ABSTRACT

‘The Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People’s Republic of China’ was unveiled at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. in December 1974. It was the first exhibition of Chinese archaeological relics organised by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in the United States. This occasion marked a significant moment in Sino-American relations and cultural exchange during the Cold War. This paper explores the intricacies of the planning, organisation, and curation of the exhibition, highlighting the strategic use of cultural diplomacy by China to promote its state ideology on an international scale. This paper argues that the exhibition had far-reaching implications for US–China relationship at the time. On one hand, it represented a significant step towards cultural engagement and rapprochement between the two nations. On the other hand, it served to disrupt the relationship further by exposing ideological differences and triggering contentions. Thus, the exhibition’s impact on US–China relations was complex and multifaceted, reflecting the delicate act of cultural diplomacy in the context of Cold War politics.

1. Introduction

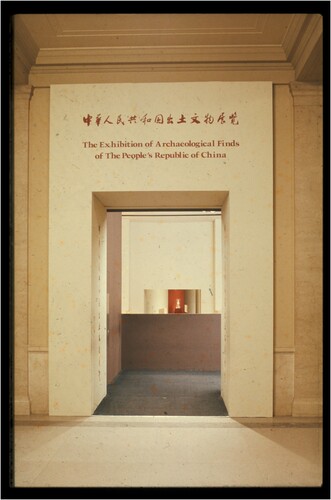

Against the backdrop of Cold War conflict, competition, and collaboration, ‘The Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People’s Republic of China’ was unveiled at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. in December 1974. The exhibition was then the largest exhibition ever held at the National Gallery of Art, occupying most of the exhibition chambers on its two floors ( and ).Footnote1 It showcased 385 archaeological objects, selected from thousands that were excavated at various sites across the country by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) government between 1949 and 1972. The exhibition consisted of a broad array of archaeological finds, including bronzes, ceramics, jade wares, fossil models, and textile works, ranging from the Palaeolithic period through the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). Prior to being presented in the United States, ‘The Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People’s Republic of China’ was held in several cities in Western Europe and Canada, including Paris, London, Vienna, Stockholm, and Toronto.Footnote2 To give a more concise and in-depth analysis, this paper narrows its focus to only the US segment of the travelling exhibition. The exhibition at the National Gallery of Art was the first leg of its year-long tour in America. The exhibition later travelled to the Nelson Gallery (now the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) in Kansas City, Missouri in April 1975, and lastly to the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, California in June 1975. The critical importance of the exhibition lies in the time and political milieu of its formation and realisation. The exhibition was the very first museum display of Chinese archaeological finds in the United States that was organised by the PRC government, marking a significant moment in US–China cultural exchange and rapprochement in the Cold War. Thus, ‘The Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People’s Republic of China’ holds tremendous cultural, diplomatic, and political implications, warranting serious scholarly attention, particularly when examined through the lenses of cultural diplomacy and politics.

Figure 1. Entrance to ‘The Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People's Republic of China’. Courtesy of National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Gallery Archives.

Figure 2. Installation view of ‘The Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People's Republic of China’. Courtesy of National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Gallery Archives.

Scholars have variously probed into some of the most significant activities of cultural diplomacy, such as international exhibitions, that took place during the Cold War period. In a seminal article entitled ‘Abstract Expressionism, Weapon of the Cold War’, Eva Cockcroft argues that Abstract Expressionist artists and their works were adopted and manipulated by the US government as a ‘propaganda weapon in demonstrating the virtues of “freedom of expression” in an “open and free society”’.Footnote3 ‘The New American Painting’, an exhibition prominently displaying abstract expressionist works, epitomised America’s cultural diplomacy as it travelled across eight European countries from 1958 to 1959. Frances Stonor Saunders discusses, in Who Paid the Piper, CIA’s efforts to infiltrate artistic movements with the aim of combating the political influence of the USSR and expand the US’s political influence in the international arena.Footnote4 In recent years, China’s cultural-diplomatic efforts have garnered increasing, though still limited, scholarly interest. In Museum Representations of Maoist China, Amy Jane Barnes delves into the 1976–1977 UK exhibition titled ‘Peasant Paintings from Hu County, Shensi Province, China’, highlighting Britain’s exposure to contemporary Chinese art and the nuanced Sino-British cultural diplomatic interactions amidst the final phases of the Cultural Revolution.Footnote5 While Barnes delves into the intricacies of Sino-British cultural diplomacy through art exhibitions, Pete Millwood, in Improbable Diplomats, highlights the diverse actors, from artists to scientists, who played instrumental roles in shaping US–China relations during the Cold War era. Millwood brings to light the pivotal yet previously underexplored role that a varied group of people – from athletes and artists to physicists and seismologists – had in reshaping US–China relations during the Cold War.Footnote6 Despite these recent publications, the majority of studies on Cold War cultural diplomacy to date predominantly centre on the West’s initiatives.

In light of the need for more scholarly focus on China’s cultural-diplomatic endeavours during the Cold War era, this paper aims to draw attention to the intricate choreography of US–China interaction that was involved in the planning, organisation, and curation of the 1974 exhibition. The significance of this exhibition lies in its role as the inaugural occasion where the PRC unveiled its cultural aspect to the United States. Furthermore, this paper scrutinises the specific strategies employed by Beijing to effectively utilise this exhibition as a vehicle for cultural diplomacy, enabling the dissemination of its state ideology on a transnational scale. This paper argues that the exhibition’s impact on US–China relations was complex and multifaceted, reflecting the delicate balancing act of cultural diplomacy in the context of Cold War politics. On the one hand, it represented a significant step towards cultural engagement and reconciliation between the two nations. On the other hand, it served to disrupt the relationship further by exposing ideological differences and triggering debates around the interpretation of Chinese history and culture. What was ostensibly an archaeological exhibition became a stage for diplomatic manoeuvring and geopolitical posturing, revealing tensions and contentions relating to historical interpretations, ideological divides, and curatorial approaches.

2. Prelude to the exhibition: deliberations, negotiations, and contentions

Marking a significant moment in US–China relationship, ‘The Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People’s Republic of China’ was the premiere display of Chinese archaeological finds in the United States during the Cold War. In a world divided, Sino-American relations were, in essence, hostile between 1949 and 1971. Refusing to acknowledge the legitimacy of the People’s Republic of China, Washington had been referring to the nation as ‘Red China’ during this period.Footnote7 China and the US also had military clashes in Korea and Vietnam, further highlighting the strained relationship between the two nations during this period. The end of the 1960s, however, brought a period of rapid transformations in international relations and politics. The relationship between China and the Soviet Union deteriorated sharply in the late 1960s, reaching a climax with a tense seven-month border conflict in 1969.Footnote8 This escalating tension between the two communist giants, otherwise known as the Sino-Soviet split, made it strategically beneficial for China to seek closer ties with the United States. Viewing the US as a potential counterbalance to the Soviet threat, China saw an opportunity for cooperation that could serve its geopolitical interests.Footnote9 The exchange of ping-pong players in 1971 marked the first official step in US–China rapprochement, a process that was further solidified by Richard Nixon’s momentous visit to Beijing in 1972. The 1974–1975 exhibition of Chinese archaeological finds in the United States, held less than two years after Nixon’s historic trip, not only played a pivotal role in the US–China rapprochement but also served as a powerful tool of cultural diplomacy. In particular, the exhibition’s exclusive journey to Western Europe, Canada and the United States – omitting countries within the Eastern Bloc – serves as a significant indication of China’s diplomatic reorientation at the time.

The idea of holding ‘The Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People’s Republic of China’ in the United States was formally conceptualised in February 1973. In a letter addressed to George H. W. Bush, who was the Head of U.S. Liaison Office in Beijing from 1974 to 1976, Yu Chan, the Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, recalled that ‘when Dr. Henry A. Kissinger … was on a visit to the People’s Republic of China in February 1973, he expressed to the Chinese Government the hope that the Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People’s Republic of China would be held in the United States’.Footnote10 In a manner mirroring its other travel destinations, the exhibition was presented as a comprehensive ‘package deal’, wherein the organisation, curation, object selection, and valuation were pre-determined by Beijing. The organising committee in Beijing was also in charge of drafting the exhibition catalogue. This arrangement was essentially non-negotiable, limiting opportunities for bilateral deliberations.

The ensuing correspondences between George H. W. Bush and Beijing’s representatives mainly revolved around the values of and the legal responsibility for the objects. In the confirmation letter, Yu Chan included a list of individual valuation of the exhibits. Together with auxiliary items such as copies, photographs, books, and models, Beijing’s organising committee valued the assemblage of 385 archaeological objects at CNY ¥98,703,350 (USD $51.3 million at the time, equal to approximately $300 million today).Footnote11 The valuation is of critical significance here, because Beijing asked that in the event of loss or damage of the objects during shipment or exhibition, ‘the United States Government shall indemnify the Chinese Government in accordance with the valuations of the objects as listed’.Footnote12 In his response to Beijing, Bush sought to untangle the legal responsibility of the United States, writing that ‘it is understood that in the event of partial loss or damage, indemnification shall be made in proportion to the loss or damage as such proportion may be agreed upon in friendly consultations between the two governments’.Footnote13 About two weeks later, Beijing replied to Bush’s inquiry, maintaining that: ‘if objects are lost, or suffer total loss through damage, the United States side shall compensate the Chinese side based on the valuations of the objects. No question exists of a need for the two sides to consult’.Footnote14 In face of this huge burden, the Director of the National Gallery of Art wrote to the Department of State, stating that the Gallery did not have the financial wherewithal to shoulder such liability.Footnote15 The fiscal liability also stirred up debates within official circles in the United States. While the financial liability was a hard pill to swallow, it was pointed out that the United States should not back out because of it: ‘it would not be to the advantage of the United States … for the Gallery to be unable to accept the exhibition because of its inability to protect itself against liability’.Footnote16 Indeed, if the US could not accept the financial burden and back out from this exhibition, it could not only put the nation in a bad light, but also potentially impact the power dynamics between the two nations in this early stage of Sino-American rapprochement. Eventually, the Department of State bore the whole responsibility of insuring these items, as well as making the decision that no claim would be made against the art institutions in case of any financial indemnification made to China.Footnote17 These to-and-fro negotiations and deliberations between Beijing and Washington divulge the power struggles and wider strategic concerns of the two nations which shrouded the planning, curation, and organisation of The Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People’s Republic of China. These negotiations and deliberations also reveal the delicacy of the diplomatic dance between the two countries, as a wrong step could potentially lead to a crisis in the early stage of Sino-American rapprochement.

Contention and power rivalry reached a climax as the exhibition approached its opening. Following its usual practice, the National Gallery had planned a press preview, but it was abruptly cancelled on that day by mutual agreement between the Gallery and the Department of State. The National Gallery issued a statement explaining that the press viewing was cancelled because the liaison office of the PRC insisted on assurances that certain foreign press representatives would not be admitted. The National Gallery was unable to give these assurances because to do so would have been contrary to its policy for such occasions.Footnote18 While National Gallery’s statement does not specify, archival documents reveal that China requested that journalists from Taiwan, South Korea, South Africa, and Israel be banned from taking part in the exhibition preview.Footnote19 This demand was seen as foreign interference and meddling in American press freedom, sparking criticism and controversies among officials and journalists in America. An article published in The New York Times commented that ‘this was the first time any foreign government had tried to restrict entry to a museum exhibition here. The Soviet Union has had several exhibits and the press previews were open to all’.Footnote20 While the press preview was hastily cancelled, the opening reception proceeded as scheduled. Notably in attendance were Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, First Lady Betty Ford, and a delegation from Beijing ().Footnote21 This choice was likely influenced by the desire to uphold the delicate equilibrium of the budding Sino-American relationship. Cancelling both the preview and the dinner could have been detrimental at this pivotal stage of Sino-American rapprochement. Nonetheless, this controversy over the press preview confirms that the political tension between the two nations remained a strong and persistent undercurrent in US–China rapprochement. It also shows that in this initial stage of diplomatic reconnection, something as seemingly innocuous as an exhibition preview could trigger conflict and cause controversy, and even be a site of political and diplomatic confrontation.

Figure 3. Paul Mellon, First Lady Betty Ford, and Chinese diplomat Liu Yang-Chiao (from left to right) at the opening reception for ‘The Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People's Republic of China’. Courtesy of National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Gallery Archives.

America’s request to extend the exhibition was the tailpiece to the exhibition-associated contention between the US and China. As the exhibition was originally planned to be held only in Washington, D.C. and Kansas City, its final stop in San Francisco was, in fact, added later. In a letter dated April 15, 1975, George H. W. Bush requested to hold the exhibition at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, while emphasising the need to maintain the previously arranged conditions and protocols.Footnote22 Despite writing the letter in a diplomatic manner, Bush, in his published diary, reveals his own reluctance to make the request, expressing concerns about undermining the US negotiating position and appearing too yielding to China.Footnote23 Bush’s hesitation presumably resulted from the exhibition preview controversy. Pete Millwood, in his book, highlights another tension point: following the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, Beijing’s Liaison Office approached the subsequent venue, the Nelson Gallery in Kansas City. They demanded the Gallery shutter its permanent Chinese collection, which included a notable Tang-dynasty Buddhist relief, during the exhibition. Given that many of the items had been brought out of China prior to the establishment of the People’s Republic, Beijing viewed them as tainted remnants of colonialism. Nonetheless, with backing from the State Department, the gallery declined this request. Its director, Laurence Sickman, remained firm, leading to Beijing’s Liaison Office eventually conceding and permitting the exhibition to proceed without closing the gallery’s permanent Chinese collection.Footnote24 The roles were now reversed, with Bush in the position of seeking Beijing’s approval for an exhibition extension. This epilogue to the exhibition-associated power rivalry and contention between the US and China highlights the careful and delicate choreography of US–China interaction in the planning, organisation, and curation of the Chinese archaeological exhibition.

3. Exploring China's cultural diplomacy: insights from the exhibition catalogue

Despite the exhibition concluding nearly half a century ago, the catalogue remains a pivotal resource. This section’s analysis focuses on the catalogue, as it offers a unique and detailed lens through which one can revisit and understand the nuances of the exhibition.Footnote25 The title page of the catalogue makes clear that the textual materials in the catalogue were provided by ‘The Organization Committee of The Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People’s Republic of China,’ which will henceforth be referred to as the committee in Beijing.Footnote26 The authorship of the catalogue is of critical significance, as the catalogue texts reveal how China considered and utilised the exhibition as an avenue to conduct cultural diplomacy and disseminate state ideology. As Judith Huggins Balfe points out, travelling exhibitions possess a unique ability to serve as effective ‘mediators of politics’ by intertwining cultural expression with broader political agendas.Footnote27 They become powerful platforms for shaping public opinion, promoting national identity, and advancing geopolitical interests. By showcasing artworks and artifacts, these exhibitions offer a curated narrative that reflects the values, ideologies, and aspirations of the hosting country or organisation. Instead of adopting a chronological, section-by-section approach to explore and analyse the exhibition, the second part of the paper carries out a systematic investigation into China’s cultural-diplomatic motivations and strategies that could be derived from the catalogue of ‘The Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People’s Republic of China’. Pervading the entire catalogue, Beijing’s cultural-diplomatic motivations and propagandic strategies could be summarised as (1) an emphasis on the long history of China to portray the PRC as the successor to and repository of ancient Chinese culture; and (2) a focus on the five-stage Marxist trajectory of historical development to imply that the Chinese society had been transformed into a socialist democracy. While these two issues are interconnected, for the sake of clarity, this paper intends to analyse them one at a time.

3.1. Emphasising the long history of China

‘The Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People’s Republic of China’ stands as a significant testament to the PRC’s shifting stance towards the country’s own history, particularly when viewed against the backdrop of the ongoing Cultural Revolution. The Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), initiated by Mao Zedong, is often remembered as an epoch of unparalleled social and cultural upheaval. This turbulent era witnessed systematic campaigns against traditional Chinese cultural symbols, values, and relics, as part of the drive to eradicate ‘The Four Olds’: old customs, old culture, old habits, and old ideas.Footnote28 The period was marked by a dismissal and even destruction of some historical artifacts, monuments, and texts that were perceived as vestiges of the ‘old society’. Yet, the travelling exhibition painted a starkly different picture, one that embraced China’s illustrious archaeological past. By foregrounding these artifacts, the exhibition not only showcased a deep-seated appreciation for China’s ancient history but also subtly contested the narrative of cultural vandalism associated with the Cultural Revolution. Such a move signalled China’s evolving approach to its historical narrative, suggesting a departure from the overt rejection of its pre-communist cultural heritage. Moreover, the exhibition indicated a broader reevaluation of the state’s relationship with Chinese history, pivoting away from the blanket condemnation of ‘The Four Olds’ to a more introspective recognition of its multifaceted past. This strategic presentation could be interpreted as an effort to find a equilibrium between acknowledging historical realities and crafting a refreshed national identity on the global stage that draws strength from its ancient roots.

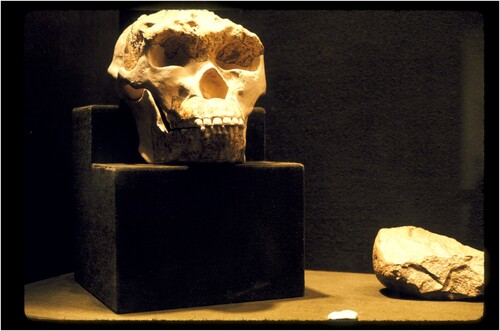

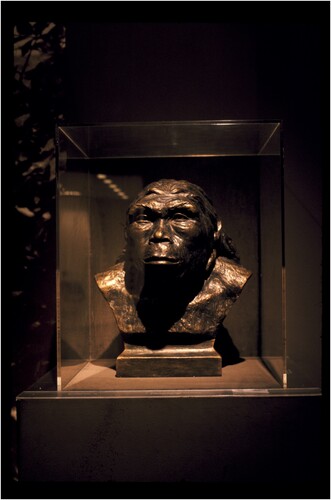

At the outset, the exhibition catalogue stresses the long history, heritage, and legacy of China. The first page of the exhibition proclaims that ‘from times immemorial, the forefathers of the Chinese people inhabited, labored and multiplied on her vast land’.Footnote29 The ‘immemorial times’ foregrounded the first section of the exhibition entitled ‘Excavations of the Sites of Lantian Man and Peking Man’, which showcased the skull models of the Lantian Man (Homo erectus lantianensis) and Peking Man (Homo erectus pekinensis), among other models and objects that were excavated in the archaeological site. By asserting that the Lantian Man and Peking Man were the ‘forefathers of the Chinese people’, the exhibition claimed a unilinear and continual linkage between these Palaeolithic hominins and people in China – here referring to the contemporary nation-state. One can see how this linkage seemingly extended the root of Chinese civilisation to a time as far back as 600,000 years ago, in addition to demonstrating a somewhat essentialist perspective that the peopling of China was a purely indigenous development. In his analysis of archaeological exhibitions in contemporary China, Gideon Shelach-Lavi observes that the distant past is presented with a powerful sense of connection and continuity between the past – no matter how distant – and the present.Footnote30 While Shelach-Lavi’s study focuses on present-day, domestic Chinese archaeological exhibitions, it is worth noting that a lineage between the distant past and the present was already discernible in ‘The Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People’s Republic of China’, the PRC’s first international exhibition which took place almost half a century ago.

The construction of a distant past served to create and demonstrate a national identity and memory in the exhibition. As Yannis Hamilakis points out, ‘the discourse on classical antiquity and national continuity from antiquity to the present’ could serve as a fundamental device in the construction of national memory.Footnote31 Presenting a distant past that has direct links to contemporary China as a continuous process in the exhibition can therefore be considered a way to construct and present a Chinese identity. It suggests that China uses archaeology to construct an unbroken lineage as part of its manipulation of cultural diplomatic idioms. In the exhibition, a distant national memory was largely formed via the Lantian Man and Peking Man. While the exhibition showcased only the skull models ( and ) of these ancient hominins and not the actual excavated artefacts, the catalogue suggests that ‘as a result of continued discoveries of human fossils and cultural relics since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, it is now possible to link up various important stages of the evolution of mankind’.Footnote32 This narrative not only connected the Palaeolithic hominins, in this case the Lantian Man and Peking Man, to a broader, more encompassing narrative of human evolution, but also echoes the narrative made by Hsia Nai, the Director of the Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, in an article published a year before the exhibition opened in the US. Hsia Nai argued that the discoveries of Lantian Man and Peking Man prove that ‘China is one of the cradles of mankind’.Footnote33 As Barry Sautman points out, official archaeological and paleoanthropological projects devised and carried out by the People’s Republic of China often sought to popularise claims that Peking Man and other fossilised hominins evidence the unequalled longevity and unity of the Chinese people.Footnote34 The narrative of a distant national memory played a critical role in the construction of nationalist myths that the nation utilised to carry out cultural diplomacy and propagate state ideology. Although the deployment of antiquity in the construction of national identity and national memory is far from unique, ‘The Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People’s Republic of China’ is distinctive in that it was the PRC’s first exhibition in the US, demonstrating how China endeavoured to construct a distant national memory and Chinese identity, and present them to the American audience in the exhibition.

Figure 4. Skull and lower jaw of the Lantian Man (model), cranium unearthed in 1964 at Kungwangling village; lower jaw unearthed in 1963 at Chenchiawo village. Courtesy of National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Gallery Archives.

Figure 5. Bust of the Peking Man (restoration). Courtesy of National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Gallery Archives.

An emphasis on the long history, heritage, and legacy of China befitted the propagation and dissemination of state ideology of China in the exhibition. Philip L. Kohl argues that ‘nationalism requires the elaboration of a real or invented remote past’.Footnote35 Likewise, the propagation and dissemination of a state ideology also requires an elaborate, remote past. The exhibition catalogue includes an ekphrastic judgment towards the outward characteristics of the skulls of the Lantian Man and Peking Man, stating that they exhibit ‘certain primitive physical features’.Footnote36 The description of the skulls as having ‘primitive physical features’ can be seen as a way to support the notion that the Palaeolithic age could be considered the starting point of primitive society, as posited in Marx’s five-stage trajectory of historical development. As Sigrid Schmalzer points out, the Peking Man played a central role in the narrative of human origins, aligning with the stages of history as described by Marx.Footnote37 The skull models of Lantian Man and Peking Man played an important role in forming a narrative of human origins and development from a state perspective, limning the ancient past as the starting point of China’s historical development, through which the nation metamorphosed from a primitive society to a slave society, and subsequently to a feudal society within the timeframe of the exhibition. As Aurora Roxas-Lim suggests, the timeframe of the exhibition represents ‘“the long struggle of the Chinese people” to achieve the society they know today’.Footnote38 An emphasis on the long history of China thus reflects Beijing’s desire to portray the nation as having liberated people in China from a protracted, repressive regime – one that began hundreds of thousands of years ago – and having brought them out from socio-economic, political, and cultural backwardness into the light of historical progress.

3.2. Through a Marxist lens

The exhibition catalogue highlighted the issues of class and social stratification in the history of China. In the object list and the catalogue, the 385 articles of archaeological finds were categorised in a linear and chronological order, beginning with 58 objects which were created ‘c.600,000–4,000 years ago’, a period described as ‘primitive society’ in the object list. The second group included 60 objects that were produced between c.2,100 and 475 BC, a period designated as ‘slavery society’. The third and largest group included the remaining 267 objects, made between c.475 BC and 1840 AD, a period labelled as ‘feudal society’.Footnote39 The act of grouping and labelling these historical periods as primitive, slavery, and feudal societies overshadows the common practice of categorising objects by their respective dynasties or eras of production. Exuding the state ideology of Maoist China, the labels echo the Marxist theory of historical materialism which outlines a five-stage development, from primitive-communal, through slavery, feudalism, capitalism, and eventually communism.

The exhibition characterised the Shang dynasty as the threshold through which China transformed from a primitive society to a slave society. The accentuation on the exploitation of the enslaved people in China and class struggle is clear in the catalogue’s discussion of archaeological finds from the period: ‘in slave society, the slave-owning class appropriated to itself not only all the means of production, but the person of the slave as well … The facts of history show that it was the slaves, who, with their wisdom and labor, developed production and created a splendid civilization’.Footnote40 While the Shang dynasty was highly stratified, ownership of productive means was not the only determining factor of social stratification. As Chao Lin points out, blood ties, military prowess, birth right, and clan relations were all decisive elements in shaping one’s social position in the Shang dynasty.Footnote41 In the exhibition catalogue, however, the social structure of Shang-dynasty China is presented as a rigid dichotomy between the enslaved class and the slave owning class, disregarding the nuances and other determining factors which affected the social order. The catalogue narration of the bronzes excavated at the Shang-dynasty site in Chengchow for instance, suggests that though the slaves created the Shang dynasty culture, yet the slave-owners exploited them as tools. In addition, the presumed owners of excavated objects from this era are uniformly referred to as slave-owners.Footnote42 This dichotomous perspective was perceivably adopted to frame the exhibition in accordance with the five-stage trajectory of historical development, presenting China as a mirror reflection and an exemplar of Marx’s paradigm.

With the end of the Spring and Autumn period and the beginning of the Warring States era, the catalogue shows how China transformed from a slave society to a feudal society. The catalogue provides a short account to explain this transition: ‘the years of the Warring States … gave the slave-owning aristocratic rule a heavy blow. The newly rising landlord class step by step seized political power and instituted social reforms’.Footnote43 Interestingly, the terms ‘slave’ and ‘slave-owner’ are entirely absent from descriptions of archaeological findings from the feudal period, as if slavery ceased with China’s transition to a feudal society. However, studies have shown that slavery persisted even during the Song and Yuan dynasties, the final two eras that the exhibition covered.Footnote44 In the descriptions of excavated objects belonging to the feudal stage, the term ‘laboring people’ replaced the term ‘slave’ to refer to the presumed makers of the excavated objects. Such a rapid and abrupt change in the catalogue’s discursive mode demonstrates the rigidity and dogmatism in the application of Marx’s five-stage paradigm. In China’s feudal stage, class struggle became a contradiction between the feudal ruling class and the labouring class. In the discussion of the archaeological finds from the Han-dynasty Tombs of Liu Sheng, including a burial suit of jade laced with threads of gold (), the catalogue suggests that ‘more than 2,800 objects were brought to light from the two tombs, which fully expose the extravagance and decadence of the feudal ruling class at the time and provide a great deal of important data for researches’.Footnote45 It is evident that in both the slave and feudal stages of historical development, there is a concomitant celebration of the people – the slaves, peasants, or labourers – as the true force behind China’s cultural and artistic developments, championing them as the makers of these magnificent objects in spite of the oppression.

Figure 6. Jade suit, sewn with gold thread; shroud for Tou Wan, wife of Prince Ching of Chungshan, unearthed from the tomb of Tou Wan. Courtesy of National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Gallery Archives.

The application of a Marxist temporal framework in historical representations sparked debates and disputes. In Out of China, Robert Bickers explores the exhibition’s segment in the UK and the ensuing debates over historical framing. As the UK and PRC both saw the exhibition as a diplomatic opportunity, tensions surfaced: China favoured a Marxist temporal perspective, while the UK opted for a chronological approach. Bickers infers that this was more than just a simple disagreement over historical interpretation; it hinted at broader geopolitical undercurrents. The PRC sought to cement its ideological narrative, while the UK’s methodology highlighted its concerns regarding China’s political ideology.Footnote46 The pronounced ideological overtones in the exhibition in both the US and Western Europe, instead of facilitating a mutual understanding, seemed to exacerbate ideological differences. The Marxist temporal framing, rather than serving its intended purpose of cultural diplomacy, only fuelled more contention. This reflects the PRC’s challenges, in its initial stage of Western-facing cultural diplomacy, in striking a balance between disseminating political ideology and maintaining subtlety in its approach.

While Marx’s paradigm of historical development was thoroughly adopted and applied throughout the entire catalogue, Marx and Engels’ concept of the Asiatic mode of production, which appears more pertinent to the Chinese context, was notably absent from the catalogue. The Asiatic mode of production suggests that ‘Asiatic societies were held in thrall by a despotic ruling clique, residing in central cities and directly expropriating surplus from largely autarkic and generally undifferentiated village communities’.Footnote47 While one cannot be sure why one Marxist notion was preferred over another, Joshua A. Fogel’s argument sheds light on the possible reason for the exhibition’s sole adoption of the five-stage model. Pointing out the potential perils for the contemporary Chinese state to adopt the Asiatic mode of production, Fogel suggests that ‘through a discussion of the Asiatic mode of production, for example, one can advance a thinly veiled criticism of the tremendous despotic power of the state or its ruler (for example, Mao)’.Footnote48 In contrast to adopting the notion of a progressive and dynamic society in the West, the idea of an unchanging and despotic society in the East would not achieve Beijing’s goal and desire to construct and display a positive portrayal of the People’s Republic. By embracing the five-stage paradigm rather than the Asiatic mode of production, China positions itself as the torchbearer of Marx’s core ideology of historical development which ends with communism. This decision is not merely academic or theoretical; it carries significant political weight and serves a dual purpose for China. Firstly, it strategically reinforces China’s position on the global communist stage in light of the Sino-Soviet split, emphasising its unique and unbroken commitment to Marxist principles. Secondly, in the setting of an international exhibition in the USA, it acts as a strategic tool for the dissemination of China’s ideology, offering a platform to influence and educate a global audience. In essence, this choice of historical model acts as both a defence and a proclamation of China’s Marxist ideology amidst geopolitical tensions.

Throughout the entire exhibition, there was a constant attempt to champion the role, involvement, and contribution of the PRC government in excavating, preserving, and collecting excavated objects, in addition to producing and disseminating archaeological knowledge. Such an endeavour can be derived from the framework of the exhibition, as it only showcased archaeological objects that were excavated between 1949 and 1972. Objects unearthed prior to the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 were, therefore, excluded. The state also has an apparent, larger-than-life presence throughout the entire catalogue.Footnote49 In addition to presenting excavated objects from China to the American audience, the exhibition was also an apparent celebration of the archaeological contributions of the People’s Republic of China. The emphasis on archaeological findings within the PRC can also be viewed as a strategic move to address and alleviate Western concerns and deep-seated perceptions of China stemming from the Cultural Revolution. These concerns were rooted in the perception that Maoist China was vehemently against historical reverence, with a keen focus on the destruction and vandalism of art and culture particularly in light of the ongoing Cultural Revolution.Footnote50 As Pete Millwood points out, by showcasing the state’s role in unearthing, preserving, and exhibiting archaeological finds, the PRC aimed to present a new image in the international arena, one that appreciated and valued its ancient history and artefacts, countering the prevailing narrative of cultural erasure.Footnote51 This not only demonstrated China’s respect for its past but also served as a tool for cultural diplomacy.

4. Conclusion

Perhaps the ideological overtone of ‘The Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People’s Republic of China’ was too distinctly obvious. The U.S. Information Agency, a governmental agency devoted to public diplomacy, published a report entitled The Use of Exhibits by the People’s Republic of China in July 1975 – less than a year after the opening of the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art. The report was skeptical about the motivation and intention behind China’s state-organised international exhibitions, suggesting that ‘while many of these shows have been propaganda ploys, the PRC has attempted to create a façade of altruism’.Footnote52 In its discussion of the 1974 exhibition, the report not only brings up the exhibition preview incident, but also critically interrogates the textual materials of the exhibition. Indeed, the US government would likely have been conscious of the diplomatic and propagandic potentials of international exhibitions, as governmental agencies in the US like the CIA already had a demonstrated history of instrumentalizing works of art as a means of cultural diplomacy and ideological propaganda.

Regardless of the report’s mistrust and suspicion towards the exhibition, it does mention that it was ‘the PRC’s greatest cultural coup’, implying that even the Information Agency recognised that the exhibition had made a splash and caught the attention of the American art world. The exhibition garnered significant attention from the American audiences. An archival photograph taken on March 29, 1975 – a day before the exhibition concluded in Washington DC – shows a long line of eager attendees waiting to view the exhibition (). The exhibition’s leg at the National Gallery of Art alone attracted over two-thirds of a million visitors – a Gallery record for a temporary exhibition at the time.Footnote53 In addition to this record-breaking attendance, there was also a significant number of visitors at both the Nelson Gallery in Kansas City and the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. The exhibition also paved the way for more exhibitions of Chinese archaeological artifacts in America. One notable exhibition that followed was ‘The Great Bronze Age of China’, which took place from 1980 to 1981 across five museum locations in America. Breaking away from the state-curated format, the responsibility of curating ‘The Great Bronze Age of China’ rested on Wen Fong, a Special Consultant at the Metropolitan Museum and a Chinese art history Professor. Wen Fong, in the exhibitions catalogue, focused on the intricate history of Chinese bronzes and minimised ideological undertones. This approach led to a noticeably diminished presence of the state and its ideology, diverging from the norm seen in ‘The Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People’s Republic of China’. This shift in representation can be perceived as a reflection of the changing political landscape in post-Mao China, especially during the transformative era under Deng Xiaoping’s de facto leadership. ‘The Great Bronze Age of China’ underscores the complex relationship between art and politics, illustrating how the direction and tone of an exhibition can respond to wider socio-political changes.

Figure 7. Photo taken on March 29, 1975 showing a long line of attendees waiting to view the exhibition before its conclusion at the National Gallery of Art. Courtesy of National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Gallery Archives.

In conclusion, ‘The Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People’s Republic of China’ marked a pivotal moment in Sino-American cultural exchange during the Cold War era. This paper has examined the intricate dynamics involved in the planning, organisation, and curation of the exhibition, shedding light on the strategies employed by the PRC to utilise it as a platform for cultural diplomacy and the dissemination of its state ideology on an international scale. By exploring the cultural-diplomatic incentives, political ideologies, and complex motivations that shaped the exhibition, this paper has demonstrated its profound implications for the relationship between the United States and China at the time. On one hand, the exhibition represented a significant stride towards cultural engagement and reconciliation between the two nations. On the other hand, it also exposed ideological differences and sparked debates, further straining the relationship. The impact of the exhibition on US–China relations was multifaceted and complex, reflecting the delicate nature of cultural diplomacy within the context of Cold War politics. It not only fostered moments of connection and understanding but also revealed the underlying tensions and divergent ideologies between the two countries.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to the journal’s editorial team and the two anonymous reviewers for their thorough review and suggestions. I greatly benefited from the insightful comments from Brooke Holmes and Nida Ghouse on the first draft of this paper. I am also thankful to Cheng-hua Wang, Andrew Watsky, Dora Ching, Cary Liu, Yixu Chen, Masha Slautina, Zhuolun Xie, and Raphael Lam for their valuable insights and feedback. A shortened version of this paper was presented at the University of Oxford International History of East Asia Seminar, and I would like to express my gratitude to the organisers and participants for their support and feedback. The publication of this paper in the open-access format was made possible with the support of the Princeton University Library Open Access Fund.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Shing-Kwan Chan

Shing-Kwan Chan is a Ph.D. student at Princeton University. His research focuses on Chinese art and material culture, specifically transregional cultural exchange and the intersection of art and science in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. His broader research interests include museum studies and issues related to race, gender and sexuality. He has presented his research at the University of Oxford, University of York, and Hong Kong Baptist University and published articles in Yishu: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art. Before joining Princeton, he worked as a Curatorial and Research Associate at the University Museum and Art Gallery, the University of Hong Kong, where he curated various on-site and virtual exhibitions.

Notes

1 National Gallery of Art, National Gallery of Art Annual Report 1975 (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1975), p. 14.

2 In his work Out of China, Robert Bickers discusses the complexities relating to the UK segment of the exhibition. For further reading, see: Robert Bickers, Out of China: How the Chinese Ended the Era of Western Domination (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2017), pp. 368–69. Additionally, Mary Jo M. Hague’s master’s thesis from 1987 analyzes the preparations and negotiations surrounding the exhibition in Toronto. This segment of the exhibition holds notable importance in the context of Chinese-Canadian diplomatic and cultural ties. See: Mary Jo M. Hague, Cultural Diplomacy: Canada-China a Case Study: The Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of The People’s Republic of China Held at the Royal Ontario Museum from 8 August - November 16, 1974 (The University of Alberta, 1987, master’s thesis). Notably, the exhibition’s segment in the US remains relatively less studied.

3 Eva Cockcroft, ‘Abstract Expressionism, Weapon of the Cold War’, in Pollock and After: The Critical Debate, ed. by Francis Frascina (New York: Harper & Row, 1985), p. 129.

4 Frances Stonor Saunders, Who Paid the Piper?: The CIA and the Cultural Cold War (London: Granta Books, 2000), pp. 18–50; 270–72.

5 Amy Jane Barnes delves deeply into the world of international traveling exhibitions, with a special emphasis on the 1974 archaeological exhibition. Chapter 5 of her work is particularly dedicated to this event, examining it within the framework of the UK's cultural and historical context. See: Amy Jane Barnes, Museum Representations of Maoist China: From Cultural Revolution to Commie Kitsch (London: Routledge, 2014), pp. 103–22.

6 Pete Millwood, Improbable Diplomats: How Ping-Pong Players, Musicians, and Scientists Remade US-China Relations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022).

7 Sino-American relationship during the Cold War has been studied by various scholars. The recently released edited volume Engaging China offers fresh and in-depth examinations of Sino-American relations spanning the past fifty years, shedding light on changing dynamics, achievements, challenges, and multi-faceted viewpoints, underscoring the heightened significance and intricacies of the relationship amid contemporary challenges. See: Anne F. Thurston (ed.), Engaging China: Fifty Years of Sino-American Relations (New York: Columbia University Press, 2021).

8 In The Sino-Soviet Split, Lorenz Lüthi examines the ideological disputes, primarily driven by Mao’s radicalization and the USSR’s pragmatism, that caused significant rifts in economic, party relations, and foreign policy, marking a defining Cold War event. See: Lorenz M. Lüthi, The Sino-Soviet Split: Cold War in the Communist World (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008).

9 In her book, Goh suggests that while the Nixon-era reconciliation with China in 1972 is often attributed to power dynamics among the USA, China, and the Soviet Union, a deeper understanding lies in the evolving American perceptions of China’s identity from the 1960s onwards, which paved the way for Nixon's landmark policy shift. See Evelyn Goh, Constructing the U.S. Rapprochement with China, 1961–1974 (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), p. 3.

10 U.S. Department of State, Exhibition of Archeological Finds: Agreement between the United States of America and the People's Republic of China (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1976), p. 2184.

11 The value of USD $51.3 million is derived from U.S. General Accounting Office, Decisions of the Comptroller General of the United States, Volume 54 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1976), p. 807. The equivalent value today is calculated with reference to the inflation rate between 1974 and 2022 in the US.

12 U.S. Department of State, Exhibition of Archeological Finds, p. 2185.

13 U.S. Department of State, Exhibition of Archeological Finds, p. 2254.

14 U.S. Department of State, Exhibition of Archeological Finds, p. 2256.

15 U.S. General Accounting Office, Decisions of the Comptroller General of the United States, Volume 54 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1976), pp. 807–08.

16 U.S. General Accounting Office, Decisions of the Comptroller General of the United States, Volume 54, 809.

17 U.S. General Accounting Office, Decisions of the Comptroller General of the United States, Volume 54, p. 809.

18 Bernard Gwertzman, ‘U.S Gallery Drops Preview Over Demand by China,’ The New York Times, December 11, 1974 <https://www.nytimes.com/1974/12/11/archives/us-gallery-drops-preview-over-demand-by-china-national-gallery.html> [accessed 29 April 2022].

19 U.S. Information Agency, The Use of Exhibits by the People’s Republic of China (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1975), p. 3.

20 Quoted from Gwertzman, ‘U.S Gallery Drops Preview Over Demand by China,’ The New York Times.

21 National Gallery of Art, National Gallery of Art Annual Report 1975, p. 14.

22 U.S. Department of State, Exhibition of Archeological Finds, pp. 2257–61.

23 George H. W. Bush, The China Diary of George H. W. Bush: The Making of a Global President, ed. by Jeffrey A. Engel (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008), pp. 199–200.

24 Millwood, Improbable Diplomats, pp. 213–14.

25 The focus of this paper is specifically on the catalogue of the exhibition. This choice was made to provide a thorough understanding of how the catalogue constructs a unique perspective on the exhibition and its objects via textual narratives. The archival images of the exhibition from the National Gallery of Art’s archives will serve as the foundation for future research, exploring the intricacies of spatial layout and the immersive visitor experience of the exhibition.

26 The Organization Committee of the Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People’s Republic of China, The Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People's Republic of China (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1974), p. 1. This reference will be henceforth abbreviated as TEAFPRC.

27 Judith Huggins Balfe, ‘Artworks as Symbols in International Politics,’ International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 1, no. 2, (1987): 195–96.

28 Timothy Cheek, Mao Zedong and China's Revolutions: A Brief History with Documents (New York: Palgrave, 2002), p. 228.

29 TEAFPRC, p. 7.

30 Gideon Shelach-Lavi, ‘Archaeology and politics in China: Historical paradigm and identity construction in museum exhibitions,’ China Information 22, no. 1 (Match 2019): 23.

31 Yannis Hamilakis, The Nation and its Ruins: Antiquity, Archaeology, and National Imagination in Greece (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), p. 236.

32 TEAFPRC, p. 7.

33 Hsia Nai, ‘Ancient Men in China,’ China Reconstructs (June 1973), p. 20.

34 Barry Sautman, ‘Peking Man and the Politics of Paleoanthropological Nationalism in China,’ The Journal of Asian Studies 60, no. 1 (February 2001): 98.

35 Philip L. Kohl, ‘Nationalism and Archaeology: On the Constructions of Nations and the Reconstructions of the Remote Past,’ Annual Review of Anthropology 27 (1998): 223.

36 TEAFPRC, p. 7.

37 Sigrid Schmalzer, The Peoples’ Peking Man: Popular Science and Human Identity in Twentieth-Century China (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 60–70. For another important discussion on the importance of the Peking Man in Modern China, see: Christopher George Janus and William Brashler, The Search for Peking Man (New York: Macmillan, 1975).

38 Aurora Roxas-Lim, ‘China’s Diplomacy through Art: A Discussion on Some of the Archaeological and Art Finds in the Peoples’ Republic of China,’ Asian Studies 11, no. 3 (December 1973): 57.

39 U.S. Department of State, Exhibition of Archeological Finds, pp. 2186–236.

40 TEAFPRC, p. 14.

41 Chao Lin, The Socio-political Systems of the Shang Dynasty (Taipei: Academia Sinica, 1982), p. 115.

42 TEAFPRC, pp. 17–20.

43 TEAFPRC, pp. 25–6.

44 Don J. Wyatt, ‘Slavery in Medieval China,’ in The Cambridge World History of Slavery, Volume 2, AD 500 – AD 1420, ed. Craig Perry, David Eltis, Stanley L. Engerman and David Richardson (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2021), pp. 276–84.

45 TEAFPRC, 31.

46 Bickers argues that such disagreements accentuated enduring debates about the rightful representation and interpretation of China’s expansive and detailed history, particularly on a global platform. Considering the political weight of China’s historical relics, the debate on representation, dominance, and interpretation is deeply interwoven with themes of national identity and international perception. See Bickers, Out of China, 368–69.

47 Quoted from Martin W. Lewis and Kären E. Wigen, The Myth of Continents: A Critique of Metageography (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1997), p. 94.

48 Joshua A. Fogel, ‘The Debates over the Asiatic Mode of Production in Soviet Russia, China, and Japan,’ The American Historical Review 93, no. 1 (February 1988): 79.

49 For instance, in the discussion of archaeological finds belonging to the Chinglienkang Culture, a Neolithic archaeological culture in East China, the catalogue points out that it was ‘one of the neolithic cultures of primitive society discovered after the founding of the People’s Republic of China’. See TEAFPRC, p. 11.

50 The conventional perspective on the Cultural Revolution regards it as a ‘national trauma’. This viewpoint is aptly captured in David E. Scharff’s observation: ‘the Cultural Revolution terrorised so much of the country, that it destroyed artefacts, traditions, and embedded ways of thought … could not fail to put a black mark on China’s hope for modernization’. See: David E. Scharff, ‘Preface,’ in Landscapes of the Chinese Soul: The Enduring Presence of the Cultural Revolution, ed. by Tomas Plänkers (London and New York: Routledge, 2010), p. xiii.

51 Millwood, Improbable Diplomats, p. 213.

52 U.S. Information Agency, The Use of Exhibits by the People's Republic of China, p. ii.

53 National Gallery of Art, National Gallery of Art Annual Report 1975, pp. 16–7.