Abstract

Objective

This longitudinal cohort study aims to investigate the relationship between self-reported childhood maltreatment (CM) and the retrospective trajectory of substance use, mental health, and satisfaction with life in individuals with substance use disorders.

Methods

One hundred eleven treatment-seeking individuals with substance use disorder were recruited from clinical settings and monitored prospectively for 6 years. The participants’ substance use, mental health, and satisfaction with life were assessed using standardized measures. Cluster analysis divided the cohort into two groups—low CM and high CM—based on their scores on the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Short Form at year 6. Mixed-effects linear models were fitted to assess the association between longitudinal scores on drug use, mental health, and satisfaction with life and CM group.

Results

Most participants (92%) reported at least 1 CM. Out of all participants, 36% were categorized into the high-CM group, while 59% were categorized into the low-CM group. CM group was not associated with the amount of substance or alcohol use. CM group was significantly associated with the longitudinal course of mental health and life satisfaction.

Conclusions

This study underscores the association between self-reported CM and mental health and life satisfaction in patients with substance use disorder. Our results may imply an increased risk of adverse outcomes in patients with high levels of CM, while bearing in mind that both current and retrospective mental health and substance use problems can influence the accuracy of recalling CM.

Substance use disorders are a pressing public health problem causing considerable personal suffering, morbidity, and mortality as well as presenting an economic and societal burden, with annual global deaths estimated to be around half a million (World Health Organization, Citation2019). Clinically, substance use disorders often present alongside significant mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression (Couwenbergh et al., Citation2006). Comorbid mental health problems contribute to higher risk of relapse and adverse treatment results (Farley et al., Citation2004; Rowe et al., Citation2004). While comorbid mental distress decreases during the first 3 months of recovery from substance use disorder (Erga et al., Citation2020), identifying patients with persistent psychopathological symptoms is crucial when designing personalized substance use disorder treatment.

Adverse childhood experiences are highly prevalent among people with substance use disorder, as compared to the general population (Leza et al., Citation2021; Tang et al., Citation2021), and some authors have found adverse childhood experiences to be an important risk factor for later development of substance use disorder (Capusan et al., Citation2021; Martin et al., Citation2023; Rajapaksha et al., Citation2022; Ruberu et al., Citation2023). More severe forms of childhood maltreatment (CM), including emotional and physical neglect or abuse as well as sexual abuse are prevalent in 31% to 38% of people with substance use disorder (Zhang et al., Citation2020); rates are even higher in some patient cohorts, such as women with opioid use disorder (Santo et al., Citation2021).

Trauma in substance use disorder has been linked to higher levels of anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms (Borgert et al., Citation2023). Compared to patients with mild to moderate mental health disorders, patients with substance use disorder report multiple experiences of CM and higher levels of mental distress (Rasmussen et al., Citation2018). Neuroimaging studies have associated CM with both structural and functional changes in pathways related to stress as well as addiction, including brain regions related to craving and drug-seeking or relapse behavior (McLaughlin et al., Citation2019; Sahani et al., Citation2022).

Despite the well-established association between CM and increased risk of future mental health problems (Copeland et al., Citation2018; Dube et al., Citation2003), the clinical implications of these findings are less certain. National treatment recommendations often emphasize the importance of assessing trauma and CM during treatment (ASAM, Citation2020; Clinical Guidelines on Drug Misuse & Dependence Update Citation2017 Independent Expert Working Group, 2017; Helsedirektoratet, Citation2017). The emergence of evidence-based, trauma-focused treatment for substance use disorder with posttraumatic symptoms (Roberts et al., Citation2022) presents hope for identification of patients with a history of CM, with regard to both prevention and treatment of substance use disorder (Gerhardt et al., Citation2022; Sanchez & Amaro, Citation2022), and makes their identification all the more important.

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) has proven useful in both clinical practice and research (Bernstein et al., Citation2003; Thombs et al., Citation2007). However, assessing CM using retrospective self-report measures also entails significant challenges (Baldwin et al., Citation2019; Capusan et al., Citation2021; Löfberg et al., Citation2023). One challenge is the generally low agreement between prospectively and retrospectively recorded CM, where psychological distress and life stressors are associated with increased likelihood of reporting novel CM experiences (Colman et al., Citation2016). This potential bias is crucial for the validity of CM reports in research and highlights a risk of false positives in clinical settings. Data from CM assessment tools in patients with high levels of psychological distress should thus potentially be interpreted conservatively and with care. However, implementing this recommendation poses practical challenges, especially during the long-term follow-up of patients with substance use disorders. Long-term clinical recovery from substance use disorder is often defined by a significant reduction or stabilization of several symptom clusters, including substance use disorder symptoms, mental health, and improvements in life satisfaction (Bjornestad et al., Citation2020). Life satisfaction is of particular relevance, as it encompasses both clinical and non-clinical outcomes, including mental and social functioning, a sense of belonging, resilience, and social support (Cao & Zhou, Citation2021).

Against this backdrop, this study aims to investigate whether long-term outcomes of patients with substance use disorder are associated with the severity and frequency of retrospectively reported CM at 6-year follow-up. We put forth the following hypotheses:

Drug use is associated with the severity and frequency of self-reported CM at 6 years of follow-up.

The trajectories of mental distress over 6 years are associated with the severity and frequency of self-reported CM.

Life satisfaction over 6 years is associated with the severity and frequency of self-reported CM.

Method study design

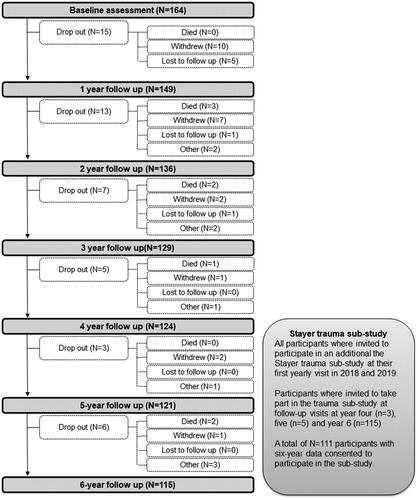

This study uses data from the first 6 years of the Stavanger Study of Trajectories of Addiction (the Stayer study) and a substudy on traumatic experiences in the Stayer cohort (Belfrage et al., Citation2023; Hagen et al., Citation2016; see a flowchart of the study in ).

The Norwegian Stayer study

The Norwegian Stayer study is a 10-year prospective cohort study of the course of neurocognitive, psychological, and social recovery processes in treatment-seeking patients with substance use disorder (Hagen et al., Citation2016; Svendsen et al., Citation2017). It comprises 208 treatment-seeking participants recruited in the years 2012 through 2015 from both inpatient and outpatient treatment in the Stavanger University Hospital catchment area. Stayer used clinical staff–assisted convenience sampling among patients starting a new treatment sequence in specialized substance use disorder treatment. The Stayer study was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee (REK 2011/1877).

Stayer study inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) ability to provide written informed consent; (b) a substance use disorder entitling the person to specialized treatment in the Stavanger University Hospital catchment area; (c) initiating a course of treatment within the substance use disorder treatment services; (d) age older than 16 years. In line with the high dropout and relapse rates of this patient group (Lappan et al., Citation2020), many participants had previously initiated such treatment sequences (for more information about the Norwegian specialized treatment for addiction, see Andersson et al., Citation2019).

The Stayer trauma substudy

In 2018, we included additional measures in the Stayer study (Belfrage et al., Citation2023), inviting all remaining participants in the Stayer study (N = 129, of whom 113 accepted) to provide data on trauma experiences in addition to the standard examination schedule. This additional data collection was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee (REK 2018/1528).

Participants

Of the 208 participants in the Stayer cohort, 44 patients were excluded from this study due to mono-substance use (e.g., only alcohol or cannabis) or a non–drug-related addiction (e.g., gambling disorder), leaving 164 participants qualified to participate in this study. Over 6 years, 49 individuals (29.9%) in the cohort dropped out (see details in ), leaving 115 eligible for this study. Of these, 111 participants consented to provide trauma data at the 6-year visit. Thus, a total of 111 participants were included in this study.

Procedures

Research assistants performed all participant assessments, including neurocognitive tests, administration of psychological self-report measures, and a semi-structured interview collecting information about demographics and social functioning.

Baseline assessment took place 2 weeks after the initiation of a new treatment sequence and secession from drug use, and the assessment battery was repeated annually for 6 years. We implemented a range of strategies to limit rate of attrition, including (a) organizational strategies, like strategic community involvement, flexibility in practical arrangements, and use of reminders, and (b) motivational strategies, including an annual lunch for participants, financial incentives, and reimbursement of transportation costs. For an exhaustive presentation of all implemented strategies, please refer to Svendsen et al. (Citation2017).

Procedures for the Stayer trauma substudy

Data on trauma were gathered in conjunction with a standard annual assessment, in the years 2018 through 2020. As a precaution in case of adverse reactions to filling in the trauma questionnaire, participants were provided with emergency contact information in case of a mental health emergency.

Assessment

The Norwegian version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire short form (CTQ-SF) was used to retrospectively assess CM (Bernstein et al., Citation2003; Bernstein & Fink, Citation1998; Dovran et al., Citation2013). The CTQ-SF is a 28-item self-report scale, assessing five dimensions of CM: childhood physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect. All items begin with the phrase “When I was growing up …” and are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = never true to 5 = very often true, where a higher score indicates more frequent maltreatment. Five subscale dimensions denoting types of maltreatment each comprise 5 items, with an additional 3 items measuring minimizing/denial (MD). The CTQ-SF has demonstrated high internal consistency (reliability) and convergent validity (Cruz, Citation2023). The factor structure of CTQ-SF has been replicated and demonstrated invariability to demographic factors (Cruz, Citation2023).

In addition to the continuous CTQ-SF scores, the frequency of CM was assessed using a two-stage approach. First, we dichotomized each of the five CTQ-SF dimensions into severe and non-severe, using the cutoff proposed by the original authors (Bernstein & Fink, Citation1998). These cutoff scores were ≥13 for emotional abuse, ≥10 for physical abuse, ≥8 for sexual abuse, ≥15 for emotional neglect, and ≥10 for physical neglect. The dichotomized dimension scores were used to create a continuous variable ranging from 0 to 5, where a score of 5 indicates severe maltreatment on all dimensions of the CTQ. For the MD subscale, we used an item-by-item cutoff of 5 as an indication of “MD positivity,” yielding a scale ranging from 0 to 3, in line with previous research (MacDonald et al., Citation2016).

Drug use was measured using the consumption items from the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT-C) and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C; Berman et al., Citation2005, Citation2007). Both the AUDIT and DUDIT are considered valid and reliable screening instruments for drug and alcohol use among patients with substance use disorder (Källmén et al., Citation2019; Voluse et al., Citation2012). For DUDIT-C, a cutoff of >1 was used to indicate current substance use. For the AUDIT-C, a cutoff of >5 was used to indicate problematic alcohol use. This higher cutoff has previously been used to identify unhealthy alcohol use in at-risk populations, aiming to limiting false positives (Erga et al., Citation2020; Rubinsky et al., Citation2013; Williams et al., Citation2014).

Mental distress was measured using the Symptoms Checklist 90–Revised (SCL-90-R), a 90-item self-report questionnaire commonly used in addiction research (Derogatis, Citation1994; Engel et al., Citation2016; López-Goñi et al., Citation2012; Rasmussen et al., Citation2018). The SCL-90-R is scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = not at all to 4 = severe, yielding a measure of mental health across nine dimensions. Due to its superior psychometric properties (concurrent validity and reliability), we used the Global Severity Index (GSI), that is, the mean SCL-90-R score, as a mental distress indicator (Bergly et al., Citation2013; Carrozzino et al., Citation2023).

We measured life satisfaction using the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., Citation1985), a self-report questionnaire comprising 5 items measuring subjective global life satisfaction. The SWLS has demonstrated good psychometric properties (Clench-Aas et al., Citation2011; Pavot & Diener, Citation2008).

Statistics

All statistical analyses were done using R Project for statistical computing version 4.2.3, with a p value < .05 deemed statistically significant. We did no correcting for multiple hypothesis testing.

The 28 CTQ-SF-questionnaire scores were used to split the participants into groups using k-means clustering method. Items #2, #5, #7, #13, #19, #26, and #28 were reversed before being included in the clustering analysis. Three items (#10, #16, and #22) from the MD subscale were omitted from the clustering procedure. The optimal number of two clusters was determined by silhouette analysis, thus splitting participants into more traumatized and less traumatized. We used Chi-square analysis to assess between-group differences in the frequency of caseness on the CTQ-SF sexual abuse subscale.

We used mixed-effects linear models to compare CM groups for drug use (DUDIT-C score), alcohol use (AUDIT-C score), SWLS, and GSI. For drug and alcohol use outcomes, the distributional assumptions were a zero-inflated Poisson model, while for SWLS and GSI outcomes we assumed normal distribution. Differences between the trauma severity groups were assessed by including the trauma severity group as the main effect. All models were adjusted for age and gender, except for the model for alcohol outcome where age was removed from the main effects due to numerical issues. Patient IDs were the random effects (intercepts). The zero-inflated parts of the drug use and alcohol use assumed that the chance of staying sober depended on trauma severity group only. Time was initially modeled using cubic polynomial terms, and the higher-order polynomial terms were removed if not statistically significant.

As an additional analysis, we ran mixed-effects linear models with DUDIT-C score serving as the outcome variable and each of the six subscales as predictors. Again, we assumed a zero-inflated Poisson distribution. Conditional parts of the models were adjusted for age and gender, while the zero-inflated parts depended on the corresponding subscale score only. Again, patient IDs were the random effects (intercepts).

Missing data points

A portion of the data exhibits missing values, with 11.7% of the DUDIT data missing at year 6. The missing values encompass both intermittent periods, where participants temporarily left the study but later returned, and instances of complete withdrawal.

Mixed-effects model analysis assumes a missing-at-random mechanism, which is reasonable when retention and dropout can be predicted by observed variables. Survival analysis using proportional risk models with recurrent events concluded that an increase in DUDIT was associated with an increased likelihood of a missing DUDIT score at the next time point (hazard ratio, 1.06; 95% confidence interval [CI; 106, 1.07]; p = .001). However, some patients remained drug-free both before and after the period of missing measurements (12% of all cases). It could be hypothesized that the missing, unobserved data continue to follow the trend started prior to the period of missingness, but this assumption can be neither confirmed nor rejected. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine how the model parameter estimates change if the missing DUDIT scores were imputed using the last-observation-carried-forward method. The estimates are presented in Supplementary Table E-1. All the effects have similar directions and effect sizes.

Results

Baseline characteristics for the 111 included participants are listed in . In short, our cohort was predominantly male and had a mean age of 27 years. The level of education was generally dominated by lower secondary school (58.6%). The mean debut age of substance use was 13 years, and 57.7% of the cohort had intravenous substance use.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Included Participants

Frequency of CM

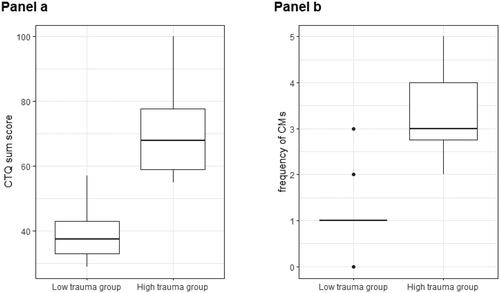

On overview of scores on the CTQ-SF and its subscales are presented in . A total of 92.8% of participants responded positively to at least one CM (median = 1, range 0–5). Sexual abuse (57.7%) and emotional abuse (40.5%) were the most frequently reported types of CM in the cohort. Cluster analysis allowed us to split the participants into two groups: (1) low trauma (n = 66) and (2) high trauma (n = 40). Due to single missing items on the CTQ-SF, clustering was only performed on with 106 participants. The distribution of CTQ scores and frequency of trauma for these groups are presented in .

Figure 2. Box plot of CTQ-SF sum scores (panel A) and number of trauma types (panel B) for participants by group.

CM = childhood maltreatment; CTQ-SF = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Short Form.

Table 2. Distribution of CTQ-SF Scores and Frequency of Scores Above Cutoff

contains a more detailed presentation of CTQ-SF and subscale scores as well as frequencies of scores above cutoff. The correlation matrix between CTQ-SF subscales is available in Supplementary Figure E-2. Except for the sexual abuse subscale, the high-trauma group had higher scores on all CTQ-SF subscales and more frequently scored above the cutoff. For the sexual abuse subscale, scores above cutoff were significantly more frequent in the low-trauma group compared to the high-trauma group. The groups did not differ in gender distribution, age, or SCL-90-R score at baseline, while baseline scores on the SWLS differed (with a median score of 16.0 [IQR, 13.0–22.8] in the low-trauma group versus a median score of 13.5 [IQR, 10.0–17.0] in the high-trauma group, p = .026).

Table 3. Demographic and CTQ-SF Scores and Frequency of Scores Above Cutoff, by Group

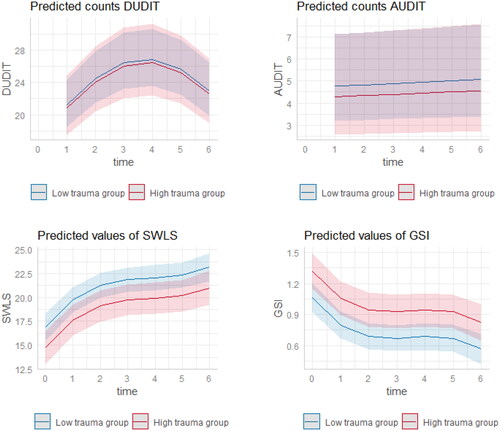

Mixed model analyses revealed no difference in the amount of substance or alcohol use between the groups (p = .886 and p = .742, respectively). Although individuals with severe trauma had a lower chance of staying sober, this association was not significant (odds ratio [OR] = 0.62; 95% CI [0.39, 1.01] p = .056). SWLS scores showed a significant trend of being lower for the participants with severe trauma (β = −2.15; 95% CI [−4.12, −0.17] p = .033). Participants in the high-trauma group had significantly higher SCL-90-R GSI raw scores (β = 0.26; 95% CI [0.06, 0.46] p = .011). Predicted marginal means for the two groups are presented in .

Figure 3. Predicted marginal means for DUDIT-C, AUDIT-C, SWLS, and SCL-90-R GSI raw scores, by group.

DUDIT-C = Drug Use Disorders Identification Test, consumption items; AUDIT-C = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, consumption items; SWLS = Satisfaction With Life Scale; GSI = Symptoms Checklist 90 Revised–Global Severity Index.

Note. For the substance scores, only the conditional parts of the models are presented.

Drug use by trauma subscale

A higher CTQ-SF sexual abuse score was associated with higher substance use during relapse episodes (β = 1.02; 95% CI [1.00, 1.04] p = .018), while higher CTQ-SF MD scores appeared to be associated with a lower chance of staying sober (OR = 0.82; 95% CI [0.69, 0.99] p = .042). Estimates for all subscales can be found in .

Table 4. Estimates of Mixed Models with Trauma Subscales Serving as Predictors and DUDIT-C Score as the Outcome Variable

Discussion

The influence of trauma on the course of recovery is intricate, and our findings highlight this. Consistent with prior reports, we observed a high prevalence of CM within our cohort. Our data indicate that a higher frequency and greater severity of self-reported CM are both associated with unfavorable trajectories of drug use and mental health over time. However, CM did not appear associated with the course of life satisfaction. This underscores the multifaceted nature of substance use disorder, its recovery process, and the potentially diverse impact of trauma in this context.

The relationship between retrospectively self-reported CM and current mental health has been a focal point in trauma research in recent years. Observations indicate that reports of CM, when retrospectively assessed through self-report, are susceptible to various biases, which can limit their validity and clinical relevance (Baldwin et al., Citation2019; Colman et al., Citation2016; Löfberg et al., Citation2023). Our findings indicate an association between higher frequencies and increased severity of CM and a greater prevalence of mental health problems and adverse clinical outcomes. However, it is crucial to acknowledge the retrospective nature of the CM data, preventing definitive conclusions about the direction of causality. This association is observed both cross-sectionally, at the time of CM measurement, and longitudinal in the 6 years prior to the measurement of CM. While not fully addressing the methodological issues associated with retrospective self-report, these findings can be interpreted as an indication that patients with multiple and severe experiences of CM also have greater challenges in coping with substance use disorder symptoms and mental health issues. This might be especially pronounced in patients reporting sexual abuse, as seen in our data. This interpretation is supported by findings suggesting that severity of PTSD symptoms mediates the course of substance use disorder over time (Hien et al., Citation2010).

We divided participants into two groups based on the frequency and severity of self-reported CM. The high-CM group, comprising individuals who reported multiple types of CM, displayed notably higher CTQ-SF mean scores than the low-CM group. In contrast, the low-CM group typically reported only one experience of CM and significantly lower CTQ-SF scores. The two groups are generally similar with regard to their baseline clinical characteristics and only differ in their degree of life satisfaction at the start of the study. In clinical practice, both of these groups would typically have positive screening results for CMs when assessed using a brief screening tool. However, our findings reveal that the two groups demonstrated significantly different trajectories in terms of mental health and life satisfaction and a tendency to have a higher risk of relapse during the 6 years leading up to the assessment of CMs. This distinction underscores the importance of considering not only the presence of CM but also its frequency and severity when examining the influence of CM on the course of mental health and risk of relapse in substance use disorder. Future studies should consider whether the original CTQ cutoffs are optimal for the population with substance use disorder, as variations in the nature of trauma experiences and their impact on clinical outcomes may necessitate tailored criteria for this specific cohort.

According to our data, sexual trauma seems to be a distinct subtype of CM. Notably, sexual trauma deviates from the high correlations observed among other CTQ-SF subscales. This was observed in both CM groups, where sexual trauma was evenly distributed between men and women. While our data do not allow for specific interpretations of this observation, we propose a contextual hypothesis. Emotional and physical abuse/neglect primarily relate to the family context, whereas sexual trauma could extend beyond family settings. Thus, the high-CM group may experience more chronic and long-lasting experiences of CM. Importantly, in the population with substance use disorder, factors such as engaging in sex work and participating in risky sexual encounters due to intoxication or self-injury may contribute to the significance of sexual trauma. Unfortunately, our data are not suited to test this hypothesis. However, as indicated in our results, the severity of sexual trauma seems to have a significant impact on drug use during relapse episodes. In our model, an increase of 10 units on the CTQ-SF sexual trauma subscale is associated with a 19.8% increase in the expected DUDIT-C score during drug use episodes. Therefore, a continued care approach (Chi et al., Citation2011) involving ongoing monitoring of patients over time in specialized and general healthcare settings, with easy access to detoxification and other inpatient treatment options, should be considered for individuals with a severe history of sexual trauma.

While life satisfaction is generally low in the entire sample when compared to data from a nationally representative sample (Clench-Aas et al., Citation2011), our data also suggest that rates of recovery of life satisfaction were associated with CM frequency and severity. A comparable dose-dependent relationship between childhood trauma and life satisfaction has been observed in the general population (Berhe et al., Citation2023; McKay et al., Citation2021). In our data, both groups have an increase in life satisfaction over time, but scores remain lower than in the general population over the entire observation period. Several factors may explain this observation. Life satisfaction in individuals with substance use disorder is not solely influenced by their history and mental health; social factors and physical health also play integral roles. Hence, we might anticipate longer recovery trajectories for life satisfaction, when compared to other outcomes such as mental health. Qualitative data indicate that recovery from substance use disorder often entails the process of restoring a meaningful sense of belonging to one’s community (Bjornestad et al., Citation2020), which takes time and is mediated by social structures (Robertson et al., Citation2021; Svendsen et al., Citation2020; Vigdal et al., Citation2023).

Finally, our findings suggest a relationship between high levels of reported CM and adverse clinical trajectories. Although we cannot fully disentangle this complex relationship in our data, clinically speaking, these findings underscore the crucial need for an integrative approach encompassing trauma-informed care, evidence-based therapies for trauma, and concurrent treatment for substance use disorders and mental health disorders in order to optimize outcomes (Amaro et al., Citation2007; Godley et al., Citation2014; van Dam et al., Citation2013). Current trials are also exploring the potential for integrated therapeutic strategies, such as eye movement desensitization and reprocessing in the INTACT trial, to concurrently address substance use disorder symptomatology and mental heath disorders following traumatic experiences (Abel, Citation2023).

Strengths and limitations

The major strengths of this study include the extended follow-up period, a multi-site recruitment strategy, repeated measures of outcomes over time, and our use of validated scales to assess mental health outcomes, life satisfaction, and CM. Nevertheless, the study has certain limitations. First, data on CM were gathered at a 6-year follow-up visit rather than at baseline. The CTQ-SF, a retrospective self-report measure, may be prone to recall biases and other methodological issues associated with retrospective reporting. In order to address this, we have attempted to interpret our findings while considering these methodological challenges. A second limitation is the lack of specific information on treatment, for example, treatment protocols. While all participants in this study engaged in a new treatment sequence at baseline, the length and nature of this treatment are unknown, which might bias our results. The association between psychological distress and CM group could be influenced by factors not measured in this study, such as treatment dropout, variations in treatment among providers, and readmission to treatment over the 6-year follow-up period. A third potential limitation is the measure of life satisfaction. In our study, we used a global measurement of life satisfaction by implementing the SWLS. While investigating domain-specific life satisfaction might have yielded different results, studies have shown that global and domain-specific measures of subjective well-being assess the same underlying construct (Wu & Yao, Citation2007). Fourth, our cohort comprised patients using multiple drugs. While this is the most common presentation of substance use disorder in clinical practice, our findings may not be generalizable to clinical cohorts with mono-substance use. Fifth, it is worth noting that our study’s use of a convenience sample could be viewed as a potential limitation. Last, our sample is limited in size and heterogenous, which might increase the risk of type II errors.

Author contributions

AHE contributed to study concept and design, data curation, analysis, interpretation of data, project leadership, and writing of the first draft. AU contributed to data curation, data analysis, visualization, interpretation of data, and writing of the second draft. ME contributed to initial analysis, interpretation of data, and writing of the first draft. ECF contributed to interpretation of data and writing of the first and second draft. AB contributed to formulation of the study protocol for the trauma data, interpretation of data, and writing of the first and second draft. All coauthors made critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (55.6 KB)Acknowledgements

We extend our sincere gratitude to the participants in our study and the staff of the participating clinical services, the KORFOR staff and, in particular, Thomas Solgård Svendsen, Anne-Lill Mjølhus Njaa, and Janne Aarstad, who collected all the initial and follow-up data. We also extend our gratitude to Jodi Maple Grødem and Liss Gøril Anda-Ågotnes for their feedback on the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no competing interests.

Data availability statement

Anonymized data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abel, K. (2023). Integrated trauma and addiction treatment - INTACT. Retrieved October 31, 2023, from https://www.oslo-universitetssykehus.no/fag-og-forskning/forskning/forskningsmiljoer/rusforsk/intact

- Amaro, H., Chernoff, M., Brown, V., Arévalo, S., & Gatz, M. (2007). Does integrated trauma-informed substance abuse treatment increase treatment retention? Journal of Community Psychology, 35(7), 845–862. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20185

- Andersson, H. W., Wenaas, M., & Nordfjærn, T. (2019). Relapse after inpatient substance use treatment: A prospective cohort study among users of illicit substances. Addictive Behaviors, 90, 222–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.11.008

- ASAM. (2020). The ASAM national practice guideline for the treatment of opioid use disorder: 2020 focused update.

- Baldwin, J. R., Reuben, A., Newbury, J. B., & Danese, A. (2019). Agreement between prospective and retrospective measures of childhood maltreatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(6), 584–593. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0097

- Belfrage, A., Mjølhus Njå, A. L., Lunde, S., Årstad, J., Fodstad, E. C., Lid, T. G., & Erga, A. H. (2023). Traumatic experiences and PTSD symptoms in substance use disorder: A comparison of recovered versus current users. Nordisk Alkohol- & Narkotikatidskrift: NAT, 40(1), 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/14550725221122222

- Bergly, T. H., Nordfjærn, T., & Hagen, R. (2013). The dimensional structure of SCL-90-R in a sample of patients with substance use disorder. Journal of Substance Use, 19(3), 257–261. https://doi.org/10.3109/14659891.2013.790494

- Berhe, O., Moessnang, C., Reichert, M., Ma, R., Hoflich, A., Tesarz, J., Heim, C. M., Ebner-Priemer, U., Meyer-Lindenberg, A., & Tost, H. (2023). Dose-dependent changes in real-life affective well-being in healthy community-based individuals with mild to moderate childhood trauma exposure. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotional Dysregulation, 10(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-023-00220-5

- Berman, A. H., Bergman, H., Palmstierna, T., & Schlyter, F. (2005). Evaluation of the drug use disorders identification test (DUDIT) in criminal justice and detoxification settings and in a Swedish population sample. European Addiction Research, 11(1), 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1159/000081413

- Berman, A. H., Bergman, H., Palmstierna, T., & Schlyter, F. (2007). DUDIT - The drug use disorders identification test – manual.

- Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., Stokes, J., Handelsman, L., Medrano, M., Desmond, D., & Zule, W. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0

- Bernstein, D. P., & Fink, L. (1998). Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. A retrospective self-report questionnaire and manual. The Psychological Corporation.

- Bjornestad, J., McKay, J. R., Berg, H., Moltu, C., & Nesvåg, S. (2020). How often are outcomes other than change in substance use measured? A systematic review of outcome measures in contemporary randomised controlled trials. Drug and Alcohol Review, 39(4), 394–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13051

- Borgert, B., Morrison, D. G., Rung, J. M., Hunt, J., Teitelbaum, S., & Merlo, L. J. (2023). The association between adverse childhood experiences and treatment response for adults with alcohol and other drug use disorders. The American Journal on Addictions, 32(3), 254–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.13366

- Cao, Q., & Zhou, Y. (2021). Association between social support and life satisfaction among people with substance use disorder: The mediating role of resilience. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 20(3), 415–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332640.2019.1657545

- Capusan, A. J., Gustafsson, P. A., Kuja-Halkola, R., Igelström, K., Mayo, L. M., & Heilig, M. (2021). Re-examining the link between childhood maltreatment and substance use disorder: A prospective, genetically informative study. Molecular Psychiatry, 26(7), 3201–3209. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01071-8

- Carrozzino, D., Patierno, C., Pignolo, C., & Christensen, K. S. (2023). The concept of psychological distress and its assessment: A clinimetric analysis of the SCL-90-R. International Journal of Stress Management, 30(3), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000280

- Chi, F. W., Parthasarathy, S., Mertens, J. R., & Weisner, C. M. (2011). Continuing care and long-term substance use outcomes in managed care: Early evidence for a primary care-based model. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 62(10), 1194–1200. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.62.10.pss6210_1194

- Clench-Aas, J., Nes, R. B., Dalgard, O. S., & Aarø, L. E. (2011). Dimensionality and measurement invariance in the Satisfaction with Life Scale in Norway. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 20(8), 1307–1317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9859-x

- Clinical Guidelines on Drug Misuse and Dependence Update 2017 Independent Expert Working Group (2017). Drug misuse and dependence: UK guidelines on clinical management.

- Colman, I., Kingsbury, M., Garad, Y., Zeng, Y., Naicker, K., Patten, S., Jones, P. B., Wild, T. C., & Thompson, A. H. (2016). Consistency in adult reporting of adverse childhood experiences. Psychological Medicine, 46(3), 543–549. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715002032

- Copeland, W. E., Shanahan, L., Hinesley, J., Chan, R. F., Aberg, K. A., Fairbank, J. A., van den Oord, E., & Costello, E. J. (2018). Association of childhood trauma exposure with adult psychiatric disorders and functional outcomes. JAMA Network Open, 1(7), e184493. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4493

- Couwenbergh, C., van den Brink, W., Zwart, K., Vreugdenhil, C., van Wijngaarden-Cremers, P., & van der Gaag, R. J. (2006). Comorbid psychopathology in adolescents and young adults treated for substance use disorders: a review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 15(6), 319–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-006-0535-6

- Cruz, D. (2023). Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form: Evaluation of factor structure and measurement invariance. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 16(4), 1099–1108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-023-00556-8

- Derogatis, L. R. (1994). SCL-90-R: symptom checklist-90-R: Administration, scoring & procedures manual. National Computer Systems, Inc.

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- Dovran, A., Winje, D., Overland, S. N., Breivik, K., Arefjord, K., Dalsbø, A. S., Jentoft, M. B., Hansen, A. L., & Waage, L. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in high-risk groups. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 54(4), 286–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12052

- Dube, S. R., Felitti, V. J., Dong, M., Giles, W. H., & Anda, R. F. (2003). The impact of adverse childhood experiences on health problems: Evidence from four birth cohorts dating back to 1900. Preventive Medicine, 37(3), 268–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00123-3

- Engel, K., Schaefer, M., Stickel, A., Binder, H., Heinz, A., & Richter, C. (2016). The role of psychological distress in relapse prevention of alcohol addiction. Can high scores on the SCL-90-R predict alcohol relapse? Alcohol and Alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire), 51(1), 27–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agv062

- Erga, A. H., Hønsi, A., Anda-Ågotnes, L. G., Nesvåg, S., Hesse, M., & Hagen, E. (2020). Trajectories of psychological distress during recovery from polysubstance use disorder. Addiction Research & Theory, 29(1), 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2020.1730822

- Farley, M., Golding, J. M., Young, G., Mulligan, M., & Minkoff, J. R. (2004). Trauma history and relapse probability among patients seeking substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 27(2), 161–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2004.06.006

- Gerhardt, S., Eidenmueller, K., Hoffmann, S., Bekier, N. K., Bach, P., Hermann, D., Koopmann, A., Sommer, W. H., Kiefer, F., & Vollstädt-Klein, S. (2022). A history of childhood maltreatment has substance- and sex-specific effects on craving during treatment for substance use disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 866019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.866019

- Godley, S. H., Smith, J. E., Passetti, L. L., & Subramaniam, G. (2014). The adolescent community reinforcement approach (A-CRA) as a model paradigm for the management of adolescents with substance use disorders and co-occurring psychiatric disorders. Substance Abuse, 35(4), 352–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2014.936993

- Hagen, E., Erga, A. H., Hagen, K. P., Nesvåg, S. M., McKay, J. R., Lundervold, A. J., & Walderhaug, E. (2016). Assessment of executive function in patients with substance use disorder: A comparison of inventory- and performance-based assessment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 66, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2016.02.010

- Helsedirektoratet (2017). Nasjonal faglig retningslinje for behandling og rehabilitering av rusmiddelproblemer og avhengighet.

- Hien, D. A., Jiang, H., Campbell, A. N., Hu, M. C., Miele, G. M., Cohen, L. R., Brigham, G. S., Capstick, C., Kulaga, A., Robinson, J., Suarez-Morales, L., & Nunes, E. V. (2010). Do treatment improvements in PTSD severity affect substance use outcomes? A secondary analysis from a randomized clinical trial in NIDA's Clinical Trials Network. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(1), 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09091261

- Källmén, H., Berman, A. H., Jayaram-Lindström, N., Hammarberg, A., & Elgán, T. H. (2019). Psychometric properties of the AUDIT, AUDIT-C, CRAFFT and ASSIST-Y among Swedish adolescents. European Addiction Research, 25(2), 68–77. https://doi.org/10.1159/000496741

- Lappan, S. N., Brown, A. W., & Hendricks, P. S. (2020). Dropout rates of in-person psychosocial substance use disorder treatments: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 115(2), 201–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14793

- Leza, L., Siria, S., López-Goñi, J. J., & Fernández-Montalvo, J. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and substance use disorder (SUD): A scoping review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 221, 108563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108563

- Löfberg, A., Gustafsson, P. A., Gauffin, E., Perini, I., Heilig, M., & Capusan, A. J. (2023). Assessing childhood maltreatment exposure in patients without and with a diagnosis of substance use disorder. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 17(3), 263–270. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000001091

- López-Goñi, J. J., Fernández-Montalvo, J., & Arteaga, A. (2012). Addiction treatment dropout: Exploring patients’ characteristics. The American Journal on Addictions, 21(1), 78–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00188.x

- MacDonald, K., Thomas, M. L., Sciolla, A. F., Schneider, B., Pappas, K., Bleijenberg, G., Bohus, M., Bekh, B., Carpenter, L., Carr, A., Dannlowski, U., Dorahy, M., Fahlke, C., Finzi-Dottan, R., Karu, T., Gerdner, A., Glaesmer, H., Grabe, H. J., Heins, M., … Wingenfeld, K. (2016). Minimization of childhood maltreatment is common and consequential: results from a large, multinational sample using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. PLoS One, 11(1), e0146058. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0146058

- Martin, E. L., Neelon, B., Brady, K. T., Guille, C., Baker, N. L., Ramakrishnan, V., Gray, K. M., Saladin, M. E., & McRae-Clark, A. L. (2023). Differential prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) by gender and substance used in individuals with cannabis, cocaine, opioid, and tobacco use disorders. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 49(2), 190–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990.2023.2171301

- McKay, M. T., Cannon, M., Chambers, D., Conroy, R. M., Coughlan, H., Dodd, P., Healy, C., O'Donnell, L., & Clarke, M. C. (2021). Childhood trauma and adult mental disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 143(3), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13268

- McLaughlin, K. A., Weissman, D., & Bitrán, D. (2019). Childhood adversity and neural development: A systematic review. Annual Review of Developmental Psychology, 1(1), 277–312. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-devpsych-121318-084950

- Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(2), 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760701756946

- Rajapaksha, R., Filbey, F., Biswas, S., & Choudhary, P. (2022). A Bayesian learning model to predict the risk for cannabis use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 236, 109476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109476

- Rasmussen, I. S., Arefjord, K., Winje, D., & Dovran, A. (2018). Childhood maltreatment trauma: A comparison between patients in treatment for substance use disorders and patients in mental health treatment. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), 1492835. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1492835

- Roberts, N. P., Lotzin, A., & Schäfer, I. (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological interventions for comorbid post-traumatic stress disorder and substance use disorder. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2041831. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2022.2041831

- Robertson, I. E., Sagvaag, H., Selseng, L. B., & Nesvaag, S. (2021). Narratives of change: Identity and recognition dynamics in the process of moving away from a life dominated by drug use. Contemporary Drug Problems, 48(3), 204–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/00914509211027075

- Rowe, C. L., Liddle, H. A., Greenbaum, P. E., & Henderson, C. E. (2004). Impact of psychiatric comorbidity on treatment of adolescent drug abusers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 26(2), 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00166-1

- Ruberu, T. L. M., Rajapaksha, R., Heitzeg, M. M., Klaus, R., Boden, J. M., Biswas, S., & Choudhary, P. (2023). Validation of a Bayesian learning model to predict the risk for cannabis use disorder. Addictive Behaviors, 146, 107799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107799

- Rubinsky, A. D., Dawson, D. A., Williams, E. C., Kivlahan, D. R., & Bradley, K. A. (2013). AUDIT-C scores as a scaled marker of mean daily drinking, alcohol use disorder severity, and probability of alcohol dependence in a U.S. general population sample of drinkers. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 37(8), 1380–1390. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.12092

- Sahani, V., Hurd, Y. L., & Bachi, K. (2022). Neural underpinnings of social stress in substance use disorders. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences, 54, 483–515. https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2021_272

- Sanchez, M., & Amaro, H. (2022). Cumulative exposure to traumatic events and craving among women in residential treatment for substance use disorder: The role of emotion dysregulation and mindfulness disposition. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1048798. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1048798

- Santo, T., Jr., Campbell, G., Gisev, N., Tran, L. T., Colledge, S., Di Tanna, G. L., & Degenhardt, L. (2021). Prevalence of childhood maltreatment among people with opioid use disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 219, 108459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108459

- Svendsen, T. S., Bjornestad, J., Slyngstad, T. E., McKay, J. R., Skaalevik, A. W., Veseth, M., Moltu, C., & Nesvaag, S. (2020). "Becoming myself": How participants in a longitudinal substance use disorder recovery study experienced receiving continuous feedback on their results. Substance Abuse Treatment Prevention and Policy, 15(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-020-0254-x

- Svendsen, T. S., Erga, A., Hagen, E., McKay, J., Njå, A., Årstad, J., & Nesvåg, S. (2017). How to maintain high retention rates in long-term research on addiction: A case report. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 17(4), 374–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533256X.2017.1361831

- Tang, S., Jones, C. M., Wisdom, A., Lin, H. C., Bacon, S., & Houry, D. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences and stimulant use disorders among adults in the United States. Psychiatry Research, 299, 113870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113870

- Thombs, B. D., Lewis, C., Bernstein, D. P., Medrano, M. A., & Hatch, J. P. (2007). An evaluation of the measurement equivalence of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire—Short Form across gender and race in a sample of drug-abusing adults. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 63(4), 391–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.04.010

- van Dam, D., Ehring, T., Vedel, E., & Emmelkamp, P. M. (2013). Trauma-focused treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder combined with CBT for severe substance use disorder: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 13(1), 172. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-172

- Vigdal, M. I., Moltu, C., Svendsen, T. S., Bjornestad, J., & Selseng, L. B. (2023). Rebuilding social networks in long-term social recovery from substance-use problems. The British Journal of Social Work, 53(8), 3608–3626. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcad134

- Voluse, A. C., Gioia, C. J., Sobell, L. C., Dum, M., Sobell, M. B., & Simco, E. R. (2012). Psychometric properties of the drug use disorders identification test (DUDIT) with substance abusers in outpatient and residential treatment. Addictive Behaviors, 37(1), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.030

- Williams, E. C., Rubinsky, A. D., Chavez, L. J., Lapham, G. T., Rittmueller, S. E., Achtmeyer, C. E., & Bradley, K. A. (2014). An early evaluation of implementation of brief intervention for unhealthy alcohol use in the US Veterans Health Administration. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 109(9), 1472–1481. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12600

- World Health Organization (2019). Drugs (psychoactive). World Health Organization. Retrieved August 8, 2023, from https://www.who.int/health-topics/drugs-psychoactive#tab=tab_1

- Wu, C.-H., & Yao, G. (2007). Examining the relationship between global and domain measures of quality of life by three factor structure models. Social Indicators Research, 84(2), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-006-9082-2

- Zhang, S., Lin, X., Liu, J., Pan, Y., Zeng, X., Chen, F., & Wu, J. (2020). Prevalence of childhood trauma measured by the short form of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in people with substance use disorder: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 294, 113524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113524