ABSTRACT

Ecological crisis, massive inequality and war: our world is at a dangerous tipping point. Yet the present global crisis defies simple description and is difficult to explain. To clarify, it is argued that the character of the world crisis today is triple: ecological, economic and political. Underlying all three dimensions is the capitalist form of world society. The consolidation of this capitalist form was accompanied by the emergence of the concept of development within liberal philosophy. During the 20th century, development came to define geographical regions and legitimate capitalist political economy on a world scale. Capitalism came to be taken as development: I call this ‘capitalism qua development’. Because of the triple crisis, capitalism qua development is beginning to undergo a profound change. In an era of rapid global heating and ecological crisis, the tie between capital and development is straining and likely to give way. Capital is becoming more closely attached to the concept of adaptation. I argue that, in the most likely scenario (‘Climate Leviathan’), capitalism qua development will be recast as adaptation. Some signs of this shift are already apparent. Since this is only a likely prospect, three other possibilities – fates of the concept and practice of development – are proposed.

摘要

全球危机时代的资本主义即发展 Area Development and Policy. 生态危机、严重不平等和战争:我们的世界正处于危险的临界点。然而,当前的全球危机无法简单描述,也难以解释。为了阐明这一点,我们认为当今世界危机的特点是三重的:生态、经济和政治。这三个方面的基础是国际社会的资本主义形式。伴随着这种资本主义形式的巩固,自由主义哲学中出现了发展的概念。20 世纪,发展开始在世界范围内界定地理区域并使资本主义政治经济合法化。资本主义开始被视为发展: 我称之为 “资本主义即发展“。由于三重危机,资本主义即发展开始发生深刻变化。在全球急剧升温和生态危机的时代,资本与发展之间的纽带正在绷紧,并有可能破裂。资本与适应这一概念的联系越来越紧密。我认为,在最有可能发生的情况下(“气候利维坦”),资本主义即发展将被重塑为适应。这种转变的一些迹象已经显现。由于这只是一种可能的前景,因此我提出了发展概念和发展实践的命运的另外三种可能性。

Resumen

Capitalismo como desarrollo en una era de crisis planetaria. Area Development and Policy. Crisis ecológica, enormes desigualdades y guerra: nuestro mundo está en un peligroso punto de inflexión. Sin embargo, la crisis actual en el mundo es difícil de describir y explicar. A manera de clarificación, se argumenta que el carácter de la crisis mundial de hoy día es triple: ecológico, económico y político. La forma capitalista de la sociedad mundial se enmarca en estas tres dimensiones fundamentales. La consolidación de esta forma capitalista iba unida a la emergencia del concepto de desarrollo dentro de la filosofía liberal. Durante el siglo XX, el desarrollo capitalizó la definición de las regiones geográficas y legitimó la economía de la política capitalista a escala mundial. El capitalismo se adoptó como una forma de desarrollo: A esto le llamo ‘capitalismo como desarrollo’. Debido a la triple crisis, el capitalismo como desarrollo está empezando a experimentar un profundo cambio. En una era de rápido calentamiento global y crisis ecológica, el vínculo entre capital y desarrollo está bajo presión y es propenso a ceder. El capital se está acercando cada vez más al concepto de adaptación. Argumento que, en el escenario más probable (‘Leviatán Climático’), el capitalismo como desarrollo se transformará en adaptación. Algunos indicios de este cambio ya son evidentes. Dado que esto es solamente una perspectiva probable, aquí se proponen otras tres posibilidades, destinos del concepto y de la práctica de desarrollo.

Аннотация

Капитализм как развитие в эпоху планетарного кризиса. Area Development and Policy. Экологический кризис, массовое неравенство и война: наш мир находится на опасном переломном этапе. Тем не менее, нынешний глобальный кризис не поддается простому описанию и его трудно объяснить. Чтобы внести ясность, утверждается, что характер мирового кризиса сегодня тройственный: экологический, экономический и политический. В основе всех трех измерений лежит капиталистическая форма мирового общества. Укрепление этой капиталистической формы сопровождалось появлением концепции развития в рамках либеральной философии. В течение 20-го века развитие стало определять географические регионы и легитимизировать капиталистическую политическую экономию в мировом масштабе. Капитализм стали воспринимать как развитие: я называю это ‘капитализм как развитие”. Из-за тройного кризиса капитализм как развитие начинает претерпевать глубокие изменения. В эпоху стремительного глобального потепления и экологического кризиса связь между капиталом и развитием ослабевает и, вероятно, ослабнет. Капитал становится все более тесно связанным с концепцией адаптации. Я утверждаю, что в наиболее вероятном сценарии (“Климатический левиафан”) капитализм как развитие будет преобразован в адаптацию. Некоторые признаки этого сдвига уже очевидны. Поскольку это лишь вероятная перспектива, предлагаются три другие возможности - три судьбы концепции и практики развития.

1. OUR PRESENT CRISIS

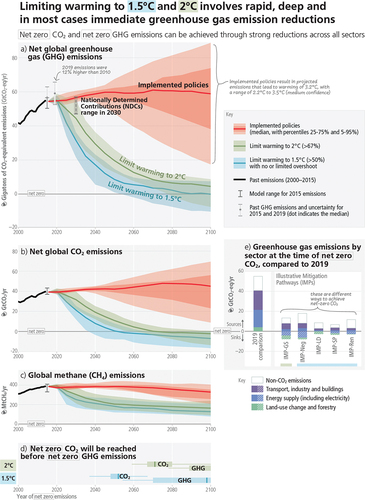

The object of this paper is to examine the nature of capitalism qua development, that is, capitalism being taken as development, amidst planetary crisis. While this analysis is principally conceptual, it rests upon some facts – three in particular. First fact: we inhabit a rapidly heating planet, beset by climate change, caused principally by the burning of fossil fuels (IPCC, Citation2021). To stop the warming we must radically reduce the burning of fossil fuels (see ); yet, each year, more are burned. Roughly half of all fossil fuels are owned by private corporations like Shell and Exxon.Footnote1 The rest are controlled by sovereign governments like Norway, Venezuela and Saudi Arabia: the world’s most profitable company is presently Aramco, part of the Saudi state. This means that the fossil fuels we must not burn are controlled by for-profit corporations or capitalist states. Neither the firms nor the states have an interest in giving up this source of power and wealth (or ‘stranding their assets’).Footnote2 Driven by competition, each of these firms and states competes with the others to increase its profit. This is because they are capitalist firms and states; capitalism is a social formation defined by the drive for accumulation. The logic of competition in capitalist society generates an inherently expansionary dynamic: to sustain profit for their individual firms or investments, individual capitalists must seek growth. Where states act through capitalist firms (explicitly in the case of Aramco, implicitly when the US government subsidises fossil fuel extraction), state power reinforces the drive of firms to maximise profit-seeking via fossil capitalism. Thanks to research in ecological Marxism (e.g., Burkett, Citation1999; Malm, Citation2016, Citation2023b; Saito, Citation2017, Citation2023), these problems are well understood. Indeed, it is no longer especially radical to draw a connection between the climate crisis and capitalism’s accumulation drive (Hudson, Citation2023; Klein, Citation2015). Nevertheless, while many have come to recognise that the fundamental cause of the climate crisis is the capitalist way of organising economic life, at a political level, fossil extraction continues to grow; the world is trapped in a system of capitalist nation-states incapable of breaking this trend. The principal victims of global heating are the poor, who are responsible for the least carbon emissions yet face the greatest challenges in a warmer world (Alvaredo et al., Citation2022). And the poor have the least political agency to confront this injustice.Footnote3

Second fact: we live at a moment of extraordinary wealth inequality. Less than 1% of humanity controls over half of all the world’s wealth; meanwhile, billions of people around the world lack adequate food, water, shelter and/or employment. This degree of inequality belies historical parallel. The driver of this wealth inequality is the accumulation of capital under competitive conditions. The extraordinary concentration of capital inhibits economic growth and reduces profitability of commodity production. The rich hoard their wealth in the form of assets, which have accordingly inflated in value, while most people in the world – who sell labour power for a wage to buy and consume commodities – earn too little to buy back enough of the commodities that are produced for accumulation to continue its expanding cycle.Footnote4 In Marxist terms, this is a crisis of value realisation (Luxemburg, Citation1913/2003), otherwise known as a period of commodity overproduction, triggered by extreme wealth concentration.

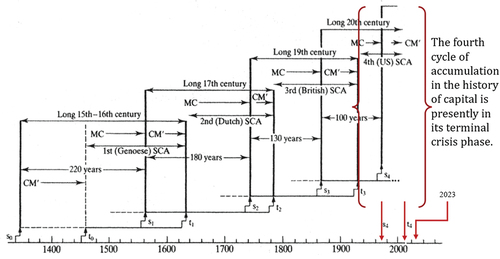

Both facts are supported by ample data. Prescient natural scientists (Fact 1) and a few Marxist political economists (Fact 2) predicted them. For the latter, consider Giovanni Arrighi’s 1994 historical analysis of the history of capitalism in The Long 20th Century (see ). If we accept the parameters of Arrighi’s analysis, humanity is presently in the terminal phase of the 4th cycle of capital accumulation. During comparable phases of each of the previous three cycles of accumulation in the history of capitalism, the political economy was highly unstable, marked by the absence of a clear, single hegemon:

Those were periods of transition, interregna, characterized by a dualism of power in high finance analogous to … the Anglo-American dualism of the 1920s and early 1930s. During [previous] periods of transition, the ability of the previous center of high finance to regulate and lead the existing world system of accumulation in a particular direction was weakened by the rise of a rival center which, in its turn, had not yet acquired the dispositions or the capabilities necessary to become the new ‘governor’ of the capitalist engine. In all these cases the dualism of power in high finance was eventually resolved by the escalation into a final climax (successively, the Thirty Years War, the Napoleonic Wars, the Second World War), of the competitive struggles that, as a rule, mark the closing (CM’) phases of systemic cycles of accumulation. … Historically, … it was not until after the confrontations had ceased that a new regime was established, and surplus capital found its way back into a new (MC) phase of material expansion.Footnote5

Figure 1. To meet the Paris goal and limit warming to 1.5–2 °C would require a rapid decrease in carbon emissions – a much deeper transition than proposed by the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Source: IPCC (Citation2023)

After World War II, the USA became the world centre of finance, production and consumption. Yet the USA has long lost its lead in high-value commodity production and its capacity to regulate finance on a world scale (cf., Arrighi, Citation1994; Dunford, Citation2021). The USA is no longer capable, therefore, of organising a Bretton Woods type of arrangement for the re-regulation of global capitalism: although many may wish otherwise, there is not yet a capable US-led green Keynesian programme to rebalance factors of production while stimulating a new, ‘sustainable’ cycle of accumulation. The world leader in solar and wind power generation is China, presently (to repeat Arrighi’s terms) the rival centre that has ‘not yet acquired the dispositions or the capabilities necessary to become the new “governor”’. Just one element from Arrighi’s historical scheme is presently missing: the catharsis of war, needed to clear out over-accumulated capital and define the new hierarchy. Yet can we not make out its prospects in the cold war between these two powers? Jeju-do to Okinawa to Taiwan and the South Pacific – the fault line of our interregna, an archipelago of potential triggers (accidental, even) of hot conflict between the USA and China.

Fact 3 is that we are living through a political or hegemonic crisis comprised of four interconnected elements:

A general decline of the hegemony of liberalism and liberal parties, generating the concomitant rise of the extreme right. (This decline is often called ‘populism’, but I find this term too vague to be useful.)

Elite social groups have experienced a decline of intra-elite agreement about legal means to resolve their conflicts over political (hegemonic) and economic (accumulation) strategies. We see this manifest when, for example, distinct factions of elites not only back different political parties (which is to be expected) but coalition building breaks down, making it impossible to form stable governments, and/or some elite factions refuse to accept the results of elections when ‘their’ parties lose (as the USA experienced after the 2020 election). When the elite of a specifically capitalist society (the bourgeoisie) cannot agree upon the norms and rules by which they clash with one another, it becomes far more difficult to maintain any coherent accumulation and/or hegemonic strategy.

For their part, subaltern groups everywhere have good reason to reject the present order, yet they lack any sort of global political movement that could unify them. When subaltern social groups do protest, their efforts tend to be sporadic and limited. Almost everywhere, their efforts are met by repression: hence growing state investment in means of repression: surveillance, police and military. As Machiavelli taught in The Prince (Machiavelli, Citation1513/2014), general repression (coercion) implies limited hegemony (consent).

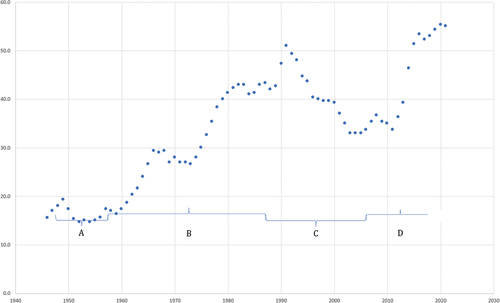

From a between-society perspective, political crisis manifests as war. After a decade when we were told that violent conflicts were consigned to the past, our world has returned to tempus belli, featuring hot (Russia versus Ukraine, for example) and cold wars (China versus USA). Look beneath these well-known cases and the pattern in striking: since about 2011, the total number of countries in conflict has increased sharply (see ).

Figure 2. The four Systemic Cycles of Accumulation (SCA) in the history of capitalism, noting our present position. Source: Arrighi (Citation1994), modified by the author. In Marx’s (Citation1867/1976) general formula for capital, M-C-M’, M is money and C is commodity. M-C is the process of producing a commodity; C-M’ is the sale of the commodity. In his history of capital, Arrighi treats these two processes as temporal phases of oscillating, systemic cycles of accumulation (see Arrighi, Citation1994 for details).

All four of these elements became qualitatively worse in the wake of the economic crisis of 2007–08. While temporal coincidence alone cannot certify a causal relationship, it is plausible to claim that the economic crisis triggered the political crisis. Such a claim becomes much stronger, in my view, when we factor in the ecological crisis as well. I claim that the coupled ecological-economic crisis is the principal driver of the political crisis. But since the political crisis rebounds back to make the ecological-economic crisis more difficult, it is more sensible to see the three elements as one differentiated unity.

1.1. The triple crisis

People around the world experience these problems and recognise these facts. It is striking, therefore, that social scientists have failed to produce a widely-accepted analysis of these symptoms and an explanation of their underlying causes. Indeed, we do not even have a widely-accepted name for the period since ca 2007–08 (the climate crisis goes back further, of course, but has gotten much worse since 2007–08 as well). After the COVID pandemic of 2020, some analysts have taken to using the term ‘polycrisis’ to refer to the multiple, wicked, systemic problems besetting world order (e.g., Homer-Dixon et al., Citation2021). Consider Adam Tooze:

Think back to 2008-2009. Vladimir Putin invaded Georgia. John McCain chose Sarah Palin as his running mate. The banks were toppling. The Doha World Trade Organization round came to grief, as did the climate talks in Copenhagen the following year. … Former European Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker, to whom we owe the currency of the term polycrisis, borrowed it in 2016 from the French theorist of complexity Edgar Morin, who first used it in the 1990s. As Morin himself insisted, it was with the ecological alert of the early 1970s that a new sense of overarching global risk entered public consciousness. So have we been living in a polycrisis all along?

Tooze’s answer to his question is instructive:

What makes the crises of the past 15 years so disorientating is that it no longer seems plausible to point to a single cause and, by implication, a single fix. Whereas in the 1980s you might still have believed that ‘the market’ would efficiently steer the economy, deliver growth, defuse contentious political issues and win the cold war, who would make the same claim today? It turns out that democracy is fragile. Sustainable development will require contentious industrial policy. And the new cold war between Beijing and Washington is only just getting going (Tooze, Citation2022).

While I appreciate the attraction to the term ‘polycrisis’ (and agree with aspects of Tooze’s assessment), I reject it. ‘Polycrisis’ is vague about two critical factors: the question of causality and the nature of its capitalist integument. As used by writers like Tooze, polycrisis evacuates the possibility of any single cause – especially, it seems, if the cause might be called ‘capitalism’.

I therefore prefer the term ‘triple crisis’.Footnote6 While the three aspects of our crises have distinct qualities, they are interlocking in ways that produce negative synergies. Thus, I think we should refer to the period of world history since ca. 2008–09 as the ‘era of the triple crisis’. (In my view, COVID compounded our difficulties, but did not alter the triple crisis in any fundamental sense.)

While any causal explanation of such complex dynamics can be criticised for oversimplification, I think we must run this risk today, for the lack of compelling, simple explanations of what is happening is both a symptom and a cause of our political problems. So, at the risk of oversimplification (and to restate the ‘facts’ with which I started), I claim:

The environmental consequences of capitalist growth are generating worsening consequences for ordinary people worldwide. In some places, the major concern is poor air quality, elsewhere water shortages or flooding or failed crops. Regardless of the specifics, no place is untouched. As a rule, subaltern social groups (the poor and socially marginalised) face the harshest consequences of ecological degradation.Footnote7

The concentration of wealth has resulted in myriad injustices as well as a stagnation of economic prospects for the masses of humanity.

Taken together, growing economic inequality and environmental crises have generated a significant increase in insecurity and anxiety, particularly since ca. 2008. The failure of elites to address this insecurity and anxiety has undermined their ideological legitimacy. The world’s subaltern social groups have lost much of whatever faith they had in bourgeois-liberal parties and state institutions, creating greater opportunities for extreme right-wing actors to seize power, further weakening liberal norms and institutions.Footnote8 Hence the political crisis.

While these three crises can be distinguished methodologically, in practice they are inseparable. For instance, the quickest way to address the climate crisis would be to stop fossil fuel extractionFootnote9 but, ceteris paribus, doing so would make capitalism’s economic crisis worse. From a left-Keynesian vantage, the way to address the economic crisis would be to enact a state-led, global-scale accumulation project; yet, ceteris paribus, the resulting expansion of commodity production would make the climate crisis much worse. Hence the desire for a green Keynesian project – some sort of global ‘Green New Deal’ (see Wainwright & Mann, Citation2018) – but the political crisis of liberalism holds the world back from such a path. The USA and China would obviously need to be at the heart of such a strategy, but they are practically at war. Pace Tooze, there is no way to begin to make sense of all this without beginning from an analysis of capitalism, for the capitalist organisation of economic life is the underlying cause.

Although capital is the fundamental matrix of the triple crisis, I hasten to add that capitalism is neither ‘single’ nor a thing, but a historical, social formation. And since there are no simple solutions to the form of a society, I agree with Tooze that there is no ‘single fix’ to the triple crisis. Yet this should not mark the end of our analysis, but rather a new beginning.

1.2. Whither development?

I share these remarks not to provide a definitive statement on the triple crisis (still less to try to find a ‘fix’ for it). My aim is more modest. The question I pursue is: given the triple crisis, what will happen to development as a concept and practice?

To answer this, I will proceed in two steps. First, I will offer a critique of development: essentially a concise recapitulation of an argument from my book Decolonising Development (Wainwright, Citation2011). Second, I will bring this critique of development to bear on the present day and our planetary crisis. This section draws upon arguments from my book Climate Leviathan, co-authored with Geoff Mann (Wainwright & Mann, Citation2018). Taken together, I will argue that the relationship between capitalism and development which dominated the past century, which I call ‘capitalism qua development’, is undergoing change because of the triple crisis. What will result is not yet clear, but I will try to sketch some possibilities. Hence this analysis is partly diagnostic, partly speculative.

2. Capitalism qua development

The English word ‘development’ bears two radically divergent meanings. The first, older meaning is the becoming of something. The verb ‘to develop’, from which the noun ‘development’ is derived, has Latin roots that carry the connotation of ‘disentangling’.Footnote10 ‘Development’ thus refers to an ontological quality whereby what is essential to something is expressed not at any given state, but through an entire process of becoming. Although the word is not as old as the Greeks, this idea has its roots in Aristotle’s conception of nature as becoming. Consider Book IV of Physics (Aristotle, Citation2001, p. 238):

What grows qua growing grows from something into something. Into what then does it grow? Not into that from which it arose but into that to which it tends. The shape is then nature.

If we ask, for instance, when or how an oak tree expresses its being, we could point to an acorn, but this would only symbolise its potential becoming; a tree producing the same seeds would reflect its being at maturation; a tree in senescence metabolises into non-being. Each of these moments truthfully reflects the very nature or being of the tree. It follows, then, that the essence of the tree is not in any of these moments – and no hierarchy can be determined between them. Rather, it would be better to say that the essence of the tree is expressed in the totality of its unfolding. In Aristotle’s texts, this thought became organised through the metaphysics of physus, a manner of conceiving being that would become much later expressed as ‘nature’. Now, ‘nature’ holds a range of meanings in European languages. One of those meanings expresses that ancient ontological sense of being as becoming, where the essence of a thing is expressed in the totality of its unfolding. This is the ancient origin of what today we call development – as understood in its ontological sense.

The modern usage of development entered Western philosophy via Hegel, who uses ‘development’ (Entwicklung) in the ontological sense. For instance, in the Introduction to his Lectures on the History of Philosophy (Hegel, Citation1805/1985–6), Hegel defines three elements that are fundamental to conceiving a history of philosophy: thought, concept and idea. ‘Development’ characterises the movement between them. ‘The Idea as development must first make itself into what it is. For the Understanding, this seems to be a contradiction, but the essence of philosophy consists precisely in resolving the contradictions of the Understanding’ (p. 71). This gives rise to the distinction between potential and existence. (As with Aristotle, the seed is again the metaphor for the former.) Hegel takes one step beyond Aristotle, however, by writing of development as the self-unfolding of life towards the divine or of ‘the divine in the world’.Footnote11 In effect, Hegel transposed the ontological sense of development into a Christian register. Curiously, he did so when development first began to be used by thinkers in Western Europe to articulate a liberal response to the changes wrought to their societies by capitalist social relations. Before elaborating, we need to clarify a second meaning of the modern use of ‘development’.

Quite apart from the older, ontological, meaning, ‘development’ also refers to an intention to change something.Footnote12 In this sense, ‘development’ refers to a force that transforms a thing. This second meaning always carries the sense of will: development in this second sense implies an external intervention – to make something move in a direction that is not given in advance, essential or required. The object of development is changed or improved by some wilful power applied by some external agent.

Many words have multiple connotations. What is unusual about these two meanings of ‘development’ is that they are utterly orthogonal from one another, bearing strikingly distinct implications – a difference that is commonly elided in the ordinary use of the word. To bring out the weirdness of their conjuncture in one word, we need only consider that by the first meaning, develop occurs naturally, in the simple fact of the expression of the essence of a thing. A seed naturally grows to become a tree: something is what it is, becoming itself at each moment in time. To put development in this ontological sense formulaically: beings develop = being becoming. By contrast, in the second (ontic) sense, a place, person or thing undergoes development because something else changes it. Here the formula is: the agent of development develops (changes) the object of development. A developer develops a site; a firm develops a resource; a development loan develops a region: however the formula is solved, the result is that things are not what they were. In sum, in the first instance, development refers to an inherent or immanent process; in the second, an externally driven change.

These two radically distinct meanings of development are conflated in ways that have important effects. Whenever we refer to ‘national development’ or ‘economic development’, we refer to a process that is inherent and natural (per the first meaning) but also that requires wilful intervention by some external agent or authority (per the second). This conflation is not due to a choice made by the speaker. It is an effect of language – and one of great significance, since today, every strategy of economic development in fact generates the deepening of capitalist social relations, even when this goal is not stated.Footnote13

Capitalism emerged as a social formation in the 17th and 18th centuries. In the process, capitalism stimulated dynamic new social processes, such as advances in scientific research, transport networks and commodity production; it also caused harmful consequences, like industrial pollution, labour exploitation and imperial war. During the late 18th and early 19th century, liberal thinkers in Europe generated new ways of discussing these changes. They sought language with which to affirm the new capitalist organisation of society that left open the possibility of criticising the negative social and environmental consequences it generated. One consequence of this process was that the changes wrought by capitalism (a word that was not widely used until the late 19th century) came to be described as ‘development’. This cannot be seen as accidental or capricious, since, for European liberals, what was needed was development: the cultivation of a better (capitalist) society. This allowed for the simultaneous affirmation of capital and the critique of attendant social and environmental problems. This formula has remained potent to the present. Still, when liberals criticise the environmental crisis, they do not call for ecological socialism, but ‘sustainable development’ (as we saw above in the quote from Tooze). When they criticise the extraordinary political or economic inequalities of our time, they do not proclaim revolutionary democracy, but social and economic development. In doing so, contemporary liberals recapitulate language of two centuries vintage. But the grapes that produce this wine grow from ancient soil, for the underlying conception of development still bears the sense of inherent, natural becoming we saw in Aristotle. This affiliation between capitalism and the compound sign ‘development’ has a crucial consequence: the deepening of capitalist social relations everywhere is inscribed with an undeserved sense of naturalness and direction. Whenever capitalism is treated as development, the violent effects of capitalist social relations are naturalised.

2.1. So-called ‘original accumulation’ and the emergence of development

Although Western European societies were the first where discernibly capitalist social relations became generalised, the process driving this change (the ‘becoming of capital’) was world-encompassing. The colonisation of the Americas played a fundamental role in the economic transformation of Holland, England and France. The dominant classes in these colonial-capitalist societies benefitted from the plundering of indigenous lands and enslavement of human labourers, generating surpluses that helped stimulate the emergence of a capitalist bourgeoisie in England. No less importantly for the emergence of capital, the competition between European powers to dominate valuable trade routes, passage points and productive lands generated positive feedback between the cultivation of means of making war (armies, weaponry, territory) and accumulation of new means of capitalist production (labour, material, land). Adam Smith rued the formation of this vicious cycle, calling it the ‘unnatural path of development’ (Arrighi, Citation2007). Capitalist social relations were consolidated along Smith’s unnatural path – first in England. Once established there, capital globalised. Capitalism has now encircled the globe, but the process continues through the intensification and deepening of distinctly capitalist social relations.Footnote14

The subsequent emergence of capitalist social relations in Latin America, Asia and Africa was not an uncomplicated process. To generalise – processes differed by geographical region and historical period – the emergence of capitalism was brought about through colonialism, war and the separation of people (labour) from the land (means of production). This was first explained by Marx in Capital I through his critique of ‘the so-called original accumulation’, a concept that Marx adopted with modification from Adam Smith. For Smith (Smith, Citation1776/1982), the ‘original accumulation’ that sets market society going is that stock of initial capital an owner of capital uses to initiate production. In Smith’s account of the origin of market society, the owners of capital in Britain had originally accumulated this capital through thrift and savings. Yet Smith provides no historical evidence for this view. For Marx, original accumulation is a class process, the separation of the labourer from the means of production.

So-called original accumulation is … nothing other than the historical process of separating the producers from the means of production. It presents itself as ‘original’ because it constitutes the prehistory of both capital and the mode of production that goes with capital (Marx, Citation1867/1976).

As Marx emphasises, this process – the becoming of capital – can play out in varied ways. Nevertheless, the result is to make people worldwide ever more dependent upon selling labour power as a commodity. This dependence results from the separation of people from the collectively owned means of production (as found in many peasant communities before their incorporation into capitalist economy, for instance). As pre-existing economic forms have been reshaped, de-formed and homogenised as specifically capitalist social relations, the diversity of the economic relationships found around the world prior to the 19th century has declined dramatically. This process has been driven in part by consumer demand for cheap commodities (as economics teaches) but also by violence and coercive state power (as economics tends not to teach). Rosa Luxemburg elaborated in The Accumulation of Capital:

Capitalism must therefore always and everywhere fight a battle of annihilation against every historical form of natural economy that it encounters, whether this is slave economy, feudalism, primitive communism, or patriarchal peasant economy. The principal methods in this struggle are political force (revolution, war), oppressive taxation by the state, and cheap goods (Luxemburg, Citation1913/2003).

The political crisis of our time is experienced by subaltern social groups as some combination of these same ‘principal methods in this struggle’.

2.2. If capitalism is so bad, why did it win out?

Given all the attendant violence, how could the rule of capital ever have become justified and legitimated? This was a question that preoccupied me twenty years ago when I was writing Decolonising Development (Wainwright, Citation2003). There I argued that the achievement of bourgeois hegemony in peripheral capitalist societies of Asia, Africa and Latin America called for the concept and practice of development. The use of the term began to circulate in the 19th century, and by around the early 20th century, the concept of development took hold as a supplement to capital (and, after 1917, as a counterweight to Bolshevik revolution and Lenin’s critique of imperialism).

With development, European liberalism produced a concept that affirmed the capitalist form of society while acknowledging (and addressing, in a fashion) the exploitation of labour and the degradation of nature.Footnote15 However, since exploitation is inherent to the capital-labour relation, and degradation of the natural environment is inherent to the expanded reproduction of capital, capital cannot prevent these outcomes; but through development, it can manage them to a degree. Part of this management process is economic: development projects can help to overcome barriers to expanded reproduction. But it is also ideological: as development, capital promises positive change despite inequality and degradation. Development is both a concrete set of practices and an ideological supplement to capital. The effective congruence of these roles explains the hegemony of what I call capitalism qua development. In Decolonising Development, I argued:

The theoretical difficulty for us is that development consequently became, not dialectically but aporetically, both inside and outside of capitalism. Development, again, is capitalism; yet it also exceeds capitalism and names a surplus necessary to the correction of mere capitalism. … My answer to this challenge is to propose the concept of capitalism qua development. The sublime absorption of capitalism into the concept of development has created the effect that capitalism is development. … Consequently it was only development—not civilization, not modernity, not progress—that was universally taken up after the end of colonialism to define and organize the nation-state-capital triad everywhere (Wainwright, Citation2011).Footnote16

For around a century – from the early 20th century until 2008 – development enjoyed a relatively stable position as a supplement to capital. The world map was redrawn: Latin America, Asia and Africa became developing areas while the capitalist core produced development plans, development loans and development studies.Footnote17 We can speak, therefore, of a ‘long century of capitalism qua development’. How much longer will it last? My short answer is that it depends upon the capitalist state’s response to the triple crisis – particularly two capitalist states, the USA and China.

3. From development to adaptation

The IPCC AR6 synthesis report (IPCC, Citation2023) includes a graph that summarises the challenge we face (see ). To meet the Paris Agreement’s target – not more than 1.5 °C mean global temperature increase – the world must sharply decrease global carbon emissions immediately.

Figure 3. Number of countries in the world in conflict, 1946–2021 (three year rolling average).Data from UCDP (Citation2022); Figure by author. A corresponds to a brief period of stability after World War II; B to the rise in conflicts during the Cold War and anticolonial period; C to the brief period of renewed US hegemony after the fall of the USSR; D to the era of the triple crisis. I thank Marwan Safar Jalani and IRC for assistance with the Figure.

But doing so would require building a global counterpower that could remove the ability of the owners of fossil fuels to use their power and assets – and, on the consumption side, the ability of the wealthy to use those fuels. To say the least, we lack this counterpower today, which is why many sober analysts have already declared that we are going to miss the 1.5 °C target. At best, without geoengineering the planet, we can expect 2.0–2.5 °C increase in global mean temperature, with much greater increases at high latitudes. This would be a disaster for humanity and the other species with which we share Earth.

In Climate Leviathan, Geoff Mann and I sought to contribute to the literature on ecological Marxism by shifting our focus to our political prospects given rapid global warming. Our basic claim is the coming environmental crisis will change the underlying political arrangements of our world. It follows that only a theory that examines capitalism and sovereignty can orient us towards the coming struggles. If we are to become capable of enacting revolutionary climate justice, we need a stronger conception of that politics, and that world, for which we act. Working from a set of basic presuppositions about the organisation of politics and economic life in capitalist societies, we offer a speculative analysis of four potential future paths for humanity. These paths are defined by two basic conditions: on one hand, whether economic life will remain defined by capital and value form or be transcended into something like socialism or communism; on the other, whether the existing form of the political will be transcended to generate planetary sovereignty, or not (see ). The most likely scenario, in our view, is that the world will remain capitalist – indeed it is becoming more fully capitalist every year – and that the form of political sovereignty will adapt to become planetary. We call this path ‘Climate Leviathan’ (in homage to Hobbes); hence the title of our book.Footnote18

Figure 4. Four potential future pathways. From Wainwright and Mann (Citation2018), Climate Leviathan.

Here, I would like to add to our analysis in Climate Leviathan by addressing one question that we did not clearly answer in the book: what would be the fate of the concept of development in each of these four paths?

3.1. The end of the long century of capitalism qua development

I contend that the triple crisis threatens to end what I will call the ‘long century of capitalism qua development’. Simply put, the ability of development to supplement capital – to provide it with an effective hegemony – is wavering and seriously in doubt. But this does not mean that development is done for. Rather, I contend that if the Leviathan scenario remains the leading one, capitalism qua development will play a renewed but revised role. Of what sort?

In the Climate Leviathan scenario, capitalism qua development would become equivalent to adaptation. Loans that previously would be demarcated for economic development will be granted to facilitate adaptation to climate change. Programmes that previously would have been organised for social development will be intended to help people adapt to new environmental conditions. The accent will shift from economic growth to human survival. This change, should it in fact occur, will be motivated and directed by capital’s drive for expanded accumulation, characterised by Marx’s general formula for capital, M–C-M’. If the West retains its hegemony (which is by no means assured), the emergence of capitalism qua development as adaptation would come into existence through the actions of well-meaning liberals who sincerely wish to help the poor. Their agency, restricted by the structural power of the capitalist state and the limitations of their ideology, will bring into being an era of development where adaptation legitimates capital.

Admittedly, this is an abstract and unprovable hypothesis. Nevertheless, I contend that my claim is consistent with the logic inherent to capitalist society and that we can already begin to see this logic unfolding in our world. Consider again the central talking point of the new IPCC AR6 synthesis report, released in April 2023: the IPCC’s argument is that ‘the way forward’ is ‘climate-resilient development’, specifically by ‘integrating measures to adapt to climate change with actions to reduce emissions in ways that provide wide benefits’. The key words, I emphasise, are ‘development’ and ‘to adapt’. By this narrative, capitalism qua development has become capitalism qua development to adapt. By this reasoning, in the face of the triple crisis, capital qua development is still presented as the way forward – now as adaptation.Footnote19

3.2. On adaptation

To be fair, it is understandable and logical to say that ‘humans must adapt’ to a changing environment. That is, after all, what all species do all the time. It is logical for those liberals who genuinely want to reduce the suffering of the poor to cry out for strategies that aim for successful ‘adaptation’. And we need to retain the ability to use the concept so that we can write things like this statement (plucked at random from IPCC (Citation2023, p. 8)): ‘Current global financial flows for adaptation are insufficient for, and constrain implementation of, adaptation options, especially in developing countries’. Translated into common language, this says that rich people are not giving enough money to poor people to allow the poor to adapt to environmental damage caused by the rich.

Nevertheless, two things should give us pause. First, note that – like the absorption of capitalism into the compound sign ‘development’ in the 19th century – the contemporary appeals for ‘adaptation options’ practically never spell out the underlying, implicit commitment to the capitalist form of society. To get a sense of the weirdness of this, try to say these words: ‘we need to help poor people adapt to a capitalist world that is burning up (self-destructing)’. We can twist and turn those words around, but they accurately capture, I fear, a great deal of what passes for liberal politics on climate change today. This brings up a second reason for concern. The word ‘adaptation’ is used metaphorically – adapted – from Biology. The application of biological metaphors to social problems has a long and dreadful history, which generally teaches us that whenever elites come to speak about non-elites as biological creatures, poor people are going to suffer or die.

Applying the metaphor of adaptation – with its roots in Charles Darwin’s writings on evolution – to the task we face with the triple crisis is inadequate to explain our crisis and a poor guide for what we must do. To be sure, the concept of adaptation has an honourable history. One of Darwin’s accomplishments was to explain that no species was a fixed thing but only the capricious and temporary result of ongoing evolutionary processes. In The Origin of Species (Darwin, Citation1859/1963), Darwin showed that adaptation was inherent to and ceaseless for all life. In this view, the fact that humans are adapting to a changing climate is nothing new. Yet, as often occurs, the shift of a concept from a biological to a social register has introduced novel complications.

Recall that, for Darwin, what adapts are populations of a given species; today, however, we often hear calls for adaptation applied to nations, cities or specific social groups (for example, indigenous people and racialised minorities), which should trouble us. In a world divided by myriad forms of discrimination, calls for capitalism as adaptation are not only inadequate (since they will not generate mass action and just solutions); they are in fact likely to produce new injustices. Talk of climate adaptation also contributes to an illusion that the coming changes are readily manageable within the prevailing liberal capitalist order – they are not. Hence, if we are going to bring about a just response to climate change, we need a stronger call to arms than ‘We must development, we must adapt! It is the only way forward … ’. From the vantage of the two main political blocks in the capitalist world, most conservatives reject the IPCC’s call for development as adaptation (with its attendant green Keynesianism); by contrast, liberals seem certain to embrace it as the only possible ‘solution’ to the present crisis. But what about those on the left?

Leftists face a paradox. We must reject capitalism qua development as adaptation as an alibi for the deepening of capitalism, which in turn drives the triple crisis. However, we are also painfully aware of our temporal constraints: the climate crisis is occurring today, and we do not have at hand a global revolutionary movement to replace capitalism. It is as if Leviathan presents us with blackmail: either accept capitalism qua development as adaptation, or suffer something worse.

There is a deeper aspect of the paradox: to achieve capital as adaptation is not possible in the current political-economic order, neither in terms of practice nor ideology. In terms of policy, massive inequalities of wealth and power simply block the social and economic transformation necessary to realise what the IPCC is implicitly calling for. On the production side, fossil fuels are owned by firms and states that have refused to voluntarily surrender the source of their wealth and power. And as Gabor (Citation2021) observes, in the prevailing ‘Wall Street consensus’, development finance principally supports de‐risking of capital, which circumscribes prospects for a just, green transition. On the consumption side, the wealthy have refused to curtail their consumption and continue to drive increases in carbon emissions. Consider that between 1990 and 2015, world annual carbon emissions grew by 60%; the richest 5% of the world’s population accounted for ~36% of this increase in emissions (Kartha et al., Citation2020). Since the elite tend to be highly educated, we cannot believe that this large increase was the result of their ignorance of the scientific facts about climate change. Whichever way we look at it, class war is blocking the decarbonisation of capitalism.

This practical and ideological misfit is in part to blame for the elite’s inability to realise Climate Leviathan. Taken together, this means that ‘the way forward’ has been blocked. Capital faces a severe contradiction.

But history will not wait, and the world keeps warming. Can the combination of rapid environmental and geopolitical change (e.g., the emergence of a more China-centred geopolitical economy) create the conditions for a Climate Leviathan type of transition? I believe so. But there are other potential pathways, too (see ).

3.3 Other paths

Just as capitalism qua development as adaptation is only emerging (it is not yet dominant), planetary sovereignty does not yet exist; Climate Leviathan is only a potential path. The world today remains capitalist and the prevailing form of sovereignty is not yet planetary. Mann and I call this path ‘Climate Behemoth’; this is the pathway that is beset by the triple crisis, from which we expect a Leviathan to emerge. But what if we are wrong and no transition to Leviathan occurs? Could Behemoth persist?

My answer to this question today is bleak. I think that if humanity remains on the path of Behemoth much longer, we will see the end of our species. Before that end, the era of capitalism qua development will fade into historical memory. What will become of the concept ‘development’? It will be replaced by an emphasis on survival: given the exclusionary and reactionary ideas always bubbling beneath the surface of liberalism, we could only expect a resurgence of the social Darwinist principle of ‘survival of the fittest’ (an expression first used by Spencer (Citation1910/1866), not Darwin; in that work, Spencer uses ‘survival of the fittest’ interchangeably with ‘survival of the most adapted’). Indeed we can already sense this tone at work in the post-2008 discourse of extreme right-wing parties: facing the anxiety of the masses, these paragons of reaction promise to save ‘our’ people, ‘our’ nation, ‘our’ race. This is the basis for what Mann and I call Climate Behemoth.Footnote20

The opposite of Behemoth is the path that Mann and I name ‘Climate Mao’ (though some writers have preferred ‘Climate Lenin’). This is a future where somehow an anti-capitalist movement manages to defeat an emerging Leviathan and create a planetary sovereign from the left. This is, one might say, the dream of the ‘realistic’ revolution, who ‘knows’ that only the power of states can defeat fossil capitalism. What happens to development along this path?

The short answer is that development would lose its prestige and influence. Communism has never promised development: the organising principles are emancipation and justice. But in the meantime, some concepts would likely take the place of development. One logical suggestion is provided in Malm’s (Citation2020) remarkable analysis of COVID, climate and capitalism: ‘war communism’.Footnote21 By this Malm refers to the position of the early Bolsheviks, beset by civil war and attacked from outside. The only ethical posture in that situation is to fight for survival by revolutionary means.

In the face of the traumas on the battlefields of the planetary crisis, war communism has many merits. The appeal for a war communist footing is inspiring in its desire to provide an approach as radical as the challenge we face. Yet what makes Malm’s appeal so touching is its desperation. In the setting where I live (the Midwest of the USA), a political programme appealing for war communism and attacks on energy infrastructure would be a suicide mission. Yet, one might rightly ask in reply: if that is where capitalism has put us, should we not meet it in its ambition?

There is a more prosaic, theoretical limitation to this approach. I have yet to find any climate Leninist or Maoist writer who has addressed the difficult question of planetary sovereignty. To make war communism work, to realise a Climate Lenin or Mao, will require a planetary sovereign, if not actually a world state. The test case is geoengineering, sometimes supported by the war communists in a style of thinking that could be characterised as ecological modernisation plus Lenin (but see Malm, Citation2023b).

4. Conclusions

Is there any plausible anti-capitalist alternative to Climate Leninism and war communism? In Climate Leviathan, Mann and I tried to sketch the conditions for a pathway we call ‘Climate X’, a world that transcends capitalism without planetary sovereignty. We called for mass boycotts and general strikes, steep taxes on wealth, the renewal of mass movements for democratic socialism, and so on. This was the part of our book that received the most criticism: many readers felt that we were too vague about Climate X. We concede this point.Footnote22 I can do little to address this limitation here, but I would like to conclude with a clarification about the question of the place of development and adaptation in Left politics today.

I have argued that the metaphysical tie between capitalist social relations and the dual sign ‘development’ is in doubt. After an era where development defined the basic division of the capitalist world (‘developing’ versus ‘developed’) and provided a code-name and alibi for capital, the era of capitalism qua development is beginning to end. Of the four theoretical paths sketched in Climate Leviathan, it would only retain its importance in world affairs in one. This is the path of an emerging Climate Leviathan, which Mann and I believe is the most likely. In this scenario, capitalism qua development would change: adaptation would become the keyword of an era of capitalist planetary management. Such a shift to capitalism qua development as adaptation does not necessarily signal an organic or hegemonic crisis for global capitalism. On the contrary, it may well strengthen capital’s world hegemony. But this fate is by no means certain.

However understood, a pathway of Climate X would have no truck with the emerging programme of capitalism qua development as adaptation. The goal would instead become something like ecosocialist flourishing, a project of collective liberation beyond capital and its death drive. The fault-line between liberal advocates of capitalism qua development as adaptation and radical alternatives will become clearer in the next decade as these matters become more concrete.

For now, in the face of the triple crisis, we desperately need to cultivate a practical set of responses to build genuine alternatives. Among other things, we must reconstitute a metaphysics of ecological communism. I do not know what all this will entail, but I am confident that it will not be capitalism qua development as adaptation. Saito’s (Citation2023) proposal for ‘degrowth communism’ provides one indication of what is needed. However, just as development has always meant more than mere growth, alternatives to development will need to do much more than stop growth (I take it this is why Saito uses ‘degrowth’ as an adjective to qualify ‘communism’). If we are to achieve Climate X, or climate justice, development would need to be suspended, decolonised; its historical tie to capital would need to be broken permanently. Whenever capitalism is treated as development, the violence of capitalist social relations has been naturalised; the overcoming of capital therefore requires breaking its tie to development. Thus, of development we could say what Adorno (Citation1998/1962) once wrote of ‘progress’: ‘one cannot employ the concept roughly enough’. And the same for capitalism qua development as adaptation. Amidst the triple crisis, at a moment when our world is crying out for a new direction, we have a responsibility to provide a renewed critique of precisely those concepts that are said to provide the only ‘way forward’ (IPCC, Citation2023). We cannot employ concepts like development and adaptation roughly enough. We should not tell the poor to adapt to this capitalist world on fire. We should link arms with them to end it.

Acknowledgements

I thank Trevor Barnes, Luke Bergmann, Brett Christophers, Michael Dunford, Mansi Goyal, Ray Hudson, Marwan Safar Jalani, Lev Jardon, Will Jones, Geoff Mann, Kristin Mercer, James Murphy, Eric Sheppard and Henry Yeung. This paper is based on the 2023 Area Development and Policy Lecture delivered at the Annual Meetings of the American Association of Geographers in Denver. The author thanks the journal and its editors for the privilege.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. The precise ratios differ between oil, coal and natural gas, as well as ownership v production v investment. The best source for these data is the International Energy Association (IEA): see https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics

2. The left does not yet have a political strategy for this problem of the ‘stranded assets’: see Malm (Citation2023a). Reviewing data from the International Energy Association (IEA), Adam Tooze (Citation2023) summarises the present strategy of the managers of fossil capital: ‘owners and managers of the fossil fuel complex are increasingly anticipating a constrained future. To keep their shareholders happy and their stock market valuations up, they are deleveraging and paying out larger dividends. Investment is flat, but what is not happening so far to any significant degree is a move by the existing oil and gas industry either to cut investment to long-run sustainable levels or to join the energy transition. We are in a situation of suspended animation’.

3. Something similar could be said for the non-human species with which we share the planet. Climate change is a major driver of declining species diversity and the sixth great extinction (Sage, Citation2020). Yet non-human species have no political agency.

4. This problem is entangled with the ascent of finance capital as the dominant fraction of capital since the 1970s (Arrighi, Citation1994, Citation2007). My brief discussion emphasises the demand side, as I believe it should, but I recognise that supply side dynamics also contribute to crisis tendencies.

5. Arrighi (Citation1994), p. 164.

6. Compare Fraser (Citation2017)’s ‘triple movement’.

7. This last point has long been emphasised by political ecologists. It is to the credit of IPCC Working Group II that versions of this truth have surfaced in their reports (see, e.g., IPCC, Citation2022).

8. It is notable that the only large society in the world to avoid political crisis (as defined above) since the 2008 economic crisis is China, which is not governed by a liberal state.

9. Even the relatively constrained and conservative IPCC reports now call for ‘far-reaching transitions across all sectors and systems … to achieve deep and sustained emissions reductions’ (IPCC, Citation2023, C.3).

10. These words stem from an earlier English form, ‘disvelop,’ closely related to the modern Italian ‘viluppare,’ meaning ‘to enwrap, to bundle’ (OED, Vol. IV, p. 562). This paragraph and the following five recapitulate claims that originally appeared in Wainwright (Citation2003), in revised form in Wainwright (Citation2011).

11. See Howard (Citation1992), p. 79.

12. This is a paraphrase of Cowen and Shenton’s (Citation1996) central thesis: the ‘intention to develop is routinely confused with an immanent process of development.’ For Cowen and Shenton, the historical coalition of the imminent process with an intention to develop comprises a particular doctrine of development; the object of their historical survey is the doctrine of development. While their analytic history of is important and useful, they side-step the question of capitalism.

13. Hence, I do not think we should use the expression ‘capitalist development’ (or use ‘development’ as a shorthand for that expression). To do so is to imply an undeserved morality and directionality to capital. However, the expression ‘development of capitalism’ remains valuable. I take this to mean the expansion of specifically capitalist social relations based upon commodity production and the transfer of value from subaltern groups to the capitalist class (Marx, Citation1867/1976).

14. For instance, in the USA, where I live, everyone knows that our society was fully capitalist fifty years ago. Yet who could deny that the USA is even more capitalist today, with more areas of our lives converted into sites of commodity production and consumption? Who imagined, fifty years ago, the extent to which children’s attention would be commoditized today – and with such great social consequences?

15. Development could be characterised, therefore, as a reconstructive aspect of Polanyi’s Citation(1944/2001) double movement of capital.

16. An earlier version appears in Wainwright (Citation2003). In the early 2000s, when worked out these arguments, there were many attempts to criticise development, too many to cite here. Arguably the best known was Arturo Escobar’s brand of ‘post development,’ which I rejected (e.g., Wainwright (Citation2003, Citation2010); Asher and Wainwright (Citation2019)). For critical approaches that overlapped in spirit with my own, see Sanyal (Citation2014) and Gidwani (Citation2008). In retrospect the debates of the time came in response to the strange atmosphere of development studies in the 1990s after the fall of the USSR. Capital had won; capitalism qua development presented itself as the only way forward. Our critiques of development were responses to that stifling condition. There were also political sources of inspiration. I am of the generation inspired by the Zapatista uprising of 1994, which reminded us that anticapitalism and anticolonialism march together: see EZLN (Citation2016).

17. This world-historical division, and the relative stability of capitalism qua development, is inseparable from the history of European imperialism, including post-war US hegemony. (The decline of US hegemony is one of the processes threatening to bring this era to a close.)

18. To clarify a common misunderstanding: although we regard Climate Leviathan as the most likely path before us, it is not our preferred path. In terms of the book, the order of probabilities = Leviathan, Behemoth, Mao, X. The order of our preferences = X, Mao, Leviathan, Behemoth.

19. The IPCC (Citation2023) synthesis report, e.g., says that ‘the way forward’ is ‘climate resilient development… to adapt’.

20. Malm and The Zetkin Collective (Citation2021) use the alliterative term, ‘fossil fascism’: same monster, different name.

21. Malm’s reference, of course, is to Lenin’s strategy in the wake of World War I and the Bolshevik Revolution. Žižek (Citation2022) recently appealed to the same concept.

22. See, for example, the criticisms of our book in Rethinking Marxism 32(4) and our response (Wainwright and Mann (Citation2020). In fairness to ourselves, it is difficult to articulate a democratic pathway to ecosocialist revolution.

References

- Adorno, T. (1998/1962). Excerpt from progress, Lecture at Münster Philosophers’ congress, 22 October 1962 (H. Pickford, Trans.). In Critical models: Interventions and catchwords (pp. 143–160). Retrieved August 19, 2023, from. http://tomclarkblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/theodor-adorno-some-thoughts-on.html

- Alvaredo, F., Atkinson, A. B., Chancel, L., Piketty, T., Saez, E., & Zucman, G. (2022) World inequality database. Retrieved November, 22 2023, from https://wid.world/data/

- Aristotle. (2001). Physics. In R. McKeon (Ed.), The basic works of Aristotle. Modern Library.

- Arrighi, G. (1994). The long twentieth century: Money, power, and the origins of our times. Verso.

- Arrighi, G. (2007). Adam Smith in Beijing: Lineages of the twentieth century. Verso.

- Asher, K., & Wainwright, J. (2019). After post‐development: On capitalism, difference, and representation. Antipode, 51(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12430

- Burkett, P. (1999). Marx and nature: A red and green perspective. Springer.

- Cowen, M., & Shenton, R. (1996). Doctrines of development. Taylor & Francis.

- Darwin, C. (1963/1859). On the origin of species. Harvard University Press.

- Dunford, M. (2021). Global reset: The role of investment, profitability, and imperial dynamics as drivers of the rise and relative decline of the United States, 1929–2019. World Review of Political Economy, 12(1). Retrieved August 21, 2023, from https://doi.org/10.13169/worlrevipoliecon.12.1.0050

- EZLN. (2016). Critical thought in the face of the capitalist hydra I: Contributions by the sixth commission of the EZLN. Paperboat.

- Fraser, N. (2017). A triple movement? Parsing the politics of crisis after Polanyi. In M. Burchardt & G. Kirn (Eds.), Beyond neoliberalism: Social analysis after 1989 (pp. 29–42). SpringerLink.

- Gabor, D. (2021). The Wall Street consensus. Development and Change, 52(3), 429–459.

- Gidwani, V. (2008). Capital, interrupted: Agrarian development and the politics of work in India. University of Minnesota.

- Hegel, G. W. F. (1985/1805-6). Introduction to the lectures on the history of philosophy. Oxford.

- Homer-Dixon, T., Renn, O., Rockstrom, J., Donges, J. F., & Janzwood, S. (2021). A call for an international research program on the risk of a global polycrisis. Retrieved September 20, 2023, from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4058592

- Howard, M. (1992). A Hegel dictionary. Blackwell.

- Hudson, R. (2023). Capitalist development, the impossibility of ‘green’ capitalism, and the absence of alternatives to it. Area Development and Policy, 1–9. Retrieved November 22, 2023, from https://doi.org/10.1080/23792949.2023.2269406

- IPCC. (2021). Report of working group I (AR6): Summary for policy makers. Retrieved September 20, 2023, from https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_SPM.pdf

- IPCC. (2022). Report of working group II (AR6). Retrieved November 24, 2023, from https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-working-group-ii/

- IPCC. (2023). Synthesis report (AR6): Headline statements. Retrieved September 20, 2023, from https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/resources/spm-headline-statements

- Kartha, S., Kemp-Benedict, E., Ghosh, E., Nazareth, A., & Gore, T. (2020). The carbon inequality era: An assessment of the global distribution of consumption emissions among individuals from 1990 to 2015 and beyond. Retrieved September 20, 2023, from https://www.sei.org/publications/the-carbon-inequality-era/

- Klein, N. (2015). This changes everything: Capitalism vs. the climate. Simon and Schuster.

- Luxemburg, R. (2003/1913). The accumulation of capital. Routledge.

- Machiavelli, N. (2014/1513). The prince and other writings. Simon and Schuster.

- Malm, A. (2016). Fossil capital: The rise of steam power and the roots of global warming. Verso.

- Malm, A. (2020). Corona, climate, chronic emergency: War communism in the twenty-first century. Verso.

- Malm, A., & The Zetkin Collective. (2021). White Skin, Black Fuel. Verso

- Malm, A. (2023a). Interview of Andreas Malm by Sebastian Budgen. Retrieved November 27, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kVC8lL84UrU

- Malm, A. (2023b). The future is the termination shock: On the antinomies and psychopathologies of geoengineering. Part one. Historical Materialism, 30(4), 3–53. https://doi.org/10.1163/1569206x-20222369

- Marx, K. (1976/1867). Capital volume one. Penguin.

- Polanyi, K. (1944/2001). The great transformation: the political and economic origins of our time (2nd ed.). Beacon.

- Sage, R. (2020). Global change biology: A primer. Global Change Biology, 26(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14893

- Saito, K. (2017). Karl marx’s ecosocialism: Capital, nature, and the unfinished critique of political economy. Monthly Review.

- Saito, K. (2023). Marx in the Anthropocene: Towards the idea of degrowth communism. Cambridge University Press.

- Sanyal, K. (2014). Rethinking capitalist development: Primitive accumulation, governmentality and post-colonial capitalism. Routledge.

- Smith, A. (1982/1776). The wealth of nations. Penguin.

- Spencer, H. (1910/1866). The principles of biology. Vol. 1. Appleton.

- Tooze, A. (2022). Welcome to the world of the polycrisis. Financial Times. Retrieved September, 20 2023, from https://www.ft.com/content/498398e7-11b1-494b-9cd3-6d669dc3de33

- Tooze, A. (2023). Chartbook carbon notes 8: Betting on climate disaster. The possible futures of the (US) oil and gas industry. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP). 2022. UCDP/PRIO armed conflict dataset version 23.1. Retrieved February 10, 2024, from https://ucdp.uu.se/downloads/index.html#armedconflict

- Wainwright, J. (2003). Decolonizing development: Colonialism, Mayanism, and agriculture in Belize [ PhD thesis]. University of Minnesota.

- Wainwright, J. (2010). Review of arturo escobar, Territories of difference: Place, movements, life, redes. Environment and Society, 1(1), 185–188.

- Wainwright, J. (2011). Decolonizing development: Colonial power and the maya. John Wiley & Sons.

- Wainwright, J., & Mann, G. (2018). Climate Leviathan: A political theory of our planetary future. Verso.

- Wainwright, J., & Mann, G. (2020). Capital and climate in times of coronavirus: Reply to critics. Rethinking Marxism, 32(4), 451–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/08935696.2020.1807237

- Žižek, S. (2022). War in a world that stands for nothing. Project Syndicate. April 18 2022. Retrieved November 27, 2023, from https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/russia-ukraine-war-highlights-truths-about-global-capitalism-by-slavoj-zizek-2022-04