The purpose of this short article is not to present archaeological remains, the results of fieldwork, nor even the cultural resource management and public archaeology projects that have been conducted, but rather to discuss the wider context that frames our attempts to move beyond academic, or even narrow cultural heritage management, archaeology. It is not an easy discussion, nor an easy subject. Many within archaeology attempt to ensure their work benefits the public or seek to protect a resource for the future (the destruction created during research is often exempted). However, too often best intentions go awry, as we assume archaeological expertise can be smoothly translated into heritage management expertise, or that large injections of funds into grand projects will produce the outcomes we all desire. There are too many examples of collapsing archaeological remains left exposed in the belief that people would want to see them, or that a conservation plan would emerge, or sometimes simply because the research objective was achieved and the site was abandoned. There are also examples of empty visitor centres as abandoned and distressed as the archaeological remains, or where site displays are visited, but the visitors come as aliens in air conditioned cars and buses and fail to either interact or spend money with the local community. Far from helping, such attempts can result in sites being left in a more precarious position than before research, or further alienated from populations that they may serve.

One of the issues of heritage management, faced with such large volumes of preserved material from the past, is always what heritage to prioritize and preserve. Archaeologists understandably tend to instinctively prefer to protect the material remains that speak most directly to their own research interests, acutely aware of why it ‘matters’ and wanting to share that with others, convinced that others will see the value if only they have a chance to experience it. Tourism agencies prioritize the most immediate and obvious attractions that speak to existing audiences. Governments often favour places that bring in these vital tourism revenue streams, or speak to pertinent national or ethnic identities. The most obvious and well-known authority to turn to would seem to be the World Heritage Convention and its definition of cultural heritage, but this is not easily deployed:

monuments: architectural works, works of monumental sculpture and painting, elements or structures of an archaeological nature, inscriptions, cave dwellings and combinations of features, which are of outstanding universal value from the point of view of history, art or science;

groups of buildings: groups of separate or connected buildings which, because of their architecture, their homogeneity or their place in the landscape, are of outstanding universal value from the point of view of history, art or science;

sites: works of man or the combined works of nature and man, and areas including archaeological sites which are of outstanding universal value from the historical, aesthetic, ethnological or anthropological point of view.’

One of the characteristics of our work within CBRL has been to try to bring together the knowledge and enthusiasm held by the professional, with the cultural and economic needs of the local community, as well as their own passions. Critically this requires a two-way communication. Both groups bring their own expert knowledge and varied motivations to the table. If we, as professionals, wish to share our belief in the importance of the remains we study (their ‘universal value’ if you like), as well as instilling some of our enthusiasm into local communities, then we have to do more than provide academic lectures, or insist on the importance of preserving these remains. It is not about the professional expert talking down to the public: we might believe we can speak from the ‘point of view of history, art or science’, but taking such abstract cultural high ground is unlikely to win us any friends. Archaeologists’ own motivations for such engagement vary, from wanting to ‘give back’, to site preservation, career advancement or, the pursuit of funds or permissions. Community interests are equally varied and exist within the realities of all their everyday needs, not just those of a career: they may be about recreation, employment, identity, religion or many others we are often totally unaware of. Local people frequently have a lot more at stake in the results of archaeological or heritage management activities then those carrying them out. We should never forget that the value of cultural heritage may not lie in what it tells us about human agency 5000 years ago—it may be in the inspiration that can be taken from the idea of human genius, or a sense of community pride, or that the extra bottles of water sold in the village shop are enough to keep it open. And none of those reasons should be looked down on. As long as there are archaeologists who see sites primarily as data mines, and who take little responsibility for their sustainable preservation, or the public value the sites may hold, the boundaries between excavation and looting may seem to have blurred edges. If we want to achieve goals of having more people appreciate this past, and have it benefit the present, then the main task is to understand and communicate our own motivations and goals, and to listen carefully to the perspectives and contexts of those we seek to help or influence.

The Neolithic is a prime example of the difficulties faced in stepping from academic archaeology to public value. Unlike monumental classical archaeology with its temples and columns, or archaeology that relates immediately to contemporary issues and values (for example, in Jordan the archaeology of the Baptism site), the Neolithic is from an unimaginable time ago, and, with the rare exception of sites such as Jericho, is definitely not monumental. Even the name for the period, the Neolithic, is alienating. The public rarely has an existing frame of reference or popular images for the period to provide a ready-made foundation for story telling. Yet, in terms of our own story, of human development, this period when people learned to farm, domesticate their resources, create a new built environment, and develop the social structures that enable us to live together in ever larger communities, is one of the key moments in history. There is human genius all around. In that sense, its universal value is undeniable. Without the Neolithic, the world we live in today would not exist: what is more, Jordan is important in Neolithic archaeology as decisions and choices made by individuals at sites in Jordan probably include some of the key moments in all our histories.

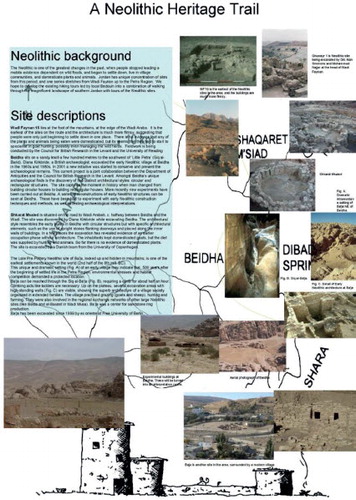

As a consequence, and working very much in the cultural heritage management shadow of Petra, the archaeologists researching a series of sites in southern Jordan agreed to commit to working collectively on a Neolithic Heritage Trail (). Creating a trail rather than just promoting individual sites, is congruent with existing Bedouin initiatives to take tourists hiking, combines the amazing landscapes with the sites, and creates a spatial, as well as historic, narrative. It also has the significant benefit of getting people, Jordanian and international, to extend their stay in the area. Jordanian, British, German, Danish and American colleagues all agreed to work together to tell the Neolithic story, to provide economic opportunities for local people (many of whom were equally in the margins of the Petra heritage industry), and above all to begin to build a wider appreciation of what these sites represent. Most importantly, to talk to people about how this was part of their heritage, not just the heritage of archaeologists, or of international tourists, but something deeply seated in local, as well as global, history. We agreed that to make this approach sustainable we would try to build incrementally, listening to, understanding and working with local communities to create a sense of joint ownership and investment in the project and the heritage to achieve joint goals. We received the support of the Department of Antiquities and Ministry of Tourism and began work.

The CBRL contribution to public archaeology on these Neolithic sites began with Mohammad Najjar (then of the Department of Antiquities), Samantha Dennis (a CBRL Scholar) and Bill Finlayson conducting conservation and site interpretation at Beidha. In the early days work consisted of filling in old excavation trenches, removing spoil heaps that had been left around the site, and making minor visual changes, such as, removing the wire fence from the sky line. We began to build experimental reconstructions with the help of the Amareen tribe and volunteers from archaeological sites and Amman. Samantha developed the project further as her PhD. The reconstructions that were built have gone on to be the heart of site interpretation, incorporated into an overall site management and display supported by the Department of Antiquities, the Ministry of Tourism, the Petra Archaeological Park, and the USAID funded Siyaha project ().

During this time, Paul Burtenshaw, who had been working with the communities in Wadi Faynan, completed his PhD: we were all both surprised and disappointed by how little all the many archaeological projects working in the Wadi had sustainably impacted on the local community. The sense of the ‘universal’ value of many archaeological sites had been transmitted to the community, and many were proud to have places in their area tat drew attention from around the world, and it was generally clear that looting had stopped being an issue on projects with strong community participation, however, very few had anything beyond vague notions of why this interest existed and were often mystified by the activities they saw around them. The seasonal work that archaeological excavations offered was very much appreciated and the sites were valued for their tourism potential, but the research had shown that much of that potential remained as ‘potential’ and the sites actually contributed little local economic impact through visitors. Communities cherished the friends and experiences the archaeological work provided, but only a select handful came away with transferable skills and knowledge that could benefit their lives on a long-term basis.

Looking at the lessons from Paul’s research, we started a new round of research with the communities at Beidha and Basta, this time with Oroub el Abed conducting research and actively liaising with the local communities. This project included a number of community events in the villages, at the sites, and at a workshop in Amman where representatives of the Bedouin communities participated (). It challenged a number of preconceptions, not only for the archaeologists, but also for city dwellers. It showed that many of the ways we thought we could help local communities using archaeology would probably not work. It also showed that there was huge enthusiasm to learn and debate.

Practical issues are important. In Basta local concerns included worries about children falling into the old excavation trenches, worries that the best finds had been spirited away to Yarmouk University in the north, and concern that if the community encouraged tourism it would be swamped by coach loads of inappropriately dressed package tourists. Living just outside the Petra economic bubble let them see both economic opportunity and social disruption. One suggestion for the large, flat, fenced area around the site was use as a youth club football pitch; it was interesting to realise that the site was seen as a potential community resource (or simply a special place) almost regardless of its archaeological significance. In Beidha, in a community more familiar with the heritage tourism industry, the concerns were different. How could the project encourage tour guides to bring their tourists to the shops? How could they effectively market the site to their direct economic gain? Despite the efforts of the various authorities there appeared to be a sense of lack of agency, despite the Beidha community appearing, in many ways, to be more entrepreneurial. For both communities the spheres of relevance for the Neolithic sites did not generally overlap with ours—they were community spaces or economic resources. Their relevant ‘heritage’ lay elsewhere, in more recent historic buildings and practices. This diversity of perspectives presents both challenges and opportunities to create solutions that work for everyone.

In both contexts, one could argue that paternalist politics had resulted in the communities depending on external initiatives and grants, which ran counter to our own hopes of developing engagement and a sustainable, locally led, deployment of cultural heritage. This would be unfair. In both communities there were individuals who were very enthusiastic about raising awareness and initiatives. There was a general agreement regarding the importance of cultural heritage, even if their own priorities might be different. There was a common opinion that much could be added to primary school education, and one of the project’s threads became the difficulties faced by the rural education system.

Back in Wadi Faynan—the focus for much CBRL (and other) archaeological and anthropological research over many years and the Wadi Araba end of the Trail—our joint excavation project with Steve Mithen of Reading University, at the early Neolithic site of WF16, provided new opportunities. The final field season of the WF16 excavation project included building a reconstruction of one of the semi-subterranean mud walled structures. Pascal Flohr, who also undertook the refurbishment of the Beidha experimental structures, led the building project in Faynan, with Mohammad Najjar, Paul and Bill working as labourers, assisted by Bedouin and volunteers from Reading. The Faynan context is very different from that of Petra, which sits at the other end of the currently envisaged trail. With only one hotel, the Feynan Eco-Lodge, it is not on the same scale of the mega site of Petra. However, it is strategically positioned on tourist trails, including those connected to the increasingly popular RSCN Dana Reserve. There have been various initiatives to develop tourism by the local community and there is evidence that low- level, but high-value, tourism could make a significant contribution to the local economy.

The importance of the archaeology of Faynan, from its early prehistory to its significant role in the development of copper mining and metallurgy, has led to discussions regarding whether it might be included on Jordan’s World Heritage tentative list. So far, the Department of Antiquities has built a museum in Faynan (), and asked Mohammad and Bill if they would help with the museum project. Serendipitously, Steve Mithen had just been awarded a grant from the AHRC to build outreach impact onto our excavations, and this has enabled us to start developing the museum. So far, the focus has been to use the museum as an orientation hub, with information on representative sites in the Wadi, including the Neolithic sites that form part of the trail. In addition to the material at the museum, information signs have been placed at each Neolithic site. The project is also training local guides (whose main existing expertise is in natural heritage) in the archaeology of the area; the museum location is intended to serve as the contact point for the Bedouin drivers who take tourists off-road and to the eco-lodge. The museum is including reference to modern Bedouin lives, and linking this back to the history that is presented. A guide book, published in English and Arabic, is being made available and we hope that it will serve as a reference, for not only the guides, but also for the rest of the population. These activities emerge from long-term engagement with local communities, engagement that has allowed us to take the step beyond academic archaeology in an informed way that will create mutual benefits for sites and people, hopefully, for many years to come.