ABSTRACT

Violent extremism is a destabilizing force; its underlying confounding influence should be accounted for to understand this phenomenon. Previous studies have identified its potential risk factors or drivers. This study of Sharia-invoking Salafi extremism addresses whether these factors or drivers are affected by the confounding influence of the radicalization ecosystem. Starting secularly, the newly-formed Eastern European nation of Kosovo became radicalized. Using the 2013 data obtained from Pew Research Center, this study computes measures of confounding influence by using public support levels for radical Islamist agendas before and after radicalization in Kosovo. Utilizing these data and those relating to the worldwide number of jihadist fighters in different periods, this study asserts that the ecosystem acts as a confounder of the risk factors and drivers of violent extremism, thus creating spurious correlations between the two. This study invokes a published theoretical framework for understanding the radicalization ecosystem behind the confounding vis-à-vis Salafi extremism. Contrary to conventional wisdom, the present study finds that mitigating the influence of the ecosystem offers the most comprehensive way of reducing violent extremism. Such a conclusion has implications for the direction of terrorism research.

© 2024 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group

Introduction

Twenty-two years have passed since the 9/11 attacks in 2001; however, Islamist extremism still remains misunderstood or ununderstood. Walter (Citation2017) noted that “This growth [of Salafi jihadist groups] suggests an underlying level of support from Muslim communities worldwide that we do not yet understand” (p. 39).

The Indian government is grappling with the challenge of the growing radicalization of its minority – a growth that has given rise to Islamist extremist outfits, such as the Popular Front of India (BBC, Citation2022). Recently, Israel has found itself embroiled in a major conflict with the Islamist group, Hamas (Knell, Citation2023). One could argue that the recent fall of Afghanistan to the Taliban is mainly due to the lack of a theory on how the Taliban and its allies radicalized the populace and convinced them of their ideology (Hamid, Citation2021). Owing to its overwhelming military power, the United States and its allies could destroy the Islamic State’s caliphate in Syria and Iraq (Gordon, Citation2022). However, the social dynamic that enabled the rise of the Taliban and Salafi jihadists is still prevalentFootnote1 worldwide (Hamid, Citation2021; Perez, Citation2023).

The 2018 National Strategy for Counterterrorism (NSCT) is the most recent presidential policy framework for tackling Islamist extremism. It uses the word “ideology” nine times, but only to assert that to “defeat radical Islamist terrorism, we must also speak out forcefully against a hateful ideology that provides the breeding ground for violence and terrorism” (NSCT, Citation2018: p. 2). The strategy does not identify the circumstances and entities behind the ideology when calling for an addressing of radicalized communities’ “grievances” (p. 22). Hence, this policy reflects the lack of a scholarly consensus on the root cause.

This study posits that we must first understand how a community radicalizes to address violent extremism. Radicalism could be associated with political thinking outside the mainstream; however, acts of (violent) extremism, such as terrorism, are defined in this study as the distinct willingness to use violence against civilians. Berger (Citation2018: p. 24) associated extremists with the mindset of “us versus them,” intensified by the conviction that the success of “us” is inseparable from hostile acts against “them.”

The ecology of social systems studies how individuals interact with and respond to the environment and how these interactions affect society and the environment (Berkes & Folke, Citation1998). In this context, the idea of a “radicalization ecosystem” should be introduced. Baele et al. (Citation2020) coined the term “ecosystem” to describe virtual networks of far-right activity. The extensive use of the words “radicalization ecosystem” here follows these lines.

Background of Salafi extremism

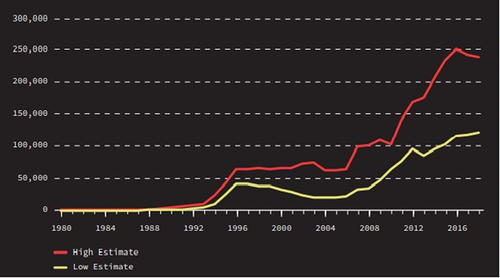

Salafi extremism is embraced by the Islamic State, al-Qaeda, and Boko Haram (Jones et al., Citation2018; Maher, Citation2016; Meijer, Citation2010). The emergence of this form of global extremism suggests its association with a well-defined radicalization ecosystem. Salafism is a religious practice that strives to return to Islam’s earliest roots; salaf is Arabic for “ancient one” (Livesey, Citation2005). According to Haykel (Citation2012: pp. 483–484), Salafism is similar to Wahhabism, and only the minority has embraced Salafi extremism, such as Salafi jihadism, with the Salafi majority consisting of those working within the system to advance political agendas or those who shun all forms of overt political action. While there are variations in Salafi practices, Walter (Citation2017) identified the ideology of Salafi extremists with armed jihad (religious war), the rejection of democracy, and the embracing of a very narrow and conservative version of Sharia. The global Salafi jihadist movement began to develop in the 1990s and is rooted in the Sunni branch of Islam (Kepel, Citation2004; Livesey, Citation2005). provides estimates of Salafi jihadist fighters worldwide (Jones et al., Citation2018).

Figure 1. Estimated number of active Salafi jihadist fighters, 1980–2018.

Starting in the 1970s, Saudi Arabia’s spread of Wahhabism is largely believed to have led to the worldwide movement of Salafism (Haykel, Citation2012: p. 484; Mandaville & Hamid, Citation2018). The 1 March 2002 edition of the Saudi government’s English weekly, Ain al-Yaqeen, detailed Wahhabism’s propagation (MEMRI, Citation2002). In the 1980s, the country’s embassies worldwide were tasked with propagating Wahhabism by building new mosques or persuading the existing ones to embrace the movement (Lacey, Citation2009: p. 95). Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries “effectively paid for the rise of the pan-Islamist movement by funding international Islamic organizations” (Hegghammer, Citation2020: p. 195).

A prominent Saudi Arabian charity involved in spreading Wahhabism worldwide is the Muslim World League (MWL). The Saudi government has funded the MWL since its inception in the 1960s (Ende & Steinbach, Citation2011). In April 1980, the MWL’s general secretary, Muhammad Ali Harakan, declared that “jihad is key to Muslims’ success and felicity,” which received significant coverage well beyond Saudi Arabia (Harakan, Citation1980 pp. 48−49; Hegghammer, Citation2010: p. 83). The MWL website profile called on “individuals, communities, and state entities to abide by the rules of the Sharia” (Muthuswamy, Citation2016: p. 5; MWL, Citation2014).

Sharia is the law of the land in Saudi Arabia (Eijk, Citation2010: p. 157), and forms the basis of Wahhabi ideology. Saudi Arabia has started diluting Wahhabi practices by codifying some laws as distinct from (oral) Sharia laws (Rashad, Citation2021). Regardless of whether the kingdom has reduced funding for the propagation of Wahhabism abroad, the ideological ecosystem built by the propagation of Wahhabism appears to be self-sustaining (Varagur, Citation2017).

Sharia is the religious leaders’ interpretation of Islam (Doi & Clarke, Citation2008); therefore, promoting it is in their interest. Unlike in Saudi Arabia, where Sharia was all-encompassing and strict, in approximately half the Muslim-majority nations, Sharia law is applied mainly in the domestic sphere to settle family or property disputes (Robinson, Citation2021). The idea propagated from Islam’s birthplace (Saudi Arabia), suggesting that Sharia is a divine guide to life can be an appealing theme for pious Muslims. Such a theme empowers religious leaders and provides them with a platform to advance their agendas of interest, including radical ones. However, Sharia’s followers overlook the fact that the Sharia interpretations are often contradictory (Macfarquhar, Citation2009; Muhammad, Citation2012).

The emerging worldwide influence of Wahhabism is also termed “Arabization” – often characterized by women wearing a veil and men growing facial hair (Ghoshal, Citation2010; Varagur, Citation2020). Several polls show evidence of Wahhabi influence and growing support for Sharia. In a World Public Opinion global survey conducted in Morocco, Egypt, Pakistan, and Indonesia, a substantial majority supported the requirement of a “strict application of Sharia law in every Islamic country”; the survey indicated the desire for a “caliphate” – a unified Islamic state governed by Sharia (Kull et al., Citation2007). Moreover, those polled in Morocco (66%), Egypt (75%), Pakistan (81%), and Indonesia (54%) considered Sharia to be the revealed “Word of God” (Pew Research Center [PRC], Citation2013: p. 42). The recent influence of Wahhabism can also be ascertained based on age-specific correlations of measures of radicalism (Muthuswamy, Citation2018: p. 58). In this case, in Britain, the support for Sharia law (37%), killing apostates (36%), and the admiration of al-Qaeda (13%) among Muslims between the impressionable ages of 16 and 24 can be compared with 17%, 19%, and 3%, respectively, for those aged 55 and over (PE, Citation2007: pp. 46–47, p. 62).

The call to embrace Sharia has come from a broad spectrum of religious leaders. For example, a declaration made at a conference in India attended by an estimated 10,000 Islamic clerics, scholars, muftis, and teachers of madrasas in India called on Muslims to spend their lives following the “Islamic Shariah and teachings with full confidence” (MEMRI, Citation2008). A significant inflow of Sharia-promoting Wahhabi scholars from abroad has been documented in India (Nanjappa, Citation2014).

Religious leaders espouse armed jihad and have done so in many religious schools and mosques run by them (Al-Saleh, Citation2015; Gall, Citation2016). Those who espouse this radical agenda play a prominent role in online radicalization (Carter et al., Citation2014). Moreover, after analyzing the writings of religious leaders on the Internet, Nielsen (Citation2017: p. 121) estimated that approximately 10% of the leaders espouse this form of jihad. According to a 2015 Kosovo government report, religious leaders played a role in “encouraging” or “recruiting” for the Islamic State and “contributed to the development of a religious extremist ideology” (RK, Citation2015: p. 14).

The act of enabling Sharia and radical agendas is to lead jihadist groups. Following this, the religious leaders Abdullah Azzam (Aboul‐Enein, Citation2008), Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi (BBC, Citation2015), and Mohammed Yusuf (Felter, Citation2018) founded and/or led the jihadist groups al-Qaeda, Islamic State, and Boko Haram, respectively.

Kosovo’s radicalization

Until 1999, the social and political identity of the Muslim-majority Kosovo Albanians was secular and exhibited multi-religious cohabitation.

During the communist period, religious communities were under state control, and their impact on society was quite limited. With the beginning of the transition and efforts for freedom of Kosovo, the political pluralism among ethnic Albanians was developed based on strong ethnic secularism with multi-religious cohabitation, which coincided with modern European values and aspirations. (Kosovar Institute for Policy Research and Development (KIPRED, Citation2016: p. 8).

The community was also not radicalized if this evidence is any indication: when approximately 4,000 jihadists from Peshawar, Pakistan went to fight on behalf of the Kosovars in the early 1990s, “the term [jihad] struck no chord in the local Muslim population” (Kepel, Citation2002: p. 239). However, the secular fabric began to fade with the intrusion of religion-based organizations from the Middle East (KIPRED, Citation2016: p. 8). Later, the Kosovar community underwent radicalization.

By the mid-2000s, Saudi money and Saudi-trained clerics were already exerting influence over the Islamic Community of Kosovo. From their bases, the Saudi-trained imams propagated Wahhabism’s tenets; the supremacy of Sharia law as well as ideas of violent jihad and takfirism, which authorizes the killing of Muslims considered heretics for not following their interpretation of Islam (Gall, Citation2016).

A study by a think tank recognizes “the strong impact of Saudi Arabia in introducing more conservative religious ideas and practices” in Kosovo, as well as the fact that, among the nations that sent fighters to the Islamic State, Kosovo had the “highest number of foreign fighters per capita of their respective Muslim populations” (Kosovar Centre for Security Studies [KCSS], Citation2015: p. 7). Shtuni (Citation2016) observed that “Kosovo, a country with no prior history of religious militancy, has become a prime source of foreign fighters in the Iraqi and Syrian conflict theatre relative to population size” (p. 1). Thus, the post-1999 Kosovo community, unlike the pre-1999 community, could be associated with religion-invoking violent extremism. While these studies noted the role of religious entities in radicalization, they also blamed social inequalities as drivers of radicalization in Kosovo (KCSS, Citation2015; RK, Citation2015; Shtuni, Citation2016). Moreover, they did not investigate whether these entities could act as confounders.

Literature review

Confounding is a bias due to a common cause of exposure and outcome that occurs temporally first (Ananth & Schisterman, Citation2017). The confounding influence may mask an actual association or falsely demonstrate an apparent association between the exposure and outcome when no real association exists. In this context, control consists of a population that does not receive exposure.

The common theme among published scholarships (both old and new) is the inability to prove causation due to a lack of control data that can discount confounding. Moreover, these scholarships typically lack a theory describing the phenomenon’s causal mechanism. First, we discuss reviews that outline the state of play vis-à-vis published scholarships and then discuss the shortcomings of more recent scholarships.

Researchers have developed various models to explain violent extremism. In a review of the five models of violent extremism, King and Taylor (Citation2011) found them to “diverge significantly from one another” (p. 612). They concluded that three factors – relative deprivation, identity conflict, and personality characteristics – are central to the phenomenon. However, these three factors were primarily based on correlational studies, and their causal roles remain unproven.

According to Desmarais et al. (Citation2017), partly due to “the predominance of descriptive statistics and correlational designs” (p. 196) in the extant literature, causal factors of terrorism could not be identified. A later review of the prominent models of political violence noted the consistency of correlations outlined in different models but admitted that the empirical evidence could not “distinguish between indicators and true causal factors of radicalization unto political violence” (Gøtzsche-Astrup, Citation2018: p. 9).

A review of the literature on preventing violent extremism lists the following concepts as being pertinent: 1) the “resilient individual,” (2) identity, (3) dialogue and action, and (4) connected or resilient communities (Stephens et al., Citation2021). Resilient individuals are those with the capacity to avoid being drawn into violent extremism. By preventing the marginalization of one’s group identity, one may avoid extremism. Enabling dialogue creates space for critiquing ideologies, while action keeps young people engaged in volunteer social projects. Finally, community engagement involves strengthening the relationship between community organizations and the government; a resilient community can come together to prevent its members from being drawn into extremism. However, this review overlooked the possibility that these concepts could be dependent variables of a confounder and, thus, be spurious.

Recently, scholars have distinguished sympathy (attitude) towards violence from involvement in such behaviour, which some older models overlooked. This distinction is incorporated into the Attitudes-Behaviors Corrective (ABC) model of violent extremism (Khalil et al., Citation2022). The authors associated the following candidate drivers as “independent variables”: poverty, ineffective governance, state violence, fear, excitement, and vengeance (p. 443). They claimed that their model “avoids the concept of radicalization” (p. 426) in studying violent extremism. Although the authors cautioned about overlooking the confounding influence (through the omitted variables), they did not mention that the candidate drivers should not be deemed independent variables without determining the confounding effect. Instead, they suggested that these unproven candidate drivers be taken seriously in policy formulation (p. 444).

Clemmow et al. (Citation2023) associated individual susceptibility to moral change (pre-existing propensity), selection factors (situation), and violent radicalization settings (exposure) with risk factors for engaging in violence through what authors call the Risk Analysis Framework (RAF); the work claimed that disrupting or preventing the emergence of radicalizing settings may be the most effective at reducing the risk of violence (p. 22). However, they did not recognize the source of these settings and that this source could have a confounding influence on all risk factors. They also emphasized the importance of this sum total of over one hundred risk factors (p. 3), even though they admitted that they could not associate cause-and-effect inferences with the risk factors (p. 22).

Clemmow et al. (Citation2023) and Khalil et al. (Citation2022) did not recognize the influence of confounding due to a lack of control data needed to eliminate spurious correlations. Moreover, lacking causal mechanisms associated with theories, these studies did not know how the potential independent variables directly affected the dependent variable (measures of violence). Therefore, a priori, it is impossible to know whether these risk factors or drivers are causative or dependent variables of a confounding influence. Moreover, neither study provided data to support the premise that suppressing the impact of these drivers or risk factors would necessarily lead to reduced violence.

Concerning Salafi or Islamist extremism, only the following studies linked the two intrinsic attributes of Islam – Sharia and armed jihad – with Islamist militancy. In Pakistan, those who supported the Sharia-motivated (hudud) corporal punishment of cutting off thieves’ hands were more supportive of Islamist militancy (Fair et al., Citation2018: p. 443). Moreover, those who viewed jihad as the duty to wage an external armed struggle against the enemies of Islam were more likely to support terrorism than those who viewed jihad as a personal struggle to lead a righteous life (Fair et al., Citation2012). Haddad (Citation2004) found that supporters of armed jihad were more supportive of the violent extremist groups in Lebanon and Palestine. However, these three studies have the following theoretical shortcomings: The independent variables in the above studies are not human-based entities but attributes of religion. In reality, they are likely to be dependent variables of the entities mentioned above. Besides, the studies lacked controls that were not exposed to the radicalization ecosystem. Hence, this construct cannot explain (through a causal mechanism) how human-based entities impacted these variables – how the ecosystem came into being. Moreover, the Sharia-related study was specific to Pakistan, while the jihad-related studies were specific to Pakistan, Lebanon, and Palestine.

In this context, the sole exception in the published literature is the theory of Salafi extremism proposed by Muthuswamy (Citation2022), whose methodology is partially used in the present study, and this scholarship is discussed in detail in the following section. However, this study did not quantify the radicalization ecosystem’s confounding influence or elaborate on how the ecosystem affected the aforementioned drivers and risk factors. Although it invoked Kosovo as a control, the study did not rigorously verify the external validity of the proposed causal mechanism or estimate the extent of further confounding on the identified radicalization ecosystem. The following section outlines an analytical framework for overcoming the shortcomings and gaps noted in this literature review.

Analytical framework

Knowing the impact of confounding can lead to identifying spurious correlations generated by multiple drivers and help reveal the independent variable behind causation. The first hint of trouble with conventional wisdom comes in the reality that hardly any drivers or risk factors noted in the literature have led to violent extremism in mainstream communities where they are likely to be present. Nevertheless, they seem to induce violence (according to the observed correlations) in a community that is already radicalized (Clemmow et al., Citation2023; Khalil et al., Citation2022). However, it is conceivable that these drivers or risk factors do not favour violent extremism in communities that do not significantly subscribe to radical agendas.

The issue of whether the identified drivers or risk factors are indeed independent variables can be explored by studying Salafi (Islamist) extremism in Kosovo. There are two reasons why the data from Kosovo discussed in the Introduction are unique from the viewpoint of asserting the influence of confounding; first, as discussed before, formerly secular Kosovo underwent radicalization recently; and second, we listed data from Kosovo regarding the scenarios of both before and after radicalization, with the former providing the control data. Besides, the data from Kosovo (PRC, Citation2013) can be used to estimate a measure of the confounding influence associated with the radicalization ecosystem.

By definition, cause and effect are connected through a causal mechanism. In the conventional approach discussed in Clemmow et al. (Citation2023) and Khalil et al. (Citation2022), scholars aim to correlate drivers or risk factors with measures of violent extremism, through which they hope to identify the underlying causal mechanisms. Mearsheimer and Walt (Citation2013) discounted this “simplistic hypothesis testing” (p. 247) conceptual approach because, without knowing the underlying causal mechanism, there is no way of knowing, a priori, which among the drivers or risk factors is the independent variable or whether the said variable is sampled; instead, they suggested the following approach: “In particular, we need theories to identify the causal mechanisms that explain recurring behavior and how they relate to each other. Furthermore, theories are essential for defining key concepts, operationalizing them, and constructing suitable data sets” (p. 430, p. 437). However, the authors did not offer any insights into how one might propose such a theory.

In an effort towards framing a theory, the present study does not use a measure of violent extremism as a dependent variable, arguably because the extent of public support for radical agendas forms a measure of the radicalization ecosystem. Furthermore, as the data in suggest, the ecosystem must form before jihadist groups can take root in a community. In this context, radicalization can be understood as the public’s embrace of radical agendas propagated by human-based enablers in the theme-enabler framework introduced by Muthuswamy (Citation2018, Citation2022). Although this framework is simple, it can define a causal mechanism, with the enablers acting as independent variable and radical agendas as dependent variables, linked through the theme. First, enablers must have a self-interest in propagating such agendas and some standing in the community to be effective. Second, the enablers may propagate an appealing “theme” (Muthuswamy, Citation2022: p. 6) and use it as a platform to enhance their standing and that of the agendas they espouse. A theme can act as a mediator and moderator and lies in the causal pathway (Muthuswamy, Citation2022). This behavioural process can create a social movement. This framework is helpful because one can design surveys based on it to test a hypothesis associated with the causal mechanism; it also explains how powerful social movements may be generated outside state control, such as the Salafi extremism movement.

The shortcomings and gaps outlined in the Literature review were circumvented by invoking the theme-enabler methodology for a study of 20 nations, that included Kosovo (Muthuswamy, Citation2022). This method was utilized to identify the causal mechanism behind Salafi extremism, with the understanding that the underlying theory must incorporate Saudi Arabia, religious leaders, radical agendas, and Sharia. Accordingly, Muthuswamy (Citation2022) proposed and substantiated the following theory using the theme-enablers framework vis-à-vis Salafi (violent) extremism: “Backed by the prestige and resources of Saudi Arabia, religious leaders have popularized the appealing theme of Sharia as all-encompassing ‘divine law’ to advance radical agendas that act as precursors to extremism” (p. 7). The radicalization process may then be defined in the context of this theory as the propagation of radical agendas.

As seen in this specific scenario, a “theme” is an appealing construct for a large cross-section of a community. In contrast, radical agendas (by definition, off-mainstream) are unlikely to find supporters without the platform the theme provides. Arguably, themes form the basis of the ideological ecosystems of emerging social movements.

The present study

As discussed before, scholars did not prove that the above risk factors, drivers, or concepts can cause violent extremism or prevent such extremism. Using detailed data on Salafi extremism from Kosovo (PRC, Citation2013), this study tests the following hypothesis: The confounding influence on the measures of radicalization ecosystem catalyzed by Wahhabism’s worldwide propagation is significant. The Results section computes the confounding measures to test the hypothesis. In the Discussion section, we argue that the identified risk factors and drivers in the literature are dependent variables of the confounding radicalization ecosystem. Furthermore, we invoke a published theory to explain that this emergent radicalization ecosystem consists of only one independent variable and another that sits on the causal pathway associated with the theory. We also argue that any further confounding influence on this ecosystem must be minimal.

Material and methods

Research design for ascertaining the confounding influence

Following Breslow and Day (Citation1980), a confounding measure (CM) of the radicalization ecosystem can be obtained using the formula: CM = 100 (P – R)/R, where P is the value of a variable (at the public support level) affected by the radicalization ecosystem, and R is the value of the same variable before radicalization. When computed, the CM then estimates the extent of confounding induced by the ecosystem.

The variables of interest include the public’s support for the radical agenda of cutting off thieves’ hands, the death penalty for apostates, and stoning of people who commit adultery (which reflect the physiological mindset of fundamentalism or serve as radicalization measures or agendas prescribed under Sharia by religious leaders; for details, see Peters (Citation2006)). The public support for Sharia as the law of the land measures the radicalization ecosystem’s strength. Since P reflects the strength of the radicalization ecosystem, the public support level for those who support the radical agenda and also favour Sharia as the law of the land is used as its measure. As data on the support levels for the radical agenda before the onset of radicalization are lacking, the post-radicalization support level for the radical agenda R among those who did not favour Sharia is used as an upper estimate, resulting in lower computed CMs.

For computing R, this formula was employed: R = 1.25 (Q–0.2*P).Footnote2 Here, Q represents the support level for the radical agenda of interest. Additionally, 20% (variable S) of those polled in Kosovo favoured the Sharia measure (). Q, S, and R values were relatively small for Kosovo () – a representation that a large majority still exhibited characteristics of Kosovo’s pre-radicalized secular recent past (KIPRED, Citation2016). The values for the P and Q were taken from PRC (Citation2013: pp. 52–55, pp. 219–221). The details associated with the PRC surveys are outlined below.

Table 1. Public support levels for Sharia correlated with jihadist activity.

Research design for understanding radicalization

A theoretical framework must involve a causal mechanism that links the dependent and independent variables. A covariation analysis involving hypothesis testing is used to validate the causal mechanism associated with the theory of Salafi extremism. Religious leaders are considered as the enablers (independent variable (A)),Footnote3 and radical agenda is the dependent variable (B), with Sharia as the theme (C). For an independent variable A that affects a dependent variable B, causality involves establishing the following conditions (King et al., Citation1994; Muthuswamy, Citation2022): (1) determining whether A is causing B and not the other way around; (2) determining whether A and B correlate; (3) determining whether a variable C can act as a “mediator” between A and B (Baron & Kenny, Citation1986); and (4) showing that any omitted or confounding variables could make only minor contributions to the observed correlations (Hill, Citation1965). A mediator’s influence over time can evolve to become a “moderating” one (Karazsia & Berlin, Citation2018), with the moderator (Dawson, Citation2014) dictating the strength of the relationship between A and B.

Application toward understanding Salafi radicalization

The above theory was tested using the data presented in (Muthuswamy, Citation2022). Most entries in the table are taken from PRC (Citation2013) and Muthuswamy (Citation2022). This includes public support levels for religious leaders as religious judges, their espousing of the Sharia-prescribed corporal punishment of cutting off thieves’ hands as the radical agenda, and Sharia as the law of the land. PRC (Citation2013) conducted public opinion surveys between 2008 and 2012 in 39 African, Asian, and European countries and territories. Other than China, India, Saudi Arabia, and Syria, the surveys mentioned above covered every country with a population of at least 10 million Muslims. In Afghanistan, the respondents were disproportionately men, while in Azerbaijan, they were disproportionately women. PRC (Citation2013) listed only 20 countries with data on the role of religious leaders in politics; accordingly, the entire dataset in is restricted to 20 nations. There is a margin of error of about 5% when collecting data from some (rather than all) of the Muslim population at the 95% confidence interval (CI) (PRC, Citation2013).

The impact of subtle variations in the local propagation of Wahhabism or the meaning of Sharia were built into PRC data gathered worldwide. The data represent communities spanning economic, political, linguistic, and cultural fault lines, thus reducing selection bias. A Microsoft Excel linear regression analysis invoked this data from 20 nations (Muthuswamy, Citation2022). Although the data presented in is cross-sectional, it constitutes different time scales vis-à-vis local initiations of the underlying Wahhabi influence. For example, as noted in the Introduction, Eastern European nations with a solid secular history, such as Kosovo, were exposed to the Wahhabi influence much later than the nations with higher support levels for Sharia, such as Pakistan. The data in Columns 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 8 of were taken from the PRC survey (Citation2013). The entries in Columns 6 and 9 were computed based on the previous two column entries for the corresponding nations (please see Note 2 for details). The data on home-grown jihadist groups (Column 10 of )Footnote4 were taken from Muthuswamy (Citation2016).

Results

The lowest limit of the CMs due to sampling errors is of interest. Kosovo’s total sample size was 1,266 (PRC, Citation2013: p. 150), with an associated sampling error of 5.3% at the 95% CI. However, for variable R, the sample size reduces by the factor 0.8 (1–0.2, see above) because it corresponds to the population proportion that did not favour Sharia. For variable P, the sample size reduces from 1,266 by a factor of 0.2. Following Lane (Citation2023), the sampling error for R is 5.3%/sqrt(0.8) = 5.92%, and for P is 5.3%/sqrt(0.2) = 11.85%. Hence, the lowest CM limit (at the 95% CI) = 100((P − 11.85)–(R + 5.92))/(R + 5.92).

The computed CMs and associated lowest limits for Kosovo are listed in . Although the CMs are significant for all three radical agendas, at the lowest end of the 95% CI, the radical agenda of assigning the death penalty to the apostates has a zero CM. Since the average estimates of CMs are higher than 10% (usually the rule of thumb used for identifying the significance of a confounding influence; Budtz-Jørgensen et al., Citation2007) for all of these radical agendas, one can conclude that confounding influence on the measures of radicalization is significant for Kosovo.

Table 2. Confounding measures for different radical agendas in Kosovo.

The results of linear regression analyses of the combined survey data in (entries in Columns 2, 4, and 7)) for all twenty nations are summarized in ; they statistically satisfy the covariation requirements; p-value <0.05, indicating that the observed effects are less due to chance (see Muthuswamy, Citation2022). The computed coefficients of determination (R2) signify the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that the independent variable can explain in a regression model. The linear regression analysis of the data in reveals high values of R2 between religious leaders and the radical agenda (83%), Sharia and the radical agenda (86%), and religious leaders and Sharia (85%) (; Muthuswamy, Citation2022).

Table 3. Summary of linear regression analysis parameters for the combined data in Table 1.

Discussion

Nearly all empirically-supported drivers, risk factors, or concepts (noted in the Introduction) were likely present in pre- and post-1999 Kosovo. However, no violent extremism was invoked through jihad in pre-1999 Kosovo, unlike during the post-1999 Kosovo period. Salafi jihadist groups and their associated fighters barely existed prior to 1980 worldwide (i.e., before Wahhabism’s propagation took off); however, by 2018 there were at most 67 groups and approximately 180,000 fighters (; Jones et al., Citation2018). Therefore, one can conclude that the aforementioned risk factors or candidate drivers – such as poverty, ineffective governance, and vengeance (Clemmow et al., Citation2023; Khalil et al., Citation2022) – most of which are omnipresent, would not cause violent extremism such as Salafi jihadism unless a community were to first radicalize. Hence, these empirical factors or drivers are not causes or independent variables but dependent variables influenced by the radicalization ecosystem, and the correlations involving these dependent variables are spurious.

Kosovo’s transformation indicates that the onset of radicalization is a precursor for the involvement of the individuals belonging to the community to engage in violent extremism, such as armed jihad. The resulting radicalization ecosystem can dictate the community’s behaviour vis-à-vis acts of violence. Researchers have found that an individual who joins a jihadist group does not have to be radicalized per se (Gates & Podder, Citation2015) but has to have connections to a community that has been radicalized. clarifies this point, where a measure of violent extremism (Column 10) correlates with public support levels for a radical agenda across 20 nations (Column 7).

The consensus view of violent extremism overlooks the influence of the radicalization ecosystem and its confounding role. Not only are the identified risk factors excessive in number (Clemmow et al., Citation2023), but because many of these risk factors involve common pre-existing propensities of individuals, it is not realistically possible to suppress them all. In addition, as noted above, the existing models have not proven causation or that suppressing the drivers or risk factors would necessarily reduce violent extremism. Therefore, it is futile to address the impact of the candidate drivers and risk factors behind violent extremism while ignoring the ecosystem. Such a conclusion has a direct bearing on the direction of terrorism research.

Now, we consider a different question: How can one ascertain whether the extent of the confounding influence on the radicalization ecosystem is minimal for the nations ()? The latter issue pertains to validating the proposed Salafi theory of extremism.

First, let us consider Kosovo’s case. Muthuswamy (Citation2022) considered Kosovo as a control. As noted in the Introduction, radicalization taking root in formerly-secular Kosovo would not have been possible without Wahhabism’s propagation. Compared to the local religious influence, Wahhabism’s ideological influence may be defined by Sharia as the law of the land, influence that entails the religious leaders, and radical agendas which those leaders espouse. Before Wahhabism was propagated, the Kosovo public hardly knew about the radical agenda of armed jihad (Kepel, Citation2002: p. 239). The country also had very few jihadist fighters until the post-Wahhabi propagation period (KIPRED, Citation2016). Hence, the confounding influence on post-radicalization Kosovo must be defined within the context of Wahhabism. In this case, the confounder must be either a surrogate or proxy for the independent (religious leaders) or mediating (Sharia) variables. However, such a confounder could not exist because of the constraint that, by definition, it could not be a proxy or surrogate for the independent or mediating variables (Judd & Kenny, Citation1981; Skelly et al., Citation2012). Hence, the confounding influence on the radicalization ecosystem in Kosovo must be minimal (Muthuswamy, Citation2022).

Similar arguments can be invoked to extend this result because, similar to the case of Kosovo, Salafi jihadist groups and the fighters associated with them barely existed worldwide before 1980 (i.e., before Wahhabism’s propagation; ). As such, the influence of the confounding factors on the identified radicalization ecosystem must be minimal.

Are there any variables associated with religion omitted from this analysis? Religiosity may be associated with the degree of a person’s commitment to practicing religion, and scholars have debated the role of religiosity in fuelling violent extremism. Most public opinion studies did not find Muslim personal religiosity or piety to be significant positive predictors of support for terrorism or violent extremism (Piazza, Citation2021). Moreover, these studies lacked a framework to define a causal pathway involving religiosity and violence and explain the confounding issues in this context (Dawson, Citation2021a, Citation2021b, & Citation2021c; Schuurman, Citation2021). This study elucidates this issue. Before Wahhabism’s propagation, there was “no prior history of religious militancy” in Muslim-majority Kosovo (Shtuni, Citation2016: p. 1). Moreover, advances the premise that it is not religion per se that led to Salafi extremism, but only those specific narratives of religion emphasized through Wahhabism (prominent among them being the aspiration of Sharia as the law of the land and radical agendas espoused by religious leaders) ensured the emergence of the radicalization ecosystem and violent extremism. Thus, owing to the high values of R2 noted in the Results, other than religious leaders and Sharia, no other variables (omitted variables) associated with religion can significantly contribute independently to the observed correlations with the radical agenda.

Sharia acts as a (partial) mediator between the independent and dependent variables (). Regarding the mediator analysis, the computed (unstandardized) path coefficients for A and C (, Row 5) were 0.32 and 0.46, respectively, when A and C were regressed with B. These significant path coefficient magnitudes reveal that the mediation effect of the Sharia platform dominates over the direct effect of religious leaders influencing the public’s support of radical agendas. Mediation analysis also confirms that Sharia lies on the causal pathway associated with the theory.

The causal mechanism associated with the above-mentioned theory explains why the public support levels presented in are higher for three variables (religious leaders, Sharia, and the radical agenda) in many countries. As noted in the Introduction, unlike Kosovo, these countries typically lacked a secular past and were among the first to be exposed to the propagation of Wahhabism. According to the theory of Salafi extremism, long before the PRC surveys, public support for Sharia experts (religious leaders) and their espoused agendas grew with an increase in public support for the theme of Sharia as the law of the land. provides evidence that the support levels for these three variables increased together; when scaled by the ratio of the average Sharia support levels for the countries where the majority and minority supported Sharia as the law of the land (80.8/22.4), the scaled support levels for the radical agenda and religious leaders as religious judges (Row 2) were remarkably close to the real levels (Row 3). In an environment where public support for Sharia is significant, radical preachers, who typically lack formal training in theology, have captured attention as vocal supporters of Sharia espousing radical agendas (Sullivan, Citation2015). Particularly, Sharia determines the strength of the relationship between independent and dependent variables, as confirmed by the moderator analysis ( – Row 6; Muthuswamy, Citation2022).

Table 4. Average support levels for the radical agenda and religious judges for countries in Table 1.

While there is a great deal of encouragement regarding the theoretical progress of causation, caveats remain. Notably, in nations other than those with strong histories of secularism, additional contributions to the correlations observed in likely stem from prior Islamist ideologies similar to Wahhabism. Before Wahhabism’s worldwide propagation, radical religious leaders – including Hassan al-Banna and Sayyid Qutb in Egypt and Abul Ala Maududi in Pakistan – popularized the theme of Sharia as a “complete” divine guide to life with limited success (Calvert, Citation2010; Owen, Citation2014). These findings reinforce the causal mechanism. However, it took the propagation of Wahhabism for the global Salafi movement to emerge in the 1990s (Haykel, Citation2012; Kepel, Citation2004; Livesey, Citation2005).

The growth of Salafi jihadists outlined in supports the premise that the causal mechanism behind the radicalization process has remained consistent. Consistent with the data in , another survey from Pakistan reveals that those who supported corporal punishment were more supportive of Islamist militancy (Fair et al., Citation2018). Moreover, the outlined theory helps us understand how India’s potent radicalization ecosystem emerged (BBC, Citation2022). The answer lies in the public’s support for Sharia in that 74% of the surveyed Indian Muslims support the existing system of Islamic courts (PRC, Citation2021: p. 20) thanks likely due to religious leaders’ promotion of Sharia (MEMRI, Citation2008). This legitimizing of Sharia paved the way for the radical Islamist outfits to form Darul Khada – an unofficial Sharia court – to sanction violence there (Nanjappa, Citation2022).

The data in and the proposed theory delineate the role of religious leaders and Sharia in forming the radicalization ecosystem and how they influence violent extremism, unlike the candidate drivers and risk factors (Clemmow et al., Citation2023; Khalil et al., Citation2022). Among the 10 nations where the majority of surveyed Muslims favoured Sharia as the law of the land, the role of religious leaders as religious judges, and corporal punishment, home-grown jihadist groups had a strong presence in all but Jordan and Malaysia. Conversely, in the 10 other nations, where only a minority favoured Sharia as the law of the land, home-grown jihadist groups had either a weak presence or none except in Turkey, Russia, and Lebanon. Hence, contrary to Horgan’s assertion (Citation2022, p. 3) that “No clear profile has ever been found”, the public support levels for religious leaders, corporal punishment, and Sharia can measure the extent of radicalization and violent extremism in a community. Even within each nation, those who favoured Sharia were more supportive of religious leaders and the radical agenda. Thus, the causal mechanism associated with Salafi radicalization is religious leaders using the Sharia platform to propagate radical agendas, including that of waging armed jihad. Although this part of the study was conducted with only one specific radical agenda, as outlined in , among those who supported the idea of Sharia as the law of the land, elevated public support levels were also observed in the context of other radical agendas (PRC, Citation2013), namely, stoning adulterers and enforcing the death penalty for renouncing Islam.

The proposed theory underscores the theme’s importance, distinguishing it from radical agendas. The significance of the theory of Salafi extremism and the associated causal inference is that other than religious leaders, any driver of radicalization can only exist as a dependent variable. As radical agendas are dependent variables, it seems appropriate to use their variations to identify the extent of confounding influence.

The theory of Salafi extremism defines causation and explains the associated radicalization ecosystem. Thus, the onset of radicalization sets the stage for the “us versus them” (Berger, Citation2018: p. 24) mindset to develop and act as a precursor to violent extremism, as defined in the theory. Violent extremism is one of the endpoints of radicalization; the others include socioeconomic stagnation brought about by religious leaders’ discouragement of modern education (Haq, Citation2010) and the prevalence of large families brought about by their encouragement of women to have more babies (McCarthy, Citation2011).Footnote5 Unfortunately, the overall impact of the Islamist radicalization ecosystem can be devastating for the affected communities. The evidence supporting this claim comes from comparisons of the evolution of Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan and their respective diasporas in Britain, where these communities share history, language, culture, and culinary habits (Muthuswamy, Citation2014).Footnote6

The insights mentioned above have significant scholarly implications while also being potentially helpful in the context of conflict resolution and addressing the socioeconomic stagnation of radicalized communities. In particular, the public support levels of 89% (for Sharia), 75% (religious leaders), and 72% (corporal punishment) in in the Palestinian Territories suggest the presence of a strong radicalization ecosystem there. Thus, for any political settlement of the Palestine issue (Treisman, Citation2023) to succeed, it should also outline a concurrent strategy to weaken this ecosystem.

If reducing the impact of Sharia is indeed the desired outcome of undercutting the appeal of Islamism practiced by the likes of al-Qaeda, the Islamic State, the Taliban, and Hamas, then one must propagate the idea that Sharia interpretations are primarily religious leaders’ opinions of Islam. Therefore, from a policy framework standpoint, the focus should be on undercutting the appeal of the underlying theme to weaken the destabilizing radicalization ecosystem while still pursuing efforts to reduce violent extremism. Not all forms of terrorism have a well-defined ideological ecosystem, such as Islamist or right-wing varieties; for example, a recent act of terrorism in Illinois appears to be based on the deep-seated, nihilistic hatred of society (Yousef, Citation2022). In such a scenario, the method outlined here is not applicable. Another limitation of this study is that the theme-enabler conceptual framework has only been applied by defining a causal mechanism specific to Islamist extremism. Extending these ideas to other forms, such as right-wing (white) extremism, requires further research. Such an approach would require identifying a causal mechanism specific to right-wing extremism.

Acknowledgments

I want to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1. The Taliban and Salafis hold similar views regarding Sharia and armed jihad. Like the Taliban (Hamid, Citation2021), Hamas (Alsoos, Citation2021) also invokes Sharia. The current study discusses jihad only in the armed context (as a religious war), although there are multiple interpretations of what it entails (Kepel, Citation2002).

2. Derivation of the formula R = 100(Q–0.01*S*P)/(100–S): If a is the total number polled, b represents those who supported the Sharia measure, c represents those who supported the radical agenda of concern, and d represents those who supported Sharia and the radical agenda, then Q/100=c/a, S/100=b/a, and P/100=d/b. Accordingly, R/100=(c – d)/(a – b). Expressing the variables a, b, c, and d in terms of P, Q, and S leads to the above-mentioned equation for R. The said formula for R was used to generate the entries in Columns 6 and 9 from the previous two pairs of columns in . A significant percentage of those surveyed either did not know what to answer or refused to provide an answer to the questions on the said measures (PRC, Citation2013). Their responses were added to the negative category as they were deemed less influenced by the radicalization ecosystem, just like those who gave explicit negative responses. This approximation, if anything, only serves to lower the extent of the quantitative impact of the ecosystem.

3. Here, the Muslim “religious leaders” designation applies to those who, through formal religious training or self-study, are recognized as such by their communities; the term entails command of the scriptures and Islam’s history.

4. The presence of a jihadist group in countries of concern was ascertained on the basis of the data in the START (Study of Terrorism And Responses to Terrorism) database (Muthuswamy, Citation2016: p. 15). The following designations represent the relative strengths of home-grown jihadist attacks: “No” reflects either no known presence of jihadist groups or only a meagre presence of transnational groups such as al-Qaeda and without an occurrence of a terrorist attack in the past five years. “Weak” indicates that the country has not witnessed any major terrorist attack by home-grown jihadists in the past five years, although it has an active presence of home-grown jihadist groups. “Strong” reflects at least one major act of terrorism within the past five years by home-grown jihadists (p. 17).

5. South Asian Muslim religious leaders are trained in religious seminaries called “madrasas.” These seminaries typically utilize a syllabus created in the 17th century that includes Islamic law (Ahmad, Citation2004).

6. The high support levels of radical agenda and the strong presence of jihadist groups () suggest the existence of a potent radicalization ecosystem in Pakistan.

References

- Aboul‐Enein, Y. (2008). The late Sheikh Abdullah Azzam’s books: Radical theories on defending Muslim land through jihad. The Combating Terrorism Center. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep05601

- Ahmad, M. (2004). Madrassa education in Pakistan and Bangladesh. In S. P. Limaye, M. Malik, & R. G. Wirsing (Eds.), Religious radicalism and security in South Asia (pp. 101–115). Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies.

- Al-Saleh, H. (2015). 52 Saudi clerics, scholars call to battle Russian forces in Syria. Al-Arabia. https://english.alarabiya.net/en/News/middle-east/2015/10/05/Fifty-two-Saudi-clerics-scholars-call-for-fight-against-Russian-forces-in-Syria

- Alsoos, I. (2021). From jihad to resistance: The evolution of Hamas’s discourse in the framework of mobilization. Middle Eastern Studies, 57(5), 833–856. https://doi.org/10.1080/00263206.2021.1897006

- Ananth, C. V., & Schisterman, E. F. (2017). Confounding, causality, and confusion: The role of intermediate variables in interpreting observational studies in obstetrics. American Journal Of Obstetrics And Gynecology, 217(2), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.04.016

- Baele, S. J., Brace, L., & Coan, T. G. (2020). Uncovering the far-right online ecosystem: An analytical framework and research agenda. Studies In Conflict And Terrorism, 46(9), 1599–1623. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2020.1862895

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- BBC. (2015, May 15). Profile: Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. British Broadcasting Service. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-27801676

- BBC. (2022, September 28). PFI ban: What is popular front of India and why has India outlawed it? British Broadcasting Service. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-63004142

- Berger, J. (2018). Extremism. MIT Press.

- Berkes, F., & Folke, C. (1998). Linking social and ecological systems: Management practices and social mechanisms for building resilience. Cambridge University.

- Breslow, N., & Day, N. (1980). Statistical methods in cancer research, volume I—the analysis of case-control studies. International Agency For Research On Cancer, 32, 5–338.

- Budtz-Jørgensen, E., Keiding, N., Grandjean, P., & Weihe, P. (2007). Confounder selection in environmental epidemiology: Assessment of health effects of prenatal mercury exposure. Annals Of Epidemiology, 17(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.05.007

- Calvert, C. (2010). Sayyid Qutb and the origins of radical Islamism. Columbia University.

- Carter, J., Maher, S., & Neumann, P. (2014). #greenbirds: Measuring importance and influence in Syrian foreign fighter networks. International Center for the Study of Radicalization. https://icsr.info/2014/04/22/icsr-report-inspires-syrian-foreign-fighters/

- Clemmow, C., Rottweiler, B., Wolfowicz, M., Bouhana, N., Marchment, Z., & Gill, P. (2023). The whole is greater than the sum of its parts: Risk and protective profiles for vulnerability to radicalization. Justice Quarterly, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2023.2171902

- Dawson, J. F. (2014). Moderation in management research: What, why, when, and how. Journal Of Business And Psychology, 29(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9308-7

- Dawson, L. (2021a). Bringing religiosity back. In critical reflection on the explanation of Western homegrown terrorism, (part I). Perspectives On Terrorism, 15(1), 2–16.

- Dawson, L. (2021b). Bringing religiosity back. In critical reflection on the explanation of Western homegrown terrorism, (part II). Perspectives On Terrorism, 15(2), 1–21.

- Dawson, L. (2021c). Granting efficacy to the religious motives of terrorists: A reply to Schuurman’s response to “bringing religiosity back in, parts I and II”. Perspectives On Terrorism, 15(6), 90–96.

- Desmarais, S. L., Simons-Rudolph, J., Brugh, C. S., Schilling, E., & Hoggan, C. (2017). The state of scientific knowledge regarding factors associated with terrorism. Journal Of Threat Assessment And Management, 4(4), 180–209. https://doi.org/10.1037/tam0000090

- Doi, A. A. R., & Clarke, A. (2008). Shariah Islamic law. Ta-Ha.

- Eijk, E. (2010). Sharia and national law in Saudi Arabia. In Otto, J. M. (Ed.), Sharia incorporated: A comparative overview of the legal systems of twelve Muslim countries in past and present (pp. 139–180). Leiden University.

- Ende, W., & Steinbach, U. (2011). Islam in the world today: A handbook of politics, religion, culture, and society. Cornell University Press.

- Fair, C. C., Littman, R., & Nugent, E. R. (2018). Conceptions of Shari’a and support for militancy and democratic values: Evidence from Pakistan. Political Science Research And Methods, 6(3), 429–448. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2016.55

- Fair, C. C., Malhotra, N., & Shapiro, J. N. (2012). Faith or doctrine? Religion and support for political violence in Pakistan. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(4), 688–720. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfs053

- Felter, C. (2018). Nigeria’s battle with Boko Haram. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/nigerias-battle-boko-haram

- Gall, C. (2016). How Kosovo was turned into fertile ground for ISIS. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/22/world/europe/how-the-saudis-turned-kosovo-into-fertile-ground-for-isis.html

- Gates, S., & Podder, S. (2015). Social media, recruitment, allegiance, and the Islamic state. Perspectives On Terrorism, 9(4), 107–116.

- Ghoshal, B. (2010). Arabization: The changing face of Islam in Asia. India Quarterly, 66(1), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/097492841006600105

- Gordon, M. (2022). Degrade and destroy: The inside story of the war against the Islamic State, from Barack Obama to Donald Trump. MacMillan.

- Gøtzsche-Astrup, O. (2018). The time for causal designs: Review and evaluation of empirical support for mechanisms of political radicalisation. Aggression And Violent Behavior, 39, 90–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.02.003

- Haddad, S. (2004). A comparative study of Lebanese and Palestinian perceptions of suicide bombings: The role of militant Islam and socio-economic status. International Journal Of Comparative Sociology, 45(5), 337–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715204054155

- Hamid, S. (2021). Americans never understood Afghanistan like the Taliban did. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/americans-never-understood-afghanistan-like-the-taliban-did/

- Haq, Z. (2010, July 11). Clerics to resist education law. Hindustan Times. https://www.hindustantimes.com/delhi/clerics-to-resist-education-law/story-i0Vbo8wK6DxEYP7cQY5U9H_amp.html

- Harakan, M. A. (1980). Duty of implementing the resolutions. Journal of The Muslim World League, 6, 48–49.

- Haykel, B., (2012). Salafis. In Bowering, G., Crone, P., Kadi, W., Stewart, D. J., Zaman, M. Q., & M. Mirza (Eds.), The Princeton encyclopedia of Islamic political thought (pp. 483–484). Princeton University.

- Hegghammer, T. (2010). The rise of Muslim foreign fighters: Islam and the globalization of jihad. International Security, 35(3), 53–94. https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00023

- Hegghammer, T. (2020). The caravan: Abdallah Azzam and the rise of global jihad. Ambassador’s Brief. https://www.ambassadorsbrief.com/posts/wreiMPKbnvgD8CHhs

- Hill, A. B. (1965). The environment and disease: Association or causation? Proceedings Of The Royal Society Of Medicine, 58(5), 295–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/003591576505800503

- Horgan, J. (2022). Statement of Dr. John Horgan. The United States House of Representatives. https://docs.house.gov/meetings/VR/VR00/20220331/114556/HHRG-117-VR00-Wstate-HorganJ-20220331-U1.pdf

- Jones, S., Vallee, C., Sharb, C., Byrne, H., Newlee, D., & Harrington, N. (2018). The evolution of the Salafi jihadist threat. Center for Strategic and International Studies. https://www.csis.org/analysis/evolution-salafi-jihadist-threat

- Judd, C. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1981). Process analysis: Estimating mediation in treatment evaluations. Evaluation Review, 5(5), 602–619. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X8100500502

- Karazsia, B. T., & Berlin, K. S. (2018). Can a mediator moderate? Considering the role of time and change in the mediator-moderator distinction. Behavior Therapy, 49(1), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2017.10.001

- KCSS. (2015). Report inquiring into the causes and consequences of Kosovo citizens’ involvement as foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq. Kosovar Center for Security Studies. https://www.academia.edu/12481692/Report_inquiring_into_the_causes_and_consequences_of_Kosovo_citizens_involvement_as_foreign_fighters_in_Syria_and_Iraq

- Kepel, G. (2002). Jihad: The trail of political Islam. I.B. Tauris.

- Kepel, G. (2004). PBS Interview. Public Broadcasting Service. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/front/interviews/kepel.html

- Khalil, J., Horgan, J., & Zeuthen, M. (2022). The attitudes-behaviors corrective (ABC) model of violent extremism. Terrorism And Political Violence, 34(3), 425–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2019.1699793

- King, G., Keohane, R. O., & Verba, S. (1994). Designing social inquiry: Scientific inference in qualitative research. Princeton University Press.

- King, M., & Taylor, D. M. (2011). The radicalization of homegrown jihadists: A review of theoretical models and social psychological evidence. Terrorism And Political Violence, 23(4), 602–622. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2011.587064

- KIPRED. (2016). What happened to Kosovo Albanians: The impact of religion on the ethnic identity in the state-building period. Kosovar Institute for Policy Research and Development. http://www.kipred.org/repository/docs/What_happened_to_Kosovo_Albanians_740443.pdf

- Knell, Y. (2023). Hamas attack shocks Israel, but what comes next? BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-67043563

- Kull, S., Ramsay, C., Weber, S., Lewis, E., Mohseni, E., Speck, M., Cliolek, M., & Brouwer, M. (2007). Muslims believe US seeks to undermine Islam. World Public Opinion. http://worldpublicopinion.net/muslims-believe-us-seeks-to-undermine-islam/

- Lacey, R. (2009). Inside the kingdom: Kings, clerics, modernists, terrorists, and the struggle for Saudi Arabia. Viking Press.

- Lane, D. (2023). Sampling distribution of the mean. Onlinestatbook. https://onlinestatbook.com/2/sampling_distributions/samp_dist_mean.html

- Livesey, B. (2005). The Salafist movement. Public Broadcasting Service. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/front/special/sala.html

- Macfarquhar, N. (2009). Fatwa overload: Why Middle East sheiks are running amok. Foreign Policy. http://foreignpolicy.com/2009/04/17/fatwa-overload/

- Maher, S. (2016). Salafi jihadism: The history of an idea. Hurst.

- Mandaville, P., & Hamid, S. (2018). Islam as statecraft: How governments use religion in foreign policy. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/FP_20181116_islam_as_statecraft.pdf

- McCarthy, J. (2011). In Pakistan, birth control and religion clash. National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/2011/08/10/139382653/in-pakistan-birth-control-and-religion-clash

- Mearsheimer, J. J., & Walt, S. M. (2013). Leaving theory behind: Why simplistic hypothesis testing is bad for international relations. European Journal Of International Relations, 19(3), 427–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066113494320

- Meijer, R. (2010). Global salafism: Islam’s new religious movement. Oxford University.

- MEMRI. (2002). [Saudi government paper]. Billions spent by Saudi royal family to spread Islam to every corner of the earth. The Middle East Research Institute. https://www.memri.org/reports/saudi-government-paper-billions-spent-saudi-royal-family-spread-islam-every-corner-earth

- MEMRI. (2008). Conference issues declaration against terror, blames “tyrant and colonial master of the West (i.e., U.S.)” for aggression in Muslim world. The Middle East Research Institute. https://www.memri.org/reports/indian-clerics-anti-terror-conference-issues-declaration-against-terror-blames-tyrant-and. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/etudes/join/2013/457137/EXPO-AFET_ET(2013)457137_EN.pdf

- Muhammad, P. (2012). Conference on fatwas: Discouraging issuance of edicts by non-state actors. Express Tribune. http://tribune.com.pk/story/474259/conference-on-fatwas-discouraging-issuance-of-edicts-by-non-state-actors/

- Muthuswamy, M. (2014). Sharia as a platform for espousing violence and as a cause for waging armed Jihad. Albany Government Law Review, 7(2), 347–378. https://www.albanygovernmentlawreview.org/article/23938-sharia-as-a-platform-for-espousing-violence-and-as-a-cause-for-waging-armed-jihad

- Muthuswamy, M. S. (2016). The role of Sharia and religious leaders in influencing violent radicalism. Science, Religion And Culture, 3(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.src/2016/3.1.1.18

- Muthuswamy, M. S. (2018). A conceptual framework of Salafi radicalization: An underlying theme and its enablers. Science, Religion And Culture, 5(1), 50–72. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.src/2018.5.1.50.72

- Muthuswamy, M. S. (2022). Does Sharia act as both a mediator and moderator in Salafi radicalism? Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2030452

- MWL. (2014). Muslim World League. http://www.themwl.org/Profile (Retrieved January 19, 2014).

- Nanjappa, V. (2014). 25k Wahhabi scholars visited India last year – Vicky Nanjappa. Bharatha Bharathi. https://bharatabharati.in/2014/07/05/25k-wahhabi-scholars-visted-india-last-year-vicky-nanjappa/

- Nanjappa, V. (2022). Killing of Umesh Kolhe puts focus on Islamic Darul Khada which supersedes Indian police, judiciary. One India. https://www.oneindia.com/india/killing-of-umesh-kolhe-puts-focus-on-islamic-darul-khada-which-supercedes-indian-police-judiciary-3501828.html?

- Nielsen, R. (2017). Deadly clerics: Blocked ambition and the paths to jihad. Cambridge University.

- NSCT. (2018). National strategy for counterterrorism of the United States of America. The White House. https://www.dni.gov/files/NCTC/documents/news_documents/NSCT.pdf

- Owen, J. M. (2014). Confronting political Islam: Six lessons from the West’s past. Princeton University.

- PE. (2007). Living apart together: British Muslims and the paradox of multiculturalism. Policy Exchange. https://policyexchange.org.uk/publication/living-apart-together-british-muslims-and-the-paradox-of-multiculturalism/

- Perez, E. (2023). Secure communities: Stopping the Salafi jihadi surge in Africa. American Enterprise Institute. https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/secure-communities-stopping-the-salafi-jihadi-surge-in-africa

- Peters, R. (2006). Crime and punishment in Islamic law: Theory and practice from the sixteenth to the twenty-first century. Cambridge University.

- Piazza, J. (2021). ‘Nondemocratic Islamists’ and support for ISIS in the Arab World. Behavioral Sciences Of Terrorism And Political Aggression, 13(2), 95–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/19434472.2019.1707257

- PRC. (2013). The world’s Muslims: Religion, politics, and society. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewforum.org/files/2013/04/worlds-muslims-religion-politics-society-full-report.pdf

- PRC. (2021). Religion in India: Tolerance and segregation. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/06/29/religion-in-india-tolerance-and-segregation/

- Rashad, M. (2021). Saudi Arabia announces new judicial reforms in a move towards codified law. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-saudi-judiciary/saudi-arabia-announces-new-judicial-reforms-in-a-move-towards-codified-law-idUSKBN2A82E6

- RK. (2015). Strategy on prevention of violent extremism and radicalisation leading to terrorism 2015–2020. The Republic of Kosovo. https://www.rcc.int/swp/download/docs/2%20STRATEGY_ON_PREVENTION_OF_VIOLENT_EXTREMISM_AND_RADICALISATION_LEADING_TO_TERRORISM_2015-2020.pdf/4d72f7e1c78abc68574956006556cdf4.pdf

- Robinson, K. (2021). Understanding sharia: The intersection of Islam and law. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/understanding-sharia-intersection-islam-and-law

- Schuurman, B. (2021). The role of beliefs in motivating involvement in terrorism: A response to Lorne L. Dawson’s article “bringing religiosity back in: Critical reflection on the explanation of Western homegrown religious terrorism (parts I and II)”. Perspectives On Terrorism, 15(5), 85–92.

- Shtuni, A. (2016). Dynamics of radicalization and violent extremism in Kosovo. United States Institute of Peace. https://www.usip.org/publications/2016/12/dynamics-radicalization-and-violent-extremism-kosovo

- Skelly, A. C., Dettori, J. R., & Brodt, E. D. (2012). Assessing bias: The importance of considering confounding. Evidence-Based Spine-Care Journal, 3(1), 9–12. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1298595

- Stephens, W., Sieckelinck, S., & Boutellier, H. (2021). Preventing violent extremism: A review of the literature. Studies In Conflict And Terrorism, 44(4), 346–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2018.1543144

- Sullivan, K. (2015). Police call him an ISIS recruiter. He says he’s just an outspoken preacher. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/police-call-him-an-isis-recruiter-he-says-hes-just-an-outspoken-preacher/2015/11/23/924d8f6e-8a15-11e5-9a07-453018f9a0ec_story.html

- Treisman, R. (2023). Biden wants a two-state solution for Israeli-Palestinian peace. Is it still possible? National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/2023/10/27/1208694837/two-state-solution-israeli-palestinian-conflict

- Varagur, K. (2017). Saudi Arabia is redefining Islam for the world’s largest Muslim nation. Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/03/saudi-arabia-salman-visit-indonesia/518310/

- Varagur, K. (2020). The call: Inside the global Saudi religious project. Columbia University.

- Walter, B. (2017). The extremist’s advantage in civil wars. International Security, 42(2), 7–39. https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00292

- Yousef, O. (2022). Why the Highland Park suspect represents a different kind of violent extremism? National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/2022/07/06/1110013040/the-highland-park-suspect-breaks-the-mold-on-violent-extremists