ABSTRACT

This paper traces a walking tour of Cork City that I recently undertook, using an autoethnographic perspective to tap into the linguistic and semiotic features of places and spaces associated with the blues musician Rory Gallagher and how they are tied to specific music memories. To do this, I draw on the theory of semiotic landscapes, yet put forward the term semiotic musicscapes to account for the imagined, embodied and emotional aspects of the visual linguistic environment that such music walks entail. I argue that these forms of secular pilgrimage turn the ‘ordinary’ into the ‘extraordinary’, relying on both specialised music knowledge and the imaginarium to make true meaning from visual and verbal signs. The paper, thus, offers a new way for ethnomusicologists to explore the cultural geography of music, as well as for (socio)linguists to approach the study of semiotic landscapes, particularly when tied up with musical heritage. It also extends current scholarship on Rory Gallagher whose life and work remain underresearched, despite his importance as a founding figure of Irish rock music.

This is the most fantastic honour. It’s better than a number one album in America or anywhere in the world: to be number one in Cork.

Walking is known to have many benefits, both from a physical and mental perspective. It can improve cardiovascular fitness, strengthen bones and boost muscle power, as well as alleviate stress, reduce anxiety and support positive mood (Kelly et al. Citation2017). Music walks – that is, walks linked to a particular musician or band, whether done independently or as part of an arranged tour – have additional benefits. As fans visit cityscapes and engage with their seven senses, they undertake a complex performance that enables them to foster new connections with their favourite musician/band, (re)create narratives of place and construct intra- and interpersonal authenticity (Johinke Citation2018). Bolderman and Reijnders (Citation2016) see such walks as ‘embodied social practice[s]’ because they enable personal memories and cultural identities to be negotiated and performed.

In this paper, I trace the walk of Rory Gallagher’s Cork that I took on 26 July 2022, using an autoethnographic perspective to tap into the linguistic and semiotic features of place and space and how they are tied to specific music memories. To do this, I draw on the theory of semiotic landscapes (Jaworski and Thurlow Citation2010), yet put forward the term semiotic musicscapes to account for the imagined, embodied and emotional aspects of the visual linguistic environment that such music walks entail. I argue that these forms of secular pilgrimage turn the ‘ordinary’ into the ‘extraordinary’, relying on both specialised music knowledge and the imaginarium to make true meaning from visual and verbal signs. They demonstrate that musical heritage is never static and involves a heteroglossic relationship with other fans and artefacts in a city’s musicscape. The paper, thus, offers a new way for ethnomusicologists to explore the cultural geography of music, as well as for (socio)linguists to approach the study of semiotic landscapes, particularly when tied up with musical heritage. It also extends current scholarship on Rory Gallagher whose life and work remain underresearched, despite his importance as a ‘founding figure of Irish rock music’ (Embassy of Ireland Citation2014).

Places, spaces and musical traces: an overview

Since the late 1990s, the field of ethnomusicology has given growing attention to the cultural geography of music. Works by Swiss et al. (Citation1998), Leyshon et al. (Citation1998) and Connell and Gibson (Citation2003) paved the way into recognising the value of applying geographical theorisations to popular music. Henceforth, there have been a range of diverse studies in the area, which Lashua et al. (Citation2014) have divided into three main research trajectories: (1) sonic environments and performance; (2) economic geography; and (3) spaces, places and identities. Sonic environments and performance refer to the way that space is made through sound and how music specifically offers an insight into the soundworld of a place. Economic geography, on the other hand, is concerned with commercial music activities, such as music festivals, urban regeneration schemes and the role of cultural industries. Spaces, places and identities – which is the focus of the current paper – instead considers social and emotional ‘place attachment’ in the context of music and how this is tied up with discourses of identity, authenticity and belonging for people who live in or visit a particular place. It also considers how navigating a city associated with a particular musician or music genre has a strong impact on the practices, relationships and values of its inhabitants/visitors, which is often transmitted from generation to generation through cultural production.

In terms of spaces, places and identities, early standout studies include ethnographies of music-making and identity in Milton Keynes (Finnegan Citation1989), Liverpool (Cohen Citation1991),Footnote3 Austin (Shank Citation1994), Singapore (Kong Citation1995) and Newcastle (Bennett Citation1999). Building upon these studies, more recent research has focused on the unique music scenes and heritage of such cities as Montreal (Stahl Citation2004), Lisbon (de la Barre Citation2010), Sheffield (Long Citation2014), Reykjavik (Prior Citation2015), Cork (Hogan Citation2016, Citation2021) and Dublin (O’Flynn and Mangaoang Citation2019).

Some researchers, on the other hand, have turned to more tangible markers of music heritage. Bennett (Citation2016), for example, has explored the mythology of Abbey Road, while Kruse (Citation2003) has investigated Strawberry Fields as a place of pilgrimage. Equally, Doss (Citation2018) has focused on rituals and religiosity at Graceland and Bolderman and Reijnders (Citation2016) have turned to tourist experiences in Wagner’s Bayreuth, ABBA’s Stockholm and U2’s Dublin. Roberts and Cohen (Citation2014a, Citation2014b) instead have concentrated on commemorative plaques. This forms a core chapter of their groundbreaking edited volume Sites of Popular Music Heritage, which offers an interdisciplinary perspective on the location of memories and histories of popular music. Although still a growing area of research, others have turned their attention to music walks, such as Johinke (Citation2018) who documented punk walking tours in New York City and Osborne (Citation2019) who outlined the complexities of walking Bob Marley’s Trench Town. A focus on music walks – particularly when self-guided – has the potential to reveal new insights into how people interact with the spaces that they encounter and make sense of a city’s rich musical heritage. These insights can be especially fruitful when viewed through the lens of semiotic landscapes.

From semiotic landscapes to semiotic musicscapes

The fields of Sociolinguistics and Discourse Studies have always been concerned with how spaces are filled with sociocultural meanings that transform them into places (Lou Citation2017). Scholars argue that the linguistic landscape plays a key role in this process, defined by Landry and Bourhis (Citation1997: 23) as the ‘visibility and salience of languages on public and commercial signs in a given territory or region’. Much research on linguistic landscapes has been interested in multilingual signs in order to assess how languages are visually displayed and hierarchised in multilingual societies (e.g. Leeman and Modan Citation2009; Malinowski Citation2009; Peck and Banda Citation2014). The term ‘linguistic landscape’ was extended by Jaworski and Thurlow (Citation2010) to ‘semiotic landscape’ in order to recognise other modes of communication and the way that non-linguistic features (e.g. image, colour, typography, texture, layout) imbue public spaces with sociocultural meanings. Essential to semiotic landscapes is the idea that communication is always historicised and contextualised. In other words, the meaning of spaces cannot be correctly understood if knowledge of their sociocultural and historical significance is lacking.

In theorising semiotic landscapes, Jaworski and Thurlow took inspiration from the work of Scollon and Scollon (Citation2003) on geosemiotics. Geosemiotics offers a framework to interpret signs in the geography of a place and how their linguistic and semiotic structures are tied up with broader discoursesFootnote4 in the physical world. Scollon and Scollon’s (Citation2003) framework conceptualises semiotic landscapes into three main semiotic systems: (1) interaction order; (2) visual semiotics; and (3) place semiotics. Interaction order draws on the work of Goffman (Citation1981) and is concerned with embodied forms of discourse, i.e. social relationships and how we interact with and move through a space. Visual semiotics is inspired by Kress and van Leeuwen (Citation2006) and explores disembodied forms of discourse, namely the various signs within a space and how their linguistic and semiotic features work together to create multimodal meaning. Finally, place semiotics (coined by Scollon and Scollon) investigates the indexicality of discourses in time and space. When interpreting a semiotic landscape, all three semiotic systems operate as an aggregate, integrating ‘to form the meaning which we call place’ (12). However, it is important to point out that one aspect may be more salient than another according to the type of interaction/sign/space. This framework has since been refined by Lou (Citation2017) and Holmberg (Citation2021), amongst others, and offers a good guiding principle for the interpretation of semiotic landscapes.

There are various ways to explore a semiotic landscape. Hult (Citation2014), for example, trialled a drive-thru method on a busy highway, while McIlvenny (Citation2015) used mobile video ethnography on a bike ride. However, to fully engage with a space, walking is often seen as the best method. Various types of walking have been put forward by scholars depending on the aims of their research. Bates and Rhys-Taylor (Citation2017) recommend walking interviews, Kusenbach (Citation2003) has used ‘go-alongs’ (i.e. shadowing others as they walk around a place), Anderson (Citation2004) has engaged in ‘bimbles’ (i.e. leisurely walking and talking through the countryside), Stroud and Jegels (Citation2015) have undertaken narrated walks, Pink (Citation2015) has used sensory walks, Heddon and Turner (Citation2010) have employed walking art and Wylie (Citation2005) has advocated lone walking. Lone walking is the method that I adopted for my study in order to foster an autoethnographic perspective of Rory Gallagher’s Cork.

Autoethnography is a qualitative research method that aims to ‘describe and systematically analyse personal experience in order to understand cultural experience’ (Ellis et al. Citation2010). When applied to walking and semiotic landscapes, autoethnography enables walkers to use their own experience to ‘bend back’ on their self, resulting in a deeper understanding of the signs around them, their link to a particular musician/band and their resulting representations, cultural experiences and constructions of knowledge (Butz and Besio Citation2009). Surprisingly, most studies on the cultural geography of music tend to overlook this autoethnographic perspective, despite its ability to foster an awareness of the kinaesthetic experience of walking through a music space and the interaction between all seven senses to make meaning. It could, thus, offer a new method for exploring the relationship between music, spaces, places and cultural identity.

While some research on semiotic landscapes has considered the role of music (e.g. Backhaus Citation2007; Scarvaglieri et al. Citation2013 on soundscape; Pennycook and Otsuji Citation2015 on scentscape; Prada Citation2023 on sensescape), most studies have tended to overlook the many ways in which it is embedded in our city streets. Furthermore, while sociolinguists have considered memorialisation in the semiotic landscape (e.g. Blackwood and Macalister Citation2019; Papen Citation2012), music memorialisation is seldom considered, preference instead given to historical and political monuments, museums and memories. With this in mind, when thinking about music walks, it can be helpful to extend the concept of semiotic landscapes to semiotic musicscapes to recognise the uniqueness of such spaces. Semiotic musicscapes accounts for the way that the places and spaces we encounter are all inherently tied up to specific musical memories that affect our interpretation of the linguistic and semiotic signs around us, while also allowing for the imagined, emotional and embodied processes that this can encompass. shows a semiotic musicscapes framework based on the work of Scollon and Scollon (Citation2003), Lou (Citation2017) and Holmberg (Citation2021), which acts as a heuristic guide for exploring Rory Gallagher’s Cork. ‘Interaction Order’ encompasses the type of interaction (e.g. silent reflection, conversation, photography/filming), whether the interaction took place offline or online, interpersonal distance, posture and movement through a space; sense of time and reading order (of a text/artefact). ‘Visual Semiotics’ splits down the various aspects of a sign into seven components: language, image, typography, colour, texture, layout/composition and modality, understood as ‘the truth value or credibility’ of signs (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006: 155). ‘Place Semiotics’ comprises emplacement (i.e. the physical location of a text/artefact), perceptual spaces (e.g. visual, auditory, olfactory, thermal, haptic), imagined spaces (i.e. past uses of space, evolving uses, removed texts/artefacts) and emotional spaces (i.e. personal feelings generated by the physicality in space). Central to the entire framework is the notion of embodiment as fans form bonds with their musical icons through both tangible and intangible signs of cultural heritage.

Table 1. A framework to study semiotic musicscapes based on Scollon and Scollon (Citation2003), Lou (Citation2017) and Holmberg (Citation2021).

On the trail of Rory Gallagher

Cork is the second largest city in the Republic of Ireland, located in the southernmost section of the country and boasting a population of roughly 222,000 inhabitants.Footnote5 The city began as a monastic settlement, founded by St Finbar in the sixth century. However, it developed into a large urban centre during the Viking era when a trading community was established (c. 915–922). This urban centre was built on a series of marshy islands positioned between two channels of the River Lee and still structures the city’s layout today. Its unique geography means that Cork is a relatively compact, flat and walkable city with a ‘small town’ feel (McCarthy Citation2016).

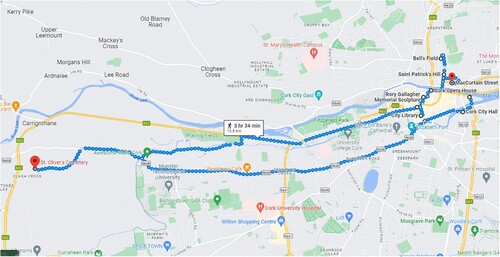

Many Corkonians, in fact, believe that the natural landscape of Cork has created a unique ‘people-place bond’ in terms of sense of community, which has spilt over into the city’s music (Hogan Citation2016, Citation2021). This social and emotional place attachment is strongly related to discourses of identity and belonging which, in turn, have a strong impact on local musicians (O’Hagan Citation2022a). Such feelings can also transfer over into the city’s semiotic musicscape and impact the people (particularly fans) who immerse themselves in such scenes, as I sought to find out in my walking tour of Rory Gallagher’s Cork on 26 July 2022 ().

8:30am St Oliver’s Cemetery

‘Nobody is perfect. However, being from Cork is close enough’, reads the framed picture on the wall opposite my bed in Jury’s Hotel on Anderson Quay. It is the first thing that I see when I wake up and it sets the tone perfectly for the reason that I am here in Cork, some 300 miles away from home: to embark upon a secular pilgrimage to my hero and role model, Rory Gallagher. Being Irish yet having grown up in England, I always feel an enormous sense of pride and nostalgia whenever I return to the Emerald Isle. Today, these feelings are heightened by the fact that I am not back in Ireland as a cousin or granddaughter visiting family in the north, but rather on my own terms as a Rory fan and devotee visiting, for the first time, a city that meant so much to him. The trip is also one of personal accomplishment, having struggled with significant mental health challenges over the past two years. The main thing that kept me afloat was Rory’s music and, thus, this trip was something that I knew I had to do to gain closure; to thank Rory personally and walk in his footsteps.

For the occasion, I dress in a calculated way: red and black check shirt, bolo tie, Levi Safari jeans, red Converse and black leather jacket – the clothes with which Rory himself was typically associated. Dressing like Rory not only offers me a source of comfort and protection as I embark on my journey (see O’Hagan Citation2022b), almost as if I am physically carrying him with me, but also takes on ‘magical’ properties, acting as a ‘costume’ that helps me express, emancipate and transform myself, both physically and mentally (see Chaney and Goulding Citation2016). I have not even yet set foot onto the streets of the city, but my pilgrimage has already begun, Jury’s Hotel being the site of the reception following Rory’s funeral on 19 June 1995. I think of this as I come down from my room to the lobby and observe the bar area, which I have so often seen in photographs from the sad occasion. I feel myself instinctively grip the bolo tie around my neck and stroke the black cowboy boot motif on its clasp, almost willing Rory to somehow grant me the strength to undertake this emotional journey. Given this poignant start to my day, I decide to continue on this note and head to my first port of call – St Oliver’s Cemetery – to pay my respects to Rory.

Located in Ballincollig roughly five miles from the city centre, St Oliver’s Cemetery is the furthest point on my tour. To save my legs, I decide to catch the bus, but even the short walk to the bus stop puts me in touch with Rory. I pass the imposing City Hall on Anglesea Street and think of the many times that he performed there with his band Taste in the late 1960s and then solo throughout the 1970s. I reflect also on the fact that it was the site of his first talent competition at age 12 in 1960, as well as the civic reception that he was granted with Lord Mayor Micheál Martin 32 years later in 1992 in recognition of his musical achievements. Dormant memories of Rory lie on every corner of the city, waiting to be reactivated by fans like me who visit.

As I step onto the bus and tell the driver my destination, I am surprised when he asks me if I am planning to visit Rory’s grave. I feel my cheeks flush, wondering if my attire gave me away. All I can do is nod foolishly as he continues, expressing his surprise that a young woman scarcely born when Rory passed away could be such a huge fan. I smile, wanting to say so much but ending up saying nothing at all as my shyness gets the better of me. I take a seat and await my stop. I am feeling nervous and, as usual, turn to Rory, slipping in my earphones and listening to the soothing acoustic sounds of Cleveland Calling. Half an hour later, the bus drops me off on Model Farm Road and I walk the brief distance to the cemetery. Its entrance is marked by two black metal gates flanked by stone pillars. On them sit two black plaques bearing the cemetery’s name in both Irish and English (). Irish has constitutional status as the first official language of the Republic of Ireland and it is enshrined in legislation that all official signage must be in both Irish and English.Footnote6 The bilingual language and Cork City Council’s coat of arms with its maritime symbology, thus, clearly establish an official ‘civic frame’ in the landscape tied up with the city’s rich history (Kallen Citation2010: 47). The signs are identical in style, with the same font, colour and information (albeit in different languages), creating a sense of symmetry, harmony and order.

When I enter the cemetery, I am immediately drawn to Rory’s grave, which stands out from all the others. While most headstones are in traditional polished stone, Rory’s is instead marked by five gold beams, which represent the Melody Maker Best Guitarist Award that he received in 1972 (). However, the beams’ orientation and gold hue also stand as representations of the sun and its associated connotations of hope, faith and eternal life (O’Hagan Citation2021a: 197). In fact, Rory had originally been buried in a different plot in the cemetery but, on his mother’s request, he was moved to a higher spot so that the sun could always shine on him. This is apparent today as, even through the overcast sky, flecks of light break through and bounce off the beams, casting a shimmering path over the grass. The beams are made of a solid metal, believed by Ledin and Machin (Citation2020: 162) to connote quality and durability. Of significance here is also the material’s reflectivity, which captures the images of both visitors and votive offerings, adding another layer of meaning. I run my hand over the beams, which are surprisingly cold to the touch, despite the warm summer morning. Yet, it is only through touch that the fifth beam reveals a secret: its contours feature a replica of the fretboard of Rory’s beloved 1961 Fender Stratocaster – the instrument that he bought when he was 15 years old and that he played throughout his career.

The plaque itself is more humble: a simple piece of dark grey stone with a small cross and ‘Rory Gallagher’ engraved in gold. To the left is a similar plaque for his mother Monica who is buried alongside. Rory’s grave features an array of votive offerings that act as a unique visual ‘heteroglossia’ (Bakhtin Citation1981), forming a shared dialogue between me and other fans. Being an active member of the Rory Gallagher online fan community, I recognise certain gifts and know who left them and when. I see a child’s toy guitar and yellow flowers left by Noe last February and a stencilled artwork of Rory left by Monique in June. I add to this dialogue with my own gifts: an Irish flag hand-knitted by my mother, a piece of artwork drawn by my friend Ellen, two poems written by me, a green neckerchief and ten white carnations in homage to an iconic Rory photograph from 1976.Footnote7 I also remove my bolo tie and hang it over one of the beams; the physical transfer of the item from my neck to Rory’s (figuratively) entails a process of ‘ensoulment’ (O’Hagan Citation2022b), transferring a small part of my own identity to him. The gifts sit alongside a range of other items that reflect different aspects of Rory, such as his music (plectrums, concert tickets, backstage passes, lyric sheets, song scores) and his clothing (neckerchiefs, bolo ties, fragments of check shirts), coupled with more traditional objects (candles, stones, flowers, Celtic crosses, photographs).

Harris (Citation2020: 144) claims that being in proximity to a deceased celebrity brings a ‘sense of credibility’ to the fan experience, enabling fans to explore their feelings about death in a safe space and enter into an imagined relationship with the person. This parasocial interaction establishes a ‘real-world connection’ (145), which was certainly the case for me. To my surprise, I find myself alone in the cemetery and am able to speak openly to Rory. I also pull out my MP3 player and listen to my favourite Rory song, ‘A Million Miles Away’, on repeat. ‘A Million Miles Away’ is often described as Rory’s theme song, and I too see it as my own. It is autobiographical, its lyrics speaking about being an outsider and feeling alone in a room full of people. Listening to ‘A Million Miles Away’ at Rory’s side is a deeply intimate and emotional experience, albeit tinged with a wistful irony: a song about loneliness somehow brings us together across the divide and created such a bond between Rory and I from the moment I first heard it. Needing to be alone with my thoughts, I leave the cemetery and walk the 2.6 miles to the Church of the Descent of the Holy Spirit where Rory’s funeral took place. It is not lost on me that this is the reverse journey that the hearse took, followed by over 2,000 people walking behind in a silent procession. As I walk, I am struck by something Thin Lizzy frontman Phil Lynott (in Clayton-Lea Citation1983) once said, ‘Once you’re Irish and Catholic, you’re always Irish and Catholic’, and today I understand his words. Despite being a lapsed Catholic, I feel a strong desire to enter this church, partially knowing how strong Rory’s Catholic faith was throughout his life, but also out of a desire for sanctuary and fortitude to continue my journey. So, I stop inside, light a candle and say a prayer, before continuing onto the city centre.

Again, my route is filled with memories. I pass Munster Technological University where Rory played an acoustic concert in 1993 in honour of his Uncle James Roche (once principal there); the lecture theatre in question now bears Rory’s name. Then, I walk through Fitzgerald Park and across its famous Shakey Bridge – both scenes immortalised in photographs by Liam Quigley and the 1972 Music Makers Rory documentary. I cannot resist recreating Rory’s poses and gait, almost as if replicating his physical movements enable me to embody him and experience Cork through his eyes. I feel self-conscious as I do so, however, wondering if passers-by will realise my ‘game’.

1:30pm Rory Gallagher Music Library

I reach Cork city centre along the Mardyke Walk and come out in Graftan Street. The city is alive now and a strange blend of smells fill the air: pub food, coffee, car fumes, cigarettes. Realising that I am close to St Augustine’s Roman Catholic Church, where Rory regularly attended mass, I decide to turn left into Washington Street and step inside. Again, the silence of the church offers momentary sanctuary from the hustle and bustle outside. I light another candle and say another prayer. However, when I hear the footsteps of the priest approaching, I take that as my cue to leave. Today is the most time I have spent in church(es) for years and I feel embarrassed to explain my reasons why. I head onto my main destination: the Rory Gallagher Music Library.

The Rory Gallagher Music Library is housed inside Cork City Library on Grand Parade. The City Library was a place that Rory visited often in his adolescence, spending hours studying guitar books. Thus, the building has dual significance, being a site that Rory himself regularly frequented and also now bearing his name. As I enter the library, I am struck immediately by the large red sign stating ‘Rory Gallagher Music Library’ () and I feel a fluttering of butterflies in my stomach. In fact, I start to blush and even self-consciously zip up my jacket in case someone spots my clothing underneath and identifies me as a fan. It is almost as if my choice of attire is my secret, my personal armour, and, thus, I do not want anybody else to see it and guess my reasons for wearing it.

I am surprised at just how much seeing Rory’s name emblazoned on a public building impacts me, and realise it is the fact that ‘Rory Gallagher’ is written in his own signature, which stands as a ‘personal hieroglyph’ (Sassoon Citation1999: 76) that is central to his identity and represents his character to the world. It also acts as a marker of authenticity, stamping the library with his seal of approval (O’Hagan Citation2021a: 218). Like the sign at St Oliver’s Cemetery, the library name is written in both Irish and English, thereby characterising it as part of the ‘civic frame’ (Kallen Citation2010: 47). Here, however, the font is a traditional Celtic style representative of an older orthographic system (Moriarty Citation2015), which is strongly tied up with national identity and frames Rory as distinctly Irish and a source of pride for his fellow countryfolk. According to Kress and van Leeuwen (Citation2002), colours often carry associative and symbolic qualities. In this case, the sign’s red and white represent the colours of Cork, historically chosen to symbolise the sandstone of the city’s northside and the limestone of its southside.Footnote8 For me, the red backdrop, coupled with gold lettering, also brings to mind the etymology of the name ‘Rory’: ‘red-haired King’. Although clearly not the creator’s intention, it shows how viewers will always draw upon their own sociocultural knowledge when interpreting signs (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006).

Other symbols in the semiotic musicscape act as accoutrements which, together, convey the library as a safe haven for Rory fans. Directly underneath the main entrance sign is a smaller rectangular sign signalling the way in with an arrow. On the right is a large freestanding sign, which shows a black and white image of Rory and his Stratocaster. Again, the red, white and gold library bilingual text features at its bottom, while a more official bilingual library logo sits in its top-right corner. To the left, on the other hand, is an easel displaying the poem ‘Hometown Blues’ written about Rory by Cork Poet Laureate, William Wall. The poem is printed in white on a hazy pink backdrop of City Hall, which visually projects a dreamlike aura that encapsulates the main message of the verbal accompaniment.Footnote9 Behind this is an iconic photograph of Rory on stage, again accompanied by the ‘Rory Gallagher Music Library’ text underneath in Irish and English.

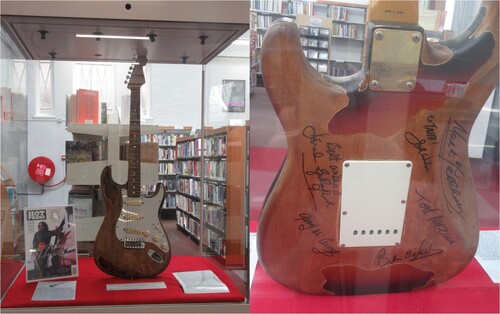

Before following the arrow inside, I am distracted by a glass case to my right displaying a replica of Rory’s Stratocaster () next to a special edition of Hot Press released on the 25th anniversary of Rory’s passing in 2020. As Ledin and Machin (Citation2020: 159) note, glass creates an impression of durability, transparency and honesty. Thus, seeing the guitar behind glass gives it an added significance, lifting it from the domain of rock concerts and placing it into a museum context, firmly embedding it in Cork’s musical history. Even in replica form, the display offers an opportunity to appreciate the unique semiotics of Rory’s guitar. Rory had a rare blood type, which meant that his sweat acted as a corrosive that stripped the paint off his guitar, essentially turning it into a piece of driftwood. Through extensive use over three decades, the guitar became perfectly shaped to his contours and embedded with the dye from his jeans.Footnote10 The replica attempts to reflect these worn qualities of the original Stratocaster in its sporadic patches of sunburst paint and chipped wood. While replicas can be considered inauthentic, Schwan and Dutz (Citation2020) have shown that they can, in fact, enhance visitor experience and knowledge of artefacts. In this instance, any worries about authenticity are lessened by the fact that the back of the guitar has been signed by Rory’s brother and manager Dónal, along with former band members Gerry McAvoy, Brendan O’Neill, Ted McKenna, Mark Feltham and John Wilson.

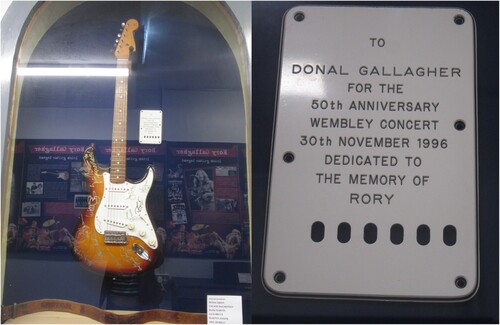

Finally entering the main Rory Gallagher Music Library, I am met with a mini permanent exhibition providing details of Rory’s career alongside a range of artefacts. Most museum visitors do not follow a linear route and tend to be guided by a ‘stumble upon’ approach as they see something that catches their eye (O’Hagan Citation2021b). This is certainly true in my case as I immediately head to another glass cabinet, this time displaying a Fender Stratocaster signed by all the musicians who took part in the 50th Anniversary Fender Stratocaster Concert in 1996, which was dedicated to Rory – major names such as Peter Green, Hank Marvin and Jack Bruce. But it is not the guitar itself to which I am drawn, but rather its backplate, which bears the inscription: ‘TO DONAL GALLAGHER FOR THE 50TH ANNIVERSARY WEMBLEY CONCERT 30TH NOVEMBER 1996 DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF RORY’ (). This is a moment that I have heard about many times from fans, but to see it encapsulated in a plaque is deeply moving. Nobody was closer to Rory than his brother Dónal. At the Fender concert in 1996, he was unexpectedly presented on stage with this guitar, which brought tears to his eyes. Knowing this broader sociocultural context gives added meaning to the artefact, thereby increasing its significance for Rory fans like me.

Another lump in my throat forms when I see Rory’s leather guitar strap at the bottom of the glass case, which he used regularly for a period in the early 1980s. The leather is worn and frayed, giving it timeless and authentic qualities, while his name is embossed in capital letters, calling to mind similar practices by old blues musicians and, thus, embedding him in the same canon. The glass case itself is shaped like a stained-glass window, which brings a quasi-spiritual edge to my encounter. Added to the spirituality is the library setting itself, which encourages silence and stillness as if in a church. As I look, I am attentive to the sound of my own breathing and heart beating, which accentuates this moment of reflection.

I pass up the chance to enter the archives and explore the Rory Gallagher collection in more depth. I already feel overcome by my encounter with the material artefacts I have seen and know that speaking aloud about Rory with staff will likely trigger my usual bashfulness, so I reluctantly leave.

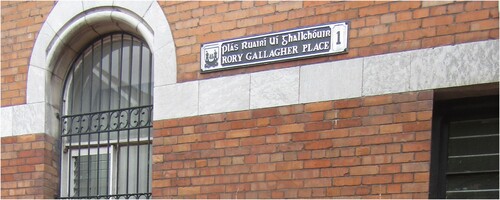

2:45pm Rory Gallagher Place

Fighting down a twinge of hunger (I have not eaten anything since 8:30am), I walk the short distance from the library to Paul Street where, tucked away amongst the narrow streets, sits Rory Gallagher Place. Originally called Paul Street Plaza, the square was renamed in 1997 when a sculpture was unveiled there in Rory’s honour. My first impression of the square is disappointment. I had been expecting something much grander, but it is rather underwhelming. A Tesco supermarket, Wetherspoon’s pub, e-cigarette shop and burrito café surround the square, while graffiti lines the walls and there is a strong smell of cigarettes and fast food. However, as soon as my gaze rests upon the sculpture and the street sign, my discomfort washes away.

The sculpture () sits to the left of the square on top of a stone plinth marked simply with the words ‘RORY GALLAGHER TRIBUTE’. According to Bellentani and Panico (Citation2016), stone is such a frequently used construction material that it does not directly communicate specific meanings; nonetheless, it is representative of a routinised pattern of construction. For Abousnnouga and Machin (Citation2013: 133), on the other hand, stone is tied up with longevity and ancientness. Therefore, when viewers see stone on memorials, they draw on their experiential associations of ancient buildings and tie it to longer religious and historical traditions. These connotations are apparent in the Rory Gallagher sculpture and are further accentuated in this case by its bronze material, which construes a sense of ‘tradition, or more accurately, timelessness’ (145). Read in this way then, the sculpture can be seen as a reflection of Rory’s music, legacy and important place in Irish music history.

The sculpture was created by Geraldine Creedon, an artist and one of Rory’s old schoolfriends, and shows the flat outline of an abstract guitar with its multiple strings protuberating and bending in a snakelike fashion. The undulating strings create a sensory experience (Ledin and Machin Citation2020: 151), made more emphatic by the floating hand gripping the top of the strings and the thumb and index finger plucking the bottom strings. At the time of its construction, Rory’s mother was so upset about the thought of seeing her son cast in statue form that she requested an abstract design instead. Here, through the two hands, Rory is imagined rather than seen, encouraging viewers to conjure him up and remember him in whatever form they choose. This fits with Abousnnouga and Machin’s (Citation2013: 199) belief that ‘the essence or soul of people can be found in the landscape itself’. The sculpture’s bronze has turned a mottled green over time due to oxidation. These signs of wear and tear are reflective of its 26 years in the square and highlight the fact that semiotic artefacts are ‘living’ and in a constant state of flux (Wyndham Citation2011).

Each of the strings are engraved with a lyric from Rory’s 1982 album Jinx. Jinx is an album that holds a very special place in my heart. It was written at a difficult time in Rory’s life, where his struggles with depression and anxiety were getting worse, and I first listened to it at a similar point in my own life. Therefore, having the opportunity to run my fingers over the words that Rory crafted is unexpectedly emotional. With its irregularity and narrowly spaced, sloping letters (Ledin and Machin Citation2020: 135), the chosen font resembles handwriting, making this tactile process even more intimate and meaningful. As much as I love Jinx, before I came to Cork, I always thought that these lyrics were a strange choice for the sculpture, given the sombre tone of the album. The chosen songs (‘Jinxed’, ‘Easy Come Easy Go’, ‘Signals’, ‘The Devil Made Me Do It’) reflect a certain melancholy, particularly when viewed on paper:

Seargeant and Giaxoglou (Citation2019) point out that when multiple artefacts are juxtaposed within the same semiotic landscape, they develop a narrative potential and work in tandem with one another to create meaning. This is certainly the case with Rory Gallagher Place. The square is such a central meeting place in Cork that, even if passers-by are unaware who Rory is, they are continuously introduced to him through the street name and accompanying sculpture. Thus, both the square and sculpture become an important part of the commemorative musicscape, serving as both a literal and figurative signpost, creating a common historical frame of reference, working subtly to embed Rory in the public consciousness and claiming a symbolic ownership of place and imbuing it with new sociocultural meanings (Alderman Citation2012).

4:30pm St Patrick’s Hill and Bell’s Field

The next leg of my journey takes me deep into the Victorian Quarter – a vibrant area north of the River Lee which, as the name suggests, is made up of nineteenth-century buildings. Of particular relevance to my pilgrimage is the fact that this area was where Rory grew up. Rory was always keen to stress that he did not want to be put in a ‘golden cage’ and hoped that Corkonians respected him ‘as someone from their own town’ (Haring Citation1986). Thus, even once famous, he could often be found on visits back home walking the streets of this area and talking to fans.

Before I cross the river to the Victorian Quarter, however, I pass some other significant sights along the way. I leave Rory Gallagher Place and head into Emmett Place, a large pedestrianised square with an interesting blend of old and new. On one side of the square is a modern shopping complex with famous high street stores, juxtaposed with repurposed old buildings, such as a Queen Ann style townhouse, now housing a Starbucks café. But what I am interested in lies on the other side of the square and boasts another strange juxtaposition of two distinct architectural styles: the Crawford Art Gallery and Cork Opera House (). The Crawford Art Gallery is based in the city’s old customs house (built in 1724) and is made of red brick and ashlar limestone with a unique octagonal turret. The Cork Opera House, in contrast, was rebuilt in 1965 after a fire destroyed its original Victorian building, and updated with a new glass front in 1993 to ‘take the architecture of Cork City into the twenty-first century’ (Cork Opera House Citation2023). According to Ledin and Machin (Citation2020: 160), brick is often tied up with history and heritage, while glass conveys modernity, creativity and innovation (159) – meanings which fit the purposes and aims of the art gallery and opera house, respectively.

While both buildings have no distinctly visible connections to Rory in the same way as the previous stops on my tour, they are deeply connected with his musicscape. Bock and Stroud (Citation2019: 4) argue that sites do not always have to display easily discernible material traces to be noteworthy; they can instead be ‘internalised and embodied’ experiences of place that are brought out in narratives. This is precisely the case here. Away from music, Rory had a great interest in art and regularly attended evening classes at the Crawford Art Gallery (then the Crawford School of Art) throughout his later teenage years. Cork Opera House, on the other hand, is where he played an iconic concert in 1987 that was recorded for RTÉ for a special Christmas broadcast. Back in 2016, I spotted a DVD of the concert for £1 in a second-hand shop and thought that I would try it out. Little did I know at the time what a life-changing decision that would turn out to be. Thus, walking through the door of the building is of great personal significance to me as I reflect on the ‘Before Rory’ and ‘After Rory’ periods of my identity. The Opera House also has another layer of meaning when juxtaposed with the Art Gallery, enabling me to visualise two different points in Rory’s own life and share those experiences with him, albeit from a temporal distance.

I finally reach the River Lee and see St Patrick’s Hill looming up ahead. I say looming because it is extremely steep and difficult to climb, yet leads up to some of the best views of Cork city. I cross St Patrick’s Bridge – another seemingly banal sight that is, in fact, part of the Rory musicscape, featuring in his iconic Irish Tour ‘74 documentary – and feel obliged to recreate the famous scene of Rory walking across. In her study of the mythology of Abbey Road, Bennett (Citation2016: 404) notes that the road’s appearance on The Beatles’ famous album cover has turned the site into ‘hallowed ground’ and made it part of a ‘collective visual memory’ that unites fans. The same can be said of St Patrick’s Bridge and the adjoining St Patrick’s Hill (which Rory can be seen walking down in the 1972 Music Makers documentary). As I walk, I look for parts of the semiotic landscape that have not changed in the last fifty years. While I am upset at the number of parked cars (which hinder my ability to recreate certain scenes), I grin with delight when I see mundane aspects of the city that have remained the same and elevate them to a new ‘divine’ level. Thus, railings, letterboxes, gates and window frames all take on new meanings, moving from part of Cork’s semiotic landscape to part of its semiotic musicscape simply because of their loose connection to Rory ().

Figure 10. St Patrick’s Hill and Bell’s Field then and now. Source: Music Makers documentary (1972) and author’s own photo.

I climb all the way up to Bell’s Field and take in the view over Cork city. Despite the bad weather (it is now starting to rain), the field is full of people relaxing, walking dogs or playing football. I cannot help but marvel at the fact that they all seem oblivious to the significance of this site. For many years, I have watched footage of Rory standing in this very place giving an interview, so to finally be here myself feels like stepping on ‘hallowed ground’. In fact, I almost expect to bump into Rory at any moment, such is his spiritual presence here. With a lack of visual indicators that Rory was once here, I turn to tactile indicators instead, running my hand along the rough edges of the stone wall, kneeling down to feel the grass between my fingertips. I even take a few pebbles from the dusty pathway and stash them into my coat pocket as keepsakes. As I sit down on a bench, the bells of the Shandon Tower strike 5:00pm, their sound echoing across the field. I think back to 2015 when, to mark the 20th anniversary of Rory’s passing, the bells rang out with the sounds of his song ‘Tattoo’d Lady’. To add to this poignancy, they were pulled by his nephew Eoin while, at the same time, local radio stations across the city played the song over the airways. It is intangible cultural heritage like this that is difficult to remember and indeed protect. However, as Zhuang et al. (Citation2022) suggest, it can be remembered by viewing the landscape – or in this case, musicscape – as the cultural carrier, thereby allowing concrete things to be felt visually and the cultural atmosphere to be felt abstractly through the other senses. That is exactly what I seek to do through my presence here today.

5:50pm Sidney Park and MacCurtain St

I descend St Patrick’s Hill and turn off into Wellington Road, before starting my ascent once again along the winding pathway, this time to Sidney Park. I am in search of number 11 – the house where Rory lived with his mother Monica in the early 1970s and where he was filmed outside with his brother Dónal in the iconic Irish Tour ‘74 documentary. I have seen the house so many times on film that I recognise it immediately from afar. I walk its perimeter, noting that the gate has been repainted in blue and the front door and windows have been replaced, yet its fundamental structure and gardens remain unchanged. This somehow feels like the most intimate part of my journey so far, to be outside the house where Rory once lived. I am particularly self-conscious, knowing that another family now resides there and that my presence is an intrusion on their everyday lives. It reminds me of both the complexities and nuances of the semiotic musicscape. This is not Graceland – a museum open to the public – yet the feelings I am experiencing being here are undoubtedly the same ().

In her study of Elvis Presley, Doss (Citation2018: 133) notes that the desire to see and experience Graceland is akin to the desire to see and feel Elvis. People visit the house because they seek a ‘visceral experience […] intensified modes of sensation that may permit empathetic response, encourage ideological attachment and, especially, confirm our own reality’ (134). Through this subjective, personal and authentic ritualistic performance, fans are able to make meaning from Elvis’s death, emotionally indulge themselves and embrace their overwhelming feelings of ‘love, loss and loneliness’ (Doss Citation2018: 134). Standing before 11 Sidney Park, I am awash with such feelings. I am also aware of the duality between the semiotic musicscape and my emotions, both feeding off and influencing one another. I can shape the signs around me as much as they can shape me. As I lean on the garden wall, for example, the tears that I shed hit the stone and leave a wet patch. Likewise, unhappy with the dust covering the Sidney Park street sign, I wipe it clean with a tissue. If I had not come here this afternoon, these markers would be subtly different.

Retracing my steps, I rejoin St Patrick’s Hill once again, turning left into MacCurtain Street when I reach the bottom – a busy thoroughfare filled with bars, restaurants and shops. I stop outside number 27. Although now occupied by a launderette, this building once housed the Modern Bar, run by Rory’s maternal grandparents. Rory lived above the bar with his mother and brother when they first moved to Cork from Ballyshannon in 1956. Although all visible traces of the bar are now gone, just by looking at the building, my mind is able to recreate certain scenes that I have frequently read about: raucous family New Year’s Eve parties in the bar; young Rory spending hours in the bedroom upstairs learning how to play guitar on his flat top acoustic; the Gallagher brothers sneaking Rory’s newly purchased Stratocaster up the stairs and hiding it under the bed so their mother would not find out; Rory proudly showing his freshly pressed debut solo album to his family in the bar’s basement in 1971.Footnote12 These are signs of a time or place that only exists today in the ‘discursive imagination’ (Lee and Lou Citation2019: 11), yet they turn a seemingly mundane site into an integral part of Cork’s semiotic musicscape. In other words, they represent an imagined semiotic landscape and intangible heritage, only made significant through the past music memories that they hold. As a Rory fan, the fact that the site is now a launderette is also meaningful for me, ‘Laundromat’ being a well-known Rory song and, in fact, the first that I ever heard.

Just along the road at number 29, there is a more tangible form of heritage: a plaque erected by Cork City Council in 1996 in memory of Rory. It sits high up on the wall next to the Son of a Bun restaurant, once the site of Crowley’s Music Centre.Footnote13 Being an official memorialisation artefact, the plaque is part of a semiotic domain with its own unique genre and rules. Thus, it follows a relatively standardised ‘name-date-occupation’ format (Tivyaeva Citation2023):

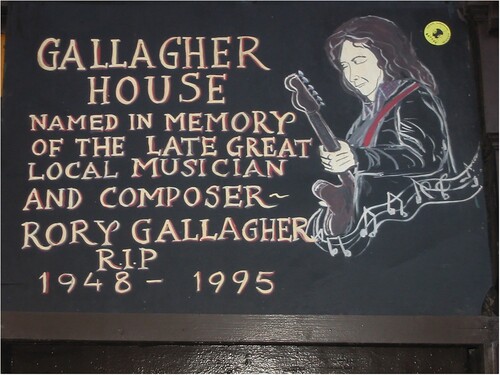

As I near the end of my tour and look forward to finally stopping for a bite to eat, I pause for reflection on an important piece of tangible heritage that is no longer here. For many years, 32 MacCurtain Street has informally been known as ‘Gallagher House’. Since 2013, Gallagher’s Gastropub has occupied the house, replacing the previous Gallagher’s Bar. However, in this transferral of ownership, a plaque was removed, its loss having a strong impact on Cork’s semiotic musicscape. The plaque was what Roberts and Cohen (Citation2014b) would define as ‘self-authorised’ rather than official (). It was rather crudely constructed with shaky handwritten gold letters and an accompanying sketch of Rory. While it carried over genre rules from the official plaque further down the road (e.g. name, dates, occupation), it also brought in more emotive, informal elements, describing Rory as ‘late great’ and adding ‘RIP’ after his name. This sign was clearly the work of a genuine fan, not an official body. But what is even more significant to me is the sketch of Rory. When memorialising Rory – whether in the public space, in music magazines or in documentaries – there is a strong tendency to show him in the 1970s as a young man in a check shirt. Images from the latter fifteen years of his career when he was older, heavier and suffered from increasingly poor health are typically disregarded, reflecting a common pattern when it comes to depictions of celebrities (Jermyn Citation2016).Footnote14 This plaque, however, stood alone in representing older Rory, depicting him as he looked in the late 1980s/early 1990s.

Figure 13. Gallagher House Plaque. Source: Reading the Signs, https://readingthesigns.weebly.com/blog/rory-gallagher.

Its removal is felt for multiple reasons. First, as Roberts and Cohen (Citation2014b) note, such self-authorised plaques are both an ‘asset’ in the absence of officially sanctioned listed status and a ‘strategic tool’ for preserving a building’s social, cultural and economic value and enabling its continued use. Furthermore, their presence ‘furnish[es] a means by which to give substance to the ritual and performative dimensions of cultural memory’ (12). Turning specifically to the Rory example, its removal entails the loss of a memory tied up with an already neglected part of his career. This is made even more poignant by the fact that just down the road at the Everyman Palace Theatre, Rory played a barnstorming three-hour gig in August 1992, donating all proceeds to the Irish Red Cross in aid of the Yugoslavian Refugee Crisis. With few people today aware of this concert, the image of him on this plaque served as a last visual reminder of the occasion. Through its removal, a piece of history is also removed, indicating how a city’s semiotic musicscape is impacted just as much by what remains as what does not and that it is ultimately humans who control these memories and memorialisations.Footnote15

On this sober note of reflection, I head into Gallagher’s Gastropub, order a drink and make a toast to Rory. Sláinte.

Conclusion

This paper has outlined my autoethnographic walking tour of Rory Gallagher’s Cork city through the lens of semiotic landscapes, or what I call semiotic musicscapes. Semiotic musicscapes foster an understanding of the visual linguistic environment as a form of ‘embodied music tourism’ or ‘psychogeographic practice’ (Johinke Citation2018), connecting fans to their musical icons through both tangible and intangible signs of cultural heritage. In doing so, they bring new perspectives into the sights and sounds of a city, imbuing mundane spaces with unique meanings that go beyond their physicality and developing them into sites of memorialisation, commemoration and collective memories, all tied up with one particular musician.

To unpack these ideas further in relation to my own personal experience and drawing on the framework outlined earlier in , semiotic musicscapes enable walking around a city to be seen as an act of secular pilgrimage as fans visit ‘sacred’ places and step on ‘hallowed ground’. Like true pilgrims, they must battle physical challenges along the way, be they poor weather, hunger and tiredness, as well as emotional exertion from simply being in a place that means so much on an individual level. Equally, votive offerings are left in places of significance as signs of love and remembrance, while mementos are acquired throughout the journey to take home as souvenirs. It is this emotional connection with space that is a key feature of semiotic musicscapes, turning a simple walk from a physical activity or sightseeing venture into a deep exploratory bond with a musician and a way of making meaning from their life (and death).

While there are obvious and tangible features of semiotic musicscapes, such as plaques, sculptures and street signs (i.e. emplacement), there are also just as many – if not more – intangible features lying dormant on every corner and waiting to be reactivated by visitors like me. ‘Ordinary’ spaces like a launderette on MacCurtain Street or a field overlooking Cork city, for example, become ‘extraordinary’ if only you have the knowledge to unlock their meanings and enter into an imagined relationship with the space. Thus, not every fan’s journey will be the same; while some will be bound solely by the obvious linguistic and visual semiotic markers they see (e.g. Rory Gallagher Place, Rory Gallagher Music Library), others will be more fluid, extending the semiotic musicscape through what they know about Rory and his relationship with a particular space in the city. By this same token, semiotic musicscapes also encourage a reflection on what has been lost through time. While the memory of a particular moment in Rory’s career cannot be adequately captured in an artefact, there are cases – such as with the Gallagher House plaque – where removal erases a part of Cork’s musical heritage (i.e. the latter part of Rory’s career).

While semiotic landscapes take into account sounds in the surrounding space, semiotic musicscapes extend this through the act of listening to music itself, thereby enhancing the perceptual space. Sitting at Rory’s graveside listening to ‘A Million Miles Away’ was akin to a religious experience, which strengthened my connection with both him and the space at that moment. Semiotic musicscapes also afford creative opportunities to harness the environment and recreate iconic moments filmed or photographed there (in my case, the 1972 Music Makers documentary and Irish Tour ‘74 documentary), again bringing another level of meaning to the visual and verbal signs.

Another important aspect of semiotic musicscapes is the heteroglossic and intertextual relationships that they create with other fans. Through stepping into similar spaces or leaving votive offerings, fans speak in an asynchronous dialogue with one another. This brings a diversity of voices and perspectives to the same space, cueing knowledge and keeping its exchange dynamic. Encounters with fans can also happen in real time. When I was taking photographs on St Patrick’s Hill, for example, I was ‘recognised’ by another fan and engaged in a brief conversation about Rory with them, which enhanced my ‘pilgrimage’ experience. Encounters such as these emphasise how semiotic musicscapes are not static and that fans constantly shape them. From a physical perspective, through my footprints and my actions (e.g. cleaning the Sidney Place street sign), I leave a piece of myself behind, my own physical signs that I was there, I remembered Rory today, even if nobody else did. Semiotic musicscapes, thus, encourage embodiment as visitors enter a space, negotiating, performing and internalising the personal memories and cultural identities that they encounter along the way.

Integral to all the above is the strong connection between space, place and identity. Identity is multi-faceted by nature, but being part of a semiotic musicscape allows certain aspects to be foregrounded or backgrounded. Naturally, my identity as a fan was my core motivator to visit Cork and was essential to how I navigated and interpreted the places I encountered, finding meaning in perceptual, imagined and emotional spaces in the semiotic musicscape that others may not be aware of. My status as a fan was something of which I was overtly conscious throughout my journey, whether in terms of my clothing, posture, movements or gaze. My Irishness was also intrinsic to my identity as I walked the streets of Cork. I felt a tremendous sense of pride that Rory and I shared a nationality, and I felt a rare self-confidence in my physical Celtic traits (e.g. ginger hair, pale skin, freckles) that I often bemoan when in England. Even my Catholicism took on a new meaning here as I visited churches associated with Rory and engaged in rituals that I have not undertaken for years. I also had not envisaged that my gender and age would create such an impact. As documented by my encounter with the bus driver (but also on other occasions as I walked around the city), Corkonians commented on how wonderful it was to see a young woman who was such a huge Rory fan. Many expressed the importance of ‘passing the torch’ so that future generations remained aware of Rory’s musical legacy. Throughout my journey, I was also highly conscious of my identity as an anxiety sufferer in the process of recovery from a mental health breakdown and how I would not have even made it to Cork without the soothing powers of Rory’s music. Not once did I think of myself as an academic, nor did I have any intention of writing a paper, but as I returned home, the idea emerged holistically. The trip to Cork undoubtedly shaped me as a person, intensifying my bond with Rory and his music, as well as my sense of Irishness. It helped me accept who I am and continue on my path to healing, as well as my desire to keep his music alive among young people. Almost two years later, the trip is still fresh in my mind and I think about it a lot. I plan to return as soon as I can.

Using my autoethnographic exploration of Rory Gallagher’s Cork, I have shown how semiotic musicscapes offer a creative extension to the concept of semiotic landscapes, tailoring the framework to the setting of secular pilgrimages and music memories. Semiotic musicscapes also provide a new way for ethnomusicologists to explore the relationship between music, place, space and identities. My study has sought to shine a light on a musician who is often overlooked in academic work, despite his importance to the history of Irish music. However, the same approach could be applied to other geographical contexts and musicians. Indeed, I recently undertook a similar trip to London, uncovering places and spaces associated with Rory, as well as Dublin to explore sites linked to Phil Lynott. Another possible avenue of exploration is how I shared my Cork pilgrimage publicly via my Rory Gallagher Instagram fanpage. Offering real-time updates of my journey, along with photos, videos and text, turned it into a collaborative experience, expanding the semiotic musicscape into the virtual domain. Since my trip, other friends visiting Cork have asked for a copy of my route and, in turn, have also shared their journeys live on Instagram. As Rory continues to attract new generations of fans, working with Cork Tourist Information Centre to produce self-guided walking tours of Rory’s semiotic musicscape would be beneficial, promoting the rich musical heritage of the city. After all, even 28 years since his death, it is clear that the whole of Cork city still beats firmly with Rory’s heart.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lauren Alex O’Hagan

Lauren Alex O’Hagan is Research Fellow in the School of Languages and Applied Linguistics at the Open University and Affiliate Researcher in the Department of Media and Communication Studies at Örebro University. She specialises in the study of music memorabilia, media representations of Irish musicians and online fandoms, and has previously published works on Rory Gallagher, Phil Lynott and Tom Petty. She is the co-founder of the Rewriting Rory blog (www.rewritingrory.co.uk) aimed at shining a positive light on the last decade of Rory Gallagher’s career.

Notes

1 I refer to Rory Gallagher as ‘Rory’ throughout this paper due to my close relationship with his music and the autoethnographic nature of this study.

2 Although Rory was born in Ballyshannon (County Donegal) on 2 March 1948, he moved to Cork when he was 8 years old and always considered it to be his hometown.

3 Cohen continues to carry out pioneering ethnographic research on Liverpool’s music scene, although her works are too many to cite in full here.

4 In the context of Sociolinguistics, discourses can be roughly defined as the social purposes of texts and how they construct knowledge (Fairclough Citation1992).

5 According to the preliminary results of the 2022 Irish census. See: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-cpr/censusofpopulation2022-preliminaryresults/geographicchanges/ (accessed 13 February 2024).

6 According to 2008 regulations made to the Official Languages Act of 2003.

7 On interviewing Rory in 1976, photographer Janet Macoska presented him with a white carnation, knowing that he was extremely shy and that holding the carnation would ‘distract’ him as he talked.

8 As told to me anecdotally by various Corkonians.

9 The poem was written when Wall was waiting to receive his COVID-19 vaccination at Cork City Hall. He started to look around him at the other people his age and wondered how many of them had also been there back in 1971 to see Rory’s concert.

10 As explained by Rory’s nephew Daniel Gallagher in a 2019 video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gUfN4r9gr0M&t=2s

11 Over the last decade of Rory’s life, he suffered increasingly poor mental and physical health. This led to an overreliance on prescription medication, which ultimately led to him requiring a liver transplant. Rory survived the transplant and was recovering well, but caught MRSA shortly before being released from hospital. He passed away on 14 June 1995 at just 47 years old.

12 My thanks to Rory’s cousin Jim Roche for the last memory.

13 Crowley’s Music Centre is where Rory bought his iconic Stratocaster in 1963, although the shop was located on Merchant’s Quay at the time.

14 One noteworthy example of this is the remastered version of Rory’s 1990 album Fresh Evidence, where the front cover image was replaced with a photograph of him from the early 1970s.

15 It is worth noting that there are also numerous other Rory-inspired murals, or ‘music heritage graffiti’, throughout Cork city that no longer exist, such as the iconic image of Rory by local artist Vincent Zara on the side of Ziggy’s Rock Bar (now The Park Bar) on Tuckey Street. Like the plaque on Gallagher House, their removal has significantly altered the city’s semiotic musicscape, specifically in reference to public memorialisation of Rory.

References

- Abousnnouga, Gill and David Machin. 2013. The Language of War Monuments. London: A&C Black.

- Alderman, Derek H. 2012. ‘Street Names as Commemorative Landscapes: The Case of Martin Luther King, Jr’. Commemorative Landscapes of Northern Carolina. https://docsouth.unc.edu/commland/features/essays/alderman_one/ (accessed 13 February 2024).

- Anderson, Jon. 2004. ‘Talking Whilst Walking: A Geographical Archaeology of Knowledge’. Royal Geographical Society 36(3): 254–61.

- Backhaus, Peter. 2007. Linguistic Landscapes: A Comparative Study of Urban Multilingualism in Tokyo. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Bakhtin, Michael. 1981. ‘Discourse in the Novel’. In The Dialogic Imagination, edited by Michael Jolquist and Caryl Emerson, 259–422. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Banda, Felix and Hambaba Jimaima. 2015. ‘The Semiotic Ecology of Linguistic Landscapes in Rural Zambia’. Journal of Sociolinguistics 19(5): 640–70.

- Barthes, Roland. 1977. Image Music Text. London: Fontana Press.

- Bates, Charlotte and Alex Rhys-Taylor. 2017. Walking Through Social Research. London: Routledge.

- Bellentani, Federico and Mario Panico. 2016. ‘The Meanings of Monuments and Memorials: Toward a Semiotic Approach’. Punctum. International Journal of Semiotics 2(1): 28–46. doi:10.18680/hss.2016.0004.

- Bennett, Andy. 1999. ‘Rappin’ on the Tyne: White Hip Hop Culture in Northeast England – An Ethnographic Study’. The Sociological Review 47(1): 1–24. doi:10.1111/1467-954X.00160.

- Bennett, Samantha. 2016. ‘Behind the Magical Mystery Door: History, Mythology and the Aura of Abbey Road Studios’. Popular Music 35(3): 396–417. doi:10.1017/S0261143016000556.

- Blackwood, Robert and John Macalister. 2019. Multilingual Memories: Monuments, Museums and the Linguistic Landscape. London: Bloomsbury.

- Bock, Zannie and Christopher Stroud. 2019. ‘Zombie Landscapes: Apartheid Traces in the Discourses of Young South Africans’. In Making Sense of People and Place in Linguistic Landscapes, edited by Amiena Peck, Christopher Stroud and Quentin Williams, 11–27. London: Bloomsbury.

- Bolderman, Leonieke and Stijn Reijnders. 2016. ‘Have You Found What You’re Looking For? Analysing Tourist Experiences of Wagner’s Bayreuth, ABBA’s Stockholm and U2’s Dublin’. Tourist Studies 17(2): 146–81.

- Butz, David and Kathryn Besio. 2009. ‘Autoethnography’. Geography Compass 3(5): 1660–74. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2009.00279.x.

- Chaney, Damien and Christina Goulding. 2016. ‘Dress, Transformation, and Conformity in the Heavy Rock Subculture’. Journal of Business Research 69(1): 155–65. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.07.029.

- Clayton-Lea, Tim. 1983. ‘The Philip Lynott Interview (1983)’. Hot Press Magazine, 28 February 2011. https://www.hotpress.com/music/the-philip-lynott-interview-431546 (accessed 13 February 2024).

- Cohen, Sara. 1991. Rock Culture in Liverpool: Popular Music in the Making. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Connell, John and Chris Gibson. 2003. Sound Tracks: Popular Music, Identity and Place. London: Routledge.

- Cork Opera House. 2023. ‘About Us’. https://www.corkoperahouse.ie/about-us/.

- de la Barre, Jorge. 2010. ‘Music, City, Ethnicity: Exploring Music Scenes in Lisbon’. Revista Migrações 7: 139–55.

- Doss, Erika. 2018. ‘Rock and Roll Pilgrims: Reflections on Ritual, Religiosity, and Race at Graceland’. In Shrines and Pilgrimage in the Modern World, edited by Peter Jan Margry, 123–43. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Ellis, Carolyn, Tony E. Adams and Arthur P. Bochner. 2010. ‘Autoethnography: An Overview’. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research 12(1). https://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1589/3095.

- Embassy of Ireland. 2014. ‘Rory Gallagher (1948–1995), A Founding Figure of Irish Rock Music’. https://www.dfa.ie/irish-embassy/great-britain/about-us/ambassador/ambassadors-blog-2014/october2014/rory-gallagher-founding-figure-of-irish-rock-music/ (accessed 13 February 2024).

- Fairclough, Norman. 1992. Discourse and Social Change. London: Polity Press.

- Finnegan, Ruth. 1989. The Hidden Musicians: Music-Making in An English Town. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Goffman, Erving. 1981. Forms of Talk. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Haring, Hermann. 1986. ‘Rory Gallagher: Our Fellow Worker from Cork’ [March 1986], http://www.roryon.com/fellow184.html (accessed 13 February 2024).

- Harris, Racheal. 2020. Photography and Death: Framing Death Throughout History. Emerald: Bingley.

- Heddon, Deirdre and Cathy Turner. 2010. ‘Walking Women: Interviews with Artists on the Move’. Performance Research 15(4): 14–22. doi:10.1080/13528165.2010.539873.

- Hogan, Eileen. 2016. ‘‘Corkonian Exceptionalism: Identity, Authenticity and the Emotional Politics of Place in a Small City’s Popular Music Scene’’. Ethnomusicology Ireland 4: 1–26.

- Hogan, Eileen. 2021. ‘Parochial Capital and the Cork Music Scene’. In Made in Ireland: Studies in Popular Music, edited by Áine Mangaoang, John O’Flynn and Lonán Ó Briain, 185–94. New York: Routledge.

- Holmberg, Per. 2021. ‘Reading Runes with the Sun. A Geosemiotic Analysis of the Rök Runestone’. Multimodality & Society 1(4): 455–73. doi:10.1177/26349795211059109.

- Hult, Francis M. 2014. ‘Drive-Thru Linguistic Landscaping: Constructing a Linguistically Dominant Place in a Bilingual Space’. International Journal of Bilingualism 18(5): 507–23. doi:10.1177/1367006913484206.

- Jaworski, Adam and Crispin Thurlow. 2010. Semiotic Landscapes: Language, Image, Space. London: Continuum.

- Jermyn, Deborah. 2016. Female Celebrity and Ageing: Back in the Spotlight. New York: Routledge.

- Johinke, Rebecca. 2018. ‘‘Take a Walk on the Wild Side’: Punk Music Walking Tours in New York City’. Tourist Studies 18(3): 315–31. doi:10.1177/1468797618771694.

- Kallen, Jeffrey L. 2010. ‘Changing Landscapes: Language, Space and Policy in the Dublin Linguistic Landscape’. In Semiotic Landscapes: Language, Image, Space, edited by Adam Jaworski and Crispin Thurlow, 41–59. London: Continuum.

- Kelly, Paul, Marie Murphy and Nanette Mutrie. 2017. Walking. Emerald: Bingley.

- Kong, Lily. 1995. ‘Popular Music in Geographical Analyses’. Progress in Human Geography 19(2): 183–98.

- Kress, Gunther and Theo van Leeuwen. 2002. ‘Colour as a Semiotic Mode: Notes for a Grammar of Colour’. Visual Communication 1(3): 343–68.

- Kress, Gunther and Theo van Leeuwen 2006. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Routledge.

- Kruse, Robert J. 2003. ‘Imagining Strawberry Fields as a Place of Pilgrimage’. Royal Geographical Society 35(2): 154–62.

- Kusenbach, Margarethe. 2003. ‘Street Phenomenology: The Go-Along as Ethnographic Research Tool’. Ethnography 4(3): 455–85.

- Landry, Rodrigue and Richard Y. Bourhis. 1997. ‘Linguistic Landscape and Ethnolinguistic Vitality’. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 16(1): 23–49.

- Lashua, Brett, Karl Spracklen and Phil Long. 2014. ‘Introduction to the Special Issue: Music and Tourism’. Tourism Studies 14(1): 3–9.

- Ledin, Per and David Machin. 2020. Introduction to Multimodal Analysis. London: Sage.

- Lee, Jerry Won and Jackie Jia Lou. 2019. ‘The Ordinary Semiotic Landscape of an Unordinary Place: Spatiotemporal Disjunctures in Incheon’s Chinatown’. International Journal of Multilingualism 16(2): 187–203.

- Leeman, Jennifer and Gabriela Modan. 2009. ‘Commodified Language in Chinatown: A Contextualized Approach to Linguistic Landscape’. Journal of Sociolinguistics 13(3): 332–62.

- Leyshon, Andrew, David Matless and George Revill. 1998. The Place of Music. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Long, Paul. 2014. ‘Popular Music, Psychogeography, Place Identity and Tourism: The Case of Sheffield’. Tourist Studies 14(1): 48–65.

- Lou, Jackie Jia. 2017. ‘Spaces of Consumption and Senses of Place: A Geosemiotic Analysis of Three Markets in Hong Kong’. Social Semiotics 27(4): 513–31.

- Malinowski, David. 2009. ‘Authorship in the Linguistic Landscape: A Multimodal-Performative View’. In Linguistic Landscape: Expanding the Scenery, edited by Elana Shohamy and Durk Gorter, 107–25. New York: Routledge.

- McCarthy, Kieran. 2016. Cork City History Tour. Stroud: Amberley Publishing.

- McIlvenny, Paul. 2015. ‘The Joy of Biking Together: Sharing Everyday Experiences of Vélomobility’. Mobilities 10(1): 55–82.

- Moriarty, Mairead. 2015. ‘Indexing Authenticity: The Linguistic Landscape of an Irish Tourist Town’. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 232: 195–214.

- O’Flynn, John and Áine Mangaoang. 2019. ‘Sounding Dublin: Mapping Popular Music Experience in the City’. Journal of World Popular Music 6(1): 32–61.

- O’Hagan, Lauren A. 2021a. The Sociocultural Forms and Functions of Edwardian Book Inscriptions: Taking a Multimodal Ethnohistorical Approach. New York: Routledge.

- O’Hagan, Lauren A. 2021b. ‘Instagram as an Exhibition Space: Reflections on Digital Remediation in the Time of COVID-19’. Museum Management and Curatorship 36(6): 610–36.

- O’Hagan, Lauren A. 2022a. ‘“It’s Always Nice to Head for Home”: Music-Making, Sense of Place, and Corkonian Identity in the Rory Gallagher Irish Tour ‘74 Documentary’. Journal for the Society of Musicology in Ireland 17: 47–77.

- O’Hagan, Lauren A. 2022b. ‘“My Musical Armor”: Exploring Metalhead Identity Through the Battle Jacket’. Rock Music Studies 9(1): 34–53.

- Osborne, Alana. 2019. ‘On a Walking Tour to No Man’s Land: Brokering and Shifting Narratives of Violence in Trench Town, Jamaica’. Space and Culture 23(1): 48–60.

- Papen, Uta. 2012. ‘Commercial Discourses, Gentrification and Citizens’ Protest: The Linguistic Landscape of Prenzlauer Berg, Berlin’. Journal of Sociolinguistics 16(1): 56–80.

- Peck, Amiena and Felix Banda. 2014. ‘Observatory’s Linguistic Landscape: Semiotic Appropriation and the Reinvention of Space’. Social Semiotics 24(3): 302–23.

- Pennycook, Alistair and Emi Otsuji. 2015. Metrolingualism. Language in the City. London: Routledge.

- Pink, Sarah. 2015. Doing Sensory Ethnography. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Prada, Josh. 2023. ‘Sensescapes and What It Means for Language Education’. In Linguistic Landscapes in Language and Teaching Education, edited by Sílvia Melo-Pfeifer, 243–58. Berlin: Springer.

- Prior, Nick. 2015. ‘“It’s A Social Thing, Not a Nature Thing”: Popular Music Practices in Reykjavik, Iceland’. Cultural Sociology 9(1): 81–98.

- Roberts, Les and Sara Cohen. 2014a. ‘Unauthorising Popular Music Heritage: Outline of a Critical Framework’. International Journal of Heritage Studies 20(3): 241–61.

- Roberts, Les and Sara Cohen 2014b. ‘Unveiling Memory: Blue Plaques as In/Tangible Markers of Popular Music Heritage’. In Sites of Popular Music Heritage: Memories, Histories, Places, edited by Sara Cohen, Robert Knifton, Marion Leonard and Les Roberts, 221–39. London: Routledge.

- Sassoon, Rosemary. 1999. Handwriting of the Twentieth Century. London: Psychology Press.

- Scarvaglieri, Claudio, Angelika Redder, Ruth Pappenhagen and Bernhard Brehmer. 2013. ‘Capturing Diversity: Linguistic Land- and Soundscaping in Urban Areas’. In Linguistic Superdiversity in Urban Areas: Research Approaches, edited by Joana Duarte and Ingrid Gogolon, 45–73. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Schwan, Stephan and Silke Dutz. 2020. ‘How do Visitors Perceive the Role of Authentic Objects in Museums?’. Research+Practice Forum 63(2): 217–37.

- Scollon, Ron and Suzie Scollon. 2003. Discourses in Place: Language in the Material World. London: Routledge.

- Seargeant, Philip and Korina Giaxoglou. 2019. ‘Discourse and the Linguistic Landscape’. In The Handbook of Discourse Studies, edited by Anna De Fina and Alexandra Georgakopoulou, 306–26. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Shank, Barry. 1994. Dissonant Identities: The Rock’n’Roll Scene in Austin, Texas. Hanover: Wesleyan University Press.

- Stahl, Geoff. 2004. ‘It’s Like Canada Reduced: Setting the Scene in Montreal’. In After Subculture: Critical Studies in Contemporary Youth Culture, edited by Andy Bennett and Keith Kahn-Harris, 51–64. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Stroud, Christopher and Dmitri Jegels. 2015. ‘Semiotic Landscapes and Mobile Narrations of Place: Performing the Local’. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 228: 179–99.

- Swiss, Thomas, John M. Sloop and Andrew Herman. 1998. Mapping the Beat: Popular Music and Contemporary Theory. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Tivyaeva, Irina V. 2023. ‘Memorial Plaques in Multimodal Urban Discourse: A Visual Narrative Reflecting Moscow’s Glorious Past’. Visual Anthropology 36(1): 38–53.

- van Leeuwen, Theo. 2006. ‘Towards a Semiotics of Typography’. Information Design Journal 14(2): 139–55.

- Wylie, John. 2005. ‘A Single Day’s Walking: Narrating Self and Landscape on the South West Coast Path’. Royal Geographical Society 30(2): 234–47.

- Wyndham, Felice S. 2011. ‘The Semiotics of Powerful Places: Rock Art and Landscape Relations in the Sierra Tarahumara, Mexico’. Journal of Anthropological Research 67(3): 387–420.

- Zhuang, Qianda, Mengying Wan and Guoquan Zheng. 2022. ‘Presentation and Elaboration of the Folk Intangible Cultural Heritage from the Perspective of the Landscape’. Buildings 12(9): 1388.