of student health and wellbeing. Positioning Euro-Western knowledge in curricula and teaching practice has perpetuated dominant thinking and social inequities (Bang Citation2020). We continue to miss the mark, badly privileging a Eurocentric one-size-fits-all-badly delivery of education. This must change. We draw here on Bell’s (Citation2013) understanding that social justice is: ‘the full and equal participation’ of all students in education ‘that is mutually shaped to meet their needs’ and ‘includes a vision of society in which the distribution of resources is equitable and all members are physically and psychologically safe and secure’, where ‘individuals are both self-determining (able to develop their full capacities) and interdependent (capable of interacting democratically with others)’ (21). It also requires action inward (beliefs and prejudice) and action outward (systems, policies, practices). We must be open to interrogate a multitude of systemic contributors that limit prospects for students from minority groups, and structures that sustain dominant culture bias, inequities, and harms.

Equitable schools confront interpersonal, institutional, systemic racism, and bias as well as the beliefs, policies and practices that perpetuate harm to students and their families. These issues are not external to our schools. Sobering rates of implicit and explicit bias have been found within schools, including teacher beliefs and expectations related to gender, race, ethnicity, (dis)ability, and social-status of students (Sandoval Gomez and McKee Citation2020), and school discipline, exclusion and suspension policies and practices (Eley and Berryman Citation2021; McIntosh et al. Citation2021) that are undermining students at the most fundamental level of identity and sense of agency. Despite having empathy for students, educators from dominant cultures can struggle to see structural racism and fully appreciate patterns of injustice experienced by already marginalised students, disproportionately of colour (Jones et al. Citation2021), and the multiple ways that social injustice has amplified the impact of the pandemic. Socialised injustices cannot be rectified by focusing only on one domain, i.e.: policies or mandates. To change practice, it is attitudes and beliefs that must be challenged in a continual process of enquiry across socio-ecologically nested systems vertically and horizontally.

Navigating significant school change with transformative praxis

A transformative praxis of ‘reflection and action upon the world in order to transform it’ (Freire Citation1970, 36) is essential for meaningful, substantive change (Luitel and Dahal Citation2020). By transformative praxis we mean the pursuit of social change using theory-based educational practice and research to address ‘isms’ of race, sex, gender, able, and elite (J. Avery et al. Citation2022; Whitaker Citation2020). The Early Childhood Curriculum in Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ), Te Whāriki (the woven mat) was developed with such a praxis in mind. It draws on socioecological cultural theories and epistemic diversity: Sociocultural Theory (Vygotsky Citation1978); Kaupapa Māori Theory (R. Bishop Citation2005); Pasifika approaches (Hunter et al. Citation2016); and the use of Critical Theory (Fleming Citation2022). The title signifies weaving a mat, a collaborative endeavour which takes knowledge, skill, and time for strands to become interwoven and mutually reinforcing (Drew Citation2023). Indigenous cultures, including the Americans and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island Australians (Harrison and Greenfield Citation2011; McKinney de-Royson et al. Citation2020), conceptualise learning and teaching as interconnected. Māori refer to this spirit of inquiry as ako: the concept of learning that positions teachers as learners and students as teachers, drawing on reciprocity, respect, shared exploration, and collective sense-making prevalent in Indigenous strengths-based learning processes (Correa-Chávez and López-Freire Citation2019; Elliott-Groves, Meixi, and Citation2022). In contrast to Western assembly-line styles of instruction, learners are positioned as unique and culturally embedded (i.e., culture is the student’s context of life and cannot be separated out from who they are at school). They see their community reflected in what they learn, experiencing adult facilitation of their knowledge, skill, and valuable contribution to their community (Rogoff et al. Citation2017).

Shifting Western educational paradigms will require individual and collective openness to diverse worldviews and an increased cognitive flexibility towards difference. A process of listening to understand requires genuine humility in relation to truths and values divergent from our own. Indigenous traditions (e.g., Aboriginal Australian) draw on beliefs, knowledge-transference, spirituality, values, and understandings not commonly experienced in Westernised schools. An ontology of deep interconnection distinguishes Indigenous cultures around the world. While sharing commonalities of collective relationship with land, water, living and non-living things, Indigenous cultures commonly have distinctions across tribes or regions – overlooked by educators when they homogenise the lives and needs of Indigenous students, seeing deficit rather than diversity (Gutiérrez Citation2020). In contrast, schools authentically connected with their communities reflect local cultures using language, arts, and practices that respond to the similarities, differences, and strengths of student knowledge and cultural wealth (M. Bishop and Vass Citation2021; Blitz, Anderson, and Saastamoinen Citation2016).

From the ashes: a pedagogy of audacious hope

What we offer as audacious hope is a bold, contentious, active daring that envisions and evolves schools as spaces of safety, relationship, equity, inclusion, and cultural richness; communities with a collective desire to recognise and heal the pain of domination and cultural erasure. A reconciling theory of revolutionary change is needed in education if we are to reconfigure schooling at the fundamental levels of deep structure (Wollin Citation1999). An ideology of hope is controversial and complex. Impacted by positionality, hope may be considered on a spectrum of being a force for good or a political tool hindering the aspirations of oppressed communities and social equity (Fontanari Citation2019). Hope and hopelessness have all, in chameleon-esque ways, been catalysts for change (Herz, Lalander, and Elsrud Citation2022; Hooks Citation1990).

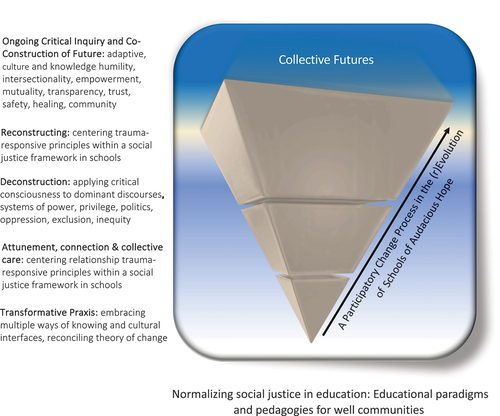

Audacious hope reflects the voice of disenfranchised, racialised, and marginalised folx we have been privileged to connect and collaborate with in diverse contexts, both formally (addiction, child protection services, (dis)ability services, education, family court, suicide prevention, and youth justice) and informally (within our communities). Marginalised children and adults spoke of hope in relation to personal and community agency and to witness systemic change; the empowerment of being visible: seen, heard, and authentically joined with. Audacious hope has an energy and emotion activating personal and collective dreaming into transformative change (). Hope is an ontological need; impacted by context and positionality (including race, class, gender, neurodiversity) that alters the experience of and response to it, as Gabriel Marcel’s phenomenology suggests (Szabat and Knox Citation2021). The significance of hope is best illustrated by those with least agency, the oppressed and segregated communities where hope has given rise to safe and humanising spaces created by Black, Indigenous, Latinx, LGBTQIA+ folx (Fránquiz, Ortiz, and Lara Citation2019; King Citation2022).

Audacious hope and humanising education systems

There will be ‘unlearning and growing pains’ for those yet to experience the essential inward (and life-long) process of uncovering personal bias and deficit thinking, most particularly for those yet to realise the subtlety of perpetuating power imbalances and injustice. There will be obstacles as we teach, lead, and research ‘against-the-grain’ and avoid the ‘reinscribing societal inequities’ (Cochran-Smith Citation2020, 51–52). We must deconstruct education practices and organisational structures that support exclusion, to reconstruct schools that provide counter-stress and relationally attuned environments. Activation of a transformative pedagogy would distinguish Schools of Audacious Hope (SoAH for brevity) from current educational practice by sharing agency with students, parents, guardians, communities, and Elders. Agency enables an active and energetic participation in transformational processes.

Adopting transformative pedagogy will account for how personal and organisational ways of being are socially and culturally determined, and inseparable from our ways of thinking. Educators and students would be ‘social actors who have a sense of their own agency as well as a sense of social responsibility toward and with others, their society, and the broader world in which we live’ (Bell Citation2013, 21). Students would be educated to ‘master and use their critical capacities’ (Freire Citation2021, 5), with room made for diverse enactments and displays of social responsibility. Echoing Freire’s (Citation1970) concept of praxis, Dabrowski (Citation2020) states, ‘the classroom offers a space for students to engage in critical and reflexive practice about what it means to engage with difference’ (2). School leaders would model how to make space for and negotiate differences. They would ‘impart knowledge of injustice, deficit-driven models, and ableism to promote a culture of equality and social justice’ throughout their school (Sandoval Gomez and McKee Citation2020, 2). Educators delivering on Freire’s conceptualisation will ‘actualize a humanizing pedagogy; engaging with their students in praxis, reflection, and action upon the world in order to transform it’ (Fránquiz, Ortiz, and Lara Citation2019, 382). These educators will interrogate the curriculum and recognise ‘social, political, and economic contradictions, and take action against the oppressive elements of reality’ (Freire Citation1970, 17).

The transformative pedagogy of audacious hope foregrounds possibility and empowers vision (Henry Giroux, in Freire Citation2021, 14). presents the participatory change process underpinning a deliberate and continuing intervention of knowledge selection and application to build political, social, and economic justice, and integrates the pedagogies of critical analysis, restorative practice, relational responsivity, Indigenous learning pedagogies and transformative praxis. As Lee (Citation2021) has concluded, the kinds of knowledge, inquiry, and discourse skills necessary for student’s civic engagement and social action are as follows:

intellectual dispositions and habits of mind; eagerness to engage with complex ideas, assess the credibility of evidence, explore multiple points of view, sift through moral and ethical dilemmas, empathise with people from differing backgrounds, and appreciate the power of literature and the arts to teach about others’ experiences and worldviews. (54)

This is more than utopian thinking, it is the better world we all hope to see, where children are nurtured through their schooling years with experiences of care, connectedness, relational repair, and mutual regard, building skills of co-enquiry and thoughtful debate as normative. Reconciliation skills would likewise be part of the curriculum and modelled by educators.

Carol Granison (Huggins Citation2021), sharing her teaching experience at the Oakland Community School asserted, ‘we need experiences of love in schools, where children learn to love themselves and others by having people [educators] that care about you’. We wholeheartedly agree. A study on the perspectives of students, parents, caregivers, educators, and community agencies regarding TR practice at a school for students with social-emotional and learning needs (J. C. Avery et al. Citation2023) found school stakeholders attributed connected community and attuned trustworthy relationships as pivotal to student engagement, learning and wellbeing. The safe to be vulnerable school culture was described as empowering: a community that built skills insight, empathy, and relational repair.

Renaissance of critical thinking and reflection

Integral to social change is our personal critiquing of truths constructed with our cultural, linguistic, social, and political influences (Brigg Citation2017; Sampson Citation1988). Whatever our role in education, research, system design or legislation, we must all engage in reflection on our own socialisation and continually seek to counter patterns of domination and injustice in schools and in the systems that we contribute to. Educators must ask each other and the school community – how is racism and inequity showing up here? This question would continue to be asked to identify and address all forms, implicit and explicit, actions and attitudes that persist and resist equity. Equally, we need to celebrate goodness: a daily practice of attuning to and articulating where, when, who, and how hope, kindness, empathy, compassion, trust, safety, and relationship are showing up. In this way we could commit to social justice, understanding that it necessitates togetherness. We need concerted and sustained effort, and collective actioning. The greatest challenge to such effort may be our ability (and willingness) to fully conceptualise schools as places of healing and hope.

Revolutionising schools: trauma-responsive social-justice focused practice

We propose that trauma-informed schools (referenced hereon as trauma-responsive [TR]) are well positioned to raise-up an educational (r)evolution towards schools that are socially informed, and advance healthy, thriving communities. A purposeful shift is made away from school climates and practices that are punitive, towards relational, strengths-based, and value-driven systems that prioritise the principles of safety, trustworthiness, transparency, voice and choice, collaboration and mutuality, and the empowerment of educators, students, families, and communities (M. Harris and Fallot Citation2001; SAMHSA Citation2014). TR actions and environments work proactively to prevent (re)traumatisation and to promote connection, personal growth, healing, and development of staff and students, and arguably all stakeholders of the school, to limit trauma-cycles. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN Citation2016, 1) define trauma-informed service providers as those who:

Build meaningful partnerships that create mutuality among children, families, caregivers, and professionals at an individual and organisational level.

Address the intersections of trauma with culture, history, race, gender, location, and language, acknowledge the compounding impact of structural inequity, and are responsive to the unique needs of diverse communities.

Theoretically, the comprehensive application of TR principles will give feet, hands, and voice to social justice and attend to personal, institutionalised, and systemic trauma (Ridgard et al. Citation2015). Decades of TR school developments and the extant literature have paid limited attention to equity and social justice concerns (J. C. Avery et al. Citation2021; Gherardi, Flinn, and Jaure Citation2020; Temkin et al. Citation2020).

Key elements of TR and social justice informed school practice include safety, relationality, cultural and knowledge humility, critical inquiry, reflection, empowerment, voice, equity, inclusivity, mutuality, transparency, collective responsibility, community engagement, and acknowledging oppression as trauma (J. Avery et al. Citation2022; J. C. Avery et al. Citation2021, Citation2023). These elements can be seen in several TR initiatives such as the ReLATE model (ReLATE Citationn.d.) in Australia and the Trauma-Sensitive Schools Flexible Framework of the Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative (S. F. Cole et al. Citation2013; TLPI Citationn.d.) although these initiatives, and most TR school approaches stop short of incorporating an explicit social justice agenda (Gherardi, Flinn, and Jaure Citation2020). This is curious given TR schools have typically been established in poor and vulnerable communities where dominant-culture beliefs and practices have created and compound inequities (Gherardi, Flinn, and Jaure Citation2020). Exceptions, where TR approaches incorporate a social justice agenda and community collaboration are emerging, including the New Orleans Trauma-Informed Schools Learning Collaborative utilising the Safe Schools NOLA project (SSNOLA) (Davis et al. Citation2022; Lazarus, Overstreet, and Rossen Citation2021) and the Chicago Public Schools (Citation2020) Equity Framework, to ‘critically examine and improve mindsets’ (2), resource-allocations, and policies.

We consider an explicit social-justice agenda and framework essential for conceptual and practice gains. In SoAH, such a tool would anchor transformational efforts and reduce risk of drift from central principles and core issues over time, supporting change by mapping the terrain schools need to (dis)cover and traverse, a journey led by and for the communities they serve. Community collaborations would build an understanding of historicity and challenge duplicities of institutional racism and ableism, and all forms of exclusion, injustice, and marginalisation (deMatthews, Serafini, and Watson Citation2021). Furthermore, a SoAH framework would protect against a deficit dialogue of trauma as a disorder within the child or family and drive an important narrative shift where trauma is understood as an adaptive survival-based response to a disordered environment (Rosenthal, Reinhardt, and Birrell Citation2016). It would offer a way of ‘seeing and acting’ aimed at both resisting and addressing what is unfair and oppressive in our systems and practice, proactively rectifying injustice and improving freedoms and opportunities. We see trauma-responsivity and social justice issues as so inextricably connected that we cannot achieve one without the other. A SoAH framework would centralise reflexivity and apply critical thinking to meaning-making, decision-making, and practice change, drawing on sources of expertise in community, and knowledges (such as indigenous pedagogy, inclusivity, and systems change), providing advice and support across unfamiliar terrain.

This is a journey towards shared humanity and deep respect for the values and the peoples of diverse communities and the environments that sustain us. Whether it is general school, specialist, or alternative education campus, the context of school-wide transformation need not preclude any type of learning environment journeying towards being relational, culturally responsive, and social-justice oriented. This (r)evolution is as personally challenging as it is systemically challenging. Thinking from critical pedagogy will lead us past our bias and help move towards insightful recognition of settler-educators’ position in the roots of injustice; erasure of culture, traditional knowledge, and language (Goodwin and Stanton Citation2022). Strength-based restorative practices bring mutual healing and future enabling practices across communities.

Welcoming dissonance

New cognitive spaces will be necessary to move forward. These will require deepened understanding of our own positionality and origins of our knowledgebase to fundamentally challenging our truths and the origins our own beliefs. Educators and researchers will need to incorporate funds of knowledge and identity pedagogy (Veerman et al. Citation2023) to see and utilise the education capital of students, families, and community in teaching and learning processes (Gilbert Citation2019; Moll Citation2019). Such interconnection of knowledges would minimise didactic teaching and broaden culturally connected learning thereby assisting students to link academic subject-learning and their cultural wealth and benefit from teaching paradigms other than Western oriented approaches (Rogoff et al. Citation2017). Such co-created funds of knowledge can build students’ sense of identity and agency and provide the space for ako: students as teachers – teachers as students. Central to this will be the ability to be embrace dissonance as an essential companion to learning, a ‘fluid knowing’ versus striving for authoritative meanings: the insistence that there is one way to understand. As expressed by Boelé (Citation2018, 72), ‘dissonance is necessary to dialogism, but it must emerge out of relations of care and the continuous effort of attunement’.

Educator training and development

We propose a call to action that enables all educators, new or experienced, to build skill in being curious and knowledge-humble; skilled at critiquing pedagogy, using transformative praxis, and drawing on critical theories which are mostly missing from educator training and research. Both pre-service teacher training and ongoing learning would build understanding and use of reflective practice and Indigenous pedagogies in education, including Critical Race Theory, Critical Race Feminism (Wing Citation1997), Latinx, and Disability Critical Race Theory (DisCrit). These analytical frameworks need a strong presence in training, pedagogy, and curriculum design, to deeply consider how racism and ableism operate interdependently, and often invisibly within the routines, policies, and procedures of schools to uphold dominant culture.

True partners

SoAH would act to humanise educational systems (Love Citation2019) to reconceptualise schools as places where children matter first and foremost (King Citation2022) elevating holistic child development over academic outputs. The cultural capital and personal experiences of students would be central in educational philosophy, encouraging them to use their experiential knowledge and positionality to learn, and to consider systemic structural constraints on equitable education and societies. Development of sociological imaginations in students, families, and educators could empower school communities to counter the neo-liberal ethos of competition and individualism (Hager, Peyrefitte, and Davis Citation2018) to centre collaborative learning and collective development.

There are many complexities and interacting elements in the co-creation of schools as places of healing. SoAH will proactively build environments that enhance well-being and safety – psychologically, spiritually, culturally, morally, socially, emotionally, and physically. As asserted by Venet (Citation2023, 180), ‘to be trauma informed is to be committed to the end of the conditions that cause trauma. When we make this commitment visible to our students, we become true partners in the work for justice’. This would be reflected in systemic changes which support educators to empathise, attune, and respond to students and families. Mindfulness of the load educators have carried during CoV (e.g., Baker et al. Citation2021), will be needed and awareness that educators will commonly have their own experiences of trauma or secondary traumatic stress from working with trauma-impacted students. Nurturing their recovery and ongoing wellbeing is essential.

Acknowledging the significant impact school leadership has on school culture, educator attitudes and beliefs (Hitt and Tucker Citation2016), SoAH would have actively supportive authoritative and empathic leadership modelling relational, TR and equity-focused practice. Such leaders will be clear communicators, involved, consistent, supportive, promoting wellbeing, holding high expectations for learning and reasoning to occur, and promoting autonomy in others (Bloom Citation2023, 77). Educator practice change would be supported by training, reflective supervision, coaching, and collaboration to support the energy and personal space needed to self-reflect, join transformative efforts, and communities of practice. Implementing these initiatives will require systemic support and legislation to ‘grant permission’ and to resource leaders to prioritise space for selfcare and reflective practice. Capacity-building for diverse school stakeholders (parents, community agencies) could sustain the change process and build collective efficacy (J and Braun Citation2019).

This transformative process will require educational courage which is not to ‘dig deep’ and carry on ‘disguised as resilience’ (anonymous reviewer). Rather than add to the oppressive workload of educators, SoAH will begin by attending to staff wellbeing and monitoring impact and pace of the change process. SoAH aspire to moving forward healing and equity-focused schools against the odds and will do this in ways that transform societies by transforming individuals, how we relate to each other and be in relationship. SoAH would actively eliminate the conditions that marginalise students. Educational leaders, administrators, curriculum designers and policy makers would confront attitudes, beliefs, policies, and funding, that perpetuate injustice and erasure of cultures (Gorski Citation2019). The teaching environment would be one of collegiality and collective care where teachers feel supported and ‘held’ in their efforts, struggles, and celebrations. Environments of care lighten the individual load for teachers and students and can result in a more productive and rewarding use of time (J. C. Avery et al. Citation2023).

Inspiring decolonising reforms

Rather than a colonial directional reform emanating from institutions to communities, authentic participatory change processes will embrace audacious hope in ways that (re)turn decision-making power to communities. Communities will be affirmed as initiators, experts and leaders who describe their vision of a thriving, healing, school climate: the shape a shared vision takes, and ways working collectively towards this shared vision would look and feel like. SoAH draw inspiration from grass-roots educational movements such as the beloved community phenomenon: the Oakland Community School, California, US 1971–82 initiated by the Black Panther movement with immense community support and reach, through ordinary people with a strong intention and a willingness to do what it takes (LeBlanc-Ernest Citation2018). The movement was about humanity, it understood that curriculum could be healing through building community, teaching true Black history, studying academic subjects in culturally relevant ways, building knowledge of self, and teaching students critical enquiry skills. Mottos used during generations of slavery, such as ‘Educate to Liberate’ and ‘Each-one Teach-one’ provided strong anchors in this initiative.

An educational revolution influencing the main author of this paper occurred in 1982 in Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ). Māori parents, having endured 120 years of colonised schooling, determined their children would be educated within a liberatory Māori worldview (Kaupapa Māori) and acted outside the law to turn-around the crises of educational underachievement and the loss of language, knowledge, and culture. Māori, in a self-determining manner, developed innovations based on Māori theory and practice transformation such as Te Kotahitanga (Bishop et al., Citation2014), an indigenous success story of creating conditions of learning and teaching that have raised Māori student outcomes. The core principles underpinning Kaupapa Māori, Aboriginal Australian, and Indigenous pedagogies generally, are reflected in emergent TR restorative socially-just practices (see Bishop and Vass Citation2021; González, Etow, and De La Vega Citation2019; Shriberg et al. Citation2019). Such principles are also found in studies of schools progressing equity in demographically diverse communities such as NYKids schools (Wilcox and Lawson Citation2022) the Chicago Public Schools, TLPI, ReLATE, and SSNOLA models.

Transformative journeying

Transformation is a process of growth and change that begins with listening and invites sharing. SoAH centre safety and trust, mutuality, mana (deep respect for individuals and their heritage), collaboration and power-sharing (Wilcox and Lawson Citation2022). Paradigm shifts, when initiated by educators, would authentically engage and listen to students, parents, and communities, asking who is around the decision-making table and who isn’t, but should be? To be safe and inclusive, educators must understand what this looks and feels like from the perspective of all stakeholders to buffer the impact of toxic stress and reduce sources of stress.

Educators, policy writers, and researchers will increase transparency, identifying assumptions through knowledge humility, co-inquiry, and collaboration. Authentic individual and systemic change progress with empathy, compassion, cohesion, and a vision of schools as responsive ecosystems within communities (Koslouski Citation2022). The River of Learning project in New South Wales, Australia is a community–school–university collaboration sustained over 10 years, an initiative of Yaegl Elders’ Maclean High-School teachers and Macquarie University’s National Indigenous Science Education Program. Students and staff visit local sites together and learn through Indigenous Knowledge about culture and science ‘taught two ways’ by Elders and science teachers (Papadopoulos Citation2021).

Curriculum and learning facilitation

SoAH will shift away from compliance-driven interactions to connection-driven interactions; core social centres co-constructing the future with students, families, communities, and between communities to nurture global-connectivity (Bang Citation2020). The Pottstown Trauma-Informed Community Connection (Champine et al. Citation2022), the Trauma Resilient Communities model (Vides et al. Citation2022), and the Australian Culture, Community and Curriculum Project (M. Bishop and Vass Citation2021) are examples of enacting a vision of collaborative capacity-building across diverse community members. Rather than privileging nationalist views (Lee Citation2021), curricula and assessment practices would be educationally relevant to students and continuously evolve to meet community needs. Integrated learning and teaching theory (seen in early childhood education) would support learning across multiple domains and knowledge connections, enabling multiple learning levels and age groups to learn together in shared spaces with collaborative teaching centring the student. Curricula would provide platforms to connect students from diverse cultures on a human level, developing concepts of global citizenship and student ability to attune to, critique, examine and challenge their world and their place in it (Alim, Paris, and Wong Citation2020; Lee, White, and Dong Citation2021).

Braided knowledge and ethical research

He Awa Whiria, the Braided Rivers Approach (Macfarlane and Macfarlane Citation2019), illustrates a dynamic, complex interaction between different knowledge bases, using the metaphor of two streams of a river with equal strength that start at the same place flowing alongside each other, coming together, and moving apart on the riverbed. As Superu (Citation2018) describes, each stream is predominantly separate, but when the streams of knowledge flow into each other a new learning space emerges. He Awa Whiria elevates Indigenous knowledge and enables authentic collaborations where Western and Kaupapa Māori research practices jointly guide programme evaluations and development (Trewartha Citation2020).

Research ideologies and methodologies must be critiqued via diverse funds of knowledge, ‘ecologies of knowledges’ and ‘radical copresence’ (de Santos Citation2014, 191), rather than in Western anchored motivations (Berryman, SooHoo, and Nevin Citation2013) to disrupt ‘either/or’ mindsets. An exception is found in Aotearoa NZ where culturally grounded approaches and power-sharing research frameworks are becoming the norm with Māori knowledge valued as integral to authoritative research paradigms (Macfarlane and Macfarlane Citation2019). Critical Race Feminism (Wing Citation1997) methodologies could also guide multi-disciplinary approaches to counter micro to macro levels of oppressive education through participant empowerment and centring lived experiences.

Garcia and Mirra (Citation2023) propose a paradigm of speculative education as ‘an exhortation to educational theory, research, and practice to think urgently and creatively about the worlds in which we currently find ourselves and the worlds we can learn to create’ (1). Multi-modal methodological approaches are suited to this work, including social design-based, ethnographic, case-studies, and Arts to gather stories and journeys, challenges, and enablers of change. Participatory processes and collaborative meaning-making would be focal. Participants would guide and contribute to the very language and ideology of research, which would ‘look beyond existing horizons’ (Garcia and Mirra Citation2023, 4) in education and be futuristic, expansive and invoke ‘collective dreaming’ of what could be. Within a TR-social justice framework, school climate and collective wellbeing (as perceived by diverse stakeholders), would be central to research investigation. Unit(s) of evaluation would be collectively defined and analysed, with findings translated into policies, procedures, and training requirements supported by funds channelled into what matters for communities. As Gorski (Citation2019, 4) asserts, ‘we cannot fix a problem (i.e., racism, injustice, bias) we refuse to name’.

As researchers, we need to listen in ways we may never have, to the voices of the disempowered and commit to understanding the roots of ‘isms. Working with the type of hope that believes what we do today will affect tomorrow. This is not fantastical thinking, it is ideology outworked in practice (J. C. Avery et al. Citation2023). It will require integrated efforts to drive change through changed hearts and minds (S. Cole Citation2019) to fuel this journey of courage. We believe the paradigms leading to injustice, oppression, division, and despair can be changed by educators leaning into the ‘radical hope’ expressed by Davis (Citation2022), building systems of ‘hope and happiness and social renewal’ (Ball Citation2016, 6) starting here, starting with you and me.

Outro

Our objective in this perspective is to call for courage to embark on a radical educational paradigm shift. Schools of audacious hope – underpinned by trauma responsive and equity-focused pedagogy – become socio-ecologically positioned change agents uniquely placed to counter experiences of adversity, social harms, and othering. Critical-thinking and transformative praxis will unlock mindsets and set hearts towards collectivity and connectivity. It is time to dream expansively of liberating restorative and healing experiences in schools where we can be unique and together. This is a pivotal moment for proactive and bold changes. We conclude with the opening line of the (unofficial) civil rights movement anthem:

People get ready, there’s a train a-comin’

Curtis Mayfield and ‘The Impressions’ 1965

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alim, H. S., D. Paris, and C. P. Wong. 2020. “Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy: A Critical Framework for Centering Communities.” In Handbook of the Cultural Foundations of Learning, edited by N. S. Nasir, C. D. Lee, R. Pea, and M. McKinneyde Royston, 261–276. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203774977.

- Asmussen, K., F. Fischer, E. Drayton, and T. McBride. 2020. Adverse Childhood Experiences: What We Know, What We don’t Know, and What Should Happen Next. Early Intervention Foundation. https://www.eif.org.uk/report/adverse-childhoodexperiences-what-we-know-what-we-dont-know-and-whatshould-happen-next.

- Avery, J., J. Deppeler, E. Galvin, H. Skouteris, P. Crain de Galarce, and H. Morris. 2022. “Changing Educational Paradigms: Trauma-Responsive Relational Practice, Learnings from the USA for Australian Schools.” Children & Youth Services Review 138:106506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106506.

- Avery, J. C., E. Galvin, J. Deppeler, H. Skouteris, J. Roberts, and H. Morris. 2023. “Raising Voice at School: Preliminary Effectiveness and Community Experience of Culture and Practice at an Australian Trauma-Responsive Specialist School.” Trauma Care 3 (4): 331–351. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare3040028.

- Avery, J. C., H. Morris, A. Jones, H. Skouteris, and J. Deppeler. 2021. “Australian educators’ Perceptions and Attitudes Towards a Trauma-Responsive School-Wide Approach.” Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma 15 (3): 771–785. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-021-00394-6.

- Baker, C. N., H. Peele, M. Daniels, M. Saybe, K. Whalen, S. Overstreet, and Trauma-Informed Schools Learning Collaborative The New Orleans. 2021. The Experience of COVID-19 and Its Impact on Teachers’ Mental Health, Coping, and Teaching, School Psychology Review 50 (4): 491–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2020.1855473.

- Ball, S. J. 2016. “Education, Justice and Democracy: The Struggle Over Ignorance and Opportunity.” In Reimagining the Purpose of Schools and Educational Organisations, edited by A. Montgomery and I. Kehoe. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24699-4_14.

- Bang, M. 2020. “Learning on the Move Toward Just, Sustainable, and Culturally Thriving Futures.” Cognition and Instruction 38 (3): 434–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2020.1777999.

- Beaunoyer, E., S. Dupéré, and M. J. Guitton. 2020. “COVID-19 and Digital Inequalities: Reciprocal Impacts and Mitigation Strategies.” Computers in Human Behavior 111:e106424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106424.

- Bell, L. A. 2013. “Theoretical Foundations.” In Readings for Diversity and Social Justice, edited by M. Adams, W. J. Blumenfeld, C. Castaneda, H. W. Hackman, M. L. Peters, and X. Zuniga, 21–26. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Berryman, M., S. SooHoo, and A. Nevin, Eds. 2013. Culturally Responsive Methodologies. Bingley UK: Emerald Publishing Group.

- Bishop, R. 2005. “Freeing Ourselves from Neo-Colonial Domination in Research: A Kaupapa Māori Approach to Creating Knowledge.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, 109–135. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Bishop, R., M. Berryman, and J. Wearmouth. 2014. Te Kotahitanga: Towards Effective Education Reform for Indigenous Minoritised Students. Wellington, NZ: New Zealand Council for Education Research Press.

- Bishop, M., and G. Vass. 2021. “Talking About Culturally Responsive Approaches to Education: Teacher Professional Learning, Indigenous Learners and the Politics of Schooling.” Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 50 (2): 340–347. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2020.30.

- Blitz, L. V., E. M. Anderson, and M. Saastamoinen. 2016. “Assessing Perceptions of Culture and Trauma in an Elementary School: Informing a Model for Culturally Responsive Trauma-Informed Schools.” The Urban Review 48 (4): 520–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-016-0366-9.

- Bloom, S. 2023, February 16. Biocratic Organizations and Creating PRESENCE. PowerPoint Slides and Audio] MacKillop Institute, Sanctuary Australian Network. https://www.creatingpresence.net.

- Boelé, A. L. 2018. “Hunting the Position: On the Necessity of Dissonance as Attunement for Dialogism in Classroom Discussion.” Linguistics and Education 45:72–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2018.04.001.

- Boserup, B., M. McKenney, and A. Elkbuli. 2020. “Alarming Trends in US Domestic Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 38 (12): 2753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.077.

- Brigg, M. 2017. “Engaging Indigenous Knowledges: From Sovereign to Relational Knowers.” Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 45 (2): 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2016.5.

- Camp, J. K., T. S. Hall, J. C. Chua, K. G. Ralston, D. F. Leroux, A. Belgrade, and S. Shattuck. 2022. “Toxic Stress and Disconnection from Work and School Among Youth in Detroit.” Journal of Community Psychology 50 (2): 876–895. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22688.

- Castrellón, L. E., É. Fernández, A. R. Reyna Rivarola, and G. R. López. 2021. “Centering Loss and Grief: Positioning Schools As Sites of Collective Healing in the Era of COVID-19.” Frontiers in Education 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.636993.

- Champine, R. B., E. E. Hoffman, S. L. Matlin, M. J. Stambler, and J. K. Tebes. 2022. ““What Does it Mean to Be Trauma-informed?”: A Mixed-Methods Study of a Trauma-Informed Community Initiative.” Journal of Child and Family Studies 31 (2): 459–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-02195-9.

- Chicago Public Schools. 2020. Chicago Public Schools (CPS) Equity Framework: Creating and Sustaining Equity at the Individual, School and District Level, Chicago, IL.

- Clinton, A. B. 2020, December 9. Scaling Up to Address Global Trauma, Loss, and Grief Associated with COVID-19. http://www.apa.org/international/global-insights/global-trauma.

- Cochran-Smith, M. 2020. “Teacher Education for Justice and Equity: 40 Years of Advocacy.” Action in Teacher Education 42 (1): 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/01626620.2019.1702120.

- Cole, S. 2019. How Can Educators Create Safe and Supportive School cultures?. Boston, MA: Massachusetts Advocates for Children.

- Cole, S. F., A. Eisner, M. Gregory, and J. Ristuccia. 2013. Helping Traumatized Children Learn:Creating and Advocating for Trauma-Sensitive Schools. Boston, MA: Massachusetts Advocates for Children.

- Correa-Chávez, M., and A. López-Freire. 2019. “Learning by Observing and Pitching In: Implications for the Classroom.” In Language and Cultural Practices in Communities and Schools: Bridging Learning for Students from Non-Dominant Groups, edited by I. M. Garcia-Sanchez and M. F. Orellana, 24–71. London: Routledge, Taylor and Francis.

- Dabrowski, A. 2020. “Teacher Wellbeing During a Pandemic: Surviving or Thriving?” Social Education Research 2 (1): 35–40. https://doi.org/10.37256/ser.212021588.

- Davis, D. M. 2022. “Paulo Freire.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Educational Thinkers, edited by B. A. Geier Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81037-5_142-1.

- Davis, W., L. Petrovic, K. Whalen, L. Danna, K. Zeigler, A. Brewton, M. Joseph, C. N. Baker, S. Overstreet, and the New Orleans Trauma‐Informed Learning Collaborative. 2022. “Centering Trauma‐Informed Approaches in Schools within a Social Justice Framework.” Psychology in the Schools 59 (12): 2453–2470. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22664.

- deMatthews, D. E., A. Serafini, and T. N. Watson. 2021. “Leading Inclusive Schools: Principal Perceptions, Practices, and Challenges to Meaningful Change.” Educational Administration Quarterly 57 (1): 3–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X20913897.

- de Santos, B. S. 2014. Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide. Boulder: Paradigm.

- Dettlaff, A. J., and R. Boyd. 2021. “Racial Disproportionality and Disparities in the Child Welfare System: Why Do They Exist, and What Can Be Done to Address Them?” American Academy of Political and Social Science 692 (1): 253–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716220980329.

- Drane, C. F., L. Vernon, and S. O’Shea. 2021. “Vulnerable Learners in the Age of COVID-19: A Scoping Review.” The Australian Educational Researcher 48 (4): 585–604. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-020-00409-5.

- Drew, C. January 20, 2023. Te Whàriki Curriculum: Strands and Principles. Helpful Professor. https://helpfulprofessor.com/te-whariki-curriculum-in-new-zealand/.

- Eley, E., and M. Berryman. 2021. “Paradigm Lost: The Loss of Bicultural and Relation-Centred Paradigms in New Zealand Education and Ongoing Discrepancies in students’ Experiences and Outcomes.” The New Zealand Annual Review of Education 25:95–114. https://doi.org/10.26686/nzaroe.v25.6962.

- Elliott-Groves Emma, Meixi. 2022. “Why and How Communities Learn by Observing and Pitching In: Indigenous Axiologies and Ethical Commitments in LOPI (Cómo Y Por qué Las Comunidades Aprenden Por Medio de Observar Y Acomedirse axiologíaxiologíAs indígenas Y Compromisos éticos En el Modelo LOPI).” Journal for the Study of Education & Development 45 (3): 567–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/02103702.2022.2062916.

- Emerging Minds. 2020. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES): Summary of Evidence and Impact. National Workforce Centre for Child Mental Health. https://emergingminds.com.au/resources/background-to-aces-and-impacts/.

- Fleming, T. 2022. “Transformative Learning and Critical Theory: Making Connections with Habermas, Honneth, and Negt.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Learning for Transformation, edited by A. Nicolaides, S. Eschenbacher, P. T. Buergelt, Y. Gilpin-Jackson, M. Welch, and M. Misawa. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-84694-7_2.

- Fontanari, E. 2019. Lives in Transit: An Ethnographic Study of Refugees, Subjectivity Across European Borders. London: Routledge.

- Fránquiz, M. E., A. A. Ortiz, and G. Lara. 2019. “Co-editor’s Introduction: Humanizing Pedagogy, Research and Learning.” Bilingual Research Journal 42 (4): 381–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2019.1704579.

- Freire, P. 1970. The Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York, NY: Seabury Press.

- Freire, P. 2021. The Pedagogy of the Hope: Reliving the Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Garcia, A., and N. Mirra. 2023. “Other Suns: Designing for Racial Equity Through Speculative Education.” Journal of the Learning Sciences 32 (1): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2023.2166764.

- Gherardi, S. A., R. E. Flinn, and V. B. Jaure. 2020. “Trauma-Sensitive Schools and Social Justice: A Critical Analysis.” The Urban Review 52 (3): 482–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-020-00553-3.

- Gilbert, S. 2019. “Living with the Past: The Creation of the Stolen Generation Positionality.” AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 15 (3): 226–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180119869373.

- González, T., A. Etow, and C. De La Vega. 2019. “Health Equity, School Discipline Reform, and Restorative Justice.” The Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics 47 (2_suppl): 47–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073110519857316.

- Goodwin, A. L., and R. Stanton. 2022. “Lessons from an Expert Teacher of Immigrant Youth: A Portrait of Social Justice Teaching.” Equity and Excellence Education 55 (1–2): 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2021.2021652.

- Gorski, P. 2019. “Avoiding racial equity detours.” Educational Leadership 76 (7): 56–61. http://edchange.org/publications/Avoiding-Racial-Equity-Detours-Gorski.pdf.

- Gutiérrez, K. D. 2020. “When Learning As Movement Meets Learning on the Move, Cognition and Instruction.” 38 (3): 427–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2020.1774770.

- Hager, T., M. Peyrefitte, and C. Davis. 2018. “The Politics of Neoliberalism and Social Justice: Towards a Pedagogy of Critical Locational Encounter.” Education, Citizenship and Social Justice 13 (3): 199–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197918793069.

- Harris, M., and R. D. Fallot. 2001. Envisioning a Trauma-Informed Service System: A Vital Paradigm Shift. In Using Trauma Theory to Design Service Systems, edited by, M. Harris and R. D. Fallot, 3–22. Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

- Harrison, N., and M. Greenfield. 2011. “Relationship to Place: Positioning Aboriginal Knowledge and Perspectives in Classroom Pedagogies.” Aboriginal Policy Research Consortium International APRCi:343. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/aprci/343.

- Harris, A. P., and A. Pamukcu. 2019. The Civil Rights of Health: A New Approach to Challenging Structural Inequality, UCLA Law Review. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3350597.

- Healthy People. 2020. Disparities. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/foundation-health-measures/.

- Herz, M., P. Lalander, and T. Elsrud. 2022. “Governing Through Hope: An Exploration of Hope and Social Change in an Asylum Context.” Emotions and Society 4 (2): 222–237. https://doi.org/10.1332/263169021X16528637795399.

- Hitt, D. H., and P. D. Tucker. 2016. “Systematic Review of Key Leader Practices Found to Influence Student Achievement: A Unified Framework.” Review of Educational Research 86 (2): 513–569. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315614911.

- Hooks, B. 1990. “Postmodern Blackness.” Postmodern Culture 1 (1). https://doi.org/10.1353/pmc.1990.0004.

- Huggins, E. 2021. “The World Is a child’s Classroom: Lessons from the Black Panther Party’s Oakland Community School.” The OCS Project. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y6x7cg1iOL8.

- Hunter, J., R. Hunter, T. Bills, I. Cheung, B. Hannant, K. Kritesh, and R. Lachaiy 2016. Developing Equity for Pāsifika Learners within a New Zealand Context: Attending to Culture and Values. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 5(1) 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40841-016-0059-7

- Iacobucci, G. 2022. “Covid-19: Pandemic Has Disproportionately Harmed children’s Mental Health, Report Finds.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 376:o430. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.o430.

- International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. 2021. Aboriginal People in Australia: The Most Imprisoned People on Earth. https://www.iwgia.org/en/news/4344-aboriginal-people-in-australia-the-most-imprisoned-people-on-earth.html.

- James, C. 2020. Racial Inequity, COVID-19 and the Education of Black and Other Marginalized Students. Department of Sociology, York University. https://rsc-src.ca/en/covid-19/impact-covid-19-in-racialized-communities/racial-inequity-covid-19-and-education-black-and.

- J, B., and K. L. Braun. 2019. “The Role of Collective Efficacy in Reducing Health Disparities: A Systematic Review.” Family and Community Health 42 (1): 8–19. https://doi.org/10.1097/FCH.0000000000000206.

- Jones, T. M., A. Diaz, S. Bruick, K. McCowan, D. W. Wong, A. Chatterji, A. Malorni, and M. S. Spencer. 2021. “Experiences and Perceptions of School Staff Regarding the COVID-19 Pandemic and Racial Equity: The Role of Colour-Blindness.” School Psychology 36 (6): 546–554. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000464.

- King, N. S. 2022. “Black Girls Matter: A Critical Analysis of Educational Spaces and Call for Community-Based Programs.” Cultural Studies of Science Education 17 (1): 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-022-10113-8.

- Koslouski, J. B. 2022. “Developing Empathy and Support for Students with the “Most Challenging behaviors:” Mixed-Methods Outcomes of Professional Development in Trauma-Informed Teaching Practices.” Frontiers in Education 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.1005887.

- Ladson-Billings, G. 2021. “I’m Here for the Hard Re-Set: Post Pandemic Pedagogy to Preserve Our Culture.” Equity & Excellence in Education 54 (1): 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2020.1863883.

- Lazarus, P. J., S. Overstreet, and E. Rossen. 2021. “Building a Foundation for Trauma‐Informed Schools.” In Fostering the Emotional Well‐Being of Our Youth: A School‐Based Approach , edited by P. J. Lazarus, B. Doll, and S. Suldo. 31–337. Online: Oxford Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/med-psych/9780190918873.001.0001.

- LeBlanc-Ernest, A. 2018. The Oakland Community School (OCS) Project. Themes of Black Radical Pedagogy: Part 1: The World Is a child’s classroom: Lessons from the Black Panther Party’s Oakland Community School. https://vimeo.com/629228694?embedded=trueandsource=vimeo_logoandowner=53559165.

- Lee, C. D. 2021. “Reimagining American Education: Possible Futures: A Curriculum That Promotes Civic Ends and Meets Developmental Needs.” Phi Delta Kappan 103 (3): 54–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/00317217211058526.

- Leeb, R. T., R. H. Bitsko, L. Radhakrishnan, P. Martinez, R. Njai, and K. M. Holland. 2020. “Mental Health–Related Emergency Department Visits Among Children Aged <18 Years During the COVID-19 Pandemic, United States, January 1–October 17 2020.” Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report 69 (45): 1675–1680. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6945a3.

- Lee, C. D., G. White, and D. Dong. 2021. Educating for Civic Reasoning and Discourse. Washington DC: National Academy of Education.

- Liddle, S. K., L. Robinson, S. A. Vella, and F. P. Deane. 2021. “Profiles of Mental Health Help Seeking Among Australian Adolescent Males.” Journal of Adolescence 92 (1): 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.08.010.

- Love, B. L. 2019. “The Spirit Murdering of Black and Brown Children.” Education Week 38 (35): 18–19.

- Luitel, B. C., and N. Dahal. 2020. “Conceptualising Transformative Praxis.” Journal of Transformative Praxis 1 (1): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3126/jrtp.v1i1.31756.

- Macfarlane, A., and S. Macfarlane. 2019. “Listen to Culture: Māori scholars’ Plea to Researchers.” Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 49 (sup1): 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2019.1661855.

- McIntosh, K., E. J. Girvan, S. Fairbanks Falcon, S. C. McDaniel, K. Smolkowski, E. Bastable, M. R. Santiago-Rosario, et al. 2021. “Equity-Focused PBIS Approach Reduces Racial Inequities in School Discipline: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” School Psychology 36 (6): 433–444. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000466.

- McKinney de-Royson, M. M., C. Lee, N. S. Nasir, and R. Pea. 2020. “Rethinking Schools, Rethinking Learning.” Phi Delta Kappan 102 (3): 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721720970693.

- Merrick, M. T., D. C. Ford, K. A. Ports, A. S. Guinn, J. Chen, J. Klevens, M. Metzler, et al. 2019. “Vital Signs: Estimated Proportion of Adult Health Problems Attributable to Adverse Childhood Experiences and Implications for Prevention — 25 States, 2015–2017.” Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report 68 (44): 999–1005. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6844e1.

- Moll, L. C. 2019. “Elaborating Funds of Knowledge: Community-Oriented Practices in International Contexts.” Literacy Research: Theory, Method, & Practice 68 (1): 130–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/2381336919870805.

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network. 2016. NCTSN Schools Committee. What Is a Trauma-Informed Child and Family Service System. Fact Sheet. https://www.nctsn.org/resources/what-trauma-informed-child-and-family-service-system.

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network. 2017. NCTSN Schools Committee. Creating, Supporting, and Sustaining Trauma-Informed Schools: A System Framework. Los Angeles, CA, and Durham, NC: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress.

- Nellis, A. 2021. The Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparity in State Prisons. The Sentencing Project – Research and Advocacy for Reform. https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/color-of-justice-racial-and-ethnic-disparity-in-state-prisons/.

- Norbert, S., A. Holla, S. Sabarwal, J. Silva, and A. Yi Chang. 2023. Collapse and Recovery: How the COVID-19 Pandemic Eroded Human Capital and What to Do About It Executive Summary Booklet. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2020. The impact of (COVID-19) on student equity and inclusion: Supporting vulnerable students during school closures and school re-openings. Paris: OECD. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=434_434914-59wd7ekj29&title=The-impact-of-COVID-19-on-student-equity-and-inclusion.

- Papadopoulos, T. April 14, 2021. Paving the Way for Educational Justice Through Reconciliation. Education Matters Magazine. https://www.educationmattersmag.com.au/outstanding-reconciliation-initiatives-at-mosman-park-primary-school/.

- Perfect, M. M., M. R. Turley, J. S. Carlson, J. Yohanna, and M. P. Saint Gilles. 2016. “School Related Outcomes of Traumatic Event Exposure and Traumatic Stress Symptoms in Students: A Systematic Review of Research from 1990–2015.” School Mental Health 8 (1): 7–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-016-9175-2.

- Petrone, R., and C. Rogers Stanton. 2021. “Producing to Reducing Trauma: A Call for “Trauma-Informed” Research(ers) to Interrogate How Schools Harm Students.” Educational Researcher 50 (8): 537–545. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X211014850.

- Queen, D. 2023. “COVID Consequences Continue.” International Wound Journal 20 (3): 615–616. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.14113.

- ReLATE. n.d. An Introduction to ReLATE: Reframing Learning and Teaching Environments. The MacKillop Institute. https://www.mackillop.org.au/institute/relate.

- Ridgard, T. J., S. D. Laracy, G. J. DuPaul, E. S. Shapiro, and T. J. Power. 2015. “Trauma-Informed Care in Schools: A Social Justice Imperative.” Communiqué (Milwaukee, Wis) 44 (2): 1–12.

- Rogoff, B., A. Coppens, L. Alcalá, I. Aceves-Azuara, O. Ruvalcaba, A. López, and A. Dayton. 2017. “Noticing learners’ Strengths Through Cultural Research.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 12 (5): 876–888. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617718355.

- Rosenthal, M. N., K. M. Reinhardt, and P. J. Birrell. 2016. “Guest Editorial: Deconstructing Disorder: An Ordered Reaction to a Disordered Environment.” Journal of Trauma and Dissociation 17 (2): 131–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2016.1103103.

- SAMHSA. 2022, April 22. Understanding Child trauma. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/child-trauma/understanding-child-trauma.

- Sampson, E. E. 1988. “The Debate on Individualism: Indigenous Psychologies of the Individual and Their Role in Personal and Societal Functioning.” The American Psychologist 43 (1): 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.43.1.15.

- Sandoval Gomez, A., and A. McKee. 2020. “When Special Education and Disability Studies Intertwine: Addressing Educational Inequities Through Processes and Programming.” Frontiers in Education 5:587045. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.587045.

- Scott, J. G., and B. Matthews. 2023. “Introducing the Australian Maltreatment Study: Baseline Evidence for a National Public Health Challenge.” The Medical Journal of Australia 218 (S6). https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.51867.

- Shah, V., and E. Shaker. 2020. Leaving Normal: Re-Imagining Schools Post-COVID and Beyond. https://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National%20Office/2020/06/OSOS-Summer2020.pdf.

- Shonkoff, J. P., N. Slopen, and D. R. Williams. 2021. “Early Childhood Adversity, Toxic Stress, and the Impacts of Racism on the Foundations of Health.” Annual Review of Public Health 42 (1): 115–134. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-101940.

- Shriberg, D., B. A. Baker, and H. E. Ormiston. 2019. “A Social Justice Framework for Teachers: Key Concepts and Applications.” In Encyclopedia of Teacher Education, edited by M. Peters. Singapore: Springer.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2014. Samhsa’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach (HHS Publication No) 14–4884. SMA). https://store.samhsa.gov/system/files/sma14-4884.pdf.

- Superu. 2018. Bridging cultural perspectives. Wellington: Social Policy Evaluation and Research Unit. Wellington, NZ. https://thehub.swa.govt.nz/.

- Szabat, M., and J. B. L. Knox. 2021. “Shades of Hope: Marcel’s Notion of Hope in End-Of-Life Care.” Med Health Care and Philosophy 24 (4): 529–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-021-10036-1.

- Temkin, D., K. Harper, B. Stratford, V. Sacks, Y. Rodriguez, and J. D. Bartlett. 2020. “Moving Policy Toward a Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child Approach to Support Children Who Have Experienced Trauma.” Journal of School Health 90 (12): 940–947. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12957.

- TLPI. n.d. Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative. https://traumasensitiveschools.org/about-tlpi/.

- Trewartha, C. 2020. “He Awa Whiria: Braiding the Rivers of Kaupapa Māori and Western Evidence on Community Mobilization.” Psychology Aotearoa 12 (1): 16–21. https://indd.adobe.com/view/c5ed9016-36ff-4fd8-bb6f-ba5825b3ecbd.

- UNESCO. 2020. “UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization school closure estimates.” https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30084-0.

- UN Humanitarian Data Exchange. 2024. Global Humanitarian Overview. https://data.humdata.org/dataset/6cb35657-975e-46a0-99a7-a558eddb924f.

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. 1948. Article 26. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights.

- Veerman, E., M. Karssen, M. Volman, and L. Gaikhorst. 2023. “The Contribution of Two Funds of Identity Interventions to Well-Being Related Student Outcomes in Primary Education.” Learning, Culture & Social Interaction 38:100680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2022.100680.

- Venet, A. S. 2023. Equity-Centered Trauma-Informed Education. Equity and Social Justice in Education Series, e-book ed. New York: Routledge. https://www.amazon.com/Equity-Centered-Trauma-Informed-Education-Equity-Justice/dp/039371473X.

- Vides, B., J. Middleton, E. E. Edwards, D. McCorkle, S. Crosby, B. A. Loftis, and G. Goggin. 2022. “The Trauma Resilient Communities (TRC) Model: A Theoretical Framework for Disrupting Structural Violence and Healing Communities.” Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma 31 (8): 1052–1070. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2022.2112344.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. London: Harvard University Press.

- Waitangi Tribunal. 2021. He pāharakeke, he rito whakakīkīnga whāruarua: Oranga Tamariki urgent inquiry. The National Library of New Zealand. https://www.natlib.govt.nz/records/45969211.

- Whitaker, M. C. 2020. “Us and Them: Using Social Identity Theory to Explain and Re-Envision Teacher–Student Relationships in Urban Schools.” The Urban Review 52 (4): 691–707. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-019-00539-w.

- WHO. 2021. Making Every School a Health-Promoting School: Global Standards and Indicators for Health-Promoting Schools and Systems, 1–40. Geneva: World Health Organization and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- Wilcox, K. C., and H. A. Lawson. 2022. “Advancing Educational Equity Research, Policy, and Practice.” Education Science 12 (12): 894. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120894.

- Willis, D. E. 2021. “Feeding Inequality: Food Insecurity, Social Status and College Student Health.” Sociology of Health and Illness 43 (1): 220–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13212.

- Wing, A. K. 1997. Critical race feminism: A reader. New York: NYU Press.

- Wollin, A. 1999. “Punctuated Equilibrium: Reconciling Theory of Revolutionary and Incremental Change.” Systems Research and Behavioural Science 16 (4): 359–367. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1743(199907/08)16:4<359:AID-SRES253>3.0.CO;2-V.