Abstract

Purpose

Early intervention based on principles of cross-situational statistical learning (CSSL) for late-talking children has shown promise. This study explored whether parents could be trained to deliver this intervention protocol with fidelity and if they found the intervention to be acceptable.

Method

Mothers of four English-speaking children aged 18–30 months who scored <10th centile for expressive vocabulary were recruited to an 8-week group training program. Parents were taught principles of CSSL and asked to perform 16 home treatment sessions (30 minutes each) in total, providing auditory bombardment of target words in full sentences at high dose number and syntactic variability, using a range of physical exemplars. Home diaries and two videotaped sessions measured treatment fidelity. Pre- and post-treatment questionnaires measured acceptability.

Result

One parent discontinued the study after the second group training session. Three parents completed 15/16 group training sessions and reported completing 87% of home sessions. Two parents demonstrated implementing the intervention as per the target dose number by the first fidelity session (Weeks 2/3), and the third parent was very close to meeting target dose number by the second fidelity session (Weeks 7/8).

Conclusion

Parents can be trained to deliver an intervention based on cross-situational statistical learning principles.

Introduction

Children are described as late talking when they acquire spoken language at a slower rate than their typically-developing peers (Hawa & Spanoudis, Citation2014). While this term typically focuses on expressive language production, delays in receptive vocabulary, gesture, play skills, or speech sound production may also co-occur (Hodges et al., Citation2017; Olswang et al., Citation1998). Diagnostic criteria for late talking can vary but is often defined as producing less than 50 words and/or no two-word combinations at 24 months of age, or scoring below the 10th percentile in a parent-report expressive vocabulary checklist (Desmarais et al., Citation2008). Late talking occurs in approximately 13% of Australian children (Zubrick et al., Citation2007), with around half of these continuing to have an ongoing language impairment (Sunderajan & Kanhere, Citation2019). Research suggests that children with language disorders risk negative social, health, education, and employment outcomes in later life (Conti‐Ramsden et al., Citation2018).

Current treatments for late talkers

Early intervention is recommended in the late-talking population to promote language development and reduce the risk of ongoing impairment/s. Intervention approaches frequently take the form of a speech-language pathologist coaching another person, typically a parent, to promote language or communication skills. Such training is thought to encourage generalisability to everyday communication skills, and to be cost effective, due to less direct service provision by speech-language pathologists (Brown & Woods, Citation2015; Roberts & Kaiser, Citation2011). These existing treatment approaches are broadly effective (Roberts et al., Citation2019), with intervention producing significant effect sizes on children’s expressive language skills (Heidlage et al., Citation2020), with less evidence for receptive language (Carson et al., Citation2022).

A new potential treatment approach

In Citation2014, Alt and colleagues described late talkers as a population “characterized by an ineffective word learning system” (p. 2). They sought to improve upon previous treatment approaches by experimenting with a new method, based on the principles of cross-situational statistical learning (CSSL), which occurs via the implicit recognition of recurring patterns in others’ speech (Saffran, Citation2020). Regularities in speech segments, syllables, words, and prosody are implicitly matched with the recurrence of the physical context (e.g. the objects/actions in view) and the social context (e.g. the speaker’s eye gaze) of the interaction. This allows the child to learn word boundaries, word meaning, lexical category, and grammatical structure. Two key factors have been identified as important to the success of CSSL and were incorporated into the treatment design of Alt and colleagues: dose and variability (Alt et al., Citation2012; Plante & Gómez, Citation2018). A high dose number, provided by the repetition of a target word (in complete sentences) provides a salient and consistent phonological pattern to be tracked. Variability is comprised of both physical variability, seeing different examples of the physical referent of the target in contrast to other referents, and linguistic variability, where the target is presented in a variety of sentence types and positions within the sentence. High dose and variability are thought to provide maximal opportunities for the phonological form of the target to be tracked across different situations (social and physical), aiding word acquisition in language learners. In summary, the treatment devised by Alt et al. (Citation2014) attempted to enhance CSSL via the clinician using a target word multiple times in complete sentences within a session. The target word was also placed in different positions within sentences and in a variety of sentence types to ensure linguistic variability. Within the interactions, the target word was presented with multiple physical referents that varied by size, shape, or other semantic features (e.g. a soft bear, a large bear, a cartoon bear, a picture of a real bear).

Cross-situational statistical learning and children who are late to talk

To investigate an intervention designed around the principles of CSSL, Alt et al. (Citation2014) conducted a study whereby four late-talking toddlers (23–29 months old) were provided with twice weekly therapy administered by a clinician. Target words were used in treatment with a matched set of words used for controls, which were not spoken. Target words were presented with high physical variability (at least five different physical examples and contexts; different toys, pictures etc.), high linguistic variability (different sentence types and positions), and high dose number (at least 64 times) by the clinician. After the 7-to-10-week intervention period, the participants learnt significantly more target words than control words and showed average untreated vocabulary gains of approximately 21 words per week. It was concluded that the treatment appeared effective, but further research was required to identify which factors caused the improvements.

Further research by Alt and colleagues (Alt et al. Citation2020) compared the treatment outcomes of 24 late-talking children (aged 25–41 months) following a CSSL-based intervention. In this study, the dose number was also manipulated between groups, comparing three target words heard 90 times per session, to six target words heard 45 times per session. A delayed start for a subset of participants (n = 14) was used to control for maturation effects. This protocol, named Vocabulary Acquisition and Usage for Later Talkers (VAULT), was also found to be effective, with treatment word effect size being larger than the control word effect size. An average of 6.14 new words per week was learnt by the participants, with no significant difference between the two dose conditions, suggesting that precise dose number to instigate word learning remains unclear. Successful replication of this approach in other laboratories was performed by Munro et al. (Citation2021) with three English-speaking toddlers, and by Ng et al. (Citation2020) in three Cantonese-speaking toddlers.

Whilst this approach has demonstrated early promise, clinician-implemented treatment can be logistically and economically challenging due to long waitlists currently experienced for speech pathology services in Australia and internationally (Ruggero et al., Citation2012). A recent systematic review of intervention for late talkers concluded that clinician-delivered and parent-delivered treatments have comparable effects on child language development (DeVeney et al., Citation2017). Parents often respond positively to training for these interventions, demonstrating higher responsiveness and rates of communication with their children (Roberts & Kaiser, Citation2011).

As such, in Citation2023, Mettler and colleagues conducted a feasibility study investigating a caregiver-implemented version of the VAULT protocol via telehealth. They recruited five late-talking toddlers and their caregivers. Mettler et al. provided self-paced online training modules with remote coaching, aiming for 68 doses per target, at a pace of nine doses per minute, in coached and individual sessions. They observed high fidelity to the VAULT protocol, alongside a higher proportion of treatment words learnt by children compared to control words. This suggests that parents can be trained to implement the CSSL techniques described by Alt and colleagues (Citation2014) with fidelity. However, the 1.5 hour individual meetings with a clinician, and the eight individual parent coaching sessions online with three clinicians present, made it a relatively high-cost intervention.

If groups of parents can be trained to implement the CSSL techniques with fidelity, without individual coaching, and find the experience to be acceptable, then such an approach may be a viable alternative to the higher-cost method described by Mettler et al. (Citation2023). Such confirmation is required before any larger-scale research takes place, to examine any clinical effectiveness or even additional benefits common to parent group-training, such as child socialisation and social support for the family (Crnic & Stormshak, Citation1997).

Aims of the study

The aim of this study was to explore whether parents could be trained to deliver the intervention found to be successful by Alt et al. (Citation2014), Munro et al. (Citation2021), and Ng et al. (Citation2020) as a home-based, parent-implemented model. It explored whether parents could be trained to carry out the treatment with fidelity to the protocol, and whether they found the intervention to be acceptable for their late-talking children. Fidelity was measured against 64 doses per session per target word, akin to Alt et al. (Citation2014). This number is under investigation and may be in excess of what is required, as indicated by Alt et al. (Citation2020) where 45 doses per word was sufficient. Consequently, fidelity is not measured as binary (not achieved/achieved) but considered linearly, exploring how many doses parents could attain in the recorded sessions.

Method

Recruitment

Approval was granted by the Edith Cowan University Human Research Ethics Committee for this research project. Participants were recruited between April–May 2021 via social media advertising and emails to professional networks of the research team, with snowballing to other interested parties. Participants provided written informed consent on behalf of themselves and their children, who are all referred to by pseudonyms in this manuscript.

Participants

Four male English-speaking participants aged between 18–30 months were included. They met the following inclusion criteria: (a) a score of <10th percentile on the Australian English Communicative Development Inventory (OZI; Kalashnikova et al., Citation2016), (b) speech produced clearly enough to be understood as word attempts by researchers, and (c) families willing to follow the intervention protocol and not undertake any other treatment during the study period. Children were excluded if parents reported they were born preterm, had a history of hearing loss, spoke a language other than English, or had a known diagnosis or disorder other than late talking. One family discontinued the study after the second group training session (David), therefore his data are not included in all analyses.

The ages, family demographics, and pre-intervention receptive and expressive language skills of the child participants are detailed in . All the children were first born. Adam, Ben, and Charlie lived at home with two parents and their mothers were pregnant with their second child. David primarily lived at home with his mother and younger sister, but also spent time at his father’s house. All parents expressed concern about their child’s expressive language skills, but not with their child’s receptive language abilities. Parental concern for their child’s expressive language skills were rated on a Likert scale (How severe are your child’s language difficulties?), ranging from not at all to very severe.

Table I. Demographic details and language skills of participants.

Ben and Charlie’s parents spoke an additional language; however, they exclusively spoke English in the home and to their children. Charlie had received previous language intervention but had ceased this prior to the commencement of the study and did not attend any other therapy sessions for the duration of the treatment period. Two of the four children had a family history of language difficulties: One child’s mother was a late talker due to possible hearing difficulties (Adam) and another child’s maternal grandfather was a late talker for reasons unknown (Charlie).

Personnel

The research team comprised of two final year speech pathology student clinicians, who delivered the group training sessions under the supervision of the research team (both Certified Practising Speech Pathologists, Speech Pathology Australia).

Procedures

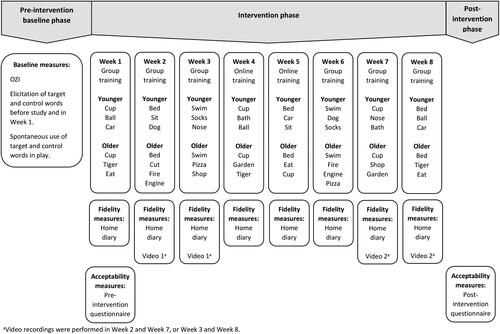

The study comprised three phases: pre-intervention baseline, intervention, and post-intervention, as detailed in .

Pre-intervention baseline phase

Target and control word selection

The research team chose 10 pairs of target and control words for each participant (see ). To enable common target words to be used in the group training, three target words were shared by all participants. A further seven word pairs were used for the two youngest children, and different seven word pairs used for the two older children (see ).

Table II. Target and control words for younger and older children.

Parents confirmed that their child understood all target and control words but did not produce them expressively. Target words were selected based on their relevance and age appropriateness. Control words were matched as closely as possible to target words in terms of semantic category, syllable length, word class (e.g. noun or verb), and age-related acquisition trajectories according to the Stanford Wordbank Item Trajectories (Frank et al., Citation2017), with target and matching control words generally acquired within 2 months of each other. Word lists consisted mainly of nouns, with one or two verbs, as typical for an early English vocabulary (Kim et al., Citation2000).

Baseline measurement

In total, four baseline measures were implemented for each child prior to intervention commencing, to ensure that both target and control words were not yet spoken by participants. Firstly, parents completed an OZI (Kalashnikova et al., Citation2016) on study enrolment. Secondly, children’s spontaneous production of words was probed by presenting colour photo cards of the target and control words in random order, together with spoken cloze phrases (e.g. “the girl is …”) or questions (e.g. “what’s this?”). Thirdly, children’s spontaneous word use was transcribed from a language sample during play with their caregivers and the clinician. Finally, target and control words were again probed at the beginning of the first group training session. If a target or control word was found to be acquired during any of the baseline checks, another word was chosen from the initial OZI and three subsequent baseline checks were then performed.

Intervention phase

Treatment protocol

Following the baseline phase, participants were asked to attend one group training session per week for 8 weeks and complete two home treatment sessions per week with their child. Parents were advised that the parent who attended all the group training sessions had to administer the home treatment (i.e. not another parent or caregiver). Children attended the group training sessions with their parent in a research clinic in Joondalup, Western Australia. Two weeks were allocated at the end of the treatment period, to allow for catch up sessions for missed training sessions, if required.

Group training structure

At each group training session, three target words were assigned for the coming week in the two home treatment sessions. Once all 10 words had been targeted, the words were cycled through again in the same order (see ). The group training sessions consisted of the following structure, which was repeated each week:

Discussion of the experiences of completing the home treatment sessions (except the first group training session). This was intended to promote a shared experience and to allow parents to learn from each other (Moseley Harris, Citation2021).

Discussion of the statistical learning protocol as described in Alt et al. (Citation2014). This included education about the key requirements of high dosage of the target word (at least 64 doses during the home treatment session), using syntactic variability (putting the target word at the beginning, middle, and end of sentences), and the importance of a variety of exemplars (toys, books etc.). PowerPoint slides were used for visual aids.

One of the target words shared by all participants was demonstrated to the whole group, by both clinicians, either via role-play or by interacting with one of the children.

Parents and children were then split into younger and older groups, and one of the clinicians discussed the two additional target words for that week with the smaller group. Parents and clinicians devised ways to incorporate the dose and variability principles into home play, and parents were encouraged to take notes to use as prompts during home treatment sessions.

Resources associated with the target words were used for demonstrations and offered on loan to the participants to ensure that they had sufficient variability in physical exemplars at home to effectively deliver the protocol. These included toys, books, and colouring pages.

COVID-19 treatment modifications

Due to COVID-19 restrictions, two group training sessions were instead delivered as video recorded PowerPoint presentations (see ). Links to these videos were emailed to the parents, along with online resource packs, to support them to deliver the home treatment sessions without the usual in-person training. These were sent to the families on the days that the group training sessions would ordinarily take place, with the offer of remote telephone access to the researchers.

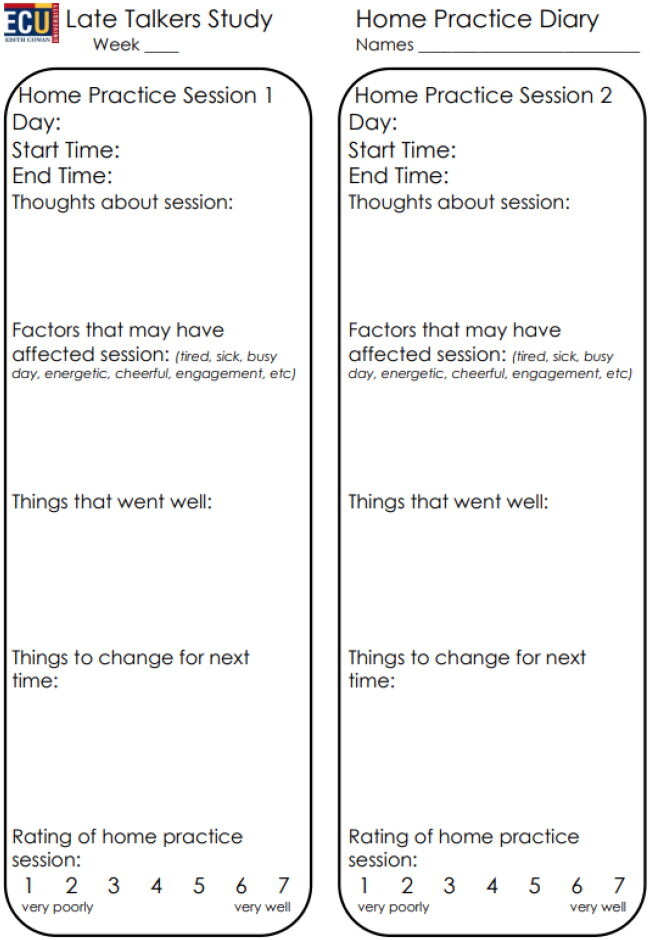

Treatment fidelity

Parents were asked to complete a weekly home diary to identify how many home treatment sessions took place (see Appendix). This diary was brought to the group training sessions, for parents to make notes about activity ideas and generate sample sentences for the upcoming home treatment sessions. The diaries were also used as a stimulus for self-reflection in the following week’s group training session, discussing the positives from the previous week and troubleshooting any difficulties experienced.

In Weeks 2/3 and 6/7 (see ), a video recorded home treatment session took place in the clinic to measure treatment fidelity. These sessions occurred after the group training session in a separate room, unobserved by clinicians, using a variety of toys and resources provided by the clinic.

Parent acceptability

Two questionnaires were completed by parents: one after the first group training session (pre-intervention) and one following study completion (post-intervention). The questionnaire was adapted from a post-acceptability questionnaire for a parent-delivered intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder (Keleher, Citation1999). The questionnaire consisted of 20 statements, which were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree), with several themes repeated throughout the questionnaire to support validity of responses.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to measure adherence to group training sessions and home treatment sessions via home diaries. The video recordings of parent-delivered treatment sessions were transcribed orthographically and coded by the clinicians. Dose number fidelity was calculated by identifying how often the target words and control words were spoken by the parent during the treatment session. A team member involved in the research (the fourth author) reviewed the dose number and coding. Any discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached. This was compared to a target word dose of 64 productions per session, and a control word dose of less than five productions per session. Variability fidelity was measured by tallying from the transcription how many times the target word appeared in each of the sentence types: declarative, interrogative, imperative, and exclamatory. The difference between declarative and exclamatory sentences was determined by intonation. For the acceptability questionnaire, descriptive statistics of Likert scale responses were used to evaluate participant acceptability and overall percentage agreement was calculated across participants.

Result

Participants

In the pre-treatment questionnaire, Anna was not particularly concerned about her child’s language delay, giving her concern a neutral weighting (3/5 on the Likert scale). Becky and Christina were both quite concerned (4/5) and Danielle was the most concerned about her son’s language delay (5/5).

Attrition

One of the families discontinued their involvement in the study after two group training sessions (Danielle and David). Follow up emails and phone calls were made, however, the family did not respond.

Group training session attendance

With the exception of Danielle and David, all families attended five of the six in-person group training sessions offered and reported completing the two online training sessions. The sessions that were not attended were due to child or family illness and were not made up in the additional 2 weeks provided at the end of the treatment period.

Home treatment sessions

One family reported completing all 16 (100%) of the home treatment sessions (Anna). The other two completed over 85% of the sessions (Christina: n = 15, 94%; Becky: n = 14, 87%), reporting that illness was the main reason for not completing all the sessions. Becky and Christina returned their diary entries for all sessions, while Anna returned 12 of the 16 diary entries.

Research Question 1: Can parents be successfully trained in administering an intervention to their children which presents target words with high dose and variability?

Dose

The results of the two 30-minute video recorded treatment sessions in Week 2/3 and Week 7/8 are shown in . The mean dose number across all target words for all families was above the target of 64 doses in both sessions. Anna shared the session time evenly amongst the three target words, as demonstrated by the low standard deviation, while Becky and Christina’s dose numbers were more variable. Christina found it more difficult to generate sentences for some target words, with one word in the first session only reaching a dose number of 27. In her second video recorded treatment session, one target word remained under the target of 64 doses, although closer at 61.

Table III. Total, mean, range, standard deviation (SD), and average per minute dose for all participants in video recorded practice sessions.

Danielle was not able to stay for the full length of the first recorded treatment session due to childcare issues. However, during the 20 minutes she was available, she split the time evenly amongst the three words, averaging 7.5 target words per minute. If that rate had been maintained for the full 30 minutes, she would have met the 64 dose number target.

Variability

As seen in , the proportions of sentence types used in the recorded treatment sessions were similar across parents and sessions, except the proportion of interrogative sentences, which increased for Becky and Christina between the sessions. Target words were used in different sentence positions, also being similar across parents and sessions, as seen in . Becky and Christina more commonly used target words in the middle of sentences in the first recorded session, but the final word position was more common in the second recorded session.

Table IV. Totals and percentages for different sentence types used to present the target words for all participants in video recorded practice sessions.

Table V. Totals and percentages of different sentence positions used to present the target words in video recorded practice sessions for the three participants who completed the intervention.

Research Question 2: Will the treatment program be acceptable to parents?

Pre-treatment acceptability questionnaire

As seen in , all parents were enthusiastic about taking part in the study after the first group training session and were willing to carry out the intervention, believing it would be appropriate, effective, time efficient, and affordable (all scored as 5 on the Likert scale, equating to strongly agree). They also felt they had a clear understanding of the treatment (average score = 5), although some parents had concerns about the time it would take for the home treatment sessions (average score = 4.34, with 5 being little time will be needed).

Table VI. Results of the acceptability survey before and after the study.

Post-treatment acceptability questionnaire

The three remaining parents remained positive about the treatment program at the end of the intervention period (see ). Parents continued to report that they strongly agreed about understanding the treatment, being willing to carry out treatment, affordability of the treatment, and a lack of concern about side effects—responses that were unchanged from the pre-treatment questionnaire. Ratings for the suitability of treatment, time efficiency, liking of treatment procedures, and fitting the family routine all declined from pre-treatment, but remained positive (rated as agree to stronglyagree).

Discussion

The study results indicated that two of the three parents were able to implement the treatment at the target dose number and variability after the first two or three group training sessions. A third parent did not reach the target dose number for all treatment words, but her mean dose for all words (68) was higher than the target dose (64) during the first recorded treatment session and was near to the target dose (61) for all treatment words by her second recorded treatment session. Interestingly, whilst proficient, English was not this participant’s (Christina’s) first language and she reported difficulties in creating complex sentences for some of the words when she knew she was being recorded. Further training over the weeks seemed to result in demonstrated and reported growth in her confidence to administer the treatment. The fourth parent did not complete the group training. However, during her first partially recorded treatment session, she demonstrated a dose rate per minute with the potential to meet the target dose number in a full-length session.

Acceptability

Three out of the four participants found the protocol acceptable. As participants had self-nominated for recruitment, they may have been more inclined to engage in therapy and view it positively. It was unfortunate that feedback was not received from the parent who withdrew, as her insights may have added valuable perspectives to evaluate the intervention. Additionally, with such a small number of participants, it was difficult for questionnaire responses to be completely anonymous and this may also have influenced responses. While ratings did decline for some acceptability measures, they remained in the agree to strongly agree category and the decline does not appear significant. Only one participant had prior experience with speech pathology before this study, so pre-treatment expectations may have been overly optimistic.

Group training considerations

The success of the group training may be due to several factors. Firstly, principles of adult learning theory suggest that the greatest gains are seen when adults are provided with information, given opportunity to practice, and to evaluate and reflect on their use of techniques. They also benefit from having the information presented in multiple ways (Friedman et al., Citation2012). This study attempted to provide different mediums of demonstration, including live demonstrations with the children, video of a clinician, and role-play by the two clinicians. The children were present at the training, which is not always typical of parent group training, allowing the parents to practice with clinician support immediately after being given instruction.

This study utilised a training approach, rather than the training and coaching approach used by Mettler et al. (Citation2023). Training consists of education and demonstration of the treatment, while coaching generally consists of parents delivering treatment in view of a clinician, who provides feedback on performance and guidance for future sessions. In this study, clinicians were not present in the recorded treatment sessions, nor were participants given direct feedback on their performance. Coaching may be seen as a crucial part of parent interventions by some (Friedman et al., Citation2012), as it supports parents to make specific changes to their interaction (Ebbels et al., Citation2019). However, this component may be seen as critiquing the parent’s style of interaction, which may not be the source of the child’s language-learning difficulties. This may inadvertently lead parents to believe that their parenting is at fault for their child’s delayed language development (Allen & Marshall, Citation2010). Whilst feedback was not given to the parents, they were made aware that dose number and variability would be measured from these recordings. This may have produced an indirect incentive to attend to the education component and possibly assisted with the parents’ learning process (Friedman et al., Citation2012).

Whilst clinician feedback was not given, the opportunity for self-evaluation throughout the program was frequent. A weekly home diary asked specific questions about successes and challenges of each home treatment session, and discussions were held in the group training sessions. This is akin to other research, demonstrating that self-reflection and goal setting are valuable within adult learners, particularly when applying new skills to novel situations (Dunst & Trivette, Citation2009). Unfortunately, the use of self-evaluation by participants was not measured within this study as a contributing variable. Future research may benefit from the use of participant focus groups pre- and post-treatment in order to evaluate such behaviour.

The study was originally designed whereby treatment and control word pairs would be shared between participants, to assist the process of demonstration by clinicians and sharing ideas between participants for treatment. In practice, it was challenging to find words that met the inclusion criteria for all participants (receptively known, not expressively used, common nouns or verbs, age appropriate), and remained unspoken during all baseline checks. Future studies may also find this challenging, especially when coordinating greater numbers of participants within a group. It may be beneficial to evaluate whether it is logistically easier to group children by age or expressive vocabulary size, or whether a group training approach can be delivered whilst also giving each child an individual set of target words. The group training session procedure was also impacted by only having one child in the older group. It was intended that the mothers in the two groups would work together, sharing ideas for activities and practising generating sentences collaboratively (Moseley Harris, Citation2021), but this was not possible once Danielle withdrew.

Participants reported that the group training sessions were effective, they had a good understanding of the reasoning behind the techniques, and the confidence to carry out the home treatment sessions. Furthermore, the attendance at group training sessions and the reported completion rates of home treatment sessions were high, similar to Mettler et al. (Citation2023). The flexibility to offer makeup sessions in both studies was likely a contributing factor, and supported families with young children, where illness is common.

Comparison to other parent-training programs is difficult due to study heterogeneity. In a systematic review, DeVeney et al. (Citation2017) found training length for similar programs varied from 11 weeks to 6 months, with a mean of 14.75 sessions. Specific parent-training programs such as the LENA protocol (Elmquist et al., Citation2021) require up to 13 weekly sessions, each teaching a different technique.

There is only one other study (Mettler et al., Citation2023) that also investigated parent-delivered CSSL-based intervention. Both programs recruited late-talking toddlers, ran for 8 weeks, targeted the same number of words, and used similar intervention protocols. But unlike Mettler et al. (Citation2023), this study conducted training mostly in-person, not via live telehealth, and parents received group training with no individual coaching. The present study reinforced the same concepts each week (dose number and variability), whereas Mettler and colleagues varied the concept to be learnt weekly. Unlike some other parent-training or coaching programs, both studies did not aim to change overall daily parental interaction style, but instead only focused upon increasing visual and verbal input within time-limited treatment sessions at home. The simplicity and/or achievability of the treatment method may have assisted in the understanding, fidelity, and success of implementation.

Limitations

This was a small pilot study of four participants. While the results support further investigation of this approach in future research, they do not identify whether this treatment had any clinical effect, or whether different participants would respond in the same way. The success of the parent training and the resultant treatment fidelity may be moderated by factors including languages spoken at home, socioeconomic status, level of family support, number of dependents, and education level of the parent. The background demographics of the present participants were homogenous: all White, single-child families, and two parents with above high-school level education.

Recording treatment sessions at the clinic removed the technical difficulties or non-compliance issues experienced in the study by Zuccarini et al. (Citation2020), where only 63% of parents returned the two required videos of home sessions. However, only two opportunities per parent were provided to calculate fidelity. It is possible that these treatment sessions differed to those performed in the family home. Being in an unfamiliar environment, with the only toys presented being ones that were relevant to the target words, may have made the children more attentive and reduced distractions for parent and child. The knowledge that the treatment session was being recorded may also have impacted the session in various ways, such as the Hawthorne effect. However, Melvin et al. (Citation2021) suggest that video recording results in less behaviour change than being observed directly.

Due to the treatment sessions taking place at home, a data tracker was not used to precisely calculate dose number. Therefore, this study does not contribute to the exploration of effective dose number for new word learning. However, it does demonstrate the potential for parents to be trained in this approach and use it with some fidelity at home.

Conclusion

From this small pilot study using a group-training approach, it appears possible to teach parents of late-talking toddlers to provide statistical learning intervention and that they find it an acceptable approach. Treatment fidelity indicates that two of the parents learnt to implement the intervention as per the required protocol within a relatively short period (two/three group training sessions) and the third parent was very close to meeting target dose after seven/eight group training sessions. Further investigation of the intervention’s efficacy and acceptability is required with a larger and more diverse population.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no competing interests

References

- Allen, J., & Marshall, C. R. (2010). Parent–Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) in school-aged children with specific language impairment. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 46(4), 397–410. https://doi.org/10.3109/13682822.2010.517600

- Alt, M., Mettler, H. M., Erikson, J. A., Figueroa, C. R., Etters-Thomas, S. E., Arizmendi, G. D., & Oglivie, T. (2020). Exploring input parameters in an expressive vocabulary treatment with late talkers. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 63(1), 216–233. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_jslhr-19-00219

- Alt, M., Meyers, C., & Ancharski, A. (2012). Using principles of learning to inform language therapy design for children with specific language impairment. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 47(5), 487–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-6984.2012.00169.x

- Alt, M., Meyers, C., Oglivie, T., Nicholas, K., & Arizmendi, G. (2014). Cross-situational statistically based word learning intervention for late-talking toddlers. Journal of Communication Disorders, 52, 207–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2014.07.002

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016) ‘Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) [https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/2033.0.55.001], accessed 10 November 2023

- Brown, J. A., & Woods, J. J. (2015). Effects of a triadic parent-implemented home-based communication intervention for toddlers. Journal of Early Intervention, 37(1), 44–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815115589350

- Carson, L., Baker, E., & Munro, N. (2022). A systematic review of interventions for late talkers: Intervention approaches, elements, and vocabulary outcomes. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 31(6), 2861–2874. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_AJSLP-21-00168

- Conti‐Ramsden, G., Durkin, K., Toseeb, U., Botting, N., & Pickles, A. (2018). Education and employment outcomes of young adults with a history of developmental language disorder. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 53(2), 237–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12338

- Crnic, K., & Stormshak, E. (1997). The effectiveness of providing social support for families of children at risk. In M. J. Guralnick (Ed.), The effectiveness of early intervention (pp. 209–225). Brookes.

- Desmarais, C., Sylvestre, A., Meyer, F., Bairati, I., & Rouleau, N. (2008). Systematic review of the literature on characteristics of late-talking toddlers. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 43(4), 361–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/13682820701546854

- DeVeney, S. L., Hagaman, J. L., & Bjornsen, A. L. (2017). Parent-implemented versus clinician-directed interventions for late-talking toddlers: A systematic review of the literature. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 39(1), 293–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525740117705116

- Dunst, C. J., & Trivette, C. M. (2009). Capacity-building family-systems intervention practices. Journal of Family Social Work, 12(2), 119–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/10522150802713322

- Ebbels, S. H., McCartney, E., Slonims, V., Dockrell, J. E., & Norbury, C. F. (2019). Evidence-based pathways to intervention for children with language disorders. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 54(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12387

- Elmquist, M., Finestack, L. H., Kriese, A., Lease, E. M., & McConnell, S. R. (2021). Parent education to improve early language development: A preliminary evaluation of LENA StartTM. Journal of Child Language, 48(4), 670–698. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000920000458

- Frank, M. C., Braginsky, M., Yurovsky, D., & Marchman, V. A. (2017). Wordbank: An open repository for developmental vocabulary data. Journal of Child Language, 44(3), 677–694. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000916000209

- Friedman, M., Woods, J., & Salisbury, C. (2012). Caregiver coaching strategies for early intervention providers: Moving toward operational definitions. Infants & Young Children, 25(1), 62–82. https://journals.lww.com/iycjournal/Fulltext/2012/01000/Caregiver_Coaching_Strategies_for_Early.4.aspx https://doi.org/10.1097/IYC.0b013e31823d8f12

- Hawa, V. V., & Spanoudis, G. (2014). Toddlers with delayed expressive language: An overview of the characteristics, risk factors and language outcomes. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35(2), 400–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2013.10.027

- Heidlage, J. K., Cunningham, J. E., Kaiser, A. P., Trivette, C. M., Barton, E. E., Frey, J. R., & Roberts, M. Y. (2020). The effects of parent-implemented language interventions on child linguistic outcomes: A meta-analysis. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 50, 6–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.12.006

- Hodges, R., Baker, E., Munro, N., & McGregor, K. K. (2017). Responses made by late talkers and typically developing toddlers during speech assessments. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 19(6), 587–600. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2016.1221452

- Kalashnikova, M., Schwarz, I.-C., & Burnham, D. (2016). OZI: Australian English communicative development inventory. First Language, 36(4), 407–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142723716648846

- Keleher, K. L. (1999). Parental acceptance of behavioural treatments for children with autism. Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto.

- Kim, M., McGregor, K. K., & Thompson, C. K. (2000). Early lexical development in English- and Korean-speaking children: Language-general and language-specific patterns. Journal of Child Language, 27(2), 225–254. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0305000900004104

- Melvin, K., Meyer, C., & Scarinci, N. (2021). Exploring the complexity of how families are engaged in early speech–language pathology intervention using video-reflexive ethnography. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 56(2), 360–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12609

- Mettler, H. M., Neiling, S. L., Figueroa, C. R., Evans-Reitz, N., & Alt, M. (2023). Vocabulary acquisition and usage for late talkers: The feasibility of a caregiver-implemented telehealth model. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 66(1), 257–275. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_JSLHR-22-00285

- Moseley Harris, B. (2021). Exploring parents’ experiences: Parent-focused intervention groups for communication needs. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 37(2), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/02656590211019461

- Munro, N., Baker, E., Masso, S., Carson, L., Lee, T., Wong, A. M.-Y., & Stokes, S. F. (2021). Vocabulary acquisition and usage for late talkers treatment: Effect on expressive vocabulary and phonology. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 64(7), 2682–2697. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_JSLHR-20-00680

- Ng, C. S.-Y., Stokes, S. F., & Alt, M. (2020). Successful implicit vocabulary intervention for three cantonese-speaking toddlers: A replicated single-case design. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 63(12), 4148–4161. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_JSLHR-20-00087

- Olswang, L. B., Rodriguez, B., & Timler, G. (1998). Recommending intervention for toddlers with specific language learning difficulties. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 7(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360.0701.23

- Plante, E., & Gómez, R. L. (2018). Learning without trying: The clinical relevance of statistical learning. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 49(3s), 710–722. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_lshss-stlt1-17-0131

- Roberts, M. Y., Curtis, P. R., Sone, B. J., & Hampton, L. H. (2019). Association of parent training with child language development: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(7), 671–680. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1197

- Roberts, M. Y., & Kaiser, A. P. (2011). The effectiveness of parent-implemented language interventions: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20(3), 180–199. https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2011/10-0055)

- Ruggero, L., McCabe, P., Ballard, K. J., & Munro, N. (2012). Paediatric speech-language pathology service delivery: An exploratory survey of Australian parents. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 14(4), 338–350. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2011.650213

- Saffran, J. R. (2020). Statistical language learning in infancy. Child Development Perspectives, 14(1), 49–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12355

- Sunderajan, T., & Kanhere, S. V. (2019). Speech and language delay in children: Prevalence and risk factors. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 8(5), 1642–1646. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_162_19

- Zubrick, S. R., Taylor, C. L., Rice, M. L., & Slegers, D. W. (2007). Late language emergence at 24 months: An epidemiological study of prevalence, predictors, and covariates. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 50(6), 1562–1592. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2007/106)

- Zuccarini, M., Suttora, C., Bello, A., Aceti, A., Corvaglia, L., Caselli, M. C., Guarini, A., & Sansavini, A. (2020). A parent-implemented language intervention for late talkers: An exploratory study on low-risk preterm and full-term children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 9123. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/23/9123 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17239123

Appendix 1: Home Practice Diary.