ABSTRACT

In 1934 the renowned Iraqi-Jewish musician Ezra Aharon/Azuri Effendi moved to Palestine, then under the British Mandate, where he became a prominent cultural figure who networked and intersected with a variety of agents—British authorities, Zionists, Palestinians, and a German musicologist specialising in ‘Oriental’ music. The correspondences, concert programmes, notes and musical works found in Ezra Aharon’s recently catalogued personal archive, alongside press articles, reveal the sociocultural tensions embedded in the on-the-ground encounter between ‘East’ and ‘West’ occurring in Mandate Palestine. The life story, musical activities and cultural spaces occupied by Azuri Effendi, provide a means of charting how ‘the Orient’ has been musically constructed by different agents, the shifting roles of Arab Jews in this trajectory, and the agency that musical practice brings to this terrain.

When I went to work with the Arabs they told me you are a Jew, you have to go to the Jews; I went to the Jews and they told me, you are an Arab, go to the Arabs. And I did not know what to do. (Azuri Effendi/Ezra Aharon in an interview with ethnomusicologist Amnon Shiloah, Jerusalem, 1981)

The quote that opens this article highlights the social dilemmas Aharon faced following his arrival in Palestine, as sociopolitical tensions engulfing the local communities of British Mandate Palestine (1917–1948) were mounting, and hostilities between the emergent Palestinian national movement and the Zionist movement were escalating. Since that time, the intractable conflict between the two national movements has led to an entrenched, bifurcated view of Arab/Palestinian-Jewish/Israeli in popular imaginations and oftentimes, in historiography. Yet the tensions embedded in the hyphen between Arab and Jew have been differently conceptualised and inflected by a variety of actors across time, changing sociopolitical circumstances and attendant sociocultural framings. During the British Mandate we see native Sephardim (descendants of exiles from late fifteen-century Spain who settled in Ottoman Palestine and were embedded in local Arabic culture) and recently arrived Jews from Arab countries such as Aharon, trying to mediate between polarities that they had never before known or experienced as ontological.

As this paper will show, perceptions of the hyphen between Arab and Jew are highly implicated in constructions of East and West, Oriental and Occidental, with Mandate Palestine becoming a site in which different actors drafted ideas about ‘the Orient’ to a variety of oftentimes conflicting, at times overlapping, sociopolitical agendas. Based on archival materials that include correspondences, programme notes, press articles, diaries, radio programmes, musical scores, and interviews,Footnote1 we show how music-making has been an arena in which this trajectory was played out, sounded, shaped, received and disseminated by different agents. The musical activities and cultural spaces occupied by Azuri Effendi, provide a means of charting how ‘the Orient’ has been musically constructed by different agents, the shifting roles of Arab Jews in this trajectory, and the agency that musical practice brings to this terrain.

We assign the term ‘Arab Jew’ to Azuri Effendi with full awareness of the symbolic charge it carries. Popular interest in a lost Arab Jewish past has flourished in a flurry of documentaries, memoires and other media over the past couple of decades (Levy Citation2008). Yet the term ‘Arab Jew’ has largely been confined to debates occurring within academic circles (see Hever and Shenhav Citation2010; Shenhav Citation2006), oftentimes among activist scholars who have sought to reclaim identities that have been deracinated and marginalised within the Zionist project—by disrupting the ideology of separation between Arab and Jew (Levy Citation2008). We follow the definition of Evri et al. who argue that ‘Arab-Jewish identity is a modern, fluid identity, transnational and at the same time national, one whose meanings change across variegated experiences of modernity’ (Citation2021: 353). We apply it to Ezra Aharon based on the expressive ways through which he himself acted out this hyphenated identity, as someone who composed poetry by both modern and medieval Hebrew poets, yet his intimate relationship to Arab language, literature, and even to the pre-Islamic world—for example, he composed an operetta based on characters of the Jahiliyyah period—permeated his oeuvre as well as the performative ways by which he managed his social relations throughout his life. Moreover, thinking of Azuri as an Arab Jew confronting multiplex experiences of locality and transnationality, and of variegated modernities, supports our interrogation of how constructions of ‘the Orient’ have taken shape through local encounters (and collisions) between different agents in British Mandate Palestine.

Aharon’s reception among diverse circles of British officials and Jewish and Palestinian music aficionados, critics, and scholars, is examined in the context of his activities as a prominent composer, performer, and bandleader. We show how Orientalism intersected with Ezra Aharon’s musical projects during the British Mandate via his relationships with the Zionist cultural establishment, British authorities, and fellow Jewish, Muslim, and Christian musicians active in Palestine, all of whom engaged with conceptualisations of ‘the East’ in different ways. Tracing the story and music of Ezra Aharon tells us about the shifting religious and national tensions Arab Jewish identities evoked during the Mandate era, in a context in which living encounters between ‘East’ and ‘West’ were being (musically) worked out on the ground.

Inflections of Orientalism at play in Mandate Palestine

For Edward Said (Citation1978), Orientalism is about the West’s gaze on Eastern Others. This gaze is unidirectional and embedded in power formations that generate a rigid Orient-Occident binary. Many scholars have since critiqued Said’s formulations, posing challenges to Said’s monolithic focus and laying claims to more nuanced accounts of how power relations between ‘Europe’ and its ‘Others’ are constructed. Chatterjee and Hawes (Citation2008: 1–13) argue that pejorative perceptions of the West were prevalent in Oriental societies since early modernity, and that negatively constructed epistemologies of ‘the Occident’ and ‘the Orient’ were part and parcel of the relations between Europe and its Others; this persisted to a certain extent even during the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Put differently, if the ‘Orient’ is an historical formation, the ‘Occident’ is too.

Said himself offers more nuanced perspectives on the production of Orientalist ontology in the afterword to the 2003 edition of his 1978 book, where he points out that ‘cultures and civilisations are so interrelated and interdependent as to beggar any unitary or simply delineated description of their individuality’ (Citation2003: 347). Moreover, in one of his latest public appearances he suggested that intellectuals must free themselves from rigid binaries if they try to ‘complicate and/or dismantle the reductive formulae and the abstract but potent kind of thought that leads the mind away from concrete human history and experience and into the realms of ideological fiction, metaphysical confrontation, and collective passion’ (Citation2004: 874).

We take up Said’s invitation to complicate the reductiveness embedded in the East–West binary by focusing on ‘concrete human history and experience’. We do so by looking at the multidirectional modes by which cultural identities were musically conceptualised and performed in Mandate Palestine—where ‘East’ and ‘West’ both overlapped and collided in multiple ways. This understanding of Orientalism offers nuanced insights on how power relations were activated by modern encounters between East and West. In taking this path, we also address another critique of Said, which highlights his disregard for ‘Orientalism in Reverse’ (Al-Azm [Citation1980] Citation2000), i.e. the ways in which Western Orientalist ontology and epistemology has also been internalised among elites in the societies of the Orient. Finally, we foreground the agency that ‘Orientals’ have brought to the socio-musical shaping of ‘the Orient’ as they negotiate both Western attitudes and locally naturalised Orientalism. While avoiding the pitfalls of (musical) ‘Orientalism in reverse’ (to paraphrase Al-Azm [Citation1980] Citation2000), we nevertheless consider Al-Azm’s (and later, Said’s) proposition that the Orientalist imaging has left a profound imprint on ‘the Orient’s modern and contemporary consciousness of itself’ (Al-Azm [Citation1980] Citation2000).

In the following, we provide short discussions of how Orientalism was diversely inflected among British colonialists, European Jews, and Palestinian Arabs. We then move to how these visions of the Orient were framed and constructed in the musical scene(s) of British Mandate Palestine by analysing the musical projects Azuri Effendi/Ezra Aharon led and created and the social networks he engaged with.

British Orientalism

Historian Lorenzo Kamel (Citation2015) has outlined the process of simplification of Palestine and its inhabitants—by which he means the tendency to rationalise the other in terms that are useful to the self—through the shifting inflections of the British Orientalist gaze. This was a long process that, once the British were given the Mandate to govern Palestine, differently affected its Jewish and Arab inhabitants. Until the mid-nineteenth century ‘Biblical Orientalism’ generated an idea of Palestine that was devoid of history except that of biblical times. In the second half of the nineteenth century this approach and mindset merged with imperial politics and expanding British penetration of the region.Footnote2 British public figures, often antisemitic, increasingly came to view Jewish ‘resettlement’ in Palestine as a means of guaranteeing British routes to the East, protecting imperial interests, and by the turn of the century—of redirecting the flow of Jewish refugees escaping pogroms in Eastern Europe away from England. The attitude of leading figures such as Arthur Balfour, Lloyd George, and Winston Churchill towards the Jews and Zionism was likewise based in a mixture of antisemitism and evangelical philosemitism.Footnote3

British approach to the Arab population in Palestine—90% of the population in late Ottoman times—wavered between disinterest and aversion, with the local inhabitants often described as foreigners or newcomers to their own land. During the Mandate, this latent Orientalist mindset was translated into active policy that discounted the meaning systems local Muslim Arab communities attributed to their social, cultural, and religious life. The top-down construction of institutions, religious titles and leadership simplified local political structures and marginalised Palestinian Arabs. For example, the Ottoman-era Mufti of Jerusalem became the Grand Mufti of Palestine, a politically motivated appointment that wielded tremendous power in the hands of a single individual (Hajj Amin al-Hussayni) and marginalised all other religious Muslim leaders, was in many ways at odds with Muslim practices and principles. It also changed the delicate balance between Muslims and Christians achieved in Ottoman times.

As described by numerous scholars, British development projects in Palestine were geared to develop an extractive economy that served imperial interests, but were often also aligned with Zionist objectives. For example, John Broich (Citation2013), discusses the ways in which British land and water policies were predicated on perceptions of Jews as innately modern, of Arabs as backward, and of the landscape as neglected and in need of improvement. British water policies and development projects merged with Zionist land reclamation plans and interests, often leading to a transformation of the pastoral and cultivable landscape in Palestine that disrupted Arab land-use strategies, displaced peasants, and supported Zionist settlement. For example, the drying up of the Hula valley swamplands in the 1930s displaced approximately 12,000 native inhabitants, whether due to direct uprooting or to the elimination of their sources of livelihood.Footnote4

Jewish Orientalism

‘A worthy primitive’ was the appellation used by music critic Menashe Rabinovitch (who had later changed his Eastern European surname to the Hebrew-ised Ravina), in a review of oud player and composer Ezra Aharon/Azuri Effendi published in the Hebrew daily Davar (Rabinovitch (Ravina) Citation1936). Rabinovitch’s review followed a broadcast he heard on the British Mandate’s Jerusalem-based radio station.Footnote5 In this broadcast Aharon appeared with three Hebrew poems he had composed and arranged for an Arabic takht (ensemble); two by Chaim Nachman Bialik, and one by the poet-lyricist Emanuel Harusi. Both poets originated in Eastern Europe and were part of the vanguard of Zionist artists and intellectuals for whom developing a vibrant modern Hebrew culture was wrapped up with developing the modern Jewish nation; Bialik has since been canonised as Israel’s national poet.

At first glance, the cultural and racialised tensions evoked by Rabinovitch—embedded in the encounter between East and West occurring in British Mandate era Palestine—may seem to simply present an early example of what has become one of the most long-lasting and painful ethnic cleavages in Jewish-Israeli society: that between Ashkenazim (Westerners) on the one hand and Mizrahim (Orientals) on the other. Ashkenazim, Jews originating in Central and Eastern Europe, were the hegemonic group that launched and charted the course of the Zionist movement and the establishment of the State of Israel. The term Mizrahim denotes a panethnic collective that had, over time, coalesced into an overarching label defined vis-à-vis the Ashkenazi Jewish Other. It includes Sephardim—descendants of Jews exiled from Spain in the fifteenth century who formed the core native Jewish population of Palestine—as well as Jews originating in Muslim-majority countries in Asia and North Africa, most of whom arrived following Israel’s establishment (1948), when their countries of origin became inhospitable to Jewish presence.

Readings on the structural inequalities between Ashkenazim and Mizrahim in contemporary Israel, and the tensions they have produced, outline a historical narrative that begins with the arrival of the majority of Oriental Jews following Israel’s establishment (Shohat Citation1988, Citation1999, Citation2003; Yiftachel and Tzfadia Citation2004). They view the conflict between the Palestinian and Zionist national movements—which intensified during the Mandate era—as a prominent angle from which the rejection of Mizrahi culture by the secular Ashkenazi Zionist establishment during the first decades of statehood is to be understood. Rabinovitch’s epithet manifests not only the pre-1948 disparagement of the Ashkenazi elite towards Arab culture, but shows how Arab Jews like Azuri Effendi were ambivalently positioned in the national imaginary already in the 1930s.

While discrimination against Mizrahim and their culture(s) has certainly been pervasive in the Zionist movement, the East/West binary among Jews was created in the context of encounters taking place between different Jewish communities in Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East over several centuries. As sociologist Aziza Khazzoom (Citation2003) argues, Ashkenazi Orientalism is rooted in the Haskala (Jewish Enlightenment) period,Footnote6 during which European Jews became the internal, Orientalised Other in an era of expanding European colonialism, and orientalist discourse and ideas about the Semitic race were becoming central to European thought. In this period Jews in Western Europe were stigmatised as Oriental, Eastern or Asian, and, seeking protection or integration, they came ‘to view Jewish tradition as Oriental, developed an intense commitment to westernisation as a form of self-improvement, and became threatened by elements of Jewish culture that represented an oriental past’ (Khazzoom Citation2003: 482). At the same time, once the Holy Land became a focus of Christian travellers, the colonial impulse also led to the rediscovery of ‘real’ Oriental Jews in the Middle East (Kalman Citation2017). Paradoxically, this Christian rediscovery of the ‘Oriental Jew’ informed European Jewish perceptions of Oriental Jewish culture as more ‘authentic’, and hence, in tandem with the development of the Zionist movement, as a potential resource for Jewish national reawakening.

In many ways then, Zionist Orientalism towards Arabs (and Arab Jews) mirrored the orientalist mixture of admiration and disdain of British attitudes towards Jews, as well as the pull towards ‘authenticity’ rooted in biblical times that temporally vacated Palestine from its non-Jewish history. European images of the Orientals as backwards, lazy, and lacking refinement permeated the Zionist discourse in Palestine as well (Zeruvabel Citation2008). And, as historian Hillel Cohen (Citation2022) writes, the Zionist proposal to the indigenous Sephardim was to accept Zionist dictums, shed their old (Arabised) identity, and adopt a disdainful attitude towards Arabs. At the same time, upon encountering tangible ‘Orientals’ (Bedouins especially but also Yemenite Jews), the Zionist settlers reimagined their culture by selectively incorporating, rejecting, and hybridising elements (real or imagined) of diverse traditions into their new Hebrew culture (Bartal Citation2007; Gerber Citation2012; Halperin Citation2021: 33, 100–5, 166; Saposnik Citation2008).

Arab Orientalism

The rise of European powers and their conquests in the Middle East led some of the Arab elites—many of whom benefitted from their relationships with the colonial authorities—to view ‘the Orient’ as faltering, and Europeanness as representing initiative, liberal modernity, and a return to history. In late Ottoman times this matter was debated abundantly in Palestinian newspapers. These elites viewed indigenous agricultural practices and educational institutions as inferior and wanted to adopt Western pedagogical models and economic practices as a means of arriving at modernity. Emulation of Western dispositions and lifestyle practices also led to growing differentiation between the burgeoning middle class and the peasants (Ambrust Citation1996). In Palestine these elites maintained cultural and social ties with Western culture lovers among the members of first wave of Zionist immigration (1880s) and the Sephardi community (Cohen Citation2022). For Palestinian elites, in a colonial context shifting from the Ottoman empire to the British Mandate, the self-Orientalising gaze, or ‘Orientalism in reverse’, was wrapped up with projects of modernity and national (anti-colonial) awakenings.

Orientalism, cultural formations, and the arts in Mandate Palestine

When Ezra Aharon arrived in 1934, Palestine was undergoing a rapid modernisation and urbanisation process under the baton of the British Mandate, which brought with it a rapid expansion of urban cultural life—cafés, cinemas, salons—in which music featured prominently (Baldazzi Citation2015; Nassar, Sheehi, and Tamari Citation2022; Spiegel Citation2013). The post-war expansion of the urban middle class and the cultural boom that accompanied it was experienced by Jews and Arabs alike, with culture often seen by the British as an arena in which inclusion of both Arab Palestinians and Jews could ameliorate the growing tensions driven by the rise of competing nationalist movements. Yet the British Orientalist gaze, and its attendant preferences, was replicated in the Mandate authorities’ cultural policies and attitudes towards the cultural heritages of different populations in Palestine.

This is evident across a variety of activities. Krik and Bar-Yosef (Citation2021: 6) describe how the Jerusalem Dramatic Society (JDS), an amateur theatrical association that operated from 1921 to 1947, was first envisioned by Jerusalem’s Governor Ronald Storrs as a society that would bring Arabs and Jews ‘into contact with each other and with the governing race’.Footnote7 However, it soon became an insular British project, with Arabs becoming absent from the society’s annals by the mid-1920s, and Jews remaining present only occasionally, both on and offstage. Community outreach efforts became about promoting the English language as a civilising and political tool of the British, rather than as a means of fostering coexistence between Jews and Arabs.

The process of establishing both copyright protections and a broadcasting system in Palestine (which finally occurred in 1936) was also encased in orientalist conceptualisations from its inception. As highlighted by Birnhack (Citation2012) and Stanton (Citation2013), Colonel Claude Francis Strickland, author of the first concrete proposals for establishing the radio, viewed the broadcasting system as a political necessity that would subvert Jewish or Arab attempts to establish privately-owned partisan systems, and as part of the civilising mission of the British Empire, particularly vis-à-vis Arab villagers. He presented Jews as urban and advanced, urban Arabs as slower to catch up with modernity, and Arab peasants as rural and old fashioned (Stanton Citation2013: 81–82). For him, village life was backward, simple, dull, and boring, with the lack of evening amusement contributing to criminal and immoral behaviour (Birnhack Citation2012: 196). He also proposed that Arab musical entertainment would rely on recordings from Egypt, while Jews, who could rely on good locally based talent, would provide their own content. This dismissiveness towards Arabic music continued after the Palestine Broadcast Service (PBS) was established; the eventual turn to broadcasting ‘native [Arabic] music’ was based on the wrong assumption that it was unprotected by copyright law or alternatively, unworthy of copyright protection, and hence cheap for the broadcasting system. The final establishment of a local Arabic radio orchestra in 1938 was a means of owning all copyrights (Birnhack Citation2012).

Such ambivalent Orientalist postures were also part and parcel of the Zionist cultural vision, but with specific caveats. The tension between the idea of the East as a model for cultural awakening—a kind of time tunnel linking the present to (a Hebrewised) Biblical antiquity that provides a source of inspiration for modern nationalism—and actual cultural practices, was reflected in cultural production across the arts.

A pertinent example of this tension is evidenced in the approach to ‘Oriental music’ by the aforementioned poet Chaim Nachman Bialik. In 1921 a musical encounter between Bialik and Eastern Jews took place in a synagogue in Istanbul. Following this, in a forward to a collection of Ottoman religious Hebrew poetry sung to Ottoman classical music and titled Songs of Israel in the East (Istanbul, 1921)—Bialik thusly addressed the singers/poets of Istanbul: ‘If Hebrew music aspires to renew itself then undoubtedly it is to this well, the well of Oriental Music, that it should turn to first, and it is from [this well] that [the music] must absorb the energy for its renaissance’. Yet a few months later he complained about the backward level of Hebrew culture he found in Istanbul and prophesised its eventual demise (in a speech during the Zionist congress in Carlsbad, 1–14 September 1921), a critique that sparked severe criticism from Sephardic and Arab Jewish intellectuals. Finally, in a lecture on the ‘Revival of the Sephardim’ he gave on 24 February 1927 to members of the Mizrahi Zionist Party ‘Pioneers of the East’ in Jerusalem, Bialik tried to atone for his earlier misstatements: ‘I believe, that the shape of our [Hebrew] poetry and music will change, because Sephardic poetry also brings in a different rhythm … and incorporates other musical motifs. Because Sephardic poetry is essentially related to music, and vice versa—Ashkenazi poetry is anti-musical’.Footnote8 By advocating the ‘authenticity’ of Oriental (Jewish) music as a source of renewal Bialik here actually rebuffed his own diasporic Ashkenazi (Yiddish) heritage.

Menashe Rabinovitch, whose critique of Aharon is highlighted above, echoed Bialik. Initially Rabinovitch extoled Oriental music as ‘deeper’ than Western music and stressed its importance to the renewal of Hebrew music. ‘The Jew is a person of the Orient … and the [Oriental] music principles and melody are the bases for his music’, he wrote (Rabinovitch (Ravina) Citation1927).Footnote9 Per Rabinovitch such Orientalised Hebrew music could be created only when Jews will live as a free people in their historical Eastern land, tracing a direct connection between national and artistic renewal. Yet a decade later, after hearing Azuri Effendi’s new Oriental Hebrew songs on a 1936 PBS programme, Rabinovitch’s attitude towards Oriental music became more ambivalent, his judgement highly encased in Orientalist framings. One of Azuri’s twenty-five-minute broadcasts included three songs whose verses, to Rabinovitch’s ears, repeated without any variation. Aesthetic pleasure for ‘the Oriental’, Rabinovitch concluded, was located in the act of singing itself and not in the development of the musical piece. And, as he condescendingly conceded, the monotony of Aharon’s performance could be an edifying one, because ‘one has to hear in this phenomenon deepness, seriousness, a candid approach, a soulful one’ (Rabinovitch (Ravina) Citation1936, 8). Rabinovitch was not able to reconcile between conceptualising the Orient as a source of national-artistic revitalisation, with what he heard as lacking expressivity (in the music of Aharon).

There are relatively few sources that underline the impact of Orientalist discourses on Palestinian cultural production. Yet, as highlighted by Nassar, Sheehi, and Tamari (Citation2022: 80) ‘Arab modernity was replete with social contradictions, political rivalries, and class tensions’. Among the burgeoning urban Palestinian middle class, takes on modernity were sometimes implicated in adapting an Orientalist gaze towards Arab culture, or in East–West blends that also represented amalgamations of ‘tradition’ and ‘modernity’. This disposition can be traced back to nahda aesthetics that peaked with the Golden era of classical Arab (tarab) music, a trend that blended traditional Arab musical traditions with elements of Western music, and that sometimes also replicated Western music’s Orientalist musical imaginaries.

The unique diaries of the Jerusalem-based musician Wasif Jawhariyyeh reveal tensions occurring within the shifting musical scene of Jerusalem in the transition between empires caused by the British drive to modernisation and by the new media (records and phonograms in public spaces, musical cinema, artist tours) that brought about the rise of Egyptian musical hegemony across the Arab world, including Palestine (Tamari Citation2000, Citation2012). In some cases, this was accompanied by the internalisation of Orientalist colonial perceptions by the native urban population. For example, the demand stipulated by the head of the Arab music programming at PBS, Yousef Batrouni, that Arab musicians must learn musical notation as a condition for employment at PBS (Sahhab Citation2004; Tarazi Citation2017: 40) conflates Western practices with the pull of modernity, and shows how previous practices, based on oral transmission, have come to be considered inferior.

Navigating different shades of Orientalism: Ezra Aharon/Azuri Harun in Mandate Jerusalem

In 1932 Ezra Aharon/Azuri Effendi, at the time one of the Iraqi court’s most favoured musicians and an international recording artist, was asked to coordinate the delegation representing Iraq at the Cairo Congress of Arab Music. The first large scale forum to systematically discuss the musical traditions of the Arab world, this event drew composers, performers, scholars and musicologists from the entire Arab world, Turkey, Persia, and Europe, becoming a landmark event in the history of ethnomusicology and Arab music (El-Shawan Castelo-Branco Citation1994; Katz, Craik, and Shiloah Citation2015; Qassim Hassan and Vigreux Citation1992; Racy Citation1991; The Cairo Congress of Arab Music Citation2015). All the musicians Azuri Effendi brought with him to Cairo were Jews, except for the Muslim singer (qari al-maqam) Muhammad al-Qabbanji, attesting to the prominence of professional Jewish musicians in Baghdad at the time (see also Warkov Citation1987). Some scholars (Kojman Citation2001; Qassim Hassan and Vigreux Citation1992) contend that Azuri’s representation of Iraq at the conference was inauthentic, as the ‘ūd was not part of the traditional Iraqi ensemble and the recordings do not represent Iraqi traditional music accurately. Yet while the line-up may not have been entirely ‘traditional’ (a photograph taken at the convention showcases an ensemble in transition, with the ūd, a relatively newcomer to Iraqi music, and the qanun next to the traditional santur and the joza, the Baghdadi fiddle), the recordings of the music highlight the ‘heavy’ Baghdadi style, most especially the vocal performances of al-Qabbanchi.Footnote10 This hybridity represents both Azuri Effendi’s transnational leanings, and his deep knowledge of the Iraqi maqam. The ensemble’s performances were certainly taken as ‘authentic’ by notable European scholars and composers who attended the congress, who received the music with much praise and appreciation (Shiloah Citation2003: 451; quoting Bartók [Citation1933] Citation1972).Footnote11 Following this event Harun was further propelled to international stardom.

Yet two years later, Aharon immigrated to Palestine, far away from the centres of Arab cultural production and dissemination, as well as from the blooming career he enjoyed in Iraq. The exact circumstances of Aharon’s departure from Iraq remain unclear. Aharon recounted that he had to flee due to death threats by Arab nationalists precipitated by his acceptance of performance invites from Jewish settlers in Palestine following the Cairo Congress (Shiloah Citation2003). While in Palestine there were much fewer opportunities for an artist like Aharon, as we shall see, having been the star of the Cairo Congress was important to his career in Mandate Palestine as well.

Jerusalem, where Azuri Effendi lived, was home to diverse communities. Muslims consisted of Jerusalem natives, Blacks, Romani, and Mughrabis. The Christian community included Armenians—both Catholic and Orthodox—Greeks, Maronites, Russian Orthodox, Chaldean-Syrians as well Catholics and Protestants originating elsewhere. Among the Jews—the majority population in Jerusalem—were Sephardi, Moroccan, Yemenite, Kurdish, Georgian, Aleppo and Ashkenazi communities; while in the nineteenth century Sephardi Jews were the majority, by the early 1900s, under the patronage of European powers whose nationals received special rights in Palestine, Ashkenazim became the majority (Klein Citation2014a). In the 1930s, an influx of Jewish refugees from Germany greatly buttressed the Zionist-based educational and cultural institutions in the city, including Hebrew University and the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance. By then, Jerusalem was the largest city in Palestine (Klein Citation2014a), and the centre of British administration. Under the British baton Jerusalem underwent rapid development and ‘modernisation’ projects that amplified sectarianism and communal insularity, and that tended to align with Zionist interests (Barakat Citation2016; Dalachanis and Lemire Citation2018; Mazza Citation2018). Despite this alignment, colonial rule and its expanding economy also precipitated the expansion of an educated and highly politicised Palestinian middle class (Abu Hammad and Salameh Citation2019), and paradoxically, at times provided the basis for the continuation of Arab Jewish collaborations and intimacies.

In short, 1930s Jerusalem was at the epicentre of two opposing sociopolitical currents. On the one hand, the struggle between the Zionist movement and the Palestinian national movement was leading to an increasingly polarised public sphere and the ethnonational violence that spurred the 1936–1939 Great Arab revolt. British modernisation and urban planning projects contributed to this growing polarisation. On the other hand, Jerusalem, which had always been a multi-confessional, multilingual and multiethnic urban space, was not only becoming increasingly cosmopolitan, but was also a more integrative space than that suggested by nation-driven historiographies (Horowitz Citation2005; Jacobson and Naor Citation2016; Jawhariyyeh Citation2014; Klein Citation2014a, Citation2014b).

It is important to return here to the position of Arab Jews (Kalmar and Penslar Citation2005)—a community of natives and recent arrivals like Aharon—who shared a common language (Arabic), cultural practices, and oftentimes also residential spaces, business ventures and a sense of belonging with local Arabs. Arab Jews occupied a ‘liminal zone’ in which the tensions between Occident and Orient were amplified by rising ethnonationalisms, and they felt and embodied these tensions most acutely. As we shall see, as a musical agent Azuri Effendi did not recognise the boundaries between Self and Other invoked by the Orientalist gaze (on all its inflections). He was a modernist who drew upon Eastern and Western musical traditions, experimented with a variety of secular and sacred repertoires. He was happy to respond to requests for setting music to lyrics by Zionist poets (in Hebrew), and at the same time, he also accepted a commission for composing an anthem for the Palestinian arts magazine al-Fajr and invitations to compose music for Egyptian films (see below). He was an agent who both crossed and connected multiple cultural and ideological spaces. Mandate Palestine, on its variety of Orientalist gazes, afforded Harun some opportunities as it foreclosed others, as various agents (the aforementioned Rabinovitch/Ravina among them) kept setting boundaries on his musical production. In the following we discuss the various institutions and actors Ezra Aharon engaged with to highlight how the musical imaginaries he created were both propagated and policed.

The Orientalist imagination of the Palestine Broadcasting Service and the British Administration

The Palestine Broadcasting Service began broadcasting on the last day of March 1936 (Stanton Citation2012). At the inaugural broadcast the governor-general of Mandate Palestine—High Commissioner Sir Arthur Wauchope—made a speech in which he stated that the station aimed to serve all the people in Palestine. Yet his speech highlighted two groups in particular: farmers (fellahin), in need of education and modernisation, and music lovers. ‘The Broadcasting Service will endeavour to fill this need and stimulate musical life in Palestine, so that we may see both Oriental and Western music grow in strength, side by side, each true to its own tradition’, he said (Stanton Citation2012: 7). As highlighted by Andrea Stanton, the idea that ‘Oriental’ and ‘Western’ musical traditions needed to develop separately was part of the Orientalist narrative that viewed them as a polarity, despite the diverse Western musical idioms, instruments and practices that had already been adopted by numerous trailblazing musicians, especially in Egypt. Broadcasting hours were also to be divided linguistically into Arabic, Hebrew, and English blocks, creating a linkage between community, language and listening hours that could only naturalise and amplify the idea of two entirely separate communities in Palestine, rather than promoting the interconnectedness among peoples who were accustomed to intercommunal fluidity (Beckles Willson Citation2014; Stanton Citation2012; see also Wallach Citation2011: 139). The development of separate Arab and Jewish sections at PBS meant that Aharon would be relegated to playing Oriental music, usually set to Hebrew texts, on the Hebrew hour, rather than becoming part of the Arab ensembles developed at PBS (see Sahhab Citation2004: 54).

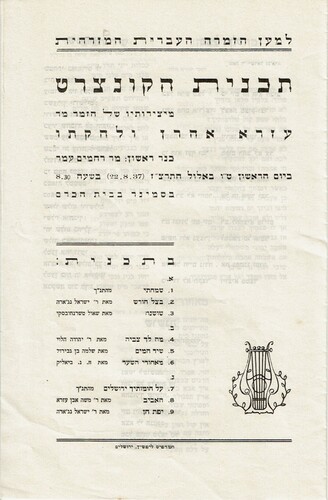

Two days later, on 2 April 1936, Wauchope sponsored a concert at the Eden movie theatre that featured Ezra Aharon and his compositions—most likely in conjunction with the launch of PBS. While those who planned the content for PBS (all British) assumed that it needed to be linguistically and musically divided, Ezra Aharon’s concert programme completely blurred the communal boundaries that such segregation assumed. The programme was printed in three languages (although the Hebrew title was given more space than the English and Arabic translations). Both Hebrew and English versions referenced Ezra Aharon’s Hebrew name, but the Arabic translation referred to him by his Arabic name: Azuri. The musical programme itself was quite varied, beginning with a march (a musical legacy of Western colonial military bands incorporated into Arab art music), followed by a variety of genres. Songs were in both Hebrew and Arabic, interspersed with solo instrumentals. The two Hebrew songs included were Aharon’s Orientalised settings to Bialik’s poems; those in Arabic featured a monologue and a mawwal, and the instrumentals included a taqasim, longa, and sama’i.Footnote12 Other than the Hebrew insertions, this would be a very typical Arab art music programme.

The ensemble Aharon put together was ethnically mixed. Besides him, the soloists included Jaleel Effendi on violin—likely referring to Jaleel Rakab—and the Armenian santur player Artin Santurji, both of whom would become member of PBS’ Arabic Section’s orchestra (Beckles Willson Citation2014). They also included a qanun player by the name of Ya’acub Effendi and the renowned Jewish violinist Rahamim Amar. In short, Azuri Effendi’s multilingual programme, and the fellow musicians who performed with him, defied the ethnic and linguistic segregation that would become the hallmark of PBS. The fluidity of identities Aharon created with this programme permitted a live setting of intercommunal relations that supported the High Commissioner need for promoting coexistence amongst Jerusalem communities, but it also went against the grain of the British Orientalist gaze which formed the basis on which PBS was founded and organised ().

Figure 1. Page 1 of the programme of the concert sponsored by Sir Arthur Wauchope on 2 April, 1936, following the launch of PBS. The Hebrew caption presents Ezra Aharon in his Hebrew name, and highlights that the concert is held under the generous patronage of H. M. High Commissioner to the Land of Israel. The Arabic title presents him as Ustad [Master] Azuri, and highlights the concert is held under the patronage of the High Commissioner to Palestine.

![Figure 1. Page 1 of the programme of the concert sponsored by Sir Arthur Wauchope on 2 April, 1936, following the launch of PBS. The Hebrew caption presents Ezra Aharon in his Hebrew name, and highlights that the concert is held under the generous patronage of H. M. High Commissioner to the Land of Israel. The Arabic title presents him as Ustad [Master] Azuri, and highlights the concert is held under the patronage of the High Commissioner to Palestine.](/cms/asset/02bc0c5d-9c0c-4d6c-8b83-af608a08a1d8/remf_a_2336956_f0001_oc.jpg)

Complicating the academic Oriental/Occidental divide: Ezra Aharon, Wasif Jawharriyeh and Robert Lachmann

Azuri Effendi’s encounter with the German comparative musicologist Robert Lachmann in Jerusalem in 1935 was a prime example of the kind of East–West crucible occurring in Mandate Jerusalem, a product of the colonial setting amplified by numerous forced displacements from other parts of the globe. Lachmann had a deep interest in Arab music and extensive fieldwork experience in North Africa. In 1932 he chaired the Committee on Musical recordings at the Cairo Congress of Arab Music, where he also met Ezra Aharon and documented his playing. In September 1933 Lachmann was dismissed from his position as Music Librarian at the Berlin State Library because he was Jewish (Katz Citation2003). Hoping for a permanent position at the fledgling Hebrew University of Jerusalem established just a decade earlier, Lachmann arrived in Palestine with his technician, recording equipment and personal library of field recordings in April 1935 (Davis Citation2010, Citation2013). It was a chance encounter at a downtown street in Jerusalem that brought Lachmann and Azuri Harun back into each other’s orbit.

These were precarious times for Ezra Aharon, and Lachmann tried to create opportunities for him by sending him students and by recording him on numerous occasions. He did so in his capacity as a comparative musicologist documenting the musical traditions of different communities in Palestine at Hebrew University. Recording Aharon was for Lachmann a means of documenting Oriental urban music—most especially the different maqamat (modes) and instrumental improvisation sections (taqasim)—for the Archive of Oriental Music he was establishing at the university and as part of a series of Oriental music lecture-studio concerts produced for the English section of PBS in 1936–1937 (Davis Citation2010; Katz Citation2003). He also featured Azuri Harun at other lecture-concert events.

For folklorists of Lachmann’s era, oral traditions of (by default) rural and non-Western societies represented spontaneous expressions of the collective psyche of a people; societies were perceived as bounded entities, hybridity as contamination. Comparative musicologists adopted a similar ideology—most especially vis-à-vis Western influenced adaptations. At the closing session of the 1932 Congress of Arab Music in Cairo—a period in which the Egyptian music industry was Westernising at an unprecedented pace—Lachmann had stated that music is ‘the spirit of the nation and can change only when such change emanates from the depths of the very source of that music’ (Davis Citation2010: 5).Footnote13 Such notions about the authenticity of the Other were part and parcel of the Orientalist imagination. In the series of lecture-concerts he produced in Palestine, Lachmann presented Aharon as a distinguished, ‘authentic’ exponent of Arabic music.

Lachmann continued to voice his anxieties about the Westernisation of Arabic music after his move to Palestine (Davis Citation2013, Citation2010). He wrote against the addition of harmony to Oriental melodies and the incorporation of European instruments, practices which were widespread by then and which he viewed as imitative and shallow (Davis Citation2010: 8–9). However, in Jerusalem he was constantly confronted by on-the-ground encounters with musical actors, Jews and Arabs, who were accustomed to intercommunal interaction and cultural amalgamations, and who also associated musical innovations with the urban modernism in which they were enmeshed. One of these actors was Wasif Jawhariyyeh, a Palestinian ‘ūd player, singer and amateur multi-instrumentalist with whom Lachmann developed an intimate relationship (Katz and Craik Citation2020: 60–61 quoting from Jawharriyeh Citation2014). Jawharriyeh became Lachmann’s musical companion in his Jerusalem lectures on Arabic music including at Hebrew University and the ‘Jewish Music Club’ (see Jawhariyyeh Citation2014). In these lecture-concerts Lachmann critiqued the use of Western notation in the performance and dissemination of Arabic music, claiming that the only way to study it was as Wasif had, through one-on-one transmission. This approach to authenticity finally provoked an angry response from Jawharriyeh, who stated that this was a Zionist, anti-Arab point of view aimed at preventing Arabs from evolving and spreading their music (Jawhariyyeh Citation2014: 284–288).

Eventually, Lachmann came to view Palestine, on all the peoples and migrations that converged in it, as a place in which Western and Eastern traditions may be productively fused. He thus presented Aharon’s Oriental musical settings of modern Hebrew poets as ‘a new style with a resonance of its own’ (quoted in Davis Citation2010: 10).Footnote14 It was with Lachmann’s support that Karel Salomon, PBS’ music director, nominated Harun as the head of a section dedicated to Oriental Jewish music (and to the Zionist-oriented project of disseminating Hebrew; Salomon Citation1938). Jawharriyeh was critical of Aharon’s ‘innovative, but malicious idea … of replacing the lyrics of authentic Arabic Andalusian muwashahat with Hebrew lyrics’. Such an attempt, he claimed, was doomed to failure, and rendered Aharon ‘the joke of the other [Arab] musicians’ (Jawhariyyeh Citation2014: 224).Footnote15 As seen above, Jawharrieyh favoured experimenting and modernising in other contexts, and it is perhaps the nationalist-Zionist intervention associated with this new style that caused his need to police the boundaries of the Orient in this case.

The association for Oriental Hebrew Song: Hebrewising and nativising ‘The Orient’

The idea to create Oriental musical settings to modern Hebrew (and Zionist-oriented) poetry—which became a regular part of PBS’ Hebrew hours programming produced by Aharon and titled ‘Sounds of the East’—was first brought up by David Yellin. A Jerusalem-based public figure, scholar and educator born to prominent families of the old Yishuv (Jewish settlement), Yellin was of mixed Polish and Iraqi heritage. Importantly, Yellin was greatly involved with the revival of Hebrew in Palestine. Yellin attended a concert Harun produced in Jerusalem just months after his arrival, in September 1934. He warned Aharon that he would have no Jewish audience for songs in Arabic (Hirshberg Citation1995: 198–9), even though there were many Arabic-speaking Jews in Palestine as well as Palestinian Arab urbanites who were likely to enjoy his music. Clearly, for him the only audience that mattered, was the Hebrew-speaking Jewish audience, and the nation-making pull to which the revival of the Hebrew language in the modern era was yoked.

The Association for Oriental Hebrew Song was founded by Yellin shortly after, and its board included an assortment of Zionist Jews from diverse backgrounds: natives such as David Yellin, Ashkenazim—among them Yitzhak Ben-Zvi and Julia Auster, wife of Daniel Auster, Jerusalem mayor from 1937 to 1938—the Mizrahi poet, journalist and educator David Avisar, and the Jerusalemite Sephardi community leaders David Abadi and Avraham Elmalih (aka Elmaliah, 1885–1967), who was a journalist and member of the Jerusalem city council. Lachmann also joined the group, providing an academic stamp of approval to the endeavour, although he did not adhere to its Zionist leanings (Shiloah Citation2014). The Association was created with the primary goal of supporting Aharon, so that he could become the facilitator of the Oriental card in the construction of the new (nationalised) Hebrew culture in Palestine. While the idea of recruiting Oriental music as a resource for the rebirth of Hebrew permeated Zionist circles earlier, in the mid-1930s Azuri offered them the authority of his recognition in the Arab world as an excelling artist.

Correspondence of members of the Association’s board with Aharon and others echoes the romanticised British ‘Biblical Orientalism’ that is here put in the service of the Zionist cause. For example, an undated letter designed to attract material support for Harun’s Hebrewised Oriental work states that:Footnote16

‘When the Lord restores Zion’s fortunes’ [Psalm 126:1], the people of Israel return to their culture, their language, and the sources of creation, and it is [hence] time we return to the sources of the Hebrew Song and music. It is time that the returnees from diaspora will turn their ear to the sounds of the Orient, the songs of the different Jewish communities in the land of Israel, and maybe we will hear from them the echo of the ancient Hebrew song …

By the rivers of Babylon, the exiles hung up their harps because they did not want to sing the Lord’s song in the land of exile [paraphrase of Psalm 137, 1-3] … and it is from the rivers of Babylon that Ezra Aharon came to us and has reminded us with his original works, of the songs of the Levites at their podium …

We trust that your artistic sentiments and goodwill will come to the aid of any artist and creator and together will lift the voice of the Lord over the mountains of Zion.Footnote17

To foster its agenda, the Association produced public events as well as receptions at the private homes of prominent public figures. The musical programme of a concert sponsored by the Association sharply with the programming of the reception at the High Commissioner, in concordance with the sociopolitical framing of the association’s goals. In this programme, the Arab and the English titles have been erased, and the programme does not include even one solo taqsim—an instrumental improvisational genre that was a staple of his performances (and of all Arab art music performances)—by Aharon. Music in the context of the Association becomes a means for imagining the only kind of place Arab Jews can occupy in the Zionist context—as facilitators of the project of nativisation in ‘The East’ ().

Figure 2. Page 1 of the concert programme presented by the Association for Oriental Hebrew Song on 22 August, 1937. The programme includes Ezra Aharon’s musical settings of medieval and early modern religious Hebrew poetry (Shlomo Ibn Gabirol, Yehuda Halevi, Moshe Ibn Ezra and Israel Najara) as well as contemporary Hebrew poets associated with the Zionist movement (Chaim Nachman Bialik and Shaul Tchernichovsky).

This project gets actualised on a weekly basis in Ezra Aharon’s ‘Oriental Hebrew Song’ slot on the PBS Hebrew section. Enthusiastic reviews of Aharon’s new works by the distinguished Sephardic author Yehuda Burla (who at times communicated with Aharon in Arabic rather than Hebrew) are symptomatic of how native Oriental Jews have by then internalised an Orient that is subservient to the Zionist cause. In this new equation, there is no room for the non-Jewish natives—Palestinian musicians and audiences. Arab music with Hebrew texts becomes the means for the forging of an imagined Jewish nativity in the East.

Interestingly, Harun’s letters to the board members seem to show that he has come to see himself as the very agent that they have set him up to be. For example, in a letter to Yehuda Burla dated 22 July 1936 he writes:

The Oriental Hebrew music is a tremendous thing of great importance. Its value is here in the land of Israel, also known as ‘Land of the East’. Every Jew must sustain this gem and revive it in the period of our national revival, [in order] to bring to us [back to] the days of our fathers and the times of King David, who was the nobleman of Oriental poetry and music.

Seeing that there is no hope for Jews living in diaspora, I decided to settle in the Land of Israel, which is the hope of any nationalized Jew. In this free atmosphere [that exists in] the country I will be able to bring the lost Oriental Hebrew music to the hearts [of the Jewish public].Footnote18

However, Azuri’s correspondences and collaborations with non-Jewish Arab actors, both in Palestine and elsewhere, alongside the commissions they have generated, suggest that such acquiescence may have been more a strategy of survival than a matter of ideology.

Beyond Zionist imaginaries of the Orient: Azuri Effendi’s networks and collaborations with Palestinians and the wider Arab world

Azuri Effendi’s persistent relationships with the wider Arab world and with local Palestinians throughout the Mandate era indicate that he has never ceased to see himself as an integral member of an ideational and cultural (pan-) Arab milieu. His correspondences highlight the respectful and oftentimes intimate relationships he maintained with Arab colleagues from Palestine and beyond, despite the growing ethnonational divide in Palestine. For example, a letter dated 9 June 1935 from Zuhdi Al-Saqqa, one of the owners of the Jaffa-based social and literary magazine Al-Fajr, thanks him in the name of all Al-Fajr partnersFootnote19 for the work he composed for the magazine—the Al-Fajr March—and for other pieces of poetry he set to music; Al-Saqqa signs the letter off as ‘your brother’. Another letter from Egyptian film producer Michel Talhami sent to Aharon on 12 November 1942 opens as follows:

Dear Brother Azuri,

After peace and greetings, I hope, God willing, you, your wife, and your brothers will be with all the best and healthy. I would have liked to write you before then if I hadn’t been busy all this time. But God willing, soon I will tell you things that will please you very much. Perhaps I will return to Palestine early next month, and then I will give you glad tidings that will be pleasing.Footnote20

And, despite the increasing segregation imposed by both British and Zionist policies and the ethnonational conflict such policies fuelled, Azuri’s continued collaborating with fellow Arab and Palestinian musicians throughout the Mandate period. Often propelled by a shared drive for experimentations in East–West amalgamations, such projects represented an aesthetically rendered modernity that did not prescribe to Orient-Occident borderlines, but which followed contemporary trends in cosmopolitan Arab centres like Cairo. This is most evident in the ensemble al-Firqah al-Haditha (‘The New Ensemble’) Harun participated in from 1941 until 1948, which included 9 or 10 Palestinians, six German musicians (refugees who, like Lachmann, escaped to Palestine in the 1930s), and one Yemenite Jew; a mixed chorus also performed with the ensemble (Warkov Citation1986).

The scores notated by Azuri Effendi show that al-Firqah al-Haditha’s modernistic experimentations included the addition of accordion, bassoon, and other western instruments to the Arab takht, with music set to lyrics by poets from Palestine and the larger Arab world. A good number of the Palestinian members of the ensemble were colleagues from PBS who due to PBS policies were assigned to the Arabic section while Harun was assigned to the Hebrew section. Among them was the acclaimed composer and oud player Rawhi al-Khammash, who in 1948 would become a refugee and settle in Iraq. In an ironic play of history, al-Khammash would dedicate his life to developing a modern musical infrastructure for the country, in the aftermath of the post-1948 Iraqi Jewish exodus to Israel and the gaping musical void it left behind.

Conclusion

Azuri Harun/Ezra Aharon crossed all ethnic, political, and religious borderlines in his quest for music making and for securing a living, while operating in an increasingly volatile social environment. An uprooted immigrant perforce or by design (even his motivations to relocate are blurred by contrasting stories), his activities during this period point us to the multidirectional modes by which cultural identities were conceptualised and performed in Mandate Palestine—where ‘East’ and ‘West’ both overlapped and collided in multiple ways—through music making. Azuri Effendi navigated divergent inflections of Orientalism. He recreated and consolidated such inflections in song and music, while at the same time, he transgressed the segregation implied by, and embedded in, the Orientalist gaze.

In his endeavour to accommodate a new and evolving social reality, Harun followed several musical and career-oriented paths while navigating between Palestinian, Jewish, and British interests in Mandate Jerusalem. He maintained a steady stream of modern Arab musical creativity motivated by a passionate drive for music making and the need to survive economically—as expressed in numerous correspondences. ‘The Orient’ as a concept, idea, and/or political ideology was entwined with all these musical activities. In serving different sociopolitical interests in Palestine, Harun musically articulated the Orient in ways that supported divergent Orientalist perspectives. For the British government in Palestine, Azuri crafted musical programmes that bridged the ethnonational divide, and hence also ‘East’ and ‘West’, via the use of both Hebrew and Arabic and the multi-ethnic makeup of the ensemble, to the delight of the colonial authorities. At the same time, Azuri also served the segregationist project on British PBS, which deployed the power of modern technology aimed at controlling the emerging national sentiments of Palestinians and Jews through a division of musical labour (Stanton Citation2013). Yet, as we have seen, the ‘Orient’ remained a dominant pole of attraction for both the Arabic and Hebrew programming of the PBS and hence could also be harnessed to inclusive ends.

Many members of the Jewish elite in Palestine adopted Aharon wholeheartedly as the representative of the finest music of the Orient and opened many doors for him. The correspondence initiated in the summer of 1936 by Yardena Cohen (1910–2012)—a leading proponent of Israel’s modern dance—after hearing Aharon on the radio, is exemplary. Cohen defined herself and her work as ‘Oriental’ and looked to Aharon to supply ‘elevated’ music to accompany her productions instead of the ‘primitive’ Oriental music available to her until then.Footnote22

To be embraced by Zionist institutions and their national aspirations, Ezra had to pay a price: he had to base his musical productions on Hebrew language and literature. He did so with enthusiasm and adopted the narratives of Oriental musical antiquity that his sponsors promoted. Yet when collaborating with Robert Lachmann, who represented the academic authority of European musicology, Azuri became a paragon of classical Arabic music, a pure and noble artistic expression that the German Jewish Orientalist perceived as being endangered.

From Jahariyyeh’s testimony, it seems that Palestinian musicians held ambivalent positions with regards to Azuri whose alignment with the Zionist establishment and attendant musical productions created certain uneasiness, especially considering the tensions that the 1936–1939 Great Arab Revolt created in Jerusalem at the time. Yet, 1941 finds Ezra Aharon participating in the al-Firka al-Haditha, or ‘New Orchestra’ of PBS, an ensemble consisting of Palestinian Arabs and European musicians. This created an ephemeral space for musical collaboration and experimentation between Palestinians and Jews all of whom were driven by musical innovation and modernist trends.

For just over a decade, Azuri Harun/Ezra Aharon created a network of musical interactions in British Palestine in which Oriental imaginaries played a crucial role. His case study shows us that constructions of the Orient were not the exclusive realm of the Western imagination imposing its perceptions of the Orient via the colonising enterprise. Oriental actors such as Aharon exercised their agency in developing a musical aesthetic circumscribed by diverse conceptions of the Orient. Azuri Effendi’s cosmopolitan Arabic musical capital contributed to the Orientalist visions of Zionist elites, catered to the British colonial imaginary, addressed the Orientalist concerns of comparative musicology, and contributed to a modern musical pan-Arabism enmeshed in its own perceptions of the Orient.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nili Belkind

Nili Belkind is a Research Fellow at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. She holds a PhD in Ethnomusicology from Columbia University (2014). Her geographic specialisations include the Middle East—with a special focus on Palestine/Israel—and the Caribbean. Her award-winning book (ICTM 2022) Music in Conflict: Palestine, Israel and the Politics of Aesthetic Production (Routledge 2022) studies the complex relationship of musical culture to political life in Palestine-Israel, where conflict has both shaped and claimed the lives of Palestinian and Jews. She had published articles or book chapters on topics such as music and: urban regeneration (2019); the construction of diasporic imaginations (2016 and 2024); cultural intimacy across ethnonational conflict (2021); social movements (2013) and cultural diplomacy (2010 and 2021). Prior to her academic career Nili spent many years working in the music industry as an album producer, label manager, A & R, radio DJ and other roles.

Edwin Seroussi

Edwin Seroussi is the Emanuel Alexandre Professor Emeritus of Musicology at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Chair of the Academic Committee of the Jewish Music Research Centre, Visiting Scholar at Dartmouth College and, in 2023/4, Fellow at the Herbert G. Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. His research focuses on Jewish music of the Mediterranean and Middle East and its interactions with Islamic cultures, Judeo-Spanish song and music in Israel. He explores processes of hybridisation, diaspora, nationalism and transnationalism in diverse contexts and historical periods such as the Ottoman Empire, colonial Morocco and Algeria, Germany’s Second Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Judeo-Spanish-speaking diaspora. His most recent publication is Sonic Ruins of Modernity: The Sephardic Song Today (Routledge, 2023).

Notes

1 Groundbreaking research on Ezra Aharon was carried out by Warkov (Citation1986, Citation1987) and Shiloah (Citation2003). Both scholars had the opportunity to meet the musician at a time when he was already retired and largely forgotten. Their perceptions reflect their intimate acquaintance with the artist as well as their partial access to some archival materials that Aharon provided them. Much of the material presented here, however, is based on previously unpublished primary sources found in the expanded archive of Ezra Aharon that Warkow and Shiloah did not have access to and is now available at the National Library of Israel as well as on recordings and big data gathered from sources that were not within reach to our predecessors. Access to these new sources as well as novel theoretical perspectives enable us to ask a new set of questions linking the musical practices that emerge from the materials related to Aharon to the sociopolitical settings in which he operated.

2 See Bar-Yosef (Citation2005) for a thorough unpacking of this process.

3 ‘Evangelical philosemitism’ references an ‘evangelical mindset’ among nineteenth-century British Protestants who promoted ‘the idea of the ‘restoration’ to Palestine’ and the ‘teaching of esteem’ toward the Jews. It is based on the idea that the Jews are ‘God’s chosen people’ and that therefore ‘any mistreatment of Jews’ must be countered. This approach contradicted prevailing Christian attitudes, Catholic and Continental Protestant, towards Jews (Lewis Citation2010: 8, 12).

4 See also Anderson (Citation2017); Essaid (Citation2014); Forman and Kedar (Citation2003); LeVine (Citation1995); Nadan (Citation2003). Jacob Norris (Citation2013: 2) for example, suggests that ‘[British] colonial development was more interested in infrastructure and the exploitation of resources to bolster the imperial economy. It was in this light that Palestine was viewed for much of the first half of the twentieth century: a promising new frontier for colonial development that possessed an attractive combination of natural wealth and a prime geographical location’. Norris (Citation2013: 12) also highlights how ‘colonial policymakers in Whitehall frequently expressed great confidence in the transformative power of industrial capitalism, trumpeting the mandate administration's success in instigating a new age of technological modernity in Palestine and casting Zionist settlers as the drivers of that development on the ground’.

5 Palestine Broadcasting System (PBS) was established by the Mandate authorities in March 1936.

6 For Khazzoom, this period begins in the eighteenth century and intensifies during the nineteenth century.

7 The racialised discourses of the colonial authorities have also been analysed by Yair Wallach (Citation2023) who claims that British and international policy makers regarded (European) Jews as a non-European, Semitic race. This led them to view Jewish Zionist migrants and native Palestinian Arabs as somewhat comparable groups. Rather than viewing the rising conflict in Palestine as a clash between European settlers and Arab natives, they conceptualised it as one that is occurring between two nations living side by side.

8 Quotations from Bialik’s lectures appear on his collected writings online, http://benyehuda.org/bialik/. See also Seroussi (Citation2009).

9 Rabinovitch’s statements in this respect (as other similar ones discussed below), bear the imprint of earlier ideas expressed by musicologist, composer and educator Abraham Zvi Idelsohn (e.g., Bohlman 2008: 79) who was greatly interested in what rendered the musical traditions of Jewish communities in Palestine specifically ‘national’ and distinct from other peoples. Idelsohn was one of Rabinovitch’s most admired mentors (see Rabinovitch [Ravina] Citation1938).

10 See all the recordings made at the Cairo Conference of Arabic music at The Internet Archive, with the Iraqi delegation performances listed under Ensemble of Muhammed al-Qubbânji and ‘Azzûri al-‘Awwad. https://archive.org/details/13.PsaumeDeLaTristesse/Congr%C3%A8s±de±musique±arabe±du±Caire±(The±Cairo±congress±of±arab±music)±-±1932±%5BBNF±01±CD-01-18%5D±(2015)/CD±11/10.±Suite.flac.

11 According to Amnon Shiloah (Citation2011: 279), ‘composers Bela Bartók and Paul Hindemith and musicologists Robert Lachmann, Curt Sachs and H. G. Farmer, elected Aharon as the best musician present, and Bartok wrote a complimentary review of the ensemble’. We do not know whether Shiloah had gathered this information from Aharon, with whom he worked intermittently, or whether Shiloah had other sources for this information besides Bartók.

12 The mawwal is an improvisatory genre of Arab vocal music without a clear beat that usually serves as an introduction to a song and is characterised by extended vocalisations. Taqasim is an instrumental improvisation without clear beat that appears as an introduction to, or interlude within, a musical work (instrumental or vocal) and may also stand on its own as an independent composition. Longa is a Turkish instrumental music genre of Romanian origins characterised by lively rhythms and fast tempi. Sama’i is yet another Turkish genre of instrumental music in the rondo form, that is characterised by the use of the usul (rhythmic cycle) 10/8 also called sama’i. Both the sama’i and the longa entered Arabic music following the spread of Ottoman culture throughout the Arab world.

13 Lachmann was perhaps unaware that the recordings he had made of the Iraqi delegation to the Cairo Congress of Arabic music were of Iraqi maqams set to an Egyptian-inspired lineup that included the ‘ud, an instrument that had become popular in Baghdad after WWI. At the same time, Lachmann’s work with Aharon formed the basis for a systematic investigation of the maqamat (melodic modes) in urban Arab music (Davis Citation2013).

14 See also Davis (Citation2022) for the change in Lachmann’s perspectives following his sojourn in Palestine.

15 Setting religious Hebrew lyrics to extant Arab melodies was a long-established practice among Jews in the Middle East since at least the late-sixteenth century. See Najara (Citation2023, vol. 1: 155–65). The novelty of Aharon consisted in adapting to Arab melodies also non-religious Hebrew poetry. The non-Jewish Arab musicians in Jerusalem were probably unaware of this practice.

16 NLI (National Library of Israel), MUS (Music Archive no.) 294, (Item no.) D 022. The letter is addressed to ‘whom it may concern’ and signed by board members David Yellin—who probably wrote it—Yizhak Abadi and David Avisar.

17 NLI, MUS 294, D 023. Also addressed to the general public, this letter is signed by David Yellin, Israel Ben-Zeev and David Avisar, in the name of the Association for Oriental Hebrew Song.

18 NLI, MUS 294, D 048.

19 These included Palestinian novelist and journalist Aref Al-Azuni and writer and literary critic Mahmoud Seif Al-Din Al-Irani.

20 NLI, MUS 294, D 050.

21 NLI, MUS 294, D 052 and 053.

22 NLI, MUS 294, D 033.

References

- Abu Hammad, Ahmad and ‘Ala M. Salameh. 2019. Urban and Cultural Transformations in Jerusalem Since 1930. Urban Transformation in the Southern Levant, Vol. 3. Palestine: Birzeit University and Bergen University.

- Al-Azm, Sadik Jalal. 2000 [1980]. ‘Orientalism and Orientalism in Reverse’. In Orientalism: A Reader, edited by Alexander L. Macfie, 5–26. New York: New York University Press.

- Ambrust, Walter. 1996. Mass Culture and Modernism in Egypt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Anderson, Charles. 2017. ‘The British Mandate and the Crisis of Palestinian Landlessness, 1929–1936’. Middle Eastern Studies 54 (2): 171–215.

- Baldazzi, Cristina. 2015. ‘Time Off: Entertainment, Games and Pass Times in Palestine Between the End of the Ottoman Empire and the British Mandate’. Oriente Moderno 95 (1–2): 173–92.

- Barakat, Rana. 2016. Planning Jerusalem: Urban Planning, Colonialism and the Pro-Jerusalem Society. Beirut: Institute for Palestine Studies. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11889/2741.

- Bartal, Yisrael. 2007. Kozak u-Bedui: ‘am’ ve-‘Arets’ ba-Leumiyut ha-Yehudit (Cossak and Bedouin: ‘people’ and ‘Land’ in Jewish Nationalism). Tel Aviv: Am Oved.

- Bartók, Béla. 1976 [1933]. ‘At the Congress for Arab Music–Cairo 1932’. In Béla Bartók Essays, edited by Benjamin Suchoff, 38–9. London: Faber & Faber. Originally published as ‘Zum Kongress für Arabische Musik–Cairo 1932,’ Zeitschrift für Musikwissenschaft 1/2(1933): 46–48.

- Bar-Yosef, Eitan. 2005. The Holy Land in English Culture 1799-1917: Palestine and the Question of Orientalism. Oxford: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press.

- Beckles Willson, Rachel. 2014. ‘Foreword: Hearing Palestine’. In The Storyteller of Jerusalem: The Life and Times of Wasif Jawhariyyeh, 1904–1948, edited by Salim Tamari, Issam Nassar, translated by Nama Elzeer, ix–xvi. Northampton, MA: Olive Branch Press.

- Birnhack, Michael D. 2012. Colonial Copyright: Intellectual Property in Mandate Palestine. Croydon: Oxford University Press.

- Bohlman, Philip V. 2008. Jewish Music and Modernity. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Broich, John. 2013. ‘British Water Policy in Mandate Palestine: Environmental Orientalism and Social Transformation’. Environment and History 19 (3): 255–81.

- Chatterjee, Kumkum and Clement Hawes. 2008. ‘Aperçus’. In Europe Observed: Multiple Gazes in Early Modern Encounters, edited by Kumkum Chatterjee and Clement Hawes, 1–35. Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press.

- Cohen, Hillel. 2022. Son’im, Sipur Ahava: ‘Al Mzrahim ve-’Aravim (ve-Ashkenazim Gam) me-Reshit ha-Tzionut ve-‘Ad Meoraot 2021 (Enemies, a Love Story: Mizrahi Jews, Palestinian Arabs and Ashkenazi Jews, from the Rise of Zionism to the Present). Rishon LeZion: Ivrit.

- Dalachanis, Angelos and Vincent Lemire. 2018. ‘Introduction: Opening Ordinary Jerusalem’. In Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940. Open Jerusalem, Vol. 1, edited by Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire, 1–10. Boston, MA: Brill.

- Davis, Ruth F. 2010. ‘‘Ethnomusicology and Political Ideology in Mandatory Palestine: Robert Lachmann’s ‘Oriental Music’ Projects’’. Music and Politics 4 (2): 1–14.

- Davis, Ruth F. 2013. Robert Lachmann: The Oriental Music Broadcasts, 1936-1837–a Musical Ethnography of Mandatory Palestine. Middleton, WI: A-R Editions Inc.

- Davis, Ruth F. 2022. ‘Cycles of Encountering: Revisiting Robert Lachmann’s Oriental Music Project in Mandatory Palestine’. In Music and Encounter at the Mediterranean Crossroads: A Sea of Voices, edited by Ruth F. Davis and Brian Oberlander, 222–39. London: Routledge.

- El-Shawan Castelo-Branco, Salwa. 1994. ‘‘Change in Arab Music in Egypt: A Major Issue in the 1932 Congress of Arabic Music’’. In To the Four Corners: A Festschrift in Honor of Rose Brandel, edited by Ellen C. Leichtman, 71–8. Warren, MI: Harmonie Park Press.

- Essaid, Aida. 2014. Zionism and Land Tenure in Mandate Palestine. New York: Routledge.

- Evri, Yuval, Orit Bashkin, Nancy E. Berg and Yoram Meital. 2021. ‘Tugat ha-Filologim ve-Kishlei ha-Nisayon Likbor et ha-Zehut veha-Tarbut ha-Yehudit-Aravit’ (‘The Philologists’ Sorrows and the Failure of Attempts to Bury Arab-Jewish Identity and Culture’). Jama’ah 25: 353–78.

- Forman, Geremy and Alexandre Kedar. 2003. ‘Colonialism, Colonization, and Land Law in Mandate Palestine: The Zor al-Zarqa and Barrat Qisarya Land Disputes in Historical perspective’. Theoretical Inquiries in Law 4 (2): 491–540.

- Gerber, Noah S. 2012. Anu O Sifre ha-Kodesh shebe-Yadenu?: ha-Gilui ha-Tarbuti Shel Yahadut Teman (Ourselves or Our Holy Books?: The Cultural Discovery of Yemenite Jewry). Jerusalem: Ben Tzvi Institute.

- Halperin, Liora R. 2021. The Oldest Guard: Forging the Zionist Settler Past. Redwood City: Stanford University Press.

- Hever, Hannan and Yehuda Shenhav. 2010. ‘ha-Yehudim ha-Aravim: Gilgulo shel Musag’ (‘Arab Jews: The Metapmorphosis of a Term’)’. Pe'amim: Studies in Oriental Jewry 127 (Spring-Fall): 57–74.

- Hirshberg, Jehoash. 1995. Music in the Jewish Community of Palestine. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Horowitz, Amy. 2005. ‘Dueling Nativities: Zehava Ben Sings Um Kulthum’. In Palestine, Israel, and the Politics of Popular Culture, edited by Rebecca L. Stein and Ted Swedenburg, 202–30. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Jacobson, Abigail and Moshe Naor. 2016. Oriental Neighbors: Middle Eastern Jews and Arabs in Mandate Palestine. New York: Brandeis University Press.

- Jawhariyyeh, Wasif. 2014. The Storyteller of Jerusalem: The Life and Times of Musician Wasif Jawhariyyeh, 1904-1948. Edited by Salim Tamari and Issam Nassar and translated by Nama Elzeer. Northampton, MA: Olive Branch Press.

- Kalmar, Ivan Davidson and Derek Jonathan Penslar. 2005. ‘Orientalism and the Jews: An Introduction’. In Orientalism and the Jews, edited by Ivan Davidson Kalmar and Derek Jonathan Penslar, xiii–xl. London: University Press of New England.

- Kalman, Julie. 2017. Orientalizing the Jew: Religion, Culture, and Imperialism in Nineteenth-century France. Indiana University Press.

- Kamel, Lorenzo. 2015. Imperial Perceptions of Palestine: British Influence and Power in Late Ottoman Times. London: I. B. Taurus.

- Katz, Israel J. and Sheila M. Craik. 2020. Robert Lachmann’s Letters to Henry George Farmer (from 1923 to 1938). Leiden: Brill.

- Katz, Israel J., Sheila M. Craik and Amnon Shiloah. 2015. Henry George Farmer and the First International Congress of Arab Music (Cairo 1932). . Leiden: Brill.

- Katz, Ruth. 2003. The Lachmann Problem: An Unsung Chapter in Comparative Musicology. Jerusalem: Hebrew University Magnes Press.

- Khazzoom, Aziza. 2003. ‘The Great Chain of Orientalism: Jewish Identity, Stigma Management, and Ethnic Exclusion in Israel’. American Sociological Association 68 (4): 481–510.

- Klein, Menachem. 2014a. ‘Changing Research Perspectives on the Changing City’. In Jerusalem: Conflict and Cooperation in a Contested City, Edited by Miriam F. Elman and Madelaine Adelman, 196–216. NY: Syracuse University Press.

- Klein, Menachem. 2014b. Lives in Common: Arabs and Jews in Jerusalem, Jaffa and Hebron. London: Hurst Publishers.

- Kojman, Yehezqel. 2001. The Maqam Music Tradition of Iraq. London: The author.

- Krik, Hagit and Eitan Bar-Yosef. 2021. ‘“Shipwrecked in Jerusalem”: British Amateur Theatre and Colonial Culture in Mandatory Palestine’. The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 50 (1): 113–43.

- LeVine, Mark. 1995. ‘The Discourses of Development in Mandate Palestine’. Arab Studies Quarterly 17 (1/2): 95–124.

- Levy, Lital. 2008. ‘Historicizing the Concept of the Arab Jew in the Mashriq’. Jewish Quarterly Review 98 (4): 452–69.

- Lewis, Donald M. 2010. The Origins of Christian Zionism: Lord Shaftsbury and the Evangelical Support for a Jewish Homeland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mazza, Roberto. 2018. ‘The Preservation and Safeguarding of the Amenities of the Holy City Without Favour or Prejudice to Race or Creed: The Pro-Jerusalem Society and Ronald Storrs, 1917–1926’. In Ordinary Jerusalem, 1840–1940, edited by Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire, 403–22. Leiden: Brill.

- Nadan, Amos. 2003. ‘Colonial Misunderstanding of an Efficient Peasant Institution: Land Settlement and Mushāʿ Tenure in Mandate Palestine, 1921–47’. Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 46 (3): 320–54.

- Najara, Israel. 2023. She’erit Yisrael by Zemirot Yisrael, Edited According to Ms. Cambridge Add. 531.1 with Introductory Essays and Commentaries by Tova Beeri and Edwin Seroussi, 2 Vols. Jerusalem: Ben-Zvi Institute, Rosen Foundation.

- Nassar, Issam, Stephen Sheehi and Salīm Tamari. 2022. Camera Palestina: Photography and Displaced Histories of Palestine. . Oakland: University of California Press.

- Norris, Jacob. 2013. Land of Progress: Palestine in the Age of Colonial Development 1905–1948. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Qassim Hassan, Shéhérazade and Philippe Vigreux. 1992. Musique Arabe: Le Congrès du Caire de 1932. Cairo: Centre d’Études et de Documentation Économiques, Juridiques et Sociales.

- Rabinovitch (Ravina), Menashe. 1927. ‘ha-Yahadut ba-Muziqa’ (‘Judaism in Music’)’. Davar (June 3): 7–8.

- Rabinovitch (Ravina), Menashe. 1936. ‘Kol Yerushalayim’ (‘The Voice of Jerusalem’). Davar (July 27): 8.

- Rabinovitch (Ravina), Menashe. 1938. Avraham Tsevi Idelzon-Ben-Yehudah, 1882–1938 (Abraham Zvi Idelsohn-Ben Yehuda, 1882-1938). Tel Aviv: Hamakhon le-Shi’urei Neginah ve-Tizmoret Merkazit be-Batei ha-Sefer ha-‘Ironiyyim (Center for Music Lessons and City Schools’ Central Orchestra).

- Racy, Ali Jihad. 1991. ‘‘Historical Worldviews of Early Ethnomusicologists: An East-West Encounter in Cairo, 1932’’. In Ethnomusicology and Modern Music History, edited by Stephen Blum, Philip V. Bohlman and Daniel M. Neumann, 68–95. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Sahhab, Elias. 2004. ‘This is Radio Jerusalem … 1936’. Jerusalem Quarterly 20: 52–55.

- Said, Edward. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Said, Edward. 2003. Orientalism (25th Anniversary ed). New York: Vintage Books.

- Said, Edward. 2004. ‘Orientalism Once More’. Development and Change 35 (5): 869–879.

- Salomon, Karel. 1938. ‘Kol Yerushalayim: Music Programmes for Jewish Listeners in Palestine’. Musica Hebraica 1–2: 36–9.