ABSTRACT

Purpose

To reveal the features of Lithuanian male nurses’ professional becoming.

Methods

The participants were six men who had been working as nurses for over a year, and one man who had been formerly employed as a nurse for over a year. Data was collected using semi-structured interviews and analysed using inductive thematic analysis by Braun & Clarke.

Results

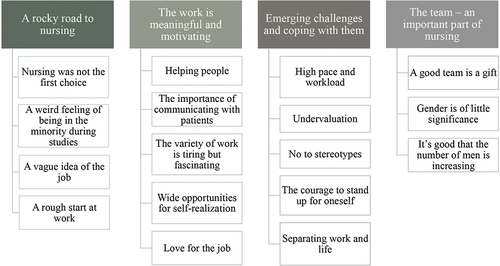

17 themes emerged after analysis: nursing not being the first choice, weird feelings of being in the minority during studies, having a vague initial idea of the work and a hard time starting the job; desire to help and interact with people, a tiring but fascinating variety of work, wide professional opportunities and love for the job; the challenges of high pace and workload, undervaluation and stereotypes, coping by standing up for oneself and separating work and life; the importance of a good team, gender being of little significance and joy that the number of men is increasing.

Conclusion

These findings contribute to the growing knowledge of male nurses’ experiences. The study sheds light on the challenges and rewards of being a male nurse in Lithuania, providing guidance for future research and highlighting the need to raise public awareness.

1. Introduction

Nurses are the largest and one of the most important groups of specialists in the healthcare system (World Health Organization, Citation2020). Their work is extremely important for the overall well-being of patients, as nurses not only perform technical tasks, but also take care of other aspects of health care, such building personal relationships with patients and spending time with them; anticipating and meeting their needs; responding to acute conditions; providing emotional support for patients and their families; collaborating with specialists from other fields in a multidisciplinary team; staying current on new technologies, seeking professional development, applying evidence-based knowledge in practice; educating patients, their relatives and novice nurses (Smith, Citation2012). Competent and adequate nursing for every patient is one of the main healthcare priorities worldwide (World Health Organization, Citation2020).

However, there is a noticeable shortage of nurses in many countries of the world (Drennan & Ross, Citation2019; World Health Organization, Citation2020). Lithuania is no exception—there were fewer than two nurses per doctor in 2019 (OECD & European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Citation2021). In addition, it is predicted that the shortage of nurses will only increase in the coming years (OECD & European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Citation2021). Researchers suggest various possible reasons for this phenomenon: an ageing population and workforce, emigration, low wages, long working hours, high workload, burnout, stress, emotional and physical abuse, etc (Glerean et al., Citation2017). But there is another long-term problem that likely contributes to this shortage—the low number of male nurses (Glerean et al., Citation2017; Haddad et al., Citation2022).

Although the number of men in nursing is increasing, it remains a female-dominated field. Only about 10% of nurses are men (World Health Organization, Citation2020), and in Lithuania the number is even lower—less than one percent (Lithuanian Department of Statistics, Citation2015). Due to historical circumstances, nursing is generally perceived as an unskilled, submissive profession only fit for women and inferior to medicine, and there are various stereotypes about the men who choose it (Arif & Khokhar, Citation2017; Glerean et al., Citation2017). Although until the middle of the 19th century men and women had a somewhat equal place in nursing, with the beginning of the nursing reform led by Florence Nightingale, the Victorian family model prevailed in medicine: doctors were seen as the male heads of the family, nurses as submissive women, and patients as children in need of care (Evans, Citation2004; Meadus & Twomey, Citation2006, as cited in; Wolfenden, Citation2011). This period also saw the rise of the essentialist view that women were naturally more caring, gentle and nurturing, while men were rough and incapable of properly caring for those suffering (Burns, 1998; as cited in McMurry, Citation2011). Since then, men have been encouraged to choose the more socially acceptable medical profession (Evans, Citation2004, Meadus ir Twomey, 2006, as cited in; Wolfenden, Citation2011). As Wolfenden (Citation2011) observes, in times of high gender inequality nursing opened the way for women into the labour market, but as the gender gap narrowed, they began to choose other professions, while men are still hesitant to return to nursing.

To attract and retain more men in the nursing profession, it is crucial to better understand the lived experiences of men who choose the profession—from the beginning of their studies to the daily experiences on the job. This continuous process of becoming and being a nurse can be called professional becoming. It is a dynamic process during which nurses embrace the core values of nursing, engage in professional activities, develop the required competencies, become aware of what the role entails, experiment with that role and adapt it for themselves, identify with the role and start to feel confident, and create a self-perception that is based on the image of nursing in the public and in their own environment (Halverson et al., Citation2022). Once the professional identity is formed, the nurse embodies the essential features of the profession and feels job satisfaction but also becomes aware of the challenges experienced at work and difficulties balancing personal and professional life (Halverson et al., Citation2022).

Although the low number of male nurses in Lithuania is considered a long-term problem, scientific research in this field is just beginning. There is a clear lack of literature related to the issue: some studies include men in the sample but due to their small number the analysis is not carried out by differentiating by gender; others do not include men at all because there are no male nurses working in the institutions where research was conducted (Balsienė, Citation2017; Meižytė & Blaževičienė, Citation2022). Considering the lack of scientific literature and the stereotypes of nursing prevalent in society, it can be said that little is known about male nurses in Lithuania, their entry into and retention in the profession. This encourages the exploration of the professional becoming of male nurses in order to expand the scientific knowledge of the field. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to reveal the characteristics of the professional becoming of male nurses and the main research question is “What are the characteristics of the professional development of male nurses?”. There are also two objectives: (1) To reveal the features of men‘s entry into the nursing profession; (2) To reveal the work experiences of male nurses.

We expect this study to contribute to a deeper understanding of the unique motivators and challenges experienced by male nurses, as well as to inform further research, policy discussions and practice recommendations aimed at promoting equity and inclusivity in the nursing profession.

2. Methods

2.1. Theoretical methodological paradigm

Male nurses are a relatively small, specific sample. Little scientific research has been done about them in Lithuania, so there is a lack of information about their inner world, career path, and experiences. In order to look at these things in depth and in detail, without preconceived notions, a descriptive qualitative research model was chosen. Since qualitative research usually does not rely on established theories and does not formulate hypotheses, this model is suitable for uncovering little-researched, new topics where it can be difficult to make scientifically informed assumptions (Cypress, Citation2015).

2.2. Participants

The study included six people who met the selection criteria established before the study: men who had graduated from nursing studies and had been working as nurses for more than one year, and one person who met two of the three selection criteria (a man who graduated from nursing studies) as at the time of the interview he was not employed as a nurse but had formerly worked as a nurse for over a year. Male nurses who had less than a year of experience in nursing as well as nursing students were excluded. The ages of the participants ranged between 25 and 40 years, and work experience was from two to 13 years. All the participants saw an invitation to participate in the study on social media and reached out to the authors by a messaging app or email. All participants gave their informed consent to the study. Because of the small number of male nurses in Lithuania, the preliminary sample size was eight participants, but taking into account the informativeness of the data collected during the interviews, it was decided that saturation was reached after seven interviews.

2.3. Data collection

Interviews with the participants were conducted in December 2022 – January 2023, after obtaining ethical approval from the bioethics centre. At the request of the participants (due to busyness and/or distance), the interviews were held remotely, via Messenger or Microsoft Teams programs. Interview length ranged from 32 to 63 minutes and the average interview duration was 40.8 minutes. During each interview, the participant and the researcher were alone, undisturbed by other people, in a quiet, comfortable environment of their choosing. The first author, who had previous experience conducting semi-structured interviews in a small-scale study, served as interviewer for all interviews.

A semi-structured interview method was chosen for data collection. Participants were asked questions that were prepared in advance and, if necessary, spontaneous clarifying questions. The first question was designed to collect demographic information, seven were core questions related to the research topic, and the last question was a follow-up question (“Is there anything else you would like to say that I have not asked you?”). The participants were asked about their choice of profession, studies, first year of work, current work, as well as about emerging challenges, overcoming them, motivational factors, and self-perception in the context of female nurses. The questionnaire was created by the authors and pilot tested in the first interview. One question (“What does being a nurse generally mean to you?”) was added to the interview guide after this interview, when it arose naturally. The questions were open-ended and broad, aiming to give the participants enough freedom to expand upon the most important aspects of their experience without straying from the research topic. Clarifying questions were used to further inquire about a specific thought, expand and detail the story or return to unfinished thoughts. The interviews were audio recorded by the interviewer and transcribed verbatim. Data saturation was achieved after interviewing seven participants.

2.4. Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted by applying the descriptive qualitative method. Firstly, all the data collected during the interviews was processed using the transcribing function in Microsoft Word. After the initial transcription the interviews were carefully read and amended: errors were corrected; names were changed; other identifying details, such as countries, cities, and workplaces, were hidden; emphatic phrases were underlined; silent pauses, emotions and non-verbal language were marked. After this, the texts were reviewed twice more—after the transcription of one entry was completed and after the entire transcribing phase was completed. Remaining unnoticed errors were corrected. The transcripts were not returned to participants for review after the transcription process to preserve original language and initial thoughts.

After all seven interviews were transcribed, an inductive thematic analysis according to Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) was conducted. This method was chosen because it is independent of theory, flexible but structured, and by revealing the most prominent themes in data can create a general picture of the phenomenon. The analysis was done manually, following the stages specified by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006): (1) familiarizing oneself with the data—reading transcripts multiple times and writing down initial ideas; (2) generating initial codes—dividing the text into smaller meaningful units and coding for as many potential patterns as possible; (3) searching for themes—printing the codes and sorting them into potential theme piles; (4) reviewing the themes—refining the themes by comparing them to the text and devising a satisfactory thematic map; (5) defining and naming the themes—identifying the core meanings of the themes and naming them accordingly; (6) producing the report—telling a story of the data by using vivid and meaningful data extracts. In accordance with these guidelines, participants were not contacted to provide feedback on the findings.

2.5. Rigor

The rigour of this study was ensured in three ways:

By keeping a researcher’s journal. Constantly reflecting on arising difficulties, joys, preconceptions, subjectivities, etc., gave the researcher a chance to freely express accumulated thoughts and feelings, and to understand the reasons behind their origin;

By conducting the literature review after the data analysis. This was done to distance oneself from prior knowledge and allow the participants to be the experts of their own experiences. Prior to the analysis stage, articles were researched only to get a general idea and the prevalence of the topic;

By transparently and thoroughly describing the research methodology. This is to openly show the reader the strengths and limitations of the study, including the inevitable subjectivity of the researcher.

2.6. Ethical considerations

Strict ethical requirements were followed to protect research participants from any harm. Before starting the study, it was approved by the Bioethics Center of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences (No. BEC-SP(B)-29). All participants were briefly informed about the conditions of the study in writing and in more detail orally before the interview. They were introduced to the purpose and course of the study: the processes of data collection, analysis and storage, presentation of the research and the possibility to get acquainted with the results. Participants were also informed about possible inconveniences (wasted time and/or psychological discomfort) and the possibility of not answering questions or withdrawing from the study.

Anonymity of the research participants was ensured in several ways. First, during remote interviews, the researcher was alone in the room and wore headphones. Second, all personal information collected during the interviews was altered or omitted during transcription. Finally, minimal demographic information about the participants is presented in the paper, as the small number of male nurses in Lithuania may make it especially easy to identify them.

3. Results

After analysing all seven interviews, a system of common themes was formed, revealing the characteristics of male nurses’ professional becoming (). Analysing and combining the codes revealed 17 subthemes recurring in at least half (4/7) of the narratives of the study participants. After combining the subthemes, four major themes were distinguished: “A rocky road to nursing”; “The work is meaningful and motivating”; “Emerging challenges and coping with them”; “The team—an important part of nursing.”

3.1. A rocky road to nursing

The first theme “A rocky road to nursing” discusses the study participants’ entry into nursing—the process of choosing the profession, nursing studies and experiences at the start of work. This arrival was quite difficult for most of the men who participated in the study, as they faced doubts about the profession, unusual experiences at school and difficulties adapting to independent work.

3.1.1. Nursing was not the first choice

When talking about how they decided to become nurses, the men who participated in the study emphasized that nursing was not the first and only profession that interested them. Some study participants initially saw nursing as a stepping stone to medicine but changed their minds during their studies. One participant was enrolled in another study programme but changed his mind before the studies began, while the other participants entered nursing having already had work experience in other positions in healthcare. However, even though nursing was not the first area of interest for the participants, they felt satisfied with how their career path turned out:

< … > I got so involved in all that nursing that four years later I’m looking at the operating room and it’s like … someone hit my head with a hammer: Participant 5, everything’s okay, you’re in the right place. (Participant 5, 5)

3.1.2. A weird feeling of being in the minority during studies

While studying nursing, all participants were surrounded by women in their course, and some did not have a single male coursemate. Several research participants described this experience as strange and unusual, especially at the beginning of their studies:

Well, the study experience, you know, when you are, there were two of us among thirty girls. So yeah, it seems a little strange at first, you know, [clears throat] and you sometimes think maybe you’re not in the right place or something. (Participant 1, 24)

Although being in the minority did not cause participants great discomfort or feelings of exclusion, such studies presented specific challenges. Two participants felt that they were more noticeable to teachers because of their gender. For one, the source of unpleasant feelings was a devaluation of his opinions in the course, and for another—the expectation of fellow students that he, as a man, would want to be a leader among his fellow students.

3.1.3. A vague idea of the job

Before starting internships and/or work, most research participants had formed a certain abstract idea of their future job, but it later turned out not to be entirely correct. These ideas were related to participants’ previous experiences with nursing and attitudes towards it at the time. One participant, who mostly learned about nursing from old books, thought he would have to be a physician’s assistant:

Well I … no, I might have even imagined it a little worse than it actually was [laughing]. < … > Because that “medical sister” in Soviet times, she was purely a nurse— doctor’s helper, doctor’s assistant. (Participant 4, 145–147)

Another participant, who now works as an ambulance nurse, had imagined the job to be full of non-stop action but experience taught him that it was much more relaxed. A third participant said that initially he was not interested in nursing and did not understand it because his attention was focused on another profession—medicine. Another participant, who had formed a rough understanding of the profession through volunteering, was most surprised not by the work itself, but by its real conditions:

Well, that youthfulness, when you think that there is that perfect place somewhere, where everything is fine, where there are no schemes, and, I don’t know, you always get, I don’t know, the newest equipment, the latest tools, well, sometimes that doesn’t happen. (Participant 7, 109)

3.1.4. A rough start at work

Most study participants encountered difficulties when adapting at a new job. Difficulties arose when learning how to plan your day in a way that it was possible not only to work, but also meet your needs. It was also a challenge to not only to learn technical things, such as how to perform procedures or recognize drugs, but at the same time adapt to an unfamiliar environment and team:

The hardest days were probably the very beginning of work, until you, well, < … > learn that department’s rules, understand the atmosphere of that department, better understand, let’s say, the social climate, and at the same time learn new things, technical things. (Participant 4, 95)

However, in the end the nurses were happy that this difficult phase was now in the past and that they were able to successfully overcome the challenges of that time.

3.2. The work is meaningful and motivating

The second topic “The work is meaningful and motivating” talks about the study participants’ motivation to choose a profession and remain in it: the desire to help people and maintain an empathic relationship with them, the variety of everyday work, wide professional opportunities and the love experienced for nursing.

3.2.1. Helping people

All research participants highlighted helping other people as one of the most important parts of a nurse’s work and the value upon which the profession is based. They were happy to see when their efforts and their team’s efforts were improving patients’ health:

< … > of course, it is very good to see patients leaving the ward, recovering and, well, if we’re talking about that [clicks tongue] ideological part, then that ideological part was for me, I liked it, it felt good when my patients got well. (Participant 4, 134)

The fact of facing death at work was also significant for the participants of the study. It was important for them to know and to feel that they could delay death of patients, even if it was only temporary. However, the men also saw meaning in helping people in their last moments:

And sometimes you will also feel that you have contributed to the patient’s passing, because… because just as a person needs to come into life, sometimes you also need to help them depart. <…> You feel like you have done a good deed. (Participant 3, 118)

The feeling of doing meaningful, good and altruistic work helped their motivation and desire to keep working, and the help provided also resulted in the patients’ gratitude, which brought moral reward to the nurses.

3.2.2. The importance of communicating with patients

For most of the nurses who participated in the study, communicating with patients was just as important as medical assistance. Nurses understood that in some cases a simple conversation could be as useful a therapeutic tool as any other procedure:

<…> those conversations with those patients, because it is not only medical treatment that treats them, those people, but also psychological help, meaning conversation, comfort, talking, communication. (Participant 2, 106)

They attached great importance to empathic listening to patients and were critical of those medical professionals who did not do so. The nurses admitted that communication was not easy with all patients, but they tried to find an appropriate connection with each of them. Even those participants who had little contact with patients due to the specifics of their job tried to make meaningful use of the time they spent together. In addition, nurses emphasized that their ability to listen, empathize and support determines how they are perceived by their patients:

That’s why we have those < … > nurses, right, where <…> “I wouldn’t want this one”, in the sense that this medic is very rude or something, “and this one is really nice to me, he helped me a lot”, <…> Although, it seems, they work the same way, they do the same procedures, but not everything is just about procedures. [clears throat] (Participant 2, 117)

3.2.3. The variety of work is tiring but fascinating

The study participants saw their work as very varied, dynamic and unpredictable. One of the participants described his work as “non-monotonically monotonous:

Essentially, the work, the monotony, <…> the principle is basically exactly the same, but no shift is the same as the day before, the patients change, or something else. (Participant 6, 42)

Each workday for the nurses differed in workload, nature of work, and patient characteristics. This created its own challenges, not only because it was physically tiring, but also because of the inability to be perfect in everything that you have to do at work. However, the study participants viewed challenges as opportunities to grow and learn. Also, they expected and wanted to encounter fast-paced, adrenaline-filled situations at work, so they chose workplaces characterized by them. For these reasons, the daily variety of work, despite the fatigue it caused, charmed and motivated the participants.

3.2.4. Wide opportunities for self-realization

Most of the research participants were happy that nursing was a broad field in which they could realize their potential. They were interested not only in the practical side of nursing—working with patients—but also the theoretical, scientific part of it. Some nurses sought to give meaning to their profession by teaching people who were just coming into nursing. They also enjoyed the open opportunities to choose a field and workplace that would allow them to properly express themselves:

It is a very broad thing, well, you can work in various fields and… yeah, you have, what’s the word, education. And it, I think, is a flexible major. Where, simply, you don’t like one section –you can go to another section. Also do practical work or also theoretical work, for example, there, somewhere, at a university, for example. (Participant 5, 119)

Overall, the self-realization experienced on the job assured the nurses that they were on a right and fitting career path.

3.2.5. Love for the job

Finally, the research participants felt passion for the work and love for their profession. This feeling was strong and accompanied every, even the most difficult, workday, and helped the nurses to better cope with the challenges that arose at work. The negative aspects of the job, such as low pay or work stress, paled in comparison to the passion they felt. And although the work was not easy, being a nurse was a meaningful and extremely important part of the participants’ lives:

<…> I wouldn’t say that you find inner harmony there <…> but ah, well, it’s actually work… to which, well, I wouldn’t say you go like it’s a holiday, no, definitely not, but it’s really nice to work, actually, it’s a pleasure to work. Because… in the end, you are helping people <…> (Participant 6, 143–144)

So, to me being a nurse means… perspective… to me it means love the for work, love for myself, because I couldn’t imagine a life without it, and improvement. (Participant 5, 125)

3.3. Emerging challenges and coping with them

The third theme, “Emerging challenges and coping with them”, reveals that the main difficulties encountered by the study participants were high workload and fast pace, moral and financial devaluation of their work, and stereotypical societal attitudes towards male nurses. The ability to stand up for themselves and maintaining a work-life balance helped them to overcome these challenges.

3.3.1. High pace and workload

The participants considered high workload and high pace to be one of the biggest challenges of their profession. Some of them worked in places where it was not easy to find time to relax due to the heavy workload (e.g., emergency room, intensive care units), while others had to work at an extremely high speed due to the specifics of their work (e.g., ambulance). The nurses described the most difficult days as those when the number of patients was particularly high, and the easiest—those when got had a chance to rest. However, days like that were few and far between:

<…> the most difficult thing is when you physically have more patients than you can take care of. (Participant 7, 55)

The easiest day in the ambulance is when <…> you don’t get any, any call for help. Like, all people are just fine that day. Of course, that’s not the case most of the time …. (Participant 1, 78–79)

3.3.2. Undervaluation

Most of the men in the study felt that their work and efforts were undervalued. Firstly, it manifested in inadequate wages. One of the study participants, who at the time of the interview was not working as a nurse, singled out insufficient pay as the main reason for leaving the field:

<…> I moved to another country and in that country…. there were other opportunities, well, let’s say, maybe there were opportunities to earn a higher salary with the education I have. <…> So, the salary. (Participant 4, 130)

However, the study participants experienced not only financial but also moral devaluation. They felt as if the return they received did not reflect the amount of work and effort they put in. Additionally, the men noted a lack of appreciation not only in the workplace, but on a wider scale, and were saddened by the fact that most nurses had to deal with it:

<…> I personally cannot complain, but I know colleagues <…> who, male and female, work for a lot less pay, so it is very unfortunate that a job with quite <…> many responsibilities is completely undervalued, both morally and financially. (Participant 7, 116)

3.3.3. No to stereotypes

Male nurses were open about the fact that they faced stereotypes and stigmatization of their work. They noted that nursing was still seen as a female profession in society. Because of this, the participants faced distrustful attitudes from other people. One participant said that he had received scepticism from the staff during internships, and another received negative comments from patients as well. When another participant chose the nursing profession, he was unpleasantly surprised not only by the attitudes of society, but also those close to him:

So, there was that strangeness <…> because of society and because of my relatives, like “why exactly such a specialty”? “Why not some, you know, manly construction field”?. (Participant 1, 39)

The research participants also said that they faced various labels, for example, that all male nurses were homosexual, perverted, or had an inferiority complex. However, they not only disagreed with the mentioned stereotypes, but consciously tried to show those around them that nursing was a profession suitable for men as well as women:

Let’s take, for example, America, where a large proportion of nurses are male, so we can simply… spread the message that it’s… a good job, yeah. Which you can do, and you want to fall in love with. (Participant 5, 133)

Importantly, some of the participants were happy to see that societal attitudes were changing, albeit slowly, and nursing was slowly starting to be seen as a suitable career choice for both women and men.

3.3.4. The courage to stand up for oneself

Being able to stand up for themselves was important to the men in the study. They realized that it was necessary to adequately evaluate the work they do and to defend it when the situation calls for it:

Well, how should I say this, you must not belittle yourself, but also… you can’t be a rag for everyone to clean their feet, so, well, you just have to know your place, simply put. So … sometimes you have to snap back, in a nice way of course, and stand up for yourself, so, just as in real life, the same here. (Participant 6, 72–73)

This trait served the participants well early in their careers, during internships, where they had to deal with being asked to perform humiliating tasks, and later, once established in the workplace, where it helped them communicate with doctors who were demeaning and disrespectful towards male nurses or nurses in general:

But again, once again, like I said, the doctors from the older generation, they sometimes try to remind you that after all you are a male “sister”. Sometimes you have to remind them that not anymore. [laughing] (Participant 4, 150)

3.3.5. Separating work and life

Most of the study participants tried to draw strict boundaries between their professional and personal roles. One of them described how the “switch” occurs when going to and leaving work:

<…> you just come to work, unlock your locker, change your clothes, find your pajamas and, in a sense, everything disappears. You come just to do your job. Likewise, when you finish work – you change your clothes and try to forget about work. That’s it, you return to your life, like, at work I think about work, like, those family things, I leave them somewhere, and it’s the same when I finish work – work stays there somewhere. (Participant 6, 39–40)

The participants also talked about team efforts to talk things out and ventilate unpleasant emotions at work, so that after leaving one could focus on their role in the family. Distancing oneself from work worries through enjoyable activities, hobbies and spending time with loved ones was considered to be the best way to deal with emerging challenges and avoid harmful health consequences, such as burnout.

3.4. The team—an important part of nursing

The fourth theme “The team—an important part of nursing” describes the study participants’ experiences of teamwork, reveals the importance of having a strong, reliable team, the small personal significance of gender differences and the joy because of the increase of men in nursing.

3.4.1. A good team is a gift

The men in the study perceived nursing as teamwork and saw themselves as part of a team. Three participants in the study had previous experiences of hierarchy and disrespectful behaviour from doctors or senior nurses, so they highly valued a strong, close and equal team:

<…> when you change many workplaces, for example, I no longer value only, say, the salary or the working environment there, but the existing microclimate and the mentality of the employees, for example, mentality, education, culture are very important things, I think, <…> to make us feel better or worse at the workplace. (Participant 5, 63)

Colleagues not only helped nurses with job tasks, but also provided support when faced with challenges. Although interactions with colleagues were not always positive, fellowship and team spirit remained, so having a good team was very important to the participants:

Sure, <…> all kinds of things happen in the team, but the team does not take, I don’t know, light quarrels or something, to heart, and we continue, well, working as a team. (Participant 7, 106)

And the team, the team, without a team you’re nothing. So yeah, having a good team is really a gift. (Participant 2, 98)

3.4.2. Gender is of little significance

Most of the study participants did not attach much importance to the gender difference in a team. Although almost all men worked in a mostly female environment, they did not feel excluded, discriminated against or otherwise uncomfortable. The men who took part in the study believed that relationships with team members and professional competence depended not on the employee’s gender, but on their personality traits, and saw themselves as an equal, professional part of the team:

<…> I see myself as a full-fledged nurse. <…> The bottom line is that, well, you have to do the job [slowly] equally, professionally, no matter what your gender is, male or female, well, you must know your job. And do it right <…> (Participant 1, 86–87)

3.4.3. It’s good that the number of men is increasing

Although most study participants did not experience discomfort in a team because of their gender, they welcomed the increase of men in nursing. Some participants felt that they had personally contributed to the discussion about the need for male nurses in their workplaces and had laid the groundwork for men to work there. Most of the participants noticed a positive change when the number of male nurses began to increase. For some of them, it was important personally—they started to feel a stronger, closer backing at work. Others noted that with more men, the team became stronger—not only was there more physical strength, but the general atmosphere also improved:

Having more men has worked out, <…> sometimes the patient is heavier <…> his body is heavier, his mass, so then you need a hand or something <…> (Participant 6, 84–85)

<…> there is more concreteness, some new ideas have emerged, which are implemented in the ward, and just the general emotion is better <…> and the team itself, I think, when there are guys in a female team <…> somehow it looks more serious, stronger. (Participant 5, 71–73)

4. Discussion

After conducting the thematic analysis of the data, four major themes and 17 subthemes were identified. The results reflected the themes of a difficult entry into nursing, the meaning and motivation of work, challenges and ways to overcome them, and the importance of a team. Most of these themes and subthemes were consistent with the results of existing scientific research, but several new and conflicting themes were also discovered.

A difficult path to nursing is a topic often reflected in other studies. In them, themes of initial disinterest in nursing, it being the second choice, and vaguely imagining the future work can be found (Appiah et al., Citation2021; Banakhar et al., Citation2021; Guy et al., Citation2022; Qureshi et al., Citation2020; Snyder, Citation2011). It is likely that these experiences arose due to low public awareness and stereotypical attitudes towards nursing, as was observed by participants in both the current and previous studies (Banakhar et al., Citation2021; Qureshi et al., Citation2020; Snyder, Citation2011). Participants of Guy et al. (Citation2022) and Valizadeh et al. (Citation2014) studies stated that when they were young, they did not consider nursing as a career choice because they saw it the same way as the general public—as a womanly, unskilled, nonindependent job with no career prospects, and only realized that this was not the case when they started studying. It can be noted that the participants of the current study were always interested in the field of health care, but rejected nursing, and only changed their opinion after getting to know it personally. Thus, the data of this and previous studies show that the myths prevailing about nursing are best dispelled by personal interaction with it.

In the literature on the experiences of men studying nursing, the most prominent themes are discriminatory practices, hostile attitudes from teachers, exclusion from activities and negative societal attitudes (Abushaikha et al., Citation2014; Al-Momani, Citation2017; Banakhar et al., Citation2021; Carnevale & Priode, Citation2018; Kronsberg et al., Citation2018; Meadus & Twomey, Citation2011; Petges & Sabio, Citation2020). The participants in the current study said they did not feel discriminated against or excluded, but they found it strange and unusual to study in a mostly female environment. This discrepancy can be influenced by the methodology of the work, i.e., research objectives, wording of questions, and interpretations. It should also be considered that the reviewed studies were on students, while the present study was on practicing nurses. For them, the studies are a memory, but not an ongoing experience, so it is likely that they think about them differently, feel less strongly about those experiences, and remember them in less detail.

The nurses who participated in the study experienced a difficult adaptation period when they started independent work. They needed to adapt to new conditions and new social microclimate, learn the technical aspects of the job, and learn to effectively plan their schedule. Experiences like these are quite widely studied and are called transition shock. It is a process in which the expectations raised in the academic institution collide with the expectations raised at work, causing emotional, cognitive, social and physical reactions of varying intensity (Duchscher & Windey, Citation2018). Thus, the experiences of the study participants are consistent with the theoretical model of nurses’ transition from the educational to the professional setting.

The study found that helping people and communicating with patients were among the most important and meaningful aspects of nursing for the participants. The desire to help people is widely described in literature as one of the most important reasons why men choose the nursing profession (Appiah et al., Citation2021; Blackley et al., Citation2019; Meadus & Twomey, Citation2011; Petges & Sabio, Citation2020). Meanwhile, empathic communication with patients and providing emotional support is less common (Banakhar et al., Citation2021; Mao et al., Citation2020; Saleh et al., Citation2020). However, it is worth noting that in some studies these themes might be assigned to the theme of help, because, as the participants of the current study observed, it can be also an effective way of helping people.

Male nurses’ love for their work is not prominent in the existing studies, but the themes of perceived meaningfulness and personal rewards of nursing emerge in more than one study (Lyu et al., Citation2022; Petges & Sabio, Citation2020; Rajacich et al., Citation2013; Saleh et al., Citation2020). It is likely that the participants in these and the current study experienced similar feelings related to the profession, but described and named these feelings differently.

The themes of motivating variety of work and opportunities for professional self-realization revealed in the current study can be considered new. Only in the study by Meadus and Twomey (Citation2011), the high flexibility of nursing and the possibility to work in various fields emerged as a motivational factor for men to choose nursing. Some studies have also found contradictory findings to the present results, such as men not being able to work in desired fields or institutions (Mao et al., Citation2021; Rajacich et al., Citation2013). These discrepancies may be explained by cultural differences, where stricter cultural norms prevent men from choosing whichever nursing field. It can also be noted that for the current study’s participants not only the practical, but also the theoretical side of nursing was important, which broadened their perceived professional opportunities. As for the variety of work, it is not reflected in the literature about nurses—neither as a challenge, nor as a motivation. This can be associated with the current study’s participants’ specific workplaces and nature of work, as well as their personal characteristics—perseverance, boldness, enjoyment of intense and thrilling activities.

The results of the study revealed that male nurses faced several challenges: high workload and pace, financial and moral devaluation, stereotyping and stigmatization. High workload does not stand out in the literature on the experiences of male nurses but is considered to be one of the biggest universal challenges for nurses, causing work stress, hindering professional development, and reducing the quality of care (Coventry et al., Citation2015; Haahr et al., Citation2020; Labrague & McEnroe‐Petitte, Citation2018). Stereotyping of nursing and male nurses is also prominent in literature. It has been observed that society still sees nursing as a feminine profession, and there are various stereotypes about men who choose it (Abushaikha et al., Citation2014; Al-Momani, Citation2017; Carnevale & Priode, Citation2018; Meadus & Twomey, Citation2011; Petges & Sabio, Citation2020; Rabie et al., Citation2021). However, it is also important that the participants of this and some other studies noticed shifting public perceptions (Abushaikha et al., Citation2014; Smith et al., Citation2020). This shows favourable trends for acceptance of male nurses. Meanwhile, devaluation can be considered a controversial topic. Participants in some studies felt morally undervalued at work or in society (Banakhar et al., Citation2021; Rajacich et al., Citation2013; Valizadeh et al., Citation2014), and in one, financially undervalued (Qureshi et al., Citation2020). However, other studies highlight respect shown to nurses and good pay as motivation for choosing the profession (Meadus & Twomey, Citation2011; Petges & Sabio, Citation2020). However, considering the fact that the latter studies were conducted in relatively progressive countries (Canada and the USA), the discrepancies can be explained by the cultural characteristics of the studies. It is noteworthy that the results of this study are closer to those of the studies conducted in developing countries (Banakhar et al., Citation2021; Qureshi et al., Citation2020; Rajacich et al., Citation2013; Valizadeh et al., Citation2014).

The coping strategies that emerged in this study, i.e., standing up for oneself and work-life separation, cannot be found in other studies. Even the study by Blackley et al. (Citation2019), one of the tasks of which was to reveal coping strategies, does not reflect this topic. In general, literature examines the strategies for coping with challenges and stress of nursing students, but not working male nurses. However, considering that nursing poses several significant challenges for men, it is rather unwise not to research the coping strategies. This is worth considering when planning future research.

The data analysis revealed participants of this study highly valued a good team and did not attach much importance to the gender of their colleagues. In literature, the importance of the team is reflected mostly negatively, as male nurses experience exclusion, non-acceptance, rejection, and mutual disrespect in their relationships with female nurses (Blackley et al., Citation2019; Rajacich et al., Citation2013; Saleh et al., Citation2020; Valizadeh et al., Citation2014). However, a couple of studies reveal experiences of acceptance, mutual support, and help (Mao et al., Citation2021; Smith et al., Citation2020). In any case, it can be observed that the microclimate of the team is important for male nurses: bad relationships cause unpleasant feelings, while good ones are highly valued. The importance of gender also varies in existing studies. Studies by Mao et al. (Citation2021) and Valizadeh et al. (Citation2014) revealed that male nurses saw the profession as suitable for both sexes and dependent on personality traits, but the participants of the first study emphasized the lack of mutual respect with female colleagues. Furthermore, the already discussed themes of exclusion and non-acceptance suggest that gender differences are relevant to some relationships between male and female nurses. It is difficult to observe cultural trends in this topic, so the differing experiences may have more to do with specific workplaces, personal characteristics of research participants and their colleagues. Moreover, as observed by Blackley et al. (Citation2019), the gender ratio may also influence the perceived importance of gender in relationships within the team, as men working with more male peers develop better working relationships.

Finally, it should be noted that joy because the number of male nurses is increasing does not appear in the literature as a separate theme. However, in none of the studies reviewed did participants express a negative opinion of other male nurses. This theme may be new for two reasons: either the greater interest of men in nursing is not noticeable, or such experiences are subsumed into other similar topics, such as nursing being suitable for all sexes or the advantages of being a man in nursing.

This study has shown that male nurses in Lithuania face devaluation, stigmatization stereotyping from the public, and this seems to stem from low public knowledge and awareness. Educational and medical organizations must undertake initiatives to raise public awareness of nursing as a suitable career choice for men and women alike, emphasizing its highly technical, scientific nature as well as its caring, emotional aspects. Male nurses themselves should increase their visibility in the public eye to promote acceptance of male nurses and the value of nurses overall.

Notably, the educational experiences of male nurses in Lithuania were described as more positive than in other cultures, with the main challenge being the discomfort from a low number of male nursing students itself. While no discriminatory practices were reported in this study, educational institutions need to ensure access to help for students if they feel discomfort or face specific challenges like the ones mentioned by the participants of this study.

More research needs to be done on the experiences of male nursing students, beginner nurses and male nurses overall. This study has shown that nursing can be an exciting and fulfilling job, however, the people who choose this profession face significant psychological, social and physical challenges. This field is still under-researched by organizational psychologists, sociologists and nurse researchers, especially in the Lithuanian context. It is in the interest of public health to have well-adjusted, healthy and contented healthcare professionals, and this necessitates an increased understanding of their challenges and needs.

5. Strengths and limitations

The main advantage of this study is the coverage of a relevant yet little-researched topic. It is notable that there was considerable interest in the topic from the nursing community and the study participants emphasized its significance. This study has enriched knowledge about the experience of a small but important group that receives little attention in Lithuanian scientific literature. Considering the similarities revealed in this and other works, i.e., low public knowledge of nursing and the devaluation and stereotypes arising from it, this research could be applied to the creation of nursing popularization and information campaigns. It may also be useful for professionals working in nursing and other healthcare fields who want to better understand the experiences of their colleagues, as well as psychologists who consult nurses.

Several limitations of the study can be identified. First, all interviews were conducted remotely. Unfortunately, while this ensured the comfort of the study participants, it may have reduced openness and thus the depth of the results. Secondly, due to the qualitative research design, it is necessary to mention the possible subjectivity of the researcher. Although the author is not personally related to nursing and tried to avoid any subjectivity by keeping a researcher’s journal and limiting exposure to existing literature until the end of the data analysis, the possibility of unconscious bias cannot be ruled out. In addition, it must be recognized that the analysis of qualitative data will never be completely objective, as it reflects the author’s understanding of the text, expression of thoughts, and use of language.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, the professional development of the male nurses who participated in the study can characterized by four main aspects: (1) A rocky road to nursing; (2) The work is meaningful and motivating; (3) Emerging challenges and coping with them; (4) The team is an important part of nursing. This study contributes to the literature by providing information about the challenges and rewards of being a male nurse in Lithuania, a rarely researched yet highly stigmatized topic in society. Newly discovered themes, especially the coping strategies that emerged in the study, should be given specific attention in future studies. Importantly, since low public knowledge seems to be the main reason for devaluation and stigmatization of nursing as well as stereotypes about male nurses, there is a need to raise public awareness of the profession to accurately reflect its technical and scientific nature.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, A.G. and J.Ž.; methodology, A.G. and J.Ž.; validation, A.G.; formal analysis, A.G.; investigation, A.G.; resources, A.G. and J.Ž.; data curation, A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.; writing—review and editing, J.Ž.; visualization, A.G.; supervision, J.Ž.; project administration, A.G. and J.Ž. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval statement

This study was approved by the Bioethics Center of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences (No. BEC-SP(B)-29).

Geolocation information

This study was conducted in Lithuania.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The participants of this study did not consent to have their transcripts made publicly available, as they contain personal information which could be used to identify the participants. Therefore, the data is only available internally and interested parties are advised to contact the corresponding author. The authors attest that the interview transcripts contain the information needed to support the findings of the study.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Aušrinė Gribačiauskaitė

Aušrinė Gribačiauskaitė is currently a master’s student of Clinical Health Psychology in the Lithuanian university of Health Sciences, Kaunas, Lithuania. She conducted this study as part of her bachelor’s thesis, titled “Professional becoming of male nurses”. Her main research interests are the experiences of healthcare professionals, societal stereotypes and stigmas, and family dynamics.

Jolanta Žilinskienė

Jolanta Žilinskienė is a medical psychologist, researcher and lecturer at the Lithuanian university of Health Sciences, Kaunas, Lithuania. She obtained a PhD in Biomedical Sciences in 2022 and served as a bachelor’s thesis advisor for Aušrinė Gribačiauskaitė during her studies. Her current focus interests are diabetology, child, couple and family psychology, and the psychological well-being of healthcare professionals.

References

- Abushaikha, L., Mahadeen, A., AbdelKader, R., & Nabolsi, M. (2014). Academic challenges and positive aspects: Perceptions of male nursing students. International Nursing Review, 61(2), 263–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12098

- Al-Momani, M. M. (2017). Difficulties encountered by final-year male nursing students in their internship programmes. The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences: MJMS, 24(4), 30. https://doi.org/10.21315/mjms2017.24.4.4

- Appiah, S., Appiah, E. O., & Lamptey, V. N. (2021). Experiences and motivations of male nurses in a tertiary hospital in Ghana. SAGE Open Nursing, 7, 23779608211044598. https://doi.org/10.1177/23779608211044598

- Arif, S., & Khokhar, S. (2017). A historical glance: Challenges for male nurses. JPMA: The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 67(12), 1889–1894. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29256536/

- Balsienė, D. (2017). Nurses’ self-esteem and job satisfaction interfaces [ master‘s thesis]. Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. https://lsmu.lt/cris/handle/20.500.12512/101832

- Banakhar, M., Bamohrez, M., Alhaddad, R., Youldash, R., Alyafee, R., Sabr, S., Sharif, L., Mahsoon, A., & Alasmee, N. (2021). The journey of Saudi male nurses studying within the nursing profession: A qualitative study. Nursing Reports, 11(4), 832–846. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep11040078

- Blackley, L. S., Morda, R., & Gill, P. R. (2019, October). Stressors and rewards experienced by men in nursing: A qualitative study. Nursing Forum, 54(4), 690–697. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12397

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Carnevale, T., & Priode, K. (2018). “The good ole’girls’ nursing club”: The male student perspective. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 29(3), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659617703163

- Coventry, T. H., Maslin‐Prothero, S. E., & Smith, G. (2015). Organizational impact of nurse supply and workload on nurses continuing professional development opportunities: An integrative review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(12), 2715–2727. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12724

- Cypress, B. S. (2015). Qualitative research: The “what,”“why,”“who,” and “how”! Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 34(6), 356–361. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCC.0000000000000150

- Drennan, V. M., & Ross, F. (2019). Global nurse shortages: The facts, the impact and action for change. British Medical Bulletin, 130(1), 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldz014

- Duchscher, J. B., & Windey, M. (2018). Stages of transition and transition shock. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 34(4), 228–232. https://doi.org/10.1097/NND.0000000000000461

- Evans, J. (2004). Men nurses: A historical and feminist perspective. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 47(3), 321–328. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03096.x

- Glerean, N., Hupli, M., Talman, K., & Haavisto, E. (2017). Young peoples’ perceptions of the nursing profession: An integrative review. Nurse Education Today, 57, 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.07.008

- Guy, M., Hughes, K. A., & Ferris‐Day, P. (2022). Lack of awareness of nursing as a career choice for men: A qualitative descriptive study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78(12), 4190–4198. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15402

- Haahr, A., Norlyk, A., Martinsen, B., & Dreyer, P. (2020). Nurses experiences of ethical dilemmas: A review. Nursing Ethics, 27(1), 258–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733019832941

- Haddad, L. M., Annamaraju, P., & Toney-Butler, T. J. (2022). Nursing shortage. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493175/.

- Halverson, K., Tregunno, D., & Vidjen, I. (2022). Professional Identity Formation: A Concept Analysis. Quality Advancement in Nursing Education-Avancées En Formation Infirmière, 8(4), 7. https://doi.org/10.17483/2368-6669.1328

- Kronsberg, S., Bouret, J. R., & Brett, A. L. (2018). Lived experiences of male nurses: Dire consequences for the nursing profession. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 8(1), 46–53. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v8n1p46

- Labrague, L. J., & McEnroe‐Petitte, D. (2018). Job stress in new nurses during the transition period: An integrative review. International Nursing Review, 65(4), 491–504. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12425

- Lithuanian Department of Statistics. (2015, April 27). Celebrating the day of healthcare professionals. https://osp.stat.gov.lt/informaciniai-pranesimai?eventId=64821

- Lyu, X., Akkadechanunt, T., Soivong, P., Juntasopeepun, P., & Chontawan, R. (2022). A qualitative systematic review on the lived experience of men in nursing. Nursing Open, 9(5), 2263–2276. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.1269

- Mao, A., Cheong, P. L., Van, I. K., & Tam, H. L. (2021). “I am called girl, but that doesn’t matter”-perspectives of male nurses regarding gender-related advantages and disadvantages in professional development. BMC Nursing, 20(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-021-00539-w

- Mao, A., Wang, J., Zhang, Y., Cheong, P. L., Van, I. K., & Tam, H. L. (2020). Male nurses’ dealing with tensions and conflicts with patients and physicians: a theoretically framed analysis. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 13, 1035–1045. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S270113

- McMurry, T. B. (2011). The image of male nurses and nursing leadership mobility. Nursing Forum, 46(1), 22–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6198.2010.00206.x

- Meadus, R. J., & Twomey, J. C. (2011, October). Men student nurses: The nursing education experience. In Nursing forum (Vol. 46, No. 4, pp. 269–279). Blackwell Publishing Inc. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6198.2011.00239.x.

- Meižytė, K., & Blaževičienė, A. (2022). Nurse – patient communication: An exploration of nurses’ experiences. Slauga Mokslas Ir Praktika, Vilnius: Slaugos darbuotojų tobulinimosi ir specializacijos centras, 2022, T. 3, nr. 11(311), https://doi.org/10.47458/Slauga.2022.3.23

- OECD & European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. (2021). Lithuania: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. https://doi.org/10.1787/bc081ccc-lv.

- Petges, N., & Sabio, C. (2020). Perceptions of male students in a baccalaureate nursing program: A qualitative study. Nurse Education in Practice, 48, 102872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102872

- Qureshi, I., Ali, N., & Randhawa, G. (2020). British South Asian male nurses’ views on the barriers and enablers to entering and progressing in nursing careers. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(4), 892–902. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13017

- Rabie, T., Rossouw, L., & Machobane, B. F. (2021). Exploring occupational gender‐role stereotypes of male nurses: A South African study. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 27(3), e12890. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12890

- Rajacich, D., Kane, D., Williston, C., & Cameron, S. (2013). If they do call you a nurse, it is always a “male nurse”: Experiences of men in the nursing profession. Nursing Forum, 48(1), 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12008

- Saleh, M. Y., Al-Amer, R., Al Ashram, S. R., Dawani, H., & Randall, S. (2020). Exploring the lived experience of Jordanian male nurses: A phenomenological study. Nursing Outlook, 68(3), 313–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2019.10.007

- Smith, S. A. (2012). Nurse competence: A concept analysis. International Journal of Nursing Knowledge, 23(3), 172–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2047-3095.2012.01225.x

- Smith, C. M., Lane, S. H., Brackney, D. E., & Horne, C. E. (2020). Role expectations and workplace relations experienced by men in nursing: A qualitative study through an interpretive description lens. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(5), 1211–1220. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14330

- Snyder, K. A. (2011). Insider knowledge and male nurses: how men become registered nurses. Access to Care and Factors That Impact Access, Patients As Partners in Care and Changing Roles of Health Providers, 21–41. https://doi.org/10.1108/s0275-4959(2011)0000029004

- Valizadeh, L., Zamanzadeh, V., Fooladi, M. M., Azadi, A., Negarandeh, R., & Monadi, M. (2014). The image of nursing, as perceived by Iranian male nurses. Nursing & Health Sciences, 16(3), 307–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12101

- Wolfenden, J. (2011). Men in nursing. Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences & Practice, 9(2), 5. https://doi.org/10.46743/1540-580X/2011.1347

- World Health Organization. (2020). State of the world’s nursing 2020: Executive summary. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331673/9789240003293-eng.pdf