ABSTRACT

Under what circumstances does human development facilitate or constrain emigration? Moreover, under what conditions is migration a driver for rather than an obstacle for development? Empirical evidence identifying the drivers of the two-way relationship between migration and development is still rather mixed, in part also because of conceptual and methodological shortcomings of the methods generally applied to this subject matter, which often cannot handle the complex links and interactions between migration and development. This paper engages with the opportunities and challenges of investigating the migration–development nexus using Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) as a methodological approach to explore the complex configurational two-way relationship between migration and development processes. We hereby address a methodological gap in the scientific literature investigating the migration-development nexus and propose QCA as a method for enriching the empirical base and expanding our knowledge and understanding of this complex relationship.

1. Introduction

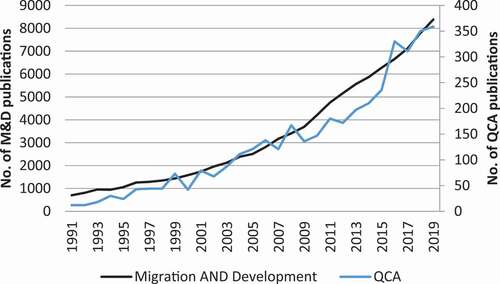

In recent years, the EU and its member states have reshaped various policies to focus more on migration-related issues. The triple mantra of ‘tackling the root causes’ of what is perceived as unwanted migration, attracting and selecting ‘the best and brightest’ on the global labour market, and ‘making migration work for development’ in countries of the so-called Global South reflects widespread political rhetoric. All three political objectives are conceptual elements of the two-way relationship between migration and development, or the so-called ‘migration-development nexus’ (Nyberg–Sørensen et al., Citation2002). Scholars have been intensively exploring this nexus for some time now in different spatial and temporal contexts using a range of empirical strategies and methodological tools. The number of research publications in this area has increased exponentially and it has become an established sub-field of migration studies and of social scientific research more generally (). Scholars and policy makers alike have embraced the idea that migration and development affect each other through various interdependencies and interaction mechanisms. Most research in this area is characterised by two overarching yet interlinked questions, namely ‘how does development affect migration?’, and ‘how does migration affect development?’. Attempts to manage functional connections between migration and development processes, such as tackling the ‘root causes’ of unwanted migration or the facilitation of ‘triple win situations for host and origin countries as well as migrants, are conceptually multifaceted and politically contested.

Figure 1. Number of scientific publications examining aspects of the migration-development nexus, and publications using QCA, 1990–2019.

Scientific evidence, however, is mixed and often not supportive of the above mentioned policy objectives and their underlying assumptions. For instance, ‘root cause policies’ for curbing the continuous movements of people mostly unwelcomed in European destinations are largely questioned by most scholars because of the oversimplified assumptions such policies are based upon and the unrealistic expectations they may trigger. The positive association between economic development and emigration for low- and middle-income countries is well documented (Clemens, Citation2014). However, as we all know, correlation is not causation. Several interacting drivers of migration are associated with human development, and the way they may collectively cause migration is still not exhaustively understood. For instance, demographic pressure, youth unemployment and lack of economic prospects, conflict prevalence and insecurity, lack of educational opportunities, environmental degradation and the existence of well-established migrant networks all play some role in migration, both independently and conjointly. Besides the analysis of migration drivers, the complex migration-development nexus includes a complex interaction between policy interventions including international aid provided to support development and to manage migration (Clemens & Postel, Citation2018). In fact, some evidence shows that poverty reduction as a primary objective of development aid may promote rather than impede out-migration by increasing household income (De Haas et al., Citation2019). Obviously, development policy agendas go beyond poverty reduction and include areas such as good governance, infrastructure, rural and urban development, and economic resilience. However, rather than being treated as development objectives per se, support initiatives in these areas are increasingly instrumentalised for migration management purposes.

At the same time, studies have provided evidence that international migration can be a driver for economic, social and even political development (Clemens, Citation2011; Spilimbergo, Citation2009). Correlates of migration such as financial, technological, and social remittances can reduce poverty, spur development and enhance democracy – yet only under certain circumstances and not in general. What these circumstances are is still unclear, and the further questions under what conditions certain aspects of human development may be driving or constraining emigration or under what conditions migration may be a driver or an obstacle for development require complex analytical approaches to be adequately addressed. The fact that empirical evidence is still rather mixed with regard to various aspects of the two-way relationship between migration and development is also due to methodological and conceptual shortcomings of some standard qualitative and quantitative methods applied to this subject matter.

This paper addresses the opportunities and challenges of investigating the migration–development nexus using Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) as an innovative methodological approach to explore the complex configurational two-way relationship between migration and development. We hereby aim to address a methodological gap in the scientific literature investigating the migration–development nexus and propose QCA as a method for enriching the empirical base and expanding our knowledge and understanding of this complex interrelationship. Evidence-based policy requires new and advanced research methods that can handle complex links and interactions between societal phenomena, such as those between migration and development. We present QCA as a methodological approach that can advance our understanding of the complex interlinkages. We then engage with some key features and good practices of implementing QCA as a method and discuss some recent developments and shortcomings of the method. Next, we review a growing but still very limited number of studies applying QCA to questions in the area of migration and development, then discuss and assess in detail two studies that are representative of implementing QCA at different analytical levels (i.e., at the micro and meso levels). This shall illustrate the usefulness and potential of QCA as a method of exploring complex multi-level and configurational aspects of the migration-development nexus. We conclude by emphasizing the need for triangulating QCA with other qualitative and quantitative research methods in order to generate ‘deep and wide’ evidence that can give more conclusive answers to some of the most pressing policy questions of our time. We argue that QCA can provide additional insight into the complex interlinkages between migration and development when it is meaningfully supplemented by other methods.

2. Configurational research and the migration-development nexus

Conceptual and policy-relevant questions on the interdependencies between migration and development address the role and relative importance of multiple factors (or drivers), such as poverty, environmental degradation, and armed conflicts that are generally considered key predisposing drivers of migration (Bijak & Czaika, Citation2020). A way to attempt sustainable policy-making for ‘managing’ (i.e., preventing) unwanted migration is to address its root causes. However, there is a persisting mismatch between the dominant scientific conclusions and the widespread belief in the capacity to manage migration by implementing specific policies addressing some ‘key drivers’ of migration. Migration and development are multi-layered processes with mutual interdependencies and feedback mechanisms that make the nexus between the two phenomena even more complex. Often ‘migration management’ means to address unwanted migration by implementing targeted, unidimensional, single-issue policies. However, multidimensional, multi-layered and interlinked processes such as those of migration and development are not sufficiently addressed by singling out particular driving factors for some targeted ‘treatment’. Migration and development outcomes alike are the result of configurational causations, which implies that many social, economic, political, cultural, institutional and other factors have to come together to produce a certain migration or development outcome. For instance, large-scale movements of refugees are driven by a number of factors, including violent conflict, but are often conjointly caused or reinforced by other phenomena, including economic decline or environmental stress, and are further enhanced by the migration-facilitating role of social networks, cultural norms or established migration infrastructures. However, while it may explain some refugee situations, such a configuration of driving factors certainly does not explain all forms of refugee situations, nor does it explain an ‘average’ refugee situation. Thus, a comprehensive, evidence-based understanding of the causal conditions triggering a multifaceted phenomenon such as refugee movements requires the acknowledgement of several alternative but equifinal explanations.

While most quantitative statistical methods are tools to estimate the ‘average’ effect of a causal factor, the underlying assumptions and implications are relatively strict with regard to the independence, linearity, and symmetry of causal effects. In other words, quantitative statistical research (e.g., regression analysis) does not allow for the possibility that a number of driving factors may not affect migration independently of other factors. For instance, a violent conflict does not necessarily trigger large-scale emigration but does so only if other factors are simultaneously present, such as established migration corridors or economic hardship experienced by wider parts of the population. Further, the empirical observation of a non-linear relationship whereby development can go hand in hand with more, but also with less, migration is hard by most quantitative research methods to handle. Asymmetric outcomes, such as low vs. high out-migration rates of regions or countries require separate and often complex (e.g., non-linear) explanations. For instance, emigration propensity levels cannot simply be explained by the intensity (i.e., higher or lower ‘dose’) of a certain driving factor, whether it be conflict, demographic pressure, environmental stress, or economic hardship or any other factor. Social scientific phenomena such as migration or development and their functional relationship are outcomes of causal configurations of multiple factors. The migration and development literature has thoroughly addressed these factors, though mostly only separately – that is, in an additive way – rather than conjointly in a multiplicative way, which requires methods that can handle complex configurations of causal factors.

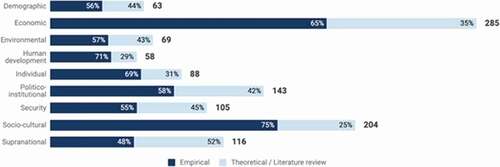

A recent review and synthesis of the vast literature on migration drivers has identified a range of explanatory factors that may affect migration processes in one way or another (Czaika & Reinprecht, Citation2020). displays the share and distribution of more than 460 empirical and non-empirical studies by driver dimension. Economic and socio-cultural drivers outnumber the other driver dimensions, whereas environmental drivers have received comparatively little attention. While this might reflect a biased selection of the literature, we believe that this extensive pool of studies is broadly representative of the literature on migration drivers.

Figure 2. Empirical and non-empirical studies by migration driver dimension (N = 463).

Most empirical studies investigate more than one driver. However, hardly any of these studies have explored in detail more complex interactions of migration drivers in detail, implicitly suggesting that migration drivers operate independently, additively, and linearly rather than configurationally, asymmetrically, and in non-linear ways. The reason for this conceptual and methodological bias is that some of the standard (quantitative) research methods either cannot handle more complex configurational explanations and causations or have only limited capacity to extrapolate beyond thick descriptions (Geertz, Citation1973) of a limited number of cases.

Until recently, configurational research methods and methodologies have hardly been applied at all to the field of migration and development although they have gained prominence in other fields of social scientific research. Since Rihoux and Ragin’s book Configurational comparative methods (Rihoux & Ragin, Citation2008), the application of QCA to complex, multi-layered social, political, and economic phenomena has grown swiftly. The rapidly increasing number of studies using the configurational method () also reflects this growing interest in QCA as a promising methodological approach for studying multi-causal phenomena.

Despite the increase in scientific publications focusing either thematically on the interlinkages between migration and development or methodologically QCA as a new approach for understanding complex causal configurations, both areas are still very much disconnected, in the sense that only very few studies in the area of migration and development so far have used QCA as methodological approach.

However, the stakes are clear: QCA as a methodology allows a refined understanding of the migration–development nexus, i.e., the multi-level determination of migration processes and their impact on development. Sweeping assumptions about certain drivers of migration – conflict, environmental change, poverty – often obscure the real dynamics that turn specific developments and events into differentiated migration outcomes. QCA is able to explore how alternative configurations of factors shape migration processes and outcomes.

Many, if not most, studies analysing drivers of migration have traditionally focused on either a single determinant or a few statistically independent determinants. QCA not only is capable of identifying, but in fact is designed to explore multi-causal relationships and to identify complex combinations of, for instance, interdependent migration and non-migration policy and non-policy factors that may in combination shape migration processes. Conversely, QCA makes it possible to disentangle the way migration influences development outcomes in combination with other socio-economic or institutional factors.

At the heart of a configurational analysis of the migration-development nexus are two overarching questions that specify the even more generic questions whether development drives migration or vice versa, namely:

how do causal conditions and configurations of specific drivers (including policy changes) affect migration dynamics, and

how do migration dynamics and transnational practices shape development outcomes?

QCA addresses such questions by identifying relevant configurations of necessary and sufficient conditions that are decisive elements of the empirical evidence. The search for necessary and sufficient conditions is the core of any QCA (see Schneider & Wagemann, Citation2012: 56–90). For instance, a collapse of livelihoods might produce significant out-migration in some configurations but not in others. Moreover, whether a given set of policy interventions enhances the development benefits of migration is likely to depend on other contextual factors that may be necessary or sufficient for positive development outcomes.

As such, QCA-based analyses on the drivers of migration may address research questions of the following type:

1. What causal factors are required for migration to occur? This question asks for necessary conditions, i.e., whether there are any factors that are absolutely or normally necessary for migration to occur.

2. What causal factors ‘guarantee’ or dramatically increase (solely or in combination) the occurrence of migration? This question asks for sufficient conditions, i.e., whether any of the factors under consideration are sufficient for migration to occur, even if these factors are not necessary for migration.

3. What causal factors make a difference regarding whether migration occurs, and under what circumstances? This question asks for so-called INUS conditions, i.e. whether any factors, alone or in combination, enhance the chances of migration occurring even if these factors are not required per se.

In the following, we describe the main features of the QCA methodology and its implementation in order to address such research questions. Over the past three decades, Ragin (Citation2000, Citation2008) and others (for instance, Rihoux & Ragin, Citation2008; Schneider & Wagemann, Citation2012) have rapidly developed QCA as a configurational research approach and a method of analysis. Distinctively, QCA seeks to identify causal explanations through a systematic comparison of the presence or absence of specific conditions in a set of cases (cf. Ragin, Citation1987; Ragin, Citation2006), exploring causal connections between a theoretically informed set of causal conditions and an outcome.

The unique feature and main contribution of QCA compared to other quantitative or qualitative research methods is that it answers the question whether factor X (‘the cause’) satisfies various notions of necessity and sufficiency for causality, where the cause may be a policy intervention or another contextual or historical factor. QCA determines whether a certain condition is required (‘necessary’) to achieve an outcome, or whether the outcome can be achieved without this condition. It also determines whether a certain condition is good enough (‘sufficient’) to produce the outcome or requires other factors to be effective.

Necessary and sufficient conditions

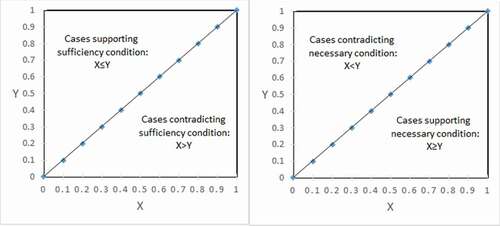

As a set-theoretic approach, QCA applies a very specific perspective on relationships between social phenomena. This perspective is characterised by three fundamental features (cf. Schneider & Wagemann, Citation2012). First, observations of analytical units (‘cases’) are defined by their degree of membership (‘score’) in a particular set. That is each case in a sample of individuals, households, communities, firms, regions or countries is characterised by a certain degree of set membership. For instance, if cases are defined as regions, the sample may contain cases (regions) with a high membership score, which belong to the set of high emigration regions, as well as cases with a low membership score (low emigration regions). Second, associations between indicators of migration and development are defined as set relations. Third, these set relations are interpreted in terms of sufficiency and necessity. For instance, development factor X is a sufficient condition for migration outcome Y to occur only if condition X is a subset of a (larger) set Y (, left-side). That is, sufficiency requires that if we observe civil war (X), then we also observe high out-migration (Y). That implies that in order to observe high out-migration, it is sufficient that peace turns into war. Obviously, war may not be the only sufficient condition for high out-migration as there may be other (configurations of) conditions that cause high out-migration. On the other hand, X can also be a necessary condition, i.e., a superset of an outcome set Y. In such a case, for instance, ‘high out-migration’ (Y), can be observed only when the necessary condition, say economic decline (X) is present (, rightside).

INUS conditions

Conditions can be neither necessary nor sufficient and yet be part of more complex configurations of so-called INUS conditions. An INUS condition is defined as an ‘insufficient but non-redundant part of an unnecessary but sufficient condition’ (Mackie,Citation1974). INUS conditions in themselves are neither sufficient nor necessary conditions for outcome Y to occur but function only as the insufficient (I) and non-redundant (N) parts of an unnecessary (U) but sufficient (S) condition for Y. For instance, any of the three elements of the following QCA solution

Civil conflict AND (i.e. in combination with) weak migration networks AND restrictive migration policies sufficiently cause low levels of out-migration

is neither sufficient nor necessary for low levels of out-migration to occur, but only in combination with the other conditions contributes as an ‘INUS’ condition.

QCA provides a case-oriented perspective that is fundamentally different from variable-oriented approaches such as in statistical methods. Cases are configurations of alternative sets in which they may have a certain degree of membership. For example, an individual case can be a full member, full non-member or partial member in the set of countries or regions with high out-migration. Sets are characterised by the ability to capture both quantitative degrees of partial membership and qualitative differences (i.e. differences in kind) between non-members and members of a set (Ragin, Citation2008; Schneider & Wagemann, Citation2012).

As a case-oriented approach, QCA requires a conceptualisation of cases (such as countries, regions, communities, firms, households, or even individuals) as combinations or configurations of characteristics that are suspected of causally influencing an outcome. QCA requires familiarity with the characteristics of the cases together with their outcomes. Given this familiarity, a systematic cross-case comparison identifies the factors that are consistently overlapping to a certain degree with an outcome (i.e., aspects of migration or development) and can potentially be considered causally responsible for the outcome’s occurrence.

Calibration

Conditions and outcomes are calibrated by defining the degree of set membership for all conditions and outcomes using raw data that describe condition and outcome characteristics of all cases. The two basic ways for calibrating raw data are dichotomous and continuous. In crisp-set QCA (csQCA), conditions and outcomes of cases are dichotomous and defined by the ‘presence’ or ‘absence’ (i.e. membership) of a given characteristic in a set of cases, corresponding to the membership or non-membership of these cases in the set of cases with that characteristic(see ). Crisp-set QCA hereby identifies the conditions that are needed or most effective for the outcome to occur (Befani, Citation2016). In fuzzy set QCA (fsQCA), cases can also have partial membership in the sets of conditions X and outcomes Y; fsQCA therefore allows for more information. Cases can be more outside than in a set, and vice versa. Fuzzy scores are calibrated between 0 (full non-membership) and 1 (full membership) to represent the degree of presence of a characteristic (Schneider & Wagemann, Citation2012). This implies that cases are characterised by their degree of membership in the condition set X and the outcome set Y respectively (see the X-Y plot in ).

Equifinality

Another core feature of QCA is its ability to handle and identify plural causation (‘equifinality’), i.e., a situation where the same outcome can be generated by more than one condition or configuration of conditions. For instance, high out-migration can be sufficiently caused by the following alternative ‘equifinal’ solutions:

1. Civil unrest AND an established migration network AND environmental degradation

2. Economic decline AND absence of political stability AND post-colonial ties to an attractive destination country

3. Low level of educational outcomes AND high unemployment among youth AND an established culture of migration

All three combinations are equifinal, i.e., all generate the same outcome (high out-migration), and all consist of three INUS conditions that are conjointly sufficient for high out-migration to occur. Thus, there can be three different configurations that tell very different stories regarding why out-migration occurs in some countries but not in others. Consequently, QCA results can be translated into more complex policy recommendations in the sense that the QCA solutions identify not only one but possibly a number of equifinal combinations of conditions that are necessary or sufficient for a given migratory or developmental, outcome of interest to occur.

Consistency and coverage

In QCA, consistency and coverage are measures commonly used to assess ‘goodness of fit’, i.e. to evaluate non-perfect subset relationships for both necessary and sufficient conditions (see Schneider & Wagemann, Citation2012: 119–150; Ragin, Citation2008). The consistency measure reflects the degree of merit to which empirical evidence supports the claim of a sufficient (set-theoretic) relationship and indicates how much it deviates from a perfect sufficient relationship. For instance, the consistency measure in the analysis of sufficient conditions for high out-migration to occur may indicate that civil conflict is not perfectly consistent, i.e., the outcome (high out-migration) is present in some but not all cases in which civil conflict is present. The coverage parameter, on the other hand, must be interpreted differently, depending on whether the condition is necessary or sufficient. With sufficient conditions, coverage is a measure of how ‘broad’ an explanation is, i.e. to what extent an outcome can be explained by an identified sufficient condition or configuration ofconditions. For instance, civil conflict may explain high out-migration only in some countries; other countries with high out-migration but without civil conflict require other explanations. In the case of necessary conditions, high coverage implies triviality because the condition is usually present when the outcome is present (see Schneider & Wagemann, Citation2012). The parameters of consistency and coverage thus provide valuable support for the evaluation of the set relations between migration and development at different stages of a QCA analysis.

4. QCA in migration and development studies

Since the early 2000s, QCA applications have expanded across various social scientific disciplines including sociology, political science and geography. The COMPASSSFootnote1 journal database, a major reference among scholars and practitioners engaged in the development and application of systematic cross-case analysis, and QCA in particular, tags only five journal articles as related to ‘migration’, and 38 as related to ‘development’Footnote2 out of 1376 references.

This COMPASSS journal database is, however, far from exhaustive, which indicates that more academics outside the QCA community have begun to develop an interest in this method. While there are a number of QCA-based studies in the fields of migration studies and development studies, there are still very few empirical applications of QCA aiming to explore the migration–development nexus. Generally, QCA applications have been used more extensively in the field of development studies than in migration studies.

QCA in migration studies

The fundamental appeal of QCA as a method are its comparative and configurational abilities. For instance, Hooijer and Picot (Citation2015) look at migrant poverty in the European context, justifying the use of the QCA method on the grounds that ‘there has been little comparative research so far on how immigrants fare in developed welfare states’ and pointing in particular to the ‘lack of systematically compared institutional determinants of migrant poverty across a larger set of countries’ (p. 1881). In the field of migration studies, QCA is commonly applied to the topic of the migration-welfare nexus (see Hooijer & Picot, Citation2015; Da Roit & Weicht, Citation2013). In the past few years, several migration scholars have used the QCA approach to compare and understand better the development of migration and asylum policies as well as integration/citizenship policies at the cross-national level. Guérin’s (Citation2018) research, for instance, seeks to identify the factors that drive some European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) states to align with European asylum policies when others do not. Walbott’s (Citation2014) study focuses on citizenship and immigration in Western Europe and examines at why some countries facilitate access to national membership for immigrants while others permanently rely on restrictive policies. Ebeturk and Cowart (Citation2017) contribution examines the causes of the criminalization of forced marriage in 29 European countries of which 20 have criminalised forced marriage.

Some studies adopt a meso-level approach, such as Dekker and Scholten's (Citation2017) study of the effects of media on Dutch immigration policies. That study examines configurations of both quantitative and qualitative aspects of media coverage associated with changes in the policy agenda. To do so, it compares the media coverage of 16 events associated with Dutch immigration policies (the unit of analysis) that took place between 2011 and 2015 and that have gained varying amounts of media attention in the Dutch media over the past years.

While QCA analyses are often applied in macro and meso-level studies, a few migration-related studies also apply QCA at the micro-level. One example is Seate et al.’s (Citation2015) research testing the intergroup contact theory. The authors aim to analyse how several communicative and psychological variables might be necessary and/or sufficient to produce positive intergroup attitudes towards ‘illegal’ immigrants within an imagined intergroup contact experience. The discussion emphasizes the implications for intergroup contact and the utility of fsQCA.

In the existing literature, the QCA approach in the field of migration studies mainly focuses on the European context and more specifically on European countries as the main unit of analysis. Topics centre predominantly on citizenship, migrants’ rights, welfare states and the conditions of policy diffusion affecting policies on migration, asylum, integration and citizenship. Finally, macro-analytical perspectives have been privileged, while micro-approaches are still rather rare. However, this is clearly a growing field of study, though still far from being widely established.Footnote3

QCA in development studies

A bibliometric analysis of the COMPASSS database in November 2020 (N = 1380) categorised in 38 references under the tag ‘development’. To include more references in our literature search, we included geographical tags (i.e., Africa, Latin America, Asia and the Middle East) as well as ‘conflict’ (24), ‘peace’ (6) and evaluation/development intervention (5) as additional markers. In total, we found 85 ‘development’Footnote4-related articles in the COMPASSS journal database.Footnote5

We noticed that many studies in this data collection adopt an international perspective, comparing countries apopcross continents (Global: 19),Footnote6 as well as within Asia (33), Africa (11), Latin America (18), Europe (73), North America (5) and the Middle East (4). Despite the fact that the majority of QCA studies (in the COMPASSS database) focuses on mainly members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (76),Footnote7 more and more studies have adopted a global perspective.

Although not fully exhaustive, the COMPASSS database reflects the main and current areas of investigation of QCA-based development research.

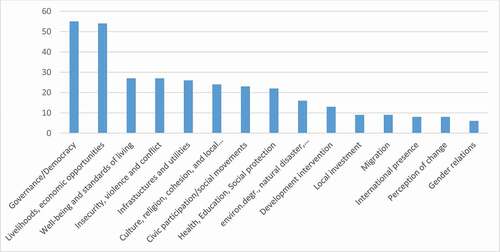

indicates that most studies focus primarily on the links between democracy, governance and development as well as on economic development. In the last decade, QCA as a method has also begun to find application in a range of new disciplines such as the fields of conflict and peace studies, international relations and international development studies.

Figure 5. Number of development-related QCA publications per theme in COMPASSS database (N = 85).Footnote8

Only a few studies touch explicitly upon the complex interaction between migration and development. However, some researchers in fields such as diaspora studies and international relations attempt to disentangle the also complex migration-conflict nexus. For instance, Hasić (Citation2018) investigates post-conflict co-operation in multi-ethnic local communities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, addressing the question of how the involvement of a diaspora in peacebuilding may complement intra-ethnic co-operation among elites in multi-ethnic municipalities. In another context, Rubenzer (Citation2008) specifically looks at the attributes of ethnic minority interest groups and these groups’ influence on U.S. foreign policy. In the field of peace and conflict studies, Ansorg’s (Citation2014) examines the conditions for the development of regional conflict systems in sub-Saharan Africa. Based on 12 cases studies in West Africa, in the Great Lakes and in the Horn of Africa, the author identifies four specific conditions that can lead to a regional spread of violence: economic networks sustained through the support of neighbouring countries, an intervention on the part of the government, militarized refugees, and non-salient regional identity groups. Among the set of hypotheses tested, one directly regards the existence of militarised refugees – that is, the present of combatants among refugees arriving in, neighbouring country – as a central condition for the regional spread of violence. Militarised refugees are identified as a potential driver for conflict that can lead to the diffusion of regional conflict and, to some extent, to further refugee movements.

More recently, a new range of studies are looking directly at the links between global environmental change and migration and relying on QCA as a way to tease apart interwoven drivers of environment-related migration (Haeffner et al., Citation2018; Groth et al., Citation2020). Examining the impact of climate change on rural communities, Haeffner et al. (Citation2018) investigate configurations of household characteristics (traits) in Baja California Sur, Mexico, and how they influence household adoption of four specific drought adaptation strategies: (1) environmental migration (direct), (2) household-member migration (indirect), (3) changing farm practices and (4) finding off-farm work. Adopting a mixed-method approach (integration co-occurrence analysis, QCA and in-depth interviews), the authors compare the knowledge gained through each method, noting that QCA better allows them to identify the key existing relationships between household traits and drought adaptation as well as why a given trait may influence such adoption. While, on the one hand, QCA provides a unique lens through which to study the variety of ways rural households adapt to climate change, on the other hand, it also reduces complex factors to binary variables. By using interviews, the authors attempt to mitigate the loss of information in the QCA analysis. In addition, by combining methods, the authors are able to identify a certain finding as the most consistent, namely that the more a household is able to access urban services (including piped water), the less likely it is to have used one of the drought adaptation strategies under study. Here, QCA plays a useful complementary role in the research design.

Similarly, Groth et al. (Citation2020) study at migration as an adaptive strategy in the northern Ethiopian Highlands in order to identify which contextual factors are the most relevant and how they interact in shaping environment-related migration. The authors use QCA, as a novel approach to the subject in order to provide a better understanding of migration beyond the classic ‘push-pull model’. Their findings reveal a ‘complex web of causal links’ (Mastrorillo et al., Citation2016, 155) in which networks and capabilities are the drivers of environment-related migration at the household level. Relying on the QCA methodology enables the authors to take into consideration meso-level migration drivers (e.g., agro-cultural characteristics) along side the micro-level drivers (such as household level) that are more commonly studied.

An area where QCA has been gaining ground is policy-impact evaluation – in particular, in the field of development co-operation (Pattyn et al., Citation2017), where it is used as an alternative method for evaluating policy change or advocacy interventions (Meuer et al., Citation2018). In a proposal called ‘Development on the Move’,Footnote9 a collaborative research project between the Institute for Public Policy Research and the Global Development Network, QCA is discussed as a method for conducting a cross-country analysis. The proposal notes the existence of few comparative works on migration and development, with most analysis taking place at the country, regional or village level. Accordingly, this project aims to explore the interaction between migration and development across countries by assessing the multiple economic and social impacts of migration. The focus is therefore on how migration dynamics and transnational practices shape development outcomes.

Overall, very few QCA articles directly address the migration–development nexus as such, instead, the majority of migration- and development-related studies focus on either migration or development as the outcome phenomenon to be explained. While migration and development clearly affect each other through various interaction and feedback mechanisms, very few studies have attempted to disentangle these complex causal relationships. However, a growing interest over the last few years is noticeable in the research community, indicating a growing and emerging field of study.

5. QCA in practice: a review of two case studies

This section examines two qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) case studies within the field of migration and development studies, conducted at the meso- and micro-levels, respectively. Qin and Liao (Citation2016) work forms part of this new corpus and examines migration-induced agricultural change in 20 areas in rural China. Their research aims to provide a more accurate understanding of the relationship between migration and agricultural development. Likewise, Taylor (Citation2015) investigates international mobility and migration as drivers of technological developments, specifically internet penetration in Ghana. For each of these studies, we evaluate how QCA is applied both as a research approach and as an analytical technique, in light of QCA standards of good practice (Schneider & Wagemann, Citation2010). Our aim in doing so is to highlight some of the strengths and shortcomings of the QCA methodology in understanding the migration–development nexus.

QCA at the meso-level: Migration and agricultural change (Qin & Liao, 2016)

The relationship between migration and agriculture is a key aspect of rural restructuring in China. To date, research on the topic has generated rather mixed findings on the effects of rural out-migration on agricultural change, with a proliferation of individual case studies, but no systematic comparative analysis.

Qin and Liao (Citation2016) present a meta-analysis of case studies using QCA. It is acknowledged in the broader literature that ‘the social and economic outcomes of migration in origin areas are highly contingent on local development contexts’ (De Haas, Citation2010; Durand & Massey, Citation1992, as cited in Qin & Liao, Citation2016: 534). For this reason, a case-oriented meta-analysis is particularly suitable for identifying why the impact of labour out-migration on agriculture is positive in some rural communities but negative in others. The primary purpose of the study was to identify general patterns of migration effects on agricultural production in rural China. The literature review on the Chinese context – as for the developing world – stressed the multiplicity of potential migration effects on agricultural change, indicating that the way that labour out-migration influences agriculture is conditioned by the socio-economic and environmental contexts of the areas from which the migrants come.

Qin and Liao (Citation2016) adopted QCA mainly to compare and synthesise the data available and to develop empirical generalisations. The dataset consists of cases referring to a specific study area or community where labour out-migration has resulted in subsequent changes in the agricultural sector. Overall, the authors selected 20 case studies for a systematic review and meta-analysis. The study sites spanned nine provinces and municipalities across different regions of China. The coding of the case studies followed a structured and iterative process, including the design of a preliminary manual for coding key contextual variables. These guidelines were not fixed but refined during the review process (in line with Schneider & Wagemann, Citation2010: 7).

Qin and Liao present a detailed operationalisation of all the constructed variables, providing the reader with a good understanding of all the conditions in the model. Dichotomous observations are mainly used to determine the attributes of migration effects on agriculture (eight out of ten). The outcome variable ‘Impacts of labour out-migration on’ is calibrated as negative (‘0ʹ) with, for instance, disinvestment in agriculture and/or farmland abandonment, or positive (‘1ʹ) with, for instance, remittances from labour migrants that subsidised agriculture, increased the scale of agricultural production and/or offset the negative effects of the absence of labour migrants. Two variables, one reflecting the magnitude of local labour out-migration, and the other reflecting the geographical location of the study site, allow for the inclusion of categorical variables with more than two possible values rather than just dichotomous data. The determination of values for each case is based on the qualitative and quantitative descriptions of the study sites of the selected cases. National average levels (such as for the assessment of local natural conditions and the quantity of farmland) are also used in the coding to ensure consistent data extraction.

The study also features an effective peer-code review process with both authors involved in the reviewing and coding of the variables to ensure the consistency of data extraction. This is clearly a beneficial practice, especially when a team of researchers are involved in the building of the database, to guarantee the quality, comparability and reliability of the data collected.

The full truth table is presented in the article, making the analytical minimisation process highly transparent for the research community. For ease of interpretation, six parsimonious combinations of factors are discussed, three related to the positive effects of migration on agricultural change and three related to negative effects. Also for ease of interpretation, only minimised solutions are presented for the identification of general patterns of conjoint configurations.

One of the main strengths of Qin and Liao’s study is that it goes beyond most other research on rural migration and agriculture (in China and other developing countries), which adopts either a micro-level or a macro-level perspective. By implementing QCA at a meso-level, the analysis is able to include factors that are often overlooked such as the contextual effects of local or community socioeconomics and the environmental characteristics of migration-related agricultural transformation. The resulting identification of patterns of multiple conjectural configurations with several different combinations of conditions discussed, contributes to a better understanding of the diverse pathways of migration effects on agricultural outcomes in rural China. This QCA analysis highlights the role of community contexts in shaping rural restructuring, an insight that can inform evidence-based rural development planning and policymaking. In fact, what the authors have done by implementing a QCA analysis in this way is to go beyond plain description and provide a ‘modest generalisation’ (Ragin, Citation1987: 31).

QCA at the micro-level: migration and networking in internet penetration in West Africa (Taylor, Citation2015)

Taylor’s research (Taylor, Citation2015) examines factors influencing internet access provision and adoption in Ghana, a country where public sector provision is minimal or even failing. The author pays particular attention to the importance of international mobility as a way for small-scale entrepreneurs – until now a neglected resource in internet penetration policies – to access technological resources and knowledge.

The dataset comprises survey data gathered from 95 internet cafés in Ghana in 2009. All the internet cafés in the northern three regions are surveyed (N = 68), together with an additional group of cafés in two districts of Accra (N = 27). Data collected on respondents’ past international movements and existing contacts indicates considerable diversity of mobility in terms of duration, destination, and aims (Taylor, Citation2015: 433). Respondents’ contacts and modes of forming ties are also highly varied. Survey results, complemented by qualitative interviews, lead the author to select the fsQCA method (Ragin, Citation2000; Taylor, Citation2011) to follow different threads of international mobility and networking derived from the initial analysis, with the aim of using QCA not only to test existing theories but also to generate new theoretical arguments (Schneider & Wagemann, Citation2010: 4). For these purposes, the author applies a mixed-methods approach by combining survey data, qualitative interviews, fsQCA, and social network analysis, each complementary in drawing out causal pathways that could demonstrate how different groups of respondents manage to provide internet connectivity in marginal areas.

In general, the aim of the QCA method is to highlight configurations of factors that contribute to a single outcome. In this study, the outcome is the operation of a financially viable and functioning internet café (but not to the exclusion of outliers – an important consideration where very different strategies appear to proliferate among cases). Two fsQCA models are employed, reflecting alternative definitions of the outcome variable. The first model is designed to test the classic factors from the literature on small business efficacy and survival in Africa (Frese, Citation2000), whereas a second model specifically examines factors related to mobility. In both models, the same dichotomous outcome variable is tested (‘Breakeven’). In the first model, four factors (dichotomous and fuzzy) are integrated into the truth table: formal accounts, technical ability, formal education, and broad networks. The author discusses the calibration of set membership scores in detail, based on theoretical reasoning.

Overall, the solution factors of the first model addresses 41 of the 95 cases, showing an interesting and initially counter-intuitive clash between formal education and business skills. The most surprising result of the first model is that finishing high school emerges as a disadvantage for the cases shown in two solution factors, with broad networks and accounting abilities functioning as substitutes for formal education. In fact, for a number of cases the QCA solutions reveal the importance of having broad networks, with no need for accounting or technical abilities, nor for educational qualifications, to run a successful business. This QCA analysis, therefore, provides grounds on which to reject the often-used argument from the relationship between education and small business development, as this alleged relationship does not provide a satisfactory explanation for the development of internet cafés in Ghana.

Taylor then applies a second QCA model exploring the notion of international connections as a path to breaking even. Four conditions are integrated into the second model (age, having migrated for work, foreign inputs, and contact with non-Ghanaians) with calibrations and specific rationales also discussed in detail. The solution factors from the second QCA model indicate three distinct groupings more evenly spread between locations, with 23 cases from the northern group and 16 from Accra (39 cases in total). These results highlight the importance of international networking and indicate that those who migrated for work overseas began to build lasting networks upon their return. The results also suggest, through the intersubstitutability of maturity and foreign inputs that younger entrepreneurs lacking start-up capital were using contacts initially made online for resources instead of using direct connections forged through travel.

In order to understand how the network dynamics and the movement of knowledge operates for small-scale entrepreneurs, the author complements her study by conducting a social network analysis, looking in particular at the dynamics of professional networking among the café owners. In doing so, she is able to demonstrate ‘a second level of diversity within the initial apparent diversity of mobility and networking strategies’ (Taylor, Citation2015: 440). The network analysis makes it possible to explore in detail how age, social status, ethnicity and location interact in shaping access to resources for local entrepreneurs.

Berg-Schlosser et al. (Citation2009) have noted that researchers using QCA make choices inthe course of their research for which they should be accountable. Scrutiny of these choices opens the ‘black box’ of formalised analysis (p. 14). For example, Qin and Liao (Citation2016) approach is deductive, aiming to test some theoretically informed hypotheses using QCA as the main or only method of analysis. By contrast, one of the main strengths of Taylor (Citation2015) is the use of multiple methods – a specific sequence of surveys, interviews, fsQCA and social-network analysis – to enhance the validity of the findings. Taylor’s use of QCA methodology can therefore be categorised as a grounded approach (Jopke & Gerritz, Citation2019). The QCA methodology can accordingly either be at the core of the analysis, often used then as part of a theory-driven approach, or be integrated as one method in a sequenced mixed method approach (Taylor, Citation2015). The iterative process of alternating between the cases, the mobilised theories, the computer-based analysis and the different methods is what makes the QCA approach both challenging and unique.

The two case studies we reviewed in detail explore the circumstances under which migration does lead to specific development outcomes (agricultural change in the first case study and internet penetration in the second). In fact, most QCA analysis so far only captures one side of the migration–development nexus and often addresses the effects of migration outcomesFootnote10 on development rather than examining the necessary and/or sufficient combinations of conditions that may explain the variation in migration aspirations and outcomes within a local population.

6. Conclusion

QCA is a methodological approach that attempts to ‘both bridge and transcend the qualitative-quantitative divide in social research’ (Ragin, Citation2014: xix). On the one hand, QCA requires in-depth knowledge of a sample of cases, which can be of various natures, including individuals, communities, firms or entire countries. On the other hand, QCA is a systematic method for identifying complex cross-case patterns in often mid-sized samples, although QCA may also handle larger sample sizes.

In fact, there is no upper limit to the number of cases – even though when the number of cases is large, QCA competes with quantitative-statistical approaches, and it becomes increasingly difficult to preserve the case orientation that distinguishes QCA.

Larger samples also increase the problems of contradictory rows. For larger samples, it is therefore even more important to triangulate QCA with other statistical analyses (Vis, Citation2012).

QCA aims to identify cross-case variation and patterns characterising the varying causally relevant conditions and contexts of cases. It allows the assessment of highly complex causal configurations involving different combinations of causal conditions that explain an outcome variable. QCA also aims to identify configurations of necessary and sufficient conditions. In doing so, it facilitates the identification of deterministic causal configurations by sorting out the necessary, sufficient and more complex INUS conditions for an outcome of interest. QCA thus helps to identify and describe causal patterns in the data that would otherwise remain undetected.

However, as in statistical analysis, where correlation between variables does not imply causation, the causal character of the relationship between a configuration of conditions and an outcome is a theory-informed assumption, not a conclusion. This assumption is warranted by the conceptual knowledge guiding the selection of variables included in the analysis. Case knowledge accompanied by alternation between the cases and the analytical solutions is one of the golden rules of QCA research.

Given the strengths and weaknesses of QCA as a method and methodology, future research exploring the migration–development nexus should triangulate QCA with other methods and embed it into a more comprehensive mixed-methods framework. The unique features of QCA can shed new light on long-standing research questions by challenging assumptions, testing theories, exploring patterns in data, and highlighting complex, non-linear, asymmetric, and interconnected relationships between migration and development. In adopting QCA, researchers have found a middle ground between qualitative and quantitative approaches. The method makes it possible to replicate some findings, an objective known to be hard to achieve with the use of qualitative approaches only. QCA’s focus on the systematic comparative case approach allows for generalisation beyond the observed cases. In addition, the case-specific knowledge often limited in quantitative studies has revealed complex causal patterns, creating a better understanding of the migration–development nexus.

As a research approach and analytical method, QCA can enrich the field of migration and development studies in multiple ways. First, it may refine our understanding of the multi-dimensional impacts that development processes can have on migration processes and outcomes. Second, it may identify in which ways complex configurations of migration and migration-related factors can shape development outcomes. Third, applied at multiple levels, QCA can explain how migration shapes opportunities, attitudes, and behaviour at the individual or household level – and, equally, how these effects, in turn, influence the development trajectories of local areas and entire nations.

As we know, the effects of migration on development, and vice versa, are highly complex and often context-specific, so that overall conclusions often reflect fads in academic and policy communities. QCA as an innovative case-oriented approach helps disentangle seemingly puzzling and contradictory interactions between migration and development. Insights gained through configurational analysis can enrich the evidence base and provide more nuanced policy recommendations, which may ultimately contribute to the design of more effective migration and development policies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mathias Czaika

Mathias Czaika is a Professor of Migration and Integration and Head of the Department for Migration and Globalisation at Danube University Krems, Austria.

Marie Godin

Marie Godin is a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at the Refugee Studies Centre (University of Oxford) and research associate at the University of Oxford’s Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS).

Notes

1. COMPASSS (COMPArative Methods for Systematic cross-caSe analySis) is a global network bringing together researchers involved in theoretical, methodological and practical developments of the QCA approach. See www.compasss.org [Last accessed: 26/11/2020].

2. Whereas 38 articles are tagged specifically with the keyword ‘Development’, the database refers to different types that can be classified as follows: Economic Development (12), Welfare State/Care Services (4), Conflict and Development (2), Conservation/Nature and Development (2), Human Development (1), Urban Development/Rural Development (1, 1), Institutional/National Development (2), Language Development (1), QCA Analysis (1).

3. For instance, at the 16th IMISCOE Annual Conference Understanding International Migration in the 21st Century: Conceptual and Methodological Approaches (Malmö, 26–28 June 2019), only one paper (out of several hundred) was based on QCA methodology. The IMISCOE Network connects 50 member institutes and around 1000 individual members from within as well as beyond Europe and is central in the development of migration research (see 2019 conference programme: https://www.imiscoe.org/images/conference-2019/konferensprogram-imiscoe-2019.pdf.

4. In the MIGNEX project, we acknowledge that the concept of development is without question a contentious and complex one, which can be defined as ‘a multi-faceted process of social transformation with multiple, context-specific manifestations that are sometimes contradictory even within one country’ (Carling, Citation2019, p. 9). Within that perspective, ‘specific developments’ can be identified that are experienced at the local or regional level such as: major infrastructure projects, a rapid expansion of livelihoods, a collapse in livelihoods, a wide-ranging legal or policy change, the depletion of a natural resource, an increased security threat or new opportunities for education. All these specific forms of development can have either a positive or a negative impact on the population, they can be intentional or not, gradual or sudden, and they can be either entirely or partly the result of a policy intervention. They can also influence migration flows, aspirations and types of migration (see Carling, Citation2019).

5. Accessed in November 2020.

6. ‘Global’ refers to articles with a comparative perspective with one country or several countries in Africa Latin America, Asia, Middle East, North America and/or Europe.

7. Key words in the COMPASSS database used were the following: the OECD’s 37 members, ‘European Union’ and ‘OECD’. The range of studies with the ‘EU’ as research interest is probably even bigger. Running the query with ‘EU’, the result is 189 entries for the entire COMPASSS database.

8. The categories used for the analysis relate to various aspects of development used in the MIGNEX research project and which will be used later in various QCA analyses explaining migration and development outcomes, respectively (see Czaika & Carling, Citation2019).

10. ‘Migration’ can be represented by several types of conditions, including the scale of out-migration and return migration, the prevalence of migration aspirations and failed migration attempts, and the importance of remittances (see Czaika & Carling, Citation2019, p. 2).

References

- Ansorg, N. (2014). Wars without borders: Conditions for the development of regional conflict systems in sub-Saharan Africa. International Area Studies Review, 17(3), 295–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/2233865914546502

- Befani, B. (2016). Pathways to change: Evaluating development interventions with qualitative comparative analysis (QCA). Expertgruppen för biståndsanalys (the Expert Group for Development Analysis). http://eba.se/en/pathways-to-change-evaluating-development-interventions-with-qualitative-comparative-analysis-qca

- Berg-Schlosser, D., De Meur, G., Rihoux, B., & Ragin, C. C. (2009). Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) as an approach. In B. Rihoux & C. C. Ragin (Eds.), Configurational comparative methods: Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) and related techniques (pp. 1–18). Sage.

- Bijak, J. & Czaika, M. (2020). Assessing Uncertain Migration Futures: A Typology of the Unknown, QuantMig Project Paper No.1.1, University of Southampton, UK. http://quantmig.eu/res/files/QuantMig%20D1.2%20v1.1.pdf

- Carling, J. (2019). Key concepts in the migration–development nexus, MIGNEX Handbook, Chapter 2 (v2). Peace Research Institute Oslo. www.mignex.org/d021

- Clemens, M. A. (2011). Economics and emigration: Trillion-dollar bills on the sidewalk? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(3), 83–106. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.25.3.83

- Clemens, M. A. (2014). Does development reduce migration? In R. E. B. Lucas (Ed.), International handbook on migration and economic development. Edward Elgar Publishing, 152–185.

- Clemens, M. A., & Postel, H. M. (2018). Deterring emigration with foreign aid: An overview of evidence from low-income countries. Population and Development Review, 44(4), 667–693. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12184

- Czaika, M., & Carling, J. (2019). QCA conditions and measurement, MIGNEX Handbook Chapter 6 (v1). Peace Research Institute Oslo. http://www.mignex.org/d025

- Czaika, M., & Reinprecht, C. (2020). Drivers of migration. A synthesis of knowledge, IMI working paper No. 163, University of Amsterdam.

- Da Roit, B., & Weicht, B. (2013). Migrant care work and care, migration and employment regimes: A fuzzy-set analysis. Journal of European Social Policy, 23(5), 469–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928713499175

- De Haas, H. (2010).Migration and Development: A Theoretical Perspective. International migration review, 44(1), 227–264.

- De Haas, H., Czaika, M., Flahaux, M. L., Mahendra, E., Natter, K., Vezzoli, S., & Villares‐Varela, M. (2019). International migration: Trends, determinants, and policy effects. Population and Development Review, 45(4), 885–922. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12291

- Dekker, R., & Scholten, P. (2017). Framing the immigration policy agenda: A qualitative comparative analysis of media effects on dutch immigration policies. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 22(2), 202–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161216688323

- Durand, J., & Massey, D. S. (1992). Mexican migration to the United States: A critical review. Latin American Research Review, 27(2), 3–42.

- Ebeturk, I. A., & Cowart, O. (2017). Criminalization of forced marriage in Europe: A qualitative comparative analysis. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 58(3), 169–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715217710065

- Frese, M. (2000). Success and Failure of Microbusiness Owners in Africa: A Psychological Approach. Westport: Quorum Books.

- Geertz, C. (1973). Thick descriptions: Toward an interpretive theory of culture (Chapter 7). In The interpretation of cultures (pp. 5019). Selected essays. Basic books , Inc. New York.

- Groth, J., Ide, T., Sakdapolrak, P., Kassa, E., & Hermans, K. (2020). Deciphering interwoven drivers of environment-related migration – A multisite case study from the Ethiopian highlands. Global Environmental Change, 63, 102094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102094

- Guérin, N. (2018). One wave of reforms, many outputs: The diffusion of European asylum policies beyond Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(7), 1068–1087. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1425476

- Haeffner, M., Baggio, J. A., & Galvin, K. (2018). Investigating environmental migration and other rural drought adaptation strategies in Baja California Sur, Mexico. Regional Environmental Change, 18(5), 1495–1507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-018-1281-2

- Hasić, J. (2018). Post-Conflict cooperation in multi-ethnic local communities of bosnia and herzegovina: A qualitative comparative analysis of diaspora’s role. Journal of Peacebuilding & Development, 13(2), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/15423166.2018.1470024

- Hooijer, G., & Picot, G. (2015). European welfare states and migrant poverty: The institutional determinants of disadvantage. Comparative Political Studies, 48(14), 1879–1904. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414015597508

- Jopke, N., & Gerritz, L. (2019). Constructing cases and conditions in QCA – Lessons from grounded theory. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 22(6), 599–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2019.1625236

- Mackie, J. L. (1974). The cement of the universe: A study of causation. Clarendon Press.

- Mastrorillo, M., Licker, R., Bohra-Mishra, P., Fagiolo, G., Estes, L. D., & Oppenheimer, M. (2016). The influence of climate variability on internal migration flows in South Africa. Global Environmental Change, 39, 155–169.

- Meuer, J., Ellersiek, A., Shephard, D., & Rupietta, C. (2018). Reflecting on the use of qualitative comparative analysis. Oxfam, Policy and Practise. https://views-voices.oxfam.org.uk/2018/05/reflecting-on-the-use-of-qca/

- Nyberg–Sørensen, N., Hear, N. V., & Engberg–Pedersen, P. (2002). The migration–development nexus: Evidence and policy options. International Migration, 40(5), 49–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2435.00211

- Pattyn, V., Molenveld, A., & Befani, B. (2017). Qualitative comparative analysis as an evaluation tool: Lessons from an application in development cooperation. American Journal of Evaluation, 40(1), 55–74.

- Qin, H., & Liao, T. F. (2016). Labor out-migration and agricultural change in rural China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Rural Studies, 47, 533–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.06.020

- Ragin, C. C. (1987). The comparative method: Moving beyond qualitative and quantitative strategies. University of California Press.

- Ragin, C. C. (2000). Fuzzy-set social science. University of Chicago Press.

- Ragin, C. C. (2006). Set relations in social research: Evaluating their consistency and coverage. Political Analysis, 14(3), 291–310. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpj019

- Ragin, C. C. (2008). Redesigning social inquiry: Fuzzy sets and beyond. University of Chicago Press.

- Ragin, C. C. (2014). The comparative method: Moving beyond qualitative and quantitative strategies: With a new introduction. University of California Press.

- Rihoux, B., & Ragin, C. C. (2008). Configurational comparative methods: Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) and related techniques (Vol. 51). Sage Publications.

- Rubenzer, T. (2008). Ethnic minority interest group attributes and U.S. Foreign policy influence: A qualitative comparative analysis. Foreign Policy Analysis, 4(2), 169–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-8594.2007.00063.x

- Schneider, C. Q., & Wagemann, C. (2010). Standards of good practice in qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) and fuzzy-sets. Comparative Sociology, 9(3), 397–418. https://doi.org/10.1163/156913210X12493538729793

- Schneider, C. Q., & Wagemann, C. (2012). Set-theoretic methods for the social sciences: A guide to qualitative comparative analysis. Cambridge University Press.

- Seate, A. A., Joyce, N., Harwood, J., & Arroyo, A. (2015). Necessary and sufficient conditions for positive intergroup contact: A fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis approach to understanding intergroup attitudes. Communication Quarterly, 63(2), 135–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2015.1012215

- Spilimbergo, A. (2009). Democracy and foreign education. American Economic Review, 99(1), 528–543. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.99.1.528

- Taylor, L. (2011). “Paths to Viability: Transnational Strategies Among Ghanaian Internet Cafes.” Oxford International Migration Institute. Working Paper Series, WP‐51‐2011

- Taylor, L. (2015). Inside the black box of internet adoption: The role of migration and networking in internet penetration in West Africa. Policy & Internet, 7(4), 423–446. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.87

- Vis, B. (2012). The comparative advantages of fsQCA and regression analysis for moderately large-N analyses. Sociological Methods & Research, 41(1), 168–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124112442142

- Walbott, T. (2014). Citizenship and immigration in Western Europe: National trajectories under post-national conditions? A qualitative comparative analysis of selected countries. MMG Working Paper 14-12. https://www.mmg.mpg.de/61274/wp-14-12.