ABSTRACT

What are the distinctive characteristics of the co-design practices at FabLab Nepal, the first humanitarian FabLab in South Asia? This paper presents select case materials from the project ‘3D Printing for Spinal Cord Injury’ to illustrate how FabLab Nepal operates through collaborative, co-design practices and then reflects on how these observations can enrich a more general understanding of what pluriversal design looks like in practice. Co-design initiatives were developed to suit the local practices and situated knowledge of the project context. What was remarkable was that the participants acknowledged that the co-design approach was not novel, however, they did recognise that its impact was beginning to transform everyday lives, in a gradual transition from survival in a disaster situation to local empowerment and capacity building. In this context, pluriversal design was observed to take the form of knowledge exchange and skills development in the use of printing technology, which gave a voice to the patient’s needs and desires in the design and manufacturing process.

1. Introduction

FabLabs are a vehicle for distributed production, local digital manufacturing, training and creative collaboration that was developed in the West, at MIT, and have been seen to be effectively replicated and established worldwide through the connecting work of the Fab Foundation (A. Smith et al. Citation2016; Soomro, Casakin, and Georgiev Citation2022). The ability to transpose tools and capabilities from one location to another makes FabLabs an effective international response in disaster relief and humanitarian situations, in refugee camps and war zones (Corsini, Jagtap, and Moultrie Citation2022; UNCR Citation2019; IOM Citation2019; Terres Des Hommes Citation2022), as well as a vehicle for the transfer of knowledge and technologies for development around the globe.

A characteristic of many humanitarian FabLabs is that they respond to situations of temporary emergency. FabLab Nepal, from its inception, was a response to a temporary emergency, however its broader humanitarian agenda is focused on engaging members of the local marginalised groups in long-term transformative change in the Nepalese society through design, manufacturing and education (Impact Hub Kathmandu Citationn.d.).

Marginalisation in Nepal is a major issue enacted at micro and macro scales. It can take the form of social, geographical and economic sectors or is gender-driven (Pradhan and Leimgruber Citation2022). Issues of marginalisation also concern the integration of the diverse communities that form the Nepalese population, with more than 120 indigenous ethnic groups and significant disparities in access to resources and political representation. Nepal has traditionally been dominated by Brahmin and Chhetri ethnic groups of the Kathmandu Valley region. The Tibeto-Burman hill people and the Terai population of the South have been under-represented and marginalised in government. Despite a new Constitution in 2015 that presented a more inclusive framework for the country, the historical domination of the majority groups over other communities persists, and the government has yet to fully integrate the promotion and protection of indigenous rights into the domestic legislation (Minority Citation2023; Pyakurel Citation2021).

The FabLab Nepal and Impact Hub Kathmandu agenda, focused on co-designing and manufacturing products with marginalised members of society across all ethnic communities, abilities and genders and supporting the incubation projects of grassroots social entrepreneurs that promote the inclusion of diverse ethnicities, could help develop more effective ways to make assumptions about future needs, to change society from within. As Marradi and Mulder (Citation2022, 2) state: ‘Capacity can be built through value co-creation and experimenting with new ways to address global challenges on a local scale’.

From a pluriversal design perspective, that is, where local indigenous knowledges are valued, ‘solutions grow from place, and cultivating design intelligence becomes a key aspect of democracy based on locality’ (Escobar Citation2018, 44–45), FabLabs can be conceived as yet another imposition of western ideals, values and technologies on other parts of the world. It is a tension that exists in any participatory design situation and foregrounds the importance of navigating situations in ways that are equitable, working in reciprocity with local values and knowledge by involving local communities in design and manufacturing debates (Costanza-Chock Citation2020; Jeldes et al. Citation2022), and keeping the core values of voice and empowerment at the centre of participatory design while contextualising diverse and situated epistemologies, narratives and experiences (R. C. Smith and Sejer Iversen Citation2018; R. C. Smith et al. Citation2020).

The purpose of this paper is to examine how the engagement initiatives at FabLab Nepal worked collaboratively towards the adoption of Western technologies in a way that was complementary to local knowledge, creating the safe space needed ‘to provoke cultural transformations and contribute to the plurality of futures’ (Kambunga et al. Citation2023, 5) in complex social contexts. The paper also explores the notion of ‘humanitarian’ and questions the features of FabLab Nepal that characterise this as a humanitarian FabLab. To examine this, the paper draws on ethnographic materials that were gathered from interviews, focus groups, direct observation, as well as the FabLab Nepal reports on the situated practices that were shaped by and for Nepalese communities. The case study is offered as an illustration of what pluriversal design looks like in practice. The claim is made that what has been observed and reported is an illustration of the practices that can be part of pluriversal design, exhibited at FabLab Nepal in real-world situated life projects that now have their own lives and trajectory through local ownership, in line with participatory design values of collective agency, democracy, and empowerment (Bødker, Dindler, and Sejer Iversen Citation2017; R. C. Smith and Sejer Iversen Citation2018).

2. Background to the formation of FabLab Nepal

2.1. Emergencies and dependencies

Nepal is listed by the UN as one of the least developed countries in the world (UNCTAD Citation2022). An earthquake in 2015 prompted international disaster relief, and the COVID-19 health crisis further limited the recovery and growth of the country. Both natural disasters highlighted the lack of access for Nepalese people to locally distributed manufacturing, skills and resources and their need to rely heavily on external aids, materials and products. As highlighted by James (Citation2017, 2), local manufacturing in emergency relief situations not only offers the benefits of bypassing slow and costly supply chains but also ‘enables existing in-region economic activity to continue, without the deleterious effects of “dumping” products from elsewhere on the local market’. However, in Nepal, the lack of local manufacturing has been a significant issue since before the 2015 earthquake. The country has always imported the majority of supplies from abroad, meaning that if something gets lost or broken during the delivery, the process needs to start again, taking weeks or months. In addition to this, the geographical configuration of Nepal means rural and remote areas are still difficult to reach, with the consequence that people in villages often do not have access to essential resources. Extremely high import duties make the country cost prohibitive for international trade, and the clearance time for goods may be extremely long. Many international companies do not ship to Nepal, so even though products are available on the market, Nepalese people often cannot access to them. These characteristics contribute to Nepal’s ongoing need to address humanitarian emergency supply chain challenges and its over-reliance on foreign countries for design services to support the country’s development, with impacts on the daily life of urban and rural communities, which gives new meanings to the notions of ‘humanitarian’ and ‘emergency’ in relation to the geographical, social, and economic context of Nepal. They also exacerbate the need for local manufacturing because fabricating, making, or remaking things or parts become vital. This is why the making, prototyping and education work of the FabLab is critical in the context of Nepal.

2.2. A bottom-up approach as the foundation of humanitarian design

While the idea for a humanitarian makerspace in Nepal, where products could be prototyped and manufactured, materials tested and knowledge and skills created, was born in the post-2015 earthquake, it became a reality during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021. FabLab Nepal was created within Impact Hub Kathmandu, which is part of the global network of locally operated impact innovation incubators and accelerators (). The two natural disasters were a catalyst for innovation that was already much needed to create longer-term community resilience.

The interest in providing practical solutions to local problems using the advanced technologies available at the lab in combination with local knowledge is shared by many maker spaces in the Global South (Gershenfeld Citation2012; Kera Citation2012; Seo‐Zindy and Heeks Citation2017; Stacey Citation2014). However, FabLab’s Nepal approach to co-design as a sharing of knowledge between designers and participants reflects a bottom-up and locally-driven approach that makes FabLab Nepal different from many maker spaces in South Asia, especially in India and China, where, as Seo‐Zindy and Heeks (Citation2017) observe, there can be a strong social goal to design solutions to help people from poor or marginalised backgrounds; however, the users are primarily from the middle-class and the labs tend not to involve non-expert users from low-income and marginalised communities, addressing local values and priorities that often reflect top-down concerns. At FabLab Nepal, the characteristics and qualities of ‘humanitarian’ actions adapt to suit individual projects and co-creators, in keeping with Chun & Brisson’s definition of humanitarian design as a necessary genre of design ‘that takes as its focus the marginalised, underserved, crisis-threatened people of the world, because mainstream practices and industries have failed them’ (Chun and Brisson Citation2015, 19).

The development of self-sustaining, small-scale distributed manufacturing hubs and the delivery of training for local people to be more autonomous in the production, management, and use of resources is also in line with Nepal’s aspiration to grow as a country. The same year the FabLab opened, the United Nations General Assembly approved a request from the Nepalese government to work towards upgrading from an underdeveloped to a middle-income developing country by 2026 (UN Citation2022).

Born from an emergency-driven situation, FabLab Nepal meets needs that have slowed down the development of the country and made local communities fragile and dependent on external aid for decades.

3. Methods and materials

The ethnographic approach adopted has been informed by Müller’s (Citation2021) concern to develop connectivity among participants through the researcher’s immersion in everyday social realities. While ethnographic studies originated in the field of social anthropology, they have been extensively used in design research to study artefacts and processes from the point of view of the key actors involved (Corsini, Jagtap, and Moultrie Citation2022; Smith et al. Citation2013). The key actors in this study are the FabLab users and the participants in educational programmes and co-design projects.

The team, which is composed of two academics based in the UK, two FabLab Nepal staff members, and the director of Impact Hub Kathmandu/FabLab Nepal, based in Lalitpur, used a co-analysis and co-authoring method in the research process.

The co-analysis and co-authoring approach to research was considered an essential component in the research development and helped the team build a knowledge community (Ilhan and Oguz Citation2019) in which each participant could share their knowledge, bring their own experience and express their voice. The co-authoring sessions were organised around the selection of the materials collected through interviews and focus groups and their analysis in the context of the FabLab’s humanitarian agenda, the study’s research questions and aims and the broader academic debates in which the project is placed. The Nepalese team provided their empirical and place-based perspectives and experiences on the humanitarian approach to co-design at the FabLab and to methods and tools used in their projects and workshops. The UK-based team focused on placing those perspectives and experiences into the broader debate about pluriversal design and co-designing with marginalised groups. The data collected were organised and analysed according to specific themes that emerged from the literature review and contextual research on pluriversal design and were considered meaningful to the FabLab’s approach to design and educational practices, such as desire, inclusivity, the use of a vernacular lexicon and a bottom-up approach to design practices. These themes are discussed in Chapter 5.

The first author contacted the FabLab and Impact Hub teams by email in December 2021, shortly after FabLab Nepal started their activities. Online conversations (Teams, Zoom) between the co-authors on the context, aims and purposes of FabLab Nepal lasted from December 2021 to May 2022, when the first author received funding for the seed project ‘FabLab Nepal: Challenges and Opportunities of the First Emergency-Driven FabLab in South Asia’. The seed project included 21-day fieldwork in Kathmandu to work with the FabLab Nepal team, observe the FabLab co-design and educational practices and identify opportunities for further collaboration. Overall, the first fieldwork was exploratory in nature, enabling the formation of the research team and helping the team identify shared aims and relevant areas of activities for further investigation.

The first fieldwork was followed by a second and more extended field trip from April 6th to May 15th, as part of the ‘Learning to Listen to Local Epistemologies: Lessons from the First Fab Lab in Nepal’ project. The field trip focused on working on the documentation and analysis of two case studies and co-writing this paper. During the second fieldwork, the research team had weekly co-analysis and co-authoring sessions aimed at analysing the data collected through interviews and case studies, and the existing reports from the FabLab workshops and projects. The sessions were held at Impact Hub Kathmandu and FabLab Nepal headquarters in Lalitpur, and online with the second author of this paper in the UK.

Of the two case studies selected and examined by the research team, one is presented here, the ‘3D Printing for Spinal Cord Injury’ pilot project. The case project ran between 2022 and 2023. It aimed to provide support in the use of additive manufacturing to fabricate assistive technology devices for spinal cord injury patients at the Spinal Injury Rehabilitation Centre (SIRC) and digital skills training to the local staff. The case study was selected as an example of situated practices at FabLab Nepal that illustrate how their co-design work responded and listened to voices from marginalised and disadvantaged communities to build localised solutions for global issues (Barnes et al. Citation2020). Essential data collection for the case was completed whilst the first author was in Nepal.

Semi-structured interviews were organised by the FabLab research team with three key actors of the project: Sujit Man Shrestha, the FabLab designer at SIRC and project lead; Jemina Shrestha, Occupational Therapist at SIRC; and Pradip Bajagain, patient at SIRC (referred to as PB in the case study). The interviews lasted between sixty and seventy-five minutes and were conducted by the first author at SIRC. The interviewees were given the option of being interviewed in English or Nepali. They all felt at ease with English. The co-design work with a second SIRC patient, Krishna Rana (referred to as KR), is also reported in the case study. The patient had already left SIRC at the time of the interview and reached his home in Palpa but consented to data and photos from his co-design and therapy processes in the reports produced by Sujit Man Shrestha to be shared with the researchers for this study.

During her visit to SIRC, the first author was also introduced to the 3D printing Lab and the Occupational Therapy room, where photos were taken with permission of the designer and therapist. Observation of the therapy sessions using the 3D-printed assisted devices was not possible due to the sensitive nature of the sessions. However, videos and photos taken by the FabLab designer Sujit Man Shrestha were shared with the researchers, with permission from the patients, therapists, and the author.

4. Case study: FabLab and SIRC (spinal injury rehabilitation centre) co-design therapy assistive devices

4.1. Context and aims

The Spinal Injury Rehabilitation Centre (SIRC) is a non-profit, charitable organisation run by Spinal Injury Sangha Nepal and focused on the treatment and rehabilitation of those affected by spinal cord injury in the country. The Centre was inaugurated in April 2002 in Kathmandu City, and in November 2008, it moved to its current custom-built facility at Saanga village in the Kavre District, on the outskirts of the Kathmandu Valley. Since then, SIRC has developed a range of facilities to support the rehabilitation of spinal injury patients, especially those who come from the most marginalised and fragile societal groups. In recent years, the Centre has had to significantly expand its services because of the widespread awareness of the services provided, as well as a dramatic rise in road traffic and work-related accidents in Nepal.

In 2022, the FabLab Nepal team, in dialogue with the occupational therapists working at SIRC, identified a critical gap in the services offered by SIRC in the lack of customised and right-fitting assistive devices available to patients. Most of the devices in the therapy room were either donated or hand-made in the Centre with available and improvised materials, like ‘popsicle sticks or spoon handles covered in foam and taped’ (Jemina Shrestha, pers. comm., April 23, 2023) (). This is due to the lack of local manufacturing, the absence of companies producing devices in the country, and the difficulty of importing goods from abroad due to extremely high import taxes.

While the use of 3D printing in humanitarian design projects is not innovative (Connor and Marks Citation2016; Corsini, Dammicco, and Moultrie Citation2021; Stickel et al. Citation2017), this case study was considered relevant in the specific context of Nepal for several reasons. Firstly, it provides a significant example of situated co-design practices with marginalised people at FabLab Nepal that respond to an ongoing humanitarian emergency: the lack of local manufacturing of medical devices. This case study also emphasises a historical and still ongoing issue in the relationship between the Global North and Global South, which is the donation of equipment from international organisations without adequate training for local people, which creates false solutions to real problems and does not address social sustainability (Corsini and Moultrie Citation2019). In 2020, Rehab Lab, an international organisation, donated to SIRC a 3D printer, Ender 3 Pro, which was never used due to a lack of local personnel with adequate training and skills and that needed to be fixed due to moisture absorption problems during the years of inactivity. The FabLab team identified a possibility in the presence at SIRC of the unused 3D Printer, showing its creative ability to identify opportunities to solve localised problems by creating inclusive design spaces for Nepalese people in need. As Pradip Bajagain, one of the patients involved in the project, stated: ‘It is not rocket science, but it can change our lives’ (Pradip Bajagain, pers. comm., April 27, 2023).

4.2. Training and the design of assistive devices

The FabLab Nepal and SIRC collaboration started at the beginning of 2023 with a four-month pilot project, the first of this kind in Nepal. A FabLab team member moved into SIRC to co-design, develop and test assistive devices using 3D printing with two patients and two occupational therapists. A 3-month training on CAD and how to operate the 3D printer was also delivered to two occupational therapists and one prosthetic and orthotics technician so that the SIRC team could be independent in the design and production of tailor-made assistive devices by the end of the pilot project.

4.3. Ways of working

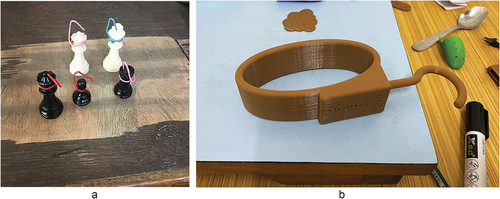

The team includes two occupational therapists, two patients with different levels of spinal injury and different needs, and one designer/technician. They worked together for three months. The aim was to transform the existing universal standard design or homemade produced devices used in the therapy sessions – such as the feeding spoon, finger and abduction splint – into customised devices that meet each patient’s size, shape and needs. The team also created new devices that were not available at SIRC. Some new devices – like the chess holder, spinner, and CNC mobility game – aimed to include games in the therapy sessions because ‘playing makes things easier. We often forget that fun is part of the rehabilitation process’ (Sujit Man Shrestha, pers. comm., April 23, 2023) ().

Figure 3. DIY chess hooks made (a) and prototype of a 3D printed chess hook designed by S.M. Shrestha (b). Photo: S.M. Shrestha 2023.

The team followed an iterative co-design process. The designer participated in the therapy sessions, and through discussion with the patient and occupational therapist, the team tried to identify the mobility problems faced by the patient and associated with the use of the assistive devices. The therapy sessions were followed by a discussion between the designer and therapist, literature and market research and ideas brainstorming.

And again, I come back here [the office] and do some designs, then I go back to the patient, and I take the dimensions, I take the reviews, and then the final product is here. (Sujit Man Shrestha, pers. comm., April 23, 2023)

The patient tested the 3D-printed assistive device during the following therapy session, and adjustments were made according to the patient and occupational therapist’s feedback. The process was then repeated after testing and considering how the device could be improved. Overall,

The role of the patient is to give ideas and test the products. Because we have to identify the patient’s problem, and we do not know about the problem they face. So they will be telling us, for example, if they have problems feeding, grooming, writing, or similar. And we will work it out after that. (Sujit Man Shrestha, pers. comm., April 23, 2023)

Several themes emerged from the observation of methods, processes, and ways of working at SIRC, and from the analysis of the data collected in the interviews. These themes will be explored in the next chapter and show how the situated practices at FabLab Nepal may lead to transformative individual and social change and contribute to the debate on what puriversal design looks like in practice.

5. Findings and discussion

5.1. From patient to co-designer: meeting unheard desires as a transformational practice

When working with marginalised groups, desires and aesthetic pleasure often leave the space to basic and essential needs and functionality (Jagtap Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Sofia, Sanders, and Steinert Citation2012). However, Leitão (Citation2022) highlights the importance for pluriversal social design to be desire-based to strengthen collaborative and transformative practices, shifting the focus from mere needs, which often reflect a Eurocentric model of life, to personal agentic desires. Empowerment comes from meeting one’s own desires, as well as basic needs.

In the interviews for the case study, the topic of ‘desire’ emerged clearly. While some of the devices produced during the project were designed to meet everyday essential needs identified by the patients, other devices were, in fact, designed following the patient’s desires, either to allow them to keep cultivating their passions as part of the rehabilitation process or to meet their desire to have prosthetic devices that would look as natural as possible. Both Jemina Shrestha, the occupational therapist, and Sujit Man Shrestha, the designer, referred to KR’s desire to have a prosthetic finger that was not only functional but also would match his skin tone and have a natural shape. After the first prototype, the patient asked for a re-design that would consider these elements in addition to functionality.

Firstly, I designed something with holes in the coating, but the patient wasn’t happy with it and asked for a different look in the shape and colour, and we developed the final solution which looks like a real thing. (Sujit Man Shrestha, pers. comm., April 23, 2023)

The finger for KR required multiple iterations and clear directions from the patient about shape, size and the colour used for the final prototype until it met his desires. And when that happened, as Jemina Shrestha (pers. comm., April 23, 2023) describes: ‘He was so happy and he thought that he would wear gloves and show people that he had fingers. He was so happy, and seeing his smile on his face, I was so satisfied’ ().

Figure 4. The two prototypes of the ‘finger’ for KS designed by S.M. Shrestha (a) and the patient wearing the two prototypes (b). Photo: S.M. Shrestha 2023.

For PB, his desire to hand-write his personal experience after the accident and surgery that caused his spinal injury led to the design and production of a writing-assistive device:

Because my ultimate goal is to write. I am writing my things and my feelings, not digitally but manually. After I was caught up with this injury, I felt like I had to write it down. Writing is helping me. (Pradip Bajagain, pers. comm., April 27, 2023)

I want to write, and I want to maintain my daily hygiene, you know, I would just wash my face with my hands. But for other people to eat will be helpful, because as I said earlier we don’t want to be dependent on others, you know, for our independent life. Daily livings. It will be, and it is. (Pradip Bajagain, pers. comm., April 27, 2023)

Figure 5. Prototype of the writing assistive device designed by S.M. Shrestha for PB. Photo: Campoli 2023.

The patient’s feeling of empowerment also comes from his being part of a project that helps himself but also other people in similar conditions, to the point that he defines the project as ‘our project’:

Very helpful. Not just me. You can have more persons like me for your project. Let’s not say for ‘your project’ but for ‘our project’ because yes, it is for us. (Pradip Bajagain, pers. comm., April 27, 2023)

Co-designing with marginalised groups has been defined as a process in which designers and non-designers ‘work together to co-design products and services that generate value’ (Jagtap Citation2022, 283). In this co-design project, added values are the sense of empowerment and agency perceived by PB in the transformation from patient to co-designer and the feeling of KR that with a less visible assistive device, he would be perceived as a less vulnerable element of society, as a person that ‘could fit’.

5.2. ‘A world where many worlds fit’: FabLab Nepal as a pluriversal design space for Nepalese communities

In the preface to Designs for the Pluriverse, Escobar beautifully defines ‘difference’ in the context of pluriverse: ‘Today, difference is embodied for me most powerfully in the concept of the pluriverse, a world where many worlds fit, as the Zapatista put it with stunning clarity’ (2028, xvi).

What emerged from the analysis of the case study and is supported by the interviews with the FabLab team and users is that FabLab Nepal is trying to make the many worlds that Nepal contains fit together, embracing diversity through focused engagement of users from different abilities, ethnicities and social backgrounds, and nourishing participation through making. Torretta et al. (Citation2023, 16) state that ‘for nurturing pluriversality through Participatory Design, participation, presence, and direction must be equally pluriversal’. The case study shows FabLab Nepal’s focus on the participation of marginalised and diverse groups in their projects and their attempt to make local people active agents of change through implementing access to the design and manufacturing process and co-designing solutions locally and with non-experts.

It is true that none of the project ‘is rocket science’; however, the ability of a local community to make things for themselves, with the newly acquired knowledge to use the tools that are available to them is critical to a pluriversal, inclusive and more democratic approach to prototyping, making and learning in a developing country.

5.3. Vernacular lexicon and concepts to enable participation

Digital fabrication spaces and processes often seem challenging to non-expert users, and the tools and machines available may be unfamiliar and intimidating. This was seen to be the case in these settings, in Nepal, where access to technology is still restricted for most of the population due to socio-economic factors. Shifting the focus from the technical aspects of machinery towards local communities and their needs and desires helps build long-term participatory processes with diverse actors, and especially with non-expert users, in keeping with what Dreessen and Schepers (Citation2020) have previously noted.

To make this shift towards building social infrastructures, the FabLab team emphasised the importance of ‘speaking the users’ language’ when working with non-designers, agreeing with Szaniecki et al. (Citation2020) on the need to make visible the nature and territoriality of their authentic, local and existing knowledge and ways of doing to promote and nurture participation and inclusivity.

In the case study, ‘speaking the users’ language’ was essential not only to engage the patients in the co-design process but also to provide effective design training to the SIRC staff and ensure the longevity and sustainability of the project. It required a translation of human-centred design principles and processes into vernacular lexicon and concepts, defining ‘vernacular’ with reference to Escobar (Citation2018, 37), from Bourdier and Minh-ha (Citation2011), as:

… a space of possibility that could be articulated to creative projects integrating vernacular forms, concrete places and landscapes, ecological restoration, and environmental and digital technologies in order to deal with serious problems of livelihood while reinvigorating communities.

In practice, both the FabLab team and the key-actors in the case study emphasised the importance of using examples from users’ daily lives during training and co-design activities and the need to consider that users from different indigenous ethnic groups, social backgrounds or urban and rural areas may have different lifestyles, traditions and ways of referring to the same objects and processes, as well as different needs and a different understanding of how things work.

From the interviews emerged the need for the FabLab team to master human-centred design principles and processes, unlearn them and relearn them through discussion with the participants engaged in the FabLab activities (Pradita Pradhan, pers. comm., May 30, 2022), attuning to the local sensitives of the different regions, ethnicities and abilities, their insights and knowledge.

This echoes the FabLab team’s thoughts shared in the focus groups about the importance to avoid considering the participants in the activities as ‘non-experts’ but rather ‘experts in different fields of life’ (Pallab Shrestha, pers. comm., May 31, 2022), individuals that bring their own expertise, skills, perspectives, ways of thinking and lexicon into the co-design process, in line with one of the core aspects of participatory design as defined by Bødker et al. (Citation2022) of seeing people as skilled and resourceful in their own practice.

The sharing of human-centred design principles and concepts is the start of a process that sees the role of the FabLab Nepal designers shift more and more towards that of facilitators as the project unfolds, leaving room for engaged collaboration and the formation of pluriversal design spaces where participants become active agent of change. This process also emerges in the case study, to the point that the different actors perceive themselves as co-designers and feel ownership of the project by the end of it. As noted by Ebbesson et al. (Citation2024), the facilitator role, and the ability to transition this role to other actors is a key challenge for long term engagement in co-design projects.

As situated practices that emerge from local communities’ needs and desire FabLab Nepal’s projects need to be sustainable in the long term. The application of pluralistic and inclusive approaches that give attention to the complexity of the social and geographical context of Nepal supports the longevity of the projects through the creation of those ‘ongoing and open processes of infrastructuring, characterised by building long-term working relationships with diverse actors or communities over time’ (Dreessen and Schepers Citation2020, 25), which are critical in participatory design. These actors and communities at FabLab Nepal are marginalised groups of users and makers who would otherwise not have access to these facilities and whose voices, needs and desires would stay unheard.

6. Conclusion and further investigation

FabLab Nepal is a recent initiative, with only over two years of activities at the time this paper is written. Research and collaboration with the research team started at the FabLab’s formative stages. The team aims to develop this collaboration further and has already identified new avenues for research, development and societal impact.

Researching strategies to decentralise the FabLab Nepal activities to reach more remote areas with a focus on including more indigenous ethnic groups and rural communities is a priority. Despite the ban and criminalisation of caste-based discrimination by the Government of Nepal in 1963, hierarchy and privileges connected to ethnicity are still a reality in Nepal and lead to marginalisation and social injustice as endemic factors.

Specific tools and methods to work with Nepalese marginalised rural and urban communities, with a focus on women and girls from an economically disadvantaged background, should also be investigated further. Conversations with the local government and funding bodies to support further educational programmes are ongoing.

Overall, the research team agrees that giving marginalised and unheard groups in Nepal the empowering tools to think and act like designers and feel designers for themselves and their community, as was observed in the case study, may enable these groups to develop that collective agency that, as stated in Brown (Citation2009) and Manzini (Citation2015), may bring solutions to a vast and great set of contexts and is a common trajectory of participatory design practices. These locally situated projects, within the FabLab ethos, will eventually lead to deep social changes from the bottom and from within. As Forsyth (Citation2021) states in relation to Nepal, transformative change in developing countries can only happen if discussion of essential issues and strategic planning are more inclusive and involve people with limited forms of expression in situations of high social inequality.

Ethical approval statement

The research project has ethical approval from the Open University Research Ethics Committee, reference number HREC/4670.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of all participants in sharing and shaping the reflections presented in this paper. We particularly want to thank: the Impact Hub Kathmandu and FabLab teams, Sujit Man Shrestha, Pradip Bajagain, and Jemina Shrestha.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barnes, A. J., K. Charnley, R. Dohmen, and N. Lotz. 2020. “Colonial Histories, Museum Collections, FabLabs and Community Engagement: Flows of Practices, Cultures and People – a Roundtable.” Open Arts Journal 9:91–118. https://doi.org/10.5456/issn.2050-3679/2020w07.

- Bødker, S., C. Dindler, and O. Sejer Iversen. 2017. “Tying Knots: Participatory Infrastructuring at Work.” Computer Supported Cooperative Work 26 (1–2): 245–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-017-9268-y.

- Bødker, S., C. Dindler, O. Sejer Iversen, and R. C. Smith. 2022. Participatory Design. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-02235-7.

- Bourdier, J. P., and T. Minh-Ha. 2011. Vernacular Architecture from West Africa: A World in Dwelling. London: Routledge.

- Brown, T. 2009. Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation. New York: HarperCollins.

- Chun, A. M. S., and I. E. Brisson. 2015. Ground Rules in Humanitarian Design. Somerset, New Jersey: Wiley.

- Connor, A. M., and S. Marks. 2016. “3D Printing Meets Humanitarian Design Research: Creative Technologies in Remote Regions.” In Creative Technologies for Multidisciplinary Applications, edited by A. M. Connor and S. Marks, 54–75. United States: IGI Global.

- Corsini, L., V. Dammicco, and J. Moultrie. 2021. “Frugal Innovation in a Crisis: The Digital Fabrication Maker Response to COVID‐19.” R & D Management 51 (2): 195–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12446.

- Corsini, L., S. Jagtap, and J. Moultrie. 2022. “Design with and by Marginalized People in Humanitarian Makerspaces.” International Journal of Design 16 (2): 91. https://doi.org/10.57698/v16i2.07.

- Corsini, L., and J. Moultrie. 2019. “Design for Social Sustainability: Using Digital Fabrication in the Humanitarian and Development Sector.” Sustainability 11 (13): 3562. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133562.

- Costanza-Chock, S. 2020. Design Justice : Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need. Cambridge: The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/12255.001.0001.

- Dindler, C., R. Charlotte Smith, and O. Sejer. 2020. “Computational Empowerment: Participatory Design in Education.” CoDesign 16 (1): 66–80.

- Dreessen, K., and S. Schepers. 2020. “Shifting Towards Community-Building in Opening Up FabLabs for Non-Expert Users.” Strategic Design Research Journal 13 (1): 24. https://doi.org/10.4013/sdrj.2020.131.03.

- Ebbesson, E., J. Lund, and R. Charlotte Smith. 2024. “Dynamics of Sustained Co-Design in Urban Living Labs.” CoDesign 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2024.2303115.

- Escobar, A. 2018. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. New Ecologies for the Twenty-First Century. Hauppauge: Duke University Press.

- Forsyth, T. 2021. “Time to Change? Technologies of Futuring and Transformative Change in Nepal’s Climate Change Policy.” Globalizations 18 (6): 966–980. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2020.1859766.

- Gershenfeld, N. 2012. “How to Make Almost Anything: The Digital Fabrication Revolution.” Foreign Affairs 91 (6): 43–57.

- Ilhan, A. O., and M. C. Oguz. 2019. “Collaboration in Design Research: An Analysis of Co-Authorship in 13 Design Research Journals, 2000-2015.” Design Journal 22 (1): 5–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2018.1560879.

- Impact Hub Kathmandu. n.d. “What is FabLab Nepal?” Accessed November 5, 2022. Impact Hub Kathmandu. https://kathmandu.impacthub.net/fablab-nepal/.

- IOM. 2019. “Djibouti’s First ‘Fab Lab’ Offers Young Migrants Tech and Support”. IOM. Accessed December 2, 2022. https://www.iom.int/news/iom-djiboutis-first-fab-lab-offers-young-migrants-tech-and-support.

- Jagtap, S. 2019a. “Design and Poverty: A Review of Contexts, Roles of Poor People, and Methods.” Research in Engineering Design 30 (1): 41–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00163-018-0294-7.

- Jagtap, S. 2019b. “Key Guidelines for Designing Integrated Solutions to Support Development of Marginalised Societies.” Journal of Cleaner Production 219:148–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.340.

- Jagtap, S. 2022. “Co-Design with Marginalised People: Designers’ Perceptions of Barriers and Enablers.” CoDesign 18 (3): 279–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2021.1883065.

- James, L. “Opportunities and Challenges of Distributed Manufacturing for Humanitarian Response.” 2017. In IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC), San Jose, CA, USA, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1109/GHTC.2017.8239297.

- Jeldes, J. C., S., Cortés-Morales, R., Rodo Lunissi, and A. Moreira-Muñoz, 2022. “Aconcagua Fablab: Learning to Become with the World Through Design and Digital Fabrication Technologies.” International Journal of Art & Design Education 41:23–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/jade.12394.

- Kambunga, A. P., R. Charlotte Smith, H. Winschiers-Theophilus, and T. Otto. 2023. “Decolonial Design Practices: Creating Safe Spaces for Plural Voices on Contested Pasts, Presents, and Futures.” Design Studies 86:101170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2023.101170.

- Kera, D. 2012. “Hackerspaces and DIYbio in Asia: Connecting Science and Community with Open Data, Kits and Protocols.” Journal of Peer Production 1 (2): 1–8.

- Leitão, R. M. 2022. “From Needs to Desire: Pluriversal Design as a Desire-Based Design.” Design and Culture 14 (3): 255–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2022.2103949.

- Manzini, E. 2015. Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social innovation. Design Thinking, Design Theory. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

- Marradi, C., and I. Mulder. 2022. “Scaling Local Bottom-Up Innovations Through Value Co-Creation.” Sustainability 14 (18): 11678. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811678.

- Minority Rights. 2023. “Nepal.” Minority Rights. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://minorityrights.org/country/nepal/#:~:text=The%20hill%20peoples%20who%20speak,in%20terms%20of%20the%20distribution.

- Müller, F. 2021. Design Ethnography: Epistemology and Methodology. Cham: Springer Nature.

- Pradhan, P. K., and W. Leimgruber. 2022. Nature, Society, and Marginality Case Studies from Nepal, Southeast Asia and Other Regions (Vol. 8). Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-21325-0 .

- Pyakurel, U. 2021. Reproduction of Inequality and Social Exclusion: A Study of Dalits in a Caste Society, Nepal. Singapore: Springer.

- Seo‐Zindy, R., and R. Heeks. 2017. “Researching the Emergence of 3D Printing, Makerspaces, Hackerspaces and FabLabs in the Global South: A Scoping Review and Research Agenda on Digital Innovation and Fabrication Networks.” Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries 80 (1): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1681-4835.2017.tb00589.x.

- Smith, A., M. Fressoli, D. Abrol, E. Arond, and A. Ely. 2016. “Hackerspaces, Fablabs and Makerspaces.” In Grassroots Innovation Movements, 116–138. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315697888.

- Smith, A., S., Hielscher, and S., Dickel. 2013. “Grassroots Digital Fabrication and Makerspaces: Reconfiguring, Relocating and Recalbirating Innovation?” Brighton: SPRU, Science and Technology Policy Research. SPRU working paper series; 2013-02.

- Smith, R. C., and O. Sejer Iversen. 2018. “Participatory Design for Sustainable Social Change.” Design Studies 59:9–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2018.05.005.

- Smith, R. C., H. Winschiers-Theophilus, A. Paula Kambunga, and S. Krishnamurthy. 2020. “Decolonizing Participatory Design: Memory Making in Namibia.” PDC ‘20: Proceedings of the 16th Participatory Design Conference 2020 - Participation(s) Otherwise, Manizales, Colombia, 15–19 June 2020. https://doi.org/10.1145/3385010.3385021.

- Sofia, H., E. B. N. Sanders, and M. Steinert. 2012. “Participatory Design with Marginalized People in Developing Countries: Challenges and Opportunities Experienced in a Field Study in Cambodia.” International Journal of Design 6 (2): 91–109.

- Soomro, S. A., H. Casakin, and G. V. Georgiev. 2022. “A Systematic Review on FabLab Environments and Creativity: Implications for Design.” Buildings 12 (6): 804. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12060804.

- Stacey, M. 2014. “The Fab Lab Network: A Global Platform for Digital Invention, Education and Entrepreneurship.” Innovations 9 (1–2): 221–238.

- Stickel, O., K. Aal, V. Fuchsberger, S. Rüller, V. Wenzelmann, V. Pipek, V. Wulf, and M. Tscheligi. 2017. “3D Printing/Digital Fabrication for Education and the Common Goo.” In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Communities and Technologies, Troyes, France. 315–318. ACM.

- Szaniecki, B., B. Serpa, I. Portela, M. Sirito, M. Costard, and S. Batista. 2020. “Participation Otherwise: Practices By/From the Global South.” PDC ‘20: Proceedings of the 16th Participatory Design Conference 2020 - Participation(s) Otherwise, 15–19 June 2020, Manizales, Colombia. https://doi.org/10.1145/3384772.3385171 .

- Terres Des Hommes. 2022. “FabLab: An Innovation Space to Reach Vulnerable Youth.” Terres Des Hommes. Accessed December 2, 2022. https://www.tdh.org/en/projects/fablabrif.

- Torretta, N. B., L. Reitsma, P.-A. Hillgren, T. Nair van Ryneveld, A.-M. Hansen, and Y. Castillo Muñoz. 2023. “Pluriversal Spaces for Decolonizing Design: Exploring Decolonial Directions for Participatory Design.” Diseña 22 (2): Article.8. https://doi.org/10.7764/disena.22.Article.8.

- UN. 2022. “Nepal Graduation.” UN. Accessed December 2, 2022. https://www.un.org/ldcportal/content/nepal-graduation-status.

- UNCR. 2019. “FabLab: Humanitarian Innovation Through Advanced Technologies.” UNCR. Accessed May 2, 2023. https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/52777.

- UNCTAD. 2022. “UN List of Least Developed Countries.” UNCR. Accessed April 30, 2023. https://unctad.org/topic/least-developed-countries/list.