Abstract

Older people seeking affordable housing in the mainstream housing tenures such as home ownership, private renting and social housing face increasing difficulties in accessing and remaining in appropriate housing. The mainstream housing tenures face pressure due to widening housing affordability problems in home ownership and the private rental sector in many advanced economies, exacerbated by declining investment in social housing. Hybrid housing models are often promoted as affordable and sometimes appropriate and adequate housing options for older people. These models combine aspects of ownership and renting in diverse ways, often posing challenges for tenure-based housing policies. Drawing on the case of Australia, the paper presents the findings of an institutional review of the production, consumption, management, and exchange of land lease communities, often marketed as a more affordable form of housing for older people compared to the more established hybrid form of retirement villages. Noting difficulties in scoping the size and significance of the land lease community sector from current data collections, we find (a) entry of large institutional investors risks undermining the relative affordability of the sector for older people; (b) security of occupancy is a critical policy issue and (c) concentration in rural areas raises concerns around risk of natural disasters and access to aged care and other services. These issues are often overlooked in housing policy and pose challenges for other policy domains including income support, social care, and health services.

Introduction

The world’s population is ageing, and the World Health Organisation (WHO) has projected that the proportion of older persons (aged 65 and above) will double, reaching 22% by 2050 (World Health Organisation, Citation2021). This paper stems from concerns about the extent to which current housing systems respond to the needs of an ageing population. In particular, this paper examines the role and growth of hybrid housing models for older people, notably those with low or moderate assets who are dependent on low incomes. These issues are explored using Australia as a case where population ageing is well recognised as a demographic change (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2021) and attention has been drawn to the implications for various aspects of public policy, including retirement incomes, aged care, and housing policies (Wood et al., Citation2017). The Australian case is introduced in the next section.

Housing policy in many countries revolves around long-standing concepts of housing tenure based on the distribution of property rights, notably the binary between owning and renting accommodation (Ruonavaara, Citation2012). There are further distinctions between housing forms: outright and mortgaged home ownership and private and social rental housing (Ruonavaara, Citation2012). There are a range of other housing arrangements in diverse countries which fall outside of these four tenure forms, recognised by the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) (Citation2019) as ‘other’: notably, cooperative housing and cohousing associated with the traditionally social democratic countries of Scandinavia (Larsen, Citation2019; Tummers, Citation2016). Recent international scholarship has also highlighted the growth of informal housing tenures in a range of economically advanced countries (see special issue of International Journal of Housing Policy in 2022, Volume 22(1)). Finally, in the search for more policy options to address growing concerns about housing affordability, there has been discussion of intermediate housing tenures (Elsinga, Citation2012), which potentially include low-cost home ownership, sub-market renting, and intermediate renting (where rents are above social rents but below private rents) (Whitehead & Yates, Citation2010).

Despite this growing appreciation of complexity in ‘other’ housing arrangements more generally, there is no clear term to indicate the conceptual underpinning of the range of housing models for older people, which are often seen as niche sectors. Concepts which have been deployed relevant to older people include ‘marginal housing’, ‘liminal housing’ and ‘non-permanent’ housing. These all carry generally pejorative connotations as ‘the other’. Marginal housing has been used in a variety of ways to refer to the sometimes-grey area between inadequate housing and homelessness, both of which may be defined in policy and for data collection. Marginal housing can denote the space where physical housing adequacy is problematic but deemed to be ‘reasonable to continue to occupy’ for determining eligibility for homelessness assistance, characterised in the English context as ‘a marginal space that is undefined, contingent and lacks transparency’ (Laurie, Citation2022, p. 81). Marginality has been further defined as explicitly referring to rental arrangements which differ from those found in private or social rental, viz. ‘highly managed or controlled housing, with fewer occupancy rights and some degree of shared facilities and spaces’ (Goodman et al., Citation2013, p. 2).

Another similar concept is liminality (Bevan, Citation2011; Schindler & Zale, Citation2021). Although used in diverse ways and different contexts, liminality derives from anthropology (Van Gennep, Citation1960), where it is used to describe a period of ‘ambiguity or disorientation’ (Schindler & Zale, Citation2021, p. 534) in which people are at a threshold between one life status and the next (Vähämaa, Citation2018, p. 165). Liminality thus implies a transitional status and as such overlaps with the concept of non-permanent housing—which can be found in housing policy but refers more specifically to dwelling type and tenure. Non-permanence may refer variously to the nature of the dwelling structure (e.g., a caravan, mobile home, or boat); type of legislation and other regulation; and the subjective assessments of security by residents themselves and the extent to which they may feel secure and ‘at home’ (Bevan, Citation2011).

This article contributes to this stream of scholarship by focusing on hybrid housing tenure models for older people. Hybrid housing tenure combines elements of owning and renting and may take different forms that are often overlooked by tenure-based housing policy, seen as ‘exceptional’ and often misclassified as rental forms (Feather, Citation2018, p. 597). Hybrid housing tenures (sometimes used interchangeably with intermediate housing tenures (Elsinga, Citation2012)) may enable households to access decent housing, typically if they have or can obtain sufficient capital for a deposit, and are of particular importance to older people. A key advantage of using this concept is that it lacks negative connotations, and does not assume that this is a stepping stone to home ownership at some stage. Hybrid housing models are not necessarily marginal, liminal, or non-permanent a priori; it is an empirical question whether specific institutional arrangements developed in different countries create these conditions, as we explore in this paper.

We focus on two hybrid housing models for older people: land lease communities (LLCs) and retirement villages. LLCs refer to arrangements where residents own their dwelling (in fewer cases, rent their dwelling) but rent a site where the dwelling is located. Confusingly, there are various terms used to describe LLCs in national and international academic and grey literature that appear to refer to a similar living arrangement. These terms include residential parks, manufactured home estates and manufactured home communities, caravan parks, ‘trailer’ parks, mobile home parks, and lifestyle communities. The Australian industry has promoted the term LLC to convey a more up-market product, moving further away from origins in manufactured homes, residential parks and caravan parks. This paper adopts the term ‘land lease communities’ as an umbrella term for investigating this hybrid tenure model. LLCs are generally privately owned and operated, and often marketed as a more affordable option for older people than the main alternative—retirement villages. Retirement villages provide independent living for older people and are an established hybrid model in Europe, the US, Australia, and New Zealand. Retirement villages typically offer age-appropriate accommodation, marketing safety, security, and a sense of community for older people (Evans, Citation2009). They may also offer some level of social services and care. International comparative research categorises retirement villages under the umbrella of Service Integrated Housing (Travers et al., Citation2022). We acknowledge that each of these countries/regions uses various terms to refer to this type of housing, and also have different level of services, regulations and policies. Thus, it is challenging to directly compare the regions, as argued by Howe et al. (Citation2013).

LLCs in Australia and elsewhere are of potential concern in view of recent growth and significant changes in their ownership and management. LLCs have attracted interest from large national and international institutional investors since the 2000s (Towart & Ruming, Citation2021), introducing new business models involving large institutional businesses entering the market, acquiring multiple sites, and upgrading the size and quality of dwellings at a higher price (Towart & Ruming, Citation2022). Noting the variations in site closures and redevelopment regulations across Australian jurisdictions, these are discussed later in the paper. The historical development of LLCs in Australia has some similarities with the US (Sullivan, Citation2014, Citation2017) and Canada (August, Citation2020), where urban redevelopment and gentrification have exerted pressure on LLC owners to either sell or redevelop their sites that were previously providing affordable housing for individuals with low incomes. In Australia, there is a growing trend where LLC models are specifically targeting older people who own family homes, including those looking to ‘downsize’ (Travers et al., Citation2022). This trend is likely to result in LLCs becoming increasingly unaffordable for low-income/asset older Australians (Towart & Ruming, Citation2020a). LLCs, however, are relatively overlooked in both academic discussions and housing policy in Australia whereas in the US, scholars have focused on LLC closures, evictions, and displacement (e.g., Sullivan, Citation2017) affecting socially disadvantaged people (e.g., MacTavish, Citation2007), their location and concentration in neighbourhoods (e.g., Pierce et al., Citation2018), land planning and zoning (e.g., Rumbach et al., CitationCitation2022), natural disasters (e.g., Rumbach et al., Citation2020), and financing (Kouhirostami et al., Citation2023). We acknowledge that LLCs have more importance in the US housing stock compared to Australia, representing the largest unsubsidised source of affordable housing in the US (Durst & Sullivan, Citation2019). LLCs in the US also have a wider range of tenures compared to Australia. For instance, around a quarter of LLC homes are renter-occupied, and more than half of LLC households in the US live on land they also own (see further details in Durst & Sullivan, Citation2019).

The article is structured as follows. First, we introduce the Australian case and locate LLCs and retirement villages within a typology of housing tenure forms for older people. This provides key context for examining the development and market segmentation of hybrid housing models. The paper then introduces materials and methods and provides an institutional review of LLCs and retirement villages. We conclude with identification of some key challenges for older people in the context of market changes, including concerns about ‘consolidation’ of ownership (Bevin, Citation2018, p. 219; Bunce & Reid, Citation2021) and acquisitions by institutional investors, also seen in the US (Sullivan, Citation2018).

The Australian case: where are hybrid housing models for older people located in the broader housing system?

The Australian housing system

In the Australian context, housing policies have historically been framed in terms of tenure, with priority for policies which encourage home ownership as a means of enabling security in older age. Home ownership is said to provide the fourth pillar of social insurance (protection) alongside a publicly provided means-tested age pension, mandatory private superannuation saving, and voluntary savings (Yates & Bradbury, Citation2010, p. 195). Extensive policy support for home ownership since World War II has resulted in older people in Australia having high outright ownership rates (AIHW, Citation2021); in 2021 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2021), 67.6% of people aged 65 years and over were outright homeowners. The 21st century housing affordability crisis in developed countries (Haffner & Hulse, Citation2021; Morris, Citation2021) has pushed back the age when people can achieve their first home ownership, such that more people are retiring with unredeemed mortgages, or renting (Wood et al., Citation2017), or have fallen out of home ownership due to life events (Wood et al., Citation2017). In consequence, the overall rate of home ownership among older Australians is decreasing and is expected to decline further (Daley et al., Citation2018).

Social rental housing has traditionally provided accommodation for older people who faced difficulties meeting housing costs, but the share of social rental housing in the Australian housing market, and annual number of new tenancies, is declining (Pawson et al., Citation2020). More older people are dependent on a private rental market that is increasingly unaffordable for older renters on fixed statutory incomes (Alidoust, Citation2022) and is often associated with insecure tenure (Hulse & Milligan, Citation2014).

Considering these trends, a growing proportion of older people is likely to be looking to other housing options, such as LLCs (Tually et al., Citation2022, p. vi). However, a recent review concludes that existing policies, legislation, and processes in Australia fail to support other housing options despite the increasing importance of these in filling the affordability gap in older age (Tually et al., Citation2022). Shared responsibility through multi-level governance in a federal system in Australia complicates the intersection between housing and other public policy domains in addressing these issues. Whilst the federal government has national powers over income support, retirement incomes, aged care, taxation and financial services regulation, the states are responsible for land management and consumer protection including regulation of residential tenancies, and other forms of accommodation (Martin et al., Citation2022). Thus, responsibility for housing policy is split between the federal government and states/territories with the former focusing on ‘affordability’ and the latter on housing supply and management including private and social rental as well as retirement villages and LLCs. This system results in some variation in policy and legislation between Australia’s six states and two territories.

Australian literature on typologies of housing options

There have been several attempts to develop detailed typologies of housing options for older Australians that extend beyond mainstream tenures (e.g., Bridge et al., Citation2011; Jones et al., Citation2007; Tually et al., Citation2022). Jones et al. (Citation2007, p. 8) distinguished 10 rental housing types, focussing on sector (public/private/community/family), physical form, age-specificity, provision of services, and communal amenities. For our purposes here, Jones et al. (Citation2007) distinguish between rental retirement complexes (retirement villages) and residential parks (LLCs). Bridge et al. (Citation2011, p. 8), in their literature review of age-specific housing provision for older people, include age-specific boarding/rooming houses and private hotels as well as designated community housing and assisted living rental villages. They distinguish between for-profit retirement villages, not-for-profit retirement villages, and LLCs what Bridge et al. (Citation2011, p. 8) refer to as mobile home communities (which they take to incorporate residential parks, caravan parks and manufactured home villages).

More recently, Tually et al. (Citation2022) reviewed ‘other’ housing options for precariously housed older Australians and distinguished between the options of cohousing, communal housing, mixed used apartment buildings, transportable homes, two-bedroom units, dual key properties and village style living. Recent work has focused on industry engagement and potential innovations (Towart, Citation2020) and industry engagement in the intersection of housing and ageing (Bevin, Citation2021). Other work has explored potential new options that support ageing-in-place, including LLCs and hybrid models (Hutchinson, Citation2019).

Our aim was to build on this knowledge to understand to what extent hybrid housing models for low-asset and/or low-income older Australians support independent ageing in the context of changing housing markets and broader economic, demographic, and social changes. illustrates a broad typology of current housing options for older people based on the relevant Australian literature.

Table 1. Typology of housing options for older Australians.

Overview of main hybrid housing models for older Australians: development and segmentation

Current issues around hybrid housing models are best understood in the context of their historical development, which has led to the market restructuring that is currently reshaping these options. This has implications for the future.

Retirement villages

The major current hybrid housing model for older people shown in is retirement villages. Retirement villages are officially defined as: ‘residential premises that provide accommodation primarily for persons who are at least 55 years old. The premises consist of self-care units, serviced units and/or hostel units and have communal facilities for use by occupants’ (Department of Social Services, Citation2023).

Australia’s not-for-profit sector has a long history of providing housing for older people dating back to the 19th Century. After World War II and until 1975, the federal government provided substantial capital funding to eligible not-for-profit organisations such as churches and charitable bodies to construct rental housing for older people of limited means (McNelis, Citation2004). From the mid-1970s, the not-for-profit sector led the development of housing for older Australians on a new ‘resident funded’ model (Kendig, Citation1987), recognising that some older people had significant equity in their homes and could ‘downsize’ to other accommodation, releasing some of that equity for capital contributions to retirement housing and leaving the rest for other expenditure. The ‘resident funded’ model attracted private sector interest, driving what Bevin (Citation2018, p. 219) refers to as a period of ‘experimentation and growth’ that included increasingly large and expensive dwellings, and a range of communal facilities.

In the 2000s, for-profit provision of retirement villages has dominated the sector (Hu et al., Citation2017; Travers et al., Citation2022), and currently, the sector estimates that nationally just around two thirds of retirement village units (66%) are operated by for-profit providers and a quarter by not for-profits (PwC/Property Council, Citation2022).Footnote1

Land lease communities

As homes in retirement villages on the ‘resident-funded’ model became increasingly expensive and unaffordable for older people with limited assets and income, lower cost forms of provision evolved, notably the LLC model (Towart & Ruming, Citation2022). LLCs originated from caravan parks, initially established to cater to short-term visitors (Towart & Ruming, Citation2022). However, changes in state government legislation eventually legalised permanent living in caravan parks in the mid-1980s (Towart & Ruming, Citation2021), prompting operators to adapt to this shift. Over time, caravan parks evolved in response to an increasing demand from low-income older people seeking long-term housing solutions. This transformation involved adapting the business model to incorporate year-round revenue streams for site owners/operators, moving away from the traditional seasonal focus (Towart & Ruming, Citation2022).

The LLC sector has responded to the significant shift since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008–2009 as institutional investors have looked to diversify their holdings to encompass previously neglected asset classes with relatively reliable capital growth and revenue potential (Caravan Industry Association of Australia, Citation2018).

Materials and methods

The approach taken in this research was an institutional review of LLCs by comparison with the more established retirement villages model. There are many definitions of institutions, encompassing those which are formally codified through legislation and regulation (including public policies) and those which are established through social norms and practices (Siddiki et al., Citation2022). Depending on discipline/approach, epistemology and objectives, a wide variety of methods of institutional analysis can be used (Payne, Citation2020; Scott, Citation2008). We draw on the structures of the housing provision approach originally developed by Ball (Citation1983) which provides a broader understanding of the wide variety of institutions and agents that co-constitute housing provision and its many forms. The structures of housing provision exist at a national level rather than an international level and cannot be deduced from theory, but must be identified through empirical research (Ball, Citation1983). The approach recognises that many changes in the structure of housing provision in a commodified context are not the consequences of government policy, but of shifts in the nature or roles of agencies within a process of provision and the subsequent reaction of others to those changes (Ball, Citation1998, p. 30). Such a frame enables investigation of not only public policies but also producers, consumers, and financiers of housing, who must be considered in identifying the structures of housing provision as well as the broader economic, social, and political environment in which they operate (Burke & Hulse, Citation2010).

Understanding the scale, scope, and institutional arrangements of hybrid housing forms for older Australians requires investigation of several disparate sources. This is not unexpected for LLCs but also, perhaps surprisingly, holds true for the more established form of retirement villages (see Hu et al., Citation2017 for a review of the Australian literature). To undertake a review, we draw on: academic works; a much larger body of industry literature; data compiled by peak industry bodies such as the Property Council of Australia, which conducts a survey of retirement villages every year; and national data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS).Footnote2 Each of these data sources has its limitations. There is a scarcity of academic research on Australian LLCs and retirement villages, not all states/territories require LLCs and retirement villages to be registered,Footnote3 industry data is geared towards marketing of LLC and retirement village options, peak bodies collect information in order to advocate for their sectors, and ABS data are quite limited. Notably, the most recent Census data was collected during a period when most states/territories implemented COVID-19-related restrictions and/or lockdowns (ABS, Citation2022).

Institutional review of hybrid housing models for older Australians

This section presents our institutional review of hybrid housing models for older people. Conceptualised as such, the housing system involves four components:

production (i.e., development and planning, owners/developers, and location);

exchange (i.e., financial arrangements, eligibility for rent assistance, and tenure);

consumption (i.e., amenities and services, demographic targets and aged care); and

management (i.e., legislation, tenure security, manager role).

Changes in these components occur in the context of the broader changes discussed above, such as: the current and projected ageing of the population; slowly declining home ownership rates among older people and reduction in government provision or funding of housing for older people; for-profit providers searching for alternative assets with revenue streams; and potential for capital uplift, particularly since the Global Financial Crisis.

The institutional review of the four key components for LLCs and retirement villages are summarised in .

Table 2. Summary institutional review of LLCs and retirement villages.

Production

In terms of development, LLC developments differ from retirement villages because LLCs are permitted on land with caravan park approvals, see . This means LLC developments can take place on sites that are not zoned for residential development, such as reserves and rural zones (Towart & Ruming, Citation2021), putting some areas at risk from floods (Towart, Citation2020). Different natural disasters, such as bushfires (Pierce et al., Citation2022) and floods (Rumbach et al., Citation2020), have been studied in the US in relation to LLCs; however, there is limited academic research of their impact in the Australian context. We know that in 2022, for example, South-East Queensland and Northern NSW were affected by floods, leading to the inundation of one major provider’s site in Lismore by floodwaters (Eureka Group Holdings Limited, Citation2022). Additionally, two resident-owned properties were affected in another major operator’s park during the 2019/2020 bushfires in Lake Conjola (Ingenia, Citation2020).

LLCs are financially appealing to investors due to their lower capital and ongoing investment costs by comparison to other forms of residential and tourist accommodations (Towart & Ruming, Citation2022). Lower costs are associated with owners/developers owning the site and infrastructure, but mostly, they are not responsible for dwellings which are owned by residents. Retirement villages, on the other hand, are considered residential real estate on land zoned as residential rather than as an aged care facility (see Hu et al., Citation2017). This means that retirement village providers must compete with other residential developers for site acquisition, a process that adds to the end costs for retirement village residents due to the for-profit model (Hu et al., Citation2017).

LLC properties were traditionally owned by individual property owners. However, in recent years, there has been a shift, with large institutional businesses investing in individual properties and creating securitised investments (Towart & Ruming, Citation2022). The major current LLC owners/developers in Australia are larger commercial companies: Ingenia Communities (Australian company), Aspen Group (Australian company), Equity Lifestyle Properties (US company), and Stockland (Australian company). Lendlease Group (global company) and Mirvac (Australian company) are entering the sector with new developments. Other larger chain operators include Palm Lake Resorts, GemLife, Living Gems, Serenitas, Lincoln Place, Next Living and Oak Tree. Additionally, there are numerous smaller operators that own 2–3 LLCs. The largest retirement village operators are the Aveo Group (global company) and Lendlease Group (global company founded in Australia), which rebranded as Keyton in 2023. Until recently, Stockland (listed under the LLCs above) was also a major operator but has sold its retirement villages businesses to EQT Infrastructure (health, aged care, and retirement living company) and is now focused on LLCs. LLC and retirement village operators do not receive any government funding (Simply Retirement, Citation2020).

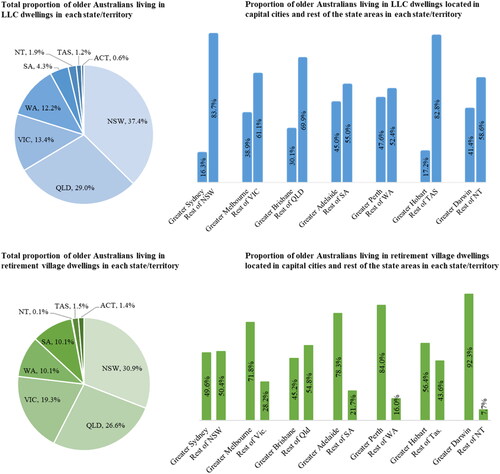

In terms of location, shows that majority of older people live in LLCs and retirement villages located in the ‘warmer climate’ states of NSW (37.4% and 30.9%, respectively) and Queensland (29.0% and 26.6%, respectively).

Figure 1. The proportion of older Australians (aged 65 years and over) in LLC and retirement villages in States/Territories (Source: ABS, Citation2021).

Exchange

Academic literature characterises LLCs as an affordable housing choice for older people due to their low initial costs and site rents by comparison with retirement villages and conventional housing (Towart & Ruming, Citation2021, Citation2022). The cost of some second-hand LLC dwellings starts from A$100,000 (Towart & Ruming, Citation2020b). However, grey literature indicates that not all LLCs are affordable. For instance, within communities offered by a major publicly listed LLC provider, average 2021 dwelling prices ranged from A$276,000 to A$660,000, with some units selling for up to A$900,000 (Ingenia Communities Group, Citation2021b). A different provider reported an average 2021–2022 price of A$606,000 (Stockland Corporation Limited & Stockland Trust Management Limited, Citation2022). By comparison, in December 2022, the mean price of residential dwellings in Australia was A$881,200 (ABS, Citation2023), noting that the mean prices vary in Australian states/territories, being highest in NSW (A$1,130,500) and lowest in NT (A$488,200) (ABS, Citation2023). Indeed, another major provider advertises that their LLC homes are typically priced at 75–80% of the median house prices in the local area (Lifestyle Communities Limited, Citation2022). This pricing model may make it less affordable for older people with low income/low assets, especially when considering that, in addition to the purchase price, LLC residents also need to cover weekly site fees. Moreover, residents do not own the land and are ineligible for traditional housing mortgage finance (Bunce & Reid, Citation2021). This means they need to sell their existing home, have sufficient funds to buy a relocatable home, or take out a personal loan, which typically has a higher interest rate than a housing loan.

Retirement village residents, by contrast, pay an entry fee or ‘ingoing contribution’, which may be refunded subject to an exit fee or ‘deferred management fee’ when leaving the village. In 2022, the national average price of a two-bedroom unit in a retirement village was A$516,000, which accounted for 52% of the median house price in the same area (PwC/Property Council, Citation2022). Thus, it appears that newly developed LLCs have higher initial unit purchase prices compared with retirement villages.

In terms of ongoing costs, LLC site rents vary, but one major provider charged a weekly site rent of A$212 for a single person and A$245 for a couple in 2023 (Lifestyle Communities Limited, Citation2022). Most LLC residents are eligible for Rent Assistance (RA)Footnote4 (Services Australia, Citation2023). LLC operators promote the ability to receive RA as a form of cash back. Regulation of LLC site rent increases varies between jurisdictions, with some states either having introduced, or proposed, legislation which restrict such increase to once a year and making the review method more transparent. In NSW, for example, rent increases can occur through a fixed method (fixed $ amount or calculation, e.g., in Consumer Price Index (CPI) or Age Pension) with specific intervals or by notice. There is no limitation on the frequency of intervals; however, if the increase is by notice, it needs to include an explanation and can occur once in 12 months (Residential (Land Lease) Communities Act, Citation2013). Victoria follows a similar pattern, allowing either a fixed method or notice, with all increases limited to once in 12 months (Residential Tenancies Act 1997, Part 4). In Queensland, increases are based on methods outlined in the site agreement, with options such as proportions from CPI or ‘market review’. Rents can increase once in 12 months, and special increases may be allowed for specific purposes (Manufactured Homes (Residential Parks) Act, Citation2003). In WA, rent can be increased by notice, with limitations on no more than once in 12 months (Residential Parks (Long-stay Tenants) Act 2006).

By comparison with site rents, as of September 2023, the standard rate of the Age Pension was A$1,097 per fortnight for a single person and A$1,653 per couple per fortnight (Services Australia, Citation2023) (equivalent to approx. A$550 per week for a single person and A$830 per week for a couple). LLC residents are normally exempt from stamp duty, rates, or registration fees (Burr, Citation2014). In most cases, residents of LLCs do not face exit fees or deferred management fees that are common in retirement villages. Additionally, they usually do not have body corporate fees, which are typically associated with strata-titled retirement villages (Burr, Citation2014). It’s worth noting that such villages are relatively few in number (Travers et al., Citation2022). However, the regulatory regimes in NSW and WA allow proprietors to take a share of dwelling sale proceeds under ‘voluntary sharing agreements,’ and Victoria allows LLC operators to charge ‘deferred management fees’ (e.g., Lifestyle Communities Limited, Citation2022).

Retirement village residents often also pay ongoing fees or ‘recurrent fees’ on a cost recovery basisFootnote5 while they reside in the village. Contracts stipulating residents’ and managers’ rights and obligations are often criticised as complex and confusing (e.g., Parliament of Victoria, Citation2017). Costs for residents tend to depend on the specific development and location (Hu et al., Citation2017). In most cases, retirement village residents are ineligible for RA. Only residents receiving the Age Pension or Disability Support Pension may be eligible for RA if their entry contribution does not exceed A$214,500 (Centrelink, Citation2021), highlighting some of the complexities for public policy of hybrid housing forms that do not fit neatly into traditional owning or rental categories.

Critiques surround both LLCs and retirement villages in the housing market, with challenges tied to relocating and valuing LLC dwellings, and the prolonged sale processes of retirement village units. LLC manufactured dwellings are often difficult and expensive to relocate and depreciate more (or appreciate less) compared with conventional real estate (Towart & Ruming, Citation2021) as in the US (Sullivan, Citation2017). Retirement villages have also faced criticism for the extended time between a resident’s exit and the entry of the next resident, as management fees may be applicable up until the sale (Travers et al., Citation2022). In 2022, for instance, the average time from vacant possession to settlement was 253 days (PwC/Property Council, Citation2022). Most Australian states/territories have implemented ‘buy-back’Footnote6 requirements ranging from six to 18 months for retirement villages. (Pearson, Citation2021).

Hybrid housing models are difficult to classify in terms of conventional housing tenure, see . In Australia, LLC residents typically own their dwelling and rent the site, while less commonly, they may rent both the dwelling and the site. By contrast, retirement villages offer various occupation arrangements, with leasehold and loan/licence arrangements being the most widespread, followed by freehold and rental tenures (Hu et al., Citation2017). The Census (ABS, Citation2021) indicates that the rate of outright ownership in LLCs (referring to the dwelling) was almost 68%, similar to the general population aged 65 and over, and greater than in retirement villages. This reflects the different contract and financial arrangements in retirement villages. Very few LLCs and retirement village residents have mortgages compared with the broader population of older Australians. The difficulties in categorising hybrid housing tenures are shown in the relatively high percentages of ‘other tenure’ types, blurring owning and renting where tenure type was not stated, and likely overstating ownership due to large ingoing contributions, whereas occupancy is on a lease or licence basis.

Table 3. Tenure type of individuals in LLCs and retirement villages, 2021.

Consumption

Traditionally, LLC homes have offered basic communal facilities, such as a laundry or a community room, see also . Up-market LLCs, however, have extensive resort-style communal facilities, such as clubhouses, cinemas, wellness centres, medical practitioners, beauty salons, bowling greens, and tennis courts (e.g., Ingenia Communities Group, Citation2021a). There appears to be increasing segmentation of provision for diverse groups of older people, although all tend to emphasise the role of community facilities in increasing interaction and enabling active living and a sense of community. Similar to LLCs, the facilities offered in retirement villages can vary widely. They range from affordable villages with basic services—such as a community house, barbecue area, and 24/7 emergency assistance—to upper-end resort-style villages boasting extensive amenities such as swimming pools, tennis courts, bowling greens, and cinemas (Bosman, Citation2012). There appears to be significant variation in the standard of services/amenities offered by for-profit and not-for-profit retirement villages (Parliament of Victoria, Citation2017). LLCs are often marketed to older people (Bunce & Reid, Citation2021), but they are usually not designed specifically for this demographic. While LLCs do not directly provide aged care services, it is important to note that some LLC operators may offer home care services under the federal government’s Aged Care Act, Citation1997. These services are separate from housing, and residents also have the option to access home care services through a provider of their choice. By contrast, facilities and services offered in retirement villages are specifically designed for older individuals and to bridge the gap between community care and residential aged care facilities (Riedy et al., Citation2017). In 2020, approximately 30% of retirement villages were co-located or closely located to residential aged care facilities (PwC/Property Council, Citation2021).

ABS (Citation2021a) Census data indicate that older residents in LLCs and retirement villages have contrasting socio-demographic and economic characteristics, see . LLC residents are more likely to be male and younger (65–74 years) compared with the retirement village cohort. The target market for retirement villages is over 70s, and the average age for someone entering a retirement village is 75 years across Australia, according to the industry (PwC/Property Council, Citation2022). Census data (ABS, Citation2021) reveal that almost two-thirds of retirement village residents are female, with 70% aged 75 years (compared to 55% of the general population in this age group). They have very low or low incomes, indicative of receipt of the Age Pension, noting that Census does not collect data on assets and wealth.

Table 4. Socio-demographic characteristics of older Australians in LLCs and retirement villages, 2021.

Management

The regulatory landscape governing LLCs and retirement villages in Australia varies among different states and territories, reflecting the diverse legal frameworks governing these two forms of housing. Five jurisdictions (NSW, NT, Qld, SA, and WA) have standalone legislation for LLCs. In Victoria and the ACT, the regulatory framework governing LLCs is primarily guided by their respective Residential Tenancies Acts. In Victoria, the Act contains a comprehensive set of provisions specific to moveable dwellings and site agreements. In the ACT, the Act incorporates generic ‘occupancy principles’ that are supplemented by provisions specific to ‘residential parks’. Tasmania has no legislation specific to LLCs. By comparison, retirement villages operate within more specific regulatory regimes. Each jurisdiction has its own Retirement Villages Act in addition to its broader Residential Tenancies Act. However, rules differ across jurisdictions with respect to relationships between managers and residents of retirement villages (Simply Retirement, Citation2020).

LLC residents’ tenure security varies by jurisdiction and may be affected by several factors, see also . First, grounds of termination are provided by legislation in every jurisdiction. LLC residents who own their dwellings in NSW, for example, have greater security compared with tenants in private rental as ‘no-grounds’ termination is not allowed. Second, residents’ security may be affected by LLC park closures, change of park type (e.g., to ‘tourist only’ parks), gentrification, and rent increases. In NSW, for example, operators can issue termination notices for park closure or change in site use, requiring a 12-month notice and evidence of prior development approval (Residential (Land Lease) Communities Act, Citation2013). In Victoria, termination for park closure is allowed with a 12-month notice period, but prior development approval is not required (Residential Tenancies Act 1997, part 4). In Queensland, termination requires tribunal approval (Manufactured Homes (Residential Parks) Act, Citation2003). Unlike in NSW and Queensland, in Victoria, termination at the grounds of the end of a fixed-term contract is allowed. WA mandates a 180-day notice for park or site closures, both necessitating prior development approval (Residential Parks (Long-stay Tenants) Act, Citation2006). Residents have compensation rights in all states. The nature and extent of permanent arrangements in LLCs are typically dependent on planning controls imposed by state/territory and local government authorities. Third, leases vary from month-to-month, yearly, and up to 99 years (Housing for the Aged Action Group [HAAG], Citationn.d.). Short term leases are associated with tenure insecurity, especially considering the conflict between private developers’ interest (profit) and public need for more affordable housing (Hulse & Milligan, Citation2014).

LLC residents are responsible for home maintenance when they own their home, but if they are renting, they are not responsible for home maintenance (Towart & Ruming, Citation2021). Upkeep and maintenance of community facilities, landscaping, and security (in up-market LLCs) is managed by the site operator. The effect of sector consolidation and entry of larger players on management is not known at this stage.

Similar to LLCs, retirement villages are managed by the owners, or an operator engaged by them (Hu et al., Citation2017). There is limited information to gauge the quality of management, echoing the situation in the private rental sector.

Discussion

This paper has investigated the role of key hybrid models in accommodating low-income/low-asset older Australians. Through an institutional review, we have begun to investigate the dimensions of LLC production, exchange, consumption, and management by comparison with retirement villages.

We note that the analysis is inevitably partial and patchy, as the LLC sector is fragmented and it is difficult to estimate the size and significance the sector plays in housing older Australians. It is particularly difficult to find authoritative and comparable information in relation to management, suitability for older people, conditions and quality of housing and built environment, financing, tenure security, and aged care. Much available information is supplied by government and industry, and accessible via websites designed for older Australians investigating their housing options. Industry literature offers additional relevant insight; however, the information provided may be skewed at times by the interest of owners/operators in marketing their products. Census data provide some basic information on people and dwellings in ‘caravan/residential parks or camping grounds’ and ‘manufactured home estates’ and ‘retirement villages’, noting its limitations (see Towart, Citation2022). Industry literature indicates that the actual number of LLCs is much higher than counted in the Census (Bunce & Reid, Citation2021). Partial understanding—especially underestimating the size of the sector—may lead to missed opportunities to address issues, such as corporatisation of the sector. Partial understanding poses further issues for policymakers, especially regarding effective resource allocation, policy formulation, developing accurate projections, and future planning. It is imperative to have better data on the LLC sector across Australia. More information is accessible regarding retirement villages, including the yearly PwC/Property Council’s retirement census, which compiles data from operators within the sector. It is important to note that participation in the census is voluntary, which may lead to certain segments of the sector not being captured and variations in data quality from year to year.

Three main themes are evident from our review of available information, which included academic literature, ABS Census data, and industry literature and data. Firstly, the increasing dominance of the for-profit sector, and some evidence of consolidation by larger institutional investors in the LLC sector, raise issues around redevelopment and gentrification that can lead to concerns with affordability and security, as observed in the US (Sullivan, Citation2017) and Canada (August, Citation2020). The entry and expansion of these companies point to increasing financialisaton of the LLC sector as owners seek to improve their asset via better facilities and attract a younger-old and a more affluent demographic, as well as downsizers. These developments presage increased vulnerability for lower-income older people who live in LLCs which may be redeveloped at a higher use value. Acknowledging variations in site closure/redevelopment regulations across jurisdictions as discussed earlier.

While some LLC dwellings, especially second-hand ones, remain at an affordable price point, it appears that newly developed LLC dwellings command higher initial unit purchase prices compared to the average price of a unit in retirement villages. Both forms, however, require reoccurring site and management fees. LLC owners/purchasers do not own the land in Australia and are thus ineligible for conventional mortgage loans (Bunce & Reid, Citation2021). These financing barriers may decrease the appeal of LLC homes to buyers, as observed in the US (Kouhirostami et al., Citation2023). It is worth noting that this concern might be less relevant in old age, particularly when older people have sold their previous homes to move to the LLC. To our knowledge, there is no Australian research that has examined this issue.

Secondly, several sources have indicated problematic ambiguity of ownership rights in hybrid housing models. For example, Sullivan (Citation2014) points to the association between ‘halfway ownership’ in the US and, in the case of LLCs, residents’ housing insecurity if park owners decide to re-develop or sell the land (see also Durst & Sullivan, Citation2019; Sullivan, Citation2017), as discussed earlier. Similarly, retirement villages have faced criticism for the complexity of their contracts, with residents noting a lack of sufficient assistance in understanding their legal and financial obligations (Travers et al., Citation2022). The coexistence of hybrid housing tenures, coupled with the ambiguity surrounding ownership within LLCs, and the complexity of main tenure types in retirement villages, poses a formidable challenge to effectively oversee and regulate the sectors.

Thirdly, most LLCs are in regional areas that may be located further away from infrastructure and services necessary for older people (e.g., specialist medical services) and be prone to natural disasters, such as bushfires or floods. The support and care requirements for older people may change over time, especially considering the finding that younger-old Australians (aged 65–74 years) tend to live in LLCs. Thus, access to locally available social care and health services may become an issue and older people may need to relocate to larger population centres, which would produce upheaval and costs of moving. LLCs are permitted on lands within caravan park zoning (rather than residential zoning), although NSW is proposing to amend its legislation on flood prone land (NSW Government, Citation2023). As discussed above, these lands may also be more affected by natural disasters, such as bushfires and floods. In the US, Pierce et al. (Citation2022) also found that LLC homes were more likely to be in areas with a history of bushfires or at risk of future ones, compared with all other housing types. This could potentially serve as a basis for further research, especially given frequent and severe bushfires in Australia. Planning policies should be reviewed to identify risk of environmental issues so that zoning reflects permanent residence and can protect residents from disasters.

Conclusion

Population ageing in Australia and other countries poses challenges for tenure-based housing policy, particularly where there are changing home ownership patterns, declining opportunities for appropriate social rental housing, a lightly regulated private rental housing market, and a deep and ongoing housing affordability crisis. Some of the available options for older people are hybrid tenure models driven by market players, including large institutional investors, as well as not-for-profit providers, with governments having a relatively minor role. Hybrid tenure models for older people are not transitional forms with a view to home ownership in the future. Nor are they necessarily marginal or temporary. Indeed, the concept of time for this age group may require new ways of thinking. We argue that a review of institutional arrangements—of production, exchange, consumption, and management—is essential to understanding both the benefits and risks for older residents of these hybrid tenures. It is imperative for housing policy makers to adopt a proactive stance and address these risks effectively and in a timely manner.

While there are some idiosyncrasies in the Australian case, it contributes to a broader understanding of how the projected further decline in home ownership rates in many western countries will affect ageing societies. This paper highlights the development of hybrid housing models for older people which combine features of owning and renting in potentially new ways. There are risks associated with meeting the health, wellbeing and affordable housing needs of an ageing population. These risks may arise if government policies and regulations lag behind market developments. Notably, the government challenges stem from the growing interest of institutional investors in the hybrid housing sector for older people, as discussed in this paper. This is a particular challenge for governments who have provided strong institutional support for home ownership and developed asset-based welfare systems in which older people are dependent on home ownership for low housing costs and increased security.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr Chris Martin’s, Prof Hal Pawson’s and Prof Bruce Judd’s contributions in shaping this paper, and Zoë Goodall for copyediting of this paper. We would also like to thank our two reviewers for their comments.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The data from PwC/Property Council reflects information collected from retirement village operators who voluntarily participated in the census.

2 ABS data analysis in this case focuses on individual older people rather than households, which is the unit of analysis in much housing research.

3 Two Australian states, NSW and Queensland, require LLCs and retirement villages to be registered, with accessible data provided on the respective government websites (for example, see Queensland Government, Citation2023). However, this information does not present a comprehensive picture of the entire country.

4 RA is a tax-free income supplement provided to individuals on government benefits (e.g., age pension) who rent from a private landlord (Services Australia, Citation2023).

5 Cost recovery entails the Australian Government charging the non-government sector some or all of the costs associated with a particular government activity (such as goods, services and/or regulations) (Commonwealth of Australia, Citation2021).

6 ‘Buy-back’ or exit entitlement refers to the situation where a retirement village operator repurchases a unit from a resident if the unit has not been sold within a certain time period (Pearson, Citation2021).

References

- Aged Care Act. (1997). https://www.legislation.gov.au/C2004A05206/latest/text

- Alidoust, S. (2022). Older people, house-sitting and ethics of care. International Journal of Housing Policy, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2022.2097853

- August, M. (2020). The financialization of Canadian multi-family rental housing: From trailer to tower. Journal of Urban Affairs, 42(7), 975–997. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2019.1705846

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2021). Tablebuilder: 2021Census - counting persons, place of enumeration (MB). https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/detailed-methodology-information/information-papers/comparing-place-enumeration-place-usual-residence

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2022). 4. COVID-19 and the 2021 census. ABS. https://www.abs.gov.au/census/about-census/census-statistical-independent-assurance-panel-report/4-covid-19-and-2021-census

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2023). Total value of dwellings (December 2022). https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/price-indexes-and-inflation/total-value-dwellings/latest-release

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2021). Older Australians. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/older-people/older-australians

- Ball, M. (1983). Housing policy and economic power: The political economy of owner occupation. (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203472613

- Ball, M. (1998). Housing provision and comparative research. In M. Ball, M. Harloe, & M. Martens (Eds.), Housing and social change in Europe and the USA (Chapter 1). Routledge.

- Bevan, M. (2011). Living in non-permanent accommodation in England: Liminal experiences of home. Housing Studies, 26(04), 541–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2011.559723

- Bevin, K. (2018). Shaping the housing Grey zone: An Australian retirement villages case study. Urban Policy and Research, 36(2), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2017.1369039

- Bevin, K. (2021). Making housing, shaping old age: Industry engagement in older persons housing. RMIT University https://researchrepository.rmit.edu.au/esploro/outputs/doctoral/Making-housing-shaping-old-age-industry/9921983911101341#file-0

- Bosman, C. (2012). Gerotopia: Risky housing for an ageing population. Housing, Theory and Society, 29(2), 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2011.641259

- Bridge, C., Davy, L., Judd, B., Flatau, P., Morris, A., & Phibbs, P. (2011). Age-specific housing and care for low to moderate income older people (No. 174). AHURI. https://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/174

- Bunce, D., & Reid, J. (2021). Retirement in residential parks in Australia: A smart move or move smart? Urban Policy and Research, 39(3), 276–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2021.1963224

- Burke, T., & Hulse, K. (2010). The institutional structure of housing and the sub-prime crisis: An Australian case study. Housing Studies, 25(6), 821–838. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2010.511161

- Burr, D. (2014). Home sweet manufactured home, CK Momentum 1, March 2014: CKMomentumIssue1March2014.pdf. wpengine.com

- Caravan Industry Association of Australia. (2018). Caravan Parks and MHEs: A vital aspect of affordable housing. https://www.caravanindustry.com.au/caravan-parks-and-mhes-a-vital-aspect-of-affordable-housing

- Centrelink. (2021). Centrelink 2021 rent assistance: Who can get it? https://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/individuals/services/centrelink/rent-assistance/who-can-get-it#a3

- Commonwealth of Australia. (2021). Australian government cost recovery policy. https://www.finance.gov.au/government/managing-commonwealth-resources/implementing-charging-framework-rmg-302/australian-government-cost-recovery-policy

- Daley, J., Coates, R., & Trent, W. (2018). Housing affordability: Re-imagining the Australian dream. Grattan Institute. https://grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/901-Housing-affordability.pdf

- Department of Social Services. (2023). Guides to social policy law: Social security guide. 1.1.R.270 Retirement village https://guides.dss.gov.au/social-security-guide/1/1/r/270

- Durst, N., & Sullivan, E. (2019). The contribution of manufactured housing to affordable housing in the United States: Assessing variation among manufactured housing tenures and community types. Housing Policy Debate, 29(6), 880–898. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2019.1605534

- Elsinga, M. (2012). Intermediate housing tenures. In International encyclopedia of housing and home (pp. 124–129). Elsevier.

- Eureka Group Holdings Limited. (2022). ASX announcement. Impact of flood event in South-East Queensland and Northern NSW. https://www.eurekagroupholdings.com.au/wp-content/uploads/Impact-of-Flood-Event-in-South-East-Qld-and-Northern-NSW.pdf

- Evans, S. (2009). An international perspective on retirement villages. In Community and ageing: Maintaining quality of life in housing with care settings (online ed.). Policy Press Scholarship. https://doi.org/10.1332/policypress/9781847420718.003.0005.

- Feather, C. (2018). Between homeownership and rental housing: Exploring the potential for hybrid tenure solutions. International Journal of Housing Policy, 18(4), 595–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2018.1520543

- Goodman, R., Nelson, A., Dalton, T., Cigdem, M., Gabriel, M., & Jacobs, K. (2013). The experience of marginal rental housing in Australia (No. 210). AHURI. https://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/210

- Haffner, M., & Hulse, K. (2021). A fresh look at contemporary perspectives on urban housing affordability. International Journal of Urban Sciences, 25(sup1), 59–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/12265934.2019.1687320

- Housing for the Aged Action Group (HAAG). (n.d.). Residential parks and villages. https://www.oldertenants.org.au/residential-parks-and-villages

- Howe, A.L., Jones, A.E., & Tilse, C. (2013). What’s in a name? Similarities and differences in international terms and meanings for older peoples’ housing with services. Ageing and Society, 33(4), 547–578. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X12000086

- Hu, X., Xia, B., Skitmore, M., Buys, L., & Zuo, J. (2017). Retirement villages in Australia: A literature review. Pacific Rim Property Research Journal, 23(1), 101–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/14445921.2017.1298949

- Hulse, K., & Milligan, V. (2014). Secure occupancy: A new framework for analysing security in rental housing. Housing Studies, 29(5), 638–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2013.873116

- Hutchinson, M. (2019). Housing for an ageing in Australia: what next? [PhD dissertation]. Queensland University of Technology.

- Ingenia. (2020). ASX/Media release update on bush fire activity and FY20 guidance. https://www.ingeniacommunities.com.au/wp-content/uploads/austocks/ina/2020_01_07_INA_59ec355a79c2b5566cbce1e97f1e5465.pdf

- Ingenia Communities Group. (2021a). Ingenia annual report 2021. https://onlinereports.irmau.com/2021/INA/

- Ingenia Communities Group. (2021b). Ingenia connect. https://www.ingeniacommunities.com.au/ingenia-connect/

- Jones, A., Bell, M., Tilse, C., & Earl, G. (2007). Rental housing provision for lower-income older Australians (No. 98). AHURI. https://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/98

- Kendig, H. (1987). Privatization of homes for the aged: The resident funded housing industry. Urban Policy and Research, 5(1), 37–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111148708551285

- Kouhirostami, M., Chini, A.R., & Sam, M. (2023). Investigation of current industry strategies to reduce the cost of financing a manufactured home. Journal of Architectural Engineering, 29(3), 03123002. https://doi.org/10.1061/JAEIED.AEENG-1510

- Larsen, H.G. (2019). Three phases of Danish cohousing: Tenure and the development of an alternative housing form. Housing Studies, 34(8), 1349–1371. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1569599

- Laurie, E. (2022). Marginally housed or marginally homeless? International Journal of Law in Context, 18(1), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744552322000040

- Lifestyle Communities Limited. (2022). Results Presentation for the year ended. https://assets.lifestylecommunities.com.au/prod-v2/Lifestyle-Corporate/Announcements/Full-Year-Results-Presentation.pdf

- MacTavish, K.A. (2007). The wrong side of the tracks: Social inequality and mobile home park residence. Community Development, 38(1), 74–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330709490186

- Manufactured Homes (Residential Parks) Act. (2003). (QLD) https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/pdf/inforce/current/act-2003-074

- McNelis, S. (2004). Independent living units: The forgotten social housing sector (No. 53). AHURI. https://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/53.

- Martin, C., Hulse, K., Ghasri, M., Ralston, L., Crommelin, L., Goodall, Z., Parkinson, S., & Webb, E. (2022). Regulation of residential tenancies and impacts on investment (No. 391). AHURI. https://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/391

- Morris, A. (2021). An impossible task? Neoliberalism, the financialisation of housing and the City of Sydney’s endeavours to address its housing affordability crisis. International Journal of Housing Policy, 21(1), 23–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2019.1688634

- NSW Government. (2023). Planning law changes for new caravan parks and manufactured home estates. https://www.planning.nsw.gov.au/news/planning-law-changes-new-caravan-parks-and-manufactured-home-estates

- OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development). (2019). OECD affordable housing database, HM1.3 housing tenures. https://www.oecd.org/els/family/HM1-3-Housing-tenures.pdf.

- OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development). (2021). Health at a glance 2021. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/ae3016b9-en

- Parliament of Victoria. (2017). Inquiry into the retirement housing sector. https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/432-lsic-lc/inquiry-into-the-retirement-housing-sector

- Pawson, H., Milligan, V., & Yates, J. (2020). Housing policy in Australia. Springer.

- Payne, S. (2020). Advancing understandings of housing supply constraints: Housing market recovery and institutional transitions in British speculative housebuilding. Housing Studies, 35(2), 266–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1598549

- Pearson, V. (2021). Retirement village dwelling buyback schemes: What you need to know. https://www.downsizing.com.au/news/992/retirement-village-dwelling-buyback-schemes-what-you-need-to-know

- Pierce, G., Gabbe, C.J., & Gonzalez S.R. (2018). Improperly-zoned, spatially-marginalized, and poorly-served? An analysis of mobile home parks in Los Angeles County. Land Use Policy, 76, 178–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.05.001

- Pierce, G., Gabbe, C.J., & Rosser, A. (2022). Households living in manufactured housing face outsized exposure to heat and wildfire hazards: Evidence from California. Natural Hazards Review, 23(3), 04022009. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000540

- PwC/Property Council. (2021). Retirement census. https://research.propertycouncil.com.au/data-room/retirement-living

- PwC/Property Council. (2022). Retirement census. https://www.propertycouncil.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/20230619-2022-Retirement-Census-Snapshot-Report_Online-Version.pdf

- Queensland Government. (2023). Residential parks with manufactured homes recorded with the department of housing. https://www.data.qld.gov.au/dataset/residential-parks-manufactured-homes-department-of-communities-housing-and-digital-economy

- Residential (Land Lease) Communities Act. (2013). No 97 (NSW). https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/act-2013-097

- Residential Parks (Long-stay Tenants) Act. (WA). (2006).

- Riedy, C., Wynne, L., McKenna, K., & Daly, M. (2017). Cohousing for seniors: Literature review. University of Technology Sydney.

- Rumbach, A., Sullivan, E., & Makarewicz, C. (2020). Mobile home parks and disasters: Understanding risk to the third housing type in the United States. Natural Hazards Review, 21(2), 05020001. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000357

- Rumbach, A., Sullivan, E., McMullen, S., & Makarewicz, C. (2022). You don’t need zoning to be exclusionary: Manufactured home parks, land-use regulations and housing segregation in the Houston metropolitan area. Land Use Policy, 123, 106422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106422

- Ruonavaara, H. (2012). Tenure as an institution. In S. Smith (Ed.), International encyclopaedia of housing and home (pp. 185–189). Elsevier Science and Technology.

- Schindler, S., & Zale, K. (2021). The harms of liminal housing tenure: Installment land contracts and tenancies in common. Journal of Affordable Housing & Community Development Law, 29, 523.

- Scott, W.R. (2008). Institutions and organizations: Ideas and interests. Sage Publications.

- Services Australia. (2023). Age pension. https://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/age-pension

- Siddiki, S., Heikkila, T., Weible, C.M., Pacheco-Vega, R., Carter, D., Curley, C., Deslatte, A., & Bennett, A. (2022). Institutional analysis with the institutional grammar. Policy Studies Journal, 50(2), 315–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12361

- Simply Retirement. (2020). Introduction to retirement villages in Australia. https://simplyretirement.com.au/retirement-villages-australia

- Stockland Corporation Limited and Stockland Trust Management Limited. (2022). FY22 results. https://www.stockland.com.au/∼/media/corporate/investor-centre/fy22/full-year-fy22/stockland-annual-report-30-june-2022.ashx?la=en

- Sullivan, E. (2014). Halfway homeowners: Eviction and forced relocation in a Florida manufactured home park. Law & Social Inquiry, 39(02), 474–497. https://doi.org/10.1111/lsi.12070

- Sullivan, E. (2017). Moving out: Mapping mobile home park closures to analyze spatial patterns of low-income residential displacement. City and Community, 16(3), 304–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12252

- Sullivan, E. (2018). Manufactured insecurity: Mobile home parks and Americans’ tenuous right to place. University of California Press.

- Towart, L. (2020). Supply and location drivers of Australian retirement communities [PhD dissertation]. Macquarie University. http://minerva.mq.edu.au:8080/vital/access/services/Download/mq:71580/SOURCE1

- Towart, L. (2022). Retirement living as recorded by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- Towart, L., & Ruming, K. (2020a). Retirement housing on wheels: Is it as affordable as it says in the marketing brochure? https://thefifthestate.com.au/innovation/residential-2/retirement-housing-on-wheels-is-it-as-affordable-as-it-says-in-the-marketing-brochure/

- Towart, L., & Ruming, K. (2020b). What are manufactured home estates and why are they so problematic for retirees? https://theconversation.com/what-are-manufactured-home-estates-and-why-are-they-so-problematic-for-retirees-145752

- Towart, L., & Ruming, K. (2021). Manufactured home estates as retirement living in Australia, identifying the key drivers. International Journal of Housing Policy, 23(3), 501–522. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2021.2007567

- Towart, L., & Ruming, K. (2022). Manufactured home estates as affordable retirement housing in Australia: Drivers, growth and spatial distribution. Australian Geographer, 53(2), 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2022.2072056

- Travers, M., Liu, E., Cook, P., Osborne, C., Jacobs, K., Aminpour, F., & Dwyer, Z. (2022). Business models, consumer experiences and regulation of retirement villages (No. 392). AHURI. https://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/392

- Tually, S., Coram, V., Faulkner, D., Barrie, H., Sharam, A., James, A., Lowies, B., Bevin, K., Webb, E., & Hodgson, H. (2022). Alternative housing models for precariously housed older Australians (No. 378). AHURI.

- Tummers, L. (2016). The re-emergence of self-managed co-housing in Europe: A critical review of co-housing research. Urban Studies, 53(10), 2023–2040. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015586696

- Van Gennep, A. (1960). The rites of passage. University of Chicago Press.

- Vähämaa, M. (2018). Challenges to groups as epistemic communities: Liminality of common sense and increasing variability of word meanings. Social Epistemology, 32(3), 164–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2018.1458352

- Whitehead, C., & Yates, J. (2010). Intermediate housing tenure – Principles and practice. In S. Monk & C. Whitehead (Eds.), Making housing more affordable: The role of intermediate tenures (Chapter 2, pp. 19–36). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Wood, G., Cigdem-Bayram, M., & Ong, R. (2017). Australian demographic trends and implications for housing assistance programs (No. 286). AHURI.

- World Health Organisation. (2021). Ageing and health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health

- Yates, J., & Bradbury, B. (2010). Home ownership as a (crumbling) fourth pillar of social insurance in Australia. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 25(2), 193–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-010-9187-4