ABSTRACT

The corporate and global sector for university preparatory programmes, also known as international foundation programmes or embedded colleges, have been identified as examples of the commodification and marketisation of higher education. In this paper, I draw on an extensive set of interviews and documents to provide a more complete history of the market for corporate embedded colleges in England. I identify three distinct market stages that highlight key breaks in market structures, norms, and practices. The first market stage, spearheaded by American and Australian companies, is characterised by substantial growth and low recruitment costs. The second market stage spreads across all the major regions in England and is characterised by clearly recognised market players, regulation, and more direct forms of competition. The third market stage is characterised by higher recruitment costs and lower growth rates exposing the internal contradictions of the market. Taken together, I show how markets are distributed systems that vary across time and localities. Such a long-term perspective on education markets, I argue, can provide higher education stakeholders important counterpoints to short-termism and economisation.

Introduction

Public universities in England are self-governing institutions intended to protect and produce knowledge through their institutionalised practices: teaching students, conducting research, issuing degrees, running libraries, and much more. Over time, however, more and more practices have been outsourced to private providers. In England, domestic teaching of foundation programmes for international students who want to pursue degree studies at UK universities is a good case in point: teaching is delivered through ‘pathway programs’ at schools known as ‘embedded colleges’ that are owned by private companies. The industry started growing fast and gaining legitimacy from 2004 to the mid-2010s, partially because universities started to recognise that pathway partnerships could help them recruit more international students. The English market is today dominated by five incumbents: Study Group, INTO University Partnerships, Navitas, Kaplan International Pathways and Cambridge Education Group (CEG).

The rise in corporate pathways was encouraged by broader social changes (Komljenovic Citation2016): over the past four decades, English universities have been pressured to become more efficient and accountable, whilst their overall orientation to knowledge creation, circulation and curation has been narrowed into demonstrating relevancy to the new knowledge economy and its future workers and institutions (OECD Citation1996; Scott Citation1995). Such institutional developments have been framed by policy reforms and discourses encouraging a market-like organisation of, and competition between, universities (Collini Citation2011). As a result, funding provision for teaching has moved from mostly public grants to student fees. By 2020/2021, teaching allocations from funding councils were ‘79% below the 2010–2011 figure in real terms’ (Bolton Citation2021, 3) – which by itself is a testament to the important role markets play in coordinating and funding higher learning in present-day England.

Within this larger picture, teaching students that pay home-fees and conducting funded research tend to be profit-neutral or loss-making activities (Olive Citation2017; Willetts Citation2023), making students domiciled outside the United Kingdom increasingly important to university and public finances (House of Lords Citation2023). This has encouraged universities to ensure that they capture as many high-fee-paying students as possible in a way that aligns with their institution’s capacities and broader purposes. As such, international students’ human capital development and encouragement of social mobility through English universities has been co-opted into an lucrative export for the UK services economy (Robertson Citation2006). Corporate pathway firms contribute to this economy as market makers, recruiters and educators.

Existing research focusing only on embedded colleges remains limited and can be divided into three broad categories. First, researchers have investigated pathway student learning and experience (Agosti and Bernat Citation2018; Dooey Citation2010; Dunworth, Fiocco, and Mulligan Citation2012; Dyson Citation2014; Floyd Citation2015; Terraschke and Wahid Citation2011). While important, they do not deal with questions of privatisation, market making or ordering practices. Second, research and grey literature on pathways has been written by market actors and practitioners with professional identities deeply rooted in academia (Agosti and Bernat Citation2018; Cambridge English & StudyPortals Citation2016, Citation2015; Choudaha Citation2017; Cunnington Citation2019). They provide insights into how pathway colleges operate but remain largely uncritical in questioning why and how these practices emerged over time. Finally, a clutch of research on embedded colleges has focused on policy, governance, and markets (Fiocco Citation2005; Gillett Citation2011; Komljenovic Citation2016; McCartney and Metcalfe Citation2018; Tamtik Citation2022; Winkle Citation2014).

I extend these studies by engaging more fully and directly with investors and corporate executives working in the pathway sector, and by giving the first comprehensive account of the emergence of the English market. Drawing on 36 semi-structured elite interviews (Harvey Citation2010), this study documents and theorises the market formation of corporate embedded colleges in England. My sample consists of seven university leaders, eight university staff members, six corporate pathway staff members, seven corporate pathway executives, four investors and five representatives of public alternatives to corporate pathways.

In my analysis, I see markets as strategic action fields. A field is an order that agents orient themselves towards when acting in it (Fligstein and McAdam Citation2012). I show how market developments correspond to Fligstein and McAdam’s (Citation2012) three market stages, which are (i) field formation; (ii) stable fields and (iii) rupture, crisis or the resettlement of fields. Each stage represents a qualitative shift from what came before and, crucially, does not arise from a single event. Stages are social processes that emerge from multiple and changing pressures, trends, events, norms and practices, thus making clear-cut periodisation difficult. Who is vying for control in the field? How is power structured? Which actions as seen as (un)acceptable? This perspective helps us see that ‘markets’ are not simply ‘markets’: structure, consensus and degrees of stability change over time.

Finally, I discuss the implications and opportunities for university leaders to develop more sustainable market structures for the preparation of international students wishing to pursue degree studies in the United Kingdom.

The field formation stage: ‘mom-and-pop’ goes corporate

Private pathway programmes seem to have first emerged in Australia, and the first Australian private embedded college was UniSearch, which was a private language provider who signed an articulation agreement with the South Wales Institute of Technology in 1984 (Gillett Citation2011). Whilst corporations were not operating pathway programmes in England during the 1990s, policy-driven changes in the higher education funding landscape and the imagined purpose of higher education laid the groundwork for a similar set of movements in England. In the words of one pathway executive, ‘there was a recognition that where Australia was leading the way, the UK was likely to follow’ (Executive, SE26). In the following I show how the five main players established their incumbency in England during the early 2000s.

The rapid growth of corporate embedded colleges in England was at least a decade behind Australia. The early movers were Navitas, which given its initial public offering had the capital to invest heavily in its international growth strategy, and Kaplan, a leading education conglomerate headquartered in the United States and owned by the wealthy Graham family.

By 2004, Navitas had entered into agreements with the University of Hertfordshire and Brunel University London. That year Kaplan established Nottingham Trent International College in partnership with Nottingham Trent University. There was a limited number of universities, and in the field formation stage, corporate pathways prioritised signing up new partners quickly.

Andrew Colin opened INTO University Partnerships and signed up the University of East Anglia and the University of Exeter as partners in 2006. By 2013, the New York-based venture capitalist fund Leeds Equity Partner bought a £66 million stake in the firm (Harrington Citation2018).

Study Group signed up with the University of Sussex in 2006, and by September, CHAMP Private Equity, together with Petersen Investments, took control of the company (AVCAL Citation2011).

Cambridge Education Group (CEG) followed in 2007 by partnering with the University of Central Lancashire and London South Bank University. By 2007, the private equity company Palamon had bought a majority share in CEG. Palamon brought in an experienced executive team, who immediately started diversifying into the pathway market with CEG.

By early 2007, market expansions intensified as the five companies were competing for market position by signing up university partners. In many cases, the added overheads associated with an additional university partnership were limited and the demand for pathway programmes from international students (particularly students hailing from Asia) was strong. This led to an intensive focus on growth, with more than 50 colleges opening in England by 2020 (Hansen Citation2022). This rapid expansion was, according to interviewees, the result of the strategies pursued by corporate leaders’ intent on building a ‘growth story’ to drive up valuations. Competition in this market was therefore conditioned by private investors, their growth strategies and capital. A respondent familiar with a private equity buyout explained the resources they brought to the table:

What the firm really needed was a huge injection of two things, money and rigor, and the money came straight away. The marketing sales budget overnight went from 1 million pounds per annum to 3.1 million pounds, and that's a huge difference in firepower … They brought incredibly sharp focus to our processes, return on investment, disciplines that we were aware of, but were perhaps less rigorous about prosecuting … they were just far more focused on ensuring that every pound spent had an outcome … It was all about growth. (C-suite, number removed to protect anonymity)

While investors looking for high economic growth provided the capital and know-how needed for quick market expansion, respondents also highlighted the narrative and cultural resources that these players mobilised (Williamson and Komljenovic Citation2023). As Beckert reminds us, the effectiveness of a narrative does not rely ‘only [on] what a narrative tells [us] but also how well a narrative is constructed’ (Beckert Citation2021, 13). The charisma, authority and credibility of the people promulgating such narratives may equally have affected how effective they were in convincing others. One university staff member who was working at a Northern university during the field formation stage, for example, tellingly describes their encounter with representatives (‘suits’) from a new embedded college after their university leadership had signed the deal:

I remember that first meeting. We in the International Office in the university suddenly had a meeting with about 12 people in sharp suits from London and the culture clash was extreme. You could feel the difference in the room. My view was, wow these guys really know what they are talking about and what can this do to us in terms of the way in which we are doing our recruitment? But that was not a view that was universally shared.

When you talk about the culture clash and the men in suits, do you remember anything that sticks out, or can you describe that a little bit?

… The thing that sticks most in my mind is the dress. And how these people sat differently, looked differently, spoke differently, and we felt parochial. We felt like a bunch of country bumpkins against some big suits …

(University staff, number not included to safeguard anonymity)

Resistance would manifest itself in the English Language Centres’ just emphatically saying that the pathway company could not teach English to international students. If a partnership was negotiated to the point where the university’s Language Centre had some kind of oversight, well then those academic meetings could be quite difficult. (Person working in corporate pathway, SE03)

The University and College Union (UCU) also resisted the emergence of corporate pathways in general and INTO’s business model in particular (UCU Citation2008, Citation2012, Citation2014). Another person working in a different embedded college recalled how academics would complain to them: ‘Oh, that awful embedded college! What are these students they are sending us?’ (SE10). The respondent did not agree with this critique and would go onto explain that:

… often, what is underlying that [negative sentiment] is a disgruntlement with having to face a lot of East Asian students in the classroom or in a lecture theatre. It is not actually so much the pathway provider. It is the broader context that the university wants more international students, and they are absorbing that. (Person working in corporate pathway, SE10)

Despite the scepticism, it is noticeable that the pathway providers managed to grow their relationships with universities so rapidly. During those years, Kaplan, Navitas, Study Group, Cambridge Education Group, and INTO were ‘the key actors who vied for control of the emerging field’ (Fligstein and McAdam Citation2012, 165). Once the dust settled, they established their position and incumbency.

Stable field: the corporate order settles

The pace of change in partnerships agreements stabilised and external quality procedures where well instituted (QAA Citation2012, Citation2015), leading to market stability. Competition shifted from new university partnerships to existing market shares, exemplified by the ownership change of the University of Sheffield International College from Kaplan to Study Group (Study Group Citation2014). While starting to compete on commission fees paid to recruiting agents, the industry still worked together to stabilise and increase the market’s overall size, for example by jointly starting the policy lobbying group Destination for Education (Smith Citation2017).

During this period, two counterposing dynamic emerged. First, the pathway firms’ ability to generate revenue for university partners and legitimacy in the sector increased. One executive described the gradual change as such:

In 2006, ‘07, ‘08, ‘09, ‘10, the pathway providers were, if you like, the unwelcome tenants in the stately home of the university. We had to be suffered because we did something for them. Now, the relationship has totally moved. It’s almost as if they roll out the red carpet for the pathway providers. (C-suite, SE15)

As a result, pathway firms’ market power over partner universities increased. One university staff member described the shift as follows:

The UK [market] is now mature. The balance of power between the private sector providers and the universities has changed significantly. In [the mid-2000s] x University shoved them at the edge of the campus and they were ‘the people who came and did our bidding.’ Whereas now, if I was to want to go and speak to a major private provider about becoming a partner of our university, that discussion would not have the same balance then that it would have done 10 or 12 years ago. (University staff, SE18)

Second, university leaders’ knowledge about the sector deepened, leading to more effective engagement with the sector, laying a foundation for them to claw back some control when deciding on partnership types, governing partnerships, and negotiating contracts.

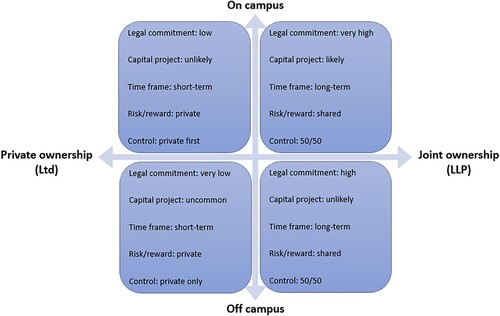

Increased knowledge about the market, for example, allowed university leaders to divide the English pathway market into two types: recruitment-only agreements and partnerships that also include more extensive relationships to a pathway college. In this article, I focus on the latter. Based on my interview data, I classify such partnerships by the ownership form of the college in question (Ltd or LLP status) and by the location of the college (on-campus or off-campus; ).

At the micro level, such categorisation exemplifies what Aspers calls contraction (Aspers Citation2011), i.e. actors recognising what their identity is in the market, what they want to get out of the market and who they should work with to achieve those goals. This contraction was characterised by an increased popularity of limited companies (Ltds) relative to the Limited Liability Partnerships (LLP).

The popularity of Ltds can be ascribed to its members’ limited liability. Debts are ascribed to the company and not its shareholders. This means that shareholders can only lose the value of their share certificates should the company be forced to liquidate. In the English market, if an embedded college is a limited liability company, it normally means the corporate parent, and the pathway firm takes on most of the financial and legal risk. They will also be the main beneficiary of any profit directly generated from the tuition fees paid for the courses delivered by the embedded college. The commercial relationship between the university and the Ltd is set out in a partnership agreement.

The most common type of embedded college is on-campus and privately owned. From the perspective of the university, legal commitment is low and enshrined within a partnership agreement that typically lasts between 5 and 10 years. Historically, capital projects are less common as a part of this model.

Privately-owned colleges that are located off the university campus are normally the least directly associated with a specific university. Given its ownership structure and location, for the university the risk associated with such articulation agreements is relatively manageable both financially and reputationally because the operations are fairly dis-embedded from a branding and commercial point of view.

A Limited Liability Partnership (LLP) is a less common business structure than limited firms. LLPs require at least two members with ownership shares, making universities partial owners. Like limited companies, LLPs have a legal personality, which shields partners from debts beyond their investment. LLPs file joint accounts which makes their financial performance more visible to competitors as and within the partner university, which can raise concerns in cases where the embedded college is not performing financially. LLPS are in particular associated to INTO.

The consensus of the market actors I interviewed was that while the LLP model had lured in some universities in the field formation stage, and while it had provided an avenue for universities to engage in capital projects, it was also the model that had experienced the most backlash among universities. LLPs are particularly associated with Andrew Colin, INTO and capital development. The risk associated with this model is related to future expendables and the reputational risk associated with limited ability to hide the current costs. Such risks became clearer once the business model played itself out over several years:

At the time you are signing up for these things, there is euphoria around because they are going to deliver against this business plan, which is showing hundreds of students coming in. International student is very buoyant, you sign up for a 35-year deal. So, everything is rosy. If you then just take a step back and think ‘so what am I exposing the university to?’ … because in year seven, eight, ten, fifteen whatever, it can all go pear-shaped, and you are left then with the legacy building. (Pro-Vice-Chancellor, SE14)

The future expendables are repayment towards the legacy building financed by the pathway provider, as well as the running cost of training and recruiting pathway students. For underperforming LLP arrangements, this can lead to a fraught situation for the partner university, because they partly rely on the corporate partner to reduce the exposure. First, it is difficult for one member of an LLP to unilaterally liquidate the LLP and covenants with the other members must still be met. Second, asymmetry in business and cost structures between the corporate and public owner can also lead to misalignment in short-term business interest when a college is underperforming. This is because the centralised overheads will not always decrease in cases where the individual college is not performing. While the company would prefer that all its embedded colleges were very profitable, corporate owners may in some instances have an incentive to keep underperforming LLPs alive because university payments go towards the larger recruitment overheads, even though that may mean some negative business for both partners. Such an outcome would not be in the interest of the university stuck with an underperforming college, as they end up subsidising recruitment infrastructure that delivers for competing universities. Third, universities’ financial reporting requirements increase when they become joint owners, which can limit university leadership’s ability to navigate governance pressures internally:

We went through a period of time when my colleagues here in the Council were very agitated, and we were reviewing whether we wanted to continue with the joint venture […] it is a legal requirement for us to report the joint venture financial statement in our accounts, which causes great concern for my colleagues in finance …

When people read the university’s financial accounts, do they understand the relationship between having a joint venture and downstream income?

No … You’d need to have a narrative attached to the accounts to explain that relationship.

So that’s not necessarily a narrative I have seen in the annual reports …

Generally, I think it’s obscured because it’s reported purely financially as the joint venture to stand alone. We are required by our governance to report and approve all joint ventures agreed by our Council and that's the kind of element Council gets nervous [about] when they see a joint venture running at a loss. But the narrative isn’t as clear in the account as it should be […] and the fact that the joint venture … if it breaks even … it’s fine for us. We’re not looking for a profit from there, although we might get some.

(Pro-Vice-Chancellor, SE19)

Overall, for the university leaders I spoke to, their ability to make an informed decision about which company to choose had gone beyond scrutinising business plans and promises (Beckert Citation2021), to also making judgments based on past experience. For example, one university leader whom I interviewed was in the process of ending their relationship with their pathway provider, citing poor performance and problematic legal structures as the deciding factors. Other university respondents also found that pathway providers had promised to deliver a diverse student population, but in fact mostly recruited students from a limited set of nationalities. As such, it is fair to say that university leaders became more sceptical and knowledgeable about the different types of embedded colleges and their specific advantages and drawbacks, as well as the sector-specific limitations of the industry. It became clearer that pathway firms did not revolutionise the recruitment of international students, but mediated the relationship between student, agent and university in a new way. While pathway programmes do change how recruitment is organised, they do not fundamentally break existing recruitment dynamics.

Rupture and resettlement: growth slows down

This stage was characterised by harder market conditions because the market characteristics that had made the sector so attractive in the first place, now made it vulnerable. As revenue growth rates slowed down, private equity owners further encouraged their companies to diversify into new but related revenue stream, such as education technology.

Respondents identified a number of dynamics seen to reinforce conditions for the third market stage, rupture and resettlement, which the Covid-19 pandemic accelerated. These were all grounded in market characteristics that made it attractive in the first place, as compared to the adjacent market for language courses for international students. For example, the duration of pathway programmes were longer than for language courses thereby boosting per-student profit margins; acquisition cost was lower than for language courses because the commission paid to the agent was more aligned with the commission paid to universities, which historically had been lower; partnerships with universities gave corporate players credibility and brand recognition, and venture capital firms provided working capital needed for expansion because they saw a high-margin sector in growth.

These initial characteristics influenced the specific path along which the market developed: for example, the high tuition fee universities could command from international students raised the opportunity cost associated with each international student not recruited. This puts upward pressure on student acquisition costs and downward pressure on entry tariffs (i.e. the grade point average needed to enter the programme) because pathway providers essentially worked as agent aggregators (Nikula et al. Citation2022) for universities. As the pressure built, recruitment cost rose. From interviews we know that the typical commission paid by pathway firms is about 10–30 percent of first-year tuition fees. On top of that still comes the cost associated with running large marketing operations and competitive admission processes that can turn around an application, often within 24–48 h. High price points make corporate pathway providers vulnerable to substitute products. One private equity investor explained:

The risks for limited company pathways are: (1) universities opting for joint ventures instead [of limited companies]; (2) western universities setting up campuses overseas allowing students to access a similar brand at lower cost; (3) online education; and (4) local international schools that could fill the gap between K-12 and university. These risks are augmented by pathways’ churn rate (typically a new cohort every year) which increases volatility and therefore risk. Pathway firms can diversify into these products, but the markets of course overlap. Scale is important here for the different demand segments to be viable. (Private equity, SE24)

In other words, this investor is thinking about substitute products and services that deliver at lower price points and earlier student capture. These risks are augmented by the relative short duration students stay with the pathway provider as a paying customer (i.e. the churn rate). One substitution threat that the investor left out was that of universities themselves: A Pro-Vice-Chancellor speculated that universities under financial pressure to recruit more students in a market where other institutions lowered their entry tariffs could feel pressure to do the same. Eventually, they argued, tariffs could drop so far down that universities would start competing directly with the pathway programmes:

I think if the universities are to survive and drop their tariffs [i.e. entry requirements] very low because they require international students, and they are prepared to drop right down to the bottom, they will introduce foundation students in the first year, and it will squeeze the foundation market significantly. (Pro-Vice-Chancellor, SE19)

Most of the corporate leaders I talked to referenced tracking their students once they entered university and claimed they could prove that their students on average performed better than direct entry recruitments. This was also useful data when signing up new universities. The executive quoted below described how difficult it could be to pitch a new partnership to a university and why it was key to demonstrate that their students performed well:

: How do you demonstrate that [a partnership will go well] before the partnership starts?

: We just use benchmarks from previous [partnerships]. For the first partnerships, I bluffed to be honest. I bluffed it.

(Pathway executive, number not included to safeguard anonymity)

While it is a common assumption in management strategy that markets go through cycles and that relative growth in mature markets goes down, mid-market private equity owners expected and needed ‘double-digit growth,’ which connotes a year-on-year revenue growth rate of 10 or more percent. The ways in which they sought to grow their businesses thus brought with them their own internal logics and rhythms because they bought companies to resell them within a 5- to 7-year time frame.

When PE acquisitions are around the same time, it means that the businesses are often on the same cycle. They have three to five years to do something. In case of education assets, it’s often longer, seven years or so.

Why is that?

Because it takes longer to make change. If you are in a normal business, you put in a new revenue or product, and you sell it the next month. If you put in a new product in an academic business you have to wait until next September, for the academic year. So if you lose that window, you must wait for another year.

(C-suite, SE22)

While times of crisis can bring new challengers into the market, it is also possible to use an incumbent as a platform to consolidate, innovate or diversify. This was indeed something the private equity players considered. I found that the positionality of the private equity investors was an outlier among my respondents because, even though they had a highly specialised professional identity, they were also the group least tied to the pathway market itself, understood as an educational activity. Or put differently, they were the group most indifferent to any specific industry. They represented capital, and in a sense were less constrained in thinking about a specific university, a specific partnership or a specific corporation. They knew their investments, but they thought about their investments as one among many:

We have an extremely capable leadership team which is running an excellent education operation and know-how to drive education quality. That is not what we do, I am not an education person. What we can do is create a more valuable business by thinking more holistically than the executives do about the value proposition, as well as adjacent markets …

This included thinking beyond the dominant value propositions of the field formation and stable field stage:

… We have been pushing them to think of the value proposition beyond recruitment and teaching to everything that relates to student engagement, to helping universities with digital recruitment and welfare. So how do we follow the students through their time at university and help them—potentially with careers as well? (Private Equity investor, SE29)

There seemed to be some difference in how companies thought about diversifying into new products and service markets. Most focused on expanding online degrees or teaching delivery. Cambridge Education Group launched CEG Digital in 2016 and Study Group acquired Insendi in 2019, an educational technology spin-off of Imperial College London. Overall, perhaps with the exception of INTO’s LLP approach, this requires more upfront investment by the private provider than in the pathway sector because it is the norm that the pathway company deliver all the upfront investment into education technologies. These investments are then returned on a profit-share model: Williamson has estimated that online programme management (OPM) such as 2UOS allows companies to retain 50–60 percent of the profit (Citation2020).

Even though the university delivers the teaching in some of these new arrangements, the infrastructure and associated learning data produced is the property of the pathway company. A burgeoning literature is investigating these more general market trends (Fourcade and Healy Citation2017; Hansen and Komljenovic Citation2023; Williamson and Hogan Citation2020). From a pathway executive’s perspective, or that of a private equity owner, digital delivery is potentially lucrative because the market is growing fast. It thus makes strategic sense to reallocate cash from the pathway business and use it to invest in the digital business, which is leading to the emergence of a new industry cycle around digital delivery.

As such, the external shock of Covid-19 seemed to deepen the internal contradictions and structures already built up in the market. This speaks to the ‘common mistake to assume that fast-growing markets are always attractive’ (Porter Citation2008, 86): factors that initially made the market for embedded colleges lucrative for language providers also resulted in systemic weaknesses in the sector over time.

Conclusion

This paper identified three market stages for corporate embedded colleges in England. Throughout all three stages, the pathway providers’ relative importance to university finances intensified, and their position as a legitimate actor in the market solidified. Increased legitimacy and economic importance strengthened private actors’ power over universities. At the same time, as the market matured, university leaders’ knowledge about the pathway and recruitment markets, and the competences with which they could engage in them, equally improved. The competition of corporate actors over students and university partnerships intensified. This new competitive landscape and competences allowed universities to claw back some degree of power and control during stages 2 and 3.

The analytical purpose of narrating these three stages was to convey the respondents’ imaginaries about the type of uncertainties and coordination problems that were seen as relevant in various periods, and how different organisational configurations were seen to respond to these challenges (Beckert Citation2009). This helped me offer an explanation as to how the sector was instituted, the commercial dynamics that they brought with them, and the cognitive framings that may have underpinned these interrelated processes (Aspers Citation2011; Beckert Citation2013; Polanyi Citation2018). As such, building on the accounts from my interviews and document analysis, this is a narrative of stepwise change in the fields that make up the market (Fligstein and McAdam Citation2012), i.e. the expectations that market actors carry, the ways in which the industry was embedded into the higher education sector, and the internal contradictions and tensions that mounted as the market matured (Harvey Citation2014). Prior to starting my fieldwork I made the methodological choice of focusing my analysis on the English market. Throughout the analysis I foreground influences and connections from the Australian markets, whilst backgrounding those from the North American and European markets. I made this narrative choice to mirror my respondents’ foci during my interviews. The UK–US and UK–European market dynamics remain important areas for future research, but they did not loom large in my respondents’ accounts of their industry.

In the field formation stage, I unpacked the instituting of the market and its rapid growth. The section demonstrates the important role that imagined futures played early on in the proliferation of the private market; the universities’ imagined down-stream revenue was particularly key. Imagined downstream revenue is the profit that universities project they will earn once partnerships with pathway providers result in the admission of more international students. In the stable field stage, I showed how these commercial relationships stabilised into specific legal structures, and how their apparent variegated effects on partners had become clear to market actors. Commercial growth and pricing dynamics also changed as a result of the increased competition over international students, making the overall market conditions more challenging. Finally, in the rupture stage, I discussed how the Covid-19 pandemic further exposed mounting commercial tensions and emerging trends. This discussion demonstrates the contingent, social and emergent nature of market-making and reproduction. For example, universities did manage to materialise their future imaginaries of generating profit through increased recruitment of international students. However, by willing that future into existence, they also put in motion new commercial dynamics that made it more expensive and difficult to recruit these students, thus partially undermining the very future they were hoping to create.

This study highlights the importance of going beyond looking at how a market is instituted (Polanyi Citation2018) and how cognitive frames are mobilised in the market making process (Beckert Citation2016), to also tracking how the internal logics of the market change over time. Such changes affect power relations, norms and cost structures: the high margins associated with educating international students, and the initial unwillingness on the part of universities to partner with private corporations and recruiting agents, infused a certain starting position for the market which influenced subsequently emerging logics. While it might have been initially unclear to university leaders, universities indirectly changed their relationship to third-party agents by letting pathway providers compete on acquisition cost on their behalf. When universities turn towards market principles to solve particular coordination problems, the internal logic of that principle may, over time, proliferate and become a generalisable feature of the entire sector (Sayer Citation1995; Slater and Tonkiss Citation2001). Outsourcing market participation to corporate firms does not, in the long run, insulate higher education institutions from the market logic that they promote.

Acknowledgments

I am in debt to interview participants, colleagues and friends who have generously offered their time and expertise to this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agosti, Cintia Inés, and Eva Bernat. 2018. University Pathway Programs: Local Responses within a Growing Global Trend. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-72505-5.

- Aspers, Patrik. 2009. “How Are Markets Made?” Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Cologne. http://www.mpifg.de/pu/workpap/wp09-2.pdf.

- Aspers, Patrik. 2011. Markets. Economy and Society Series. Cambridge: Polity.

- AVCAL. 2011. “Media release.” http://www.brandoncapital.com.au/uploads/default/files/avcal-awards-2011-press-release.pdf.

- Beckert, Jens. 2009. “The Social Order of Markets.” Theory and Society 38 (3): 245–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-008-9082-0.

- Beckert, Jens. 2013. “Capitalism as a System of Expectations.” Politics and Society 41 (3): 323–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329213493750.

- Beckert, Jens. 2016. Imagined Futures: Fictional Expectations and Capitalist Dynamics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Beckert, Jens. 2021. “The Firm as an Engine of Imagination: Organizational Prospection and the Making of Economic Futures.” Organization Theory 2 (2): 263178772110057. https://doi.org/10.1177/26317877211005773.

- Bolton, Paul. 2021. “Higher Education Funding in England.” Breifing Paper, Number 7973. London: House of Commons Library. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-7973/.

- Cambridge English & StudyPortals. 2015. New Routes to Higher Education: The Global Rise of Foundation Programmes.”.

- Cambridge English & StudyPortals. 2016. “Routes to Higher Education: The Global Shape of Pathway Programmes.” http://www.cambridgeenglish.org/images/pathways-report-2016.pdf.

- Choudaha, Rahul. 2017. “Landscape of Third-Party Pathway Partnerships in the U.S.” NAFSA: Association of International Educators.

- Collini, Stefan. 2011. “From Robbins to McKinsey.” London Review of Books, August 25, 2011. https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v33/n16/stefan-collini/from-robbins-to-mckinsey.

- Cunnington, Mark John. 2019. “Aligning Expectations to Experiences: A Qualitative Study of International Students Enrolled on Privately Provided UK University Pathway Programmes.” Edd, University of Liverpool. http://livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/3051361.

- Dooey, Patricia. 2010. “Students’ Perspectives of an EAP Pathway Program.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 9 (3): 184–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2010.02.013.

- Dunworth, Katie, Maria Fiocco, and Denise Mulligan. 2012. “From Pathway to Destination: A Preliminary Investigation into the Transition of Pathway Students to Undergraduate Study.” The ACPET Journal for Private Higher Education; East Melbourne 1 (2): 31–39.

- Dyson, Bronwen Patricia. 2014. “Are Onshore Pathway Students Prepared for Effective University Participation? A Case Study of an International Postgraduate Cohort.” Journal of Academic Language and Learning 8 (2): A28–A42.

- Fiocco, Maria. 2005. “Glonacal Contexts: Internationalisation Policy in the Australian Higher Education Sector and the Development of Pathway Programs.” Unpublished doctoral diss., Murdoch University, Perth, Western Australia.

- Fligstein, Neil, and Doug McAdam. 2012. A Theory of Fields. London: Oxford University Press.

- Floyd, Carol. 2015. “Closing the Gap: International Student Pathways, Academic Performance and Academic Acculturation.” Journal of Academic Language and Learning 9 (2): 1–19.

- Fourcade, Marion, and Kieran Healy. 2017. “Seeing Like a Market.” Socio-Economic Review 15 (1): 9–29. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mww033.

- Gillett, Rodney Allan. 2011. “Steering in the Same Direction?: An Examination of the Mission and Structure of the Governance of Providers of Pathway Programs.” Australia: Edith Cowan University.

- Hansen, Morten. 2022. Crafting Real Education Markets: The Case of Corporate Embedded Colleges in England. Oxford: University of Cambridge.

- Hansen, Morten, and Janja Komljenovic. 2023. “Automating Learning Situations in EdTech: Techno-Commercial Logic of Assetisation.” Postdigital Science and Education 5 (1): 100–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-022-00359-4.

- Harrington, Ben. 2018. “Education Tycoon Andrew Colin Lines up £300 m Payday from Sale of His Company INTO University Partnerships.” Sundaytimes.Co.Uk, May 6, 2018, sec. Business. http://global.factiva.com/redir/default.aspx?P=sa&an=SUNDTI0020180505ee560007q&cat=a&ep=ASE.

- Harvey, William S. 2010. “Methodological Approaches for Interviewing Elites.” Geography Compass 4 (3): 193–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2009.00313.x.

- Harvey, David. 2014. Seventeen Contradictions and the End of Capitalism. London: Profile Books.

- House of Lords. 2023. “Chapter 3: Financial Sustainability.” In Must Do Better: The Office for Students and the Looming Crisis Facing Higher Education. https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/41379/documents/203593/default/.

- Komljenovic, Janja. 2016. Making Higher Education Markets. Bristol: University of Bristol.

- McCartney, Dale M., and Amy Scott Metcalfe. 2018. “Corporatization of Higher Education through Internationalization: The Emergence of Pathway Colleges in Canada.” Tertiary Education and Management 24: 206–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2018.1439997.

- Nikula, Pii-Tuulia, Iona Yuelu Huang, Vincenzo Raimo, and Eddie West. 2022. Student Recruitment Agents in International Higher Education: A Multi-Stakeholder Perspective on Challenges and Best Practices. London: Routledge.

- OECD. 1996. The Knowledge-Based Economy. Paris: OECD.

- Olive, Vicky. 2017. How Much Is too Much? Cross-Subsidies from Teaching to Research in British Universities. London: HEPI. http://www.hepi.ac.uk/2017/11/09/much-much-cross-subsidies-teaching-research-british-universities/.

- Polanyi, Karl. 2018. “The Economy as Instituted Process.” In The Sociology of Economic Life, edited by Mark S. Granovetter and Richard Swedberg, 3rd ed. Boulder: Routledge.

- Porter, Michael. 2008. “The Five Competitive Forces That Shape Strategy.” Harvard Business Review 86 (1): 78–93.

- QAA. 2012. Embedded College Review for Educational Oversight: Handbook, October 2012. Gloucester: Author.

- QAA. 2015. Higher Education Review (Embedded Colleges) A Handbook for Embedded Colleges Undergoing Review in 2016. http://www.qaa.ac.uk/en/Publications/Documents/HER-EC-handbook-15.pdf.

- Robertson, Susan L. 2006. “Globalisation, GATS and Trading in Education Services.” In Supranational Regimes and National Education Policies: Encountering Challenge, edited by J. Kallo and R. Rinne, 139–164. Helsinki: Finnish Education Research Association.

- Sayer, Andrew. 1995. Radical Political Economy: A Critique. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Scott, Peter. 1995. The Meanings of Mass Higher Education. Buckingham: Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

- Slater, Don, and Fran Tonkiss. 2001. Market Society: Markets and Modern Social Theory. Cambridge: Polity.

- Smith, Becky. 2017. “UK: Pathway Providers Unite in New Migration Policy Lobby.” 2017. https://thepienews.com/news/uk-pathway-providers-unite-in-new-migration-policy-lobby/.

- Study Group. 2014. “The University of Sheffield International College Is Accepting Applications.” 2014. https://corporate.studygroup.com/news-and-events/news-archive/the-university-of-sheffield-international-college-is-accepting-applications.

- Tamtik, Merli. 2022. “Selling out the Public University? Administrative Sensemaking Strategies for Internationalization via Private Pathway Colleges in Canadian Higher Education.” Journal of Studies in International Education, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/10283153221137687.

- Terraschke, Agnes, and Ridwan Wahid. 2011. “The Impact of EAP Study on the Academic Experiences of International Postgraduate Students in Australia.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 10 (3): 173–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2011.05.003.

- UCU. 2008. “INTO – Their Own Words.” 2008. https://www.ucu.org.uk/media/2888/INTO-in-their-own-words-updated-Nov-08/pdf/into_theirownwords_revnov08.pdf.

- UCU. 2012. “INTO: A Risky Business?” A UCU Briefing: https://www.ucu.org.uk/media/3080/INTO-a-risky-business-A-UCU-briefing-for-City-University-senators-Jan-09/pdf/CityINTO_briefing_jan08.pdf.

- UCU. 2014. “Say NO to INTO.” https://www.ucu.org.uk/media/6247/INTO-Why-you-should-be-worried-about-a-joint-venture-between-York-and-INTO-Mar-14/pdf/ucu_yorkinto_mar14.pdf.

- Willetts, David. 2023. “David Willetts: Sunak’s Departmental Changes. Why Hasn’t the New Science Ministry Taken on Universities?” Conservative Home (blog). https://conservativehome.com/2023/02/14/david-willetts-sunaks-departmental-changes-theyre-mostly-for-the-better-but-why-hasnt-the-new-science-department-taken-on-universities/.

- Williamson, Ben. 2020. “Datafication and Automation in Higher Education during and after the Covid-19 Crisis.” Strathclyde UCU (blog). May 7, 2020. https://strathclydeucu.wordpress.com/2020/05/07/datafication-and-automation-in-higher-education-during-and-after-the-covid-19-crisis/.

- Williamson, Ben, and Anna Hogan. 2020. Commercialisation and Privatisation in/of Education in the Context of Covid-19. Education International.

- Williamson, Ben, and Janja Komljenovic. 2023. “Investing in Imagined Digital Futures: The Techno-Financial ‘Futuring’ of Edtech Investors in Higher Education.” Critical Studies in Education 64: 234–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2022.2081587.

- Winkle, Carter A. 2014. University Partnerships with the Corporate Sector: Faculty Experiences with for-Profit Matriculation Pathway Programs. Innovation and Leadership in English Language Teaching, Vol. 7. Leiden: Brill.