Abstract

This paper examines Korea’s economic growth in the 2000s, with a focus on the growth model. Korea sustained relatively high growth for two decades after the 1997 crisis, primarily due to the rapid increase in exports to China. However, inequality rose and the wage share fell during the early part of this period, leading to the criticism in the mid- 2010s. The former Moon government introduced an “income-led growth” strategy aimed at increasing wages and household income to stimulate economic growth. Although it reduced income inequality, its effectiveness in promoting economic growth was limited because of the changes in the global economy and constraints in fiscal stimulus. Considering the shift in the global economic order associated with geopolitical tensions, Korea should transit to a growth model led domestic demand, with an enhanced role of the state, for stable economic growth.

Introduction

The Korean economy has surprised many by continuing relatively rapid economic growth in the 2000s and emerging as an industrial powerhouse in several critical industries. This was contrary to concerns raised by progressive economists who argued that neoliberal economic restructuring after the 1997 crisis would stagnate the economy and increase inequality (Crotty and Lee Citation2002). Though inequality did rise, Korea managed to increase exports and sustain growth until the recent period. However, its growth prospects have become uncertain due to the US-China conflict and fundamental changes in the global economic order.

This paper examines the experience of economic growth in Korea after the 2000s, focusing on the growth model and the role of the global economy, along with the recent experience of the income-led growth strategy. Korea’s successful economic growth for 20 years was closely associated with the increase in intermediate and capital goods exports to China. The rise of China provided an opportunity for the Korean economy to thrive based on an export-led economic growth model, similar to past experiences. However, the export-led growth model had issues related to depressing wages and rising inequality, leading to stagnation of domestic consumption. Consequently, the Moon Jae-In government, starting in 2017, introduced the income-led growth plan aimed at increasing the wage share and improving income distribution to promote economic growth. While this resulted in a fall in income inequality, it did not achieve success in promoting economic growth. The new Yoon Suk Yeol government is currently resorting to conservative trickle-down economics with deregulation and tax cuts.

However, the recent change in the global economy, referred to as “slowbalization” or even deglobalization, presents serious concerns for the Korean economy. Unfavorable external environments, associated with the geopolitical tension between the US and China, pose challenges to sustaining growth through exports. Given this global transformation, Korea should make efforts to decrease its dependence on exports and promote a domestic demand-led growth model to achieve a more balanced and stable economic growth. A new growth model should be centered on promoting domestic consumption through reducing inequality and strengthening the role of the state. The lessons drawn from the experience of income-led growth emphasize the necessity of political and ideological changes to support active fiscal stimulus and public investment for this new approach.

This paper is organized as follows. Section “Economic growth in the 2000s and rising China” examines Korea’s growth experience in the 2000s and the role of rising China. Section “The experience of income-led growth under the Moon government” presents a brief evaluation of the liberal Moon government’s strategy called income-led growth and discusses its lessons. Section “The end of globalization and the growth model in Korea” discusses the implications of the current changes in the global economic order and the need for a domestic demand-led growth model in Korea.

Economic growth in the 2000s and rising China

The 1997 financial crisis was a huge shock to the Korean economy, marking the largest economic crisis leading to the IMF bailout of $57 billion. As Crotty and Lee (Citation2009) argued, the Korean government accepted the mainstream view that the crisis was because of a dysfunction of the old East Asian growth model, even though it was primarily caused by the problem of reckless financial opening and the end of state-led financial system. The government introduced neoliberal market-led economic reforms, such as corporate restructuring to reduce the debt ratio, significant financial restructuring involving substantial public fund, and labor market flexibilization measures. Progressives were concerned that this post-crisis restructuring would put an end to the formerly successful growth model, leading to a reduction in growth while exacerbating income inequality (Crotty and Lee Citation2002).

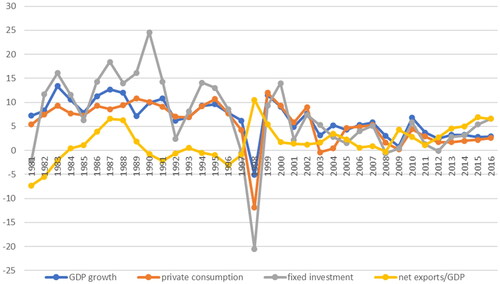

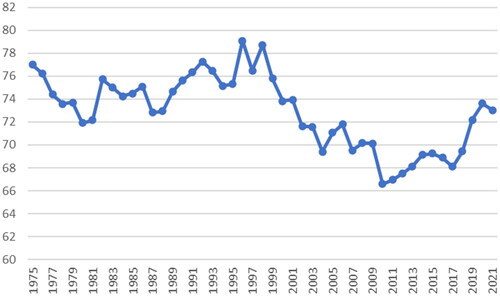

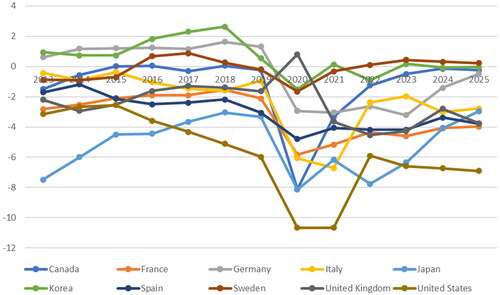

However, the Korean economy continued to grow relatively well, outpacing other advanced countries as demonstrates. Several factors contributed to this success, including the surprising resilience of big business groups in Korea, known as Chaebol, and the effective government policy, such as the promotion of the IT (Information Technology) industry. It is important to note, however, that changes in the global economy played a crucial role in successful economic growth in the 2000s. The rapid recovery after the 1997 crisis was attributed to the surge in exports, facilitated by a large depreciation of the currency, as well as the economic boom in the global economy, led by the US new economy boom. The Korean economy experienced fast export growth in 1999–2000, resulting in a substantial current account surplus.

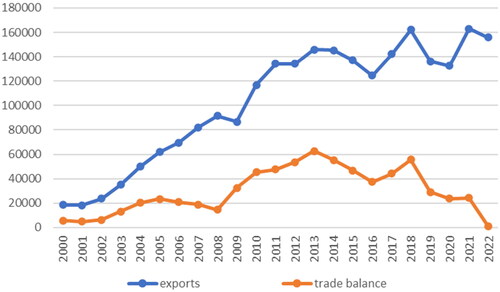

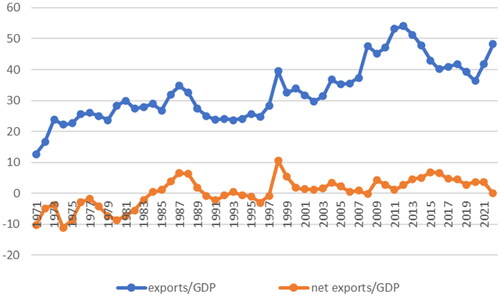

After the early 2000s, the rise of China contributed to the persistent economic growth of Korea. The Korean economy significantly increased exports to China together with outward foreign direct investment throughout the 2000s. The Chinese economy had become integrated closely into the global economy after joining the WTO in 2001. Its manufacturing exports to the world market soared in the 2000s and China became the factory of the world. In this process, the Chinese economy imported intermediate and capital goods from Korea on a massive scale, which stimulated exports and economic growth in Korea in the 2000s as shown in . Exports once again became crucial for growth in Korea, and the Korean government emphasized international competitiveness. The exports as a percent of GDP in Korea rose from 28.6% in 2002, to 47.6% in 2008. The trade balance turned surplus in the 2000s, in contrast to the continuous deficit in the 1990s. This was associated with the relative decline in domestic investment and the increase in exports to China in part. Several Chaebol groups in Korea, such as Samsung and Hyundai, experienced rapid growth related to the rising exports to China in the 2000s.Footnote1 This experience was also related to global imbalances in which East Asia, including China and Korea, along with Germany and oil producers, ran huge trade surpluses, while the US ran a significant deficit (Lee Citation2012).

After the global financial crisis, this trend intensified, contributing to persistent economic growth in Korea. The exports as a percent of GDP reached their peak in the early 2010s at 54.1% in 2011, while the current account balance as a percentage of GDP reached its peak in the mid-2010s, as shows. Remarkably, this was in contrast with the global trend, in which the ratio of global exports to global GDP started to stagnate after the global financial crisis. Specifically, the exports to China kept increasing in the 2010s. The massive stimulus measures introduced in China during the global financial crisis facilitated the global economic recovery and contributed to the increase in exports from Korea. Furthermore, the share of China’s exports in the global exports of goods rose from about 9% in 2007 to about 12% in 2013, with China becoming a main player in several manufacturing industries (Nicita and Razo Citation2021, 1). This helped the Korean companies to continue to increase exports, mostly capital goods. Thus, the Korean economy achieved export-dependent economic growth in the 2010s thanks to the rise of China. Korea also increased outward FDI (Foreign Direct Investment) to China, as Korean companies established factories in China to sell their products in the Chinese market and to provide intermediate goods for Chinese companies. The increase in FDI from Korea to China promoted exports to China because they procured parts and intermediate goods from Korea. However, after 2013, the export growth from Korea to China became stagnant and the share of exports out of GDP in Korea also experienced a decline. Meanwhile, the share of net exports out of GDP was the highest in the mid-2010s and gradually fell after then.

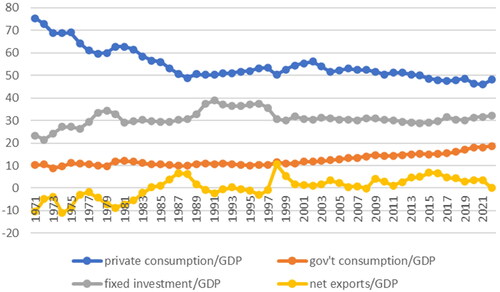

Contrary to exports, the role of private domestic demand, particularly consumption, in economic growth became smaller after the 2000s as income inequality rose and the wage share declined, as shown in . Even in the mid-2010s, when inequality improved to some extent, the share of consumption in Korea continued to decline, down to less than 50% of GDP, significantly lower than that of other advanced countries. In contrast, the shares of government consumption and net exports have been steadily increasing since 2000. This suggests that economic growth in Korea after the 2000s was still strongly driven by exports, particularly to China, that offset the stagnation of domestic consumption. The pattern of rapid economic growth that had been observed before 1997 repeated in Korea during the 2000s again. The investment growth fell in the aftermath of the 1997 crisis and economic restructuring, and structural factors such as an aging population exerted the downward pressure on the productivity and economic growth. However, the growth slowdown was not severe in the 2000s thanks to the pivotal role of exports (Ahn Citation2005).Footnote2 In a sense, the Korean economy was fortunate then, somehow sailing with the favorite wind of the global economy

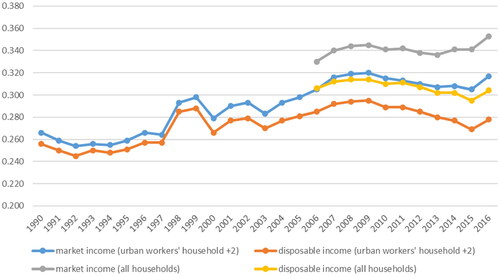

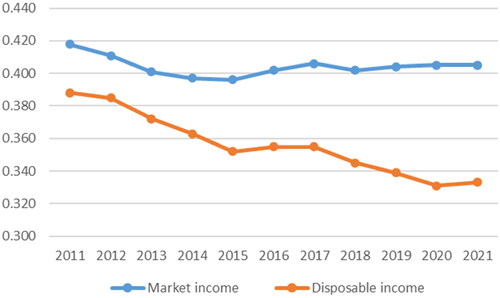

However, this implies that economic growth in Korea could be affected by the global economic change to a great extent, potentially becoming unstable especially when international trade did not grow or China caught up with Korea in the capital goods industry. Furthermore, this growth pattern was associated with a depression of wages, and it was one of the reasons why domestic consumption stagnated throughout the 2000s. This, in turn, raised a concern about the rise in inequality and its negative impact on aggregate demand and growth in the mid-2010s. and demonstrate that income inequality rose sharply and the wage share of workers fell significantly in the 2000s after the 1997 crisis, although there was some improvement after the recovery from the global financial crisis. The export-dependent growth pattern in Korea favored capital and increased the profit share, exacerbating income inequality. Notably, there was a serious problem of poverty with the relative poverty rate as high as 17.6% in 2016 according to the OECD. Many low-wage workers experienced hardship. In 2016, the share of low-wage workers receiving less than 2/3 of median wage in Korea stood at 23.5%, one of the highest among OECD countries. In contrast, the high-wage workers fared well, with the top 10% income share being high compared to other advanced countries.

Figure 5. The Gini coefficients in Korea.

Source: Statistics Korea.

Note: This is from the Household Income and Expenditure Survey.

Consequently, a call for progressive economic changes emerged, with the aim of achieving a balance between capital and labor, as well as between external demand and domestic demand in the Korean economy. More Korean people demanded a reduction in income inequality and the redistribution of income from profits of large Chaebol companies to the wages of vulnerable workers, primarily employed by smaller contractor companies in the mid-2010s. This movement was often referred to as “economic democratization”.

The experience of income-led growth under the Moon government

Income-Led growth: a Korean version of wage-led growth

The conservative Park government came into power in 2013, partly embracing the agenda of economic democratization as a political slogan. However, its economic policy remained largely conservative, with measures like tax cuts, deregulation and the establishment of the rule of law. The economic growth record was mediocre, while there was progress in improvement of household income distribution. This was closely related to the introduction of the pension system for the elderly. The president, who was the daughter of General Park, became embroiled in political scandals, some of which involved Chaebol owners, leading to the anger of people and her impeachment.

The liberal Moon Jae-In government was elected in 2017, shortly after these incidents. It criticized the two consecutive former governments for adopting trickle-down economics and persisting with the export-led growth model. It argued that this resulted in a depression of workers’ wages and domestic demand in general, and Korea needed a change in its growth model. The Moon government introduced progressive income-led growth, which was a Korean version of wage-led growth advocated by Post-Keynesian macroeconomists and the ILO (International Labor Organization), calling it a new economic paradigm. They argued that an increase in the wage share could increase aggregate demand when its positive effect on consumption outweighed its negative effect on investment and possibly net exports (Lavoie and Stockhammer Citation2013; Onaran and Galanis Citation2014). This is a wage-led economy, and several empirical studies reported that Korea was a wage-led regime after the 1997 crisis (Lee Citation2018). However, the share of self-employed was very high, accounting for about 25% of all employed individuals in 2016, which was much higher than that in other OECD countries. Additionally, the role of income redistribution by the government was quite limited, with the public social expenditure only about 10% of GDP in 2017, just half of the OECD average. This is why the Moon government named its new growth model “income-led growth” in which the government aimed to boost aggregate demand and growth by increasing wages and household incomes. This approach aligned with the concept of domestic demand-led growth advocated by progressive macroeconomists who criticized the sustainability of the export-led growth model (Palley Citation2012). It was also broadly consistent with the idea of inclusive growth promoted by international organizations after the global financial crisis (G20 Citation2017).Footnote3

The income-led growth plan by the Moon government consisted of three main policy categories including an increase in household income, expansion of social safety net and welfare, and reduction of living costs (The Committee of Income-Led Growth Citation2018). The government raised the minimum wage by 16.4% in 2018 and 10.8% in 2019, while providing benefits, known as the job stability fund, to small companies that hired minimum wage workers, and increased the EITC (Earned Income Tax Credit) to promote household income. There was also an effort to provide subsidies for social insurance premium and to reduce credit card fee for the self-employed. The government expanded social welfare by raising the elderly pension benefit, introducing child benefits, and expanding the scale and scope of the unemployment insurance. Finally, the government reduced the costs of medical care, child care and housing. Public social expenditure as a share of GDP increased from 10.1% in 2017 to 12.3% in 2019 and 14.4% in 2020.Footnote4

This progressive policy faced harsh criticism by economists and the media, as conservative mainstream economists were dominant and the media was also biased in favor of capital in Korea. The voice of opposition became especially pronounced when the increase in jobs in 2018 amounted to just about a third of those in 2017. Many argued that the rapid rise in minimum wage in 2018 was responsible for this. Moreover, the result of the Household Income and Expenditure Survey indicated that income inequality rose rapidly in 2018, further worsening public opinion on income-led growth. Amidst heated confusion and debates, the Moon government’s commitment to promoting income-led growth weakened in mid-2018, leading to the replacement of the president’s economic advisor, who had strongly supported income-led growth, in June.

However, in terms of income inequality, significant progress was made. The Household Income and Expenditure Survey had several problems including a significant change in the sample and population group in 2018. It was also a quarterly survey, with limitations in accurately capturing real changes in inequality due to income fluctuations, especially among the self-employed, across quarters. The official income inequality statistics were already changed to the new and better survey, called the Survey of Household Finances and Living Conditions in 2016, but the results for 2018 were not published until December 2019. According to it, income inequality clearly improved in 2018 and 2019, as shown in . Moreover, the share of low-wage workers who earn less than 2/3 of median wage fell from 22.3% in 2017 to 19% in 2018 and 17% in 2019, alongside a significant reduction in wage inequality. The wage share after adjusting for the income of self-employed also rose from 68.1% in 2017 to 72.2% in 2019, as depicted in . Regarding the employment effect of the minimum wage, we should consider changes in population, such as the decline in the working-age population in 2018, as well as specific trends in each industry into account.Footnote5 In fact, several empirical studies report mixed results of the negative impact of minimum wage on employment in 2018 and 2019 (Joo et al. Citation2020). This suggests that the Moon government was successful, at least in the “income-led” aspect of income-led growth, which differs from the harsh criticism by conservatives who argued that income-led growth worsened income distribution.

Figure 6. Gini coefficients in Korea after the Moon government.

Source: Statistics Korea.

Note: This is based on the Survey of Household Finances and Living Conditions.

While there was an improvement in income inequality, the issue of wealth inequality and concentration became more severe because of the rapid increase in real estate market prices. The price of apartments in Seoul nearly doubled between 2017 and 2021, leading to greater wealth concentration. The share of the top 10% of households in net wealth ownership in Korea rose from 41.8% in 2017 to 43.7% in 2020, and the Gini coefficient of net wealth also increased from 0.584 in 2017 to 0.603 in 2021 (Statistics Korea Citation2022). Particularly noteworthy is the very high real estate prices compared to income, which is significantly higher than in other advanced countries. The ratio of total net national wealth to net national income was 9.5 in 2017, and it rose to 11.9 in 2021 due to the rapid increase in housing prices, with the majority of wealth being real estate in Korea. The Korean government initially failed to implement effective taxation on real estate in 2017. Later, it raised real estate tax rates on households owning more than two houses, but the tax burden increased due to the real estate market bubble, resulting in public anger against the government. The Korean people became deeply disappointed by the government’s real estate policy, which was one of the important reasons for its substantial loss of political support.

Unsuccessful growth and its reasons

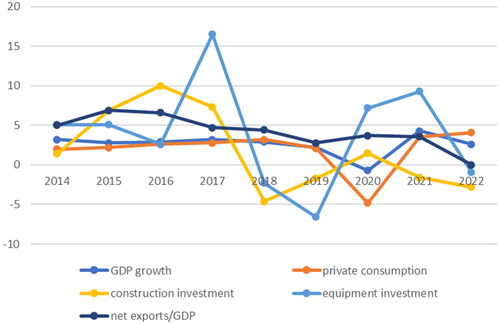

Most importantly, the government was not successful in spurring economic growth, primarily due to a decline in fixed investment, including equipment and construction investment in 2018 and 2019. The economic growth rate fell from 3.2% in 2017 to 2.9% and 2.2% in 2018 and 2019, respectively, with fixed investment recording negative growth, as illustrated in .

A decline in equipment investment in 2018 partly reflects the base effect because it had risen significantly in 2017. However, its drop in 2018 and, particularly, 2019 was closely associated with the change in exports to the global market and the cycle of the semiconductor industry. Korean exports increased by 15.8% in 2017 but only by 5.4% in 2018 and −10.4% in 2019. The semiconductor industry’s exports surged by 64.7% in 2017 due to the global boom in the industry, contributing to relatively high economic growth that year. However, this growth was not sustainable, given the looming possibility of a downward cycle in this sector from 2019. Exports of Korea’s semiconductor industry still increased by 27.5% in 2018 but declined by −28% in 2019, leading to a significant reduction in investment growth in 2018. In fact, equipment investment in the semiconductor industry soared by about 66% in 2017, but its growth stagnated at 11% in 2018 and −13% in 2019.Footnote6 The growth of equipment investment in the consumer electronics and petrochemical industry also increased rapidly in 2017 but declined in 2018 and 2019. Statistics Korea also reports that the growth of the index of machinery and equipment investment was 20% in 2017 but fell to −5.3% in 2018 and −10.2% in 2019. Among others, the growth rate of special industrial machinery and equipment, which includes the equipment used in semiconductor production, rose greatly by 46.1% in 2017 but declined sharply to −143% in 2018 and −26.2% in 2019.

Construction investment, which exceeded equipment investment in Korea in terms of its amount, also fell sharply in 2018 and 2019. The Moon government implemented stricter regulations on lending related to real estate, reversing policies from the previous conservative government. This led to a slowdown in the real estate sector, which had a negative impact on construction investment. Although the investment growth for knowledge and reproduction did not, total fixed investment growth was −2.2% in 2018 and −2.1% in 2019. The increase in wage share and the decrease in income inequality supported solid consumption growth in 2018. According to the Bank of Korea, the contribution of private consumption to economic growth did indeed become larger than before with its share approximately 52% of total growth in 2018, though it experienced a slight decline in 2019. However, the improvement in inequality was not substantial enough to significantly boost consumption and growth, offsetting the decline in investment due to external factors. Additionally, the persistently high and increased household debt and rapid aging have depressed private consumption in Korea. It will take more time for the structural changes in the economy to stimulate growth, and the role of domestic demand in driving growth was limited because the Korean economy still heavily relied on exports.

It should be noted that the disappointing growth record was partly associated with a failure in fiscal policy. There was de facto fiscal austerity in 2018 due to a significant and unexpected increase in tax revenue. Although the Moon government argued that it was in line with Keynesian principles, it failed to introduce fiscal stimulus when the economy sharply slowed down in late 2018 (Joo et al. Citation2020). Specifically, the government reduced the budget for SOC (Social Overhead Capital) by 14%, and government construction investment also decreased by about 1% in 2018. Fiscal stimulus was also necessary to mitigate the potential shock of income-led growth policies, such as the rapid increase in the minimum wage. However, in 2018, the government fiscal balance recorded a surplus of 1.6% of GDP, the largest surplus since 2007. This was mainly due to tax revenue increase of about 1.4% of GDP more than the government’s original budget for 2018. Although the government could have anticipated much larger tax revenue than the budget in mid-2018, it did not implement a supplementary budget in late 2018, effectively resulting in de facto austerity. demonstrates the government structural balance as a percentage of potential GDP, after adjusting for cyclical effects, which provides a better measure for fiscal policy stance. It recorded a substantial surplus of 2.6% of GDP in 2018. In 2019, fiscal policy became more expansionary, yet the size of the supplementary budget introduced by the government was still smaller than the recommendation made by the IMF.

Figure 9. Government Structural Balance as a Percentage of Potential GDP.

Source: World Economic Outlook Database, March 2023, IMF.

This failure in fiscal policy in the Moon government reflected the strong influence of conservative government officials and ideology, which resisted increasing government debt. While the share of gross public debt as a percentage of GDP was less than 40% in 2018, considerably lower than that in other advanced countries, concerns about fiscal deficits and rising government debt persisted among officials and the Korean people. The president and his advisors in the presidential office could not overcome this, facing strong resistance by officials in the Ministry of Economy and Finance. This stance contradicted even mainstream macroeconomic arguments that support fiscal stimulus, based on the finding that the fiscal multiplier is large, particularly in the case of public investment (Furman Citation2016). Recent macroeconomic studies also suggest that excessive worry about fiscal deficits is unwarranted when the growth rate is higher than the interest rate (Blanchard Citation2019). Furthermore, it is argued that the hysteresis effect can reduce productivity and potential GDP growth when the government does not combat economic recession with strong fiscal stimulus, leading to long-term unemployment and a decline in investment in new technology (Blanchard Citation2019; Cerra, Fatas, and Saxena Citation2020). The stance of fiscal policy in the Moon government was ironically contrary to Keynesian principles, even though it implemented a Post-Keynesian growth strategy.

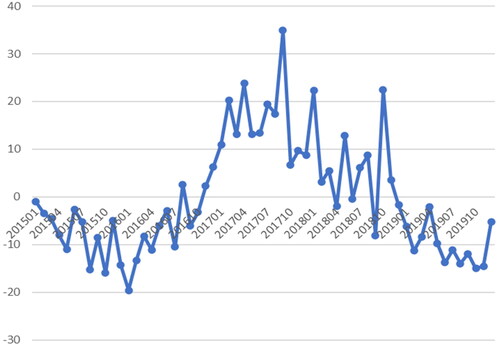

Another significant factor that hindered economic growth after 2018 was a shift in the global economy, particularly a stagnation in international trade, associated with the US-China conflict. The escalation of the US-China conflict, involving technology and trade, resulted in stagnation in international trade in 2019. This had a substantial impact on Korean exports, contributing to a marked decline in economic growth. While export growth in Korea was exceptionally rapid in 2017, it dropped to approximately −10% in 2019 in dollar terms, although it remained 0.2% in Korean currency, as depicted in .

Figure 10. Growth Rates of Export in Korea.

Source: Korea Customs Service.

Note: compared with the previous year.

The shock from the global market, which reduced exports, led to a significant decline in corporate investment, as we discussed earlier. This highlights that capital accumulation in Korea, which is a crucial driver of economic growth, was still strongly influenced by the international economic situation. This was because the economic growth pattern in Korea was export-dependent, with a consistently increasing share of exports in GDP. Consequently, it was challenging for the income-led growth strategy to achieve success in terms of economic growth, especially under unfavorable global economic conditions. Transforming the structure of the Korean economy toward one that relies more on domestic demand would require more time and sustained efforts. However, the global economy did not provide a favorable environment, fiscal stimulus was limited, and the disappointing growth performance harmed public opinion regarding income-led growth. By 2019, the government appeared to step back from the income-led growth approach.Footnote7

The end of globalization and the growth model in Korea

Changes of the global economic order

The Korean economy experienced a relatively mild economic recession in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a GDP growth rate of −0.7%, thanks to the successful control of the pandemic compared to other advanced countries. Both the fiscal deficit and the increase in public debt were significantly lower than those in other countries. However, it is worth noting that once again, the Moon government was less proactive in implementing fiscal stimulus measures during the pandemic compared to other advanced countries. While this can be partly attributed to Korea’s success in containing the epidemic and experiencing relatively higher growth, it remains true that the Korean government did not exert enough efforts to support income and jobs for its citizens. Governments in advanced countries, on average, spent 11.7% of GDP in response to the pandemic, while Korea’s spending stood at 6.4% (IMF Citation2021). also demonstrates that the extent of the structural budget in Korea was much smaller than that in other advanced countries in 2020. Consequently, many self-employed individuals in Korea faced severe hardships, and the already high level of private debt as a percentage of GDP increased even further after the pandemic, setting it apart from other developed countries.Footnote8 This, in turn, contributed to public disapproval of the government, particularly among the self-employed, who bore the brunt the economic shock of the pandemic disproportionately.

In the 2022 presidential election, the Korean people elected the conservative candidate, Yoon Suk Yeol as president by a tiny margin. This choice was partially associated with the disappointment with the former Moon government and negative public sentiment surrounding income-led growth. Despite the international praise for the government’s handling of the pandemic, there was harsh criticism of the Moon government’s real estate market policy and other issues. The conservative media was very influential and the self-employed expressed discontent during the pandemic. It was the new Yoon government that, albeit belatedly, introduced a large supplementary budget, about 2% of GDP, in May 2022, with the aim of compensating for the losses suffered by the self-employed.

The new Korean government and the Korean economy have encountered a formidable challenge and external shock following the pandemic. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, the geopolitical tensions have escalated, particularly driven by the US adopting a more hawkish stance, prioritizing economic security vis-à-vis China and its allies. Nations worldwide have learned from the pandemic that a global supply chain, predicated on extreme efficiency through globalization, poses risks to national security. The war has accentuated these concerns, prompting many Western countries to emphasize resilience and security over economic efficiency. The shift implies a fundamental change in the previous global economic order, characterized by globalization and free markets, raising questions about the future of globalization.

According to Goldberg and Reed (Citation2023), a noticeable shift in US policy occurred after the Russo-Ukraine war. The Biden administration enacted the Chips and Science Act and Inflation Reduction Act, both aimed at reducing China’s presence in the global supply chain, particularly in high-tech industries like semiconductors and renewable energy. China had vigorously pursued catching up with the US in these strategic industries, achieving significant success in bolstering its domestic industry. It is reported that China’s scientific research and technology levels are now on par with those of the US, encompassing fields such as AI (artificial intelligence), space technology, and others. Consequently, the US government is actively seeking to curb China’s ascent in critical technologies, notably the semiconductor industry, through trade regulations. In October 2022, the US introduced export regulations targeting the semiconductor industry concerning China, prompting ally countries, including the Netherlands and Japan, to follow suit with their export controls on China in 2023. China, in response, initiated regulations governing the usage of semiconductors produced by Micron in May 2023 and introduced controls on the export of vital semiconductor materials. This shift may indicate a fundamental transformation from the globalization that has prevailed over the past three decades. Globalization has been driven by increased international trade and investment, coupled with economic liberalization and opening. During the process of globalization, numerous emerging markets and developing economies achieved rapid economic growth and poverty reduction, although financial globalization and liberalization triggered crises in several countries. Korea, for instance, served as an exemplary case, greatly benefiting, particularly from China’s rapid development after the 2000s.

The current change may not necessarily signify the end of globalization or deglobalization, considering other aspects of globalization beyond international goods trade and the limitation of reshoring in the US.Footnote9 However, many argue that at least the era of hyperglobalization, meaning the rapid growth in exports after the 1990s, is over. According to Subramanian, Kessler, and Properzl (Citation2023), the end of the two-decade-long hyperglobalization is undeniable. They argue that its successor is deglobalization in goods trade and continuing, albeit slow, globalization in services trade. Garcia-Herrero (Citation2022) also argues that there is a trend toward slowbalization in every aspect including international trade, foreign investment, and technology. This started in 2008, fueled recently by the strategic competition between the US and China, and the pandemic and the war as well. For example, the number of export regulations significantly increased in the more recent period since 2018 alongside geopolitical fragmentation, leading to slowbalization (Aiyar et al. Citation2023). Thus, we are likely witnessing the emergence of a different international order, one that is more fragmented into two large blocks, departing from the former neoliberal globalization of the past 30 years. The systemic change is led by the US government, and in a recent speech, Sullivan referred to this as the “new Washington Consensus” (Sullivan Citation2023). He argued that market fundamentalism was flawed, and the Biden administration introduced a new industrial policy aimed at fostering inclusive and sustainable economic development. This policy involves promoting strategic industries such as semiconductors and clean energy, with multiple objectives including the creation of manufacturing jobs, leading the high-tech industry, ensuring national security, and addressing the climate crisis. To achieve these goals, the US government has committed to substantial public investment. The EU and Japan have also implemented industrial policies to promote the green industry and semiconductor industry, providing government subsidies. The external policy of the US seeks to reshape the global supply chain by excluding China in strategic areas due to national security concerns (Sullivan Citation2023). In fact, the White House released a national security report in October 2022 and promptly implemented semiconductor export controls targeting China. This shift in the Biden administration is expected to escalate tensions between the US and China, further dividing the global economy. However, the potential costs could be substantial. According to the IMF, the cost of severe trade fragmentation could amount to up to 7% of GDP, and even more with the addition of technological decoupling in some countries (Aiyar et al. Citation2023).

The uncertain future and the need for domestic demand-led growth in Korea

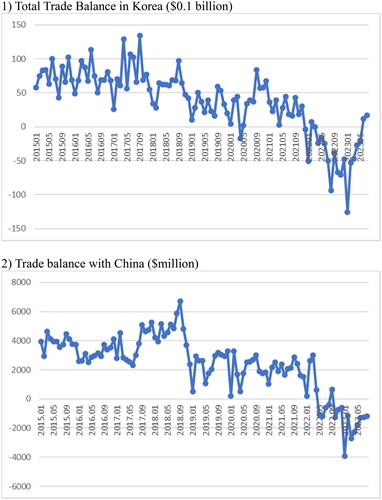

In addition to this fundamental change in the global economy that brings deep uncertainly, China’s economic development has also posed a great challenge to Korea. In the very recent period, China reduced imports from Korea significantly as it successfully developed its domestic capital and intermediate goods industry, which replaced imports from Korea. Korean companies lost competitiveness in the Chinese market, as Chinese companies caught up with them, driven by the Chinese government’s industrial policy. Exports from Korea to China declined from $162.1 billion in 2018 to $136.2 billion in 2019 by 16%. Approximately 82% of this decline was attributed to the reduction in exports of intermediate goods, particularly in sectors like information and communication technology (Yang Citation2020). Exports to China rebounded to $162.9 billion in 2021 but subsequently fell again to $155.8 billion in 2022. By 2023 August, exports to China fell by about 25% compared to the same period in 2022. This primarily stemmed from the stagnation of the Chinese economy after the pandemic, but the trend of China relying less on exports from Korea continued. Geopolitical tensions in the global economy played a role, leading to a substantially negative effect on Korean exports to China after 2022. The new Yoon Suk Yeol government adopted a strong pro-US and anti-China position in foreign affairs, cooperating with the US initiative to curtail China’s influence in the semiconductor industry. This is another factor contributing to the decline in Korean exports to China. Korea experienced a continuous decline in exports from October 2022 to August 2023 compared to the previous year. It also sustained a deficit for 14 consecutive months from April 2022 to May 2023, primarily due to the significant decrease in exports and the trade deficit with China, as illustrated in .

Figure 11. Trade balance in Korea 1) Total Trade Balance in Korea ($0.1 billion) 2) Trade balance with China ($million).

Source: Korea Customs Service.

The impact of the China shock on Korean exports became evident after 2022. According to a study, the decrease in exports to China accounted for 58.5% and 57.5% of the total export decrease in the fourth quarter of 2022 and the first quarter of 2023, respectively (Cho Citation2023). The Korean economy diversified its exports by increasing exports to the US, India and Australia. Consequently, the share of exports to China continued to decline from 25.3% in 2021 to 19.5% in the first quarter of 2023, as illustrated in . The decrease affected all categories of goods, including capital goods, consumer goods, and intermediate goods. However, the most significant decline in exports to China was observed in the capital goods category. Exports to China in the capital goods category fell by about 30% in 2022 and about 40% in the first quarter of 2023, leading to a drop in its share of total capital goods exports. In terms of the total amount, exports of intermediate goods to China remained the largest. The share of these exports to China in total exports of intermediate goods also declined from 27.9% in 2021 to 23.4% in the first quarter of 2023.

Table 1. Exports to China and its share in all exports ($0.1 billion, %).

Due to the shock in the exports to China, associated with geopolitical conflict and shifts in the global economy, the growth rate in Korea is expected to drop significantly, with the IMF projecting it as low as 1.4% in 2023. In response, the Korean government should endeavor to devise a wise approach in managing its relations between the US and China, striking a balance between security and the economy. Regrettably, the Korean government has yet to demonstrate the capacity to effectively respond to and mitigate this external shock. It has predominantly reverted to outdated trickle-down economics by implementing tax cuts and adopting fiscal consolidation measures. This stands in stark contrast to the approach taken by other advanced countries, such as the US, which embraced industrial policy and increased public investment. In 2023, tax revenues are anticipated to fall short of the original budget by about 2.5% of GDP and roughly 15% of the total budget, due to economic stagnation and tax cuts. The Yoon government has introduced an exceptionally restrictive budget for 2024, with the increase being smaller than the nominal GDP, resulting in significant reductions in critical areas of the budget, such as R&D. The potential outcome could entail further economic stagnation and a rise in inequality. In terms of foreign affairs, Seoul has exclusively adopted a pro-US and anti-China approach in its dealings with the US and China. Many are concerned that this could worsen the negative economic effects stemming from the decline in exports to China.

Given the stagnation of globalization associated with geopolitical tension, and the less dependence of China on exports from Korea, coupled with prospects of lower economic growth in China, the Korean economy should make efforts to change its growth model based on exports. The export-led growth model have become increasingly unsustainable for emerging market countries in the 2010s, driven by factors including the saturation of debt in advanced countries and the larger size of the emerging market countries (Palley Citation2012). Despite the onset of secular stagnation in advanced countries, Korea achieved relative success in this respect, largely thanks to China. However, the recent change in the global order poses a serious challenge to Korea in the 2020s if it continues to rely heavily on exports as a driver for growth. The export-led growth model may have reached its limits and may no longer be conducive to stable economic growth in Korea, as Palley (Citation2012) argued.

This suggests that Koreans should establish a new paradigm of more domestic demand-led growth by promoting consumption rather than exports. This can be achieved through the reduction of income inequality, along with enhanced government redistribution through higher taxation and more social welfare, and increased wages for vulnerable workers. There is also a call for a more active fiscal role of the government, including the management of economic cycles and the promotion of public investment to address challenges related to population and climate change. It is crucial to increase the birth rate, which was only 0.78 in 2022, and reduce the high elderly poverty rate, which stood at 38% in 2021. Productive public investment in Research and Development (R&D) and infrastructure for promoting green industries, for example, could also effectively stimulate economic growth with large multiplier effects, especially amid high uncertainty (Abiad, Furceri, and Topalova Citation2016; IMF Citation2020).Footnote10

In this context, the previous experience of income-led growth during the Moon government provides important lessons. Political efforts aimed at pushing conservative government officials to support active public investment and gaining public endorsement are essential. Changing the prevailing economic idea is also crucial, moving toward a progressive one to support the role of the government that improves distribution and promotes aggregate demand, and develops new industries. Fundamentally, Koreans should strive to bring about a genuine shift in political power to empower vulnerable workers and to counter the strong influence of capital for the successful transformation of the growth model.

Conclusions

This paper examines economic growth in Korea after the 2000s, including its relative success attributed to China and the income-led growth experience. Korea continued to grow after the 1997 financial crisis, driven by increased exports to China. However, this resulted in rising inequality and an imbalance between capital and labor, prompting demands for a change in the growth model by the Korean population. The Moon Jae-In government implemented income-led growth with the aim of increasing wages and household income, based on Post-Keynesian wage-led growth. Although it succeeded in improving income distribution, it did not lead to a boost in economic growth because of a decline in fixed capital investment. In particular, the decline in exports associated with the US-China conflict contributed to this. This suggests that external constraints played an important role in the success of domestic demand-led growth, particularly in an economy that relies on exports. It is noteworthy that the government did not exert substantial efforts for fiscal stimulus to manage economic cycles and to complement the income-led growth policy.

The more recent changes in the global economy, due to the retreat of globalization and the reduced dependence of China on Korea’s exports, pose a significant challenge to the Korean economy. The Korean economy is expected to experience a slowdown of economic growth in 2023 primarily due to a recent decline in exports to China. If the current trend continues, the prospect of economic growth in Korea will remain bleak. It is time for Koreans to change their growth model to one led by domestic consumption, drawing lessons from the experience of income-led growth. However, the current conservative government has pursued an opposite policy direction, implementing fiscal consolidation, austerity measures, and tax cuts. This raises a concern about economic stagnation and worsening income distribution.

This paper argues that Korea should transition from its export-led growth model to one more led by domestic demand, considering the ongoing shift in the global economy. The government should reduce inequality by empowering vulnerable workers and redistributing income, to promote consumption and aggregate demand. It also needs to be active in fiscal spending for youngsters to increase the low birth rate. Moreover, it should increase public investment for future industries by implementing an effective industrial policy. Of course, it would be not easy to transform the growth model rapidly given the important role of the exports of semiconductors and automobiles in the Korean economy. However, it is crucial to reduce excessive dependence on exports from those sectors and promote a more balanced growth with the increasing role of domestic demand and the service sector.

While the income-led growth strategy in the former Moon government was not entirely successful, Koreans should not abandon the effort to change the growth model but need to learn valuable lessons from the experience of income-led growth. Above all, the mobilization and organization of political efforts to shift power relationships and change conservative public opinion regarding fiscal expansion are crucial for its success. Finally, international cooperation to recalibrate the growth model of emerging market countries is necessary because the efforts of individual countries have limitations. The Korean experience offers important implications for other countries in this regard.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Although exports to China were not primarily driven by low wages in general, the decline in the labor share could have contributed to the increase in exports to foreign countries. This was especially true for small and medium-sized companies that were subcontractors of large exports firms.

2 Ahn (Citation2005) reports that exports contributed to the productivity growth, using the plant-level data in Korea. He emphasized the role of the spillover effect of learning-by-exporting. It should be noted that recent empirical studies report that the role of export is crucial to productivity growth and economic growth, though former studies had difficulty in showing the growth effect of trade (Feyrer Citation2019).

3 Even mainstream macroeconomics recognizes the negative impact of inequality on sustainable growth through various channels, including education and social conflicts (Berg et al. Citation2018).

4 The growth of the budget in health, welfare and labor rose by 12.9% in 2018 and 12.2% in 2019.

5 In fact, the number of jobs created in 2019, following two consecutive years of rapid minimum wage hikes, increased largely, and was almost same to that of 2017.

6 In 2017, Samsung Electronics accounted for the largest share in equipment investment, representing a quarter of it in Korea. The company significantly increased equipment investment from 25.5 trillion won in 2016 to 43.4 trillion won in 2017, a 70.2% increase, driven by a 106.8% surge in semiconductor investment from 13.2 trillion to 27.3 trillion won. However, in 2018, Samsung Electronics reduced its investment in semiconductor production and display production by 13% and 79%, respectively, resulting in a 32% decrease in its total equipment investment, alongside the coming changes in the global market. The company further reduced its equipment investment by 9% in 2019.

7 The direction of economic policy in 2019, announced by the Korean government in December 2018, prioritized stimulating economic dynamism and did not place significant importance on income-led growth (The Korean Government Citation2018). For example, the government emphasized the promotion of corporate investment through regulatory reform.

8 According to the Bank of Korea, the ratio of household debt to GDP in Korea was already as high as 97.6% in 2019 and increased to 108.3% in 2021.

9 International trade in goods as a share of global GDP had already slowed down following the global financial crisis, but service trade, international capital flows, and migration continued to grow (Goldberg and Reed Citation2023). Furthermore, imports of intermediate and final manufactured goods have continued to grow faster than domestic manufacturing output, even though the US has been importing more from South East Asian countries such as Vietnam and less from China in recent times (Walker Citation2022).

10 This is also in line with modern and progressive supply-side economics and the recent revival of industrial policy (Juhasz, Lane, and Rodrik Citation2023).

References

- Abiad, A., D. Furceri, and P. Topalova. 2016. “The Macroeconomic Effects of Public Investment: Evidence from Advanced Economies.” Journal of Macroeconomics 50: 224–240.

- Ahn, S. 2005. “Does Exporting Raise Productivity? Evidence from Korean Microdata.” ADB Institute Research Paper Series, No. 67.

- Aiyar, S., A. Ilyina, J. Chen, A. Kangur, J. Trevino, C. Ebeke, T. Gudmundsson, et al. 2023. “Geoeconomic Fragmentation and the Future of Multilateralism.” Staff Discussion Notes 2023 (001): 1. doi: 10.5089/9798400229046.006.

- Berg, A., J. D. Ostry, C. G. Tsangarides, and Y. Yakhshilikov. 2018. “Redistribution, Inequality, and Growth: New Evidence.” Journal of Economic Growth 23 (3): 259–305. doi: 10.1007/s10887-017-9150-2.

- Blanchard, O. 2019. “Public Debt and Low Interest Rate.” American Economic Review 109 (4): 1197–1229. doi: 10.1257/aer.109.4.1197.

- Cerra, V., A. Fatas, and S. C. Saxena. 2020. “Hysteresis and Business Cycles.” IMF Working Paper, WP/20/73.

- Cho, E. 2023. “An Analysis of Export Stagnation to China and Diversification of Export Markets.” Trade Focus. No. 7. Institute for International Trade. (Korean)

- Crotty, J., and K.-K. Lee. 2002. “A Political-Economic Analysis of the Failure of Neo-Liberal Restructuring in Post-Crisis Korea.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 26 (5): 667–678. doi: 10.1093/cje/26.5.667.

- Crotty, J., and K.-K. Lee. 2009. “Was the IMF-Imposed Economic Regime Change in Korea in the Wake of the 1997 Crisis Justified?: The Political Economy of the IMF Intervention.” Review of Radical Political Economics 41 (2): 149–169. doi: 10.1177/0486613409331422.

- Feyrer, J. 2019. “Trade and Income: Exploiting Time Series in Geography.” American Economic Journal 11 (4): 1–35. doi: 10.1257/app.20170616.

- Furman, J. 2016. “The New View of Fiscal Policy and Its Application.” Conference: Global Implications of Europe’s Redesign.

- G20. 2017. “Fostering Inclusive Growth. G-20 Leaders’ Summit, July 7–8.” Prepared by Staff of the International Monetary Fund.

- Garcia-Herrero, A. 2022. “Slowbalization in the Context of US-China Decoupling.” Intereconomics 57 (6): 352–358. doi: 10.1007/s10272-022-1086-x.

- Goldberg, P., and T. Reed. 2023. “Is the Global Economy Deglobalizing? And if So, Why? And What is Next?” NBER Working Paper 31115.

- IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2020. “Ch 2. Public Investment for the Recovery.” Fiscal Monitor, October 2020: Policies for the Recovery.

- IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2021. “Fiscal Monitor Database of Country Fiscal Measures in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic.”

- Joo, S., K.-K. Lee, W. J. Nah, S. M. Jeon, and J. Dong-Hee. 2020. “The Income-Led Growth in Korea: Status, Prospects and the Lessons for Other Countries.” Korea Institute for International Economic Policy Research Paper, Policy Analysis 20–01.

- Juhasz, R., N. J. Lane, and D. Rodrik. 2023. “The New Economics of Industrial Policy.” NBER Working Paper 31538.

- Lavoie, M. and Stockhammer, E. 2013. eds., Wage-Led Growth: An Equitable Strategy for Economic Recovery. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lee, K.-K. 2018. “Income-Led Growth: Theory, Empirics and Debates in Korea.” Fiscal Study 10 (4): 1–43. (Korean)

- Lee, K.-K. 2012. “The Political Economy of Global Imbalances and the Global Financial Crisis.” In Crises of Global Economies and the Future of Capitalism: Reviving Marxian Crisis Theory, edited by K. Yagi, N. Yokokawa, S. Hagiwara, and G. Dymski.

- Nicita, A., and C. Razo. 2021. “China: The Rise of a Trade Titan.” UNCTAD.

- Onaran, Ö., and G. Galanis. 2014. “Income Distribution and Growth: A Global Model.” Environment and Planning A 46 (10): 2489–2513.

- Palley, T. I. 2012. “The Rise and Fall of Export-Led Growth.” Investigaction Economica 71: 280.

- Statistics Korea. 2022. “The Results of the Survey of Household Finances and Living Conditions in 2022.” (Korean)

- Subramanian, A., M. Kessler, and E. Properzl. 2023. “Trade Hyperglobalization is Dead. Long Live…?” Peterson Institute of International Economics Working Paper, 23–11.

- Sullivan, J. 2023. The Biden Administration’s International Economic Agenda. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

- The Committee of Income-Led Growth. 2018. “Shared Prosperity in Korea and Understanding Income-Led Growth in Korea Correctly.” (Korean)

- The Korean Government. 2018. “The Direction of Economic Policy in 2019.” (Korean)

- Walker, R. 2022. Strengthening Supply Chain Resilience: Reshoring, Diversification, and Inventory Overstocking. US Economics Analyst. Goldman Sachs.

- Yang, P. 2020. “The Cause of a Fall in Exports to China and Tasks.” World Economy Today 20 (19) Korea Institute for International Economic Policy. (Korean)