ABSTRACT

This article is a case study of a college-based storytelling initiative in Boston that seeks to transform dominant narratives of gun violence that are harmful and dehumanising by centring those most impacted. It builds on practices of critical making which can be understood as the externalisation of critical thinking into the creation of a shared artefact. When done collaboratively with community partners directly impacted by the intended outcome of the artefact, critical making can foster multiperspectivalism, awareness of injustices, and motivation to bring about change. In order for collaborative critical making to be adequately supported within higher education for these ends, novel infrastructure is necessary. Through an in depth analysis of the Transforming Narratives of Gun Violence initiative, we examine the infrastructure that supports collaborative critical making across three scales: the classroom, the college, and the community. We look across three dimensions: listening, expression, and governance. The article describes challenges and opportunities of working within higher education, and concludes with suggestions for future research.

1. Introduction

The guiding principles of a liberal arts education in the United States can be traced back well over a hundred years. Thomas Jefferson explained that it should create good ‘habits of mind’. Ralph Waldo Emerson declared that colleges should ‘teach learning. But they can only serve us, when they aim not to drill, but to create’ (Citation2024). Emerson touted a kind of thinking that was active and generative. But the questions Emerson didn’t address were, who is the ‘us’ that these institutions serve? And to what end? W.E.B. DuBois, the first Black American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard, adds an important perspective: ‘The aim of the higher training of the college is the development of power, the training of a self whose balanced assertion will mean as much as possible for the great ends of civilization’ (Citation1957).

The assertion that learning is power, and that power is directed towards the ‘great ends of civilisation’ has been embraced in rhetoric in most contemporary liberal arts contexts, but largely unrealised in practice. The pursuit of knowledge and the cultivation of learning are valuable ends, but within the framing of academic mission statements, they are often disconnected from the social context in which power is manifested. What is typically referred to as critical thinking lends power to the learner, but does little to challenge the structures in which thinking happens and through which power is distributed beyond the institution.

Colleges and universities often seek other ways of ‘giving back’ to surrounding communities, such as service-learning or student volunteering. And while these initiatives are well intentioned, they can create one-way transactions with students as ‘giver’ and communities as ‘recipient’, perpetuating white saviour paradigms (Mitchell, Donahue, and Young-Law Citation2012; Serpa et al. Citation2020). The Brazilian philosopher and activist Paolo Freire puts it this way: ‘No pedagogy which is truly liberating can remain distant from the oppressed by treating them as unfortunates and by presenting for their emulation models from among the oppressors. The oppressed must be their own example in the struggle for their redemption’ (Citation1970, 54). What Freire refers to as the ‘oppressed’ are those that have been consistently denied access to the benefits of the institutions claiming to serve them, where they might be datapoints in institutionally sanctioned examples but never get to be ‘their own examples’. And while colleges and universities are investing in correcting for this exclusion, these investments often look like service learning or social justice centres that sit outside of the academic core of the institution. For pedagogy to be truly liberating, Freire argues, those typically excluded from student-centred learning need to be brought into the centre of the pedagogical process.

This article reports on a pedagogical initiative that seeks to distribute the power of higher education through structuring extra-institutional collaboration into the curriculum. The initiative on which we focus explores what we call collaborative critical making, where the process of creating shared artefacts is the central activity that is supported by listening and the careful cultivation of relationships across difference and power. The initiative illustrates that introducing extra-institutional collaboration into the existing structures of higher education challenges the very logics in which value is typically produced. Colleges and universities value individual achievement, with most assessment instruments designed to measure critical thinking. But with appropriate infrastructure, the externalisation of thinking onto shared objects can foster multiperspectivalism, awareness of injustices, and motivation of learners to bring about change. This infrastructure is highly complex, requiring significant changes in practice beyond the classroom, including at the level of the college and the larger community (Mitchell Citation2008; Salam et al. Citation2019).

In December 2021, we introduced the Transforming Narratives of Gun Violence initiative (TNGV) at Emerson College in Boston, MA, in collaboration with the Gun Violence Prevention Center at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), and the Louis D. Brown Peace Institute, a community organisation focused on peace and healing in the wake of violence. TNGV supports the collaborative creation of stories of community violence, healing, harm, and solidarity, within the communities most impacted by gun violence in Boston. Following Huybrechts et al. (Citation2017), the institution in which critical making projects exist must be understood as a highly dynamic and contested space (Streeck and Thelen Citation2005), that has an essential and constantly changing impact on outcomes. We understand the infrastructure of the college environment as not only supporting, but also shaping practice (Niewöhner, Citation2015). Building on scholarship that establishes infrastructure not simply as a passive backdrop, but as formative of the practices that exist within it, the current study is an analysis of infrastructuring (Pipek and Wulf Citation2009; Star and Bowker Citation2002), and seeks to understand collaborative critical making in higher education as a dynamic, and constantly evolving set of practices.

Following Karasti and Blomberg (Citation2018), we take the infrastructure of higher education institutions as our unit of analysis and provide thick description of how practices of critical making are supported or challenged at the levels of the classroom, the college, and the community. We analyse these practices along three dimensions: expression, listening, and governance. In the following section, we define collaborative critical making as an expansion of critical thinking and situate the process of collaboration within participatory design discourses. Then, we describe our study methodology and introduce the case study of TNGV, which is followed by an analysis of the case through the lens of the three dimensions. Finally, we explore the implications of TNGV beyond the case study and conclude with limitations and a prompt for future research.

2. From critical thinking to critical making

The culture of critique is at the centre of scholarly life. Ideas are criticised so that they can be built upon. New knowledge is produced by finding shortcomings in existing knowledge. The structures of higher education institutions are built to support this activity, recognising and rewarding individual contributions. But this comes with challenges. As Kathleen Fitzpatrick explains: ‘The competitive individualism that the academy cultivates makes all of us painfully aware that even our most collaborative efforts will be assessed individually, with the result that even those fields whose advancement depends most on team-based efforts are required to develop careful guidelines for establishing credit and priority’ (Citation2019, 27). The individualised pursuit of critical thinking has informed the very foundation on which higher education institutions conduct their business and articulate their value.

Critical thinking as a modality of learning can be traced back to John Dewey’s concept of reflective thinking from his 1910 book How We Think. Edward Glaser (Citation1941), a graduate student at Columbia Teachers College applied Dewey’s ideas to a novel pedagogical framework in his 1941 Masters thesis. Glaser defined critical thinking as ‘(1) an attitude of being disposed to consider in a thoughtful way the problems and subjects that come within the range of one’s experiences, (2) knowledge of the methods of logical inquiry and reasoning, and (3) some skill in applying those methods’. In 1983, the California State University system mandated that all students take a critical thinking course, at which point critical thinking became the standard paradigm for effective higher learning (Haber Citation2020). The aims of the California course were described as follows: To give students ‘an understanding of the relationship of language to logic, leading to the ability to analyze, criticize and advocate ideas, reason inductively and deductively, and reach factual or judgmental conclusions based on sound inferences drawn from unambiguous statements of knowledge or belief’. The infrastructure within higher education institutions that supports the individual, tuition-paying student, to analyse, criticise, and advocate within the range of their experiences, is also the infrastructure that limits the distribution of knowledge and the cultivation of shared knowledge.

We explore the practice of critical making as an augmentation of this framework. Critical making has its roots in maker culture and the DIY movement in art and technology (Busch Citation2022; Hertz Citation2012; Ratto Citation2011; Hertz Citation2023), and ostensibly extends the logic of critical thinking into the material world. Garnet Hertz (Citation2012) describes the act of creating objects as ‘things to think with’. Charney (Citation2011) claims that ‘making is the universal infrastructure of production – be it technical or artistic, scientific or cultural. Making is a type of applied thinking that sits at the core of creating new knowledge of all kinds’. The literature and practice of critical making has focused on the externalisation of thought into the material world. If critical thinking in higher education is the ability for a learner to understand a problem from multiple perspectives, then critical making is the externalization of this multiperspectivalism manifested through the creation of an artefact. We hypothesise that critical making lends itself more readily than critical thinking to what Fitzpatrick calls ‘generous thinking’, which she defines as thinking with rather than against (Citation2019). Critical making practices can support more inclusive structures of education that more equitably distribute the benefits of the knowledge produced. At its best, they do this by inviting non-traditional learners into the act of knowledge generation, and by pushing traditional gatekeepers (peer reviewed journals, or reputable news organisations) to question how they adjudicate knowledge quality. The integrity of knowledge can be negotiated based on the context of where and how something is made.

3. Infrastructuring collaborative critical making

If the practices of critical making are capable of generating the conditions for collaboration across difference, how might institutions augment the existing logics of individualised assessment to support them? On one level, any process that supports collaborative making is influenced by traditions of user-centred design (UCD) (Still and Crane Citation2017), human-centred design (HCD) (Friess Citation2010), and participatory design (PD) (Bødker et al. Citation2022). But it is well rehearsed in the critical design literature that participatory processes do not always result in better outcomes or more inclusive procedures. They can reinforce existing power structures. As critical design scholar Sasha Costanza-Chock points out: ‘UCD faces a paradox: it prioritizes “real-world users”. Yet if, for broader reasons of structural inequality, the universe of real-world users falls within a limited range compared to the full breadth of potential users, then UCD reproduces exclusion by centering their needs’ (Citation2020, 9). Selecting users to centre in any design process is a deliberate decision that impacts outcomes. Often the users most accessible to designers are not the ones most in need of the design solution (Barcham Citation2023). And still, designers of all stripes boast about the users who participate in their processes, and rarely feel the need to justify the selection, or to invest in selection procedures that are equitable. In direct response to this, Costanza-Chock, in their book Design Justice, points to the range of design practitioners who are ‘working to rethink extractive design processes and to replace them with approaches that produce community ownership, profit, credit, and visibility’ (20). The point being that the incorporation of participatory design practices in institutions of higher education need to be accompanied by a questioning of the power dynamics that already exist within that institution (DiSalvo Citation2022; Gordon and Mugar Citation2020). Simply involving other people in the act of creation does not itself challenge structures of power or the values that maintain them (Campanella et al. Citation2022; Matthews et al. Citation2023). DiSalvo (Citation2022) makes the argument that design processes themselves represent ‘small d democracy’, where power is questioned (or not) and exercised.

Within design processes, it is possible to be deliberate about who participates, how they participate, and how outcomes are decided and pursued. It is possible, even within a classroom environment pushing up against the limits of critical thinking outcomes, to create small d democracy. The challenge is in how this democratic exploration gets sustained once the protected space of the design process has concluded. Design can create an ideal democratic context, but if that democratic space is entirely disconnected from the reality of participants, its effects will be short-lived. Gautam and Tatar (Citation2020) argue that specific attention needs to be paid to the agency of participants before they enter the design process. The value of participatory design, they argue, is not in inviting participants into addressing big structural issues (Bødker and Kyng Citation2018), but in enabling participants to realise their agency in day-to-day interactions by limiting the design goals to things within their control. The design process is most powerful when it seeks to enhance personal agency of participants through the creation of tangible outcomes.

This points to the fact that collaborative design within the context of any institution is challenging, because it is likely disconnected from things within the control of the participants. But it is also true that these practices outside of an institution are challenging in that they can be difficult to sustain. The present case study looks at collaborative critical making within an institutional context and examines how it can be supported through infrastructuring. According to Helmke and Levitsky (Citation2004) institutions are compositions of rules and procedures circulated through channels perceived as official. These rules and procedures often serve to legitimise design practices (Jalbert Citation2016), or simply provide the stability and structure to replicate and disseminate them (Hector and Botero Citation2022). In any case, the institution is not an inert backdrop in front of which design takes place, but instead, it is an active site of change which plays a role in framing the community-centred work (Huybrechts, Benesch, and Geib Citation2017). This is represented in the shift from a focus on infrastructure to infrastructuring, which Korn et al. (Citation2019) describe as a practical achievement: ‘Infrastructures are not simply in existence, but they are built, installed, maintained, repaired, used, worked around/against, appropriated and so on’. In order to understand how a programme persists over time, it is essential to abandon the assumption that infrastructures are stable or even coherent (Karasti & Blomberg, Citation2018). This provides an analytical lens wherein to understand a phenomenon it is more valuable to look at the shifting background than it is to try to fix the foreground as an object of study.

In the context of higher education, this means scrutinising the values and logics of institutions and then looking beyond the classroom and the research project to understand how collaborative critical making can persist in the world (Niewöhner 2015). This includes teaching, defining expertise, creating curriculum, bringing in money, making decisions, etc. We categorise these activities within three dimensions: listening, expression, and governance. Listening includes all the conditions that support trust, sharing, and collaboration. Expression includes everything that supports the creative process, and the articulation of ideas into artefacts. And governance includes the official and unofficial mechanisms of decision-making that challenge traditional institutional frameworks. In the next section, we describe the TNGV initiative and provide insights into how collaborative critical making is supported and challenged by the dynamic infrastructure of a higher education institution.

4. Case study: transforming narratives of gun violence

4.1. Methods

Each of this study’s authors bring an important perspective to the research. Eric Gordon is a communications scholar and designer who brings an expertise in collaborative design and the use of creative methods for social activism and advocacy; Rachele Gardner is a trained social worker and is responsible for facilitating the community partnerships in TNGV, and together with Gordon, builds the supporting infrastructure at Emerson College through the Engagement Lab. Clementina Chéry is a survivor of gun violence and chaplain, the president and CEO of the Louis D. Brown Peace Institute. And Chana Sacks, an internal medicine physician, and Peter Masiakos, a paediatric surgeon, are co-directors of the Gun Violence Prevention Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, and champions of centring those with lived experience in their research and bringing stories of those most impacted by gun violence to bear on hospital practices and physician education.

We employ a case study methodology (Yin Citation2017) in order to provide a rich description of a complex phenomenon. Case studies provide comprehensive and in-depth investigations of real-life phenomena within their natural context (Jankowski and Jensen Citation1991). We draw primarily on material publicly available on the initiative website, and include personal experiences, personal observations, and shared documents. Unlike traditional case studies, we look beyond the programme itself to the infrastructure that supports its implementation. The authors have played a leadership role in the creation of the initiative. While this sacrifices some objectivity, it also provides opportunity for self-critique and a nuanced understanding that paints a more holistic picture of the work.

Case studies are not typically understood as research by institutional review boards (IRB), as they are not intended to generalise knowledge, but instead provide a localised example. As such, the case featured in this article was deemed exempt by Emerson’s IRB.

4.2. Background and program description

In 2021, the CDC released a report calling attention to gun violence as a pervasive public health crisis, growing steadily over the last two decades. The report describes that nearly every person in America is affected in some way by gun violence. People who survive a firearm-related injury may experience long-term consequences, including physical disability from injury and chronic mental health conditions, including post-traumatic stress disorder (Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence and Coalition to Stop Gun Violence Citation2021). The direct health effects of this trauma impact not only those struck by a bullet, but their family members as well (Song et al. Citation2023). Further, the stress of growing up in communities plagued by gun violence impacts learning, mental health, and chronic disease (Morsy and Rothstein Citation2016). While gun violence impacts everyone, firearm-related homicide and interpersonal violence is felt most profoundly in communities of colour. In Massachusetts, Black males aged 15–35 have a firearm homicide rate 22 times higher than their White counterparts (Massachusetts Gun Deaths: 2019, Citation2019). In Boston, there were over 3,600 shots fired between January 2019 and August 2022, 80% of which occurred in the predominantly Black neighbourhoods of Dorchester, Roxbury, and Mattapan (Workbook: BPD Shots Fired Dashboard, Citation2022). These communities and the Black youth living there are facing a multi-dimensional crisis.

News stories often fail to convey the complexity of the problem – how gun violence ripples through a community, what circumstances lead someone to pick up a gun, and how the community comes together to grieve and heal. The reductive media coverage gives the perception that Black neighbourhoods are ‘dangerous’ despite the many within these communities working to interrupt cycles of violence and create conditions for peace in the face of structural barriers. As long as public media narratives focus only on individual responsibility and consequence, policies will do the same and will continue to fail to address the root causes of these issues.

In 2020, with this in mind, Sacks and Masiakos approached Emerson College with a request for better stories. Over the course of one semester, students and a faculty member partnered with the hospital to source and document untold survivor stories within a class. This class functioned much like a traditional documentary film class, where subjects were identified, interviewed, and then a series of four short videos were produced. The stories illuminated deeply personal experiences of gun violence. The videos, while powerful, did not have much of a life beyond the semester. The products were delivered to the hospital and the students and faculty moved on to the next semester; minimal connection with the survivors or the hospital was maintained. Meaningful stories were produced, but there were no structures or plans in place to steward the products for further impact. So when Sacks and Masiakos returned to Emerson to partner again, Gordon and Gardner proposed a different approach, with an eye towards sustained and measurable impact. They proposed a multi-year partnership to not only produce stories, but to build institutional infrastructure through the Engagement Lab, Emerson College’s laboratory for collaborative learning, design, and research, to practice collaborative storytelling and design for social impact. Shortly thereafter the partners invited Clementina Chéry and her organisation, the Louis D. Brown Peace Institute, to join the effort as a third anchor partner.

With a three-year funding commitment from MGH to the Engagement Lab, TNGV was launched in December 2021. With the goal of disrupting harmful, stigmatising, and sensationalised narratives about gun violence, the initiative sought to place those with direct experience of gun violence, whose voices are often excluded from the shaping of narratives and policies, at the very centre of creating new narratives. Instead of telling stories about those impacted by gun violence, the initiative would tell stories and design solutions with them in multi-disciplinary classes. These classes, called Social Impact Studios (SIS), each involve an anchor partner organisation and ‘learning partners’ identified by the partner organisation, who join the college students in the classroom as co-creators. TNGV supports four to six SIS per year in departments across Emerson College, including film, immersive media, theatre, game design, journalism, and more. At the time of this writing, 82 students, 7 faculty, 31 learning partners, and 5 community-based organisations have participated in the initiative.

5. Discussion

Each individual social impact studio involves the practice of collaborative critical making at the micro scale, and combined together with supportive infrastructure at the college and community scale, TNGV represents a robust model for potential impact. We have identified three dimensions of collaborative critical making in TNGV that are necessary and mutually supportive: listening, expression, and governance. In the discussion that follows, we will describe each of these three dimensions and then provide examples of how they are practiced at all three scales of TNGV: in the classroom, at the college, and outward into the broader community.

As Andrew Dobson argues in his book Listening for Democracy (Citation2014), dialogue is at the foundation of any trust relationship. Trust necessarily involves two-way communication, where trustors are listened to and the trustee demonstrates that they have listened. Dobson explains that listening can be broken down into two different categories: cataphatic and apophatic. Cataphatic listening is a closed system, wherein the listener provides parameters for what they want to hear and are only capable of taking in what sits neatly within those parameters. Most surveys represent cataphatic listening. Traditional studio courses, where partners come in to frame a problem and then students solve for it, represent closed system listening because the questions asked are predefined. Apophatic listening, on the other hand, is an open system wherein the listener is seeking more structural input, perhaps even input into the questions themselves. This kind of listening signals to participants that the listener is open to reframing, and therefore can create the conditions for trust. Critical making practices embedded within institutions necessitate open ended listening, because they require investment from both the listener and the listened to.

Expression is widely recognised as evidence of critical thinking. It represents the consolidation of ideas into a form of speech (verbal, written, visual, etc.) that can be shared with others. Colleges are quite effective at building and maintaining the infrastructure that supports expression through the traditional classroom, individual assessment, and outputs such as tests, papers, and projects. In collaborative critical making, expression is a shared creative process. Building upon a foundation of listening, and supported by shared decision-making, makers work collaboratively to externalise learning through various forms of expression and storytelling, aimed at social, political, or institutional change.

Connected to expression and listening is governance, which includes the infrastructure for how decisions get made. For critical making to be collaborative, it requires structures of decision-making that are non-hierarchical and distributed across stakeholders. Ansell and Gash (Citation2007) define collaborative governance as: ‘A governing arrangement where one or more public agencies directly engage non-state stakeholders in a collective decision-making process that is formal, consensus-oriented, and deliberative and that aims to make or implement public policy or manage public programs or assets’ (544). Since the publication of Ansell and Gash’s seminal paper, scholars have extended the concept of collaborative governance to a variety of other institutional settings, including higher education (Campanella et al. Citation2022). What matters is what Ansell and Gash call the ‘sweet reward’ of collaborative governance, wherein the ‘high costs of adversarial policy making’ are reduced by bringing stakeholders into the process early (561).

In below, we represent how listening, expression, and governance are manifested at three different scales in the critical making process.

Table 1. Representation of the infrastructuring of the three dimensions of critical making at the scales of classroom, college, and community in the liberal arts.

5.1. Classroom

For collaborative critical making to be effective within the classroom, there needs to be space for listening, expression, and governance. TNGV adopts a studio model in the classroom, which foregrounds listening, necessitates a culminating artefact in the critical process, and assures that the artefact be collaboratively produced and owned. Studios are rather common in art and design schools and architecture schools, but far less common in the liberal arts (Middlebrook and Maines Citation2016). Each SIS connected to TNGV involves ‘learning partners’, external participants who have direct experience with the topic. Learning partners become full members of the classroom community with the traditional college students.

5.1.1. Listening in the classroom

Each SIS is structured around apophatic listening to build a foundation for relationships and trust. In Fall 2022, we facilitated a Virtual Reality Studio in partnership with the Louis D. Brown Peace Institute, one of this initiative’s founding partners, which is devoted to healing in the aftermath of gun violence. Several survivors of gun-related homicide victims, namely mothers whose child(ren) had been killed, participated as learning partners. The goal of the class was to use virtual reality as a tool to support healing among survivors. To cultivate a foundation of mutual trust, the professor facilitated an important, early listening activity, in which students and learning partners were encouraged to share hopes and concerns about the class, while also mapping out assets and strengths of each individual involved. This activity surfaced concerns of both the students and learning partners and created a safe space to work through them. In one example, a student expressed fear of unintentionally offending the learning partners, who differed from him in almost every way, including age, gender, lived experience, and race, by saying ‘the wrong thing’. One of the survivors responded with compassion and gratitude, encouraging the student’s bravery, and a promise to provide honest feedback coupled with grace as they continued to build trust and understanding of one another. As the honest discussions continued, the group was able to establish a set of written expectations about building a culture of safety and inclusivity. This exploration and articulation of positionality, expression of vulnerability, and willingness to listen for understanding, laid a critical foundation for the survivors to open up and share their personal experiences, for students to ask questions, and to begin moving together towards expression. This experience resonates with Bendiner-Viani’s (Citation2019) cautionary tale of a class at the New School in New York City where students in a collaborative class project with a community partner felt paralysed to act because they felt the stakes were too high, and that the students were not the appropriate people to act. That the students in the VR studio were able to find common ground with the learning partner represents structures within the classroom to support this kind of expression (see ).

Image 1. The outcome of the VR studio was a virtual rendition of Peace Play in Urban Settings, a therapeutic activity adapted by the Louis D. Brown Peace Institute to promote healing.

5.1.2. Expression in the classroom

Expression in the classroom, in the case of collaborative critical making, is not about individual assimilation of ideas, but rather collaborative creation to achieve an agreed upon outcome. In Fall 2022, we offered a SIS in game design. The Game Design Studio was in partnership with The Center for Teen Empowerment, a large youth-serving organisation that provides training for youth organisers and activists to seek change in a variety of issues, including gun violence. Four young adults and one staff member from Teen Empowerment, as well as a research assistant from MGH, joined as learning partners with 12 traditional college students. Though all were around the same age, learning partners and students represented vast differences in lived experience. After listening to diverse experiences in the class and learning more about how the issue of gun violence impacts young people, the class collectively decided to create a role playing game for youth-led violence prevention work. The class broke up into teams based on creative skills, each leveraging their own skills towards the greater goal of creating a game. The life experiences of the youth, as well as their knowledge of youth organising, and individual artistic talents balanced the college students’ skills in writing, media, and design. Each person had a valuable role to play in the collective creation of the final game, titled Piece or Peace?. Designed for teenagers, the game was about decision-making in the aftermath of violence. It debuted at an end-of-semester event where it was played by an intergenerational group of about 50 people (see ). It has since been adapted for use by the organisation in their own engagement with teenagers.

Image 2. Piece or Peace?, a role playing game about violence escalation designed for teens.

Students are used to having complete autonomy over their creative work. Within the collaborative context of SIS, they need to consider how their own choices of creative expression affects others, and at times they are challenged to cede creative authority to others. This can be met with resistance. In the fall 2023 Theatre Studio, students wanted to perform a piece about their own experiences of school shooting drills at the end-of-semester TNGV event. A learning partner raised concerns to the faculty that it would perpetuate dominant narratives that prioritise concerns about mass shootings that account for less than 1% of gun deaths in the United States, and continue to silence the experiences of Black and brown survivors of community violence. Incidents like this put faculty in challenging positions to weigh conflicting values – students’ agency in their creative work and desires of learning partners rooted in lived experience. Ultimately the professor was able to facilitate a conversation among learning partners and a student to reach agreement about how to move forward, but it required much consultation with the Engagement Lab and others and many unanticipated hours outside of typical class expectations. In the end, some students and partners may still have been upset.

5.1.3. Governance in the classroom

The dimensions of listening and expression are further supported by structures of shared governance in the classroom. While students can typically expect to have uncontested agency over their creative process and ownership of their creative outputs, SIS necessitate shared decision making and ownership so that what is created most accurately reflects the lived realities of gun violence, and the artefacts created are widely accessible and distributable to achieve the initiative’s impact goals. With this in mind, each SIS establishes expectations and practices around decision making to govern the creative process and use of the artefacts. This is a big adjustment for some, if not most, students, who are used to being sole proprietors of projects. However, through the process of listening and collaborative expression, students begin to understand the value of shared ownership, especially for the goal of social impact. In Spring 2022, the first semester of the initiative, we facilitated a Collaborative Documentary class with the Louis D. Brown Peace Institute. The studio included four learning partners: two mothers whose sons had been murdered, a woman on staff at the organisation, and a participant from MGH. The class was carefully structured to build trust and a shared sense of mission among learning partners and traditional college students. This foundation allowed the class to work collaboratively in production and post-production, carefully and considerately sharing editorial and decision-making power, to represent in process and product the vulnerable experiences of loss and healing. The class eventually produced a powerful 20-minute documentary, Quiet Rooms (2022), that has been broadly screened at local hospitals, city government, a prison, community-based organisations, local and national conferences, and medical education trainings across the country (see ). This wide distribution is only possible because of mutual agreement of all those involved to forgo personal ownership for the collective. Each person in that class has expressed a deep sense of pride for the film and the process through which it was produced, including the mothers. Both mothers have served on panels following screenings of the film, and one now even identifies herself as a documentarian. The students, still able to share the film as part of their personal creative portfolios, express appreciation for the much bigger story of informed co-creation.

Image 3. Students, faculty, and learning partners on the set of Quiet Rooms.

5.2. College

The practice of critical making in the classroom is further supported by infastructuring at the college level. Although we’ve seen critical making have a profound impact on students and learning partners in the classroom, it can still be an isolated experience, limited by the constraints of the academic semester. In order to address the constraints of the classroom – time, commitment, expectations, and resources – we have developed infrastructure at the college level, also reflecting all three dimensions of critical making: listening, expression, and governance.

5.2.1. Listening at the college level

From the very start of the initiative, TNGV has been dependent on structures of listening outside of the classroom. In the beginning, leaders from the Engagement Lab, MGH, and LDBPI met weekly to form a shared sense of mission, to identify narrative change goals, and to develop supportive structures for the initiative. These meetings became sacred spaces of learning how to listen to one another and grow in care and understanding. We spent time listening to leaders from the community recount experiences with researchers and higher education institutions where they felt that their knowledge and experience was exploited for the benefits of others, while receiving nothing in return. Chéry in particular challenged the team to think critically about sustainability before making promises to LDBPI or other community-based organisations. This listening was hugely influential in how we began talking about the issue of gun violence as a community, questioning our own stigmatising language (victim vs. survivor, for example), or misplaced focus (violence vs. peace), and how we designed each studio course. For example, following the admonition from Chéry to ‘stop feeding the problem’, we adopted the organisation’s principles of peace as our own guiding principles, shifting focus away from the gun towards what is required for peace. These principles were incorporated into the initiative’s meeting rituals and also became foundational for several TNGV studios and events.

5.2.2. Expression at the college level

The process of getting classes approved by curriculum committees across multiple departments is not straightforward. In each instance, we have had to justify the studios’ connection to the liberal arts or to the specific discipline and make the case that a collaborative production can have meaningful individual learning outcomes.

Additionally, we had to build supports for students and faculty to participate in this unique experience. We quickly learned that students were not adequately prepared to engage in critical making at the start of the semester, nor were many faculty. At the Engagement Lab, we created a core methods course for students that introduced them to the theory and practice of collaborative work prior to them directly interfacing with community partners. We also developed a fellowship programme for faculty to provide a place to share resources and challenges. Each of these infrastructural changes corresponded with existing structures in the college (courses and fellowships). But because they were utilised to reframe the emphasis on individualised expression, they were met with predictable resistance from the registrar’s office and from some department heads. Responding to this resistance was of course influential in the ultimate shape of the programmes and how they were shared with the campus community.

5.2.3. Governance at the college level

Creating systems that enable community partners to have some decision-making authority in curricular decisions is complex. Any effective governance structure requires that partners stay involved for longer than a single semester. To facilitate this, we directed resources to partner organisations to support their participation for a year (from July to June). This longer term commitment made it possible for organisations to justify their time pre and post semester, and provide some structure for them to participate in shaping new courses or identifying desirable outcomes. This is complicated by the fact that the learning partners in the studios are sometimes not the leaders of the partner organisations. But they are equally important to keep engaged in the critical making process. What started as a weekly meeting of the three original partners, eventually grew to a Collaborative Leadership Team (CLT) with representatives from all the partner organisations, MGH, faculty, staff, students, and other key community leaders. The CLT meets monthly and collectively defines and monitors the goals of the initiative, guides the direction of studios, and supports the distribution of outputs created through the studios. Within the CLT, which SIS should be offered each semester is decided, who the partner organisations should be, how events should be organised, and how outputs from the studios should be distributed and used for greatest impact.

With a commitment to inclusive representation in the governance structure, as additional partner organisations and faculty are added to the initiative, the CLT continues to grow in size. This poses challenges to efficiency, clarity of vision, and decision making. Each organisation has its mission and methods outside of TNGV, which are most of the time complementary, but occasionally conflicting. These conflicting perspectives can prove challenging at times. These challenges can result in decisions ultimately being made by the Engagement Lab in consultation with others, rather than truly collaboratively. Moving forward the team will have to consider alternative structures to efficiently make decisions within a collaborative governance structure.

5.3. Community

Given the highly collaborative model, it is important to consider the three dimensions of collaborative critical making in our interactions in and with the broader community as well. Critical making within TNGV necessitates activity beyond the confines of the classroom and even the college. Geographically, most of our community-based partners are located within certain neighbourhoods of Boston, miles from the college’s campus, where communities are disproportionately impacted by gun violence.

5.3.1. Listening in community

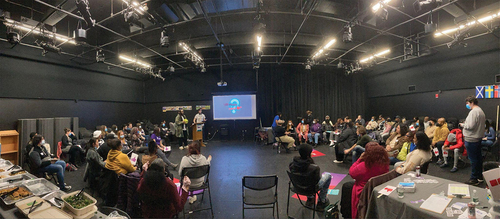

In addition to structuring listening for learning partners and students within the classroom, we also structured listening in the community, on the community partners’ terms. This happened through regular class visits to community spaces, organised by the partner organisations (see ). While colleges have extremely rigid schedules with time and space restrictions for students, it was important that we flexed as much as possible to bring students and faculty into a situation where they were not simply listening to, but listening within the community. Most of the studios in the initiative are offered once a week from 4-8 pm in order to accommodate community partners, who have included working adults and high school students. Additionally, taking advantage of the long class period, many of the studios met regularly off campus in community spaces. This approach ensured that learning partners were not always coming to academia, but the college was also going to community. These structures created safety and comfort for learning partners and guests, and resulted in more openness to share. It also provided the opportunity for students to ‘listen’ more broadly to the community, through observation and direct engagement with the organisations and the physical neighbourhood in which they were located. Students experienced public transportation, observed neighbourhood art, walked the streets, and ate local food, all of which built meaningful context for expression.

Image 4. Students listening to learning partners in the Dorchester community while on a tour.

This doesn’t come without challenges. Although most of the partner organisations are located within 5–6 miles from campus, public transportation to these neighbourhoods is not always direct. Experiencing these entrenched barriers is important; still, inefficient and unreliable transportation can eat away at the limited class time, causing frustration for students and learning partners. Additionally, real or perceived safety threats of visiting neighbourhoods off-campus has raised concerns for faculty and students.

5.3.2. Expression in community

From the beginning of the initiative, we offered a small stipend to learning partners for their participation in studios. Early on the question of credit was raised. After much advocacy to the College, we were able to create a free, 4-credit, 200 level course called ‘Creative Civic Engagement’, through the professional studies department. The course was designed so that credits could be transferred to most two and four year institutions in the case that learning partners desire to continue their education elsewhere. This helps to address the unequal dynamic of students and partners in the classroom because with this model, partners have access to campus buildings, the learning management system (Canvas), and are held to account for assignments. This also changed the “problem framing’’ dynamic that is common in other studio courses with community partners. Too often, in those contexts, the partner comes in a few times during the semester, frames the problem, provides some background and inspiration, and then comes in at the end to see what the students came up with. In our model, the partners are present all semester, working collaboratively with students, to produce a shared artefact, not an artefact for another’s use. When the semester is over, we continue to work with learning partners and partner organisations to determine how the artefact is used. We continue to meet with partners after the semester and support the ongoing work of students through mechanisms such as a co-curricular or student internships, sometimes paid by the Engagement Lab or MGH.

5.3.3. Governance in community

There are many decisions to be made about how to take a product to completion, who should be involved, how it gets used and evaluated, etc. The Collaborative Leadership Team (CLT) is where those decisions are made. Partners are compensated for their involvement in the CLT, and we consistently check in with them to make sure that the procedures we devised are fair and responsive. Additionally, we consider the CLT to be an important structure for distributing and promoting the use of artefacts in the broader community. In this capacity, partner organisations have initiated TNGV media screenings, helped plan events to share TNGV artefacts, and identified additional partners to bring into the initiative. Quiet Rooms, the documentary film created in the first semester of the initiative, has inspired MGH to invest resources in the redesign of the actual quiet room, the family waiting area inside the emergency department. As represented in the film, this cold, nondescript room is where families experience the worst day of their lives. The coalition of community, academic, and hospital partners within TNGV successfully used the film to convince the hospital to invest in this simple, yet essential renovation (see ).

Image 5. Doctors and survivors discussing the renovation of MGH’s quiet room in fall 2023.

At times, ownership of the artefacts and decisions related to their completion and distribution can be complicated. During the fall 2023 Collaborative Documentary Studio, learning partners and students alike developed a deep sense of ownership of the film that was produced about and alongside men working to disrupt violence in the community. Some individuals have expressed desire to take the footage and continue working on the film apart from the collaborative structures developed at the college. Although this deep sense of ownership is a desired outcome, it has the potential to conflict with other values of the initiative, such as collaborative governance.

6. Conclusions

Collaborative critical making is the externalisation of multiperspectivalism. It is a participatory design process that is distinctly oriented around shared creation. As we have tried to demonstrate, it requires significant infrastructural supports, and a reframing of the competitive individualism that has long nurtured critical thinking. Critical thinking is the internal assimilation of diverse perspectives with the goal of reasoned conclusions; its outcomes are evaluated on the level of the individual learner. Critical making externalises that process to the social world, and can be engaged and collaborative, with the goal of producing practical forms of knowledge and action through object production. We have described the case of TNGV, which is a campus wide storytelling initiative where students and partners work collaboratively to generate narrative interventions across media and genres. TNGV, as a case study of the infrastructuring of collaborative critical making, we examine the infrastructure across three dimensions: listening, expression, and governance; and across three scales: classroom, college, and community. Instead of examining critical making on its own terms, or the studio outcomes on their own terms, we make the case that we need to look deeply at the infrastructure that supports both.

In this description, we stop short of discussing the ongoing process to evaluate the effectiveness of TNGV to enhance student learning, and to achieve specific social impact. Future empirical research should build on the framework of collaborative critical making in higher education, and should seek to compare traditional student learning outcomes with outcomes that are unique to the making process. Additionally, research should look to correlate the process and products associated with critical making to specific social impact outcomes. For now, the infrastructure required for critical making represents the necessary reorganisation of higher education institutions so that they may be positioned to prepare students and partners to address society’s most urgent challenges.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the students, faculty, and learning partners that have participated in the initiative. This work can be very difficult. Learning partners have made themselves vulnerable by showing up on a college campus and sharing details of their lives; faculty have agreed to step outside of their comfort zones; and students have trusted the process enough to do things differently. We are grateful for the trust that each of them has given us. Additionally, we would like to thank Emerson College and Massachusetts General Hospital for their belief in the process. And we would like to thank the Stavros Niarchos Foundation and the Davis Educational Trust for their financial support and partnership.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ansell, C., and A. Gash. 2007. “Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18 (4): 543–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum032.

- Barcham, M. 2023. “Towards a Radically Inclusive Design – Indigenous Story-Telling As Codesign Methodology.” CoDesign 19 (1): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2021.1982989.

- Bendiner-Viani, G. 2019. Contested City: Art and Public History As Mediation at New York’s Seward Park Urban Renewal Area. Ames, IA: University of Iowa Press.

- Bødker, S., C. Dindler, O. S. Iversen, and R. C. Smith. 2022. Participatory Design. New York: Springer Nature.

- Bødker, S., and M. Kyng. 2018. “Participatory Design That Matters—Facing the Big Issues.” ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI) 25:1. https://doi.org/10.1145/3152421.

- Busch, O. V. 2022. Making Trouble: Design and Material Activism. New York: Bloomsbury.

- Campanella, M., B. Kirshner, J. Mendy, M. Landa-Posas, K. Terrazas Hoover, S. Lopez, L.-E. Porras-Holguin, and M. Estrada Martin. 2022. “Co-Construction Knowledge for Action in Research Practice Partnerships.” Social Sciences 11 (3): 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11030140.

- Charney, D. 2011. Power of Making. London: V&A Publishing and Crafts Council. http://conceptlab.com/criticalmaking/PDFs/CriticalMaking2012Hertz-Manifestos-pp01to06-Charny-PowerOfMaking.pdf.

- Costanza-Chock, S. 2020. Design Justice. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- DiSalvo, C. 2022. Design As Democratic Inquiry: Putting Experimental Civics into Practice. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Dobson, A. 2014. Listening for Democracy: Recognition, Representation, Reconciliation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- DuBois, W. E. B. 1957. The Education of Black People: Ten Critiques, 1906–1960. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

- Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence and Coalition to Stop Gun Violence. 2021. “A Public Health Crisis Decades in the Making: A Review of 2019 CDC Gun Mortality Data.” http://efsgv.org/2019CDCdata.

- Emerson, R. W. 2024. The American Scholar: An Oration delivered before the Phi Beta Kappa Society, at Cambridge, August 31, 1837. Accessed March 13, 2024. https://emersoncentral.com/texts/nature-addresses-lectures/addresses/the-american-scholar/.

- Fitzpatrick, K. 2019. Generous Thinking: A Radical Approach to Changing the University. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

- Freire, P. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum.

- Friess, E. 2010. “The Sword of Data: Does Human-Centered Design Fulfill Its Rhetorical Responsibility?” Design Issues 26 (3): 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00028.

- Gautam, A., and D. Tatar. 2020. “P for Political: Participation without Agency Is Not Enough.” In Proceedings of the 16th Participatory Design Conference 2020 - Participation(s) Otherwise - Volume 2, 45–49. Manizales Colombia: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3384772.3385142.

- Glaser, E. M. 1941. “An Experiment in the Development of Critical Thinking.” Masters Thesis, New York: Columbia Teachers College.

- Gordon, E., and G. Mugar. 2020. Meaningful Inefficiencies: Civic Design in an Age of Digital Expediency. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Haber, J. 2020. Critical Thinking. MIT Press Essential Knowledge Series. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Hector, P., and A. Botero. 2022. “Generative Repair: Everyday Infrastructuring Between DIY Citizen Initiatives and Institutional Arrangements.” CoDesign 18 (4): 399–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2021.1912778.

- Helmke, G., and S. Levitsky. 2004. “Informal Institutions and Comparative Politics: A Research Agenda.” Perspectives on Politics 2 (4): 725–740. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592704040472.

- Hertz, G. 2012. “Critical Making.” self published. http://conceptlab.com/criticalmaking/PDFs/CriticalMaking2012Hertz-Introduction-pp01to10-Hertz-MakingCriticalMaking.pdf.

- Hertz, G. 2023. Art + DIY. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Huybrechts, L., H. Benesch, and J. Geib. 2017. “Institutioning: Participatory Design, Co-Design and the Public Realm.” CoDesign 13 (3): 148–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2017.1355006.

- Jalbert, K. 2016. “Building Knowledge Infrastructures for Empowerment: A Study of Grassroots Water Monitoring Networks in the Marcellus Shale.” Science and Technology Studies 29 (2): 26–43. https://doi.org/10.23987/sts.55740.

- Jankowski, N., and K. Jensen eds. 1991. A Handbook of Qualitative Methodologies for Mass Communication Research. Routledge.

- Karasti, H., and J. Blomberg. 2018. “Studying Infrastructuring Ethnographically.” Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) 27 (2): 233–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-017-9296-7.

- Korn, M., R. Wolfgang, R. Tobias, and S. David. 2019. “Infrastructuring Publics: A Research Perspective.” In Infrastructuring Publics, edited by M. Korn, W. Reißmann, T. Röhl, and D. Sittler, 11–47. Medien Der Kooperation. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-20725-0_2.

- Massachusetts Gun Deaths: 2019. 2019. “The Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence.” https://efsgv.org/state/massachusetts/.

- Matthews, B., S. Doherty, P. Worthy, and J. Reid. 2023. “Design Thinking, Wicked Problems and Institutioning Change: A Case Study.” CoDesign 19 (3): 177–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2022.2034885.

- Middlebrook, J., and K. Maines. 2016. “The Introductory Architecture Studio Revisited: Exploring the Educational Potential of Design-Build within a Liberal Arts Context.” Journal of Architectural Education 70 (1): 154–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/10464883.2016.1122494.

- Mitchell, T. D. 2008. “Traditional Vs. Critical Service-Learning: Engaging the Literature to Differentiate Two Models.” Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning 14 (2): 50–65. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/mjcsl/3239521.0014.2*?g=mjcslg;rgn=full+text;xc=1.

- Mitchell, T. D., D. M. Donahue, and C. Young-Law. 2012. “Service Learning As a Pedagogy of Whiteness.” Equity & Excellence in Education 45 (4): 612–629. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2012.715534.

- Morsy, L., and R. Rothstein. 2016. “Mass Incarceration and Children’s Outcomes: Criminal Justice Policy Is Education Policy.” Economic Policy Institute. December 15, 2016. https://www.epi.org/publication/mass-incarceration-and-childrens-outcomes/.

- Niewöhnr, J. 2015. “Infrastructures of Society.” In International Encylopedia of the Social and Behaviorial Sciences, edited by D. W. James, 119–125, Elsevier.

- Pipek, V., and V. Wulf. 2009. “Infrastructuring: Toward an Integrated Perspective on the Design and Use of Information Technology.” Journal of the Association for Information Systems 10 (5): 447–473. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00195.

- Ratto, M. 2011. “Critical Making: Conceptual and Material Studies in Technology and Social Life.” The Information Society 27 (4): 252–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2011.583819.

- Salam, M., D. Nurfatimah Awang Iskandar, D. Hanani Abang Ibrahim, and M. Shoaib Farooq. 2019. “Service Learning in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review.” Asia Pacific Education Review 20 (4): 573–593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-019-09580-6.

- Serpa, B., I. Portela, M. Costard, and S. Batista. 2020. “Political-Pedagogical Contributions to Participatory Design from Paulo Freire.” In Proceedings of the 16th Participatory Design Conference 2020 - Participation(s) Otherwise -Traditional vs. Critical Service-Learning: Engaging the Literature to Differentiate Two Models Volume 2, 170–174. Manizales Colombia: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3384772.3385149.

- Song, Z., J. R. Zubizarreta, M. Giuriato, K. A. Koh, and C. A. Sacks. 2023. “Firearm Injuries in Children and Adolescents: Health and Economic Consequences Among Survivors and Family Members.” Health Affairs 42 (11): 1541–1550. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2023.00587.

- Star, S. L., and G. Bowker. 2002. “How to Infrastructure.” In Handbook of New Media: Social Shaping and Social Consequences of ICTs, edited by L. Lievrouw and S. Livingston, 151–162. London: Sage.

- Still, B., and K. Crane. 2017. Fundamentals of User-Centered Design: A Practical Approach. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Streeck, W., and K. Thelen. 2005. Beyond Continuity Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Workbook: BPD Shots Fired Dashboard. 2022. Boston.gov. 2022. https://dashboard.boston.gov/t/Guest_Access_Enabled/views/ShotsFiredDashboard_16244869752910/ShotsFiredDashboard?%3Adisplay_count=n&%3Aembed=y&%3AisGuestRedirectFromVizportal=y&%3Aorigin=viz_share_link&%3AshowAppBanner=false&%3AshowVizHome=n.

- Yin, R. 2017. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. 6th ed. New York: Sage.