Abstract

Purpose

Phenomenology is a branch of philosophy that focuses on human lived experience. Illness including dental diseases can affect this living experience. Within the dental literature, there is very little reported on the use of phenomenology compared to other healthcare sciences. Hence, the aim was to review the literature and provide an overview of various applications of phenomenology in dental research.

Methods

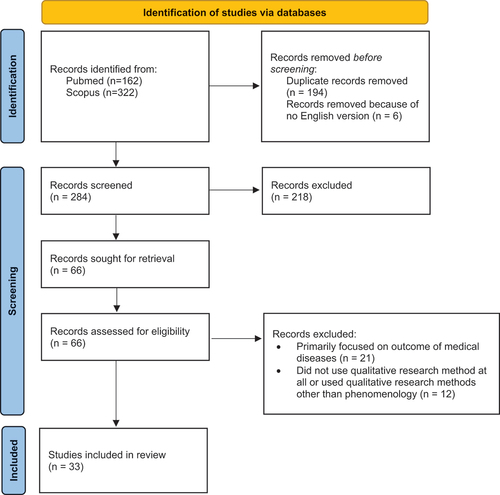

This study was a narrative review using literature in the last 10 years identified by web-based search on PubMed and Scopus using keywords. A total of 33 articles that were closely related to the field and application in dentistry were included. The methodology, main results, and future research recommendations, if applicable, were extracted and reviewed.

Results

The authors in this study had identified several areas such as orofacial pain and pain control research, dental anxiety, dental education, oral healthcare perceptions and access, living with dental diseases and dental treatment experience in which the phenomenological method was used to gain an in-depth understanding of the topic.

Conclusions

There are several advantages of using the phenomenological research method, such as the small sample size needed, the diverse and unique perspective that can be obtained and the ability to improve current understanding, especially from the first-person perspective.

Introduction

Phenomenology is a branch of philosophy that focuses on human lived experience and was aptly defined by Smith as “The study of structures of consciousness as experienced from the first-person point of view” (Smith, Citation2013). Phenomenological research derives its methodology from this philosophy and explores the everyday lived experiences or perceptions of an individual to a specific event and the impact of such phenomena. It is one of the commonly used approaches in qualitative research to try and understand and characterize the universal nature of a phenomenon into themes or central meaning units (Renjith et al., Citation2021; Tuohy et al., Citation2013).

With the emphasis on evidence-based dentistry, researchers in the field of dentistry were inclined to seek factual and numerical answers to clinical and research questions using quantitative research methods which dominated the dental literature (Stewart et al., Citation2008). However, the qualitative research approach can frequently provide new perspectives and interpretations, and allow exploration and explanation of behaviours as well as experiences concerning research questions relevant to dental knowledge and clinical practice (Chai et al., Citation2021). There are a few major types of qualitative research designs, including ethnography, grounded theory, phenomenology, narrative, historical, and case study (Renjith et al., Citation2021).

In the course of life, patients develop oral diseases and undergo dental treatment. However, there can be a vast disparity between experiences of dental-related illnesses and procedures. Phenomenological research is an appropriate and contemporary method to evaluate and describe in depth the unique individual experiences of different persons with regard to dentistry, which are difficult to achieve with other methods. The humanistic approach of phenomenology treats the patient as a person and the essence of their experience is recorded hence is useful when trying to investigate and understand dental research questions not amenable to qualitative methods. Some examples are the personal experience of dental treatment with its accompanying psychological dental anxiety and barriers, living with oral illnesses, or chronic pain which has no obvious pathology like phantom pain (Marbach, Citation1996).

In phenomenology, researchers need to be open to what is given by the participants, “bracket” or remove the presumption of what they already know about the topic, and without questioning the existence of what was collected. Reflective diaries, focus groups and semi-structured interviews are some of the data collection methods. Participants are allowed time to express themselves freely and provide their insight. Usually, open and deepening questions are asked, and checklists are only made to ensure important themes are covered and not to restrict the participants. The important inclusion criteria for participants in the phenomenological study are 1) they have experienced the event and 2) they can describe it in detail. There are many schools of thought on data analysis as well, but most of them involve repeatedly reading the transcribed interviews to get a general thought and then developing a theme or meaning units to form a network of interrelated meanings to the conversations. Different types of phenomenology led by different philosophers exist, and some of the more notable examples of the phenomenological method are the Descriptive Phenomenological Psychological Method (DPPM) by Giorgi and GiorgiJames Morley (Citation2017) or Husserl’s phenomenological reduction method (Beyer, Citation2022).

Phenomenological research is common in the disciplines of philosophy, psychology and education (Renjith et al., Citation2021). Many studies in the medical and nursing field have also used phenomenology, for example in the explanation of the meaning of illness (Beck, Citation1994; Toombs, Citation1987). However, despite its usefulness, there was limited usage of phenomenology in dental research within the dental literature compared to other healthcare sciences. Besides, the quality of dental qualitative research was not adequate overall, reporting only typically moderate (51%) or poor (34%) scores (Al-Moghrabi et al., Citation2019). There were also limited studies in the literature which provide an overview of the applications of phenomenological research in dentistry. Generally, qualitative research topics like phenomenology lend themselves best to a narrative approach. Therefore, the aim of this narrative review was to review the literature and provide an overview of the various applications of phenomenology in dental research. This review paper also offered an introductory description of phenomenology and insights into its appositeness in dental research in the hope of improving interest in this area.

Materials & methods

A web-based search on PubMed and Scopus using the keywords “Phenomenology in Dentistry”, “Phenomenology in Oral Healthcare” and “Phenomenological Research in Dentistry” in the last 10 years from 2013 to 2022 yielded 484 results. 162 and 322 results were retrieved from PubMed and Scopus respectively. 194 duplicate records were first removed. 6 articles without English versions were also removed. Then, the remaining 284 articles were preliminarily screened by the titles and abstracts to remove studies that were not related to dentistry as the patient or population in the studies were primarily concerned with medical illnesses, medical perceptions, and nursing health. The full texts of the remaining 66 studies were retrieved and assessed for eligibility to be included in the review.

The articles were selected with the research objective in mind, which was the application of phenomenological research methods in the field of dentistry and must have strong potential application in dental research. The inclusion criteria for articles were 1) usage of the phenomenological research method, regardless of which schools of thought they belong to, in data collection and analysis of the study, 2) study population relating to dentistry including but not limited to oral diseases, dental treatment, dental education or dental perceptions and 3) written in English or English version of the full text was available. Articles were excluded if they 1) used qualitative research methods other than phenomenology and 2) the primary outcome of the study was not pivoted around dentistry.

As a result, 33 articles that fulfilled the criteria and had pertinent applications in dentistry were finally selected and full articles were studied. The methodology, sampling, main results, implications, and future research recommendations, if applicable, were extracted and reviewed. Meta-analysis was not done for this narrative review.

Results

A total of 33 articles were included in this narrative review study. They were fundamentally categorized based on their application in different aspects of dentistry, focusing largely on the implications of the main results in the study. The overall result is presented in . This provided an overview of the use of phenomenology in dentistry.

Table 1. Results of articles selected categorized based on topics in dentistry and their summary.

The major areas presented were usage in complex conditions like chronic orofacial pain (Hazaveh & Hovey, Citation2018; Lovette et al., Citation2022) and dental anxiety (Murray et al., Citation2019; Schneider et al., Citation2018). Phenomenology was very useful to investigate and describe subjective experiences and emotions that were difficult to quantify. It is shown that the phenomenological research method allows detailed description and profound understanding of chronic pain. The subject suffered various types of loss as a result of chronic pain, having to withstand disbelief among families and communities in the pain reported, and dissatisfaction with their journey through the health care system (Hazaveh & Hovey, Citation2018). This allowed healthcare workers to understand the sufferers, help them feel less lonely and promote empathy among carers. Phenomenological research methodology also helped with the conceptualization of the complex and multifaceted challenges faced by patients with chronic orofacial pain. Therefore, comprehensive consideration and patient-centred care are encouraged in managing this population. On the other hand, a study on dental anxiety inferred that those outcomes obtained from participants with lower anxiety ratings probably acted as protective factors against dental anxiety and facilitated dental attendance, which can be utilized to improve interventions for dental anxiety (Schneider et al., Citation2018). From the perspective of dentists who worked with anxious patients, Murray et al. highlighted the helper-inflictor conflicts faced in the dental profession that have an impact on dentists’ self-image, the need to maintain control, and patients’ perceptions of them, which were seldom considered in published literature (Murray et al., Citation2019).

Besides that, phenomenology also had uses in dental education as well as interprofessional learning and collaboration. To illustrate, Greviana et al. used it to determine factors influencing the underutilization of a novel dental education method, self-reflective e-portfolios, by the students. The results can assist educators in providing recommendations for the improvement of any new teaching methods and their implementation in dental school (Greviana et al., Citation2020). The phenomenological research process should not be considered inferior to traditional quantitative methods. Rich and in-depth individual points of view were able to be explored to shed light on issues in dental education with greater clarity. In another study, Koch et al. used the phenomenological method to reveal the perceived requirements for achieving successful change in endodontic practice, which were clinical relevance, conducive environment for discussion, allowance for individual learning patterns, competence of educator and familiarity with conditions at the dental clinics (Koch et al., Citation2014). Reeson et al. interviewed mixed groups of dental students and trainee dental technicians and found key themes such as apprehension and awkwardness; the growth of the dental team; worries about patient care (Reeson et al., Citation2013). The complex interrelationship in interprofessional collaboration was able to be identified and potentially utilized for successful teamwork in a multi-professional clinical practice. Meanwhile, phenomenological study was also used to explore the influences on dentists’ health and well-being, which have serious public health implications. Acknowledging the negative influences can facilitate policymakers to perceive elements like being able to deliver quality care, innovate and effect change, as well as being valued for their delivery can help contribute to the well-being (Gallagher et al., Citation2021).

Additionally, phenomenology has been used to look into oral health perceptions and barriers to oral healthcare access in various populations. Older people adapted to their changing oral health and it represented their lifetime’s investment in oral care (Gibson et al., Citation2019). School children did not have enough knowledge on the importance of oral health and even then, knowing the methods to prevent dental caries cannot influence the behaviour (Abedi et al., Citation2013). Among schoolteachers, the perceived barriers to dental service delivery were “lack of awareness” followed by “financial barriers” (Mohanty et al., Citation2021). The results from these studies suggested a crucial need for oral health education programs to change the current scenario and regular oral and health training programs among students. The interesting study by Tynan et al. also highlighted that although the indigenous community placed a high priority on oral health, the burden of oral diseases was high and uptake of oral health services was low (Tynan et al., Citation2020). Through qualitative investigations like this, the researchers showed that priority given to a disease may be affected by multiple reasons other than simply the pathology of the disease and there were barriers to accessing oral healthcare instead of lack of awareness. Investigations on barriers to oral healthcare utilization found factors like inconsistencies in advice across professions concerning the appropriate age of registration and childhood dental fears and anxiety with lasting impact on some mothers may influence their decision resulting in children being denied early access to dentists (Dickson, Citation2015). In the elderly, themes emerged in four major areas: 1) general awareness of oral health, 2) life course perspective of oral health, 3) barriers to visiting the dentist, and 4) shaping dental service adoption behaviours by financial aid. Moreover, trust, convenience, fear, anxiety, previous negative experiences, and lack of knowledge influenced dental visit decisions in this population (Mittal et al., Citation2019). On the other hand, stakeholders in The University of British Columbia (UBC) Dental Hygiene Degree community-based program appropriately used the phenomenological method to evaluate and conclude that a positive influence on access to oral health care for members with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was achieved. The study found that members who had past traumatic experiences were appreciative of the services delivered safely and stigma-free, and they valued the opportunity to educate dental professionals to reduce HIV-related stigma. However, some members continued to face barriers to care at referral clinics for dental needs that could not be treated in the program (Feng et al., Citation2020). Other studies interviewed oral healthcare policymakers. In a welfare state, the researchers found dentistry as a free market represented a compromise between two very distinctive political ideologies (Franzon et al., Citation2018), while in a low-income country, phenomenological studies offered important insights into the delivery of dental care and challenges in the delivery of dental care. The latter study found a clear consensus that a high level of oral health needs was unmet. Challenges of dental care delivery revolved around five themes: 1) patients’ predisposition for traditional remedies; 2) practical hindrances; 3) professional isolation and weak governance; 4) pressing local crises and 5) lack of political will. While typology of dental professionals included: 1) loyalty; 2) resilience; 3) embracing opportunity; 4) striving to serve the population (Ghotane et al., Citation2019). With this information at hand, the study can provide a vision for developing, building and retaining future human resources for oral health.

Last but not least, researchers found highly beneficial usage of phenomenology in oral diseases and dental treatments. Five themes emerged from the interview data with oral cancer patients: 1) the psychological journey in facing oral cancer, 2) the question of how patients can control their disease as well as the sequelae of cancer treatment, 3) the continuous disturbance and turmoil resulting from the disease, 4) the appreciation of the support from family and friends, and 5) the ability to learn to actively face the future (Cheng et al., Citation2013). This study may serve as a reference for improving clinical practice and the quality of care among oral cancer patients as cancer care should be multidimensional and holistic. Healthcare professionals should help patients receive complete medical care and support as their treatment progresses to help patients face the challenges of cancer. The analysis in cleft lip and palate (CL/P) patients resulted in five themes: 1) cleft across the lifespan, 2) keeping up appearances, 3) being one of a kind, 4) resilience and protection, and 5) cleft in an ever-changing society. It was found that CL/P had ongoing impacts, particularly in some aspects of participants’ lives. Participants seemed at ease living with CL/P as an older adult and considered it an important aspect of their identity, yet they still felt isolated at times. They felt that health and dental care could be more considerate of the needs of older people with cleft (Hamlet & Harcourt, Citation2015). The findings from the lived experience of CL/P patients had implications for the provision of care and information for older CL/P adults as well as for younger CL/P patients who will become the older generation in the future. In people who had lost their teeth, a phenomenological study found that losing teeth was a subjective experience with heterogeneous narratives and highlighted the important social aspect of the mouth. The number of missing teeth and the understanding of how people perceived themselves without their teeth determined how much tooth loss affected their lives while wearing prostheses adds significance to individuals’ perceptions of their bodies (Bitencourt et al., Citation2019). Researchers identified three common themes in patients suffering from chronic temporomandibular joint disorders (TMD): 1) constipation and bloating, 2) loss of chewing function and 3) weight change, which had physiologic and psychologic complications and were largely unaddressed by their doctors (Safour & Hovey, Citation2019). The study highlighted that TMD patients are at risk of malnutrition and healthcare providers should establish nutritional guidelines to reduce comorbidities and better assist these patients. In parents of children with CL/P, qualitative analysis of the interviews yielded three main themes including fatigue (exhaustion, helplessness, and incompetence), self-reliance (mutual support and empathy), and the need for social support (counselling services and citizenship rights) (Imani et al., Citation2021). Results of the study were able to reveal that parents of children with CL/P are vulnerable due to their previous adverse experiences with the treatment of their children and that they need support in several physical, psychological, social and spiritual domains. These should all be considered in the holistic care of CL/P patients. Parents of children with premature loss of deciduous teeth found that losing the teeth brought functional limitations with chewing and speaking, impairments of social interaction with other children, repercussions on the child’s image, and changes in families’ daily lives, although early tooth loss by extraction due to pain was perceived as “commonplace” in children’s lives by the caregivers (Bitencourt et al., Citation2021).

Phenomenological studies on patients who underwent treatment for dental diseases often can reveal the extremely complex pattern of interconnected external and internal components in individual perspectives and lived experiences of improved oral health-related aspects. Interviews with subjects who had periodontal treatment described the patient-centred perspective held together by eight constituents: 1) change is increased successively, 2) a changed view on self-care at the start of change, 3) improved self-care includes understanding and automatic routine, 4) motivating challenges and feedback are perceived as strengthening, 5) having good thoughts and being satisfied with one’s own capacity, 6) experiencing trust and participation along with an expert, 7) negative experiences and limitations precedes the change, and 8) relating yourself to past time, present time, future and other people (Östergård et al., Citation2016). The results thence called for the need for a holistic perspective of the positive change process and for the clinician to practise flexibility in periodontal treatments. In patients who had life-changing orthognathic surgery, the following themes were identified: the overall journey of treatment being a rite of passage; the treatment’s role in raising awareness about anomalies in appearance; the initial shock at the changes that followed surgery; the uncertainty about treatment; the impact of actual negative reactions of others; and the role of significant others in the decision-making process (Liddle et al., Citation2018). This phenomenological study allowed participants to describe a much more complex process of adjustment to change in appearance than had been reported elsewhere in the literature. The study also highlighted both medical and parental communication influence patient expectations and experience of surgery. Six key themes were presented in patients who suffered inferior alveolar nerve injury due to dental treatments: 1) personal impact and change in self-perception, 2) impact on relationships, 3) impact on oral health care, 4) adjustment to the injury over time, 5) change in how they perceived dentists, and 6) changes they would make in the dental care system (Barker et al., Citation2019). The phenomenological methods in this study afforded insight into the significant psychological impact and different perspectives other than objective signs of trigeminal nerve injury and subsequently should improve patient care. Meanwhile, in patients who had oral cancer surgery, two overarching themes were discovered: “I never dreamt” and “They look at you, and they speak to you.” The first theme revolved around there was no way for patients to be adequately prepared for the enormity of the surgery and its consequences; however, the second theme was the way healthcare professionals interacted and communicated with the person was healing and therapeutic (Dawson et al., Citation2019). Similarly for patients who had radiotherapy for their cancer, the analysis of data generated four main categories: pain, nutritional consequence, barriers in communication and support system which showed the multifaceted experience of patients undergoing radiotherapy (Kanchan et al., Citation2019). The phenomenological studies in patients with oral cancer unveiled genuine and meaningful feelings which were otherwise hard to imagine by healthcare workers. It allowed the understanding of the specific issues and challenges faced by oral cancer patients. Hence, based on the results of these studies, the authors fittingly recommended there was a need for novel ways to prepare patients for HNC surgery and to support them in recovery, including ways to connect and help patients feel human again and interprofessional collaboration towards achieving the common goal of restoring patients’ health and improving health outcomes. A phenomenological study on patients who had treatment for oligodontia revealed the following themes: “feeling of being different”, “the burden of treatment”, “shared decision making”, “treatment increases self-esteem” and “use of coping strategies” (Saltnes et al., Citation2019). These had important relationships to QoL and psychological distress. The results should be acknowledged by healthcare personnel when planning and treating the oligodontia population. Adult CL/P patients who had the course of treatment were found to be very aware of their bodily differences. The possible adverse reactions from peers early in life negatively affected their social life. Factors like self-confidence, cleverness, being physically fit, and having trusted friends were barriers against teasing and bullying. Nevertheless, reflected images remind them of the objectifying looks from society and often lead to bodily adjustments. The treatment course was not questioned, and they accepted the treatment decisions made by experts and parents. Although problems related to the cleft could persist or return after ordinary treatment, they were typically more hesitant to additional surgery in adulthood (Moi et al., Citation2020). Through systematic and meticulous phenomenological research method, the study concluded that CL/P was found to have been an unquestioned part of the participants’ childhood, and a burden that they feared would, to some extent, also be passed to their children. Fortunately, it seemed that CL/P had not prevented them from achieving goals and satisfaction in life. The authors advocated the need for personalized, lifelong, and multidisciplinary care and follow-up for CL/P patients keeping in view the persisting psychological, functional, and esthetic challenges they face. In tobacco cessation attempts, three key themes were extracted: barriers to quitting smoking, reasons for quit attempts, and how to quit. Unsuccessful attempts were related to tobacco addiction and successful attempts were based on the need to improve one’s health and family (Gill et al., Citation2021). The phenomenological study found that psychological support is important in successful quit-smoking attempts. Thence, the authors implicated that treatment providers should encourage behaviour change via intrinsic goals which have a long term and positive impact.

There were other minor applications of phenomenology. For instance, a phenomenological study on the impact of pregnancy on women’s OHRQoL was condensed into three major themes and six sub-themes which covered daily life, psychological well-being, social life, physical impact, and barriers to utilization of dental care services. The study found new domains like “dentists’ refusal to treat pregnant women”, “negative feelings about pregnancy” and “concerns about foetal health” which were important factors that could influence the OHRQoL (Fakheran et al., Citation2020). The findings from this phenomenological study helped to better understand the oral health issues impacting pregnant women and can be decisive in achieving person-centred care. The conceptual framework created based on the results of this study may help healthcare workers and policymakers improve the health of pregnant women. Indian female dentists were interviewed and five themes were identified: 1) Striking work-family balance, 2) Dependence on male authority for instating work discipline, 3) Male dentists’ hostility to the “woman in power” concept, 4) Male dentists’ superiority in technical skills, and 5) privileges for women dentists (Iyer et al., Citation2020). This phenomenological work revealed a need to improve the work environment for female dentists in India through strong social support, sensitivity among male colleagues, and generous institutional policies to enable the increased contribution of women to the profession.

Discussion

This article identified several areas where the phenomenological method had been proven useful in the field of dentistry.

Chronic orofacial pain

The first part of the definition of pain by The International Association for the Study of Pain states that it is “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with … ”. Hence, there is no better way to delve in-depth into pain study than allowing subjects to express this sensory and emotional experience that they have. A study by Ojala et al. was a good example of studying chronic pain using phenomenology (Ojala et al., Citation2015). Chronic pain can often be regarded as imaginary, especially when there is no obvious pathology. In the study, guided by the phenomenological method, they demonstrated through detailed description that chronic pain was invisible to healers but it was very real to the sufferers. They found that clinical practice often lacked insight during treatment despite the recommendation for holistic treatment which includes a biopsychosocial approach for such patients.

The same approach was successfully applied in dentistry by an old study. Phantom pain being an enigma in clinical dentistry has long puzzled dentists and researchers alike. As phantom pain cannot be diagnosed from any signs or obvious pathology, it can only be studied through phenomenology in which the description of the pain should be open and unrestricted, the existence not questioned and accepted by researchers (Marbach, Citation1996). Besides that, due to the lack of diagnostic aids and biomarkers for orofacial pain conditions, phenomenology was also used to help classify orofacial pain disorders (Ceusters et al., Citation2016). This was not new, as phenomenology was used to classify other diseases like dystonia, seizures or movement disorders that could represent different phenotypes based on patients’ narratives (Defazio et al., Citation2017; Freitas et al., Citation2019).

Commonly, the Pain Visual Analog Scale is a tool widely used to describe pain in clinical settings. However, it is extremely simplified and one-dimensional. Pain is often a complex phenomenon with very subjective experience. Qualitative studies explored the experience of subjects living with orofacial pain. The researchers found many profound and unique perspectives when the phenomenological method was employed instead of questionnaires and surveys. Additionally, the subjects were also found to be dissatisfied with the healthcare system. Undoubtedly, quantitative and biomedical aspects of pain are essential to report but the experience of living with chronic pain should also not be overlooked. Therefore, phenomenological study as such can reveal an abundant amount of information to researchers, especially on a complex topic like pain. This may further help clinicians understand the impact and consequences of living with chronic orofacial pain, develop empathy that may improve the clinician–patient relationship and come up with a more holistic approach to handling patients with chronic orofacial pain (Hazaveh & Hovey, Citation2018; Lovette et al., Citation2022).

Future research on oral diseases with complex and multidimensional biopsychological components and with almost no obvious physical pathology or signs, such as burning mouth syndrome, atypical facial pain and temporomandibular myofascial pain syndrome using the phenomenological approach will benefit the field. After all, understanding the patients deep down and tackling their challenges may be key to the successful management of these patients holistically.

Dealing with dental anxiety

There are always many subjective feelings and emotions when it comes to dental anxiety which are not easy to explain and classify quantitatively. Schneider et al. studied the relationship between the content of dental-related-imaging cognitions and the resulting severity of dental anxiety. The data were collected using the phenomenological method of in-depth semi-structured interviews and consequently, several themes were discovered (Schneider et al., Citation2018). Their study demonstrated a positive relationship and provided the foundation for positive imagery techniques to be used to tackle dental anxiety, considering that one of the causes that affect the level of dental anxiety was found. As we work hard to understand the causes of dental anxiety wholly, we can tackle the phenomena better.

In another study, the experiences of dentists based in specialist settings when they are dealing with dentally anxious patients were explored (Murray et al., Citation2019). Phenomenology allows valuable experiences like this to be documented and shared which led to a deeper understanding of how dentists evaluate their work with anxious patients and their environment. Future work can be done in this area to explore novel and additional reasons for dental fear or phobia in this group of patients, which might be previously unbeknown to the dental community, other than the traditional blood-needle-injury phobia. Realizing and removing the triggers will help the dental community to work together to tackle one of the biggest barriers to oral healthcare—dental anxiety.

Dental education

The use of phenomenology in developing a better understanding and curriculum for education has already been widely utilized and well-reported in the medical field and allied health sciences. There were already numerous such studies in the field of nursing, radiographers and medical practitioners (Brown et al., Citation2021; Kinsella & Bidinosti, Citation2016; Page et al., Citation2014; Palmaria et al., Citation2020; Paul et al., Citation2020; Thomson et al., Citation2017).

Thomson et al. studied the experience of nursing students and found several themes, like “support” and “anticipatory anxiety” which contributed to the negative experience of being a nurse (Thomson et al., Citation2017). Dentistry as a profession has one of the highest suicide rates and future phenomenological research can be done on dental students and dentists to help understand them psychologically since there must exist a lot of stress and anxiety as well. One publication probed into the health and well-being of dentists in England and found that more support was needed for dentists (Gallagher et al., Citation2021; Hawton et al., Citation2011). Another study used reflective diaries in addition to interviews and focus groups to understand interactions during interprofessional learning in a trainee dental team (Reeson et al., Citation2013). All these phenomenological methodologies allowed the researchers to obtain an in-depth understanding of the effect of dental education policies and their practical challenges. New elements or factors which had never arisen in other studies can often be found when participants can express themselves freely. This undoubtedly contributes to our knowledge and helps with the development of new approaches for a better dental curriculum and education.

Phenomenological research in dental education was not only applicable in undergraduate but dental practice as well. A study in Sweden used the phenomenological method to determine the requirements for a successful change in endodontic practice after an educational intervention by the Public Dental Service (Koch et al., Citation2014). This study was a great example of using phenomenology as a pilot interview to easily explore and obtain factors or themes that had never been reported. In addition, phenomenology as a research method allows a huge amount of data to be collected from a small sample size due to the sharing of the rich experience of the participants.

With the rapid transformation of information technology, innovative methods of knowledge sharing, and novel techniques coming to light on a quick basis, dental education is experiencing a faster-than-ever change. Phenomenology can be helpful to catch on to the line of thoughts of newer generation dental students. Recognizing their preference and what works best for them can guide dental educators to adapt, evolve and transform teaching to be more effective. Putting it all together, phenomenology may well be very useful in understanding and guiding directions of dental education.

Oral Health Perception

Phenomenology has been prevalently used in the medical field, education and human sciences to obtain perceptions of physicians and carers in performing various duties (Gillespie et al., Citation2018; Kelly et al., Citation2019; Mabood et al., Citation2013; Quigley et al., Citation2022; Santos Salas et al., Citation2019). Phenomenology provided great insight into the complex, subjective and unique experiences happening in their daily job through observation, dialogue and conversation.

Multiple studies explored the oral health perception of some of the population like school children (Abedi et al., Citation2013), geriatric population (Gibson et al., Citation2019), aborigins in rural areas (Tynan et al., Citation2020), and schoolteachers (Mohanty et al., Citation2021). Important factors that hinder the utilization of oral healthcare were revealed. Besides, true knowledge and perceptions of the studied population about oral health and certain common themes were unfolded when in-depth interviews and focus groups were done.

Future phenomenological research that focuses on obtaining perceptions of the population can allow an understanding of these perceptions, and possibly unravel what is missing or lacking. Factors like awareness, financial barriers, cultures, etc., have been suggested but it seems that a deeper exploration can be done. Future studies can also investigate the perception towards dentists, dental treatments and oral health programs. The results from these studies can provide valuable insight and factors to stakeholders which should be considered in future health policies. Ultimately it will help public health dentists and lobbyists develop effective and well-founded strategies for improving the oral healthcare system as a whole.

Evaluate barriers to oral healthcare access

Phenomenology has great application in the Public Health sector. Access to healthcare and telehealth has been investigated by using phenomenology (Freeman et al., Citation2013; Greenhalgh et al., Citation2013). Diverse but unique views of participants can be obtained whether they are positive or negative about the topic.

Similarly, barriers and access to oral healthcare have been explored in certain populations like old people (Mittal et al., Citation2019) and HIV patients (Feng et al., Citation2020) using phenomenology. Emerging themes that were obtained from these studies, for example past negative experiences, stigma, fear, anxiety, lack of knowledge, etc., can then be looked into in future phenomenological research and serve as the starting point when the stakeholders are looking for ways to improve the access of these populations to the oral healthcare that they deserve. Researchers can identify the correct reasons for the non-utilization of dental services and may clear the way for the adoption of dental services in the population studied. Phenomenological study can also serve as a baseline for future studies for countries that implemented schemes for older adults because phenomenological research gives valuable insights regarding oral health perceptions and beliefs of older people which may affect their dental service utilization. Understanding their concerns may be key to breaking down barriers to the utilization of dental healthcare in this population.

On the other hand, some publications put phenomenology into use by obtaining perceptions of oral healthcare policymakers and dentists striving for the improvement of oral health of the community they serve (Franzon et al., Citation2018; Ghotane et al., Citation2019). Instead of the receivers, the perceptions of the givers were unveiled. This allowed in-depth exploration of the participants psychologically and granted researchers the rationale behind certain decisions in policymaking. The inferences from these studies might be able to open debates and possibilities to lead the way for policymakers to address any functionally declining public general health care system and improve access to the citizens.

Along those lines, future studies should attempt to recognize roadblocks to oral healthcare in additional populations like war refugees, special needs, institutionalized, medically compromised patients, etc., as the obstacles may be different in each population. The findings can foster public health services to try and address the local barriers.

Dental and oral diseases

Phenomenology was used in disease research as well. A rich understanding of patients living with severe diseases such as incurable illness, HIV and Parkinson’s disease can be obtained [63–65]. The themes obtained from phenomenology research can then be investigated to help these patients cope with the diseases. It was a strength of the study when the phenomenological method was used in disease research because of the extensive information that can be obtained in the study (Martino et al., Citation2012).

In dentistry, phenomenology was also used to understand illness cleft lip/palate (Hamlet & Harcourt, Citation2015; Moi et al., Citation2020), the traumatic experience of tooth loss (Bitencourt et al., Citation2019), and temporomandibular joint disorders (Safour & Hovey, Citation2019) While phenomenology cannot replace the traditional definition of dental diseases, it provides another way to understand the disease, especially from the patient’s point of view that will aid practitioners in handling the problems more ethically and empathetically during treatment. In the literature, there were abundant reports on the effect of dental diseases on quality of life and physical health, but phenomenology allowed participants to openly share their thoughts and firsthand life experiences that provided further insight into the disease, especially psycho-sociologically. Phenomenology also allowed the sufferers of diseases to share their experiences with the world. Qualitative approach studies, especially in health services should be considered to better plan healthcare which prioritizes people’s individual needs in their own territories, thus reducing stigmas and social inequalities.

Other than trying to understand the person suffering from the diseases, in some publications, the researchers used the phenomenological method to obtain and understand the perceptions and experiences of the carers/parents of children suffering from dental diseases [33. 34]. The study was able to deduce that the caregivers’ understanding of how children see themselves in their social world had an impact on how much oral diseases affect their lives owing to the qualitative nature of the design. The authors also recommended that caregivers’ perceptions should be included in oral health promotion program strategies.

In future research, other debilitating diseases with a huge impact on patients’ lives and oral healthcare should also be investigated by using the phenomenological method, such as orofacial syndromes, cerebral palsy, post-stroke, etc. Eventually, the diseases can then be understood from the perspective of the subjects or carers instead of the clinicians. This can then help researchers plan interventions based on the people’s needs and improve the quality of life where it matters.

Dental treatment or intervention

Phenomenology has been used as a method to write up a case report of a patient adapting to life after major weight loss following bariatric surgery (Natvik et al., Citation2019). In the field of dentistry, phenomenology was likewise used to investigate the individual experience of patients who had undergone dental treatment like periodontal treatment (Östergård et al., Citation2016). The use of phenomenology to study the patient-reported outcome of having a dental treatment was a great strength of the study because no one can describe the impact and experience of the treatments better than the patients themselves.

Some studies followed subjects who had swallowing therapy following surgery for oral cancer (Dawson et al., Citation2019), radiotherapy for oral cancer (Kanchan et al., Citation2019), oral rehabilitation in patients with oligodontia (Saltnes et al., Citation2019), and cleft lip/palate treatment (Moi et al., Citation2020). The use of the phenomenological method in these studies permitted participants to deeply describe the experience of living with threatening diseases like oral cancer and therefore allowed an in-depth understanding of the disease and the ability to provide treatment with empathy.

Intralveolar nerve (IAN) damage is a rare but known complication of lower third molar surgical extraction. A phenomenological study of patients who suffered from iatrogenic IAN damage provided insight into the impact of the complication (Barker et al., Citation2019). This knowledge undoubtedly could help clinicians when explaining informed consent and answering patients’ questions before performing the surgical extraction of wisdom teeth. It could also help to provide support for patients suffering from the complications. There is a great need to improve communication between clinicians, families, and patients.

As healthcare workers are beginning to realize the importance of patients’ perceptions and experiences which can impact the success rate of treatment, the ability to inform and prepare patients on what to expect in the course of treatment has become an imperative part of obtaining informed consent. This is especially true, for example in disciplines like orthodontics, where patient cooperation and motivation can determine the success of the treatment. Phenomenological research in dental treatments can guide dentists to provide sound and evidence-based information to new patients based on the lived experiences of previous patients, especially if the operator has never had the treatment done before. Future research recommendations include determining important feelings and experiences of various complex dental treatments to improve clinicians’ empathy towards the patients and increase satisfaction with dental treatments.

Other applications

Other publications explored different topics in dentistry using the phenomenological method like the impact of pregnancy on oral health quality of life (Fakheran et al., Citation2020) and gender disparity among female dentists in India (Iyer et al., Citation2020). This goes to show that the phenomenological method can be utilized in future research in a wide area including various stages of learning in dentistry and patient treatment areas.

Implications and future potential areas of research recommendation

Resultant themes that emerged from the publications included in this study can be capitalized on to better understand the central issues surrounding dentistry. For instance, understanding the challenges faced by patients can help oral healthcare workers implement changes accordingly to improve patient care. Also, well-being encompasses themes like quality of life, mental health, and self-interest, among other things. There were limited studies that investigated the relationship of mental health and self-interest on oral health qualitatively and more research could be done in this area.

Furthermore, the authors think that there are also potential applications of phenomenology in future research for other experiences in dentistry, for example in the field of pain control procedures like conscious sedation, hypnosis, acupuncture, etc. The description of patients’ feelings under these procedures has always been ambiguous and theoretical. Therefore, qualitative research in these areas will provide great insight into what the patients really feel during the procedures and help clinicians in decision-making, as well as developing empathy. All in all, qualitative research and phenomenology still have huge potential applications in many aspects of dental research. Consider the several diseases suggested in this text, which still have limited studies using phenomenology in the literature.

Limitations

Keeping up with the nature of the study being a narrative review, no meta-analysis or quality analysis of studies was done. Secondly, this study aimed to explore and broadly describe phenomenology and the use of phenomenological methodology in dentistry, hence the publications included do not have a standardized methodology or belong to the same school of thought.

Conclusion

Phenomenology as a qualitative research method is underutilized in dentistry research. There are several advantages of using the phenomenological research method in the field of dentistry. Only a small sample size is needed to yield a copious amount of data, unique and diverse perspectives and information that had never arisen before can be obtained, and deep insights into subjective topics that cannot be easily quantified can be gained and become the strength of a study. The aim of this study was achieved as the authors had successfully identified and discussed several areas such as orofacial pain and pain control research, dental anxiety, dental education, oral healthcare perceptions and access, living with dental diseases and dental treatment experiences. Future phenomenology research can surely improve the current understanding and contribute to the existing knowledge, especially from the first-person perspective.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ramprasad Vasthare

Ramprasad Vasthare, MDS Professor and Head, Dept of Public Health Dentistry, Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal. Faculty Advisor at Manipal FAIMER International institute for leadership in Inter Professional Education, (MFIILIPE), MAHE. PhD guide for ICMR-NCS scheme. Areas of Interest: Geriatric Oral health, Tobacco Cessation, Epidemiology, Nutrition, Research Methodology, Behavioral Sciences, Ethics, Dental Education. Areas of Expertise: Tobacco Cessation, Bioethics, Interprofessional / interdisciplinary projects. Areas of Research: Dental Educational Environment, Nicotine dependence assessment, Population studies - needs and rehabilitation, Geriatric oral health, Tobacco Cessation. Total publications: 20

Arron Lim Y R

Arron Lim Y R, BDS (MDS) Senior Resident, Department of Orthodontics, National University of Malaysia, Malaysia. Has published: Mohammed, C. A., Narsipur, S., Vasthare, R., Singla, N., Yan Ran, A. L., $ Suryanarayana, J. P. (2021). Attitude towards shared learning activities and interprofessional education among dental students in south india. European Journal of Dental Education, 25(1), 159-167. doi:10.1111/eje.12586

Aayushi Bagga

Aayushi Bagga, BDS (MPH) Is a Graduate student in Master of Public Health, The University of Melbourne, Australia.

Prajna P. Nayak

Prajna P Nayak, MDS Associate Professor, Department of Public Health Dentistry, Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education. Areas of Interest: Epidemiology; Health informatics, Qualitative studies. Areas of Expertise: Oral Epidemiology, interprofessional education. Areas of Research: Clinical trials; Spatial epidemiology and geo-mapping. Total publications: 23

Bhargav Bhat

Bhargav Bhat, (MDS) is a Post Graduate student, Dept of Public Health Dentistry, Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal.

Sahana S

Sahana S, BDS Is a Tutor, Dept of Public Health Dentistry, Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Udupi, Karnataka, India.

References

- Abedi, G., Rostami, F., & Eftekhari, S. (2013). Phenomenology of students’ perception and behavior on oral and tooth health. International Journal of Collaborative Research on Internal Medicine & Public Health, 5(4).

- Al-Moghrabi, D., Tsichlaki, A., Alkadi, S., & Fleming, P. S. (2019, May 1). How well are dental qualitative studies involving interviews and focus groups reported? Journal of Dentistry, 84, 44–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2019.03.001

- Barker, S., Renton, T., & Ormrod, S. (2019, May 1). A qualitative study to assess the impact of iatrogenic trigeminal nerve injury. Journal of Oral and Facial Pain and Headache, 33(2), 153–159. https://doi.org/10.11607/ofph.2054

- Beck, C. T. (1994). Phenomenology: Its use in nursing research. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 31(6), 499–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7489(94)90060-4

- Beyer, C. (2022). “Edmund husserl”, the stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (winter 2022 ed).

- Bitencourt, F. V., Corrêa, H. W., & Toassi, R. F. C. (2019). Tooth loss experiences in adult and elderly users of primary health care. Experiências de perda dentária em usuários adultos e idosos da Atenção Primária à Saúde. Ciencia & Saude Coletiva, 24(1), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232018241.09252017

- Bitencourt, F. V., Rodrigues, J. A., & Toassi, R. F. (2021, April 26). Narratives about a stigma: Attributing meaning to the early loss of deciduous teeth on children’s caregivers. Brazilian Oral Research, 35. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-3107bor-2021.vol35.0044

- Brown, M. E., Proudfoot, A., Mayat, N. Y., & Finn, G. M. (2021, October). A phenomenological study of new doctors’ transition to practice, utilising participant-voiced poetry. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 26(4), 1229–1253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-021-10046-x

- Ceusters, W., Raphael, K. G., Raphael, K. G., Durham, J., & Ohrbach, R. (2016). Perspectives on next steps in classification of oro-facial pain – part 1: Role of ontology. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 42(12), 926–941. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12336.Perspectives

- Chai, H. H., Gao, S. S., Chen, K. J., Duangthip, D., Lo, E. C. M., & Chu, C. H. (2021). A concise review on qualitative research in dentistry. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 942. Retrieved January 22, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030942

- Cheng, C. H., Wang, T. J., Lin, Y. P., Lin, H. R., Hu, W. Y., Wung, S. H., & Liang, S. Y.(2013). The illness experience of middle-aged men with oral cancer. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(23–24), 3549–3556. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12455

- Dawson, C., Adams, J., & Fenlon, D. (2019, November 1). The experiences of people who receive swallow therapy after surgical treatment of head and neck cancer. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology, 128(5), 456–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oooo.2019.03.012

- Defazio, G., Esposito, M., Abbruzzese, G., Scaglione, C. L., Fabbrini, G., Ferrazzano, G., Peluso, S., Pellicciari, R., Gigante, A. F., Cossu, G., Arca, R., Avanzino, L., Bono, F., Mazza, M. R., Bertolasi, L., Bacchin, R., Eleopra, R., Lettieri, C., Morgante, F., Altavista M. C., … Girlanda, P. (2017, May). The Italian dystonia registry: Rationale, design and preliminary findings. Neurological Sciences, 38(5), 819–825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-017-2839-3

- Dickson, C. M. (2015). Every child has the right to smile!–A qualitative study exploring barriers to dental registration in a SureStart area in Northern Ireland. Community Practitioner: The Journal of the Community Practitioners’ & Health Visitors’ Association, 88(8), 36–41.

- Fakheran, O., Keyvanara, M., Saied-Moallemi, Z., & Khademi, A. (2020, December). The impact of pregnancy on women’s oral health-related quality of life: A qualitative investigation. BioMed Central Oral Health, 20(1), 1–1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-020-01290-5

- Feng, I., Brondani, M., Bedos, C., & Donnelly, L. (2020, February). Access to oral health care for people living with HIV/AIDS attending a community-based program. Canadian Journal of Dental Hygiene, 54(1), 7.

- Franzon, B., Englander, M., Axtelius, B., & Klinge, B. (2018, January 1). Dentistry as a free market in the context of leading policymaking. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 13(1), 1484218. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2018.1484218

- Freeman, T., Brown, J. B., Reid, G., Stewart, M., Thind, A., & Vingilis, E. (2013, April 1). Patients’ perceptions on losing access to FPs: Qualitative study. Canadian Family Physician, 59(4), e195–201. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1314

- Freitas, M. E., Ruiz-Lopez, M., Dalmau, J., Erro, R., Privitera, M., Andrade, D., & Fasano, A. (2019, August 1). Seizures and movement disorders: Phenomenology, diagnostic challenges and therapeutic approaches. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 90(8), 920–928. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2018-320039

- Gallagher, J. E., Colonio-Salazar, F. B., & White, S. (2021, July 20). Supporting dentists’ health and wellbeing-a qualitative study of coping strategies in’normal times’. British Dental Journal, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-021-3205-7

- Ghotane, S. G., Challacombe, S. J., & Gallagher, J. E. (2019, May 13). Fortitude and resilience in service of the population: A case study of dental professionals striving for health in Sierra Leone. BDJ Open, 5(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41405-019-0011-2

- Gibson, B. J., Kettle, J. E., Robinson, P. G., Walls, A., & Warren, L. (2019, March). Oral care as a life course project: A qualitative grounded theory study. Gerodontology, 36(1), 8–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/ger.12372

- Gillespie, H., Kelly, M., Gormley, G., King, N., Gilliland, D., & Dornan, T. (2018, October). How can tomorrow’s doctors be more caring? A phenomenological investigation. Medical Education, 52(10), 1052–1063. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13684

- Gill, K. K., van der Moolen, S., & Bilal, S. (2021, December 1). Phenomenological insight into the motivation to quit smoking. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 131, 108583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108583

- Giorgi, A., & GiorgiJames Morley, B. (2017). The descriptive phenomenological psychological method. In The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology (Vol. 55, pp. 176–192). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526405555.

- Greenhalgh, T., Wherton, J., Sugarhood, P., Hinder, S., Procter, R., & Stones, R. (2013, Sepember 1). What matters to older people with assisted living needs? A phenomenological analysis of the use and non-use of telehealth and telecare. Social Science & Medicine, 93, 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.05.036

- Greviana, N., Mustika, R., & Soemantri, D. (2020, May). Development of e‐portfolio in undergraduate clinical dentistry: How trainees select and reflect on evidence. European Journal of Dental Education, 24(2), 320–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12502

- Hamlet, C., & Harcourt, D. (2015). Older adults’ experiences of living with cleft lip and palate: A qualitative study exploring aging and appearance. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal: Official Publication of the American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association, 52(2), e32–e40. https://doi.org/10.1597/13-308

- Hawton, K., Agerbo, E., Simkin, S., Platt, B., & Mellanby, R. J. (2011, November 1) Risk of suicide in medical and related occupational groups: A national study based on Danish case population-based registers. Journal of Affective Disorders, 134(1–3), 320–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.044

- Hazaveh, M., & Hovey, R. (2018, July). Patient experience of living with orofacial pain: An interpretive phenomenological study. JDR Clinical & Translational Research, 3(3), 264–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/2380084418763317

- Imani, M. M., Jalali, A., Nouri, P., & Golshah, A. (2021, September). Parent’s experiences during orthodontic treatment of their children with cleft lip and palate: Phenomenological study. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal: Official Publication of the American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association, 58(9), 1135–1141. https://doi.org/10.1177/1055665620980606. Epub 2020 Dec 17. PMID: 33334138.

- Iyer, R. R., Sethuraman, R., & Wadhwa, M. (2020, September 1). A qualitative research analysis of gender-based parities and disparities at work place experienced by female dentists of Vadodara, India. Indian Journal of Dental Research, 31(5), 694. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijdr.IJDR_586_18

- Kanchan, S., Pushpanjali, K., & Tejaswini, B. D. (2019, July). Challenges faced by patients undergoing radiotherapy for oral cancer: A qualitative study. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 25(3), 436. https://doi.org/10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_40_19

- Kelly, M. A., Freeman, L. K., & Dornan, T. (2019, July 1). Family physicians’ experiences of physical examination. The Annals of Family Medicine, 17(4), 304–310. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2420

- Kinsella, E. A., & Bidinosti, S. (2016, May). ‘I now have a visual image in my mind and it is something I will never forget’: An analysis of an arts-informed approach to health professions ethics education. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 21(2), 303–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-015-9628-7

- Koch, M., Englander, M., Tegelberg, Å., & Wolf, E. (2014, August). Successful clinical and organisational change in endodontic practice: A qualitative study. European Journal of Dental Education, 18(3), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12066

- Liddle, M. J., Baker, S. R., Smith, K. G., & Thompson, A. R. (2018). Young adults’ experience of appearance-altering orthognathic surgery: A longitudinal interpretative phenomenologic analysis. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal: Official Publication of the American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association, 55(2), 238–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/1055665617726533

- Lovette, B. C., Bannon, S. M., Spyropoulos, D. C., Vranceanu, A. M., & Greenberg, J. (2022, July 29). “I still suffer every second of every day”: A qualitative analysis of the challenges of living with chronic orofacial pain. Journal of Pain Research, 15, 2139–2148. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S372469

- Mabood, N., Ali, S., Dong, K. A., Wild, T. C., & Newton, A. S. (2013, December 1). Experiences of pediatric emergency physicians in providing alcohol-related care to adolescents in the emergency department. Pediatric Emergency Care, 29(12), 1260–1265. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000024

- Marbach, J. J. (1996, February 1). Orofacial phantom pain: Theory and phenomenology. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 127(2), 221–229. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.1996.0172

- Martino, D., Cavanna, A. E., Robertson, M. M., & Orth, M. (2012, October). Prevalence and phenomenology of eye tics in Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Journal of Neurology, 259(10), 2137–2140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-012-6470-1

- Mittal, R., Wong, M. L., Koh, G. C., Ong, D. L., Lee, Y. H., Tan, M. N., & Allen, P. F. (2019, December). Factors affecting dental service utilisation among older Singaporeans eligible for subsidized dental care–a qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7422-9

- Mohanty, V., Jain, S., & Grover, S. (2021, April 1). Oral healthcare-related perception, utilization, and barriers among schoolteachers: A qualitative study. Journal of Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry, 39(2), 154–158. https://doi.org/10.4103/JISPPD.JISPPD_368_20

- Moi, A. L., Gjengedal, H., Lybak, K., & Vindenes, H. (2020, July). “I smile, but without showing my teeth”: The lived experience of cleft, lip, and palate in adults. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 57(7), 799–807. https://doi.org/10.1177/1055665620922096

- Murray, E., Kutzer, Y., & Lusher, J. (2019, March). Dentists’ experiences of dentally anxious patients in a specialist setting: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Journal of Health Psychology, 24(3), 288–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316666655

- Natvik, E., Groven, K. S., Råheim, M., Gjengedal, E., & Gallagher, S. (2019, February 1). Space perception, movement, and insight: Attuning to the space of everyday life after major weight loss. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 35(2), 101–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2018.1441934

- Ojala, T., Häkkinen, A., Karppinen, J., Sipilä, K., Suutama, T., & Piirainen, A. (2015, January 1). Although unseen, chronic pain is real–A phenomenological study. Scandinavian Journal of Pain, 6(1), 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2014.04.004

- Östergård, G. B., Englander, M., & Axtelius, B. (2016, May). A salutogenic patient‐centred perspective of improved oral health behaviour–a descriptive phenomenological interview study. International Journal of Dental Hygiene, 14(2), 142–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/idh.12153

- Page, B. A., Bernoth, M., & Davidson, R. (2014, September). Factors influencing the development and implementation of advanced radiographer practice in Australia–a qualitative study using an interpretative phenomenological approach. Journal of Medical Radiation Sciences, 61(3), 142–150. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmrs.62

- Palmaria, C., Bolderston, A., Cauti, S., & Fawcett, S. (2020, December 1). Learning from cancer survivors as standardized patients: Radiation therapy students’ perspective. Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences, 51(4), S78–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmir.2020.09.011

- Paul, C. R., Vercio, C., Tenney-Soeiro, R., Peltier, C., Ryan, M. S., Van Opstal, E. R., Alerte, A., Christy, C., Kantor, J. L., Mills, W. A., Patterson, P. B., Petershack, J., Wai, A., & Beck Dallaghan, G. L. (2020, February 1). The decline in community preceptor teaching activity: Exploring the perspectives of pediatricians who no longer teach medical students. Academic Medicine, 95(2), 301–309. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002947

- Quigley, R., Foster, M., Harvey, D., & Ehrlich, C. (2022, January). Entering into a system of care: A qualitative study of carers of older community‐dwelling Australians. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(1), 319–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13405

- Reeson, M. G., Walker-Gleaves, C., & Jepson, N. (2013, November 9). Interactions in the dental team: Understanding theoretical complexities and practical challenges. British Dental Journal, 215(9), E16–. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.1046

- Renjith, V., Yesodharan, R., Noronha, J. A., Ladd, E., & George, A. (2021). Qualitative methods in health care research. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 12, 20. Retrieved February 24, 2021. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_321_19

- Safour, W., & Hovey, R. (2019, October 1). A phenomenologic study about the dietary habits and digestive complications for people living with temporomandibular joint disorders. Journal of Oral and Facial Pain and Headache, 33(4), 377–388. https://doi.org/10.11607/ofph.2302

- Saltnes, S. S., Geirdal, A. Ø., Saeves, R., Jensen, J. L., & Nordgarden, H. (2019). Experiences of daily life and oral rehabilitation in oligodontia–a qualitative study. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica, 77(3), 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016357.2018.1535137

- Santos Salas, A., Watanabe, S. M., Tarumi, Y., Wildeman, T., Hermosa García, A. M., Adewale, B., & Duggleby, W. (2019, December). Social disparities and symptom burden in populations with advanced cancer: Specialist palliative care providers’ perspectives. Supportive Care in Cancer, 27(12), 4733–4744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04726-z

- Schneider, A., Andrade, J., Tanja-Dijkstra, K., & Moles, D. R. (2018, August 1). Mental imagery in dentistry: Phenomenology and role in dental anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 58, 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.06.009

- Smith, D. W. (2013). Phenomenology, the stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (winter 2013 ed).

- Stewart, K., Gill, P., Chadwick, B., & Treasure, E. (2008). Qualitative research in dentistry. British Dental Journal, 204(5), 235–239. https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2008.149

- Thomson, R., Docherty, A., & Duffy, R. (2017, May 11). Nursing students’ experiences of mentorship in their final placement. British Journal of Nursing, 26(9), 514–521. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2017.26.9.514

- Toombs, S. K. (1987, August 1). The meaning of illness: A phenomenological approach to the patient-physician relationship. The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 12(3), 219–240. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmp/12.3.219

- Tuohy, D., Cooney, A., Dowling, M., Murphy, K., & Sixsmith, J. (2013). An overview of interpretive phenomenology as a research methodology. Nurse Researcher, 20(6), 17–20. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2013.07.20.6.17.e315

- Tynan, A., Walker, D., Tucker, T., Fisher, B., & Fisher, T. (2020, December). Factors influencing the perceived importance of oral health within a rural aboriginal and torres strait islander community in Australia. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08673-x