ABSTRACT

This research explores the challenges of using spatial justice as a basis for public policy and urban planning. Philosophical principles of justice are useful for systematic reasoning but lack objective criteria for evaluating spatial justice. We propose a framework based on criteria from social psychology – strict equality, need, merit, and entitlement – to a territorial perspective to determine the most appropriate distribution of amenities. We aim to provide a foundation for policy evaluation and urban interventions based on a selected spatial justice criterion.

Introduction

Guaranteeing justice in the decisions involved in spatial policies is a fundamental goal. Not only due to the inherent importance of justice as a policy goal, but also because it is, ultimately, the claim of pursuing a just distribution of burdens and benefits which confers legitimacy to any policy decision. Spatial justice, or related concepts such as territorial cohesion, or spatial equity, have therefore been guiding principles in the spatial planning field (Kunzmann Citation1998).

Spatial injustice and inequality are crucial to understanding poverty and vulnerability. Geographic disparities in the risk and incidence of domestic energy deprivation, for example, highlights the spatial dimension of justice. Alongside with vicious cycles of vulnerability, spatial configuration may lead certain groups to material deprivation and energy affordability problems (Bouzarovski and Simcock Citation2017). Moreover, it is possible to understand several phenomena in the lights of spatial justice, such as pollution, ethnicity and poverty (Banzhaf, Ma, and Timmins Citation2019), and how low-income groups tend to live with poor access to urban amenities (Uwayezu and de Vries Citation2019). Therefore, it becomes clear the pivotal role of spatial justice as reasonable framework of general interest.

Although the concept of spatial justice can draw from a large and well-established body of literature, namely based on the liberal principles of justice of Rawls or Amartya Sen (Alfasi and Fenster Citation2014; Frenkel and Israel Citation2018; Rauhut Citation2018; Sen Citation2009) or Marxist approaches (Harvey Citation2009; Lefebvre Citation1991), there remains a very significant gap between the theoretical discussions of justice and its assessment in context. As noted by Israel and Frenkel (Citation2020), this difficulty can partly be attributed to the diminished importance of a normative discussion in spatial and social sciences, such as geography or planning, and the lack of spatial analysis in political theory.

Moreover, applying principles of justice to assess spatial layouts also poses very practical difficulties. For example, Lefebvre’s (Citation1991), understanding that space, being socially constructed, enshrines, and reproduces the inequalities that characterize capitalist relations of production, or (Rawls Citation1971) argument that everybody should have access to a scheme of liberties that allows for a similar scheme for all, provide interesting perspectives on the (in)justices that are inherent to our societies. But they do not provide a clear roadmap to judge the concrete distribution of spatial advantages or disadvantages. Therefore, while there are abundant examples of studies on the perceptions and representations of spatial justice (Alfasi and Fenster Citation2014; Heikkila Citation2001; Knudsen et al. Citation2015; Nylund Citation2014) or empirical studies of spatial inequality (Chakravorty Citation1996; Márquez, Lasarte, and Lufin Citation2019; Panzera and Postiglione Citation2020; Perez-Mayo Citation2019), translating normative arguments or abstract principles of justice into measurable, spatialized, indicators of inequality are still a challenge.

The establishment of a working definition of spatial justice is further complicated by the fact that, as noted by Sen (Citation2009), there are many different definitions of justice which can be applied to assess the fairness of a given situation and different dimensions which can be included or excluded in this assessment. Nonetheless, any working definition of spatial justice needs to answer two basics questions: What is the claim to a given resource/advantage? And according to which criteria should it be assessed?

This article contributes to this subject by identifying objective criteria of spatial justice and illustrating how they can be applied to assess the justice of different geographical distributions of services, thus focussing on the distributive aspects of spatial justice. For the practical assessment of spatial justice, we draw on the distributional principles of justice identified in psychological research – equality, need, merit, and entitlement – showing how they can be associated with different distributions of spatial advantages, and how these criteria are considered by different schools of thought from the political philosophy.

Similar attempts to classify justice applications can be found in scientific literature, specifically regarding health service provision. Mooney (Citation1987) seeks for a robust definition of equity by indicating five different general concepts of justice that are generally discussed in public health services, including some Rawlsian and Sen’s perceptions regarding fair provisioning of goods and services. Hadler and Rosa (Citation2018) go further on their analysis by stating that ethical reasonings may lack objective definitions that may lead to spatial discrimination based on merit or need. Gibson (Citation2008) also apply concepts of need and deservingness to assess squatters’ and owners’ rights to land. This article is based on a similar approach but establishes a more comprehensive conceptual framework which tries to apply all the four criteria of justice identified in the social psychology and also analyses how they are related to the broader discussion of justice in the political philosophy, namely considering Marxism, libertarianism, utilitarianism, and liberal equality.

Considering the difficulty in finding unequivocal practical formulations of the philosophical discussions of justice, it is our understanding that their spatialization is best understood by considering the way in which they are related to objective criteria. This allows to move towards an operational framework of spatial justice that, while drawing from broader philosophical discussions, provides a roadmap for considering a given geography just or unjust from a distributional perspective. This also allows a practical analysis of spatial policy goals and how they are considered in the spatial distribution of resources.

Our work proceeds with a discussion of abstract formulations of justice, stressing how complex is their application in spatial terms. Then, we present how social psychology describes underlying notions of justice (criteria) and how those criteria can be related to the spatial distributions of services. Finally, we describe how authors are judging to specific justice criteria when they approach spatial justice topics.

What is justice?

People are naturally inequal. Either by preferences, culture, mental states, and a myriad of different aspects that make every person unique. This raises the question of how to consider these different circumstances when weighting the claim to resources or advantages, assuming that individuals will try to maximize their satisfaction in the access to these resources or advantages (Karni and Safra Citation2002; Oppenheimer Citation2012). In other words, when common resources are shared, there is the need for some rationale for weighting different claims, according to a particular understanding on what would be a fair distribution of goods and services (Dubas, Dubas, and Mehta Citation2014; Kamas and Preston Citation2012).

Justice is the normative concept that defines a set of rules to morally evaluate the distribution of resources between individuals. Hence, it tries to elaborate ‘what is right, what is fair and what is morally correct’ (Wolff Citation1997, 12). The complexity in trying to answer these questions is considerable and is further increased when trying to assess practical scenarios. First, since ethical rules claim for a certain universality and, therefore, tend to be based on philosophic, abstract reasoning, many authors elaborate justice principles in a hypothetical fashion. Second, because these principles generally discuss conflicting perspectives and criteria, their outcomes can be controversial and have considerable ethical implications (see, for example, Nyholm and Smids Citation2016 for a discussion of the ethics of programming self-driving cars).

Hypothetical formulations of principles of justice

Different schools of thought have defined justice in very different ways. One of the most significant efforts to explain the different allocation of resources in society can be found in utilitarianism. For some authors, such as John Stuart Mill, utility is a measure of pleasure and happiness. As this is a fundamental value, Mill’s defense on utility is justified by the rationality on pursuing it: ‘(…) If so, happiness is the sole end of human action, and the promotion of it the test by which to judge of all human conduct’ (Mill Citation1863, 39).

This is a strong argument that shapes utilitarian reasoning, but in the same chapter of this citation, Mill admits that there cannot be further proof for this, other than people’s intrinsic desire for pleasure (Citation1863, 35). This leads to a hypothetical scenario where people will understand their overall happiness as a good, compete with one another to maximize their payoffs, establishing general happiness as an aggregate good to be maximized (Millgram Citation2000).

While solving complex issues of commensurability by establishing utility as a universal unit of measurement, this approach raises challenges to be overcome when sharing limited resources in society, such as the number of available choices (Sen Citation2009) and how to weight the different levels of utility that different people get from the same resource. This can lead to utility being used to justify very different distributions of resources. It can, for example, be justified to provide a larger share of resources to the already well-off, if this distribution is Pareto optimal, while the law of diminishing marginal utility can also be used to justify redistributive policies (as is done by Pigou Citation1932). Utilitarian perspectives of justice are also at odds with rights-based ethics, such as those expressed by Kant’s categorial imperative.

An alternative formulation of justice is made by authors aligned with a liberal egalitarian perspective, such as Amartya Sen or John Rawls. Rawls, whose principles of justice are arguably the most acknowledged and discussed ones, proposes a scenario where individuals are put into original positions without memories and without knowledge of their previous and future lives – the ‘veil of ignorance’ (Rawls Citation1971, 34). If this group is supposed to decide about the future outcomes of their unknown positions in society, it is reasonable to assume that people would decide in favor of an egalitarian distribution of resources and goods. Consequently, if an intervention must be done in society, it should favor the least well-off, following the ‘difference principle’ (Rawls Citation1971, 65).

Amartya Sen (Sen Citation2009), questioning the possibility to establish a single set of principle of justice from an initial position, argues that there are many possible, and unbiased, principles that can be used. This argument is illustrated through a scenario where three children contend for a flute. One of them assumes a utilitarian perspective, arguing that she is the only one who knows how to play the flute. The second one uses an egalitarian argument, stating that his poverty and lack of toys would mean that he should have at least one toy. Finally, the last kid argues that she made the flute, and therefore, should hold possession of it. Sen uses this metaphor to describe how justice can be complex to achieve. If pursuit of happiness and pleasure (utility) is the goal to be achieved, the first kid should get the flute, disregarding the other two arguments, including the third kid that put effort into creating the instrument. The second kid is backed by the Rawlsian veil of ignorance reasoning. The third kid should be compensated if merit for the effort is to be considered more important. Thus, according to Amartya Sen’s approach, more than settling on a fixed principle, justice should be concerned with guaranteeing equality in the substantive opportunities that are available to different individuals or groups, according to their idiosyncratic capacity to translate abstract access into actual advantages – each individual’s capabilities.

Another method to justice can be found in Marxist approaches, which tend to assume that inequality and injustices are the natural outcome of the capitalist mode of production, and the exploitative relationships they entail. Social inequality can, in this sense, be understood as the reification of the social relations of production, and only changes to the deeper structural forces linked to capital accumulation can truly lead to any form of justice. In a way, the collective ownership of property and a principle of distribution where each gives according to their ability and each receives according to their need, envisages a society beyond justice, and the degree to which these criteria express principle of justice can be questioned altogether (Geras Citation1985). And it can also be noted that the criteria of ability and need, notwithstanding their axiomatic formulation, are radically contingent (Kellogg Citation1998), with their exact meaning depending on the very idiosyncratic concepts of ability and need. Nonetheless, and although it is more concerned with the social relations of production, in the hypothetical scenarios discussed above it can be reasonable to assume that a Marxist approach would lead to a need-based distributions or resources, and not the recognition of ones’ effort or utility.

Last not least, a justice perspective worth mentioning is the libertarian political philosophy. From a libertarian perspective, there is a singular value to the notion of individual liberty, in detriment of the role of State authority to enforce rights and policies (Bevir Citation2012, 810). For the defenders of this line of reasoning, there is a strong disbelief in the central form of government, such as the State, and the justice of a given distribution of resources (or holding) is obtained by a just initial acquisition of this resource and its voluntary exchange. Any distribution that follows these rules is, by definition, just, and there are no other legitimate claims to be made (Nozick Citation1973). Thus, and as is noted by authors such as Kymlicka (Citation2002), libertarian approaches emphasize property rights and the entitlement to ones’ holdings. There is a strong inclination to the effects of market on resources distribution, but no general rule of how to assess just outcomes. Results that came from the market interactions are just enough, given some presumptions are assumed, such as autonomous individuals making fully informed decisions. Therefore, the claim of imposed interventions makes no sense because holdings and capital accumulation (or the lack of it) are already just outcomes.

It is true that the liberal egalitarian perspectives are easier to apply to distributive justice, while Libertarian and Marxist approaches tend to be based on more general assumptions of what would be a just societal organization. Nonetheless, all approaches can be used to evaluate justice claims, and their effectiveness can depend either on preferences or be rhetorical. In practice, different distributions of advantages or resources can be justified according to different theoretical assumptions and reasonings, and the criteria which are considered to assess them. When the criteria change, the assessed injustice also changes, but the initial condition of inequality remains. Consequently, the challenge is to identify what criteria arise from justice principles and how to apply them.

From social to spatial justice assessment

Spatial justice is concerned with how to apply different principles to assess, and judge, the distribution of social groups and different types of amenities throughout the territory, as well as the advantages that are conferred by these distributions and the processes that lead to them. It is closely related to the concept of spatial equity which, according to Morrill and Symons (Citation1977), can be understood as ‘justice with respect to location’, and essentially expresses the moral obligation to guarantee a fair distribution of spatial amenities and burdens, or the regulation of property rights.

All of the approaches discussed in the previous section have been applied to assess spatial justice. One of the most significant contributions for defining spatial justice comes from the Marxist school of thought, namely Lefebvre, whose conception of ‘right to the city’ (Lefebvre Citation1996) assumes that people should not be alienated from the spaces of everyday life. The right to urban life should be surrounded by proper rights of access to work, education, health, accommodation and so on, which are difficult to guarantee under the rules of market and competition. And space, being socially constructed, already entails the inequalities and reifications that are at the core of capitalist societies, leading to systematic inequalities and the segregation and exclusion of the least advantaged (i.e. the working classes). However, as noted by Harvey (Citation2009), from a Marxist perspective social justice is contingent to specific processes, dependent on what we are distributing and among whom it is being distributed and its main contribution to spatial justice is to understand, and denounce, the exploitative relations that are shaping our geographies. Therefore, and although examples based on Bourdieu’s conceptions of capital have been made (Frenkel and Israel Citation2018), practical assessment of spatial justice according to Marxist principles of justice tend to be scarce. This is also true for libertarianism, which does not really provide a framework to assess spatial justice, since it assumes that any distribution of spatial benefits that comes from free market transactions between consenting adults is just (Pereira, Schwanen, and Banister Citation2017).

Liberal or utilitarian assessments of spatial justice are, however, frequently made. From a liberal perspective, spatial justice is often understood to mean favoring the least well off in a given intervention or situation. Rawls, Citation1971) principle of justice suggests interventions on institutional level to favor the least well off. Therefore, if this conception of justice is to be applied on the territory, ‘fair distribution of benefits and mitigating disadvantage should be the aims of public policy’ (Fainstein Citation2016). Utility, on the contrary, can be used to justify better access to spatial resources for the better-off groups, if their well-being exceeds the decrease in well-being that is experienced by the least well-off (Pereira, Schwanen, and Banister Citation2017). It is true that inequality is being reinforced between the two groups, but an egalitarian criterion is being observed by considering all people with same importance, hence the focus where the overall well-being if being maximized. It is also possible to create different weights for the different groups, following the rule of more utility for the least well-off, to promote equality as well as maximization of utility (Weirich Citation1983) being exceeds the decrease in well-being that is experienced by the least well-off (Pereira, Schwanen, and Banister Citation2017). It is true that inequality is being reinforced between the two groups, but an egalitarian criterion is being observed by considering all people with same importance, hence the focus where the overall well-being if being maximized. It is also possible to create different weights for the different groups, following the rule of more utility for the least well-off, to promote equality as well as maximization of utility (Weirich Citation1983).

However, not only socioeconomic features may be used to distinguish groups. For example, Nassir (Nassir et al. Citation2016) proposed a utility-based model for public transit modes, based on the passenger’s preferences and subjective perceptions on how much journey times can take. By doing this, the author lays leverage on different groups to achieve some sort of balance on public transport services, in other words, some sort of equal equilibrium. Another application of different weights to achieve fairness in distribution of services can be found on Feitosa et al. (Citation2021), who uses an impedance decay function to achieve optimal school locations for those groups without proper access to education, focussing on peoples need. Oddly, the latter work is focused on a Rawlsian approach rather than utilitarian, but both try to focus on some sort of egalitarian perspective to achieve fairness. It seems that when authors argue about ‘justice’ or ‘fairness’, the egalitarian criterion is the core concept they try to achieve.

Amartya Sen’s capability approach is also frequently used for assessing spatial justice (Preston and Rajé Citation2007), for example, propose a model to assess and suggest interventions based on Amartya Sen arguing that regular policy assessment methodologies leave some groups systematically out of the benefits proposed by public agents, favouring the rise of social exclusion. The capabilities approach is used by these authors to justify the proper levels of accessibility and mobility, focused on identifying what groups (or individuals) are being excluded, implying a certain level of balance. Another example of Sen’s capability approach to assess spatial justice can be found in (Nuvolati Citation2009), who applies Sen’s theory to the accessibility to different spatial amenities considering the number of alternatives that are available to different groups.

While providing many examples of how broader philosophical approaches can be applied to spatial justice, the literature also makes it clear that there are many ambiguities in this application. On the one hand, the same theory of justice can be used to focus very different aspects. Amartya Sen’s capability approach can, for example, has led to focussing the number of choices that are available in a given situation, but can also be used to assess the exclusion of certain groups from proper access. And utilitarianism can be used in a rather egalitarian way, by attributing equal weight to everybody’s utility, or attributing different weights to different groups. On the other hand, different theories of justice are used to justify the same kind of assessment. A focus on the least well-off, in particular, can be found in utilitarian approaches that give higher weight to the least well-off (assuming that their marginal utility will rise more from a smaller increase in some benefit) but also in Rawlsian or Marxist approaches, that focus on the position of those groups because it violates the difference principle or because it expresses exploitative social relations. Further, assessment of spatial justice frequently focus the least well-off without reference to any specific principle of justice, such as can be found in the works of (Jonkman and Janssen-Jansen Citation2018), who focus on the distributive justice in housing mismatches, or (Dawkins Citation2021), who propose assessing the justice of housing policies in its substantive implications by considering how they reduce extreme poverty.

Distributional principles from the psychological and social-psychological justice research

As noted by (Liebig, HHlle, and May Citation2016), psychological research has identified four practical criteria according to which the distribution of a given resource tends to be assessed: strict equality, need, merit, and entitlement.

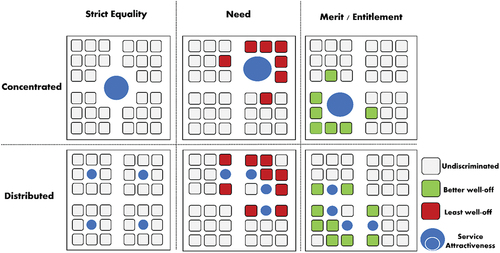

The application of different criteria for assessing spatial justice can have significant implications for the distribution of resources within urban environments. According to the criterion of strict equality, resources should be distributed in a way that minimizes the average levels of accessibility, with a focus on central locations. This approach seeks to ensure that all individuals have an equal level of access to resources, regardless of their individual circumstances or characteristics.

On the other hand, the criterion of merit or entitlement suggests that resources should be distributed to those who have contributed the most to financing them, often favoring the upper and middle classes. This approach is based on the idea that those who have contributed more to society should be rewarded with greater access to resources and opportunities.

In contrast, a need-based approach to resource distribution would prioritize providing better access to those who are least well-off. This criterion is based on the idea that resources should be allocated to those who have the greatest need, regardless of their individual contributions or circumstances.

The choice of criterion can have significant implications for the distribution of resources within urban environments and can ultimately shape the overall level of spatial justice within a region. It is therefore important to carefully consider the different criteria and their implications when developing public policies and urban planning strategies. depicts what could be understood from justice criteria prioritization, in a caricatural scenario. n considering the different configurations of urban spaces that could arise depending on the criteria adopted for justice consideration, it is important to recognize that real urban configurations are often more complex. However, understanding the potential variations in spatial configurations that can result from different justice criteria can provide valuable insights for policy makers and urban planners seeking to create more equitable and just urban environments.

The scenarios are, naturally, rather caricatural – they assume a clean state for the creation of a utopic distribution based on each criterion and also some simplifications regarding the way the criteria are translated (e.g. equating being better-off with having more merit). And it is also true that the categories are not completely independent. Distributing resources according to peoples’ need can, for example, be considered a way of maximizing equality – not in the access to the resources, but by considering the different capabilities to transform a potential access into a substantial advantage. Nonetheless, they provide interesting benchmarks according to which the priority given to different criteria of justice can be assessed in spatial policies.

But how can these different criteria be related to the philosophical discussions of justice? The rest of this section discusses this relationship.

Strict equality and need

The understanding of modern western societies that live under the rule of law is that people should be treated as equals. This does not mean that individuals are considered as equals per se, but rather that certain differences between them are to be considered irrelevant (Kelsen Citation1999, 439) Different types of philosophical theories assume this intrinsic idea of equality as a core concept, with relevant reasoning as a consequence. Before the illuminist viewpoint on empiricism and rational thinking, Europe was socially forged by a Jewish/Cristian doctrine that evoked the idea that all human beings should be treated as equals, as once created by a ‘superior creator’. Nevertheless, there was a relatively strict inequal hierarchy among the social classes on medieval feudalism, but this line of thinking paved the way for modern philosophers to think about human relations and justice claims. The work of Willian Paley (Paley and Faulder Citation1785), for example, grounds itself on utilitarianism and Christian ethics to discuss what is right or wrong, good or bad concerning making choices, hence, ethical issues (Hibberd, Citationn.d.). His contribution still had religious background but was considered influential and served as basis for utilitarianism theory. Later, Jhon Stuart Mill and Jeremy Bentham diverted from the religious background and looked for a ‘foundation of a scientific and exact ethics on the basis of a scientific and exact psychology’ (Stark Citation1941), considering a systematic and objective way to propose utilitarianism as a general political philosophic theory. For them, what matters is the individual’s perceptions of pleasure and pain and, therefore, to make appropriate choices regarding the maximization of one or the minimization of the latter. This approach has several consequences when public policies are formulated and applied, especially when spatiality is considered as previously discussed on our topic ‘what is justice?’. The fact is that this underlying notion of individual rights and equality started to become considered as settled when modern revolutions took place and rearranged both the socioeconomic divisions of society and ways of production, broke some of the barriers of the current time for individuals to improve their wellbeing (Acemoglu et al. Citation2011), supported by the legitimacy granted by society to the State, for example on the French and United States modern revolutions (Bukovansky Citation2002).

But even if we are to be treated as equals, how shall one consider individual preferences regarding the utility received by a benefit or good (let us say a basic service, for example)? Utilitarianism has a strong focus on pleasure and pain, so it is reasonable to assume that to measure utility one must also consider individual needs, and how those individuals (or related groups) value those specific needs. We are aware that several works may have different understandings and theoretical frameworks to support either an individualized, preference guided form of utilitarianism, or an egalitarian form of aggregated utility, where similar groups are counted with the same level of utility regarding assumed socioeconomic needs.

Nevertheless, equality and need are not the norm only from liberal perspectives. Marxism, for example, proposes a classless reformulation of society, focused on extinguishing the private property of the means of production. If properly achieved, people would not have intrinsic desire for accumulation and would produce at the best of their capacities, consuming (goods and services) according to their needs, following an altruistic fashion. When translated to spatial terms, this concept is not objective nor clear. The usual interpretation observed on related works usually states that people have similar basic spatial needs, such as access to housing, education, and health facilities, and once those are fulfilled, people should get the same level of access to services.

On the former Soviet Union (USSR), uniform residential zones were created with both equality and essential needs fulfillment as an urban design project, where housing blocks had a basic service (such as a basic school), open green areas for commuting, and planned street network to serve industry and work zones (Metspalu and Hess Citation2017), in a way that all necessary services were on reasonable walking distances, leading people to take transportation for workplaces. Another example of Marxism application can be seen on the creation of Brasilia, from scratch. The city was brought to life following Lucio’s Costa urban plan, and the understanding of Marxism design of a city would be the notion of spatial equality, mostly related to the distribution of housing and access to services, focused on equality of opportunities regardless of social distinctions and urban qualities necessary for full human development (Rezende and Heynen Citation2021).

The different rationales and ethical reasonings that come with them bring a similar understanding of equality and need. Even though the formulations and theories are different, it is not hard to picture a scenario where the underlying notion of equality and need are embossed on either of those philosophical perspectives. It is hard to track history or scientific literature where this notion of equity being related to strict equality and need came from. Even though it is not in the scope of this work to tackle the history of this theorical reference, we can reasonably assume that these are intrinsic values mostly taken for granted in modern western democracies. The spatial notion that individuals have on these core concepts of social justice are naturally translated into spatial terms that, in a larger scale, can assume different viewpoints on public policies. As discussed above, it does not seem to be enough to define an objective intervention in a specific justice principle, because equality and need can be pursued in different forms in any of them.

Merit and entitlement

The idea of proportional compensation over the effort employed is directly related to the notion of market and competition. Since resources are limited, there must be reasoning on their distribution and, therefore, makes sense to reward individuals that put energy on their development to achieve higher levels of contribution with more resources (or goods).

Nozick (Citation1974) argues about the necessity to value the entitlement over a distribution, no matter how inequal it is, respecting the presumption that they were got via legit means. By legit means, Nozick states that unowned ‘holdings’ must be acquired without others prejudice, they can be voluntarily transferred (i.e. heritage) or by rectifying past injustices regarding the acquisition or transfer (Nozick Citation1974, 150–3). For him, those who worked hardest will have more (merit), as long as they did not harm anyone else during the process, which poses a significant contrast with the egalitarian perspective proposed by Rawls.

The main implication and contrast are that capital and resource accumulation in the long term are valid and do not pose any sort of unfairness, hence there is no need of State intervention to adjust the disparities caused by natural inequalities, such as socioeconomic situation of birth, or caused by market dynamics. The libertarian perspective proposed by Nozick puts strong focus on a minimal State, because every type of intervention could be associated with restrictions to individual liberty. Instead, markets should be taken as fair demonstrations of human relations because they are the result of informed and capable individuals exchanging their fairly won rewards. Different rationales are derived from this perspective, such as the idea of institutional competition for performance improvement, including public sectors of government (Prosser Citation2005) and that a fair society is related to the social mobility (Brown Citation2013), more than compensation over inequality.

Nevertheless, libertarianism is another justice principle that does not translate directly in spatial terms. If taken to the extreme, not even public policies should be applied to solve any kind of identified inequality. There is still room for debate regarding the application of those principles in practice (for an insight over the differences and similarities about Nozick’s and Rawls work see (Schaefer Citation2007). There is still another argument over Nozick’s perception of community fairness, since an egalitarian group could arise and establish their rules under libertarianism principles, if no one was forced into this situation. This reinforces our argument on justice principles are not comprehensive to assess spatial distribution of goods, even though they are distributive justice principles.

We argue that merit and entitlement are strongly related as justice criteria for inequality assessment. That is not to say that entitlement has not receive substantial attention in academic literature. Several works discuss the social impacts caused by gentrification processes, how people get pressed to move from their homes because of land-price appreciation caused by public transport expansion (He et al. Citation2018), or because touristic guided policies (Diaz-Parra and Jover Citation2021) that bring wanted resources to local market but takes from natural inhabitants the possibility to afford living.

In fact, market and preferences dynamics are so complex to consider that some authors even describe gentrification as a tool to perform social cleanse (Epstein Citation2018), to remove from specific places specific ethnicity or marginalized groups. Objective reasoning guide us to understand that those inequalities should not be the reason to alienate people to their right to live on their homes. Arguably, marginalized groups would probably go to worst served places, leading them to a deprivation amplification process (Macintyre, Macdonald, and Ellaway Citation2008), reinforcing their initial marginalized position.

However, since housing is the central space that individuals have stability, access to urban resources and goods (Lefebvre Citation1996; Muñoz Citation2018), and we live in market driven societies it is expected that better access to services and amenities have an underlying cost (Allen Citation2015; Park et al. Citation2017; Yuan, Wei, and Wu Citation2020). Being rewarded for merit will imply that individuals with higher performance in social competition will have better payoff, higher contribution for society and, therefore, be able to afford ‘better’ housing, including the burden of paying more taxes for better served places.

There is evidence that the most well-off groups in society tend to live closer to amenities and, interestingly, that the higher group tend to live further, since they can choose to do it and afford multiple mobility ways to get to farther services (Marques, Wolf, and Feitosa Citation2020). Following merit centered reasoning, if those groups worked hard enough to have benefits, taking those advantages from them would be an offense to their efforts. In a sense, entitlement is this sentiment of prerogative right, acquired in legit ways, that is not supposed to be removed. To receive a house in a well-served vicinity as heritage, for example, is an example of housing benefits that originate from previous merit. When looking into justice principles to set a fairness claim, such as libertarianism or Rawlsian approach, we argue that what we are looking for is the primitive sense of what is fair, in the heritage case, the effort applied and right to own that place, merit and entitlement as criteria for fairness justification.

The following table represents a explorative approach of the weight that the different philosophical approaches give to the different criteria, as shown in .

Table 1. Exercise to relate social justice principles and spatial justice criteria.

Conclusions

Social justice criteria isolated from justice principles frameworks are widely discussed (Liebig et al. Citation2016; Miller Citation1999; Rodriguez-Lara and Moreno-Garrido Citation2012), but the search for objective criteria to assess spatial justice poses very significant challenges. Different philosophical approaches have put forward different criteria to justify the claims from different groups, such as: individual need for a given resource; the broader benefits from its use (does it contribute to society?); the utility that people get from it; effort or merit; inherited or natural rights. In short, the criteria that are used, and the principles to rank them, are fundamental to understand the different circumstances of individuals or groups, and the advantage, or disadvantage, they get from a given state of affairs, and how to judge it. Nonetheless, their spatial translation is far from straightforward, meaning that the same philosophical approaches can be used to justify different criteria, and that similar valuing of criteria can be used by different approaches.

We, therefore, argue that principles of justice derived from philosophical discussion, although important regarding the systematization of reasoning, are lens of analysis that lack objective criteria for spatial (in)justice assessment. In practice, different distributions of advantages or resources can be justified according to different theoretical assumptions and reasonings, and those can be considered (un)fair according to the criteria which are used to justify them (i.e. justice principle). When the criteria change, the assessment of the degree of justice of a given geography also changes. In this sense, discussing the criteria that can be used for judging spatial inequalities, and their justification according to different philosophical reasonings, is an important aspect for the practical assessment of spatial justice.

We address this issue by applying four criteria of justice identified in the social psychology – strict equality, need, merit and entitlement (Deutsch Citation1975, Citation1985; Liebig, HHlle, and May Citation2016) to a territorial perspective. We also explore what spatial distribution of amenities or services would best correspond to these criteria, and also how they can be related to the philosophical discussions of justice from different schools of thought. Through this approach we aim to contribute to establish a conceptual framework that allow to identify to which criteria a given distribution of spatial resources is more related to, and to propose interventions based on a selected spatial justice criterion. For public policies and urban planning, this can serve as solid framework for policies evaluation and urban interventions since they need to serve the public common interests.

Integrating the principles of spatial justice into urban planning and policy necessitates a nuanced understanding, best illustrated through real-world applications. The following examples each underscore different facets of spatial justice, demonstrating the diverse ways in which urban planning can engage with and address the principles of equality, need, merit, and entitlement to guide equitable outcomes. Firstly, the concept of ‘In-Place Social Mobility’ (IPSM) illustrates how urban regeneration can be an opportunity for homeowners to achieve social mobility without leaving their homes and neighborhoods (Levine and Aharon-Gutman Citation2022). This approach offers a fresh perspective on spatial justice, suggesting that equitable urban development can indeed enhance the social opportunities of residents through targeted policy interventions, reflecting the need and entitlement criteria.

Secondly, the Singaporean government’s effort to ensure affordable homeownership by setting housing price to income ratio targets showcases the implications of strict equality and need criteria in addressing housing affordability and mitigating market volatility (Phang Citation2010). Lastly, the comparative study of urban redevelopment in Bogotá, Colombia, and Buenos Aires, Argentina, reveals the complex interplay between libertarian and utilitarian approaches to land titling and housing accessibility (Yunda and Sletto Citation2017). This case study underscores the importance of recognizing merit and entitlement in urban policy to navigate the challenges of formal and informal land markets. By integrating these principles into urban policy frameworks, we can move towards a more equitable urban structure, addressing spatial injustices through nuanced, context-specific interventions. In this work, we advocate for an approach to spatial justice that transcends simplistic dichotomies of good versus bad, emphasizing instead the rational foundations that guide equitable outcomes. This perspective fosters a dynamic, iterative engagement with equity, acknowledging that disparities surface uniquely under different evaluative criteria. By foregrounding the critical, ongoing examination of how inequalities manifest across various justice criteria, we propose a more nuanced, adaptable framework for urban policy and planning. This approach underscores the importance of a deliberate, thoughtful response to the ever-evolving landscape of urban disparities, promoting a sustained commitment to addressing spatial injustices in their multifaceted dimensions.

In conclusion, the use of spatial justice as a guiding principle for public policies and urban planning presents several challenges, including the lack of objective criteria for determining what constitutes a fair and equitable distribution of resources and the difficulties in acquiring the data needed to address spatial injustices. By applying various criteria of justice identified in social psychology to a territorial perspective, this study aims to propose a conceptual framework that can help identify the criteria to which a given distribution of spatial resources is most related and propose interventions based on a selected spatial justice criterion. This framework has the potential to provide a solid foundation for policy evaluation and urban interventions that prioritize the common interests of the public. However, it is important to recognize that the application of spatial justice is complex and requires a nuanced understanding of the various criteria and their justifications. Further research is needed to continue to explore and refine the use of spatial justice as a guiding principle for public policies and urban planning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acemoglu, D., D. Cantoni, S. Johnson, and J. A. Robinson. 2011. “The Consequences of Radical Reform: The French Revolution.” American Economic Review 101 (7): 3286–3307. https://doi.org/10.1257/AER.101.7.3286.

- Alfasi, N., and T. Fenster. 2014. “Between Socio-Spatial and Urban Justice: Rawls’ Principles of Justice in the 2011 Israeli Protest Movement.” Planning Theory 13 (4): 407–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095214521105.

- Allen, N. 2015. “Understanding the Importance of Urban Amenities: A Case Study from Auckland.” Buildings 5 (1): 85–99. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings5010085.

- Banzhaf, S., L. Ma, and C. Timmins. 2019. “Environmental Justice: The Economics of Race, Place, and Pollution.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives: A Journal of the American Economic Association 33 1 (1): 185–208. https://doi.org/10.1257/JEP.33.1.185.

- Bevir, M. 2012. “Encyclopedia of Political Theory.” Encyclopedia of Political Theory. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412958660.

- Bouzarovski, S., and N. Simcock. 2017. “Spatializing energy justice.” Energy Policy 107:640–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENPOL.2017.03.064.

- Brown, P. 2013. “Education, Opportunity and the Prospects for Social Mobility.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 34 (5–6): 678–700. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2013.816036.

- Bukovansky, M. 2002. Legitimacy and Power Politics : The American and French Revolutions in International Political Culture, 255. Princeton: Princeton University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7sk4w.

- Chakravorty, S. 1996. “A Measurement of Spatial Disparity: The Case of Income Inequality.” Urban Studies 33 (9): 1671–1686. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098966556.

- Dawkins, C. 2021. “Realizing Housing Justice Through Comprehensive Housing Policy Reform.” International Journal of Urban Sciences 25 (S1): 266–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/12265934.2020.1772099.

- Deutsch, M. 1975. “Equity, Equality, and Need: What Determines Which Value Will Be Used as the Basis of Distributive Justice?” Journal of Social Issues 31 (3): 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1540-4560.1975.TB01000.X.

- Deutsch, M. 1985. Distributive Justice: A Social-Psychological Perspective, 313. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Diaz-Parra, I., and J. Jover. 2021. “Overtourism, Place Alienation and the Right to the City: Insights from the Historic Centre of Seville, Spain.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 29 (2–3): 158–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1717504.

- Dubas, K. M., S. M. Dubas, and R. Mehta. 2014. “Theories of Justice and Moral Behavior.” Journal of Legal, Ethical & Regulatory Issues 17 (2): 17–36.

- Epstein, G. 2018. “A Kinder, Gentler Gentrification: Racial Identity, Social Mix and Multiculturalism in Toronto’s Parkdale Neighborhood.” Social Identities 24 (6): 707–726. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630.2017.1310039.

- Fainstein, S. S. 2016. “Spatial Justice and Planning.” Readings in Planning Theory, Issue 1980, 258–272. 4th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119084679.ch13.

- Feitosa, F. O., J.-H. Wolf, and J. L. Marques. 2021. Spatial Justice Models: An Exploratory Analysis on Fair Distribution of Opportunities 674–683. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86960-1_51.

- Frenkel, A., and E. Israel. 2018. “Spatial Inequality in the Context of City-Suburb Cleavages: Enlarging the Framework of Well-Being and Social Inequality.” Landscape and Urban Planning 177:328–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.02.018.

- Geras, N. 1985. “The Controversy About Marx and Justice.” New Left Review 150 (3): 47–85.

- Gibson, J. L. 2008. “Group Identities and Theories of Justice: An Experimental Investigation into the Justice and Injustice of Land Squatting in South Africa.” The Journal of Politics 70 (3): 700–716. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381608080705.

- Hadler, R. A., and W. E. Rosa. 2018. “Distributive Justice: An Ethical Priority in Global Palliative Care.” Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 55 (4): 1237–1240. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPAINSYMMAN.2017.12.483.

- Harvey, D. 2009. Social Justice and the City. Athens: The University of Georgia Press.

- Heikkila, E. J. 2001. “Identity and Inequality: Race and Space in Planning.” Planning Theory and Practice 2 (3): 261–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649350120096811.

- He, S. Y., S. Tao, Y. Hou, and W. Jiang. 2018. “Mass Transit Railway, Transit-Oriented Development and Spatial Justice: The Competition for Prime Residential Locations in Hong Kong Since the 1980s.” Town Planning Review 89 (5): 467–493. https://doi.org/10.3828/TPR.2018.31.

- Hibberd, P. n.d. To What Extent Is Utilitarianism Compatible with Christian Theology? Accessed November 22, 2022. https://www.utilitarianism.com/hibberd/index.html.

- Israel, E., and A. Frenkel. 2020. “Justice and Inequality in Space—A Socio-Normative Analysis.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 110 (May 2019): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.12.017.

- Jonkman, A., and L. Janssen-Jansen. 2018. “Identifying Distributive Injustice Through Housing (Mis)match Analysis: The Case of Social Housing in Amsterdam.” Housing Theory & Society 35 (3): 353–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2017.1348392.

- Kamas, L., and A. Preston. 2012. “Distributive and Reciprocal Fairness: What Can We Learn from the Heterogeneity of Social Preferences?” Journal of Economic Psychology 33 (3): 538–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JOEP.2011.12.003.

- Karni, E., and Z. Safra. 2002. “Individual Sense of Justice: A Utility Representation.” Econometrica 70 (1): 263–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0262.00275.

- Kellogg, C. 1998. “The Messianic without Marxism: Derrida’s Marx and the Question of Justice.” Cultural Values 2 (1): 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/14797589809359287.

- Kelsen, H. 1999. General Theory of Law and State, 516. https://books.google.com/books/about/General_Theory_of_Law_and_State.html?hl=pt-PT&id=D1ERgDXEbkcC.

- Knudsen, J. K., L. C. Wold, Ø. Aas, J. J. Kielland Haug, S. Batel, P. Devine-Wright, M. Qvenild, and G. B. Jacobsen. 2015. “Local Perceptions of Opportunities for Engagement and Procedural Justice in Electricity Transmission Grid Projects in Norway and the UK.” Land Use Policy 48:299–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.04.031.

- Kunzmann, K. R. 1998. “Planning for Spatial Equity in Europe.” International Planning Studies 3 (1): 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563479808721701.

- Kymlicka, W. 2002. Contemporary Political Philosophy: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1086/293609.

- Lefebvre, H. 1991. “The Production of Space.” In The Production of Space. John Wiley & Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203132357-14.

- Lefebvre, H. 1996. The Right to the City. Edited by E. Kofman & Elizabeth Lebas. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Levine, D., and M. Aharon-Gutman. 2022. “The Social Deal: Urban Regeneration As an Opportunity for In-Place Social Mobility.” Planning Theory 22 (2): 154–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/14730952221115872.

- Liebig, S., S. HHlle, and M. May. 2016. “Principles of the Just Distribution of Benefits and Burdens: The “Basic Social Justice Orientations” Scale for Measuring Order-Related Social Justice Attitudes.” SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2778031.

- Macintyre, S., L. Macdonald, and A. Ellaway. 2008. “Do Poorer People Have Poorer Access to Local Resources and Facilities? The Distribution of Local Resources by Area Deprivation in Glasgow, Scotland.” Social Science and Medicine 67 (6): 900–914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.029.

- Marques, J., J. Wolf, and F. Feitosa. 2020. “Accessibility to Primary Schools in Portugal: A Case of Spatial Inequity?” Regional Science Policy & Practice 13 (3): 693–707. n/a(n/a. https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12303.

- Márquez, M. A., E. Lasarte, and M. Lufin. 2019. “The Role of Neighborhood in the Analysis of Spatial Economic Inequality.” Social Indicators Research 141 (1): 245–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1814-y.

- Metspalu, P., and D. B. Hess. 2017. “Revisiting the Role of Architects in Planning Large-Scale Housing in the USSR: The Birth of Socialist Residential Districts in Tallinn, Estonia, 1957–1979.” Planning Perspectives 33 (3): 335–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2017.1348974.

- Mill, J. S. 1863. Utilitarianism. London: Parker, son, and Bourn.

- Miller, D. 1999. Principles of Social Justice. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Millgram, E. 2000. “Mill’s Proof of the Principle of Utility.” Ethics 110 (2): 282–310. https://doi.org/10.1086/233270.

- Mooney, G. 1987. “What Does Equity in Health Mean?” World Health Statistics Quarterly 40 (4): 296–303.

- Morrill, R. L., and J. Symons. 1977. “Efficiency and Equity Aspects of Optimum Location.” Geographical Analysis 9 (3): 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-4632.1977.tb00575.x.

- Muñoz, S. 2018. “Urban Precarity and Home: There Is No “Right to the City.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108 (2): 370–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2017.1392284.

- Nassir, N., M. Hickman, A. Malekzadeh, and E. Irannezhad. 2016. “A Utility-Based Travel Impedance Measure for Public Transit Network Accessibility.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 88:26–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2016.03.007.

- Nozick, R. 1973. “Distributive justice.” Philosophy & Public Affairs 3 (1): 45–126. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2264891.

- Nozick, R. 1974. Anarchy, State, and Utopia. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Nuvolati, G. 2009. Quality of Life in Cities: A Question of Mobility and Accessibility BT - Quality of Life and the Millennium Challenge: Advances in Quality-Of-Life Studies, Theory and Research. Edited by V. Møller & D. Huschka. 177–191. Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-8569-7_12.

- Nyholm, S., and J. Smids. 2016. “The Ethics of Accident-Algorithms for Self-Driving Cars: An Applied Trolley Problem?” Ethical Theory and Moral Practice 19 (5): 1275–1289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-016-9745-2.

- Nylund, K. 2014. “Conceptions of Justice in the Planning of the New Urban Landscape - Recent Changes in the Comprehensive Planning Discourse in Malmö, Sweden.” Planning Theory and Practice 15 (1): 41–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2013.866263.

- Oppenheimer, J. O. 2012. “Principles of Politics: A Rational Choice Theory Guide to Politics and Social Justice.” https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139053334.

- Paley, W., and R. Faulder. 1785. The Principles of Moral and Political Philosophy. https://philpapers.org/rec/PALTPO-25.

- Panzera, D., and P. Postiglione. 2020. “Measuring the Spatial Dimension of Regional Inequality: An Approach Based on the Gini Correlation Measure.” Social Indicators Research 148 (2): 379–394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02208-7.

- Park, J., D. Lee, C. Park, H. Kim, T. Jung, and S. Kim. 2017. “Park Accessibility Impacts Housing Prices in Seoul.” Sustainability 9 (2): 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9020185.

- Pereira, R. H. M., T. Schwanen, and D. Banister. 2017. “Distributive Justice and Equity in Transportation.” Transport Reviews 37 (2): 170–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2016.1257660.

- Perez-Mayo, J. 2019. “Inequality of Opportunity, a Matter of Space?” Regional Science Policy & Practice 11 (1): 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12181.

- Phang, S. Y. 2010. “Affordable Homeownership Policy: Implications for Housing Markets.” International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis 3 (1): 38–52. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538271011027069.

- Pigou, A. C. 1932. The Economics of Welfare. London: Macmillan.

- Preston, J., and F. Rajé. 2007. “Accessibility, Mobility and Transport-Related Social Exclusion.” Journal of Transport Geography 15 (3): 151–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JTRANGEO.2006.05.002.

- Prosser, T. 2005. “The Limits of Competition Law: Markets and Public Services.” The Limits of Competition Law: Markets and Public Services 1–292. https://doi.org/10.1093/ACPROF:OSO/9780199266692.001.0001.

- Rauhut, D. 2018. “A Rawls-Sen Approach to Spatial Injustice.” Social Science Spectrum 4 (3): 109–122.

- Rawls, J. 1971. A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Rezende, R., and H. Heynen. 2021. “Slutwalks in Brasília. The Utopia of an Egalitarian City and Its Gendered Spaces.” 9 (4): 606–624. https://doi.org/10.1080/20507828.2021.1866326.

- Rodriguez-Lara, I., and L. Moreno-Garrido. 2012. “Self-Interest and Fairness: Self-Serving Choices of Justice Principles.” Experimental Economics 15 (1): 158–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10683-011-9295-3.

- Schaefer, D. L. 2007. “Procedural Versus Substantive Justice: Rawls and Nozick.” Social Philosophy and Policy 24 (1). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265052507070070.

- Sen, A. 2009. The Idea of Justice. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Stark, W. 1941. “Liberty and Equality Or: Jeremy Bentham as an Economist.” The Economic Journal 51 (201): 56. https://doi.org/10.2307/2225646.

- Uwayezu, E., and W. T. de Vries. 2019. “Scoping Land Tenure Security for the Poor and Low-Income Urban Dwellers from a Spatial Justice Lens.” Habitat International 91:102016. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HABITATINT.2019.102016.

- Weirich, P. 1983. “Utility Tempered with Equality.” Noûs 17 (3): 423. https://doi.org/10.2307/2215258.

- Wolff, J. 1997. An Introduction to Political Philosophy. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Yuan, F., Y. D. Wei, and J. Wu. 2020. “Amenity Effects of Urban Facilities on Housing Prices in China: Accessibility, Scarcity, and Urban Spaces.” Cities 96:96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.102433.

- Yunda, J. G., and B. Sletto. 2017. “Property Rights, Urban Land Markets and the Contradictions of Redevelopment in Centrally Located Informal Settlements in Bogotá, Colombia, and Buenos Aires, Argentina.” Planning Perspectives 32 (4): 601–621. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2017.1314792.