ABSTRACT

In this article, we analyse the interaction between anti-vehicle mine (AVM) clearance and longer-term peacebuilding and development in relation to agricultural, conservation, trade, and infrastructural development priorities in the provinces of Cuando Cubango and Huambo in Angola. AVM clearance has not always been prioritised in the humanitarian mine clearance phase but is critical in later developmental stages due to the increased need for and use of infrastructure. To investigate the interaction between clearance, peacebuilding and development outcomes, we deploy the Mine Clearance and Peacebuilding Synergies (MPS) framework. Our critical analysis of qualitative primary data demonstrates how clearance engages Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and infrastructure priorities towards improvements in agricultural production, trade and access to markets, social and physical infrastructure and social cohesion. But its impacts are challenged by endogenous factors such as wider infrastructural investment and exogenous factors including environmental and climate change concerns.

Introduction

One of the legacies of over 40 years of conflict that ended in 2002 is that Angola is presently thought to be one of the most heavily mined countries in the world.Footnote1 The conflict has had several distinctive periods, the secession and War of Independence (1961–75)Footnote2; the post-independence and Cold War period (1975–91)Footnote3 and (1992–2002)Footnote4 the post-election conflict period.Footnote5 Across these periods, landmines were a key feature although much of the contamination resulted from the War of Independence period of 1975 and the Cold War period of 1988.Footnote6 Anti-vehicle mines (AVMs) were laid for different purposes specifically for blocking roads and tracks and disrupting the movement of opposing forces’ troops and supplies. They were also used for the protection of strategic infrastructure.Footnote7 Random mines were also scattered to deter attacks and to instil terror including to civilians.Footnote8 AVMs pose an indiscriminate threat, killing and injuring civilians driving standard motor vehicles, agricultural equipment and construction equipment.Footnote9 As such, clearance is imperative for longer term peacebuilding and development. Against this background, this study analyses the interaction between AVM clearance and longer-term peacebuilding and development in relation to agricultural, conservation and trade priorities as mediated through infrastructure.

By 2017, Angola’s mine action authority, Comissâo nacional intersectorial de desminagem e assistência humanitária (CNIDAH) – the National Inter-sector Demining Commission and Humanitarian Assistance reported that the continued presence of mines remained an impediment to development projects related to economic diversification, agriculture, tourism, and mining.Footnote10 In 2019 fuel exports constituted 95% of merchandise exports.Footnote11 Contamination prevents access to the regions of Cuando Cubango province, the Mavinga and Luengue-Luiana National Parks,Footnote12 which are home to a wide range of wildlife including the largest remaining population of African elephants.Footnote13 AVMs therefore continue to limit the potential to unlock economic diversification in eco-tourism and conservation. By 2017, mine clearance organisations reported having only cleared 56% of known landmine-contaminated landFootnote14; majority of which is AVM contamination. This indicates that the lifespan of these mines and their socio-economic impact is not limited.

This paper questions the extent to which mine action, especially mine clearance, influences long-term peacebuilding and development in Angola. It deploys the Mine Clearance and Peacebuilding Synergies (MPS)Footnote15 conceptual framework to guide its analysis.Footnote16 Upon this basis, the paper argues that the interactions between mine clearance and long-term peacebuilding and development are mediated by interactions between infrastructure and economic and physical reconstruction. The paper’s analysis draws on primary qualitative data from fieldwork collated through nine focus group discussions and 31 interviews in 2019. This approach enables analysis of the interactions between mine clearance and socioeconomic factors across geographical spaces, rural and peri-urban contexts.

This paper makes three key contributions. First, centring longer-term interactions between peacebuilding, development and mine clearance deepens understanding of the impact of contamination or clearance long after conflict has ceased. Doing so moves beyond the literature on the socioeconomic impactsFootnote17 of clearance that is dominated by short-term analyses and attention to humanitarian concerns. Second, the paper deploys data-driven analysis, in a context where access to primary data can be limited. Third, the use of the MPS framework extends the literature on critically theorising the SDGs and thus offers an analytical tool for broader use.

The paper is structured as follows. First, it examines how mine clearance/action has over time interacted with peacebuilding in Angola. Second, it outlines the conceptual framework to be deployed, the MPS Framework. Third, it presents the methodological approach. Fourth, it deploys the MPS Framework to understand and explain how mine clearance interacts with economic and physical reconstruction with reference to infrastructure development and SDGs in previously mine contaminated provinces in Angola. The final section concludes by setting out the wider significance of this contribution.

Locating mine action within peacebuilding in Angola

Mine actionFootnote18 has previously been considered narrowly within the field of security in academic literature rather than as an activity that supports peacebuilding.Footnote19 This is due to its characterisation as a set of specialised and distinct technical activities. However, the UN places mine clearance alongside other activities as a part of the broader discourse of peacebuilding through the ‘Agenda for Peace’.Footnote20

Mine action has been part of Angola’s peace processes in various ways. Mine clearance was part of the 1991 Bicesse Accord under the UN Angola Verification Mission (UNAVEM I) teams and in the 1994 Lusaka Protocol as part of the peace agreement. Following the cessation of the conflict in 2002, the UN Emergency Coordinator in Luanda called for mine action activities to be integral to the peace process.Footnote21

Beyond the immediate post-conflict peacebuilding period, mine clearance has remained critical in every phase of Angola’s reconstruction landscape. After the final conflict phase, only 30% of the areas for return were considered fit for resettlement by the United Nations.Footnote22 In addition, only 3% of arable land was being farmed partly due to mine contamination and displacement (Foley 2007; Unruh 2012).Footnote23 Humanitarian organisations required access to displaced populations and were only able to reach 60% of them due to the precarious security conditions, notably attacks on civilians and vehicles and contamination (Proto and Glover 2003: 15). Contamination also hampered efforts of mine clearance and humanitarian organisations to survey or clear minefields.Footnote24 This in part contributed to a lack of clarity on the state of mine-affected communities due to challenges of validity of data, accuracy and coverage.

The initial Landmine Impact Survey (LIS) undertaken in 2005, provided the baseline data but did not cover some communes in the provinces of Malanje and Lunda Norte due to inaccessibility. It is notable that initial surveys (also beyond Angola) relied on community perception and therefore areas that were not directly associated with communities, such as roads or other infrastructure, were not included.Footnote25 Thus, a nationwide re-survey of contamination in all 18 provinces was undertaken in 2019 enabling a significant amount of uncontaminated land to be released. This process also provided a clearer understanding of the extent of contamination.Footnote26

Nevertheless, a substantial amount of progress has been made since the start of mine action activities, and this has led to all known mined areas in some provinces such as Huambo being declared mine free, as of 2021. Other provinces such as Cuanza Norte, Uige, and Zaire are reported as being very close to completion.Footnote27 Clearance efforts (including surveys) have been supported by the government and donors through local and international mine clearance organisations. As at the end of 2022 a total of 1,070 antipersonnel mined areas with an estimated size of 68 km2 remained to be addressed in 16 of Angola’s 18 provinces; this comprised of 934,525 m2 across 89 Confirmed Hazardous Areas (CHAs) and 84,235 m2 across 21 Suspected Hazardous Areas (SHAs).Footnote28 In addition to its antipersonnel mine contamination, at the end of 2020 Angola had 1.02 km2 of AVM contamination.Footnote29 It is expected that additional contamination may continue to be found as operators gain more access to remote areas.Footnote30

Post-conflict countries including Angola needed to ‘jump start’ their economies through investments in strategic sectors and a focus on the communities most disrupted for instance, through small-scale farming and critically mine clearance.Footnote31 Mine clearance was necessary for the communities to access the fertile farmlands including Huambo province, a former breadbasket of Angola, and the fertile Mavinga Valley in Cuando Cubango. Mine action facilitated access to safe road and railway networks essential for trade and movement of people without access to air transportation.Footnote32 It was also critical for communication between provinces to enable a (renewed) sense of national cohesion.

Decades after the conflict, efforts towards diversifying the economy remain hindered by landmines. For instance, in the headwaters of the Okavango, contamination of large areas makes this a lethal habitat for both animals and local people.Footnote33 This not only limits diversification as with tourism but also contributes to environmental degradation as the presence of mines drives impoverished communities to poaching and logging activities that lead to biodiversity loss and threaten the sustainability of one of the largest carbon sinks on the planet.Footnote34

Few studies link clearance to development and peacebuilding processes.Footnote35 This may be influenced by the reticence by mine action actors to link clearance to the political nature of post-conflict peacebuilding, including addressing post-clearance land distribution. While Harpviken and RobertsFootnote36 offer empirical evidence from Afghanistan, Sri Lanka and Sudan, they acknowledge this is focused on the less tangible impact of mine action in the political sphere. This happens when mine action organisations strive to adhere to their mandates to remain neutral and fail to adequately engage with political concerns such as land tenure or ownership issues.Footnote37 BottomleyFootnote38 challenged this tendency which neglects the interlinkages between clearance and political dynamics thus calling for engagement with a wider sphere of actors including traditional leaders and communities.

Unruh’sFootnote39 Angola study is the only one, to our knowledge, that links mine action to peacebuilding. They argue that clearance and land rights are critical peacebuilding priorities that need to operate in a complementary or synergistic manner. Our study offers an expansive examination of these interactions, with a stronger focus on outcomes and impacts on livelihoods, socio-economic recovery, and longer-term development.Footnote40 This is important with shifts into longer term development, where AVM contamination can challenge progress through the use of infrastructure and capital equipment.Footnote41

Conceptual framework

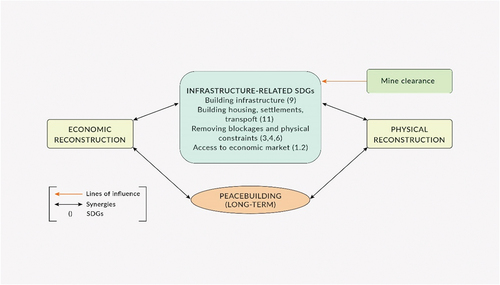

This paper analyses the extent to which the clearance of AVMs interacts with peacebuilding, as economic and physical reconstruction, through infrastructural development. Infrastructural development is significant to peacebuilding and development efforts that underpin ambitions for sustaining peace.Footnote42 However, the impact of infrastructure on peacebuilding can be complex and mediated by a range of contextual and structural realities.Footnote43 The study deploys the Mine Clearance and Peacebuilding Synergies (MPS) Framework, see .Footnote44 We focus on mine clearance as an element of the more comprehensive mine action, which is understood as comprising clearance, risk education, advocacy, victim assistance and stockpile destruction.Footnote45 Using this framework elevates the interdependencies between infrastructure, economic and physical reconstruction, and peacebuilding.

This analytical framework comprises line/s of influence, from mine clearance to infrastructure-related SDGs.Footnote46 In addition to line/s of influence, it includes the synergies, on the interactions between the infrastructure-related SDGs and economic as well as physical reconstruction. The MPS Framework does two things. It identifies and interrogates the assumed trajectory, line/s of influence, from mine clearance to infrastructure-related SDGs. Then it considers and examines the synergies between the infrastructure-related SDGs and economic as well as physical reconstruction that are also synergised with long-term peacebuilding. In doing so, while the MPS Framework is premised on the trajectory of mine clearance to peacebuilding it centres how this is mediated by economic and physical reconstruction.

The MPS Framework builds on the interactions between the Humanitarian Mine Action Peacebuilding Palette, the Infrastructure as Peacebuilding framework and the Mine Action-SDGs frameworkFootnote47 that reinforce the importance of infrastructure to peacebuilding that is developmental.Footnote48 First, Palette locates economic and physical reconstruction (part of long-term peacebuilding) as connected, even if, superficially with mine clearance. Second, the Infrastructure as Peacebuilding framework centres the potentially transformative role of infrastructure across macro and societal as well as community contexts alongside associated tensions. Third, the Mine Action-SDGs framework, identifies intrinsic linkages between developmental outcomes via the SDGs to mine action, including mine clearance (this paper’s focus) which is reflected as land release. The extensive focus on empirical outcomes that is offered by the Mine Action-SDGs Framework can be connected to the longer-term developmental concerns articulated by the Palette.

It is assumed that mine action contributes to peacebuilding by default and that these intrinsic peacebuilding values are explicit. However, such an assumption has often masked the more difficult questions, such as when or why its impact may be negative.Footnote49 Angola exemplifies this, when at the end of the war, land, especially fertile agricultural land, was the subject of conflicting interests while returning displaced communities and new settlers in a very fragile post-war period.Footnote50 However, as UnruhFootnote51 and Unruh & ShalabyFootnote52 observed, following clearance and issues around land rights,Footnote53 the reallocation of land resulted in outcomes that worked significantly against peacebuilding when not addressed in an integrated manner. Yet, this remained unexamined. This proposed framework squarely tackles the complexity that attends mine clearance and mine action as part of peacebuilding as mediated through infrastructure. Part of this challenge is linked to the criticisms that are levelled at the SDGs in the limited extent to which they engage with complex political economy factors.Footnote54

Deciphering evidence from Angola

This paper utilises qualitative methods for examining primary data. The study analyzes data from 31 semi-structured and unstructured interviews and nine focus group discussions.Footnote55 In Huambo, there were nine interviews and two focus group discussions, in Luanda there were seven interviews and Cuando Cubango there were 15 interviews and seven focus group discussions conducted in July and August 2019. The two provinces (Huambo and Cuando Cubango) were part of the 15 in which mine clearance had been prioritised in Angola’s poverty reduction strategy. Cuando Cubango is historically one of the most mine-affected provinces.Footnote56 This is the location of the battle of Cuito Cuanavale that has been described as largest battle on African soil since World War II, and the municipality remains one of most landmine contaminated places in the world.Footnote57

At the time of the study, Huambo was about to attain ‘mine free status’ and therefore was an ideal context for a longer-term analysis and documentation of development outcomes arising from clearance. Cuando CubangoFootnote58 was useful for analysing the results of clearance in the development of a previously marginal and impoverished region.Footnote59 After the peace agreement in 2002, only three of the nine municipalities in Cuando Cubango remained connected by road due to contamination.Footnote60

Interviews and FGDs were conducted in Nganguela (main language in Cuando Cubango), Umbundu, (main language in Huambo) and Portuguese with the assistance of translators. Interviews with international NGOs were conducted in English. These addressed mine clearance prioritisation across time and space, interaction between clearance, politics, economic, cultural and social factors as well as peace and reconciliation, mine contamination, strategic infrastructure, local and international political economy dynamics. The data was coded across 56 titles that cover: topics related to the interaction between mine clearance and physical infrastructure such as land access and use, transport and transport infrastructure for road, air and rail travel, amenities, energy and water systems (SDGs 3,4,6,7,9,11); topics related to economic reconstruction including land access and use, reconstruction of settlements, trade, cultivation and natural resources and tourism (SDGs 1,2,8,10,11,12); topics related to environmental concerns including conservation (SDG 15) and topics related to trust in land, mobility, safety and security as well as international partnerships (SDG 16,17).

Analysis of the data generated three themes for interrogating the interlinkages between mine clearance, economic and physical reconstruction with attention to infrastructure-related SDGs. The themes are clearance, agriculture and reconstruction; clearance, conservation, tourism and reconstruction; and clearance, transportation, trade and mobility.

With reference to , we use the MPS Framework for analysis in two parts. First, we discuss how clearance influences and interacts with infrastructure and related SDGs and the synergies with economic reconstruction (and therein long-term peacebuilding). Second, we discuss how clearance influences and interacts with infrastructure and related SDGs and the synergies that are identifiable with physical reconstruction (and therein long-term peacebuilding). Discussions focus on economic sectors and activities including agriculture (livestock and cultivation), commerce and trade as well as strategic infrastructure, including transportation and energy.

Deploying the MPS framework 1: mine clearance and agriculture

Agriculture is a key context in both field sites especially Huambo province, once considered the country’s breadbasket.Footnote61 In Huambo, agricultural production has focused on staple foods including cassava, beans, sweet potatoes and potatoes with a noted outward shift from subsistence to local trade.Footnote62 This shift has been linked to greater mobility as well as more expansive use of increasingly technical impedimenta.Footnote63 Agricultural development has been a motivating factor for planning and implementing mine action and clearance.Footnote64 Agriculture represents a key part of the strategy to diversify Angola’s economy, and clearance of landmines remains key to achieving this.Footnote65 Clearance by both national and international mine clearance agencies has prioritised agriculture. A civil servant notes that ‘HALO and INAD cleared mines not just for access to roads but also agriculture[al] area’.Footnote66 There is a tendency to prioritise cleared lands located close to roads for agricultural activity.Footnote67

There is greater availability of arable land due to clearance. In Huambo, these authors observed the cultivation of beans on cleared land following a two-year hiatus as well as planned further cultivation in the subsequent planting season.Footnote68 An interviewee notes ‘Since lands were cleared, people have…better access to cultivation area’.Footnote69 Improved access to land is linked also to variety in agricultural cultivation. In Cuando Cubango, an interviewee highlights that ‘when demining was conducted there was an increase in crop diversification [with] the production of cassava and rice’.Footnote70 An interviewee connects clearance in Huambo to more varied crop production and profits through greater supply of more profitable foods, ‘After clearance there was huge change in a diversification of products … … in the beginning they focused more on growing cereals … but with clearance they grew more potatoes and vegetables as these were more profitable’.Footnote71

Clearance enables links between improved agricultural performance and increased use of infrastructure and capital equipment including animal traction, tractors and irrigation. This underpins multiple cropping seasons and higher production. In parts of Cuando Cubango, tractors and other forms of capital equipment use, such as irrigation, have been deployed due to an increased sense of safety. In Huambo, an interviewee notes ‘We are now seeing a shift from manual approaches to more mechanical traction and animal traction’ and ‘It is … possible to cultivate across two seasons- there is also access to using irrigation that allows production in the dry season’.Footnote72 The Vice Governor reported that clearance enabled water supply in support of agricultural activities.Footnote73

Mine clearance supports the development and use of water supply infrastructure and irrigation with implications for SDGs and improved technology. Utilising the MPS Framework shows clearance influences infrastructure development and use and removing blockages (SDGs 9,3,4,6) and is synergised with economic reconstruction through diverse and higher quality food production.

Against the background of improved agricultural production, clearance has been identified as improving agricultural trade due to better market access linked to transport facilities. When agricultural lands are cleared, use often depends on vicinity to transportation. An interviewee notes, ‘Whether people use the lands for agriculture after clearance … depends on location of area. If it is near main roads, it is commonly used for agriculture’.Footnote74 Clearance of transport infrastructure enables the movement of agricultural goods across areas. On trade improvements, an interviewee highlighted the significance of reduced journey times due to clearance.Footnote75 Interviewees note that ‘There is trade from Cuando Cubango and Cuchi to Menongue … The availability of these products in Menogue is made possible by the availability of trains’Footnote76 and ‘the railway has facilitated trade between Namibe and Cuando Cubango’.Footnote77 This has implications for accessing new markets as products can be moved to new consumers. An interviewee argues that ‘Due to increased trade, external product[s] all come to and are consumed in Cuando Cubango’.Footnote78 In Huambo, clearance has been linked to well developed and administrated markets due to an increased sense of safety and security for traders and consumers. This is reinforced by an interviewee as follows, ‘sell their stuff and come to the market with expectation … mine clearance is the main reason for the improvement in trade … people are no longer so afraid of the risk of attacks from mines. There is a greater sense of security and safety’.Footnote79

Utilising the MPS framework shows clearance influences improved access to new markets, improved product varieties and transportation infrastructure (SDG 1,2,9,11). This is synergised with economic reconstruction through improved trade and competitive prices and reinvigorated institutional (market) structures across provinces and improved safety and security (SDG 16).

Yet, clearance is not a sufficient condition for improved outcomes. In some cases, it requires wider infrastructural interventions for fuller benefits to accrue to the affected communities. As one interviewee notes, ‘Having vehicles is linked to mine clearance (on the road) but for the increased mobility, it is not only about mine clearance, but also about availability of transportation’.Footnote80 A clear constraint emerges in the challenged road transport network. An interviewee reflects that the lack of road access into bigger fields increases the cost of getting produce into markets.Footnote81 This reinforces findings from previous studies in other contexts including Somaliland and Afghanistan on the need to sustain benefits from clearance through wider investments.Footnote82

There are circumstances that undermine the potential benefits of clearance. In Cuando Cubango, cultivation and production increased gradually with impact on higher incomes and consumption of consumables and capital equipment.Footnote83 Yet environmental challenges, specifically droughts have undermined these outcomes. An interviewee was clear on the impact of droughts in 2019 as opposed to landmines and mine action in Cuando Cubango. Infrastructural interventions such as irrigation can address such challenges with more structural infrastructural investments such as boreholes and dams, however these raise ecological concerns.Footnote84 We found evidence of efforts to tackle these complexities through training programmes from a local NGO in Huambo, Development Workshop, that emphasise sustainable water use.Footnote85

Clearance has also enabled increased engagement in foraging with implications for conservation. An interview with the Ministry of Agriculture and participants in a FGD highlighted an increase in the number of people engaged in foraging in wooded areas, including to collect firewood.Footnote86 In Cuando Cubango, an interviewee notes producers ‘cultivating in places which were previously mined and circulating freely’.Footnote87 This can have ambivalent outcomes when juxtaposed to environmental concerns around conservation, reflecting also on SDG 15.

Deploying the MPS framework 2: mine clearance and transportation

Clearance of infrastructure, including transport-related infrastructure, is a key priority in the post-conflict period for humanitarian and developmental purposes. Following the post-conflict emergency phase, Angola’s priorities were outlined in the national development plan with a need for clearing and rehabilitating roads, railways and other key infrastructure as defined in planning documents (2013–2017Footnote88 and 2018–2022Footnote89).

An interviewee notes the importance of connectivity due to clearance for national reconciliation as part of peacebuilding.Footnote90 Vines et al. Footnote91 noted that the main visible peace dividend was freedom of movement across the country. This is significant given the targeting of the railways as part of a conflict strategy of disarticulation. The Huambo vice-governor clarifies that ‘Mine[s] were laid during the war in railways across different provinces; it was a strategic way to divide and split the country across North and South Angola’.Footnote92 In Cuando Cubango, rail travel is identified as a tool of social cohesion and integration. An interviewee reports ‘government policy on the low cost of train tickets is … a social and political tool to allow for reintegration of people … . trains act as a service to stop the marginalisation of populations … . through making the prices accessible for all’.Footnote93 Another notes that railway travel ‘Enhancing[es] human relations between the city and the countryside’.Footnote94 This reflects the significance of physical connectivity to social realities in this conflict-affected context.

Clearance of rail transport focused mainly on anti-vehicle mines and started with the railways and proceeded to the road verges. Rail reconstruction efforts have been resourced by domestic and foreign capital. Since 2012, Chinese capital, via loans, dependent on Angola’s petroleum resources, supported the reconstruction of the Benguela railway (that passes through Huambo) facilities as well as acquisition of locomotives and stock.Footnote95 This was led by the China Railway 20th Bureau Group Corporation.Footnote96 The reconstruction has implications for the movement of peoples and goods regionally in Angola across Benguela, Huambo, Luaou as well as internationally to the Democratic Republic of Congo. It started functioning in 2006 and was transporting about 2300 passengers per day from Huambo by 2019.Footnote97

An interviewee notes that the reconstructed Benguela railway led to, ‘Transferring [selling] fish especially dry fish from Benguela to other parts of the country … Moxico produce and transfer honey, cassava and fishes from Moxico river to other provinces such as Bie, Huambo, Benguela … Moxico … have access to agricultural produce, potatoes, onions, tomatoes from Huambo, and industrial goods, plastic products from Huambo, through the railway’.Footnote98 In Cuando Cubango, rail travel also enabled access to goods that would not otherwise be available, for example, due to the good rail connection between Cuchi and Menogue, corn and beans are available in Menogue.Footnote99

Utilising the MPS Framework, clearance influences the development of transport infrastructure, transport systems and access to markets (SDGs 11, 9, 1 and 2) and is synergised with physical reconstruction through improved railway systems and enabling pricing structures.

Clearance has been prioritised for reconstruction of physical transport infrastructure in Huambo and in Cuando Cubango. An interviewee from, CNIDAH highlights that ‘After 2002 peace agreement, emphasis on roads, provide access to roads … main roads were re-paved … connecting interprovincial access … focus on critical municipalities’.Footnote100 It has been a consistent priority in the development phase following the tail of conflict. The economic crisis in Angola that resulted in a recession in 2016–2019 implied a slowdown in road rehabilitation, as reconstruction projects were in decline due to shortfalls in capital.Footnote101

Harpviken et al.Footnote102 reiterates the importance of infrastructure for longer-term development priorities. Strategic infrastructure including road and rail development are core priorities in Angola. Roads have been identified as ‘the principal priority in Angola’s reconstruction plans’ averaging 2.8 billion USD over 2005–09.Footnote103 Clearance by both commercial firms and NGOs has been undertaken for roads including Menongue to Cuando Cubango, Longa to Cuando Cubango, Fio to Cuando Cubango, Menongue to Bie, Cuando Cubango to circa Mavinga and Caiundo to Catuitu, among others.Footnote104

Following clearance, road construction connects communities for trade and improved levels of social infrastructure, such as education, with implications for SDGs.Footnote105 The improvements have implications for transaction costs with reference to transportation. Interviews with a building materials store owner at Menongue main market reveal that the cost of transportation decreased from 700,000 to 540,000 kwanzas to transport 40 tonnes.Footnote106

Utilising the Mine Clearance Peacebuilding Synergies Framework shows clearance influences (road) infrastructure development, improved access to markets, removing blockages to aid access to amenities, including higher quality education (SDGs 11,9,3,4,6,1,2). This is synergised with physical reconstruction through road construction and reduced transport costs.

Road clearance has been important and critical to the construction of energy infrastructure including power lines and the hydroelectric dam in Huambo. An interviewee notes that AVM clearance made it possible to have ‘Roads to set up the powerlines for electricity and hydro dams … clearance on dam’ in Huambo.Footnote107 These have enabled the transmission of electricity to Huambo town, Huila and Bie provinces as of 2018.Footnote108

In one of the rural sites of research in this study, Liambambi, road and agricultural land clearance has been linked to a government initiative to expand a settlement through provision of social and physical infrastructure. An interviewee notes that “Between 2008 and 2010, the government encouraged people from small villages … move to the central villages (like Liambambi) near the main roads.Footnote109 Physical infrastructure is notable in water supply to encourage settlement as well as construction of primary schools. An interviewee noted a newly built water tank in H178 (with solar panel for pump) and the construction of two schools as examples of such an initiative.Footnote110,Footnote111

With reference to the MPS Framework, clearance influences development in transport (road), energy and water infrastructure and removing blockages that improve access to amenities (SDGs 11,9,3,4,6). This is synergised with physical reconstruction through physical and social infrastructure development and expansion in settlements.

Links between clearance and improvements in physical reconstruction and infrastructure use can be complicated,Footnote112 on the volatile interaction of roads reconstruction and peacebuilding. In our sites of study, there are concerns about the safety of the demined roads in terms of road use policy. An interviewee notes ‘concern about safety along the road (e.g. running over children, etc.) … asked government to put some speed limit on the road so that drivers can reduce speed near the village and school’.Footnote113 There are implications also for animal husbandry practices. From a FGD we learn residents keep ‘pigs, goats and cows but they do not keep them near the village because of the big road … to avoid traffic accidents’.Footnote114 There are reservations about the utility of roads in the absence of rehabilitation and/or certification beyond clearance. For instance, medical personnel remain unable to use roads, ‘Areas with no rehabilitation is still difficult even after mine clearance … difficult for doctors from municipality to come’.Footnote115 In some rural settings even where roads have been cleared, traders seek out three-wheel vehicles and animal carts to navigate roads in poor conditions. An interviewee notes that, ‘they tend to use motorcycles with three wheels to transport goods … they also use animal carts and three-wheel apes [scooters] … then they get to a point where cars may pick up’.Footnote116

Finally, the impact of clearance is mediated also by wider developmental conditions and agendas. Even where synergies are noted within the MPS Framework, these can rely on wider processes. In Huambo, the influence of clearance on road and infrastructure development has been reliant on higher-level development policies and programmes, notably efforts to relocate communities closer to main roads. Due to the 2015 oil price collapse, major net petroleum exporter, Angola, fell into recession over 2016–2019Footnote117 and reconstruction efforts were impacted negatively due to capital shortfalls. An interviewee notes, ‘Because of the economic crisis in Angola a lot of developments/reconstruction activities have slowed down … for instance roads were rehabilitated in the emergency phase but the (road) verges were not addressed … the lack of the resources has meant that clearance is unable to take place to support the building of the (road) verges’.Footnote118

Conclusion

Angola offers a context within which to respond to the research question on the extent to which mine action, and mine clearance in particular, influences peacebuilding and development. The paper addresses this through analysing the interaction between clearance and infrastructure with attention to the implications for SDGs and synergies with economic and physical reconstruction. The MPS framework outlines the trajectory from clearance through addressing SDG infrastructure priorities towards economic reconstruction outcomes of improved trade and competitive prices and rebuilding markets as institutions. This is alongside contradictions of the negative implications of climate change and lack of wider investment. Also presented are physical reconstruction outcomes of improved trade due to travel over shorter distances and better transport as well as energy infrastructure and new settlements, while highlighting the contradictions of safety and sustainable finance. Doing so moves beyond Infrastructure as Peacebuilding, Humanitarian Mine Action Peacebuilding Palette and the Mine Action-SDGs frameworks in the following ways: integrated analysis that considers interdependencies between security and development concerns; critical consideration of how mine clearance may not always yield desirable outcomes and; deepening the understanding of infrastructure as peacebuilding, with attention to relevant SDGs.

This paper contributes to the limited but growing scholarship on the longer-term impact of clearance beyond the humanitarian phase. It is an important subject as the impact of mine clearance on socio-economic factors has been dominated by short-term studies that have also been constrained by limited data. Yet the developmental and peacebuilding benefits to clearance can be delayed. This is especially the case for AVMs that are often not prioritised in the humanitarian phase but are critical in later developmental stages, due to the increased need for and use of infrastructure, particularly for transport. The paper’s findings also draw attention to the significance of climate change through droughts and water use and environmental concerns, including conservation. The paper’s findings address priority shifts across time from humanitarian to development phases and across space from rural to peri-urban contexts across Cuando Cubango and Huambo from agricultural communities, key railway hubs and new settlements. This should encourage interrogation into the temporal and spatial realities that impact the processes and outcomes of clearance.

Angola introduces notable dimensions to interrogating domestic and international political economy factors that influence interactions between clearance, economic and physical reconstruction. On the one hand, the influence of clearance on transport infrastructure, particularly rail infrastructure, has been contingent on foreign capital investments as well as social policies that prioritised connectivity as an element of a peace sustaining agenda. On the other hand, Angola’s reliance on petroleum exports and commodity price shifts has impacted the consistency of its infrastructural investments with implications for clearance outcomes. This highlights the need for analysis of the domestic and global dynamics that impinge on interdependencies between clearance, peacebuilding and development.

The paper deploys the MPS framework to analyse how mine clearance interacts with economic and physical reconstruction, as key components of peacebuilding and development. It examines how infrastructure mediates these interactions, making it a significant framework for engaging critically with the impact of mine clearance on peacebuilding and development processes, outcomes and a range of SDGs. Clearance is shown to contribute to improvements in agricultural production, trade and access to markets, social and physical infrastructure and social cohesion. But its impacts are seen to be challenged by endogenous factors such as wider infrastructural investment and exogenous factors including environmental and climate change concerns. This analysis demonstrates the significance of being attentive to how economic, social, cultural and environmental factors impinge on outcomes. Such an approach offers value for engaging other mine-affected contexts that face an array of complex realities.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all our research participants that gave of their valuable time and shared their rich knowledge and insights, Dr Annabel de Frece and the journal’s anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. We would also like to thank the Geneva International Center for Humanitarian Demining, Yeonju Jung as well as our funders. The standard disclaimers apply.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Eka Ikpe

Eka Ikpe is a Reader in Development Economics in Africa and Director, African Leadership Centre, King’s College London. She co-leads an African Research University Alliance and Guild Cluster of Research Excellence on Interdisciplinary Peace.

Sarah Njeri

Sarah Njeri is Lecturer in Humanitarianism and Development at SOAS; she is an interdisciplinary researcher whose research sits at the intersection between academia, policy and practice. Her research employs a critical lens in investigating the implications of Explosive Remnants of War in post conflict environments and also examines how the implementation of programs to address the same mimic the liberal peacebuilding critiques. Her current research is an exploration of how integrating environmental protection measures and promoting women’s participation can enhance the effectiveness and localisation in mine action.

Notes

1 Stott Noel, ‘Angola: Peace Process Kickstarts Commitment to Eliminate Landmines’, Arms Control : Africa 1, no. 3 (July 1, 2008): 6–7, https://doi.org/10.10520/AJA0000001_39; and Landmine Monitor, Landmine Monitor Report 2020 (New York: Human, 2020).

2 This involved the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), the National Front for the Liberation of Angola (FNLA), & the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA).

3 The Internationalisation amid the Cold War and after Independence.

4 This phase focused on the control of power and resources after the first peace negotiations and multiparty elections in 1992.

5 Angela Iborra et al., The Socio- Economic Impact of Anti-Vehicle Mines in Angola (Geneva: Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining, 2019); and Anthony G. Pazzanita, ‘The Conflict Resolution Process in Angola’, The Journal of Modern African Studies 29, no. 1 (1991): 83–114.

6 Human Rights Watch, Landmines : A Deadly Legacy (New York ; London: Human Rights Watch, 1993); and Isebill V. Gruhn, ‘Land Mines: An African Tragedy’, The Journal of Modern African Studies 34, no. 4 (1996): 687–99.

7 Including both military and civilian infrastructure, such as electricity pylons, roads, railroads, dams, oil installations, water pipelines, and strategic locations (including specific towns or military bases).

8 Human Rights Watch, Landmines : A Deadly Legacy; L.A.N.D.M.I.N.E. LANDMINE MONITOR, Landmine Monitor Report 1999 : Toward a Mine-Free Landmine Monitor Report 1999 : Toward a Mine-Free World (New York: International Campaign to Ban Landmines and Human Rights Watch, n.d.); and Rae McGrath, ‘Trading in Death: Anti-Personnel Mines’, The Lancet 342, no. 8872 (1993): 628–29.

9 HALO Trust, ‘Technical Challenges in Humanitarian Clearance of Anti‐Vehicle Mines: A Field Perspective HALO Trust’, CCW, Geneva, April 9, 2015, https://www.halotrust.org/media/1953/20150409-the-halo-trust-ccw-presentation-text.pdf.

10 Iborra et al., The Socio- Economic Impact of Anti-Vehicle Mines in Angola.

11 World Bank, ‘The World Bank in Angola Country Overview’, Text/HTML, World Bank, 2022, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/angola/overview.

12 Mavinga and Luengue-Luiana are important parts of the Kavango Zambezi Trans-frontier Conservation Area (KAZA TFCA), the globe’s largest conservation area, which spans Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

13 C. Vandome, ‘Mine Action in Angola: Clearing the Legacies of Conflict to Harness the Potential of Peace’ Chatham House, 2019, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2019-06-17-Angola.pdf; and Christopher Vandome and Alex Vines, ‘Tackling Illegal Wildlife Trade in Africa. Economic Incentives and Approaches’, London: Chatham House, 2018, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2018-10-11-tackling-illegal-wildlife-trade-africa-vandome-vines-final2.pdf.

14 MAG (UK), ‘Time to Change Course: Angola and The Ottawa Treaty’, Manchester: Mines Advisory Group (UK), 2017, https://maginternational.org/media/filer_public/a4/1a/a41a7fda-5959-42df-b59b-c55290dccce4/mag_issue_brief_-_angola__the_ottawa_treaty.pdf.

15 All SDGs except SDG 13 are linked to Mine Action within this framework.

16 Eka Ikpe and Sarah Njeri, ‘Landmine Clearance and Peacebuilding: Evidence from Somaliland’, Journal of Peacebuilding & Development 17, no. 1 (April 1, 2022): 91–107, https://doi.org/10.1177/15423166211068324.

17 For example Geoff HARRIS, ‘The Economics of Landmine Clearance in Afghanistan’, Disasters 26, no. 1 (2002): 49–54; Gareth Elliot and Geoff Harris, ‘A Cost-Benefit Analysis of Landmine Clearance in Mozambique’, Development Southern Africa 18, no. 5 (December 2001): 625–33, https://doi.org/10.1080/03768350120097469; Gareth Elliot, ‘Mozambique: Development through De‐mining’, in Beyond De-Mining: Capacity Building & Socio-Economic Consequences (South African Institute of International Affairs, 2000); and W.A. Byrd and B. Gildestad, The Socio-Economic Impact of Mine Action in Afghanistan: A Cost-Benefit Analysis (Afghan Digital Libraries, n.d.).

18 Mine Action is a collective term for ‘activities which aim to reduce the social, economic and environmental impact of landmines and ERW, including cluster munitions’ (United Nations Mine Action Service definition). These activities include advocacy, mine risk education, humanitarian demining or clearance, victim assistance, and the destruction of stockpiles. Mine Action Sector refers collectively to the various organisations that engage in integrated approaches seeking to reduce the disastrous impact of mines and other explosive remnants of war on affected communities. The sector is not a homogenous entity; rather, each organisation maintains and performs their specialities or preferences

19 K.B. Harpviken, ‘Measures for Mines: Approaches to Impact Assessment in Humanitarian Mine Action’, Third World Quarterly 24, no. 5 (n.d.): 889–908; Kristian Berg Harpviken and J. Isaksen, Reclaiming the Fields of War: Mainstreaming Mine Action in Development (Oslo & New york: United Nations Development Programme, 2004); Kjell Erling Kjellman et al., ‘Acting as One? Co-Ordinating Responses to the Landmine Problem’, Third World Quarterly 24, no. 5 (2003): 855–71.

20 B. Boutros-Ghali, ‘An Agenda for Peace : Preventive Diplomacy, Peacemaking, and Peace-Keeping : Report of the Secretary-General Pursuant to the Statement Adopted by the Summit Meeting of the Security Council On’, 1992; B. Boutros-Ghali, ‘The Land Mine Crisis: A Humanitarian Disaster’, Foreign Affairs 73, no. 5 (1994): 8–13; and K.M. Cahill, ed., Clearing the Fields : Solutions to the Global Land Mines Crisis (New York: Basic Books, 1995).

21 Human Rights Watch, ‘Landmines In Angola’, Human Rights Watch, 1993, https://www.hrw.org/reports/1993/angola/; Jon D. Unruh, ‘Eviction Policy in Postwar Angola’, Land Use Policy 29, no. 3 (July 1, 2012): 661–63, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2011.11.001; J.D. Unruh, ‘The Interaction between Landmine Clearance and Land Rights in Angola: A Volatile Outcome of Non-Integrated Peacebuilding’, Habitat International 36 (2012): 117–25; and Stott Noel, ‘Angola : Peace Process Kickstarts Commitment to Eliminate Landmines’.

22 Allan Cain, ‘Angola: Land Resources and Conflict’, in Land and Post Conflict Peacebuilding, ed. John Unruh and R Williams (Earthscan, 2013), 30.

23 Conor Foley, ‘Land Rights in Angola: Poverty and Plenty’, Humanitarian Policy Group, 2007, https://odi.org/en/publications/land-rights-in-angola-poverty-and-plenty/; Unruh, ‘The Interaction between Landmine Clearance and Land Rights in Angola: A Volatile Outcome of Non-Integrated Peacebuilding’, 2012.

24 For example, in 2003, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) recorded 41 anti-vehicle mine accidents, resulting in 22 people killed and 110 people injured.

25 Ángela IborraI et al., ‘The Socio-Economic Impact of Anti-Vehicle Mines in Angola Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining,’ 2019.

26 Landmine Monitor, ‘Landmine Monitor 2021’, ICBL & CMC, 2021, https://www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2021/landmine-monitor-2021.aspx.

27 Mine Action Review, ‘Clearing the Mines 2023- Angola’, Mine Action Review; NPA, 2023, 44, https://www.mineactionreview.org/assets/downloads/Angola_Clearing_the_Mines_2023.pdf (accessed December 28, 2023).

28 Mine Action Review, ‘Clearing the Mines 2023- Angola’.

29 Ibid.

30 Mine Action Review; and Tommy Trenchard, ‘A Lethal Legacy of Landmines in Angola’, Geographical, November 28, 2022, https://geographical.co.uk/culture/lethal-legacy-landmines-angola.

31 Phillipe Franzkowiak, Miguel Vilombo, and Aimad El Ouardani, World Insecurity: Interdependence Vulnerabilities, Threats and Risks e (Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse UK, 2014), 19–20.

32 IRIN, ‘Angola: Aid Efforts Hindered by Landmines, Poor Roads – Angola’, Online: ReliefWeb, November 21, 2003, https://reliefweb.int/report/angola/angola-aid-efforts-hindered-landmines-poor-roads.

33 IRIN, ‘Clearing Landmines for Conservation – Angola’, Online: ReliefWeb, March 4, 2020, https://reliefweb.int/report/angola/clearing-landmines-conservation.

34 Chris Loughran and Camille Wallen, ‘Conflict, Climate and Conservation’, Washington, D.C: Halo trust, 2021, https://www.halousa.org/media/7958/conflict-climate-conservation-the-halo-trust.pdf; for more discussions on the link between the environment and peacebuilding see Tobias Ide, Lisa R. Palmer, and Jon Barnett, ‘Environmental Peacebuilding from below: Customary Approaches in Timor-Leste’, International Affairs 97, no. 1 (January 1, 2021): 103–17, https://doi.org/10.1093/IA/IIAA059.

35 S. Njeri, ‘Somaliland; the Viability of a Liberal Peacebuilding Critique beyond State Building, State Formation and Hybridity’, Peacebuilding 7, no. 1 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1080/21647259.2018.1469341; Ikpe and Njeri, ‘Landmine Clearance and Peacebuilding’; Jon D. Unruh and Mourad Shalaby, ‘A Volatile Interaction between Peacebuilding Priorities: Road Infrastructure (Re)Construction and Land Rights in Afghanistan’, Progress in Development Studies 12, no. 1 (January 2012): 47–61, https://doi.org/10.1177/146499341101200103; Unruh, ‘Eviction Policy in Postwar Angola’; and Unruh, ‘The Interaction between Landmine Clearance and Land Rights in Angola: A Volatile Outcome of Non-Integrated Peacebuilding’, 2012.

36 Preparing the Ground for Peace; Mine Action in Support of Peacebuilding (Oslo: International Peace Research Institute, 2004).

37 J.D. Unruh, N.C. Heynen, and P. Hossler, ‘The Political Ecology of Recovery from Armed Conflict: The Case of Landmines in Mozambique’, Political Geography 22, no. 8 (2003): 841–61.

38 Ruth Bottomley, ‘Community Participation in Mine Action: A Review and Conceptual Framework’, Global CWD Repository, 2005, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/214170141.pdf.

39 Jon D. Unruh, ‘The Interaction between Landmine Clearance and Land Rights in Angola: A Volatile Outcome of Non-Integrated Peacebuilding’, Habitat International 36, no. 1 (January 1, 2012): 117–25, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2011.06.008.

40 GICHD and UNDP, Leaving No One Behind: Mine Action and the Sustainable Development Goals (Geneva: GICHD and UNDP, 2017).

41 Iborra et al., The Socio- Economic Impact of Anti-Vehicle Mines in Angola.

42 UNOPS, ‘Infrastructure and Peacebuilding; The Role of Infrastructure in Building and Sustaining Peace’, Online: United Nations Office for Project Services, 2020, https://www.un.org/peacebuilding/sites/www.un.org.peacebuilding/files/pbso_sustaining_peace_-_infrastructure_for_peace.pdf.

43 J. Bachmann and P. Schouten, ‘Concrete Approaches to Peace: Infrastructure as Peacebuilding’, International Affairs 94, no. 2 (2018): 381–98.

44 Ikpe and Njeri, ‘Landmine Clearance and Peacebuilding’.

45 Sharmala Naidoo, ‘Mission Creep or Responding to Wider Security Needs? The Evolving Role of Mine Action Organisations in Armed Violence Reduction’, Stability: International Journal of Security and Development 2, no. 1 (2013).

46 The noted aims of release of land that is deemed safe and ‘sufficiently’ clear of explosive devices, in this case anti-personnel (AP) and anti-vehicle mines (AVMs) is linked to infrastructure-related SDGs from the SDGs-Mine Clearance Framework.

47 This is shows in greater detail in Ikpe and Njeri (2022) where the MPS Framework relies on combining economic and physical reconstruction, as constituent parts of long-term peacebuilding from the Humanitarian Peacebuilding Palette; connections between infrastructure-related SDGs to clearance from the Mine Action-SDGs Framework and; the materiality of peacebuilding through infrastructure from the Infrastructure as Peacebuilding Framework.

48 K. Jennings et al., Peacebuilding & Humanitarian Mine Action: Strategic Possibilities and Local Practicalities (Oslo; London: Fafo Institute for Applied International Studies and Landmine Action UK, 2008); GICHD and UNDP, Leaving No One Behind: Mine Action and the Sustainable Development Goals; Bachmann and Schouten, ‘Concrete Approaches to Peace: Infrastructure as Peacebuilding’; and Ikpe and Njeri, ‘Landmine Clearance and Peacebuilding’.

49 K.B. Harpviken and B.A. Skaešra, ‘Humanitarian Mine Action and Peace Building: Exploring the Relationship’, Third World Quarterly 24, no. 5 (2003): 809–22; Sarah Njeri, ‘The Politics of Non-Recognition: Re-Evaluating the Apolitical Presentation of the UN Humanitarian Mine Action Programs in Somaliland’, in Global Activism and Humanitarian Disarmament (Springer International Publishing, 2020), 169–95, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27611-9_6; Unruh, ‘The Interaction between Landmine Clearance and Land Rights in Angola: A Volatile Outcome of Non-Integrated Peacebuilding’, 2012; and D. Simangan and R. Gidley, ‘Exploring the Link between Mine Action and Transitional Justice in Cambodia’, Global Change, Peace & Security 31, no. 2 (2019): 221–43.

50 Jenny Clover, ‘Land Reform in Angola: Establishing the Ground Rules’, in From the Ground Up: Land Rights, Conflict and Peace in Sub-Saharan Africa, ed. Chris Huggins and Jenny Clover, 2005, 347–80; and Cain, ‘Angola: Land Resources and Conflict’.

51 ‘The Interaction between Landmine Clearance and Land Rights in Angola: A Volatile Outcome of Non-Integrated Peacebuilding’, January 1, 2012.

52 Unruh and Shalaby, ‘A Volatile Interaction between Peacebuilding Priorities: Road Infrastructure (Re)Construction and Land Rights in Afghanistan’.

53 The Angolan government, with assistance from the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Assistance (UN OCHA), attempted to incorporate into law a set of principles protecting the rights of IDPs. To encourage the return of IDPs to their areas of origin, they enacted a law that guaranteed them minimal standards of social infrastructure and basic land access and support the settlement process. Mass return created conditions that the government was unable to maintain.

54 S Fukuda-Parr and D. Mcneill, ‘Knowledge and Politics in Setting and Measuring the SDGs: Introduction to Special Issue’, Global Policy 10, no. S1 (n.d.): 5–15; and H. Weber, ‘Politics of “Leaving No One Behind”: Contesting the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals Agenda’, Globalizations 14, no. 3 (2017): 399–414.

55 This followed ethical approval processes of the host research institution, Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining, including seeking and establishing informed consent from all participants.

56 Landmine Monitor, Landmine Monitor 2010 (Washington, D.C: International Campaign to Ban Landmines and Mines Action Canada, 2010), https://www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2020/landmine-monitor-2020.aspx.

57 Alex Vines, ‘UK Must Show Leadership on Landmine Clearance in Angola’, The Guardian, March 23, 2018, sec. World news, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/mar/23/uk-must-show-leadership-on-landmine-clearance-in-angola.

58 Mine contamination in Cuando-Cubango is one of the obstacles to creating the new Kavango Zambezi Trans frontier Conservation Area,on the borders of Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe where more than 130,000 elephants are waiting to be allowed to move from Botswana through the park (Landmine Monitor 2010).

59 Christopher Vandome, ‘Mine Action in Angola: Clearing the Legacies of Conflict to Harness the Potential of Peace’, 2019.

60 Interview with CNIDAH representative, Cuando Cubango, 29 July 2019.

61 João Gomes Porto, Imogen Parsons, and Chris Alden, From Soldiers to Citizens: The Social, Economic and Political Reintegration of Unita Ex-Combatants, 2007; and IRIN, ‘Angola: Reconstructing the Breadbasket of Huambo – Angola | ReliefWeb’, The New Humanitarian, 2006, https://reliefweb.int/report/angola/angola-reconstructing-breadbasket-huambo.

62 FGD, first village H400, 21 July 2019; FGD Liambambi, Huambo, 22 July 2019; site visit observations 21–24 July 2019; and Interview Directorate of Agricultural Department, Huambo, 23 July 2019

63 Interview ADRA, Huambo 23 July 2019.

64 Elliot, ‘Mozambique: Development through De‐mining’; B Gildestad, ‘Cost-Benefit Analysis of Mine Clearance Operations in Cambodia’, n.d.; and Unruh, ‘Eviction Policy in Postwar Angola’.

65 MAG (UK), ‘Time to Change Course: Angola and The Ottawa Treaty’.

66 Interview Directorate of Agricultural Department, Huambo, 23 July 2019.

67 Interview with INAD, Luanda, 24 July 2019.

68 FGD, first village H400, 21 July 2019; FGD Liambambi, Huambo, 22 July 2019; site visit observations 21–24 July 2019; and Interview Directorate of Agricultural Department, Huambo, 23 July 2019

69 Ibid.

70 Interview with the Ministry of Agriculture, Cuando Cubango, 29 July 2019.

71 See note 61 above.

72 Ibid.

73 Interview with Vice Governor, Huambo Province, Huambo, 23 July 2019.

74 Interview with National Demining Institute (Instituto Nacional de Desminagem, INAD), Luanda, 24 July 2019.

75 Interview with the Ministry of Trade and Industry, Cuando Cubango, 30 July 2019.

76 See note 68 above.

77 FGD Shipopa, Cuando Cubango, Cuito Cuinavale municipality,31 July 2019.

78 See note 73 above.

79 FGD Liambambi, Huambo, 22 July 2019.

80 FGD, first village H400, 21 July 2019.

81 FGD Liambambi, Huambo, 22 July 2019; and Interview Directorate of Agricultural Department, Huambo, 23 July 2019.

82 Ikpe and Njeri, ‘Landmine Clearance and Peacebuilding’; and T Paterson et al., Evaluation of EC-Funded Mine Action Programmes in Africa Geneva (Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining, n.d.).

83 FGD Cuatili village, Cuando Cubango, Menongue municipality, 2 August 2019.

84 Natalia Limones et al., ‘Evaluating Drought Risk in Data-Scarce Contexts. The Case of Southern Angola’, Journal of Water and Climate Change 11, no. S1 (November 2, 2020): 44–67, https://doi.org/10.2166/wcc.2020.101.

85 Interview with Representative from Development Workshop, Huambo, 23 July 2019.

86 See note 64 above.

87 See note 73 above.

88 Ministry of Planning and Territorial Development (Angola) (2012) Plano Nacional de Desenvolvimento 2013–2017.

89 Ministry of Economy and Planning (Angola) (2018) Plano Nacional de Desenvolvimento 2018–2022

90 See note 71 above.

91 ‘Drivers for Change: An Overview’ (London, Chatham House, 2005).

92 See note 71 above.

93 Interview with Deputy Director, Railways, 29 July 2019, Menongue, Cuando Cubango.

94 Interview with Ministry of Youth, Culture and Tourism, Cuando Cubango 30 July 2019.

95 AID DATA LAB, ‘China Eximbank Provides $362 Million Loan for 1,344 Km Benguela Railway Rehabilitation Project’, china.aiddata.org, 2021, https://china.aiddata.org/projects/39153/; and D. White, ‘Infrastructure: Benguela Railway Transformed by Loans from Beijing’, financial Times, 2012, https://www.ft.com/content/cdb78d52-c6b9-11e1-95ea-00144feabdc0.

96 Ibid.

97 Interview with Railway Corporation, Huambo, 23 July 2019.

98 Ibid.

99 Interview with Ministry of Transport, Cuando Cubango, 30 July 2019.

100 Interview with CNIDAH Officer, Cuando Cubango, 29 July 2019.

101 Søren Kirk Jensen, ‘Angola’s Infrastructure Ambitions Through Booms and Busts Policy, Governance and Reform’ (Chatham House Research Paper, 2018).

102 Kristian Berg Harpviken et al., ‘Measures for Mines: Approaches to Impact Assessment in Humanitarian Mine Action’, Third World Quarterly 24, no. 5 (October 2003): 889–908, https://doi.org/10.1080/0143659032000132911.

103 Søren Kirk Jensen, ‘Angola’s Infrastructure Ambitions Through Booms and Busts’, London, Chatham House: Chatham House, 2018, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2018-09-14-angola-infrastructure-ambitions-kirk-jensen-final.pdf.

104 See note 98 above.

105 See note 73 above.

106 Interview with Market Traders in Menongue market, Menongue 2 August 2019.

107 Interview with INAD, Luanda, 24 July 2019; and Interview with Vice Governor, Huambo Province, Huambo, 23 July 2019.

108 See note 71 above.

109 FGD Liambambi, Huambo, 22 July 2019; and Interview with Vice Governor, Huambo Province, Huambo, 23 July 2019.

110 Interview with Vice Governor, Huambo Province, Huambo, 23 July 2019 and Author observations of new infrastructure 22 July 2019.

111 See note 77 above.

112 See for example Unruh and Shalaby, ‘A Volatile Interaction between Peacebuilding Priorities: Road Infrastructure (Re)Construction and Land Rights in Afghanistan’.

113 See note 81 above.

114 Ibid.

115 Interview with MENTOR Initiative Menongue, 29 July 2019.

116 See note 61 above.

117 World Bank, ‘World Development Indicators | DataBank’, 2023, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

118 Interview with CNIDAH, Huambo, 22 July 2019.