Abstract

Forensic mental health, custodial and community forensic services provide care and treatment to individuals with complex histories and needs including the presence of trauma. With increased attention being paid to delivering trauma informed care, this paper presents a framework for supporting safe and effective service delivery. It details ways in which trauma informed organizational consultation and trauma informed staff supervision and reflective practice should be embedded within criminal justice and forensic mental health service delivery. Together these support reflection, learning, decision making and intentional action, helping to meet an organization’s duty of care to both staff and clients. Trauma informed organizational consultation and trauma informed forensic staff supervision and reflective practice provide ways to anticipate and address possible iatrogenic impacts on staff (e.g. burnout, presenteeism and sickness) and on clients (e.g. dropping out of treatment). Together these can enable services to provide and sustain authentic approaches to delivering safe and effective care.

Trauma in forensic and criminal justice services

Childhood adversity and trauma experiences are overrepresented in criminal justice and forensic mental health settings. Estimates vary by service type and location, however research suggests that at least 7.7% of individuals in such settings would reach the threshold for a diagnosis of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and 16.7% for Complex-PTSD (Facer-Irwin et al., Citation2022) with 32% having experienced four or more Adverse Childhood Experiences—ACES (Stinson et al., Citation2021). ACEs include physical, sexual and emotional abuse, neglect and household violence all experienced before the age of 18 (e.g. Stinson et al., Citation2021). Perhaps less well recognized are the rates of historic and contemporary trauma experience amongst those working within these settings. In addition to facing common adverse life experiences such as divorce, bereavement, and family/personal physical and mental health difficulties, staff may be exposed to in work traumatic events and have their own history of trauma. For example, a study of psychiatric workers found 10% met the screening criteria for PTSD, with exposure to acute (e.g. physical assault) and chronic stressors reported (e.g. witnessing public sexual behavior) (Hilton et al., Citation2020). An older study of those working with sexual offenders found 76% of respondents reported at least one form of childhood maltreatment, with 39% having experienced sexual abuse (Way et al., Citation2007).

Research has shown clear links between PTSD and physical health problems (Ryder et al., Citation2018) and between ACEs and an array of negative health and life outcomes (e.g. Petruccelli et al., Citation2019) including between ACES and violence perpetration and ACES and problematic drug use (Hughes et al., Citation2017). However, staff experiences of aversity and trauma can also impact on the therapeutic relationships and tasks they engage in. A worker history of maltreatment has been associated with disrupted cognitions of trust and intimacy (VanDeusen & Way, Citation2006); a history of neglect, physical or sexual abuse has been linked to disrupted cognitions about self-esteem, and a history of neglect has been linked to disrupted cognitions about intimacy (Way et al., Citation2007).

The notion of trauma is complex with the term being used to describe an event(s), a biopsychosocial response and the experienced impact (Willmot & Jones, Citation2022a). Widely used psychiatric diagnostic systems, require that the precipitating event(s) be identified alongside the symptom experiences reported. However, this has resulted in some potential sources of trauma, especially those disproportionally experienced by the most vulnerable and marginalized in society (e.g. racial and financial trauma), being overlooked and neglected (Gradus & Galea, Citation2022). Alongside this, there has been a growing recognition of the cumulative impact of adversity and traumatic events as well as of experiences of poly-victimisation (Fosse et al., Citation2020; Hamby et al., Citation2021) and inter- and trans- generational trauma (Adams et al., Citation2023; Zeynel & Uzer, Citation2020). Additionally, the high rates of conflict, verbal and physical assault (Kelly et al., Citation2015) and other features such as power imbalances, contribute to the traumagenic experiences common within criminal justice settings (Levenson & Willis, Citation2019). Consequently, some agencies have taken a more inclusive approach, defining trauma as “an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.” (SAMHSA, Citation2014, p. 7). It is this this broader conceptualization that is used through this paper.

Whilst staff may be exposed to the same forms of trauma as the clients they work with (e.g. Saunders et al., Citation2023), staff are expected to set and maintain effective boundaries. Boundary development and review has been described as a cyclical process which can be supported through supervision and reflective practice (Pettman et al., Citation2020). Boundaries form a key part of relational security within forensic mental health settings, with boundary maintenance being a key responsibility of the individual, the team and the service (Allen, Citation2023). However, when boundary problems arise - such as intimate relationships between staff and service users/prisoners - these are generally reported and understood in the media using the “bad apple” metaphor in which ‘weakness’ and ‘fault’ are located within the individual (e.g. BBC News Online, Citation2023). Organizational responses often take a similar stance and locate responsibility for boundary violations within the individual. Where staff anticipate personal blame if something serious should occur, they may ‘safeguard themselves’ by adopting unhealthy ‘preventative’ positions. For example staff may rigidly and strictly reinforce boundaries and rules or become overly understanding and attentive rather than managing interpersonal boundaries through discussion, understanding, appropriate limit setting and negotiation (see boundary see-saw model; Hamilton, Citation2010). Whilst there is no doubt that individual motivation and responsibility can play an important role in the occurrence of harmful behavior within custodial and forensic mental health settings, the organizational context and processes themselves are important (Love & Heber, Citation2002).

Within forensic contexts, trauma informed care (TIC) and trauma informed practice (TIP) offer ways to provide safe and effective services that can respond to trauma and to create and maintain effective boundaries. Trauma informed care typically refers to activity at a service level whilst practice typically concerns the work of individual practitioners (Knight, Citation2018). TIC/TIP are founded on the presence of five core principles - safety, trust, collaboration, choice, and empowerment (Harri & Fallot, Citation2001), and are distinct from trauma specific interventions which can be employed to provide treatment to those who have experienced trauma (Levenson & Willis, Citation2019). Although TIC/TIP within forensic services are still being developed (Willmot & Jones, Citation2022b), a central tenet is to provide care and practice that does not repeat, trigger or parallel prior trauma experiences, providing instead an experience of disparity i.e. one that doesn’t confirm beliefs about the world that evolved in the context of trauma (Briere, Citation2019). A range of guides, tools and materials exist which outline what trauma informed care is and common mis-perceptions of this concept (e.g. Sweeney & Taggart, Citation2018), and that provide guidance on developing a trauma informed approach at a societal (e.g. https://acehubwales.com; accessed 25/09/23) and service level (e.g. Bloom, Citation2013; SAMHSA, Citation2014).

The purpose of this paper is to present a trauma informed approach to organizational consultancy and worker supervision for supporting safe and effective criminal justice and forensic mental health service delivery.

A framework for trauma informed organizational consultancy, staff supervision and reflective practice

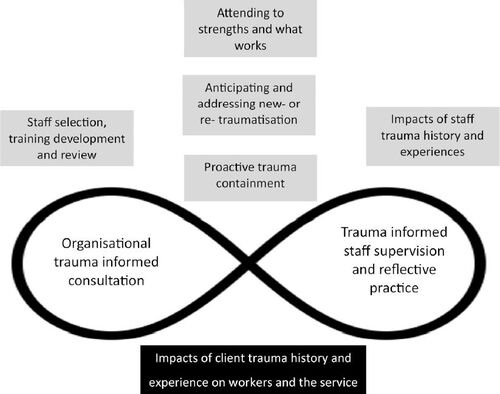

The framework presented within this paper offers a conceptualization of the proposed components of a trauma informed consultation and supervision approach for use within forensic services. This is informed by academic literature and learning derived from the authors’ practice which includes delivering services and providing training, consultancy and supervision to others. Whilst this describes the what of trauma informed consultation and supervision, it is intended that the reader will draw on published works (such as those linked within the text), and their own locally derived best practice methods to determine exactly how to embed such consultation and supervision within their service in a feasible and sustainable way. As shown in , organizational trauma informed consultation (OTIC) and trauma informed staff supervision (TISS)/trauma informed reflective practice (TIRP) are related and intertwined processes that attend to different aspects of the system; OTIC is typically a group based forum provided to service managers and leaders with a focus on the service and its context, TISS and TIRP describe regular one-to-one or group based sessions for staff delivering services with a focus on their work and wellbeing. Whilst the five components depicted can be relevant to and considered within OTIC and TISS/TIRP, ‘staff selection, training, development and review’ tend to be managerial functions and thus more likely to be considered within OTIC, whilst the ‘impacts of staff trauma and history’ are typically considered within TISS/TIRP where relevant and appropriate. The base of the framework comprises the ‘impacts of client trauma history and experience on workers and the service’. This is considered in the final section of this paper, illustrated through five examples, derived from the authors’ experiences.

Figure 1. Framework for trauma informed organizational consultancy, staff supervision and reflective practice.

Organizational trauma informed consultation (OTIC)

Trauma informed care and practice requires a proactive approach to establishing and maintaining systems, processes and service delivery that are compassionate, responsive, safe and effective. This requires senior leaders and managers (SLM) to use the context, policies, procedures and culture to inform how the service is organized and delivered and how successes and challenges are responded to. To achieve this, SLM need to attend to human factors such as the selection and training of staff, the setting of realistic and achievable expectations, enabling worker self-care, fostering caseload management and facilitating time away from direct client work (Pross, Citation2006). It also necessitates attention to professional boundaries, individual and team resilience, and staff opportunities for emotional processing (Smith, Citation2022). Organizational trauma informed consultation (OTIC) provides a mechanism for SLM to review their approaches and responses to service need and delivery with a consultant(s) who is outside the service. The organizational consultant’s role is to both facilitate a reflective space in which the domains described within can be considered, reviewed and revised, and to provide information, alternative perspectives and methods that can foster learning and new action. Such consultancy may be coupled with SLM engaging in a community of practice (Wenger, Citation2011) and drawing on freely available resources and toolkits such as those designed to foster trauma informed and ACEs aware provision, and that provide methods for service evaluation and audit (e.g. https://acehubwales.com; accessed 25/09/23).

OTIC provides a forum in which leaders and managers are supported to step back to review the service in it’s wider context and to test and challenge current service delivery. This can be informed by the use of TIC audit tools to examine adherence to TIC principles; service user feedback mechanisms, consultation exercises and representative panels, and formal evaluation of staff training, supervision and reflective practice. This critical self-evaluation can be used to develop action plans to ensure the service remains aligned with TIC principles. Consequently, organizational consultancy can enable SLM to maintain a clear and meaningful focus on the range of essential tasks relating to effective service delivery and to consider how learning and knowledge from other areas may help to inform service consolidation or development.

At present there is little written about, or training for, those seeking to develop specialist organization consultation skills. Whilst providing OTIC draws upon experience and skills relating to group supervision, management, coaching and consultancy, work is needed to scope such roles and to create developmental pathways for staff seeking to work in this way.

Trauma informed staff supervision (TISS) and trauma informed reflective practice (TIRP)

As with all forms of staff supervision and reflective practice, the aims of TISS and TIRP are to facilitate safe, ethical and effective working (normative), promote wellbeing (restorative) and enable personal and team development (formative) (Kadushin, Citation1992; Proctor, Citation1987, p. 280). However, balancing these sometimes competing aspects can create tensions (e.g. Ainslie et al., Citation2022). Whilst the evidence base for supervision is limited—for example a recent systematic review found no studies examining the support and supervision needs of prison officers (Forsyth et al., Citation2022), research has linked supervision to job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Hogan et al., Citation2009).

TISS and TIRP as conceptualized here anticipates that all staff regardless of profession, role or grade will have access to and engage in regular and meaningful supervision and/or reflective practice sessions. There is also an assumption that formal supervision will be supplemented by opportunities for peer group ‘reciprocal’ support and supervision (Bloom et al., Citation2013). However, it is essential to ensure those providing supervision are appropriately selected, trained and supported and are not “promoted to the clinical supervisor position because of seniority rather than clinical supervision training, education, skill, or knowledge” (Jones & Branco, Citation2020, p. 6). Therefore, supervisors and facilitators who provide TISS and TIRP need to be competent in forensic supervision practice (Davies, Citation2015, Citation2021) and trauma informed working. The forensic component requires skills and knowledge concerning forensic working, professional practice and working with complexities such as assessing the nature and extent of trauma and dissociation alongside the possibility of malingering (Brand et al., Citation2017; Brand & Brown, Citation2022). The supervision component requires competence in supervisory practice (e.g. Falender et al., Citation2004) including using models of supervision (e.g. Hawkins & Shohet, Citation2006) to help structure and guide TISS/TIRP (see also Knight (Citation2018) who provides an example of integrating the discrimination supervision model within trauma informed supervision). Consequently, supervisors and facilitators of TIRP should be given training and opportunities within their own supervision to develop knowledge and skills of the supervisory process. This should include topics such as how to prepare for supervision sessions, using an agenda to structure supervision, models of supervision, and boundaries within supervision (Davies, Citation2015). Learning approaches might include exercises which foster self-awareness, appropriate disclosure and self-reflection, strategies for taking on a (self) critical stance, and problem-solving skills. Those providing group based supervision or reflective practice should also have skills and knowledge in group process (Davies, Citation2015, e.g. pp. 39–41 & special topic 9). The trauma component should be developed through reference to local policy, practices and trauma and trauma informed practice knowledge and skills (e.g. Knight, Citation2018)

For some professions, engaging in supervision and reflective practice is a core expectation, however for others this will be a new and perhaps daunting task. For example, supervision might attend to emotional reactions (e.g. shame), countertransference (reactions and responses to the client, trauma narratives and treatment) and may bring previously hidden past experiences to the fore (Courtois, Citation2018). Thus supervisees are likely to need training and formal induction into supervision and reflective practice that includes orientation to the purpose, format and methods and models used. This should also include providing education to supervisees on the nature, impact(s) of and responses to trauma as well as vicarious resilience and posttraumatic growth (Courtois, Citation2018). Finally, those providing consultation, supervision or reflective practice need to access their own supervision/reflective practice to consider and review this work.

Key components of trauma informed organizational consultancy, supervision and reflective practice

Described below are the five components of trauma informed organizational consultancy, supervision and reflective practice as depicted by the shaded boxes within . Included within the detail of each component is guidance on how these might be operationalized within OTIC, TISS and TIRP, however within the framework, all components are considered to be of equal importance with no intended hierarchy of priority, effort or resource.

Staff selection, training, development and review

Healthy organizations have been characterized as being adaptable, having purpose, being emotionally well regulated and valuing diversity (Bloom & Farragher, Citation2013), with organizational support, training and supervision potentially moderating the impact of stressful events on staff (e.g. Ireland et al., Citation2022). However, sustaining high quality processes for staff selection, training, development and review can be challenging, relying upon organizational leadership and an understanding of organizational change principles in order to develop and maintain the culture and staffing regime (Davies et al., Citation2019).

Delivering trauma informed care requires staff who are suited to the specific job role and who can function well within the team and context within which they will work (person-role-team-environment fit). Consequently, creating and maintaining a TIC culture and regime starts with “getting—and retaining—the right people for the job” (Bloom, Citation2013, p. 110). However, it is important that attention to person-role-team-environment fit is an ongoing process to ensure any significant misfit between a person and their role or the service need is detected. Occasionally this may result from an individual(s) being fixed on alternative and counterproductive ways of service delivery, or an inability to change their practice or approach where necessary (the “never-adapters”; Bloom & Farragher, Citation2013, p. 280). Whilst changes to job roles or removal from a role must be based on clear reasoning and be guided by employment law, organizational consultation provides a space to consider such situations and to consider the implications and impacts of redeploying staff to new areas or tasks and how and “when to let staff go if needed” (Berger & Quiros, Citation2016, p. 152).

Developing and maintaining the skills of staff (regardless of role) requires ongoing organization commitment, and recognition of the scale and extent of trauma training that staff may require (Kumar et al., Citation2022). Training provision should be informed by relevant guidance (e.g. Cloitre et al., Citation2012; Cook & Newman, Citation2014) as well as the trauma treatment models adopted by the service. Staff with particular roles and responsibilities may require additional training, such as in providing trauma informed forensic mental health assessment (Goldenson et al., Citation2022) or in assessing specific factors such as dissociation (Brand et al., Citation2017). Shared learning that promotes both an understanding of trauma and of the impact of trauma on the individual can creating a strong foundation (e.g. Hiett-Davies, Citation2022). However, embedding ideas and actions into the culture and practice of the service requires consolidation of training through routine opportunities for learning in practice that are individually responsive and founded upon key adult learning principles (e.g. Knowles et al., Citation2014). Additionally worker supervision (Davies, Citation2015) and reflective practice (e.g. Kurtz, 2019; Schön, Citation1987) enable a move from teaching to facilitated adult learning, in which actions and decisions can be reviewed, appraised and future actions considered.

Proactive trauma containment

Proactive trauma containment (PTC), requires an organizational structure and culture that is alert and responsive to the experiences of all who live, work or access the service. At the most fundamental level, this requires the creation of a safe organization—one which attends to the physical, psychological, social and moral safety of all within it (Bloom & Farragher, Citation2013). PTC should consider the ways each aspect of the service is delivered and experienced (see Rapsey et al., Citation2023 for an example relating to 'ward rounds’), and to how individuals are supported to identify and report potential harmful situations or practices. OTIC provides senior leaders and managers with a forum examining events such as errors, injuries and complaints as these may indicator more general unease or problems elsewhere within the system. As noted by Bloom and Farragher (Citation2013, p. 216), such indicators may warn of “collective disturbance … a situation in which strong feelings get disconnected from their source and become attached to unrelated events or interactions … [these] travel down to the most vulnerable members of the community, who then act out.”.

PTC is an active, challenging and ongoing process. For many of those within forensic services, trauma is not in the past (i.e. post traumatic) but is present and ongoing. Consequently, behaviors may represent current trauma responses i.e. understandable reactions to traumatizing environments (Jones Citation2015, 2022). For example, hypervigilance may be self-protective when living in a setting for people described as a ‘grave and immediate danger’, and avoiding or disengaging from interventions may protect against experiencing vulnerability or being exposed to past traumatic experiences. Through organizational consultation senior leaders and managers can maintain policies and practices which foster physical, emotional and psychological safety to reduce potential sources of threat, shame and (re)traumatization. This may require senior leaders and managers to address challenges that arise in the wider organizational context, for example, challenging funding, resource and staffing constraints given that trauma-informed services typically require “significantly more resources in personnel, training, and ongoing support to allow for a limited caseload, …. intensive and consistent supervision, and opportunities for respite and self-care for practitioners such that they are best equipped to help …. traumatized clients” (Berger & Quiros, Citation2016, p. 152). Supervision and reflective practice complement organizational consultation by providing an opportunity for staff to consider their responses to individual client experiences and to dangerous and threatening, or shame and guilt inducing situations. Staff can also use TISS and TIRP to process the moral injury experienced when they are seen by clients as traumatizing or harmful despite their intentions and behaviors being aligned with providing compassionate and safe support and care.

Anticipating and addressing new- or re- traumatization

Leaders, managers and supervisors need to be alert to client, staff and setting characteristics that have been associated with new- or re- traumatization (e.g. for vicarious traumatization see Moulden & Firestone, Citation2007), and to the reactions that may be experienced by staff working in forensic contexts. For example, those working with individuals who have committed sexual offenses may initially experience ‘shock’ and ultimately experience burnout or adaptation (Farrenkopf, Citation1992). It is also important for leaders, managers and supervisors to recognize the ways in which past and current experiences may interact. For example, a personal history of trauma may be linked to the development of vicarious traumatization, whilst the amount of exposure to client trauma may impact secondary trauma (Baird & Kracen, Citation2006). Further, certain practices such as seclusion and restraint are likely to be re-traumatizing and thus require particular consideration (Hennessy et al., Citation2022).

Organizational consultation should support leaders and managers to actively measure and monitor the extent to which the service is able to provide trauma informed care (e.g. https://acehubwales.com/trace-toolkit/; accessed 25/09/23) and the organizational readiness to deal with specific facets such as vicarious trauma (e.g. Hallinan et al., Citation2019). In addition, organizational consultation should be used as a space for leaders and managers to establish and maintain policies and practices that directly support staff emotional well-being (Way et al., Citation2007). This includes ensuring that supervisors and reflective practice facilitators have competencies in working with secondary traumatization (see https://www.nctsn.org/resources/using-secondary-traumatic-stress-core-competencies-trauma-informed-supervision; accessed 26/03/23). Leaders, managers and supervisors should also be able to promote resources, coping strategies and approaches (e.g. for vicarious tramatisation see McCann & Pearlman, Citation1990; Pearlman & Saakvitne, Citation1995; Saakvitne & Pearlman, Citation1996) and provide access for staff to confidential (and external) interventions for vicarious trauma where this may be needed (Kim et al., Citation2022).

Attending to strengths and ‘what works’

Strengths based approaches have been promoted within forensic rehabilitation, antiracist practice and working with trauma (e.g. Day et al., Citation2022), whilst a focus on ‘what works’ has a long history within forensic settings. Those facilitating consultation, supervision and reflective practice should routinely attend to strengths and successes as these allow individuals and services to capitalize on areas in which skills, resources and competencies are already present. This can be important for morale as well as for providing a foundation from which to extend, develop or make changes to practice. Organizational consultancy provide opportunities to review service strengths, and to build a culture in which ‘what works’ is reported, recognized and learned from. Within TISS and TIRP, time should be given to explore and examine strengths, successes and what works in order to foster a balanced view of an individual’s work, role and value. The following examples from the authors’ experiences show some ways in which strengths and what works may be evident.

Recognizing co-operation and effective team working

by supporting individuals, groups of staff, managers and leaders to notice and learn from times when a) different perspectives within a team have been appreciated, b) solidarity has been expressed—especially at times of potential difference or when ‘splitting’ could have taken place, c) others have been valued because of their differing views or explanations.

Noticing and examining progress and change

can be fostered through simple questions about what has helped or been useful. Recognizing progress and change is important in and of itself, however attending to these may allow contributing factors or the change sequence to be identified. Such learning can then be used to guide or inform future work.

Care and treatment plan review and outcomes

at the individual client level can be supported through TISS/TIRP, whilst reviews of some or all the plans from a specific service may take place within OTIC. Periodically and purposefully taking stock of changes in domains such as need and risk can inform future actions to be taken by individual or groups of staff (e.g. captured in individual client care plans) or at an organizational level (e.g. staff training). Those providing consultancy, supervision and reflective practice should consider how they might support the use of formal methods to identify and index change.

Work as enriching and rewarding

Consultancy, supervision and reflective practice should provide a space to acknowledge and explore the positives experienced by staff of working with, and providing safe and effective services for service users. Recognizing that providing services to and working with those with complex needs can be profoundly enriching and affirming can provide balance to those narratives which recognize the potential for harm, and that may contribute to disengagement or emotional exhaustion over time.

Impacts of staff trauma history and experience (supervisee and supervisor)

As noted in the introduction, staff experiences of historic and current trauma may be relatively common yet overlooked. However, “People who have experienced … toxic stress … do not just ‘leave it at the door’ when they enter the workplace.” (Bloom et al., Citation2013, p. 131). Consequently those providing consultancy, supervision and reflective practice will need to be alert to the potential presence of trauma experience, symptoms and responses within members of staff, managers, leaders and in themselves (Bloom et al., Citation2013).

Consultancy, supervision and reflective practice should provide a compassionate, collaborative, respectful and thoughtful space to enable staff to recognize and process their emotional reactions (Barros et al., Citation2020). Provide space that “is safe and feels safe” (Berger & Quiros, Citation2016; p. 151 (authors italics)) is critical if experiences - including those relating to trauma and adversity - can be discussed. Promoting awareness of potential ‘numb spots’—the absence of an emotional response (Davies, Citation2015), may have particular salience when past, new and re-traumatization are considered. Consultancy, supervision and reflective practice should validate the difficult nature of the work being undertaken and the potential impact of the work on staff. This should be coupled with staff education about positive and negative personal coping strategies (VanDeusen & Way, Citation2006), social support, emotional validation and proactive self-care (Knight, Citation2018).

Impacts of client trauma history and experience on workers and the service

Client trauma experience(s) can impact practice and the relational context in which OTIC, TISS and TIRP take place (shown at the base of ). Anticipating and recognizing how client trauma may present itself and how it might lead to reactions within individuals and systems is important to effective consultation and supervision. Previously identified impacts in the form of ‘traps’ that can be present when working with trauma survivors (Chu, Citation2008) and the five examples outlined below (derived from the authors’ experiences) provide a starting point for identifying and working with such impacts.

Staff viewed as perpetrators of harm

Staff can be experienced by clients as harmful even though there is no intention by the worker(s) to cause harm or distress. Client trauma re-living can be unintentionally triggered by perceptions of the worker’s power and privilege derived through their race, culture, gender and sexuality, or their role or position within the organization. Additionally, physical characteristics, mannerisms and accent/voice tone may be reminiscent, to the service user, of a past abuser. Within OTIC, TISS and TIRP, viewing the service or intervention through the ‘lens’ of the service users’ traumatic experiences can be helpful in identifying such factors. In addition, power dynamics between the service user(s) and worker(s) based on cultural expectations and experiences or current/past contextual factors can be anticipated and collaborative responses implemented.

Those providing consultation and supervision should facilitate examination of (mis)attributions about the potential to be perceived as harmful and the ways in which power dynamics may be downplayed or transference reactions overlooked. The roles of victim, persecutor and rescuer, as described in the Drama Triangle (Karpman, Citation1968), can provide a framework for discussing relationships between the service user, the worker(s) and the service. Including the role of bystander to this model can also be useful. In addition, Malan’s Triangles of ‘persons’ and ‘conflict’ (Malan, Citation1995), can provide an explicit framework for making links between current and past relationships and emotional experience and response. Finally, the concept of parallel process (Searles, Citation1955) can be used to consider how senior managers’ experiences of the consultant (e.g. as demanding) may illuminate the experience of the staff group in relation to the managers whilst staff experiences of their supervisor (e.g. as critical) may reveal facets of the client’s experience of the staff.

Enactments

Enactments (‘acting out’) describe client or worker actions and responses in the present that are driven by past experience such as trauma rather than the here and now events. OTIC, TISS and TIRP provide ‘time out’ to recognize and review responses which may have been automatic and unthinking or driven by (extreme) emotion. Sudden changes to patterns in thinking, feeling, behavior and interaction may point to situations in which enactments might be taking place. Identifying enactments allows managers, leaders and staff to develop an intentional plan of actions and responses based on new thinking and approaches rather than unwittingly playing out a pattern of behavior which is harmful to the service user, staff member or both. Where enactments lead to a relationship breakdown, those providing consultancy or supervision should facilitate exploration of how the rupture might be repaired and how healthy and effective boundaries can be reinstated.

Trauma driven reasons for client non-engagement

Non or avoidant engagement can significantly hamper work with people who have complex trauma histories. A key dilemma for staff and services to negotiate is the inclination to either a) withdraw an intervention before trying to get through an impasse or b) persist with an intervention and ‘push the individual’ into engagement. Both responses have the potential to be re-traumatizing—withdrawal can be experienced as a lack of concern reminiscent of prior caregiver neglect and persistence replaying intrusive or over-involved, coercive/harassing caregiver dynamics. Using OTIC, TISS or TIRP to undertake an open and compassionate exploration of the service user’s reluctance or disengagement can provide the basis for an engagement formulation to be developed to understand the ways in which trauma may have impacted on engagement (Jones & Guha Citation2020). Where relevant this should include how reluctance or avoidance on the part of staff members or the wider staff team may be present, potentially borne out of feeling rejected by an individual they have tried to support.

Working intentionally with service user trauma

Determining whether, when and how to undertake formalized trauma interventions should be informed by service guidance, service readiness, client readiness, the current evidence base for treatment(s) (Malik et al., Citation2023) and the ways in which (ongoing) informed consent of the service user can be meaningfully obtained. OTIC can assist managers and leaders to maintain policy and guidance that describes the parameters for trauma interventions and how such decisions might be made, and to ensure that staff are adequately trained and supported for this work. TISS and TIRP have important roles in decision making concerning whether or not to proceed with trauma focussed interventions with this individual, at this time, in this setting, and in monitoring treatment where it takes place. This includes aiding staff to describe possible client responses to treatment and to detail how adverse therapeutic reactions and outcomes (iatrogenic responses; Jones, Citation2007), including offending or offense paralleling behaviors (Daffern et al., Citation2010), will be monitored, managed and addressed. Developing a ‘responses conceptualization’ that describes possible responses from the client and others they relate to can support informed decision making and wider team involvement prior to and during treatment delivery. Wider systemic considerations within TISS and TIRP should include how the wider staff team will be briefed e.g. what to expect or attend to, how to respond. The response conceptualization should also identify stop criteria i.e. factors or indicators which signal that the intervention is not going according to plan or is not helping, and how these will be monitored and responded to. Those providing consultation or supervision should be empowered to act if insufficient preparations have been made or if those that are in place are not proving to be effective.

Attending to potentially hidden trauma

Individual trauma histories can remain hidden or their details unknown. However, in the absence of an acknowledged trauma account, it can be helpful, indeed critical at times, for TISS and TIRP to support staff and the team to generate and test hypotheses about a client’s current presentation based on speculation about past trauma. Creating an ‘assumed trauma formulation’ involves the development of working hypotheses which detail how trauma experiences might explain the way(s) the client currently thinks, feels, behaves and interacts. As with all hypotheses, these should be constructed in ways which enable them to be tested and refuted or supported as appropriate. Such testing can take many forms including presenting the hypothesis to the client, seeking third party information e.g. from family members or social services, or by examining the impact on the client of changes made to the context, the environment or to interactions based on the assumed trauma formulation. To reduce confirmation bias (Davies 2023), prior consideration should be given to the threshold for accepting and rejecting the hypothesis with effort given to identifying plausible alternative hypotheses such as neuropsychological or cultural explanations.

Next steps

The framework offered here gives rise to a number of important next steps. Creating training and development routes for staff to develop explicit skills and competencies in organizational trauma informed consultancy is important to enable good practice in this area. Establishing an international community of practice or special interest group may be another way to consolidate practice and learning to work toward this goal. At a local level, services could make use of focus groups that include staff and clients to help shape and inform organizational development and problem solving. In addition, establishing a system for supervisors and consultants to share examples of their work and the associated outcomes, both positive and negative could provide an accessible resource for further practice and research in this area. The framework offered here is a first step toward organizational trauma informed consultation and worker trauma informed forensic supervision and reflective practice. Whilst there are many ways researchers and practitioners could help to test, refine and improve the framework a first step may be to create and test a logic model derived from it.

Conclusion

By its very nature, work in forensic services has the potential to be both ‘trauma full’ and ‘traumatizing’. Organizational trauma informed consultation provides a space for thoughtful and intentional decision making amongst service commissioners, managers and leaders, whilst trauma informed staff supervision and reflective practice provide mechanisms for ongoing staff support and development. The framework presented in this paper provides tangible ways for those tasked with leading, managing and supervising staff to strive toward creating and maintaining safe and effective trauma informed forensic services. This includes supporting those factors which might contribute to healing from trauma—authenticity i.e. noticing, experiencing and sharing our true wants and needs; agency i.e. “the capacity to freely take responsibility for our existence” (p. 377); fostering the healthy experience and expression of anger; acceptance i.e. recognizing that “in the moment things cannot be other than how they are” (p. 380) and compassion (Maté & Maté, Citation2022).

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Adams, C. R., Grad, R. I., & Nice, M. L. (2023). An Ecological Perspective of Intergenerational Trauma: Clinical Implications. Journal of Counseling Research and Practice, 8(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.56731/2688-3996.1065

- Ainslie, S., Fowler, A., Phillips, J., & Westaby, C. (2022). ‘A nice idea but….’: Implementing a reflective supervision model in the National Probation Service in England and Wales. Reflective Practice, 23(5), 525–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2022.2066075

- Allen, E. (2023). See, Think, Act, 3rd Edition (3rd ed.). Royal College of Psychiatrists Quality Network for Forensic Mental Health.

- Baird, K., & Kracen, A. C. (2006). Vicarious traumatization and secondary traumatic stress: A research synthesis. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 19(2), 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070600811899

- Barros, A. J., Teche, S. P., Padoan, C., Laskoski, P., Hauck, S., & Eizirik, C. L. (2020). Countertransference, defense mechanisms, and vicarious trauma in work with sexual offenders. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 48(3), 302–314. https://doi.org/10.29158/JAAPL.003925-20

- Berger, R., & Quiros, L. (2016). Best practices for training trauma-informed practitioners: Supervisors’ voice. Traumatology, 22(2), 145–154. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000076

- Bloom, S. L. (2013). The sanctuary model. In Treating complex traumatic stress disorders in children and adolescents: Scientific foundations and therapeutic models (pp. 277–294). Guilford Press,

- Bloom, S. L., & Farragher, B. (2013). Restoring sanctuary: A new operating system for trauma-informed systems of care. Oxford University Press.

- Bloom, S. L., Yanosy, S., & Harrison, L. C. (2013). A reciprocal supervisory network: The sanctuary model. In D. Murphy, S. Joseph, & B. Harris (Eds.), Trauma and the therapeutic relationship: Approaches to process and practice (pp. 126–146). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brand, B. L., & Brown, L. S. (2022). True drama or true trauma?: Forensic trauma assessment and the challenge of detecting malingering. In Dissociation and the Dissociative Disorders (pp. 673–683). Routledge.

- Brand, B. L., Schielke, H. J., Brams, J. S., & DiComo, R. A. (2017). Assessing Trauma-Related Dissociation in Forensic Contexts: Addressing Trauma-Related Dissociation as a Forensic Psychologist, Part II. Psychological Injury and Law, 10(4), 298–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12207-017-9305-7

- Briere, J. (2019). Treating risky and compulsive behavior in trauma survivors. Guilford Publications.

- Chu, J. A. (2008). Ten traps for therapists in the treatment of trauma survivors. In Personality Disorder: The Definitive Reader (pp. 210–228). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Cloitre, M., Courtois, C., Ford, J., Green, B., Alexander, P., Briere, J., & Van der Hart, O. (2012). The ISTSS expert consensus treatment guidelines for complex PTSD in adults. Retrieved from: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=c5eaffe436518684793cb359a7856797853b512c

- Cook, J. M., & Newman, E, The New Haven Trauma Competency Group. (2014). A consensus statement on trauma mental health: The New Haven Competency Conference process and major findings. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6(4), 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036747

- Courtois, C. A. (2018). Trauma-informed supervision and consultation: Personal reflections. The Clinical Supervisor, 37(1), 38–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2017.1416716

- Daffern, M., Jones, L., & Shine, J. (2010). Offence paralleling behaviour: A case formulation approach to offender assessment and intervention. John Wiley & Sons.

- Davies, J. (2015). Supervision for Forensic Practitioners. Routledge.

- Davies, J. (2021). Chapter 48: Staff supervision in forensic contexts. In J. M. Brown, & M. A. H. Horvath (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of forensic psychology (2nd ed.) Cambridge University Press.

- Davies, J. (2022). Chapter 11: Supervising assessment practice. In G. C. Liell, M. J. Fisher, & L. F. Jones (Eds.), Challenging bias in forensic psychological assessment and testing (pp. 199–212). Routledge.

- Davies, J., Pitt, C., & O'Meara, A. (2019). Learning lessons from implementing enabling environments within prison and probation: Separating standards from process. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 63(2), 218–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X18790713

- Day, A., Woldgabreal, Y., & Butcher, L. (2022). Cultural Bias in Forensic Assessment: Considerations and Suggestions. In G. C. Liell, M. J. Fisher, L. F. Jones (Ed.), Challenging Bias in Forensic Psychological Assessment and Testing: Theoretical and Practical Approaches to Working with Diverse Populations (pp. 245–258). Routledge.

- Facer-Irwin, E., Karatzias, T., Bird, A., Blackwood, N., & MacManus, D. (2022). PTSD and complex PTSD in sentenced male prisoners in the UK: Prevalence, trauma antecedents, and psychiatric comorbidities. Psychological Medicine, 52(13), 2794–2804. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720004936

- Falender, C. A., Cornish, J. A., Goodyear, R., Hatcher, R., Kaslow, N. J., Leventhal, G., Shafranske, E., Sigmon, S. T., Stoltenberg, C., & Grus, C. (2004). Defining competencies in psychology supervision: A consensus statement. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 60(7), 771–785. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20013

- Farrenkopf, T. (1992). What happens to therapists who work with sex offenders? Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 18(3-4), 217–224. https://doi.org/10.1300/J076v18n03_16

- Forsyth, J., Shaw, J., & Shepherd, A. (2022). The support and supervision needs of prison officers working within prison environments. An empty systematic review. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 33(4), 475–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2022.2085150

- Fosse, R., Eidhammer, G., Selmer, L. E., Knutzen, M., & Bjørkly, S. (2020). Strong Associations Between Childhood Victimization and Community Violence in Male Forensic Mental Health Patients [Original Research]. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 628734. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.628734

- Goldenson, J., Brodsky, S. L., & Perlin, M. L. (2022). Trauma-informed forensic mental health assessment: Practical implications, ethical tensions, and alignment with therapeutic jurisprudence principles. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 28(2), 226–239. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000339

- Gradus, J. L., & Galea, S. (2022). Reconsidering the definition of trauma. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 9(8), 608–609. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00196-1

- Hallinan, S., Shiyko, M. P., Volpe, R., & Molnar, B. E. (2019). Reliability and validity of the vicarious trauma organizational readiness guide (VT‐ORG). American Journal of Community Psychology, 64(3-4), 481–493. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12395

- Hamby, S., Elm, J. H. L., Howell, K. H., & Merrick, M. T. (2021). Recognizing the cumulative burden of childhood adversities transforms science and practice for trauma and resilience. The American Psychologist, 76(2), 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000763

- Hamilton, L. (2010). The boundary seesaw model: Good fences make for good neighbours. In Using time, not doing time: Practitioner perspectives on personality disorder and risk (pp. 181–194). Wiley.

- Harris, M., & Fallot, R. (2001). Using trauma theory to design service systems. New Directions for mental health services. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Hawkins, P., & Shohet, R. (2006). Supervision in the Helping Professions. (3rd ed.). McGraw Hill.

- Hennessy, B., Hunter, A., & Grealish, A. (2022). A qualitative synthesis of patients’ experiences of re‐traumatisation in acute mental health inpatient settings. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 30(3), 398–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12889

- Hiett-Davies, V. (2022). Trauma-Informed Care and Culture Change in an NHS Forensic Service. In P. Willmot & L. Jones (Eds.), Trauma-Informed Forensic Practice (pp. 380–395). Routledge.

- Hilton, N. Z., Ham, E., Rodrigues, N. C., Kirsh, B., Chapovalov, O., & Seto, M. C. (2020). Contribution of critical events and chronic stressors to PTSD symptoms among psychiatric workers. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 71(3), 221–227. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900226

- Hogan, N. L., Lambert, E. G., Jenkins, M., & Hall, D. E. (2009). The Impact of Job Characteristics on Private Prison Staff: Why Management Should Care. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 34(3-4), 151–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-009-9060-8

- Hughes, K., Bellis, M. A., Hardcastle, K. A., Sethi, D., Butchart, A., Mikton, C., Jones, L., & Dunne, M. P. (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 2(8), e356–e366. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4

- Ireland, C. A., Chu, S., Ireland, J. L., Hartley, V., Ozanne, R., & Lewis, M. (2022). Extreme stress events in a forensic hospital setting: Prevalence, impact, and protective factors in staff. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 43(5), 418–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2021.2003492

- Jones, C. T., & Branco, S. F. (2020). Trauma‐informed supervision: Clinical supervision of substance use disorder counselors. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling, 41(1), 2–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaoc.12072

- Jones, L. F. (2007). Iatrogenic interventions with personality disordered offenders. Psychology, Crime & Law, 13(1), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160600869809

- Jones, L. F. (2015). The Peaks unit: From a pilot for ‘untreatable’ psychopaths to trauma- informed milieu therapy. Prison Service Journal, 218, 17–23.

- Jones, L. F. (2022). Trauma informed risk assessment and intervention: Understanding the role of triggering contexts and offence related altered states of consciousness (ORASC). In P. Willmot & L. F. Jones (Eds.), Trauma informed care In forensic practice. Routledge.

- Jones, L., & Guha, S. (2020). Clinical case formulation of suboptimal engagement. In A. Hadler, S. Sutton, & L. Osterberg (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of healthcare treatment engagement: Theory, research, and clinical practice.

- Kadushin, A. (1992). Supervision in social work: Third Edition. Columbia University Press.

- Karpman, S. (1968). Fairy tales and script drama analysis. Transactional Analysis Bulletin.

- Kelly, E. L., Subica, A. M., Fulginiti, A., Brekke, J. S., & Novaco, R. W. (2015). A cross‐sectional survey of factors related to inpatient assault of staff in a forensic psychiatric hospital. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(5), 1110–1122. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12609

- Kim, J., Chesworth, B., Franchino-Olsen, H., & Macy, R. J. (2022). A scoping review of vicarious trauma interventions for service providers working with people who have experienced traumatic events. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 23(5), 1437–1460. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838021991310

- Knight, C. (2018). Trauma-informed supervision: Historical antecedents, current practice, and future directions. The Clinical Supervisor, 37(1), 7–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2017.1413607

- Knowles, M. S., Holton, E. F., III, & Swanson, R. A. (2014). The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. Routledge.

- Kumar, S. A., Brand, B. L., & Courtois, C. A. (2022). The need for trauma training: Clinicians’ reactions to training on complex trauma. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 14(8), 1387–1394. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000515

- Levenson, J. S., & Willis, G. M. (2019). Implementing trauma-informed care in correctional treatment and supervision. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 28(4), 481–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2018.1531959

- Love, C. C., & Heber, S. A. (2002). Staff-patient erotic boundary violations: Part three - environmental factors. On the Edge, 8(1), 1, 12–16.

- Malan, D. (1995). Individual psychotherapy and the science of psychodynamics (2nd ed.). Butterworth Heinemann.

- Malik, N., Facer-Irwin, E., Dickson, H., Bird, A., & MacManus, D. (2023). The effectiveness of trauma-focused interventions in prison settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 24(2), 844–857. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211043890

- Maté, G., & Maté, D. (2022). The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness & Healing in a Toxic Culture. Random House.

- McCann, I. L., & Pearlman, L. A. (1990). Vicarious traumatization: A framework for understanding the psychological effects of working with victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 3(1), 131–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00975140

- Moulden, H. M., & Firestone, P. (2007). Vicarious traumatization: The impact on therapists who work with sexual offenders. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 8(1), 67–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838006297729

- Online, B. N. (2023). HMP Berwyn: Prisoner relationships see 18 staff quit or sacked. Retrieved 27th March 2023 from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-64939208

- Pearlman, L. A., & Saakvitne, K. W. (1995). Trauma and the therapist: Countertransference and vicarious traumatization in psychotherapy with incest survivors. WW Norton & Co.

- Petruccelli, K., Davis, J., & Berman, T. (2019). Adverse childhood experiences and associated health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 97, 104127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104127

- Pettman, H., Loft, N., & Terry, R. (2020). “We Deal Here With Grey”: Exploring Professional Boundary Development in a Forensic Inpatient Service. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 16(2), 118–125. https://journals.lww.com/forensicnursing/fulltext/2020/06000/_we_deal_here_with_grey___exploring_professional.8.aspx https://doi.org/10.1097/JFN.0000000000000250

- Proctor, B. (1987). Supervision: A cooperative exercise in accountability. In M. Marken & M. Payne (Eds.), Enabling and ensuring. Supervision in practice. National Youth Bureau.

- Pross, C. (2006). Burnout, vicarious traumatization and its prevention. Torture, 16(1), 1–9.

- Rapsey, S., Watson, R., & Dafforn, H. (2023). ‘An equal seat at the table’: Service users’ experiences of ward rounds in secure care, through the lens of trauma-informed care principles. Clinical Psychology Forum, 1(364), 38–44. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpscpf.2023.1.364.38

- Ryder, A. L., Azcarate, P. M., & Cohen, B. E. (2018). PTSD and physical health. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20(12), 116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-018-0977-9

- Saakvitne, K. W., & Pearlman, L. A. (1996). Transforming the pain: A workbook on vicarious traumatization. WW Norton & Co.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2014). SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma14-4884.pdf

- Saunders, K. R. K., McGuinness, E., Barnett, P., Foye, U., Sears, J., Carlisle, S., Allman, F., Tzouvara, V., Schlief, M., Vera San Juan, N., Stuart, R., Griffiths, J., Appleton, R., McCrone, P., Rowan Olive, R., Nyikavaranda, P., Jeynes, T., K, T., Mitchell, L., … Trevillion, K. (2023). A scoping review of trauma informed approaches in acute, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care. BMC Psychiatry, 23(1), 567. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05016-z

- Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. Jossey-Bass.

- Searles, H. F. (1955). The Informational Value of the Supervisor’s Emotional Experiences. †Psychiatry, 18(2), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1955.11023001

- Smith, M. (2022). The Impact on Staff of Trauma-Informed Work in Forensic Settings. In P. Willmot & L. Jones (Eds.), Trauma-Informed Forensic Practice (pp. 363–379). Routledge.

- Stinson, J. D., Quinn, M. A., Menditto, A. A., & LeMay, C. C. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences and the onset of aggression and criminality in a forensic inpatient sample. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 20(4), 374–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2021.1895375

- Sweeney, A., & Taggart, D. (2018). (Mis)understanding trauma-informed approaches in mental health. Journal of Mental Health, 27(5), 383–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2018.1520973

- VanDeusen, K. M., & Way, I. (2006). Vicarious trauma: An exploratory study of the impact of providing sexual abuse treatment on clinicians’ trust and intimacy. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 15(1), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1300/J070v15n01_04

- Way, I., VanDeusen, K., & Cottrell, T. (2007). Vicarious trauma: Predictors of clinicians’ disrupted cognitions about self-esteem and self-intimacy. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 16(4), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1300/j070v16n04_05

- Wenger, E. (2011). Community of Practice: A Brief Introduction. Retrieved 21/09/23, from https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1794/11736/A%20brief%20introduction%20to%20CoP.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Willmot, P., & Jones, L. (2022a). Introduction. In P. Willmot & L. Jones (Eds.), Trauma-informed forensic practice (pp. 1–11). Routledge.

- Willmot, P., & Jones, L. (2022b). Trauma-Informed Forensic Practice. Routledge.

- Zeynel, Z., & Uzer, T. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences lead to trans-generational transmission of early maladaptive schemas. Child Abuse & Neglect, 99, 104235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104235