Abstract

Earlier studies describing and categorising the development of museum websites either build on theoretical knowledge or the analysis of a qualitative sample of relatively few, but prominent museum websites. The present study takes a broader approach and aims to characterise the development across Danish museum websites through the years 2005–2020. The methodological approach is a diachronic (temporal) analysis of Danish museum websites using data extracted from the Danish Web. A cluster analysis was used to identify similarities between museum websites. The cluster analysis shows that the museum website representations possess distinct attributes pivotal to their degree of resemblance with others, such as collection type, geographical location, organisational structure and whether the communication and dissemination strategy focus on disseminating collection content or extends to a broader communication scope. However, the quantitative text analysis approach to studying archived museum websites did not identified a new typology. Instead, the study suggests how a cluster analysis of the Danish museum web sphere can constitute an initial step in comprehending domain development, and ultimately discerning the attributes that characterise the different museum website clusters.

Introduction

In 1994, Wallace and Jones-Garmil wrote an article in Museum News critically discussing the question: “What will the Internet mean to museums, and what will museums mean to the Internet?” (Wallace & Jones-Garmil, Citation1994, p. 33). They predicted that it would be a lasting relationship, and that introducing “new electronic superhighways” in the museum domain would raise questions far beyond technology. Today museums are part of a broader communications landscape, and the museum encounter is increasingly a mediated one (Drotner & Schrøder, Citation2013; Kidd, Citation2019; Samis, Citation2008). Dziekan and Proctor use the term distributed museology to describe the multimedial nature of contemporary museums and their presence on multiple platforms (Dziekan & Proctor, Citation2019, p. 179). In this constantly evolving media landscape, the museum website continues to play a central role, and having an online presence in the form of a website is today mandatory. Accordingly, most museums have developed institutional websites and digital technologies have become an integrated part of many exhibitions. However, whereas the development and use of digital technologies within the physical museum has received much attention, less attention has been devoted to understanding the role and development of museum websites. This may be explained by how exhibitions continue to be the focal point for museum work and the primary way museums communicate to the public (Anderson, Citation2018; Lester, Citation2006).

The introduction and later widespread use of digital technologies in museums takes place co-occurrent with the increased attention to the ‘new museology’ framework (Vergo, Citation1989) encompassing the social and political roles of museums, encouraging new communication and new styles of expression in contrast to classic, collections-centred museum models (Mairesse & Desvallées, Citation2010). A famous quote by Stephen Weil reflects the changing character of museum work and the relationship to visitors “from being about something to being for somebody” (Weil, Citation1999). Following this, new museology can be seen as a paradigm shift representing a departure from traditional approaches to museums and to making museums more inclusive, participatory, and relevant to different audiences. The use of digital technologies has played a significant role in this development (Cameron, Citation2008; Fernandez-Lores et al., Citation2022; Ross, Citation2015) by supporting museums in communicating and interacting with their visitors in new ways, creating wider access, and encouraging visitor engagement and participation etc. Earlier work (Axelsson, Citation2018; Chakraborty & Nanni, Citation2017; Drotner & Schrøder, Citation2013; Schweibenz, Citation2004) has proposed different categorisations to describe the development of museum websites (elaborated in the related research section), and both Chakraborty and Nanni (Citation2017) and Schweibenz (Citation2004) relate the development in museum websites to the transition from collections-centred to more user-centred museum models.

Critical voices, however, argue that even though new museology has been a useful tool for museum workers, new museology has “had less practical effect than the museology literature might anticipate” (McCall & Gray, Citation2014, p. 31). This can according to McCall and Gray be explained by competing tensions, structural constraints and limitations in museum practice, and therefore “the discourse related to the old and ‘new’ museology is dynamic” (McCall & Gray, Citation2014, s. 32).

The present article argues that the role and development of the museum website is an understudied area of research. At the same time, the majority of the existing studies on the development of museum websites and user interaction, needs and preferences in connection with museum websites builds on a qualitative selected and limited number of websites. Therefore, the present study takes a broader empirical scope and aims to characterise the development across Danish museum websites through the years 2005–2020. Similar to Chakraborty and Nanni (Citation2017), the study will use archived websites as primary sources, as internet archives open unique opportunities for studying the characteristics and development of museum websites over time. The main research question guiding the study is: What characterises the development of Danish museum websites through the years 2005–2020?

As pointed to above, media convergence and distributed museology have led to museums communicating through numerous digital media such as blogs, YouTube, podcasts, social media, and websites. In the modern web environment museum content is not only presented on the museum’s own website but can also be represented on different platforms and aggregators such as Europeana and Google Arts & Culture. Sometimes communication on different platforms and media takes place in parallel and sometimes museums’ communication streams are intertwined making it difficult to tell when the museum visit starts and ends. While we fully acknowledge the complexity of media use in museums, the present study focuses on websites as one important media format relevant to most museums.

Related research

Even though museum websites have received less attention compared to the use of digital technologies within the physical museum as a digital layer in exhibitions, several previous studies examine museum websites with different foci and methodological approaches. Guided by the research question, this section on related research focuses on how museum websites have been categorised into different types and phases.

First, however, we will briefly introduce the area of research that provides insights into user interaction, needs and preferences in connection with museum websites. Overall, this area of research illustrates why the museum website is a central communication channel. Studies show how the museum website plays an important role in attracting future online and physical visitors (Fernandez-Lores et al., Citation2022), and how online visitors use the museum website to complement their visits to the physical museum or as a destination in its own right (Marty, Citation2007, Citation2008; Walsh et al., Citation2020). A recent evaluation study (Ma & Hu, Citation2022) of websites of first-class museums in China developed a utility index highlighting the importance of content completeness, update speed, comprehensiveness, and accuracy in context of museum websites. Studies also highlight the importance of understanding what the visitor is looking for on museum websites and how this depends on the use situation, eg whether it is before or after the museum visit (Marty, Citation2007), whether it is special interest users (Skov & Ingwersen, Citation2014) or the general public (Walsh et al., Citation2020). While empirical studies (Marty, Citation2007, Citation2008; Walsh et al., Citation2020) show how a majority of online visitors are primarily motivated by planning an up-coming visit to the physical museum, and accordingly looking for basic information like fees, location, directions, current exhibitions etc., online visitors’ expectations and motivations continuously evolve (Fernandez-Lores et al., Citation2022; Parry, Citation2019). Today, online visitors come with different motivations and expect museum websites to promote learning, enable interaction, and foster joyful and aesthetical experiences (Lin et al., Citation2012; Lopatovska, Citation2015). Summing up, the research area of user interaction, needs and preferences confirms the website as an essential media in the museum sector and point to heterogeneous demands and evolving expectations to the museum website.

The next part of the related work section describes three approaches to categorisation of museum websites. The categorisations will highlight different characteristics of museum websites, suggest phases in a temporal development and serve as background and comparison for the following analysis.

An early contribution to a categorisation of museum websites is presented by Schweibenz (Citation2004). He suggests four categories of online museums presented as a development from the very basic website to the end goal, namely the virtual museum: (1) The brochure museum contains the basic information about the museum and aims to inform potential visitors about the museum; (2) the content museum presents collections in an object-oriented way, and “is more useful for experts than for laymen because the content is not didactically enhanced” (Schweibenz, Citation2004); (3) the learning museum is context-oriented and presents different access points to didactically enhanced content; and (4) the virtual museum aims to implement a museum without walls by creating links across digital collections and institutions. Schweibenz’s (Citation2004) categorisation is presented before the concepts of web 2.0 and social media influenced museum communication including website aim, content and functionality. Nevertheless, the categorisation is still viewed relevant, and we will return to it in the analysis below.

A second approach to categorisation is presented by Chakraborty and Nanni (Citation2017) based on a diachronic analysis of archived internet resources combined with qualitative interviews with websites managers. Their analysis illustrates how three prominent science museums’ websites develop over a 20-year period and results in a periodisation of four macro phases to track significant changes. Chakraborty and Nanni’s (Citation2017) periodisation partly builds on Schweibenz (Citation2004) categorisation and Simon’s (Citation2010) influential work on the participatory museum. The periodisation includes the leaflet museum, the virtual museum, the outreach museum, and the social media museum. Overall, the proposed periodisation reflects how the museums “traditionally viewed as authoritative, top down entities, have constantly worked towards developing websites that go beyond being informative, which have in turn become the central node of an interactive, multidirectional communication between the museums and their visitors” (Chakraborty & Nanni, Citation2017, p. 170). The four macro phases reflect an overall development from web 1.0 to 2.0 web in regard to tools for dissemination and facilitating interaction with the public (Capriotti et al., Citation2016).

A third approach to a categorisation of museum websites is derived from Drotner and Schrøder’s (Citation2013) suggestion that museums navigate between two main discourses: to engage audience as subjects for learning or to serve them in terms of customers. Axelsson (Citation2018) explains how these two main discourses are reflected in museums’ use of digital media including websites. Today visitor numbers etc. are important to many museums and digital technology fits this marked logic well, “as it is a relatively straightforward procedure to prove engagement by displaying numbers of website visitors, digitised items and downloads from collection databases as well as social media likes, friending, sharing and hashtagging” (Axelsson, Citation2018, p. 68).

The three different approaches to describing and categorising museum websites will serve as background and comparison for the following analysis. Common to the reviewed studies is, that the categorisations either build on theoretical knowledge (Axelsson, Citation2018; Drotner & Schrøder, Citation2013; Schweibenz, Citation2004) or the analysis of a qualitative sample of relatively few, but prominent museum websites (Chakraborty & Nanni, Citation2017). Similarly, the related studies focusing on the interaction, needs and preferences in connection with museum websites also target either a single or a small number of selected websites (eg Fernandez-Lores et al., Citation2022; Skov & Ingwersen, Citation2014; Walsh et al., Citation2020). The present study takes a broader approach and aims to provide an overview of the development of Danish museum websites through a 15-year period, and the methodological approach will be explained in the following section.

Methodology

Using an internet archive as primary data source

Looking back at the first wave of museum websites shows how a few pioneering museums, mainly science and technical museums, were early adopters of the internet media and launched experimental websites as early as 1993 (Gaia et al., Citation2020). In Denmark, to the best of our knowledge, the first museum website was launched in 1997 by the National Museum as a pilot project (Hansen & Ødegaard, Citation1997). The present study commences somewhat later and is a historical study of Danish museum websites from 2005 to 2020 building on a sample from the national Danish Web Archive (for more information about the Danish Web Archive, see Laursen & Møldrup-Dalum, Citation2017). Internet archives preserve versions of internet material, and even though the field of internet archive studies is still young and methodological challenges persist, several studies covering a variety of fields, eg social media, politics, and advertising, illustrate a rich potential (Brügger, Citation2018).

The present study aims to contribute to the field of web archive research, where only few studies so far have been devoted to the area of museums. In addition, our study aims to contribute to the field of museum research by exemplifying how archived websites can be used as a primary source to trace and describe the development of museums’ online presence.

The methodological approach is a diachronic (temporal) analysis of Danish museum websites. Similar to Chakraborty and Nanni (Citation2017), we use archived websites as a primary source to describe the development of museums’ websites. As described above, Chakraborty and Nanni (Citation2017) qualitatively select three prominent science museums and do a close study of the development of the three museums’ webpages through snapshots from the Internet Archive. A different level of analysis is used in the present study, as a more quantitative and distant reading and analysis of the Danish museum web sphere is applied, which will be explained in the following section.

Data from the national Danish Web archive

This section describes the steps taken to collect and prepare the dataset for analysis, and methodological challenges related to extracting, cleaning, and preparing the data for analysis are discussed.

In context of the present study, the Danish museum web sphere is defined as all state owned or state approved museums in Denmark (hereafter referred to as state funded). For state funded museums, there are certain requirements in relation to the collections, collection management, research obligations etc. Furthermore, to gain insight into the temporal aspect, the dataset includes the years 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020. The year 2005 has been chosen as a starting point since the Danish Web Archive started to collect material from the Danish part of the internet that year, and by 2005 the majority of Danish museums had established their own websites.

To obtain a comprehensive dataset, the first step was to conduct free text searches in the Danish Web Archive based on a see list of all names of state funded museums to 1) identify whether the specific museum websites were collected and preserved in the Danish Web archive, and 2) identify the correct URL. shows the number of state funded museums in Denmark across the four years (column 2). The number of state funded museums decreases from 147 museums in 2005 to 102 museums in the year 2020, mainly explained by a large wave of mergers triggered by the restructuring of the counties and municipalities in 2007 (Nørskov, Citation1970). Furthermore, (column 3) shows the number of museum websites identified in the Danish Web archive for each year. The table shows how all museum websites could be identified in the Danish Web Archive in 2015 and 2020, but in 2005 and 2010 there were respectively 15 and 3 museums that were not identified. These museum names were also searched in the Internet Archive with no result. These museums predominantly encompassed smaller museums, with a significant proportion subsequently merging with other museums. As a result, it is plausible to surmise that many of these museums did not have an individual website. Overall, the dataset substantiates that the Danish museum sector has been early adopters of the internet medium.

Table 1. Overview of website distribution over the four selected years of the dataset in terms of the general number of state-owned or state approved museums, how many of those that were represented in the Danish web archive, and the number that was included in the analysis.

Next step was to write an ETL specification to specify the data extraction from the Danish Web Archive. The ETL specification defined how a search query should be performed that retrieved web pages of the list of earlier identified museum URLs for the years 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020. Based on the ETL specification, the dataset was extracted in three formats: metadata, text content and links. For the analysis in this paper, only the metadata and text files have been used. The text content data includes written text from all the websites, and the metadata files include information about date, title, URL, document type etc.

In the final step, the extracted data were cleaned and prepared for further analysis. Duplicates were removed from the dataset by indexing non-duplicates using the tidyverse package in R. Upon the text analysis German and English chunks of text were removed to uniform the terminology used on the websites. Also, cookie messages and copyright information were removed because they potentially occur on many websites and bias the analysis of content bearing text on the museum websites. Data quality remains a challenge in web archive studies especially in relation to data completeness and systematic biases (Hale et al., Citation2017). Despite the cleaning steps just mentioned, errors and messy data still occurred in some files. Thus, during the data cleaning and quality check for this study, a few websites were removed because of very little text (missing data) or too many errors in the text, and the depth of the harvested material varies from museums to museum and between years. Whether errors and incomplete data are a result of the harvest process in or extraction process from the Danish Web archive, is also difficult to say. shows the number of unique museum websites in the dataset after the cleaning and quality check (column 6). Behind all the numbers in , the dataset reflects the development of Danish museums: how and when museums are renamed, merge with other institutions, change website address etc.

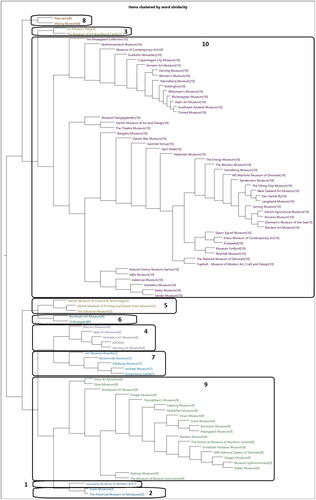

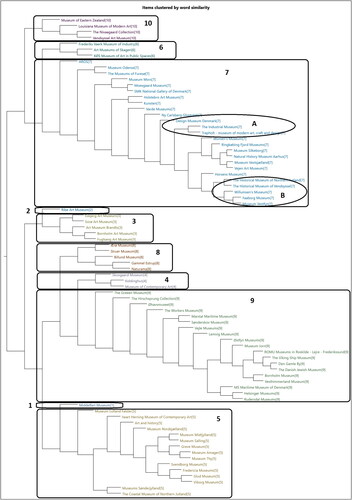

Cluster analysis

A cluster analysis was used to identify similarities between museum websites. From the metadata files text were divided between title texts and content text. As it turned out that title texts were more comparable than the content text, we decided to conduct the cluster analysis on these chunks of text. We used NVivo to conduct the cluster analysis. Two cluster maps were carried out, one for 2005 and one for 2020. The cluster analysis was based on k-means clustering (Grimmer et al., Citation2022; Jain, Citation2010). K-means clustering represents an unsupervised clustering technique, which enables the identification of similarities based on geography, topical coverage of the museums, target groups, museum position, communication strategy etc. The number of clusters were set to 10 for both the 2005 and the 2020 analysis. The aim of this limit was to avoid clusters with just one website along with very large clusters. However, as appears from and , this could not be done with the study data. Thus, we see a few examples of both in the two figures, indicating that the included museums represent a large diversity among them.

Ethical considerations

The collected material in the national Danish Web Archive contains sensitive personal information and therefore researchers must apply to the Royal Library in Denmark for permission to access the Web archive. Based on a description of the project, we received permission to search and extract data from the archive. All data are stored on a closed server at Aalborg University to which only the project group has access.

Results and analysis

The analysis is divided into three sections. First the two cluster maps for 2005 and 2020 are analysed individually, followed by an analysis of temporal insights through a comparison of the developments from 2005 to 2020. Based on the research question, our aim is to explore whether text analysis can be employed to derive meaningful categories that assist in characterising museum websites both within a single year and across years. Cluster analysis can serve as an initial step in investigating which museums exhibit semantic-level similarities.

First, the cluster map for the year 2005 is examined. The 2005 cluster map () is composed of 10 clusters (K = 10), and the map is dominated by one very large cluster (10). To examine the cluster in more detail, revisiting the museum websites in the national Danish Web archive and reading excerpts from the text files was necessary. The dominant cluster includes a broad variety of different museums in relation to size, type, profile, and geographical location. Even though the museum profiles in cluster 10 represent a wide variety of museums, the textual representations share an emphasis on standard attributes such as about the museum, presentation of collections and exhibitions, activities, practical information about visiting, and not least information on selected individual museum items etc. Therefore, the dominant cluster 10 can best be described as representing typical museum websites in the year 2005. The textual representations indicate that at this point in time, a pronounced degree of uniformity prevailed, as compared to later development and trends. In addition to the large cluster 10, the cluster map for 2005 shows a medium-sized cluster (9) and eight small clusters with one to five museums in each cluster. Most of the small clusters are characterised by museum type, such as art museums (clusters 1, 3, 4 and 6), technical and industrial museums (cluster 5) and history & cultural museums (cluster 2 and 7).

Next, we look at the cluster map for the year 2020 (K = 10). The 2020 cluster map () includes three major clusters encompassing 15–25 representation of museum websites, five minor clusters consisting of three to five museum websites, and two clusters comprising only a single museum website each. Especially the two largest clusters (7 and 9) exhibit a high degree of heterogeneity, making it challenging to discern their distinct characteristics. Both clusters 7 and 9 include a mix of different museum types and both medium-sized museums and larger prominent museums, and accordingly it is difficult to characterise and label these two clusters. Zooming in on distinct areas in the tree structure of the clusters, however, highlights different groupings of museum websites. For example, groupings based mainly on collection topic, in this case craft and design (2020 map, area A) or geographical location (2020 map, area B). Compared to the two largest clusters, the last of the three major clusters, cluster 5, is more easily characterised. This cluster is dominated by websites of museums with diverse collections, spanning fields such as archaeology, cultural history, and local history and/or encompass several exhibition venues. The majority, 9 out of 15, of the museums in this cluster (5) are the result of museum mergers after 2005.

In addition to these three major clusters, there are several smaller clusters in which it is easier to discern standout attributes. In these cases, museum type emerges as a dominant attribute, as evidenced by clusters 3, 4, and 10 predominantly representing art museums. However, it is particularly interesting to investigate the distinctions among these clusters. Again, revisiting the museum websites in the national Danish Web archive and reading excerpts from the text files was necessary. The analysis shows, how the text from museum websites in cluster 3 encompasses a broader communication as more sections and text are devoted to topics such as upcoming events to diverse audiences, educational and social activities. In contrast, the museums in clusters 4 and 10 provide significantly less textual content on these subjects, instead focusing on describing collection content. The same pattern extent for the two museums constituting individual clusters (1 and 2).

Finally, the two cluster maps are compared to highlight temporal developments from 2005 to 2020. As pointed to above, a main difference between the two cluster maps is the resolution of the large cluster (10) dominating the map in 2005. Instead, the 2020 map includes several larger and medium-sized clusters, which indicates that the museum websites in 2020 represent more distinct attributes compared to 2005.

A comparison of the two cluster maps can further assist in tracking individual museums that have significantly evolved their profiles over time. The identification of relevant museums is based on background knowledge about the museum domain. Two examples from the dataset are presented to illustrate, namely the museum Koldinghus and MS Maritime Museum of Denmark. In 2005, both museums were part of the large dominant cluster (10), which was described in the section above as primarily encompassing standard museum websites with a pronounced degree of uniformity. Both museums have changed position in the 2020 cluster map and appear in smaller clusters. As of 2020, Koldinghus museum is positioned in Cluster 4 on the cluster map. This shift effectively represents the museum’s progression from being a traditional cultural-historical castle museum to a museum that contextualises the history of the castle through a series of special exhibitions, including some with strong artistic and aesthetic expressions. This explains the why Koldinghus museum is part of cluster 4, which consists of art museums. The frontpage of Koldinghus museum website from 2005 and 2020 is shown in . Similarly, the MS Maritime Museum of Denmark has shifted from its position in the broad cluster 10 in 2005 to Cluster 9 in 2020. This change mirrors the museum’s evolution from being a specialised museum of maritime history primarily focusing on ship models etc. to adopting a much broader perspective encompassing maritime history and culture. On the 2020 map, the MS Maritime Museum is now located in Cluster 9 alongside general cultural-historical museums. The frontpage of The MS Maritime Museum website from 2005 and 2020 is shown in .

Figure 3. The websites of the Koldinghus museum from 2005 (left) and 2020 (right). Source the Internet Archive.

Figure 4. The websites of the Danish Maritime Museum 2005 (left) and 2020 (right). Source the Internet Archive.

Summing up, the cluster analysis shows that the website representations possess distinct attributes pivotal to their degree of resemblance with others, such as collection type, geographical location, organisational structure and whether the communication and dissemination strategy focus on disseminating collection content or extends to a broader communication scope. In both 2005 and especially in the 2020 map, clusters can help highlight patterns in the dataset and point to standout attributes that signifies a group of websites. However, both maps also include highly heterogeneous clusters that are more difficult to profile.

Discussion

This section discusses the methodological advantages and challenges of using archived web materials, and specifically cluster analysis, to describe the development of the Danish museum domain.

As stated by Fage-Butler et al. (Citation2022), the field of web archive studies remains a relatively new area of research, necessitating the development and testing of novel methodologies. In this discourse, we argue that a quantitative approach based on cluster analysis provides the opportunity to explore a significant number of websites, such as the Danish museum web sphere. A quantitative approach can provide overview and highlight patterns beyond those identified by studies focused on qualitatively selected prominent museum websites (e.g., Chakraborty & Nanni, Citation2017; Fernandez-Lores et al., Citation2022; Lopatovska, Citation2015). Furthermore, a corpus including a broad representation of a variety of museum websites (in regard to museum type, size, geographical location etc.) also reduces the risk of bias, which is challenge in some aggregated collections (Kizhner et al., Citation2021).

The present study suggests that several variables may be pertinent to the grouping of museum websites based on textual characteristics, including collection type and topic, geographic location, and whether the communication and dissemination strategy focus on collection content or encompasses a broader communicative scope. As such, the clusters are subjective entities and interpretation requires domain knowledge (Jain, Citation2010), which in this study necessitates an iterative analytical process between cluster maps and qualitative analysis of select websites in the web archive. Furthermore, it is important to complement textual analysis with analysis of, e.g., websites’ information architecture, their visual manifestations, and interaction design. For instance, some museum websites feature aesthetics (Lopatovska, Citation2015) which is difficult to understand through text analysis alone.

The cluster analysis surprisingly indicates that the textual descriptions across museum websites in 2005 and continuing into 2020 to a high degree are characterised by text introducing collections, exhibitions, and information about individual objects. In other words, there is a predominant focus on presenting content, and the cluster analysis does not reflect the previously described development in museum websites from being collections-centred to being user-centred (see e.g., Cameron, Citation2008; Chakraborty & Nanni, Citation2017; Schweibenz, Citation2004). This result suggests two things. Firstly, that even though the modern museum visitor expects interaction and dialogue as part of an online museum visit (Lin et al., Citation2012; Lopatovska, Citation2015), the museum still widely controls the communication (Fernandez-Lores et al., Citation2022). Secondly, the result also suggests that across the Danish museum sphere, there is less of a shift in the development of museum websites from one category to another in a temporal progression (as suggested by, e.g., Chakraborty & Nanni, Citation2017; Schweibenz, Citation2004), but rather that different website categories (for example the content museum, the outreach museum, the social-media museum) exist simultaneously and intertwined.

As pointed to in the introduction, the modern museum increasingly communicates through numerous digital media channels and platforms in a heterogeneous digital landscape which complicates the study of the domain in the modern Web-environment. The present study’s focus on museum websites can therefore be seen as an inherent methodological challenge as aspects relating to, e.g., user-centred dialogue and interactions are highly interconnected with museums’ social media presence and not only museum websites. As a consequence, analysis of archived web materials can contribute to describing the development of the Danish museum domain but cannot provide the full picture.

Conclusion and next steps

The present study aimed to characterise the development across Danish museum websites through the years 2005–2020 using quantitative text analysis to study archived web material. The study led to fruitful insights about both the use of cluster analysis and the specific text corpus, and the study suggests how a cluster analysis of the Danish museum web sphere can constitute an initial step in comprehending domain development, and ultimately discerning the attributes that characterise the different museum website clusters. Based on domain knowledge, the interpretation of clusters identified a number of distinct attributes, including collection type, geographical location, organisational structure and whether the communication and dissemination strategy focus on disseminating collection content or extends to a broader communication scope. These attributes can help identify patterns and characteristics across large samples of museum websites and point to trends, but the quantitative text analysis approach did not identify a new, overall typology of museum websites.

The results further indicate that the textual descriptions across museum websites to a surprisingly high degree describe content such as text introducing collections, exhibitions, and information about individual objects. Accordingly, based on text analysis our study cannot confirm a clear development in museum websites from being collections-centred to being user-centred. Instead, we suggest that different website categories exist simultaneously and intertwined. Further analysis should be conducted to confirm and nuance these findings. Next steps should include analysis of full text and include text from the years 2010 and 2015. Also, link analysis could provide information on museums’ use of social media and outreach activities and thereby contextualise museum websites in a broader digital landscape.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Professor Niels Brügger from Aarhus University for valuable support with this project and to IT-developer Ulrich Karstoft Have from Aarhus University for data cleaning and advice during the different phases of the project. Furthermore, the authors want to thank Signe Birgit Sørensen, general manager at CALDISS (the digital data and method lab at The Faculty of Social Science and Humanities at Aalborg University) and Matias Kokholm Appel, student assistant at CALDISS for assistance with data analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mette Skov

Mette Skov is Associate Professor at Aalborg University, Department of Communication and Psychology, Denmark. She holds a master and a Ph.D. degree in Library and Information Science from the Royal School of Library and Information Science, Denmark. Her main research interests include everyday life information seeking, user studies, user experience and interaction design. She can be contacted at: [email protected].

Tanja Svarre

Tanja Svarre is Associate Professor at Aalborg University, Department of Communication and Psychology. She holds a master’s in library and Information Science from the Royal School of Library and Information Science, Denmark, and a PhD degree from Aalborg University, Denmark. Her research interests include information retrieval, information seeking, knowledge organisation, and information architecture. She can be contacted at: [email protected].

References

- Anderson, S. (2018). Visitor and audience research in museums. In I. K. Drotner, V. Dziekan, R. Parry, & K. C. Schrøder (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of museums, media and communication (1st ed., pp. 80–95). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315560168

- Axelsson, B. (2018). Online collections, curatorial agency and machine-assisted curating. In I. K. Drotner, V. Dziekan, R. Parry, & K. C. Schrøder (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of museums, media and communication (pp. 67–79). Routledge.

- Brügger, N. (2018). The archived web: Doing history in the digital age. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=1933809

- Cameron, F. R. (2008). Object-oriented democracies: Conceptualising museum collections in networks. Museum Management and Curatorship, 23(3), 229–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647770802233807

- Capriotti, P., Carretón, C., & Castillo, A. (2016). Testing the level of interactivity of institutional websites: From museums 1.0 to museums 2.0. International Journal of Information Management, 36(1), 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2015.10.003

- Chakraborty, A., & Nanni, F. (2017). The changing digital faces of science museums: A diachronic analysis of museum websites. In I. N. Brügger (Ed.), Web 25. Histories from 25 years of the world wide web (pp. 157–172). Peter Lang.

- Drotner, K., & Schrøder, K. (Eds.). (2013). Museum communication and social media: The connected museum. Routledge.

- Dziekan, V., & Proctor, N. (2019). From elsewhere to everywhere: Evolving the distributed museum into the pervasive museum. In I. K. Drotner, V. Dziekan, R. Parry, & K. Schrøder (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of museums, media and communication (pp. 177–192). Routledge, an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group.

- Fage-Butler, A., Ledderer, L., & Brügger, N. (2022). Proposing methods to explore the evolution of the term ‘mHealth’ on the Danish Web archive. First Monday, 27(1). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v27i1.11675

- Fernandez-Lores, S., Crespo-Tejero, N., & Fernández-Hernández, R. (2022). Driving traffic to the museum: The role of the digital communication tools. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 174, 121273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121273

- Gaia, G., Boiano, S., Bowen, J. P., & Borda, A. (2020, July). Museum websites of the first wave: The rise of the virtual museum [Paper presentation]. In Proceedings of EVA London 2020. BCS Learning & Development Ltd. https://doi.org/10.14236/ewic/EVA2020.4

- Grimmer, J., Roberts, M. E., & Stewart, B. M. (2022). Text as data: A new framework for machine learning and the social sciences. Princeton University Press.

- Hale, S. A., Blank, G., & Alexander, V. D. (2017). Live versus archive: Comparing a web archive to a population of web pages. In I. N. Brügger & R. Schroeder (Eds.), The web as history (pp. 45–61). UCL Press.

- Hansen, H. J., & Ødegaard, V. (1997). Guder og grave: Nationalmuseets pilotprojekt til Kulturnet Danmark. Danske Museer, 1997(2), 16–17.

- Jain, A. K. (2010). Data clustering: 50 years beyond K-means. Pattern Recognition Letters, 31(8), 651–666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patrec.2009.09.011

- Kidd, J. (2019). Digital media ethics and museum communication. In I. K. Drotner, V. Dziekan, R. Parry, & K. Schrøder (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of museums, media and communication (pp. 193–204). Routledge, an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group.

- Kizhner, I., Terras, M., Rumyantsev, M., Khokhlova, V., Demeshkova, E., Rudov, I., & Afanasieva, J. (2021). Digital cultural colonialism: Measuring bias in aggregated digitized content held in Google Arts and Culture. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 36(3), 607–640. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqaa055

- Laursen, D., & Møldrup-Dalum, P. (2017). Looking back, looking forward: 10 years of development to collect, preserve, and access the Danish Web. In I. N. Brügger (Ed.), Web 25: Histories from the first 25 years of the World Wide Web (pp. 207–228). Peter Lang.

- Lester, P. (2006). Is the virtual exhibition the natural successor to the physical?1. Journal of the Society of Archivists, 27(1), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/00039810600691304

- Lin, A. C. H., Fernandez, W. D., & Gregor, S. (2012). Understanding web enjoyment experiences and informal learning: A study in a museum context. Decision Support Systems, 53(4), 846–858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2012.05.020

- Lopatovska, I. (2015). Museum website features, aesthetics, and visitors’ impressions: A case study of four museums. Museum Management and Curatorship, 30(3), 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2015.1042511

- Ma, X., & Hu, Y. (2022). Research on the evaluation of museum website utility index based on analytic hierarchy process: A case study of China’s national first-class museums. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 37(2), 517–533. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqab073

- Mairesse, F., & Desvallées, A. (2010). Key concepts of museology, International Council of Museums. Armand Colin.

- Marty, P. F. (2007). Museum websites and museum visitors: Before and after the museum visit. Museum Management and Curatorship, 22(4), 337–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647770701757708

- Marty, P. F. (2008). Museum websites and museum visitors: Digital museum resources and their use. Museum Management and Curatorship, 23(1), 81–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647770701865410

- McCall, V., & Gray, C. (2014). Museums and the ‘new museology’: Theory, practice and organisational change. Museum Management and Curatorship, 29(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2013.869852

- Nørskov, V. (1970). Museums and museology in Denmark in the twenty-first century. Nordisk Museologi, 1(1), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.5617/nm.6400

- Parry, R. (2019). How museums made (and re-made) their digital user. In I. T. Giannini & J. P. Bowen (Eds.), Museums and digital culture (pp. 275–293). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97457-6_13

- Ross, M. (2015). Interpreting the new museology. Museum and Society, 2(2), 84–103. https://doi.org/10.29311/mas.v2i2.43

- Samis, P. (2008). The exploded museum. In I. L. Tallon & K. Walker (Eds.), Digital technologies and the museum experience: Handheld guides and other media (pp. 3–18). AltaMira Press.

- Schweibenz, W. (2004). The development of virtual museums. ICOM News, 57(3), 3.

- Simon, N. (2010). The participatory museum. Museum 2.0. Santa Cruz, Calif.

- Skov, M., & Ingwersen, P. (2014). Museum Web search behavior of special interest visitors. Library & Information Science Research, 36(2), 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2013.11.004

- Vergo, P. (Ed.). (1989). The new museology. Reaktion Books.

- Wallace, B., & Jones-Garmil, K. (1994, July/August). What will the Internet mean to museums, and what will museums mean to the Internet? Museum News, 73(4), 33–39.

- Walsh, D., Hall, M. M., Clough, P., & Foster, J. (2020). Characterising online museum users: A study of the National Museums Liverpool museum website. International Journal on Digital Libraries, 21(1), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00799-018-0248-8

- Weil, S. E. (1999). From being about something to being for somebody: The ongoing transformation of the American Museum. Daedalus, 128(3), 229–258.