ABSTRACT

While practitioners around the globe deal with the challenges posed by COVID-19, scholars of diplomacy were wondering where did all the health attachés go? Reviewing the scholarship on global health diplomacy shows, on the one hand, that health attachés are at the core of global health diplomacy while on the other, data about their role and impact is lacking. International diplomatic negotiations on health take place at the bilateral and multilateral level and rely on diplomats – and it is the health attachés that have the highest level of legitimacy. The fact that an empirical repository on these diplomats is missing comes as a surprise as at the regional level of diplomacy – the European Union – there is a considerable network of health attachés in place since the 1980s. Against this background this articles explores five distinct roles that EU health attachés embrace in Brussels and its implications for health diplomacy.

Introduction

At the turn of the century, global health challenges increased in importance. They arose through SARS in 2002-04, H1N5 in 2008, Ebola in 2014, and climaxed in today's COVID-19 crisis. Despite the recent positive dynamics brought about by vaccination campaigns, the COVID-19 pandemic remains what United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres labels “the most challenging crisis we have faced since the Second World War” (Guterres, Citation2020). COVID-19 not only affected human bodies and state economies but turned out to be a test case for international cooperation and became a central theme in the scholarly debate on “global health diplomacy” (GHD). The pandemic steered discussions on this topic towards normative concerns oscillating between national security interests, on the one hand, and global altruism, on the other, resulting from government’s initial unilateral reaction to a global confrontation and disengagement from their collective policy-making constructs. Taking into consideration the increased tendencies of states to internalise in times of global health crises, a key underlying question arose – “where have all the health attachés gone?” (Berridge, Citation2020) – which we seek to elucidate in this article.

Health attachés are “diplomats who are assigned the health portfolio [in diplomatic representations]” (Kickbusch, Nikogosian, Kazatchkine, & Kökény, Citation2021, p. 127), and are a fundamental part of the policy-shaping process surrounding health challenges. As such, they are considered core actors of global health diplomacy (GHD) given their ability to serve as required bridge-builders and communication channels (Al Bayaa, Citation2020; Brown, Mackey, Shapiro, Kolker, & Novotny, Citation2014). Health attachés, it is argued, would thus be well equipped to safeguard against health hazards and foster solidarity in the international community (Al Bayaa, Citation2020). Yet, health attachés remain scarce at the bilateral level of diplomacy such as in national embassies in host countries (Berridge, Citation2020), as well as at the international level – in the WHO (Kickbusch et al., Citation2021). Shortly after the Second World War, health attachés were increasingly delegated by several countries. Even before, however, health attachés have played an important role in trade and transportation since the first International Sanitary Conference in 1815, particularly in supervising the sanitary control in ports to prevent the spread of infectious diseases (Berridge, Citation2020). Today, however, they are so scarce on the ground that they appear to have “gone”.

This article comes to address a significant gap – to add to the scholarly repository on health attachés by bringing forward the focus on the role of EU health attachés specifically. In scholarly research little spotlight has been given to their role in global health diplomacy as the ongoing discussions focused on the role of senior officials such as the EU High Representative (HR) (Amadio Viceré, Tercovich, & Carta, Citation2020); how societies want to “solve” emergencies (Wuropulos, Citation2020); and covered themes such as vaccine and mask diplomacy, health as foreign policy, the rise, and challenges to health diplomacy. By choosing for our study health attachés as unit of analysis we add valuable knowledge to the academic literature on the core of GHD – health attachés – who, as scholars argue, have the highest level of legitimacy especially in multilateral settings (Brown, Citation2016; Katz, Kornblet, Grace, Lief, & Fischer, Citation2011). Moreover, by evaluating the role of these attachés at the regional level of diplomacy – the European Union (EU) – where there is a considerable network of health attachés in place, we put forward an empirical repository on the role of health attachés that is currently lacking.

The EU is not only the largest regional bloc in economic terms but it also exemplifies the most advanced form of regional integration (Gebhard, Citation2017) with the potential to promote policy coherence by pooling knowledge and sharing resources (Chattu & Chami, Citation2020), which is of utmost importance in today’s interdependent world (considering the COVID-19 pandemic specifically). Health is primarily a technical field, but as this pandemic has shown, also overlaps with areas that are more traditional in diplomatic circles, such as trade, economics, and politics. And while they are not career diplomats, the health attachés in the Permanent Representations (PermReps) of the Member States are civil servants with expertise in health, seconded by national health ministries, and given diplomatic status and responsibilities. Unlike diplomats, who are seen as generalists, it is the specialised technical staff (such as health attachés) who have the knowledge and the expertise to provide diplomacy with the much-needed substance. Furthermore, given the call for more cooperation in global health diplomacy, it is of particular interest to study this cadre in the European context that relies heavily on the cooperative efforts of its Member States. EU health attachés belong to the diplomatic staff of the PermReps of the 27 Member States to the EU since 1980s. Thus, we find it useful to examine EU health attachés in particular – who form a permanent cadre – to explore their relevance (or lack thereof) to health diplomacy.

Given the large lack of evidence, this article relies on collecting data from primary sources and cross-checking findings with data collected from secondary sources. Exploring diplomatic practices on the ground is often constrained by diplomacy’s secretive nature and ethnographic participant observation in foreign policy research gives way in favour of textual analysis and interviews (Hofius, Citation2016). In addition to an extensive literature review on global health diplomacy, interviewing practitioners in the field enabled this research to gain insights not yet publicly available and identify five distinct roles of EU health attachés. We drew a representative sample from several identified clusters: EU accession (old versus new Member States),Footnote1 geographical spreadFootnote2, and their posture towards EU integration.Footnote3 Ten semi-structures interviews were conducted in May-August 2021 covering at least one country from each cluster, and subcluster (see endnotes 1-3). All interviews were codified and made anonymous to ensure the discretion of the interviewees and each participant received a corresponding alphanumeric designation (INT1, INT2, etc.) according to which we present data from the interviews.Footnote4 Our interviews followed a guide, lasted 60 min on average, and were semi-structured. The discussion covered questions about content of EU health diplomacy (including during COVID-19), their mandate, the implementation of their responsibilities as well as the cooperation under EU diplomacy during the pandemic.

To address the guiding question of this article, we start by unpacking global health diplomacy and explaining the different actors and levels of analysis. This section helps identify a series of research gaps such as the scarcity of scholarly research on the role of health attachés or the little focus given to the regional level of health diplomacy (such as the EU). The following section maps out key actors responsible for EU health diplomacy and positions the EU health attachés. The empirical section then introduces and explains the five key roles of health attachés in Brussels: information-gatherer and -provider; networker and contact supplier; early warner; representor and adviser; and negotiator of draft legislation. In the final section of this article, we discuss our findings and show how the latter deepen and widen the scope of work of health attachés at a regional level. We conclude by suggesting avenues for further research.

Global health diplomacy: actors and levels of analysis

In diplomacy, health is traditionally treated as subordinate (vis-à-vis trade matters and high politics), and is, at best, part of a larger portfolio. An example are German embassies, where, at about thirty missions abroad, health issues are primarily covered by so-called “social affairs officers” in the context of a wider brief. Nonetheless, from the end of the Cold War, the terms health diplomacy and then global health diplomacy, entered academic and policy discussions with increasing tenacity, rooted in the acceleration of (re)emerging infectious diseases that raised alarm since the 1990s (Almeida, Citation2020). Even today global health diplomacy (GHD) is considered an emerging field, which lacks its own theoretical and analytical frameworks as well as a consistent body of empirical data (Adams, Novotny, & Leslie, Citation2008; Almeida, Citation2020; Chattu & Chami, Citation2020; Ruckert, Labonté, Lencucha, Runnels, & Gagnon, Citation2016). Therefore, scholars have examined GHD predominantly through conceptual lenses – it refers to the interrelation between health and foreign policy and is largely associated with international cooperation in the field of health (Almeida, Citation2020).

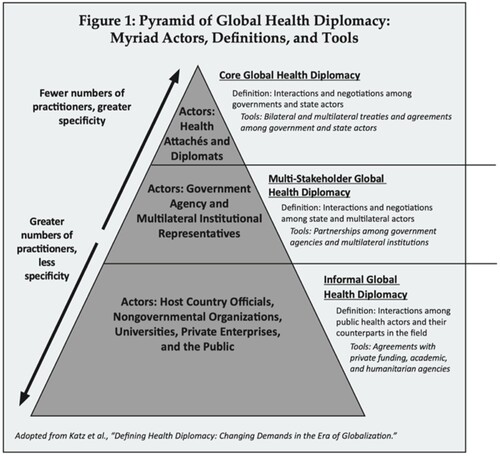

The most frequent debate on GHD streamlines its various actors and levels of analysis. In terms of levels of analyses, Katz et al. (Citation2011) examines the types of GHD, in which the actors are to be located and interact, as “core”, “multi-stakeholder”, and “informal” GHD (as shown in , based on the research of Brown et al., Citation2014). Core GHD is expressed along the understanding of senior level negotiations between governments through the agency of health attachés and diplomats (Katz et al., Citation2011); that may take place both in bilateral and multilateral spheres. Negotiating the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) and the revised International Health Regulations (IHR) through the WHO in 2005 constitutes one of the exemplifications of core GHD. In contrast, multi-stakeholder GHD is much broader and encompasses relations between states and non-state actors, such as with PPPs or private enterprises (ibid). Initiatives such as the COVAX facility, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria (GFATM), or the Gavi AllianceFootnote5 would fall under this type. Lastly, informal GHD includes interaction among “free agents” comprising private funders, e.g. the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and NGOs, but moreover international research collaborations, or humanitarian assistance programmes (ibid).

Figure 1. Pyramid of Global Health Diplomacy. Source: Obtained from Brown et al., Citation2014

Ruckert et al. (Citation2016) summarise the actors as “individual”, “national/domestic”, and “international/global”. Research on the role of individuals in GHD is inferior, although the interest in “celebrity diplomacy”, i.e. people in the public eye promoting health causes, is accelerating (Kirton & Guebert, Citation2009). More research focuses on the national/domestic level, and how interest groups, nongovernmental organisations (NGOs), think tanks and research organisations motivate health-affiliated policies. Yet, the central part of research is directed at the international/global level and addresses the promotion of health in the international system. This not only includes governments and their delegated attachés but specifically the agency of international organisations, international nongovernmental organisations (INGOs), pharma corporations, public-private partnerships (PPPs), and private-sector organisations such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

What is most surprising is the scarcity of scholarly research on the regional level of health diplomacy. A regional level of analysis, comprising e.g. political entities like the EU or the African Union, could de facto be well situated between the “national/domestic” and “international/global” levels of analysis of GHD. The lack of research on regional entities is particularly problematic amidst the COVID-19 pandemic given their potential to achieve cooperation by pooling knowledge and sharing resources. Equally astounding is the scarce coverage on what is perceived to be GHD’ core actors, that is health attachés, in comparison to the increased attention given to GHD as a research field. Brown, Bergmann, Novotny, and Mackey (Citation2018) is among the few who have empirically investigated the profile of health attachés. Their interviews with three health attachés accredited to the US and four US health attachés accredited abroad revealed some of their daily practices. These include “tracking existing and negotiating new agreements, organizing visits and attending meetings, drafting briefing documents, and meeting counterparts, collaborators, and other actors vested in public health issues in the country or region of assignment” (ibidem, pp. 6).

States around the world continue to appoint health attachés, though sporadically. To date, the US has six health attachés stationed abroad (Brazil, China, India, Mexico, South Africa, and Switzerland), leading the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to state that it has health attachés represented “in almost every region of the world” (US HHS, Citation2021). South Africa appointed a health attaché at its embassy in Havana to oversee the large number of its medical students thereFootnote6, and more recently, the Belgian government delegated a health attaché to its embassy in Beijing to accelerate the lifting of Chinese embargoes on its meat exports (The Brussels Times, Citation2019). There seems to be a recognition of the importance of health in foreign affairs with slightly more health attachés being deployed and requested in recent years. By linking missing knowledge on health attachés with the limited research on the regional level of health diplomacy, this article sheds light on the established network of EU health attachés and the five distinct roles that they have, elaborated in the following.

Health attachés in the EU: where to find them

The nature of diplomatic interaction in the EU, in health, is a matter of competences, with the latter being subject to Member States’ responsibility. The Union only has “supporting competence” and can solely support, coordinate, or complement the action of EU Member States on health matters. Thus, it is the machinery of the Council, the EU’s intergovernmental body and epicentre for diplomatic interaction on health among EU countries, where politicians and diplomats interact with their counterparts and important EU agencies (Buonanno & Nugent, Citation2013). The Council is made up of the ministers representing the Member States, who convene to discuss, amend, and enact legislation, as well as coordinate policies (ibid). Health ministers pass legislation in the following areas: “patients’ rights in cross-border healthcare; medicines and medical devices; serious cross-border health threats; cancer, tobacco, and the promotion of good health; and organs, bloods, tissues, and cells” (Council of the EU, Citationn.d.a).

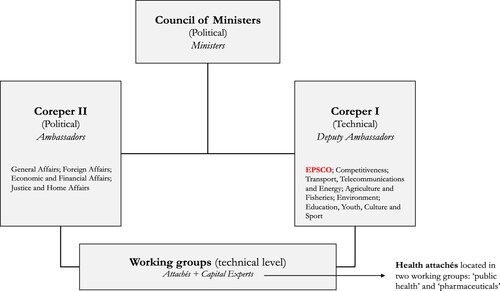

Out of the ten different Council formations, health attachés are embedded in the set-up of the Employment, Social Policy, Health, and Consumer Affairs Council (EPSCO)Footnote7 working groups “public health” and “pharmaceuticals”. There, they prepare the work of COREPER I, which in turn prepares the work of the Council (Art. 240(1), TFEU). While health attachés are engaged in different settings, the two working groups represent the foundation of their diplomatic practice. The Council’s set-up () is reminiscent of the importance of one of the key practices of diplomacy towards the daily functioning of the EU, namely, negotiating (Hayes-Renshaw, Citation2017; Maurer & Wright, Citation2020). However, it also underlines how EU diplomatic practices pole apart from textbook diplomacy by being significantly more skewed towards negotiating legislation. As one of the interviewees explained:

EU diplomacy in general is different from usual diplomacy. The Council being a legislative body, [the job of diplomats] implies in-depth knowledge of the EU and the national legislative frameworks and consists in practice in intense work and discussions on future EU laws. (INT7)

Despite these general observations, some discrepancies among several PermReps could be identified. Similar to career diplomats, health attachés usually rotate back to their home department every three to four years. But there are also exceptions of Member States’ health attachés stationed in Brussels for up to 10–15 years. Moreover, large countries tend to have two health attachés in their health units, while small ones usually only have one. Generally, because of the pandemic, the staff structure is changing, with Member States increasing their personnel of health attachés in their PermReps in Brussels but also, for instance, in their representations in Geneva to the WHO (INT4).

Five distinct roles for EU health attachés

The findings presented here rely on the (virtual) fieldwork conducted in Brussels - expert interviews with EU health attachés. Besides the fact that such data gave us the opportunity to gain insights into their profile and portfolio (data which is not publicly available), we were able to reveal the microcosmos of specialised knowledge and practices of this diplomatic community. This research looks at the population of Member State health attachés in Brussels, who are part of the staff of PermReps to the EU. The latter are subdivided into thematic policy units and embody one to two health attachés within the unit, depending on the size and scope of the respective Member State. Therefore, our eligibility criteria narrowed down the pool of potential interview participants to include persons listed as “attaché”, or explicitly as “health attaché”, within the health units on the PermReps’ official websites. Based on the fieldwork conducted, five distinct roles of the health attachés at the EU level have been identified: information-gatherer and -provider; networker and contact supplier; early warner; representer and advisor; and negotiator of draft legislation.

I. Information-gatherer, and -Provider

The daily practices of health attachés can largely be assigned to the diplomatic function of communication, based on a variety of tasks related to gathering and providing information. They gather information in and about Brussels, especially on the position of other Member States and the EU institutions on legislative proposals. Information is gathered through attending their working groups and a variety of other meetings of, for instance, the European Parliament’s committees or the Commission’s Director-General (DG) on health – DG Santé (INT1-6; INT8-10). Usually, the communication channels originating from health attachés can reach all stakeholders involved in the policymaking regarding the public health domain (INT9). The gained information is channelled through reports or written comments in a one-way street via the attaché to the capital, where it reaches the responsible officials, mostly in the International Affairs departments of the Ministries of Health (INT8; INT10). In the middle of so many countries, institutions, and stakeholders, the amount of information to fuel the capital can be extremely challenging for EU health attachés. As one of the diplomats shared: “You need to process. You need to explain, to analyse, to filter, as well as to make sure that all is well understood by [the capital]” (INT9). Hence, the information-gathering and -providing comes in tandem with a filtering function, smoothing out and prioritising what issues in the Brussels-context is relevant for one’s national capital/ministry.

Health attachés also use the function of communication “to explain in [capital X] why Brussels is difficult in some respects, and also to explain in Brussels why [capital X] is problematic on many issues” (INT4) – as explained by one of the interviewees; and which is subject to their embedding in two environments: the domestic and the European one (INT4). An essential part of the communication repertoire of an EU health attaché is thus to streamline interdependencies and overlaps between the national and European settings. The attachés representing newer Member States are additionally tasked with enhancing communication between Brussels and their national capitals in the first place – as was pointed out by one of the interviewees: “[t]here are still many Health Ministries that are only marginally interested in the EU” (INT4). In such cases the influence of a Brussels attaché can be very high through the ability to influence the content of a new engagement (INT4; INT5).

Additionally, communication goes beyond the government offices in the capitals. Since the outbreak of COVID-19 for instance, Brussels-based health attachés have increasingly been exchanging information with their counterparts – if existing – in Geneva, with the latter “sending a lot of stuff to also put [the] government under pressure to do something [in Brussels]” (INT5). On the matter of the COVID-19 pandemic, communicating with the media became a regular part of an attaché’s weekly agenda, to shed light on unclear information. For example, in the early stages of the pandemic, they received many questions from national journalists on the vaccination policies of other partner countries or, in the more recent stages, about the Digital COVID-19 Certificate, which caused confusion among European publics (INT2). Generally, during this pandemic, the foci of information moved beyond the content of legislative dossiers. Crises response and management questions such as “What is your age limit for AstraZeneca” (INT5) or “How long do you wait between two doses of Pfizer?” were posed among the health attachés of the different Member States with the answers being directly forwarded to the respective capitals. In this way the communicative exposure for health attachés amplifies in times of crises.

II. Networker and contact supplier

Establishing and maintaining communication channels naturally provides health attachés in Brussels with a wide network of contacts, which puts them in an advantageous position vis-à-vis national experts who only come for the Council deliberations and are thus largely unfamiliar with channels beyond these settings (INT1). One should not expect a national position to be solely achieved in the Council. The Commission, proposing the legislative files to be discussed in the Council, is an important actor with whom it is essential to work, too. For instance, to know about and potentially pre-influence the content of proposed files is just as important (INT1; INT3; INT5; INT6; INT8-10). As one diplomat explained: “In order to get what you want you cannot expect to go to a ministers Council and say it or even to a meeting of health attachés or experts or ambassadors. You need to start working with the Commission before they publish the file” (INT3). And it is the role of health attachés to know “how to contact, and who to contact” (INT1) with a large part of their daily practice being to provide their colleagues in the national ministries with the right interlocutors, thus bridging the contact to EU institutions or counterparts in other Member States (INT9). As one health attachés observed: “Being here makes it easier to get into contact with my colleagues and I am able to provide very fast answers to my capital in terms of “what does country X mean in terms of certain things?”, “what does country Y have of concerns?” “what should we be aware of’? ‘what will be happening next week?’” (INT2). While the Health Ministries also have their own, direct lines to other Member States and the Commission, which is especially true for the higher levels of power (INT8), the rule is that communication between Member State and the Commission always goes through the PermReps and, hence, in the case of health matters, through the health attaché (INT6). In crises situations specifically, prompt contact to a multitude of states is necessary – for the supply of which EU health attachés are ideally placed. This can be illustrated by the following example: heads of Cabinet swiftly requested the contact of their counterparts following the outbreak of COVID-19, asking their attachés in Brussels: “Who can I contact in the cabinet of the French ministry, in the Dutch, in the Austrian, in the Italian?” (INT6). This function of networker became even more recognised in capitals as there is an ever-increasing need to connect and coordinate. As a matter of fact, a health attaché serves as a conduit for various functionaries, from capital experts to high-rank officials such as ministers and other cabinet members, for them to get into contact with representatives of EU institutions and other Member States on EU-related matters. They can be seen as a liaison that, through the provision of contacts, connects their respective domestic and EU environments.

III. Early warner

The proximity of health attachés both to EU Member States and to the EU institutions proves valuable not only because they can provide their capitals with the contacts from their Brussels network and vice versa. It also turns them into useful antennas for their capitals. In particular, the close contact to the Commission – which as “the guardian of the Treaties” (Steunenberg, Citation2010, p. 5) monitors Member States’ compliance with EU obligations – ensures that any potential frictions and discrepancies are rapidly brought to the attention of the health attachés, and thus the capitals. As one of the diplomats emphasised: “when there is criticism, you hear it much more directly in Brussels than in the capital” (INT4).

Apart from criticism to national policies potentially clashing with EU obligations, early warning also comes with legislative proposals initiated by the Commission. Given health attachés’ consciousness of the national interests in health policy coordination at the EU, they can assess whether an upcoming proposal opposes these. “Not everybody knows what is going on there. But an attaché going to that meeting sees that some important decision is coming up. The Commission is trying to get something accepted” (INT1). The government can be made aware of the concern, enabling respective officials in the capitals to counteract these developments ex ante the publication by the Commission (INT3; INT4). In this way, health attachés in Brussels become a useful resource for their capitals by acting as an early warning system that can improve intermediation between the EU and its Member States, thus eventually mitigating long-term conflicts over current or future policies. In times of social distancing, this specific role is inevitably limited given the lack of frequent encounters in the EU quarter, where informal conversations often reveal these tendencies (INT4).

IV. Representor and adviser

EU health attachés not only filter information, contacts, and warnings to the capital, but also speak on behalf of their government in Brussels. They are the national delegates sent to Brussels with the mandate of “conveying and defending the position of [their] country in the best possible way” (INT7): “you want as much as possible your position translated in the final text” (INT6). This includes not only speaking on behalf of, and communicating, the government’s position on a submitted dossier in the working group (INT5-7), but also preparatory work, e.g. in reference to the networking function, making sure that national preferences already find consideration in the initiative phase of a legislative file. However, the question is “whether [one has] the ability to influence the content of certain processes or whether one is there in a notarial capacity, to sell the line” (INT4) – this discrepancy in shaping capacities was frequently emphasised by the interviewees (INT1; INT3; INT5; INT7). There are attachés who have creative power conveyed by the capitals and attachés who, as reiterated by one of the diplomats her/himself, “don’t even go to the toilet without the instructions by the capital” (INT1). Especially in Eastern European countries, there is a long tradition of red lines, and creative power being unwelcome, which, in fact, was confirmed in conversation with the latter.

Many others emphasised their formative impact vis-à-vis capital instructions – alias “we are not like robots” (INT1). For instance, through preparing the working groups in conjunction with their capital (INT6; INT9), and occasionally even writing the instructions for themselves (INT3; INT5). Such elasticities are, however, often limited to smaller Member States with small ministries. To illustrate, one of the health attachés representing a smaller country shared that this role implies not only writing the instructions for her/himself, but even the speeches for their health minister. During COVID-19 this became a key role as these public discourses were also written for the foreign and even prime minister when they would come to attend the Foreign Affairs Council (FAC) and European Council meetings respectively. By contrast, EU countries with larger representations do not have their attachés engaged in writing speeches when the Heads of States and Government are attending high level European Council meetings.

In this role, health attachés also signal to their capitals what is possible in terms of the Council’s negotiating logic – referring to the prevalence of qualified majority voting (QMV).Footnote9 This implies that instructions coming from the capital, for example such as rejecting the inclusion of gender consideration in a legislative text, can simply be bypassed. If a group of countries, who instead advocate gender matters, hold the majority, they will avoid approaching the “troublemaker” (Juncos & Pomorska, Citation2006, p. 12) in later negotiations. As one of the attachés confirmed: “although we don’t like [gender considerations], voting against means first, that we lost, second, that we will not be a partner in the future discussions” (INT1). This negotiation logic is often intangible for the capitals, who tend to design inelastic instructions (INT1; INT4). Therefore, health attachés often engage in brokering this rigidity, convincing their government to “move a little, change a bit” (INT4), i.e. turning into advisers by helping them understand what is realistic to achieve in EU negotiations (INT1; INT6; INT9). As one diplomat reiterated: “If the talks are going somewhere in a direction where our position is completely against it, then we must re-assess the situation and see if we need to ask the government for more flexibility or to change the position” (INT3).

V. Negotiator of draft legislation

Acting as government representatives, EU health attachés also resort to negotiating national positions in the event of Member States’ diverging interests on the subject of reaching agreement on future EU law. As was reiterated by one of the diplomats: “Every text [the Council] negotiate[s] comes to the level of attachés before it goes to the ambassadors” (INT3). While it is the ambassadors in COREPER, and then the ministers, who are closing files, the negotiations are pre-cooked at the working group level, which is the level of the health attachés (INT3). “The role is the participation in the policy development through the working groups of the Council” (INT9) and in the latter, usually in liaison with national experts, health attachés discuss “article by article, chapter by chapter” (INT6) to find out where Member States can connect, and where divergent interests need to be negotiated (INT1-6; INT8; INT9). Balancing diverging interests often materialises in consecutive bloc building: first, one finds like-minded countries on a certain topic – either in formal or informal, multilateral, or bilateral gatherings – to then approach the non-like-minded opponents in united front. The majority wins (INT1; INT2; INT5; INT8).

The content and intensity of the legislation health attachés draft and negotiate necessarily moves on a time–space continuum and is subject to the demands of the day. Consequently, their legislative workload during the COVID-19 pandemic increased immensely. Pre-COVID, health attachés had one legislative file on the table which they have been discussing for three years, the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) fileFootnote10 which makes them argue they had “quite an easy life” (INT5), “even boring” (INT1) – whereas during the course of the pandemic, they are confronted with significantly more legislative files – including the COVID-19 Digital Certificates or the Health Union Package, with the latter alone consisting of three separate dossiersFootnote11, and which they “need to agree in some months and not years like [they] previously did” (INT6). The urgent attention the pandemic also led to the postponement of legislative proposals with a different thematic focus, such as the Cancer Action Plan, the health attachés would have seen next on their agenda (INT3).

In the ordinary legislative procedure (OLP), the European Parliament (EP) is co-legislating the same dossier as the Council.Footnote12 In this circumstance the aim of the Council is to create positive conditions vis-à-vis the EP, also, to demand reciprocity (INT4). Health attachés often attend workshops and/or conferences organised by Members of the EP (MEPs) on public health issues. This opens the door for a strategic opportunity: “You go there, say something for five minutes about how important the issue is” (INT4), i.e. doing the MEP(s) a favour, which, in turn, enables the attachés to ask for reciprocity later in the trialogues, for instance, when they need help to convince of the importance of a specific article (ibid).Footnote13

However, the EP is not the only actor alongside the Council in the OLP. One of the interviewees highlighted: “The proactive part is finding out “what is the Commission even preparing?” because […] if you wait just for the initiatives from the Commission, then the influence you could have later on is limited” (INT8). “You already want to have something on their plates”, as told by another diplomat in the same vein (INT9). In this respect, health attachés are not equipped with the same formative capacities. This is not only due to the differing elasticities of their instructions, which has already been taken up, but above all subject to their respective know-how, experience, and resources for these strategic efforts, which the attachés of smaller and newer Member States often lack. In many cases it is only through taking over the Council PresidencyFootnote14 that those countries can shape the content of legislative files: “we used to not have the knowledge on how to negotiate health [prior to the Presidency]” (INT3). Despite these power dynamics, negotiating with all possible stakeholders in the process of drafting legislation concludes the examination and interpretation of the most important diplomatic tasks health attachés fulfil in the EU.

Conclusion: the invisible substance of health diplomacy – EU health attachés

At the outset of the pandemic, the EU faced criticism for a lack of diplomatic cooperation in health, which some linked with the failure to uphold the political commitment made back in the 2010 Council Conclusions with the main pitfalls being the lack of solidarity, legislation, and data sharing (Aluttis, Krafft, & Brand, Citation2014; Bergner, Pas, Schaik, & Voss, Citation2020; Kickbusch & Franz, Citation2020; Steurs, van de Pas, Decoster, Delputte, & Orbie, Citation2017). As the virus spread, the first efforts taken by EU Member States were in favour of national protection with a largely uncoordinated, and non-solidaric responses to the crisis – as pointed out by the Jacques Delors Centre (Koenig & Stahl, Citation2020). In turn, COVID-19 also became a wake-up call for increased diplomatic cooperation as it, in fact, spurred the enaction of binding EU law on health matters, such as concluding negotiations on the HTA Regulation, which had been ongoing since 2018, and negotiation of new Regulations such as the EU COVID-19 Digital Certificates or the Health Union Package – with health attachés’ role as negotiators reportedly being of critical value for both (INT1-5; INT9). To the surprise of many interviewees (INT2-6; INT9) successful compliance was also achieved with non-binding legal acts such as the Recommendation on the risk classification of EU regions, where the traffic light system based on incidence and testing density has been widely adopted across the Member States despite the lack of legally binding status. Missing most of the pre-set protective frameworks against global health threats, it is remarkable how swiftly and to what extent the EU was able to get its cooperation mechanisms up and running.

What becomes most obvious is that health attachés embrace the core functions of diplomacy, such as communication and negotiation, without necessarily being career trained diplomats. By enacting these function they could ensure the cooperative effects for EU health diplomacy. Existing research on health attachés on a bilateral level emphasises some of the roles identified in this research, namely: “tracking existing and negotiating new agreements, organizing visits and attending meetings, drafting briefing documents, and meeting counterparts, collaborators, and other actors vested in public health issues in the country or region of assignment” (Brown et al., Citation2018, p. 6). But our findings deepen and widen the scope of work of health attachés and the way they consummate the communication function at a regional level. EU health attachés, in fact, proved well equipped to safeguard against health hazards and foster solidarity in regional entities when faced with global health challenges. Ideal placement and established network to bridge contacts with representatives of EU institutions and other Member States can prove crucial to foster alliances in crises times. By knowing how and whom to approach, health attachés can bring higher ranked officials together with their counterparts swiftly to stimulate dialogue.

Our findings also show that to achieve pre-set objectives, health attachés engaged in extensive negotiation, the function through which diplomacy happens. At the EU level they are involved in “negotiating new agreements”, and “drafting documents”, which implies enormous amounts of complex legal texts, as opposed to standard diplomatic documents such as reports or written comments for the capital – which are nevertheless also part of the everyday tasks of a European health attaché. The decision-making competence of a health attaché in the EU is therefore somewhat more limited but the impact on policy through preparing legislation outweighs that of their colleagues in bilateral embassies. To fully embrace the function of negotiation, health attachés heavily rely on networking, which is quintessential at the regional level of diplomacy. It reaches a level that is hardly possible for a bilateral attaché and goes beyond the link between the capital and the host country, which also puts the EU attachés in the advantageous position of providing countless contacts and early warnings to their capital.

The academic added value of such findings is that they create opportunities for cross-fertilisation as it contributes to the discussion of the academic literature on the practice turn in IR and foreign policy socialisation. The way EU health attachés embrace their diplomatic functions in Brussels speaks of a community of practice (Wenger, Citation1998) of health attachés that is recognisable through channels of socialisation (Juncos & Pomorska, Citation2006), with patterns of distinct social activities deemed important (Bicchi, Citation2016). One of the socially meaningful practice that we observed among the community of EU health attachés is that it fosters diplomatic cooperation during COVID-19. Based on their daily interactions they are driven by the political commitment to cooperate and find solutions, which results from their roles as representors and advisers, and negotiators of draft legislation, but also from their affiliation with the Brussels environment. By exploring the details of everyday practices of EU health attachés we zoom in on the practice of diplomacy specifically. As scholars pointed out, diplomats “go native” (Berridge, Citation2010, p. 107), by identifying with their host country, which creates tension with their home base but also promotes, in this case, rapprochement in Brussels (Ławniczak, Citation2018). Despite this, knowledge-sharing is an essential diplomatic practice shared by diplomatic communities worldwide (Baltag, Citation2018; Bicchi, Citation2016) and EU health attachés’ embrace such a practice. This is especially visible as the general function of gathering and providing information in a one-way street to the own capital evolved into multi-directional information sharing during the pandemic.

Though embracing a single-case study research design allowed to explore health attachés’ role in depth, it becomes challenging to make generalisations. The sui generis nature of EU diplomacy, where diplomatic practices are largely based on negotiating EU legislation, makes extrapolating outcomes beyond the EU-setting a difficult undertaking. Whereas this is true when we talk about the patterns of interaction that emerge from the embedding of health attachés in the legislative machinery of the Council, the roles identified here serve as point of departure for further research on health attachés and EU diplomacy. In this sense there are several avenues for developing such a research agenda. Future research could, for example, corroborate and/or (in)validate our findings through single case-studies focusing on specific EU Member States. Moreover, scholarly research can undertake comparative investigation, e.g. comparing the role of health attachés at different levels of diplomacy (bilateral vs. multilateral), in different regions (EU vs. other regional entities such as the African Union), in different organisations (EU vs. WHO), or make a comparison over time, delving deeper into the question “where have all the health attachés gone?” and contrasting the diplomatic practices of health attachés today with those of the past to further track continuity and change in the wide-ranging field of diplomacy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sabrina Luh

Sabrina Luh is holding a MSc double degree in Public Policy and Human Development from Maastricht University and United Nations University. With a background in European Studies, her research affinity lies in EU diplomacy and public policy, complemented by an interest in foreign policy, security, and human rights topics. The findings presented in this article rely on the research conducted for her Master thesis “Global Health Diplomacy in Times of Crisis: An Assessment of European Diplomatic Cooperation and the Role of Health Attachés”, evaluated with cum laude.

Dorina Baltag

Dorina Baltag holds a PhD degree in EU Diplomacy and Foreign Policy from Loughborough University. She is currently a post-doctoral researcher at the Institute for Diplomacy and International Governance at Loughborough University (London campus) where she was awarded the Excellence 100 Fellowship. Her research deals with questions related to the practice of EU diplomacy in Eastern Partnership (EaP) countries, the democratization process in the EaP and the evaluation of EU foreign policy performance. She contributed, inter alia, to Democratization, the Hague Journal of Diplomacy, the “Routledge Handbook on the ENP” (Routledge, Oxford) and the “External Governance as Security Community Building” (Palgrave, London).

Notes

1 Old Member States: The six founding members: Germany, France, Italy, Belgium, Luxembourg, and The Netherlands (1957), and new Member States: Denmark, Ireland, and the UK (1973); Greece (1981); Spain and Portugal (1986); Austria, Finland, and Sweden (1995), Czech Republic, Estonia, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Malta, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia (2004), Romania and Bulgaria (2007), and Croatia (2013). Since 2020, the UK is no longer a member of the EU.

2 Western Europe: Germany, The Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Austria, France; Southern Europe: Portugal, Spain, Italy, Malta, Croatia, Slovenia; Greece; Cyprus; Eastern Europe: Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria; Northern Europe: Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Ireland (World Atlas, Citationn.d.).

3 The EU witnessed the rise of Eurosceptic and/or populist parties in its MS, representing dissatisfied and even hostile constituencies towards EU engagement, e.g., Jobbik, and the Law and Justice Parties in Hungary and Poland (Lázár, Citation2015). In contrast, Germany and France are spearheading European integration efforts.

4 Health attachés interviewed for this research project work for the PermReps of Germany, Estonia, Hungary, France, Belgium, Spain, The Netherlands, Luxembourg, Denmark, and Bulgaria in Brussels. Participating countries are enumerated in mixed order to secure interviewees’ anonymity.

5 The Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (Gavi), also referred to as ‘the Vaccine Alliance’ was founded in 2000 and functions as a PPP geared towards the equitable access to vaccines. Partnering with the WHO, UNICEF, the World Bank, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Gavi supports the scale-up of national vaccination programmes, the introduction of new vaccines and the sustainable financing of vaccination campaigns (Gavi, Citation2020).

6 As a result of the inability of South African institutions to provide enough graduates (South Africa Department of Health, Citation2015).

7 The remaining are: General Affairs; Foreign Affairs; Economic and Financial Affairs; Justice and Home Affairs; Competitiveness (Internal Market, Industry, Research and Space); Transport, Telecommunications and Energy; Agriculture and Fisheries; Environment; Education, Youth, Culture and Sport (EUR-Lex, Citationn.d.a).

8 The term ‘career diplomat’ is used contrary to people from other employment backgrounds than foreign affairs, i.e., they have not been on a diplomatic college, who may however also be seconded by an official government as de facto and de jure diplomats, meaning that they enjoy the same status as career diplomats (e.g., Weinberg, Citation2014)

9 The number of votes needed in the Council to pass a decision. To achieve a qualified majority, 55 percent of EU Member States must vote in favour, representing at least 65 percent of the total EU population (EUR-Lex, Citationn.d.b).

10 HTA was on health attachés’ agenda for seven Presidencies (Bulgaria 2018 – Portugal 2021) and is to harmonise clinical assessment and scientific consultations to improve European patient’s access to health technologies. The presidency submitted the outcome of the negotiation to COREPER I for approval, which is to be followed, in the best-case scenario, by adoption by the EPSCO Council and the EP (Council of the EU, Citationn.d.a).

11 The Health Union Package consists of set of proposals to consolidate the EU’s health security infrastructure and to strengthen the role of important EU agencies in crisis planning and response. This includes Regulations on serious cross-border health threats; the re-enforcement of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control as well as the European Medicine’s Agency; and a blueprint for a future institution: the Health Emergency Response Authority (HERA) to be proposed at the end of 2021 (European Commission, Citation2020).

12 OLP: used as the decision-making procedure for the adoption of most EU legislation, where the EP and Council act as the main legislators. A proposal is submitted by the Commission, which will be either adopted or amended by the co-legislators. If EP and Council cannot agree on the suggested revisions, both parties can amend it again. If they still are unable to find an agreement, they enter negotiations. Once these have been completed, both EP and Council can either vote for or against it (European Parliament, Citationn.d.). For a step-by-step overview of the OLP.

13 Trialogues are informal meetings attended by representatives from the EP, the Council, and the Commission possible anytime during the legislative process with the goal of reaching informal agreements on legislative proposals.

14 Every six months, the Council Presidency rotates among EU member states. During this six-month period, the Presidency chairs sessions at all levels of the Council and represents the Council in relations with the other EU institutions, particularly with the Commission and the EP. Its role is to try and reach agreement on legislative files ensuring that the EU’s work is not disrupted (Council of the EU, Citationn.d.a).

References

- Adams, V., Novotny, T., & Leslie, H. (2008). Global health diplomacy. Medical Anthropology, 27(4), 315–323. doi:10.1080/01459740802427067

- Al Bayaa, A. (2020). Global health diplomacy and the security of nations beyond COVID-19. e-International Relations. https://www.e-ir.info/2020/05/22/global-health-diplomacy-and-the-security-of-nations-beyond-covid-19/.

- Almeida, C. (2020). Global health diplomacy: A theoretical and analytical review. Oxford Research Encyclopedias. https://oxfordre.com/publichealth/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190632366.001.0001/acrefore-9780190632366-e-25.

- Aluttis, C., Krafft, T., & Brand, H. (2014). Global health in the European Union – A review from an agenda-setting perspective. Global Health Action, 7(1), 1–6.

- Amadio Viceré, M. G., Tercovich, G., & Carta, C. (2020). The post-Lisbon high representatives: An introduction. European Security, 29(3), 259–274. doi:10.1080/09662839.2020.1798409

- Baltag, D. (2018). EU external representation post-Lisbon: The performance of EU diplomacy in Belarus. Moldova and Ukraine. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 13(1), 75–96. doi:10.1163/1871191X-13010035

- Bergner, S., Pas, R. V. D., Schaik, L. G. V., & Voss, M. (2020). Upholding the World Health Organization: Next steps for the EU. Berlin: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik - SWP - Deutsches Institut für Internationale Politik und Sicherheit.

- Berridge, G. (2020, May). Where have all the health attachés gone? Diplo Foundation.https://grberridge.diplomacy.edu/where-have-all-the-health-attachés-gone/.

- Berridge, G. R. (2010). Public diplomacy. In G. R. Berridge (Eds.). Diplomacy: Theory and practice (pp. 179–191). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bicchi, F. (2016). Europe under occupation: The European diplomatic community of practice in the Jerusalem area. European Security, 25(4), 461–477. doi:10.1080/09662839.2016.1237942

- Blair, A. (2001). Permanent Representations to the European Union. Diplomacy and Statecraft, 12(3), 139–158. doi:10.1080/09592290108406217

- Brown, M. D. (2016). Applied health diplomacy: Advancing the science, practice, and tradecraft of global health diplomacy to facilitate more effective global health action (Doctoral dissertation, University of California, San Diego).

- Brown, M. D., Bergmann, J. N., Novotny, T. E., & Mackey, T. K. (2018). Applied global health diplomacy: Profile of health diplomats accredited to the United States and foreign governments. Globalization and Health, 14(1), 1–11. doi:10.1186/s12992-017-0316-7

- Brown, M. D., Mackey, T. K., Shapiro, C. N., Kolker, J., & Novotny, T. E. (2014). Bridging public health and foreign affairs: The tradecraft of global health diplomacy and the role of health attachés. Science & Diplomacy, 3(3), 1–12.

- The Brussels Time. (2019, October). Belgium health attaché hired to help lift Chinese embargoes on beef, pork, and poultry. The Brussels Time. https://www.brusselstimes.com/news/belgium-all-news/74944/belgium-health-attaché-hired-to-help-lift-chinese-embargoes-on-beef-pork-and-poultry/.

- Buonanno, L., & Nugent, N. (2013). Policies and policy processes of the European Union. Basingstoke, Hampshire England: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Chattu, V. K., & Chami, G. (2020). Global health diplomacy amid the covid-19 pandemic: A strategic opportunity for improving health, peace, and well-being in the CARICOM region – a systematic review. Social Sciences, 9(5), 88–16. doi:10.3390/socsci9050088

- Council of the European Union. (n.d.a). EU health policy. European Council, Council of the European Union. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/eu-health-policy/.

- EUR-Lex. (n.d.a). Glossary of summaries. Council of the European Union. EUR-Lex Access to European Union law. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/summary/glossary/eu_council.html.

- EUR-Lex. (n.d.b). Glossary of summaries. Qualified majority. EUR-Lex Access to European Union law. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/summary/glossary/qualified_majority.html.

- European Commission. (2020). Building a European Health Union: Stronger crisis preparedness and response for Europe. European Commission Press Corner. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_2041.

- European Parliament. (n.d.). Overview: The ordinary legislative procedure. European Commission. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/olp/en/ordinary-legislative-procedure/overview.

- Gebhard, C. (2017). The problem of coherence in the EU’s international relations. In C. Hill, M. Smith, & S. Vanhoonacker (Eds.), International relations and the European Union (pp. 123–142). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Global Alliance for Vaccination and Immunization (Gavi). (2020). About our Alliance. Gavi. https://www.gavi.org/our-alliance/about.

- Guterres. (2020, March). Transcript of UN Secretary-General’s virtual press encounter to launch the Report on the Socio-Economic Impacts of COVID-19. United Nations. https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/press-encounter/2020-03-31/transcript-of-un-secretary-general’s-virtual-press-encounter-launch-the-report-the-socio-economic-impacts-of-covid-19.

- Hayes-Renshaw, F. (2017). The Council of ministers. Basingstoke, Hampshire, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hofius, M. (2016). Community at the border or the boundaries of community? The case of EU field diplomats. Review of International Studies, 42(5), 939–967. doi:10.1017/S0260210516000085

- Juncos, A. E., & Pomorska, K. (2006). Playing the Brussels game: Strategic socialisation in the CFSP Council working groups. European Integration Online Papers (EIoP), 10(11), 1–18.

- Katz, R., Kornblet, S., Grace, A., Lief, E., & Fischer, J. (2011). Defining health diplomacy: Changing demands in the era of globalization. The Milbank Quarterly, 89(3), 503–523. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00637.x

- Kickbusch, I., & Franz, C. (2020). <Towards a synergistic global health strategy in the EU. The Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Global Health Centre.

- Kickbusch, I., Nikogosian, H., Kazatchkine, M., & Kökény, M. (2021). A guide to global health diplomacy. Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies. Geneva: Global Health Centre.

- Kirton, J., & Guebert, J. (2009). Looking to the environment for lessons for global health diplomacy. Study Prepared for the World Health Organization, May 31, 1–38.

- Koenig, N., & Stahl, A. (2020). How the coronavirus pandemic affects the EU’s geopolitical agenda. Jacques Delors Centre. https://www.hertie-school.org/fileadmin/20200424_EU_Solidarity_Koenig_Stahl.pdf.

- Lázár, N. (2015). Euroscepticism in Hungary and Poland: A comparative analysis of jobbik and the Law and justice parties. Politeja-Pismo Wydziału Studiów Międzynarodowych i Politycznych Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego, 12(33), 215–233.

- Ławniczak, K. (2018). Socialisation and legitimacy intermediation in the Council of the European Union. Perspectives on Federalism, 10(1), 202–221. doi:10.2478/pof-2018-0010

- Maurer, H., & Wright, N. (2020). A new paradigm for EU diplomacy? EU Council negotiations in a time of physical restrictions. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 15(4), 556–568. doi:10.1163/1871191X-BJA10039

- Ruckert, A., Labonté, R., Lencucha, R., Runnels, V., & Gagnon, M. (2016). Global health diplomacy: A critical review of the literature. Social Science & Medicine, 155, 61–72. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.03.004

- South Africa Department of Health. (2015, April). Department of health on its strategic and annual performance plan. Parliamentary Monitoring Group. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/20686/.

- Steunenberg, B. (2010). Is big brother watching? Commission oversight of the national implementation of EU directives. European Union Politics, 11(3), 359–380. doi:10.1177/1465116510369395

- Steurs, L., van de Pas, R., Decoster, K., Delputte, S., & Orbie, J. (2017). Role of the European Union in global health. The Lancet Global Health, 5(8), e756. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30212-7

- US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). (2021, January). Global health diplomacy. HHS https://www.hhs.gov/about/agencies/oga/global-health-diplomacy/index.html.

- Weinberg, A. (2014). Career diplomats worried about influx of political appointees at State Department. abcNews. https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/career-diplomats-worried-influx-political-appointees-state-department/story?id=26605856.

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

- World Atlas. (n.d.). Regions of Europe. WorldAtlas. https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-four-european-regions-as-defined-by-the-united-nations-geoscheme-for-europe.html.

- Wuropulos, K. (2020). Emotions, emergencies and disasters: Sociological and anthropological perspectives on the COVID-19 pandemic. Global Affairs, 6(4-5), 609–615. doi:10.1080/23340460.2020.1846997