ABSTRACT

The digital age has amplified exposure to pornography, particularly among gay and bisexual men, intensifying the ongoing research debate surrounding its impact on well-being. We recruited 632 Australian gay and bisexual men to participate in an online survey to examine the relationship between porn use and their psychosocial/psychosexual well-being. Data on demographics, psychosocial well-being, understandings of sexuality, sexual self-esteem, connectedness to the LGBT community, and porn use, including porn use statements developed for this study, were collected. Most participants reported viewing porn a few times per week or once a day. Associations were identified between frequency, length of porn use, and other concepts. Older participants used porn less frequently, while those with higher psychological distress tended to be at opposite ends/poles of porn use frequency. Higher connectedness to the LGBT community was associated with less frequent porn use. Certain beliefs about porn were correlated with the frequency and length of porn use; for example, participants engaging with ‘kinkier’ porn and considering themselves ‘kinkier’ had longer viewing sessions. The findings offer insights into the interplay between individual characteristics, well-being, and patterns of porn usage in this population, contributing to a deeper understanding of the relationships between these concepts.

Introduction

The widespread availability and accessibility of pornography (‘porn’) through the internet has significantly changed when and how porn is consumed compared to previous forms of erotic media as well as impacted on the motivations for consuming porn (Grubbs et al. Citation2019). As porn consumption/use becomes more prevalent (Regnerus, Gordon, and Price Citation2016; Ballester-Arnal et al. Citation2023), it becomes increasingly important to understand its impact – both positive and negative – on the psychosocial and psychosexual well-being of individuals and populations. This understanding is important for communities whose members may experience marginalization due to their sexuality or sexual orientation. Sexual minority men – that is, gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men – have been an important focus of research on porn use due to their unique experiences and challenges. Studies have overall shown that sexual minority men have higher rates of porn use than heterosexual men (Stein et al. Citation2012; Rosser et al. Citation2013; Hald and Štulhofer Citation2016; Downing et al. Citation2017). This increased engagement in porn can be attributed to a multitude of factors, including the availability of specific gay pornography and its role in facilitating sexual exploration, sex education, identity formation, and community-building (Kubicek et al. Citation2010; Hald, Smolenski, and Rosser Citation2013; Goh Citation2017; Nelson, Pantalone, and Carey Citation2019).

The portrayal of same-sex male sexual encounters in mainstream media and porn has historically been constrained and continues to be limited within mainstream media (Seif Citation2017). However, the internet and social media have facilitated the creation and dissemination of gay porn over the past three decades, catering specifically to the sexual interests and desires of sexual minority men and increasingly also catering to the diverse sexual interests and fetishes present within these communities (Grov et al. Citation2014; Klaassen and Peter Citation2015). This increased availability of gay porn has provided sexual minority men with a readily available platform to explore their sexual identities, desires, and preferences in an easily accessible and largely anonymous environment (Grov et al. Citation2014; Binnie and Reavey Citation2020).

Current understandings and assumptions about porn – including its definition and how its use can be quantified and analyzed – are being re-evaluated in light of recent interdisciplinary research. Some scholars, such as McKee et al. (Citation2020), have highlighted the complexities and nuances in defining and – subsequently – measuring porn use, particularly in ‘the digital age’ (Ashton, McDonald, and Kirkman Citation2019). Given the ‘participatory culture’ of digital and social media (Jenkins, Ito, and boyd Citation2015), traditional notions of media consumption, including ingrained research questions borrowed from a pre-digital media era, have been disrupted. The production and distribution of media among personal and sometimes private networks has changed porn content and use, necessitating new inquiries into porn use (Paasonen Citation2011; Mercer Citation2017). This includes new questions about the intersections of well-being, community-building, social networks, and sexual subjectivities in a digital age.

However, it should be acknowledged that not all scholars agree on the difficulty of defining pornography. Kohut et al. (Citation2020), for example, argue that more concrete conceptual and operational definitions of pornography use are possible, which challenges the prevailing uncertainty in the academic discourse. Their critique emphasizes the need for a more rigorous approach to defining and studying porn use.

In light of these ongoing debates, we propose the following working definition:

For the purpose of this study, porn is defined as any material aimed at creating or enhancing sexual feelings in the person using it by showing genitals and sexual acts, such as oral or anal sex, masturbation, fetish play, and so on.

Use of porn may also be understood from a community perspective rather than porn’s impact on an individual level. Here, porn may be conceptualized as a community-building tool by adding to shared community language and providing cultural references within queer communities (Mowlabocus Citation2016). Studies have shown that porn can facilitate the formation of both online and offline communities, providing a space in which sexual minority men can engage in a discourse about sexuality, exchange recommendations, and seek support or advice (Vörös Citation2014; Cassidy Citation2018; Robards Citation2018; Tiidenberg Citation2019; Wang Citation2021; Ding and Song Citation2023; Sundén Citation2023). Digital media scholars have further highlighted the increased, although somewhat precarious, use of social media for building and connecting to sexual communities (Tiidenberg and van der Nagel Citation2020), and in many cases this involves the production and/or circulation of pornographic content within an erotic community (Robards Citation2018; Tiidenberg Citation2019; Ding and Song Citation2023). This work troubles simple understandings of porn use as an individualized and private act, highlighting how for many, particularly gay men as well as queer kink communities (Sundén Citation2023), sharing pornographic content can be experienced as a connection to and participation within a community.

The previously described theoretical benefits from porn use in terms of identity formation and community-building have been underappreciated, and most of the research focuses on potential negative impacts of porn consumption. This body of research primarily examines porn’s effects on condom use, safer sex practices, body image disorders, and mental health. It is worth noting that labelling porn as an ‘addiction’ is often ‘inaccurate, misleading, and likely harmful’ (Prause and Williams Citation2020). While it is indeed important to understand the potential negative impacts, this deficit-based approach has resulted in uncertainty about any potential benefits of porn and its use. A major point of interest, particularly with regard to sexual minority men, is the relationship between porn use and different aspects of psychosocial and psychosexual well-being from a strength-based perspective. This includes psychological distress, understandings of sexuality, and sexual self-esteem.

The current body of health literature suggests that psychological distress may be related to pornography use. Studies have found that higher levels of psychological distress are associated with increased porn use, which is sometimes described as addiction or compulsive behaviour (Grubbs et al. Citation2015a; Whitfield et al. Citation2018). However, the direction of these relationships remains unclear, as porn may serve as a coping mechanism rather than the cause of psychological distress (Williams Citation2017). Some studies have taken an alternative perspective by examining different typologies of porn use, whilst still adopting a generally deficit-based approach (Gola, Lewczuk, and Skorko Citation2016).

Research on sexual health and the use of porn in sexual minority men is relatively robust, but primarily focuses on how porn influences safer sex behaviours and body image disorders, yielding mixed results in terms of their overall conclusions. For instance, some studies suggest that consuming bareback pornFootnote1 can impact men’s inclination to engage in sexual risk behaviours (Jonas et al. Citation2014), while other research has shown that porn consumption may have negative impacts on body images in sexual minority men (Tylka Citation2015; Whitfield et al. Citation2018). However, few public health studies have reviewed how porn use is associated with other domains of psychosexual well-being, including understandings of sexuality (sex positivity and sex negativity) and sexual self-esteem (Kvalem, Træen, and Iantaffi Citation2016). Indeed, recently there has been some recognition of positive intimacy models that some pornographic videos can offer (Newton, Halford, and Barlow Citation2021; Newton et al. Citation2022).

To our knowledge, there are currently no primary studies specifically focusing on the relationship between the concept of LGBTQ+ community connectedness and porn use. Given the potentially beneficial impacts of porn use described earlier, this area remains under-researched, despite the strong correlation between connectedness to the LGBTQ+ community and sexual minority individuals’ well-being and identity development (Frost and Meyer Citation2012). Previous research has demonstrated that higher levels of community connectedness are associated with positive psychological outcomes, including increased self-esteem and reduced psychological distress (Roberts and Christens Citation2021). Therefore, the primary aims of this study are to:

explore relationships between porn and psychosocial distress in sexual minority men;

explore relationships between porn use and psychosexual well-being (understandings of sexuality, sexual self-esteem) in sexual minority men; and

explore the relationship between porn use and connectedness to the LGBTQ+ community in sexual minority men

Methodology

Participants and recruitment

Men who self-identified as gay, bisexual, or another non-heterosexual sexual orientation participated in an anonymous cross-sectional online survey in January and February 2023. All adult men (18 years or older) living in Australia were eligible to participate in the survey regardless of their sex recorded at birth if they used pornography within the past 12 months before commencing the survey.

Recruitment exclusively took place online, utilizing groups on social media platforms that are highly frequented by sexual minority men as well as through paid advertisements on geosocial networking mobile applications geared towards sexual minority men. As an incentive, participants were offered to enter a prize draw of 20 retail vouchers valued at AU$25 each. Ethical approval was granted through the University of Technology Sydney’s Medical Research Ethics Committee (Approval Number: ETH22-7691). Informed consent was sought from each participant before commencing the survey.

Variables and concepts

Demographics

Participants were asked about their age in years, sexual orientation, sex recorded at birth, ethnicity, first language, and state/territory of residence.

Psychosocial and psychosexual well-being

Psychological distress was measured using the Kessler-10 (K10) Psychological Distress Scale (Kessler and Mroczek Citation1994). The K10 consists of 10 items asking about different aspects of psychological distress (e.g. ‘During the last 30 days, about how often did you feel tired out for no good reason?’) on a Likert scale from 1 (None of the time) to 5 (All of the time), resulting in a final score between 10 and 50 with higher scores suggesting higher levels of psychological distress, with values over 15 being interpreted as psychological distress being above low (Andrews and Slade Citation2001).

Understandings of and attitudes to sexuality (‘erotophobia and erotophilia’) were measured using the Sex Positivity–Negativity Scale as developed and validated by Hangen and Rogge (Citation2022). The instrument uses 16 items related to respondents’ feelings towards sex and sexuality using keywords (e.g. ‘Fun’, ‘Enriching’, ‘Annoying’) on a six-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all, 2 = A little, 3 = Somewhat, 4 = Quite a bit, 5 = Very much, 6 = Extremely), resulting in two scales measuring sex positivity and sex negativity with a score from 1 to 6, with higher scores indicating higher levels of sex positivity and negativity, respectively.

Sexual self-esteem was measured using the sexual self-esteem scale developed by Snell, Fisher, and Schuh (Citation1992) as adapted by Lammers and Stoker (Citation2019). This scale consists of five statements (e.g. ‘I am better at sex than most people’) with a five-point Likert scale (Agree/Slightly Agree/Neither Agree nor Disagree/Slightly Disagree/Disagree) which are transformed to a scale from −2 (Disagree) to 2 (Agree) and summed up to a value between −10 and +10, with higher levels showing higher sexual self-esteem.

Connectedness to the LGBTQ+ community was measured using the adapted version by Demant et al. (Citation2018) which is based on the original scale developed by Frost and Meyer (Citation2012). The scale consists of eight statements on respondents’ connections to the LGBTQ+ community (e.g. ‘You feel you’re a part of the LGBT community’) with an end-point defined Likert scale from 1 (Agree strongly) to 4 (Disagree strongly) leading to a score from 8 to 32, with higher scores showing higher levels of connectedness.

Use of porn

Prior to the first items concerning porn, participants were provided with the working definition used by the team to ensure consistency (see Introduction).

The frequency of porn use was measured ordinally (less than a few times a month, a few times per month, a few times per week, about once a day, more than once a day); similarly, the length of porn use in an average single session was measured ordinally (less than 15 minutes, 15 minutes to less than 30 minutes, 30 minutes to less than an hour, one hour to less than two hours, more than two hours).

The authors developed seven statements loosely based on a range of existing literature including the work by Kalichman and Rompa (Citation1995) on the sexual sensation-seeking scale focusing on different aspects of the relationship between porn and other aspects of sexuality and the developing nature of porn use:

Statement 1: ‘I like types of sexual activities in porn that I wouldn’t try myself with another person.’

Statement 2: ‘Some of the things I like to do with others do not interest me when watching porn.’

Statement 3: ‘What I do with others is kinkier than the porn I watch.’

Statement 4: ‘The types of porn I watch have changed over the past couple of years.’

Statement 5: ‘I have seen things in porn that I wanted to try with another person.’

Statement 6: ‘I have seen things in porn that I have tried with another person.’

Statement 7: ‘The more porn I watch, the kinkier the porn gets.’

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics v28. Descriptive statistics are reported as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and as mean with standard deviation (SD) or as median with interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables.

The primary outcome variables for this research were frequency and length of porn use. Associations with psychosocial and psychosexual well-being, other porn use variables, as well as age and sexual orientation were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test, the Fisher–Freeman–Halton exact test, and the Jonckheere–Terpstra test. All test assumptions were met. Statistical significance was interpreted using α = 0.025 based on the traditional cut-off of α = 0.05 which was adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction method.

The internal reliability of scales was interpreted using Cronbach’s α. All scales have demonstrated good to excellent internal consistency with Cronbach α values between 0.883 and 0.941. The unidimensionality of scales was confirmed through exploratory factor analyses, with the first factor in all cases exceeding the commonly applied threshold of 1.

It was assumed that the seven developed statements might form a reliable scale measurement. However, analyses have shown that the hypothesized scale falls just short of an acceptable level of reliability with Cronbach’s α = 0.591. As a result, items are included as individual variables rather than as a scale measurement.

Results

Final sample size

A total of 747 participants consented to the survey and started the questionnaire; 54 of these were removed as they did not fulfil at least one of the eligibility criteria (26 did not identify with a sexual minority, 16 lived outside Australia, 11 did not identify as a man, seven did not use any porn in the past 12 months, and five were under the age of 18 years).Footnote2 Of the remaining 693 participants, 35 were removed as they did not respond to basic demographic questions (age, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, living area). Finally, 26 were removed as these participants did not reply to any question related to the use of porn, leading to a final sample size of 632 participants.

Demographics

Demographic details are presented in . The median age of respondents was 34 years (IQR = 28–42), ranging from 18 to 81 years of age. The majority of participants identified as gay (n = 448, 70.9%) and were recorded as male at birth (n = 613, 97.0%). The place of residence for most participants (n = 506, 80%) was in one of the three states with the largest population in Australia (New South Wales, Victoria, and Queensland). Participants were largely of European or Anglo-Saxon background (n = 430, 68.0%), followed by East and Southeast Asian (n = 86, 13.6%) and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (n = 53, 8.4%). English was the first language of 526 (83.2%) participants.

Table 1. Demographics (N = 632).

Psychosocial and psychosexual well-being

The median K10 psychological distress scale was 20 (IQR = 14–28) with 69.2% (n = 384) of participants experiencing distress higher than low. Connectedness to the LGBT community was overall low to moderate in the sample with a mean score of 18.2 (SD = 5.7) on a scale from 8 to 32 (see ). Sex positivity was stronger in the sample than sex negativity with a median sex positivity scale score in the sample of 5.1 (IQR = 4.5–5.5), while the sex negativity score was lower with a median of 2.3 (IQR = 1.5–3.1). The median sexual self-esteem in the sample was 5 (IQR = 1–8).

Table 2. Psychosocial and porn-use measurements.

Porn use and associations

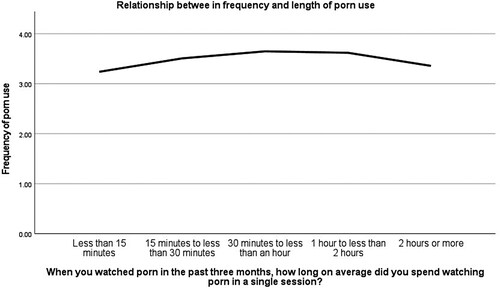

Most people used porn a few times a week (n = 243, 38.4%) or about once a day (n = 162, 26.8%), with fewer people watching it more than once a day or a few times per month or less (see ). Two-thirds of participants watched between 15 minutes and one hour within a single session (n = 411, 66.8%), followed by those watching less than 15 minutes (n = 112, 18.2%) and those who watched porn for one hour or more (n = 92, 15%). A significant relationship was found between incidence and length of porn use (X2(16, 589) = 55.031, p < 0.001); however, the relationship between the two variables is non-monotonic (see ) and shows that those who watch more than once a day and those who watch less than a few times per months tend to watch for longer than those between these points.

Figure 1. Relationship between frequency of porn use and length of porn use. Note: Frequency of porn use: 1 = more than once a day; 2 = about once a day; 3 = a few times per week; 4 = a few times per month; 5 = less than a few times per month.

Porn use statements were measured on a scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree) and were not normally distributed. The lowest agreement was found for the statement ‘What I do with others is kinkier than the porn I watch’ with a median of 2 (IQR = 1–4), while a very strong agreement was found for the statements ‘I have seen things in porn that I wanted to try with another person’ (median = 6; IQR = 5–7) and ‘I have seen things in porn that I have tried with another person’ (median = 6; IQR = 4–7), while all other statements ranged between these values.

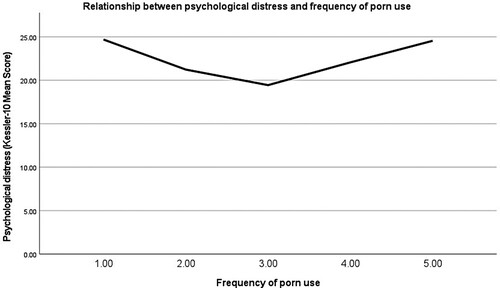

Several relationships between the frequency of porn use and other variables were identified (see ). Age was significantly associated with the frequency of porn use with older participants using porn less frequently than their younger counterparts (X2(4, 604) = 11.703, p = 0.020). The relationship between psychological distress (K10) and frequency of use (TJT = 56462.50, z = 2.700, p = 0.007) was non-monotonic (see ), with participants with higher scores overall being located at the ends of the frequency of use while those with lower scores were in the centre of the distribution. However, the relationship between LGBTQ+ community connectedness was monotonic, with an increase in connectedness score being associated with a decrease in the frequency of porn use (TJT = 55602.50, z = 2.244, p = 0.025). However, it should be noted that a relationship between age and community connectedness was identified with older participants also tending to be more connected to the LGBTQ+ community (r = 0.150, n = 554, p < 0.001). Concerning porn statements, statements 2 (‘The more porn, the kinkier’), 5 (‘Porn has changed over time’), 6 (‘Seen things that want to try’), and 7 (‘Seen things, did try with others’) were correlated with the frequency of porn use, with a general trend that higher agreement to these statements reflects a higher frequency of porn use (see ).

Figure 2. Relationship between psychological distress and frequency of porn use. Note: Frequency of porn use: 1 = more than once a day; 2 = about once a day; 3 = a few times per week; 4 = a few times per month; 5 = less than a few times per month.

Table 3. Association between incidence and length of porn use with psychosocial scale measurements, porn-perception items, and selected demographics.

While many correlations were found between frequency of porn use and other variables, this was not the case for length of porn use, which is only correlated to two of the porn statements showing that those who engage in ‘kinkier’ porn over time (Statement 2; TJT = 67454.00, z = 3.143, p = 0.002) and those who stated to be ‘kinkier’ in-person than the porn they are watching (Statement 4; TJT = 71705.00, z = 4.995, p < 0.001) are more likely to watch porn for longer as well.

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the relationship between porn use and aspects of psychosocial and psychosexual well-being in a diverse sample of 632 Australian sexual minority men. The overall objective was to explore the relationships between porn use and psychosocial and psychosexual well-being concepts.

A significant and meaningful relationship between the frequency of porn use and the length of porn use among participants was identified. Analyses showed that participants with either a low frequency or a high frequency of porn use tend to watch porn for longer durations compared to those in between these extremes. While previous studies have examined these variables separately (Eaton et al. Citation2011; Kvalem, Træen, and Iantaffi Citation2016), to the best of our knowledge no study has explored the relationship between these variables specifically in sexual minority men, although some qualitative studies appear to touch on this relationship (Hanseder and Dantas Citation2023). This non-monotonic relationship may be explained through intensity of engagement or the intensity of desire. For example, men with a low frequency of porn use may approach it as a relatively infrequent activity to which they dedicate more time to individual sessions. Conversely, men with a high frequency of porn use may have a stronger desire for sexual stimulation, leading to longer sessions to achieve the desired level of satisfaction or arousal.

Demographic factors played no role in the length of porn use, and only age (but not sexual orientation) was associated with the frequency of porn use. Younger men reported more frequent use of porn than their older counterparts. This finding is consistent with existing literature showing a pattern of more frequent porn consumption among young men (Levin, Lillis, and Hayes Citation2012; Sun et al. Citation2016). Studies exploring the motivations for porn use have introduced various constructs that underpin the motivational basis for individual motivations to engage with porn (Bőthe et al. Citation2021). Changes in these motivational factors throughout age, such as changes in sexual curiosity, self-exploration, or boredom avoidance, may explain the higher frequency in porn consumption among young men (Ainsworth and Baumeister Citation2012; Mercer et al. Citation2013; Kar, Choudhury, and Singh Citation2015).

One of the potential benefits of porn use we highlighted in the Introduction is its potential role in sexual exploration and identity formation among sexual minority men. The study findings support this notion, as higher levels of agreement with our developed porn use statements related to ‘trying things seen in porn with another person’ were associated with a higher frequency of porn use. This finding suggests that sexual minority men may draw inspiration from porn to explore their own desires and possibilities for sexual expression. Previous studies have also supported this interpretation by demonstrating similar mechanisms (Poole and Milligan Citation2018; Crath, Rangel, and Gaubinger Citation2021). It is noteworthy to highlight that men who have sex with men have had markedly less opportunity to receive sexual education though traditional channels compared to straight men. Arguably, the limited access to education might have resulted in pornography taking a more predominant role in the community. Several other statements were found to be associated with porn use, primarily with the frequency of use rather than length of use. Overall, participants reported that the porn they watch becomes kinkier over time, and these changes were associated with the frequency of porn use.

Regarding other measurements of psychosexual well-being, we did not find any association between porn use and sexual self-esteem, sex positivity or sex-negativity. The current body of evidence is not clear on the relationship between sexual self-esteem and porn use, as it appears to be influenced by individuals’ positive or negative perceptions of porn (Štulhofer, Buško, and Landripet Citation2010; Kvalem, Træen, and Iantaffi Citation2016). A small association was observed between the frequency of porn use and sex negativity, with participants on opposite ends of the frequency scale demonstrating slightly higher levels of negative sex attitudes compared to those in between; however, this association should not be interpreted as significant to avoid a type I error.

A key finding is that psychological distress displayed a non-monotonic association with the frequency of porn use, similar to the other measurements of psychological and psychosocial well-being. Participants at opposite ends of the frequency scale exhibited higher levels of psychological distress than those between these poles. Previous research has identified associations between psychological distress and porn use in general, but often without distinguishing between different typologies of use (Grubbs et al. Citation2015b), or has focused on ‘problematic’ porn use (Mennig, Tennie, and Barke Citation2022; Rodda and Luoto Citation2023). A hypothesis that can be drawn from this finding is that the average use of pornography has little interference with mental well-being but, rather, manifests more as an expression of overall well-being itself. This is consistent with the fact that a balanced sexuality is a fundamental aspect of well-being for all individuals (Ford et al. Citation2021; Mitchell et al. Citation2021).

The results also indicated that higher levels of LGBTQ+ community connectedness were associated with less frequent porn use. This suggests that porn consumption may not form a shared experience within sexual minority men communities in a way that increases community connectedness. Findings from other, more general studies, suggested that porn can function as a community-building tool, contributing to the formation of social networks and the development of a shared cultural language within sexual minority communities (Mowlabocus Citation2016; Mercer Citation2017; Wang Citation2021). However, it is important to note that the relationship between porn use and community connectedness is multifaceted and that this relationship may be affected by age, as age is both related to community connectedness and porn use. Therefore, age may mask the true relationship between these two concepts. It should also be noted that a specific, socio-political, form of LGBTQ+ community connectedness was tested within this study (Frost and Meyer Citation2012) and that results may be impacted by the sample or recruitment method and are not necessarily representative of the wider community of sexual minority men.

This study examined the association between porn use and various aspects of psychosocial and psychosexual well-being in a diverse sample of Australian sexual minority men. The findings provide insights into the relationships between the consumption and use of porn, and key psychosocial and psychosexual concepts, shedding light on the potential impact of pornography on the well-being of sexual minority men. Concerning the predominance of literature focusing on the adverse effects of porn consumption, this finding demonstrates that, at least in our study cohort, the relationship between well-being and psychological constructs is not straight-forward and needs to be contextualized with the broader findings such as those described earlier that suggest that porn may help facilitate a sense of belonging. Overall, the result of this study should be seen as a contribution to a more nuanced understanding of sexual well-being. This perspective is particularly relevant for minority groups who are often overlooked by mainstream sexual health narratives.

Strengths and limitations

The present study represents the first comprehensive research examining the associations between psychosocial and psychosexual well-being with porn use in a sample of Australian sexual minority men. The study included a variety of valid and reliable measurements to capture different aspects of these relationships. However, it is important to note that due to the cross-sectional nature of the data, we are unable to establish cause–effect relationships between porn use and other measured variables. Additionally, it is possible that participants may have overestimate or underestimate their porn use, introducing some degree of measurement error.

In an effort to gain a comprehensive understanding of porn use among Australian sexual minority men, we developed a set of porn use statements specifically tailored for this study. The aim was to create a reliable measurement that captures a holistic view of pornography use among sexual minority men. However, upon analysis, the proposed scale fell short of an acceptable level of reliability. This suggests that further refinement of the measurement tool is needed to ensure its accuracy and consistency in assessing pornography use among sexual minority men. It should be noted that the Sex Positivity–Negativity Scale by Hangen and Rogge (Citation2022) that has been used may be perceived by some scholars to conflate the concept of sex positivity, an attitude, with the concept erotophilia, a psychological construct. These two concepts are generally perceived to be distinct in both scope and application.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

1 Commonly defined as gay pornography that features penetrative sex without the use of a condom (Morris and Paasonen Citation2014). However, this phenomenon may no longer be as relevant with changes to safer sex norms within gay communities since the availability of pre-exposure prophylaxis (da Silva-Brandao and Ianni Citation2020).

2 Data do not add up to 54 as some did not fulfil more than one eligibility criteria.

References

- Ainsworth, Sarah E and Roy F Baumeister. 2012. ‘Changes in Sexuality: How Sexuality Changes Across Time, Across Relationships, and Across Sociocultural Contexts.’ Clinical Neuropsychiatry 9 (1): 32–38.

- Andrews, Gavin and Tim Slade. 2001. ‘Interpreting Scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10).’ Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 25 (6): 494–497.

- Ashton, Sarah, Karalyn McDonald and Maggie Kirkman. 2019. ‘What Does ‘Pornography’ Mean in the Digital age? Revisiting a Definition for Social Science Researchers.’ Porn Studies 6 (2): 144–168.

- Ballester-Arnal, Rafael, Marta Garcia-Barba, Jesus Castro-Calvo, Cristina Gimenez-Garcia and Maria Dolores Gil-Llario. 2023. ‘Pornography Consumption in People of Different age Groups: An Analysis Based on Gender, Contents, and Consequences.’ Sexuality Research and Social Policy 20 (2): 766–779.

- Binnie, James and Paula Reavey. 2020. ‘Development and Implications of Pornography Use: A Narrative Review.’ Sexual and Relationship Therapy 35 (2): 178–194.

- Bőthe, Beáta, István Tóth-Király, Nóra Bella, Marc N Potenza, Zsolt Demetrovics and Gábor Orosz. 2021. ‘Why do People Watch Pornography? The Motivational Basis of Pornography Use.’ Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 35 (2): 172–186.

- Cassidy, Elija. 2018. Gay Men, Identity and Social Media: A Culture of Participatory Reluctance. New York: Routledge.

- Cover, Rob. 2018. ‘The Proliferation of Gender and Sexual Identities, Categories and Labels among Young People: Emergent Taxonomies.’ In Youth, Sexuality and Sexual Citizenship, edited by Peter Aggleton, Rob Cover, Deana Leahy, Daniel Marshall and Mary Lou Rasmussen, 278–290. London: Routledge.

- Crath, Rory David, J Cristian Rangel and Adam Gaubinger. 2021. ‘Biopolitics’ New Iteration: Gay Men, Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis and the Pharmaco-Pornographic Imagination.’ Sexualities 26 (7): 13634607211056882.

- da Silva-Brandao, Roberto Rubem and Aurea Maria Zollner Ianni. 2020. ‘Sexual Desire and Pleasure in the Context of the HIV pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP).’ Sexualities 23 (8): 1400–1416.

- Dawson, Kate, Saoirse Nic Gabhainn and Pádraig MacNeela. 2020. ‘Toward a Model of Porn Literacy: Core Concepts, Rationales, and Approaches.’ The Journal of Sex Research 57 (1): 1–15.

- Demant, Daniel, Leanne Hides, Katherine M White and David J Kavanagh. 2018. ‘Effects of Participation in and Connectedness to the LGBT Community on Substance Use Involvement of Sexual Minority Young People.’ Addictive Behaviors 81: 167–174.

- Ding, Runze and Lin Song. 2023. ‘Queer Cultures in Digital Asia| Digital Sexual Publics: Understanding Do-It-Yourself Gay Porn and Lived Experiences of Sexuality in China.’ International Journal of Communication 17: 16.

- Downing, Martin J, Eric W Schrimshaw, Roberta Scheinmann, Nadav Antebi-Gruszka and Sabina Hirshfield. 2017. ‘Sexually Explicit Media Use by Sexual Identity: A Comparative Analysis of Gay, Bisexual, and Heterosexual men in the United States.’ Archives of Sexual Behavior 46: 1763–1776.

- Eaton, Lisa A, Demetria N Cain, Howard Pope, Jonathan Garcia and Chauncey Cherry. 2011. ‘The Relationship Between Pornography Use and Sexual Behaviours Among at-Risk HIV-Negative Men Who Have Sex with Men.’ Sexual Health 9 (2): 166–170.

- Ford, Jessie V, Esther Corona-Vargas, Mariana Cruz, J Dennis Fortenberry, Eszter Kismodi, Anne Philpott, Eusebio Rubio-Aurioles and Eli Coleman. 2021. ‘The World Association for Sexual Health’s Declaration on Sexual Pleasure: A Technical Guide.’ International Journal of Sexual Health 33 (4): 612–642.

- Frost, David M and Ilan H Meyer. 2012. ‘Measuring Community Connectedness Among Diverse Sexual Minority Populations.’ Journal of sex Research 49 (1): 36–49.

- Goh, Joseph N. 2017. ‘Navigating Sexual Honesty: A Qualitative Study of the Meaning-Making of Pornography Consumption among Gay-Identifying Malaysian men.’ Porn Studies 4 (4): 447–462.

- Gola, Mateusz, Karol Lewczuk and Maciej Skorko. 2016. ‘What Matters: Quantity or Quality of Pornography Use? Psychological and Behavioral Factors of Seeking Treatment for Problematic Pornography Use.’ The Journal of Sexual Medicine 13 (5): 815–824.

- Grov, Christian, Aaron S Breslow, Michael E Newcomb, Joshua G Rosenberger and Jose A Bauermeister. 2014. ‘Gay and Bisexual Men’s Use of the Internet: Research from the 1990s Through 2013.’ The Journal of Sex Research 51 (4): 390–409.

- Grubbs, Joshua B, Nicholas Stauner, Julie J Exline, Kenneth I Pargament and Matthew J Lindberg. 2015a. ‘Perceived Addiction to Internet Pornography and Psychological Distress: Examining Relationships Concurrently and Over Time.’ Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 29 (4): 1056–1067.

- Grubbs, Joshua B, Fred Volk, Julie J Exline and Kenneth I Pargament. 2015b. ‘Internet Pornography Use: Perceived Addiction, Psychological Distress, and the Validation of a Brief Measure.’ Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy 41 (1): 83–106.

- Grubbs, Joshua B, Paul J Wright, Abby L Braden, Joshua A Wilt and Shane W Kraus. 2019. ‘Internet Pornography Use and Sexual Motivation: A Systematic Review and Integration.’ Annals of the International Communication Association 43 (2): 117–155.

- Hald, Gert Martin, Derek Smolenski and B.R. Simon Rosser. 2013. ‘Perceived Effects of Sexually Explicit Media Among Men Who Have Sex with Men and Psychometric Properties of the Pornography Consumption Effects Scale (PCES).’ The Journal of Sexual Medicine 10 (3): 757–767.

- Hald, Gert Martin and Aleksandar Štulhofer. 2016. ‘What Types of Pornography do People Use and do They Cluster? Assessing Types and Categories of Pornography Consumption in a Large-Scale Online Sample.’ The Journal of Sex Research 53 (7): 849–859.

- Hangen, Forrest and Ronald D. Rogge. 2022. ‘Focusing the Conceptualization of Erotophilia and Erotophobia on Global Attitudes Toward Sex: Development and Validation of the Sex Positivity–Negativity Scale.’ Archives of Sexual Behavior 51 (1): 521–545.

- Hanseder, Sophia and Jaya A. R. Dantas. 2023. ‘Males’ Lived Experience with Self-Perceived Pornography Addiction: A Qualitative Study of Problematic Porn Use.’ International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20 (2): 1497.

- Harper, Gary W, Pedro A Serrano, Douglas Bruce and Jose A Bauermeister. 2016. ‘The Internet’s Multiple Roles in Facilitating the Sexual Orientation Identity Development of gay and Bisexual Male Adolescents.’ American Journal of Men’s Health 10 (5): 359–376.

- Jenkins, Henry, Mizuko Ito and danah boyd. 2015. Participatory Culture in a Networked Era: A Conversation on Youth, Learning, Commerce, and Politics. Cambridge, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Jonas, Kai J., Skyler T. Hawk, Danny Vastenburg and Peter de Groot. 2014. ‘“Bareback” Pornography Consumption and Safe-Sex Intentions of Men Having Sex with Men.’ Archives of Sexual Behavior 43: 745–753.

- Kalichman, Seth C and David Rompa. 1995. ‘Sexual Sensation Seeking and Sexual Compulsivity Scales: Validity, and Predicting HIV Risk Behavior.’ Journal of Personality Assessment 65 (3): 586–601.

- Kar, Sujita Kumar, Ananya Choudhury and Abhishek Pratap Singh. 2015. ‘Understanding Normal Development of Adolescent Sexuality: A Bumpy Ride.’ Journal of Human Reproductive Sciences 8 (2): 70.

- Kessler, Ronald and Daniel Mroczek. 1994. Final Versions of Our Non-Specific Psychological Distress Scale. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center of the Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

- Klaassen, Marleen JE and Jochen Peter. 2015. ‘Gender (In)Equality in Internet Pornography: A Content Analysis of Popular Pornographic Internet Videos.’ The Journal of Sex Research 52 (7): 721–735.

- Kohut, Taylor, Rhonda N Balzarini, William A Fisher, Joshua B Grubbs, Lorne Campbell and Nicole Prause. 2020. ‘Surveying Pornography Use: A Shaky Science Resting on Poor Measurement Foundations.’ The Journal of Sex Research 57 (6): 722–742.

- Kubicek, Katrina, William J Beyer, George Weiss, Ellen Iverson and Michele D Kipke. 2010. ‘In the Dark: Young Men’s Stories of Sexual Initiation in the Absence of Relevant Sexual Health Information.’ Health Education & Behavior 37 (2): 243–263.

- Kvalem, Ingela Lundin, Bente Træen and Alex Iantaffi. 2016. ‘Internet Pornography Use, Body Ideals, and Sexual Self-Esteem in Norwegian Gay and Bisexual Men.’ Journal of Homosexuality 63 (4): 522–540.

- Lammers, Joris and Janka I Stoker. 2019. ‘Power Affects Sexual Assertiveness and Sexual Esteem Equally in Women and Men.’ Archives of Sexual Behavior 48: 645–652.

- Levin, Michael E, Jason Lillis and Steven C Hayes. 2012. ‘When is Online Pornography Viewing Problematic Among College Males? Examining the Moderating Role of Experiential Avoidance.’ Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity 19 (3): 168–180.

- McKee, Alan, Paul Byron, Katerina Litsou and Roger Ingham. 2020. ‘An Interdisciplinary Definition of Pornography: Results from a Global Delphi Panel.’ Archives of Sexual Behavior 49 (3): 1085–1091.

- Mennig, Manuel, Sophia Tennie and Antonia Barke. 2022. ‘Self-Perceived Problematic Use of Online Pornography Is Linked to Clinically Relevant Levels of Psychological Distress and Psychopathological Symptoms.’ Archives of Sexual Behavior 51: 1–9.

- Mercer, John. 2017. Gay Pornography: Representations of Sexuality and Masculinity. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Mercer, Catherine H, Clare Tanton, Philip Prah, Bob Erens, Pam Sonnenberg, Soazig Clifton, Wendy Macdowall, Ruth Lewis, Nigel Field and Jessica Datta. 2013. ‘Changes in Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles in Britain Through the Life Course and Over Time: Findings from the National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal).’ The Lancet 382 (9907): 1781–1794.

- Mitchell, Kirstin R., Ruth Lewis, Lucia F. O’Sullivan and J. Dennis Fortenberry. 2021. ‘What is Sexual Wellbeing and Why Does it Matter for Public Health?’ The Lancet Public Health 6 (8): e608–e613.

- Morris, Paul and Susanna Paasonen. 2014. ‘Risk and Utopia: A Dialogue on Pornography.’ GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 20 (3): 215–239.

- Mowlabocus, Sharif. 2016. Gaydar Culture: Gay Men, Technology and Embodiment in the Digital Age. London: Routledge.

- Nelson, Kimberly M, David W Pantalone and Michael P Carey. 2019. ‘Sexual Health Education for Adolescent Males Who Are Interested in Sex with Males: An Investigation of Experiences, Preferences, and Needs.’ Journal of Adolescent Health 64 (1): 36–42.

- Newton, James David Albert, W Kim Halford and Fiona Kate Barlow. 2021. ‘Intimacy in Dyadic Sexually Explicit Media Featuring Men Who Have Sex with Men.’ The Journal of Sex Research 58 (3): 279–291.

- Newton, James David Albert, W Kim Halford, Oscar Oviedo-Trespalacios and Fiona Kate Barlow. 2022. ‘Performer Roles and Behaviors in Dyadic Sexually Explicit Media Featuring Men Who Have Sex with Men.’ Archives of Sexual Behavior 51 (5): 2437–2450.

- Paasonen, Susanna. 2011. Carnal Resonance: Affect and Online Pornography. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Parmenter, Joshua G, Renee V Galliher and Adam DA Maughan. 2022. ‘Contextual Navigation: Towards a Holistic Conceptualization of Negotiating Sexual Identity in Context.’ Emerging Adulthood 10 (4): 993–1007.

- Poole, Jay and Ryan Milligan. 2018. ‘Nettersexuality: The Impact of Internet Pornography on Gay Male Sexual Expression and Identity.’ Sexuality & Culture 22 (4): 1189–1204.

- Prause, Nicole and D. J. Williams. 2020. ‘Groupthink in sex and Pornography “Addiction”: Sex-Negativity, Theoretical Impotence, and Political Manipulation.’ In Groupthink in Science: Greed, Pathological Altruism, Ideology, Competition, and Culture, edited by David M. Allen and James W. Howell, 185–200. Cham: Springer.

- Regnerus, Mark, David Gordon and Joseph Price. 2016. ‘Documenting Pornography Use in America: A Comparative Analysis of Methodological Approaches.’ The Journal of Sex Research 53 (7): 873–881.

- Robards, Brady. 2018. ‘“Totally Straight”: Contested Sexual Identities on Social Media Site Reddit.’ Sexualities 21 (1–2): 49–67.

- Roberts, Leah Marion and Brian D Christens. 2021. ‘Pathways to Well-Being among LGBT Adults: Sociopolitical Involvement, Family Support, Outness, and Community Connectedness with Race/Ethnicity as a Moderator.’ American Journal of Community Psychology 67 (3–4): 405–418.

- Rodda, Simone N and Severi Luoto. 2023. ‘The Feasibility and Impact of a Brief Internet Intervention for Pornography Reduction.’ Sexual Health & Compulsivity 30 (1): 57–80.

- Rosser, B. R. Simon, Derek J Smolenski, Darin Erickson, Alex Iantaffi, Sonya S Brady, Jeremy A Grey, Gert Martin Hald, Keith J Horvath, Gunna Kilian and Bente Træen. 2013. ‘The Effects of gay Sexually Explicit Media on the HIV Risk Behavior of Men Who Have Sex with Men.’ AIDS and Behavior 17: 1488–1498.

- Seif, Ray. 2017. ‘The Media Representation of Fictional Gay and Lesbian Characters on Television: A Qualitative Analysis of US TV-Series Regarding Heteronormativity.’

- Snell, William E Jr, Terri D Fisher and Toni Schuh. 1992. ‘Reliability and Validity of the Sexuality Scale: A Measure of Sexual-Esteem, Sexual-Depression, and Sexual-Preoccupation.’

- Stein, Dylan, Richard Silvera, Robert Hagerty and Michael Marmor. 2012. ‘Viewing Pornography Depicting Unprotected Anal Intercourse: Are There Implications for HIV Prevention Among Men Who Have Sex with Men?’ Archives of Sexual Behavior 41 (2): 411–419.

- Štulhofer, Aleksandar, Vesna Buško and Ivan Landripet. 2010. ‘Pornography, Sexual Socialization, and Satisfaction Among Young Men.’ Archives of Sexual Behavior 39: 168–178.

- Sun, Chyng, Ana Bridges, Jennifer A Johnson and Matthew B Ezzell. 2016. ‘Pornography and the Male Sexual Script: An Analysis of Consumption and Sexual Relations.’ Archives of Sexual Behavior 45 (4): 983–994.

- Sundén, Jenny. 2023. ‘Digital Kink Obscurity: A Sexual Politics Beyond Visibility and Comprehension.’ Sexualities 13634607221124401. Advance online publication.

- Tiidenberg, Katrin. 2019. ‘Playground in Memoriam: Missing the Pleasures of NSFW Tumblr.’ Porn Studies 6 (3): 363–371.

- Tiidenberg, Katrin and Emily van der Nagel. 2020. ‘Sexual Practices on Social Media.' In Sex and Social Media, 79–108. Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Tylka, Tracy L. 2015. ‘No Harm in Looking, Right? Men’s Pornography Consumption, Body Image, and Well-Being.’ Psychology of Men & Masculinity 16 (1): 97–107.

- Vörös, Florian. 2014. Raw Fantasies. An Interpretative Sociology of What Bareback Porn Does and Means to French gay Male Audiences. Oxford: Peter Lang.

- Wang, Yidong. 2021. ‘The Twink Next Door, Who Also Does Porn: Networked Intimacy in Gay Porn Performers’ Self-Presentation on Social Media.’ Porn Studies 8 (2): 224–238.

- Whitfield, Thomas HF, H Jonathon Rendina, Christian Grov and Jeffrey T Parsons. 2018. ‘Viewing Sexually Explicit Media and Its Association with Mental Health Among Gay and Bisexual Men Across the U.S.’ Archives of Sexual Behavior 47: 1163–1172.

- Williams, D. J. 2017. ‘The Framing of Frequent Sexual Behavior and/or Pornography Viewing as Addiction: Some Concerns for Social Work.’ Journal of Social Work 17 (5): 616–623.