ABSTRACT

The purpose of the study is to evaluate the system of dependencies and contradictions between the Forbidden City as an object of cultural heritage and the transformation of the historic environment. The research methodology is based on a comparative study of literary sources and quantitative and qualitative data analysis using the example of the study of the Forbidden City. Based on the analysis of existing concepts, a model for managing the changing historical environment within the framework of the sustainable development of the Forbidden City has been developed. According to the study, the Forbidden City today is between two complex processes related to preserving and transforming the historic environment. In recent years there has been an increase in the number of museums and collections of cultural relics in the urban historical environment of Beijing, which directly contributes to the growth of tourist activity. This model should be based on the interaction of innovative digitalisation tools, intelligent solutions in urban planning, a rational approach and cultural tourism. In practice, this will allow for the maintenance of a more reasonable population density and the rational location of industrial and economic facilities and preserve the traditional aesthetic.

Introduction

In the modern world, the problem of preserving cultural heritage is intertwined with the transformation of the historic environment. Effective regulation of these processes in the context of their sustainable development requires a change in approach to understanding the role and significance of cultural heritage. Many countries around the world aspire to preserve their cultural heritage, however, challenges frequently arise concerning the preservation of its authenticity, as increasingly heritage becomes subject to tourist interests rather than cultural development. This is especially true today of the Forbidden City, which was and remains an essential part of the cultural heritage of modern China.

Atmospheric pollution aggravates the weathering and dilapidation of the ancient buildings of the Forbidden City and reduces the protection of stone carvings from acid rain. It also affects murals. Discolouration is worse now than 20 years ago, though some protective conservation measures have been taken. Meanwhile, anthropogenic impact remains the primary cause of the adverse effects on the preservation of ancient structures. Secondary factors include natural disasters, which, among other occurrences, may arise in particular as a result of lightning strikes.

Today, the process of heritage preservation and management is in the course of complex historical changes due to the transition from a state-monopolised approach to a multi-channel social project in the People’s Republic of China. This is carried out at three levels: across the whole country, within the regions and at a global level.Footnote1 To cope better with the challenges of rapid urbanisation, it is necessary to improve the management of urban heritage by involving local communities in the process. Furthermore, the implementation of an approach based on the historical urban landscape (HUL Recommendation 2011) is of significant importance. This approach relies on well-established community engagement procedures to strike a balance between heritage preservation, socio-economic development, nature conservation, and societal improvement.Footnote2 Based on the above and previously unsolved issues, this study aims to assess the system of dependencies and contradictions at the Forbidden City between its identity as an object of cultural heritage and the current transformation of the historic environment.

Review of Literature

The Forbidden City is an Object of Humanity’s Shared Cultural Heritage

Cultural heritage is not just an object that serves as a link between the past and the future. It has an essential mission symbolising the state’s history and enhancing its national identity.Footnote3 Cultural heritage is a historical relic of natural and human social activity. It is also the heritage of the entire human civilisation and reflects the historical, social, and cultural environment.Footnote4 Cultural and tourist heritage sites also occupy an essential place in the system of sustainable urban development of urban communities. First and foremost, various types of cultural and entertainment facilities exert differentiated effects on spatial agglomeration, closely intertwined with the historical background of Beijing, industrial placement, and the residents’ daily needs. This implies the presence of both social and economic factors which influence the sustainable development of the urban environment, together with certain environmental aspects, such as green open spaces and parks.Footnote5

The central part of the city now represents the relatively well-preserved territory of old Beijing. It stretches 7.8 km in length, starts on the south side of the city from Yongding Gate, then passes through Zhengyang Gate, covers Tian’anmen Square, The Forbidden City, Jingshan Hill, and ends with the Drum Tower and the Bell Tower in the northern sector. Many structures and buildings were built along this line in the old city. This axis rationally and systematically connects the imperial palaces, the Forbidden City, temples and altars, markets, streets of the feudal era and the historical and cultural complex of Tian’anmen Square, built after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.Footnote6

Since 2012, the accessible area of the Palace Museum has increased from 30% to 80% for visitors. Nonetheless, there are specific enclosed spaces for all visitors. In recent years, the Forbidden City has transitioned from being regarded as an isolated ‘monument’ to a comprehensive museum and historical complex integrated into the urban cultural environment.

There is the Palace Museum on the territory of The Forbidden City. The Palace was listed as a World Heritage Site in 1987. First built in the early 1400s, it is notable for the unique style of ancient Chinese architecture and architectural ensemble consisting of more than 900 buildings that are located on 72 hectares of the city, as well as the presence of numerous collections of works of art and imperial paraphernalia, including thrones, palanquins, and costumes.Footnote7

The Forbidden City was a royal palace of the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368–1911). Their history dates back several centuries and the heritage site is one of the world’s largest and best-preserved wooden structures. Thus, the Forbidden City is undoubtedly an invaluable architectural treasure of humankind. At the same time, after almost six centuries of its existence, due to environmental erosion, the historical buildings of the Forbidden City have undergone varying degrees of wear and urgently need conservation to slow down their ageing and destruction.Footnote8

It is also important that the Forbidden City is one of the most valuable historical objects of architectural heritage with rare and unique cultural connotations. Therefore, it is imperative to assess and study changes in the historic environment of the Forbidden City in the context of its preservation as an object of the global heritage of human civilisation.Footnote9

The ancient imperial buildings and the unique culture of the Forbidden City can be a source of unforgettable memories for visiting tourists. At the same time, the development of cultural tourism directly affects the maintenance of its authenticity.Footnote10 As a unique type of cultural heritage museum, The Forbidden City reflects the dependence of its successful preservation on its historical significance realised through the process of historical and cultural interaction in relation to historical memory, aesthetics, and artefacts.Footnote11

Transformation of the Historic Environment in the XX – XXI Century and Its Impact on Cultural Heritage

Maintaining the preservation of cultural heritage and protecting cultural space is an important task to ensure the transfer of tangible and intangible values of civilisation and evidence of past achievements to the next generations. It is also significant for their further use as a strategic resource necessary for sustainable development. The above is quintessentially an issue for countries with a unique cultural heritage, which is often particularly fragile for reasons, including development pressure, exposure to pollution and natural erosion.Footnote12

In the past, the transformation of Beijing’s urban space has ranged from urban planning to intangible cultural heritage. The changes at the turn of the twentieth century reflect this period’s internal and global problems, which combine the complex dilemma of simultaneous urban development and heritage preservation. The modern history of the development of such neighbourhoods as Gulou, Qianmen and Nanluoguxiang shows how the city authorities have entered a new stage of heritage management. This forces them to respond flexibly to the problems of the historic built environment and its representation and to adapt in the best possible way to the rapid transformation of the urban and rural landscape in a complex market economy. Since the 2000s, the primary objective of conservation has been to understand the importance of interaction between the government and the public to improve the preservation of tangible and intangible heritage. An integral urban system of cultural values stems from this interaction, connected with its territory and architecture, which must be maintained and protected. Urban communities are traditionally tied to the sights of their area, which embody their collective memory, which can be displayed in different layers and formed in several dimensions.Footnote13

One of the most difficult issues is gentrification and attempts to find acceptable solutions, given the complex relationship between cultural heritage and development as modern urban infrastructure rapidly develops. It is necessary to prevent the problem of homogeneity caused by the repeated construction of ‘the same images of the city’ and promote cities’ innovative development.Footnote14

The recent case of the revival of a temple in Beijing and the sharp debate that has arisen about the appropriateness of reusing historical heritage illustrates the complex problems that exist. Zhizhu Temple, now known as Beijing Restaurant/Hotel, is in the historic centre near the Forbidden City. In the past, various organisations and factories occupied the temple, though it became empty was abandoned. Seven years ago, the company initiated a project to reconstruct and revitalise the complex. The renovation strategy was based on the idea of reusing the space as a luxury hotel, restaurant, and art gallery. The restoration and reconstruction took five years, and they were awarded the UNESCO Asia-Pacific Prize in the field of cultural heritage preservation in 2012. In fact, the case has attracted criticism from the public and official media. Considering this problem revolves around whether it is appropriate to have a hotel and restaurant in the temple and whether such use is legal.Footnote15

In integrating new digital technologies, the Palace Museum received a wide range of opportunities and significantly improved the communication characteristics of various new media platforms. An official website, microblog, soft text advertising, digital applications, Taobao, cultural products and other digital products were deployed.

All new media platforms can develop together and complement each other. In this process, the uncompromisingly old approach to preserving the heritage of the Forbidden City has been replaced by the adoption of a new image of publicity and openness. Using media content effectively has allowed innovation and ensured brand promotion. Thanks to this, it was possible to provide interested users with information, and popular interpretation and protect valuable relics while promoting sustainable development in the cultural heritage sphere.Footnote16

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The study is based on the concept of sustainable tourism development. Its essence lies in the rational management of available resources, including cultural values, so that the economic, environmental, social, and spiritual needs of the heritage object are met. These include the preservation of historic identity and the complex processes of maintaining environmental sustainability, biological diversity and environmental systems.Footnote17

Sample Study

The authors studied the dependencies and contradictions between the Forbidden City as an object of cultural heritage and the transformation of the historical environment by analysing literary sources and the main conceptual directions of contemporary study. The analysis focused on the Forbidden City as an object of the cultural heritage of world civilisation through visitor numbers, the extent of cultural services and museums and collections of relics. Analysis of existing concepts proposed by Dandan, Bo, and Qian,Footnote18 Mateoc-Sîrb et al.Footnote19and Qin et al.Footnote20 provided the basis for a model for managing the changing historic environment within the framework of the sustainable development of the Forbidden City. This model stems from the generalisation and combination of scientific approaches related to developing modern digital technologies, intelligent gentrification and sustainable urbanisation, and cultural tourism.

Research Limitation

The paper involved studying data from 2008 to 2019 and did not fully cover the period after the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, the problem of transformation of the historical environment requires deeper research and a long period of study of this issue. Furthermore, key issues concerning the ‘monumentalisation’ of the Forbidden City and the broader historical environment of Beijing were not addressed within the scope of this study. They require a more in-depth examination and data analysis.

Statistical Analysis

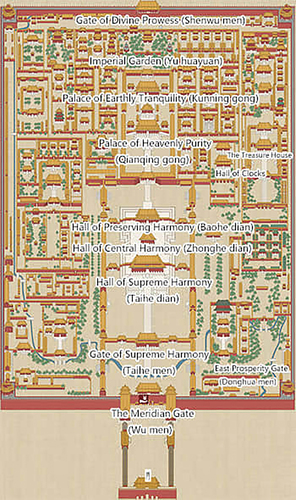

n the paper, the authors studied and analysed data from the Beijing Municipal Bureau of Statistics on the transformation of the historical environment of cultural heritage in Beijing from 1982 to 2020, though the data was only complete for the period 2008 to 2020. In addition, information was used from the Statista web portal on the number of visits to the Forbidden City. The main statistical calculations and regression analysis were carried out using the Microsoft Excel program. Further data on the number of visits to the Forbidden City in 2008, 2009, 2010 and 2011 were derived from the annual report of the Palace Museum. A linear model of the dependence of the level of tourist activity on the degree of development of cultural services, museums, and collections of relics from 2008–2019 was developed. It was tested for adequacy P < .0001 and reliability, and confirmed by a high correlation coefficient.

Beijing: The Evidence Base

Every year, millions of people visit the Forbidden City Museum Complex in Beijing. In 2019, 19.3 million visits were recorded before the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to 17.5 million in the previous year. One of the most visited places in China, this World Cultural Heritage Site is located between two complex processes related to preserving and transforming the historic environment. On the one hand, the substantial influx of tourists contributes to the social and economic aspects of sustainable urban development in Beijing by bolstering tourism revenue. On the other hand, the presence of millions of tourists influences the ecological component of sustainable development. These consequences manifest in increased passenger flow, elevated air pollution from transportation, additional strain on urban infrastructure, and the need to cater to heightened demands for energy and food.

A unique historic environment has been formed in this city with a rich history and culture, which has been transformed in recent decades due to urbanisation and gentrification. Urbanisation with changes in urban development and an increase in population density in different areas of Beijing has become particularly noticeable in the last few decades. This has caused a dilemma for preservation between the old and the new, between historical and cultural space in conditions of accelerated urban development and the growing needs of residents for a comfortable environment. It has also led to the emergence of infrastructural and environmental problems characteristic of large or megacities. In China, amid the recent construction boom and significant urban transformation during the process of industrialisation and urbanisation, the augmentation of heritage sites where preservation or conversion into museums has been a policy consideration. This includes preserved historical structures, architectural complexes, and unique sites and territories, as well as those of archaeological and palaeontological significance. In general, analysis of changes in the urban historical and cultural environment indicates this area of activity is the most promising with state policy improving the level of protection for cultural heritage.

During the period under review, Beijing’s total number of museums and collections of cultural relics has had a steady growth trend. From 2008–2020, the number of museums increased from 148 to 197, and collections of cultural relics were from 3.31 million units to 16.25 million units (Appendix).

The transformation of the historical environment in Beijing directly influences the preservation and development of the Forbidden City. In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of museums and collections of cultural relics in the urban historical environment of Beijing, which directly contributes to the growth of visits to the Forbidden City. Comparing these data using regression analysis for 2008–2019, the authors established a close correlation ().

Figure 1. Dependence of the level of tourist activity on the degree of development of cultural services, museums, and collections of relics in 2008–2019 (r = 0.95; P < .0001).

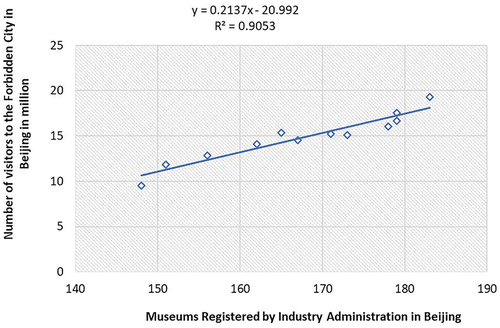

Thus, the presence of more monuments and places of cultural heritage contributes to the growth of tourist activity. The Palace Museum is of considerable historical and cultural interest. It is in the Forbidden City, geographically situated in the centre of Beijing at 1 km north of Tiananmen Square, with its southern gate, the Gate of Divine Power (Shenwumen), facing Jingshan Park. The Palace Museum was the residence of Chinese emperors ().

Established during the Ming and Qing dynasties, the Forbidden City served as a pivotal centre of architectural and cultural construction within the territory of Beijing during the reign of the last two imperial dynasties. The unique layout of palaces, ritual places, government buildings, warehouses, temples, residential quarters, and markets preserved to this day testifies to the presence of a high culture of urban planning in the ancient capital of China and characterises the complex historical landscape of the political and economic system of the feudal-agricultural system of this era.

Over the past few decades, the development of the city has reached a high level of use of natural and historical resources. Currently, numerous historical, cultural, and natural elements characteristic of the imperial era constitute the valuable historical heritage of the Forbidden City, which requires effective management in the changing historical environment ().

Figure 3. Forbidden city map of infrastructure.

The process of formation and development of cultural heritage and its historic environment in the city is a unique and, at the same time, complex interweaving of a variety of traditions and continuity. The ancient cultural heritage of Beijing and its historical environment traditionally form a harmonious landscape in every part of the city, and the most important aesthetic characteristic of the famous historical and cultural Forbidden City. At the same time, there are risks to the city’s cultural heritage and its environment, which come from natural and developmental pressures associated with urbanisation and gentrification. The above is especially true of the territories and spaces near the Forbidden City ().

Figure 4. Satellite map with the typology of Forbidden City map area.

The principal planning policy instrument in the city is the contemporary General Development Plan of Beijing.Footnote21 Requiring authorities maintain a reasonable population density in the urban area that constitutes the cultural heritage and rationally place industrial and economic structures. The Plan serves as the fundamental normative, legal, and political context within which the preservation of the Forbidden City takes place. China has invested over 7 billion yuan (nearly 1 billion USD) in safeguarding intangible cultural heritage since the enactment of a law aimed at preserving traditions in 2011.Footnote22 Moreover, the country operates The National Administration of Cultural Heritage, an administrative agency under the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the People’s Republic of China.

The country boasts 55 national archaeological parks and 6,565 museums, with over 90 per cent of museums nationwide accessible to the public free of charge. Through strengthened measures concerning the protection and utilisation of revolutionary cultural relics, China has amassed more than 36,000 immovable relics and a collection of over 1 million sets of movable relics with revolutionary heritage.Footnote23 These initiatives aim to shift the priorities in cultural heritage preservation, which previously centred on specific objects, particularly in the realm of tourism, towards aligning with international expectations regarding cultural heritage.

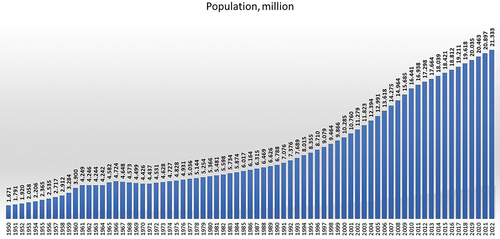

In addition, to preserve the traditional aesthetic and cultural characteristics inherent in the city it is essential to build special urban infrastructure facilities based on good urban planning. Good urban planning is also essential in the context of a significant increase in the population of Beijing, which has increased almost three times over the past 30 years and, as of 2022, amounted to 21.3 million people (). Traditionally, the growth of a city’s population contributes to the change of the urban landscape, which increases the burden on the remaining historical and cultural space. Consequently, it is necessary to respond appropriately to achieve the goals of sustainable urban development and environmental protection. The significant population growth in Beijing has significantly affected the ecological habitat of residents due to the rapid expansion of road transport and industrial development. It has led to an increase in carbon dioxide and other substances released into the atmosphere and the frequent formation of dense smog over the city.

Figure 5. Beijing, China metro area population 1950–2022.

Today the maintenance of the Forbidden City as an object of cultural heritage is in tension with the transformation of the historical environment. This generates a conflict between the Forbidden City as an object of cultural heritage and the process of transformation in the historic environment which may be explained as a state of perpetual struggle between the opposing goals of a developing society. On the one hand, society needs to preserve cultural heritage and the momentum of development by transforming the historic environment. This process cannot be stopped entirely. On the other hand, contradictions always arise between preservation and change, which are a natural result of social development. Examples are found in Seville, Spain; Lisbon, Portugal, and other cities around the globe.Footnote24

To manage these processes effectively within the framework of sustainable development at the Forbidden City, it is possible to use a model based on the synergy of a set of innovative digital tools, smart solutions in urban planning, a rational approach and cultural tourism ().

Figure 6. A model for managing the preservation of cultural heritage in a changing historic environment within the framework of sustainable development of the city.

Discussion

With the development and spread of modern digital technologies, the concept of heritage preservation acquires an entirely different meaning in the context of virtual restoration and reconstruction of historical space. The principal here is the entirely new monitoring and analysis capabilities provided by the digital technology of three-dimensional modelling. This technology can visually reconstruct the entire complex of historical and cultural material heritage based on preserved historical sources with the help of innovative digital algorithms leading to preservation through conservation and restoration.

Smart gentrification is the next necessary element of the model when managing a changing historic environment within a sustainable development framework. Gentrification is one of the ways to solve the problem of preserving and developing the historical urban environment. By creating comfortable living conditions, which usually include a system of measures aimed at attracting new residents and improving the territory’s image, generating areas of well-being, and improving infrastructure.

With the digital preservation of cultural heritage and smart gentrification, authorities can now pay particular attention to implementing the principles of sustainable urban environment development. The concept of sustainable urban development emanates from the notion of considering the structures within their confines, such as buildings, constructions, and other landmarks, as unique entities possessing significant social, cultural, tourist, historical, economic, and natural resources. In addition, talented and qualified residents with creative abilities and professional competencies live in urban areas. They are also permanent places of concentration of clusters for the development, research and production of innovations, training, creation, and exchange of knowledge, which contribute to the emergence of new ideas and scientific achievements and help their implementation and dissemination in society. At the same time, the urban historical and cultural environment is not an independent sphere of sustainable development due to the presence of many conflicts between the social, cultural, historical, economic, and environmental needs of the community. Therefore, the decisions taken in the field of sustainable development should make sense and motivate city residents. Secondly, they should make their lives more comfortable thanks to social and economic changes and guarantee an ecologically high-quality living environment. At the same time planning decisions should aim to preserve and rationally transform the existing historical and cultural space, without violating established traditions and or threatening historical memory. In most contemporary cities of Europe and China, established communities are pursuing the path towards building sustainable urban development.

The processes of urbanisation whether planned or spontaneous can be problematic when considering the problem of preserving the cultural heritage of a city and maintenance of the historical environment. In particular, gentrification significantly changes the appearance of cities including their historic environments through the formation of separate spaces and exclusive communities as they strive for innovation, creativity, sustainability and technological excellence.

On the other hand, gentrification contributes to the growth of the socio-spatial division, inequality, and instability in cities, which can negatively affect the preservation of a unique cultural asset or tourist attraction.

In general, the introduction of new geoinformation digital technologies can help solve the problems of effective management of the historical and cultural environment.Footnote25 The involvement of all groups of residents and communities of the city, as well as representatives of the business community and other stakeholders, in the processes of developing and justifying decision-making related to the preservation of historical and cultural heritage, are key elements in sustainable urban planning and management. The joint participation and cooperation of citizens, universities, and government agencies on the one hand and business on the other can facilitate the effective use of the intellectual resources of the human capital of a modern city to minimise the costs of public funds and achieve the desired synergetic effect from the involvement of investments, as well as other financial sources and tourist income.

After four decades of reform, China has become more prosperous and powerful than the previous centuries. Simultaneously, over the past few decades, Beijing has undergone a period of substantial construction activity, raising concerns about its potential impact on the preservation of the historical heritage of the Chinese capital. The Forbidden City stands out as the most extensive and impressive centre of Chinese imperial authority, constituting a part of the world heritage, which sharply contrasts with the ultra-modern architectural landscape of Beijing.Footnote26

Moreover, there are concerns that China prioritises huge tourism revenues today, including its World Heritage Sites, rather than preserving these objects from degradation. With such income differences demonstrated across the board, profit priority stands out as a clear pattern.Footnote27 Effective management of the preservation of cultural heritage largely depends on perceptions of the threat and subsequent attempts to stop or reverse the processes of loss and change.Footnote28

In the world, cultural heritage is recognised as having historical, social, and anthropological value. It is considered a factor contributing to sustainable development and is included in Sustainable Development Goals 11 and 8 of the United Nations. At the same time, Sustainable Development Goal 11.4 focuses on the protection and preservation of heritage, and SDG 8.9 on the promotion of sustainable tourism, which creates jobs and promotes local culture.Footnote29

The Sustainable Development Goals confirm the special value of ensuring the protection and preservation of the global cultural and natural heritage. In addition, today’s culture has already become the fourth most crucial dimension when considering sustainability issues after its parts’ environmental, social, and economic components. If we consider the world practice, where aspects related to cultural heritage are studied, then the most exciting example is shown in the city of Port Said in Egypt. At the same time, the relationship between tangible and intangible heritage for achieving sustainable urban development is considered in this case.Footnote30

Cultural heritage acquires value for tourism because maintaining and preserving tourist attractions motivate tourists to visit monuments, festivals, cultural events, archaeological sites, ruins, or architectural complexes. Thus, the representation of cultural heritage covers many issues and opportunities that usually make up most of what is proposed in this direction to preserve cultural heritage.Footnote31

Based on neoclassical ‘structural functionalism’, the authors took Beijing’s four urban historic and cultural districts as examples for typological analysis. As ‘structural heritage’, they can exclude urban and historically protected areas from the dilemma of ‘traditional’ and ‘modern’ and realise the living heritage of urban culture through endogenous development.Footnote32

In China, urban heritage management should raise public awareness and give residents more responsibility and authority to overcome existing problems in this area. Modern approaches to historical urban landscape planning may be helpful, which rely on well-established procedures for public participation in ensuring a balance of interests between heritage protections, socio-economic development, nature protection and improving the lives of citizens.Footnote33

Modern digital technologies play an important role in the management of cultural heritage. They help preserve cultural heritage and develop it based on virtual tours and virtual restoration technologies.

Digital image processing, 3D model restoration and various virtual restoration technologies, such as virtual modelling technology, can also provide customised solutions for multiple types of cultural heritage. Traditional restoration technologies cannot achieve them in data collection, image processing, auxiliary copying, image restoration, virtual display, and colour management.Footnote34

Conclusions

Cultural heritage is a valuable attribute of contemporary civilisation. Scientists consider this concept a set of all tangible and intangible assets inherited, received, and preserved from past generations, which people identify and value as an expression of their knowledge, memory, history, and traditions, as well as a heritage that strengthens a unique cultural identity. Effective management in this system should aim not only at preserving the cultural significance of the heritage that exists but also at its development and dissemination of information about it since, in the modern world, everything is subject to constant changes and transformations.

The study results show that today the Forbidden City is between two complex processes related to preserving and transforming the historical and cultural environment. There are also certain risks to the city’s cultural heritage and its environment, which come from natural and artificial changes associated with urbanisation and gentrification. First, it affects the territories and spaces near the Forbidden City which comprise its setting.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019, about 19.3 million people visited the Palace Museum in Beijing, compared with 17.5 million in the previous year. A unique historic environment has been formed here and transformed in recent decades due to urbanisation and gentrification. These processes create specific problems and open new opportunities for tourism development. In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of museums and collections of cultural relics in the urban historical environment of Beijing, which directly contributes to the growth of tourist activity. According to the regression analysis 2008–2019, there was a close direct correlation r = 0.95; P < .0001 between these phenomena, which positively influenced the city’s cultural development.

The innovative transition to the system of effective cultural heritage management in a changing historical environment requires using the model of sustainable development proposed in this study. This model should involve using innovative digitalisation tools, intelligent solutions in urban planning, a rational approach and cultural tourism. The practical implementation of the proposed ideas will allow the maintenance of a more reasonable population density and rationally placing industrial and economic facilities to preserve the traditional aesthetic and cultural characteristics inherent in the city. This study contributes to a broader provision of evidence and active advocacy for changes in urban planning regimes aimed at enhancing the sustainability of both contemporary Beijing and its historical environment, including the Forbidden City.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Lai, “The Emergence of ‘Cultural Heritage’ in Modern China.”

2. Li et al., “Informing or Consulting?”

3. Zhong, China, Cultural Heritage, and International Law.

4. Cheng, “A Study on the Social Performance of Cultural Heritages.”

5. He et al., “The Spatial Distribution and Influencing Factors.”

6. ”The Central Axis of Beijing (Including Beihai),” National Commission of the People’s Republic of China for UNESCO, UNESCO World Heritage Convention, accessed March 13, 2023, https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5802/

7. Zarrow, “Notes on Heritage and History in Modern China.”

8. Zhang et al., “Reflections on the Indoor Environmental Monitoring System.”

9. Qin et al., “Study on Deterioration of Historic Masonry.”

10. Song et al., “The Influence of Tourism Interpretation.”

11. Liu and Lan, “Museum as Multisensorial Site.”

12. Lasaponara et al., “Corona Satellite Pictures for Archaeological Studies.”

13. Graezer Bideau, “Resistance to Places of Collective Memories.”

14. Weihang and Jijiao, “‘Traditional to Modern’ Transformation.”

15. Tam, “The Revitalization of Zhizhu Temple.”

16. Yang, “Analysis on New Media Operation Strategy.”

17. Mateoc-Sîrb et al., “Sustainable Tourism Development in the Protected Areas of Maramureș, Romania.”

18. Dandan et al., “Current Status of Application of Virtual Restoration Technology.”

19. Mateoc-Sîrb et al., “Sustainable Tourism Development,” 1763.

20. Qin et al., “Study on Deterioration of Historic,” 585–91.

21. Fei et al., “Beijing 2016–2035.”

22. Xinhua, “China Invests Heavily in Protection.”

23. Xinhua, “China Achieves Significant Progress.”

24. Diaz-Parra and Jover, “Overtourism, Place Alienation and the Right to the City”; and Sequera and Nofre, “Touristification, Transnational Gentrification and Urban Change in Lisbon.”

25. Carmona, “Sustainable Urban Design”; Asefa, “Sustainable Urban Development Planning”; Sustainable Urban Planning Principles, “U.S.-China CEO Council for Sustainable Urbanization”; and Foster, “Circular economy strategies for adaptive reuse.”

26. Gao, “Symbolism in the Forbidden City.”

27. Blais, “UNESCO State of Conservation.”

28. DeSilvey and Harrison, “Anticipating Loss.”

29. Xiao et al., “Geoinformatics for the Conservation and Promotion.”

30. Abouelmagd et al., “Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Urban Development.”

31. Lohmann and Netto, Tourism Theory.

32. Weihang and Jijiao, “’Traditional to Modern’ Transformation,” 68–81.

33. Li et al., “Informing or Consulting?” 102268.

34. Dandan et al., “Current Status of Application,” 83–90.

35. ”Beijing Statistical Yearbook 2021,” Beijing Municipal Bureau of Statistics, accessed March 13, 2023, http://nj.tjj.beijing.gov.cn/nj/main/2021-tjnj/zk/indexeh.htm.

36. ”Number of Visitors to the Palace Museum in Beijing from 2012 to 2019,” Statista, accessed March 13, 2023, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1175986/yearly-visitors-to-the-palace-museum-in-beijing/.

37. ”Annual Report 2008,” The Forbidden City Publishing House, The Palace Museum, accessed March 13, 2023, https://en.dpm.org.cn/d/file/p/2015-03-27/0cda50ab42d2a6ac22826bc13c7fccdd.pdf.; “Annual Report 2009,” The Forbidden City Publishing House, The Palace Museum, accessed March 13,2023,https://en.dpm.org.cn/d/file/p/2015-03-27/17df650a4d401ffeb6f7abd4dd39118b.pdf.; “Annual Report 2010,” The Forbidden City Publishing House, The Palace Museum, accessed March 13, 2023, https://en.dpm.org.cn/d/file/p/2015-03-27/bbc19ea3d3bbdebba932affafc5af73e.pdf.; and “Annual Report 2011,” The Forbidden City Publishing House, The Palace Museum, accessed March 13, 2023, https://en.dpm.org.cn/d/file/p/2015-03-27/1a47cb007cab494fdeaaeed59f63cfa2.pdf.

38. ”Location,” The Palace Museum, accessed March 13, 2023, https://en.dpm.org.cn/.

39. The Palace Museum, “Location.”

40. ”Satellite Map,” Google Earth, accessed March 13, 2023, https://earth.google.com/web/search/Forbidden+City,+%e6%99%af%e5%b1%b1%e5%89%8d%e8%a1%97%e4%b8%9c%e5%9f%8e%e5%8c%ba+Beijing,+China/@39.91328245,116.39117109,46.14916507a,1841.71336852d,35y,-40.06299573h,59.98755056t,0r/data=CigiJgokCc3GUg0pCURAEZvHWvPW3ENAGdBzOyI1M11AIW1gNVF29FxA.

41. ”Beijing, China Metro Area Population 1950–2022,” Macrotrends, accessed March 13, 2023, https://www.macrotrends.net/cities/20464/beijing/population.

42. Dandan et al., “Current Status of Application,” 83–90.

43. Mateoc-Sîrb et al., “Sustainable Tourism Development,” 1763.

44. Qin et al., “Study on Deterioration of Historic,” 585–91.

45. Beijing Municipal Bureau of Statistics, “Beijing Statistical Yearbook 2021.”

Bibliography

- Abouelmagd, D., S. Elrawy, and M. Hardman. “Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Urban Development: The Case of Port Said City in Egypt.” Cogent Social Sciences 8, no. 1 (2022): 2088460. doi:10.1080/23311886.2022.2088460.

- Beijing Municipal Bureau of Statistics. “Beijing Statistical Yearbook 2021.” Accessed March 13, 2023. http://nj.tjj.beijing.gov.cn/nj/main/2021-tjnj/zk/indexeh.htm.

- Blais, C. “UNESCO State of Conservation: Chinese World Heritage Sites.” Wittenberg University East Asian Studies Journal 44 (2021): 1–23. Accessed March 13, 2023. https://wittprojects.net/ojs/index.php/wueasj/article/view/206.

- Carmona, M. “Sustainable urban design: principles to practice.” International Journal of Sustainable Development 12, no. 1 (2009): 48. doi:10.1504/ijsd.2009.027528.

- Cheng, Y. “A Study on the Social Performance of Cultural Heritage. Taking the Xi’an Daming Palace National Heritage Park as an Example.” In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Urban Planning and Regional Economy (UPRE 2022), 139–150. Dordrecht: Atlantis Press, 2022. doi:10.2991/aebmr.k.220502.027.

- Dandan, F., Y. Bo, and L. Qian. “Current Status of Application of Virtual Restoration Technology in Cultural Heritage Conservation.” The Frontiers of Society, Science and Technology 4, no. 4 (2022): 83–90.

- DeSilvey, C., and R. Harrison. “Anticipating Loss: Rethinking Endangerment in Heritage Futures.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 26, no. 1 (2020): 1–7. doi:10.1080/13527258.2019.1644530.

- Diaz-Parra, I., and J. Jover. “Overtourism, Place Alienation and the Right to the City: Insights from the Historic Centre of Seville, Spain.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism (2020): 1–18. doi:10.1080/09669582.2020.1717504.

- Fei, W., S. Xiaodong, Z. Hao, and W. Yimin. “Beijing 2016-2035: The Big Turn?” Les Cahiers 176 (2019): 48–53.

- Foster, G. “Circular Economy Strategies for Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage Buildings to Reduce Environmental Impacts.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 152 (2020): 104507. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104507.

- Gao, J. “Symbolism in the Forbidden City. The Magnificent Design, Distinct Colors, and Lucky Numbers of China’s Imperial Palace.” Education About Asia 21, no. 3 (2016): 9–17.

- Google Earth. “Satellite Map.” Accessed March 13, 2023. https://earth.google.com/web/search/Forbidden+City,+%e6%99%af%e5%b1%b1%e5%89%8d%e8%a1%97%e4%b8%9c%e5%9f%8e%e5%8c%ba+Beijing,+China/@39.91328245,116.39117109,46.14916507a,1841.71336852d,35y,-40.06299573h,59.98755056t,0r/data=CigiJgokCc3GUg0pCURAEZvHWvPW3ENAGdBzOyI1M11AIW1gNVF29FxA.

- Graezer Bideau, F. “Resistance to Places of Collective Memories: A Rapid Transformation Landscape in Beijing.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Urban Ethnography, edited by I. Pardo and G. Prato, 259–278. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-64289-5_15.

- He, D., Z. Chen, A. Shaowei, J. Zhou, L. Linlin, and T. Yang. “The Spatial Distribution and Influencing Factors of Urban Cultural and Entertainment Facilities in Beijing.” Sustainability 13, no. 21 (2021): 12252. doi:10.3390/su132112252.

- The Imperial Palace of Ming & Qing Dynasty. “State of Conservation of the World Heritage Properties in the Asia-Pacific Region.” Accessed March 13, 2023. https://www.google.ru/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjZ4uqisKX5AhX5pIkEHT5jCIQQFnoECAQQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwhc.unesco.org%2Fdocument%2F162536&usg=AOvVaw2WcITWCsdWG34Nes9xBqU2.

- Lai, G. “The Emergence of ‘Cultural Heritage’ in Modern China: A Historical and Legal Perspective.” In Reconsidering Cultural Heritage in East Asia, edited by A. Matsuda and L. E. Mengoni, 47–85. London: Ubiquity Press, 2016. doi:10.5334/baz.d.

- Lasaponara, R., R. Yang, F. Chen, L. Xin, and N. Masini. “Corona Satellite Pictures for Archaeological Studies: A Review and Application to the Lost Forbidden City of the Han–Wei Dynasties.” Surveys in Geophysics 39, no. 6 (2018): 1303–1322. doi:10.1007/s10712-018-9490-2.

- Li, J., K. Sukanya, A. P. Roders, and P. van Wesemael. “Informing or Consulting? Exploring Community Participation within Urban Heritage Management in China.” Habitat International 105 (2020): 102268. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2020.102268.

- Liu, P., and L. Lan. “Museum as Multisensorial Site: Story Co-Making and the Affective Interrelationship Between Museum Visitors, Heritage Space, and Digital Storytelling.” Museum Management & Curatorship 36, no. 4 (2021): 403–426. doi:10.1080/09647775.2021.1948905.

- Lohmann, G., and A. P. Netto. Tourism Theory. Concepts, Models and Systems. Boston, MA: Cabi, 2017.

- Macrotrends. “Beijing, China Metro Area Population 1950-2022.” Accessed March 13, 2023. https://www.macrotrends.net/cities/20464/beijing/population.

- Mateoc-Sîrb, N., S. Albu, C. Rujescu, R. Ciolac, E. Țigan, O. Brînzan, C. Mănescu, T. Mateoc, and I. Anda Milin. “Sustainable Tourism Development in the Protected Areas of Maramureș, Romania: Destinations with High Authenticity.” Sustainability 14, no. 3 (2022): 1763. doi:10.3390/su14031763.

- The Palace Museum. “Annual Report 2008.” The Forbidden City Publishing House. Accessed March 13, 2023. https://en.dpm.org.cn/d/file/p/2015-03-27/0cda50ab42d2a6ac22826bc13c7fccdd.pdf.

- The Palace Museum. “Annual Report 2009.” The Forbidden City Publishing House. Accessed March 13, 2023. https://en.dpm.org.cn/d/file/p/2015-03-27/17df650a4d401ffeb6f7abd4dd39118b.pdf.

- The Palace Museum. “Annual Report 2010.” The Forbidden City Publishing House. Accessed March 13, 2023. https://en.dpm.org.cn/d/file/p/2015-03-27/bbc19ea3d3bbdebba932affafc5af73e.pdf.

- The Palace Museum. “Annual Report 2011.” The Forbidden City Publishing House. Accessed March 13, 2023. https://en.dpm.org.cn/d/file/p/2015-03-27/1a47cb007cab494fdeaaeed59f63cfa2.pdf.

- The Palace Museum. “Location.” Accessed March 13, 2023. https://en.dpm.org.cn/.

- Qin, T., H. Yu, S. Dai, and P. Zhang. “Study on Deterioration of Historic Masonry in the Forbidden City in Beijing Aided by GIS.” The International Archives of Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing & Spatial Information Sciences 46 (2021): 585–591. doi:10.5194/isprs-archives-XLVI-M-1-2021-585-2021.

- Sequera, J., and J. Nofre. “Touristification, Transnational Gentrification and Urban Change in Lisbon: The Neighbourhood of Alfama.” Urban Studies 57, no. 15 (2020): 3169–3189. doi:10.1177/0042098019883734.

- Song, J., X. Rui, and Y. Zhang. “The Influence of Tourism Interpretation on the Involvement, Memory and Authenticity of Tourism Experience - Taking the Forbidden City as an Example.” In Proceedings of 8th ITSA Biennial Conference 2020, 567–585. London: The British Library, 2020.

- Statista. “Number of Visitors to the Palace Museum in Beijing from 2012 to 2019.” Accessed March 13, 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1175986/yearly-visitors-to-the-palace-museum-in-beijing/.

- Sustainable Urban Planning Principles. “U.S.-China CEO Council for Sustainable Urbanization. Paulson Institute (PI), in Partnership with the China Centre for International Economic Exchanges (CCIEE), China Centre for International Economic Exchanges.” 2017. Accessed July 10, 2023. https://www.paulsoninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Sustainable-Urban-Planning_EN_vF.pdf.

- Tam, L. “The Revitalization of Zhizhu Temple. Policies, Actors, Debates.” In Chinese Heritage in the Making: Experiences, Negotiations and Contestations, edited by C. Maags and M. Svensson, 245–268. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2018.

- UNESCO World Heritage Convention. “The Central Axis of Beijing (Including Beihai).” National Commission of the People’s Republic of China for UNESCO. Accessed March 13, 2023. https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5802/.

- Weihang, S., and Z. Jijiao. “‘Traditional to Modern’ Transformation of Beijing’s Urban and Historically Conserved Areas-Based on Neoclassical “Structural-Functionalism.” International Journal of Business Anthropology 12, no. 1 (2022): 68–81.

- Xiao, W., J. Mills, G. Guidi, P. Rodríguez-Gonzálvez, S. G. Barsanti, and D. González-Aguilera. “Geoinformatics for the Conservation and Promotion of Cultural Heritage in Support of the UN Sustainable Development Goals.” ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 142 (2018): 389–406. doi:10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2018.01.001.

- Xinhua. “China Invests Heavily in Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage.” Editor: huaxia, October 18, 2019. Accessed August 4, 2023. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-10/18/c_138482472.htm.

- Xinhua. “China Achieves Significant Progress in Cultural Relics Protection.” Editor: huaxia, July 30, 2023. Accessed August 4, 2023. https://english.news.cn/20230730/692fb74caefb4c06b90618aced43fd42/c.html.

- Yang, S. “Analysis on New Media Operation Strategy of Beijing Palace Museum.” In 2019 3rd International Conference on Economics, Management Engineering and Education Technology (ICEMEET 2019), 1598–1602. London: Francis Academic Press, 2019. 10.25236/icemeet.2019.325.

- Zarrow, P. “Notes on Heritage and History in Modern China.” Monumenta Serica 68, no. 2 (2020): 439–472. doi:10.1080/02549948.2020.1831252.

- Zhang, X., P. Dai, and Z. Zhao. “Reflections on the Indoor Environmental Monitoring System of the Heritage Buildings in the Palace Museum–A Case Study of the Meridian Gate Exhibition Hall.” The International Archives of Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing & Spatial Information Sciences 46 (2021): 951–955. doi:10.5194/isprs-archives-XLVI-M-1-2021-951-2021.

- Zhong, H. China, Cultural Heritage, and International Law. London: Routledge, 2018.

Appendix

Transformation of the historical environment of Beijing’s cultural heritage.