Background: The origins of EAMENA

In 2013, the Aerial Archaeology in Jordan project moved its archive to the School of Archaeology in Oxford (www.apaame.org) (see Kennedy and Bewley Citation2008; 2009 and 2012). One consequence of this was a suggestion from the Arcadia Fund (https://www.arcadiafund.org.uk) that Professors Andrew Wilson, David Kennedy and Dr Robert Bewley submit a proposal to examine and document archaeological sites under threat in the Middle East; North Africa was soon added with input from Professor David Mattingly (University of Leicester), given his long experience of archaeological surveys in the Maghreb (Mattingly Citation2004; Citation2013).

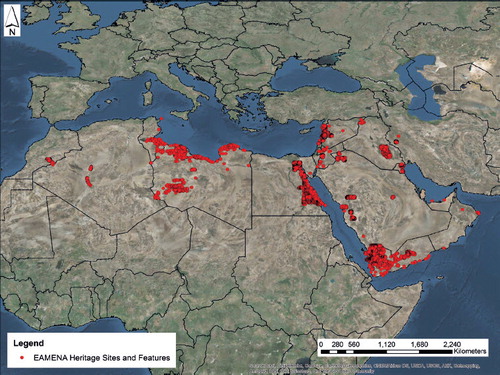

Thus, the Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa was born, and work on data collection and database design began in 2015 (eamena.arch.ox.ac.uk, Bewley et al. Citation2016). Funding was initially approved for two years and in 2016, with the inclusion of Professor Graham Philip (University of Durham), was extended for a further three years. This new phase of the project focuses, in part, on bringing together datasets and information from previous surveys to assist in the creation of a Historic Environment Record (HER) for Syria. Under the umbrella of SHIRIN (http://shirin-international.org) this includes collating data from field projects (e.g. SHR (Philip et al. 2011; Philip and Bradbury 2016)), as well as larger comparative projects (e.g. Fragile Crescent (Wilkinson et al. Citation2014) and PaléoSYR (http://www.cepam.cnrs.fr/spip.php?rubrique175&lang=fr)). In addition, in 2016 Dr Neil Brodie joined the EAMENA project to continue his work on understanding and reducing the impact of looting and the illicit trade in and trafficking of antiquities (http://traffickingculture.org and http://www.marketmassdestruction.com/the-rihani-provenance/).

EAMENA now has a pool of 13 staff, mostly full-time but some part-time, but has also attracted a number of interns, volunteers and partners. These individuals are willing to give their time, and also their data, to help the aims of the project which are to:

Identify, understand and monitor the endangered archaeology of the MENA region.

Create a record of sites and monuments for each country in the MENA region that includes an assessment of the threats to sites.

Help to protect and conserve MENA’s archaeological heritage.

Raise awareness and encourage informed debate about heritage in the region.

Assist customs and law enforcement agencies tackling looting and the illegal trade in antiquities.

Train heritage professionals in methods and techniques to monitor the condition of archaeological sites in as many countries as possible.

Although the project is still in its data collection phase, it is already starting to develop a training component. It was very fortunate, therefore, that The Cultural Protection Fund was launched in June 2016 by the British Council in partnership with Department for Culture, Media and Sport (https://www.britishcouncil.org/arts/culture-development/cultural-protection-fund). This £30 m fund was set up to protect cultural heritage in nine countries at risk due to conflict, mainly in the MENA region. We applied for a project to train up to 120 heritage professionals in the EAMENA methodology; interpreting satellite imagery, creating records and monitoring the condition of sites. The focus was on six countries (Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Palestine, Tunisia and Syria) and funding for this was approved in late 2016. The ‘Training in Endangered Archaeology methodology with Middle East and North African Heritage Stakeholders’ project is now well underway and the first training course took place in Tunis in late 2017, with subsequent courses in Beirut and Amman in early 2018.

Methods: Discovery, Documentation and Dissemination

Creating a methodology to accurately describe, record and interpret archaeological sites, and assess the threats and disturbances to them, is a huge challenge. In response to this, the EAMENA project developed an approach that is easily replicable and aims to standardize ways of working. The methodology and database have been designed to work as a foundation for the development of heritage inventories across this region. Where possible, open-source data and software have also been used, allowing our methods and records to be widely disseminated and adopted.

Map showing the distribution of Pendant sites in Yemen and Saudi Arabia which have been classed as being in a Good or Fair condition versus those recorded as being in a Poor, Bad or Destroyed condition. The inset image shows a Pendant which has been classed as being in ‘Poor’ condition in the database.

The distribution of Pendants in Yemen and Saudi and Arabia which have been assessed for Threats. Several clusters of clearly threatened pendant sites can be identified. As the inset example of a wadi in Yemen shows, Pendants are threatened by a variety of factors including modern roads and tracks and natural impacts, such as Water Action.

Our project combines primary satellite imagery analysis with collation of existing data and sources. Although we utilize a variety of cartographic material (e.g. 1:25,000 maps), aerial photographs (e.g. Hunting Aerosurveys) and satellite data (e.g. declassified Corona images), most of the initial data collection is carried out using imagery available from Google Earth. This approach has distinct advantages—although the imagery is of variable resolutions it is freely available, and large parts of the MENA region are also covered by more than one set of imagery, it is possible to look at change over time. Ground survey and excavation data are, however, also vital. In this respect, the experience, contacts and connections developed by individual EAMENA team members has allowed us to integrate both published and unpublished datasets into our analyses and data collection.

Whether entering data from existing surveys or from satellite imagery, each potential archaeological feature is recorded in our project database (http://eamena.arch.ox.ac.uk/resources/database-2/) using a set of standardized, controlled vocabularies. The database uses Arches, an open source platform implemented by the Getty Conservation Institute and World Monuments Heritage Fund. Again, one of the key benefits of using Arches is the fact that it is freely available, open source software. Details about the form, location and possible period of sites are all recorded using standardized terms. We also include information on ‘certainty’—for example, we can indicate how certain we are that a specific site might be of archaeological interest. This is useful information for researchers and heritage specialists alike. It can be used, for example, to analyse, test or further interrogate hypothetical archaeological settlement patterns, as well as for the prioritization of plans for investigating threatened sites.

The database also includes vital information about the overall condition of archaeological sites. Based on the sources we have consulted, we record the most recent state or condition (Destroyed to Good, with ‘Destroyed’ being the worst and ‘Good’ being the best) of the site, as well as the percentage area that has been affected by anything classed as a disturbance. It is important to differentiate between these two variables as a site can be completely covered by vegetation (e.g. Disturbance Extent 91–100%, but still classed as being in a ‘Good’ condition. Recording specific disturbance events can also allow us to assess how stable a site is and assess the likelihood of potential threats (e.g. anything that might potentially affect a site within 3–5 years). For every identified disturbance event we try to record not only the cause of the disturbance, but also any identifiable effects. For example, using satellite imagery we can often identify disturbance causes such as ploughing. Possible effects of this include the displacement of earth and artefacts, as archaeological layers close to the surface are disturbed, but it can also lead to, or exacerbate, erosion as the protective layer of topsoil is removed. Using imagery from multiple dates we can record temporal information about these disturbances. For example, we might be able to identify sites which were ploughed ten years ago, but which are now no longer being ploughed and cultivated. In this case the threat certainty associated with ploughing might be lower than if the site was still being ploughed in the most recent imagery. In the latter example, ploughing would be recorded as a probable threat, whereas if ploughing seemed to have ceased prior to our last set of imagery we might record the threat as ‘possible’.

Results: Working at Different Scales

Analyses of the EAMENA database will facilitate future research and heritage management at both a local and a broad scale. The database currently contains over 150 000 records, including information about the archaeological sites themselves, and the data sources (e.g. satellite imagery, articles, books and photographs) used to create these records. As we further enhance existing records and add new sites to the database it will be possible to explore the main disturbances and threats affecting sites across the whole MENAregion, as well as how patterns of disturbance may vary from area to area and between different types of sites. Based on our current data, we estimate that c. 20 000 sites are at risk from one or more of the agents of destruction we are recording, be it looting, agriculture, conflict, urban expansion, construction activities or natural erosion.

If we use the example of pendants (stone-built circular burial cairns or enclosures associated with a line of cairns or walls running off them), the database allows us to determine what percentage of these are in a ‘Good’ condition. We can also start to explore the different types of disturbances that might be affecting them. To date, the EAMENA project has recorded over 700 pendant sites from the Southern Levant and Arabia, including Yemen and Saudi Arabia. Some of these sites are comprised of multiple clusters of pendants, or pendants associated with other features such as enclosures and of these c. 700 sites, over 90% are in ‘Good’ or ‘Fair’ condition, whilst around 6% are in ‘Poor’ or ‘Very Bad’ condition. On a less positive note, of the c. 350 pendant sites that have been assessed for threat, c. 40% of these are threatened in some way—by clearance activities, construction or natural impacts such as water action. At the moment, this data shows only a partial picture, but over time, and by working with local antiquities departments and heritage specialists, we will be able to collate more data and build further detailed and comprehensive analyses.

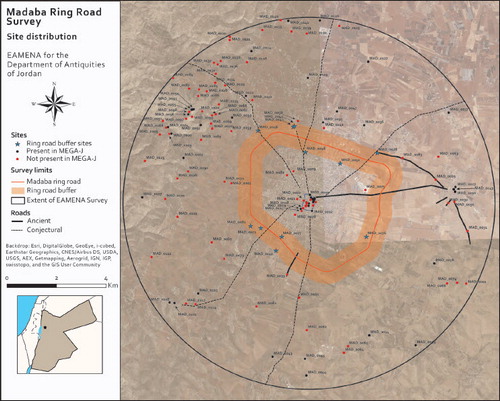

A good example of where our work with local department of antiquities has been of benefit is the Madaba Ring Road Project. In March 2015, following discussions about impending threats in the region, the EAMENA project was invited by the Department of Antiquities, Jordan (DoA) to survey, using satellite imagery, aerial photography and maps, archaeological sites in the location of the Madaba ring road. The assessment carried out by the project documented previously recorded and unrecorded sites and categorized them as either i) those directly affected by the construction of the ring road, ii) sites likely to be indirectly affected, and iii) sites of potential ‘other interest’ that required further assessment in the future. Historical sources (e.g. German WWI photographs from 1918) pre-dating much of the large- scale urban and agricultural development were of vital importance for this survey and allowed us to identify archaeological sites which have since been substantially affected or modified by development. In total, 141 potential archaeological or historically significant sites were identified and recorded, 86 of which did not have a MEGA-Jordan record (the DoA register for archaeological and heritage assets in Jordan). Eleven of these sites have been classified as being directly affected by the ring-road and development in its immediate vicinity. This survey provides the necessary baseline data in order to devise strategies for the future protection of sites, directly and indirectly affected by this road building.

The EAMENA project is also working closely with the Department of Antiquities of Jordan (http://doa.gov.jo/en/) on the future relationship between the MEGA-J database and the EAMENA database. We are also liaising with the Getty Conservation Institute and the World Monuments Fund to ensure there is a tri- partite partnership to enhance the historic environment record for Jordan. The training courses planned as part of the Cultural Protection Fund project will be a useful catalyst for ensuring there is compatibility in the records in the future for MEGA-J and the EAMENA project.

The project has also embarked upon a number of case study projects in North Africa. The al-Jufra oasis in Libya is in a region that has seen relatively little archaeological work, although the oases are of international significance and include archaeological settlements, gardens, field systems and foggaras. Analysis of older imagery has revealed that many sites have already been destroyed, whilst surviving examples are under threat from construction and cultivation. Medieval towns such as Waddan, Hun and Sukna are traceable from aerial photographs. Modern construction, however, is gradually replacing the older structures and in the case of Old Sukna, the entirety of the old town seems to be have been levelled at some point between 1998 and 2003.

Conclusions

We have been working with a small number of countries to assist in the development of their national historic environment records, conforming to CIDOC CRM standards, in particular for Syria (through the Durham team) and for Yemen (through the Oxford team). If these initiatives bear fruit and are successful we will expand their scope though training activities (already planned to take place in Tunis, Beirut and Jordan over the next three years) in other interested countries. In many ways the EAMENA project is just at the beginning; further grant applications and fund-raising are planned for the next five years and it is hoped that the project will continue to expand and develop. Key to this is building up new collaborations. We are already working with several existing field projects or initiatives within the region e.g. The Kūbbā Coastal Survey (see this bulletin), and the Wadi Draa project in Morocco with Leicester University, and hope to develop more initiatives and collaborations for fieldwork and monitoring in the future.

Acknowledgements

The EAMENA Project is funded by the Arcadia Fund and the British Council’s Cultural Protection Fund. We are indebted to them for their support and that of the Universities of Oxford, Leicester and Durham. The Madaba Ring Road case study was carried out, by request from the DoA, Jordan, by Ms Rebecca Banks and Dr Andrea Zerbini (University of Oxford). Dr Louise Rayne (University of Leicester) carried out the al-Jufra case study. We would like to thank all the EAMENA team, staff and volunteers, for their hard work and commitment over the past two years. Last, but not least, we extend our many thanks to the Departments of Antiquities, archaeologists and heritage specialists of the MENA region.

References

- Bewley, R., Wilson, A., Kennedy, D., Mattingly, D., Banks, R., Bishop, M., Bradbury, J., Cunliffe, E., Fradley, M., Jennings, R., Mason, R., Rayne, L., Sterry, M., Sheldrick, N. and Zerbini, A. (2016) Endangered archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa: introducing the EAMENA project. In, Campana, S. and Scopigno, R. (eds), Proceedings of the 43rd Annual Conference on Computer Applications and Quantitative methods: 919–32. London: Archaeopress.

- Kennedy, D. L. and Bewley, R. (2012) The Harret al- Shaam, from air and space. CBRL Bulletin 7(1): 60–62.

- Kennedy, D. L. and Bewley, R. H. (2008) Aerial archaeology in Jordan. CBRL Bulletin: 52–54.

- Kennedy, D. L. and Bewley, R. H. (2009). Aerial archaeology in Jordan. CBRL Bulletin: 11–18.

- Mattingly, D. (ed.) (2013) The Archaeology of Fazzān. Volume 4, Survey and Excavations at Old Jarma (Ancient Garama) carried out by C. M. Daniels (1962–69) and the Fazzān Project (1997–2001). London: Society for Libyan Studies.

- Mattingly D. (2004) Surveying the desert: from the Libyan valleys to Saharan oases. In, Archaeological Field Survey in Cyprus: Past History, Future Potential. Vol. 11: 163–76. British School at Athens Studies.

- Philip, G. Bradbury, J. and Jabbur, F. (2011) The Archaeology of the Homs Basalt, Syria: the main site types. Studia Orontica 9: 38–55.

- Philip, G. and Bradbury, J. N. (2016) Settlement in the Upper Orontes Valley from the Neolithic to the Islamic Period: an instance of punctuated equilibrium. In, Parayre, D. (ed.), La Géographie de l’Oronte. De l’époque d’Ebla à l’époque Médiévale. Syria Supplément 4: 377–95.

- Wilkinson, T. J., Philip, G., Bradbury, J., Dunford, R., Donoghue, D., Galiatastos, N., Lawrence, D., Ricci, A., and Smith, S. L. (2014) Contextualizing early urbanziation: settlement cores, early states and agropastoral strategies in the Fertile Crescent during the fourth and third millennia BC. Journal of World Prehistory 27(1): 43–109. doi: 10.1007/s10963-014-9072-2