ABSTRACT

The Task Force “Towards a Multidimensional Index to Child Growth”, within the International Union of Nutritional Sciences, developed a capability framework for child growth (CFCG). This framework aims to redefine child growth monitoring, expanding beyond weight and height to encompass parental capabilities. We further operationalised the CFCG in hard-to-reach haor areas of Bangladesh, resulting in the publication of a list outlining parental capabilities for child growth. This paper details the methodology and participatory process employed, offering reflections on how our research followed the criteria proposed by Robeyns for identifying capabilities. First, we built a contextualised list of capabilities for child growth based on discussions with local experts. This list underwent further adaptation for haor regions in two rounds. Initially, we used a doxastic interviewing methodology to create a draft emic list of capabilities for child growth. Subsequently, utilising an epistemic methodology, we refined the list. The doxastic interviews focused on “understanding” the interviewees; the epistemic interviews facilitated equal communication between interviewer and interviewee, promoting knowledge co-creation. This rigorous approach validates the findings with the affected communities and supports implementation of the CFCG in policy and practice. This methodology could be extended to other pertinent research areas for capability scholars.

Introduction

Healthy child growth starts in utero, and is associated with the mother’s nutritional status and health (Black et al. Citation2013). Conventionally, child growth is defined as a biological process influenced by several direct and indirect determinants (Mosley and Chen Citation2003; Stewart et al. Citation2013; UNICEF Citation1990). For example, the UNICEF Conceptual Framework for “Causes of Malnutrition and Death” states that malnutrition is caused by immediate determinants, such as inadequate dietary intake and illness; intermediate determinants, such as the inadequate availability and accessibility of food, inadequate care for mothers and children, the inadequate availability of health services, and poor education for caregivers; as well as basic determinants, such as a lack of financial resources (UNICEF Citation1990). This framework was adapted in the Lancet Series on Maternal and Child Nutrition 2013 (Black et al. Citation2013). Haisma, Yousefzadeh, and Hensbroek (Citation2018) introduced a new direction for conceptualising child growth, evaluating healthy child growth as an aggregated outcome of a set of indicators, encompassing biological and contextual dimensions (Haisma, Yousefzadeh, and Hensbroek Citation2018). This multidimensional concept of child growth is built on Sen’s capability approach (Sen Citation2003; Citation2001).

The capability approach focuses on an individual’s real opportunities (that are multidimensional), rather than just physical health outcomes, and makes an individual’s agency explicit in the causal chain (Haisma, Yousefzadeh, and Hensbroek Citation2018). Based on this concept, child growth can be defined as the achievement of a certain set of capabilities of children and their caregivers, such as being able to be fed, sheltered, or cared for. The multidimensional model acknowledges children’s and caregivers’ agency, incorporating both biomedical (anthropometric) and contextual dimensions (e.g. care and shelter) in the monitoring process. This more inclusive approach should ultimately contribute to further reductions (of inequalities) in child mortality and morbidity by enhancing parent counselling from a multidimensional and context-specific perspective.

The Task Force “Towards a Multidimensional Index to Child Growth”, within the International Union of Nutritional Sciences, developed a multidimensional model for child growth capabilities that builds on earlier work by Biggeri et al. (Citation2006) on child wellbeing, Bronfenbrenner’s ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner and Ceci Citation1994; Bronfenbrenner and Morris Citation2006), and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations General Assembly Citation1989). This multidimensional model, known as the capability framework for child growth (CFCG), presents how children’s capabilities and their interactions with caregivers’ capabilities are shaped across the micro-, meso-, exo-, and macrosystems (Yousefzadeh et al. Citation2019). According to the CFCG (), children draw their entitlements from microsystems through their proximate relationships with their parents or caregivers. For example, a child’s capability to grow well is dependent on the parents’ capabilities to provide the child with good care. The mesosystem (relationships between caregivers, doctors, or teachers), the exosystem (relationships across two or more settings), and the macrosystem (belief systems, social norms, culture, and institutional settings) influence the child’s development indirectly (Yousefzadeh et al. Citation2019). According to this framework, individual capabilities are shaped by: (1) people’s access to resources (e.g. income, intelligence, welfare services); (2) the ability to convert these resources into real opportunities (depending on available facilitators and/or barriers at the personal, sociocultural, or environmental level); and (3) people’s agency to pursue their valuable goals. Thus, child growth is constituted by the interactions of individual and external capabilities (parents) and the agency of the child and of her/his parents.

Figure 1. Capability Framework to Child Growth by Yousefzadeh et al. [Citation2019]. Adapted by permission from Springer Nature: Springer Nature, Child Indicators Research, Copyright (2018).

![Figure 1. Capability Framework to Child Growth by Yousefzadeh et al. [Citation2019]. Adapted by permission from Springer Nature: Springer Nature, Child Indicators Research, Copyright (2018).](/cms/asset/ab286882-881a-45a2-9f60-8ca8f72552fd/cjhd_a_2330885_f0001_oc.jpg)

Identifying capabilities is the first step towards operationalising the CFCG, ideally through a participatory process. A participatory approach offers opportunities to identify capabilities in a democratic way, and creates space to uncover the contextual dimensions from an emic perspective (Alkire Citation2013; Robeyns Citation2005; Sen Citation2005; Citation2004). Although some prior studies have employed a participatory approach to identify capabilities (Al-Janabi, Flynn, and Coast Citation2012; Anich et al. Citation2011; Biggeri et al. Citation2006; Biggeri and Ferrannini Citation2014; Burchardt and Vizard Citation2007; Burchardt and Vizard Citation2009; Conradie Citation2013; Conradie and Robeyns Citation2013; Domínguez-Serrano, del Moral-Espín, and Muñoz Citation2019; Greco et al. Citation2015; Grewal et al. Citation2006; Kellock and Lawthom Citation2011; Mitra et al. Citation2013; Vizard and Burchardt Citation2008; Yap and Yu Citation2016; see also “Identifying capabilities using a participatory approach” below), clear direction on how to co-create such a capability list in a contextualised and valid way with the community of interest is lacking. We address this information gap by reflecting on the participatory process and methodology we used to identify capabilities for child growth in a vulnerable setting – in a haor region of Bangladesh. The findings of that study and the capabilities list for child growth that was created at the child, mother, father, and household level have been presented elsewhere (Chakraborty et al. Citation2020; Chakraborty, Darak, and Haisma Citation2020). These findings shed light on the contextual dimensions of child growth and highlight the parental capabilities crucial for nutritionists, policy-makers, and other stakeholders working to address societal challenges to improve child growth and nutrition outcomes. In the current paper, we reflect on the participatory methodology employed in conducting the study. We explain how the concept of capabilities for child growth can be translated to community members to facilitate a process of co-creation, and detail how their responses can be analysed to construct a validated list of capabilities for child growth.

We present our reflection in three sections. First, we provide a brief overview of the literature on participatory research for identification of capabilities and we highlight the gap we aim to address. Second, we examine the methodology we employed at different stages, from identification through to contextualisation and validation of the capability list. Finally, in the discussion section, we assess the extent to which we adhered to the criteria proposed by Robeyns (Citation2003; Citation2005) to minimise epistemological biases when constructing such a list. We also reflect on the methodology in terms of its relevance for the co-creation of a contextualised list of capabilities, using doxastic and epistemic interview techniques in vulnerable settings like haor, with a view to deriving valuable lessons for the future application of the capability approach in a participatory way.

Identifying Capabilities Using a Participatory Approach

There is a growing body of literature that has employed participatory research in different ways for the identification of capabilities (Al-Janabi, Flynn, and Coast Citation2012; Anich et al. Citation2011; Biggeri et al. Citation2006; Biggeri and Ferrannini Citation2014; Burchardt and Vizard Citation2007; Burchardt and Vizard Citation2009; Chakraborty Citation2022; Conradie Citation2013; Conradie and Robeyns Citation2013; Domínguez-Serrano, del Moral-Espín, and Muñoz Citation2019; Greco et al. Citation2015; Grewal et al. Citation2006; Kellock and Lawthom Citation2011; Mitra et al. Citation2013; Vizard and Burchardt Citation2008; Yap and Yu Citation2016). Biggeri et al. (Citation2006) were the first to apply a participatory approach to construct an open-ended list of capabilities for children’s wellbeing (aged 11–17 years). They identified the capabilities by reviewing lists compiled by Nussbaum (Citation2000) and Robeyns (Citation2003), along with literature on children’s issues by UNICEF and UNESCO, and then justified the list based on 42 articles of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989). Finally, to increase the legitimacy of the list, they used a participatory method to conduct a survey with a group of children from developed and developing regions attending the Children’s World Congress on Child Labour in Florence, Italy, in 2004 (Biggeri et al. Citation2006). They validated each capability on the proposed list using a quantitative questionnaire and gathered additional insights through qualitative participatory tools, such as interview guides and intensive game activities.

Anich et al. (Citation2011) employed a similar mixed-methods approach to analyse capability deprivation among street children in Kampala, Uganda, contributing to the design of targeted rehabilitation intervention programmes. They used a structured questionnaire to identify the capabilities and functionings built on the list of capabilities predefined by Biggeri et al. (Citation2006). Then they validated the data with the children using participatory research tools such as thematic drawings, mobility maps, photo essays, life histories, and peer interviews. Kellock and Lawthom used a participatory approach to explore dimensions of the wellbeing of UK primary school children by capturing the voices of a group of children through creative and visual methods (Kellock Citation2020; Kellock and Lawthom Citation2011). Children narrated their feelings by drawing facial expressions, by photographing different parts of their school and describing their significance, and by group mind-mapping.

Some scholars have applied a participatory approach to assess the impact of various development interventions in expanding the capabilities of programme beneficiaries (Biggeri and Ferrannini Citation2014; Conradie Citation2013; Conradie and Robeyns Citation2013; Greco et al. Citation2015). Conradie and colleagues adapted a participatory approach in their research that focused on economically marginalised women in Khayelitsha near Cape Town involved in a five-year intervention programme (Conradie Citation2013; Conradie and Robeyns Citation2013). The women were encouraged to reflect on their life experiences and societal constraints influencing the selection and realisation of their aspirations. Support was then provided to help them access the particular resources they needed to expand their capabilities. Finally, the researchers analysed and reflected on the capability outcomes of these interventions.

Stoecklin, Berchtold-Sedooka, and Bonvin (Citation2023) conducted a study in three counties in Switzerland to understand the participatory capability of children regarding their organised leisure activities. The authors defined “participatory capability” as the “capacity that the child has to effectively participate in defining and making choices affecting his or her own life”. They interviewed children, aged between 13 and 16, in two rounds using semi-structured interview guides and a “mind-mapping tree”. The mind-mapping tree sessions were facilitated using thematic cardboard cards. Participants were instructed to place these cards on the branches of a tree drawn on a blank sheet of paper. According to the instruction, the left-hand side of the tree should include elements or influences coming from the leisure centre, and the right-hand side should represent things coming from the child. The findings of the study identified various forms of participatory capabilities and explained how societal (economical, political, and organisational) and personal factors shape these capabilities to enable effective participation by children.

Several examples in the area of child health and wellbeing show how a participatory approach can give voice to communities. For example, Priest et al. (Citation2012) explored the Aboriginal perspectives of child health and wellbeing in the urban setting of Melbourne, Australia. In their study, a non-Aboriginal researcher volunteered in the health service of the communities for 12 months to design a proposal in consultation with both staff and community members. Then, they utilised qualitative research tools to collect data in two waves: the first wave provided preliminary insights, informing the second wave of interviews. Employing constructivist grounded theory, the data analysis incorporated emic perspectives from the communities, shaping a conceptual framework for Aboriginal child health and wellbeing.

Beyond children’s wellbeing, various studies have employed a participatory approach to explore the wellbeing of diverse population groups, including adults (Al-Janabi, Flynn, and Coast Citation2012), older individuals in the UK (Grewal et al. Citation2006), and Indigenous communities in the Kimberley region of Australia (Yap and Yu Citation2016). For example, Yap and Yu (Citation2016) adopted an emic approach to explore Indigenous wellbeing in the remote coastal town of Broome in the southwest of the Kimberley region of Australia. They collected data in three rounds of research. First, through semi-structured interviews with Yawuru community members, they identified broader themes and relevant indicators for capabilities and functionings. This informed the second round, involving focus group discussions with Yawuru men and women. Participants selected the relevant indicators for each of the thematic boxes that they valued and deemed meaningful for their wellbeing. The researchers then tabulated responses by frequencies and constructed a refined list of capabilities.

Most of the studies described above used qualitative instruments to identify capabilities, and then subsequently validated these capabilities within the relevant communities through various data collection tools, many of which involved participatory research. The tools were tailored to the nature and characteristics of the communities, or benchmarked against existing research. The extent of participation in these studies varied, from involvement at the design or identification phase of capabilities right through to the validation of findings at the end of the research process. This paper adds to existing evidence by reflecting on the process of co-creation of knowledge with communities, providing guidance on the steps that are needed to operationalise, contextualise, and validate capability lists for multidimensional child growth across various contexts and other fields of capability research. In addition, through the focus on very young children (< 2 years) in our research, we involved parents or caregivers in co-creating the capability list to achieve healthy growth outcomes in hard-to-reach haor areas of Bangladesh.

Methodology to Build the List

In this section, we begin by providing an overview of the geographical context of haor, where the list was produced. We also outline the characteristics of the participants with whom we interacted. Then, we explain the methodology employed to apply the participatory approach in identifying the capabilities for healthy child growth.

Geographical Context and Participants

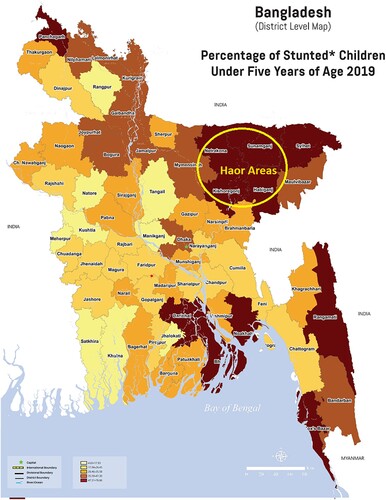

Haor areas () are located in northeastern Bangladesh, spreading over the districts of Sunamganj, Sylhet, Habiganj, Moulavibazar, Kishorgonj, Netrokona, and Brahminbaria. The landmass of the areas is submerged by upstream rain runoff, remaining underwater for more than six months of the year. Almost 19 million people reside in different haor areas. Health and wellbeing indicators, including adult literacy (37%), use of soap for hand washing (26%), maternal undernutrition (24%: BMI < 18.5), and childhood stunting (> 45%), are relatively poor in these areas (HKI and JPGSPH Citation2016; Nath Citation2013). Most people living in haor build their houses slightly above the ground in clusters to safeguard them from flooding (Chakraborty et al. Citation2020). They mainly rely on rice-based agriculture to feed their families. However, their agricultural activities and daily lives are severely affected by long-term floods and periods of drought (BHWDB Citation2012; Chakraborty et al. Citation2020). Young children, and particularly those under two years old, are vulnerable and at risk of experiencing malnutrition and poor growth.

Given the geographical remoteness and isolation of haor areas, understanding the context was a crucial first step to gradually collecting information about capabilities for healthy child growth. The study site would determine the context of the list of capabilities we aimed to identify, and was therefore chosen carefully. We selected haor-dominated subdistricts: Derai in Sunamganj district and Baniachang in Habiganj district. From each of the subdistricts, we included participants who were the parents of children under 2 years of age, residing in moderate and deep haor areas prone to heavy flooding. Most of the participants had incomplete primary education, and their literacy level was limited to being able to sign their own name (Chakraborty et al. Citation2020). The mothers’ ages ranged from 16 to 35 years; the fathers’ ages ranged from 21 to 40 years. Muslims made up the majority of attendees, with Hindus making up the minority. The women’s main job was to handle household chores and care for the children. Most of the men engaged in paddy cultivation when the fields were not flooded, while others managed small businesses, such as selling betel nuts or vegetables, or working as day labourers (boat rowers, carpenters, barbers, earth diggers, masons, and rickshaw pullers). During floods, the men moved to other areas to work as day labourers, leaving the women in financial deficit and reliant upon support from neighbours or other family members. Those who stayed in haor during floods typically earned income through fishing or grocery businesses; otherwise, they remained jobless.

Process of Identifying and Contextualising the List of Capabilities for Healthy Child Growth

The process of creating a list of capabilities for child growth was initiated by Yousefzadeh et al. (Citation2019), who reviewed the literature that defined children’s health, growth, or development as a multidimensional concept at the input, process, or output levels. Extracts from the literature review resulted in a draft matrix for healthy child growth, encompassing dimensions beyond physical growth, such as cognitive and socioemotional development at both the child and parental levels (Yousefzadeh et al. Citation2019). This matrix was further refined in a discussion with scientists from diverse disciplines (epidemiology, nutrition, political and social sciences). They focused on exploring the link between the capability approach and the social determinants of health and children’s rights, and also discussed various capabilities in the prenatal phase in relation to the health of the pregnant mother and the growing foetus. This inventory is acknowledged as a universal list of capabilities for child growth, incorporating all relevant capabilities for children worldwide.

For our research, we contextualised the list of capabilities established by Yousefzadeh et al. (Citation2019). This contextualisation involved a process of developing and refining the list of capabilities to align with the contextual factors of the haor areas of Bangladesh. This step is fundamental to operationalising the capability approach, as contextual factors uniquely shape individuals’ capabilities. The first step of this process was to incorporate feedback from local experts on health, nutrition, agriculture, economics, and social sciences, using the universal matrix for multidimensional child growth developed by Yousefzadeh et al. (Citation2019). We gathered this feedback at a brainstorming meeting held at BRAC Bangladesh. Experts at the meeting included academics and professionals from government entities, nongovernmental organisations, and international agencies in Bangladesh. Their expertise spanned various fields, including nutrition, medicine, public health, agriculture, and economics.

To facilitate the meeting, the first author introduced participants to the constitutive elements of the capability approach – endowments, conversion factors, agency, capabilities, and functionings – in the context of child growth. The first author explained how the concept of capabilities shapes multidimensional child growth outcomes that extend beyond biological indicators. This perspective also incorporates various societal and environmental dimensions into the process of growth monitoring. Examples were provided to demonstrate how the capabilities of parents may differ due to individual and societal factors that influence the process of providing good care to children. Through group discussions, meeting participants were then invited to answer a range of questions, such as: “What capabilities does a child or a parent need to achieve healthy child growth in Bangladesh?” “What are the expected outcomes for each of these capabilities, and what kinds of resources/conversion factors might influence them?” From their collaborative responses, an enhanced child growth matrix (see supplementary material) was formulated, incorporating all of the dimensions proposed by Yousefzadeh et al. (Citation2019), as well as additional dimensions suggested by the experts in Bangladesh.

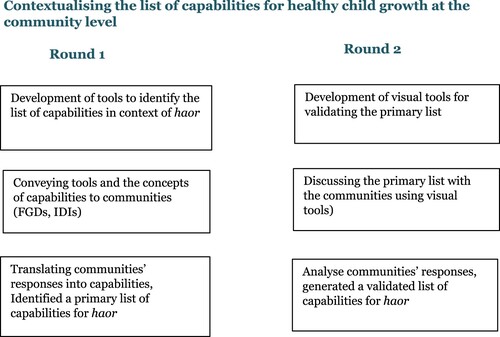

We then contextualised these capabilities to the specific realities of children in haor regions through two rounds of discussion with haor communities. In the first round, we developed a draft emic list of capabilities for child growth; in the second round, we elaborated and refined this list in collaboration with the community. Below, we describe how we constructed each round in this process ().

Community Round 1: Contextualising Capabilities for Healthy Child Growth in Haor Areas Using a Participatory Approach

At this step, our aim was to enhance our understanding of the context in haor areas, in order to identify child growth capabilities from the parents’ perspective. We used the initial list of capabilities, contextualised for Bangladesh, to inform the topics of the interview guides for this round. For example, the list informed decisions about which specific dimensions mattered for child growth in the context of haor, or to what extent contextual information was necessary to understand the complexity of child growth in haor. We selected focus group discussions (FGDs) and in-depth interviews (IDIs) with parents of children under two as the most effective techniques for gathering relevant information. This round comprised eight FGDs (four with fathers and four with mothers) and IDIs (four with fathers and four with mothers). Below, we outline the process of translating the concept of capabilities to parents and extracting their responses to form an emic list of capabilities.

A. Translating the Concept of Capabilities to the Communities

As our objective was to gain insights into context from the communities, we tailored the interview guides to provide participants adequate space to share their stories about their children’s growth outcomes. We initiated the IDIs and FGDs with general questions to build rapport. For example, we started the IDIs by asking participants about their daily lives and about who they lived with. We then gradually transitioned to contextual questions related to their livelihoods, seasonality, gender roles, and decision-making power. To explore seasonality, for instance, we asked participants about the types of seasonal variation they experienced in haor and how these changes affect their livelihoods. For the FGDs, we approached the same questions from a slightly different perspective, with the aim of gathering general knowledge about the communities. For example, participants were asked about what people do in haor, about how people earn a living, and about the seasonal impact on earnings. These rapport-building questions laid the foundation for the contextual questions, and guided further probing based on the responses. This sequence of questioning and probing opened up the space to move on to the specific topics of interest, namely child health, growth, and capabilities.

We then transitioned to the specific questions on capabilities. This required careful wording to ensure that the questions were understandable to the participants, as there was no straightforward approach to translating the concept of capabilities to the communities. For instance, to gather initial information on parents’ capabilities, we formulated the question as: “Who is considered a good father or a good mother in your area?” However, this question did not resonate with the participants’ perspectives, as their daily focus was primarily on meeting their basic survival needs. Because seeing oneself as a good parent or becoming a good parent was far beyond the scope of the participants’ thought processes, the question was perceived as unexpected. This led us to refine the question as follows: “What kinds of abilities or qualities does a mother or a father need to take good care of her/his children so that they stay healthy or grow well?” Participants were more responsive to this question, probably because they could relate the meaning of “abilities” to their own context.

Thus, to translate capabilities to the communities, rapport-building was a crucial component, as it allowed participants to share their life stories. The questions regarding their capabilities for healthy child growth needed careful framing to encourage thinking beyond immediate survival needs.

B. Translating Community Responses into Capabilities

The next challenge was to identify the relevant capabilities from participants’ discussions and stories. An essential part of our qualitative data analysis, as advocated by Hennink, Hutter, and Bailey (Citation2011), was the verbatim transcription of participants’ responses, and then reviewing them according to the underlying concepts of our research framework. We followed this procedure to extract the data aligned with the meaning of the constitutive elements of the capability approach, including resources, conversion factors, agency, and capabilities. This step was crucial in ensuring the accuracy of our list of capabilities, demanding a nuanced understanding of the conceptual differences between capabilities and commodities, as well as the external factors impeding resource transformation. To capture the emic views of participants, we used inductive coding, which enabled us to develop codes closely mirroring the actual data and articulated in the participants’ language. For example, in response to the question about what kinds of abilities a mother or father needs to take good care of her/his children, one participant said: “She must have maya (affection) and mohabbat (love) for her child. If she doesn’t have that, she would not be able to take care of her child.” We coded this response under “maternal capabilities” and defined it as a “mother’s capability to express maya and mohabbat”. When participants pointed to the importance of the collective capabilities of all household members, we categorised this response as “household’s capability” (e.g. “household’s capability to overcome the struggle with the earth to keep the child neat and clean”).

We considered all responses deemed relevant according to the underlying concept of capabilities – those aspects participants highlighted as valuable in achieving multidimensional child growth outcomes. Numerous participant responses were prompted by questions related to their stories, contexts, or specific dimensions such as health or domestic violence, rather than by specific questions about capabilities. These stories yielded more comprehensive insights into the interconnected capabilities that support each other in the process of achieving healthy growth. For example, a mother’s capability to stay healthy, her capability to stay away from domestic violence, and her capability to express love to her child are all interconnected.

Therefore, it was crucial to consider all responses pertaining to the fundamental concept of capabilities, whether they originated from contextual narratives or capability-specific inquiries directed at parents, children, or household members. Equally important was the need to capture the emic meaning of capabilities by closely adhering to the actual data. This approach enabled us to understand what each capability entails, to whom it applies, and whether it connects individuals or household members.

Community Round 2: Validating the List of Capabilities Using a Participatory Approach

After identifying the capabilities in the first round, our next priority was to ensure that all dimensions contributing to child growth and valued by the communities were adequately captured and included in the list, adhering to the exhaustion and nonreduction criterion (Robeyns Citation2003). Therefore, in this round, our main objective was to stimulate further discussion among the community members to assess consensus on each of the capabilities identified in the first round, and to gather additional stories to address any remaining gaps. We used two key measures in selecting the areas and designing the tools. First, we included a mix of new and old haor areas in this round. For example, we selected Derai from the previous round and we recruited Ashtagram as a new subdistrict. The main reasons for selecting Ashtagram were its remoteness and the dominance of deep haors that were not covered by the development interventions of BRAC during the survey period. Second, we employed visual methods as a tool to co-create knowledge during our discussions with the community members to validate the list of capabilities. Compared with verbal communications, visual images tap into deeper parts of human consciousness, providing additional validity and depth to the data and generating new insights (Bignante Citation2010; Glaw et al. Citation2017; Harper Citation2002). Below, we explain how we developed the visual tools and facilitated this process.

A. Process of Developing the Visual Tools and Conveying Them to the Communities

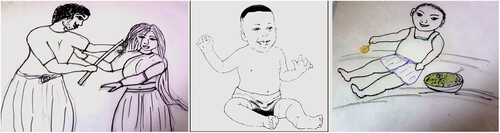

The visual tools were developed in consultation with experts, researchers, and BRAC programme personnel working in haor areas or familiar with the context. They included a set of drawings and pictures that conveyed the meaning of each capability to the communities. For instance, a drawing of “a husband attempting to beat his wife” was used to prompt discussions about a mother’s capability to stay away from domestic violence in connection with child growth (). The drawing elicited detailed and spontaneous interactions among participants. This is one mother’s response to the drawing:

When there is a baby inside the belly, if the husband beats the mother in that situation, it will harm the foetus, if the body of the baby’s mother gets shaken, then it will cause harm to the foetus. Then if the mother is beaten in front of the child, won’t the child’s mind turn weak by getting scared? (Mothers, Taral, Derai)

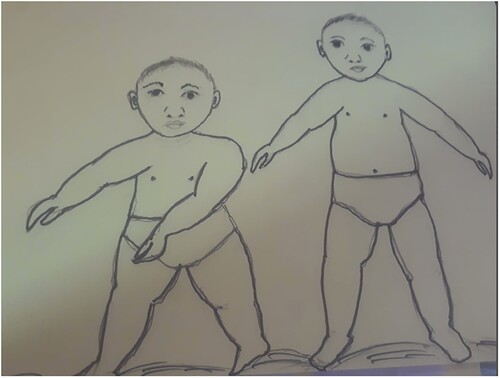

Figure 4. Example of drawings used in facilitating the participatory research. The first drawing was used to explain a mother’s capability to stay away from violence (drawn by Debashis Chakravorty). The rest two were demonstrated to explain a child’s capability to stay happy and playful (the second artwork of the child was sourced from: https://iycf.advancingnutrition.org/content/people-healthy-baby-6-24-mo-00a-noncountry-specific and the third drawing of the child was drawn by Debashis Chakravorty).

B. Process of Analysing the Responses of the Communities in Validating the List

In this round, our coding and analysis procedure was different from the first round, as our main objective was to ensure that the list included all important and relevant capabilities, in line with the exhaustion and nonreduction criterion. We applied three key questions to the data: (1) Do the stories from the second round give contextual information for the capabilities that is similar to the first round? (2) Do the stories reveal any new dimensions or capabilities of child growth not covered in the capability list created in the first round? (3) Does anything from the available list remain unstated by the participants, and if so, why? Guided by these questions, we reviewed the responses and coded them if they matched a specific capability from the primary list. Stories that could not be matched with any capability on the list but indicated a relevant dimension or capability of child growth were used to formulate a new capability. Next, the stories associated with each listed capability were compared with data from the first round, in line with the aforementioned questions.

This procedure ensured that the list was complete, accurate, and independent of researcher bias. For example, in the first round of data collection, a child’s smile, happiness, and playfulness appeared as interconnected indicators of good health and stimulators for child growth. However, after analysis and comparison in this data validation round, we realised that a child’s capability to stay happy and to be playful were interconnected yet distinct factors in the process of achieving healthy child growth. For happiness, participants explained that if the child is fed, s/he will stay healthy, and then s/he will stay happy and will grow well. For playfulness, they stated that if a child stays happy and healthy, s/he will play by shaking her/his body, and then will grow automatically. These distinct interpretations prompted the separation of happiness and playfulness into two different capabilities on the validated list. The following quotations exemplify how participants described happiness and playfulness during the validation round:

Happiness: If the baby is healthy, then the baby will stay happy and smiling. If the stomach is full, the baby will stay happy and smiling. If the body is okay, the baby will stay happy and smiling. But if the body is not okay, then the baby will cry. (Mothers, FGDs, Islampur, Ashtagram)

Playfulness: When the children are fed adequately they will grow. When they play, or shake their hands and legs, they grow automatically. (Mothers, FGDs, Vatipara, Derai)

Some of the insights were helpful in revealing new capabilities that had been overlooked in the first round. For example, we identified a child’s capability to have regular naps, to express through new words, and to cry; a mother’s capability to have a normal delivery, to space child births, and to avoid heavy workload during pregnancy; a father’s capability to share child care activities with the mother; and a household’s capability to source river water for showering the child during the dry season. We did not use specific drawings to elicit these capabilities. Instead, they emerged organically when participants were discussing interconnected capabilities. For example, we showed a drawing of two babies, one tall and one short (), to explain a child’s capability to grow in size, and asked why a child in their area might grow. Some participants (from Ashtagram) emphasised the importance of a mother’s capability to space her births. They explained that children in their community may not grow in size because women often become pregnant at short intervals through failure to follow family planning practices. They added that in such cases, the older baby does not get enough breastmilk, is susceptible to diseases, remains unhealthy, and exhibits stunted growth. One mother said:

If we have the baby a bit late then the other baby (former) would stay healthy, now if any such thing happens by mistake then we don’t know … if there is a foetus inside, the other baby will get less breastmilk, if the foetus grows inside the belly, this baby will not get breastmilk. Then if this baby gets less food, it will grow like this [indicating the picture of a stunted baby], it will grow slowly no?

Table 1. Process of exhaustion and non-reduction.

Discussion

We have shown how a list of capabilities for child growth can be created and validated using a participatory approach. Our process adhered to the criteria that Robeyns (Citation2003, 2005) developed for identifying capabilities. These criteria include explicit formulation, methodological discussion, sensitivity to context, different levels of generality, and exhaustion and nonreduction (Robeyns Citation2005; Citation2003). “Explicit formulation” means the list should be explicit, discussed, and defended. In our research, this was covered throughout the whole process: through expert consultations to create the universal list, through contextualising it with Bangladeshi experts, and subsequently through validating and defending it within the haor communities. The criterion of “methodological discussion” relates to clarifying and justifying the methodology, which we addressed by describing and reflecting on how an emic list of capabilities in a vulnerable setting like haor can be constructed; and on how the legitimacy of a list of capabilities that systematically engages the communities can be ensured. “Sensitivity to context” is reflected in two participatory research rounds, yielding a contextualised list of capabilities for healthy child growth in haor. “Different levels of generality” highlighted the need to construct our list in at least two phases – at an ideal level and at a pragmatic level. In our case, the contextualisation process followed several steps, beginning with contextualising the universal list of capabilities in discussion with local experts and then making community-level adjustments. Finally, we met the criterion of “exhaustion and nonreduction” by using various visual tools with similar and more remote haor communities to validate the refined list of capabilities. This ensured that all relevant dimensions were included in the list and nothing was overlooked.

Previous studies applying Robeyns’ criteria to identify a valid list of capabilities have used a combination of brainstorming, literature review, and examination of existing lists to construct an “ideal” list as a starting point (Biggeri et al. Citation2006; Mitra et al. Citation2013; Robeyns Citation2003; Tommaso Citation2006). After establishing this ideal or universal list, scholars have taken diverse approaches in the subsequent steps. Some validated the ideal list employing various methods, including referencing other capability lists (Robeyns Citation2003), employing a survey-based participatory approach (Biggeri et al. Citation2006), or engaging with relevant academicians for secondary data analysis (Tommaso Citation2006). Others developed an empirical list through iterative discussions within the research team, taking into account data constraints (Mitra et al. Citation2013). In our study, the first step was undertaken by Yousefzadeh et al. (Citation2019). They conducted a literature review and then organised an expert workshop to develop an ideal or universal capability matrix for child growth. We then continued this process by engaging in a brainstorming exercise with experts to identify a preliminary contextualised list of child growth capabilities for haor in Bangladesh. Therefore, this process aligns with previous capability studies, using brainstorming and desk-based reviews to identify capabilities at an ideal or universal level before proceeding to further contextualisation or analysis. Our unique contribution to the identification of a capability list lies in the fact that the contextualised list was co-created with the communities.

The process of co-creation of knowledge with the communities was built on both doxastic and epistemic interview techniques. A doxastic interview focuses on the interviewee’s experience, attitudes, and understanding of the context; whereas an epistemic interview encourages the interviewee and interviewer to challenge one another to better understand the underlying assumptions of what has been said, to bring in other perspectives, or to take the conversation to a higher level of knowledge (Berner-Rodoreda et al. Citation2020; Brinkmann Citation2007; Curato Citation2012). In the first round of community data collection, we mainly conducted asymmetrical one-way discussions – these were the doxastic interviews (Berner-Rodoreda et al. Citation2020; Kvale Citation2006). In other words, to capture emic perspectives on healthy child growth, we asked the community members questions and listened to their responses to better understand their world views, experiences, attitudes, and stories. This approach enabled us to create a draft contextualised list of capabilities built on emic perspectives. In the second round, discussions with the communities shifted to a dialogue format, involving two-way interactions – these were the epistemic interviews. We co-constructed knowledge by interpreting, confirming, and elaborating the draft list of capabilities based on the new insights (Brinkmann Citation2007; Berner-Rodoreda et al. Citation2020; Curato Citation2012). Thus, we verified the list of capabilities generated in the first round using an epistemic approach, concurrently gathering additional emic insights. This process of co-creating knowledge helped us fulfil Robeyns’ criteria of explicit formulation, exhaustion, and nonreduction.

The doxastic interviews in the first round generated stories that were instrumental in creating the draft contextualised list and identifying interconnected capabilities (such as a mother’s capability to stay away from violence and a mother’s capability to express love to her child). The epistemic interviews in the second round played a crucial role in elaborating and refining the draft list. We identified several new capabilities that had been missed in the first round, but that have significant public health implications in the process of achieving child growth, such as a mother’s capability to space child births. Furthermore, this round enhanced our understanding of the meanings attached to the capabilities in relation to healthy child growth. This finding emphasises the essential role of a validation round in creating a contextualised list of capabilities. Although the first round of data collection gave an initial understanding of contextual capabilities for healthy child growth in haor (Chakraborty et al. Citation2020), it did not meet the criterion of exhaustion and nonreduction and did not validate the findings with the affected communities. The validation round addressed these limitations, ensuring all important dimensions were included on the list. Earlier studies have also employed a participatory approach involving affected communities, and have also followed an iterative process to identify and validate a list of capabilities, through a variety of participatory research tools (Al-Janabi, Flynn, and Coast Citation2012; Anich et al. Citation2011; Biggeri et al. Citation2006; Kellock Citation2020; Kellock and Lawthom Citation2011; Yap and Yu Citation2016). Our work adds to the literature by reflecting on how to integrate doxastic and epistemic interviewing methods in generating a list of capabilities for child growth in vulnerable settings like haor.

In this reflection, we have demonstrated how meaningful community participation is key to the process of identifying and co-constructing a list of capabilities that people will value as a means to achieving wellbeing outcomes (Martinez-Vargas et al. Citation2022). However, this process of co-creation of knowledge is often challenging due to power structures and the privileged positionality of researchers (Martinez-Vargas et al. Citation2022; Walker et al. Citation2022). Indeed, potential power issues arose in this study, as the researcher came from a well-off background and did not belong to a haor community. Selecting culturally appropriate dress and conveying positivity and interest were essential for establishing a connection with the communities. In this regard, the epistemic round served a dual purpose: it was necessary for validation and also instrumental in mitigating power issues. In this round, the researcher assumed a more distant role, functioning as a facilitator, while the participants took on the role of story tellers and co-researchers, with the support of the visual tools used by the researcher to convey the findings from the first round. During this phase, communication became more equal, enabling participants to express their agreements or disagreements while elaborating and refining the draft list of capabilities for child growth. This approach aligns with Sen’s criteria of selecting capabilities through social discussions and public reasoning (Sen Citation2004; Citation2005).

In conclusion, this paper has enriched the understanding of “operationalising the capability approach”, by demonstrating and reflecting on a stepwise methodology that was followed to develop a list of capabilities at both a universal and contextual level. Our work sheds light on how the concept of capabilities can be translated to communities, and vice versa, by combining doxastic and epistemic interviewing methods. We illustrated how the epistemic round in particular contributes to Robeyns’ criteria, offering guidance for others to adopt a similar strategy. This approach enhances methodological rigour, minimises epistemological biases, and reduces power issues. It facilitates the co-creation of knowledge between participants and researchers in the development of a valid list of capabilities. The insights derived from our participatory research on child growth hold relevance beyond this specific domain, and can serve as a catalyst for further discussions among capability scholars on operationalising the concept of capabilities in various other dimensions of wellbeing.

Supplementary material_25Jan 2021.docx

Download MS Word (124.7 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Barnali Chakraborty

Barnali Chakraborty is an assistant professor at the Public Health Department of North South University (NSU) in Dhaka, Bangladesh. She started her career at icddr,b (International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh) and worked for many years at the Research and Evaluation Division of BRAC and at the BRAC James P. Grant School of Public Health, BRAC University, Bangladesh. She received her PhD from the Groningen University of the Netherlands, her MSc in Food and Nutrition from the University of Dhaka, Bangladesh, and her MPH from the Royal Tropical Institute in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Her research areas include multidimensional child growth, capability approach, maternal and child nutrition that connect multidimensional aspects. She applies both qualitative and quantitative methods in her research to inform policy and practice.

Shrinivas Darak

Shrinivas Darak is a senior research fellow at Prayas (Health Group), a Pune non-government organization. He has received training in Medicine (bachelor, University of Pune, India, 2000), Anthropology (Master, University of Pune, India, 2002) and Demography (PhD, University of Groningen, Netherlands, 2013). He worked as an assistant professor at the University of Groningen (2013-2014) and an adjunct professor at Public Health Evidence South Asia, Manipal University, India (2015-2019) in addition to working with Prayas. His research includes quantitative and qualitative methods incorporating disciplinary perspectives from clinical epidemiology, Public Health, Anthropology and Demography.

Haisma Hinke

Hinke Haisma is director of the Population Research Centre at the Faculty of Spatial Sciences, University of Groningen since 2021. She holds a position as professor in Child Nutrition and Population Health. She has a background (MSc) in Human Nutrition from Wageningen University (1992), and a PhD in Medical Sciences from the University of Groningen (2004). She started her professional career at the IAEA in Vienna and worked at the Universidade Federal de Pelotas in Brazil (through WHO). Her work is interdisciplinary in its nature. She combines the biological and the social context of child nutrition and population health.

References

- Al-Janabi, Hareth, Terry N. Flynn, and Joanna Coast. 2012. “Development of a Self-Report Measure of Capability Wellbeing for Adults: The ICECAP-A of a Self-Report Measure of Capability Wellbeing for Adults: The ICECAP-A.” Quality of Life Research of Life Research 21 (1): 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9927-2.

- Alkire, Sabina. 2013. “Choosing Dimensions: The Capability Approach and Multidimensional Poverty.” In The Many Dimensions of Poverty, edited by Nanak Kakwani and Jacques Silber, 89–119. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230592407_6.

- Anich, Rudolf, Mario Biggeri, Renato Libanora, and Stefano Mariani. 2011. “Street Children in Kampala and NGOs’ Actions: Understanding Capabilities Deprivation and Expansion.” In Children and the Capability Approach, edited by Mario Biggeri, Jérôme Ballet, and Flavio Comim, 107–136. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230308374_5.

- Berner-Rodoreda, Astrid, Till Bärnighausen, Caitlin Kennedy, Svend Brinkmann, Malabika Sarker, Daniel Wikler, Nir Eyal, and Shannon A. McMahon. 2020. “From Doxastic to Epistemic: A Typology and Critique of Qualitative Interview Styles Doxastic to Epistemic: A Typology and Critique of Qualitative Interview Styles.” Qualitative Inquiry 26 (3–4): 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800418810724.

- BHWDB. 2012. “Master Plan of Haor Area.” Main Report Volume II. Dhaka, BD: Bangladesh Haor and Wetland Development Board (BHWDB), Ministry of Water Resources (MWR), Government Republic of Bangladesh (GoB) andCentre For Environmental and Geographic Information Services. https://dbhwd.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/dbhwd.portal.gov.bd/publications/298d5166_988c_4589_96cb_36e143deba4f/Haor%20Master%20Plan%20Volume%202.pdf.

- Biggeri, Mario, and Andrea Ferrannini. 2014. “Opportunity Gap Analysis: Procedures and Methods for Applying the Capability Approach in Development Initiatives Gap Analysis: Procedures and Methods for Applying the Capability Approach in Development Initiatives.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities of Human Development and Capabilities 15 (1): 60–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2013.837036.

- Biggeri, Mario, Renato Libanora, Stefano Mariani, and Leonardo Menchini. 2006. “Children Conceptualizing Their Capabilities: Results of a Survey Conducted During the First Children's World Congress on Child Labour * Conceptualizing their Capabilities: Results of a Survey Conducted During the First Children’s World Congress on Child Labour *.” Journal of Human Development of Human Development 7 (1): 59–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649880500501179.

- Bignante, Elisa. 2010. “The Use of Photo-Elicitation in Field Research Use of Photo-elicitation in Field Research. Exploring Maasai Representations and use of Natural resources.” EchoGéo (11). https://doi.org/10.4000/echogeo.11622.

- Black, Robert E., Cesar G. Victora, Susan P. Walker, Zulfiqar A. Bhutta, Parul Christian, Mercedes de Onis, Majid Ezzati, et al. 2013. “Maternal and Child Undernutrition and Overweight in low-Income and Middle-Income Countries and Child Undernutrition and Overweight in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries.” The Lancet 382 (9890): 427–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X.

- Brinkmann, Svend. 2007. “Varieties of Interviewing: Epistemic and Doxastic.” Tidsskrift for Kvalitativ Metodeudvikling 42:30–39.

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie, and Stephen J. Ceci. 1994. “Nature-Nuture Reconceptualized in Developmental Perspective: A Bioecological Model.Nuture Reconceptualized in Developmental Perspective: A Bioecological Model.” Psychological Review 101 (4): 568–586. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.101.4.568.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., and Pamela Morris. 2006. “The Bioecoloigical Model of Human Development.” In Theorectical Models of Human Development, edited by R.M. Lerner and W. Damon, 793–828. Handbook of Child Psychology. New York: Wiley.

- Burchardt, Tania, and Polly Vizard. 2007. “Developing a Capability List: Final Recommendations of the Equalities Review Steering Group on Measurement.” SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 1159352. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1159352.

- Burchardt, Tania, and Polly Vizard. 2009. Developing an Equality Measurement Framework: A List of Substantive Freedoms for Adults and Children’.

- Chakraborty, Barnali. 2022. “Saving the Future in the Swamp: A Capability Approach to Child Growth in Haor Areas of Bangladesh.” Thesis Fully Internal (DIV), [Groningen]: University of Groningen. https://doi.org/10.33612/diss.222295474.

- Chakraborty, Barnali, Shrinivas Darak, and Hinke Haisma. 2020. “Maternal and Child Survival in Haor Region in Bangladesh. An Analysis of Fathers’ Capabilities to Save the Future.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (16): 5781. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165781.

- Chakraborty, Barnali, Sepideh Yousefzadeh, Shrinivas Darak, and Hinke Haisma. 2020. ““We Struggle with the Earth Everyday”: Parents’ Perspectives on the Capabilities for Healthy Child Growth in Haor Region of Bangladesh.” BMC Public Health 20 (1): 140. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8196-9.

- Conradie, Ina. 2013. “Can Deliberate Efforts to Realise Aspirations Increase Capabilities? A South African Case Study.” Oxford Development Studies 41 (2): 189–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2013.790949.

- Conradie, Ina, and Ingrid Robeyns. 2013. “Aspirations and Human Development Interventions.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 14 (4): 559–580. https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2013.827637.

- Curato, Nicole. 2012. “Respondents as Interlocutors.” Qualitative Inquiry 18 (7): 571–582. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800412450154.

- Domínguez-Serrano, Mónica, Lucía del Moral-Espín, and Lina Gálvez Muñoz. 2019. “A Well-Being of their Own: Children’s Perspectives of Well-Being from the Capabilities Approach.” Childhood (copenhagen, Denmark) 26 (1): 22–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568218804872.

- Glaw, Xanthe, Kerry Inder, Ashley Kable, and Michael Hazelton. 2017. “Visual Methodologies in Qualitative Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16 (1): 160940691774821. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917748215.

- Greco, Giulia, Jolene Skordis-Worrall, Bryan Mkandawire, and Anne Mills. 2015. “What Is a Good Life? Selecting Capabilities to Assess Women’s Quality of Life in Rural Malawi.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 130:69–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.01.042.

- Grewal, Ini, Jane Lewis, Terry Flynn, Jackie Brown, John Bond, and Joanna Coast. 2006. “Developing Attributes for a Generic Quality of Life Measure for Older People: Preferences or Capabilities?” Social Science & Medicine 62 (8): 1891–1901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.023.

- Haisma, Hinke, Sepideh Yousefzadeh, and Pieter Boele Van Hensbroek. 2018. “Towards a Capability Approach to Child Growth: A Theoretical Framework.” Maternal & Child Nutrition 14 (2): e12534. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12534.

- Harper, Douglas. 2002. “Talking About Pictures: A Case for Photo Elicitation.” Visual Studies 17 (1): 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725860220137345.

- Hennink, Monique, Inge Hutter, and Ajay Bailey. 2011. Qualittaive Research Methods. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

- HKI, and JPGSPH. 2016. State of Food Security and Nutrition in Bangladesh: 2014. Dhaka, BD: HKI (Hellen keller International) and JPGSPH (James P Grant School of Public Health).

- Kellock, Anne. 2020. “Children’s Well-Being in the Primary School: A Capability Approach and Community Psychology Perspective.” Childhood (copenhagen, Denmark) 27 (2), 220–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568220902516.

- Kellock, Anne, and Rebecca Lawthom. 2011. “Sen’s Capability Approach: Children and Well-Being Explored Through the Use of Photography.” In Children and the Capability Approach, edited by Mario Biggeri, Jérôme Ballet, and Flavio Comim, 137–161. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230308374_6.

- Kvale, Steinar. 2006. “Dominance Through Interviews and Dialogues.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (3): 480–500. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800406286235.

- Martinez-Vargas, Carmen, Melanie Walker, F. Melis Cin, and Alejandra Boni. 2022. “A Capabilitarian Participatory Paradigm: Methods, Methodologies and Cosmological Issues and Possibilities.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 23 (1): 8–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2021.2013173.

- Mitra, Sophie, Kris Jones, Brandon Vick, David Brown, Eileen McGinn, and Mary Jane Alexander. 2013. “Implementing a Multidimensional Poverty Measure Using Mixed Methods and a Participatory Framework.” Social Indicators Research 110 (3): 1061–1081. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9972-9.

- Mosley, W. Henry, and Lincoln C. Chen. 2003. “An Analytical Framework for the Study of Child Survival in Developing Countries. 1984.’ Bulletin of the World Health Organization 81 (2): 140–145.

- Nath, Samir Ranjan. 2013. Exploring the Marginalized: A Study in Some Selected Upazilas of Sylhet Division in Bangladesh. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Research and Evaluation Division, BRAC.

- Nussbaum, Martha Craven. 2000. “Women’s Capabilities and Social Justice.” https://doi.org/10.1080/713678045.

- Priest, Naomi, Tamara Mackean, Elise Davis, Lyn Briggs, and Elizabeth Waters. 2012. “Aboriginal Perspectives of Child Health and Wellbeing in an Urban Setting: Developing a Conceptual Framework.” Health Sociology Review 21 (2): 180–195. https://doi.org/10.5172/hesr.2012.21.2.180

- Robeyns, Ingrid. 2003. “Sen’s Capability Approach and Gender Inequality: Selecting Relevant Capabilities.” Feminist Economics 9 (2–3): 61–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354570022000078024.

- Robeyns, Ingrid. 2005. “Selecting Capabilities for Quality of Life Measurement.” Social Indicators Research 74 (1): 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-6524-1.

- Sen, Amartya. 2001. Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sen, Amartya. 2003. “Development as Capability Expansion.” In Readings in Human Development, edited by Sakiko Fukuda-Parr and A.K Shiva Kumar. New Delhi and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Sen, Amartya. 2004. “Capabilities, Lists, and Public Reason: Continuing the Conversation.” Feminist Economics 10 (3): 77–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354570042000315163.

- Sen, Amartya. 2005. “Human Rights and Capabilities.” Journal of Human Development 6 (2): 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649880500120491.

- Stewart, Christine P., Lora Iannotti, Kathryn G. Dewey, Kim F. Michaelsen, and Adelheid W. Onyango. 2013. “Contextualising Complementary Feeding in a Broader Framework for Stunting Prevention.” Maternal & Child Nutrition 9 (S2): 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12088.

- Stoecklin, Daniel, Ayuko Berchtold-Sedooka, and Jean-Michel Bonvin. 2023. “Children’s Participatory Capability in Organized Leisure: The Mediation of Transactional Horizons.” Societies 13 (2): 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13020033.

- Tommaso, Maria Laura Di. 2006. “Measuring the Well Being of Children Using a Capability Approach An Application to Indian Data.” wp05_06. CHILD Working Papers. CHILD Working Papers. CHILD - Centre for Household, Income, Labour and Demographic economics - ITALY. https://ideas.repec.org/p/wpc/wplist/wp05_06.html.

- UNICEF. 1990. A UNICEF Policy Review: Strategy for Improved Nutrition of Children and Women in Developing Countries. New York, USA: UNICEF.

- United Nations General Assembly. 1989. “Convention on the Rights of the Child Resolution.” https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/sites/default/files/un_convention_on_the_rights_of_the_child_1.pdf.

- Vizard, Polly, and Tania Burchardt. 2008. “Developing a Capability List for the Equality and Human Rights Commission: The Problem of Domain Selection and a Proposed Solution Combining Human Rights and Deliberative Consultation.” In . Portoroz, Slovenia: http://www.iariw.org.

- Walker, Melanie, Alejandra Boni, Carmen Martinez-Vargas, and Melis Cin. 2022. “An Epistemological Break: Redefining Participatory Research in Capabilitarian Scholarship.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 23 (1): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2022.2019987.

- Yap, Mandy, and Eunice Yu. 2016. “Operationalising the Capability Approach: Developing Culturally Relevant Indicators of Indigenous Wellbeing – an Australian Example.” Oxford Development Studies 44 (3): 315–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2016.1178223.

- Yousefzadeh, Sepideh, Mario Biggeri, Caterina Arciprete, and Hinke Haisma. 2019. “A Capability Approach to Child Growth.” Child Indicators Research 12 (2): 711–731. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9548-1.