Abstract

Depression is more prevalent among sexual minority adults than heterosexual adults. Whilst research has shown self-compassion is related to lower levels of depressive symptoms, few studies have focused on sexual minority adults. Furthermore, few studies have examined the relationship between the positive (self-warmth) and negative (self-coldness) components of self-compassion and depressive symptoms. This study aimed to investigate whether self-warmth and self-coldness were associated with depressive symptoms among sexual minority adults and whether these relations were moderated by gender and sexual orientation. An international sample of 439 sexual minority women aged 18 to 69 years (M = 30.21, SD = 10.70) and 391 sexual minority men aged 18 to 71 years (M = 32.20, SD = 11.74) completed the Center for Epidemiology-Depression Scale and the Self-Compassion Scale. Results indicated both self-warmth and self-coldness were significantly associated with depressive symptoms, however, self-coldness explained more unique variance (12%) than self-warmth (1%). Higher levels of self-warmth were significantly associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms and the association was not conditional on gender or sexual orientation. Higher levels of self-coldness were associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms. This association was conditional on sexual orientation but not gender. The association was stronger for bisexual adults than monosexual adults. Interventions such as compassion-focused therapy that target self-coldness among sexual minority adults may be beneficial for reducing depressive symptoms, particularly bisexual adults.

Introduction

Depression is on the rise globally and affects more than 264 million people worldwide (World Health Organisation, Citation2020). Sexual minority adults are significantly more likely to experience depressive symptoms compared with heterosexual adults. For example, a recent meta-analysis indicated monosexual (gay/lesbian) adults are 1.97 times and bisexual adults are 2.70 times as likely to experience depression compared with heterosexual adults (Wittgens et al., Citation2022). Among sexual minority adults, women experience more depressive symptoms than men (Ferlatte et al., Citation2020) and bisexual adults experience more depressive symptoms than monosexual adults (Ross et al., Citation2018; Wittgens et al., Citation2022). There also appears to be an interaction between gender and sexual orientation, where the magnitude of the difference in prevalence between monosexual and bisexual adults is greater for women than men (Ross et al., Citation2018). Recent research with a nationally representative sample of US adults indicated that bisexual women are twice as likely to experience depressive symptoms than bisexual men, lesbian women, and gay men (Dulai & Schmidt, Citation2023), indicating the impact of multiple oppressions including sexism, heterosexism, and binegativity.

Minority stress theory can be used to explain the disparity in the prevalence of depression between heterosexual and sexual minority individuals (Brooks, Citation1981; Meyer, Citation2003). The minority stress theory posits specific stress processes affect the health of sexual minority adults due to society’s negative views of their minority sexual identity. Minority stress processes are described as occurring along a continuum from distal stressors to proximal stressors (Meyer, Citation2003). Distal stressors are defined as external objective stressful events and chronic strains occurring outside the person (e.g. abuse, discrimination, and prejudice). The experience of distal stressors can trigger proximal stressors, defined as the subjective internal processes experienced by the person living in a heterosexist society (e.g. expectations of rejection, stigma, internalized homophobia, and sexual orientation concealment; Meyer, Citation2003).

Further explaining minority stress, Hatzenbuehler et al. (Citation2009) found that higher levels of rumination and suppression of emotions, in response to stigma-related stressors such as discrimination, were associated with higher levels of psychological distress among sexual minority adults. Furthermore, Hatzenbuehler et al. (Citation2009) suggest that although the emotion-regulation strategy of suppression may serve as a self-protective factor, suppression predicted higher levels of psychological distress in response to stigma-related events. Similarly, possessing a concealable stigma poses psychosocial challenges among sexual minority adults, and efforts to conceal a stigma have been found to have adverse impacts on daily life that pose psychosocial challenges (Pachankis, Citation2007; Pachankis et al., Citation2020).

Research has found that these stressors place sexual minority adults at higher risk of poor mental health, particularly depression, compared to heterosexual adults (de Lira & de Morais, Citation2017; Lindquist et al., Citation2016; Meyer, Citation2003, Citation2015). Furthermore, the additional minority stress experienced by bisexual individuals, particularly binegativity (Friedman et al., Citation2014), can explain why they experience higher levels of depressive symptoms compared with monosexual sexual minority adults.

Resilience is important in understanding minority stress (Meyer, Citation2015), as it acts as a protective factor in ameliorating the stress response (Loue & Sajatovic, Citation2009; Lyons, Citation2015; Meyer, Citation2015). Protective factors comprise internal and external factors that contribute to positive psychosocial outcomes when facing stressful experiences or adversity (de Lira & de Morais, Citation2017). The construct of self-compassion is viewed as an individual-based resiliency factor (Neff & McGehee, Citation2010), protective against depressive symptoms (Neff, Citation2003a; Trompetter et al., Citation2017), and holds clinical relevance in the treatment of depressive symptoms (Finlay-Jones’, Citation2017; Wilson et al., Citation2018). For example, Finlay-Jones’ (Citation2017) narrative review provides the rationale for self-compassion working to reduce depressive symptoms through an emotion regulation framework. Finlay-Jones’ (Citation2017) argues that self-compassion may be protective against depressive symptoms through emotional regulation processes such as cognitive reappraisal, greater emotional awareness, and emotional acceptance. The capacity to self-soothe and be less reactive to adverse experiences are further benefits of being self-compassionate.

Self-compassion is defined as being kind, caring, understanding, and taking a non-judgmental attitude toward oneself in times of stress or suffering (Neff, Citation2003a). Self-compassion comprises six components measuring opposed approaches: self-kindness versus self-judgment, common humanity versus isolation, and mindfulness versus over-identification (Neff, Citation2003b). Therefore, self-compassion consists of three positive components (referred to as self-warmth), namely self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness, and three negative components (referred to as self-coldness), namely self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification (Neff, Citation2003a, Citation2003b). Self-kindness refers to being caring, kind, and understanding toward oneself as opposed to being judgmental, harshly critical, and negative in the evaluation of oneself. Common humanity refers to acknowledging that one’s problems or stress are part of human life as opposed to viewing the experiences as isolating and separate from the rest of the human experience. Mindfulness refers to maintaining a healthy awareness of painful thoughts and feelings arising from bad experiences as opposed to over-identifying with them and ruminating on the negative experiences (Neff, Citation2003a, Citation2003b). The ability to extend forgiveness, provide compassion, and emotional safety to oneself without the fear of self-condemnation is an integral feature of self-compassion (Neff, Citation2003b).

Self-compassion has been linked to lower levels of depressive symptomology within the general population. A recent meta-analysis of 271 studies indicated that higher levels of self-compassion were associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms, with a large effect size (Lou et al., Citation2022). However, research on self-compassion has predominantly investigated self-compassion as a single construct as opposed to investigating the protective nature of the self-compassion components (Körner et al., Citation2015; Neff et al., Citation2007). Research indicates the positive and negative components of self-compassion may relate differently to depressive symptomology (Lopez, Sandeman, & Schroevers, Citation2018; Lou et al., Citation2022; Muris & Petrocchi, Citation2017) and psychological distress (Chio et al., Citation2021). A meta-analysis of the relationship between the positive and negative components of self-compassion and psychopathology showed the negative components were more strongly linked to psychopathology than the positive components (Muris & Petrocchi, Citation2017). Similarly, Lou et al. (Citation2022) found that the effect size of self-coldness was similar to the effect size for the total self-compassion score, whereas the effect size for self-warmth was smaller than the effect size for the total score. It has been argued the unitary score will likely result in an inflated relationship between self-compassion and depressive symptomology or psychopathology (Muris & Petrocchi, Citation2017).

Gender differences have been documented for self-compassion. A meta-analysis found men score significantly higher on the total self-compassion score compared to women, with a small effect size (Yarnell et al., Citation2015). This gender difference may be due to women scoring higher than men on the negative subscales that constitute the self-coldness component of self-compassion (Lopez, Sanderman, Ranchor, et al., Citation2018). This proposal is consistent with research on constructs similar to elements of self-coldness. For example, women score higher on negative self-talk (i.e. self-judgment; DeVore & Pritchard, Citation2013) and rumination (i.e. over-identification; Johnson & Whisman, Citation2013) than men. Also, women with Major Depressive Disorder reported higher levels of self-criticism than men with Major Depressive Disorder (Luyten et al., Citation2007). Discussion of why these gender differences exist is rare, with the exception of the difference in rumination. For example, it has been proposed that women engage in rumination more than men as it is a learnt gender-stereotyped coping behavior which is linked to gender role identity (Broderick, Citation1998; Cox et al., Citation2010). Broderick and Korteland (Citation2004) argued that women use rumination more often as they experience more stressors outside their control than men.

Self-compassion among sexual minority adults

Research has begun to investigate the association between self-compassion and depressive symptoms among sexual minority adults. Self-compassion has been associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms among sexual minority adults (Bell et al., Citation2018; Brown-Beresford & McLaren, Citation2022; Matos et al., Citation2017; Ristvej et al., Citation2023). A recent study with an international sample of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and plurisexual adults found that higher levels of self-compassion, self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness, and lower levels of self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification were associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms among sexual minority adults (Shakeshaft & McLaren, Citation2022). When all six components were entered simultaneously into a multiple regression analysis, only the three self-coldness components were associated with depressive symptoms. A similar result was found in a sample of sexual minority women; only the three negative components were significantly related to depressive symptoms (Brown-Beresford & McLaren, Citation2022). In a study of sexual minority men, both self-warmth (0.5%) and self-coldness (18.7%) explained unique variance in depressive symptoms, however, self-coldness explained substantially more unique variance (Ristvej et al., Citation2023). Drawing on these previous studies, it is likely that self-coldness, and not self-warmth, explains unique variance in depressive symptoms among sexual minority adults.

Few studies have investigated gender differences in self-compassion among sexual minority adults. Bell et al. (Citation2018) found no gender difference between lesbian women and gay men on the total self-compassion score. In a study investigating the six components of self-compassion, Shakeshaft and McLaren (Citation2022) found that sexual minority women scored significantly higher on self-judgment and over-identification and significantly lower on mindfulness than sexual minority men. Chong and Chan (Citation2023) found no gender differences in self-warmth and self-coldness among their sample of sexual minority adults. Each study used different factors for the analyses and combined with the inconsistent findings among the few studies conducted, gender warrants further attention. Also, the lack of gender differences in these studies of sexual minority adults is in contrast to research in the general population, where men typically score higher on self-compassion than women (Yarnell et al., Citation2015), as well as documented differences in levels of depressive symptoms among sexual minority women and men (Ferlatte et al., Citation2020).

A paucity of research has examined whether the relationship between self-compassion and depressive symptoms is conditional on gender. In a study investigating whether gender moderated the relationships between each of the six components of self-compassion and depressive symptoms among sexual minority adults, results showed that gender moderated only one relationship, between common humanity and depressive symptoms (Shakeshaft & McLaren, Citation2022). Common humanity was more strongly related to lower levels of depressive symptoms among women compared to men. In the broader literature, there is evidence gender moderates the association between components of self-compassion and depressive symptoms (Chio et al., Citation2021). For example, a meta-analysis indicated that gender moderated the relationship between the three components of self-warmth and psychological distress The associations of self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness with psychological distress were stronger for women than men. A study of older adults found that mindfulness, self-judgment, and isolation were significantly associated with depressive symptoms for men but not women (Hodgetts et al., Citation2021). In contrast, over-identification was significantly associated with depressive symptoms for women but not men. Whether these findings apply to sexual minority adults is unknown. Further, whether gender moderates the associations between self-warmth and depressive symptoms and between self-coldness and depressive symptoms has yet to be investigated.

Few studies have examined whether self-compassion varies between people of different sexual orientations. In a study of sexual minority women, bisexual women scored significantly lower on self-compassion and mindfulness, and significantly higher on isolation and over-identification than lesbian women (Brown-Beresford & McLaren, Citation2022). This study also found that the relationship between self-compassion and depressive symptoms and between each of the six components and depressive symptoms were not moderated by the sexual orientation of the women. In a study of sexual minority men, no differences were found in self-warmth or self-coldness between bisexual and gay men (Ristvej et al., Citation2023). The relationships between self-warmth and depressive symptoms and self-coldness and depressive symptoms were not conditional on sexual orientation. The two studies show that the strength of the relationship between components of self-compassion and depressive symptoms is similar for monosexual and bisexual adults.

In summary, self-compassion has been widely researched for its protective role against depressive symptoms within the general population but has received relatively little attention in research among sexual minority adults. Furthermore, little research has examined how the components of self-warmth and self-coldness relate differently to depressive symptomology among sexual minority adults and whether those relations are moderated by gender and sexual orientation. To date, studies have investigated the moderating roles of gender and sexual orientation separately. Given gender and sexual orientation appear to interact to influence levels of depression (Ross et al., Citation2018), it is of value to investigate whether they also interact to influence the relationship between self-warmth and depressive symptoms and self-coldness and depressive symptoms. Incorporating gender and sexual orientation into one study allows exploration of their interaction.

Based on Shakeshaft and McLaren (Citation2022), we did not expect a main effect for gender, nor did we expect a main effect for sexual orientation, given the findings of Brown-Beresford and McLaren (Citation2022) and Ristvej et al. (Citation2023). However, given gender and sexual orientation appear to interact to influence depressive symptoms (Dulai & Schmidt, Citation2023; Ross et al., Citation2018), we anticipated their interaction would moderate the association between self-warmth and depressive symptoms and between self-coldness and depressive symptoms. Based on the findings of Ross et al. (Citation2018) and Dulai and Schmidt (Citation2023) for depression, we expected the association between self-warmth and depressive symptoms would be weakest for bisexual women and the association between self-coldness and depressive symptoms would be strongest for bisexual women.

Current study

This study aimed to investigate whether there are differences in self-warmth and self-coldness between bisexual and monosexual sexual minority men and women. It was hypothesized women would score higher on depressive symptoms and self-coldness and lower on self-warmth compared with men. It was hypothesized that bisexual adults would score higher on depressive symptoms and self-coldness and lower on self-warmth compared with monosexual adults. It was also expected bisexual women would score the highest on depressive symptoms and self-coldness and lowest on self-warmth compared to bisexual men, lesbian women, and gay men. It also explored whether self-warmth and self-coldness explained unique variance in depressive symptoms among sexual minority adults. It was hypothesized that only self-coldness would explain unique variance in depressive symptoms. Finally, the study investigated whether the associations between self-warmth and depressive symptoms and self-coldness and depressive symptoms were conditional on gender and sexual orientation. We anticipated the interaction between gender and sexual orientation would moderate the association between self-warmth and depressive symptoms and between self-coldness and depressive symptoms. We expected the association between self-warmth and depressive symptoms would be weakest for bisexual women and the association between self-coldness and depressive symptoms would be strongest for bisexual women.

Method

Participants

The study was open to cisgender and transgender individuals who identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual and were aged 18 years and older. Given bisexual adults can experience minority stress differently from other plurisexual people (e.g. pansexual, queer; Panas, Citation2017) we restricted the inclusion criteria to those who identified as bisexual. An international sample of 439 women aged 18 to 69 years (M = 30.21, SD = 10.70), and 391 men aged 18 to 71 years (M = 32.20, SD = 11.74) were recruited electronically through social media and online platforms such as Facebook and Reddit. Participants were not remunerated or compensated for their participation.

A total of 1111 eligible participants commenced the survey, with 830 completing the survey. The final sample of 830 participants came from 49 countries. Most participants resided in the United States of America (n = 428, 51.6%), Australia (n = 122, 14.7%), the United Kingdom (n = 72, 8.7%), Canada (n = 54, 6.5%), and Europe (n = 25, 3%). The demographic characteristics of the sample can be found in . The majority of participants were cisgender, White, had a university degree, and were employed. Less than half of the participants were in a relationship and had disclosed their sexual orientation to at least half of the people they knew.

Table 1. Frequency of Demographic Characteristics in Sample.

Measures

Participants completed demographic questions including sexual orientation, gender, relationship status, race/ethnicity, age, education, employment status, and level of disclosure of sexual orientation. Sexual orientation was self-reported by participants by selecting from a drop-down menu in the survey. There was also an option for participants to use a free-text box to describe their sexual orientation.

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (Radloff, Citation1977) is a 20-item self-report measure of depressive symptomology. Participants indicated how they felt during the preceding week using a 4-point Likert scale to indicate the number of days they had experienced the emotions or thoughts: 0 = rarely or none of the time (less than one day); 1 = some or a little of the time (1–2 days); 2 = occasionally or a moderate amount of time (3–4 days); 3 = most or all of the time (5–7 days). Scores range from zero to 60, with higher scores indicating higher levels of depressive symptomology. Scores of 16 or above suggest an individual is at risk of developing clinical depression (Radloff, Citation1977). The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale has shown excellent internal consistency within samples of sexual minority women and men (α = .91 and α = .92, respectively; McLaren, Citation2016). In the current sample, the Cronbach alpha coefficient was excellent (α = .91).

The Self-Compassion Scale (Neff, Citation2003a) is a 26-item self-report measure assessing six subscale factors of self-compassion: self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification (Neff, Citation2003b). Participants responded to each item using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = almost never to 5 = almost always. Mean item scores were calculated for self-warmth (consisting of self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness) and self-coldness (consisting of self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification). Higher scores indicate higher levels of self-warmth and self-coldness. Good internal consistency was demonstrated for self-warmth (α = .71) and self-coldness (α = .86) for a sample of sexual minority adults (Chong & Chan, Citation2023). In the current study, the Cronbach alpha coefficients for self-warmth (α = .91) and self-coldness (α = .92) were excellent.

Procedure

The research project was approved by Charles Sturt University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol number 23764). Participants read a Participant Information Statement and provided consent by clicking an “I consent” button. Data were collected using the QuestionPro© platform. Participants completed the demographic questions first. Participants then completed the Self-Compassion Scale and the Center for Epidemiological Depression Scale in randomized order to control for order effects. All items required an answer to progress forward. As part of the informed consent process, participants were advised that they could withdraw their consent at any time by closing the survey and their responses would not be used. Therefore, participants with a 100% completion rate were included in the study. Participation took approximately 10 minutes. The completion rate for the survey was 75% with 830 individuals completing all the items of the survey from 1111 eligible participants who commenced the survey.

Data analysis

Due to established relationships between sociodemographic variables and depressive symptoms among sexual minority adults, race/ethnicity (Bostwick et al., Citation2019), gender identity (Warren et al., Citation2016), age, relationship status, education, employment (Hanley & McLaren, Citation2014), and level of disclosure of sexual orientation (Schrimshaw et al., Citation2013) were controlled for in all analyses. Descriptive statistics were conducted to describe the characteristics of the sample. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to assess whether lesbian women, bisexual women, gay men, and bisexual men differed on the scores of all measures. Pearson bivariate correlations and partial correlations, controlling for sociodemographic variables, were conducted to investigate the relationships between all the variables of the study.

Multiple linear regression analysis tested whether self-warmth and self-coldness explained unique variance in depressive symptoms. The two moderated moderation models were tested using model 3 of the Hayes Process tool in SPSS (Hayes, Citation2018). In the models, depressive symptoms (dependent variable), self-warmth or self-coldness, gender (first moderator variable), sexual orientation (second moderator variable), and the covariates were entered. The confidence interval (CI) was set at 95% and the number of bootstrap samples was set at 10,000. The variables that define products were mean-centered for the construction of interaction terms. To determine if a moderated-moderation model was supported, an assessment of the confidence intervals was conducted, and significant interaction terms were determined when the confidence interval did not contain zero.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Less than half of lesbian women (n = 103, 47.2%) and gay men (n = 84, 43.1%) and just more than half of bisexual women (n = 124, 53.4%) and bisexual men (n = 114, 54.3%) had scores of 16 or higher on the Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale, indicating clinically significant levels of depressive symptoms. There was not a significant association between group membership (based on gender and sexual orientation) and reporting clinically significant levels of depressive symptoms, χ2 (3, N = 855) =7.02, p = .071.

The results of the univariate ANOVA can be seen in . The interaction between gender and sexual orientation was not significant for any of the variables. The main effect for gender was not significant in any analysis, however, the main effect for sexual orientation was significant in each analysis. Pairwise comparisons indicated that bisexual participants (M = 17.36) scored significantly higher than monosexual participants (M = 15.20) on depressive symptoms, F(1, 826) = 12.83, p < .001, η2 = .015. Bisexual participants (M = 2.88) scored significantly lower than monosexual participants (M = 3.02) on self-warmth, F(1, 826) = 6.19, p = .013, η2 = .007. Bisexual participants (M = 3.64) scored significantly higher than monosexual participants (M = 3.39) on self-coldness, F(1, 826) = 18.08, p < .001, η2 = .021. All effect sizes were small.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics and Results of ANOVA for Gender x Sexual Orientation Interaction.

The results of Pearson’s r and partial correlations are shown in . Higher levels of self-warmth were associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms. Higher levels of self-coldness were associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms.

Table 3. Correlations between Variables.

The results of the multiple linear regression analysis testing whether self-warmth and self-coldness predicted unique variance in depressive symptoms are presented in . Both self-warmth and self-coldness were significant predictors of depressive symptoms, however, self-coldness explained more unique variance (12%) than self-warmth (1%).

Table 4. Results of Regression Analysis Testing Self-Warmth and Self-Coldness as Predictors of Depressive Symptoms.

The results of the regression analysis testing whether gender and sexual orientation moderated the relation between self-warmth and depressive symptoms are shown in . The interaction between gender, sexual orientation, and self-warmth did not significantly predict depressive symptoms; the moderation model was not supported. None of the two-way interactions were significant. Higher levels of self-warmth, being partnered, having a higher level of education, and being employed were associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms.

Table 5. Results of Regression Analyses Testing Moderation Models for Self-warmth and Self-coldness.

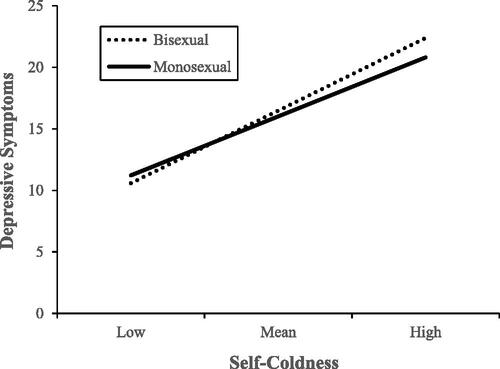

As shown in , the interaction between gender, sexual orientation, and self-coldness was not significant. The interaction between sexual orientation and self-coldness was significant. The interaction between sexual orientation and self-coldness is shown in . Higher levels of self-coldness were associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms for bisexual, B = 6.91, p < .001 [95% CI 6.12, 7.71], and monosexual, B = 5.62, p < .001 [95% CI 4.87, 6.36], participants, however, the association was stronger for bisexual participants. Lower levels of self-coldness, being partnered, having a higher level of education, and being employed were associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms.

Discussion

The current study aimed to investigate whether there are differences in self-warmth, self-coldness, and depressive symptoms between bisexual and monosexual sexual minority men and women. Results supported the hypothesis that bisexual adults would score significantly higher on depressive symptoms and self-coldness and significantly lower on self-warmth than monosexual adults. Results did not support the hypothesis that women would score higher on depressive symptoms and self-coldness and lower on self-warmth compared with men, or that bisexual women would score the highest on depressive symptoms and self-coldness and lowest on self-warmth compared to bisexual men, lesbian women, and gay men. Results did not support the hypothesis that only self-coldness would explain unique variance in depressive symptoms among sexual minority adults. Results indicated that both explained unique variance in depressive symptoms, however, self-coldness explained substantially more unique variance. The study also investigated whether the associations between self-warmth and depressive symptoms and self-coldness and depressive symptoms were moderated by the interaction between gender and sexual orientation. The hypothesis that these relationships would be moderated by the interaction between gender and sexual orientation was not supported. Inconsistent with our expectations, the relation between self-coldness and depressive symptoms was moderated by sexual orientation.

Group differences on self-warmth, self-coldness, and depressive symptoms

The findings that there were no significant gender differences in self-warmth and self-coldness are consistent with research among sexual minority adults using the total self-compassion score (Bell et al., Citation2018). The findings are inconsistent, however, with research showing that sexual minority women (Shakeshaft & McLaren, Citation2022) and women in community samples score higher on self-coldness (Lopez, Sanderman, Ranchor, et al., Citation2018) and lower on self-compassion (Yarnell et al., Citation2015) than men. The reason for the difference in findings between the two studies of sexual minority adults is unclear. The samples for the two studies were similar: both were international samples consisting of White, cisgender, unpartnered, tertiary-educated adults who were out to at least half the people they knew, so it is unlikely to be attributed to the characteristics of the participants. A possible explanation for the lack of gender differences in this study may be attributed to gender role orientation, a variable not assessed in this study. Yarnell et al. (Citation2019) investigated the association between gender role orientation and self-compassion among a sample of college students and a community sample. They found that masculine gender role orientation was more strongly related to self-compassion scores than self-identified gender identity. Further, participants who scored high on both femininity and masculinity tended to score highest on self-compassion. Given that sexual minority adults, and particularly women, are more likely to reject traditional gender roles than heterosexual adults (Kowalski & Scheitle, Citation2020), the gender differences seen in broader community samples may not apply to sexual minority adults. As gender role orientation was not assessed in this study nor in Shakeshaft and McLaren’s (Citation2022) study, we cannot determine whether this potentially explains the inconsistency in findings. It is suggested that future studies on self-warmth and self-coldness with sexual minority adults include a measure of gender role orientation to investigate whether that is associated with self-warmth and self-coldness rather than focusing on gender.

The finding indicating no gender difference in depressive symptoms is inconsistent with prior research which indicates sexual minority women experience more depressive symptoms than sexual minority men (Ferlatte et al., Citation2020). Also, the lack of support for an interaction between gender and sexual orientation is inconsistent with research showing that bisexual women experience greater mental health concerns than lesbian women, gay men, and bisexual men (Dulai & Schmidt, Citation2023). The lack of differences on depressive symptomology may be attributed to the method of recruitment and composition of the sample. The sole use of recruitment online from sites aimed at sexual minority adults is likely responsible for a sample who had disclosed their sexual orientation to others (particularly among monosexual participants), and were highly educated, cisgender, and White. Online media can empower sexual and gender minority people and through access to resources and community, it can buffer discrimination and loneliness (Craig et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, we did not examine other individual factors that help a person to cope with stress and adversity thus informing the level of resilience that may contribute to explaining why we did not find a gender difference in depressive symptoms (Meyer, Citation2015).

The findings indicated there were differences in self-warmth, self-coldness, and depressive symptoms based on sexual orientation. As expected, bisexual participants reported higher levels of depressive symptoms and self-coldness and lower levels of self-warmth compared with monosexual participants. These findings are consistent with a prior study that found bisexual women have lower levels of self-warmth and higher levels of self-coldness compared with lesbian women (Brown-Beresford & McLaren, Citation2022). However, in contrast, a prior study of sexual minority men found no differences in self-warmth or self-coldness between bisexual and gay men (Ristvej et al., Citation2023). The differences demonstrated in this study for self-warmth and self-coldness, along with the difference in depressive symptoms shown in this and other studies (Ross et al., Citation2018; Wittgens et al., Citation2022), can be explained by the additional stress, notably binegativity (Friedman et al., Citation2014), experienced by bisexual people. Bisexual individuals experience stigma from being plurisexual rather than monosexual, their sexual identity being seen as a phase (Dodge et al., Citation2016), being viewed as lacking the courage to identify as lesbian or gay, and attempting to maintain heterosexual privilege by not identifying as lesbian or gay (Israel & Mohr, Citation2004). These additional unique stressors likely impact how kind one can be to oneself in difficult times, resulting in bisexual adults having lower levels of self-warmth and higher levels of self-coldness, and subsequently higher levels of depressive symptoms, than monosexual adults.

Self-warmth, self-coldness, and depressive symptoms

The third aim investigated whether both self-coldness and self-warmth explained unique variance in depressive symptoms. Based on findings by Shakeshaft and McLaren (Citation2022) and Brown-Beresford and McLaren (Citation2022), it was expected that only self-coldness would explain unique variance. However, both self-warmth and self-coldness explained unique variance in depressive symptoms, with self-coldness explaining substantially more variance than self-warmth. This finding is consistent with a study with sexual minority men, that found both self-warmth and self-coldness explained unique variance in depressive symptoms, with self-coldness explaining substantially more unique variance (Ristvej et al., Citation2023). The key finding from this small body of research with sexual minority adults, in combination with studies in with other populations (López, Sanderman, & Schroevers, Citation2018; Lou et al., Citation2022; Muris & Petrocchi, Citation2017) is that self-coldness as a risk factor for depressive symptoms is more important than self-warmth as a protective factor.

Gender and sexual orientation as moderators

The final aim of the study was to build on previous studies that have examined gender and sexual orientation separately by investigating whether the interaction between gender and sexual orientation moderated the association between self-warmth and depressive symptoms and between self-coldness and depressive symptoms. Findings did not support the hypothesis that the relationship between self-warmth and depressive symptoms would be weakest for bisexual women and the relationship between self-coldness and depressive symptoms would be strongest for bisexual women. These findings contrast with research which showed gender and sexual orientation interact to influence depressive symptoms (Dulai & Schmidt, Citation2023; Ross et al., Citation2018). Rather than supporting the intersectionality of gender and sexual orientation, we found that only sexual orientation interacted with self-coldness to influence levels of depressive symptoms. Specifically, results indicated that the association between increasing levels of self-coldness and increasing levels of depressive symptoms was significantly stronger for bisexual adults than monosexual adults. It is likely the experience of the additional minority stress that stems from binegativity strengthens the association between self-coldness and depressive symptoms among bisexual adults. Elements of self-coldness, such as feeling isolated from humanity in one’s suffering, critical self-judgment, and over-identifying with one’s painful experiences (Neff, Citation2003a), are higher and more strongly linked to depressive symptoms for bisexual adults than for monosexual adults. These findings highlight the importance of self-coldness for the mental health of bisexual adults.

Limitations

The results of the current study should be interpreted considering some limitations. Whilst the study had a large sample, most participants were White and recruited from the United States and Australia from online LGBTIQA + communities. The impact of the recruitment method may limit the sample from being representative of bisexual and monosexual adults in the broader LGBTIQA + community. Research shows that sexual minority women who complete an online survey have higher levels of depressive symptoms than sexual minority women who complete a paper survey (McLaren & Castillo, Citation2020a, Citation2020b). To address this limitation, future research could benefit from participant recruitment strategies that have a broader participant reach to a more representative sample of sexual minority adults. Studies that use purposive sampling would allow the exploration of the intersectionality between race/ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation. The cross-sectional design of the study limits claims of causality. Future research which uses a longitudinal design is encouraged to overcome this limitation (O’Laughlin et al., Citation2018). A further limitation is common method variance (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003) due to the use of self-report measures collected at one time.

Implications and future directions

The clinically significant levels of depressive symptomatology observed among the sample reinforces the need to support the mental health of sexual minority adults. The results indicate that focusing on reducing self-coldness, rather than increasing self-warmth, may be beneficial for reducing depressive symptoms among sexual minority adults and particularly bisexual adults. There is initial evidence that therapies which focus on self-compassion (e.g., compassion-focused therapy and compassionate mindfulness training) are effective in increasing self-compassion (Beaumont et al., Citation2017) and reducing self-criticism (Beaumont et al., Citation2017; Gilbert & Procter, Citation2006) and depressive symptoms (Gilbert & Procter, Citation2006). There is a need to investigate whether such therapies designed for the general population are efficacious with sexual minority adults and whether the efficacy of interventions is similar for people of different genders and sexual orientations.

It has been proposed that compassion-focused therapy may be an efficacious intervention for sexual and gender minority people because of its focus on shame and self-criticism (Pepping et al., Citation2017; Petrocchi et al., Citation2016). Petrocchi et al. (Citation2016) describe the role of the threat and protection system in the development of self-blame and self-criticism and argue one of the main goals of compassion-focused therapy is to assist clients to recognize when they are in a mind-set which emphasizes the threat system. Awareness of this mindset enables clients to refocus and engage in strategies which activate self-compassion. This therapy is likely to be highly relevant to sexual minority adults because it can assist them to understand that their experiences of sexual minority stress, including heterosexism and binegativity, are not their fault. This understanding likely enables individuals to reduce self-criticism and engage with self-warmth strategies (Petrocchi et al., Citation2016). Although a protocol for a study aiming to investigate the efficacy of a compassion-focused therapy intervention with young sexual minority adults aged 18 to 25 years who are experiencing depressive symptoms has been published (Pepping et al., Citation2017), findings have not been published. Research examining the efficacy of compassion-focused therapy for sexual minority adults aged older than 25 years is warranted, as well as examining its efficacy for bisexual individuals specifically given their high levels of self-coldness and the strong association it has with depressive symptoms.

Future directions in research and clinical interventions can likely be informed by theoretical advances in resilience, approaches to stress and trauma, and minority stress relating to sexual minority adults. Resilience is known to arise in the face of stress and adversity and is an important factor in understanding minority stress (Meyer, Citation2015). A limitation in the minority stress pathway is the lack of consideration of self-compassion in the minority stress model. Whilst research indicates resilience-type factors and coping processes are protective against depressive symptoms and other adverse psychological health outcomes (Dev et al., Citation2020; Meyer, Citation2015), not all individuals have the same opportunity for resilience due to unequal social structures and differential exposure to heterosexism, abuse, discrimination, and rejection (de Lira & de Morais, Citation2017; Meyer, Citation2015). This is likely to be particularly true for bisexual individuals due to the additional minority stress they experience. Future research should continue to identify protective factors for sexual minority adults and consider extending the minority stress model to consider the role of self-compassion.

Concluding statement

The current study contributes to the research on self-compassion among sexual minority adults, as well as to the broader literature as this study is one of the few studies to investigate self-warmth and self-coldness as two separate factors of self-compassion, as opposed to self-compassion as a unitary construct. The findings highlight the importance of the relationship between self-coldness, rather than self-warmth, and depressive symptoms, especially for bisexual adults. Interventions such as compassion-focused therapy, that seek to reduce self-coldness will likely assist in reducing depressive symptoms among sexual minority adults, particularly bisexual adults.

Author contribution

Both authors: conceptualization. CS: data collection, writing-original draft preparation (Introduction, Method, Discussion) and editing. SMcL: data analysis and interpretation, writing-original draft preparation (Results), writing-reviewing and editing, critical revisions. Both authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research procedures were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at Charles Sturt University (protocol number 23764). Informed consent was provided by all participants.

Disclosure of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s)

Data availability statement

The data set analyzed for the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Beaumont, E., Rayner, G., Durkin, M., & Bowling, G. (2017). The effects of compassionate mind training on student psychotherapists. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 12(5), 300–312. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMHTEP-06-2016-0030

- Bell, K., Rieger, E., & Hirsch, J. K. (2018). Eating disorder symptoms and proneness in gay men, lesbian women, and transgender and gender non-conforming adults: Comparative levels and a proposed mediational model. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2692. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02692

- Bostwick, W. B., Hughes, T. L., Steffen, A., Veldhuis, C. B., & Wilsnack, S. C. (2019). Depression and victimization in a community sample of bisexual and lesbian women: An intersectional approach. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(1), 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1247-y

- Broderick, P. C. (1998). Early adolescent gender differences in the use of ruminative and distracting coping strategies. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 18(2), 173–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431698018002003

- Broderick, P. C., & Korteland, C. (2004). A prospective study of rumination and depression in early adolescence. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 9(3), 383–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104504043920

- Brooks, V. R. (1981). Minority stress and lesbian women. Lexington Books.

- Brown-Beresford, E., & McLaren, S. (2022). The relationship between self-compassion, internalized heterosexism, and depressive symptoms among bisexual and lesbian women. Journal of Bisexuality, 22(1), 90–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2021.2004483

- Chio, F. H. N., Mak, W. W. S., & Yu, B. C. L. (2021). Meta-analytic review on the differential effects of self-compassion components on well-being and psychological distress: The moderating role of dialecticism on self-compassion. Clinical Psychology Review, 85, 101986–101986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.101986

- Chong, E. S. K., & Chan, R. C. H. (2023). The role of self-compassion in minority stress processes and life satisfaction among sexual minorities in Hong Kong. Mindfulness, 14(4), 784–796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02106-7

- Cox, S. J., Mezulis, A. H., & Hyde, J. S. (2010). The influence of child gender role and maternal feedback to child stress on the emergence of the gender difference in depressive rumination in adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 46(4), 842–852. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019813

- Craig, S. L., McInroy, L., McCready, L. T., & Alaggia, R. (2015). Media: A catalyst for resilience in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth. Journal of LGBT youth, 12(3), 254–275.

- de Lira, A. N., & de Morais, N. A. (2017). Resilience in lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) populations: An Integrative literature review. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 15(3), 272–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-017-0285-x

- Dev, V., Fernando, A. T., 3rd., & Consedine, N. S. (2020). Self-compassion as a stress moderator: A cross-sectional study of 1700 doctors, nurses, and medical students. Mindfulness, 11(5), 1170–1181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01325-6

- DeVore, R., & Pritchard, M. E. (2013). Analysis of gender differences in self-statements and mood disorders. VISTAS: Effective counseling interventions, tools, and techniques.

- Dodge, B., Herbenick, D., Friedman, M. R., Schick, V., Fu, T.-C J., Bostwick, W., Bartelt, E., Muñoz-Laboy, M., Pletta, D., Reece, M., & Sandfort, T. G. M. (2016). Attitudes toward bisexual men and women among a nationally representative probability sample of adults in the United States. PloS One, 11(10), e0164430-e0164430. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0164430

- Dulai, J. J. S., & Schmidt, R. A. (2023). High prevalence of depression symptoms among bisexual women: The association of sexual orientation and gender on depression symptoms in a nationally representative U.S. sample. Journal of Bisexuality, 23(4), 403–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2023.2265353

- Ferlatte, O., Salway, T., Rice, S. M., Oliffe, J. L., Knight, R., & Ogrodniczuk, J. S. (2020). Inequities in depression within a population of sexual and gender minorities. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 29(5), 573–580. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2019.1581345

- Finlay-Jones’, A. L. (2017). The relevance of self-compassion as an intervention target in mood and anxiety disorders: A narrative review based on an emotion regulation framework. Clinical Psychologist, 21(2), 90–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/cp.12131

- Friedman, M. R., Dodge, B., Schick, V., Herbenick, D., Hubach, R., Bowling, J., Goncalves, G., Krier, S., & Reece, M. (2014). From bias to bisexual health disparities: Attitudes toward bisexual men and women in the United States. LGBT Health, 1(4), 309–318. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2014.0005

- Gilbert, P., & Procter, S. (2006). Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: Overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 13(6), 353–379. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.507

- Hanley, S., & McLaren, S. (2014). Sense of belonging to layers of lesbian community weakens the link between body image dissatisfaction and depressive symptoms. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 39(1), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684314522420

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Dovidio, J. (2009). How does stigma "get under the skin"? The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychological Science, 20(10), 1282–1289. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. (2nd. ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Hodgetts, J., McLaren, S., Bice, B., & Trezise, A. (2021). The relationships between self-compassion, rumination, and depressive symptoms among older adults: The moderating role of gender. Aging & Mental Health, 25(12), 2337–2346. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1824207

- Israel, T., & Mohr, J. J. (2004). Attitudes toward bisexual women and men: Current research, Future directions. Journal of Bisexuality, 4(1-2), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1300/J159v04n01_09

- Johnson, D. P., & Whisman, M. A. (2013). Gender differences in rumination: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(4), 367–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.03.019

- Körner, A., Coroiu, A., Copeland, L., Gomez-Garibello, C., Albani, C., Zenger, M., & Brähler, E. (2015). The role of self-compassion in buffering symptoms of depression in the general population. PloS One, 10(10), e0136598. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136598

- Kowalski, B. M., & Scheitle, C. P. (2020). Sexual identity and attitudes about gender roles. Sexuality & Culture, 24(3), 671–691. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-019-09655-x

- Lindquist, L. M., Livingston, N. A., Heck, N. C., & Machek, G. R. (2016). Predicting depressive symptoms at the intersection of attribution and minority stress theories. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 21(1), 32–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2016.1217498

- Lopez, A., Sanderman, R., Ranchor, A., & Schroevers, M. J. (2018). Compassion for others and self-compassion: Levels, correlates, and relationship with psychological well-being. Mindfulness, 9(1), 325–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0777-z

- López, A., Sanderman, R., & Schroevers, M. J. (2018). A close examination of the relationship between self-compassion and depressive symptoms. Mindfulness, 9(5), 1470–1478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0891-6

- Lou, X., Wang, H., & Minkov, M. (2022). The correlation between self-compassion and depression revisited: A three-level meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 13(9), 2128–2139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01958-9

- Loue, S., & Sajatovic, M. (2009). Determinants of minority mental health and wellness. Springer New York. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/csuau/detail.action?docID=417454

- Luyten, P., Sabbe, B., Blatt, S. J., Meganck, S., Jansen, B., De Grave, C., Maes, F., & Corveleyn, J. (2007). Dependency and self-criticism: Relationship with major depressive disorder, severity of depression, and clinical presentation. Depression and Anxiety, 24(8), 586–596. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20272

- Lyons, A. (2015). Resilience in lesbians and gay men: A review and key findings from a nationwide Australian survey. International Review of Psychiatry (Abingdon, England), 27(5), 435–443. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2015.1051517

- Matos, M., Carvalho, S. A., Cunha, M., Galhardo, A., & Sepodes, C. (2017). Psychological flexibility and self-compassion in gay and heterosexual men: How they relate to childhood memories, shame, and depressive symptoms. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 11(2), 88–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2017.1310007

- McLaren, S. (2016). The interrelations between internalized homophobia, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among Australian gay men, lesbians, and bisexual women. Journal of Homosexuality, 63(2), 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2015.1083779

- McLaren, S., & Castillo, P. (2020a). What about me? Sense of belonging and depressive symptoms among bisexual women. Journal of Bisexuality, 20(2), 166–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2020.1759174

- McLaren, S., & Castillo, P. (2020b). The relationship between a sense of belonging to the LGBTIQ + community, internalized heterosexism, and depressive symptoms among bisexual and lesbian women. Journal of Bisexuality, 21(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2020.1862726

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Meyer, I. H. (2015). Resilience in the study of minority stress and health of sexual and gender minorities. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(3), 209–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000132

- Muris, P., & Petrocchi, N. (2017). Protection or vulnerability? A meta-analysis of the relations between the positive and negative components of self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(2), 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2005

- Neff, K. (2003b). Self-Compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032

- Neff, K. D. (2003a). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027

- Neff, K. D., Kirkpatrick, K. L., & Rude, S. S. (2007). Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(1), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.03.004

- Neff, K. D., & McGehee, P. (2010). Self-compassion and psychological resilience among adolescents and young adults. Self and Identity, 9(3), 225–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860902979307

- O’Laughlin, K. D., Martin, M. J., & Ferrer, E. (2018). Cross-sectional analysis of longitudinal mediation processes. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 53(3), 375–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2018.1454822

- Pachankis, J. E. (2007). The psychological implications of concealing a stigma: A cognitive-affective-behavioral model. Psychological Bulletin, 133(2), 328–345. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.328

- Pachankis, J. E., Mahon, C. P., Jackson, S. D., Fetzner, B. K., & Bränström, R. (2020). Sexual orientation concealment and mental health: A conceptual and meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 146(10), 831–871. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000271

- Panas, K. (2017). Sexual identity, social support and mental health: A comparison between individuals with diverse plurisexual identities in Texas. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Pepping, C., Lyons, A., McNair, R., Kirby, J., Petrocchi, N., & Gilbert, P. (2017). A tailored compassion-focused therapy program for sexual minority young adults with depressive symotomatology: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychology, 5(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-017-0175-2

- Petrocchi, N., Matos, M., Carvalho, S., & Baiocco, R. (2016). Compassion-focused therapy in the treatment of shame-based difficulties in gender and sexual minorities. Mindfulness and acceptance for gender and sexual minorities. (1st Edition), 69–86.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306

- Ristvej, A. J., McLaren, S., & Goldie, P. D. (2023). The relations between self-warmth, self-coldness, internalized heterosexism, and depressive symptoms among sexual minority men: A moderated-mediation model. Journal of Homosexuality, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2023.2245523

- Ross, L. E., Salway, T., Tarasoff, L. A., MacKay, J. M., Hawkins, B. W., & Fehr, C. P. (2018). Prevalence of depression and anxiety among bisexual people compared to gay, lesbian, and heterosexual individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sex Research, 55(4-5), 435–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1387755

- Schrimshaw, E. W., Siegel, K., Downing, M. J., & Parsons, J. T. (2013). Disclosure and concealment of sexual orientation and the mental health of non-gay-identified, behaviorally bisexual men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(1), 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031272

- Shakeshaft, R., & McLaren, S. (2022). The relations between the positive and negative components of self-compassion and depressive symptoms among sexual minority women and men. Mindfulness, 13(1), 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-021-01696-4

- Trompetter, H. R., de Kleine, E., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2017). Why does positive mental health buffer against psychopathology? An exploratory study on self-compassion as a resilience mechanism and adaptive emotion regulation strategy. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 41(3), 459–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-016-9774-0

- Warren, J. C., Smalley, K. B., & Barefoot, K. N. (2016). Psychological well-being among transgender and genderqueer individuals. International Journal of Transgenderism, 17(3-4), 114–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2016.1216344

- Wilson, A. C., Mackintosh, K., Power, K., & Chan, S. W. Y. (2018). Effectiveness of self-compassion related therapies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 10(6), 979–995. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-1037-6

- Wittgens, C., Fischer, M. M., Buspavanich, P., Theobald, S., Schweizer, K., & Trautmann, S. (2022). Mental health in people with minority sexual orientations: A meta-analysis of population-based studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 145(4), 357–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13405

- World Health Organisation. (2020). Depression fact sheet. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression

- Yarnell, L. M., Neff, K. D., Davidson, O. A., & Mullarkey, M. (2019). Gender differences in self-compassion: Examining the role of gender role orientation. Mindfulness, 10(6), 1136–1152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-1066-1

- Yarnell, L. M., Stafford, R. E., Neff, K. D., Reilly, E. D., Knox, M. C., & Mullarkey, M. (2015). Meta-analysis of gender differences in self-compassion. Self and Identity, 14(5), 499–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2015.1029966