ABSTRACT

Role theory and the study of ideology represent two important concepts of Foreign Policy Analysis. While the former sheds light on the positions which a country assumes on the international stage, the latter examines the deep ideational grounds on which foreign policy rests. This article integrates roles and ideologies to define foreign policy positions. An analysis of the Czech foreign policy during the EU migration crisis identifies four ideologies (Atlanticism, Europeanism, Internationalism and Sovereignism) and five roles (Democracy Supporter, Faithful Ally, Regional Collaborator, Reformer, and Prosperity Builder). On this basis, a number of foreign policy positions are defined, among which that of a Europeanist Reformer stands out as it synthesises two patterns of the Czech foreign policy: its striving for international recognition and its striving for national autonomy. The article also argues that during the migration crisis, the striving for autonomy was somewhat stronger than before.

Introduction

Czechia adopted a strict anti-migration position in the EU migration crisis of 2015 (Csanyi Citation2020; Kałan Citation2015) and became a party of the most serious conflict with the EU since the Czech accession (Drulák Citation2022; Tabosa Citation2020). Not only that before the Russian attack on Ukraine in 2022, Czechia did not face an international crisis of a comparable magnitude since the early 1990s, but the crisis deepened a fault line inside the EU between Western states and new members from Central and Eastern Europe. In this respect, the examination of the Czech reaction to the migration crisis reveals what its basic foreign policy ideas are and how they evolve.

This examination focuses on Czech foreign policy positions. The concept of a foreign policy position builds on two important literatures in foreign policy analysis: on role theory (Holsti Citation1970) and on foreign policy ideology (Carlsnaes Citation1986). It uses the complementarity of roles and ideologies to capture the ideas in which the foreign policy practice is embedded. The position reflects both domestic differences over foreign policy ideas which are frequently investigated as ideologies, and how the state wants to act and how others perceive its acting which is associated with roles.

On the basis of previous research, the Czech positions are defined with respect to four ideologies (Atlanticism, Europeanism, Internationalism, and Sovereignism) and five roles (Democracy Supporter, Faithful Ally, Regional Collaborator, Reformer, and Prosperity Builder). The resulting positions, such as Internationalist Democracy Supporter, Europeanist Reformer, Sovereignist Prosperity Builder, are then operationalised to the examination of the Czech political discourse and the European leaders’ discourse from 2013 to 2019. These positions are examined at three levels: sub-national (political parties), national (President and Prime Minister) and international (reactions of neighbouring and the Visegrad Group countries and the EU).

The article starts with a brief outline of the Czech reaction to the migration crisis. It then proceeds with the definition of ideologies and roles. Subsequently, it reviews ideologies and roles which have shaped Czech foreign policy-making since the early 1990s to come up with a conceptual framework of the Czech positions. Following this, these positions are operationalised and applied to the discourses about migration. Finally, two opposing foreign policy strivings are revealed: the striving for an international alliance and recognition (Europeanist Faithful Ally, Europeanist Regional Collaborator, Europeanist Reformer), and that for national autonomy (Sovereignist Prosperity Builder, Europeanist Reformer). The foreign policy position of the Europeanist Reformer turns out to be especially influential because these two tendencies overlap there. Moreover, each of these strivings is recognised by a different international audience: the EU and Germany appreciate the internationalism, while the Visegrad countries recognise the autonomism.

Czech reaction to the migration crisis

In 2015, Europe faced an unprecedented inflow of refugees and migrants mainly from the Middle East, Afghanistan and Africa, the number of asylum-seekers doubled from previous year reaching 1.3 million. To alleviate the pressure on the border countries (mainly Italy and Greece) and final destination countries (mainly Germany and Sweden), the European Commission introduced a migration relocation mechanism in May 2015 by which the countries which were less affected by the migration (such as Czechia) would accept the migrants who originally arrived elsewhere in the EU. At first, the Czech government voluntarily committed to accepting 1,100 migrants from Italy and Greece but it subsequently disagreed with compulsory relocations. Even after having been outvoted in the Council several months later the government kept rejecting any compulsory relocations for the years to come (Csanyi Citation2020; Kałan Citation2015). This resistance was shared by Poland, Hungary and Slovakia cementing their Visegrad co-operation.

The Czech opposition was remarkable given the fact that the coalition government of the ČSSD, the ANO and the Christian Democrats was one the most pro-European governments in Czech history (Drulák Citation2022). This pro-Brussels orientation was not just a matter of rhetoricFootnote1 but it reflected long-term positions of the ČSSD and the Christian Democrats as well as the position on which the ANO campaigned in 2013 and in 2014. Moreover, this orientation also reflected the need to set the government apart from its soft-Eurosceptic predecessor and find an appealing common denominator for an otherwise heterogeneous coalition.

The fact that this pro-EU government started the most serious conflict with the EU since Czechia joined the organisation (Tabosa Citation2020) made the two leading forces of the coalition (the ČSSD and the ANO) reconsider their previous unconditional support for the EU. This was especially difficult for the ČSSD, whose leaders occupied key decision-making positions (Prime Minister, Foreign Minister, Minister of Interior). The political identity of the party has been defined as pro-European since the 1990s; moreover, the pro-European program of its government justified its controversial coalition with the technocratic populist party ANO.

In this respect, the leaders tried to maintain a careful distinction between supporting the EU and rejecting the relocation as ineffective (Drulák Citation2022). However, while the ČSSD leaders tried to depoliticise the issue pointing to the flaws and failures in the relocation policy without resorting to political or ideological arguments, the ANO leader was more outspoken in his criticism of the European Commission. But the strongest criticism of the EU came from the President Zeman. He started his tenure as a self-proclaimed European federalist but later felt let down by what he saw the EU’s failure to control its borders.

Many factors been suggested as possible explanations of these shifts ranging from populism to technocracy (e.g. Drulák Citation2022; Strnad Citation2022; Taggart and Szczerbiak Citation2018; Vachudova Citation2020; Zgut et al. Citation2018). What stood out was an effort of political leaders to square the circle by appeasing the public opinion which was hostile to accepting any migrants without escalating the conflict with the EU which insisted on the migration quotas. Rather than seeking a new explanation this article tries to better understand the ideas in which this dilemma was embedded. The concept of foreign policy position is especially useful in this respect.

Ideologies and roles

The positions are defined as a synthesis of ideologies and roles. Each of these concepts needs to be briefly introduced. To start with, foreign policy ideology is a set of ideas which motivate the actions of a state in its pursuit of the collective interest (Carlsnaes Citation1986, 150–151). The ideas, be they descriptive, causal or normative, imply a desired state of the world and motivate FP actions. They can be explicitly proclaimed or implicitly followed. Moreover, an ideology shapes the FP expectations of both government actors and the public, and provides criteria for assessing the legitimacy of FP actions. This legitimising function works only if the ideology mobilises the dominant values and beliefs shared in the domestic society (O’Connor and Cooper Citation2021). In this respect, it bridges the foreign and domestic dimensions of foreign policy-making.

The debate about ideologies opens a number of theoretical issues. For example, realists consider ideology as a diversion from the national interest, which is conceived in terms of power or money. On the other hand, their opponents consider ideology, together with other ideas, an inevitable part of foreign policy-making with the only question being what ideas enter it (Weldes Citation1996). However, the most important contribution of the study of ideologies is in the empirical results, especially, in the identification of typologies of contending ideologies (e.g. Chittick, Billingsley, and Travis Citation1995; Murray, Cowden, and Russett Citation1999; O’Connor and Cooper Citation2021; Rathbun Citation2008).

The simplest typology can start with the binary distinction between realism and liberalism as it refers to a fundamental clash of ideas that goes beyond the first great debate in IR (for a recent application see O’Connor and Cooper Citation2021). Despite being rather rough, the realism/liberalism distinction can serve as a starting point when classifying ideologies in foreign policy.

The literature on ideology in foreign policy reflects the U.S. experience and its beliefs and attitudes (Chittick, Billingsley, and Travis Citation1995; Murray, Cowden, and Russett Citation1999; O’Connor and Cooper Citation2021; Rathbun Citation2008). Even though the U.S. foreign policy experience is completely different from that of a Central European country, the analytical and conceptual challenges are similar. Most of this literature engages the founding distinction of IR analysis between realism and liberalism and/or of domestic political analysis between the left and the right. Thus, the basic picture of the U.S. ideologies portrays these as either realist or liberal internationalist, associating realism with the political right and liberal internationalism with the political left. In addition to that, the ideology of isolationism cuts across both the realist-liberal divide and the left-right cleavage.

The literature on ideologies in the Central Europe is less rich. Fawn (Citation2004a, 6) reminds us of the significance of Marxism-Leninism in the Soviet bloc countries’ foreign policies during the Cold War. Reviewing the foreign policies of the USSR and its satellites, he also points out that this ideology frequently gave way to the realism of Soviet national interest. No matter whether the Central European countries’ foreign policies were shaped by a Marxism-Leninism or realism, they were always subordinated to Moscow’s commands. In this respect, their dominant ideology was the one of loyalty to the Soviet centre.

While ideologies reveal ideas and a basic orientation for foreign policy conduct, they do not tell us much about what states are doing and how others react to it. It is the concept of the national role that puts the state within the society of other international actors, describing what the state expects from and offers to the others and how the others react (Breuning Citation1995; Elgström and Smith Citation2006; Holsti Citation1970; Wehner and Thies Citation2014). It examines ideas but also capabilities, international activities, geographical locations, and institutional commitments.

The role can be elaborated in three dimensions. First, it is defined with respect to the state’s geographical position, capabilities, socio-economic needs, traditions, public opinion or political leadership (Holsti Citation1970, 245). This role conception can be examined by the discourse about the nation’s role in the world. Second, the role is prescribed by other actors – significant others (Harnisch Citation2011; Harnisch and Beneš Citation2015; Woelfel and Haller Citation1971). The role prescription can be found in others’ expectations and how the state understands these expectations (Aggestam Citation2006; Gaskarth Citation2014; Harnisch, Frank, and Maull Citation2011). Finally, the role is performed in the actual foreign policy conduct (Breuning Citation2011; Holsti Citation1970).

Rarely does a state perform one role only (Cantir and Kaarbo Citation2016). It is more usual that its conduct is associated with a set of roles. Holsti (Citation1970) assumed that the roles are mutually compatible, consistent and stable. These assumptions turn out to be too strong, for states are not necessarily consistent, and static, for their roles do evolve due to domestic or international circumstances (Gaskarth Citation2014; McCourt Citation2021). For example, during crises, foreign policy makers are forced to deviate from established patterns and improvise (Wehner and Thies Citation2014). They may use a different rhetoric, evoke different values and ideas and call for unusual solutions. Under pressure, roles do change, which makes them less compatible and may bring about role conflicts (Aggestam Citation2006; Breuning Citation2011).

The literature offers a number of role conceptions examined with respect to different states. Early works used simple dichotomies such as isolationist vs. expansive (Max Weber quoted in Holsti Citation1970, 249), or active vs. passive (Morgenthau Citation1967). More refined typologies took into account power and motivation, distinguishing between strong and weak and satisfied and dissatisfied (Organski Citation1960), between an expansionist, an active independent and an opportunist (Hermann Citation1987, 134), or between a balancer, a supervisor, a patron and a regional leader (Elgström and Smith Citation2006).

Holsti’s (Citation1970) pioneering work stands out as an excellent point of departure. Not only has his typology been used in a variety of research projects (Aggestam Citation2006; Breuning Citation1995; Wehner and Thies Citation2014) but Holsti also applied it to communist Czechoslovakia, ascribing to it the roles of Liberation Supporter (supporting liberation movements abroad by arms, goods and experts), Regional-Subsystem Collaborator (working within the Warsaw Pact and the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance), Faithful Ally (supporting the Soviet foreign policy) and Protectee (relying on the Soviet Union as an exclusive security provider).

Czech positions

Czech ideologies and roles are identified on the basis of the previous research on Czech foreign policy. While the typology of ideologies includes Atlanticism, Europeanism, Internationalism and Sovereignism, that of roles includes Democracy Supporter, Faithful Ally, Prosperity Builder, Regional Collaborator and Reformer. The synthesis of these roles and ideologies produces about twenty foreign policy positions which present basic categories for further empirical analysis.

Once the Central European countries regained their sovereignty in 1989, two ideologies became dominant: liberalism and nationalism (Fawn Citation2004a, 10–12). The ideological revival of nationalism was inevitable, given that the late communist regimes were eventually challenged regarding the return of the sovereign statehood which had been usurped by Moscow. Even though nationalism and realism are not the same, they overlap to a large extent in foreign policy. They ascribe the main agency to a nation state which follows its national interest while considering others as rivals or enemies.

However, the Czech return to national sovereignty was followed by a return to Europe. In foreign policy, the liberal ideology was consequently incarnated by ‘Europe’ (European Union’s ideology), to which the Central European countries were exposed during and after their EU accession (Fawn Citation2004a, 31–36). Apart from usual liberal tenets such as individual rights, democracy and free market, Europe’s ideology also included a civic concept of the nation and supranational institutions. The liberal turn eventually prevailed and became dominant in the Central European foreign policies in the 1990s. Given its dominant position, liberalism needed to accommodate the diversity of political ideas and cleavages. Thus, the right-left distinction resurfaced under the guise of two liberal ideological streams which took different shapes in different countries (Fawn Citation2004a, 12).

In this respect, Fawn (Citation2004b) distinguishes two foreign policy ideologies in Czechia of the 1990s: the left-leaning societal liberalism of Václav Havel that aimed at universalist protection and promotion of democracy and human rights, and the right-leaning economic liberalism of Václav Klaus that aimed at the promotion of markets and economic freedom abroad. The two ideologies were embraced by major political parties and social organisations. Despite their differences, they overlapped in the promotion of the Czech ‘return to Europe’, and they came from the same liberal internationalist ideology that prevailed in the Western discourse of the 1990s.

The liberal internationalist ideology was linked with the accession to NATO and the EU. On the accomplishment of these accessions, the internationalism gave rise to new powerful ideological offshoots (Drulák Citation2006; Drulák, Kořan, and Růžička Citation2008) – Atlanticism and Europeanism. Atlanticism put emphasis on the adherence to the ‘transatlantic’ values of human rights and democracy and to the political community represented by NATO and led by the USA. Europeanism focused on belonging to the European Union. It argued for further European integration, a close co-operation with Brussels institutions and support to the European normative power in the world. In contrast, Sovereignism emerged as an illiberal alternative.

Apart from the times of transatlantic rifts, Atlanticism and Europeanism are mutually compatible but they differ with respect to which political community is seen as more significant, the Atlantic or the European one (Hoffmann Citation2021). Despite that, a Euro-Atlanticist ideology, considering both as equally significant, has been informing the prevailing playbook of Czech diplomacy.

The concept of Internationalism is used here to refer to an ideology which is less West-centric and more globally oriented than either Europeanism or Atlanticism. It draws attention to global problems and considers the UN as the key institution. In contrast, Sovereignism puts much emphasis on the Czech national interest and its promotion multilaterally (inside NATO, the EU and other international institutions), bilaterally (with partners outside the EU and NATO), and unilaterally (as long as limited capabilities allow such a conduct).

How did the roles evolve after 1989? Given that Holsti (Citation1970) expected the roles to be rather stable as they refer to internalised patterns of behaviour that evolve slowly, it is not surprising that the roles that Czechoslovakia used to perform in the Soviet bloc found analogies in the roles Czechia has been taking within the Euro-Atlantic community. On this basis, it can be argued that the roles of a Democracy Supporter, a Regional Collaborator and a Faithful Ally have been providing a meaningful picture of the Czech roles since the turn of the century.

First, the role of a Democracy Supporter draws on the country’s previous role as a liberation supporter. It refers to the global promotion of human rights and democracy in its alliance with the USA or the EU (Kořan et al. Citation2010). The role is justified by a reference to the previous suppression of human rights by the Czechoslovak communist governments. Even though democracy and human rights are conceived of as universal, the Atlantic or European leadership is considered essential and indispensable. Second, the role of a Regional Collaborator reflects the Czech position in Central Europe and Europe (Kořan et al. Citation2010). As a Regional Collaborator, Czechia tries to maintain or strengthen the Visegrad co-operation and not to jeopardise the unity within the EU. Third, the role of a Faithful Ally characterises the country’s relations with the USA as Czechia has been doing its best to follow the U.S. positions on issues that Washington sees as important (Kořan et al. Citation2010). This role is also relevant for its relations with the EU. Thus, Atlanticists and Europeanists are likely to agree on the need to be a Faithful Ally; however, during transatlantic disputes each side will argue for faithfulness to a different alliance.

In addition, two new roles have emerged: a Prosperity Builder and a Reformer. While within the Soviet bloc Czechoslovakia belonged to the most technologically and economically advanced countries and even surpassed the Soviet hegemon in this regard, Czechia was joining the Euro-Atlantic community as an underdeveloped country in need of development assistance (Kuus Citation2004, 475). Thus the ‘return to Europe’ was also motivated by the building of prosperity, which was especially linked with the Czech expectations of the EU single market and development funds. As for the role of a Reformer, it is informed by a critical attitude towards the key international institutions and calls for their reform.

The five roles of Democracy Supporter, Faithful Ally, Prosperity Builder, Regional Collaborator and Reformer do not represent the only possible set of roles that would account for the Czech foreign policy. However, their complementary perspectives provide a coherent picture of the top Czech foreign policy themes. Now, what foreign policy positions are produced by these roles and ideologies ()?

Table 1. Foreign policy positions.

The four ideologies and five roles produce 17 positions, not 20, as not all the roles and ideologies are compatible with one another. Only the roles of Reformer and Prosperity Builder match all ideologies and only the ideologies of Europeanism and Atlanticism are compatible with all roles. This does not necessarily make these roles and ideologies more empirically relevant than the others but it shows their versatility.

Migration crisis: methods, data and operationalisation

The above positions need to be operationalised to the examination of the Czech reaction to the EU migration crisis of 2015–2016. The foreign policy positions are conceived, performed and prescribed. Each of these processes can be investigated by analyses of the discourses which it produces. However, these discourses are produced by different actors. The conceptions is done by political parties, the performance by top political leaders and the prescription by significant others (neighbours, V4 and the EU). The three data sets are analysed by either a content analysis or an interpretative discourse analysis.

First, to get a deeper insight into how foreign policy positions are conceived by the domestic actors, it is useful to examine the political parties from which the leaders arise and reflect the plurality of ideas. Most Czech parties tended to Europeanism and Atlanticism (ODS,Footnote2 ČSSD,Footnote3 KDU-ČSL,Footnote4 TOP09,Footnote5 STANFootnote6); however, they turned weaker in the 2010s while the new rising parties either did not embrace clear foreign policy ideologies (ANO,Footnote7 ČPPFootnote8) or tended to Sovereignism (ÚPD,Footnote9 SPD,Footnote10 KSČMFootnote11). Two political parties – ODS and ČSSD – dominated the Czech party system for a long time. While the centre-right ODS was strongly Atlanticist and moderately Europeanist, the centre-left ČSSD embraced a strong Europeanism while being moderately Atlanticist. This ideological orientation was followed by the smaller parties which joined the government coalitions led either by ODS or by ČSSD, such as the centrist KDU-ČSL as well as liberal-conservative STAN and TOP 09. The far-left KSČM rejected the foreign policy direction favoured by other relevant political parties.

In the 2010s, voters’ dissatisfaction gave rise to new political parties. They took pride in the non-political backgrounds of their leaders and defined themselves against ‘traditional’ political parties. The most successful newcomer was ANO, which was founded by Andrej Babiš in 2011 and was the government party in the research period. It is classified as a non-ideological, populist (Havlík Citation2019) or business-firm party (Kopeček Citation2016). Another party, the ČPP, was founded to push for copyright reform and focuses on liberal and post-material values. Finally, ÚPD was founded by Tomio Okamura in 2013 and later evolved into SPD. It is classified as xenophobic, far-right and/or nationalist (Kubát and Hartliński Citation2019).

The electoral party programmes are used to identify the parties’ positions. The programmes may not provide us with insights into the actual political conduct, but they are an invaluable source of political imagination, including conceptions of what the country’s foreign policy position should be like (e.g. Gabel and Hix Citation2002; Onderco Citation2019). The programmes are analysed by a content analysis (Hermann Citation2008; Suedfeld Citation1992) which measures the frequency of the occurrences of the foreign policy positions. The coding is done for the positions which were identified above. The basic unit of analysis is a single sentence while the entire paragraph is reflected upon for the context. The absolute numbers of occurrences for each position are then related to each other to get relative frequencies expressing how significantly they are represented in each programme.

Second, the performance refers to the actual foreign policy conduct, which includes both deeds, in this case the Czech rejection of the EU Commission’s proposal, and words such as the discourse of the top political leaders. In Czechia, the president is the head of the state with an important symbolic power but it is the prime minister who is responsible for the conduct of the government (Kořan et al. Citation2010). In the research period, the Prime Minister of ČSSD Bohuslav Sobotka (2014–2017) was succeeded by the ANO leader Andrej Babiš (2017–2021). The President did not change throughout the research period, as Miloš Zeman’s time in office included the whole research period.

Their discourse is analysed by a content analysis, however, the frequencies are counted in a slightly different way. The unit of analysis is a paragraph. The occurrences of the positions attributed to a leader are summarised for each year, and these absolute numbers are then related to each other to get relative frequencies that can be compared across the years or across the persons.

Third, the prescription comes from significant others outside the state; therefore, the discourses of Czechia’s neighbours, Hungary and the EU institutions are analysed. Their discourse was examined by an interpretative discourse analysis (Waitzkin Citation1993). Explicit statements of foreign leaders about the Czech role in the migration crisis are rather rare, and no large corpus could be created which could be analysed by a content analysis. Still, a meticulous search yields more than one hundred statements by high representatives of the EU institutions and national leaders that can be meaningfully linked to the positions others ascribe to Czechia. Characteristics of individual roles and ideologies were sought in all statements, which showed how officials representing significant others understood the Czech positions.

The data for all the corpora were collected for the period of 2013–2019 which includes not only the years when the crisis peaked (2015, 2016) but also the years immediately before and after it. The period also covers two national elections. The corpus of political programmes includes 17 programmes of nine parties in the legislative elections in 2013 and 2017. The corpus of speeches by political leaders refers to the President and the Prime Ministers. President Miloš Zeman’s speeches and interviews come from his webpage (1088 documents, 176 occurrences). An advanced Google search was used to generate the corpora (44 speeches, 251 occurrences) of the Prime Ministers (Sobotka, Babiš). The corpus of the significant others is based on the websites of the governments, EU institutions and web periodicals. The corpus is structured as follows: EU institutions (24 documents), Germany (15), Austria (8), Slovakia (11), Poland (8) and Hungary (9).

How are the above positions operationalised with respect to the statements found in the corpora? For instance, the statement ‘We will push for Czechia to be a full and credible member of NATO’ (ANO Citation2013) points to Atlanticist Faithful Ally. If Czechia wants to ‘promote the cohesion of the Central European area and to gain allies for the promotion of the Czech priorities within the EU and NATO’ (ANO Citation2017), it is associated with Sovereignist Regional Collaborator. The position of Europeanist Prosperity Builder is present in the statement: ‘We support the Czech Republic to move towards the adoption of the euro in a situation where it will be economically and socially beneficial for us’ (ČSSD Citation2017, 28). Another example statement points to Internationalist Democracy Supporter when the TOP 09 party talked in its programme about ‘promoting democracy and human rights in parts of the world where they are violated’ (TOP 09 Citation2013).

The examples of the statements are self-explanatory. However, it is useful to focus on the differences in statements linked to the positions which include the same role but different ideology, and vice versa. These differences demonstrate the analytical added value of positions as they reveal differences within the role or within the ideology which are invisible if the two categories are used separately. For example, the ideology of Europeanism includes the roles of Faithful Ally which does not consider having interests independent of the EU (‘We are part of the European Union and want to be an active and responsible member’, TOP 09 Citation2017, 3), Regional Collaborator which considers the EU to be the best place for the promotion of own interests (We want ‘to strengthen our voice in the EU and to work towards unity in this integration that takes into account our interests’, TOP 09 Citation2013, 24) and Reformer which believes that the EU must change (‘Rejection of all legislation that is in conflict with the national interests of the Czech Republic’, ODS Citation2017). Similarly, the distinction between a Europeanist Reformer and a Sovereignist Reformer (‘The European Union is unreformable and must end’, SPD Citation2017) is that between those who want to change the EU and those who want to leave the EU.

Two patterns of the Czech foreign policy

The results reveal two opposing patterns in the Czech foreign policy: the quest for an international alliance and recognition, and the striving for national autonomy. While the former corresponds to the positions of a Europeanist, Atlanticist or Internationalist Faithful Ally and a Europeanist Regional Collaborator, the latter is associated with the positions of a Sovereignist Reformer and a Sovereignist Prosperity Builder. As the Europeanist Reformer may accommodate either pattern, it turns out to be especially important. The party programmes and the leaders’ discourse show that both patterns can be at the same time embraced by the same party or even the same political figure. They also show that the migration crisis somewhat shifted the positions towards the national autonomy. Moreover, the two patterns also emerge in the expectations and prescriptions of the significant others. While the German and EU leaders encourage or miss the internationalist pattern, the Visegrad leaders appreciate the autonomist tendency.

The foreign policy positions of the political parties () confirm the two patterns. With respect to the roles, most parties tend to the Faithful Ally while the Regional Collaborator, Reformer and Prosperity Builder come in second and the Democracy Supporter role is only marginal. Among the ideologies, Europeanism clearly prevails and Sovereignism is important while Internationalism and Atlanticism are less important. On this basis, the positions of Europeanist, Internationalist and Atlanticist Faithful Ally turn out to be strongly present and so are several positions constituted by the roles of Regional Collaborator, Reformer and Prosperity Builder in pair with the ideologies of Europeanism or Sovereignism.

Table 2. The foreign policy positions in national elections, 2013 (A) and 2017 (B).

The migration crisis brought about three contrasting developments reflecting the two contradictory patterns analysed above. Some parties (ANO, ČSSD, KDU-ČSL) did not react to it in any significant way. However, some parties turned more critical of the EU as a result: ODS significantly strengthened its call for EU reform (with the Europeanist Reformer role turning into its defining position in 2017), SPD increased its calls for leaving the EU (Sovereignist Reformer), and KSČM turned less Internationalist and more Sovereignist. In contrast, two small parties, TOP 09 and the Pirates, reacted to the crisis in favour of the EU by embracing the position of a Europeanist Faithful Ally.

Now, while the electoral programmes give us insight into the plurality of ideas which motivate or justify the foreign policy action, the investigation of the foreign policy performance requires a look into the discourse of the Prime Ministers and the President.

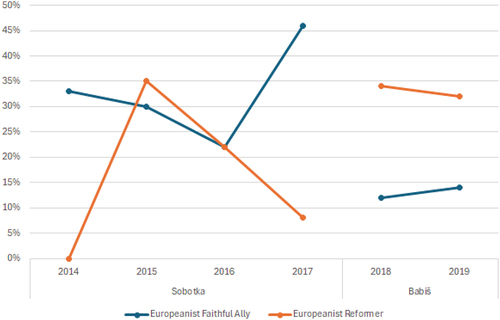

The Prime Ministers are best analysed by their references to the positions of the Europeanist Faithful Ally and the Europeanist Reformer (). Not only that they used these two positions more frequently than other positions but the two positions also represent different perspectives on the EU. While the Europeanist Faithfull Ally hints at an uncritical embrace of the EU, the Europeanist Reformer refers to an attitude which is critical to the EU without however rejecting it. The more frequent the references to the Europeanist Reformer, the less frequent the references to the Europeanist Faithful Ally. Prime Minister Sobotka’s most frequent position was the Europeanist Faithful Ally (30.3%) which reflected a long-term, pro-EU orientation of his party. However, as the crisis evolved his adherence to the Europeanist Faithful Ally declined while that of the Europeanist Reformer grew. At the peak of the crisis in 2015 the Europeanist Reformer became his dominant position (35%), as Sobotka was explaining that ‘[…] we do not consider mandatory quotas to be a good solution. We reject them’ (Sobotka Citation2015). On the other hand, as the crisis subsided in 2016 and 2017, Sobotka was abandoning the Europeanist Reformer and again embracing the Europeanist Faithful Ally.

Figure 1. Europeanist faithful ally vs. Europeanist reformer: prime ministers’ speeches (percentages of occurrences).

This was not the case with his successor. Prime Minister Babiš was consistent in his reference to the Europeanist Reformer irrespective of the evolution of the migration flows. His embrace of the Europeanist Reformer (becoming his most favoured position with 32.6%) points to a shift in the Czech position on the EU which goes beyond the migration crisis that brought it about. Babiš often argued that ‘we need to reform the EU’ (Babiš Citation2018a) and that ‘we want a Europe of strong member states’ (Babiš Citation2019). Occasionally, he used more radical positions such as Europeanist Regional Collaborator (10.1%) or the Sovereignist Reformer (8% in 2018, 3.1% of all statements) claiming, for example, that ‘no one [the EU] can impose who will work and live in our country’ (Babiš Citation2018b). On the other hand, being a pragmatic politician carefully hedging his positions Babiš also frequently evoked the role of a Faithful Ally, which was associated with a number of ideologies: Internationalism (10.9%), Europeanism (13.2%) and Atlanticism (15.5%).

Like Babiš, the President Zeman consistently referred to the Europeanist Reformer as his most frequent position (40% of all statements). However, he evolved from a slight criticism of the lack of the EU capacity to act to a sharp rejection of many features of the EU saying, for example, ‘I would be very happy if the European Commission was punched in the face and was told […] the real European government, is the European Council’ (Zeman Citation2019). Moreover, being increasingly dissatisfied with the EU Zeman tended to embrace Sovereignism. Thus, he evoked the Sovereignist Prosperity Builder (8.5%) to emphasize the national economic interest and Sovereignist Regional Collaborator (10%) to appreciate the Visegrad cooperation: ‘[…] I greatly appreciate the activities of the Visegrad Group. It managed the almost impossible, […] manifestation of the sovereignty is that this country decides for itself who it wants and who it does not want to accept on its territory’ (Zeman Citation2018).

When the significant others reacted to Czechia, they rarely singled it out and tended to speak about the whole CEE region. Two sets of expectations and prescriptions emerged, each corresponding to one of the above patterns. The EU institutions and Germany acted on the basis of the Europeanist ideology, feeling let down because the Czech government was not behaving as a Faithful Ally. For example, the President of the European Commission Juncker (quoted in Eriksson Citation2016) chided the ‘Eastern countries’ for ‘asking for solidarity on economic development, on Russia, but having none of it when it comes to refugees’. German president Gauck (quoted in Rettman Citation2016) expressed his ‘incomprehension’ of the fact that ‘those nations whose citizens, once themselves politically oppressed and who experienced solidarity, in turn, withdr[e]w their solidarity for the oppressed’. However, the German leaders also appreciated the Czech efforts to find a solution to the crisis and achieve good bilateral relations, recognising Czechia as a Europeanist Regional Collaborator.

The Visegrad countries praised the Czech position of a Sovereignist Regional Collaborator and a Europeanist Reformer. For example, the Hungarian Foreign Minister Szijjártó (quoted in Léko Citation2018) spoke highly of the ‘rationally thinking Central Europeans [who] want a strong European Union based on sovereign and strong member states’. The Slovak Prime Minister Fico (quoted in ČT24 Citation2018) pointed out that Czechia and Slovakia ‘essentially stopped the mandatory quotas, which turned out to be pointless, dysfunctional’. As for Austria, it was of two minds following the split in its domestic politics. While President Fischer, President Van der Bellen and Chancellor Faymann shared the German perspective on Czechia and Central Europe, Chancellor Kurz and Vice-Chancellor Strache were close to the Visegrad perspective.

To sum up, the position of a Europeanist Reformer stands out by cutting across different actors and discourses. It dominates the discourses of some actors, e.g. the party ODS, President Zeman, Prime Minister Babiš or the Visegrad partners, and it is present in the positions of most of the actors. This may be linked with the fact that it offers to bridge the two contrasting tendencies of the Czech foreign policy as it refers both to the belonging to the EU and to EU reform no matter what its goals are, and thus it includes the defence of national autonomy. In this connection, the actors may appreciate the Europeanist Reformer position as it allows them to avoid a painful choice or a simultaneous defence of two potentially contradictory positions.

Conclusions

The concept of position is a finer tool of foreign policy analysis than roles or ideologies when used separately. It shows that the very same ideology can be practiced by rather different roles and that the very same role can get very different shades with different ideologies. Thus, investigating the foreign policy positions may reveal the patterns of continuity and change which other tools will struggle to spot – for example, Prime Minister Sobotka’s shift of emphasis from a Europeanist Faithful Ally to a Europeanist Reformer during the migration crisis.

The analysis of positions also helps us better analyse the tension between autonomist and internationalist patterns in Czech foreign policy. While the very identification of the two tendencies can do without any deeper investigation, the examination of the foreign policy positions can point to what the core ideas of each pattern are, namely, the ideology of Sovereignism associated with the roles of Reformer and Prosperity Builder for the autonomist pattern, and the role of Faithful Ally associated with the ideologies of Internationalism, Atlanticism and Europeanism for the internationalist pattern. The position of the Europeanist Reformer then offers a middle-of-the-road alternative.

With respect to the ideologies, it is worth noticing that the migration crisis was not accompanied by any strong Atlanticist positions and brought about a new kind of Sovereignism. The relative weakness of Atlanticism, due to the absence of any U.S. influence in the crisis, is likely to be temporary as the war in Ukraine seems to reveal now.

But the new Sovereignism may be more lasting. The previous crises, the international financial crisis and the ensuing eurozone crisis, already undermined the Europeanist and Atlanticist convictions that national prosperity is best guaranteed by economic ties with the Western countries, and brought about calls for more economic ties with China, Russia or the Gulf countries (Kříž, Chovančík, and Krpec Citation2021, 52–53). But Sovereignism was mostly conceived of as only complementing the Euro-Atlanticist orientation. In contrast, Sovereignism incited by the migration crisis is openly directed against Brussels and the ideology of Europeanism.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. See the Policy Statement of the government (Vláda Citation2014).

2. Občanská demokratická strana – Civic Democratic Party.

3. Česká strana sociálně demokratická – Czech Social Democratic Party.

4. Křesťanská a demokratická unie – Christian and Democratic Union.

5. Tradice, odpovědnost, prosperita – Tradition, Responsibility, Prosperity.

6. Starostové a nezávislí – Mayors and Independents.

7. Akce nespokojených občanů – Action of Dissatisfied Citizens.

8. Česká pirátská strana – Czech Pirate Party.

9. Úsvit přímé demokracie – Dawn of Direct Democracy.

10. Svoboda a přímá demokracie – Freedom and Direct Democracy.

11. Komunistická strana Čech a Moravy – Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia.

References

- Aggestam, L. 2006. “Role Theory and European Foreign Policy: A Framework of Analysis.” In The European Union’s Roles in International Politics. Concepts and Analysis, edited by O. Elgström and M. Smith, 11–29. London: Routledge.

- ANO. 2013. “Volební program ANO 2011 pro volby do Poslanecké sněmovny parlamentu ČR.” Accessed October 18, 2023. https://web.archive.org/web/20150512032609/http://www.anobudelip.cz/cs/o-nas/program/volby-2013/resortni-program.

- ANO. 2017. “Teď nebo nikdy. Ten jediný program, který potřebujete.” Accessed October 18, 2023. https://www.anobudelip.cz/file/edee/2017/09/program-hnuti-ano-pro-volby-do-poslanecke-snemovny.pdf.

- Babiš, A. 2018a, 27 August. Andrej Babiš na poradě velvyslanců: Chtěl bych vám poděkovat za vaši práci, kterou odvádíte pro naši zemi. Vláda ČR. Accessed February 8, 2024, from https://vlada.gov.cz/cz/clenove-vlady/premier/projevy/andrej-babis-na-porade-velvyslancu-chtel-bych-vam-podekovat-za-vasi-praci–kterou-odvadite-pro-nasi-zemi-168137.

- Babiš, A. 2018b, 15 July. Projev předsedy vlády Andreje Babiše v Poslanecké sněmovně před hlasováním o vyslovení důvěry vládě. Vláda ČR. Accessed February 8, 2024, from https://vlada.gov.cz/cz/clenove-vlady/premier/projevy/projev-predsedy-vlady-andreje-babise-v-poslanecke-snemovne-pred-hlasovanim-o-vysloveni-duvery-vlade-167555.

- Babiš, A. 2019, 14 May. Projev předsedy vlády na konferenci Český národní zájem. Vláda ČR. Accessed February 9, 2024, from https://vlada.gov.cz/cz/clenove-vlady/premier/projevy/projev-predsedy-vlady-na-konferenci-cesky-narodni-zajem-173682.

- Breuning, M. 1995. “Words and Deeds: Foreign Assistance Rhetoric and Policy Behavior in the Netherlands, Belgium, and the United Kingdom.” International Studies Quarterly 39 (2): 235–254. https://doi.org/10.2307/2600848.

- Breuning, M. 2011. “Role Research: Genesis and Blind Spots.” In Role Theory in International Relations. Approaches and Analyses, edited by S. Harnisch, C. Frank, and H. W. Maull, 16–35. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Cantir, C., and J. Kaarbo. 2016. Domestic Role Contestation, Foreign and International Relations. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Carlsnaes, W. 1986. Ideology and Foreign Policy: Problems of Comparative Conceptualisations. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Chittick, W. O., K. R. Billingsley, and R. Travis. 1995. “A Three-Dimensional Model of American Foreign Policy Beliefs.” International Studies Quarterly 39 (3): 313–331. https://doi.org/10.2307/2600923.

- Csanyi, P. 2020. “Impact of Immigration on Europe and Its Approach Towards the Migration (European Union States Vs Visegrad Group Countries).” Journal of Comparative Politics 13 (2): 4–23.

- ČSSD. 2017. “Dobrá země pro život.” Accessed October 18, 2023. https://socdem.cz/data/files/program-210x210-seda.pdf.

- ČT24. 2018, 9 October. “Interview ČT24 – rozhovor s Robertem Ficem.” Retrieved 18 November 2022, from https://www.ceskatelevize.cz/porady/10095426857-interview-ct24/218411058041009.

- Drulák, P. 2006. “Qui décide la politique étrangère tchèque ? Les internationalistes, les européanistes, les atlantistes ou les autonomistes ?” La Revue internationale et stratégique N°61 (1): 71–86. https://doi.org/10.3917/ris.061.0071.

- Drulák, P. 2022. “Technocracy That Fails: A Czech Perspective on the EU.” Journal of International Relations and Development 25 (3): 739–760. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41268-022-00260-4.

- Drulák, P., M. Kořan, and J. Růžička. 2008. “Außenpolitik in Ostmitteleuropa Von Universalisten, Atlantikern, Europäern und Souveränisten.” Osteuropa 58 (7): 139–152.

- Elgström, O., and M. Smith. 2006. “Introduction.” In The European Union’s Roles in International Politics. Concepts and Analysis, edited by O. Elgström and M. Smith, 1–10. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Eriksson, A. 2016. “Learn to Love Migrant Quotas, Juncker Tells Eastern EU.” EUobserver. Accessed November 10, 2022, fromhttps://euobserver.com/migration/135257.

- Fawn, R. 2004a. “Ideology and National Identity in Post-Communist Foreign Policies.” In Ideology and National Identity in Post-Communist Foreign Policies, edited by R. Fawn, 1–39. London: Frank Cass.

- Fawn, R. 2004b. “Reconstituting a National Identity: Ideologies in Czech Foreign Policy After the Split.” In Ideology and National Identity in Post-Communist Foreign Policies, edited by R. Fawn, 201–224. London: Frank Cass.

- Gabel, M., and S. Hix. 2002. “Defining the Eu Political Space: An Empirical Study of the European Elections Manifestos, 1979-1999.” Comparative Political Studies 35 (8): 934–964. https://doi.org/10.1177/001041402236309.

- Gaskarth, J. 2014. “Strategizing Britain’s Role in the World.” International Affairs 90 (3): 559–581. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12127.

- Harnisch, S. 2011. “Role Theory: Operationalization of Key Concepts.” In Role Theory in International Relations. Approaches and Analyses, edited by S. Harnisch, C. Frank, and H. W. Maull, 7–15. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Harnisch, S., and V. Beneš. 2015. “Role Theory in Symbolic Interactionism: Czech Republic, Germany, and the EU.” Cooperation and Conflict 50 (1): 146–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010836714525768.

- Harnisch, S., C. Frank, and H. W. Maull, eds. 2011. Role Theory in International Relations. Approaches and Analyses. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Havlík, V. 2019. “Technocratic Populism and Political Illiberalism in Central Europe.” Problems of Post-Communism 66 (6): 369–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2019.1580590.

- Hermann, M. G. 1987. “Leaders’ Foreign Policy Orientations and the Quality of Foreign Policy Decisions.” In Role Theory and Foreign Policy Analysis, edited by S. G. Walker, 123–140. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Hermann, M. G. 2008. “Content Analysis.” In Qualitative Methods in International Relations. A Pluralist Guide, edited by A. Klotz and D. Prakash, 151–167. New York, NY: Palgrave.

- Hoffmann, S. C. 2021. “Beyond Culture and Power: The Role of Party Ideologies in German Foreign and Security Policy.” German Politics 30 (1): 51–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2019.1611783.

- Holsti, K. 1970. “National Role Conceptions in the Study of Foreign Policy.” International Studies Quarterly 14 (3): 233–309. https://doi.org/10.2307/3013584.

- Kałan, D. 2015. “Migration Crisis Unites Visegrad Group.” Bulletin PISM 82 (814): 1–2.

- Kopeček, L. 2016. “’I’m Paying, so I Decide’: Czech ANO As an Extreme Form of a Business-Firm Party.” East European Politics and Societies: And Cultures 30 (4): 725–749. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325416650254.

- Kořan, M. 2010. Czech Foreign Policy in 2007–2009. Analysis. Praha: Ústav mezinárodních vztahů.

- Kříž, Z., M. Chovančík, and O. Krpec. 2021. “Czech Foreign Policy After the Velvet Revolution.” In Foreign Policy Change in European Union Countries Since 1991, edited by J. K. Joly and T. Haesebrouck, 49–71. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kubát, M., and M. Hartliński. 2019. “Party Leaders in the Czech Populist Parties and Movements.” Polish Political Science Review 7 (1): 107–119. https://doi.org/10.2478/ppsr-2019-0007.

- Kuus, M. 2004. “Europe’s Eastern Expansion and the Reinscription of Otherness in East-Central Europe.” Progress in Human Geography 28 (4): 472–489. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132504ph498oa.

- Léko, I. 2018, 8 April. “Evropa musí zůstat evropská, říká maďarský ministr zahraničí Péter Szijjártó.” Lidovky. Accessed November 18, 2022, from https://www.lidovky.cz/svet/evropa-musi-zustat-evropska-prosazujeme-uzsi-spolupraci-vychodu-a-zapadu-rika-peter-szijjarto.A180408_124627_ln_zahranici_.

- McCourt, D. M. 2021. “Domestic Contestation Over Foreign Policy, Role-Based and Otherwise: Three Cautionary Cases.” Politics 41 (2): 173–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263395720945227.

- Morgenthau, H. J. 1967. Politics Among Nations. New York, NY: Alfred Knopf.

- Murray, S. K., J. A. Cowden, and B. M. Russett. 1999. “The Convergence of American Elites’ Domestic Beliefs with Their Foreign Policy Beliefs.” International Interactions 25 (2): 153–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629908434947.

- O’Connor, B., and D. Cooper. 2021. “Ideology and the Foreign Policy of Barack Obama: A Liberal-Realist Approach to International Affairs.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 51 (3): 635–666. https://doi.org/10.1111/psq.12730.

- ODS. 2017. “Silný program pro silné Česko.” Accessed October 18, 2023, from https://www.ods.cz/volby2017/Program-ODS-2017-web.pdf.

- Onderco, M. 2019. “Partisan Views of Russia: Analyzing European Party Electoral Manifestos Since 1991.” Contemporary Security Policy 40 (4): 526–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2019.1661607.

- Organski, A. F. K. 1960. World Politics. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Rathbun, B. C. 2008. “Does One Right Make a Realist? Conservatism, Neoconservatism, and Isolationism in the Foreign Policy Ideology of American Elites.” Political Science Quarterly 123 (2): 271–299. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1538-165X.2008.tb00625.x.

- Rettman, A. 2016. “Austria Imposes Asylum Cap to Shake Up “Europe”.” EUobserver 20 January from. Accessed November 6, 2022, from https://euobserver.com/rule-of-law/131928.

- Sobotka, B. 2015. “Projev předsedy vlády v Poslanecké sněmovně 15. září 2015 k situaci v oblasti migrace.” Vláda ČR. Accessed February 8, 2024, from https://vlada.gov.cz/cz/clenove-vlady/premier/projevy/projev-predsedy-vlady-v-poslanecke-snemovne-15–09--2015-k-situaci-v-oblasti-migrace-134692.

- SPD 2017. “Volební program SPD.” Accessed October 18, 2023, from https://web.archive.org/web/20170823131100/https://www.spd.cz/volebni-program-spd.

- Strnad, V. 2022. “Les Enfants Terribles de l’Europe? The ‘Sovereigntist’ Role of the Visegrád Group in the Context of the Migration Crisis.” Europe-Asia Studies 74 (1): 72–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2021.1976730.

- Suedfeld, P. 1992. “Cognitive Misers and Their Critics.” Political Psychology 13 (3): 435–453. https://doi.org/10.2307/3791607.

- Tabosa, C. 2020. “Constructing Foreign Policy Vis-á-Vis the Migration Crisis: The Czech and Slovak Cases.” Mezinárodní Vztahy 55 (2): 5–23. https://doi.org/10.32422/mv.1687.

- Taggart, P., and A. Szczerbiak. 2018. “Putting Brexit into Perspective: The Effect of the Eurozone and Migration Crises and Brexit on Euroscepticism in European States.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (8): 1194–1214. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1467955.

- TOP 09. 2013. “Víme, kam jdeme.” Accessed October 18, 2023, from https://www.top09.cz/files/soubory/volebni-program-2013-do-poslanecke-snemovny_894.pdf.

- TOP 09. 2017. “Volební program 2017.” Accessed October 18, 2023, from https://www.top09.cz/proc-nas-volit/volebni-program/archiv/volebni-program-2017_1717.pdf.

- Vachudova, M. A. 2020. “Ethnopopulism and democratic backsliding in Central Europe.” East European Politics 36 (3): 318–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2020.1787163.

- Vláda, Č. R. 2014. “Programové prohlášení vlády ČR.” Accessed October 18, 2023, from https://vlada.gov.cz/cz/media-centrum/dulezite-dokumenty/programove-prohlaseni-vlady-cr-115911.

- Waitzkin, H. 1993. “Interpretive Analysis of Spoken Discourse: Dealing with the Limitations of Quantitative and Qualitative Methods.” Southern Communication Journal 58 (2): 128–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/10417949309372895.

- Wehner, L. E., and C. G. Thies. 2014. “Role Theory, Narratives and Interpretation. The Domestic Contestation of Roles.” International Studies Review 16 (3): 411–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/misr.12149.

- Weldes, J. 1996. “Constructing National Interests.” European Journal of International Relations 2 (3): 275–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066196002003001.

- Woelfel, J., and A. O. Haller. 1971. “Significant Others: The Self-Reflexive Act and the Attitude Formation Process.” American Sociological Review 36 (1): 74–87. https://doi.org/10.2307/2093508.

- Zeman, M. 2018, 26 December. “Vánoční poselství prezidenta republiky Miloše Zemana.” Accessed October 30, 2023, from http://www.zemanmilos.cz/cz/clanky/vanocni-poselstvi-prezidenta-republiky-milose-zemana579041.htm.

- Zeman, M. 2019, 20 January. “Rozhovor prezidenta republiky pro internetové vysílání webu Blesk.cz „S prezidentem v Lánech.” Accessed December 5, 2023, from http://www.zemanmilos.cz/cz/clanky/rozhovor-prezidenta-republiky-pro-internetove-vysilani-webu-bleskcz-%E2%80%9Es-prezidentem-v-lanech%E2%80%9D-293399.htm.

- Zgut, E. 2018. Illiberalism in the V4: Pressure Points and Bright Spots. Postdam: Friedrich Naumann Stiftung.