ABSTRACT

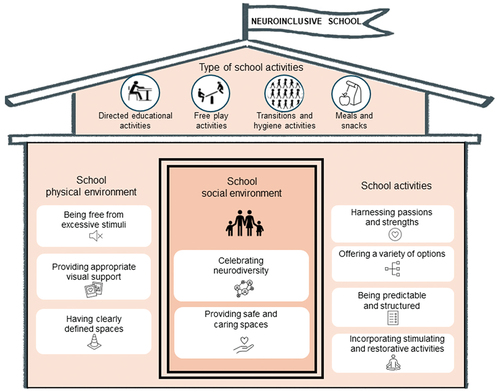

Inclusive education involves adapting schools upfront to the needs of students with diverse profiles to enable them to fulfill their potential and develop a sense of belonging to their schools. This study aimed to design a model that clarifies the features of school occupations and environments that support the participation and well-being of autistic students and their peers. A research-design approach was used to develop the model. Through the iterative and collaborative process, it came out as necessary for the model to target a larger diversity of students, especially those who are neurodivergent. The model includes nine desirable features of school environments and occupations that support the meaningful participation and the well-being of neurodivergent students. The importance for people in the social environment to celebrate neurodiversity, and to provide safe and caring spaces, came out as particularly critical. The model also provides indications relating to the physical environment (e.g. being free from excessive stimuli) and to the desired features of activities (e.g. harnessing passions and strengths, offering various options). It invites collaboration between stakeholders to create more welcoming schools for neurodivergent students and their peers.

Keypoints for Occupational Therapy

This neuroinclusive school model includes nine desired features of school environments and occupations that support meaningful participation and well-being of neurodivergent students.

The importance for the social environment to celebrate neurodiversity, and to provide safe and caring spaces, came out as critical.

This model is not a recipe, it is a starting point for occupational therapists collaborating with school teams to co-create more neuroinclusive schools

Introduction

Schools play a key role in children’s daily lives and the development of their full potential. However, many children encounter barriers that negatively affect their engagement and participation in schools, and their quality of life (Conseil supérieur de l’éducation, Citation2017). This is particularly true for autistic studentsFootnote1 who often describe their school experience as difficult, complex, and demanding (Horgan et al., Citation2023). Many autistic children are victims of bullying or harassment (Dillon & Underwood, Citation2012; Humphrey & Symes, Citation2010; Sreckovic et al., Citation2014) and then tend to develop a negative perception of themselves as being too different (Williams et al., Citation2019). Studies indicate that teachers and other school stakeholders are concerned with autistic students’ participation, not only in the classroom, but also in different contexts such as recess, lunch, or during transitions (Able et al., Citation2015; Corkum et al., Citation2014; Grandisson et al., Citation2020; Lindsay et al., Citation2014; Majoko, Citation2016; Saggers et al., Citation2019).

The mismatch between the strengths and needs of autistic students and the features of school occupations and environments contributes to this situation (Able et al., Citation2015; Grandisson et al., Citation2020). For example, studies indicate that the lack of structure and predictability in school activities is anxiety-provoking for some students (Able et al., Citation2015; Grandisson et al., Citation2020; Lindsay et al., Citation2013; Majoko, Citation2016). The fact that some school environment are often noisy and loaded with sensory stimuli, also affects the participation of many autistic students (Able et al., Citation2015; Barry et al., Citation2020; Finke et al., Citation2009; Grandisson et al., Citation2020; Kanakri et al., Citation2017; Lindsay et al., Citation2013; Majoko, Citation2016; Rotheram-Fuller et al., Citation2010). The lack of knowledge and understanding of autism among peers and school stakeholders can lead to negative attitudes toward these students (Able et al., Citation2015; Grandisson et al., Citation2020; Lindsay et al., Citation2013; Majoko, Citation2016). Several studies indicate that many teachers experience a low sense of self-efficacy as they do not feel sufficiently supported and prepared to meet the needs of autistic students in their classrooms (Anglim et al., Citation2018; Boujut et al., Citation2017; Chodiman-Soto et al., Citation2012; Finke et al., Citation2009; Gregor & Campbell, Citation2001; Lindsay et al., Citation2013; Majoko, Citation2016; McCullough, Citation2014; Symes & Humphrey, Citation2011).

Different practices are recognized as effective for intervening with autistic children (Institut national d’excellence en santé et en services sociaux, Citation2014; National Autism Center, Citation2015; Wong et al., Citation2015). However, these practices are often poorly adapted to the school context (Long et al., Citation2016). With their focus on developing students’ skills rather than reducing barriers, many of these practices are also inconsistent with inclusive education. Inclusive education instead calls for adapting schools upfront to the needs and strengths of diverse students so that all students can feel valued and respected in schools, develop their full potential, and feel a true sense of belonging (Conseil supérieur de l’éducation, Citation2017; UNESCO, Citation2020). The Canadian Academy of Health Sciences (Citation2022) recommends adopting an inclusive approach when attempting to meet the needs of autistic students, an approach focused on strengths, and on offering safe and predictable environments. However, it remains unclear what schools genuinely embracing the philosophy of inclusive education, while being adapted to the strengths of autistic students, looked like.

The team decided to use the Person-Environment-Occupation Model (Law et al., Citation1996) as it is recognized effective for analyzing interactions between the person, the occupation, and the environment (Strong et al., Citation1999). The main research question was: What are the key features of school environments and occupations conducive to meaningful occupational participation for autistic students and their peers? Occupational participation involves having access to, initiating, and maintaining meaningful occupations (Egan & Restall, Citation2022). In the school context, occupations refer to activities in which students engage, such as classroom learning, play, transitions, and meals. The research team values the subjective experience of autistic students. Thus, meaningful participation makes sense to them: it allows them to feel comfortable, confident, satisfied, and respected. It may mean students perform their occupations differently from what is expected, or that they choose not to participate in some school activities.

This paper reports on the key elements of the design of a conceptual model of an inclusive school, a school in which occupations and environments support meaningful participation for all students, including those who are autistic. It also shares key features of supportive school occupations and environments. This article is part of the Towards Inclusive Schools project, which proposes a collaborative approach for occupational therapists working in schools (Grandisson et al., Citation2020; Rajotte et al., Citation2022).

Material and Methods

The development of the model of an inclusive school was carried out following a design-based research approach which is a practical and iterative approach to design (McKenney & Reeves, Citation2013). This approach was chosen to develop a model based on the scientific literature but adapted for use in authentic contexts. It helped to structure the process of designing, evaluating, and adjusting the solution by building on partnership among researchers, practitioners, and stakeholders affected by the research (Anderson & Shattuck, Citation2012; Collins et al., Citation2004; McKenney & Reeves, Citation2013). The concrete problem identified here was that schools were not sufficiently adapted to the needs of autistic students. Ethical approval was obtained for the study (Comité intersectoriel de la recherche en réadaptation et en intégration sociale, CIUSSS-Capitale Nationale, #2017–561).

The collaborative and iterative design process was carried out according to the three phases proposed by McKenney and Reeves (Citation2013): 1) analysis and exploration; 2) design and construction; and 3) evaluation and reflection. It is expected in design-based research that more than one cycle including these phases will be used to improve the solution (McKenney & Reeves, Citation2013). Two cycles have been done so far in the current study. In both cycles, several co-construction meetings and consultations were held to select, analyze, and synthesize the features of environments and occupations. Guided by the desire to propose an accessible, simple and useful model, the design team made decisions regarding key features to be included in the inclusive school model using scientific, experiential and professional knowledge.

The first cycle of the study (2018–2021) was focused on developing a solution that would bridge the gap between scientific data in autism and the reality in the field for school practitioners. It included a literature review on effective practices in schools with autistic students, focus groups with school personnel (Grandisson et al., Citation2020), a pilot study in one school (Rajotte et al., Citation2022) and interviews with occupational therapists (Grandisson et al., Citation2024). Key elements from this cycle including the main actions carried out, the people involved, as well as the main findings and their effects on the model’s development, are presented in . It should be highlighted that the evaluation of the model at the end of cycle 1 enabled the team to confirm the potential contribution of such a model to the field and to identify directions for improving it. The most important modification came from the feedback received from occupational therapists and school team members that the inclusive school model proposed helped to facilitate the participation of a wide range of neurodivergent students (e.g. those who are autistic but also those with diverse attention, learning or language profiles) and that it would be more realistic to use the model if it explicitly targeted neurodivergent students.

Table 1. Design-based research process followed in cycle 1 and its effects on the model’s design.

The evaluation done at the end of cycle 1, along with calls for neurodiversity-affirming practice in occupational therapy (Dallman et al., Citation2022; Sterman et al., Citation2023), brought the team to start the second cycle (2022–2024). Neurodiversity-affirming practice emphasizes the importance of celebrating neurodiversity and valuing different ways of being and doing, making sure not to try to change behaviors only because they are different from the social norm, rather focusing on changing the environment or task to promote participation (Dallman et al., Citation2022; Sterman et al., Citation2023). While these publications were not available during the first cycle of the study, they appeared extremely congruent with the team’s perspective on the need to focus on changing the school, not the students. Cycle 2 therefore focused on: 1) attempting to reach more neurodiverse students, 2) including the perspectives of individuals with experiential knowledge of neurodivergence, and 3) embracing neurodiversity-affirming practices. This cycle included a literature review focused on the perspective of neurodivergent students and their families and interviews with three parents of neurodivergent students, two of whom also identified themselves as being neurodivergent. Its key elements are presented in .

Table 2. The design-based research process followed in cycle 2 and its effects on the model’s design.

Results

The iterative, collaborative process has resulted in a model of a neuroinclusive school that supports meaningful participation and well-being for neurodivergent students and their peers (). It was called a neuroinclusive school model, instead of an inclusive school model as initially planned, as this was the preference of the neurodivergent individuals consulted. It also appears more congruent with its development process and content. This model includes key features that support meaningful participation in the different types of school activities which concerned school personnel involved in the focus groups conducted (Grandisson et al., Citation2020). These are represented by four pictograms shown on the school roof: directed educational activities; free play activities; transitions and hygiene activities; and meals and snacks. From all the elements emerging from the literature reviews and the consultations, nine key desirable features of school environments and activities that support meaningful participation and well-being for neurodivergent students and their peers were selected by the design team. These were grouped into three categories: 1) social environment; 2) physical environment; and 3) school activities. The term activity was chosen instead of occupation to integrate feedback received from school representatives. Each of these features is described below, along with the empirical support for its relevance. These supports are mainly related to autism, since the first design cycle was initially aimed at meeting the needs of these students, and since the literature consulted during research on neurodiversity also focused on the autistic neurodivergence. However, the description of the features also includes examples of concrete strategies that have been identified as being more broadly germane to neurodivergent students. These strategies, illustrating how the feature can be applied in a school, are drawn from the literature as well as from the experiential, practical, and professional knowledge of all those involved in the design process, including neurodivergent individuals.

Figure 1. A neuroinclusive school model supporting meaningful participation and well-being for neurodivergent students and their peers.

Key Features of the School’s Social Environment

The social environment is at the center of the model to highlight its importance, as suggested by neurodivergent individuals. It is made up of all the people involved in the lives of neurodivergent students, including the principal, staff, other students, and families. Two key features of social environments that support the participation of neurodivergent students and their peers have emerged.

Celebrating Neurodiversity

The people in the social environment celebrate neurodiversity. This means that people in the school perceive the benefits of inclusion for all. People see each student as having unique strengths, regardless of their neurological profile. Neurodiversity is celebrated and embraced as a necessary variation rather than as a way of getting students to fit into a particular mold. It is seen as an asset that fosters creativity and problem-solving in collaborative work. To this end, the school offers neurodiversity awareness activities to help students better understand their strengths and needs and to foster greater acceptance of differences. Students are accompanied to recognize their own differences and to reflect on how each brings added value (Hodges et al., Citation2020). Reflective activities are integrated to help people become aware of and act on their cognitive biases. Principals provide leadership to promote an organizational culture that values neurodiversity among school staff, families, and the community (Lüddeckens et al., Citation2022). Professional development activities are organized to inform school staff about neuroinclusive approaches and to support the implementation of practices that meet diverse needs. Autism-awareness activities might also be done in the context of autism month (e.g. inviting people to wear blue clothes or inviting autistic leaders to give a talk).

Providing Safe and Caring Spaces

The school provides access to safe and caring spaces where neurodivergent students feel they can be themselves: they can socialize in ways that suit them, they can be confident to share their thoughts and ideas, and they can have respectful discussions to find solutions when facing challenges. The people in the social environment of the school provide a safe and caring space so that all students feel comfortable with the adults and children around them, without the constant fear of experiencing harassment (Canadian Academy of Health Sciences, Citation2022). Contexts in which students feel supported, comfortable, and safe contribute to students’ social participation and well-being at school (Hymers et al., Citation2019; Kasari et al., Citation2016; Kim et al., Citation2017; Koenig et al., Citation2014; Kretzmann et al., Citation2015; Saggers et al., Citation2019; Tanner et al., Citation2015). School staff develop trusting relationships with students and offer support in subtle ways to avoid stigmatization (Horgan et al., Citation2023; Lindsay et al., Citation2014; Stokes et al., Citation2017). The school curriculum includes activities to help all students develop their understanding of others so they can better interact together while valuing a broad range of ways to communicate and socialize (Crompton et al., Citation2023; Hodges et al., Citation2020; Koenig et al., Citation2014; Saggers et al., Citation2019; Sterman et al., Citation2023). For adolescents, self-help groups among neurodivergent students can be offered to interested students to enable students to receive emotional support, feel understood when facing challenges, and receive help in identifying solutions (Crompton et al., Citation2023). These groups can contribute to students’ self-esteem and to the development of a positive identity and, even if not all neurodivergent students will be interested in this type of group, offering such groups can be positive to show one’s commitment to inclusion (Crompton et al., Citation2023). Others suggest proposing special interest clubs to provide opportunities for interactions with like-minded people with common interests (Stokes et al., Citation2017).

Key Features of the School’s Physical Environment

The physical environment is made up of all the school’s facilities and physical spaces. Three key features of a school physical environment that supports the participation of neurodivergent students and their peers have emerged.

Being Free from Excessive Stimuli

The school’s physical environment is free from excessive visual, auditory, tactile, or olfactory sensory stimuli, to better match the students’ diverse sensory sensitivities. Reducing sensory stimuli helps to improve students’ well-being and focus their attention upon the task at hand (G. F. Clark et al., Citation2019; Kinnealey et al., Citation2012; Mostafa, Citation2008; Pfeiffer et al., Citation2017; Saggers et al., Citation2019; Watling & Spitzer, Citation2018). Classroom acoustics and noise reduction features include mats or sound barriers under doors (Kanakri et al., Citation2017; Kinnealey et al., Citation2012; C. S. Martin, Citation2016; N. Martin et al., Citation2019; Mostafa, Citation2014; Pfeiffer et al., Citation2017). The use of noise breaks or access to quiet spaces (also called withdrawal zones) inside or outside the classroom are also helpful strategies for many students (Carrington et al., Citation2020; McAllister & Sloan, Citation2016; Stokes et al., Citation2017). The visual environment is uncluttered, with natural lighting, neutral colors, few posters on the walls, and few objects on surfaces (Kinnealey et al., Citation2012; C. S. Martin, Citation2016; N. Martin et al., Citation2019; Mostafa, Citation2014; Pfeiffer et al., Citation2017). Unpredictable physical contact is reduced by encouraging one-way traffic in busy areas, allowing some students to be at the front or back of the group during transitions, or offering them the opportunity to exit before others.

Providing Appropriate Visual Support

The school environment offers suitable and sufficient visual support to illustrate instructions, explanations, or expectations for all students. Visual support makes it possible to reach the strengths of autistic students and thus helps support understanding and learning (Bolourian et al., Citation2021; Carrington et al., Citation2020; M. Clark et al., Citation2020; Hodges et al., Citation2020; Lindsay et al., Citation2014; C. S. Martin, Citation2016; National Autism Center, Citation2015; Oliver-Kerrigan et al., Citation2021; Stephenson et al., Citation2021; Sulek et al., Citation2019). The use of visual support helps to reduce the amount of verbal information and to concretize the instructions given to the class, which can be helpful for many students. Visual information can be useful for announcing a transition, clarifying the different steps in a task, imaging a choice of self-regulation strategies, indicating the direction of movement in the corridor, or identifying storage spaces. Involving neurodivergent students in the development of visual support can help make these supports more meaningful for them. Different media can be used, depending on the needs and preferences of the students, such as drawings, objects, photos, pictures, videos, symbols or written words.

Having Clearly Defined Spaces

The school environment offers clearly defined spaces in which expectations and functions related to different zones are clear, and large spaces are divided into smaller sections. The organization of space helps make the environment more predictable and serves to bolster the attention, understanding, learning, and autonomy of autistic students (C. S. Martin, Citation2016; Mostafa, Citation2008). In order to define the boundaries and functions of different spaces within the school, the classrooms, the schoolyard, and/or the lunchroom are segmented into different zones delineated using visual cues such as cabinets, floor markings, and plants, or by a difference in lightning or floor covering (McAllister & Sloan, Citation2016; Mostafa, Citation2018).

Key Features of School Activities

Four key features of school activities that support the participation of neurodivergent students and their peers in a neuroinclusive school emerged from the process. These features were established by considering all school activities, whether in the classroom, the schoolyard, the gymnasium, or the cafeteria.

Harnessing Passions and Strengths

Students’ passions and strengths are integrated into various school activities, such as classroom themes, teaching, games, or visual supports. The harnessing of passions and strengths fosters the participation of autistic students, notably by contributing to engagement in academic activities, initiative-taking, autonomy, positive interactions with peers, the development of self-esteem, and the construction of a positive identity (Bolourian et al., Citation2021; Carrington et al., Citation2020; Gunn & Delafield-Butt, Citation2016; Hodges et al., Citation2020; Koegel et al., Citation2012; Kryzak et al., Citation2013; Lindsay et al., Citation2014; Oliver-Kerrigan et al., Citation2021; Stokes et al., Citation2017; Watling & Spitzer, Citation2018; Wood, Citation2021). School staff will therefore take the time to get to know students’ passions and strengths in order to offer them multiple and varied opportunities to participate in activities that connect with these. Passions can be integrated into themes for class work, in the choice of responsibilities, or in the offer of extracurricular activities. Neurodivergent students can also be encouraged to help their peers in areas where they have strengths and be offered opportunities to share their passions with others.

Offering a Variety of Options

Activities offer a variety of options, enabling students to make choices about how to carry out activities according to their abilities, needs, and interests. Offering choices and using flexible tasks adapted to the needs of neurodivergent students can reduce frustration, improve autonomy, and facilitate new learning (Gunn & Delafield-Butt, Citation2016; Lindsay et al., Citation2014; Meindl et al., Citation2020; Reutebuch et al., Citation2015; Stokes et al., Citation2017; Watling & Spitzer, Citation2018). This is also in line with the recommendations to offer various means of engagement, representation, expression, and action in the universal design of learning, in order to reach a broader range of learners (CAST, Citation2018). Thus, it is possible to offer choices regarding the equipment or technological tools to be used for an activity, such as electronic tablets, interactive whiteboards, a cell phone, or a computer (Becker et al., Citation2016; Carrington et al., Citation2020; M. Clark et al., Citation2020; Grynszpan et al., Citation2014; Hodges et al., Citation2020; Hughes et al., Citation2019; Martin, Citation2016; Oliver-Kerrigan et al., Citation2021; Sansosti et al., Citation2015; Stokes et al., Citation2017). Flexibility can also be offered in terms of the assessments to be carried out (e.g., demonstrating their learning orally or in writing), deadlines, or the allotted time offered to complete an activity (Becker et al., Citation2016; Grynszpan et al., Citation2014; Hughes et al., Citation2019; C. S. Martin, Citation2016; Oliver-Kerrigan et al., Citation2021; Sansosti et al., Citation2015; Stokes et al., Citation2017). This flexibility can help provide the just-right challenge to all students, so that activities are not too easy, nor too difficult.

Being Predictable and Structured

School activities are predictable and structured, which means that clear, familiar routines and activities are in place, with stable milestones from one day to the next. This provides a reassuring context for students and helps improve their participation and well-being (Carrington et al., Citation2020; Hodges et al., Citation2020; Holcombe & Plunkett, Citation2016; Lindsay et al., Citation2014; Macdonald et al., Citation2018; National Autism Center, Citation2015; Pfeiffer et al., Citation2017; Stephenson et al., Citation2021; Stokes et al., Citation2017; Warren et al., Citation2021). To this end, timetables are used to clearly present the day’s structure and activities to students. Changes are announced in advance whenever possible to enable the students to prepare for them (Martin, Citation2016; Watkins et al., Citation2019). Complex tasks are broken down into smaller parts to make explicit the different steps involved, and expectations are presented with short, simple and concrete instructions (Carrington et al., Citation2020; M. Clark et al., Citation2020; Lindsay et al., Citation2014; Oliver-Kerrigan et al., Citation2021; Stokes et al., Citation2017).

Incorporating Stimulating and Restorative Activities

School activities include stimulating or restorative activities such as physical activities and rest periods to allow students to recharge their batteries and be more available for other activities. These activities can be incorporated at different times, depending on students’ needs, including within learning activities, at the beginning or end of the day, during recess, or at lunchtime. The provision of stimulating and restorative activities contributes to the well-being, task engagement, and academic learning of autistic students (Carrington et al., Citation2020; Ferreira et al., Citation2019; Hartley et al., Citation2019; Katz et al., Citation2020; Koenig et al., Citation2012; Lang et al., Citation2010; Nicholson et al., Citation2011; Oliver-Kerrigan et al., Citation2021; Oriel et al., Citation2011; Petrus et al., Citation2008; Sowa & Meulenbroek, Citation2012; Stokes et al., Citation2017; Tanner et al., Citation2015; Warren et al., Citation2021; Watling & Spitzer, Citation2018). Different activities can be offered, such as short sessions of intense physical activity in the classroom, mindfulness activities, stationary cycling, yoga postures, or by making favorite materials available. Flexibility is key to respecting each individual’s unique needs in terms of when, where, and how to self-regulate. For example, at recess, some students might benefit from the option of doing nothing or pursuing their interests alone to enable them to be more available for learning later on.

Discussion

This study led to the development of a neuroinclusive school model highlighting key features likely to support meaningful participation and well-being for neurodivergent students in various school activities. It was developed in collaboration with various people directly involved in the field of education and health, as well as with neurodivergent individuals and their family members. The iterative process of exploration, design, and evaluation led to the identification of nine desired features of school environments and activities. Two of these relate to the school’s social environment, which emerges as particularly critical in supporting neurodivergent students. Our findings suggest that people in the social environment should celebrate neurodiversity and provide safe and caring spaces. This is in line with the aims of an intervention developed by Hodges et al. (Citation2020), which also focuses on actions in the social environment to support the participation of autistic students. This intervention includes activities to improve awareness of differences and strengths, school connectedness, and interpersonal empathy. The importance of the social environment in the proposed model is also consistent with the double empathy theory concerning the lack of mutual understanding between so-called neurotypical and neurodivergent people (Milton, Citation2012). Those involved in the school should therefore try to better understand the perspectives of others, and value different ways of thinking, being or doing. Our results also show that it is important for the physical environment to be free from excessive stimuli, to provide appropriate visual support and clearly defined spaces. In addition, our results suggest that school activities should harness strengths and passions, offer diverse options, be predictable and structured, and include both stimulating and restorative activities. The proposed model ties in with several elements of the model proposed by Taylor et al. (Citation2021) concerning teachers’ practices with autistic students. For example, the latter also stressed the importance of consistency and clarity in routines, schedules, and guidelines, as well as an organized environment. Our model differs from the other models and interventions available by integrating the desired features of the social environment, but also of the physical environments and of occupations. It is also focused on meaningful participation and well-being across all school contexts.

The authors recognize, however, that there is no single solution that suits all school contexts and all students, given their varied needs and strengths. Thus, the features of activities and environments do not prescribe or impose a particular action, but rather support the analysis and choice of strategies consistent with the unique needs of school teams, students, and families. This flexibility is conducive to transformations in school practices, as it enables adaptation to each environment for greater consistency with its culture, needs, and practices (Desimone, Citation2009). The authors also recognize that it is not realistic, or even desirable, to implement changes in all features simultaneously. The proposed model has been developed to facilitate the work of occupational therapists supporting school teams. It is a component of a more comprehensive intervention that also includes an analysis of the school-team’s priorities, as well as team and individual coaching in different school contexts (Grandisson et al., Citation2020; Rajotte et al., Citation2022). A tiered response approach (VanderKaay et al., Citation2021) is recommended, which involves focusing first on changes that can be made for all students, then implementing personalized strategies as needed for one or more students by involving them in finding adaptations that make sense for them. The proposed model contrasts with findings from a recent systematic review of school-based occupational therapy, which highlights the effectiveness of interventions to improve school skills and abilities among autistic children or those with attention deficits (Watroba et al., Citation2023). The focus we propose is the opposite: we argue that occupational therapists should focus on changing the school so that neurodivergent students can participate in ways that are meaningful to them and that promote their well-being. It is hoped that the proposed model will help occupational therapists embrace neurodiversity-affirming practices in schools. As Dallman et al. (Citation2022) argue, occupational therapists and other professionals should celebrate neurodiversity, not try to change neurodivergent individuals’ ways of being. In schools, this paradigm change is essential to support neurodivergent students’ and neurodivergent employees’ well-being.

Although presented as a neuroinclusive school model, the iterative design process was developed by drawing more explicitly on the literature and experiential knowledge related to the autistic neurodivergence. The model, therefore, does not claim to include all the features of environments and activities to meet the specific needs of all neurodivergent students, such as those with specific learning challenges. Our goal was to identify key features that could be helpful for many students. Design-based research may require several cycles to arrive to a solution that satisfies everyone (McKenney & Reeves, Citation2013). The model designed has only been evaluated once in a pilot study in an authentic context (Rajotte et al., Citation2022), and from the perspectives of occupational therapists working in schools (Grandisson et al., Citation2024). Our team is preparing for further experimentation in authentic contexts during the 2024–2025 school year. Transformations to school environments and occupations, as a result of the support provided by the occupational therapist, will be documented. Furthermore, although neurodivergent individuals and parents were consulted in the preparation of the neuroinclusive school model, the authors acknowledge that, ideally, they would have been involved more in the whole process from the very beginning. While all authors of this paper believe in neuroaffirmative practices, only one identifies as neurodivergent (NT), as she is autistic and has high cognitive functioning, epilepsy and, variable attention stimuli trait (also known as attention deficit disorder in medical jargon). She has worked with many neurodivergent students and employees through her extensive experience as a teacher, principal, and educational consultant. One of her roles was to ensure that data analysis was not tainted by the double empathy problem or stereotype threats. In addition, three of our team members are parents of neurodivergent children with varying neurotypes. Suggestions for improvements to the model will be welcomed, especially from neurodivergent people. The model was designed for use by occupational therapists wishing to enhance a school team’s ability to promote the participation of neurodivergent students. However, the design and evaluation process led the team to realize that the model could also be used in collaboration with other professionals.

Conclusion

This article is first and foremost a call for a change of perspective in working to support school participation of neurodivergent students. It suggests focusing more on the modifications that can be made to the school and less on the development of students’ abilities. It invites collaboration between different stakeholders to create more welcoming schools. This model is by no means a recipe to be rigidly applied, but rather a proposed tool on which to draw when working together. It is a starting point, not an end in itself. It is a call to marshal the various players in the school environment to create institutions that support meaningful participation for a wider range of students.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the individuals who provided feedback on different versions of this model.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Identity-first language is used in this article to refer to autistic students. Identity-related terms are generally preferred by autistic people and seen as a way to avoid ableist language (Bottema-Beutel et al., Citation2020; Fecteau et al., Citation2024). This choice is congruent with the authors’ perspective that neurodiversity should be celebrated, not medicalized.

References

- Able, H., Sreckovic, M. A., Schultz, T. R., Garwood, J. D., & Sherman, J. (2015). Views from the trenches: Teacher and student supports needed for full inclusion of students with ASD. Teacher Education and Special Education, 38(1), 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406414558096

- Anderson, T., & Shattuck, J. (2012). Design-based research: A decade of progress in education research? Educational Researcher, 41(1), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X11428813

- Anglim, J., Prendeville, P., & Kinsella, W. (2018). The self-efficacy of primary teachers in supporting the inclusion of children with autism spectrum disorder. Educational Psychology in Practice, 34(1), 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2017.1391750

- Barry, L., Holloway, J., & McMahon, J. (2020). A scoping review of the barriers and facilitators to the implementation of interventions in autism education. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 78, 78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2020.101617

- Becker, E. A., Watry-Christian, M., Simmons, A., & Van Eperen, A. (2016). Occupational therapy and video modeling for children with autism. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 9(3), 226–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2016.1195603

- Bolourian, Y., Losh, A., Hamsho, N., Eisenhower, A., & Blacher, J. (2021). General education teachers’ perceptions of autism, inclusive practices, and relationship building strategies. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52(9), 3977–3990. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05266-4

- Bottema-Beutel, K., Kapp, S. K., Lester, J. N., Sasson, N. J., & Et Hand, B. N. (2020). Avoiding ableist language: Suggestions for autism researchers. Autism in Adulthood, 3(1), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0014

- Boujut, E., Popa-Roch, M., Palomares, E.-A., Dean, A., & Cappe, E. (2017). Self-efficacy and burnout in teachers of students with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 36, 8–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2017.01.002

- Canadian Academy of Health Sciences. (2022). Autism in Canada: Considerations for future public policy development - weaving together evidence and lived experience. CAHS. https://cahs-acss.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/CAHS-Autism-in-Canada-Considerations-for-future-public-policy-development.pdf

- Carrington, S., Saggers, B., Webster, A., Harper-Hill, K., & Nickerson, J. (2020). What universal design for learning principles, guidelines, and checkpoints are evident in educators’ descriptions of their practice when supporting students on the autism spectrum? International Journal of Educational Research, 102, 101583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101583

- CAST. (2018). Universal design for learning guidelines version 2.2. https://udlguidelines.cast.org

- Chodiman-Soto, R., Pooley, J., Cohen, L., & Taylor, M. (2012). Students with ASD in mainstream primary education settings: Teachers’ experiences in Western Australian classrooms. Australasian Journal of Special Education, 36, 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1017/jse.2012.10

- Clark, M., Adams, D., Roberts, J., & Westerveld, M. (2020). How do teachers support their students on the autism spectrum in Australian primary schools? Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 20(1), 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12464

- Clark, G. F., Rioux, J. E., Chandler, B. E., & Cashman, J. (2019). Best practices for occupational therapy in schools (2e ed.). AOTA.

- Collins, A., Joseph, D., & Bielaczyc, K. (2004). Design research: Theoretical and methodological issues. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(1), 15–42. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1301_2

- Conseil supérieur de l’éducation. (2017). Pour une école riche de tous ses élèves: S’adapter à la diversité des élèves, de la maternelle à la 5e année du secondaire. https://www.cse.gouv.qc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/50-0500-AV-ecole-riche-eleves.pdf

- Corkum, P., Bryson, S. E., Smith, I. M., Giffen, C., Hume, K., & Power, A. (2014). Professional development needs for educators working with children with autism spectrum disorders in inclusive school environments. Exceptionality Education International, 24(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.5206/eei.v24i1.7709

- Crompton, C. J., Hallett, S., Axbey, H., McAuliffe, C., & Cebula, K. (2023). ‘Someone like-minded in a big place’: Autistic young adults’ attitudes towards autistic peer support in mainstream education. Autism, 27(1), 76–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613221081189

- Dallman, A. R., Williams, K. L., & Villa, L. (2022). Neurodiversity-affirming practices are a moral imperative for occupational therapy. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 10(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.1937

- Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X08331140

- Dillon, G. V., & Underwood, J. D. M. (2012). Parental perspectives of students with autism spectrum disorders transitioning from primary to secondary school in the United Kingdom. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 27(2), 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357612441827

- Egan, M., & Restall, G. (2022). Promoting occupational participation: Collaborative relationship-focused occupational therapy. CAOT.

- Fecteau, S.-M., Normand, C. L., Normandeau, G., Cloutier, I., Guerrero, L., Turgeon, S., & Poulin, M.-H., (SOUMIS). (2024). “Not a trouble”: A mixed-method study of autism-related language preference of French-Canadian adults from the autism community. Neurodiversity.

- Ferreira, J. P., Ghiarone, T., Cabral Júnior, C. R., Furtado, G. E., Moreira Carvalho, H., Andrade Toscano, C. V., & Andrade Toscano, C. V. (2019). Effects of physical exercise on the stereotyped behavior of children with autism spectrum disorders. Medicina, 55(10), 685. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55100685

- Finke, E. H., McNaughton, D. B., Drager, K. D. R., & Drager, K. D. R. (2009). “All children can and should have the opportunity to learn”: General education teachers’ perspectives on including children with autism spectrum disorder who require AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 25(2), 110–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434610902886206

- Grandisson, M., Chabot, L., Hamel, C., Couture, M. M., Chrétien-Vincent, M., Bussières, E. L. (2024). Building occupational therapists’ capacity to support school personnel involved with autistic students. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools & Early Intervention.

- Grandisson, M., Rajotte, E. M., Godin, J., Chrétien-Vincent, M., Milot, E. L., & Desmarais, C. (2020). Autism spectrum disorder: How can occupational therapists support schools? Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 87(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417419838904

- Gregor, E. M. C., & Campbell, E. (2001). The attitudes of teachers in Scotland to the integration of children with autism into mainstream schools. Autism, 5(2), 189–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361301005002008

- Grynszpan, O., Gal, F., Perez-Diaz, E., & Gal, E. (2014). Innovative technology-based interventions for autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. Autism, 18(4), 346–361. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361313476767

- Gunn, K. C. M., & Delafield-Butt, J. T. (2016). Teaching children with autism spectrum disorder with restricted interests: A review of evidence for best practice. Review of Educational Research, 86(2), 408–430. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315604027

- Hartley, M., Dorstyn, D., & Due, C. (2019). Mindfulness for children and adults with autism spectrum disorder and their caregivers: A meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(10), 4306–4319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04145-3

- Hodges, A., Joosten, A., Bourke-Taylor, H., & Cordier, R. (2020). School participation: The shared perspectives of parents and educators of primary school students on the autism spectrum. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2019.103550

- Holcombe, W., & Plunkett, M. (2016). The bridges and barriers model of support for high-functioning students with asd in mainstream schools. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 41(9), 27–47. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2016v41n9.2

- Horgan, F., Kenny, N., & Flynn, P. (2023). A systematic review of the experiences of autistic young people enrolled in mainstream second-level (post-primary) schools. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 27(2), 526–538. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613221105089

- Hughes, H., Franz, J., & Willis, J. (2019). School spaces for student wellbeing and learning : Insights from research and practice. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6092-3

- Humphrey, N., & Symes, W. (2010). Perceptions of social support and experience of bullying among pupils with autistic spectrum disorders in mainstream secondary schools. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 25(1), 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856250903450855

- Hymers, B., Chaiet, R., & Piatak, J. (2019). Comparing the effects of a humor-based group and a board game group on social participation in students with moderate to severe autism. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(4), 7311505123–7311505121. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2019.73S1-RP104C

- Institut national d’excellence en santé et en services sociaux. (2014). L’efficacité des interventions de réadaptation et des traitements pharmacologiques pour les enfants de 2 à 12 ans ayant un trouble du spectre de l’autisme : édition révisée. ETMIS, 10(3), 1–67. https://www.inesss.qc.ca/fileadmin/doc/INESSS/Rapports/ServicesSociaux/INESSS_InterventionsReadap_TraitementPharmaco_EnfantsAut.pdf

- Kanakri, S. M., Shepley, M., Varni, J. W., & Tassinary, L. G. (2017). Noise and autism spectrum disorder in children: An exploratory survey. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 63, 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2017.02.004

- Kasari, C., Dean, M., Kretzmann, M., Shih, W., Orlich, F., Whitney, R., & King, B. (2016). Children with autism spectrum disorder and social skills groups at school: A randomized trial comparing intervention approach and peer composition. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(2), 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12460

- Katz, J., Knight, V., Mercer, S. H., & Skinner, S. Y. (2020). Effects of a universal school-based mental health program on the self-concept, coping skills, and perceptions of social support of students with developmental disabilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(11), 4069–4084. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04472-w

- Kim, S., Koegel, R. L., & Koegel, L. K. (2017). Training paraprofessionals to target socialization in students with ASD: Fidelity of implementation and social validity. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 19(2), 102–114. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300716669813

- Kinnealey, M., Pfeiffer, B., Miller, J., Roan, C., Shoener, R., & Ellner, M. L. (2012). Effect of classroom modification on attention and engagement of students with autism or dyspraxia. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 66(5), 511. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2012.004010

- Koegel, L., Matos-Freden, R., Lang, R., & Koegel, R. (2012). Interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders in inclusive school settings. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(3), 401–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.11.003

- Koenig, K. P., Buckley-Reen, A., & Garg, S. (2012). Efficacy of the get ready to learn yoga program among children with autism spectrum disorders: A pretest-posttest control group design. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 66(5), 538. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2012.004390

- Koenig, K. P., Feldman, J. M., Siegel, D., Cohen, S., & Bleiweiss, J. (2014). Issues in implementing a comprehensive intervention for public school children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 42(4), 248–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/10852352.2014.943638

- Kretzmann, M., Shih, W., & Kasari, C. (2015). Improving peer engagement of children with autism on the school playground: A randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 46(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2014.03.006

- Kryzak, L. A., Bauer, S., Jones, E. A., & Sturmey, P. (2013). Increasing responding to others’ joint attention directives using circumscribed interests. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 46(3), 674–679. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.73

- Lang, R., Koegel, L. K., Ashbaugh, K., Regester, A., Ence, W., & Smith, W. (2010). Physical exercise and individuals with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(4), 565–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2010.01.006

- Law, M., Cooper, B., Strong, S., Stewart, D., Rigby, P., & Letts, L. (1996). The person-environment-occupation model: A transactive approach to occupational performance. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(1), 9–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841749606300103

- Lindsay, S., Proulx, M., Scott, H., & Thomson, N. (2014). Exploring teachers’ strategies for including children with autism spectrum disorder in mainstream classrooms. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 18(2), 101–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2012.758320

- Lindsay, S., Proulx, M., Thomson, N., & Scott, H. (2013). Educators’ challenges of including children with autism spectrum disorder in mainstream classrooms. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 60(4), 347–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2013.846470

- Long, A. C., Hagermoser Sanetti, L. M., Collier-Meek, M. A., Gallucci, J., Altschaefl, M., & Kratochwill, T. R. (2016). An exploratory investigation of teachers’ intervention planning and perceived implementation barriers. Journal of School Psychology, 55, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2015.12.002

- Lüddeckens, J., Anderson, L., & Östlund, D. (2022). Principals’ perspectives of inclusive education involving students with autism spectrum conditions: A Swedish case study. Journal of Educational Administration, 60(2), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-02-2021-0022

- Macdonald, L., Trembath, D., Ashburner, J., Costley, D., & Keen, D. (2018). The use of visual schedules and work systems to increase the on‐task behaviour of students on the autism spectrum in mainstream classrooms. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 18(4), 254–266. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12409

- Majoko, T. (2016). Inclusion of children with autism spectrum disorders: Listening and hearing to voices from the grassroots. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(4), 1429–1440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2685-1

- Martin, C. S. (2016). Exploring the impact of the design of the physical classroom environment on young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 16(4), 280–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12092

- Martin, N., Milton Damian Elgin, M., Krupa, J., Brett, S., Bulman, K., Callow, D., & Wilmot, S. (2019). The sensory school: Working with teachers, parents and pupils to create good sensory conditions. Advances in Autism, 5(2), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1108/AIA-09-2018-0034

- McAllister, K., & Sloan, S. (2016). Designed by the pupils, for the pupils: An autism-friendly school. British Journal of Special Education, 43(4), 330–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8578.12160

- McCullough, M. I. (2014). Teacher self-efficacy in working with children with autism in the general education classroom (publication 3614480) [ doctorat thesis]. ProQuest LLC. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1518143588

- McKenney, S., & Reeves, T. (2013). Conducting educational design research. Routledge.

- Meindl, J. N., Delgado, D., & Casey, L. B. (2020). Increasing engagement in students with autism in inclusion classrooms. Children and Youth Services Review, 111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104854

- Milton, D. E. M. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: The ‘double empathy problem’. Disability & Society, 27(6), 883–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.710008

- Mostafa, M. (2008). An architecture for autism: Concepts of design intervention for the autistic user. International Journal of Architectural Research, 2, 189–211. https://doi.org/10.26687/ARCHNET-IJAR.V2I1.182

- Mostafa, M. (2014). Architecture for autism: Autism aspectss™ in school design. International Journal of Architectural Research, 8(1), 143–158. https://doi.org/10.26687/archnet-ijar.v8i1.314

- Mostafa, M. (2018). Designing for autism: An ASPECTSS™ post-occupancy evaluation of learning environments. International Journal of Architectural Research, 12(3), 308. https://doi.org/10.26687/archnet-ijar.v12i3.1589

- National Autism Center. (2015). Evidence-based practice and autism in the schools: An educator’s guide to providing appropriate interventions to students with autism spectrum disorder (2nd ed.). https://www.unl.edu/asdnetwork/docs/NACEdManual_2ndEd_FINAL.pdf

- Nicholson, H., Kehle, T. J., Bray, M. A., & Van Heest, J. (2011). The effects of antecedent physical activity on the academic engagement of children with autism spectrum disorder. Psychology in the Schools, 48(2), 198–213. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20537

- Oliver-Kerrigan, K. A., Christy, D., & Stahmer, A. C. (2021). Practices and experiences of general education teachers educating students with autism. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 56(2), 158–172.

- Oriel, K. N., George, C. L., Peckus, R., & Semon, A. (2011). The effects of aerobic exercise on academic engagement in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 23(2), 187–193. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEP.0b013e318218f149

- Petrus, C., Adamson, S. R., Block, L., Einarson, S. J., Sharifnejad, M., & Harris, S. R. (2008). Effects of exercise interventions on stereotypic behaviours in children with autism spectrum disorder. Physiotherapy Canada, 60(2), 134–145. https://doi.org/10.3138/physio.60.2.134

- Pfeiffer, B., Coster, W., Snethen, G., Derstine, M., Piller, A., & Tucker, C. (2017). Caregivers’ perspectives on the sensory environment and participation in daily activities of children with autism spectrum disorder. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(4), 1–7104220028. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2017.021360

- Rajotte, É., Grandisson, M., Hamel, C., Couture, M. M., Desmarais, C., Gravel, M., & Chrétien-Vincent, M. (2022). Inclusion of autistic students: Promising modalities for supporting a school team. Disability and Rehabilitation, 45(7), 1258–1268. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2022.2057598

- Reutebuch, C. K., El Zein, F., & Roberts, G. J. (2015). A systematic review of the effects of choice on academic outcomes for students with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 20, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2015.08.002

- Rotheram-Fuller, E., Kasari, C., Chamberlain, B., & Locke, J. (2010). Social involvement of children with autism spectrum disorders in elementary school classrooms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(11), 1227–1234. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02289.x

- Saggers, B., Tones, M., Dunne, J., Trembath, D., Bruck, S., Webster, A., & Wang, S. (2019). Promoting a collective voice from parents, educators and allied health professionals on the educational needs of students on the autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(9), 3845–3865. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04097-8

- Sansosti, F., Doolan, M., Remaklus, B., Krupko, A., & Sansosti, J. (2015). Computer-assisted interventions for students with autism spectrum disorders within school-based contexts: A quantitative meta-analysis of single-subject research. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2(2), 128–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-014-0042-5

- Sowa, M., & Meulenbroek, R. (2012). Effects of physical exercise on Autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(1), 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2011.09.001

- Sreckovic, M. A., Brunsting, N. C., & Able, H. (2014). Victimization of students with autism spectrum disorder: A review of prevalence and risk factors. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(9), 1155–1172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.06.004

- Stephenson, J., Browne, L., Carter, M., Clark, T., Costley, D., Martin, J., & Sweller, N. (2021). Facilitators and barriers to inclusion of students with autism spectrum disorder: Parent, teacher, and principal perspectives. Australasian Journal of Special & Inclusive Education, 45(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/jsi.2020.12

- Sterman, J., Gustafson, E., Eisenmenger, L., Hamm, L., & Edwards, J. (2023). Autistic adult perspectives on occupational therapy for autistic children and youth. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research, 43(2), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/15394492221103850

- Stokes, M. A., Thomson, M., Macmillan, C. A., Pecora, L., Dymond, S. R., & Donaldson, E. (2017). Principals’ and teachers’ reports of successful teaching strategies with children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 32(3–4), 192–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573516672969

- Strong, S., Rigby, P., Stewart, D., Law, M., Letts, L., & Cooper, B. (1999). Application of the person-environment-occupation model: A practical tool. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 66(3), 122–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841749906600304

- Sulek, R., Trembath, D., Paynter, J., & Keen, D. (2019). Empirically supported treatments for students with autism: General education teacher knowledge, use, and social validity ratings. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 22(6), 380–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/17518423.2018.1526224

- Symes, W., & Humphrey, N. (2011). School factors that facilitate or hinder the ability of teaching assistants to effectively support pupils with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) in mainstream secondary schools. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 11(3), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2011.01196.x

- Tanner, K., Hand, B. N., O’Toole, G., & Lane, A. E. (2015). Effectiveness of interventions to improve social participation, play, leisure, and restricted and repetitive behaviors in people with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 69(5), 6905180010p6905180011. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2015.017806

- Taylor, A., Beamish, W., Tucker, M., Paynter, J., & Walker, S. (2021). Designing a model of practice for Australian teachers of young school-age children on the autism spectrum. Journal of International Special Needs Education, 24(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.9782/JISNE-D-18-00017

- UNESCO. (2020). Global education monitoring report 2020, inclusion and education: All means all. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373718

- VanderKaay, S., Dix, L., Rivard, L., Missiuna, C., Ng, S., Pollock, N., & Campbell, W. (2021). Tiered approaches to rehabilitation services in education settings: Towards developing an explanatory programme theory. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 70(4), 540–561. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2021.1895975

- Warren, B., Buckingham, Parsons, K., & Parsons, S. (2021). Everyday experiences of inclusion in primary resourced provision: The voices of autistic pupils and their teachers. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 36(5), 803–818. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2020.1823166

- Watkins, L., Ledbetter-Cho, K., O’reilly, M., Barnard-Brak, L., & Garcia-Grau, P. (2019). Interventions for students with autism in inclusive settings: A best-evidence synthesis and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 145(5), 490–507. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000190

- Watling, R., & Spitzer, S. (2018). Autism across the lifespan: A comprehensive occupational therapy approach (4th ed.). AOTA Press.

- Watroba, A., Luttinen, J., Lappalainen, P., Tolonen, J., & Ruotsalainen, H. (2023). Effectiveness of school-based occupational therapy interventions on school skills and abilities among children with attention deficit hyperactivity and autism spectrum disorders: Systematic Review. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 1–33. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2023.2224793

- Williams, E. I., Gleeson, K., & Jones, B. E. (2019). How pupils on the autism spectrum make sense of themselves in the context of their experiences in a mainstream school setting: A qualitative metasynthesis. Autism, 23(1), 8–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361317723836

- Wong, C., Odom, S. L., Hume, K. A., Cox, A. W., Fettig, A., Kucharczyk, S., & Schultz, T. R. (2015). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism spectrum disorder: A comprehensive review. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 45(7), 1951–1966. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2351-z

- Wood. (2021). Autism, intense interests and support in school: From wasted efforts to shared understandings. Educational Review, 73(1), 34–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2019.1566213