ABSTRACT

Following the tragic sinking of the Sewol Ferry, there was a significant increase in the prosecution of criminal cases involving ship surveyors and their professional responsibilities. In 2015, the Ship Safety Act of Korea introduced new Paragraphs 13-2, 13-4, and 13-5 in Article 83. These amendments aimed to penalize individuals who engage in fraudulent or improper practices during surveys. It classified such actions as a serious offense. Accordingly, the elements of the crime of interference with business in criminal law have become less complex and easier to prove.

Given that ship surveyors were already legally liable for obstructing business activities under the Criminal Act before the implementation of this provision, it is necessary to assess whether the existing legislation allows for disproportionate penalties.

This study aimed to assess the validity of legislative principles, including the constitutional proportionality principle, the violation of legalism in criminal law, the limitations of dangerous criminal law, and the issue of overcriminalization.

We conducted a comparative review of laws and assessed their potential impact on the industry through an online questionnaire distributed to ship surveyors and professionals in related fields. As a result, we proposed amending the related penalty provisions of the Act.

Introduction

According to the Ship Safety Act of Korea, the ship inspection system assumes a pivotal role in ensuring the seaworthiness of vessels, thereby upholding the safety of life and safeguarding property on board during navigation. The implementation of regular inspections and ongoing maintenance practices ensures the preservation of the ship’s overall condition. The stated objective is to ensure the safe navigation of vessels and reduce the occurrence of maritime accidents (I. C. Kim et al., Citation2023; Y. C. Lee et al., Citation2011).

The process of ship inspection, as mandated by the Ship Safety Act, encompasses three primary components. Firstly, a conformity assessment is conducted on technical regulations pertaining to the design, production, and management of structural, mechanical, and electrical components of ship facilities. This assessment is undertaken to ascertain the seaworthiness of the vessel. Secondly, the safety of the ship necessitates the approval and confirmation of various technical matters, in addition to ensuring its seaworthiness. Thirdly, it is recommended that random and voluntary inspections for public interest be carried out by a government-approved agency, commonly referred to as a Recognized Organization (RO) (S. L. Lee et al., Citation2019).

The practice of ship inspection can be traced back to the 15th century, during which insurance companies started requiring inspections to assess the seaworthiness of ships for voyages at sea (I. C. Kim et al., Citation2023; KST et al., Citation2003). The implementation of governmental supervision in the domain of ship inspection and survey can be ascribed to the disastrous sinking of the Titanic in 1912 (KST et al., 2003). The Titanic commenced its maiden voyage from Southampton, UK, destined for New York, USA. The vessel encountered a collision with drifting ice in the waters of Newfoundland in the North Atlantic during its voyage, resulting in its sinking at 02:20 local time on 15 April 1912, approximately 2 hours and 40 minutes after the incident took place (UK Court of Formal Investigation, Citation1912).

In the tragic accident, there was a loss of life, with a total of 1,490 individuals perishing. The event holds great historical importance in the realm of maritime history, except for incidents that occurred during times of war. The incident brought attention to various concerns, including the lack of a reliable distress notification system, insufficient life-saving equipment, and the necessity for enhancements in the watertight compartments and bulkheads of vessels (KST et al., Citation2003).

The British government investigated the Titanic accident, and as a result, an international conference on maritime safety was held in London in 1913, with participation from 13 countries. Various other issues were also discussed during the conference. As a result of that effort, the 1914 International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS Convention) was adopted. The 1914 SOLAS Convention incorporated numerous classification rules of the era, and to this day, classification societies play a significant role in the development and updating of international maritime conventions.

In order to fulfill the government’s inspection responsibility, some countries conduct ship surveys or inspections directly according to the inspection item, while others delegate this responsibility to specialized agencies. Therefore, the mandatory inspections mandated by the Ship Safety Act could overlap with the classification survey carried out by ROs. Additionally, there exists a notable convergence between inspections that were voluntarily carried out in the private sector even prior to government intervention.

Classification survey is a type of inspection that is undertaken voluntarily, driven by both public interest and private regulations. The aforementioned phenomenon, known as the public normativity effect, gives rise to the misconception that successfully passing the classification inspection, as per both international conventions and national laws, is tantamount to passing the mandatory inspection conducted by the government (a legal fiction). As acknowledged, it functions as a conduit through which the governmental oversight authority collaborates with private institutions in a crucial cooperative manner (S. L. Lee et al., Citation2019).

Each ship surveyor concurrently fulfills the responsibilities of government inspection, international agreement inspection, and private inspection. As a consequence, the inspection carried out by the surveyor frequently replicates the commercial vessel inspection performed by the ship owner and shipper. Therefore, the implementation of individual punishment or an individual surveyor responsibility system in the event of a ship accident is a proposition that is considered highly risky and challenging to align with the concept, characteristics, and legal framework of ship inspection (S. L. Lee et al., Citation2019).

An accident in Korea led to significant changes in the punishment protocols for ship surveyors. At approximately 8:49 am on 16 April 2014, the bow of the Sewol Ferry suddenly veered to the right, causing the ship to tilt to the left. The vessel experienced a rapid and substantial tilt of more than 45 degrees to the port side within a brief time frame (Sewol Ferry Hull Investigation Committee, Citation2018). At 10:30, 101 minutes elapsed, resulting in the submersion of only the bow in the water. According to the Korea Maritime Safety Tribunal (KMST), a total of 476 individuals, including passengers, were on board during the accident. Out of these, 172 individuals were successfully rescued, while tragically, 295 people lost their lives. Among the deceased were 246 students, 9 teachers, 40 members of the public, and crew members. Additionally, 9 individuals remain missing (Korea Maritime Safety Tribunal, Citation2014). In an extensive search operation that persisted until 11 November 2014, the whereabouts of the five individuals who went missing were never discovered (KBS, Citation2014).

Extensive inquiries, research, and deliberations have been conducted to ascertain the root cause of the accident, and the Sewol Ferry accident has brought about substantial transformations in Korean society.

If a maritime accident takes place on a vessel that has been inspected by a ship surveyor subsequent to the Sewol Ferry accident, the ship surveyor may be subjected to an investigation by a law enforcement agency with regards to the ship inspection report that was produced. Furthermore, it is possible that the ship surveyor could face legal consequences for obstructing business operations, potentially leading to the imposition of criminal penalties. The frequency of documented cases is on the rise (Seo, Citation2022).

Prosecution may be pursued in the following situations: 1) when a safety defect is found, 2) when any aspect of the inspection report for the inspected vessel reveals an issue, or 3) even if a direct connection or causality with the accident is not recognized, prosecution can still be initiated.

In connection with the Sewol Ferry accident, the ship surveyor has been charged with obstruction of business as a result of their failure to carry out a thorough inspection of the vessel before the incident occurred. In a five-year trial, the ship surveyor was acquitted in the initial and subsequent trials, however, was ultimately convicted by the Supreme Court in May 2019 (Park, Citation2019).

It has been alleged that the ship surveyor prepared the document without conducting a comprehensive analysis of its contents. The lower court and the Supreme Court have issued a decision regarding the categorization of this action as either a “falsehood or an intentional act” or not. However, it is important to note that the ruling was issued in direct contradiction.

Both the initial and subsequent trials acknowledged the deficiencies in the writing of the inspection report. However, these deficiencies were not be construed as a deliberate hindrance to the inspection work conducted by the RO as a collective entity. On the contrary, the recognition of deliberate hindrance of business operations by the Supreme Court, although not fully implemented, has been acknowledged (S. L. Lee et al., Citation2019).

The primary issues in this case revolve around the inadequate execution of inspections during the expansion and reconstruction of the Sewol Ferry between 2012 and 2013. Additionally, there were deficiencies in the preparation and reporting of inspection reports and checklists. 3) The confirmation of the tank capacity, weight, and location of items to be loaded and relocated upon completion of the ship was not conducted during the supervision of the Sewol Ferry incline test. 4) The actions undertaken by the shipping company, such as modifying the entrance door to the passenger compartment and constructing substantial structures in exhibition facilities, were not subjected to inspection to ensure their conformity with the provided drawings.

The negligence of the ship surveyor in conducting the inspection was characterized by the Supreme Court as “falsely generating a test outcome as if it had been directly confirmed, despite the fact that it had not been (Supreme Court of Korea, Citation2018).”

If this is the case, a number of inquiries may arise as outlined below:

So, does the ship surveyor have a legal obligation to personally verify and confirm all items without exception? Should legal liability be imposed in cases where factual information is inaccurately presented as a result of error or negligence? How should an surveyor be punished if he or she makes a serious mistake in interpreting rules, regulations or standards and conduct a faulty ship inspection?

Should the surveyor be held accountable under the law for “fabricating a false result report” if only a few items on the checklist are selected and inspected intensively due to time limitations, while the rest are deemed satisfactory based on the shipping company’s previous safety record, and all are marked as problem-free?

Will ship surveyors be required to undergo investigation as potential suspects in the event of future ship accidents?

After the Sewol Ferry accident, there was an increase in the number of criminal cases involving ship surveyors and their work-related inspection activities. And in 2015, Article 83, Paragraphs 13–2, 13–4, 13–5 of the Ship Safety Act was additionally introduced as shown in (KG, Citation2015).

Table 1. Amended and related provisions of the Ship Safety Act.

Article 83(13–2) of the Ship Safety Act, newly established in 2015 in response to public opinion yearning for a “safe society” after the Sewol Ferry accident, stipulates that anyone who conducts an inspection through false or fraudulent methods will be punished as a serious crime. In light of the aforementioned, it can be observed that the criteria for establishing a crime and the burden of proof are less complex in comparison to those for obstructing business operations as stipulated in the Criminal Act. Consequently, ship inspections, which are considered public acts aimed at ensuring maritime safety and environmental protection, are susceptible to criminal prosecution and subsequent penalties at any given time.

Considering the national importance of ship inspection operations, which encompass the rights and obligations of citizens, it is generally advisable to disallow private delegation or agency participation. In actuality, however, ship inspections are commonly conducted by personnel affiliated with either private entities or public institutions, depending on the specific operational needs.

Given the unique characteristics of the ship inspection system, it is imperative to evaluate, before reaching a legal verdict, the desirability of establishing precedents for criminal punishment and provisions for individual surveyors as a normative framework.

With the rapid advancement of science and technology, the general public has gained access to various conveniences. However, this progress also brings inherent risks. In this context, the legal domain, which serves as a social policy to safeguard the public, should not solely rely on insights to determine responsibility. Instead, it should be based on a comprehensive understanding of accurate science and technology. The current state of affairs necessitates a thorough understanding of science and technology as an essential prerequisite.

In the domains of nuclear energy, medical care, aviation, and ship operation, the determination of legal interests can be effectively achieved through the application of the substantial causality relationship theory. This theory establishes the likelihood of a particular outcome based on general life experience, serving as the existing framework for assessing the consequences of legal interest infringement. In this specialized technical field, where subjective judgment is not applicable, there is a need to review the appropriateness of punishment provisions for experts.

Article 83(13–2) of the Ship Safety Act, which was implemented in response to the Sewol Ferry accident, has been associated with adverse consequences. These factors encompass the psychological stress experienced by ship surveyors, the heightened rigidity in their inspection behavior, the inconvenience caused to customers such as ship owners and shipyards, and the multitude of issues encountered in inspection practices (S. L. Lee et al., Citation2023). Since there are survey results that show that it is causing not a few obstacles, we plan to study whether there is room for legislative improvement through a feasibility review.

Punishment cases involving surveyors of ships and similar safety inspection occupations

Cases of punishment for ship surveyors

Judgment of Sewol Ferry accident

In relation to the sinking accident of Sewol Ferry, the prosecution indicted the surveyors of the Korean Register of Shipping (KR) who conducted regular inspections of the Sewol Ferry on charges of obstruction of business under the Criminal Act.

The case was acquitted in both the initial trial and the subsequent appellate trial (Gwangju District Court, Citation2015).

The primary factor contributing to the acquittal is the inadequate inspection conducted by the KR surveyor on the remodeled ferry ship, particularly in certain areas where direct verification was not performed. However, it is important to note that there was a failure to recognize this negligence as an intentional act of falsification, and there was a potential risk of impeding business operations once the falsification was acknowledged. The surveyor was acquitted based on the argument that the presence of intentionality could not be conclusively established.

Dissatisfied with the verdict of the second trial, the prosecution filed an appeal with the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court issued a remand subsequent to the reversal of the original trial. This decision was made based on the ship surveyor’s alleged intention to disrupt business operations by engaging in fraudulent activities that obstructed the performance of their duties (Supreme Court of Korea, Citation2018).

Sinking of M/V Stella Daisy

This maritime accident took place in 2017 when the vessel sank in the South Atlantic while en route to Qingdao, China. The ship had loaded approximately 260,000 tons of iron ore from Brazil prior to its departure. The vessel underwent its annual inspection in 2016, which was carried out by KR.

The trial court initially concluded that merely acknowledging the defendant’s role as a classification surveyor who had conducted a fraudulent inspection in contravention of the applicable regulations was insufficient grounds to find him guilty, resulting in a verdict of not guilty. Similarly, the appellate court also concluded that there is insufficient evidence to establish that the defendant deliberately neglected the inspection of the ship.

The Supreme Court further rejected the prosecution’s appeal, asserting that the original trial did not commit any errors in its application of the legal principles pertaining to the infringement of the Ship Safety Act. In consideration of the pertinent legal principles and documentation, the Supreme Court conducted a review to determine if the original trial’s verdict contravened the rules of logic and experience, surpassed the boundaries of the principle of free evaluation of evidence, or violated Article 83(13–2) of the Ship Safety Act. It has been ascertained that there were no errors that had an impact on the judgment, such as a misinterpretation of the legal principles (Supreme Court of Korea, Citation2017).

BV classification society

Bureau Veritas (BV), a French classification society, has been granted inspection rights by the Korean government since 2017 and has been carrying out government inspections on its behalf.

It is well-established that, in contrast to the KR, there have been no instances of criminal investigation, prosecution, or criminal litigation resulting from ship safety accidents involving surveyors from BV. However, BV Korea is a corporate entity that was founded in the Republic of Korea. The delegation of inspection rights by the Korean government to the French Register of Shipping has taken place. The surveyors who are affiliated with the Ship Safety Act are currently engaged in conducting inspections. It is important to note that these surveyors are also liable to face potential criminal prosecution under Article 83 of the Ship Safety Act at any given point in time.

Punishment of surveyors from KOMSA

The Korea Maritime Transportation Safety Authority (KOMSA) is a government-established private organization that has the primary responsibility of inspecting small ships and fishing boats.

A significant number of ship surveyors employed by KOMSA face legal action as a result of allegations that they have hindered business operations during the course of conducting ship inspections. The predominant result entailed either the imposition of a monetary fine or the temporary suspension of the execution. To this day, there have been no reported cases of documented punitive actions taken for obstructing business operations under the Criminal Act. Additionally, there is no documented evidence of the application of Article 83(13–2) of the Ship Safety Act. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that a significant proportion of vessels that fall under the jurisdiction of the Fishing Vessel Act are subject to routine inspections. Although no convictions have been made under Article 83(13–2) of the Ship Safety Act, it is still possible to obtain a conviction for obstruction of business. Furthermore, Article 83(13–2) of the Ship Safety Act has simpler conditions and is easier to establish as a serious offense. By classifying ship surveyors as potential serious offenders, there is a notable sense of apprehension being instilled in KOMSA surveyors as they fulfill their responsibilities (S. L. Lee et al., Citation2023).

A comparative analysis of punishment cases for obstruction of business during inspections in the transportation sector

It is noteworthy that there is a scarcity of instances where surveyors responsible for inspecting aircraft or automobiles have faced disciplinary action for impeding business operations or obstructing official duties, in contrast to the situation observed with regard to ships. After the occurrence of the Sewol Ferry accident, there has been a growing concern regarding the equitable imposition of an excessively stringent duty of care on ship surveyors in comparison to other modes of transportation, as well as subjecting them to severe criminal penalties (Seo, Citation2022).

provides a comprehensive overview of safety inspection regulations and the corresponding punitive measures that apply to different modes of transportation.

Table 2. Cases involving the imposition of penalties for impeding transportation-related business operations.

Automobiles, airplanes, and ships all have in common that they are modes of transportation machinery connected to science and technology, which involve risks. Workers in all industries are assigned a duty of care based on abstract negligence and are therefore held accountable within the legal system. Nevertheless, the issue lies in the fact that instances of punishment for obstructing business are primarily focused on ships, which significantly undermines the fairness of the criminal justice system.

A comparative analysis of punishment provisions for safety inspections in comparable occupations

Construction, firefighting, electricity, etc

In the context of overseeing construction projects, pertinent legislation encompasses the Construction Technology Management Act, Building Act, Housing Act, Fire Protection Act, Electric Power Technology Management Act, and Information and Communication Construction Business Act.

In the context of building supervision, individuals may be subject to a maximum prison sentence of two years or a fine not exceeding 200 million won. In the case of fire supervision, the penalties are imprisonment of not more than 1 year or a fine of not more than 10 million won. These sentences are of a lower magnitude when compared to those stipulated in the Ship Safety Act.

In the case of housing supervision, a fine of up to 5 million won is prescribed. In the context of residential inspection, a penalty of up to 1 million won is stipulated, and only administrative measures are enforced.

In the Construction Technology Promotion Act, there are no provisions for punishing false inspection or supervision related to construction engineering business operators. This implies that in the event of intentionally inaccurate demand forecasts causing damage to the ordering agency or lack of faithful work resulting in damage to important facilities, the Act does not specify any specific penalties. If a fatal accident occurs, imprisonment is imposed.

Article 83(13–2) of the Ship Safety Act differs significantly from the requirements of the Construction Technology Promotion Act in that the act of conducting a false inspection is considered a criminal offense.

Cases involving comparable traffic-related legislation

Other laws similar to the punishment provisions of the Ship Safety Act include the Water Leisure Safety Act, the Aviation Safety Act, and the Automobile Management Act. In Article 59 (Fines) of the Water Leisure Safety Act, Paragraph 1, “A fine for negligence not exceeding 1 million won will be imposed on any person who conducts a safety inspection that is different from the facts intentionally or through gross negligence.”

Paragraph 4 of Article 166 (Fines) of the Aviation Safety Act states, “A fine not exceeding 2 million won shall be imposed on any person who performs work related to the operation or maintenance of aircraft without complying with the regulations for operation or maintenance.

Article 80 (Penalty Provisions) of the Automobile Management Act stipulates that “any person who illegally conducts a vehicle verification, vehicle inspection, periodic inspection, comprehensive inspection, or taximeter test, and any person who provides or expresses an intention to provide property or other benefits to them and undergoes an illegal verification, inspection, or test shall be punished by imprisonment for not more than two years or by a fine not exceeding 20 million won.”

The summarized information can be observed in .

Table 3. Comparison of punishment regulations for safety inspections in similar occupations.

Discussion

When comparing and analyzing laws related to building management and transportation, it becomes evident that the ship safety law is excessively punitive, to the extent that it contradicts the principle of proportionality.

In other legislative examples, it is difficult to find cases in which violations of certificate issuance are punished in the same way as false inspections. The Automobile Management Act includes provisions for criminal sanctions, including the possibility of imprisonment for a maximum period of two years. However, in reality, sanctions are imposed through administrative measures, such as fines for negligence and cancellation of business suspension.

The Water Leisure Safety Act specifies that a fine of less than 1 million won may be imposed if a safety inspection is conducted inaccurately. Despite belonging to the same category of vessels, the Ship Safety Act imposes a severe penalty of up to 3 years for a serious offense, whereas the Water Leisure Safety Act only entails the imposition of a fine. There exists a notable disparity in the imposition of sentences.

Ships are commonly regarded as being more akin to aircraft rather than automobiles in terms of their size and functionality. Aircraft, much like ships, undergo comparable levels of management and supervision throughout their lifecycle, encompassing process management and test operations, starting from the design phase and extending to the manufacturing phase.

The level of risk associated with an aircraft accident is similar to that of a ship accident. Nevertheless, the Aviation Safety Act stipulates that individuals who fail to adhere to the maintenance regulations may be subject to a fine of up to 2 million won for engaging in maintenance activities.

The Aviation Safety Act stipulates relatively lenient penalties, including a maximum fine of 2 million won, for unlawful activities associated with the examination of manufactured aircraft. The Ship Safety Act, on the other hand, imposes a penalty of imprisonment for a maximum duration of three years for such offenses. This statement suggests that there is a discrepancy in the treatment of comparable offenses, which is in conflict with the fundamental legal principle that “similar cases should be treated in a similar manner, while different cases should be treated differently.” Moreover, this inconsistency contradicts the Constitutional Principle of Equality.

In the context of automobiles, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport has enhanced the use of administrative penalties for deceptive inspections carried out by private inspection laboratories, as opposed to imposing criminal sanctions of less than two years. Additionally, the organization is implementing a strategy to ensure consistent quality control in inspections by implementing a regular detection system and evaluating the competency of surveyors.

This aspect can be deemed as highly significant since it advocates for an administrative approach that prioritizes guidance and education, rather than a punitive stance, as stipulated in Article 83, Paragraph 13–2 of the Ship Safety Act.

Overseas cases on the immunity and punishment of ship surveyors

Most countries that are members of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) have ratified the SOLAS Convention. As a result, there is an obligation to adhere to the RO Code (Code for Recognized Organizations) and the III Code (IMO Instruments Implementation Code).

The RO Code stipulates that the flag state government can delegate authority to an organization recognized as complying with the provisions of the Code to perform statutory certificates and inspection-related services under international conventions and domestic laws.

The purpose of the III Code stipulates that each government is responsible for promulgating laws and taking all measures in accordance with the general requirements of the IMO Convention for maritime safety and protection of the marine environment. Part 2, Article 18 stipulates that the flag state government should accredit recognized ship inspection agencies in accordance with the requirements of relevant international conventions and ensure that the recognized ship inspection agencies have adequate technical, managerial, and research capabilities.

The maritime sector exhibits international interconnectedness through the establishment of international agreements and the adoption of similar legal contents. Given the international nature of ship-related laws, such as maritime law and international maritime law, it seems crucial to employ a comparative approach in studying the punitive measures applicable to ship surveyors.

Exemption provisions for ship surveyors have been implemented in countries such as the Bahamas and Canada. Accordingly, occurrences of criminal punishment are infrequent. This phenomenon can be attributed to the administrative approach adopted by the organization, which places a higher emphasis on providing guidance and education rather than relying solely on punitive measures.

The Bahamas

The Bahamas, recognized as one of the countries of open registry, has enacted a domestic legislation that provides ship surveyors with a specific exemption from liability.

Article 275 of the Bahamas Merchant Shipping Act grants individuals engaged in state affairs pertaining to maritime affairs immunity from legal actions. Immunity from legal action grants victims the opportunity to pursue civil liability by means of the judicial system (Government of the Bahamas, Citation2023). This implies nonexistence and grants immunity from criminal prosecution by the relevant law enforcement agency. Therefore, irrespective of the existence of a claim for damages under substantive law, this legislative provision functions to safeguard state agencies, public officials, and individuals acting on behalf of the state from legal actions.

The aforementioned regulation pertains specifically to the inspection of government ships. Although the specific subject matter of the text does not pertain directly to government ship inspection, it is relevant to national affairs as it falls within the purview of the Bahamas Merchant Shipping Act and the Bahamas Maritime Authority Act. Therefore, this regulation holds significance in relation to national matters pertaining to maritime affairs. It is acknowledged that the aforementioned statement presents a constrained articulation of the legal principle of sovereign immunity.

Subjects exempt from lawsuits include all individuals appointed or authorized under the Bahamas Merchant Marine Act. This concept is likely to include both public officials and individuals who are delegated or authorized to act on behalf of public officials.

Under the provisions of the Ship Safety Act of the Republic of Korea, it is stipulated that individuals who hold public office, trustees of public affairs, and organizations or individuals who have been delegated or authorized to act on behalf of the state in matters related to inspection authority or inspection work are considered eligible.

The Bahamas Merchant Shipping Act and the Bahamas Maritime Authority Act govern the inspection activities of ship surveyors under the Ship Safety Act. In this particular scenario, if the ship surveyor deliberately neglects certain inspection items, there is a significant likelihood that the ship surveyor will be exempted from the protection of immunity from legal action, as this action is deemed a breach of good faith. However, even if inspection items were unintentionally omitted, the duty of faithfulness cannot be considered fulfilled when evaluating the entirety of the process involved in the action. In instances where establishing a violation is challenging, it is deemed possible that it could be encompassed by the realm of legal immunity.

The aforementioned action can be acknowledged as being performed with genuine intentions. In essence, the implementation of active immunity is evident in the context of institutions or surveyors who conducted ship inspections in a bona fide manner, without scrutinizing the presence of intention or negligence.

It has been determined that state affairs may be granted immunity from legal action if they are executed either directly or through delegation or agency. In this regard, it is evident that actions grounded on a contractual agreement between the involved parties are not susceptible to this.

There is a prevailing belief in the maritime sector that government-designated inspection agencies, such as KOMSA, KR, and BV, should be granted legal immunity for their inspection activities.

The classification inspection, which is primarily carried out for insurance purposes, is explicitly not exempted from legal action. According to Article 73 of the Ship Safety Act, it is acknowledged that vessels which have successfully undergone the classification inspection are considered to have fulfilled the inspection requirements mandated by the government. Consequently, these vessels enjoy immunity from legal proceedings. It has been determined that the content of the subject matter is in accordance with the specified scope.

Therefore, given the acknowledged public nature of classification inspection, the likelihood of criticism being taken into account in criminal punishment is significantly diminished. In various international jurisdictions, it is common for courts to frequently reject or impose limitations on the civil liability of classification societies in compensation lawsuits. Even in criminal cases, it is difficult to find cases in which criminal punishment was imposed on ship surveyors, except for the bribe crime, which protects the “non-negotiability of official duties.”

The underlying factor can be attributed to the international convention SOLAS Ch.2–1, regulation 3–1, which has been incorporated into the domestic legislation of the majority of countries that are members of the International Maritime Organization. The aforementioned article explicitly asserts that while the classification rules are privately established, they are evaluated to have taken into account the aspect of inspection, which also serves the public interest of safety.

The legal framework in The Bahamas provides protection for national public officials against civil and criminal charges. This protection is based on the principle of good faith, rather than holding officials liable based on the concepts of intent or negligence. It applies to individuals involved in the execution of state affairs, including government agency inspection agencies and surveyors. The purpose of this initiative can be comprehended as an endeavor to safeguard the organization and its operations against potential legal risks on a global scale.

In particular, the United States. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in the case of “Sundance Cruises v. American Bureau of Shipping, (US Court of Appeals, Second Circuit, Citation1993),” in a case where the application of Article 275 of the Bahamas Merchant Marine Act was a central issue. The classification corporation’s denial of civil liability was based on the recognition that this Act was not in conflict with the principles of U.S. federal law. This statement can be understood as an acknowledgment that it does not contradict the principles of equity and justice.

The immunity from ship inspection lawsuits under Bahamian law does not confer advantages to ship owners. Instead, it plays an active role in safeguarding government functions by ensuring the independence and objectivity of officials and agencies responsible for ship inspections. Despite their role as inspection entities, they tend to maintain a distant relationship with ship owners and ships. The given statement lacks clarity and does not provide any specific information regarding the topic at hand. It is evident that there is a pronounced emphasis on actively reflecting the essence of legal relationships.

Canada

In Canada, the government is responsible for the direct implementation of national ship inspections. According to Article 11, Paragraph 5, Part 1 of the Canadian Shipping Act, it is stipulated that a ship surveyor who conducts an inspection in good faith cannot be held personally accountable for any omissions, mistakes, or legal issues that may arise during the inspection. There exist provisions that delineate the exemption from liability (Government of Canada, Citation2001).

Unlike the Bahamian Merchant Shipping Act, the Canadian legislation notably distinguishes itself by explicitly safeguarding marine safety surveyors, provided that they carry out their duties in good faith. The aforementioned statement explicitly indicates the legislator’s intention to proactively safeguard the implementing entities responsible for national matters pertaining to ship safety.

In the context of Canada, the responsibility for ship safety inspections is not outsourced to the private sector; rather, it is undertaken directly by government officials. The system operates by employing inspection experts who provide management and guidance. Unlike the United States, Canada lacks its own classification society. Therefore, the professional training and management of ship surveyors is a critical matter of national importance that necessitates direct oversight by a national organization, specifically Transport Canada (Government of Canada, Citation2023).

The national task implementation organization safeguards the functions of ship safety inspection by providing immunity from lawsuits for ship inspection officials. The policy significance of safeguarding professional ship safety inspection organizations and experts is reflected in Article 11, Paragraph 5 of Part 1 of the Canadian Shipping Act.

Japan

Unlike the provisions outlined in Article 83 of Korea’s Ship Safety Act, the Ship Safety Act of Japan does not include stringent penalties for instances involving false reports pertaining to inspection activities.

However, in the event that a report is requested from other pertinent organizations responsible for overseeing legislation such as Japan’s Ship Safety Act, Marine Pollution Prevention Act, and Small Ship Registration Act, individuals who provide false reports or refuse to comply with, obstruct, or evade the reporting process may be subject to fines. Therefore, it is worthwhile to compare it with the Ship Safety Act of Korea.

In contrast to Korea’s ship safety law, Japan’s ship safety law exhibits a notable peculiarity in its legislative approach, wherein it imposes prison sentences on ship owners or captains, rather than on inspection groups or surveyors. The legal liability of ship owners has been enhanced. It is currently mandated that in the event a ship owner acquires a ship inspection certificate or temporary navigation permit through fraudulent means or other unlawful activities, they will be liable to face penalties, which may include a maximum prison sentence of one year or a fine of up to 500,000 yen. In essence, it should be noted that the Ship Safety Act in Japan lacks provisions to impose penalties on surveyors affiliated with inspection organizations who partake in unlawful inspection activities (Government of Japan, Citation2023).

In the Ship Safety Act of Japan, the sole provision pertaining to the disciplinary measures against surveyors is specifically associated with cases of bribery. If the act of bribery is acknowledged, it is deemed a grave offense according to Articles 25–71 and 25–72 of Japan’s Ship Safety Act, mirroring the stipulations outlined in the Korean Ship Safety Act.

China

Article 31 of China’s Ship Safety Inspection Rules (Government of China, Citation2023), which is analogous to Article 83 of Korea’s Ship Safety Act, outlines the procedures to be followed by the maritime management agency in the event of surveyor misconduct or abuse of power, in accordance with applicable regulations. The assumption of criminal punishment is not present.

In essence, the existing legislation in China does not provide specific guidelines regarding the duration of imprisonment for instances of misconduct, dereliction of duty, or abuse of power by surveyors. Instead, administrative measures are adopted in accordance with the relevant regulations.

In line with the principle of administrative disposition, Article 63 of the Ship Safety Management Regulations does not prescribe criminal sanctions, even in situations where a ship surveyor’s subjective intention leads to a serious accident or defect on a ship (Government of China, Citation2023). It has been discovered that the determination of the level of administrative sanctions is contingent upon the provision that the qualifications of ship surveyors can solely be suspended.

Common law states and major maritime states

Like Japan and China, common law countries or Commonwealth countries such as the UK, US, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia lack specific provisions in their relevant regulations for penalizing prosecutorial misconduct. Nevertheless, there exist provisions for the imposition of penalties in instances where inspections are carried out unjustly as a result of bribery or other forms of corrupt practices.

With the exception of instances involving criminal liability, such as bribery, surveyors employed by foreign classification societies are generally not subjected to criminal responsibility for their inspection activities. The application of rules in a flexible manner, in accordance with technological advancements, has become a customary practice, facilitating the utilization of innovative inspection techniques. The development of this project is ongoing.

In the United States, the regulations pertaining to ship inspection can be found in Title 46 of the United States Code, specifically in Part B (Inspection and Regulation of Vessels). This section of the code encompasses detailed regulations on ship inspection, spanning from Chapter 31 to Chapter 47. Although the United States does not have a specific legal provision that explicitly exempts classification societies from liability, there is a precedent that denies the liability of classification societies under Article 275 of the Bahamas Merchant Shipping Act.

In the Sundancer Case, following the ship accident, the shipowner provided compensation for both the material and personal damages incurred. Subsequently, the shipowner proceeded to file a claim against the classification society, seeking damages resulting from either tort or breach of contract (US Court of Appeals, Citation1993).

The U.S. 2nd Circuit Court, also known as the Federal Court of Appeals, has issued a ruling recognizing the right to seek compensation for personal injury in cases of tort liability. However, the liability of the classification society was not established as it invoked the exemption provisions outlined in the Bahamas Merchant Marine Act (I. H. Kim, Citation1996).

The American Bureau of Shipping claimed that, in accordance with Article 275 of the Bahamas Merchant Shipping Act, it was immune from any responsibility resulting from safety inspections carried out on Bahamian flag vessels on behalf of the Bahamian government (I. H. Kim, Citation1996). The ruling of the New York District Court on 31 July 1992, absolved the American Register of Shipping from any liability, a decision that was subsequently upheld by the Second Circuit on 15 October 1993. In April 1994, the appeal against the existing ruling was dismissed by the U.S. Supreme Court, which asserted that there were no jurisdictional or constitutional concerns.

In highly developed shipping jurisdictions such as the United Kingdom, there is no equivalent explicit exemption system similar to Article 275 of the Bahamas Merchant Shipping Act or Article 11, Paragraph 5 of Part 1 of the Canadian Shipping Act. In representative common law states like the United Kingdom and the United States, there exist legal precedents that provide protection to classification societies and surveyors who act as government surveyors, shielding them from civil liability in relation to ship inspections.

It remains uncertain whether there exist other jurisdictions, such as the Bahamas, that offer legal protection against lawsuits for individuals engaged in matters of national significance. In contrast to developed countries or major shipping states, the national organization and quantity of public officials in the country are insufficient, leading to inadequate management of national maritime affairs, including the oversight of ROs situated overseas. The presumption is that the circumstances necessitating the safeguarding of the subject are identical in Panama, Liberia, the Bahamas, and the Marshall Islands.

The legal soundness of the Merchant Shipping Act of the Bahamas, a jurisdiction known for its flag of convenience, was affirmed in a landmark ruling by the U.S. Federal Court of Appeals at Sundance. The legitimacy is substantiated by the explicit safeguard provided to government-affiliated or government-acting ship surveyors in Article 11, Paragraph 5 of Part 1 of the Canada Shipping Act. The implications arising from this provision carry considerable weight.

The legal judgment made by the U.S. Federal Appeals Court, which exempts the ship inspection agency from civil liability, is based on the Bahamian Merchant Marine Act. This decision affirms the ship owner’s non-delegable duty for ship safety management. Therefore, there is no distinction between the liability law that is predicated on the shipowner’s occupation and proximity in relation to conventional seaworthiness and ship safety. This case has generated concerns among numerous foreign shipowners who have registered their vessels under flags of convenience in various states.

The provision regarding immunity from legal actions, as outlined in the Bahamas Merchant Shipping Act, stipulates that ship owners or shipping lines utilizing flags of convenience are exempt from holding the Bahamian government, public officials, or government agency inspection agencies liable for any maritime accidents. This clause is based on the recognition of the international nature of maritime law and the shipping industry. This provision is deemed essential in order to address the intricacies of the industry and guarantee equitable allocation of liability. Another aspect of the open registry-based incentive policy should be considered. The inclusion of provisions regarding immunity from legal actions, as outlined in the Bahamian Merchant Shipping Act and Canadian law, is anticipated to yield favorable outcomes in terms of safeguarding and enhancing the training of government ship surveyors or specialists in government ship inspection.

Summary

Article 275 of the Bahamas Merchant Shipping Act and Article 11, Paragraph 5 of the Canada Shipping Act provide exemptions from civil and criminal liability in the event of an inspection conducted in good faith. This provision is deemed unfavorable from the shipping company’s perspective as it restricts their ability to initiate legal proceedings against the ship inspection agency. The law regarding whether a shipping company or an insurance company can hold a ship inspection agency or surveyor liable for civil liability was extensively discussed in the Sundancer case.

After consulting with experts in the Canadian maritime sector, it has been noted that Canadian professional surveyors demonstrate superior skills and efficiency in conducting safety inspections compared to foreign shipping or inspection agencies. This is particularly evident when inspecting ships operating in extreme cold weather conditions of −30 degrees Celsius.

In contrast to countries like the UK and the US, which are considered advanced in terms of shipping, there are no specific lawsuit immunity provisions in place. However, there have been instances where immunity has been granted to inspection groups and surveyors. In Korea, however, there is a lack of accumulated precedents and insufficient development in the ship safety industry, which has resulted in a lack of discussion on social norms. However, it can be said that there is room for normative discussions in the future to consider reducing criminal punishment or introducing provisions for lawsuit immunity based on the legal principle of good faith.

After analyzing punishment cases for ship inspections in Japan, China, and common law states, no instances of punishment were found. In other words, it is concluded that there are no instances of criminal punishment, except for bribing ship surveyors or conducting inspections through corrupt means. As a result, Article 83(13–2) of Korea’s Ship Safety Act seems to be lacking in rationality or validity.

Despite instances where ship inspection activities have been perceived as hindering business operations, it is not valid to assume that the incorporation of Article 83(13–2) would lead to the widespread imposition of criminal penalties via the enforcement of administrative criminal law within the administrative law framework.

provides a concise overview of the aforementioned provisions related to punishment.

Table 4. Comparison of punishment provisions for inspection action by ship surveyors in major shipping countries.

It is quite natural, and we agree that each country has different laws based on its unique history and culture. However, it is important to remember that Korea has ratified the SOLAS and should comply with the RO Code and III Code, regardless of the differences in national laws from country to country. A ship survey is essentially a domestic survey, but it is important to consider that the RO Code, which is part of an international agreement, provides the qualifications necessary to conduct the survey. The decision to only punish ship surveyors in Korea, while they are not penalized in many other countries, was evidently influenced by public opinion following the Sewol Ferry disaster. This legal analysis raises questions about the possibility of excessive punishment.

Issues in the theory of law with Article 83(13–2) of the Ship Safety Act of Korea

After the tragic incident of the Sewol Ferry accident, the Republic of Korea implemented legislation aimed at holding accountable ship surveyors who are private individuals from non-governmental organizations, in contrast to foreign states. Although there have been previous instances, the application of the crime of obstruction of business to individuals is established under the Criminal Act (Supreme Court of Korea, Citation2018). The act established an unfavorable precedent in terms of penalizing ship surveyors using administrative criminal law.

Following the tragic incident of the Sewol Ferry accident, a new provision, namely Article 83(13–2), was incorporated into the Ship Safety Act in 2015. This provision explicitly prohibits ship surveyors from engaging in fraudulent activities or any other improper means during the course of their inspections conducted on behalf of the government. Administrative punishment was implemented to facilitate the efficient execution of disciplinary measures in a singular occurrence.

It is imperative to establish penalties as a means of guaranteeing compliance with and consistency of the law. Amendments have been implemented to enhance the stringency of penalties linked to illicit activities carried out during ship inspections.

Following the tragic incident of the Sewol Ferry disaster, there has been a significant increase in the level of responsibility assigned to ship surveyors, as the scope of penalties has been expanded to encompass fraudulent activities or any other forms of misconduct. It is evident that subsequent to that, the conduct of the surveyors has become excessively formalized and subordinate to a framework in which actions are excessively reliant on the specifics of the technical standard (S. L. Lee et al., Citation2023).

The task of ship surveyors, however, still requires them to meticulously interpret and occasionally modify standards and technologies in a comprehensive manner.

Constitutional principle of proportionality

According to the provisions outlined in the Ship Safety Act, the responsibility for conducting ship inspections lies with the government’s designated inspection agency, as mandated by the Act. Additionally, in accordance with administrative law, the government bears responsibility. The focus of this discussion pertains to the legal implications of job-related actions carried out by an surveyor employed by a government’s delegated inspection agency, who, despite their professional role, is essentially an ordinary citizen. The objective of this study is to assess the suitability of the punishment provisions for ship surveyors employed by the government’s delegated inspection agency, in light of the principle of proportionality as outlined in the Constitution.

Given that ship inspection, as mandated by the Ship Safety Act, is a compulsory examination overseen by the government, it is reasonable to infer that it is conducted by government officials. According to the provisions outlined in the Ship Safety Act, ship inspections are carried out by private individuals who serve as surveyors and are affiliated with private organizations. The occurrence of separating administrative liability, liability for state compensation, and criminal liability is evident. The aforementioned statement implies that the person entrusted with the enforcement of criminal law or administrative penalties is the surveyor appointed by the government’s designated inspection agency.

Article 83 of the Ship Safety Act stipulates that surveyors from government-delegated inspection agencies, who are civilians, may be subject to administrative punishment if issues arise in relation to the performance of their duties as prosecutors.

Inspections are conducted by interpreting technical content that consists of technical notices under laws such as the Ship Safety Act or classification rules, which are private standards. Nevertheless, if these principles are misapplied to the field, even in a singular instance, there exists a substantial potential for establishing the constituent elements of a criminal offense. The reason behind this is that the range of penalties for such instances is encompassed within the broadly defined classification of “inspection conducted by fraud or other improper means.”

Under the provisions of the Ship Safety Act, the government bears explicit responsibility for conducting ship inspections, which pertain to ensuring the safety of the vessel. On the contrary, the person responsible for job-related offenses (excluding personal crimes such as bribery) according to criminal law is an surveyor employed by a government’s designated inspection agency, who essentially holds the status of an ordinary citizen. One concern arises from the fact that it is leading to an inequitable implementation of the law. Furthermore, there exists significant uncertainty regarding the alignment of the provisions outlined in the Ship Safety Act, which mandate rigorous ship inspections, with the constitutional principle of proportionality in relation to the gravity of penalties imposed on surveyors from government-authorized inspection agencies who engage in criminal activities.

In essence, the evaluation of the ship surveyor’s actions in relation to societal norms is contingent upon several factors, including the public interest of the act, the absence of dominance and substitutability, and the degree of causal remoteness. If the severity of the punishment is substantially decreased due to the provisions outlined in the Criminal Act or the Ship Safety Act, one can argue that even if it is determined that the implementation of the punishment provisions is unlawful, the degree of accountability is also diminished, thereby reducing the probability of establishing a criminal offense. In this regard, it could be advisable to adopt a conservative stance towards criminal liability pertaining to the inspection activities carried out by ship surveyors.

Concerns about the broad interpretation and legalistic approach to crime

Since the ship surveyor punishment provisions of Article 83(13–1) of the Ship Safety Act are penalty provisions stipulated in administrative regulations, they can be considered a form of administrative criminal punishment. Criminal punishment aligns with the constitutional principle of the legality of crime, which is a fundamental tenet of criminal law. It must not be violated.

The latter part of Article 12, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution states, “No person shall be arrested, detained, searched, seized, or interrogated except as provided by law.” “No person shall be punished, placed under a preventive order, or subjected to involuntary labor except as provided by law and through lawful procedures.” The first part of Article 13, Paragraph 1 stipulates the legal principle of criminal punishment by stating, “No citizen shall be prosecuted for an act that does not constitute a crime under the Act in force at the time it was committed” (Kwon, Citation2010).

The principle is that the acts that constitute crimes, as well as the type and scope of punishment imposed on those crimes, must be stipulated in written law in advance before the act. It is up to the public to determine what constitutes a crime and what is punishable. This is the fundamental principle of national criminal law within a system governed by the rule of law. Its purpose is to safeguard the legal stability of individuals by establishing clear and predictable norms, and to protect individual freedom and rights from the arbitrary exercise of the state’s punitive authority. This is achieved through the establishment of a comprehensive written system of penal laws (Constitutional Court, Citation1991).

The principles derived from criminal legalism include statutory legalism, the principle of non-retroactivity, the principle of clarity, the principle of prohibiting analogical application, the principle of adequacy, etc. Among these, the problematic aspects concerning Article 83, Paragraph 13–2 of the Ship Safety Act are the lack of clarity and the lack of appropriateness. Therefore, it is necessary to review whether there is a violation of the principle of criminal punishment under Article 83(13–2) of the Ship Safety Act, with a focus on the principles of clarity and proportionality.

Principle of clarity

The principle of clarity refers to defining crimes and punishments as clearly as possible in the law. This allows the general public to predict which acts are prohibited under the criminal law and what punishments will be imposed for those acts. It also helps prevent the arbitrary application of the law by judges. In other words, the determination of whether clarity is achieved should be based on assessing whether the information is presented in a manner that can be understood by individuals with reasonable common sense and basic legal knowledge (Supreme Court of Korea Supreme Court of Korea, Citation2008). This includes understanding the protected legal interests outlined in the relevant laws regarding punishment, as well as comprehending the different types of prohibited acts and their corresponding levels of punishment through ordinary interpretation methods.

The structural requirements of Article 83(13–2) of the Ship Safety Act are comprised of objective structural requirements and words regarding “fraud or other improper means.” Among these, the fraudulent part appears to be certain and clear to some extent. However, if the definition of fraud is applied too broadly to include inspection preparation, procedures, report writing, joint inspection, and trust in the inspection process, the scope of elements and punishment becomes excessively wide. There is a risk of expansion, and there are sections that are unclear. It is argued that defining improper means in terms of the text and common sense is challenging, as it can be overly broad and contradict the principle of clarity in the principle of legality of criminal punishment.

There is a high possibility that the scope of application of Article 83, Paragraph 13–2 of the Ship Safety Act will be interpreted and applied too broadly. Therefore, a reasonable interpretation of the law should be based on the principle of clarity in criminal legal principles. In cases where the law requires revision or deletion, alternative legislation or other existing remedies, such as measures for redress, should be considered. Additionally, punishment for obstructing business should also be taken into account (I. H. Kim et al., Citation2020)

Principle of adequacy

The principle of adequacy, one of the principles of criminal legalism, states that laws governing crimes and punishments should be appropriate to safeguard fundamental human rights. The principle of adequacy is based on the principles of proportionality and the prohibition of excess, as stated in Article 37, Paragraph 2 of the Constitution. It is argued that criminal laws and punishments can violate fundamental human rights. Since it is a serious measure, it should be used as a last resort whenever possible. This principle is commonly known as the complementarity of criminal law and punishment (I. H. Kim et al., Citation2020).

The complementary nature of criminal law implies that it should be utilized as a final option, employed only when it is not feasible to safeguard legal interests through alternative methods. Rather than being the primary means of social control, criminal law can only be considered justified when it serves as a supplementary tool to social control through other norms or methods.

Article 83 of the Ship Safety Act stipulates that the inspection of ships and the removal of substandard ships can be addressed through administrative regulations for maritime safety. However, it is highly probable that it may be considered inconsistent with the principle of adequacy, as it introduces an additional administrative penalty.

Although there are many other administrative, civil, and disciplinary measures to ensure the appropriateness of ship inspections, hastily introducing administrative penalties without considering or evaluating other supplementary measures disrupts the balance and contradicts the complementary nature of criminal law.

Moreover, it is worth noting that the classification surveyor who inspected the Sewol ferry was punished by the Supreme Court’s ruling in 2015 (Do12094). Although the surveyor was ultimately found guilty of obstructing business through fraudulent means, as stated in Article 83 of the Ship Safety Act under the Criminal Act, the introduction of a duplicate punishment provision, known as provision 13–2, is considered excessive. This provision is seen as a double punishment clause that violates the principle of complementarity.

Of course, ship inspections are conducted by following appropriate procedures, and the legislative purpose of maintaining the safety of ships through this process can be considered justified. Additionally, the need to protect legal interests is recognized. However, additional provisions for punishment should have been enacted after careful consideration and review of whether the methods used to achieve the legislative purpose of protecting legal interests are appropriate, balanced, and consistent with the supplementary nature of criminal law. It should also be determined whether alternative solutions can be found within existing criminal law provisions.

Imbalance with civil liability

Reducing the risk of civil or criminal liability for ship inspections

Ship inspection is a conformity assessment activity. One important aspect of conformity Ship inspection is a conformity assessment activity. One important aspect of conformity assessment activities, particularly when conducted by third parties such as the government or a RO, is their objectivity and public nature. This means that even if an error occurs during the inspection process, resulting in damage or a violation of the law, the level of responsibility for such actions is essentially reduced.

The reasons for reducing the possibility of criticism of conformity assessment activities are as follows: First, third-party conformity assessment activities have a strong public interest nature as they relate to the safety and environment of the entire society. Second, conformity assessment activities based on legal norms are of particular importance. Third, the common belief is that both civil law and criminal law focus on the theory of illegal conduct rather than the theory of illegality based on the outcome. Fourth, in the case of civil liability, it is difficult to recognize the existence of a duty of care between the assessor and the victim unless there is dominance, substitutability, or proximity in the assessment act, even if there is negligence in the conformity assessment. The influence of third-party conformity assessment agencies on ships undergoing evaluation is significantly weaker compared to that of the shipowner. These agencies do not have the authority to replace the shipowner’s original ship safety management measures. Fifth, the perpetrator faces challenges in recognizing the predictability and avoidability of their actions and the resulting damage, as well as establishing a causal relationship between their negligent act and the damage.

Policy considerations regarding public interest and civil liability in ship inspections

RO’s classification inspection under the Ship Safety Act has significant legal advantages RO’s classification inspection under the Ship Safety Act has significant legal advantages compared to random commercial inspections conducted by general stakeholders, primarily due to its public normative effect. Classification inspection, which is considered a government inspection under Article 73 of the Ship Safety Act, can be viewed as a “public interest inspection.” As long as it is considered a government inspection, it is based on the illegal acts of a third party who has suffered civil damages as a result of a public interest inspection conducted by a government’s delegated inspection agency. Claims for damages against inspection agencies may be limited due to public policy.

Regarding classification inspection, it can be seen that there is room to acknowledge a third party’s right to claim state compensation. Even if the duty of care is recognized, negligence is established, and causality exists, it is not in line with the best interests of society as a whole to burden the subject of a public interest inspection with financial responsibility for public interest acts when determining the amount of compensation. It can also be argued that this approach could lead to a significant reduction in the public interest activities of government’s delegated inspection agencies, based on the theory of limitation of liability grounded in public policy.

Risks permitted under the criminal law in a scientific and technological society

Regarding the risk society mentioned by German sociologist Ulrich Beck in his book “Risikogesellschaft,” it is generally accepted that modern society is a risk society (J. Y. Kim, Citation2005; K. Kim, Citation2010). It is stated that human life and property are constantly exposed to risks as new hazards emerge with the advancement of science and technology (Beck, Citation2006). Risk-based criminal laws are penal provisions created or newly enacted to prepare for or prevent new technological risks in modern society.

Article 83(13–2) of the Ship Safety Act serves the purpose of conducting comprehensive inspections on ships to mitigate the risk of accidents caused by the increasing size and complexity of ships resulting from advancements in science and technology. Acts with unclear responsibility can still be punished based on the likelihood that they are dangerous, even if their causal relationship to the infringement is not objectively established. This expands the normative debate on whether to relax or objectively attribute the causal link between the act and the resulting violation. Additionally, it is also undesirable for the country to solely focus on enacting legislation or policies that enhance preventive measures in high-risk areas as a response to future uncertainty.

The criminal law must intervene in a subordinate and supplementary manner to sanctions outside the criminal law, only as a last resort. No matter how much emphasis is placed on precaution in a society filled with risks, and no matter how legal principles are shaken in the name of preventing danger and ensuring safety, it is possible that the rule of law may actually be compromised, leading to damage to legal norms. It may emerge as a source of risk that violates the basic rights of law-abiding good citizens (Cho, Citation2014).

In highly specialized areas such as shipping, it is effective to conduct a normative evaluation of behavior according to an objective attribution theory that takes “risk” as an important element (Yang, Citation2018). For instance, when assigning responsibility for a ship accident to an surveyor, it is crucial to establish whether the surveyor’s actions genuinely contributed to or worsened the risk, considering the broader legal framework in today’s risk society (Renn et al., Citation2011; Ulich, Citation1999; Yun, Citation2019).

If the actions of the surveyor lead to a decrease in overall risk instead of an increase, it is difficult to objectively attribute the outcomes of the legal interest infringement to those actions, even if there is a causal relationship between the infringement of legal interests caused by a shipping accident or business interruption of the company and the surveyor’s inspection actions.

Ship inspection is a highly technical field that requires a certain level of expertise. It is an act that aims to reduce risk rather than create or exacerbate it. As the final step in applying principles such as intent, negligence, illegality, and liability, and civil law violation of duty of care, illegality, negligence, and tort liability, public policy considerations are taken into account to determine the possibility of assigning blame from a broader societal perspective. A thorough examination of ship inspections is important within the context of public policy (UK Supreme Court, Citation2015).

In particular, if the inspection conducted by the surveyor serves a public purpose and has the potential to mitigate the risks associated with the ship, it is highly undesirable to categorize the omission of inspection items as either intentional interference with business or as a false act. Such categorization, which implies the use of illegal methods for inspection, is contrary to the principles of maritime safety policy.

Ship inspection is a field that requires the use of professional expertise and discretion. While some negligence may be acknowledged, it is considered an acceptable level of risk under criminal law due to its significant public interest. The court’s determination of the surveyor’s criminal liability in this matter requires a judicial judgment. However, it is highly likely that this area requires caution.

Equity in the application of the law

Instances in which surveyors affiliated with organizations tasked with conducting inspections of automobiles or airplanes have been subjected to disciplinary measures under the applicable transportation management legislation or for impeding business operations as a result of insufficient inspection protocols are infrequent. In the realm of automotive industry, one could contend that assigning blame to the individual responsible for vehicle inspections in the event of accidents is somewhat unjustifiable. This exemption from criminal liability for most drivers is attributed to Article 4 of the Act On Special Cases Concerning The Settlement Of Traffic Accidents (Seo, Citation2022).

To date, no prior occurrence has been recorded wherein an inspection agency has faced criminal liability in relation to an aviation accident. On the contrary, upon closer examination of the instances of criminal punishment thus far, it becomes apparent that ship surveyors are more susceptible to criminal liability due to insufficient inspections or substandard report writing in comparison to surveyors in other transportation sectors.

Automobiles, airplanes, and ships possess the shared attribute of being modes of transportation that depend on scientific and technological progress. However, it is important to acknowledge that these industries also entail inherent risks. While it is generally anticipated that employees across various industries should uphold a duty of care and be accountable within the confines of the law, a significant issue arises regarding the lack of punitive measures for actions that impede business operations, with the exception of the shipping sector. The singular emphasis on maritime vessels poses a substantial obstacle to the fair dispensation of criminal justice.

Excessive criminalization

Excessive criminalization or excessive punishment refers to the practice in which the state imposes penalties for behavior that could be adequately addressed through alternative forms of sanctions (I. J. Kim, Citation2015). The aforementioned plan, originally designed to target a specific individual, surpasses its initial scope by categorizing all citizens and companies as potential offenders. The suppression of freedom and creativity within the economic realm has the consequence of generating individuals who have previously been incarcerated.

From an economic perspective, the concept of overcriminalization can be defined as the stage at which a society ceases to derive any further social advantage from the implementation of new punishment provisions, or when the additional costs of these provisions outweigh their potential benefits (Larkin, Citation2013). In conclusion, the conceptual framework underlying the phenomenon of excessive criminalization suggests that the most effective deterrent effect can only be achieved when regulated acts are met with corresponding sanctions, such as punishment (Luna, Citation2005). The problem of overcriminalization is rooted in its propensity to distort the direct or indirect outcomes of punishment as the ultimate solution, consequently casting a negative light on the concept of overcriminalization (Ashworth, Citation2008).

Article 83(13–2) of the Ship Safety Act can be utilized as an administrative sanction. Although there have been multiple cases of prosecution or legal action taken against obstruction of business under criminal law, particularly in relation to ship inspections, the introduction of this newly enacted law may be considered as redundant legislation. Despite possessing sufficient deterrent capabilities, the legislation can be characterized as an instance of excessive criminalization.

Results of a questionnaire on the impact of the disciplinary system for ship surveyors

Outline of questionnaire

There has been a significant increase in cases of holding ship inspectors criminally liable for inadequately written ship inspection reports following the Sewol Ferry decision.

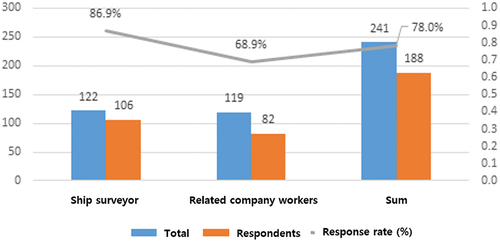

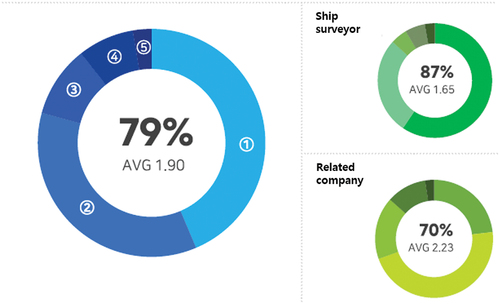

To address this from a practical viewpoint, an online survey was conducted to evaluate the industry’s response to the strict regulations imposed on ship surveyors. The survey was conducted online from 2:00 p.m. on 6 March 2023, to 12:00 a.m. on 27 March 2023. A total of 106 ship surveyors from KR, BV, KOMSA, and 82 workers from related companies, such as shipbuilding or equipment companies, responded. During the survey period, 188 out of 241 people responded, indicating a response rate of 78% as shown .

According to the survey results, the majority of respondents indicated that the increased severity of penalties under the Ship Safety Act has a negative impact on ship surveys and related companies. They agreed to revise the relevant provisions of Article 83.

Specifically, they complained of fatigue as rigorous surveys continued due to the strengthening of penalties under the Ship Safety Act, and they expressed doubts about the efficacy of measures to enhance safety and prevent accidents.

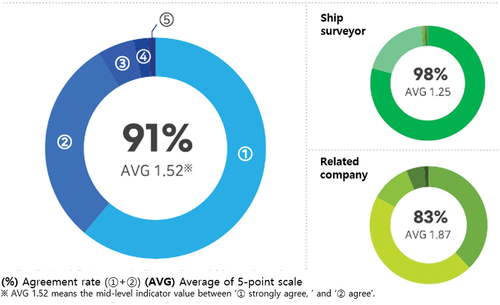

Eight questions were asked. Scores are the weighted average value on a 5-point scale (1 - strongly agree, 2 - agree, 3 - neutral, 4 - disagree, 5 - not at all).

Summary of the survey results are presented in the .

Table 5. Summary of survey results.

Closer examination of some of the survey results

Out of the eight questions, we would like to focus on questions 1, 2, 7, and 8.

Question 1: negative impact by newly adopted punishment regulations

The first question was as follows, and the results are shown in .

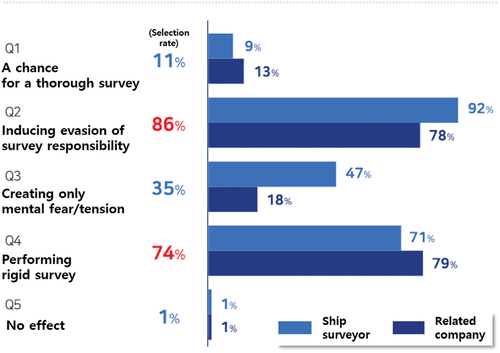

Question 2: impact of strengthened punishment regulations

The second question was as follows, and the results are summarized in .

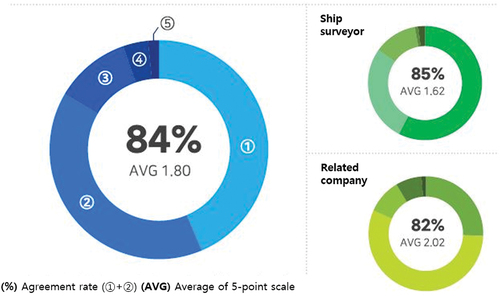

Question 7: reduction of punishment subject to special surveys

The 7th question was as follows, and the results are summarized in .

Question 8: abolition of punishment provisions of the Ship Safety Act

The 8th question was as follows, and the results are summarized in .

Proposal for amendment of Article 83(13–2) of the Ship Safety Act of Korea