Abstract

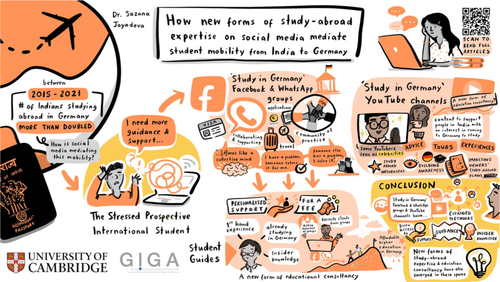

This paper examines new forms of study-abroad expertise on social media and their role in mediating Indian student mobility to Germany. Firstly, it explores how mutual-support Facebook and WhatsApp groups—used by prospective international students in India to support each other through the process of applying to German universities—have contributed to the emergence of new forms of education consultancy, offered by Indian students or graduates of German universities, whom I call ‘Student Guides’. In addition, it shows how some Indians studying in Germany have started ‘Study in Germany’ YouTube channels, aimed at aspirant student migrants, and have become important ‘study-abroad influencers’. The paper analyses how these new forms of study-abroad expertise offer prospective international students social and cultural capital important for successful student migration, apart from shaping their imaginative geographies of Germany, and embedding them in cultures of mobility. Furthermore, the paper highlights how these new forms of study-abroad expertise intersect with, and critique, a more ‘traditional’ study-abroad expert: the professional education consultant. The paper draws on a digital ethnography of ‘Study in Germany’ Facebook and WhatsApp groups and YouTube channels, as well as interviews with the YouTubers, Student Guides, and Indian students in Germany.

Credits: Katie Chappell

Introduction

It is widely acknowledged in the scholarship on international student migration that prospective international students’ social networks and commercially-run education consultancies play an important role in mediating student mobility. Less studied is the significant impact of social media on both of these migration infrastructures, and the implications this has for international student mobility. This paper will contribute to addressing this gap through examining new forms of study-abroad expertise on social media and their role in mediating postgraduate student mobility from India to Germany. More specifically, the paper will explore how mutual-support Facebook and WhatsApp groups—used by prospective international students in India to support each other through the process of applying to German universities—have contributed to the emergence of new forms of education consultancy, offered by Indian students or graduates of German universities, whom I will call ‘Student Guides’. In addition, it will show how some Indians studying in Germany have started ‘Study in Germany’ YouTube channels, aimed at aspirant student migrants, and have become important ‘study-abroad influencers’. The paper analyses how these new forms of study-abroad expertise offer prospective international students social and cultural capital important for successful student migration, apart from shaping their imaginative geographies of Germany, and embedding them in cultures of mobility. Furthermore, the paper will highlight how these new forms of study-abroad expertise intersect with, and critique, a more ‘traditional’ study-abroad expert: the professional education consultant. In doing so, it will make an important contribution to understanding contemporary mobilities, especially from the Global South.

Conceptually, the paper will draw on Xiang and Lindquist’s (Citation2014) concept of ‘migration infrastructure’, which they use to describe the actors, institutions and technologies that mediate migration. They see this infrastructure as being composed of five interrelated dimensions: the social (migrant networks), the commercial (recruitment intermediaries), the technological (communication and transport), the regulatory (state apparatus and procedures for documentation, licensing, training and other administrative processes), and the humanitarian (NGOs and international organisations). They illustrate how, through focusing on the everyday spaces and practices through which migration is organised and negotiated, and examining the intersections between these different infrastructures, a deeper understanding of mobility can be achieved. Following Xiang and Lindquist, in this paper I will illustrate how developments in the technological infrastructure, namely increased access to and use of social media, has impacted both the social and commercial infrastructures mediating student mobility from India. I will argue that understanding the evolving migration infrastructure facilitating international student migration is crucial for understanding contemporary student mobilities, particularly from the Global South.

The structure of the paper will be as follows: I will first outline how existing scholarship on international student migration has discussed the social and commercial infrastructures mediating international student mobility, as well as the impact of social media on these infrastructures. After outlining my research context and methods, I will briefly discuss ‘Study in Germany’ Facebook and WhatsApp groups and how they were used by prospective international students in India to support each other through the process of going to Germany for study, focusing particularly on how education consultants were discussed within these groups. Following this, I will explore new opportunities for education consultancy that have emerged in these groups as well as new forms of study-abroad expertise that have emerged on YouTube. The final section of this article will place these findings in conversation with existing scholarship.

Infrastructures of mobility: social networks, education consultants, and social media

Social infrastructure

Existing scholarship has demonstrated that a prospective international student’s social networks have significant impact on whether they decide to go abroad to study as well as their study destination (Beech Citation2015; Collins Citation2008; Brooks and Waters Citation2010). For instance, having people in one’s social network who have experience of study abroad can make it possible to get explicit advice and guidance about study abroad (Collins Citation2008). It can also lead to the development of cultures of mobility, which can normalise and encourage going abroad to study, as well as influence where one chooses to study (Beech Citation2015). Furthermore, a number of scholars of international student migration have drawn on and developed Said’s (Citation1985) concept of ‘imaginative geographies’ to discuss how prospective international students bring together information acquired through their social networks—among other sources—to construct understandings and imaginings of what study abroad, and even study abroad at a particular country, city, and university might look (Beech Citation2014; Kölbel Citation2020). Such imaginative geographies can have substantial influence on study-abroad-related decisions (Beech Citation2014). In this way we can see decisions about study abroad and student mobility as being relational, embedded within and produced through social networks (Manderscheid Citation2014; Brooks and Waters Citation2010).

As people with greater economic capital are more likely to belong to transnational social networks and be embedded in cultures of mobility, social networks tend to replicate privilege (Beech Citation2015; Brooks and Waters Citation2010). Nevertheless, scholars such as Dekker and Engbersen (Citation2014), writing in the context of migration more broadly, have argued that social media can allow a migrant or prospective migrant to maintain as well as usefully expand their social networks, thereby facilitating migration. Dekker and Engbersen (Citation2014) describe four ways in which this can unfold. Firstly, social media can lower the threshold for migration by helping migrants maintain strong ties with their family and friends. Secondly, it offers an effective way for a prospective migrant to re-establish contact with people to whom they are weakly tied (i.e. their distant acquaintances), who may have useful migration-relevant information. Thirdly, through joining a social media platform, a prospective migrant can connect with others signed up to that platform who are previously unknown to them but to whom they are latently connected through the structure of the social media platform of which they are members—for example, through creating and/or joining communities based on interest rather than prior acquaintance (Haythornthwaite Citation2005). Indeed, it has been argued that weak ties—and latent ties, one might add—may be especially valuable for organising migration, as they link social groups with access to different resources and information (Granovetter Citation1973). Finally, Dekker and Engbersen (Citation2014) describe how some social media platforms are open to everyone and can serve as a public sphere in which non-official, ‘backstage’ (Goffman Citation1959) information relevant to organising migration can be shared. They thus argue that through enabling a prospective migrant to productively expand their social networks and access valuable cultural capital needed for organising migration, social media can both enable and encourage migration.

Returning to the scholarship on international student migration: the possibilities that social media creates for expanding social networks beyond existing contacts, accessing valuable study-abroad-related information, as well as sharing stories and images of study abroad with those back home, have been acknowledged (Beech Citation2014, Citation2015; Kölbel Citation2020). However, only a small number of studies have provided detailed empirical investigations of how social media mediates international student mobility. For instance, Collins (Citation2012a), in his study of student migration from South Korea to New Zealand, offers a fine-grained analysis of how Korean prospective international students, international students, and returnees sought and shared information on study in New Zealand via social media, including through the creation of communities of interest on the topic. He argues that such informal interactions online might be just as important in encouraging student mobility to New Zealand as official promotions by state agencies. Similarly, in another paper, I have explored how ‘Study in Germany’ Facebook and WhatsApp groups brought together prospective international students from India who were previously unknown to each other, enabling them to actively collaborate and support each other through the process of applying to German universities (Jayadeva Citation2020). In this paper, I will further contribute to analysing new intersections between the technological and social infrastructures mediating student mobility, through exploring how Student Guides on Facebook and WhatsApp, and Study-Abroad YouTubers, enabled students to widen their social networks, and to what effect.

Commercial infrastructure

A key actor in the commercial infrastructure mediating student mobility is the education consultant or agent.Footnote1 Education consultants play a pivotal role in shaping international student migration, including influencing the destinations to which students travel for study (Collins Citation2012b; Beech Citation2018). They provide prospective international students guidance with selecting and applying to universities abroad, and many offer assistance with preparing for tests like the IELTS (International English Language Testing System) and GRE (Graduate Record Examinations), applying for visas, and organising travel and accommodation—what some Indian consultants refer to as ‘A to Z processing’ (Jayadeva and Thieme Citation2022; Collins Citation2012b). It can be argued that education consultants too, like prospective international students’ social networks, contribute powerfully to the imaginative geographies these students build about study abroad. With higher education constituting a key export industry for many countries in the Global North, universities commonly partner with education consultants, paying these consultants a commission for every student they recruit on the university’s behalf (Beech Citation2018).

Despite their key role in mediating international student mobility, there has been relatively limited scholarly attention focused on education consultants (Beech Citation2018; Tuxen and Robertson Citation2019). The studies that exist have examined a range of topics—from education consultants’ engagements with prospective international students (Collins Citation2012b; Tuxen and Robertson Citation2019), to the evolving relationships between governments, universities, and education consultants (Collins Citation2012b; Beech Citation2018), to consultants’ initiatives to professionalise their service (Thieme Citation2017). Some of this existing research has highlighted instances of problematic conduct by education consultants towards the students who seek their services, from engaging in outright fraudulent and exploitative practices (Fittante Citation2023; Adhikari Citation2010) to being profit-driven actors who place their business interests before their clients’ interests (Marom Citation2023; Kölbel Citation2020). Students with limited knowledge of overseas education have been discussed as especially vulnerable to being misled and manipulated by these actors (Tuxen and Robertson Citation2019). However, consultants have also been discussed as providing students with valuable information, support and guidance needed to successfully go abroad to study (Collins Citation2012b; Thieme Citation2017).

Research on education consultants has presented different perspectives regarding from where education consultants’ expertise is seen to arise. In some studies, consultants’ expertise and the trustworthiness of their guidance is seen to stem from first-hand experience with education migration (Collins Citation2012b). Other studies, however, have shown that education consultants will not have necessarily studied or even travelled abroad themselves, or visited the universities they partner with or promote (Beech Citation2018). Yet, they may nevertheless be valuable middlemen because they hold the same cultural and local understanding as the students, which may help them gain students’ trust (Beech Citation2018). In their study of the brokerage of international higher education in Mumbai, India, Tuxen and Robertson (Citation2019) draw a distinction between ‘education agents’ and ‘education counsellors’: while education counsellors were more elite actors with first-hand experience of study abroad, which they believed offered them superior insight into study abroad, education agents did not have the economic capital that was necessary to acquire such experiential knowledge of overseas education. Although my interlocutors did not make distinctions between different categories of education consultants in India (beyond broad distinctions between ‘genuine’ versus fraudulent consultants), questions of what constituted study-abroad expertise were central both to critiques of ‘traditional’ education consultants that circulated in the social media communities I studied, and to the ways in which Student Guides and ‘Study in Germany’ YouTubers presented themselves, as I shall describe in this paper.

This paper will contribute to the scholarship on education consultants by exploring how the technological infrastructure—and new intersections between the social and technological infrastructures—have impacted the commercial infrastructure mediating Indian student mobility, and to what effect (Xiang and Lindquist Citation2014). More specifically, the paper will examine how ‘traditional’ education consultants are discussed and perceived by prospective international students and international students from India in ‘study abroad’ social media communities as well as new forms of consultancy that have emerged within these communities. In so doing, the paper will address both the dearth of scholarly attention to education consultancy on social media and add to the emerging body of scholarship on education consultants in India (Tuxen and Robertson Citation2019; Fittante Citation2023).

Research context and methods

The number of Indians studying in Germany has more than doubled between the academic years 2015–2016 and 2020–2021 (DAAD Citation2021, Citation2022), making India the second largest source country of international students at German universities, after China (DAAD Citation2022). The majority of Indians studying in Germany are enrolled on information technology and engineering Master’s courses (DAAD Citation2022). Germany’s increasing popularity as a study destination among Indian students is related at least partly to the fact that German public universities—which constitute the majority of education provision in the country—charge low or no tuition fees, even for international students. Furthermore, in recent years, German universities have started offering a large number of Master’s courses in English, making higher education in the country more accessible to non-German speakers.

The fieldwork for this paper was conducted between 2017 and 2018. Fieldwork was divided into three strands: First, I conducted digital ethnographic fieldwork in four Facebook groups and fifteen WhatsApp groups used by prospective international students, almost all of whom were applying to postgraduate engineering courses in Germany, to navigate the process of going to study in Germany. After obtaining permission from group administrators and introducing my research to group members through a post detailing my project, I observed the daily activity in these spaces and had informal conversations with members about their reasons for wanting to study in Germany and how they were getting along with their applications.

In the course of conducting this digital ethnographic fieldwork, I encountered and subsequently conducted interviews with six Student Guides (SGs), who—as I will explain in greater detail later in the article—supported aspirant student migrants with the process of applying to German universities, for a fee. The SGs I interviewed were all male. One was in the final stages of applying to German universities himself, and was based in India. Three were current students at German universities, while the remaining two had recently graduated from German universities and were working in Germany. My interviews with the SGs explored how they had navigated their own application journeys, how and why they had become interested in becoming an SG, and their activities as an SG thus far. I remained in contact (via WhatsApp or Facebook) with most of these SGs for the whole fieldwork period, even meeting several times for follow-up conversations with one of them. One of these SGs had a WhatsApp group for his clients, which I included in my digital ethnographic fieldwork.

The second strand of fieldwork involved an analysis of the four ‘Study in Germany’ YouTube channels that were active during the time of my fieldwork (one of which was co-run by two students). I watched the videos uploaded on these channels—from the channels’ inception (all the channels had been started in 2017 or 2018) until the end of my fieldwork period—and went through their comments sections to produce an analysis of the videos’ main themes as well as the manner in which viewers (largely aspirant student migrants in India) engaged with the videos and the YouTubers. I also conducted interviews with four of the five YouTubers—three male, one female—all of whom were international students in Germany at the time. These interviews examined how these students had decided to start YouTube channels, their experiences making videos thus far, and their interactions with their audiences.

The third strand of fieldwork, which I draw on only partially in this paper, involved interviews with 36 Indians studying in Germany, four recent graduates, and five applicants, about how they had navigated, or were navigating, the process of going to Germany for study. Only seven interviewees were female, which is reflective of the fact that the majority of Indians studying in Germany are male. The interviewees came from across India. Although everyone described themselves as coming from ‘middle-class’ families, there was a lot of variation in socio-economic background. The majority said that the low-cost education offered by Germany was what had made it possible for them to consider studying abroad, and it would have been unaffordable, or at least very difficult, for them to study in countries like the US or Australia. Only a minority had strong connections to people who were studying at or had graduated from a German university and could offer guidance with navigating the application process. Based on my digital ethnography of the ‘Study in Germany’ Facebook and WhatsApp groups, the background of the aspirant student migrants I met through these groups appeared to be broadly similar to those of the interviewees.

The vast majority of interviews were conducted in person, while some were conducted via Skype. All interviews were recorded with permission and transcribed in full. I analysed my interviews and the fieldnotes from my digital ethnography using ATLAS.ti, drawing on both inductive and deductive approaches. The project was granted ethical approval by the German Academic Exchange Service.

‘Study in Germany’ Facebook and WhatsApp groups

The vast majority of my interlocutors—the students I interviewed in Germany and the prospective international students I met in the social media groups—experienced the process of organising to go abroad for study as complicated and stressful. It involved understanding the education landscape, job markets, and visa policies of various study destinations, and picking one; shortlisting universities and courses that matched one’s interests and to which one had a chance of getting admission; preparing university and visa application documents; writing exams such as the IELTS; obtaining loans (if necessary); and organising accommodation and travel. Successfully completing these various steps required considerable research, preparation, and paperwork.

In this context, ‘Study in Germany’ Facebook and WhatsApp groups had come to be seen as an important tool for navigating the process of going to Germany for study. In what follows, I will offer a brief account of how these groups operated (see Jayadeva Citation2020 for a more detailed analysis), and of the narratives about education consultants that circulated within them, which will serve as important background for the next section on forms of education consultancy that had emerged within these groups.

Started by prospective international students in India or by Indians currently studying in Germany, these groups brought together people in India—previously unknown to each other—who were interested in studying in Germany. At the time of my fieldwork there were several large Facebook groups broadly focused on study in Germany, as well as dozens of extremely specialised WhatsApp groups for people interested in applying to particular universities and courses. Most of my interlocutors were members of one or two Facebook groups and several WhatsApp groups. These online groups functioned as a ‘community of practice’ (Wenger Citation2004), with members actively collaborating and supporting each other through the process of applying to German universities and organising to go to Germany for study. An ethic of encouragement and support characterised the groups. Even when group members were in direct competition for places at universities, they appeared to view each other as allies. They readily shared information with each other and celebrated each other’s victories. In interviews and informal conversations with me, and in exchanges with each other, members typically presented their contributions to the group as being driven by the desire to ‘give back to the group’ or ‘return the favour’.

Some group members, alongside their participation in the groups, had sought or were seeking the services of commercial education consultants based in India. Nevertheless, when consultants were discussed by group members, they were typically portrayed as being very ambivalent actors (see Jayadeva and Thieme Citation2022 for a more detailed analysis). On the one hand, education consultants were discussed by some group members as being established sources of expertise, whose experience of assisting people with applying to universities abroad and whose partnerships with foreign universities could facilitate successful student migration (cf. Collins Citation2012b; Thieme Citation2017). On the other hand, many viewed consultants as engaging in unethical and manipulative practices in order to further their business interests—even when these might be in conflict with their clients’ best interests (cf. Marom Citation2023).

While existing scholarship has noted how partnership models, where universities pay consultants for every student they recruit on the university’s behalf, incentivise consultants to direct students towards the universities with which they partner (Beech Citation2018), the impact of such models on student mobility to study destinations with less marketised higher education systems has not been explored. Given that most German universities charged low or no tuition fees, they did not partner with consultants (and pay them commissions) in order to recruit international students. My interlocutors said that, as a result, many consultants in India did not recommend Germany as a study destination to their clients because the commission they typically received from their partner universities in other countries far exceeded what they could charge a client interested in applying to a German university. Many described how when they had approached consultants to get support with applying to German universities, they had been actively advised against going to Germany, and countries such as the USA, Canada, or Australia had been aggressively recommended to them instead. Consultants who did offer support with applying to German universities would charge a fee (since they were not receiving commissions), which could sometimes be very high. Furthermore, members of the ‘Study in Germany’ social media groups questioned how helpful it would be to use the services of a consultant, given that most consultants lacked both personal experience of study in Germany as well as professional experience with supporting students to study there.

Indeed, a strong anti-consultant narrative had crystallised in the groups through posts written by members detailing their negative experiences with particular consultants and other members’ comments in reaction to such posts, as well as through ‘awareness-raising’ posts about the dangers of using a consultant. Members’ requests for information about good consultants were often met with comment after comment to avoid consultants in general. For example:

Pls dont go for consultant. Because they will only look u as money paying machine. Not as student any more. Better take help from [college] seniors or post in this group, people are ready to help u out.

Student guides

Apart from being mutual-support groups where prospective international students could collaborate on the application process—and despite the anti-consultant narratives that circulated in the groups—the ‘Study in Germany’ Facebook and WhatsApp groups I studied were also marketplaces in which study-abroad expertise could be bought and sold.

After spending significant time in the groups while navigating the process of going to Germany for study, some group members, whom I will call ‘Student Guides’ (SGs), began to offer other group members assistance with this process for a fee. While in most cases, SGs were students or recent graduates living in Germany, some were still advanced-stage applicants themselves. Over the course of my fieldwork, I came across and interviewed six SGs. It was difficult to estimate the total number operating in the groups as they were typically ‘undercover’ (discussed below). SGs varied a lot in how they operated: they might do consultancy work almost full-time, or part-time alongside their studies or work; they might offer ‘A-Z processing’ like a ‘traditional’ education consultancy, or might offer assistance only with some parts of the application process such as helping an applicant evaluate their academic profile and shortlist universities and courses accordingly; they might be one-man shows or might collaborate with other SGs.

On the face of it, the services that SGs offered were similar to those offered by ‘traditional’ education consultants in India (Jayadeva and Thieme Citation2022). However, SGs differed from education consultants in that the social media groups were strongly implicated in how they operated. Most of the SGs I interviewed credited the groups with having helped them acquire expertise in the application process. The large amounts of time which most of them had spent in these groups—typically when they themselves had been applicants—asking and answering questions, viewing other members’ questions being answered, and participating in discussions, were all experienced as having served as an important part of the ‘training’ through which they had developed expertise. In addition, very importantly, all credited the groups with making them aware of the fact that their own lived experience—of the application process and, in most cases, of studying and living in Germany—was highly sought after and could have monetary exchange value.

Moreover, SGs recruited their clients through the groups. Entering a group gave SGs access to a large number of aspirant student migrants, i.e. their potential clients, all conveniently grouped together. Indeed, the groups were viewed as prime real estate; just like having an office in the right part of a city was important for ‘traditional’ education consultants (Collins Citation2012b), being in the right groups was very important for many SGs. The existence of such groups, which brought together people from all over India, meant that SGs could have an extraordinarily large geographical reach. Sitting in Hamburg, one of the SGs I interviewed had clients from villages, towns, and cities across India (and even a few from Pakistan, Egypt and Afghanistan). Apart from participating in Facebook and WhatsApp groups related to study in Germany, some SGs would also enter groups for aspirants interested in study in other countries and then work on diverting these aspirants to Germany. Through participating in the groups, SGs not only connected with aspirants, but often also became aware of each other’s existence, which, in some cases, led to collaborations. Once recruited, all communication with clients typically took place via social media platforms and email.

Finally, the norms of altruistic exchange within the groups—and the related anti-consultant narratives—strongly shaped how SGs operated in two main ways: they did not directly market themselves and they explicitly distanced themselves from ‘traditional’ education consultants in India. I will now discuss these points in turn. Because the groups were characterised by an ethic of altruistic peer support, SGs needed to operate according to this logic in order to be able to recruit clients. SGs who directly advertised their services faced backlash. Instead, most SGs first performed their knowledge and expertise through being a good group member and answering other members’ questions. After becoming ‘visible’ in this way, they would offer, via private messages to individual members, further support for a fee. However, these strategies could still sometimes fail. On several occasions, I saw group members share screenshots of private messages they had received from an SG, as a way of ‘outing’ this person as a consultant and accusing them of sullying the altruistic space of the group with their commercial motivations, as well as rubbishing their claims of offering support beyond what was available through the groups. While many group members were against consultants, in principle, and felt that the groups met their information and support needs, there were some who were happy to pay a ‘genuine’ person for extra personalised support, which is why SGs managed to get business. The group members who used the services of SGs typically felt that they did not have enough time, interest, or confidence to manage all the work involved in organising to go abroad for study by themselves, and were relieved to have an SG supporting them. Some SGs additionally ran their own WhatsApp groups, composed mainly of their own clients, where they could more freely advertise their services.

SGs also took pains to distance themselves from ‘traditional’ education consultants in India. This was done in two main ways. The first way was by emphasising their ‘student’ identity in opposition to consultants, who were discussed as being ‘businesses’. As businesses, consultants were framed as being profit-driven and manipulative. In contrast, SGs presented themselves as being ‘genuine’ and having a friendly desire to help fellow students make use of the opportunity of coming to Germany for study. Some SGs described how they themselves had suffered at the hands of evil consultants and were now keen to protect innocent students from this fate. A second way in which SGs distanced themselves from education consultants was by stressing their ‘insider knowledge’ of the application process to German universities, the German higher education landscape, and student life in Germany, which they presented as stemming from the fact that they were (or had been) international students in Germany and engineers themselves—unlike consultants, who, they argued, typically knew very little about engineering courses, nor had first-hand experience of study and life in Germany.

Here, I will present a case study of one SG, whom I will call AshokFootnote2, who was a student at a German university. Ashok had become an SG after spending substantial time in the ‘Study in Germany’ social media groups as a regular member. At the time that I met him in the spring of 2018, Ashok told me that he had 150 people applying to German universities through him, and was charging each of them 500 Euros for his service. He offered support with everything from shortlisting universities and courses to preparing application documents to organising travel. For clients coming to cities near him, he provided additional support upon arrival. As one of his clients told me, ‘he helped with accommodation and initial part-time job also. [Ashok] also picks up his students [clients] from the airport. It’s very nice. Otherwise it’s scary to come.’ Unable to manage the workload by himself, Ashok enlisted some of his clients—whom he referred to as his ‘boys’—to assist him, giving them discounts in return. Ashok’s boys discreetly promoted his services in the social media groups.

In his interviews and conversations with me, Ashok would discuss how Germany was making study abroad accessible, for the first time, to a lot of people in India who, because of their socio-economic positions, had never imagined they could study abroad. On one occasion, he observed: ‘The problem is that everyone has a place in Germany, but they don’t know how. If they know, then they can come.’ Indeed, Ashok regularly spoke of ‘saving’ various categories of students who had been suffering as a result of the bad job market for engineers in India and had been misled by consultants about their prospects of study in Germany. This included academically weak students who had been told by consultants that they would not get admission at German state universities, and students who had been convinced by consultants to apply to one of the few private fee-charging universities in Germany or a fee-charging university in Eastern Europe (where the consultants received commissions). Ashok cited his insider knowledge of the German higher education system as enabling him to support such students to gain admission at state universities in Germany.

Not all the SGs I interviewed devoted as much time to working as a Student Guide as Ashok, nor charged as much as Ashok did. On the other end of the spectrum was an SG whom I will call Naveen. He was a Master’s student in Germany, and had used the groups to navigate his own application journey. Once he began his postgraduate degree in Germany, he had taken on a handful of clients each semester, charging each one 25 Euros. He offered his clients support with shortlisting universities and courses and provided some feedback on application documents. For Naveen, consultancy work offered useful ‘pocket money’, which allowed him to work fewer hours at his part-time job, and did not interfere with his studies. There were other SGs I interviewed who fell somewhere in between Ashok and Naveen in terms of their scale of operation.

Collins (Citation2012b) argues that in migration scholarship, a distinction is often drawn between agents, who are viewed as profit-oriented and part of the migration industry, and intermediaries, who operate within the social networks of migrants and are seen as altruistic. In contrast, he shows how the Korean education agents in his study of student mobility from Korea to New Zealand could be seen as operating between these worlds. These agents accumulated social capital through a shared ethno-nationality with their clients; through being referred by their clients to others in their networks also interested in study abroad; and through offering their clients support and guidance beyond the services for which they received commissions. It was this social capital that enabled them to contribute to the export education industry. Similarly, the ‘Study in Germany’ Facebook and WhatsApp groups may be seen as offering SGs an unprecedented way and place in which to cultivate social capital and become embedded in networks of prospective international students. As Indian international students in Germany (or prospective international students or recent graduates), SGs could openly join and participate in these networks, accumulating social capital through sharing information and guidance for free and getting to know and be known by others in these groups—which allowed them to develop and carry out their commercial endeavours undercover.

Importantly, while commercial motivations no doubt prompted the work SGs did, they also appeared to enjoy this work and to derive great satisfaction from making aspirant student migrants in India aware of the possibility of affordable higher education in Germany and providing them guidance and support with applying to German universities. Two of these SGs, on their visits home to India, had travelled to universities in smaller cities and towns—from where students would ordinarily be less likely to go abroad for study—and held sessions for undergraduate students on postgraduate education in Germany. They all had significant impact on their clients’ study-abroad-related decisions and applications and contributed to anti-consultant narratives already prevalent in the groups.

‘Study in Germany’ YouTubers

While the services offered by SGs closely resembled those offered by ‘traditional’ education consultants, another different variety of expert guidance came from a handful of what I will call ‘Study in Germany’ YouTubers. Indeed, YouTube was a very important part of the social media constellation that mediated student mobility from India to Germany. At the time of my fieldwork, there were four YouTube channels focused on study in Germany, run by Indians studying at German universities. These YouTubers created content to support people in India with an interest in coming to Germany for study as well as to create awareness about opportunities for study in Germany. Videos made by ‘Study in Germany’ YouTubers would circulate through and be regularly referenced in the Facebook and WhatsApp groups, and some YouTubers ran their own such groups, in which they actively participated. There were variations between the YouTubers in terms of scale of operation: while two were more ‘hobby’ YouTubers, making videos as and when they had time, the other two devoted significant time to their channels and could be considered to have emerged as important microcelebrities and influencers within the ‘Study in Germany’ social media communities.

Unlike traditional celebrities who may have a wide global reach and remain distant from their audiences, microcelebrities are famous to only a niche group of people and their fame and popularity depend on the relationship they are able to build with their audience, and in this sense, may be seen as co-constructed with their audience (Marwick Citation2013; Senft Citation2008). Influencers have been discussed as a category of microcelebrity who ‘accumulate a relatively large following on blogs and social media through their textual and visual narration of their personal lives and lifestyles, engage with their followers in “digital” and “physical” spaces, and monetize their following by integrating “advertorials” into their blogs or social media posts’ (Abidin Citation2018, 86). There is now a large body of research that has examined various genres of influencers, from fitness influencers (Reade Citation2021) to knowledge influencers (Maddox Citation2022) to lifestyle influencers (Abidin Citation2017a). Although many of these influencers may be seen as playing an educative role by imparting information and guidance of various types to their audiences, there have been very few studies that have focused on influencers who make content related to formal education. While there has been some scholarly attention paid to how school teachers participate in the micro-celebrification process on TikTok (Vizcaíno-Verdú and Abidin Citation2023), there has been surprisingly little study of student influencers—despite the fact that, in recent years, there has been a growing number of influencers who produce content related to study and student life. This paper will begin to address this gap through an examination of microcelebrities and influencers in the space of study abroad, with particular focus on the most widely subscribed ‘Study in Germany’ YouTube channel at the time of my fieldwork, which was run by a (then) Master’s student called BharatFootnote3. At the time of writing this article, Bharat’s YouTube channel, ‘Bharat in Germany’, has over 335,000 subscribers and his videos had been watched over 26 million times. The vast majority of Bharat’s subscribers were Indian and ranged from people who had taken a decision to apply to German universities to people who were vaguely considering it.

Studies on influencers have illustrated how cultivating an image of authenticity as well as creating a sense of intimacy with one’s viewers are crucial for both achieving and monetising celebrity status (Berryman and Kavka Citation2017). In what follows, I will discuss how Bharat, drawing on the affordances of YouTube (and Facebook and WhatsApp), built connections with his viewers and established himself as a trustworthy and reliable source of information and guidance on study in Germany. As has been described in research on other influencers, videos on Bharat’s channel could be broadly divided into ‘content’ videos and ‘lifestyle’ videos (Berryman and Kavka Citation2017), or ‘anchor’ and ‘filler’ material (Abidin Citation2017b). Bharat’s ‘content’ videos or ‘anchor’ material contained information and guidance about study in Germany, and was what Bharat was primarily known for among his viewers. On the other hand, his ‘lifestyle’ videos or ‘filler’ material allowed viewers to enter his private life and get to know him better.

At the time of my fieldwork, Bharat’s ‘content’ videos fell into three broad categories: videos in which Bharat presented information and guidance to his followers, videos in which Bharat was in dialogue with another Indian student in Germany and, finally, videos in which Bharat took his viewers on virtual tours in Germany. In the first category of ‘content’ videos, Bharat would typically be seated at his desk in his home, talking to the camera in an informal manner, addressing his viewers in the way in which one would speak to a friend. It was not uncommon to see his cats or his wife walking around in the background, further conveying a feeling of being in conversation with a friend in the intimate setting of their home. Videos in this category focused on a number of topics, from the differences between the types of higher education institutions in Germany, to how to shortlist universities, to the job market for graduates in Germany.

The second type of ‘content’ videos that Bharat made featured him in conversation with one or more other Indian international students. These videos were typically on topics in which his audience had expressed interest, but on which he did not have much personal experience (for example, a study programme outside his area of specialisation). In such cases, he would invite students with first-hand experience relating to the topic of interest to join him on his channel and share their experiences with his viewers. Similarly, he made videos with Indian ‘Study-Abroad’ YouTubers in other countries like the USA, Canada, and Australia, in which they would compare what it was like to be an international student in their respective study destinations. Through his channel, then, aspirant student migrants could meet other Indians in Germany and beyond, significantly increasing the kind of social capital to which they had access. Importantly, it was not because Bharat’s social networks were so extensive that he was able to get Indians in Germany and other countries to participate in his videos. Rather, it was precisely because of the popularity of his channel, and the service it was seen to offer to other Indians, that his guests were eager to appear in his videos. The social networks that Bharat drew on were, in this sense, co-created by him and his viewers through the popularity of his channel.

The third type of ‘content’ videos Bharat made were ones through which his viewers were able to visit Germany virtually. Through the lens of the camera he took his viewers on a tour of the university at which he was studying, to supermarkets and an Indian store to show them what was available and how much things cost, to other students’ apartments to offer a sense of university-provided accommodation in Germany, and so on. As part of a series called, ‘Day in Life of a Student in Germany’, he got other Indians studying in Germany to contribute videos, filmed on their smartphones, documenting a typical day in their lives, which allowed viewers to get a glimpse of the campuses of the universities at which these students studied, the accommodation in which they lived, the part-time jobs at which they worked, and the places where they socialised.

Finally, in his ‘lifestyle’ videos, Bharat allowed viewers to enter his private life and learn more about him and his wife, Alina. Viewers were given tours of their apartment, brought into their kitchen while they were cooking dinner and taken along to birthday and family celebrations, as well as to Christmas markets and other local festivities. Viewers also learnt more about the couple’s love story and their everyday life through Q&A videos, ‘Cheesy Couple tag’ videos—typically filmed in the couple’s bedroom, living room or kitchen—and so on. Many called Bharat ‘bhai’ and Alina ‘bhabhi’ (elder brother and sister-in-law, respectively, in Hindi), and Bharat referred to his viewers as the ‘BIG [Bharat in Germany] Family’. Knowing Bharat in this way contributed to him being seen as a trusted friend and guide by his viewers—the big brother of the BIG family—and underlined his authenticity as an Indian studying in Germany, leading to people viewing his study-abroad-focused videos as offering reliable advice and information.

In making his YouTube content, Bharat was in regular dialogue with his viewers. Many of his videos were based on questions he had received from viewers via YouTube comments or the lively Facebook or WhatsApp groups he ran, and others were livestreamed, so that viewers could ask questions in real-time. In many cases, topics presented in YouTube videos were further discussed in the Facebook and WhatsApp groups. The affective relationships that Bharat and his viewers had formed via his YouTube channel were thus further developed through the community-building affordances of Facebook and WhatsApp groups (Wellman Citation2021). Like many other celebrity YouTubers, Bharat and Alina organised meet-ups with their viewers, which amplified viewers’ feelings of intimacy towards Bharat as well as reinforced imaginaries of a large BIG Family. During the time of my fieldwork, for instance, they undertook an ‘India tour’, travelling to seven different Indian cities to give seminars and hold Q&A sessions on study in Germany.

Bharat was widely credited with helping his viewers understand the German higher education landscape, inspiring and motivating them to seriously consider study in Germany (in some cases instead of another country), and demystifying and helping viewers effectively navigate the application process. He regularly received YouTube comments such as the following:

Because of you only I dreamed about Germany…will meet you there…very soon.

Bharat, your videos helps a lot for aspirants like us. I am sharing your channel to all the whatsapp groups of students i am into. Keep doing more of these. god bless.

Thanks for all your work […] you are one of the big reasons Indians move to Germany.

Like the Student Guides, Bharat criticised education consultants for being profit-driven actors who lacked lived experience of study abroad. In one video, for instance, he listed and then critiqued the five most common ‘excuses’ people made to use the services of an education consultant. The first ‘excuse’ was saying that consultants had a great deal of experience with study abroad. To this he retorted:

How do they have experience, guys? They have never been through the process themselves. Whatever knowledge they have about this whole topic about sending people to Germany or Australia or Canada or US is from what they read on Facebook posts, on the embassy websites, university websites—and that’s it. […] They don’t know how different kinds of universities are, they don’t know how it is to study in those universities.

While Bharat’s channel is not fully representative of the other ‘Study in Germany’ channels that were active at the time of my fieldwork, the other channels I studied also combined ‘content’ videos with ‘lifestyle’ videos, and critiqued education consultants in similar ways. Similar to the Student Guides, all the YouTubers I interviewed stressed their desire to help people in India take advantage of the great opportunity of higher education in Germany. Indeed, in some videos, they would speak to their audiences like motivational speakers, encouraging them to study abroad. For example, in a few of his videos, Bharat talked about unemployment and underemployment among engineering graduates in India, and encouraged his viewers to come to Germany for study. Another YouTuber, who had himself studied in a semi-rural part of the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu, told me that he had chosen to make his videos in Tamil rather than English, in order to be able to reach and inspire people in small towns and villages in his home state to consider study in Germany. In an interview with me, he discussed how, especially for people who were not from metropolitan cities, study abroad was not viewed as a feasible option:

[When I was finishing my Bachelor’s degree], I felt going abroad was something unreachable for normal people, people from normal engineering colleges. [I wanted] to show people that if [I] did [it] you, you can also do it. […] [I was able to come to Germany, and] I felt the same thing should also happen to other students who studied with me in my university. Because they were also very good in their subjects. Why they couldn’t come? It was just because they didn’t have that awareness, that exposure.

Discussion

To return to Xiang and Lindquist’s (Citation2014) concept of migration infrastructure, in this paper I have illustrated how developments in the technological infrastructure—widespread access to social media platforms among prospective international students in India, and the ways in which people are engaging with these platforms—have had tremendous impact on both the social infrastructure and commercial infrastructure mediating Indian student mobility. To begin with the social infrastructure: existing research on international student migration has rightly argued that the social networks to which a person belongs are closely linked to the economic capital they possess, and so can reproduce privilege (Beech Citation2015). Related to this, in the scholarship on higher education more broadly, it has been argued that the kind of information that a prospective student can access is patterned by social class (Brooks Citation2008). While those from more privileged backgrounds tend to rely largely on ‘hot’ sources of knowledge, i.e. informal information passed on by family members and other social contacts based on their own personal experiences, their peers from less privileged backgrounds are more reliant on ‘cold’ sources, such as league tables and university marketing materials (Brooks Citation2008). My paper, however, illustrates how ‘Study in Germany’ Facebook and WhatsApp groups and YouTube channels have allowed prospective international students in India a chance to usefully expand their social networks, not just re-establishing weak ties but also activating latent ties with both other prospective international students in India and international students in Germany, in novel ways (cf. Dekker and Engbersen Citation2014). Through these expanded networks and spaces, prospective international students could access support, guidance, ‘backstage’ information (Goffman Citation1959) and ‘hot’ sources of knowledge (Brooks Citation2008), which they would have otherwise been unable to access, and which many viewed as crucial for successfully navigating the process of going abroad to study.

Existing scholarship has illustrated how the imaginative geographies that prospective international students build of study abroad—bringing together information from people in their social networks (including on social media), from the marketing campaigns of universities and state education bodies, from their own experiences of travel abroad, and even from films and television—have significant influence over their decisions to study abroad and their study destinations (Beech Citation2014). This paper adds to this scholarship by demonstrating how for Indians seeking to study in Germany (and likely elsewhere), ‘Study Abroad’ social media communities are now key spaces in which imaginative geographies of study abroad are built collaboratively over time. Furthermore, the fact that many aspirant student migrants spend large amounts of time in these social media spaces may be seen to have normalised, to some extent, the idea of going abroad to study, as well as the idea of studying in Germany (a relatively non-traditional study destination for Indian students) and to have embedded these aspirant student migrants in cultures of mobility (Beech Citation2015). Especially for those of my interlocutors who came from small towns and villages where, they emphasized, no one was thinking or talking about going abroad, joining the ‘Study in Germany’ Facebook and WhatsApp groups and subscribing to the YouTube channels had opened up a whole new world, where they were surrounded virtually by people who were considering or attempting to go to Germany for study. In its analysis of these social media communities, my paper goes beyond existing scholarship, where—with some notable exceptions (Collins Citation2012b; Jayadeva Citation2020)—the role of social media in mediating student mobility has been discussed mainly in terms of how prospective international students are exposed to images and narratives of study abroad posted by people already within their networks, and are able to message specific individuals distantly known or unknown to them to solicit information (Beech Citation2015; Kölbel Citation2020).

The paper also examines the implications of these new intersections between the technological and social infrastructures mediating Indian student mobility, for the commercial infrastructure (Xiang and Lindquist Citation2014). In doing so, it makes two important contributions to the growing body of scholarship on education consultants. To begin with, it is the first to illuminate new spaces and forms of education consultancy and study-abroad expertise that have emerged on social media. The vibrant ‘Study in Germany’ Facebook and WhatsApp groups have created new opportunities for international students in Germany to become freelance consultants, and have strongly shaped the forms this consultancy takes. Furthermore, one can see the work that 'Study in Germany’ YouTubers do through their channels as representing a very different type of education consultancy. Through the discussion it offers on Study-Abroad YouTubers, this paper also contributes to the large scholarship on social media influencers, where surprisingly limited attention has been paid to student influencers.

The second way in which this paper contributes to the scholarship on education consultants is through an examination of how ‘traditional’ education consultants in India were viewed, and how study-abroad expertise was conceptualised, by prospective international students and internationals students from India, and with what implications. In existing scholarship, as discussed already, some studies have suggested that students view education consultants as helpful ‘bridges to learning’ (Collins Citation2012b; Thieme Citation2017), while others have drawn attention to how they may also be seen as profit-driven, manipulative, and even fraudulent actors (Marom Citation2023; Fittante Citation2023; Adhikari Citation2010). This paper adds to this literature through exploring how the widespread practice of universities partnering with education consultants to recruit international students (Beech Citation2018) can impact how consultants engage with and come to be viewed by students seeking to study in less-marketised study destinations where consultants typically do not have partnerships. Furthermore, the paper examines how a prominent critique levelled against consultants within Indian ‘Study in Germany’ social media communities—in addition to critiques of consultants being unethical profit-driven businesses—concerned an alleged lack of experiential knowledge of study abroad in general, and engineering education in Germany in particular, which was seen as calling into question their role as study-abroad experts. Indeed, in the conceptualisations of study-abroad expertise prominent within these student communities online, it is student or near-student status and a lived experience of study abroad that are associated with trustworthy and accurate study-abroad-related guidance and information.

It remains to be seen how such conceptualisations of study-abroad expertise will impact the wider landscape of ‘traditional’ education consultancy in India, if at all. During the time of my fieldwork, two trends were already visible. On the one hand, the anti-consultant narratives that circulated in these social media communities had significant material impact, with a number of my interlocutors attributing their decision not to use an education consultant to these narratives, as well as to the alternative forms of information and guidance they were able to access through these spaces. Nevertheless, there were also a number of ways in which ‘traditional’ and social-media consultancy had begun to intersect. For instance, one of the SGs I interviewed had a partnership with an education consultant in India, who—in exchange for a commission—referred him clients who were interested in studying in Germany. Another SG I interviewed had set up a brick-and-mortar education consultancy in India in collaboration with other SGs he had met in the social media groups.

While this paper has focused particularly on Indian student mobility to Germany, ‘Study Abroad’ YouTubers and mutual-support social media groups—and possibly even Student Guides—exist for many other study destinations, and have a major impact on how study abroad is imagined and how mobilities are crafted. Understanding student migration from India, and likely other destinations in the Global South, thus requires attention to new intersections between the technological, social, and commercial infrastructures mediating this mobility.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) and the GIGA Institute for Asian Studies for funding the research project on which this paper draws. I carried out fieldwork for this project while based at the GIGA Institute for Asian Studies, where I continue to be affiliated as an Associate Researcher. I am very grateful to my colleagues there, especially Prof. Patrick Köllner, for their encouragement and support of this research. I would also like to thank the Department of Sociology at the University of Cambridge for being such an excellent academic home. In addition, I am thankful to the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments that strengthened this paper and to Stephan Hilpert for many useful discussions about this research. Finally, I am indebted to all those who participated in this research project—many of whom I now count as friends.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2024.2329413)

Notes

1 As my interlocutors typically used the term ‘education consultant’, I will use this term throughout the paper.

2 All names are pseudonyms (unless otherwise specified) and some details of my interlocutors’ stories have been changed to ensure their anonymity.

3 This is his real name as he did not wish to be anonymous.

References

- Abidin, C. 2017a. “Influencer Extravaganza: Commercial ‘Lifestyle’ Microcelebrities in Singapore.” In The Routledge Companion to Digital Ethnography, 184–194. New York: Routledge.

- Abidin, C. 2017b. “# familygoals: Family Influencers, Calibrated Amateurism, and Justifying Young Digital Labor.” Social Media + Society 3 (2):2056305117707191.

- Abidin, C. 2018. Internet Celebrity: Understanding Fame Online. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.

- Adhikari, R. 2010. The “Dream-Trap”: Brokering, “Study Abroad” and Nurse Migration from Nepal to the UK.” European Bulletin of Himalayan Research 35: 122–138.

- Beech, S. E. 2014. Why Place Matters: Imaginative Geography and International Student Mobility.” Area 46 (2): 170–177. doi:10.1111/area.12096.

- Beech, S. E. 2015. International Student Mobility: The Role of Social Networks.” Social & Cultural Geography 16 (3): 332–350. doi:10.1080/14649365.2014.983961.

- Beech, S. E. 2018. Adapting to Change in the Higher Education System: International Student Mobility as a Migration Industry.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (4): 610–625. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1315515.

- Berryman, R., and M. Kavka. 2017. “I Guess a Lot of People See Me as a Big Sister or a Friend’: The Role of Intimacy in the Celebrification of Beauty Vloggers.” Journal of Gender Studies 26 (3): 307–320. doi:10.1080/09589236.2017.1288611.

- Brooks, R. 2008. “Accessing Higher Education: The Influence of Cultural and Social Capital on University Choice.” Sociology Compass 2 (4): 1355–1371. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9020.2008.00134.x.

- Brooks, R., and J. Waters. 2010. “Social Networks And Educational Mobility: The Experiences of UK Students.” Globalisation, Societies and Education 8 (1): 143–157. doi:10.1080/14767720903574132.

- Brooks, R., and J. Waters. 2011. Student Mobilities, Migration and the Internationalization of Higher Education. New York: Springer.

- Collins, F. 2012a. “Cyber-Spatial Mediations and Educational Mobilities: International Students and the Internet.” In Changing Spaces of Education, 258–274. London and New York: Routledge.

- Collins, F. L. 2008. Bridges to Learning: International Student Mobilities, Education Agencies and Inter‐Personal Networks.” Global Networks 8 (4): 398–417. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0374.2008.00231.x.

- Collins, F. L. 2012b. Organizing Student Mobility: Education Agents and Student Migration to New Zealand.” Pacific Affairs 85 (1): 137–160. doi:10.5509/2012851137.

- DAAD 2021. “Germany Welcomes Record Number of Indian Students.” https://www.daad.in/en/2020/10/13/germany-welcomes-record-number-of-indian-students/

- DAAD 2022. “German HEIs More Internationally Popular Than Ever.” https://www.daad.de/en/the-daad/communication-publications/press/press_releases/wissenschaft-weltoffen-2022/

- Dekker, R., and G. Engbersen. 2014. “How Social Media Transform Migrant Networks and Facilitate Migration.” Global Networks 14 (4): 401–418. doi:10.1111/glob.12040.

- Fittante, D. 2023. “Beyond Brokering for Recruitment: Education Agents in Armenia.” Population, Space and Place 29 (1): e2622. doi:10.1002/psp.2622.

- Goffman, E. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Doubleday Anchor.

- Granovetter, M. S. 1973. “The Strength of Weak Ties.” American Journal of Sociology 78 (6): 1360–1380. doi:10.1086/225469.

- Haythornthwaite, C. 2005. “Social Networks and Internet Connectivity Effects.” Information, Community & Society 8 (2): 125–147.

- Hendry, N. A., C. Hartung, and R. Welch. 2022. “Health Education, Social Media, and Tensions of Authenticity in the ‘Influencer Pedagogy’ of Health Influencer Ashy Bines.” Learning, Media and Technology 47 (4): 427–439. doi:10.1080/17439884.2021.2006691.

- Jayadeva, S. 2020. “Keep Calm and Apply to Germany: How Online Communities Mediate Transnational Student Mobility from India to Germany.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (11): 2240–2257. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1643230.

- Jayadeva, S., and S. Thieme. 2022. “Building Bridges.” Universities as Transformative Social Spaces: Mobilities and Mobilizations from South Asian Perspectives, 137. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kölbel, A. 2020. “Imaginative Geographies of International Student Mobility.” Social & Cultural Geography 21 (1): 86–104. doi:10.1080/14649365.2018.1460861.

- Lave, J., and E. Wenger. 2004. Communities of Practice. Learning, Meaning and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Maddox, J. 2022. “Micro-Celebrities of Information: Mapping Calibrated Expertise and Knowledge Influencers Among Social Media Veterinarians.” Information, Communication & Society : 1–27. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2022.2109980.

- Manderscheid, K. 2014. “Criticising the Solitary Mobile Subject: Researching Relational Mobilities and Reflecting on Mobile Methods.” Mobilities 9 (2): 188–219. doi:10.1080/17450101.2013.830406.

- Marom, L. 2023. “Market Mechanisms’ Distortions of Higher Education: Punjabi International Students in Canada.” Higher Education 85 (1): 123–140. doi:10.1007/s10734-022-00825-9.

- Marwick, A. E. 2013. Status Update: Celebrity, Publicity, and Branding in the Social Media Age. Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Reade, J. 2021. “Keeping it Raw on the ‘Gram: Authenticity, Relatability and Digital Intimacy in Fitness Cultures on Instagram.” New Media & Society 23 (3): 535–553. doi:10.1177/1461444819891699.

- Said, E. W. 1985. Orientalism. London: Penguin Books.

- Senft, T. M. 2008. Camgirls: Celebrity and Community in the Age of Social Networks (Vol. 4). New York: Peter Lang.

- Thieme, S. 2017. “Educational Consultants in Nepal: Professionalization of Services for Students Who Want to Study Abroad.” Mobilities 12 (2): 243–258. doi:10.1080/17450101.2017.1292780.

- Tuxen, N., and S. Robertson. 2019. “Brokering International Education and (Re) producing Class in Mumbai.” International Migration 57 (3): 280–294. doi:10.1111/imig.12516.

- Vizcaíno-Verdú, A., and C. Abidin. 2023. “TeachTok: Teachers of TikTok, Micro-Celebrification, and Fun Learning Communities.” Teaching and Teacher Education 123: 103978. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2022.103978.

- Wellman, M. L. 2021. “Trans-mediated Parasocial Relationships: Private Facebook Groups Foster Influencer–Follower Connection.” New Media & Society 23 (12): 3557–3573. doi:10.1177/1461444820958719.

- Wenger, Etienne. 2004. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Xiang, B., and J. Lindquist. 2014. “Migration infrastructure.” International Migration Review 48 (1_suppl): 122–148. doi:10.1111/imre.12141.