Abstract

This study describes the development of a paint-based toolkit, which explored how thinking through the act of painting, colour choices and mark-making might enhance meaningful conversation. Painting methods were valuable in creatively engaging patients and staff in co-design activities and helped them consider the focus topic of what ‘care’ looked like and meant to them. As such, we illustrate how a ‘simple’ creative activity can be used to help uncover different perspectives and sense-making around a shared focus. We hope that such an approach may support people to come together to help challenge the boundaries of what insight-driven healthcare might look like.

Introduction

Designers and design researchers can aid in making positive, human-centred change through collaboration with healthcare organizations but are frequently challenged (Groeneveld et al. Citation2018). For example, tensions may arise in contexts where creativity departs from the norm (Earnshaw Citation2016). Such tensions are observed when conducting fieldwork, involving end-users, navigating sensitive situations, building understanding, establishing rapport, and communicating the value of collaborations between designers and healthcare providers (Groeneveld et al. Citation2018; Reay et al. Citation2022). This is in part due to the hierarchies, intensities, and tight resourcing of most healthcare systems (e.g. Groeneveld et al. Citation2018), and scepticism about the added value of design in health and wellbeing contexts (Nakarada-Kordic et al. Citation2020; Cunningham and Reay Citation2019). When the disciplines of design and healthcare attempt to work together, there can be a clash of worlds and paradigms (Nakarada-Kordic et al. Citation2020; Reay et al. Citation2022). Designers can feel constrained by the systems and structures of the healthcare institution and may not fully understand the demands and systems of healthcare that create prioritization (Nakarada-Kordic et al. Citation2020). Reay et al. (Citation2019) suggest that navigating complex systems to incite change as a designer requires strong well-connected, and transparent internal support.

Co-creation or co-design approaches work with end users to have positive impacts in a context relevant to them (Sanders and Stappers Citation2008). Creative practice can support sense-making (McCrary Sullivan Citation2000), with forms of analogue creativity leading to increased confidence and joy (Reynolds and Lim Citation2007). The nonverbal nature of drawing or painting can support the expression of feelings or emotions. As such, we identified an opportunity to use such approaches in healthcare-based co-design workshops—to help participants express themselves through what they make (Marshall et al. Citation2014). This study describes the development of the use of painting as a co-design method (and supporting toolkit) over the three workshops. In doing so we present the findings of workshops that explored ‘frustration’, ‘care’ and ‘joy’ in the healthcare context.

Workshop one

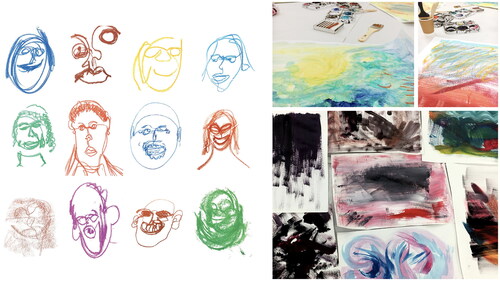

The first workshop—‘Communicating in Colour’—was part of the Design for Health Symposium 2019 (https://goodhealthdesign.com/symposium/design-for-health-symposium-workshops). There were eight participants, including a range of healthcare professionals, researchers and designers. The workshop ran over a one-hour period and, unlike subsequent workshops, was focused on giving form to a good and bad day as a way to test the workshop approach using a simpler topic. Participants were taken through a series of guided mark-making painting activities, beginning with participants drawing ‘contour portraits’ of each other (). Laughter ensued as participants observed their finished drawings, suggesting participants found it enjoyable and helpful to establish connections. It also seemed to facilitate a comfortable and safe environment for participants to share later in the workshop.

Figure 1. Images from workshop one. Contour portraits as a quick warm-up exercise where an ‘artist’ looks at a person opposite and draws the contours of what they see in one continuous line (left) while not looking at their paper. Participants’ paintings using colours to represent ‘a good day’ (top right) and a bad day (bottom right).

Next, a scene-setting exercise invited participants to close their eyes as they were guided to reflect on a recent time when they had experienced a good day. After opening their eyes, participants were asked to choose colours that reminded them of that day. They were then given ten minutes to create marks on the paper that emulated the energy of that good day. Following this, participants were invited to talk about their painting and what it represented. Once the first participant had shared, more participants became eager to share their stories. There was a positive energy in the room as people smiled and laughed. The paintings were generally brightly coloured with brush strokes that alluded to waves or felt ‘energetic’ (). The same exercise was repeated for a ‘bad day’ (). It was interesting (although not surprising) to see most participants reach for dark, dull colours such as black, grey and dark blue.

Reflection on workshop one

Several differences were observed between participants. For example, it took some longer than others to make any marks on their paper or to choose a starting colour. One participant was hesitant from the outset, saying they were ‘never good at art at school’ and had not painted since childhood. This seemed a difficult barrier to break through, despite reassurance that judgement (on artistic ability or any other criteria) was not the focus. Another participant expressed that they thought the workshop sounded ‘childish to begin with’, but after seeing the reaction from the exercises, suggested that it was ‘good for adults to do’. It was suggested that a final exercise could address a question or issue that needed resolving. However, it was also recognized that this would require more discussion time than what was available in this first session.

This first workshop highlighted the importance of making clear at the beginning of the workshop that the purpose of painting was to participate in a process that stimulated discussion. Participants were asked for feedback on the workshop to improve the process. Feedback was generally focused on the more practical aspects, as unpacked in .

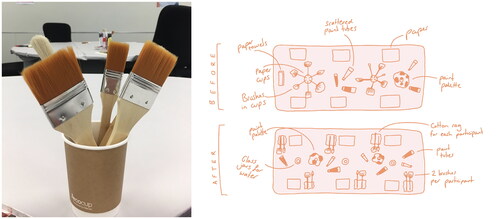

Figure 2. Improvements after the first workshop included paper cups filled with water for washing brushes that were too flimsy, small for larger brushes and were easily knocked over (left). These were replaced with larger recycled glass jars and could be shared between two participants. Layout changes to workshop table (right). Originally paint brushes were placed in the Middle of the table resulting in participants not knowing which to choose. Subsequently, a range of brushes were provided to each participant. Paint colours (primary) were initially limited, and few participants mixed their colours. A greater range of colours was subsequently provided, and mixing colours was encouraged. Initially, multiple sheets of paper were given at the start, but these became damaged during the exercises, so the paper was given out as needed. The paper towels used for cleaning (e.g. brushes) disintegrated easily and were replaced by absorbent cotton rags.

Workshop two

The second workshop occurred at The Design Space based at North Shore Hospital. This session was part of Making Methods (2020), a research-based event hosted by Good Health Design (https://www.goodhealthdesign.com/making-methods). Being part of an event with other creative co-design workshops meant a wider participant outreach, including hospital staff. The space was designed to be light and welcoming for participants, and two tables were set up with the improved painting toolkit (). The workshop consisted of five stages outlined below and was focused on notions of joy, frustration and care.

Figure 3. Revised painting toolkit set-up used in the second workshop (left). Joyful moments are being painted by participants in the second workshop (right).

Explain

Improvements to the workshop plan included a more succinct talk to begin, with participants briefed on the facilitator’s background, the research aims and what they did not need to worry about (e.g. being an experienced painter or what the final painting looked like). The workshop was attended by various healthcare professionals, corporate staff and designers (n = 8). It was made more explicit that the activities were a process of thinking through colour and mark-making, giving visual form to their thoughts and feelings. This second workshop was 90 min in duration, allowing more time for the visualization stage.

Visualize

Participants were asked to close their eyes while thinking about a specific moment that felt joyful. With their eyes closed, they were asked:

Where were you during this moment?

What could you feel?

What were you standing/sitting on?

What were you or others around you wearing?

What could you smell? Or taste?

What did it sound like?

What was it about this moment that was so joyful?

These questions aimed to help participants generate a rich image in their minds, encouraging them to think beyond surface-level memory.

Create

Following the visualization stage, participants were encouraged to paint what they felt during that moment rather than a direct image of the scene. The facilitator talked about what the energy of a brush stroke might look like (i.e. slow or fast, soft or hard) and how that might help to portray a feeling. Mixing colours to achieve new hues was encouraged. To avoid a sense of being ‘watched or judged’, the facilitator also participated in the activity. This helped to reduce the power dynamic as the facilitator became an ‘active participant’.

Share

After 10 min, the participants transferred their paintings to a new table to observe them in a ‘clean’ environment. Standing in a circle around the table helped to create an inclusive space where everyone could see the paintings and helped shift mindsets from ‘creating’ to ‘sharing’.

Question

Participants were then invited to unpack what ‘care’ meant to them.

Reflection on workshop two

Similar to the first workshop, the notion of painting initially appeared to be confronting to participants. They seemed hesitant when reaching for brushes. However, when it was reiterated that there was no need for prior painting experience, they more easily relaxed into the activity. Participants seemed to hold onto a feeling of being judged for what they created in the first exercise. One participant said, ‘my adult brain is getting in the way’. There was a sense that it is harder for adults to open up to creative activities and free their thoughts in a visual way.

Participants hesitated when invited to share their paintings and their meanings. After a period of waiting, the facilitator offered their own story, which led others to share. Participants recalled considerable detail about often small and fleeting moments of joy (e.g. the colour of clothes, the weather, details of the environment and their innermost feelings at the time) (). Participants described that having time to think about how they would represent their thoughts through colour and mark-making helped them to build a rich narrative. Another participant suggested that ‘choosing colour for my feelings made me think in a more abstract and metaphorical way’. This subsequently made it easier to discuss in a group setting.

When participants were asked to paint about a time that had frustrated them, there was a shift in the collective mood, resulting in the facilitator needing to navigate the process with greater sensitivity. However, one participant said, ‘reflecting on a frustrating moment in this workshop really helped me appreciate the positive, joyful moment’. There was a concern that participants may bring up traumatic memories or cause others to feel upset or uncomfortable. However, trust within the group meant that many were willing to share their ‘frustrating moment’ paintings. The subsequent conversation was empathetic and sparked further discussion about why certain colours and marks were chosen to represent such times. Participants who were in clinical roles in the hospital suggested that this workshop would be beneficial for new staff working in a hospital to see how they thought creatively, gain insight into what ‘care’ meant to them, and get to know each other better as individuals. One clinical role participant commented that everyone was ‘on the same level’. Rather than being there ‘in your staff role, the painting made everyone feel carefree and like themselves, rather than their “work-selves”’. Finally, it was suggested that talking about a joyful moment was a good insight into what someone valued and helped to build a greater connection with them.

Workshop three

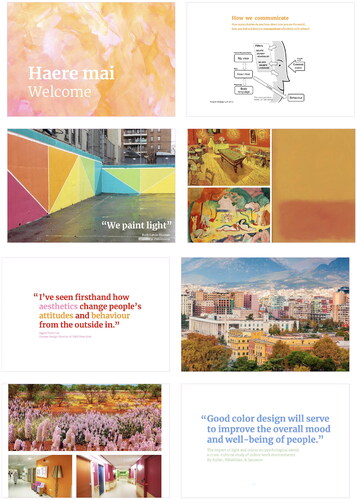

The third and final workshop took place at St Paul Street Gallery as a second workshop event as part of Making Methods (). Many people may be more familiar with visiting art galleries as an observer rather than as a participant. The session plan followed the structure of workshop two with the addition of visual PDF slides shown on an iPad during the workshop to help more effectively communicate the purpose and process of the workshop (). This allowed participants (n = 9) to see the workshop stages; explain, visualize, create, share, and question. They also helped the facilitator manage the workshop (timing) and helped them move easily from one activity to the next.

Reflection on workshop three

Like previous workshops, some participants expressed apprehension during the ‘explain’ phase. One participant commented that it felt like they had ‘signed up’ for a childish activity and that their ‘adult way of thinking’ was getting in the way. Similar comments were made in previous workshops, suggesting a barrier commonly felt by participants. This highlights the importance of the facilitator communicating the expectations of sessions, with an emphasis on ‘play’ and ‘serious fun’, and that the process of painting was an act of deep thinking, remembering and synthesizing. One participant said, ‘this was challenging to start because I haven’t painted in such a long time. I didn’t know what I was doing. But after I realized it wasn’t about the end result and we just had to use it to capture our thoughts I was fully on board’. There was less conversation than observed in workshop two during the ‘share’ phase. This may be due to several factors, such as the unfamiliarity of participants with each other, the environment or a lack of resonance with the activity. With the help of painting to prompt conversation, participants found it easier to put words to their thoughts on the non-tangible concepts of joy, frustration and care. During the ‘questioning’ phase, the process was more comfortable when asking participants what ‘care’ meant to them. Consequently, participants shared generously with deep insights into how care differed between home and in healthcare environments, and they expressed personal memories associated with care. Finally, it was commented by two participants that the workshop would be an engaging way to help students think about how they felt at certain times before having to talk about this.

Findings

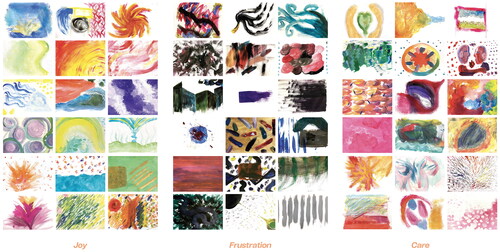

Over the three workshops, there were a total of 25 participants (clinicians, designers and members of the public). The three affective orientations explored through painting were ‘joy’, ‘frustration’ and ‘care’, and what a ‘good’ and ‘bad’ day felt like. There were similarities in how people expressed what joy made them think of and how they perceived care (). Words such as ‘warmth’, ‘soft’ and ‘love’ were used across the joy and care explorations, while specific memories, or associations, considered nature, harmony and freedom. However, the shared moments differed, with ‘joyful’ moments associated with activities, while ‘care’ moments were more holistic, encompassing, or value-orientated. While individually, the corresponding images may not mean much to anyone except their creator, clear differences (and similarities) can be seen between the representation of the three themes when viewed as a collection, both in the use of colour and mark-making techniques ().

Table 1. Overview of key words, colours and topics from the co-design workshops.

Development of a toolkit—reframing ‘childish play’ into ‘serious fun/play’

Following the three workshops, the process and activities were packaged into a painting-based toolkit called ‘Thinking Through Colour’. This toolkit incorporated the learnings from the workshops to support further research into how the act of painting, colour choices and mark-making might enhance the experience of sharing meaningful conversation in a group setting and enable creative and thoughtful discussion around a chosen topic. The materials for the toolkit are housed within a sectioned box, which acts both as a vehicle for transportation of the workshop, by packaging and branding it, legitimizes the exercise in a way that helps give confidence to participants that the activity is more than just ‘childish play’ ().

Discussion

Workshops and collaboration using design and creative methods can support feelings of ownership, ‘improved mood and social connection’ (Marshall et al. Citation2014, 755). In this study, the word ‘painting’ referred to the artistic application of paint to a surface as a vehicle for conversation (Elkins Citation2019). Fetell Lee (Citation2018, 19) argues that not only was colour a means of survival (e.g. when humans were hunter-gatherers, foraging for nutrient-rich food), it is ‘energy made visible’.

Hand-made visual art is relational. It connects the viewer to a thought or feeling, creates a connection to the experiences of others, and can inspire a different way of thinking or feeling. There is a growing awareness of the role of art-based activities in delivering healthcare, including the potential of the arts to impact positively on the health and well-being of people. Specifically, bringing the arts and co-creativity together can help unlock unexpected insights and help people safely explore uncomfortable experiences and support unique communication opportunities and sharing personal experiences (Zeilig, West, and van der Byl Williams Citation2018). This builds on the value of art therapy as a means of understanding how to support people in generative, co-creative design engagements (Lazar et al. Citation2018). Zeilig, West, and van der Byl Williams (Citation2018) suggest that while there may be therapeutic potential in using the arts, this is not the goal in the context of co-creativity.

Art therapy is an approach where clients engage artistic materials and creative processes to express their feelings, reconcile emotional conflicts, foster self-awareness, and achieve other goals, especially when they find it difficult to express their feelings verbally (Lazar et al. Citation2018). Lazar et al. (Citation2018) present insights from art therapy practice to inform collaborative design engagements. Specifically, they identify how the ‘language’ of materials influences participants’ experiences. For example, they describe how using crayons and printer paper may comfort some people while being less helpful to others who perceive these materials as not ‘serious’. In contrast, using high-quality materials (e.g. brushes and paints) may be intimidating for some, yet for others convey that their work is valuable. Sanders and William (Citation2003) suggest being ambiguous when using ‘making methods’ is preferred. Because participants can interpret activities and materials in whatever way they choose, their creativity is less limited by the sole use of words and can allow for freer expression (Sanders and William Citation2003). This informed the final design of our toolkit - we combined materials of various qualities and packaging and branding in a way considered approachable and playful yet legitimizing the seriousness of the activity.

Lazar et al. (Citation2018) explain how art therapy ‘creates a space for expression’ by setting clear expectations of outcomes and the purpose of activities, underpinned by the importance of the facilitator to communicate the importance of trusting the process and approach activities with ‘attentiveness, openness, curiosity, a non-judgmental attitude, and a sense of wonder’ (p 9). We observed that some participants found it challenging to engage with these characteristics. However, through attentiveness by the facilitator, this was usually overcome, with strategies to support engagement being iteratively developed, as previously discussed.

This is partly related to positions and perceptions of power (Lazar et al. Citation2018). Lazar et al. (Citation2018) describe how insights from art therapy into reflection on power dynamics are critical to sustaining the expression of participants, especially when individuals are confronted with their abilities and experiences as part of the process of sharing. They state that art therapists understand that power dynamics underlie the entire process of making and sharing and suggest that design teams include healthcare practitioners or professionals who are trained to work with individuals with complex communication needs.

While hospital systems and processes (particularly with respect to innovation) can be perceived as hierarchical, bureaucratic, risk-averse, cold and clinical (Jones Citation2013; Nakarada-Kordic et al. Citation2020), the ideal of person-centred care is being increasingly incorporated into healthcare practice. Despite this shift, healthcare environments and information often fail to deliver meaningful human experiences. This can partly be due to the barriers designers and other changemakers face when working within healthcare systems (Reay et al. Citation2022). Creative approaches (e.g. painting) can help reveal a situation’s experience, feeling and tone. There is potential for joyful and caring interactions within healthcare spaces to positively impact the mental and physical wellbeing of patients and staff.

This research adds to the evidence that supports that the use of creative approaches in healthcare environments may have the potential to help communicate a sense of care that parallels the care that can be offered by healthcare staff. A relational orientation in care recognizes that the relationship built between patient and clinician should be prioritized (Terry and Kayes Citation2020). This study supported this notion, where participants shared that ‘good care’ felt personal and required being treated as an individual. Reflecting on the discussions in the co-design painting workshops, it was evident that colour was a factor in expressing an emotion non-verbally or helping memories surface in one’s mind. Artistic elements such as colour and themes such as nature ‘speak directly to our unconscious minds, bringing out the best in us without our even being aware of it’ (Fetell Lee Citation2018, 9).

The findings of this study suggest that there is potential for painting-based approaches to be used to engage staff and patients to inform future healthcare design solutions and decisions. Creativity was celebrated by breaking down barriers between those with different roles to generate meaningful conversation. Through the workshops, it was possible to gain insights into what joy, frustration, and care meant to people and how these ideas looked when visualized as colours and hand-made marks. These themes could be substituted for any number of topics needing to be explored and offer a creative and enjoyable way to participate in co-design processes, showing that this toolkit is worthy of further exploration in healthcare contexts.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the participants who took part in each workshop.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Hannah Sames

Hannah Sames has always believed in the healing and explorative nature of painting. She studied Fine Art at Whitecliffe College of Art & Design, before completing a Bachelor of Communication Design at AUT. Hannah has a keen interest in understanding how art, creativity, colour and the act of painting can help as both a co-design research tool, as well as creating a positive impact on hospitals and their patients.

Stephen Reay

Stephen Reay leads Good Health Design, focussing on how the design of products and services may have a positive impact on people’s health and wellbeing.

Cassandra Khoo

Cassandra Khoo is a communication designer and researcher working at AUT’s Good Health Design. Her background is in communication design, specifically in branding and information visualization. She has an interest in using co-design to improve communication in healthcare.

Gareth Terry

Gareth Terry is a Senior Lecturer in Rehabilitation at the Auckland University of Technology in Aotearoa New Zealand. His work draws on critical health psychology and its application to a number of areas, in particular rehabilitation and disability studies. He has particular research interests in people living with chronic health conditions, men’s health, body image, reproductive decision making (particularly the decision not to have children), and masculine identities. He has methodological interests in thematic analysis, critical discursive psychology, and qualitative survey development, and has contributed to edited volumes in these areas.

References

- Cunningham, H., and S. Reay. 2019. “Co-Creating Design for Health in a City Hospital: perceptions of Value, Opportunity and Limitations from ‘Designing Together’ Symposium.” Design for Health 3 (1): 119–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/24735132.2019.1575658

- Earnshaw, R. 2016. “Creativity and Creative Processes in Art and Design.” In Research and Development in Art, Design and Creativity. Springer Briefs in Computer Science. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-33005-1_4

- Elkins, J. 2019. What Painting is: How to Think About Oil Painting Using the Language of Alchemy. New York: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Fetell Lee, I. 2018. Joyful: The Surprising Power of Ordinary Things to Create Extraordinary Happiness. New York: Little Brown Spark.

- Groeneveld, B., T. Dekkers, B. Boon, and P. D’Olivo. 2018. “Challenges for Design Researchers in Healthcare.” Design for Health 2 (2): 305–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/24735132.2018.1541699

- Jones, P. 2013. Design for Care: Innovating Healthcare Experience. Brooklyn, New York: Rosenfeld Media.

- Lazar, A., J. L. Feuston, C. Edasis, and A. M. Piper. 2018. “Making as Expression: Informing Design with People with Complex Communication Needs through Art Therapy.” CHI 2018, April 21–26, 2018, paper 351, 1–16. Montréal, QC, Canada.

- Marshall, K., A. Thieme, J. Wallace, J. Vines, G. Wood, and M. Balaam. 2014. “Making Wellbeing: A Process of User-Centered Design.” In Proceedings of the Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, 755–764. New York: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2598510.2600888

- McCrary Sullivan, A. 2000. “Voices inside Schools – Notes from a Marine Biologist’s Daughter: On the Art and Science of Attention.” Harvard Educational Review 70 (2): 211–227. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.70.2.x8601x6tn8p256wk

- Nakarada-Kordic, I., N. Kayes, S. Reay, J. Wrapson, and G. Collier. 2020. “Co-Creating Health: Navigating a Design for Health Collaboration.” Design for Health 4 (2): 213–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/24735132.2020.1800982

- Reay, S., C. Craig, and N. Kayes. 2019. “Unpacking Two Design for Health Living Lab Approaches for More Effective Interdisciplinary Collaboration.” The Design Journal 22 (sup1): 387–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2019.1595427.

- Reay, S., I. Nakarada-Kordic, N. Kayes, C. Khoo, and C. Craig. 2022. “Initiate.collaborate: A Design for Health Collaboration Toolkit.” Design for Health 5 (3): 294–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/24735132.2022.2045091

- Reynolds, F., and K. H. Lim. 2007. “Contribution of Visual Art-Making to the Subjective Well-Being of Women Living with Cancer: A Qualitative Study.” The Arts in Psychotherapy 34 (1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2006.09.005.

- Sanders, E. B.-N., and P. J. Stappers. 2008. “Co-Creation and the New Landscapes of Design.” CoDesign 4 (1): 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1571088070187506

- Sanders, E. B.-N, and C. William. 2003. “Harnessing People’s Creativity: Ideation and Expression through Visual Communication.” In Focus Groups, edited by J. Langford and D. McDonagh, 145–156. London, England: Taylor & Francis.

- Terry, G., and N. Kayes. 2020. “Person Centered Care in Neurorehabilitation: A Secondary Analysis.” Disability and Rehabilitation 42 (16): 2334–2343. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1561952

- Zeilig, H., J. West, and M. van der Byl Williams. 2018. “Co-Creativity: possibilities for Using the Arts with People with a Dementia.” Quality in Ageing and Older Adults 19 (2): 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAOA-02-2018-0008