Abstract

Throughout its proceedings and in its Final Report, the Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability gave considerable prominence to supported decision-making as a means for achieving the human rights of people with disabilities. It sought input on supported decision-making from people with lived experience, roundtables, public hearings, and commissioned independent research on supported decision-making and proposals for reform. Practical challenges raised at the roundtables and by witnesses included the resources needed for education, training, and capacity building, and the challenge of finding supporters for people who were isolated. Evidence was given that legal reform was only one aspect of what was needed to embed supported decision-making into sectors and services to improve the lives of people with cognitive disabilities. The Commission’s Final Report endorsed a set of national supported decision-making principles, with many of these principles underpinned by the evidence received and commissioned research. However, overall, the Commission’s recommendations were overly focused on reform of guardianship and administration systems, and implementation guidance was lacking. The Commission also missed an opportunity to recommend legislative and practice reform beyond guardianship systems, into multiple services and sectors including the National Disability Insurance Scheme, the health system, and the public sector more widely.

The Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability (the Commission) gave considerable prominence to supported decision-making as a mechanism for achieving the rights of people with disabilities and protecting against violence, abuse, neglect, and exploitation. The Commission heard evidence from different sources about the significance of supported decision-making to the diverse groups that make up people with cognitive disabilities. Nevertheless, much of the evidence focussed on people with intellectual disabilities. Most of the Commission’s recommendations about supported decision-making concentrate on legal frameworks, setting out a blueprint for change to guardianship and administration systems based on principles of supported decision-making (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.6, Ch. 2, Rec. 6.4–6.10). While two recommendations concern adding supported decision-making to practice standards in the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.10, Ch. 3, Rec. 10.6–10.7) the Commission gave scant attention to implementing supported decision-making in other service systems and contexts relevant to the day-to-day lives of people with intellectual disabilities. This was despite receiving evidence that more was needed than reforming formal spheres of decision-making, with legal reform being insufficient for the cultural change necessary to embed supported decision-making across the multiple systems encountered by people with cognitive disabilities.

In this article we review how the Commission considered, sought evidence on, and made recommendations about supported decision-making, and we critically appraise its stance and recommendations. Supported decision-making is relevant to all people with cognitive disabilities, but in reviewing the evidence and recommendations, where possible we draw out the issues pertinent to those with intellectual disabilities.

Background

The Commission had a broad mandate to examine violence against, and abuse, neglect and exploitation of people with disabilities in Australia across all sectors and contexts. A key feature of its approach was recognition of the human rights of people with disabilities (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Executive Summary, p.11; Vol. 2, p. 1). The Commission’s strong focus on supported decision-making throughout its enquiry and in the Final Report demonstrates its belief in the significance of this practice in furthering the rights of people with disabilities and as a means to “respect [their]… inherent dignity, individual autonomy including freedom to makes one’s own choices” (United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [UNCRPD], Citation2006, Article 3).

The starting point for understanding supported decision-making is Article 12 of the UNCRPD, which asserts the rights of all people with disabilities to make decisions about their own lives and access the support needed to do this. In the context of the Commission’s focus on violence, abuse, neglect, and exploitation, Spivakovsky et al. (Citation2023) explained how supported decision-making is fundamental to avoiding such harms for people with disabilities, suggesting that one interpretation of Article 12 is that it:

…mandates supported decision-making in preference to substituted decision-making, and simultaneously emphasises meaningful choice and equal protection from violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation. As Piers Gooding suggests, this implies a need for a shift away from a framing that is concerned with protection from risk, towards choice, information and equal protection from violence and abuse. (pp. 53–54)

…its understanding that the Convention allows for fully supported or substituted decision-making arrangements, which provide for decisions to be made on behalf of a person, only where such arrangements are necessary, as a last resort and subject to safeguards. (United Nations, Citation2008, p. 3)

The Australian Law Reform Commission, the United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the Australian Human Rights Commission have all recommended that Australia review this interpretation with a view to withdrawing the declaration (McCallum, Citation2020).

The Commission’s focus on supported decision-making

The Commission’s terms of reference open by recognising the human rights of all people (including those with disabilities) and the right to “respect for their inherent dignity and individual autonomy” (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, p. 94). While many other parts of the Commission’s terms of reference could implicitly require considering how supported decision-making could be used to achieve their aims, there are perhaps a few specific directions from the Commonwealth Parliament that are worth identifying.

First, the Commission was required to inquire into: “…(c) what should be done to promote a more inclusive society that supports the independence of people with disability and their right to live free from violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation…” (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, p. 95). Second, the Commission was directed to have regard to: “…(h) the critical role families, carers, advocates, the workforce and others play in providing care and support to people with disability…” (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, p. 96). Third, the Commission was also directed to consider: “…(i) examples of best practice and innovative models of preventing, reporting, investigating or responding to violence against, and abuse, neglect or exploitation of, people with disability” (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, p. 96).

The Commission clearly interpreted these parts of the terms of reference to allow for direct engagement with the concept of supported decision-making, current practice, and evidence about best practice. The relative importance given to this topic is apparent in the evidence that it sought from a broad range of stakeholders – particularly those with lived experience – through a dedicated hearing (Hearing 30) (CoA, Citation2019–2023 [Hearing 30, transcripts, Nov. 21–25, 2022]), the publication of a background paper (CoA, Citation2022, May 16), hosting of two roundtables (May 31–Jun. 1, 2022), a summary report on the roundtables (CoA, Oct., Citation2022), and commissioning independent research (Bigby et al., Citation2023). Supported decision-making also featured prominently in the Commission’s recommendations and Final Report, with a dedicated chapter in Volume 6 (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol. 6, Ch. 2) and references throughout other volumes, particularly Volume 10 (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.10).

Commission processes modelled inclusion of people with disabilities, aiming to maximise their participation. Some examples were: using a trauma-informed approach and involving professionals such as social workers and counsellors in much of the public engagement, seeking amendments to the Royal Commissions Act 1902 (Cth) to allow for private sessions to ensure confidentiality and ensure lay witnesses were paid an equal amount as expert witnesses, and for those attending a private session, “the opportunity to nominate a support person to accompany them” (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.2, p.25). In addition, advocacy support services were funded and available to people with a disability “who had difficulty communicating or understanding how to engage with us” to assist their participation through submission, public hearings, or private sessions (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.2, p.25). The success of these measures was evident from the participation of people with mild intellectual disabilities in Hearing 30 – dedicated to autonomy and supported decision-making – and the inclusion of testimony relating to experiences of people with more severe intellectual disabilities who were represented by family members or others who knew them well (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.1).

Evidence on supported decision-making

The Commission directly sought information and collected evidence that informed their recommendations on supported decision-making. A summary of this material is discussed in this section.

Roundtables

The Commission convened two roundtables, one on supported decision-making and another on guardianship on 31 May and 1 June 2022. Prior to these meetings the Commission published a Background Paper with proposals for reform (CoA, Citation2022, May 16). The focus here is on those parts of the Background Paper and the roundtable Summary Report (CoA, Citation2022, Oct.), which dealt with supported decision-making. The Background Paper identified national and international developments on legal reform, contemporary understandings of supported decision-making, and pilot programs trialling supported decision-making practices. It identified two themes from information already gathered by the Commission: barriers to people with disabilities participating in making their own decisions, and a “need for greater understanding and access to supported decision-making” (CoA, Citation2022, May 16, p. 6) The Background Paper proposed a “National supported decision-making framework” to:

Increase consistency across jurisdictions,

Enable the implementation of a national safeguarding framework prioritising will preference and rights (consistent with the need to decrease the risk of violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation),

Encourage the greater use of supported decision-making by “tribunals, courts, health professionals, other institutions, and the broader community,”

Apply to guardianship and administration, NDIS, health care, supported accommodation and the criminal justice system. (CoA, Citation2022, May 16, p. 12)

The following eight principles were proposed with a series of questions for discussion at the roundtable:

Recognition of the equal right to make decisions,

Presumption of decision-making ability,

Respect for dignity and the right to dignity of risk,

Recognition of the role of informal supporters and advocates,

Access to support necessary to communicate and participate in decisions,

Decisions directed by a person’s own will, preferences and rights,

Inclusion of appropriate and effective safeguards against violence, abuse, neglect or exploitation, and

Co-design, co-production and peer-lead design processes.

In addition, the paper proposed a number of “guidelines” to assist with the implementation of the principles. These related to support; will, preferences, and rights; safeguards; decision-making ability; recognition of informal supporters and advocates; and respect for the right to dignity of risk (CoA, Citation2022, May 16, pp. 15–23).

Evident in these proposals were suggestions for mechanisms that could be enshrined in law and the need to embed supported decision-making into existing guardianship systems to ensure use of supported decision-making approaches prior to any substitute decision-making and reforms to allow legally recognised supporters. While the existence of Australia’s interpretative declaration on Article 12 was mentioned, no proposal relating to it was put forward in the Background Paper. Education, training, and capacity building were flagged as areas where implementation of the proposed supported decision-making framework would require government attention as was the potential need for oversight governance of the framework (CoA, Citation2022, May 16, pp. 31–34).

The roundtable was attended by Commissioners and the Chair and by 40 invited stakeholders, which included people with disabilities, representative organisations, government and non-government organisations, regulators, lawyers, academics, advocacy groups, and policy experts (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.2, p.76).

A Summary Report of the roundtable proceedings was published in October 2022. The Summary Report interestingly restated that the purpose of the roundtables was to consider implementation of supported decision-making (i.e., “how a national policy and legislative framework for supported decision-making can be implemented”… “how the proposals could be implemented in practice”… “any barriers to implementation” (CoA, Citation2022, Oct., p. 1). It noted that participants “largely supported” the principles proposed by the Commission in its Background Paper and summarised the key themes to emerge from the roundtable, including:

the importance of co-design,

the need to recognise the “many different audiences for the framework” – i.e., legislatures, professionals, government officials, those working in the disability sector,

the need to recognise the diversity of people with a disability and their unequal access to decision support,

recognition that, in practice, decision-making occurs on a continuum, and

the current lack of understanding in the broader community about the right of people with disability to make decisions affecting their lives. (CoA, Citation2022, Oct., pp. 3–4)

Particular debate among participants was noted in relation to the proposed principle to recognise informal supporters. Some participants raised concerns about informal support amounting to substitute decision-making in practice, which could lead to exploitation or neglect, with some suggesting that informal supporters should be regulated. Others considered that there were risks of overregulation and no clear definition of what constitutes an “informal supporter.” Another area of debate was around inclusion of the term “rights” alongside “will and preferences” in proposed principle 6. Some participants saw “rights” as important, emphasising for example, cultural rights to be taken into account for First Nations peoples. Others suggested the term was unnecessary in that context and introduced the possibility of conflict – either between competing rights or between a person’s “will” and their “rights” (CoA, Citation2022, Oct., pp. 5–7).

The Summary Report noted that while legal reform was necessary for implementation of a supported decision-making model, it “alone was not considered enough to change culture and practice towards supported decision-making” (CoA, Citation2022, Oct., pp. 8–9). In doing this, the report recognised the very practical elements associated with implementing supported decision-making; such as its “resource-intensiveness” and the need for investment to achieve a “cultural shift” (CoA, Citation2022, Oct., pp. 8–9). Participants were noted as reinforcing the need for education and training or capacity building for those involved, including the supported person, those acting as supporters or representatives and others (i.e., employees and contractors) who engage with them.

Another recurring theme in the roundtable was the lack of access to supporters experienced by some people (e.g., those in rural and remote areas, whose first language is not English, and those who have no family member or friend who is ready and willing to act as a supporter) (CoA, Citation2022, Oct., p. 13). The practical realities of supported decision-making, including the time, effort, and emotional investment it takes, was also recognised. It was accepted that supported decision-making should be incorporated into current guardianship frameworks – meaning that all guardians should be expected to facilitate supported decision-making. However, in relation to the work of the Public Guardians, some considered that they were “insufficiently funded and resourced to work with people to build their capacity and foster supported decision-making” (CoA, Citation2022, Oct., pp. 15, 17). Further implementation challenges at the interface of guardianship systems included the low tolerance for risk of harm (to a supported person), and current drivers for the appointment of guardians due to various decisions necessary in the context of National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), aged care service provision and social security issues (CoA, Citation2022, Oct., p. 24).

Public hearings

Hearing 30, held in November 2022, was devoted to “Guardianship, substituted and supported decision-making.” Some of the listed purposes of that hearing included to:

consider why models of supported decision-making are not more widely used as an alternative to substituted decision-making, and

examine supported decision-making models for people with disability. (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, p. 141)

Supported decision-making also featured in other public hearings, including Hearings 14, 20, and 32. Hearing transcripts revealed many issues, some that were similar to those discussed at the roundtables, which were identified by people with lived experience, advocates, service providers, and government officials.

Testimonies illustrated the diversity of people for whom supported decision-making was important, such as people with dementia, psychosocial disabilities, chronic illness. Examples of such testimonies were provided by witnesses Ms. Bury and Mr. Gear (CoA, 2019–2023 [Hearing 30, transcripts, Nov. 22 & 25, 2022]). However, issues for people with intellectual disabilities dominated Hearing 30, with at least four self-advocates with intellectual disabilities, and several representatives from advocacy and legal centres specialising in working with this group included among the witnesses. On Day 1, Counsel Assisting drew attention to data suggesting that people with intellectual disabilities were 3.2 times more likely than other people with disabilities to need assistance with decision-making, but made the point that needing assistance should not be conflated with being without capacity (CoA, 2019–2023 [Hearing 30, transcript, Nov. 21, 2022, p.11]).

People with intellectual disabilities spoke in Hearing 30 about the importance to them of supported decision-making and how good support also helped to build people’s own decision-making skills and confidence. For example, Mr. Kremer from the Council on Intellectual Disability, said,

Decision-making is a human right. Human rights means that everyone in the world has value… It means to have control over my own decisions, with or without support and adjustments. We need investment within people with disability, less guardianship and more supports. With the right support, there would be much less need for guardianship. People will gain confidence to do it themselves. And if they can’t do it themselves, they should still get support with decisions. (CoA, 2019–2023 [Hearing 30, transcript, Nov. 24, 2022, p. 389])

The significance of being involved in day-to-day decision-making was highlighted by Mr. Elliot, when he described what good decision support looked like:

Support people’s ability. Believe their decision-making capability can be grown and developed over time. For example, letting them make small decisions and building it up. Letting them do small bits of work and be a part of decisions around the house. Helping them feel equal. (CoA, 2019–2023 [Hearing 30, transcript, Nov. 24, 2022, p. 389])

So, it takes time. You have to talk to her at the right time….and we had to have face to face meetings…for that relationship to develop, for that trust to develop. And over that time, we were able to talk to her about some of the individual choices that she made and that - and the values that were important to her as an individual, that might or might not be the same values that that advocate holds. (CoA, 2019–2023 [Hearing 30, transcript, Nov. 22, 2022, pp.176–77])

Supporters, to support a person to make their own decision, need to have skills and need to be trained and it is an investment in time. It doesn’t happen necessarily quickly. [Anne Gale, Public Advocate and Acting Principal Community Visitor, South Australia]. (CoA, 2019–2023 [Hearing 14, transcript, Jun. 9, 2021, p.226])

… for lots of people, the staff in their life are really important relationships for them as well, so equipping those staff, empowering those staff, enabling those staff closest to people to know that their job is actually more than care. Of course, they have got to meet the care needs but it’s more than that, it’s really helping the person on their journey in life. (CoA, 2019–2023 [Claire Robbs, Life without borders, Hearing 30, transcript, Dec. 14, 2022, p. 567])

Limited evidence was received about capacity building or the impact and effectiveness of training for supporters. An exception to this was the evidence of the Queensland Public Trustee whose office acts as a formally appointed substitute decision-maker for financial decisions (i.e., administrator) for its clients, many of whom have intellectual disabilities. The Public Trustee informed the Commission that his office had adopted training based on the La Trobe model of supported decision-making and reported on changes in practice and workforce culture resulting from a suite of rights-based initiatives that had included this training:

…Our Ombudsman complaints have gone down by 40 per cent. The number of complaints requiring remedial action have reduced from 31 per cent to 6 per cent…. We have established also a customer reference group where key advocacy groups represent the voices of customers, and their general feedback is they are noticing significant cultural changes at the Public Trustee. (CoA, 2019–2023 [Hearing 30, transcript, Nov. 22, 2022, p. 213])

I think it’s not sufficient just to reform guardianship laws. We are talking about a much broader change that’s required in society as a whole … [supported decision-making] also needs to be seen in the context of reform of other decision-making laws such as mental health laws…So, we need to see a range of acts change, and sitting alongside of that we need reforms in the service system, so supported decision-making models, and we need to see much broader inclusion and definitely changes in the ableism attitudes. (CoA, 2019–2023 [Hearing 30, transcript, Nov. 24, 2022, p.355])

Evidence at the hearing illustrated the importance of co-design and co-leadership by people with intellectual disabilities, as raised by the background paper and at the roundtable. Witnesses gave concrete examples of this in practice:

An example of leadership by people with lived experience is the peer mentor group I led. We talk about things like moving out, getting a pet, practising making decisions, what makes it easier and how it can be hard to speak up…Another example is the workshops I run for people with disability about the supported decision-making…We have gone…from having people facilitate workshops with us to us becoming the facilitators. I have gained the skills and confidence to do that and take a leading role. (CoA, 2019–2023 [Mr. Kremer, Hearing 30, transcript, Nov. 24, 2022, p. 384])

…let’s say their parent was an informal supportive decision maker and their parent has suddenly passed away, nobody has thought to develop those relationships so that when the time comes somebody else can step in…We need, as a community, to be thinking about it before it gets to that point…We need to be making sure that people who need the support to make decisions are developing the supportive mechanisms to do so. So that potentially you don’t even need to end up at VCAT because it works on an informal basis in the first place. (CoA, 2019–2023 [Ms. Anderson, Hearing 30, transcript, Nov. 23, 2022, p. 299])

Commissioned research

The Commission engaged a team of interdisciplinary scholars (both authors were part of this team). Their brief was to identify the significance of supported decision-making to the lives of people with cognitive disabilities, identify essential elements of a supported decision-making framework and locate key implementation issues. The researchers reviewed the international literature on good practice and strategies for implementing supported decision-making, and conducted an empirical exploration of these issues through an online survey, interviews and focus groups with a range of stakeholders and engagement with an advisory forum. The report, titled “Diversity, dignity, equity and best practice: A framework for supported decision-making” (Research Report) was released by the Commission in January 2023 (Bigby et al., Citation2023).

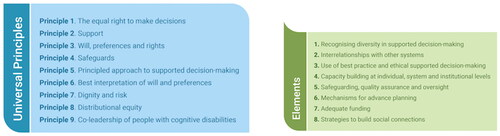

Finalised well before Hearings 30 and 32, the Research Report proposed a framework for supported decision-making, which included a set of eight elements that captured conceptually, many of the pressing issues raised during these and other hearings (see ). As well as these eight elements, the Research Report proposed nine universal principles of supported decision-making, adopting a principled approach to supported decision-making (see ), and made detailed recommendations about implementing the framework (Bigby et al., Citation2023).

Figure 1. Proposed elements and principles of supported decision-making (Bigby et al., Citation2023).

The Commission’s conclusions and recommendations on supported decision-making

In recognising the well-established link between human rights and the right to participate in decision-making, the Commission concluded that supported decision-making “is key to enabling the autonomy of people with disability” (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.6, Ch.2, p.115). The Commission’s conclusions and recommendations about supported decision-making are mostly in Volume 6 of the Final Report and focus on legal reform, with a smaller section in Volume 10 concerned with supported decision-making in the NDIS. Importantly too, the proposed Disability Rights Act would enshrine in Australian law the right of people with disability to access and use support for decision-making (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Rec. 4.6).

Adopting a principled approach to supported decision-making

The Commission recognised that in Australia there is no uniform definition of what is meant by supported decision-making (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.6, p.122). Having multiple understandings of this term can lead to confusion; using the same term to mean different things can lead to people thinking they are striving to a common goal, only to later realise that they were trying to achieve different results. The main ways in which supported decision-making is understood are, as an approach that recognises that all forms of decision-making sit along a continuum (principled approach); or a binary model, where supported decision-making and substituted decision-making are mutually exclusive.

The Commission adopted the “principled approach to supported decision-making,” which was suggested in the Research Report. The key aspect of the principled approach is ensuring that an individual’s stated or perceived “will and preferences” are at the centre of decision-making. The principled approach accommodates those with severe and profound intellectual disabilities and accepts that some, but not all, forms of substitute decisions can be considered part of supported decision-making. When substitute decisions are based on a “will and preference” approach rather than best interests, they fall within a principled approach to supported decision-making.

In adopting a principled approach, the Commission rejected the binary model that underpins most early legal models, whereby if a capacity threshold cannot be met (even with support) then a person can have substitute decisions made for them, not necessarily based on their will and preferences. Capacity has acted as the tipping point between when support ends and substitution can occur. However, that binary legal model means that those with severe cognitive impairments, who will never satisfy a test of decision-making capacity regardless of levels of support received, are excluded from supported decision-making.

Unfortunately, the glossary definition of supported decision-making was at odds with the Commission’s acceptance of the principled approach and its rejection of the “binary approach.” Notably the glossary states: “Supported decision-making does not mean making a decision for or on behalf of another person” (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.6, p.7), thereby implying that supported decision-making and substitute decision-making are mutually exclusive. This could, understandably, lead some readers to assume a binary approach was being adopted and lead to some confusion.

Legal frameworks for supported decision-making

The Commission concluded that current guardianship and administration systems that implement substituted decision-making can significantly limit the autonomy of people with disabilities and be done against their wishes. It recognised that current systems did not embed or practise supported decision-making, with the result that substitute decision-making appointments were often not a “last resort” (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.6, Ch.2, p.159). The Commission made 16 recommendations in Volume 6, Chapter 2, devoted to supported decision-making (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.6, Ch.2.). These focussed particularly on aligning, updating, and improving current substitute decision-making frameworks (i.e., State and Territory legal guardianship and administration regimes) to be more consistent with the UNCRPD. Half of these 16 recommendations were to reform guardianship laws, two were concerned with the development of guidelines and standards to guide public bodies (such as Tribunals, Public Advocates, Public Trustees, and Public Guardians) and a further three recommendations focused on the particular issues facing financial decision-making and the role of the State and Territory Public Trustees.

The Commission’s recommendations included legislating a set of 10 national supported decision-making principles. These restated the eight principles initially proposed in the background paper and added two more, on cultural safety and diversity (discussed further below). However, proposals in the Background Paper to introduce guidelines for various aspects of the principles were not mentioned in the Final Report.

The Commission, like law reform agencies before it (Then et al., Citation2018) recommended establishing legally recognised supporters, with the option of “representatives” (substitute decision-makers) who may be appointed as a last resort (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.6, pp.181–188). Four of the Commissioners supported a recommendation to the Australian Government to remove the interpretive declaration on Article 12 of the UNCRPD (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Rec. 6.20).

Supported decision-making in disability services

The Commission’s conclusions and recommendations about the role of supported decision-making in the NDIS are found in Volume 10 of the Final Report. The release, in May 2023, of the NDIS policy on supported decision-making and an implementation plan are noted, together with a government submission that the policy was expected to reduce the need of NDIS participants for substitute decision-making. In its rationale for the recommendations, the Commission refers to a report authored by Gerard Quinn, the United Nations Special Rapporteur for Disability (Quinn, Citation2023), which recommends that governments, “develop protocols on supported decision-making in the specific context of support services” (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.10, p.86). The Commission also commented on evidence it had heard that supporting the exercise of choice and decisions about everyday life was a component of “Active Support,” a best-practice framework used to support people with intellectual disability living in group homes (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.10, p.106).

Reflecting these comments and much of the evidence heard, the Commission asserted that it saw “supported decision-making” broadly to include daily decision-making support” (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.10). It stated,

Although independent advocates can and do support people with disability to make decisions about services and supports, once a service provider is engaged, disability support workers also have an important role in supporting individual decision-making about day-to-day matters and arrangements for the delivery of disability services. In this way, service providers fulfil their obligation to enable the NDIS participants they support to exercise informed choice and control. However, service providers and support workers need to be aware of the risks of exercising undue influence on the people with disability they support. (p. 105)

That the Commission’s views expressed above appeared to challenge the NDIS policy perspective, “that it is not the role of disability service providers to make decisions on behalf of people with disability” (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.10, p.170) was not discussed. The Commission made two recommendations for action by the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission specifically about supported decision-making in NDIS funded services: first, to amend Practice Standards, to reflect the rights of participants to support with everyday decisions and to develop decision-making skills; and second, to co-design a practical guide on supported decision-making for service providers (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Rec. 10.6. 10.7).

Critiquing the Commission’s recommendations about supported decision-making

We note at the outset that, as described above, the Commission went to great lengths to obtain evidence on supported decision-making from multiple sources. Managing the multiple inflows of different strands of evidence was no doubt complex and the process and level of detail given to this topic was noticeably greater than some other topics within its scope. For example, the Background Paper on supported decision-making was much more detailed than that prepared for group homes, and the Commission invested in hearings, roundtables, and independent research. However, it was unfortunate that the Commission’s timetabling precluded a more logical flow and use of information and evidence. For example, the framework and principles for supported decision-making proposed in the Background Paper preceded the work on a framework commissioned from the academic team with theoretical and empirical research expertise in supported decision-making, which meant there was no external discussion of that work to inform the Commission’s views.

Advantages of a principled approach

We consider the Commission’s decision to adopt a principled approach to decision-making to be a step in the right direction. There are several reasons for this: it reflects the messy reality of much everyday decision support, is more inclusive of people with more severe intellectual disabilities, is in line with reforms already underway, and includes some guidance for supporters around issues of dignity and risk.

Reflecting the everyday reality of support for decision-making

Some will argue that due to the injustices that have occurred under the guise of “best interests substitute decision-making,” there are dangers in subsuming any form of substitute decision-making within the term supported decision-making. It has been suggested that this may increase the risk that, instead of supporting a person to make their own decision, “will and preference” substituted decision-making becomes the supported decision-making “default” (Chesterman, Citation2024). However, we would suggest that the binary model – where things are simplified into substitute decision-making being “bad” and supported decision-making as “good” is unhelpful in real life. The principled approach is not only more inclusive of those with more severe cognitive disabilities (including intellectual disabilities) but also reflects the somewhat messy reality of many who are supporters of this group who may move between supporting a person to make their own decision and making a substitute decision on behalf of the person, reflecting an interpretation of their will and preferences, depending on the decision, context, level of the person’s understanding, and levels of risk (Then et al., Citation2022).

Aligned with current directions of legal reform

While the vast majority of legal reform initiatives in Australia and internationally have recommended changes to existing systems to incorporate aspects of supported decision-making, a key hallmark of reforms in Australia to date has been to improve existing substitute decision-making schemes and incorporate supported decision-making as an adjunct to substitute decision-making (Then et al., Citation2018; Then et al., Citation2024). However, there is evidence that recent legal reform aligns with a principled approach to supported decision-making. This is done by, mandating that supported decision-making be attempted prior to any substitute decision-making occurring; and where a substitute decision-maker is authorised to make decisions on behalf of someone, the principles they must apply in coming to a decision are aligned substantively with a “will and preference” approach instead of a “best interests” approach.Footnote2 Perhaps the clearest indication of the principled approach being adopted has been in Tasmania where the justification for these improvements to guardianship legislation is attributed to the work of the Commission and the principled approach outlined in the Research Report (Parliament of Tasmania, Citation2023).

The Commission’s recommendations sought to move away from the term “capacity” to decision-making ability (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.6, Ch.2, pp.162, 166, Rec. 6.4, 6.6–6.7, 6.9–6.10) and, in accordance with the recommended supported decision-making principles (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Rec. 6.6), that consideration should be given on whether support has been provided, prior to any rebuttal of the presumption of decision-making ability (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.6, Ch.2, pp.162, 166, 177–179, Rec. 6.6, 6.7). If implemented, this will mean that Australian laws more closely reflect the principled approach, which seeks to improve decision-making support regardless of who has the legal decision-making authority, and remove a “capacity” threshold that is either met or not by an individual and that draws a bright line between who has decision-making authority with regard to particular decisions.

Guidance about dignity of risk

The principled approach also provides some guidance for supporters about the implementation of the principle of dignity and dignity of risk, included as principle 3 of the Commission’s 10 recommended principles. It acknowledges that “risk of harm” from decision-making remains a real issue and a significant problem in practice, and that it must be addressed head on. It notes that substitute decision-making where a person’s will and preferences are overridden is permitted exceptionally when necessary to “prevent serious harm.” Only in these circumstances can a substitute decision be made guided by the “standard of promoting ‘personal and social wellbeing’” (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.6, Ch.2, pp.123, 190–192).

Nevertheless, the Commission could have more clearly articulated the threshold level of harm to be met to make a substitute decision especially given its exceptional nature. The Research Report for example, suggested that it might be reached where a “person’s stated or inferred will and preferences involves risk of serious, imminent physical or financial harm with lasting consequences to themselves (including incurring civil or criminal liability) and that person is not able to understand that risk even with support” (Bigby et al., Citation2023, p. 27). Although a similar statement was left out of the Commission’s recommendation, it did make clear the “very limited circumstances” in which this exception may apply and that it only applies where “necessary to prevent serious harm” (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.6, Ch.2, p.121).

Concentration on legal reform of guardianship and administration

There was a strong focus on formal structures and laws in the Commission’s examination of supported decision-making. Recommendations in Chapter 2 of Volume 6 situate supported decision-making as a potential legal mechanism that can be implemented to realise the rights of a person with disabilities. It concentrated on the deficiencies of current guardianship systems, detailing information about current usage, rates of substitute decision-making, guardianship tribunal processes and past efforts of legal reform in those areas. Considerable attention was also given to financial substitute decision-making and the current roles of public guardians, advocates and trustees, and the need for financial literacy amongst people who may be subject to administration orders.

The Commission had a wider remit to make recommendations about any “policy, legislative, administrative or structural reforms” than most reviews that have considered supported decision-making, namely the reviews by law reform commissions. To date, most in depth consideration of supported decision-making has been in the context of legal reform. Since 2010, five law reform agencies in Australia have looked at state-based substitute decision-making frameworks and the Australian Law Reform Commission examined decision-making at the Commonwealth level in its landmark 2014 report – Equality, Capacity and Disability in Commonwealth Laws (Australian Law Reform Commission, Citation2014) (ALRC Report). Unlike the Commission, most law reform agencies were limited to examining the suitability of and reform options around a single piece of legislation or linked pieces of legislation related to substitute decision-making (e.g., guardianship, administration, medical treatment decision-making). Therefore, until now, the focus on guardianship and associated legislation as the sole repository of how supported decision-making might be realised in law is somewhat understandable.

What differentiates the Commission’s work from prior work by law reform agencies is the much broader terms of reference and thus potential scope of recommendations. Therefore, it is somewhat disappointing that the Commission’s chapter on supported decision-making reads like a law reform agency report, with a focus on legal-like principles, guardianship systems, and legal reform. This was despite the evidence received during the Commission’s proceedings (see above), that changes to the law by itself were unlikely to change the lives of people with cognitive disability, and there needed to be more than simply a focus on guardianship legal frameworks. While the Commission acknowledged guardianship and administration as the focus of its recommendations, it recognised the need to look further beyond these and more holistically at other service systems and laws, stating,

…our recommendations have broader implications. We recognise there is a need for wide-ranging reform across different service systems, sectors and areas of law. Our recommendations are intended to be used as a model for further reform in all systems and areas of law that permit substitute decision-making. (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol. 6, Ch.2, p.118)

Later in Chapter 2, the Commission goes on to mention other specific areas of law in need of reform naming - “enduring powers of attorney and advance care directives, Centrelink and NDIS nominee arrangements and the laws on medical consent and mental health” (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.6, Ch.2, pp.222, 224).

The Commission heard the importance of looking further numerous times from witnesses and roundtable participants, and this was also a key finding of the commissioned research. The lack of specific recommendations on implementing supported decision-making in at least some of the service systems is disappointing, particularly so as looking further is only mentioned in the general statement contained in the Commission’s recommendation 6.6(b), which states:

The Australian Government and state and territory governments should also take steps to review and reform other laws concerning individual decision-making to give legislative effect to the supported decision-making principles.

Neglect of implementation of supported decision-making in service system contexts

As discussed in the previous section, by doing little to address the use of supported decision-making in the many other service systems people with intellectual disabilities encounter as part of their daily lives, the Commission missed the opportunity to direct governments, in more explicit terms, to consider these other systems which might equally benefit from embedding supported decision-making. Arguably, supported decision-making may have more impact on the rights of more people with disabilities through being embedded in other systems such as health care, aged care, justice and disability services, than through the guardianship and administration system that impacts a smaller minority.

The only substantive recommendations about supported decision-making in non-legal contexts aimed to strengthen NDIS supported decision-making policy through quality indicators of practice standards (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Rec. 10.6, 10.7). Interestingly, in its rationale for these recommendations, the Commission drew attention to the lack of detail about the “steps necessary to improve the practice of service providers in respect of daily supported decision-making” (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.10, p.107) in the NDIS policy and related implementation plan. However, it did not directly address what best practice for NDIS service providers looked like nor the tensions, identified in an earlier section, between the Commission’s and the NDIS’ view about the role of services in supporting day-to-day decision-making. More guidance for service providers from the Commission about the resolution of conflicting interests or avoidance of undue pressure would have been useful here in taking its recommendations relating to NDIS service providers forward.

The disproportionate focus on legal reform as the key “answer” to improving supported decision-making for people with disabilities meant the Commission missed opportunities for providing much needed guidance on how best to implement supported decision-making across different sectors. The Commission was also silent, on the application of the proposed set of national supported decision-making principles to practice in services and informal spheres, by paid and unpaid supporters and the real-world difficulties that would have to be grappled with, including for example:

How do the principles apply to people with profound intellectual disabilities who are not able to participate directly in decision-making no matter how skilled the supporter and whose preferences will have to be interpreted by supporters?

How to reconcile competing rights of people with disabilities – the right to be safe and the right to make decisions?

What is society’s tolerance for risk of different types of harm to a person with disability that may result from their right to make a decision?

What safeguards will be effective but do not remove the right of a person to make decisions?

How can the trustworthiness and neutrality of supporters be ensured?

Many parts of the Final Report commented on the need to better train all those who interact with people with disabilities - from justice workers to support workers - to better enable them to: adjust communication, improve attitudes and develop skills. Unfortunately, such ambitions were too often at a level of generality, that gave little guidance about content, strategies, costs, or effectiveness of training and whether supported decision-making skills would be included. Recommendations 6.13 and 6.14, which did specifically address education and capacity building for supported decision-making, were very short on detail about strategies, and allocated responsibilities for these tasks to already overburdened and underfunded Offices of Public Advocates or Public Guardians. Significant opportunities were missed to make more detailed recommendations about capacity building strategies that could be adopted by private enterprise including banks, the health system, and the public sector, and, so begin embedding understanding of supported decision-making in multiple systems and sectors.

The disappointingly minimalist approach to issues of implementation meant the Commission did not use the detailed understandings and recommendations developed by the research team that had been commissioned to look at these very issues. For example, in terms of capacity building tasks, the research had identified the need for a tailored and multi-level approach according to the positions that supporters occupied. In identifying the interrelationship of supported decision-making with other formal service systems and informal spheres of life, the research had considered the differing traditions of decision-making between sectors that would need to be tackled if supported decision-making were to be operationalised (Bigby et al., Citation2023, Ch. 4). The few references to this part of the commissioned research in the Final Report runs the risk that this learning will be lost, needing to be reinvented at some point in the future.

Little consideration of supported decision-making and advance planning

While the Commission recognised that the “ability to plan in advance” and express what a person wants in advance of a time when they are not able to communicate, was a form of supported decision-making (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.6, p.118), there was little discussion beyond this. The intersection of advance planning documents with supported decision-making is generally not well explored in the existing literature, although has received some attention in the context of episodic mental illnesses (Callaghan & Ryan, Citation2016; Kokanović et al., Citation2018; Maylea et al., Citation2018). There is a growing literature around advance care, and end of life planning with people with intellectual disabilities (Kirkendall et al., Citation2017; McKenzie et al., Citation2017), who are often excluded by legislative capacity thresholds from making formal directives. For example, a recent study documented a case study using supported decision-making to successfully enable a person with a mild intellectual disability to make a values directive under the Medical Treatment Planning and Decisions Act 2016 (Vic), but it also identified that this Act effectively excluded anyone with more severe intellectual disabilities (Sheahan et al., Citation2023). The lack of engagement by the Commission regarding whether advance planning documents might be a useful tool to enable supported decision-making, seems like a missed opportunity.

Focus on distributional equity

Principle 10 of the supported decision-making principles recommended by the Commission focuses on cultural safety and turns a much-needed eye towards populations who have largely been absent from the supported decision-making scholarship to date. (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.10). It accords with the call for the need for recognition of diversity that was made in the Research Report (Bigby et al., Citation2023). The Commission expressly includes First Nations people and culturally and linguistically diverse people with disabilities in principle 10. In recognising that provision of supported decision-making may need to be “culturally safe, sensitive and responsive… [including] recognising the importance of maintaining a person’s cultural and linguistic environment and set of values” (CoA, Citation2023, Sept. 29, Vol.10, p.17), the Commission is explicitly recognising that no “one size fits all” will work across populations and cultures.

A further group of people with disabilities who are often “left out” of the supported decision-making conversation is those who are socially isolated with no forms of natural support. As the Commission heard, this is a situation common to many people with intellectual disabilities living in group homes. While small scale pilots have tried matching people with volunteer supporters, these initiatives are considered resource intensive, requiring supervision of supporters, and experiencing difficulties in recruitment (Then et al., Citation2023). The Commission took on board the evidence on this point; it acknowledged and included the concept of equitable access to appropriate support in principle 5 of their supported decision-making principles on “Access to support.” This was based on the concept of distributional equity recommended as a principle in the Research Report. That report recognised that “deep social and geographic inequities in access” to supported decision-making and that reform and initiatives should be premised on the ethical principle of distributional equity where those disadvantaged in access to supported decision-making ought to be prioritised in new programs or initiatives (Bigby et al., Citation2023, pp. 40–41). This is a small step towards ensuring that those who are socially isolated and without social capital may also eventually reap the benefits of supported decision-making.

Conclusion

The Commission gave considerable focus to supported decision-making during its term. It dedicated resources to roundtables, hearings, and commissioned research to obtain up-to-date evidence on what supported decision-making is, how it is implemented, and what it means to people with disabilities. Its adoption of a principled approach to supported decision-making is a step in the right direction that recognises the messy reality of decision-making with and for people with intellectual disabilities. However, overall, the findings and recommendations of the Commission fell short of providing concrete guidance to those involved in the everyday lives of those with intellectual disabilities. Instead, following past law reform agencies’ work, recommendations focused unduly on legal reform of state and territory guardianship regimes, rather than adopting a more holistic approach to embedding supported decision-making across multiple services and sectors, as was suggested by evidence obtained from witnesses, roundtable participants, and the research. While these recommendations will likely provide a much-needed prompt to continue legal reform efforts, they also present a missed opportunity for the Commission. Guidance on implementation and capacity building of supported decision-making at ground level is still needed and will likely have more of an impact on the everyday lives of people with intellectual disabilities than simply changing the law.

Disclosure statement

Professor Christine Bigby is the current editor of Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Both authors were part of the research team commissioned by the Disability Royal Commission to provide the research report on supported decision-making that is referred to in this article.

Notes

1 Accepted under the editorship of Dr Ilan Wiesel, Associate Editor, Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.

Full details of the mission and scope of the Disability Royal Commission (2019–2023) and a guide to finding its various types of documents are discussed in the Editorial for this Issue, available freely online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23297018.2024.2319365.

2 Guardianship and Administration Act 2019 (Vic) ss 8-9; Guardianship and Administration Amendment Act 2023 (Tas) (yet to be proclaimed into force); Guardianship and Management of Property Act 2023 (ACT) s.4.

References

- Australian Law Reform Commission. (2014). Equality, capacity and disability in Commonwealth laws. https://www.alrc.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/alrc_124_whole_pdf_file.pdf

- Bigby, C., Carney, T., Then, S.-N., Wiesel, I., Sinclair, C., Douglas, J., & Duffy, J. (2023). Diversity, dignity, equity and best practice: A framework for supported decision-making. Disability Royal Commision. https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/policy-and-research/research-program

- Callaghan, S., & Ryan, C. J. (2016). An evolving revolution: Evaluating Australia’s compliance with the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in mental health law. University of New South Wales Law Journal, 39(2), 596.

- Chesterman, J. (2024). Adult safeguarding in Australia after the Disability Royal Commission. Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/23297018.2024.2316291

- Commonwealth of Australia. (2019–2023). Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability. Our public hearings. [transcripts]. https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/public-hearings/our-public-hearings

- Commonwealth of Australia. (2022, May 16). Roundtable: Supported decision-making and guardianship proposals for reform. Disability Royal Commission. https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/system/files/2022-10/Roundtable%20-%20Supported%20decision-making%20and%20guardianship%20-%20Proposals%20for%20reform.pdf

- Commonwealth of Australia. (2022, October). Roundtable: Supported decision-making and guardianship summary report. Disability Royal Commission. https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/system/files/2022-10/Roundtable%20-%20Supported%20decision-making%20and%20guardianship%20-%20Summary%20report.pdf

- Commonwealth of Australia. (2023, September 29). Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability: Final report. (Updated Nov. 2). https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/publications/final-report

- Kirkendall, A., Linton, K., & Farris, S. (2017). Intellectual disabilities and decision making at end of life: A literature review. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities: JARID, 30(6), 982–994. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12270

- Kokanović, R., Brophy, L., McSherry, B., Flore, J., Moeller-Saxone, K., & Herrman, H. (2018). Supported decision-making from the perspectives of mental health service users, family members supporting them and mental health practitioners. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 52(9), 826–833. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867418784177

- Maylea, C., Jorgensen, A., Matta, S., Ogilvie, K., & Wallin, P. (2018). Consumers’ experiences of mental health advance statements. Laws, 7(2), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws7020022

- McCallum, R. (2020). The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: An assessment of Australia’s level of compliance. Commonwealth of Australia. Research program | Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability

- McKenzie, N., Mirfin‐Veitch, B., Conder, J., & Brandford, S. (2017). “I'm still here”: Exploring what matters to people with intellectual disability during advance care planning. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities: JARID, 30(6), 1089–1098. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12355

- Parliament of Tasmania, House of Assembly. (2023). Report of debates (Aug.10). https://www.parliament.tas.gov.au/hansard

- Quinn, G. (2023). Transformation of services for persons with disabilities: Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities A/HRC/52/32, 52nd sess. Agenda Item, 3 March 31, 2023.

- Sheahan, M., Bigby, C., & Douglas, J. (2023). Policy and practice issues in making an advance care directive with decision making support: A case study. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 58(2), 381–397. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.261

- Spivakovsky, C., Steele, L., & Wadiwel, D. (2023). Restrictive practices: A pathway to elimination. Commonwealth of Australia. Research program | Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability.

- Then, S.-N., Carney, T., Bigby, C., & Douglas, J. (2018). Supporting decision-making of adults with cognitive disabilities: The role of Law Reform Agencies – Recommendations, rationales and influence. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 61, 64–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2018.09.001

- Then, S.-N., Carney, T., Bigby, C., Wiesel, I., Smith, E., & Douglas, J. (2022). Moving from support for decision-making to substitute decision-making: Legal frameworks and perspectives of supporters of adults with Intellectual disabilities. Law in Context, 37(3), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.26826/law-in-context.v37i3.174

- Then, S.-N., Duffy, J., Bigby, C., Sinclair, C., Wiesel, I., Carney, T., & Douglas, J. (2023). Delivering decision making support to people with cognitive disability—What more has been learned from pilot programmes in Australia and internationally from 2016 to 2021? Australian Journal of Social Issues. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.295

- Then, S.-N., White, B., & Willmott, L. (2024). Adults who lack capacity: Substitute decision-making. In B. White, F. J. McDonald, L. Willmott, & S.-N. Then (Eds.), Health law in Australia (4th ed., pp. 221). Lawbook Co., Thomson Reuters Professional Australia Limited.

- United Nations. (2008). Multilateral treaties deposited with the Secretary-General: CRPD Declarations and Reservations Australia. https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=IV-15&chapter=4&clang=_en#EndDec

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. (2006). Opened for signature March 30, 2007, 2515 UNTS 15 (entered into force 3 May 3, 2008).