ABSTRACT

Previous research has shown that products labeled as ‘Protected Designation of Origin’ (PDO) correlate positively with indicators for landscape sustainability. However, specific factors that turn PDO products into sustainable landscape management tools remain vague. We analyze interviews from six European production systems to explore the links between PDO-labeled products and sustainable landscape management. All case studies were linked to extensive animal husbandry. We found that PDO products can contribute to sustainable landscape management if well-adapted incentives for agri-environmental measures supplement income. Successful products are further associated with local networks that use synergies between different stakeholder interests. Due to their promotion of social-ecological goals at the landscape level, PDO products can be a powerful addition to the EU’s Green Deal and rural development strategy, and by introducing eligibility criteria that focus on social-ecological goals, PDO labeling could be classified as a sustainability standard.

1. Introduction

1.1. Sustainable landscape management as a paradigm for European agricultural landscapes

Current agricultural intensification in Europe tends to result in monotonous landscapes with reduced cultural values (Tieskens et al., Citation2017; van Vliet et al., Citation2015) and lower biodiversity (Bouwma et al., Citation2019; Mupepele et al., Citation2021). Agriculture in the European Union is aligned through its Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Despite various reforms for ‘greening’, the schemes and regulations making up CAP remain mostly oriented toward an efficient and market-oriented production of food, feed, and biofuels (Pe’er et al., Citation2019) that do not fulfill its environmental goals (Pe’er et al., Citation2020). The European Commission launched the ‘European Green Deal’ (European Commission, Citation2019), which includes the ‘Farm to Fork’ strategy, aiming to unify economically viable and ecologically sound agriculture while ensuring the successful development of rural regions (Schebesta & Candel, Citation2020). These goals can be pursued in an integrated way by applying the concept of ‘sustainable landscape management’ (SLM), also known as ‘integrated landscape management’. This concept entails the simultaneous management of food and fiber production, as well as the conservation of biodiversity and other ecosystem services, while fostering human well-being (Plieninger et al., Citation2020). Researchers have described SLM as a useful concept for achieving sustainable development goals, covering a broad range from ecological sound practices to improved rural livelihoods (Angelstam et al., Citation2019; Bürgi et al., Citation2017). A remarkably comprehensive set of principles for SLM was proposed by Scherr et al. (Citation2015). According to them, sustainable/integrated landscape management is defined by: 1) agreement among stakeholders on multiple landscape objectives; 2) shared management of synergies and trade-offs among different landscape uses; 3) management practices that contribute to multiple landscape objectives; 4) supportive markets, policies, as well as incentives; and 5) collaborative decision-making for and by the stakeholders. In this paper, we used these five principles to evaluate the potential of PDO production systems to be a key instrument for SLM.

However, sustainability at the landscape level is not well-defined within the CAP and it is subordinated to sustainability strategies like ‘Farm to Fork’. Therefore, a better understanding of the practical issues that farmers, landscape managers, and other stakeholders experience is needed when trying to implement or maintain the principles of SLM. In the context of SLM, an agriculturally productive landscape can be seen as a management unit that comprises many aspects of sustainability, and where within a specific spatial dimension challenges can be addressed in an integrated way (Tanentzap et al., Citation2015). Bringing together production and conservation aims (O’Farrell & Anderson, Citation2010) makes the SLM concept especially useful for a specific type of agricultural product – the landscape product. It appears sensible to focus on landscape products in this study, as their multifunctional characteristics can be seen as best practice cases for SLM. Landscape products are defined by their distinct geographic origin, low-input management in combination with traditional practices, and their perception as high-quality products leading to high revenues (García-Martín et al., Citation2022). This study thus addresses the lack of knowledge that presently exists on the potential benefits of geographically distinct products to SLM.

1.2. Geographical indications as instruments for sustainable landscape management

Implementing SLM requires different instruments, policies, and multi-stakeholder governance. A recent instrument, considered in the ‘Farm to Fork’ strategy, is geographical indications labeling (European Commission, Citation2020). Geographical indications, one of which is the ‘Protected Designation of Origin’ (PDO), can be seen as prime examples of landscape products. Geographical indications aim to combine traditional production techniques, unique landscape resources, and high-quality products (Arfini, Citation2019). Overall, products labeled as geographical indications have been shown to positively correlate with several social-ecological indicators (Milano & Cazella, Citation2021). Among the geographical indications of the EU, the PDO label is the strongest certification that protects agricultural products according to their geographic origin, including product names as intellectual property rights. Previous studies have related PDO products to successful agro-ecological practices (Belletti et al., Citation2015; Owen et al., Citation2020), or tested specific indicators for their correlation with the numbers of PDO products in a given region (Flinzberger, Zinngrebe, et al., Citation2022). Indicators such as the amount of semi-natural or extensively managed agricultural lands (e.g. agroforestry systems, high nature value farmland), or cultural values based on world heritage sites and tourism indicators (Flinzberger, Zinngrebe, et al., Citation2022) were related to PDO production. In another study, Flinzberger, Cebrián-Piqueras, et al. (Citation2022) revealed connections between PDO products and certain rural landscape typologies in Europe, showing that agricultural landscapes of high environmental value correlate with PDO products across Europe, while the correlation of PDO products with issues of structural change was predominantly found in the Mediterranean region.

For PDO-labeled products, their whole production process (including growing feed, processing, and packaging) has to take place within the designated geographical region (Belletti & Marescotti, Citation2011; European Council, Citation1992). Understanding PDO products as directly linked to a certain landscape (Brock, Citation2023; García‐Martín et al., Citation2021) implies recognizing that their production interacts with the social-ecological trends of that geographical area (Allen & Prosperi, Citation2016; Vakoufaris et al., Citation2014). That includes considering environmental and biodiversity aspects, traditions, food culture, local identity, rural development, and tourism (Cei et al., Citation2021; Lamine et al., Citation2019). This means that the influence of PDO products reaches beyond productivity and economic aspects, into the arena of landscape governance. Meyfroidt et al. (Citation2022) introduce ‘distant connections’ as a potential source of issues regarding temporal or spatial spillover effects. Distant connections can also help to communicate unique landscape characteristics from producers to consumers and thereby support SLM. For example, in comparison with other certification processes like organic certification, geographical indications comprise more aspects of traditional production techniques and landscape characteristics, which are often tightly linked to landscape management. The market success of products with a regional reputation is therefore also influenced by the social-ecological values transmitted through the product and by the marketing (Arfini et al., Citation2011; Barjolle & Sylvander, Citation1999). Those values, in particular, are deeply embedded into the product by its place and culture of origin (Arfini et al., Citation2019; Raimondi et al., Citation2018). PDO products are potentially helpful in promoting rural development, counteracting rural exodus, and contributing to local livelihoods (Dal Ferro & Borin, Citation2017). Due to their characteristics as landscape products, geographical indications might also contribute to a change in the understanding of agricultural products. Agricultural products turn from a commodity into a flagship item of ‘landscape’ management, which can be perceived as part of the commons (García-Martín et al., Citation2022). The statistical and generalizing nature of previous approaches and reviews has not allowed a conclusion of direct causal relationships (Meyfroidt, Citation2016).

1.3. Development of PDO products through landscape governance

Considering the plurality of stakeholder interests linked to landscapes, there is a need to analyze synergies and potential trade-offs through a case-based qualitative approach. In this study, we explored how various landscape management stakeholders (i.e. producers, conservationists, administration, and regional marketing) attribute certain principles of SLM to the current production practices of PDO products. This is a necessary first step to operationalize the aforementioned ‘distant connections’ that PDO products offer in order to implement actual changes in land management policies. Additionally, we synthesized the articulated needs of stakeholders for maintaining or implementing certain SLM principles within their PDO production systems. By including different types of stakeholders in PDO food systems, we uncovered multiple perceptions of SLM. Thereby, we treated the investigated landscapes as commons with multiple benefits and not only as privately owned production resources. We selected case studies related to the production of animal-based products, namely cheese and meat, as these are the most relevant product categories of the EU’s geographical indications scheme in terms of registered products and achieved revenues. The selected PDO products are all linked to landscapes whose management includes extensive grazing systems or the use of animals for pasture management. To gain insights into stakeholders’ perceptions of the links between SLM and PDO production, we designed our interviews to answer the following research questions:

Which characteristics of PDO production systems contribute to sustainable landscape management?

Which conditions enable PDO production stakeholders to harness the system’s potential?

Whereas the results section is structured according to the identified phenomena; the research questions are addressed in the discussion, where we reflect on the current state of PDO production and the potential role of PDO products in future support schemes for SLM.

2. Methods

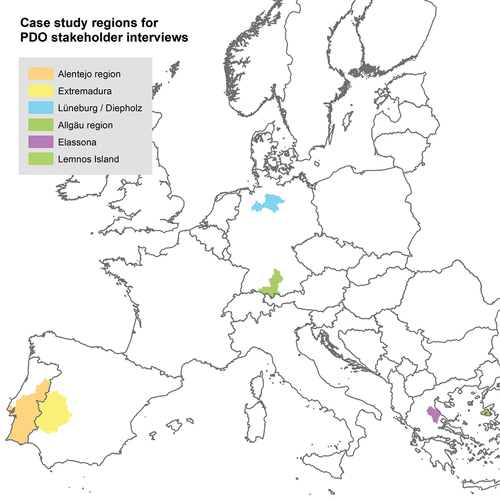

The study is based on 46 qualitative interviews with stakeholders collected in six different regions in Germany, Portugal, Spain, and Greece. The location of the case study regions in Europe is displayed in . The interviews were carried out between December 2021 and May 2022. To account for the dependencies between different sustainability aspects, we picked a method that focuses on structural overlaps in the interview material. The ‘Phenomenon-Centered Text Analysis’ (PTA) developed by Krikser and Jahnke (Citation2021), which was also used previously in other fields of science (Wagemann et al., Citation2022), allowed for focused interpretation of overlapping content between individual categories (codes).

Figure 1. Map of Europe highlighting the locations of the six case study regions.

2.1. Selecting cases and interview partners

We selected a subset of similar PDO cases that were comparable in terms of landscape management while representing variations of food cultures across different EU regions. We excluded ‘Protected Geographic Indication’ (PGI) products because this label only requires one production step to be carried out within the respective region and thus can be less influential on landscape management. Study sites were selected based on the following three criteria: a) PDO production system is based on extensive animal husbandry or grassland management systems because in these cases there is an undeniable connection between landscape management and PDO production; b) farmlands can be considered as high nature value farmlands because they correlate particularly well with the production of PDO-labeled foods (Flinzberger, Zinngrebe, et al., Citation2022); and c) regions with PDO-labeled animal-based products (meat and cheese), because some of the most iconic cultural landscapes in Europe are managed with the help of grazing and herding. The cases were situated in the heathlands and bog landscapes of northern Germany (counties of Lüneburg and Diepholz), in alpine pasture landscapes of southern Germany (the Allgäu region), in the Mediterranean oak woodlands of Spain (Extremadura autonomous community) and Portugal (Alentejo region, incl. five intermunicipal communities), in the semi-mountainous areas of central Greece (Elassona municipality), and on the Greek island of Lemnos (Lemnos county). As illustrated in , the selected landscapes are different due to their geographical locations, but at the same time, they share common visual features such as shrubs or trees, and a semi-natural appearance. The products across all study sites include cow, sheep, and goat cheeses, as well as beef, ham, lamb, and goat meat (). For each of the six production systems with a distinctive landscape, we interviewed a minimum of five PDO actors to represent a diversity among relevant stakeholder groups: PDO-registering organizations, local producers, processing or marketing companies, tourism agencies, and landscape management or conservation experts.

Figure 2. Typical views on extensively managed landscapes from our six case study regions. a) cattle in Ribatejo region, Portugal (photo by Conceição Caldeira); b) terraced fields mixed with oak trees in Extremadura, Spain; c) sheep in the heath meadows around Lüneburg, Germany (photo by Willow on Wikimedia Commons [CC-BY 2.5]); d) semi-mountainous pastures in the Lemnos region close to Mt. Olympus National Park, Greece (photo by Vasileios Deligiannis); e) nutrient-poor grasslands with goats on Lemnos island, Greece (photo by Danae Sfakianou); f) cattle in touristically used alpine pastures in the Allgäu region, Germany (photo by Marlene Haiberger on unsplash).

![Figure 2. Typical views on extensively managed landscapes from our six case study regions. a) cattle in Ribatejo region, Portugal (photo by Conceição Caldeira); b) terraced fields mixed with oak trees in Extremadura, Spain; c) sheep in the heath meadows around Lüneburg, Germany (photo by Willow on Wikimedia Commons [CC-BY 2.5]); d) semi-mountainous pastures in the Lemnos region close to Mt. Olympus National Park, Greece (photo by Vasileios Deligiannis); e) nutrient-poor grasslands with goats on Lemnos island, Greece (photo by Danae Sfakianou); f) cattle in touristically used alpine pastures in the Allgäu region, Germany (photo by Marlene Haiberger on unsplash).](/cms/asset/5663e44b-53c3-4043-a08a-1d6f94c8fbe6/tlus_a_2326321_f0002_oc.jpg)

Table 1. Study regions, their geography, and the included PDO products in these regions.

2.2. Interviews, transcriptions, and coding

The interviews were conducted as semi-structured interviews, using guiding questions to stimulate the narrative process. The interview guideline is available within the supplementary material (Annex 1). Two open-ended questions at the beginning asked what the interviewees associated with their landscape. The second interview section focused on relations between the PDO product and landscape management practices, as well as cultural and economic trends within the region. In the final interview section, respondents could talk about political, cultural, and economic conditions that support or hinder their PDO system’s success and their ideas on how to make PDO products a more successful instrument for SLM. Because of the semi-structured style of the interviews, the context of answers was comparable enough to use a statement-oriented transcription, noting key statements and relevant information during the interviews, and refining it based on the audio recordings afterward (Clausen, Citation2012). The refined transcriptions were translated into English before being processed with MAXQDA software (VERBI – Software, Citation2010).

We coded the raw interview material using an inductive approach. Thus, we assigned separate codes to all aspects of SLM under the PDO regime as they emerged from the interviews. Landscape management practices as well as management outcomes were both considered, accompanied by remarks on the landscape-product relationships, and statements about current and potential PDO policies. For structural simplification, the inductively derived codes referring to landscape management were grouped into nine coding categories (). This simplification was done because the phenomenon-centered text analysis (PTA) method required more generalized coding categories. Those nine coding categories (listed under ‘Social-ecological aspects’ in ) were used for the PTA as described below. Text segments coded with ‘Associations’ and ‘PDO-plus’ were analyzed separately, without being part of the PTA, yielding background information on the cases.

Table 2. Codes used for structuring the interview material with a detailed description of each code.

2.3. Phenomenon-centered text analysis

Combining aspects of quantitative and qualitative text analysis, the phenomenon-centered text analysis (PTA) helped to uncover six social-ecological phenomena within the interview material by pointing out connections between single coding categories. Based on the transcribed and translated interview material we assigned codes to each text segment like for any common qualitative text analysis. We continued with a content analysis for each code separately (Annex 2), which later helped with the qualitative descriptions of how the codes are linked within the phenomena. Using the MAXQDA code-matrix browser, we calculated the number of text segments per code and per interview within each stakeholder group (Annex 3.1 and 3.2). We found that the different codes appeared relatively even throughout all actors and regions. The only major differences occurred for the ‘Animal welfare’ code which was often used in the interviews from the Allgäu and barely used in the interviews from Extremadura, and the ‘Quality’ code, which was used relatively often in the context of Extremadura, but barely in the interviews from Lower-Saxony.

The PTA method follows the assumption that codes that frequently appear in proximity also share a common underlying concept or cause and form a contextual phenomenon. We defined proximity as interview segments overlapping or lying directly next to each other. Subsequently, we counted the overlaps, using the MAXQDA code-relations browser with the ‘near’ function enabled and the maximum distance set to zero (VERBI, Citation2020). According to Krikser and Jahnke (Citation2021), we considered all relations between codes as relevant which counted more than half of the maximum overlaps. In our case, the maximum number of overlaps was 38 and thus all relations with 19 or more overlaps were considered. In total we identified six relationships between codes, the so-called ‘phenomena’. The codes ‘Animal welfare’ and ‘Quality’ were not related to any phenomenon. The final step of the PTA was an in-depth qualitative analysis of every text segment related to a phenomenon to describe how the overlapping aspects interact on a landscape scale. The description of these so-called phenomena is also called ‘micro-theories’ (Krikser & Jahnke, Citation2021). The codes for ‘Landscape’ and ‘Income’ were most prevalent within the different phenomena and thus, they are discussed as cross-sectoral aspects.

3. Results

The following section shows how different aspects of sustainable landscape management (SLM) are related to each other within PDO production systems. The six phenomena (identified through the PTA method) each represent one set of overlapping sustainability aspects (). Each phenomenon is summarized and illustrated with direct quotes from the interviews. Commonalities and variations amongst different product types and case study regions regarding PDO implementation are highlighted. A full list of quotes (including additional quotes and extended statements) is available in the supplementary material, as are the summaries of the phenomenon-unrelated codes ‘Animal welfare’ and ‘Quality’ (Annex 4). The quotes are numbered sequentially in their order of appearance, including the quotes from the annex.

Table 3. Result from the ‘code-relations-browser’ from MAXQDA showing the number of overlapping and nearby coded text segments among the nine codes used for the PTA. All codes that have equal to or more than half of the maximum overlaps (38) are emphasized by bold-italic numbers. In the lower half, the six identified phenomena are listed with the number of overlaps given in brackets.

3.1. Social-ecological phenomena of PDO production

3.1.1. P1 – Landscape-Environment: PDO production landscapes support biodiversity and ecosystem services

In all regions, the presence of livestock and traditional farming practices were perceived as a crucial element for maintaining landscape aesthetics with fewer trees (e.g. Dehesa or Montado) or no trees at all (e.g. heath- or peatlands). Producers or breeders insisted on grazing animals as the custodians of landscape aesthetics and emphasized animal breeds’ suitability for grazing on less-productive or difficult-to-farm land. This comes along with high biodiversity values, such as habitats for threatened bird species, that were maintained through grazing or herding and complemented by diverse structures like trees, shrubs, or ponds:

Q1: ‘The land […] is only suitable for grazing […] and the “Heidschnucke” [local sheep breed] is especially suitable for transferring nutrients from the heathland to the pastures. It is a totally extensive form of grazing, where no fertilization is used. […] many flowers and plants, birds, and reptiles live here – that means high biodiversity.’ (R9: producer from Lüneburg)

There was a major difference between milk and meat production in Extremadura. While grazing sheep and goats, which are kept mainly for milk production, contribute to maintaining the open landscapes, pigs raised for ham production almost entirely forage on acorns. In this case, the maintenance of the open landscape with holm oak forests must be supported by manual labor. That also means that large parts of the iconic mosaic-like agroforestry systems in the Spanish Dehesa and the Portuguese Montado need human maintenance:

Q2: ‘The Dehesa is not a natural landscape; it is human-made. Instead of having a closed canopy, the open landscape supports a strong ecological diversity.’ (R22: conservation expert from Extremadura)

This mix of grazing animals and human maintenance also helps to mitigate large wildfires, which is perceived as a key benefit of maintaining open landscapes that would be lost in case of abandonment.

At the same time, PDO production landscapes were described as threatened by more profitable and water-intensive crops such as vegetables or pineapples. Statements about the competition for land and water also highlighted the environmental harm that intensive systems can inflict.

Q3: ‘The cork oak forest [montado] does not need to be watered, the montado lives well with the climatic conditions that exist and feeds that ecosystem without any disruption. These new agricultural practices that threaten the montado are highly predatory of the water resource.’ (R45: tourism representative from Alentejo).

Similarly, the Greek producers from Elassona stressed the importance of keeping the landscape and its bio-physical resources intact to maintain the current system and keep the PDO certification.

3.1.2. P2 – Landscape-Income: market incentives and support measures can strengthen sustainable landscape management in PDO production systems

Landscape management practices across the case study regions, such as breeding and raising livestock for extensive farming, have a common goal: to generate income. This happens through selling products, receiving financial support, or payment for ecosystem services (i.e. rewarding land managers for the conservation of biodiversity and ecosystem services). We found regional differences regarding the main motives for landscape management depending on the dominant type of income. In regions with economically successful PDO products, such as the Allgäu or Extremadura, landscape management was more production-oriented while still relying on traditional farming systems. In cases where a larger proportion of income came from financial support measures or nature conservation funds, such as in the peat and heath landscapes of northern Germany (‘Lüneburger Heide’ and ‘Diepholzer Moor’), landscape management decisions were guided by nature protection goals. Economically barely viable value chains led to a high degree of dependency on financial support or contractual nature conservation:

Q8: ‘One would have to communicate that sheep have a high value for landscape maintenance, […] It needs higher prices [for meat] but you do something good for climate and biodiversity. […] but in the background the land conservation association sponsors it.’ (R10: conservation expert from Diepholz)

While most respondents highlighted the importance of financial support for the maintenance of PDO production landscapes, the suggestions were quite different. Wherever the products were sold along relatively stable value chains (e.g. Extremadura, or the Allgäu), the respondents demanded support through product marketing or agriculture policies.

Q9: ‘What we do should work in the long term, and for this, there must be a certain economic viability. This includes subsidies and support measures of the agricultural policy, but also income from the products is central. Production is only sustainable over time if there is profitability through production’ (R1: conservationist from the Allgäu)

In regions where the PDO products were less profitable (e.g. ‘Diepholz Moorschnucke’ or ‘Kalathaki Limnou’), respondents asked for more direct support for product commercialization. Increased income then could support local livelihoods and SLM practices:

Q10: ‘Support for the regional economy is needed very much. The island has a very large percentage of people engaged in animal husbandry and agriculture in general, so products like the Kalathaki help the economy a lot.’ (R36: producer from Lemnos)

3.1.3. P3 – Landscape-Diversification: traditional landscapes are central to tourism activities

The landscape-diversification phenomenon represents the specific relationship between landscape and tourism because tourism was the single most important aspect of economic diversification and thus regional income in all our study regions. This exemplifies the coexistence of different services that landscapes offer. Respondents mentioned for example landscape as aesthetic spaces, wildlife experience, tranquility, and possibilities for recreation as important factors for tourism:

Q12: ‘The extensive areas further away from the farms represent the Allgäu in terms of tourism and aesthetics. There are those beautiful alpine areas below the tree line with open meadows that blossom so beautifully’. (R1: conservation expert from the Allgäu)

Many primary producers were too occupied with agricultural work to add diversification to their portfolio. As expected, regions with an integrated landscape-tourism strategy and active governance bodies did much better regarding this relationship. Especially the Allgäu and Extremadura regions developed regional brands entailing environmental tourism, and gastronomic specialties:

Q13: ‘In Extremadura, there are many shops geared towards tourism. We sell our cheese there. […] Tourists come from Madrid at Easter and buy local products in the shops that they can’t buy in a large supermarket. Here they come to eat more traditional and organic products.’ (R19: producer from Extremadura)

In the northern German study areas, the extensively managed landscape attracts recreational tourism as well, but the productive aspect of the PDO is rather small. In this context, we found that there is a sentiment that ‘sustainability’ should not be used for tourism marketing. The Spanish ‘regulatory councils’, which were considered very supportive regarding advertising the PDO products as landscape products, mainly focus on products as regional and gastronomic specialties and not so much on sustainability. Although the income from tourism seemed almost unrelated to the PDO production itself, it heavily depends on landscapes, culture, and gastronomy in all investigated regions:

Q14: ‘As a hotel professional with restaurants […], our relation with kalathaki [local cheese] has absolute relevance because we believe that […] the local product should be supported. Regionality in general, as a basis for promotion and the touristic development on the island, has an absolute relation to the primary sector.’ (R34: tourism stakeholder from Lemnos)

3.1.4. P4 – Environment-Governance-Legacy: conditions for continued PDO existence

According to our respondents, governance plays an important role in both protecting environmental values, and the future of the products, hence the continued legacy of traditional production and landscapes. Overall, it was stated that more support from CAP would be necessary to keep up traditional production and that CAP payments should be more targeted towards provisioning and cultural services. Especially in the case of PDO products with a lower production volume, supportive instruments and a better integration of environmental and agricultural regulations were demanded to keep the systems alive:

Q18: ‘Depending on the leasing contract, different agri-environmental measures are counted as double subsidies. Those who don’t know better make contracts that are unfavorable for shepherds.’ (R10: conservation expert from Diepholz)

Regarding the governance aspect of their product’s legacy, many respondents reported about problematic regulations for livestock production and demanded financial incentives for adopting innovations. In parallel, provisioning ecosystem services (provision of hay, grass, acorns, etc.) was called crucial for the continued existence and ensuring certain quality traits of the products:

Q19: ‘Having animals grazing directly in natural pastures and sown pastures in well-managed cork oak forest improves the milk quality for cheese production.’ (R42: producer from Alentejo)

Respondents also referred to cultural ecosystem services, in the form of recreational areas, touristic attractiveness, and aesthetic values. They stressed that cultural services have their foundations in the historically grown landscape management practices, such as herding, grazing, or mountain agriculture:

Q20: ‘People want to buy immersive experiences in nature that are harmless to nature, they want to fully enjoy it, they want to take with them the products that the cork oak forest (montado) produces.’ (R45: tourism representative from Alentejo)

3.1.5. P5 – Income-Governance: a high demand for political and financial support

Respondents stated that political and financial support measures are necessary to keep up traditional production. They demanded that politics should do more to generate or stimulate income from PDO products. From the producers’ views in particular, CAP should provide more support for low-intensity and less profitable animal farming systems. Further, they demanded reduced administrative efforts and streamlined conservation regulations with agricultural support policies, as illustrated by a response from Germany:

Q24: “Lower Saxony guidelines demand single annual grazing, which then qualifies for a grazing premium. Nature conservation administration demands however grazing three times per year. […] there are contradictions between nature conservation administration and commercial management.“ (R13: producer from Diepholz)

Many respondents demanded more targeted payments for the ecosystem services they produce or deliver to the public. Respondents from northern Germany in particular demanded long-term commitments regarding land access rights for maintaining livestock systems without economic risks. Further, respondents expressed the need for administrations to bear additional management expenses, for example, costs stemming from new food safety regulations, or costs for offsetting damages done by wolves:

Q25: ‘Five years is a short period [for contractual nature conservation] and a loss of the funding afterwards would threaten the existence of shepherds. Longer funding periods would be needed for such livestock projects.’ (R11: producer from Diepholz)

Also, regional administrations could support the producers by bearing the costs of centralized marketing efforts. In general, Mediterranean products appeared to be better represented by centralized PDO marketing agencies. Interviewees in Extremadura stressed that the economic success of their products is largely based on network structures that connect different PDO products as well as gastronomy and tourism:

Q26: ‘The offices promoting the labels and certified products do an incredible job. We are doing just fine in this regard. […] Political investments into structures and marketing are essential to maintain the production system.’ (R25: producer from Extremadura)

Other governance measures can have positive effects on rural livelihoods; for example, by offering and maintaining affordable infrastructure (e.g. internet, commuting). In the remote areas of Extremadura and Elassona, this was seen as important as income to counteract rural exodus.

3.1.6. P6 – Income-Culture: traditions around food culture and management practices make PDO production financially viable

This phenomenon highlights the fact that income for rural communities was connected to the traditional management practices and the resulting products by many respondents. Whether the food culture or the food-related income evolved first, was seen differently among the respondents. However, they agreed that maintaining the traditional low-intensity management practices would be necessary to maintain the uniqueness of the PDO landscapes, but also that despite traditional aspects, they need to adapt to modern requirements of food production:

Q30: The breeder is a businessman, […] so the first thing we need to see is whether traditional techniques can be financially viable. Also, […] traditional techniques must keep pace with modern food hygiene requirements. (R37: conservationist from Lemnos)

While local identity was an aspect related to PDO production everywhere, gastronomy was more important in the Mediterranean countries. The gastronomy-related aspects help to turn PDO products into flagships for the region which leads to higher incomes from traditionally produced food. Thus, the stakeholders of the PDO landscape saw themselves as guardians of local heritage:

Q31: ‘The name of the ham is directed towards marketing – an egoistic motivation – because certification makes the production more visible. […] It creates a joint image of local identity, traditional landscapes, biodiversity, and local resources.’ (R14: producer from Elassona)

In turn, the traditional management practices were culturally more important in Germany, where the income from landscape tourism is just as important, or even more important than the income from agricultural production.

Q32: ‘The Allgäu lives from tourism, cheese dairies live from tourism […] tourism needs the traditional production process and the cheese dairies need tourism.’ (R8: producer from the Allgäu)

4. Discussion

This study investigated stakeholders’ perceptions of the relationship between PDO products and sustainable landscape management (SLM) using case studies from six extensive animal husbandry systems in the EU. We found that from stakeholders’ perspectives, the success and persistence of PDO products are largely influenced by two factors: landscape maintenance, and income opportunities. Five of the six identified phenomena included either the code ‘Landscape’ or the code ‘Income’ (cross-sectoral categories). We claim that phenomenon two (landscape-income) touches all of the SLM principles proposed by Scherr et al. (Citation2015), at least indirectly. Looking at the other five phenomena as well provides a more detailed picture. By indicating their numbers, we refer to relevant quotes from the interviews of which some are placed in Annex 4. Drawing on the principles of SLM, we propose three central findings:

The commercialization of PDO products puts stakeholders in a position to maintain landscape management practices that contribute to several landscape objectives at once (SLM principles one and three), such as biodiversity conservation (Q2; Q6), cultural values (Q31; Q32), touristic attractiveness (Q13 - Q15), and maintenance of aesthetically beautiful landscapes (Q4; Q12). Looking into those phenomena that include landscape management, environmental benefits, and the legacy of PDO production, it becomes clear that the current state of PDO management already fulfills the SLM principles one and three, obviously with minor regional differences.

The interviews revealed that centralized marketing agencies or network hubs enable a more integrated approach to landscape management (SLM principles two and five). This was prominently displayed in the cases of Extremadura and the Allgäu, where centralized marketing makes traditional landscape management economically more viable through diversification (Q14; Q26). This underlines how ‘distant connections’ (Meyfroidt et al., Citation2022) can support information flow from producers to consumers. The regional differences regarding successful collaborative management are described in the phenomena that feature culture, diversification, and governance.

Stakeholders from all case study areas criticized the poorly adapted policies and support measures (SLM principle four) which often are not suitable for multifunctional livestock systems (Q18; Q22; Q28), do not reward landscape management that produces multiple benefits (Q8; Q9; Q29), or collide with rules of nature conservation (Q24; Q25). Because income is related to policies in many ways, stakeholders have strong opinions and demands but only little control over the issues described in the governance-income phenomenon.

4.1. Which characteristics of PDO production systems contribute to sustainable landscape management?

We found that key stakeholders of PDO production relate environmental (Q1; Q5) and cultural values (Q33) to SLM. Aspects such as biodiversity conservation (Q2; Q6) and reduced wildfire risk (Silva et al., Citation2020), or the maintenance of aesthetic landscapes attractive for tourism (La Millán-Vazquez de Torre et al., Citation2017) were linked to the traditional (Q12) and less-intensive practices (Q11) which are promoted and supported through the PDO label. Those benefits assigned to low-input management practices like herding, grazing, and grassland production in turn led to mosaic-like, multifunctional landscapes. Structurally rich landscapes are often perceived as aesthetically valuable (Q4), where both domesticated animals and wildlife may contribute to economic diversification (Q3), mainly through tourism (Batista et al., Citation2017; Folgado-Fernández et al., Citation2019). Working towards multiple objectives simultaneously, as observed in the case study areas, aligns with SLM principle number three. Although SLM is the reason for the inherent sustainability of many agricultural systems from which PDO products emerge; PDO production can also be intensified to a point where overgrazing leads to a loss of traditional landscape elements.

In our case study regions, we found three ways of generating income from landscape management. There was income generation from the landscape product itself, making the characteristic landscape a production factor and using it as a marketing instrument (Q13). Farmers involved in related activities can be seen as part-time landscape conservationists. On the other hand, income can also be sourced from tourism (Q15; Q16) or subsidies for environmental conservation (Q9). For example, the well-maintained heathland areas around Lüneburg (northern Germany) are used as recreational sites and promoted as tourism destinations, while at the same time, herders can receive money for contractual nature conservation (Q18). The Portuguese ‘goats as firefighters’ program is another interesting example of compensating land managers for their provision of public services like fire prevention. In the landscapes related to our case studies, livestock turned out to be a powerful tool to combine SLM and a continuous and sustainable stream of income. In accordance with SLM principle number one, stakeholders must agree on the multiple objectives of landscape management.

We found evidence that local networks for geographically protected products are key for supporting the products and integrating them into regional branding strategies, which is in line with the more theoretical work of Jansujwicz et al. (Citation2021). The uptake of SLM approaches works best when various actors collaboratively decide on management practices, value chains, and regulations (Zinngrebe et al., Citation2020); thus, combining SLM principles number one and three. As observed particularly in Extremadura and the Allgäu, centralized marketing and brand-building for the entire region helps to integrate these functions and thus appears to be more promising than promoting single products (Q26). In general, the marketing for PDO products from the Mediterranean region seems to focus a little more on the socio-economic outcomes than the environmental ones, which is also supported by other studies (Cozzi et al., Citation2019; Ferrer-Pérez & Gil, Citation2019).

4.2. Which conditions enable PDO production stakeholders to harness the system’s sustainability potential?

Understanding PDO products as landscape products and acknowledging their importance within these complex systems makes them a key element for SLM (Turner et al., Citation2020). By the nature of their environmental and socio-economic embeddedness, geographical indications can help to change the view on food from being a commodity to food as a product of landscape management. Managing food landscapes for social-ecological conservation and human well-being can therefore be seen as a shift from producing commodities to managing commons (García-Martín et al., Citation2022). While some PDO products are economically very successful, most PDO-related agricultural systems are characterized by low-input management which mostly is a trade-off for income unless there is a compensation scheme (e.g. agro-environmental subsidies). In the case of subsidies or economic incentives for PDO production, which were demanded by many respondents (Q27 – Q29), governance bodies should ensure that such schemes are not environmentally harmful as underlined by SLM principle number two. As environmental policies require baselines and indicators (Asioli et al., Citation2020; Borrello et al., Citation2022), the sustainability of PDO products would benefit from clear environmental standards in this sense.

Another enabling condition we identified was a well-adapted incentive system. Because landscape management heavily depends on socio-economic considerations (Plieninger et al., Citation2015), the producers among our interviewees saw financial support measures as a natural part of their cash flow. They were aware of the additional ecosystem services that they are maintaining through their landscape management (Q2; Q5), and logically they want to be compensated for their service to society (Peterson et al., Citation2014). This is also in line with SLM principle number four. Among our respondents, we found the common perception that CAP payments are too focused on intensive monoculture (Q3) systems. They claimed that CAP payments do not reward the multiple societal values and environmental outputs that stem from PDO-related agricultural systems (Q28). The stakeholders’ statements align with research findings indicating that, despite expressing support for sustainability and multifunctionality, a significant portion of CAP funds are still allocated to payments rooted in the productivity discourse (Erjavec & Erjavec, Citation2015). Instead, CAP funds should be redirected toward management approaches that deliver multiple benefits at once through conserving multifunctional landscapes, including the biodiversity values and ecosystem services they provide.

Economic diversification in the investigated PDO production landscapes almost exclusively focused on tourism, which was managed in a particularly professional manner by networking agencies. For example, achieving touristic attractiveness based on a certain landscape is almost impossible for a single producer (Q16). It needs coordinated efforts by several institutions (Q13; Q26), which was also found in other studies (Parga-Dans et al., Citation2020; Tieskens et al., Citation2017) and is reflected in SLM principle number five. In the case study regions, we identified local networks and regional marketing agencies as useful actors and entry points for supportive measures. Promoting PDO products as a part of the landscape identity and cultural heritage paves the way for future strategies to support rural development and cultural sustainability in those landscapes.

5. Conclusion

PDO products are catalysts for positive social-ecological development of rural areas, but they can rarely be initiated or drive a positive trend on their own. Stakeholders of PDO production systems reported that PDO products are the main reasons for the continuation of extensive management in traditional landscapes and thereby help to generate various social-ecological benefits. The success and persistence of PDO products, however, are tightly linked to several conditions. Among the conditions necessary for successful PDO production systems are regional marketing and brand-building, integration with tourism, maintenance of regional value chains, the attractiveness of rural areas and related professions, as well as targeted support measures for all those elements. However, it needs further investigation of how landscape connectedness and regional characteristics of food systems influence the values attached to the PDO products, especially for other categories than dairy or meat products.

We conclude that wherever PDO products should continue to exist, income must either come from a certain food culture (e.g. Torta del Casar) or the attractiveness of sustainably managed landscapes (e.g. Diepholzer Moorschnucke). In the best case, both are combined in a balanced way (e.g. Allgäu cheese, Dehesa de Extremadura, or Lemnos cheese). From the interviews, we learned, that this combination of having a successful food product but also a diversified income through nature tourism, is best reached by local or regional marketing networks. Both, traditional landscape management and regional food culture seem to play a crucial role in the success of PDO marketing. While food culture is easier to communicate to distant places, the value of SLM can almost only be perceived when visiting the PDO products’ regions. From this finding, we distinguish two major development strategies for different types of PDO products, both of which can support underlying SLM:

i) PDO products with a unique and well-known food heritage are better equipped to transmit social-ecological values through the product itself. Thus, they are better suited for reaching a wider audience and serving geographically distant markets. It must be ensured that marketing success does not undermine environmental integrity.

ii) PDO products that draw their main value from representing a unique and iconic form of landscape management may be marketed more successfully within the region. They are likely to receive financial benefits from nature-based tourism integrated with the gastronomic experience in combination with compensation schemes for environmental services or nature protection.

For both options, supportive governance should try to stimulate PDO production systems in two ways. On the one hand, offering incentives or financial support as a reward for providing ecosystem services to the public can ensure SLM through PDO production. On the other hand, governance can support PDO production through beneficial regulations and cultural valorization of the products. To ensure context-sensitive implementation, measures should be administered at a regional or local level while responding and reporting to national and European targets. Above all, the support measures should align with the key principles of SLM and its multiple environmental and cultural objectives. While the cultural aspect is already part of the PDO legislation regarding production and landscape management, the environmental aspect could be added by introducing basic sustainability standards to the label. Those could be voluntary at first, and later become mandatory, or be the starting point for a sustainable regionality label. By doing so, the agenda to use geographical indications for a sustainable transformation of Europe’s agriculture – following the ‘Farm to Fork’ strategy – could be brought forward substantially.

Authorship statement

All authors had the idea for this article and designed the methodology. LF was responsible for creating the interview guideline, planning and administrating the interviews as well as the field assistants and translators, for data management, and for implementing the PTA method. YZ assisted in designing the interview guidelines, and with transcribing and analyzing the recorded interview material. LF was also responsible for writing the manuscript while receiving constant feedback from YZ, MB, and TP. All authors critically contributed to the draft and approved the final version for publication.

Ethical statement

We enabled the recipients to participate by informed consent in the following ways: (i) During the introduction, we described the objectives of the interview and clarified that the survey is part of a research project. (ii) We pointed out that participation in the interview is voluntary and that the analysis will be conducted anonymously. (iii) We left our contact information to address any arising questions or concerns of the participants.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (636.4 KB)Acknowledgments

Most importantly, we want to thank the stakeholders who shared their time, knowledge, and practical experiences during the interview process. Further, we are grateful for the help of our field assistants who conducted and translated interviews. Carla Nogueira supported the interview campaign in Portugal, while Danae Sfakianou and Dimitris Oikonomou carried out the interviews, and provided the translations for the Greek case studies. Regarding the final manuscript, we are thankful for the anonymous reviewers who helped with their critical but constructive feedback to make our arguments much clearer. Also, we would like to thank Brianne Altmann for her copy-editing, which gave the text its final linguistic and stylistic touches.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The interview guideline is available as supplementary material (Annex 1). The original interview responses cannot be made public due to privacy reasons. Instead, summarized interview results, aggregated for each study region, are presented in Annex 2. The coding frequencies needed for the phenomenon-centered text analysis – distinguished by stakeholder types and regions – can be found in Annex 3. Interview responses that illustrate the topic are collected in an anonymous format in Annex 4, also containing the quotes displayed under results.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/1747423X.2024.2326321

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allen, T., & Prosperi, P. (2016). Modeling sustainable food systems. Environmental Management, 57(5), 956–975. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-016-0664-8

- Angelstam, P., Munoz-Rojas, J., & Pinto-Correia, T. (2019). Landscape concepts and approaches foster learning about ecosystem services. Landscape Ecology, 34(7), 1445–1460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-019-00866-z

- Arfini, F.[F.], (2019). Eu food quality policy: Geographical indications. In L. Dries, W. Heijman, R. Jongeneel, K. Purnhagen, & J. Wesseler (Eds.), Palgrave advances in bioeconomy. EU bioeconomy economics and policies: Volume 2 (pp. 27–46). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28642-2_3

- Arfini, F.[Filippo]., Albisu, L.M., & Giacomini, C. (2011). Current situation and potential development of geographical indications in Europe. In B. Sylvander & E. Barham (Eds.), Labels of origin for food: Local development, global recognition (pp. 29–44). CABI. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781845933524.0029

- Arfini, F.[Filippo]., Antonioli, F., Donati, M., Gorton, M., Mancini, M.C., Tocco, B., & Veneziani, M. (2019). Conceptual framework. In F. Arfini & V. Bellassen (Eds.), Sustainability of European food quality schemes: Multi-performance, structure, and governance of PDO, PGI, and organic agri-food systems (pp. 3–21). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27508-2_1

- Asioli, D., Aschemann-Witzel, J., & Nayga, R.M. (2020). Sustainability-related food labels. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 12(1), 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-100518-094103

- Barjolle, D., & Sylvander, B. (1999). Some factors of success for origin labelled products in agri-food supply chains in Europe: Market, internal resources and institutions. EAAE. EAAE, Le Mans. https://doi.org/10.22004/AG.ECON.241033

- Batista, T., Mascarenhas, J.M.D., & Mendes, P. (2017). Montado’s ecosystem functions and services: The case study of Alentejo Central – Portugal. The Problems of Landscape Ecology, XLIV, 15–27. http://hdl.handle.net/10174/24409

- Belletti, G., & Marescotti, A. (2011). Origin products, geographical indications and rural development. In B. Sylvander & E. Barham (Eds.), Labels of origin for food: Local development, global recognition (pp. 75–91). CABI.

- Belletti, G., Marescotti, A., Sanz-Cañada, J., & Vakoufaris, H. (2015). Linking protection of geographical indications to the environment: Evidence from the European Union olive-oil sector. Land Use Policy, 48, 94–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.05.003

- Borrello, M., Cecchini, L., Vecchio, R., Caracciolo, F., Cembalo, L., & Torquati, B. (2022). Agricultural landscape certification as a market-driven tool to reward the provisioning of cultural ecosystem services. Ecological Economics, 193, 107286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107286

- Bouwma, I., Zinngrebe, Y., & Runhaar, H. (2019). Nature conservation and agriculture: Two EU policy domains that finally meet? In L. Dries, W. Heijman, R. Jongeneel, K. Purnhagen, & J. Wesseler (Eds.), Palgrave advances in bioeconomy. EU bioeconomy economics and Policies: Volume 2 (Vol. 56, pp. 153–175). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28642-2_9

- Brock, S. (2023). What is a food system? Exploring enactments of the food system multiple. Agriculture and Human Values, 40(3), 799–813. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-023-10457-z

- Bürgi, M., Ali, P., Chowdhury, A., Heinimann, A., Hett, C., Kienast, F., Mondal, M.K., Upreti, B.R., & Verburg, P.H. (2017). Integrated landscape approach: Closing the gap between theory and application. Sustainability, 9(8), 1371. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081371

- Cei, L., Stefani, G., & Defrancesco, E. (2021). How do local factors shape the regional adoption of geographical indications in Europe? Evidences from France, Italy and Spain. Food Policy, 105, 102170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2021.102170

- Clausen, A. (2012). The individually focused interview: Methodological quality without transcription of audio recordings. The Qualitative Report, 17(37), 1–17. ( Article). https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2012.1774

- Cozzi, E., Donati, M., Mancini, M.C., Guareschi, M., & Veneziani, M. (2019). PDO Parmigiano Reggiano Cheese in Italy. In F. Arfini & V. Bellassen (Eds.), Sustainability of European food quality schemes: Multi-performance, structure, and governance of PDO, PGI, and organic agri-food systems (pp. 427–449). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27508-2_22

- Dal Ferro, N., & Borin, M. (2017). Environment, agro-system and quality of food production in Italy. Italian Journal of Agronomy, 12(793), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.4081/ija.2017.793

- Erjavec, K., & Erjavec, E. (2015). ‘Greening the CAP’ – just a fashionable justification? A discourse analysis of the 2014–2020 CAP reform documents. Food Policy, 51, 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.12.006

- European Commission. (2019). A European Green Deal. https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en

- European Commission. (2020). A farm to fork strategy for a fair, healthy and environmentally-friendly food system. Brussels. European Commission. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0381

- European Council. (1992). Council Regulation (EEC) No 2081/92: Of 14 July 1992 on the Protection of Geographical Indications and Designations of Origin for Agricultural Products and Foodstuffs. Brussels. European Council. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:01992R2081-20040501&from=EN

- Ferrer-Pérez, H., & Gil, J.M. (2019). PGI Ternasco de Aragón Lamb in Spain. In F. Arfini & V. Bellassen (Eds.), Sustainability of European food quality schemes: Multi-performance, structure, and governance of PDO, PGI, and organic agri-food systems (pp. 355–376). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27508-2_19

- Flinzberger, L., Cebrián-Piqueras, M.A., Peppler-Lisbach, C., & Zinngrebe, Y. (2022). Why geographical indications can support sustainable development in European agri-food landscapes. Frontiers in Conservation Science, 2, 752377. Article. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcosc.2021.752377

- Flinzberger, L., Zinngrebe, Y., Bugalho, M.N.[.N.Miguel Nuno], & Plieninger, T. (2022). EU-wide mapping of ‘protected designations of origin’ food products (PDOs) reveals correlations with social-ecological landscape values. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 42(3). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-022-00778-4

- Folgado-Fernández, J.A., Campón-Cerro, A.M., & Hernández-Mogollón, J.M. (2019). Potential of olive oil tourism in promoting local quality food products: A case study of the region of Extremadura, Spain. Heliyon, 5(10), e02653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02653

- García‐Martín, M., Torralba, M., Quintas-Soriano, C., Kahl, J., & Plieninger, T. (2021). Linking food systems and landscape sustainability in the Mediterranean region. Landscape Ecology, 36(8), 2259–2275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-020-01168-5

- García-Martín, M., Huntsinger, L., Ibarrola-Rivas, M.J., Penker, M., D’Ambrosio, U., Dimopoulos, T., Fernández-Giménez, M.E., Kizos, T., Muñoz-Rojas, J., Saito, O., Zimmerer, K.S., Abson, D.J., Liu, J., Quintas-Soriano, C., Sørensen, I.H., Verburg, P.H., & Plieninger, T. (2022). Landscape products for sustainable agricultural landscapes. Nature Food, 3(10), 814–821. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-022-00612-w

- Jansujwicz, J.S., Calhoun, A.J.K., Bieluch, K.H., McGreavy, B., Silka, L., & Sponarski, C. (2021). Localism “reimagined”: Building a robust localist paradigm for overcoming emerging conservation challenges. Environmental Management, 67(1), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-020-01392-4

- Krikser, T., & Jahnke, B. (2021). Phenomena-centered Text Analysis (PTA): A new approach to foster the qualitative paradigm in text analysis. Quality & Quantity, 56(5), 3539–3554. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01277-6

- La Millán-Vazquez de Torre, M.G., Arjona-Fuentes, J.M., & Amador-Hidalgo, L. (2017). Olive oil tourism: Promoting rural development in Andalusia (Spain). Tourism Management Perspectives, 21, 100–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2016.12.003

- Lamine, C., Garçon, L., & Brunori, G. (2019). Territorial agrifood systems: A Franco-Italian contribution to the debates over alternative food networks in rural areas. Journal of Rural Studies, 68, 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.11.007

- Meyfroidt, P. (2016). Approaches and terminology for causal analysis in land systems science. Journal of Land Use Science, 11(5), 501–522. https://doi.org/10.1080/1747423X.2015.1117530

- Meyfroidt, P., Bremond, A.D., Ryan, C.M., Archer, E., Aspinall, R., Chhabra, A., Camara, G., Corbera, E., DeFries, R., Díaz, S., Dong, J., Ellis, E.C., Erb, K.H., Fisher, J.A., Garrett, R.D., Golubiewski, N.E., Grau, H.R., Grove, J.M., Haberl, H., & Ermgassen, E.K.H.J.Z. (2022). Ten facts about land systems for sustainability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 119(7). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2109217118

- Milano, M.Z., & Cazella, A.A. (2021). Environmental effects of geographical indications and their influential factors: A review of the empirical evidence. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability, 3, 100096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crsust.2021.100096

- Mupepele, A.‑C., Bruelheide, H., Brühl, C., Dauber, J., Fenske, M., Freibauer, A., Gerowitt, B., Krüß, A., Lakner, S., Plieninger, T., Potthast, T., Schlacke, S., Seppelt, R., Stützel, H., Weisser, W., Wägele, W., Böhning-Gaese, K., & Klein, A.M. (2021). Biodiversity in European agricultural landscapes: Transformative societal changes needed. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 36(12), 1067–1070. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2021.08.014

- O’Farrell, P.J., & Anderson, P.M.L. (2010). Sustainable multifunctional landscapes: A review to implementation. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 2(1–2), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2010.02.005

- Owen, L., Udall, D., Franklin, A., & Kneafsey, M. (2020). Place-based pathways to sustainability: Exploring alignment between geographical indications and the concept of agroecology territories in Wales. Sustainability, 12(12), 4890. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124890

- Parga-Dans, E., González, P.A., & Enríquez, R.O. (2020). The social value of heritage: Balancing the promotion-preservation relationship in the Altamira World heritage Site, Spain. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 18, 100499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100499

- Pe’er, G., Bonn, A., Bruelheide, H., Dieker, P., Eisenhauer, N., Feindt, P.H., Hagedorn, G., Hansjürgens, B., Herzon, I., Lomba, Â., Marquard, E., Moreira, F., Nitsch, H., Oppermann, R., Perino, A., Röder, N., Schleyer, C., Schindler, S., Wolf, C., & Lakner, S. (2020). Action needed for the EU common agricultural policy to address sustainability challenges. People & Nature, 2(2), 305–316. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10080

- Pe’er, G., Zinngrebe, Y., Moreira, F., Sirami, C., Schindler, S., Müller, R., Bontzorlos, V., Clough, D., Bezák, P., Bonn, A., Hansjürgens, B., Lomba, A., Möckel, S., Passoni, G., Schleyer, C., Schmidt, J., & Lakner, S. (2019). A greener path for the EU common agricultural policy. Science (New York, NY), 365(6452), 449–451. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax3146

- Peterson, J.M., Caldas, M.M., Bergtold, J.S., Sturm, B.S., Graves, R.W., Earnhart, D., Hanley, E.A., & Brown, J.C. (2014). Economic linkages to changing landscapes. Environmental Management, 53(1), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-013-0116-7

- Plieninger, T., Kizos, T., Bieling, C., Le Dû-Blayo, L., Budniok, M.A., Bürgi, M., Crumley, C.L., Girod, G., Howard, P., Kolen, J., Kuemmerle, T., Milcinski, G., Palang, H., Trommler, K., & Verburg, P.H. (2015, 2). Exploring ecosystem-change and society through a landscape lens: Recent progress in European landscape research. Ecology and Society, 20(2). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07443-200205

- Plieninger, T., Muñoz-Rojas, J., Buck, L.E., & Scherr, S.J.[Sara J.]. (2020). Agroforestry for sustainable landscape management. Sustainability Science, 15(5), 1255–1266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00836-4

- Raimondi, V., Curzi, D., Arfini, F.[Filippo], Olper, A., & Aghabeygi, M. (2018). Evaluating socio-economic impacts of PDO on rural areas. Italian Association of Agricultural and Applied Economics (AIEAA). https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.275648

- Schebesta, H., & Candel, J.J.L. (2020). Game-changing potential of the EU’s farm to fork strategy. Nature Food, 1(10), 586–588. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-020-00166-9

- Scherr, S.J.[S.J.]., Buck, L.[.]., Willemen, L., & Milder, J.C. (2015). Ecoagriculture: Integrated landscape management for people, food, and nature. In N.K. van Alfen (Ed.), Encyclopedia of agriculture and food systems (pp. 1–17). Academic Press, Elsevier Science & Technology; Credo Reference. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-52512-3.00029-2

- Silva, V., Catry, F.X., Fernandes, P.M., Rego, F.C., & Bugalho, M.N.[Miguel N]. (2020). Trade‐offs between fire hazard reduction and conservation in a natura 2000 shrub–grassland mosaic. Applied Vegetation Science, 23(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/avsc.12463

- Tanentzap, A.J., Lamb, A., Walker, S., & Farmer, A. (2015). Resolving conflicts between agriculture and the natural environment. PloS Biology, 13(9), e1002242. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002242

- Tieskens, K.F., Schulp, C.J., Levers, C., Lieskovský, J., Kuemmerle, T., Plieninger, T., & Verburg, P.H. (2017). Characterizing European cultural landscapes: Accounting for structure, management intensity and value of agricultural and forest landscapes. Land Use Policy, 62, 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.12.001

- Turner, B.L.[B.L.]., Meyfroidt, P., Kuemmerle, T., Müller, D., & Roy Chowdhury, R. (2020). Framing the search for a theory of land use. Journal of Land Use Science, 15(4), 489–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/1747423X.2020.1811792

- Vakoufaris, H., Belletti, G., Kizos, T., & Marescotti, A. (2014). Protected geographical indications and the landscape: Towards a conceptual framework. Council of Europe. Meeting of the Workshops for the implementation of the European Landscape Convention: ‘Sustainable Landscapes and Economy: on the inestimable natural and human value of the landscape’, Urgup.

- van Vliet, J., Groot, H.L.D., Rietveld, P., & Verburg, P.H. (2015). Manifestations and underlying drivers of agricultural land use change in Europe. Landscape and Urban Planning, 133, 24–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.09.001

- VERBI. (2020). MAXQDA 2020 Manual. https://www.maxqda.com/help-mx20/welcome

- VERBI – Software. (2010). MAXQDA (version 10) [computer software]. VERBI – Software. Consult. Sozialforschung. GmbH. https://www.maxqda.de/

- Wagemann, J., Tewes, C., & Raggatz, J. (2022). Wearing face masks impairs dyadic micro-activities in nonverbal social encounter: A mixed-methods first-person study on the sense of I and thou. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 983652. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.983652

- Zinngrebe, Y., Borasino, E., Chiputwa, B., Dobie, P., Garcia, E., Gassner, A., Kihumuro, P., Komarudin, H., Liswanti, N., Makui, P., and Plieninger, T. (2020). Agroforestry governance for operationalising the landscape approach: Connecting conservation and farming actors. Sustain Sci, 15, 1417–1434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00840-8