ABSTRACT

This article explores the legacy act of Calcutta’s first progressive/folk Bengali rock band, Moheener Ghoraguli, founded in 1975 during a time of societal unrest. Emerging as a focal point of urban youth culture, their music, rooted in regional language, and drawing on the 1960s global rock phenomenon and Bengali folk music, fostered a sense of community among the urban Calcutta youth. Unpacking the legacy of Moheener Ghoraguli sheds light on cultural heritage, memory, and peak musical experiences in urban Bengal.

Introduction

Popular music scenes have proven to be vital sites for gaining insights into the socio-cultural and politico-economic perspectives of our contemporary history. In this article, I explore the cultural significance of the regional Bangla rock band, Moheener Ghoraguli, based in Calcutta (now Kolkata).Footnote1 The emergence and foundation of Moheener Ghoraguli in the 1970s amid Bengal’s urban middle-class youth marked a transformative juncture in the Bangla popular music scene, youth culture, and local identity. This discussion reads the 1970s music-based youth cultural phenomenon in Bengal through the lens of legacy acts and music scenes, within the larger framework of youth and popular music cultures. The initial segment of the discussion expounds on the rise of popular music studies, notably the prominence of rock music and its global sociocultural impact. This segment emphasizes the pivotal role of rock music in shaping youth culture, identity formation, and social interactions. Subsequently, the discourse narrows its focus to the central theme of the article—the legacy of Moheener Ghoraguli. By exploring the band’s emergence, origin, and foundation, the article offers insights into how Moheener Ghoraguli revolutionized the local music landscape in Calcutta. Their music resonated with urban youth, particularly students, reflecting their experiences amid political unrest, curtailed liberties, and limited media access. Drawing on journalistic coverage of the band, interviews with band members, and YouTube comments, I examine the legacy of Moheener Ghoraguli and its influence on countercultural movements, its impact on cultural memory, and its role in shaping a sense of belonging within the community.

Popular Music and Society

Understanding the role of popular culture as a social phenomenon, within both current and past settings, is crucial for constructing socio-cultural and politico-economic perspectives of our contemporary history (Shuker, Understanding 1). Key inquiries within the study of popular culture include understanding the creation, reception, and value of popular culture. These questions delve into the intricacies of cultural dynamics, hierarchies, and taste politics.

The dominant field of enquiry in media studies during the 1970s-1980s was around visual media texts. Works of Frith, Lipsitz, and Chambers, marked a point of departure to highlight the importance of popular music. Yet another paradigmatic shift occurred in the 1990s within the realm of popular music studies through key contributions by Andy Bennett, Sara Cohen, Will Straw, Keith Negus, and Deena Weinstein, which lay emphasis on rock and popular music’s pivotal role as a global cultural force (Shuker, Understanding 5). Popular music studies focus on certain key dimensions of its cultural meaning process: lived cultures, the social status of being part of those who consume the music (fans/audience), the embedded symbolic forms/texts, and the economic institutions and technological processes which create the texts (see works of Willis; Hebdige; Hall and Jefferson). Popular music culture, however, can never be holistically understood without a sociological exploration of its audience (Frith, “Music” 108).

In sociology, the relationship between youth and popular music serves as a dynamic lens to examine cultural trends, identity formation, and social interactions. The music choices of young individuals often reflect broader societal shifts, offering insights into values, community, identity, belongingness, and the ways in which music intertwines with the experiences of youth (see Hebdige; Frith; Bennett, “Subcultures”). The understanding of youth as a social context and category goes beyond defining youth according to a simple age bracket. As a social category, it embraces a wide variety of lifestyles, subcultures, and fandom. Youth audience segments are further nuanced and differentiated by class, ethnicity, age, and gender. These differentiations, and their significance to popular music, have historically been addressed by a now considerable literature on the sociology of youth. Contemporary scholarship on the link between popular music consumption examines themes like spectacular cultures/subcultures in relation to youth and popular music, the concept of musical “scenes,” and fandom as a social practice. Locality and youth culture are effectively brought together in the ethnographic work of Bennett (68). Significance of place and associated youth cultures thus was found to be crucial in the formation of popular music consumption patterns (Kong 185; Straw 370). In addition to ongoing discussions regarding the significant impact of popular music in socio-cultural processes of meaning-making, there have been academic discussions regarding the legitimacy of popular music as an influential and politically empowering factor among young people (Shuker, Popular; Cohen, “Ethnography” 129; Pratt 188).

Conceptualizations of youth culture in the 1950s assumed that all young individuals shared similar leisure interests and were similarly rebellious against their elders. This understanding evolved with the emergence of distinctive youth cultures linked to their growing autonomy of youth, class identity, and finally their choice of popular music expression and performances (see Hodkinson and Deicke). The 1960s saw the growth of a youth counterculture and this political stand was unsurprisingly reflected in the choice of popular music among youth groups (Grossberg). Emerging out of the socio-political zeitgeist of the 1950s in the U.S.A., rock music fused blues, R&B, country sounds, and more, as pioneers like Chuck Berry and Elvis Presley reshaped music. Britain’s Beatles and the Rolling Stones fueled the movement, leading to a global rock revolution. With its roots in America, rock swiftly spread worldwide, shaping the musical landscape, and was deeply linked with the growth of the global youth countercultural movements (see Frith, Sound Effects Bennett et al.). However, rock music cultures and the associated youth movements have been mostly studied and understood within a Global North and largely anglophonic setting. My aim, by focusing on the legacy of Moheener Ghoraguli, a regional Bangla rock band based out of Calcutta (now Kolkata), is to add aspects of the missing Global South discursive perspectives around youth-based popular music cultures.

Popular Musics in India and the Early Emergence of Rock

India has experienced three significant shifts in recent socio-economic history. Firstly, the transition from colonial rule to post-colonial independence in 1947; second, the 1991 economic reform, which introduced liberalization, privatization, and globalization, reshaping societal norms (see Chakravarty, “Popular Musics” 133); third, the ongoing digital revolution led by companies like Reliance Jio, making Internet access more affordable and widespread (Chakravarty, “Indian Electronic” 76). This article focuses on the period after independence but before liberalization, particularly the emergence of Moheener Ghoraguli in Bengal. To comprehend this, understanding the Indian music landscape of the time is crucial. In capturing the evolutionary timeline of India’s music industry until the late 20th century, Kasbekar (“Music” 16) mentions four primary phases:

An initial phase during the 1900s marked by fierce rivalry among predominantly foreign-owned music recording labels;

a span of nearly five decades characterized by the overwhelming control of the market by a single entity, HMV, along with the dominance of the Hindi film song genre;

the disruption of HMV’s dominance due to the grassroots “cassette revolution” that emerged in the late 1970s (see Manuel);

the subsequent impact of the satellite revolution in the 1990s fueled further changes in the landscape of the Indian music industry (see Juluri).

Without doubt, Hindi movie music, in its commercial and widely embraced manifestation as Bollywood music, has consistently maintained a dominant hold on widespread consumption, aligning with concepts of both the “cultural industry” and “cultural capital.” The linguistic diversityFootnote2 of the country makes it nearly impossible for the existence of a monolithic popular music scene (Manuel, “Cassette” 190).

The hegemony of Hindi film music pushed most of the independent music and western genres like jazz, rock, and dance music to the periphery. Introduced by the British Raj, jazz was present in India during most of the 20th century. In the 1920s-’30s, touring American jazz musicians performed in major cities like Bombay and Calcutta. Independent India had very few nightclubs in its early days. So live music performances were far and few between, limited only to major cities like Bombay and Calcutta (Sarrazin 70–71). As the 1950s rock-and-roll phenomenon began to gain popularity outside the US, spreading to different parts of the world, including India, it evolved. Even though rock had landed in the country, its reach lacked mass popularity and remained limited to the fringes (Sarrazin 138).

In its early days, following the British tradition, the Indian media referred to guitar bands as “beat groups” even after the music had transitioned to rock in the late 1960s. Musicians, on the other hand, swiftly adapted to the changes, referring to themselves as rock musicians, often applying the term retroactively and overlooking genre distinctions (Booth and Shope 226). Noteworthy beat groups from the 1960s were Beat-X from Madras, the Flintstones from Calcutta, and the Mystiks from Bombay (Sarrazin 140). Early beat groups and rock bands in the 1960s were mostly cover bands and even when they had original songs, the lyrics were in English. Their audiences consisted mostly of English-speaking urban Indians and Anglo-Indians (Shope 170).

While early attempts at formation of a rock scene in India can be traced to the early 1960s, it was not until the close of the decade that a handful of identifiable bands emerged. Since then, rock music in a diverse range of styles and forms has consistently been a part of India’s popular music landscape from the fringes. Rock’s position in the Indian music sphere and industry was shaped by three interlinked factors: (1) India’s postcolonial identity in relation to both British cultural influences and the dominant US music industry; (2) the economic and regulatory frameworks under India’s socialist government, and (3) the distinct characteristics of India’s cultural industries and the lack of a substantial market for standalone recorded music between 1950 and 1980 (Booth and Shope 230). Rock/beat music in India, like its Global North counterparts, was associated with nightlife: social dancing, nightclubs, drinking, etc. India’s postcolonial identity, however, shaped the response of its government and the larger mass response to what was registered as foreign and Western-style culture. The negative connotations pushed rock further into the periphery making it a niche cultural text viable to a specific cohort of the population: Indians with direct ties to colonial legacies through their biological/cultural backgrounds. Goan Christian, Parsi (ethnoreligious community of Iranian descent adhering to Zoroastrianism), Anglo-Indian, and other similar minority groups constituted the key members in the production of the early Indian rock scene.

Throughout the 1960s rock in the subcontinent had to compete with established western music scenes like jazz, which operated on an accepted and familiar cultural capital among the Indian elite. Additionally, foreign manufactured instruments were not commonly brought into the country during this period, and their prices were significantly inflated due to the Indian government’s taxation and foreign exchange policies. This added to the sustenance challenges of the early rock scene. Although playing covers was a widespread practice globally, the particulars of the Indian socio-political and economic conditions during this time made originals even rarer and less viable. This meant that the early rock scene was largely comprised of cover bands that performed songs in English. As a result, the scene was operated in a limited and niche capacity attracting only English-speaking and/or upper-class audiences (Booth and Shope 235). On a mass scale, the situated reality remained unchanged until the 1980s and 1990s with two pivotal shifts: the cassette revolution (see Manuel), which significantly reduced costs around music production and dissemination, and the economic liberalization that opened with the country’s economy for privatization leading to musical globalization (see Juluri). Prior to that, however, the scene remained on the fringes and relied on English-speaking audiences and English cover bands (Sarrazin 140).

By outlining this brief historical background of Western musical genres in the early days of post-colonial India, my objective has been to draw attention to the socio-culturally critical moment of the formation of Moheener Ghoraguli in 1975 in Calcutta, Bengal. By looking at the emergence, prevalence, and subsequent legacy act of a Bangla rock band from the 1970s, which followed the Western influence trajectory in the country and pre-dated globalization, the cultural significance of a regional rock band becomes even more apparent. Moheener Ghoraghuli’s music was laced with themes of social commentary, with lyrics written and sung in the local language: Bangla. Their legacy offers insights into the youth culture of that era in Calcutta, Bengal, which needs to be understood within the socio-political milieu in India and Bengal at the time of the formation of Moheener Ghoraguli.

Setting the Context: Youth, Political Violence, and Social Transitions in Bengal

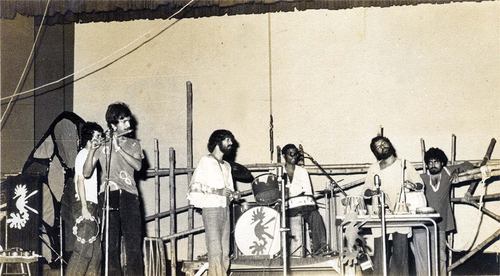

Formed in 1975, Moheener Ghoraguli, a Calcutta-based (see ) Bangla rock band, blended rock with BaulFootnote3 and regional folk. Their music conveyed anti-establishment sentiments, social critique, and subversive politics. The band comprised Gautam Chattopadhyay (Manik) as lead singer and lead guitarist; Pradip Chatterjee (Bula) as the bassist; Biswanath Bishu Chattopadhyay as the drummer; Abraham Mazumdar as the pianist; with Tapas Das, Ranjon Ghoshal, and Tapesh Bandopadhyay. Their music resonated with urban Calcutta’s youth, especially university students. This musical movement was inseparable from its socio-political context, shaped by prevailing social, political, and cultural dynamics, pivotal for the emergence of Moheener Ghoraguli.

In 1975, the year Moheener Ghoraguli came together, India has been independent for almost 30 years. The Indian National Congress (INC) constituted the Central GovernmentFootnote4 with then Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi (the first and, at the time of writing, only female Prime Minister of India). On 26 June 1975, Indira Gandhi declared a state of National Emergency/President Rule in the country on the national radio (All India Radio) (Singh 87). Imposition of the Emergency in India in 1975 marked a significant juncture in the country’s political landscape. Motivated by perceived threats to national security and faced with political opposition, Gandhi suspended civil liberties, curtailed media freedom, and imposed widespread censorship. The Emergency led to the arrest of political opponents and dissenters, fundamentally altering the democratic framework. Although Gandhi justified the Emergency as a means to restore stability, it sparked controversy and criticism, both domestically and internationally. The Emergency was lifted in 1977, underscoring the delicate balance between preserving political power and upholding democratic values in times of crisis (Paul 201–02). India was recovering from having faced five wars since independence along with insurgencies in the northeast, a severe famine, and now the coercive emergency state (Sarrazin 137).

Meanwhile, Bengal was grappling with significant political unrest intensified by the Naxalite movement. Spanning 1969–1971, the Naxalbari Movement emerged in the Darjeeling district’s Naxalbari village, West Bengal, India. It sought to address landlessness, exploitation, and social inequality, primarily targeting the marginalized rural populace. Prime Minister Gandhi banned the movement in 1969 due to its violent nature. The uprising resulted in clashes between the movement’s participants and the police, bifurcated into Naxal Intellectuals, and Naxalite on-ground violent actors (Chandra 25).

The initial intellectual drive was grounded on seeking justice for rural agrarian stakeholders against the status quo to shape an anti-establishment cultural landscape. Driven by young, male university students, the movement took an unfortunate shift toward utilizing violence as its primary communication tool (Sengupta and Maitra 293). By 1970, on-ground demonstrations shifted from intellectualism to protracted guerrilla warfare, affecting both rural and urban domains. The Bengal government responded with equal intensity, leading to indiscriminate violence on both sides. Calcutta neighborhoods were transformed into virtual war zones as Naxalites used crude bombs and guns against the police arsenal. Calcutta social intellectuals supported the ideology of the movement while being against the devastating violence and radicalization of the movement. During 1970–1971, Bengal was in an undeclared state of emergency, with curfews and university closures due to the Naxal uprising’s violence. Although the movement ended by 1972, it left a profound impact. Its message waned, and numerous students and police constables were killed, leaving scars on Bengal’s socio-political landscape, especially Calcutta (Sengupta and Maitra 295).Footnote5

For the average urban Calcutta youth their lived experiences were marked by prolonged state of emergency and quarantine-like conditions since the Naxal uprisings and subsequent Emergency (see Banerjee). In addition, the pre-liberalization economy of the time meant that the national media was State-controlled, State-owned, and State-run. Access to global media, and non-Hindi film music, was marked by significant challenges (Kasbekar 144). While the radio was the only viable platform for having access to global popular music, government-owned All India Radio would not play any non-film music (Kasbekar 132). Listeners had to tune into Radio Ceylon from Sri Lanka to hear rock and other forms of popular music from around the world (Sarrazin 138). Curtailed political, social, and economic liberties and an autocratic democracy prompted youth groups to employ popular music as a tool of expression to articulate and perform their identity, political stance, and community. Moheener Ghoraguli marked the beginning of the Bangla rock scene within this context.

Exploring the Legacy of Moheener Ghoraguli

(Source: “File: MoheenerGhoraguli-group.jpg,” photo by Aryasanyal at English Wikipedia; see, for permissions, Aryasanyal in Works Cited.Footnote6

My aim is to investigate how Moheener Ghoraguli’s (see ) youth-centric music culture resonated within local communities and how it imprinted its influence on the Bangla rock music scene and broader Bengali popular culture. By employing established concepts like peak music experiences (see Green, Peak), collective memory, and cultural heritage (see Cohen, “Musical Memory”), this discourse unpacks the band’s profound impact on sculpting cultural narratives and fostering a profound sense of belonging within their fan community. The focus here lies in shedding light on the band’s influence on countercultural movements situated in 1970s Calcutta, particularly their subversion of established cultural norms, as exemplified by their musical and lyrical style.

Moheener Ghoraguli: Emergence, Origin, and Foundation

1970s independent, pre-globalized India witnessed an emergence of urban middle-class educated youth in the major cities of the country (Dorin 199). It was not until the new economic policy was introduced in 1991, that the middle-class emergence became more prominent and spread from urban to the non-urban parts of the country (Chakravarty, “Indian Electronic” 75). By 1975, Calcutta, the capital city of West Bengal and former British India capital, had emerged as a hub for university students. The young individuals being discussed typically came from families that were already part of the middle class or were transitioning from their prior working-class identity to a middle-class identity. This section of the youth had two primarily common traits: their shared urban, educated identity, and the collective experience of living through challenging times of socio-political uncertainties as discussed in the previous sections. For the urban Bengali youth, music became a tool for self-expression and a site to enact their political identity. Even at a time when it was too early for the development of a widespread popular music scene, apart from the domain of film music, pioneers like Gautam Chattopadhyay, the founder of Moheener Ghoraguli, were involved in re-contextualizing and re-shaping the music scenes in cities like Calcutta (Dorin 205; Sarrazin 146).

In 1975, a group of seven middle-class young Bengali men from Calcutta came together to form a rock band. Inspired by Bengali poet Jibanananda Das’s “Ghora” (Horse) and a line in the poem that translates to “Moheen’s horses graze on the horizon, in the autumn moonlit wilderness,” they called themselves Moheener Ghoraguli (Moheen’s Horses) and used a seahorse as their band logo (see ), (“Mohin”). Moheener Ghoraguli sang in Bangla, the regional language of the state of Bengal and the city of Calcutta. Their music was inspired by the Beatles’ sound, Bob Dylan’s countercultural ethos, and Baul sangeet, a form of socio-political Bangla folk music. Combining these elements, they often labeled their music “Baul Jazz” with characteristics of progressive rock. Moheener Ghoraguli thus founded a unique rock music scene in Calcutta. Their music was a new form of localized political folk-rock, developed in response to the issues and concerns facing Bengal and India. At the same time, the songs were in Bangla and were about the quotidian life of a Bengali person with a latent leftist-Marxist social commentary (Sarrazin 140; Dorin 205; Chatterjee 70).

Figure 3. The logo for Moheener Ghoraguli: The Seahorse (see Mitra).Footnote7

Moheener Ghoraguli disbanded in 1981 after recording three albums: Shangbigno Pakhikul O Kolkata Bishayak (Anxious Feathers of Kolkata Birds), Ajaana Uronto Bostu ba Aw-Oo-Baw (UFO), Drishyomaan Moheener Ghoraguli (Apparent Moheener Ghoraguli). Songs like “Prithibita Naki Choto Hote Hote” (As Our World Shrinks), “Bhalobashi Jyotsnay” (What I Love about Autumn), and “Telephone” are their most popular songs. They did briefly reunite during the mid-1990s for a short while before the death of Gautam in 1999. The new albums were Aabaar Bochhor Kuri Pore (After 20 Years Again) in 1995, Jhora Somoyer Gaan (Songs of the Autumn and Fallen Leaves) in 1996, Maya (Delusion) in 1998, and Khyapar Gaan (Songs of the Mad Ones) in 1999. In 2015, the surviving members came together for their last album Moheen Ekhon O Bondhura (Moheen Now and Friends) with three new female members: Lagnajita Chakraborty, Malabika Brahma, Titas Bhramar Sen (Dhar; Moheener Ghoraguli).

The most important ways Moheener Ghoraguli contributed to local music-based youth cultures are as follows:

The induction of a new musical and lyrical style to the local milieu by combining 1960s rock and the traditional local folk music.

Curation of a new avenue of countercultural dissidence through musicking via Bangla rock music.

Reinstation on how the everyday can be both musical and political.

Laying the foundation for the late 1990s Bangla band cultural scene.

From the Horses’ Mouths: Localized Legacy Act and Countercultural Music Scenes

In keeping with their name Moheener Ghoraguli (Moheen’s Horses), the seven band members were affectionately called Ghora (horses). In time, their aging fan community dubbed the remaining living members “the old horses.” While discussing the naming of the band after the old Bengali poem, the band made several references to their alignment with the poet’s political stand against the Bengali bhodrolok (the bourgeoisie). Gautam, the band’s founder, lead singer, and lead guitarist, studied philosophy at the Presidency College in Calcutta and was known for his ties with the Naxalite Movement for which he served time in jail. In a radio interview with the local Bengali radio channel 92.8 Big FM posted on YouTube in 2017, the living members of the band discuss how their music was countercultural and posited to be against the Bengali bhodrolok (bourgeoisie) mainstream high culture (Sethi; “Mohin”).

At that time, the mainstream was multilayered. In a national context, music was dominated by Hindi film songs. At the state level of West Bengal, Bengali film songs and classical songs reflected the hegemonic ideologies that constituted upper-class Bengali bhodrolok (bourgeoisie) culture. Rigid performing and listening codes of conduct were enforced to maintain the facade of grandeur and purity of the music (Chatterjee 71; Sarrazin 141). When a group of university students came together clad in jeans and their guitars started making music inspired by rock, they faced societal rejection. Local newspapers published articles dubbing their act as “Bengali Pelvis Presly r nachon kudon” (The Obscene Performances of Bengali Pelvis Presley)—a play on Elvis Presley’s name and indicative of how Moheener Ghoraguli was inspired by rock with “pelvis” suggesting their obscene movements on stage. In the same interview, they mentioned how such press indicated they had achieved what they were aiming for: making the elite high-culture consuming segments of the society uncomfortable. In response to this and many other criticisms, the band designed their album art with cutouts of these newspaper clippings (“Mohin”).

Moheener Ghoraguli played a key role in reshaping the late 1970s youth music culture in Bengal by introducing a new musical and lyrical style. By fusing the 1960s rock style and local socio-political folk, Baul, their music gained relevancy among the urban educated youth of Calcutta. They achieved this fusion by combining instruments like the guitar, piano, and drums with flutes, and ektara (a one-stringed drone lute). Rock music scenes existed in the rest of the country in select pockets and were formed by bands singing in English and covering songs of Western artists catering to the Anglo-Indian community of the country. Moheener Ghoraguli’s music was in Bangla, the regional language of Bengal, which fostered a sense of community in their audience. Moheener Ghoraguli frequently performed live at music venues, in pubs, and in clubs in Park Street, Calcutta, thus making live music events part of the local currency. Performing songs such as “Prithibita Naki Choto Hote Hote” (Our World is Shrinking) and “Ajaana Uronto Bostu ba Aw-Oo-Baw” (UFO), their music was themed around political identity, social commentary, and belongingness.

In “Ajaana Uronto Bostu ba Aw-Oo-Baw” (UFO),Footnote9 they describe a group of young individuals who seem to have arrived in the locality from an extraterrestrial existence and had visibly stark alien features and understood the socio-cultural world differently. The song is a metaphor for feeling like an outsider within one’s own cultural community—concept that resonated with many young people who felt a loss of belongingness. Feeling like an outsider within their community was intertwined with the youth community’s political stand and identity. Another very popular song “Prithibita Naki Choto Hote Hote” (Our World is Shrinking), talks about how the modern society is being rendered to a state of being alone together. The song lyrics talk about the marvels of technology, like television and telephones, that are meant to bring us closer together. Late-modern capitalism, however, simultaneously works on keeping people so busy that despite access to modern technology they fail to keep in touch. The song concludes by saying that even the stars that are light years away from us seem, at times, closer to us than our close ones because one can see stars far more easily than their dear ones.

The band’s return for a brief period from the mid-1990s to 1999, before the death of Gautam, marked the second phase of their legacy. This was a very different time. Post 1991, the establishment of the new economic policy of India liberated and privatized the economy and introduced policies adhering to globalization. This was also when the early seeds of digital revolution in the county were being sown. Moheener Ghoraguli’s return acted as a catalyst for the formation of a new music scene in Bengal, centered in Calcutta. Emerging out of the socio-economic context of a now rapidly globalizing nation and new issues around identity, the Bangla band cultural scene owes its development to Moheener Ghoraguli.

In 2001, Calcutta was renamed Kolkata as a means of decolonizing its identity. At the juncture of this new phase, and with better access to global media and having grown up listening to Moheener Ghoraguli, a new crop of Bangla rock bands infiltrated the youth cultural milieu. University and college campuses in Calcutta, unlike other major campuses around the country, had a long history of hosting annual cultural festivals (Cashman 260). Live music became an inherent part of these college festivals. Live performances at local college campuses became the primary tool for sustenance for many of those in the Bangla band scene in Kolkata. From solo artists like Anjan Dutt (active as a musician in the late 1990s and filmmaker in his later years), to bands like Fossil, Cactus, Bhoomi (earth), and Krosswinds formed due to the foundation laid by Moheener Ghoraguli. The new bands and artists have been known to pay homage to Moheener Ghoraguli’s legacy. The new scene remained relatively popular in Calcutta until the early 2010s before the country massively turned toward EDM-based music festivals. In this way, even though Moheener Ghoraguli was founded in 1975 and captured the imagination of the youth at the time, their legacy remained relevant for the next generation of youth in the 1990s and 2000s via the perpetuation of the Bangla band music scene (Mukherjee 36).

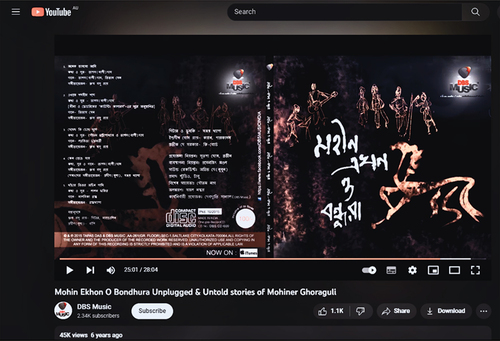

With over 45,000 views on the old interview posted on YouTube (see ), the cultural legacy of Moheener Ghoraguli becomes apparent. The cultural significance of the scene created around their musicking is further highlighted in the comment section of the YouTube interview. As seen in , user 1 writes (translated in English) how looking at the cultural scene formed around the music of Moheener Ghoraguli can prove to be a vital entry point for any research into the Bangla rock music culture of the time. User 2 notes how the band resisted the status quo and stood the test of time to become a crucial cornerstone in Bangla popular music. User 3 refers to the band as a legend, talking about their eternal legacy. User 4 mentions that the band evokes and represents true Bengali nostalgia. Users 5 and 6 talk about how Moheener Ghoraguli’s music can evoke the same emotions they felt when they heard the music for the first time, every time they listen to it and how their music informs the very idea of modern Bengali popular music. User 7 expresses their wish for the return of Moheener Ghoraguli’s music by quoting from one of their songs on how the fools never stop dreaming of an ideal world of music, community, and belongingness.

Figure 4. Screenshot of the Radio Interview with Moheener Ghoraguli posted on YouTube (see “Mohin”).Footnote8

Discussion: Moheener Ghoraguli’s Impact on Music, Identity, and Memory

Popular music scenes play a significant role in the social production of cultural heritage and collective memory. These scenes emerge as vibrant hubs where artists, audiences, and various cultural elements converge to create, celebrate, and perpetuate a distinct cultural identity (Cohen, “Musical Memory” 580). Reading into the legacy act of Moheener Ghoraguli provides an apt exploration of how popular music scenes contribute to the shaping of cultural heritage and collective memory.

In their various interviews with radio (see Moheener Ghoraguli), local news channel coverage (see “Popularity of Moheener Ghoraguli”), the band members have often mentioned how they were deeply invested in creating a sense of community through music, poetry, and political identity. Mainstream cultural hegemony coupled with the precarity of music-making back in the 1970s made it hard for the scene to be sustained and hence the band disbanded in 1981 (Dhar). Their legacy, however, was cemented in the collective Bengali cultural memory. This becomes evident in the way the Bangla band scene of the late 1990s was modeled around following the footsteps of Moheener Ghoraguli (Mukherjee 37). Since the 1990s, the Bengal government has also made state initiations of organizing music festivals in Calcutta in tribute to the contributions of Moheener Ghoraguli. In 2013, two years before their last album release with new members, the state organized a tributary live music concert called Aabar Bochhor Tirish Por (After 30 years). Audience and fan discourse around the legacy of Moheener Ghoraguli, as seen in , displays themes of affect, nostalgia, and collective forms of peak music experiences.

Peak music experiences are not only useful in understanding collective productions, but they also serve as a useful means of (re)construction and (re)shaping of cultural narratives. Green’s application of the “peak experience” concept demonstrates how the choice/taste of specific popular music styles, genres, and artists often stems from intense shared experiences (“‘I Always’” 335). In the case of the social production of the cultural scene around Moheener Ghoraguli in Bengal, the middle-class educated youth of the time had shared lived experiences of periods of significant societal, economic, and political changes. Since the members of the band and their music were deeply tied to these shared experiences, this resulted in a strong sense of belonging and collective memory among the fans and audience.

The insights offered by cultural memory studies aimed at interpreting present-day cultural environments can be linked to the “cultural turn” concept (see Stacey and Chaney). While urging for a greater focus on utilizing the cultural memory perspective to comprehend music scenes, Bennett and Rogers (48) elaborate on the importance of studying specific cultural contexts that emerge based on shared musical preferences. The concept of peak music experiences (as discussed by Green, Peak) fits seamlessly with this idea by centering on instances in music that stand out as profoundly influential, significant, and lasting for the participants. These occurrences are commonly discussed within the realm of popular music, surfacing in contexts such as journalism, biographies, and fan culture, where they are frequently recognized as pivotal in shaping individual’s relationships with music and their broader lives. Cultural memory has been conceptualized as a dynamic and diverse interaction between the modern media landscape and the individual’s locally influenced cultural sensitivities. Specifically, the concept of collective memory, as a framework for narratives, enhances our understanding of scenes as domains of collective engagement and membership. This is achieved by recognizing that individuals become part of and belong to a scene by embedding their life stories within its narrative framework and interpreting their experiences accordingly (Cohen, “Musical Memory” 582).

Closer examination of the comments made by the audience community and the individual anecdotes disclosed by the band members during the YouTube interview offers insight into how community-based music scenes contribute to the collective production of cultural heritage, memory, and nostalgia. An investigation into the legacy act of Moheener Ghoraguli also demonstrates the way in which the connection between localized music scenes, collective memory, and local identity takes form. By focusing on the events that led to the shaping of the Bangla rock music scene movement, the discussion presented here offers insight into the process through which musical memory is generated and linked to ideas of heritage, legacy, and memory. It is in this manner that the musical memory and legacy around Moheener Ghoraguli played a key role in shaping the identity of local Bengali youth.

As noted earlier in this article, and as observed by Chakravarty and Bennett (15), most existing scholarship on the relationship between youth cultures and popular music globally has largely overlooked the Global South. Consequently, the current understanding has mainly been shaped by a limited focus on youth cultures in the Global North. Rock music cultures, having emerged out of Global North contexts, have always been understood through the experiences of youth cultures formed around Global North settings. By presenting and exploring the cultural impact of the local Bangla rock band from the 1970s, this article offers an alternative history of localized rock music based on socio-cultural youth culture in Calcutta, a Global South cultural space. Notwithstanding how Global South experiences are varied, nuanced, and cannot be generalized, scholarly works illustrating individualized Global South experiences significantly contribute to the larger body of knowledge on histories of popular music and youth cultures. Such academic observations demonstrate significant changes in how meaning is constructed, identities are formed, and a sense of belonging is established within local youth cultures through their consumption of global popular music. Through the exploration of Moheener Ghoraguli’s legacy, this article elucidates how global popular music cultures are re-interpreted and re-contextualized through local youth cultural manifestations.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. I use both names of the city throughout the article depending on the timeline context being discussed. Since renaming the city to Kolkata, as a socio-political act of decolonizing the name of the city, happened in 2001, any reference made to the events taking place in the city prior to 2001 uses the older name Calcutta.

2. India’s state borders were drawn around linguistic groups: Hindi (422 million), Bengali (83 million), Telugu (75 million), Marathi (71 million), Tamil (60 million), Urdu (51 million), Gujarati (46 million), and Punjabi (29 million) are the main languages. Others use diverse local languages and dialects. About 1,500 such communication forms exist, highlighting strong regional identities. Even in major cities like Delhi, people mastering Hindi often have roots elsewhere, adding to a diverse multilingual population (Sarrazin 5).

3. The Baul community represents a group of mystic minstrels centered on music-making informed by mixed elements of Sufism, Vaishnavism, and Tantra. These wandering singers hail from both Bangladesh and the contiguous Indian states—West Bengal, Tripura, and Assam. The music of the Bauls, Baul Sangeet, is prevalent in the Bengali culture. It is a particular type of folk song, representing a long heritage of embedded mysticism, social commentary, socio-cultural collective identity, and so on. Bauls use several musical instruments: the most common is the ektara, a one-stringed drone lute or plucked-drum instrument.

4. Indian Government is federal in structure with unitary features, including the Central Government with the Prime Minister leading the executive and the President as the constitutional head. India consists of 28 states, each with a Chief Minister, and 8 Union territories administered by the President. The bicameral parliamentary system involves the Lok Sabha (Lower House) and Rajya Sabha (Upper House) (Government of India).

5. Insiders estimated the number of student deaths in the range of 3,700–7,100. Media reports were not reliable. The reported police deaths were in the 100s, with some reported missing at the time (see Banerjee).

6. All images used are either copyright-free or are in line with fair use: This image is licensed under CC BY 2.5, which has permission of re-use and re-share, provided the creator is given credit.

7. All images used are either copyright-free or are in line with fair use: The image of Moheener Ghoraguli logo is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0, which has permission of re-use and re-share, provided the creator is given credit.

8. The radio interview sourced from YouTube was originally posted in Bangla and has been translated by the author, who is native Bengali speaker, and whose first language is Bangla.

9. All the lyrics of music referred to originally in Bangla have been translated by the author, who is a native Bengali speaker, and her first language is Bangla.

Works Cited

- Aryasanyal. MoheenerGhoraguli-Group.jpg. English Wikipedia, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/?ref=openvers.

- Banerjee, Sumanta. India’s Simmering Revolution: The Naxalite Uprising. Zed Books, 1984.

- Bennett, Andy. Popular Music and Youth Culture Music, Identity and Place. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2000.

- Bennett, Andy. “Subcultures or Neo-Tribes? Rethinking the Relationship between Youth, Style and Musical Taste.” Sociology, vol. 33, no. 3, 1999, pp. 599–617. doi:10.1017/S0038038599000371.

- Bennett, Andy, and Ian Rogers. Popular Music Scenes and Cultural Memory. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2016. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-40204-2.

- Bennett, Tony, Simon Frith, and Larry Grossberg, John Shepherd, & Graeme Turner, editor. Rock and Popular Music Politics, Policies, Institutions. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2005.

- Booth, Gregory D., and Bradley Shope, editors. Popular Music in India: Studies in Indian Popular Music. Oxford UP, 2013. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199928835.001.0001.

- Cashman, David. “Indie-(an) Music: An Ethnography of a Rock Music Venue in Delhi.” Journal of World Popular Music, vol. 1, no. 2, 2015, pp. 256–76. doi:10.1558/jwpm.v1i2.21351.

- Chakravarty, Devpriya. “Indian Electronic Dance Music Festivals as Spaces of Play in Regional Settings: Understanding Situated and Digital Electronic Dance Music Performances.” Popular Music Scenes: Regional and Rural Perspectives, edited by Andy Bennett, David Cashman, Ben Green, Natalie Lewandowski, Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2023, pp. 67–82. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-08615-1.

- Chakravarty, Devpriya. “Popular Musics of India: An Ethnomusicological Review.” Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies, vol. 6, no. 3, 2019, pp. 111–22. doi:10.29333/ejecs/267.

- Chakravarty, Devpriya, and Andy Bennett. “Is There an Indian Way of Raving? Reading the Cultural Negotiations of Indian Youth in the Trans-Local EDM Scene”. Journal of Youth Studies, Feb. 2023, pp. 1–17. doi:10.1080/13676261.2023.2174008.

- Chandra, Amitabha. “The Naxalbari Movement.” The Indian Journal of Political Science, vol. 51, no. 1, 1990, pp. 22–45.

- Chatterjee, Nakshatra. “Return of the Alternative as the Popular: Nostalgia and the Music-Making of Moheener Ghoraguli.” Journal of Comparative Literature and Aesthetics, vol. 46, no. 3, 2023, pp. 68–77.

- Cohen, Sara. “Ethnography and Popular Music Studies.” Popular Music, vol. 12, no. 2, 1993, pp. 123–38. doi:10.1017/S0261143000005511.

- Cohen, Sara. “Musical Memory, Heritage and Local Identity: Remembering the Popular Music Past in a European Capital of Culture.” International Journal of Cultural Policy, vol. 19, no. 5, 2013, pp. 576–94. doi:10.1080/10286632.2012.676641.

- Dhar, Ashita. “Remembering Moheener Ghoraguli, India’s First Rock Band from Kolkata Whose Legacy Thrives in Resistance.” First Post, 20 Dec. 2020, https://www.firstpost.com/long-reads/remembering-moheener-ghoraguli-indias-first-rock-band-from-kolkata-whose-legacy-thrives-in-resistance-9117691.html.

- Dorin, Stephane. “Songs of Life in Calcutta: Protest and Social Commentary in Contemporary Bengali Popular Music.” Journal of Creative Communications, vol. 7, no. 3, 2012, pp. 197–208. doi:10.1177/0973258613512445.

- Frith, Simon. “Music and Identity.” Questions of Cultural Identity, edited by Stuart Hall and Paul Du Gay, SAGE Publications, 1996. doi:10.4135/9781446221907.n5.

- Frith, Simon. Performing Rites: On the Value of Popular Music. Harvard UP, 1996.

- Frith, Simon. Sound Effects: Youth, Leisure, and the Politics of Rock. Pantheon Books, 1983.

- Government of India. “Governance & Administration.” National Portal of India, 2023, https://www.india.gov.in/topics/governance-administration#:~:text=India%20is%20a%20Sovereign%20Socialist,constitutional%20head%20of%20the%20country.

- Green, Ben. “‘I Always Remember That Moment’: Peak Music Experiences as Epiphanies.” Sociology, vol. 50, no. 2, 2016, pp. 333–48. doi:10.1177/0038038514565835.

- Green, Ben. Peak Music Experiences: A New Perspective on Popular Music, Identity and Scenes. Routledge, 2022.

- Grossberg, Lawrence. “Rock And Youth.” We Gotta Get out of This Place: Popular Conservatism and Postmodern Culture. Routledge, 1992, pp. 171–200.

- Hall, Stuart, and Tony Jefferson, editors. Resistance through Rituals: Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain. Hutchinson and Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, 1976.

- Hebdige, Dick. Subculture the Meaning of Style. Routledge, 1979.

- Hodkinson, Paul, and Wolfgang Deicke, editors. Youth Cultures: Scenes, Subcultures and Tribes. Routledge, 2007.

- Juluri, Vamsee. Becoming a Global Audience: Longing and Belonging in Indian Music Television. Peter Lang, 2003.

- Kajanová, Yvetta. “Art Rock.” On the History of Rock Music. edited by Lea Duffell and Geoffrey Duffell, Peter Lang D, 2014, pp. 51–62. doi:10.3726/978-3-653-04793-6.

- Kajanová, Yvetta. “Hard Rock – the First Era 1960-1967.” On the History of Rock Music, edited by Lea Duffell and Geoffrey Duffell, D Peter Lang, 2014, pp. 29–43. doi:10.3726/978-3-653-04793-6.

- Kajanová, Yvetta. “Rock and Roll.” On the History of Rock Music, edited by Lea Duffell and Geoffrey Duffell, D Peter Lang, 2014, pp. 15–29. doi:10.3726/978-3-653-04793-6.

- Kasbekar, Asha. “Music.” Pop Culture India! Media, Arts, and Lifestyle, ABC-CLIO, 2006, pp. 16–37.

- Kasbekar, Asha. “Radio.” Pop Culture India! Media, Arts, and Lifestyle, ABC-CLIO, 2006, pp. 130–42.

- Kasbekar, Asha. “Television.” Pop Culture India! Media, Arts, and Lifestyle, ABC-CLIO, 2006, pp. 143–78.

- Kong, Lily. “Popular Music in Geographical Analyses.” Progress in Human Geography, vol. 19, no. 2, June 1995, pp. 183–98. doi:10.1177/030913259501900202.

- Manuel, Peter. Cassette Culture: Popular Music and Technology in North India. U of Chicago P, 1993.

- Manuel, Peter. “The Cassette Industry and Popular Music in North India.” Popular Music, vol. 10, no. 2, 1991, pp. 189–204. doi:10.1017/S0261143000004505.

- Mitra, Hiran. “Moheener Ghoraguli Logo since 1995.” English Wikipedia, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/?ref=openverse.

- “Mohin Ekhon O Bondhura Unplugged & Untold Stories of Moheener Ghoraguli.” Interview by 92.7 Big FM. YouTube,Uploaded by DBS Music, 15 Feb. 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AIvFrDZW1UE.

- Mukherjee, Kamalini. “Bangla Rock: Exploring the Counterculture and Dissidence in Post-Colonial Bengali Popular Music.” International Journal of Pedagogy, Innovation and New Technologies, vol. 4, no. 2, 2017, pp. 35–47. doi:10.5604/01.3001.0011.5843.

- Paul, Subin. “‘When India Was Indira’: Indian Express’s Coverage of the Emergency (1975–77).” Journalism History, vol. 42, no. 4, 2017, pp. 201–11. doi:10.1080/00947679.2017.12059157.

- “Popularity of Moheener Ghoraguli after 50 Years.” YouTube, uploaded by The Business Standard, 27 June 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DQu_RD2R7TA&t=56s.

- Pratt, Ray. Rhythm and Resistance: Explorations in the Political Use of Popular Music. Praeger, 1990.

- Sarrazin, Natalie. Focus: Popular Music in Contemporary India. 1st ed. Routledge, 2019.

- Sengupta, Samrat, and Saikat Maitra. “The Cultural Politics of ‘Spring Thunder’: The Naxalbari Movement and the Re-Framing of Bengali Culture in the 1960s.” International Quarterly for Asian Studies, vol. 52, no. 3, 2021, pp. 283–311. doi:10.11588/IQAS.2021.3-4.12784.

- Sethi, Divya. “In the 1970s, India’s First Rock Band Was Born In The Backyard of A Kolkata Home.” The Better India, 18 June 2021, https://www.thebetterindia.com/257125/moheener-ghoraguli-indias-first-rock-band-bengali-music-bollywood-commercial-songs-gautam-chattopadhya-gaurab-chatterjee-kolkata-music-history-div200/.

- Shope, Bradley. American Popular Music in Britain’s Raj. U of Rochester P, 2016.

- Shuker, Roy. Popular Music: The Key Concepts. 2nd ed. Routledge, 2005.

- Shuker, Roy. Understanding Popular Music. 2nd ed. Routledge, 2001.

- Singh, Preeti. “Graphic Delhi: Narrating the Indian Emergency, 1975–1977 in Vishwajyoti Ghosh’s Delhi Calm.” South Asian Review, vol. 39, no. 1–2, 2018, pp. 86–103. doi:10.1080/02759527.2018.1509536.

- Stacey, Judith, and David Chaney. “The Cultural Turn: Scene-Setting Essays on Contemporary Cultural History.” Contemporary Sociology, vol. 24, no. 6, 1994, pp. 730. doi:10.2307/2076659.

- Straw, Will. “Systems of Articulation, Logics of Change: Communities and Scenes in Popular Music.” Cultural Studies, vol. 5, no. 3, Oct. 1991, pp. 368–88. doi:10.1080/09502389100490311.

- Willis, Paul E. Profane Culture. Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1978.