A picture held us captive. And we could not get outside it, for it lay in our language and language seemed to repeat it to us inexorably. – Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, 115.

Klimt, an Art Nouveau painter, was one of the most important founders of the Vienna Secession in 1897, a group so called because of its collective resignation from the Association of Austrian Artists initiating an ascetic break with the conservatism of the Vienna Künstlerhaus with its uncritical orientation toward historicism. The words ‘To every age its art. To every art its freedom’ (‘Der Zeit ihre Kunst. Der Kunst ihre Freiheit)’ were hung above the entrance to headquarters. They tried to create a style that owed nothing to historical reference and tradition. Their break with tradition in art and architecture was part of fin de siècle Vienna that was characterized by the influence of Nietzsche and the work of Freud, Mach, Buber, and Wittgenstein. It was a time when the ordered cosmos of the Austro-Hungarian empire fell apart, haunting artists and philosophers alike, comprising a widely diverse group that included Mahler, Schönberg, Berg, Webern, Musil, von Hofmannsthal, Schnitzler, Kafka, alongside Adolf Loos and Ludwig Wittgenstein (Johnson, Citation1983; Schorske, Citation1980; Toulmin & Janik, Citation1973). Vienna became the cradle of modernism and fascism, liberalism and totalitarianism shaping Western philosophy, art and politics.

At the same time the first film technology of moving images was developing in Britain and France although camera obscura had been used since the early Renaissance as a drawing and painting aid. The first motion picture was developed in the 1880s by Louis Le Prince that led to commercialization soon after and later digital film. Wittgenstein’s (Citation1953) notion that a picture held us captive was much more an acknowledgement that pictures hold us captive rather than arguments and that if this is the case arguments have limited efficacy in getting people to change their mind. Wittgenstein wanted to liberate us from a view of modern philosophy as certain foundations and accurate representations but he did not want offer another metaphysics to replace Cartesian worldview. Rather for Descartes’ epistemology Wittgenstein sidesteps metaphysics by moving to language and philosophical grammar to talk of a non-Cartesian world view (Weltbild) consisting of unveriable forms of life and non-representational language. Thus Wittgenstein introduces a new way of thinking in order to change our way of seeing. This is a particular understanding of Weltanschuung (worldview) and Weltbild that Wittgenstein was interested in shifting our modern conception of the world. His aim ‘To shew the fly the way out of the fly-bottle’ could not be pursued by the methods of modern philosophy based on logic and forms of argumentation. In On Certainty, Wittgenstein turns to a meta-consideration of world-pictures where his pluralism consist in epistemically unjustified forms of life and language games within which people construct their worldviews. A Weltbild is not chosen but rather culturally inherited and it functions like a governing mythology – basically different conceptual schema, frameworks, or paradigms – which require understanding in terms of pictures (Naugle, Citation2002), that is, in aesthetic terms closer to art than philosophy.

De-stablising pre-existing assertions of object-subject relationships this ‘philosophy of the image’ has opened up a new era for understanding the nature of meaning itself which was to be pursued later in poststructuralist thought. But, like all philosophies, this is by no means an endpoint. Breaking through this discourse in the twenty-first century a new ‘kid on the block’ has now taken central stage – in the guise of the literal moving image. His narrative is yet to be told which might seem odd since the first moving image was born over a century ago; but the extent to which this dynamic stranger alters the way we might think about the subject (if indeed there is any longer a single subject) presents a new threshold for philosophy. In contemplating the moving image it seems impossible, and frankly naïve, to ignore its location or its profound affect in and across popular culture (and beyond). No longer harnessed within the static canvas, or accountable to a holy God (whom his predecessors fought to break free from), the moving image resides within the complex networked society of the internet and social media in what has recently been described as a ‘post-truth era’ of civilization (Peters, Citation2017). As such its technologies are accessible to consumers who now become producers (or artists?) capable of creating complex combinations of image and text that represent a hybrid formation of what has gone before and generated new forms of aesthetic. Taken together – the moving image and its obscured movement in cyber space, with joined up communities who are consumer-creators – a new philosophical epoch may be upon us already. It is the intention of this article to start to explore this epoch through a series of invited responses to a set of ten theses which, we think, have the potential to bring new realms of wisdom to the twenty-first century.

In this exodus there are many promising avenues that might be taken in promulgating a philosophy of the (moving) image. The generation of new spectator theories of knowledge, optical theories of truth and a pedagogy of the senses which enjoins the eye and ear as opposed to smell, taste and touch (although we say this with caution since new technologies are now bringing these to bear on the moving image also) are some promising avenues to explore. The rise of the body – now well beyond any Cartesian split but gaining momentum in its presence in the moving image – has much to offer; as do ocular pedagogies (including the important status of ‘the gaze’). New technologies and affordances – not least virtual reality and augmented reality – are yet to be fully pursued. The shifts that are heralded in thought and action, not least in the capacity of the moving image to convey messages more efficiently and, perhaps, more powerfully, warrant attention, as do their capacity to transform and critique (and conversely, to disguise and deceive).

The list of possibilities goes on. For example, a genealogy might reveal the ways in which historical philosophies give rise to this new philosophical era. In particular, poststructuralist theories may have an opportunity to re-assert themselves through contemplation of the moving image, and perhaps even move beyond themselves to reconcile the tangled webs that they weave. Similarly, semiotics will likely have something to say on this subject, since it is clear that there the movement of signs and symbols is not merely a novelty, but represents a new ‘reading’ of the world. It is likely that these and other dominant philosophies may have to make room for new and emerging ones, and it is to a beginning examination of these we now turn.

In the spirit of Wittgenstein we present ten theses for a philosophy of the moving image as a starting place for what follows.

The concept of text and textuality are deeply embedded in the practices of education and the humanities since the invention of writing as ‘mark-making’. Models of textual analysis abound and structure our disciplinary practices. Linguistics, lingusitic philosophy, semiotics, hermeneutics and psychoanalysis constitute the main forms of textual analysis and critical reading in the humanities. By contrast, ways of critically examining the image have lagged behind these textual methodologies. Outside of art history and films studies there are few accepted methodologies for analysing the image or for recognizing its role and importance in visual culture. Since we are now not only contemplating the static image in relation to text, it is to the notion of the moving image that we now seek inspiration also.

The text is still the ruling cultural and academic paradigm. Textual analogues define consciousness, the mind, the unconscious, society, and culture. Science is comprised of discourses and we are presented with text-based understandings of reality that call upon the subject to navigate between text and life. To this day knowledge is predominantly text-based and exchanged, stored and retrieved in texts of this nature. The text dominates our ways of thinking and interpreting the world in philosophical thought. Education is primarily rule by the text – at least in traditional realms of inquiry.

The shift from text to image defines our visual culture. This migration from the text to the image is enhanced through new digital technologies. One marketing expert notes that ‘Between Facebook, Instagram and Tumblr, consumers share nearly 5000 images every second of every day. Add in Pinterest's estimated 40 million users and even SnapChat's meteoric rise, and it's clear, a shift is afoot – a desire to share what matters most in pictures rather than words.’[1] This increasing density of images constitute the new visual web and builds on earlier discussions of visual media by the likes of Innes (Citation1951), McLuhan (Citation1964) and Baudrillard (Citation1994).

Rorty (Citation1979) discusses the ancient conceit that the mind has an eye with which it inspects the mirror to argue that the notion of knowledge as accurate representation is optional and arbitrary. That it is static and therefore retrievable by all has marked the dominance of rationalism and received truth over many decades. Philosophy has for too long been dominated by Greek ocular metaphors that makes a separation between contemplation and action – the seen in the absence of the see-er (Bakhtin, Citation1990). While Bakhtin seeks to exploit the surplus of seeing offered by ‘other’; Rorty wants to replaces this vocabulary with a pragmatist conception that eliminates this contrast, arguing a historical epoch dominated by Greek ocular metaphors may, we suggest, yield to one in which the philosophical vocabulary incorporating these metaphors seems as quaint as the animistic vocabulary of pre-classical.

In Downcast Eyes Jay (Citation1993) demonstrates the ubiquity of visual metaphors that permeate Western languages often in occluded and dormant forms and imbue our cultural and social practices. He comments that exosomatic technologies (the telescope and microscope) have extended the scope and range of vision to encourage an ocular-centric science. And he cites the philosopher Mark Wartofsky who provides a radical cultural reading of vision arguing all perception is a result of changes in representation. Jay's argument is that contemporary French thought is ‘imbued with a profound suspicion of vision and its hegemonic role in the modern era’ (p. 14).

The pervasiveness of metaphors of light and sight in classical Greek works can be readily seen in Homer (Tarrant, Citation1960) and Plato who uses the sun as a metaphor for ‘illumination’ and indicates that the eye is peculiar among sense organs in that it needs light to operate. The classical Greeks have been called ‘people of the eye’ because they favoured the visual sense that extended to their most fundamental concepts such as the distinction between knowing (being seen) and contemplation. It is thus to notions of the ‘self’ and its (now) collective orientation in an era of the moving image, that we turn. As Burri (Citation2012) reminds us, we need a new logic to explain ‘the self’ in contemplation of ‘the social’; and a new materiality of images that grants them such presence in the social milieu.

Heidegger was influential in providing an account of the metaphysics underlying Greek philosophy in terms of vision and visibility. As Backman (Citation2015) explains Heidegger's account of Western metaphysics ‘is rooted in a metaphysics of presence’ (p. 16). Being means presence and ‘seeing’ is a means of grasping what is there to paraphrase Heidegger. Backman explains: ‘Seeing is the paradigmatic metaphysical sense because it affords a particular kind of access to being as present’ (p. 16). In an era of social media such access is unfathomable.

Rorty (Citation1979, p. 263) describes the history of philosophy as a progressive series of problematics, or ‘turns,’ beginning with medieval philosophy and its concern for things, enlightenment philosophy and the concern for ideas, and last, contemporary philosophy – the so-called linguistic turn – and its concern for words. We might hypothesize the next shift from words to moving images while at the same time as signalling the incapacity of modern philosophy and education to cope with this shift and an unprecedented emphasis on the emerging new power relationships between seeing and being seen that exceed Debord’s (Citation1970) earlier emphasis on the spectacle and moves us to the orienting role of image in an era of social innovation.

The semiotic landscape infused with moving images is the basis for visual culture and the younger generation seem both more attracted to and more adept at engaging with visual media that replaces word and print as the central information medium. Popular culture is on the rise in this domain, as are trends towards performance, satire and ‘post-truth’ that blur conventions of reality in the service of modern technologies that provide forum for the exploitation of manipulation and the unleashing of unmasked creativity. From an educational standpoint, however, learners need to learn how to ‘read’ and ‘engage’ with the un-real, and to become critical participants in this new socially networked society with so much potential, and so much risk. As Peters (Citation2010) asks ‘can the dominance of the image over text really deliver on the promise of a critical approach to pedagogy?’ (p. 46).

The ‘pictorial turn’ is already upon us: ‘A picture holds us captive’ (Wittgenstein, Citation1953). Investigating the later Wittgenstein on visual argumentation Patterson (Citation2010) writes ‘although visual images may occur as elements of argumentation, broadly conceived, it is a mistake to think that there are purely visual arguments or, for that matter, that existing arguments are adequate for this new era of thought, in the sense of illative moves from premises to conclusions that are conveyed by images alone, without the support or framing of words.’ In this statement is the seed for an educational philosophy of the moving image.

The 7 responses that follow deal with the (moving) image in two central ways. Firstly, by examining the capacity of the image to ‘move’ in an educational sense; and secondly by contemplating the additional insights brought forth by moving technologies – not least the rise of video and, more recently, virtual reality; but also in consideration of its movement in social media. The entries are responded to and summarized in our final entry by Kirsten Locke, who sets a provocative agenda in orienting possible futures for educational philosophy based on ‘doing-what-you-can't’. Taken together they respond to the ten theses in various interesting ways that begin to orient what we have called ‘A philosophy of the (moving) image’.

The authors would like to acknowledge University of Waikato for generous funding and leave that enabled the Jayne White to spend many hours exploring these ideas on study leave periods during 2014 and 2017; and Michael Peters to attend the University of Lausanne to present an invited paper entitled ‘Wittgenstein's Trials, Teaching and Cavell's Romantic ‘Figure of the Child’’ at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RnCFOFIr6eQ.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Increasingly cyberspace networks are generating a diet of images in everyday and working lives. Social media sites are proliferating images as identity markers for co-creation, titillation, exploitation or other instant affects. How education approaches this arena is open to further revision in light of the politics of the image. The following reflection on the image goes some way towards articulating a theory of the image.

I begin with a proposition, images do not need the framing of words to activate them. By refusing the ‘othering’ that textual dominance places upon them, images call to be understood in their own terms. But what is meant by ‘their own terms’? A narrative may work towards some clarification.

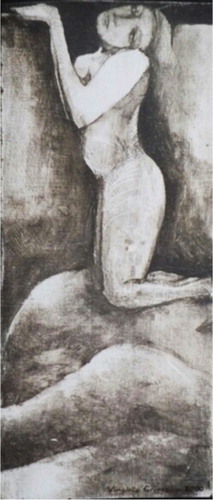

In November 1953, the French-born, New Zealand based artist Louise Henderson, later Dame Louise, was visited in her Auckland studio by art critic Anthony Alpers to view her new paintings for a forthcoming solo exhibition at the Auckland Art Gallery. A large cubist nude, The Blue Bird invited the critic's opprobrium. Given that Louise Henderson had spent a year painting in the cubist idiom at the Metzinger studio in Paris, she regarded any criticisms of her images in New Zealand as a challenge to be overcome, not through textual or linguistic dialogue, or emotive persuasion, but through imagistic solutions. Rather than attract or escalate pernicious commentary from a prudish New Zealand public, Henderson ‘clothed’ her nude with a diaphanous blue dress. Of her painterly response executed through the logic of faceted form, the artist said in interview, ‘I have never dressed a cubist nude before’ (cited in Grierson, Citation1990). Henderson duly exhibited her cubist paintings and the New Zealand artist Colin McCahon reviewing the exhibition, condemned it with faint praise: ‘these paintings may surprise you, perhaps even shock you, but given a chance to reveal themselves they do not have a lot to tell you’ (McCahon, Citation1954). In fact, Henderson's paintings had a great deal to tell for those who had the capacity to look at an image beyond an uncritical and patriarchal viewpoint of pictorial and social norms. Henderson refused any ‘othering’ of herself or her work, and she certainly refused any othering of her imagistic approach to the female form. Herein lies the point of departure for an educational philosophy of the image.

The history of art is replete with images of the female as muse or as object of desire – this, the image as a social or political construct. Any thesis of the image as central to the ‘pictorial turn’ for education, and the philosophy of education, calls for more than a passing reference to decades of feminist analysis of the image as a contentious site. Feminist artists and scholars successfully disturbed the positioning of the female nude as signifier of a certain rational logic of gendered and racialised unity and order. Lynda Nead showed how this rational unity and order contributes to ‘a discourse on the subject and is at the core of the history of western aesthetics’ (Nead, Citation1992, p. 2).

Nead's study of the framing of the female nude in Western art shows how the female nude became synonymous with art itself. Importantly she showed how the politics of production and consumption determined the norms of sexuality and objectification. Viewing and reception of the nude was, and is, embedded in social history and bound up with power relations. Throughout the Enlightenment and into the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the passivity of the female nude worked to reinforce the logic of integrity and unity of the aesthetic object of contemplation. All was in order in such a universe, until unsettled by feminist scholars of art history from the revisionist decades of the 1970s to 1990s. Perhaps the most important contributions to understanding the power and potency of images came from the work of feminist critics such as Griselda Pollock (Citation1988, Citation1996, Citation1999), and earlier writings of Lippard (Citation1976, Citation1983), Petersen and Wilson (Citation1979), Fine (Citation1978), Parker and Pollock (Citation1981), Harris and Nochlin (Citation1981), Broude and Garrard (Citation1982). These scholars questioned the received litany of art and its history and opened the disciplinary territory of image production and reception to reconstructive analyses. Their scholarly interventions made visible the mechanisms of power relations throughout histories of image making, production and reception. They achieved their critically incisive analyses by disturbing normative visual narratives of gender, sexuality and racialization.

From the ‘linguistic turn’ to the ‘cultural turn’ to the ‘pictorial turn’ such revisionist approaches to image analysis soon informed the realm of media and visual studies. The transference of textual analysis to visuality was shown to be a first-principle error, notwithstanding that studies of the image under the rubric of cultural studies holds an indebtedness to semiotics as shown by Evans and Hall (Citation1999).

Yet, in spite of the focus of images in visual studies since the 1970s, and in spite of the proliferation of images in the digitally connected lives of cyberspace today, how little attention is devoted to critical examination of images in general settings of education.

Mitchell (Citation1994) reminded us that although the exact nature of images is uncertain, the picture brings into play a complex and contingent field of interconnections. Mitchell warns against employing textual methods in image analysis. It is to the image itself we must turn. Mitchell considers the way registers of meanings operate in the visual field. But the field, as such, is not to be regarded in isolation. It is implicated already by other forces, such as the technologies of production and circulation, social-relations, bodies (spectatorship) and figurality (figuring the world).

Without imposing textual methods of analysis, the question remains: how may a viewer make meaning from an image? How are images to be approached, considered, discussed, positioned without textual aids? Current curatorial practice in art museums is to add exhibition notes beside images or at the entrance of gallery rooms. For viewers, these notes are helpful in an explanatory way, by categorising images historically, socially, even politically.

However, images also stand alone. Consider this image for example.Footnote1 How does the viewer access its domain of aesthetics, its domain of meaning? A date and signature is the only textual reference, but this has nothing to do with any nuance of the image. The image itself inhabits a contingent space of meaning and implication.

Questions arise from this image with its body in a confined pictorial space. Where is she? Why the fettered space? To find indicators of subject matter we might turn to ‘other forces’ that Mitchell talks of in his theory of the image (Mitchell, Citation1994). With regard to images of the body, one of the relevant forces is the power of normalisation. In histories of the image the female nude was normalised by its passive sexuality and availability to the power of the male gaze. But here, in this image, as in the work of German artist, Paula Modersohn-Becker, as discussed by Perry (Citation1979), the nude holds a dignity that comes with reclamation of the female body. The image has its own internal logic. There is a felt reality for the body in its enframed environment, and perhaps herein lies its aesthetic or cultural powers.

Challenges presented by the image, as shown here, go well beyond solely textual semiotics. Yet a contingency remains, and in this contingency a theory of the image may be found. Images are never neutral. The thrust of interventionist approaches to the image from feminist scholarship disturbed any assumed neutrality.

But an on-going difficulty lies here. If it is found that the image does need the framing of text to explain it, then arguably it would mean that visuality cannot exist on its own terms. Yet, if the image has the capacity to ‘speak’ to its cultural and social mores (setting) on its own terms, then it has a life beyond textual framing. As the female body reclaims its pictorial space, the image is activated by, and activates, forces of production and consumption. This politic is relevant at the time of the image's inception as much as at the time of its later reception. An outcome flowing from this discussion might be that a theory of the image needs to take account of these contingent perspectives as it considers the intervention of feminist scholarship.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Broude, N., & Garard, M. D. (Eds.). (1982). Feminism and art history: Questioning the litany. New York: Harper & Row.

- Evans, J., & Hall, S. (1999). Visual culture: The reader. London: Sage Publications in association with The Open University.

- Fine, E. H. (1978). Women and Art: A history of women painters and sculptors from the Renaissance to the 20th century. New Jersey: Allanheld and Schram.

- Grierson, E. M. (1990). The art of Louise Henderson, Master of Arts thesis, University of Auckland.

- Harris, A. S., & Nochlin, L. (1981). Women artists 1550–1950. New York: Alfred Knopf and Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

- Lippard, L. (1976). From the center: Feminist essays on women’s art. Toronto: Clarke, Irwin & Co. Ltd.

- Lippard, L. (1983). Overlay, contemporary art and the art of prehistory. New York: Pantheon.

- McCahon, C. (1954, February 1). Louise Henderson: Colin McCahon discusses the painter’s work which was recently exhibited in Auckland. Home and Building.

- Mitchell, W. J. T. (1994). Picture theory: Essays on verbal and visual representation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Nead, L. (1992). The female nude: Art, obscenity and sexuality. London: Routledge.

- Parker, R., & Pollock, G. (1981). Old mistresses: Women, art and ideology. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Perry, G. (1979). Paula Modersohn-Becker, her life and work. London: The Women’s Press.

- Petersen, K., & Wilson, J. J. (1979). Women artists: Recognition and reappraisal from the early middle ages to the twentieth century. London: The Women’s Press.

- Pollock, G. (1988). Vision and difference, femininity, feminism and the histories of art. London: Routledge.

- Pollock, G. (1996). Generations and geographies in the visual arts: Feminist readings. London: Routledge.

- Pollock, G. (1999). Differencing the Canon: Feminist desire and the writing of art’s histories. London: Routledge.

I want to reflect, from the perspective of a Māori teacher and researcher, on what it means to write for the video journal (VJEP, the Video Journal of Education and Pedagogy). This new Springer journal provides authors with the facility to embed video clips and combine them with text in a new form of online journal ‘article’ that pushes the boundaries of what is currently accepted as ‘scholarship’ in the discipline of Education, and adjacent fields of study. Scholarship implies the non-fictional written word, and numerical/graphical representations. In education, it is still ‘risque’ to incorporate into research the use of creative forms of writing such as poetry, fiction, narrative, autobiography and auto-ethnography. How much more edgy, then, is the use of video footage in research articles!

Yet what does this facility actually afford that is meaningful in an essential research sense, i.e. in epistemological terms? Does video research represent a new paradigm, or just a novel tool for the same old kind of research and scholarship? Why might one choose the video journal (VJEP) as a publication venue for one's work? How does this scholarship stand in relation to traditional articles? How might postgraduate students respond if I include VJEP articles as course readings? I will consider these questions in the light of my experience preparing an article for the video journal.

When I first received the email from the editors suggesting I write a video journal article about my recent research, I immediately rejected the idea. I could understand why the request came, since a few weeks earlier, I had presented at the PESA Conference 2016 held in Coral Coast Fiji, speaking about my work on the history and meanings of the controversy over the old school journal Washday at the Pā (Westra, Citation1964). This had proved a fruitful topic, with one article published and another on the way (Stewart, Citation2017, in review; Stewart & Dale, Citation2016). It was also a labour of love as the Washday story had long ago captured me, since 2010 when I started teaching it as part of the Huarahi Māori initial teacher education programme at the campus in Whangarei. In Fiji the conference presentation mode had given me licence to exploit the visual power of Westra's magnificent oeuvre of photographs of Māori, but I rejected on principle the idea that I could use that imagery in a journal article.

On reflection, after initially declining the approach from the journal editors, I considered the fact that a book is ‘made for reading’ so to speak, and that reading and talking about a book like Washday is a pedagogical and social activity that is captured far more adequately in video form rather than by a traditional written journal article. The fact that I own a copy of the original book, which survived the recall in 1964 and passed into my hands a few years ago, added to the motivation. A dialogue with my colleague Hēmi Dale, who is the course owner and teaches Washday at the Epsom campus, provided an authentic scenario with pedagogical heft, which seemed to me ideal for the video journal. It came naturally for us to speak in te reo Māori, since Te Huarahi Māori is a Māori medium teaching degree. I had previously registered that a video journal is an ideal vehicle for indigenous oral traditions, but this hypothetical insight had yet to translate into a concrete idea for a paper. To add te reo Māori and bilingualism into the mix clinched for me a rationale for taking on a video journal article about the Washday story.

I conceived of the video journal article as a ‘layered text’ as Rath (Citation2012) described in relation to autoethnography. For me, the layered text idea also applies in other complex educational scenarios, including indigenous education and Kaupapa Māori research. A video journal article is by definition a layered text, since it contains both video and written elements. I began to think about possible video clips and how to use them in such an article. Hēmi mentioned the existence of a documentary about Westra that sounded likely as a source of video clips to use in the place of written quotes (Luit Bieringa (Director) & Jan Bieringa (Producer), Citation2017).

To prepare the article required me to re-think the very idea of a journal article. I decided to start by making the video clips and build the article around them. Video is an amazing affordance and useful for more than a ‘talking book’ or ‘talking heads’ mode. A ‘video clip’ in a journal article can be of several kinds, though these fall into two categories, namely extracts from pre-existing video, and self-recorded footage. Clips from pre-existing video sources are somewhat like conventional written quotes, and I decided to use them as such, with text to unpack them and link them into the narrative of my article.

Self-recorded footage can vary from professional video lab productions to a recording made ‘in the field’ on a smartphone. In the spirit of the latter, I recorded a conversation with Hēmi in which we read and talked about the book in both Māori and English. Then I had to acquire video editing software and learn how to use it to extract the clips to use in the article. The other main kind of self-recorded footage is somewhat like a recorded lecture using a montage of still or moving images with a voice-over audio track. This kind of clip allows me to present selections from the rich archive related to the Washday story.

The final hurdle to overcome is the matter of permissions for pre-recorded video and the use of still images. There is information about permissions on the journal homepage, and I received copious more from the publisher and my IT service at work, but in the way of this kind of ‘information’ none of it clarified what I needed to do! Of course as a university researcher, I have the resources and expertise available to work through these sorts of challenges.

I have articulated how I thought about devising a novel kind of journal article, basing my decisions in logic and in relation to existing standards of scholarship and methodology, including Kaupapa Māori research. Authoring a video article was an interesting challenge, both intellectually and practically, which leads me to believe that the strength of a video journal article depends on the fit between the topic and the vehicle. It is necessary to get beyond the novelty value of video in academic work in order to mine its pedagogical value.

My video response is obviously (deliberately) homemade: recorded in my room, on my smartphone, while my family watched TV next door. I had Adobe Premier Pro (video editing software) installed on my laptop a week or so before I recorded my response, and when I had uploaded the footage I trimmed it and overlaid some powerpoint slides and illustrations. In the brave new world of video journals, we must learn to write with our new tools. This video response is like my first attempt to write: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x9N9mdIs85c&t=7s.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Bieringa, L. (Director), & Bieringa, J. (Producer). (2017). Ans Westra - Private Journeys / Public Signposts. Retrieved from https://www.nzonscreen.com/title/ans-westra-private-journeys-2006/background

- Rath, J. (2012). Autoethnographic layering: recollections, family tales, and dreams. Qualitative Inquiry, 18(5), 442–448. doi: 10.1177/1077800412439529

- Stewart, G. (2017, in review). Mana wahine and the Washday at the Pā affair. Educational Philosophy and Theory.

- Stewart, G., & Dale, H. (2016). ‘Dirty laundry’ in Māori education history? Another spin for Washday at the Pā. Waikato Journal of Education, 21(2), 5–15. doi: 10.15663/wje.v21i2.268

- Westra, A. (1964). Washday at the Pa (Rev. ed.). Christchurch: Caxton Press.

Text and image are no strangers to each other; they have a very long shared history with complex patternings that involve an interactive co-existence of the human and the technical; an ongoing evolving human- technology relation. The history of writing begins with attempts to depict images of the world, gradually refined into symbols for sounds and alphabetization. As sounds become images, the authority of the image of the sound, the text, is questioned. Recall how Plato disdained the written form of language, calling it ‘dead’ by comparison with spoken dialogue. There is then an evident problematic relationship between text and image in relation to the task of making sense of the world.

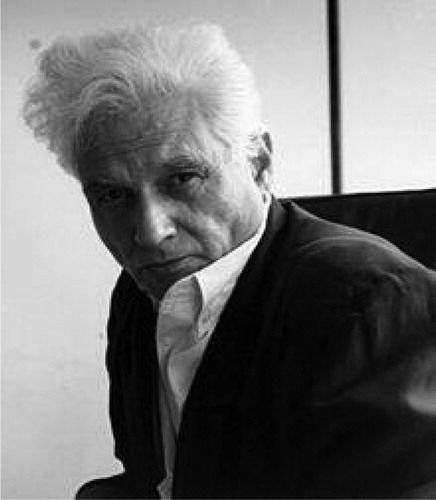

This is a problem recognized in the work of Jacques Derrida. Hence, in the spirit of Derrida's provocation that ‘there is nothing outside the text’ (Citation2016, p. 158), in this response we think about the ‘textiness’ of the image. In what ways does text penetrate the image such that the way in which one makes sense of an image is contained and restrained by and within the text? Is the image then no more or less a reality than the text?

The text holds an image together in some way. Images are not universally recognisable representations of reality. They draw on a literature, on a common bank of visual gestures, a language of image. This bank or language has been built up over centuries, goodness knows how long. While the bank might be common, part of a common world, it is a mistake to think that everyone reads these images alike: where Palagi (Westerner) see the pointed hand as indicating that something or someone is needed, or identified, to Samoans the pointed hand is an insult, an affront to human dignity. Neither are the techniques of image universal nor necessary to a language of imagery. For instance, perspective (in the sense of depth in representation) was unknown as a technique in Chinese traditions of drawing until introduced from the West, and the Chinese do not seem to have suffered unduly from the lack of it.

The plethora of visual images we see today can often be traced, just as text can, to their ‘genealogies’ of meaning. For the Gothic writers, it was the dark wood and the solitary heroine; for the Romantics it was the bright and beautiful young men and the unattainable heroine. The image is often a rendition of an existing literary image, which refers to a physical one: so the Guardian cartoonist uses the contemporary figures of Trump and May as his subject, but his images reference the Victorian political cartoonist John Tenniel and well-known phrases. Trump and May ‘in bed together’ is one (The Guardian, Citation2017), ‘dropping the Captain’ is another (Encyclopedia Britannica, Citation2017). The initial reference is to ‘being in bed together’ or to a steamer that has left port, allowing the pilot who has steered the ship of state through the shallows or rough waters to regain his lighter, but the reference to Tenniel's cartoons, or contemporary referents such as award-winning movies, also draws in another period of history or domain of popular culture, in so doing deriving a new and often sardonic layer of meaning. The longstanding sociocultural and political importance of imagery deserves recognition – especially the influence of television on the everyday lives of the last few generations (particularly in the West). Movies have been a hotbed of intercultural creativity, and film industries in small countries such as Aotearoa New Zealand operate quite differently from the conditions in Hollywood (Conor, Citation2004).

The postcard or greeting card and the political cartoon are socially important forms of visual text of long standing, which have evolved and remain relevant today, while morphing into new forms afforded by the internet. The recent flag debate in Aotearoa New Zealand is an example of a political struggle over a visual image that represents our national identity. In Aotearoa New Zealand, Māori have used flags to symbolise their distinct identity within the nation (New Zealand History, Citation2017). The sociopolitics of these images cannot be de- textualised because they are significant technologies through which society operates. Hence text and image are drawn together as technics. Humanity is ‘invented’ through technics. Technics are processes that make thought possible; thoughts are externalized through the technical prostheses of text and image (see for instance Stiegler, Citation2007, Citation2013). Thoughts, for example, memories, are externalised, in objects (e.g. statues, sculptures, paintings – and in rocks), through technics.

These kinds of human-technical relations can be understood in terms of the gesture (Agamben, Citation2007), an undertaking with supporting action [that] ‘opens the sphere of ethos as the most fitting sphere of the human’ (p. 154). Gesture, as movement, for Agamben, ‘breaks the false alternative between ends and means that paralyses morality and presents means which, as such, are removed from the sphere of mediation without thereby becoming ends’ (p. 155). The gesture offered here, as a display of mediation that makes visible the means (in, between text, image, and more than), and as such, is a composition, a multiplicity.

Rather than setting image – text – object in (any binary) opposition to each other, its useful to think about how such multiplicities might, with a nod to Stiegler, ‘compose one another, feed discernibly back into each other, and can therefore account for permanent oscillation between perception and imagination’ (Sabisch, Citation2011, p. 185). For this reason, questioning beyond a binary of text and image involves attention to the exteriority and materiality of processes of image and text making.

While it is imperative to acknowledge this binary, or even examine why and how it might be used, such binaries are attributed with the power to perpetuate a perception that spaces for producing knowledge are or should be limited. Hence, critically intervening must support a way of working with an image-text binary in ways that opens up other ways of thinking the world (with text, image, etc.) that are multiple and dynamic. Thinking differently with text and image creates a network of ambiguities that are, to borrow from Haraway (Citation2015), ‘just big enough to gather up the complexities and keep the edges open and greedy for surprising new and old connections’ (p. 160).

We now turn to the connection between image, text and education. Techniques of teaching and learning have long included experimentation with new technological designs (see for instance Gibbons, Citation2007). Designers and early adopting teachers generally express an intention to innovate inside or outside of the classroom or school, remediating both text and image with the hope that education might somehow benefit. So with the ubiquitous availability of powerful, portable, connectable digital cameras, whose content can be streamed and co-edited and embedded and shared, comes the idea of new ways of weaving together text and image in one's study.

However, Peters and White (this issue) argue that ‘ways of critically examining the image have lagged behind’ ways of examining text and that analysis of the ‘role and importance’ of the image in visual culture is a critical line in the sand as the tidal surge of new visual pedagogies approaches contemporary educational institutions. They go on:

The text is the ruling cultural and academic paradigm. Textual analogues define consciousness, the mind, the unconscious, society, and culture. Science is comprised of discourses and we are presented with text-based understandings of reality that call upon the subject to navigate between text and life. To this day knowledge is predominantly text-based and exchanged, stored and retrieved in texts of this nature. The text dominates our ways of thinking and interpreting the world in philosophical thought. Education is primarily rule by the text – at least in traditional realms of inquiry.

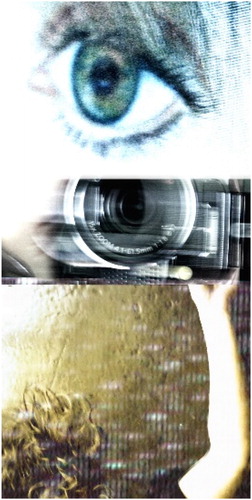

Can we think differently, through a critique of the relationship between text and image, about what it means to have something educational to say/do/think? An example: In Suzie Gorodi's moving images the viewer is pulled along a shabby university corridor by the artist, at the same time observing the space up close. The viewer engages with both a magnification of the institution and a sense of the perpetually observed academic subjectivity, all her movements observed and captured by the devices of the intuition that she is required to pull – our apparent ‘independence and self-reliance’ (Hurrell, Citation2014) is questioned.

With Gorodi's project the main fascination lay in the links between simultaneous images: the information that was presented in parallel where rapidly changing details could be scrutinised and pleasurably pondered over; various angles, profiles and interacting planes accounted for; spatial, speed and movement patterns accentuated. Add to this the subject placing itself under surveillance, not only as a means of image generation (for its own sake) but also exploring muscular self-understanding in terms of gait, posture and body language. (Hurrell, Citation2014)

Image 1. (Jacques Derrida). Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacques_Derrida.

Image 2. (Lonnie Hutchinson, Night: Aroha atu, Aroha mai / I love you, 2016) (two works) from http://ourauckland.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/articles/news/2016/12/regional-public-art/.

Image 3. (Sue Anaru, Untitled, 2016) from Making New exhibition, Innovating Learning Environments Symposium, AUT North Shore campus, 2017).

Image 4. (Michael Parekowhai, Atarangi II, 2005) from http://www.tetuhi.org.nz/whats-on/exhibitiondetails.php?id=8).

Image 5. Victoria O'Sullivan/Janita Craw, Carriers, 2017 (i-phone movie), Making New exhibition, Innovating Learning Environments Symposium, AUT North Shore campus, 2017.

Image 6. (Sue Anaru, Untitled, 2016), Making New exhibition, Innovating Learning Environments Symposium, AUT North Shore campus, 2017.

Image 7. (Eye Photo, Andrew Denton, from Girl with a Movie Camera, Jennifer Nikolai, 2012, reproduced with permission of the artist).

Image 8. (Corridor Series, Suzie Gorodi, 2014) from http://eyecontactsite.com/2014/06/unusual-gorodi-exhibition#ixzz4bQblFxUL, reproduced under Creative Commons.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Agamben, G. (2007). Infancy and history: On the destruction of experience. London: Verso.

- Conor, B. (2004). Hollywood, Wellywood or the Backwoods?’ A political economy of the New Zealand Film Industry (MA), Auckland University of Technology. Retrieved from http://aut.researchgateway.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10292/304/ConorB.pdf;jsessionid=E8B20FAE831A707FA4833102EB651136?sequence=2

- Derrida, J. (2016). Of grammatology. Baltimore, MD: JHU Press.

- Encyclopedia Britannica. (2017). Dropping the Pilot - cartoon by Tenniel. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Dropping-the-Pilot

- Gibbons, A. N. (2007). The matrix ate my baby. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Haraway, D. (2015). Anthropocene, capitalocene, plantationocene, chthulucene: Making kin. Environmental Humanities, 6, 159–165. Retrieved from http://environmentalhumanities.org/arch/vol6/6.7.pdf doi: 10.1215/22011919-3615934

- Hurrell, J. (2014, June 18). Unusual Gorodi exhibition. Eye Contact. Retrieved from http://eyecontactsite.com/2014/06/unusual-gorodi-exhibition#ixzz4bQblFxUL

- New Zealand History. (2017). Flags of New Zealand: Page 6 – The national Māori flag. Retrieved from https://nzhistory.govt.nz/politics/flags-of-new-zealand/maori-flag

- Sabisch, P. (2011). Choreographing relations: Practical philosophy and contemporary choreography in the works of Antonia Baehr, Gilles Deleuze, Juan Dominguez, Félix Guattari, Xavier Le Roy and Eszter Salamon. Munich: Germany: epodium.

- Stiegler, B. (2007). Technics, media, technology. Theory, Culture and Society, 24(7–8), 334–341. doi: 10.1177/0263276407086403

- Stiegler, B. (2013). What makes life worth living: On pharmacology. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- The Guardian. (2017). Steve Bell on the special relationship – cartoon. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/picture/2017/jan/26/steve-bell-uk-us-theresa-may-donald-trump-cartoon

The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled. (Berger, Blomberg, Fox, Dibb, & Hollis, Citation1972)

‘Semiotics is the study of signs and codes, signs that are used in producing, conveying, and interpreting messages and the codes that govern their use’ (Moriarty, Citation2005, p. 227). The general theory of semiotics, developed through works of its main protagonists such as Charles Sanders Peirce, Umberto Eco, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Ferdinand Saussure, and others, has primarily been developed in the context of language. According to Pierce, signifying activity can be described by a simple model consisting of sign (the signifier), object (the signified), and interpretant (mental idea). Moriarty shows that ‘because of Peirce's emphasis on representation as a key element in how a sign “stands for” its object, semiotics has become particularly useful to visual communication scholars who are, by definition, scholars and students of representation’ (ibid: 228). Semiotics is similar, yet quite different, to semiology. According to Arthur Asa Berger, ‘the essential breakthrough of semiology is to take linguistics as a model and apply linguistic concepts to other phenomena – texts – and not just to language itself’ (Berger, Citation2013, p. 134).

What we see becomes what we know through the process of communication. Indeed, semiotics and semiology are primarily focused to sending, conveying and receiving different messages. Speaking of the shift from (static) text to (moving) image, we are interested in two main sub-fields of semiotics: visual semiotics, which focuses to images, and media semiotics, which focuses to mass / digital media. Both semiotics and semiology understand the importance of interpretant's context. However, almost half a century ago, John Berger has gone one step further: he described contextual, cultural, temporary understanding of images, and linked that understanding to technologies of production, sites of production and consummation, and wide social context (capitalism). Alongside communication, therefore, what we see becomes what we know through the process of cultural shaping, mediation, remediation, and interpretation.

This brings about the important problem of the semiotic threshold:

the problem, in semiotic terms, has always been where to place the threshold between the empirical experience of the continuum of authentic reality and the mediated experience of signs composed by an author and interpreted by a reader (inauthentic reality). (O’Neill, Citation2008, p. 145)

Signs can be anything: words, images, music, interactive interfaces, etc. Semiotics operates in ecologies of interconnected signs, or Umwelten, which comprise Lotman’s (Citation1984/Citation2005) concept of semiosphere. Similar to, but nonetheless different from biosphere and noosphere,

the semiotic universe may be regarded as the totality of individual texts and isolated languages as they relate to each other. In this case, all structures will look as if they are constructed out of individual bricks. However, it is more useful to establish a contrasting view: all semiotic space may be regarded as a unified mechanism (if not organism). In this case, primacy does not lie in one or another sign, but in the ‘greater system’, namely the semiosphere. The semiosphere is that same semiotic space, outside of which semiosis itself cannot exist. (Lotman, Citation1984/Citation2005, p. 208).

The contemporary Umwelt simultaneously transforms human environment and calls for redefinition of what it means to be human. In this way, the digital semiosphere is inextricably linked to posthumanism. According to Bayne,

posthumanism is concerned with the questioning of the foundational role of ‘humanity’ as it has been constructed in modernity. Rejecting clear distinctions between ‘nature’ and ‘culture’, it also rejects dualisms and the binaries we have tended to draw on to define what it means to be human in the world: human/machine, human/animal, subject/object, self/other and so on. (Bayne & Jandrić, Citation2017, p. 200)

the focus would be rather on the cultural dynamics that results from the acceleration of processes implicit in the contemporary technosphere, where the ‘content’, cultural products, texts and objects of signification are as crucial, in terms of sustainability, as the cognitive changes and limits of the participating individuals. (Bruni, Citation2015, p. 111)

Created at the peak of the analogue era, John Berger's work has left important traces in various fields from visual studies to feminism. Arguably, the majority of these contributions firmly belong to the past. However, the relationship between what we see and what we know is indeed never settled, and Berger's understanding that visuality can be thought of only in relation to the full semiosphere will continue to live on well into the age of the digital reason.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Bayne, S., & Jandrić, P. (2017). From anthropocentric humanism to critical posthumanism in digital education. Knowledge Cultures, 5(2), 197–216. doi: 10.22381/KC52201712

- Berger, A. A. (2013). Semiological analysis. In O. Boyd-Barrett & P. Braham (Eds.), Media, knowledge and power: A reader (pp. 132–155). New York: Routledge.

- Berger, J., Blomberg, S., Fox, C., Dibb, M., & Hollis, R. (1972). Ways of seeing. London: British Broadcasting Corporation & Penguin.

- Bruni, L. E. (2015). Sustainability, cognitive technologies and the digital semiosphere. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 18(1), 103–117. doi: 10.1177/1367877914528121

- Gunaratman, Y., & Bell, V. (2017, January). How John Berger changed our ways of seeing art: He taught us that photographs always need language, and require a narrative, to make sense. The Independent. Retrieved from http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/features/john-berger-ways-of-seeing-a7518001.html

- Lessig, L. (2001). Code: And other laws of cyberspace. New York: Basic Books.

- Lotman, J. (1984/2005). On the semiosphere. Trans. W. Clark. Sign Systems Studies, 33(1), 205–229.

- Moriarty, S. (2005). Visual semiotics theory. In K. Smith, S. Moriarty, G. Barbatsis, & K. Kenney (Eds.), Handbook of visual communication research: Theory, methods, and media (pp. 227–242). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- O’Neill, S. (2008). Interactive media: The semiotics of embodied interaction. London: Springer Science + Business Media.

- Peters, M. A., & Jandrić, P. (2017). The digital university: A dialogue and manifesto. New York: Peter Lang.

- Saddhu, S. (2012, September 7). Ways of Seeing opened our eyes to visual culture. Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2012/sep/07/ways-seeing-berger-tv-programme-british

Virtual reality environments can be erected artificially into digital constructs, but they can also come into existence by capturing settings from the real world through Immersive Videos (Stuart, Citation2001). This thesis will have a greater focus on the latter. Immersive video recordings enable views in all directions (360 degree recordings), can provide the depth of view (stereoscopic 3D recordings) and enable us to control the environment through manipulation (Trindade et al., Citation2013). These properties specific to the new visual tradition mark the key advantages it holds over traditional video and photographic mediums (Pujol-Tost, Citation2011).

For instance the representation of a bridge going over a river and how this would traditionally be represented in different mediums will be discussed. Written text would portray the setting with words, where different writers would use a range of sentences with a high level of subjectivity in representing the truth. The perception of this reality for a reader would also differ marginally depending on the individual's interpretation of the text. Consequently, if we had several writers describing the setting with several readers interpreting their work we would end up with multiple realities and with at least two levels of subjective truths. This correlates with Husserl’s (Citation1999) idea of reality where he suggests that multiple worlds, offer multiple truths from individual subjective perspectives. Arguably drawings and paintings might diminish some of the subjectivity if the pictorial representations are realistic. Drawings with pencils might leave colour to interpretation. Drawings, paintings, photographs and videos show the observers only the angle the author has chosen hence still concealing a number of truths and imposing further bias. With the video, the viewing angles can change but are still in control of the person recording. Both photo and video add to realism by arguably capturing more realistic illustrations than drawings and painting, where the subjectivity of the author decreases. In these traditions the level of manipulation is very slim. A painting or photograph can be turned around, looked at closer or from afar and a video can be paused, rewound and fast forwarded. Viewing angles and manipulation increase drastically in VR (Dourado & Martin, Citation2013). Not only does it entail a highly accurate representation of the viewed image but the viewer is able to control the view point in every direction and sense the depth of view which lifts the observer into the third dimension, creating a sense of immersion in a vastly more accurate representation of reality. Here the observer would feel as standing in front of the bridge, he could observe the river flowing from underneath it, turn around and look at where the path behind leads to, walk to the bridge, lean down and look at the stones on the gravel road beneath. Nevertheless, immersive videos are not without limitations (Heim, Citation1993; Stuart, Citation2001). Walking distance is confined to the view area of the camera and therefore its placement introduces a level of authors bias. Manipulation within immersive videos is impaired compared to digitally constructed virtual worlds, this impairment is comparable to the difference of the level of manipulation in videos and video games. This means that we could observe the bridge, walk over it but we could not alter it as it was pre-recorded. If it was digitally constructed it could have been a draw bridge we would be able to pull up. This example highlights some of the complexities of different pictorial traditions in relation to truth. VR adds to this complexity particularly as it is designed to simulate or create reality taking the participant on a journey through the cybernetical looking glass into the digital world where according to Heim (Citation1993) the metaphysical laboratory of philosophy resides.

The term ‘Virtual Reality’ is contradictory in, and of, itself as ‘virtual’ means something that is not physically existing or something that is close to the truth but is not the truth itself (Heim, Citation1993). If we are able to see, hear, touch and interact with the virtual world just as well as we can do with the real-life one, how ‘real’ is the virtual world in comparison with the physical world? Are virtual worlds still a mere representations of reality or are they something more? These questions can be addressed very differently depending on which school of realism we pose the question to.

One philosophical theory defines realism depending on the presence of the mind in the world (Convergent realism) (Aronson, Citation1997). It deems a world ‘real’ if we can argue that the world still exists even if the human mind is absent from it. One of the features of virtual worlds is that the user can ‘visit’ them with their mind and leave when desired. The computer simulated world is therefore still in existence, running on the machinery in which it resides but which the mind is not ‘logged into’ at that point in time. Aronson (Citation1997) further argues that it is questionable whether the notion of a mind-independent-world is a necessary feature of realism, for there is a distinction to be made between ‘truth realism’ and ‘object realism’. Therefore from the perspective of object realism the virtual world is ‘real’. This brings us to the notion of truth.

From a philosophical perspective, VR attempts to change the user's perceptions of truth by offering worlds constructed by men, in other words, by giving the designers the role of an omnipotent entity within the designed world. From this perspective, VR worlds can be seen as embodiments of verisimilitude, a falsehood that seems real while having the appearance of a true reality (Renardel de Lavalette & Zwart, Citation2011). This must be seen in the light of the purpose of VR being to mimic reality (Heim, Citation1993; Sharma, Chandra, Venkatraman, Mittal, & Singh, Citation2015).

Current authenticities of verisimilitude are being explored in relation to the question of whether the inquired, complete empirical truth (which in our case is reality itself) is known to the researcher in such a manner as to allow them to be able to descriptively assess how close the false (arbitrary) truth is to the true reality. We can identify The ‘truth’ in VR (which is the real-life world) and the different VR worlds can be investigated, therefore, with the determination of similarities and distinctions (non-referring propositional variables) between the real-life world and certain individual virtual worlds, we can determine the level of verisimilitude. Another way to determine the ‘distance’ between the complete truth and arbitrary truth is to apply a practical test to measure the success of both theories. Based on this thinking truth in VR would be accomplished when it is indistinguishable with the real world. Immersive videos are an exact recording of the reality that is being played back in the virtual world therefore arguably as long as the viewer perceived it true it would also make it true in fact from this viewpoint. The level of current technology is not yet capable to create such an similitude, but it is rapidly closing the gap (Pujol-Tost, Citation2011).

Heim (Citation1993) posed these questions as well. He has noted that people shy away from the ‘R word’ (meaning reality), even though reality was previously the key word of philosophy. When virtuality is talked about in contrast to reality, Heim looks at this from an alternative perspective, naming it ‘artificiality’, in his search for a word which can adequately counterpoint ‘reality’ in the mirror of terminology. He likewise touches on the ideas of a few philosophers, particularly their sense of the real. He mentions Plato's views of ‘ideal forms’ as reality. In this sense, VR could be viewed as real as it tempts viewers with the allure of a perfect world, but to affirm this we would have to assume that forms in reality hold the same value as forms in the digital reality. Similarly, Aristotle's view would also prove relevant as he was talking about substances we can touch (VR technology can make us believe we are touching things with the force-feedback glove). Symbolic significance of ‘real’ in the medieval period is once again comparable with VR reality and passes with ease, as well as in the Renaissance view, as we are able to count and observe objects repeatedly with our senses. In the modern era, ‘reality’ connotes atomic matter that has internal dynamics or energy. This would not apply for virtual worlds, as the objects we are seeing are graphical representations of digital data (unless we ascribe the attribute of ‘real’ substance to data itself in its electro-magnetic existence. Heim (Citation1993) notes the link between cyber space and virtual reality: ‘Cyber space can make breaking through the interface (a human user connects with the system, and the computer becomes interactive) possible and inhabiting an electronic realm where reality and symbolized reality constitute a third entity – Virtual Reality’ (p. 78). Heim even goes so far as to call VR consensual hallucination inasmuch as VR systems use cyberspace to represent physical space.

A year after Heim published ‘Metaphysics of Virtual Reality’ Coyne (Citation1994) responded to his work with a paper speculating on the implications of representations in VR from the perspectives of different theorists and a specific focus on Heidegger's views. Heidegger's concern for the extremes in technology enframing phenomena was great and as VR aims to capture reality itself and there are few extremes that currently measure up to it, it is thought that he would look upon it with criticism (Heidegger, Citation1996). He was also concerned about the authors bias in representations of reality which has already been discussed. Coyne (Citation1994) focused on Heidegger's notion of the tension between correspondence and the social construct that underlaid the workings between truth and reality mirroring the relationship between subjectivity and objectivity, hence his ideas about truthful representations indirectly addresses ‘VR's quest for realism’ (Coyne, Citation1994, p. 69). Following from this, Heidegger's concept of disclosure becomes relevant for VR as he is more concerned about which truths constructs (in our case the virtual world) disclose rather than how close to reality the representation is, hereby the message carried in an immersive video is more important than the sense of reality it provides. Another duality of Heidegger that is relevant for VR is the contrast between earth and the world where the earth is seen as the real-life reality and the world as the constructed virtuality (Coyne, Citation1994). He stresses the notion of difference between these and the clash between constructed order and the realized materiality of the real world. Heidegger suggests that it is this tension that provokes research which is very much apparent for researchers of virtual reality who are perusing to close the space between reality and virtuality while speculating about it as it also measures the distance between truth and verisimilitude, the thickness of the cybernetical looking glass between worlds. Coyne (Citation1994, p. 71) expressed this difference with an example of his own:

The VR experience is not like walking through a building – we can fly through it, pass through walls, and shrink and expand the building around us.

It feels appropriate, though ironic, considering that over two decades have passed since to conclude with Heim’s (Citation1993) proposal:

If for two thousand years, Western culture has puzzled over the meaning of reality, we cannot expect ourselves in two minutes, or even two decades, to arrive at the meaning of virtual reality, (p. 43)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Aronson, J. L. (1997). Truth, verisimilitude, and natural kinds. Philosophical Papers, 26(1), 71–104. doi: 10.1080/05568649709506557

- Coyne, R. (1994). Heidegger and virtual reality: The implications of Heidegger’s thinking for computer representations. Leonardo, 27(1), 65–73. doi: 10.2307/1575952

- Dourado, A. O., & Martin, C. A. (2013). New concept of dynamic flight simulator, Part I. Aerospace Science and Technology, 30(1), 79–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ast.2013.07.005

- Heidegger, M. (1996). The question concerning technology and other essays. (W. Lovitt, Trans.). New York, NY: Harper and Row.

- Heim, M. (1993). The metaphysics of virtual reality. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Husserl, E. (1999). Das allgemeine Ziel der phänomenologischen Philosophie. Husserl Studies, 16(3), 183–254. doi: 10.1023/A:1006307228349

- Pujol-Tost, L. (2011). Realism in virtual reality applications for cultural heritage. International Journal of Virtual Reality, 10(3), 41.

- Renardel de Lavalette, G. R., & Zwart, S. D. (2011). Belief revision and Verisimilitude based on preference and truth orderings. Erkenntnis, 75(2), 237–254. doi: 10.1007/s10670-011-9293-z

- Sharma, G., Chandra, S., Venkatraman, S., Mittal, A., & Singh, V. (2015). Artificial neural network in virtual reality: A survey. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Greeshma_Sharma/publication/297556633_Artificial_Neural_Network_in_Virtual_Reality_A_Survey/links/56dfd64808ae9b93f79aa51a.pdf

- Stuart, R. (2001). The design of virtual environments. Ft. Lee, NJ: Barricade Books.

- Trindade, D., Teixeira, L., Loaiza, M., Carvalho, F., Raposo, A., & Santos, I. (2013). LVRL: Reducing the gap between immersive VR and desktop graphical applications. The International Journal of Virtual Reality, 2(1). Retrieved from http://webserver2.tecgraf.puc-rio.br/~abraposo/pubs/IJVR/LVRL_IJVR2013_Vol01.pdf

A thousand paths are there which have never yet been trodden; a thousand salubrities and hidden islands of life. Unexhausted and undiscovered is still man and man's world.

Awake and hearken, ye lonesome ones! From the future come winds with stealthy pinions, and to fine ears good tidings are proclaimed …

New paths do I tread, a new speech cometh unto me; tired have I become— like all creators—of the old tongues. No longer will my spirit walk on worn-out soles.

Too slowly runneth all speaking for me:—into thy chariot, O storm, do I leap! And even thee will I whip with my spite!

Like a cry and an huzza will I traverse wide seas, till I find the Happy Isles where my friends sojourn;— (Nietzche, First Part. Zarathustra's prologue. p. 88)

Like Nietzche's superman, the moving image acts as a bridge between human and ‘other’, walking a tightrope that connects, and perhaps at last begins to reconcile, (wo)man and machine. The moving image does not merely lie in the static parchment of text; nor does it draw its source from the sign as a mere communicative exchange from self to ‘other’, as traditional semiotics would suggest. It is a technical, psychological and sensory artistry. While the poststructuralist turn provided an important means of establishing a much more complex relationship between the image and the subject, the image itself remains static within this philosophical realm – until given a breath of life through movement (active engagement) of and with the subject. Even if it had the means to ‘speak’ from a posthumanist stance, the image, in the absence of this inflation, could not physically move (beyond a psychological ‘movement’ through aesthetic engagement) and therefore act beyond its internal affect on the discerning subject. In contrast, the moving image – once unleashed via its fast-changing technologies and social platforms – is active and has a literal voice that is expressed through intervisual movement. The latter manifest through the addition of sound which brings simulacra to its knees in a myriad of ways.

At its most primitive the moving image can be viewed a mode of production comprised of a series of connected still frames and sounds presented to the viewer at a fast pace, dominant in popular culture today; while at its limits the moving image offers a means of inviting the self into its sphere as a co-creator and multiple personhood – both networked author and consumer. These limits are merely temporal since the technologies of the moving image are moving well in advance of the knowledge base (and an associated means of understanding its semiotic location) that struggles to keep up with this (e)motion.

Movement is central to human experience and a central source of becoming. It is embodied in live events, as actions that take place in the flux of time and space. As Zinchenko outlines, action is both ‘heterogenous and heterostructural – represented in it are the main attributes of the soul – cognition, feeling and will’ (p. 191). As such, those who are open to the possibilities that unfold are brought into a new consciousness through such means. In an associated manner the moving image acts upon, through and with humans both in the world, with the world, and on the world through its capacity to mobilize, connect and create in hitherto unimaginable ways. Through such movement image(s) summon new forms of engagement through existential, virtual, metaphoric, satiric and representational means (to name but a few – each of which has yet to be explored in education) via evolving technologies. Summoning its fullest potential, the moving image therefore has the means to penetrate conventional philosophy as a kind of trans-genre proto-type which diminishes the tyranny of the receiving (or appreciative) human subject by rupturing the self-other (or author-audience) divide that has, until recently, dominated philosophies of the image (and, indeed, education) in one way or another. It re-actualises Malevich’s (Citation2014) entreaty for the non-objectification of art, and collapses the tyranny of both selfhood and hierarchies concerning the image as a static aesthetic expression by the artist alone.

Through access to alternate combinations and complexities of visual worlds in motion the non-coinciding nature of otherness and the non-objectivity of art is at last heralded – creating opportunities for critical inquiry, self-awareness, de-construction and even deception or destruction. The latter made possible because the moving image in the hands of – like Zarasthustra's ‘child in the mirror’ – is highly capable of manipulating ‘reality’ and has the capacity to actively conflate fiction with non-fiction thus generating multiple selves; granting access to alternate existences, collapsing traditional notions of time and space, and providing both access to and beyond the body (eventually, perhaps, abandoning the body altogether as a proto-encounter that takes place beyond the limits of a physical self as in VR and AR). This is a creative moment that takes account of our philosophical heritage yet moves to contemplate unknown futures that have the potential to reconstitute existing dichotomies of virtual vs real; ‘I’ vs ‘us’; technology vs experience, and so on.

Adopting this ‘proto’ stance, Epstein (Citation2012) calls for a new logic to explain the ‘self’, seeking a new materiality of images that grants them agentic presence in the ‘social’ alongside both artist and admirer. Video now commonly summoned to facebook, as a classic example, takes us well beyond traditional linguistic, geographical, political and even intellectual barriers – granting access, creative formation and inviting response to all. Its presence is felt everywhere – on cell phones and shopping malls alike – generating new forms of engagement for the masses. The moving image galvanizes the collective intellect on a technical level that acts as a multi-sensorial host and provides a portal into previously unimagined forms of intelligentsia – far beyond the academy where traditional borders might now be penetrated through the means now at their disposal. The moving image grants wo(man) freedom to duplicate, create, distort, alternate and eliminate as all-seeing shape-shifters within the networked society that is becoming central to civilization today. With this freedom, the moving image has the potential to take philosophy of education beyond moral concerns with ‘post-truth’ to a transhuman interplay with the multi-senses – an active creative engagement that is accessible to all who can ‘see’; and not the chosen few who have the good fortune to know how to ‘read’ the static sign – here a cautionary note is applied to the uncritical treatment of what is seen and the challenges this poses for education.

A non-coinciding proto-type viz-a-viz the unbridled potential of the moving image is especially relevant for philosophy of education in consideration of the contemporary endurance of dominant ‘posts’ which, while helpful in moving beyond the taken-for-granted constructs of their predecessors over the past century, no longer serve educational futures adequately in the era of the moving image. ‘Post’ anything is always, by its very nature, a reaction against or in opposition to its predecessor. As a consequence, ‘post’ philosophies only flourish when they can distinguish categorically between existing ways of thinking as a kind of ‘break’. The moving image does not seek so much a harsh break but rather provides fresh opportunities to go beyond existing philosophical strongholds of ‘the subject’ and ‘the image’ in anticipation of connected dialogic futures that lie in its wake. Hence, rather than yet another ‘post’, the moving image starts to map out a ‘proto’ pathway for future educational thought which stakes its contemporary claims on an anticipated future in consideration of a non-coinciding (human) self who is the moving image as much as the moving image is him. Is this Nietzche's superman in (virtual, temporal and ideological) carnation? Only time will tell but, if we are wise to the proto potentialities advanced through the moving image, there is every possibility that we can and will exceed our own bounds through such active means. I, for one, look forward to the future in this regard.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Epstein, M. (2012). The transformative humanities: A manifesto. Chicago: Bloomsbury academic.

- Higgins, K. (2010). Nietzche’s Zarasthustra (Revised ed.). Plymouth: Lexington Books.

- Malevich, K. (2014). The world as objectlessness. Trans. Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern, Kuntsmuseum Basel, Germany, Ganske Publishing Company.

Suppose that the teacher's role in the not too distant future is assumed by a robot-teacher and furthermore that this turn of events is accompanied by a political initiative that obligates students to form themselves as entrepreneurs, which is understood here as a kind of antithetical development. I have coupled together these two ideas to highlight how the student's capacity to change meaning and practice might function as a counter the robot-teacher's summary use of our collective history of thought. In other words, I am writing with a view to describing how the contemporary student might avoid becoming manipulated by the robot-teacher's more effective use of human knowledge or what might be called their deep intelligence (Musk, Citation2017).Footnote1 The paradox here and the challenge to the student's capacity to be philosophical in thinking this paradox has to do with the fact that artificial intelligence (AI) has become both the fundamental operant in the student's process of learning and the inhibiter to postdigital thought; that which will enable the student to be capable of changing the meaning and practice in the context of being taught by a robot-teacher. In response to the invitation to contribute to this collective article, it will be argued that it is through new forms of writing that new relations with the image and the moving image will be formed, and that it is through these new forms of writing that the nature of the above described paradox will be grappled with.Footnote2

Before discussing the relation of text to image and that of the text to moving image, I will attempt to ground my original proposal in contemporary experience. Firstly there is the question of whether robot-teachers will in fact be dispatched to fill the role of teachers.Footnote3 Why is this development inevitable? Economics – the defining factor in the governance of education – tells us that the relationship between ‘ends and scarce means’ has been exhausted such that teachers can no longer provide the means to produce the ends that economics and technological development in a global world now require of them. For this reason we have seen the introduction of innovative learning environments as a policy development – a development that is not uniquely policy driven in that student use of AI presupposes both an opening up of the learning space in the interests of student learning and a deterritorialization of the same learning space. This development is not the consequence of teachers not wanting to teach, nor is it a consequence of teachers not being good at the task of implementing education policy. Neither ‘passion’ nor ‘conviction’ will serve to change this situation or the narrative that education now finds itself engaging.Footnote4