ABSTRACT

Worldwide, flood risk is on the rise. Simultaneously, the UNDRR fears that humanity’s risk perception is broken. Low-intensity, high-frequency extensive floods are cumulatively the most damaging phenomenon. However, risk perception in the context of extensive floods is widely under-researched. Indonesia is on the nexus of low-risk perceptions, extensive flood risk and poverty. Therefore, a socio-economically marginalised and frequently flooded urban kampong where residents appear to exhibit low levels of risk perception, serves as a case for this study. Data was gathered through five months of fieldwork in Pontianak, West-Kalimantan, consisting of participatory observations and semi-structured interviews. While studies often focus on subjective risk perception, this study includes the socio-cultural context, and aims to understand differentiated perspectives on extensive flood risk. Results show that extensive floods in Tambelan Sampit primarily lead to indirect losses. Furthermore, risk perception is strongly shaped by the extensive characteristics of floods and the socio-cultural context. While risk perception in the kampong is low, we propose that in this specific case the risk perception is desensitised rather than broken. Understanding risk perception as desensitised can add nuance to understandings of people’s experience of (extensive) disasters, explain their behaviour towards risk and potentially inform improved mitigation and adaptation policies.

Risk perception is a context specific phenomenon informed by a blend of individual understandings and socio-cultural factors.

Rather than considering risk perception as generally broken or biased, in the context of extensive disasters it is more accurate to characterise perception as ‘desensitized’.

Awareness, worry and preparedness, as three interconnected aspects of risk perception, can all become desensitised in ways that together contribute to marginalised people being more vulnerable to negative impacts of flooding.

Flood management requires appropriate attention to desensitised risk perceptions to effectively prioritise prevention and mitigation in extensive flood contexts.

Highlights

1. Introduction

Worldwide, the risk of floods is on the rise (Pörtner et al., Citation2022). At the same time, scholars and policy makers are concerned about what they view as growing public biases and misperceptions of the causes and potential consequences of climate change relative to scientific consensus on this topic (Lee et al., Citation2015; Luo & Zhao, Citation2021). Similarly, the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) claims that humanity faces a broken risk perception caused by attitudes of ‘optimism, underestimation and invincibility’(UNDRR, Citation2022a). In other words, people’s perception of risk does not align with current losses and predictions of future disaster risk. Such assessments of public risk perceptions are grounded in a positivist and technoscientific understanding of risk and risk management behaviour wherein any deviation from the one objective truth about risk (as determined by scientists and experts) must be reflective of a lack of comprehension or inadequate information (Van Voorst, Citation2014).

In this paper, we instead adopt a cultural risk perspective which views all interpretations of risk as normative and shaped by shared interpretive frameworks (Van Voorst, Citation2014). We argue that rather than starting from an assumption that local interpretations of risk are somehow broken, biased or irrational, it can be more productive to view all forms of risk perception as culturally produced and context-specific. Thus disagreement or contradiction is not a problem per se; on the contrary, difference can instead be a valuable indicator of a perceptual mismatch between the values and priorities of people who experience hazards and disasters and outside assessments of their vulnerability and perceptions of risk (Van Voorst, Citation2014). Disaster risk comes in many forms and takes place in diverse contexts, and peoples’ vulnerability considerably varies over time, as well as between and within communities (Thiault et al., Citation2018). Studies of risk perception should therefore take into account context-specific nuances including legacies of historical environmental injustices, future uncertainties introduced by global climate change, individual understandings and socio-cultural factors and the specificities of particular types of disasters.

In particular, the phenomenon of extensive disasters may challenge the technoscientific notion of local risk perception as broken, biased or irrational. As opposed to intensive disasters, which are acute and severe, extensive disasters are characterised by low-intensity high frequency events (Komendantova et al., Citation2014). Research has shown that extensive flood risk is the single most damaging phenomenon amongst all hazard types, the impacts of recurrent, small-scale floods lock vulnerable people further into poverty, and extensive floods are one of the most complex risks to reduce (Chavda et al., Citation2022; UNDRR, Citation2022a). Since the characteristics of extensive disasters are fundamentally different from intensive disasters, perceptions of extensive risk are also likely to deviate. However, extensive disasters are severely under-reported, often dubbed as silent disasters (IFRC, Citation2020), and better understanding is needed on risk perception in the context of extensive disasters.

Indonesia is a country on the nexus of relatively low levels of risk perception, (extensive) flood risk and poverty, while it is one of the most disaster-prone countries in the world (Mizutori & Guha-Sapir, Citation2020). First, according to data from the 2019 World Risk Poll on the website of The Lloyd's Register Foundation, Indonesian society has a generally low perception of risk and the country’s score on the Worry Index (indicating level of worry about a range of perceived risks) is low in relation to the Experience of Harm Index (actual experience of losses due to hazards). In comparison, South-Korea has a much lower score on the Harm Index, but nearly the exact same score on the Worry Index as Indonesia, while Mongolia suffers aproximately the same harm as Indonesia, but scores higher on the Worry Index. Based on this index, it appears that Indonesians tend to be less worried about disaster risk than residents of other countries, so arguably their level of risk perception may not be aligned with the reality of disaster risk they face.

Second, 76 million people in Indonesia live in high-risk flood zones with a 1% yearly chance of inundation up to 0.5 metres (Rentschler et al., Citation2021). Due to the climate crisis, Indonesia’s densely populated coastal cities are particularly vulnerable to sea level rise. In combination with changing weather patterns and widespread land subsidence these cities will face a significant increase of flood risk (Pörtner et al., Citation2022; Shaw et al., Citation2021).

Third, out of these 76 million Indonesians living in high risk flood zones, 40 million live in poverty (on less than $5.50 per day) and 2.6 million in extreme poverty (less than $1.90 per day) (Rentschler et al., Citation2021). Research has consistently shown that poverty excacerbates flood risk vulnerability (UNDDR 2022). As an emergent economy, Indonesia is rapidly urbanising, pushing human settlements into flood-prone areas where poverty coincides with flood exposure and risky building practices (Rentschler et al., Citation2022). Therefore, many Indonesian people are frequently exposed to extensive risk, but have limited means to improve their situations due to their socio-economic position.

The marginalised community of Tambelan Sampit serves as a case for this study. In this urban kampong (‘village’) (Octifanny & Norvyani, Citation2021), poverty coincides with extensive flood risk. Tambelan Sampit is the poorest area in the city of Pontianak (West-Kalimantan, on the Indonesian part of Borneo), with between 12.7% and 17.6% of the inhabitants living below the poverty line (World Bank, Citation2018). In East Pontianak, where Tambelan Sampit is located, a staggering 99% of the population live in high risk flood zones (Rentschler et al., Citation2021). While floods in Pontianak are currently considered manageable by many residents and the local government, they are expected to increase significantly in frequency and height by 2050, due to climate change, rapid urbanisation, land subsidence and waste management issues (World Bank, Citation2018).

The aim of this study is to understand how risk perception in Tambelan Sampit is shaped in a context of extensive floods. Previous studies of risk (and other environmental issues) in marginalised communities have been critiqued for portraying communities as internally homogenous (Van Voorst, Citation2016; Zulu et al., Citation2011). In response to this critique, disaster studies scholarship is increasingly shifting towards acknowledgement of diverse and intersectional experiences and perceptions taking into account differences in race, gender, income, age, sexuality, education and more (Olofsson et al., Citation2016; Zoll et al., Citation2023). Building on such critical perspectives, this study explicitly voices risk perceptions from a diverse group of respondents within the community. These objectives have led to the research question: What are the differentiated perspectives towards perceived extensive flood risk amongst inhabitants of Tambelan Sampit?

Subjective risk perception is the assessment of risk, mediated through the individual’s psychology and behaviour. Three inter-related factors constitute subjective risk perception: worry, awareness and preparedness (Raaijmakers et al., Citation2008). However, a purely subjective assessment of flood risk may be too narrow (Lechowska, Citation2018). Cultural Theory, as opposed to subjective risk perception, explains risk perception from within culture Douglas and Wildavsky (Citation1983). Boholm (Citation2003) has critiqued purely subjective or purely socio-cultural explanations of risk perception and argues for a holistic approach. In this study, therefore, we investigate how the socio-cultural context of Tambelan Sampit contributes to shaping subjective flood risk perception. Theoretically, we aim to nuance the commonly used subjective flood risk perception theory of Raaijmakers et al. (Citation2008), by including a socio-cultural perspective that is often overlooked in such studies (Lechowska, Citation2018).

Moreover, in this study we problematise technoscientific understandings of risk perception as broken, biased or irrational, for instance as suggested by the UNDRR. Instead, we propose an alternative context-specific view of the flood risk perception of people in Tambelan Sampit as desensitised by recurrent exposure to extensive floods and the specific socio-cultural context. We define desensitised as a condition of individuals and communities where overexposure to a phenomenon (in this case flooding) results in a decreased response to the phenomenon. Desensitisation happens in combination with other contextual factors enabling and constraining action such as socio-economic marginalisation and cultural or religious perspectives. Throughout this paper we will therefore show how the prevalence of low-intensity high frequency flooding has led this community (and governance actors) to be less likely to take action to prevent or mitigate flood risks, instead engaging in everyday practices of accommodation. In this sense, inaction in the face of growing risk may not be the result of misperception, biased perception or something being broken. Given the global prevalence of extensive flood risk, the concept of desensitised risk perception can be used to inform disaster risk policy-making and implementation that captures the local specificity of risk perception.

The remainder of the paper is divided into the following sections. First, we present the theoretical framework. Next, in the methods section we describe how the data for this research was gathered during five-months of ethnographic fieldwork in Tambelan Sampit. Then, we describe the context of Tambelan Sampit, extensive floods that occur there and the (in)direct losses experienced as a result. Based on the theoretical categories of worry, awareness and preparedness, we present the results and discuss them in relation to the proposed concept of desensitised risk perception. We end with a reflection on the importance of situated understandings of risk perception for future research and policy.

2. Theory

In studies on disasters, risk is often conceptualised as a mathematical outcome or statistical probability. The study of risk, however, is also well established in sociology and social anthropology (Alaszewski, Citation2015; Boholm, Citation2003; Faas & Barrios, Citation2015). Rational choice theory would be an apt tool for understanding people’s behaviour in terms of risk, if they would adhere to an objective conceptualisation of risk and utility maximisation. In reality, however, people do not always make rational choices concerning risk (Renn et al., Citation2000). Based on fieldwork in a Jakarta slum, Van Voorst (Citation2016) argues that people’s behaviour towards flood risk cannot be explained by the risk itself. The idea of subjective risk acknowledges that people’s perception of risk often does not match objective measurements and statistical probabilities presented by experts (Boholm, Citation2003; Lechowska, Citation2018).

Social scientists, therefore, try to understand subjective risk perception on the individual level, grounded in psychological and behavioural research. For example, in social anthropology, the cultural theory of risk (or Cultural Theory) attempts to explain people’s risk perception and behaviour as created from within culture (Douglas & Wildavsky, Citation1983). The meaning of risk is therefore seen as constructed through collectively shared representations and is culturally and historically embedded (Johnson & Covello, Citation2012; Johnson & Swedlow, Citation2021). Cultural Theory distances itself from the idea that people make rational choices based on maximisation of utility and that risk can be explained by understanding individual thoughts, intentions and strategies alone. Instead, in this approach, risk is considered as situated and context dependent (Boholm, Citation2003).

The cultural theory of risk, however, has been critiqued for its functionalist explanation and neglect of individual choices (see e.g. Boholm, Citation2003; Wilkinson, Citation2001). We follow Boholm’s (Citation2003) line of reasoning: risk is neither simply objective nor simply culturally/subjectively constructed. Boholm posits a theoretical middle ground that takes a nuanced, realist position towards risk. In light of this, we aim to contribute to existing flood risk perception theory by including a socio-cultural perspective to create a more holistic understanding of risk.

Effective flood management requires understanding how society perceives flood risk (Bradford et al., Citation2002). Namely, if a society does not perceive floods as a risk, the incentive for mitigation or adaptation is low. Raaijmakers et al.’s (Citation2008) often-used definition of subjective flood risk perception consists of three factors: awareness, worry and preparedness. Awareness is the knowledge or consciousness of an individual or group of individuals, in terms of flood risk. Worry is associated with the degree of concern, fear or dread experienced by people at risk of floods. Preparedness entails peoples’ pre-flood readiness, capability of coping with a flood during an event and capacity for post-flood recovery. In this theory, awareness of flood risk may lead to worry and as a consequence to higher preparedness.

However, such a linear relationship may not exist in every case (Lechowska, Citation2018). An extensive review of quantitative papers on subjective flood risk perception by Lechowska (Citation2018) demonstrates that the factors worry, awareness and preparedness are consistently related to the notion of flood risk perception. However, the overall outcome of the review shows a heterogeneous picture, with often contradictory conclusions between different studies. Lechowska argues that these contradictions might in part be explained by the socio-cultural contexts of the included studies. Adopting a holistic approach towards flood risk perception, by investigating how a socio-cultural context shapes worry, awareness and preparedness, nuances the theory of Raaijmakers et al. (Citation2008). The research presented in this paper is, therefore, simultaneously deductive, by testing existing theory in the field, as well as inductive, by untangling the situatedness of risk that is embedded in a socio-cultural context.

3. Methodological approach

The aim of this study was to test an existing flood risk perception theory with qualitative methods, remaining open and flexible towards unexpected, emergent data. This study, therefore, is simultaneously exploratory and descriptive and, as such, abductive in nature (Alvesson & Sköldberg, Citation2017). The methods described below complied with the ethical clearance for qualitative ethnographic research by the ethical commission of Radboud University, Nijmegen. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Interviews lasted for a maximum of one hour to minimise the burden of participation, and no interviews were scheduled during prayer times or holiday periods.

Understanding differentiated perspectives on flood risk perception requires a comprehensive qualitative research approach. The ethnographic fieldwork, conducted by the first author, took place from December 2022 until April 2023, during which time he lived and worked in Tambelan Sampit. The main method was participatory observation, supplemented by semi-structured interviews (n = 28), key informant interviews (n = 8) (e.g. doctors, teachers, government officials), informal interviews, small talk and transect walks to map the surroundings. The first author experienced multiple extensive flood events during his time in Tambelan Sampit, contributing to a deeper understanding of the range of challenges posed by household inundation. Relationships were established through key contacts and by spending time with community members in informal ways, including participation in cultural events and ceremonies such as weddings, prayers and burials. Interviews were conducted with people with whom the first author had already established relationships and with the assistance of a certified translator who is a well-know and trusted community member. During interviews, flood risk maps with current and future predictions of flooding in Pontianak were used as a means of elicitation. Before sharing predictive flood risk maps with participants they were asked for consent again, giving them an opportunity to decline to view potentially upsetting information.

To diversify the sample we included 13 male and 14 female respondents ranging in age from 20 to 66. This comprised both residents living on the riverfront and further inland. Additionally, a wealth ranking was used to establish emic wealth categories based on local indicators and criteria of wealth and wellbeing, thereby establishing three wealth categories among semi-structured interviewees: high (n = 6), middle (n = 11) and low (n = 8). The wealth category of two respondents was not determined. The sample was diversified by including people from these three wealth categories, as well as an equal distribution between men (n = 13) and women (n = 14) and between ages (ranging from 20–66). Furthermore, we included respondents living directly on the riverside (n = 12) and living further in land (n = 15). The purpose of this diversification was to find similarities or differences between different sub-groups of respondents and to have a representative sample.

Data from the semi-structured interviews, as well as fieldnotes, were at first roughly coded to explore patterns in the data. Sections were then labelled, analysed and possibly re-labelled, according to a qualitative, thematic analysis (Evers, Citation2015; Spradley, Citation1980; Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990). Emergent categories were interpreted and complemented by a review on flood risk perception literature.

4. Context description: extensive floods and indirect losses in an urban kampong

Before demonstrating and discussing the concept of desensitised risk perception in the results, the section below describes the socio-economically marginalised context of Tambelan Sampit and the extensive floods and indirect losses experienced by the community. Located precisely on the equator, Pontianak is the provincial capital of West-Kalimantan, on the island of Borneo. With an average of 1.5 metres above sea-level, the city is built around the confluence of the Kapuas River and its main tributary, the Landak River, before it empties out into the Java Sea 22 kilometres downstream. Tambelan Sampit is located in the Eastern part of the city, directly on the Kapuas riverside, just before the confluence.

According to The Mayor’s Decree of Pontianak (Number 1063.1 / D-PRKP / Year 2020), Tambelan Sampit is considered daerah kumuh: a ‘slum’. However, although the area could fit some of criteria of slums (Bolay et al., Citation2016; Rocco & van Ballegooijen, Citation2019), use of the word slum reproduces negative stereotypes around poor people and confuses a physical problem with the inhabitants’ characteristics (Gilbert, Citation2007). Therefore, we refer to Tambelan Sampit as urban kampong (‘village’) (Nas et al., Citation2008; Octifanny & Norvyani, Citation2021). Like other Malay kampong, Tambelan Sampit is a village-style neighbourhood, characterised by narrow roads, irregular structures, limited public services and inadequate housing. Tambelan Sampit hosts a mixed population of low– and middle-income inhabitants, with different land tenurial statuses (i.e. formal, informal, semi-formal) and strong social network and kinship ties (Octifanny & Norvyani, Citation2021).

According to an official census of Tambelan Sampit in 2022, the population was 7,686 inhabitants over 2,271 households, mainly consisting of ethnic Malay, with small numbers of ethnic Dayak, Bugis, Javanese and Madurese immigrants. Islam is the dominant religion in the kampong. Most people work freelance or in the private sector, are self-employed or take care of the household. However, like in other urban kampong, many people are involved in the informal economy (Octifanny & Norvyani, Citation2021), generating unstable income outside the legal framework. This is one reason inhabitants are poor in comparison to other sub-districts of Pontianak.

Flooding in Tambelan Sampit is primarily caused by the tides of the Java Sea pushing water upstream into the Kapuas River, often in combination with heavy rainfall or storm surges (Sampurno et al., Citation2022). A particular problem aggravating floods in Pontianak are blocked drainage and sewage systems due to excessive solid waste. Flood risk in Tambelan Sampit will increase significantly in the coming decades, especially as a result of the climate crisis, rapid urbanisation and ongoing land subsidence (World Bank, Citation2018).

Floods in Tambelan Sampit are typically short-lived, with low levels of inundation (World Bank, Citation2018). However, flood events are frequent and can sometimes occur several days in a row. Water from the Kapuas flows through the neighbourhood with each tide, but other factors (e.g. springtide, rainfall) determine whether canals in the area overflow. Floods occur mostly during the rainy season, with a peak from December to January. Over the course of fieldwork for this paper, Tambelan Sampit flooded several times, with one exceptional event on 23 December 2022 that was, according to several respondents, the worst flood in recent history. These low-intensity, high-frequency and short-lived events make flooding in Tambelan Sampit a prime example of extensive disasters (UNDRR 2022).

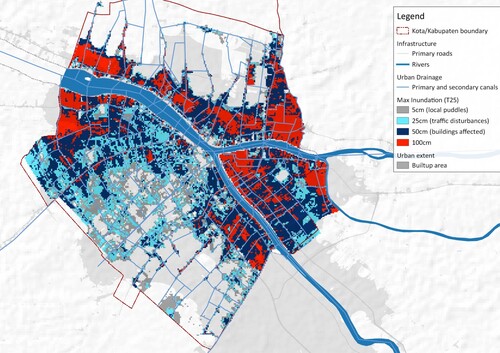

Worldwide, floods cause damage to assets, injury or mortality, physical and mental health risks and disruption of livelihoods (Few, Citation2003; Penning-Rowsell et al., Citation2022; Wisner et al., Citation2014). In Pontianak, the annual damage due to flooding is estimated around $57.1 million and is expected to rise to $248.5 million in 2050 (World Bank, Citation2018; ). However, residents of Tambelan Sampit, like other urban kampong, live in inadequate dwellings, often made from poor quality materials (Octifanny & Norvyani, Citation2021). The total costs of damage inflicted on their assets is negligible within city-wide, quantified measurements of flood risk, making material impacts of extensive floods in Tambelan Sampit ‘invisible’ (IFRC, Citation2020). Nonetheless, frequent exposure to extensive floods in Tambelan Sampit causes damage to assets and impacts the material wellbeing of already economically marginalised citizens. Affected inhabitants become financially burdened, as is exemplified by the story of a low-income old widow:

Everything needs to be changed. Especially the floor and foundations underneath the house. It’s impacted by floods, so it rots over time. There is a plan to change the floor and sticks [foundation] after Idul-Fitri [holiday of breaking the Islamic fast]. I saved money from my BLT [government support] and after, I will buy materials to renovate. Because my little brother gives us money for daily food, I could save some for the renovation. If I change it this time, it will be the third time I have to change the floor. (4 March 2023)

Figure 1. Projected flood impacts in Pontianak in 2055. This is for a scenario with 1/25 yr-1 rainfall and normal peak river discharge (1/2 yr-1), high spring tide conditions and in which combined sea levels rise and land subsidence (relative sea level rise) is 1.0 m compared to 2020 levels (World Bank, Citation2020; included with permission).

Flood risk in Tambelan Sampit is heterogenous and unevenly distributed between inhabitants. This means that respondents from the high-wealth category, able to afford houses that are either more elevated or made of durable materials, indicated no direct losses due to floods.

Although direct losses do occur in Tambelan Sampit, through interviews it became clear that indirect losses take a more significant toll on the community. Indirect losses, as opposed to direct losses, are difficult to quantify and refer to the subsequent or secondary results of a disaster (Komendantova et al., Citation2014). Extensive floods in Tambelan Sampit primarily lead to indirect losses by disrupting lives and livelihoods, affecting wellbeing and polluting the environment.

Floods also disrupt the daily activities of respondents. Especially when roads are also flooded in the rest of Pontianak, it is not possible for people to commute to work outside of the kampong. Since most respondents work in the informal sector and live on daily payments (Octifanny & Norvyani, Citation2021), their immobility impacts the household’s income. Moreover, respondents experience a loss of time and energy spent on cleaning and minor repairs, which unequally burdens women.

Floods are infamous for their secondary health impacts, including outbreaks of water– and vector-borne diseases caused by standing water (Penning-Rowsell et al., Citation2022). Fortunately, tidal flood water in Tambelan Sampit always quickly subsides, but the water in and around the neighbourhood that residents are inevitably exposed to is severely polluted. Moreover, septic tanks overflow during floods, which leads to sanitary wastewater mixing with environmental water. This is very problematic, since many low-income inhabitants and those living directly on the riverside do not have access to tap water and are forced to make use of potentially contaminated canals for their sanitary needs. The community health clinic of Tambelan Sampit reports a rise in potentially water-related diseases such as diarrhoea, skin infections and typhoid fever during the peak of the rainy season when most floods occur. According to the clinic, high levels of stunting among children in Tambelan Sampit (15% of children) might in part be explained due to frequent, water-related sickness. Interestingly, however, most respondents said that floods do not affect their health, since they are supposedly immune to the water in their surroundings after a lifetime of exposure.

In addition, Tambelan Sampit is severely polluted with excess solid waste. This is the result of city-wide, structural waste-management issues. Floods further pollute the environment of Tambelan Sampit, as the retreating water leaves behind trash and dirty puddles. A young mother mentioned that water is the main concern of her family and floods aggravate the situation because ‘[t]he water is dirty. It is hard to bathe the child if the water from the flood infects our pool [clean water source]. It will give the baby diarrhoea’ (9 March 2023).

Many respondents initially said that floods do not cause significant problems in their lives. However, on closer examination it becomes clear that respondents do suffer indirect losses, as demonstrated in the examples above. The characteristics of the extensive flooding and resulting indirect losses contribute to, as we argue in the following section, desensitised risk perception for respondents in Tambelan Sampit.

5. From broken – to desensitised risk perceptions

Subjective flood risk perception consists of awareness, worry and preparedness (Raaijmakers et al., Citation2008). Due to the context of extensive floods and indirect losses, however, the theory of Raaijmakers, Krywkow, and van der Veen does not neatly fit the reality of people in Tambelan Sampit. Furthermore, the socio-cultural context of Tambelan Sampit nuances the subjective flood risk perception of respondents. More specifically, in the three sections that follow, we argue that residents’ risk perception is desensitised, rather than broken or biased. In each sub-section we present the findings regarding worry, awareness, and preparedness in Tambelan Sampit, in combination with a discussion of how each of the three aspects are simultaneously desensitised by the chronic and low-intensity flooding common in this area.

5.1 Desensitised awareness

When people know something about the flood risk they are exposed to, this is defined as flood risk awareness (Raaijmakers et al., Citation2008). Direct experiences of and information sharing about floods usually lead to flood risk awareness, which in turn informs worry (Lechowska, Citation2018). However, respondent’s socio-culturally shaped ideas and biases about the causes and future projections of floods have, as we argue, desensitised flood risk awareness.

Low flood risk awareness is related to having limited knowledge about the causes of floods (Raaijmakers et al., Citation2008). Respondents described a number of ideas about the causes of floods in Tambelan Sampit. First, sometimes they assigned a natural cause to the phenomenon, explaining how air pasang in combination with rain or strong winds can cause flooding. Second, at other times respondents had a religious interpretation, wherein Allah creates floods either as hikmah (‘lesson’), azab (‘divine retribution’) or rejeki (‘gift from God’). Some respondents combined natural and religious explanations, such as this young nurse:

All of life is set by God. All of it is bound to happen. It is God who makes the plan. God makes air pasang, but we live in a place that is affected by this. So, people living here will be affected. Everywhere there is some kind of risk. Here it is floods. (3 March 2023)

Third, the majority of respondents ascribed two human causes to floods, both, strictly speaking, not aligned with scientific evidence. First, deforestation upstream, for the purpose of palm oil plantations (sawit), was often mentioned. However, excess runoff and resulting increases in river discharge do not necessarily contribute to floods in Pontianak (Sampurno et al., Citation2022). Second, the main perpetrator, according to most respondents, is excess solid waste (sampa) that blocks the drainage systems of the city (). Although it is true that this problem aggravates flood risk in Pontianak (World Bank, Citation2018), technically this is not the direct cause of flooding. Only two wealthy, highly educated, respondents mentioned climate change, the actual main driver behind Pontianak’s increased future flood risk (Sampurno et al., Citation2023). This shows that ideas about two contemporary, socio-ecological phenomena, sawit (Li, Citation2015; Merten et al., Citation2020) and sampa (Schlehe & Yulianto, Citation2020), that have drastically altered the landscape and social lives of people in Indonesia, in return also inform ideas about the causes of floods. Lastly, some respondents combined human causes with religious interpretations, such as this middle-aged man:

I take it as hikmah [lesson]. Because all things come from God. We don’t have to do something about it. It is what it is. It’s what we did to the world. […] Maybe it’s because of what we did to the environment. (28 March 2023)

Figure 2. Waste accumulation in the canals of Tambelan Sampit which may contribute to flood risk elsewhere in Pontianak but alongside the river is not a direct cause of tidal flood inundation. Photo Credit: Reza Fahlepi.

When discussing future flood risk, most respondents were not aware of the predicted scenarios for Pontianak (see e.g. World Bank, Citation2018) and, like people often do, expected that floods will remain the same in the next decades (Lechowska, Citation2018). An elderly widow commented on this:

Now I got to the age of my mother, the situation [of floods] is the same. When my daughter will be my age, the situation will still be the same. Of course, I don’t know what God will do. […] I don’t really pay attention to the future, that’s the way I live. What I have today is today. (6 March 2023)

This [flood risk map] is a human prediction. If Allah has a different will, if he doesn’t want it, it will not happen. Human predictions are sometimes right, sometimes wrong. […] I might anticipate if it really happens. But for now, I have no preparation, because I don’t believe it will happen (7 March 2023)

5.2 Desensitised worry

Awareness of (future) flood risk leads to worry (Raaijmakers et al., Citation2008). Therefore, desensitised flood risk awareness, as described in the previous section, inevitably leads to decreased worry among respondents. Furthermore, the characteristics of extensive floods and resulting indirect losses are not necessarily considered worrisome by respondents. At the same time, the socio-cultural context of Tambelan Sampit decreases worry, or directs worrying towards specific aspects of floods. In other words, while respondents do experience losses due to floods and are aware of flood risk, their sense of worry is also desensitised.

Respondents argued that flood risk is not worrisome, based on the extensive characteristics of floods in Tambelan Sampit. The Indonesian word for flood, which connotes disaster risk, is banjir (Merten et al., Citation2021). Most respondents in Tambelan Sampit, however, would refer to floods as air pasang (high tide) or acap (a Malay variation of the Indonesian word genangan or ‘puddle’). By referring to air pasang, respondents conceptualise floods as natural, inevitable events, while these floods are at least partially human induced (e.g. due to climate change or rapid urbanisation). For example, a middle-aged father described floods as follows:

The cycle happens every year. But it was never high. Maybe up to the foot only. So, people here don’t want to call it banjir. It is air pasang. If the water stays for a longer time, it’s a different case. Actually, if you call it banjir, it means the water will stay. With air pasang, the water goes down. In case a flood would be one meter and stays one or two days, it will have an impact. Air pasang only has a minimal effect. (22 March 2023)

How people define floods or why people consider their flood risk as acceptable and subordinate to others’, is in part socio-culturally constructed. For example, shared representations of floods as acceptable in Tambelan Sampit are often produced through religious interpretations. The predominantly Muslim population of the community and especially the elderly value the religious concept of pasrah (lit. ‘surrender’), wherein the believer has faith in God’s plan (Nygard, Citation1996). The Islamic idea of pre-destination (qadar in Arabic) is associated with pasrah and leads to a certain degree of flood risk acceptance and ultimately desensitises worrying. As a consequence, some respondents expressed they did not feel the need to act on flood risk (see e.g. also Schmuck, Citation2000), such as this elderly woman:

There is not really anything you can do. If it [flood] comes, just let it come. If people tell me the predictions for tomorrow are higher, I try not to let those words worry me. If God decides there is a banjir, there is. (2 February 2023)

Figure 3. Children in Pontianak swimming and playing in (flood) water along the Kapuas River. Photo Credit: Reza Fahlepi.

A collectively shared expression amongst respondents was banjir sudah biasa: ‘floods are common’ or ‘we are used to floods’ (see also Van Voorst, Citation2016). Inhabitants of Tambelan Sampit are so frequently exposed to floods that instead of considering them a problem, they accept floods as a fact of life. A famous cake baker in the area said:

[…] people get used to it. The first and second month [of the year] it always happens. We are used to it [sudah biasa] since we were kids. […] it always happens like that; we can’t avoid it. We are “regular customers” of banjir. (17 March 2023)

Except for a few, most respondents believed that the height and frequency of floods have always been the same in their lifetime and will remain constant in the future. This is common amongst people living with flood risk (Lechowska, Citation2018). However, according to scientific data, the occurrence and depth of inundation of floods has been slowly increasing (World Bank, Citation2018). Since respondents have always accepted these level of floods, the slow increase is not dramatic enough to shift that perspective. Respondents are desensitised to slow changes in their environment. Their perception of normal floods has moved and will likely move along with the rising water.

As a result, respondents do not exhibit general worry, fear or dread concerning floods. Instead, they are worried about specific aspects of floods. For instance, some respondents (especially young parents) were somewhat worried about risk from potential changes in the characteristics of floods such as increased depth of inundation, frequency or duration. In such a potential scenario, respondents mostly worried about their physical assets and the safety of their relatives. Although the height and onset of (future) floods in Tambelan Sampit is not considered an immediate threat to human safety, they could be dangerous to children, as this young mother explains:

Sometimes I worry for my children, because they like to play with the [flood] water. I worry the flow will take them. That happens sometimes, I heard it in the news. So, I tell them not to play to far away and I teach my children how to swim. If you live here, you have to be able to swim. (17 March 2023)

People also worry about things they have not experienced, for example, virtually all respondents mentioned a fear of snakes entering their house during floods. However, none had actually experienced any harm caused by such an encounter.

5.3 Desensitised preparedness

Preparedness is the outcome of the factors worry and awareness; combined they form flood risk perception. In the previous sections, we have demonstrated how the context of extensive flood risk, indirect losses and the socio-cultural context of Tambelan Sampit desensitises awareness and worry for residents. As a result, we argue, preparedness is also desensitised and arguably inadequate considering predictions of future flood risk in Pontianak (World Bank, Citation2018).

Preparedness consists of pre-flood anticipation and the capacity to cope with and recover after floods. However, the city of Pontianak lacks proper emergency response and has limited or virtually absent early warning and risk reduction strategies (World Bank, Citation2018). Specific policies aimed at the most vulnerable, such as the socio-economically marginalised inhabitants of Tambelan Sampit, are non-existent. An employee of the Indonesian Board for Disaster Management (BNPB) justified this absence in terms of the desensitised perception of residents, echoing the words of residents: because floods are supposedly part of riverside life and people living there are accustomed to them, there is no need to intervene. This demonstrates how the process of desensitisation reaches beyond Tambelan Sampit and even makes its way into the level of disaster risk management in Pontianak. Thus residents are left mainly to their own devices in dealing with floods.

However, the national meteorological institute (BMKG) in Pontianak publishes information about tides and warns citizens of potential floods on their website, through social media and via WhatsApp messages. Official early warnings, however, do not always translate into response (Perera et al., Citation2020). In fact, many respondents are biased against the warnings of the BMKG, as this former government representative as head of a neighbourhood association highlighted:

I say they [BMKG] are lying. If a banjir happens, it is because Allah wants it. One time, the BMKG warned us, we got ready, but nothing happened. […] there is no proof that the banjir will happen when the BMKG predicts it. (16 February 2023)

Since the awareness and worry of respondents is desensitised, it is not strange they do not take heed of early warnings, because individuals often think that floods will resemble past experiences (Perera et al., Citation2019). Respondents in Tambelan Sampit had their own ways of estimating risk flood. An older female respondent, known in her community as a ‘flood-expert’, explained:

I measure the water by looking at the stairs [across the canal]. If there is acap [puddle] there, I will soon have banjir in my house. […] No one gives information. I just know it myself. When the [flood] period comes, I look at the water more frequently. I also look before I go to sleep. If it worries me, I will prepare. (4 April 2023)

Concerning our belongings, we need to put them somewhere else. […] First, we take care of the carpet, the chairs we put on the terrace. We sleep on the floor, so we need to move the bed. We put the refrigerator on a small table. […]. Luckily, we don’t have many belongings. (23 March 2023)

Some of the respondent’s belongings, such as electronics, are permanently raised from the ground, while other belongings are stored in high places during the flood season and are only taken down after.

After belongings are saved, respondents said they cope with floods in a number of ways. Young parents made sure that their children are safe, by instructing them to stay close to their homes or sometimes by giving them rubber armbands. Women said they are able to flexibly adjust their schedules to continue performing their daily activities during a flood. A woman who works informally as a laundress, for example, said:

I will do the laundry first [before a flood]. If the banjir happens early, I will pause the activities, then continue afterwards. Sometimes the flood happens during laundry, you cannot know for sure. When that happens, I just cook. If the water withdraws, I continue work. I can adjust. (2 February 2023)

When it [flood] happens badly, people sometimes do azan [prayer call]. Normally, when there is azan, it finishes with ikamah [final prayer call]. So, when there is a flood and people do ikamah, it’s like the disaster will end. (25 March 2023)

Most respondents, however, are left with nothing but to wait for the water to withdraw. Then, especially for women, the cleaning starts.

For most respondents, the descriptions above reflect the cycle of pre-flood anticipation, coping with and recovering from floods (Raaijmakers et al., Citation2008), which can sometimes repeat for several days in a row during the rainy season. While the current flood preparedness may be adequate for some respondents, it is questionable whether they will remain sufficient in the near future.

Since awareness and worry of future flood risk is desensitised amongst respondents, long-term flood risk anticipation was not considered a priority, and flood preparedness was primarily geared towards short-term solutions. In fact, elevation of houses was the only solution that respondents proposed in response to future flood risk. Rumah panggung (lit. ‘stage houses’) are traditional Malay dwellings on stilts, historically inhabited to keep water and animals out of living spaces (Boomgaard Citation2007). Nowadays, most inhabitants of Tambelan Sampit live in more modern, so-called hanging houses, slightly raised above the surface, or in concrete houses directly on the ground. Stilt houses are a contentious issue. The local government has yet to come forth in preserving the few traditional Malay stilt houses still present in the area and the traditional building material, belian (Bornean ironwood), is now legally restricted. Maintenance of stilt houses is very expensive and for most respondents in Tambelan Sampit it is simply unaffordable to elevate one’s house. Still, in arguing for the re-introduction of rumah panggung as long-term flood risk anticipation, respondents resorted to their cultural heritage as a strategy for risk reduction; an example of how the Malay socio-cultural context informs preparedness.

6. Discussion

As mentioned in the introduction, we define desensitised risk perception as a condition wherein overexposure to a hazard leads to decreased action to prevent, cope with, or respond to that hazard. Given that extensive disasters are frequent, low-intensity disasters, often recurring over long periods of time, extensive flooding presents a suitable case to examine the impact of overexposure on the three components of subjective flood risk perception presented by Raaijmakers et al. (Citation2008): worry, awareness and preparedness. In particular, the overexposure caused by frequent flooding is accompanied by indirect impacts and a mismatch between current experiences and predicted future scenarios which feel either distant or disconnected from fairly consistent past experiences. The result is a shift in how risk perception functions (summarised in ). Instead of direct experience with floods leading to increased awareness and worry, residents seem to find the recurring nature of floods, indirect impacts, and the fact that they have – thus far – been able to continue their lives without severe consequences, justification for continued inaction. Therefore, while Raaijmakers et al. (Citation2008) posit that direct experience will lead to an increase in awareness, worry and preparedness, overexposure can in fact result in the opposite outcome.

Table 1. Summary of flood risk perception as theorised by Raaijmakers et. al (2008) and updated to reflect findings about desensitisation and extensive flood risk.

Awareness, as we have applied it in this paper, encompasses knowledge of the causes and consequences of a flood, along with the likelihood of a flood occurring. Desensitisation in the case of Tambelan Sampit and awareness of recurrent tidal flooding takes several forms. First, awareness of the direct causes of floods seems to be limited. Residents attribute flood risk primarily to natural causes and God’s plan, while sometimes acknowledging the potential role of solid waste management or upstream land use changes. Viewing floods in this way, as either natural or predestined, can discourage preventative action for something that is inherently unavoidable. Such a misunderstanding of flood dynamics can also be problematic for selecting effective flood risk reduction strategies. For instance, if solid waste management is seen as a cause of flooding by residents they may view cleaning waste from canals as a flood risk reduction strategy. However, in their specific neighbourhood the direct impacts of floods are not directly linked to dynamics of tidal flooding. Cleaning solid waste from the environment would potentially reduce indirect impacts from standing water, but not directly reduce the risk of flooding. Second, information sharing, for example in the form of early warning systems and alerts, either does not reach exposed households in time, or residents no longer trust the system based on prior experience and ideas about the motivations of the organisations providing information. Desensitisation in this case is therefore linked to both overexposure and past experiences that decrease awareness and action.

Increased awareness of flood risk could theoretically lead to higher levels of worry. Thus it is not surprising that in a context of low levels of awareness of flood risk in Tambelan Sampit, worry, including concern, fear, and dread of a flood occurring, also appears to be quite low. Residents and government actors agree that the residents of Tambelan Sampit are ‘used to’ flooding as a part of their riverfront lives and livelihoods, and that the level of risk remains acceptable. While this may be adequate currently, predictions of a changing climate and rising sea levels for Pontianak indicate that a low awareness of future risk and the resulting lack of preparedness at household and community levels may make Tambelan Sampit highly vulnerable to direct and indirect flood impacts in coming years. However, the still relatively slow rate of change has further contributed to desensitisation of residents, as they perceive that levels of flooding have been basically consistent throughout their lives and will likely continue in a similar pattern. The apologue of the boiling frog is quite fitting here: as soon as people realise floods are becoming a serious problem, it will be too late.

Worry about flood impacts, when it is present, is typically confined to specific aspects such as safety of children, keeping important belongings dry or cleanliness. Responses are targeted accordingly towards preventing children from being washed away in moving water, moving household items to higher locations, and cleaning thoroughly after waters recede. However, floods in Tambelan Sampit primarily lead to indirect losses, which are difficult to quantify and sometimes remain invisible (Komendantova et al., Citation2014). These indirect losses were not explicitly connected to worry about floods or to preventative actions. Systematic anticipation and reduction of flood risk and targeted policies and plans to support the most vulnerable are limited or absent from Pontianak, possibly reflecting a widespread desensitisation towards extensive flood risk.

7. Conclusion

According to the UNDRR (Citation2022b), humanity’s broken risk perception is set to reverse global development as the impact of disasters is increasing worldwide. However, this paper has shown that homogenising risk perception in this way is too straightforward, when disaster risk, contexts and vulnerabilities are so diverse. Furthermore, extensive, ‘silent’ (IFRC, Citation2020) disasters challenge the notion of broken risk perception, and the socio-cultural context is often overlooked in flood risk perception research. Therefore our findings align with existing studies which find that engaging with the broader context of flood risk perception can be a way improve understanding and effective communication with marginalised and vulnerable populations (Adelekan & Asiyanbi, Citation2016).

Tambelan Sampit, a frequently flooded, socio-economically marginalised community in Indonesia was taken as a case for this study. Through ethnographic research, we have shown how, on the one hand, the characteristics of extensive disasters shape risk perception and contribute to a broad desensitisation towards flood risk. On the other hand, a holistic approach to risk perception, including the socio-cultural context of Tambelan Sampit, nuances understanding of subjective flood risk perception of respondents. Based on the results, we conclude that flood risk perception in Tambelan Sampit is desensitised, rather than biased or broken. This desensitisation goes beyond comparison with technoscientific assessments of risk and to what extent residents are in agreement with them.

Desensitised risk perception encompasses a broad range of interacting material, social and cultural aspects including ideas about the causes and future trajectory of floods. In Tambelan Sampit where the community has long been exposed, and become accustomed to, extensive floods, people do not worry about increased flood risk in the near future. It is not the case that residents are somehow uneducated or unaware of the fact that their neighbourhood is periodically inundated. The characteristics of these floods and the specific socio-cultural context of Tambelan Sampit, have desensitised worry and awareness. As a result, their flood preparedness is desensitised, narrowing people’s ideas about potential interventions and leading to inadequate (demand for) mitigation and adaptation concerning future scenarios (WorldBank, Citation2018).

Examining individual risk perception without taking into account the socio-cultural context and the specific type of disaster can result in problematic assumptions about the role of individuals. The costs these people suffer from floods are not of their own making. They are the results of the climate crisis and other environmental issues (e.g. water quality problems and land degradation), taking place in a policy vacuum (e.g. for waste management) and general neglect of people living in urban kampong. Therefore, blaming people for their supposedly broken risk perception ties into broader discussions on climate and environmental justice (Sultana Citation2022). Furthermore, portraying people on the front lines of climate change as inherently vulnerable and unable to adequately comprehend their own exposure to hazards such as floods diminishes awareness of their agency, capacities and contextual knowledge (Mikulewicz, Citation2020; Thomas & Warner, Citation2019). Calling flood risk desensitised does not solve all of these problems, and may still imply that the onus is on residents to adjust their perceptions, but we hope it draws attention to the fact that respondents’ risk perceptions are in fact well suited to the socio-cultural context and should be taken seriously.

Flood management can only be effective if society’s risk perception is fully understood (Bradford et al., Citation2002). Given the global prevalence of extensive floods, it is therefore important to further understand desensitised risk perceptions in such under-researched contexts. Further research could also explore other extensive risks (e.g. droughts) in different socio-cultural contexts around the world. Due to the lack of qualitative methods in flood risk perception literature, there is ample opportunity for social researchers to further develop a holistic approach, bridging the gap between purely subjective or purely cultural explanations of risk perception. The findings therefore contribute to a better understanding of the context-specific nature of risk perception, relating to an increasingly common and problematic form of disaster worldwide.

Acknowledgments

The first author wishes to thank his interpreter Resi Rafsanjani. Above all, he wants to thank the people of Tambelan Sampit who have welcomed him into their lives with unprecedented hospitality, in particular his dear friend Yudhie.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adelekan, I. O., & Asiyanbi, A. P. (2016). Flood risk perception in flood-affected communities in Lagos, Nigeria. Natural Hazards, 80(1), 445–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-015-1977-2

- Alaszewski, A. (2015). Anthropology and risk: Insights into uncertainty, danger and blame from other cultures – a review essay. Health, Risk & Society, 17(3-4), 205–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2015.1070128

- Alvesson, M., & Sköldberg, K. (2017). Reflexive methodology: New vistas for qualitative research. Sage.

- Boholm, Å. (2003). The cultural nature of risk: Can there be an anthropology of uncertainty? Ethnos, 68(2), 159–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/0014184032000097722

- Bolay, J.-C., Chenal, J., & Pedrazzini, Y. (2016). Learning from the slums for the development of emerging cities. Springer.

- Boomgaard, P. (2007). In a state of flux: Water as a deadly and a life-giving force in Southeast Asia. In P. Boomgaard (Ed.), A world of water: Rain, rivers and seas in Southeast Asian histories (pp. 1–23). KITLV Press.

- Bradford, R. A., O'Sullivan, J. J., van der Craats, I. M., Krywkow, J., Rotko, P., Aaltonen, J., & Bunnell, T. (2002). Kampung rules: Landscape and the contested government of urban(e) malayness. Urban Studies, 39(9), 1685–1701. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980220151727

- Chavda, S., Drigo, V., & Taub, J. (2022). Why are people still losing their lives and livelihoods to disaster? 100,000 perceptions of risk from Views from the Frontline..

- Douglas, M., & Wildavsky, A. (1983). Risk and culture: An essay on the selection of technological and environmental dangers. Univ of California Press.

- Evers, J. (2015). Kwalitatieve analyse: kunst én kunde: Boom Lemma Uitgevers.

- Faas, A. J., & Barrios, R. E. (2015). Applied anthropology of risk, hazards, and disasters. Human Organization, 74(4), 287–295. https://doi.org/10.17730/0018-7259-74.4.287

- Few, R. (2003). Flooding, vulnerability and coping strategies: Local responses to a global threat. Progress in Development Studies, 3(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1191/1464993403ps049ra

- Gilbert, A. (2007). The return of the slum: Does language matter? International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 31(4), 697–713. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2007.00754.x

- IFRC. (2020). World disasters report 2020: Come heat or high water, tackling the humanitarian impacts of the climate crisis together. Geneva, Switzerland: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.

- Johnson, B. B., & Covello, V. T. (2012). The social and cultural construction of risk: Essays on risk selection and perception. Springer.

- Johnson, B. B., & Swedlow, B. (2021). Cultural theory's contributions to risk analysis: A thematic review with directions and resources for further research. Risk Analysis, 41(3), 429–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13299

- Komendantova, N., Patt, A., & Scolobig, A. (2014). Understanding risk: The evolution of disaster risk assessment. In.: GFDRR/International Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

- Lechowska, E. (2018). What determines flood risk perception? A review of factors of flood risk perception and relations between its basic elements. Natural Hazards, 94(3), 1341–1366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-018-3480-z

- Lechowska, E. (2022). Approaches in research on flood risk perception and their importance in flood risk management: a review. Natural Hazards, 111(3), 2343–2378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-021-05140-7

- Lee, T. M., Markowitz, E. M., Howe, P. D., Ko, C.-Y., & Leiserowitz, A. A. (2015). Predictors of public climate change awareness and risk perception around the world. Nature Climate Change, 5(11), 1014–1020. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2728

- Li, T. M. (2015). Social impacts of oil palm in Indonesia. Bogor, Indonesia: Center for International Forestry Research.

- Luo, Y., & Zhao, J. (2021). Attentional and perceptual biases of climate change. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 42, 22–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.02.010

- Merten, J., Nielsen, JØ, Soetarto, E., & Faust, H. (2021). From rising water to floods: Disentangling the production of flooding as a hazard in Sumatra, Indonesia. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 118, 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.11.005

- Merten, J., Stiegler, C., Hennings, N., Purnama, E. S., Röll, A., Agusta, H., Dippold, M. A., Fehrmann, L., Gunawan, D., Hölscher, D., Knohl, A., Kückes, J., Otten, F., Zemp, D. C., & Faust, H. (2020). Flooding and land use change in Jambi Province, Sumatra: integrating local knowledge and scientific inquiry. Ecology and Society, 25(3), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-11678-250314

- Mikulewicz, M. (2020). The discursive politics of adaptation to climate change. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 110(6), 1807–1830. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2020.1736981

- Mizutori, M., & Guha-Sapir, D. (2020). The human cost of disasters: An overview of the last 20 years (2000-2019). Centre for research on the epidemiology of disasters (CRED) and united nations office for disaster risk reduction (UNDRR), Belgium and Switzerland.

- Nas, P. J. M., Boon, L., Hladká, I., Tampubolon, N. C. A., Schefold, R., & Nas, P. J. M. (2008). The kampong. In Reimar Schefold, Peter J. M. Nas, Gaudenz Domenig, & Robert Wessing (Eds.), Indonesian houses: Volume 2: Survey of vernacular architecture in western Indonesia (pp. 645–667). Brill.

- Nygard, M. (1996). The Muslim concept of surrender to God. International Journal of Frontier Missions, 13(3), 125–130.

- Octifanny, Y., & Norvyani, D. A. (2021). A review of urban kampung development: The perspective of livelihoods and space in two urban kampungs in pontianak, Indonesia. Habitat International, 107, 102295. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2020.102295

- Olofsson, A., Öhman, S., & Nygren, K. G. (2016). An intersectional risk approach for environmental sociology. Environmental Sociology, 2(4), 346–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/23251042.2016.1246086

- Penning-Rowsell, E. C., Priest, S. M., & Cumiskey, L. (2022). Flooding. In T. C. McGee & E. C. Penning-Rowsell (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Environmental Hazards and Society (pp. 88–105).

- Perera, D., Agnihotri, J., Seidou, O., & Djalante, R. (2020). Identifying societal challenges in flood early warning systems. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 51, 101794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101794

- Perera, D., Seidou, O., Agnihotri, J., Rasmy, M., Smakhtin, V., Coulibaly, P., & Mehmood, H. (2019). Flood early warning systems: A review of benefits, challenges and prospects. UNU-INWEH, Hamilton.

- Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D. C., Adams, H., Adler, C., Aldunce, P., Ali, E., Begum, R. A., Betts, R., Kerr, R. B., & Biesbroek, R. (2022). Climate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: IPCC.

- Raaijmakers, R., Krywkow, J., & van der Veen, A. (2008). Flood risk perceptions and spatial multi-criteria analysis: An exploratory research for hazard mitigation. Natural Hazards, 46(3), 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-007-9189-z

- Renn, O., Jaeger, C. C., Rosa, E. A., & Webler, T. (2000). The rational actor paradigm in risk theories: Analysis and critique. Springer.

- Rentschler, J., Avner, P., Marconcini, M., Su, R., Strano, E., & Hallegatte, S. (2022). Rapid urban growth in flood zones: Global evidence since 1985. Policy research working paper series 10014. the World Bank.

- Rentschler, J., Klaiber, C., & Vun, J. (2021). Floods in the neighborhood: Mapping poverty and flood risk in Indonesian cities. In World Bank Blogs: World Bank.

- Rentschler, J., Salhab, M., & Jafino, B. A. (2022). Flood exposure and poverty in 188 countries. Nature Communications, 13(1), 3527. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30727-4

- Rocco, R., & van Ballegooijen, J. (2019). The Routledge handbook on informal urbanization. Routledge.

- Sampurno, J., Ardianto, R., & Hanert, E. (2023). Integrated machine learning and GIS-based bathtub models to assess the future flood risk in the Kapuas River Delta, Indonesia. Journal of Hydroinformatics, 25(1), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.2166/hydro.2022.106

- Sampurno, J., Vallaeys, V., Ardianto, R., & Hanert, E. (2022). Modeling interactions between tides, storm surges, and river discharges in the Kapuas River delta. Biogeosciences (online), 19(10), 2741–2757. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-19-2741-2022

- Schlehe, J., & Yulianto, V. I. (2020). An anthropology of waste. Indonesia and the Malay World, 48(140), 40–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639811.2019.1654225

- Schmuck, H. (2000). “An Act of Allah”: religious explanations for floods in Bangladesh as survival strategy. International Journal of Mass Emergencies & Disasters, 18(1), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/028072700001800105

- Seebauer, S., & Babcicky, P. (2018). Trust and the communication of flood risks: Comparing the roles of local governments, volunteers in emergency services, and neighbours. Journal of Flood Risk Management, 11(3), 305–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12313

- Shaw, R., Luo, Y., Sung, T., & Sharina, A. H. (2021). Asia. in: Climate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- Siegrist, M., & Gutscher, H. (2006). Flooding risks: A comparison of Lay people's perceptions and expert's assessments in switzerland. Risk Analysis, 26(4), 971–979. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2006.00792.x

- Spradley, J. P. (1980). Participant observation. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research. Sage publications.

- Sultana, F. (2022). Critical climate justice. The Geographical Journal, 188(1), 118–124.

- Thiault, L., Marshall, P., Gelcich, S., Collin, A., Chlous, F., & Claudet, J. (2018). Space and time matter in social-ecological vulnerability assessments. Marine Policy, 88, 213–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.11.027

- Thomas, K. A., & Warner, B. P. (2019). Weaponizing vulnerability to climate change. Global Environmental Change, 57, 101928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.101928

- UNDRR. (2022a). Humanity’s broken risk perception is reversing global progress in a ‘spiral of self-destruction’, finds new UN report. In. New York/Geneva: United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction.

- UNDRR. (2022b). Global assessment report on disaster risk reduction 2022. United Nations.

- Van Voorst, R. (2014). Get ready for the flood! risk-handling styles in Jakarta, Indonesia [Phd thesis]. Universiteit van Amsterdam.

- Van Voorst, R. (2016). Natural hazards, risk and vulnerability: Floods and slum life in Indonesia. Routledge.

- Wilkinson, I. (2001). Social theories of risk perception: At once indispensable and insufficient. Current Sociology, 49(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392101049001002

- Wisner, B., Blaikie, P., Cannon, T., & Davis, I. (2014). At risk: Natural hazards, people's vulnerability and disasters. Routledge.

- World Bank. (2018). Integrated urban flood risk management practices in Indonesia: Based on reviews of practices in the cities of ambon, Bima, Manado, Padang, and Pontianak. Indonesia Sustainable Urbanization Multi-Donor Trust Fund: Jakarta, Indonesia.

- World Bank. (2020). Designing Flood Resilient Cities, integrated approaches for sustainable development / Bima, Manado and Pontianak, final Report.

- Zoll, D., Bixler, R. P., Lieberknecht, K., Belaire, J. A., Shariatmadari, A., & Jha, S. (2023). Intersectional climate perceptions: Understanding the impacts of race and gender on climate experiences, future concerns, and planning efforts. Urban Climate, 50(2023), 101576.

- Zulu, E. M., Beguy, D., Ezeh, A. C., Bocquier, P., Madise, N. J., Cleland, J., & Falkingham, J. (2011). Overview of migration, poverty and health dynamics in Nairobi City's slum settlements. Journal of Urban Health, 88(2), 185–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-011-9595-0