Abstract

This article analyses the institutional design variants of local crisis governance responses to the COVID-19 pandemic and their entanglement with other locally impactful crises from a cross-country comparative perspective (France, Germany, Poland, Sweden, and the UK/England). The pandemic offers an excellent empirical lens for scrutinizing the phenomenon of polycrises governance because it occurred while European countries were struggling with the impacts of several prior, ongoing, or newly arrived crises. Our major focus is on institutional design variants of crisis governance (dependent variable) and the influence of different administrative cultures on it (independent variable). Furthermore, we analyze the entanglement and interaction of institutional responses to other (previous or parallel) crises (polycrisis dynamics). Our findings reveal a huge variance of institutional designs, largely evoked by country-specific administrative cultures and profiles. The degree of de-/centralization and the intensity of coordination or decoupling across levels of government differs significantly by country. Simultaneously, all countries were affected by interrelated and entangled crises, resulting in various patterns of polycrisis dynamics. While policy failures and “fatal remedies” from previous crises have partially impaired the resilience and crisis preparedness of local governments, we have also found some learning effects from previous crises.

1. Introduction

Any crises and threats affect local levels more directly and immediately than upper levels of government (OECD Citation2020; Broadhurst and Gray Citation2022). Local governments assume key functions in crisis governance, not only by implementing locally the decisions taken at higher levels of government. In some countries, they also enjoy considerable discretion in crisis-related policymaking and in deciding on mitigation measures (see Bauer, Otto, and Schomaker Citation2022; Kuhlmann et al. Citation2023). The effectiveness of polycrises management is thus crucially dependent on the capacity of the local level to act and solve problems autonomously.

The institutionalization of crisis-related decision-making and implementation represents a key feature of polycrises management. However, the role of local governments in tackling polycrises has remained an understudied field of research, particularly from a cross-country comparative perspective. Thus, the academic discourse on crisis-related policy designs is rather controversial and inconclusive.

Against this background, our article analyses institutional design variants of local crisis governance responding to the pandemic and their entanglement with other locally impactful crisis phenomena from a cross-country comparative perspective (France, Germany, Poland, Sweden, and the UK/England). The pandemic offers an empirical lens for scrutinizing the phenomenon of polycrises governance because it occurred while European countries were struggling with the impacts and mitigation measures of previous, ongoing, or newly arriving crises (see below). Our major focus is on institutional design variants of crisis governance (dependent variable) and how these are influenced by different administrative cultures (independent variable). Our ambition is not to show how administrative cultures determine current structures, but rather to identify possible causal patterns and formulate potential explanations to be further examined comparatively. Furthermore, we analyze the entanglement and interaction of institutional responses to other (previous or parallel) crises (polycrisis dynamics). Our contribution revolves around the following research questions:

Which institutional design variants of local pandemic governance can be identified in different countries? What is the role of local governments and intergovernmental coordination in managing the crisis?

How have institutional path-dependencies, originating in historically ingrained administrative traditions and cultures, influenced the country’s institutional responses to the pandemic?

In the following, we will proceed as follows: After presenting our conceptual framework (Section 2) we will outline our methodological approach (Section 3), followed by an analysis of local institutional design variants (Section 4) and the polycrises dynamics from a county-by-country perspective (Section 5). Finally, we will discuss our findings from a cross-country comparative perspective (Section 6) and draw some conclusions (Section 7).

2. Conceptual frame: institutional designs of local crises governance

Dealing with various kinds of big or small emergencies, disasters or crises traditionally belongs to the day-to-day business of public institutions. Turbulence − as Ansell, Sørensen, and Torfing described it − “has become a chronic and endemic condition for modern governance” (2022: 3). However, the crisis landscape since the beginning of the 2020s has changed significantly. It is characterized by the simultaneous occurrence and the increasing interactions of later mentioned various (acute and long-term) crises labeled as “polycrises” (see Henig and Knight Citation2023).

Drawing on these debates, our contribution takes a specific public administration perspective, conceiving crises as eruptive and/or creeping events and dynamic developments that challenge established organizational routines and require institutional responses. They can be seen as “game-changers in our thinking about public administration and leadership” (Ansell, Sørensen, and Torfing Citation2021: 953). We apply the term polycrises to situations of multiple successive or simultaneously interconnected crises, including (un-intended and potentially long-term) crisis mitigation impacts from previous crisis “solutions” (see ‘t Hart and Boin Citation2001).

Our analysis is concentrated on a particular component of policy design, namely the institutional design of polycrises governance, especially the crisis-related changes in institutions, organizational settings, and coordination mechanisms. This can be referred to as “institutional policy” or “polity-policy,” (see Kuhlmann and Wollmann Citation2019; Wollmann, Citation2003: 4) as it is directed at changing the institutional and procedural characteristics of policymaking. Polity-policies on crisis governance thus are materialized in institutional design variants directed at managing crises and polycrises, respectively.

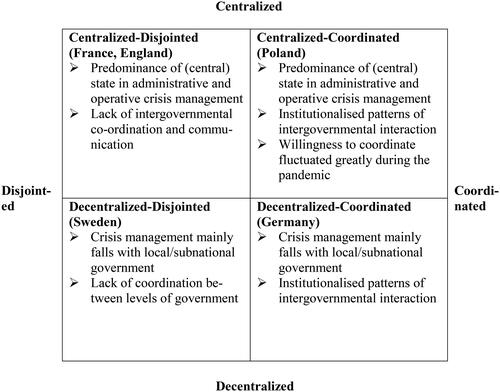

Drawing on pertinent research, we conceptualize our dependent variable based on two key dimensions (see Oehlert and Kuhlmann Citation2024; Hegele and Schnabel Citation2021): (1) the allocation of tasks in the multi-level system and (2) the degree of intergovernmental coordination or decoupling. The first dimension refers to the predominant level of functional responsibilities formally assigned to a particular unit of administration in the field of pandemic management/containment (state/central government vs. local government). The second dimension addresses the separation or coupling of levels of crisis management, thus relating to coordination in the intergovernmental setting.

Regarding our independent variable, we draw on pertinent typologies used in comparative public administration (see Kuhlmann and Wollmann Citation2019) and make a distinction between five clusters of administrative cultures in Europe (see below). Drawing on historical institutionalism (see Steinmo, Thelen, and Longstreth Citation1992; Peters Citation2011), our theoretical assumption is that the institutional designs of crisis governance are largely influenced by a country’s historically ingrained administrative culture, in particular its intergovernmental and local government traditions. These constitute path dependencies that predetermine future institutional choices on crisis governance and shape institutional corridors for responses to crises and new policy challenges. More specifically, we assume that countries with historically well-established, functionally strong and viable local governments will tend to allocate key functions of crisis management to their local levels, while countries with more centralist administrative traditions and weaker local governments tend to ignore the local actors in crisis management and instead largely rely on the central government’s interventions (see Christensen et al. Citation2016; Graf, Lenz, and Eckhard Citation2023; Boin et al. Citation2016: 51). Furthermore, where a country can draw on a collaborative culture in the relationship between the central and the subnational levels, we expect the institutional design of crisis governance to be fairly coordinated and interlinked, while in country contexts with more conflictive intergovernmental cultures, crisis management will be rather disjointed and disconnected from a multi-level perspective. In our empirical analysis, we will address these theoretical assumptions by considering five representative cases of European administrative cultures and examining their influence on institutional designs of crisis governance. There are undoubtedly several other factors that could influence and shape the institutional design of crisis governance. This applies, for example, to regional actor constellations and political preferences, resources, capacities and expertise, as well as possible external variables (such as size, population, and geographical location). However, in this article we focus on the role of administrative cultures and historical path dependencies, while the impact of other potentially explanatory factors could be left to future studies to explore. We do not assume an entirely deterministic relationship between administrative cultures and crisis governance. Rather, we attempt to identify potential causal relationships in an exploratory manner.

3. Methods, data, case selection

Our analysis (period of investigation between 2020 and 2022) is based on two main methodological steps. In the first step, we analyzed around 350 documents on crisis governance in the five countries of our sample, including academic publications, official documents, reports, evaluations, legal texts, and media reports. Furthermore, we referred to theoretical contributions on governance and pandemic management. In the second step, we conducted 14 semi-structured interviews to complement desk research with insights from academics and practitioners (see Table S1, Annex), using a deductive approach for our coding scheme, based on the existing theoretical framework and our previous research in this domain. Drawing upon the methodological foundations laid out by Mayring (Mayring Citation2015), we structured our analysis around predetermined categories such as legal frameworks, governance dynamics, and intergovernmental coordination (see Table S2, Annex). Each of these categories was further broken down by specific indicators – such as the legal emergency structures in place, how crisis management responsibilities across government levels are distributed, and the interaction between various government bodies – enabling a detailed examination of how the pandemic was managed and its broader effects on governance practices. This method allowed us to systematically evaluate the impact of the pandemic, while also integrating findings from our past research on similar topics.

Based on our theoretical expectations (see above), we selected five countries (France, Germany, Poland, Sweden, and the UKFootnote1) which represent typical administrative traditions and cultures in Europe (see Kuhlmann and Wollmann Citation2019), guided by a most-different-cases design for varied insights into crisis governance. Our study is guided by a most-different-cases design, according to which a high degree of variation in administrative cultures promises insights into the impact on institutional designs of crisis governance (see Table S3, Annex).

4. Institutional designs compared: legal regimes, task allocation, and intergovernmental coordination

Proceeding from the assumption that administrative cultures – as our independent variable – largely shape countries’ responses to crisis challenges, we aim to analyze the institutional design variants of local pandemic governance – as our dependent variable – in the five different administrative contexts. We systematize our findings along the following analytical categories: legal framework of the pandemic regime, centralization/decentralization, intergovernmental coordination, local activities, and impact of administrative cultures on crisis governance. Finally, we draw on our theoretical framework, inspired by historical institutionalism (see above), to reveal the influence of historically shaped institutional corridors on actors’ institutional design choices in response to the crisis challenges.

4.1. Germany: decentralized-coordinated crisis governance

4.1.1. Legal framework of the pandemic regime

Regarding the legal basis of pandemic governance, a key characteristic of the German approach was the federal government’s decision not to make use of emergency regulations provided by the constitution (e.g. for natural disasters or accidents affecting several German Länder, Article 35 Basic law). Germany’s pandemic strategy utilized the federal Infection Protection Act (IfSG), emphasizing decentralized crisis management to maintain the federal balance. In particular, article 28 of the IfSG was used as a “by no means clearly worded general clause” (cf. Kersten and Rixen Citation2020: 36) to legally back most of the measures intended to fight the pandemic. Based on this law, the new legal construct of an “epidemic emergency of national concern” was introduced on March 25 2020 and was in force until November 25 2021.

4.1.2. (De-)centralization, intergovernmental coordination, and local activities in crisis governance

The German case is marked by a continuously decentralized institutional design within which the Länder and local governments are the main actors in implementing the pandemic measures. Nevertheless, aspects of limited centralization were observed during the pandemic. Concerning the allocation of competencies in pandemic management (see Weinheimer Citation2022), the 16 Länder are responsible for the implementation of the IfSG while the federal government cannot impose any measures on them. All containment measures were thus based on decisions taken by the Länder and local governments executing the IfSG. In particular, the 400 local health departments took over a bulk of competencies not only in issuing containment measures, but also in monitoring, reporting, tracing, and tracking infection cases, supervising quarantine obligations, and punishing the violation of containment regulations.

Nevertheless, the pandemic led to a temporal centralization of the German political-administrative system (see Vampa Citation2021: 613; Waldhoff Citation2021: 2775). Hence, the Federal Ministry of Health received additional competencies to be able to quickly react without the consent of the Länder and the Bundesrat. Furthermore, between April and June 2021, pandemic measures were standardized nationwide for the first time by the so-called “Federal Emergency Brake.”

Coordination during the pandemic was largely managed through the “Conference of the Federal Chancellor with the Heads of Governments of the Länder” (Federal-state conferences), despite challenges in developing a uniform national strategy (see Kuhlmann and Franzke Citation2022). In those circumstances, the conference’s output was limited to political “declarations of intent,” which thus needed corresponding ordinances from all involved parties to become legally binding. Therefore, the pandemic confirmed the central role of German subnational authorities in crisis management, which had to implement an “unprecedented flood of laws and regulations” (Interview 14) directly through municipal containment ordinances under time pressure and had to inform their citizens of these new regulations.

4.1.3. Impact of the administrative culture on crisis governance

The German administrative system is well-known for its highly decentralized character with the Länder and local governments as key actors of law enforcement, public service delivery, and task fulfillment. This historically ingrained institutional legacy has impacted governance strategies during the pandemic, as crisis responses have been revealed as being highly decentralized and institutionally fragmented. Local governments used their functional strength and strong legal position within the intergovernmental system to quickly react to the pandemic challenges in a targeted manner. In particular, the municipal “speedboats” (with 50,000–70,000 inhabitants) worked best during the pandemic because they combined sufficient administrative power with flexible local bureaucracies. In the large cities, by contrast, it was “incredibly difficult to make decisions quickly” (Interview 12). Some temporal centralizing tendencies during the crisis notwithstanding, Germany’s institutional design of crisis governance largely followed the established historical path of decentralized task allocation, local discretion, and administrative federalism/localism. Furthermore, drawing on the tradition of cooperative federalism and highly entangled inter-administrative relations, crisis governance was marked by intense collaboration across levels of government contributing to mitigating conflicts and tensions.

4.2. France: centralized-disjointed crisis governance

4.2.1. Legal framework of the pandemic regime

France’s centralized pandemic governance was enacted through a ‘public health emergency’, introduced on 23 March 2020, allowing for decrees without parliamentary approval (Kuhlmann et al. Citation2021: 564). The relevant decisions on measures implemented within this framework were taken in the “Health Protection Council,” which was chaired by President Macron, and included the Prime Minister and individual ministers appointed by the president (Hassenteufel Citation2020: 174).

4.2.2. (De-)centralization, intergovernmental coordination, and local activities in crisis governance

The French case is marked by a continuously centralized institutional design with a marginal role of local governments. Compared to other countries, the degree of informal decentralization in France, with increasingly active territorial governments (despite lacking formal responsibilities) has remained extremely limited in an international comparison. As is typical for centralized systems, the French crisis pandemic management regime was characterized by the possibility of direct intervention and control (Kuhlmann et al. Citation2021: 564; Vampa Citation2021: 7f.). This is also reflected in the composition of the key actors in the crisis management regime: “the centralized organization of French political institutions has therefore been accentuated, sometimes to the point of taking on personalized forms, around the person of President Macron himself” (Benamouzig Citation2023: 359). In addition, the minister of health could directly intervene through deconcentrated state authorities (especially the prefects). These deconcentrated state actors, rather than local governments themselves, were crucial in the pandemic management (Kuhlmann et al. Citation2021: 566). The regional health authorities have played an important role in implementing and managing the pandemic response in France. Although they were intended to act as crisis coordinating institutions, they were insufficiently prepared to take on such a central role (Du Boys, Bertolucci, and Fouchet Citation2022: 262): “The first task was to mobilize the staff and get them to do everything – except what they were used to doing” (Interview 8). Although local governments tried to implement their pandemic initiatives, the distribution of competencies between central and sub-national actors remained unchanged: “the central state took care of the management of the crisis, while the local mandate holders played a bit in their sandbox” (Interview 6). Against this background, it is not surprising that all relevant decisions were ultimately taken by the central government, especially in phases with high infection dynamics. Their implementation at the local level was characterized by strict guidelines and supervision (Du Boys, Bertolucci, and Fouchet Citation2022: 259).

4.2.3. Impact of the administrative culture on crisis governance

Traditionally, France’s political and administrative system is characterized by a dominant central state and functionally weak local governments. Despite recent decentralization efforts, France’s centralized, top-down control, a legacy of its Napoleonic path dependency, was pronounced during the pandemic. This powerful historic legacy has influenced and determined crisis governance significantly. However, against the backdrop of previous decentralization steps and increased territorial powers, local governments complained about a lack of involvement and insufficiently differentiated measures on the part of the central state (Interviews 6, 11). Thus, in France we could observe a clash between historic path-dependencies of the Napoleonic state and an evolving localism that seeks to assert itself more and more. At the same time, intergovernmental relations developed in a disjointed and sometimes even conflictive setting during the pandemic. This decoupling between the state and local level is also a classic feature of French administration, which was only gradually softened in the course of decentralization and the newly created instruments of concentration, partnership, and contract policy. Overall, it can be seen that it was precisely in the face of the crisis that the institutional path-dependencies and historically ingrained features of public administration – some of which were thought to have been overcome – clearly came to the fore again and were effective.

4.3. Poland: centralized-coordinated crisis governance

4.3.1. Legal framework of the pandemic regime

The Polish central government did not use available constitutional possibilities to declare a state of emergency, and instead chose secondary legislation instead. Initially, the Polish COVID-19 policy was mainly based on the Law on the Prevention and Control of Human Infections and Infectious Diseases of 2008. Additionally, the Law on Crisis Management of 2007 and some specific regulations were applied. Through these laws and regulations, the executive temporarily gained additional competencies which were unprecedented in post-communist Poland (cf. Lipiński Citation2021; Jaraczewski Citation2021). Consequently, lockdowns (as implemented in 2020 and 2021) and other containment measures were issued by immediately enforceable central government orders subordinating state units, territorial self-governments, and even private entrepreneurs. Additionally, the Voivode, as regional representative of the central government, could announce and revoke by decree the “state of epidemic threat” or “state of epidemic” for the entire territory of a voivodeship or parts thereof. If these conditions occurred in more than one voivodeship, the Minister of Health could announce and repeal one of the two states of emergency for the entire country using a decree. Since there was no legal way to take legal action against these decrees, self-administration authorities had to follow them (see Sienkiewicz and Kuć-Czajkowska Citation2022: 437).

4.3.2. (De-)centralization, intergovernmental coordination, and local activities in crisis governance

Initially highly centralized, Poland’s pandemic governance later necessitated increased coordination with local authorities. Additionally, Polish territorial self-governments organized specific aid for the most vulnerable groups of inhabitants and supported the local economy during the crisis. By doing so, it gained much public recognition and emerged with stronger public trust from the crisis. Especially regional and county-level authorities were perceived as those public institutions “that coped best with the crisis” (Makowski Citation2023: 3).

In the first phase of the pandemic between March and May 2020, sometimes called the phase of “drastic” corona centralism (see Gawłowski Citation2022), the vertical coordination between the national government and territorial self-government was overshadowed by the centralist (top-down) approach, which corresponds to the government’s authoritarian understanding of the state (Interview 3). Later, it began to increasingly cooperate with other actors, including the territorial self-governments. The consulting process in the “Joint Commission of the Government and Territorial Self-Governments” played an important role in coordinating legislative proposals concerning the competencies of territorial self-governments (Gawłowski Citation2022). It turned out to be a key institution in pandemic crisis governance (Interview 1), ensuring that the territorial perspective was considered by national regulators, and enabling cities and counties to coordinate their measures more effectively. Yet, the relationship with the national government remained difficult and conflict driven.

4.3.3. Impact of the administrative culture on crisis governance

The centralized intervention of the Polish government at the onset of the pandemic, in which it disregarded municipalities, can be seen as a clear expression of a historical legacy. The deeply ingrained centralist understanding of the state, which characterized Polish administration both before the system change and during the recent authoritarian turn, has become evident. However, it proved rapidly to be ineffective and was met with widespread resistance from territorial self-governments and society. As a result, the government was forced to switch to a more coordinated governance mode, involving territorial authorities more closely in national crisis management. The fact that the historically rooted centralism was linked to increased consultation and coordination with local governments during the pandemic’s later stages can be interpreted as a certain departure from the Polish administrative heritage as concerting with territorial authorities is an outcome of a new institutional path following the system change and administrative decentralization. The pandemic showed the strengths of the decentralized unitarian state.

4.4. Sweden: decentralized-disjointed crisis governance

4.4.1. Legal framework of the pandemic regime

Sweden is well-known for being a “deviant case” of pandemic management. Instead of imposing comprehensive containment measures and restrictions, crisis management was organized in favor of a more permissive approach based on recommendations, voluntary guidelines, and minimal restrictive measures (Winblad, Swenning, and Spangler Citation2021: 57), while keeping the society open (Kuhlmann et al. Citation2021).

The legal basis for the mild measures was provided by the Communicable Diseases Act 2004 and the Law on Infectious Diseases 2004. Noteworthy facets of the Swedish strategy encompass the nation’s emphasis on citizens’ responsibilities in protecting the community, the elevated trust in governmental bodies, and the central role of the coordinating Public Health Agency, a largely autonomous governmental body whose expert opinions were the major source of government’s pandemic strategy (see Petridou Citation2020: 153; Bengtsson and Brommesson Citation2022; Olofsson et al. Citation2022). The fact, that the Swedish constitution did not provide a basis on which a state of emergency could have been declared, is one explanation for the “Swedish exceptionalism” (Andersson and Aylott Citation2023). However, with the political and societal pressures increasing (not least stemming from European-wide narratives), the Swedish government enacted the COVID-19 Act in January 2021 based on which broader restrictions became feasible (see Mattsson, Nordberg, and Axmin Citation2021: 63).

4.4.2. (De-)centralization, intergovernmental coordination, and local activities in crisis governance

The choice of this specifically “Swedish approach” had clear impacts on the institutional choices taken for pandemic management. Pandemic containment hardly took place, thus, the role of public administrations as crisis managers was more limited than in countries with severe containment strategies. While the central government (especially the Public Health Agency) was limited to communicating recommendations and guidelines, the regions and local governments were responsible for the provision of healthcare services (regions), elderly care, school supervision, and social services (see Mattsson, Nordberg, and Axmin Citation2021: 6), leading to some coordination dysfunctionalities (“one of the complicated things was actually figuring out who should do what”, Interview 4).

However, municipalities were initially not allowed to autonomously close down public facilities, such as homes for the elderly, which limited their autonomy in deciding about containment measures. After some of them overstepped their legal competencies and autonomously introduced more restrictive measures, contrary to the regulatory framework (Askim and Bergström Citation2022), the central government found itself compelled to change the legal basis through the temporary COVID-19 Act 2021 (Olofsson et al. Citation2022) and to include additional local competencies in the field of pandemic containment (see Askim and Bergström Citation2022: 303). This governance approach also witnessed the inception of the Swedish Local Government Association, SALAR, as the coordinating entity for intergovernmental collaboration (Interview 4).

4.4.3. Impact of the administrative culture on crisis governance

Sweden’s pandemic governance reflects its administrative culture, prioritizing local autonomy and consensus. These characteristic elements of the Nordic model of administrative culture have significantly shaped the country’s pandemic governance. Sweden adopted a strategy that heavily relied on trust in the decision-making capabilities of local actors, but also in the professional expertise of state agencies. This reflects the venerable Swedish agency model, which has existed long before the New Public Management movement and has been characterized by extensive autonomy of state agencies, coupled with extremely limited influence of executive politics on the agencies’ operational activities. This historically rooted model, which is also distinguished by longstanding institutional trust of the population in the recommendations of professional administrative apparatus and a high willingness of citizens to follow them, remained pivotal throughout the duration of the pandemic, embodied in the form of the national health authority. At the same time, the decentralized structure of Swedish administration allowed local authorities to address the specific needs of their communities while adhering to nationwide guidelines as a framework (Interview 10). While pandemic-related behavioral recommendations were centrally formulated and communicated, the traditionally highly decentralized system - with local governments as key actors in crisis management - remained determinative throughout. There can be no doubt that the historically rooted Swedish administrative culture was evident in pandemic governance, with no institutional ruptures recorded.

4.5. England: centralist-disjointed crisis governance

4.5.1. Legal framework of the pandemic regime

The legal basis for declaring a state of emergency in England is provided by the Civil Contingencies Act 2004, which is also the foundational legal framework of British emergency and crisis laws (King and Byrom Citation2021: 11/12). Nevertheless, the British government did not use these emergency regulations when responding to the pandemic crisis. Instead, pandemic regulations were based on ordinary legislative acts, particularly the UK Coronavirus Act in March 2020, even if the legal framework recognized local governments as primary responders to the majority of emergencies and crises (Martin, Kan, and Fink Citation2023: 91). Additionally, the Public Health (Control of Diseases) Act 1984 grants local authorities’ certain health protection competencies and functions (King and Byrom Citation2021: 6).

4.5.2. (De-)centralization, intergovernmental coordination, and local activities in crisis governance

England shows peculiar commonalities with France in pursuing a centralistic approach to pandemic governance, with limited coordination across government levels. Despite relevant pre-pandemic local structures and institutions, England’s pandemic management since March 2020 largely overlooked the local level (Thomas and Clyne Citation2021: 10). The central government rarely utilized the knowledge and experience local governments accumulated from managing previous crises, like extreme weather events and terrorist attacks. Instead, a centralized, top-down strategy was launched by the then Prime Minister Boris Johnson with the enactment of the Coronavirus Act 2020 and the initiation of a nationwide lockdown in late March 2020. The UK government’s pandemic response in the spring of 2020 is often described as “muddling through,” mainly alluding to its crisis communication and disjointed governance in the intergovernmental setting (Joyce Citation2020: 12). The vertical coordination between the national and local levels in England remained poor, as the central government showed reluctance to cooperate and coordinate with local partners (Interview 2). This partly stemmed from a lack of understanding of local crisis management structures and processes among top government officials (cf. Diamond and Laffin Citation2022). Moreover, a “patronizing view of local government” has taken root within London’s ministries and agencies over recent years (Interview 9). This perspective provides little space for effective collaboration between the two governance levels. Local authorities are seen as “less capable, less experienced, more incompetent, and more chaotic than those in the central government. They are below the salt” (Thomas and Clyne Citation2021: 11).

4.5.3. Impact of the administrative culture on crisis governance

England’s pandemic response marked a continuation of its trend toward centralized governance, deviating from its historically more decentralized approach. Thus, it can be said that there is a break with the previous path-dependence in England, using the traditional (pre-Thatcher) administrative profile as a benchmark. However, in England’s conflict-laden and decoupled intergovernmental system, there is also a clear institutional continuity, as evidenced from a comparative perspective by the concept of the “dual polity”, which has always characterized the politically-institutionally tense relationship between the central state and local authorities.

5. Polycrisis dynamics

This section analyses to what extent local governments’ responses to the pandemic have been entangled with other crises and their mitigation measures. Our focus is on understanding the interdependencies and overlaps of pandemic management with institutional measures responding to preceding or concurrent crises. Three types of crises (mitigation measures) entangled with pandemic governance emerged from our comparative observations: (a) fiscal crises and austerity policies resulting from New Public Management guided reforms, (b) migration-related crises posed by increasing migration and reception of refugees, pushed by the Russian war against the Ukraine, and (c) institutional and socio-political crises questioning the democratic quality or the position of local self-government in a country’s multilevel system.

The effects of preceding or other concurrent crises on the pandemic governance in the countries we studied were very differentiated. In only a few countries did migration-related crises or institutional and socio-political crises have an impact on the respective pandemic governance, yet the influence of fiscal crises triggered by NPM, leading to tensions in the healthcare sector is visible in all the countries studied (see Figure S2, Annex).

In Germany, the COVID-19 response was complicated by financial strains from past crises and recent increases in refugees, testing local governance capacities (Oehlert and Kuhlmann Citation2024). On the one hand, governance structures and mitigation strategies that had been established in local governments in response to the 2015/16 refugee challenge were partially reused, e.g. crisis task forces and plans (Pöhler et al. Citation2020). On the other hand, local health authorities suffered from the crisis mitigation responses to the fiscal crisis of 2008/09, when comprehensive cutback measures were taken, particularly in local health services, resulting in a lack of local health officers, staff shortage in hospitals, and poor IT equipment. These shortcomings are consequences of previous NPM-inspired “fatal remedies” taken to mitigate the fiscal crisis, which resulted in poor pandemic preparedness.

In France, preexisting fiscal strains on the health system and socio-political tensions were amplified by the pandemic, highlighting challenges in crisis preparedness (Bauquet Citation2020: 7). Thus, when the pandemic emerged, it was not merely a health crisis but also a magnifier of already virulent problems in public health and even societal tensions (Du Boys et al. Citation2020: 280f). Reform initiatives spearheaded by Presidents Hollande and Macron added another layer of complexity to France’s polycrisis dynamics. The NOTRe law 2015 curtailed the capabilities of subnational entities. Yet, the consequences of this law had not fully settled when COVID-19 arrived. Further complicating matters was Macron’s “Cahors pacts,” which abolished specific local expenditure increases (Interview 6). The reforms heightened persistent issues of insufficient cooperation between the central state and territorial governments, adversely affecting intergovernmental relations (Du Boys and Marius Bertolucci Citation2022). The French polycrisis dynamics intertwine centralized administrative heritage, socio-political disorders, and contemporary reforms, resulting in a unique mosaic of an extremely challenged crisis preparedness of the public sector.

Poland’s pandemic response was influenced by broader institutional challenges, reflecting tensions in governance and democratic practices. The democracy crisis became even more substantial during the pandemic, when the government took a rather authoritarian stance in containing the crisis by preventing local governments and citizens from legally opposing its measures. Pandemic governance has therefore contributed to further magnifying the democratic backsliding that had started with the PiS government’s ascent to power in 2015, and its subsequent centralizing endeavors and the politicization of the civil service. The polycrisis dynamic was further fueled by challenges prompted by the influx of more than one million Ukrainian war refugees since 2022. However, Polish local governments were successful in reusing crisis mitigation tools and governance structures already applied during the pandemic (like crisis task forces, management schemes, coordination mechanisms, and cooperation with civil society).

In Sweden, the high mortality rates in elderly homes at the beginning of the pandemic were also related to shortages in the care sector in terms of staff numbers, professionalism, and qualifications. Sweden’s care sector faced challenges exacerbated by past economic decisions and NPM reforms, impacting the pandemic response. Against this background, the deficits in pandemic governance (poor protection of the elderly) show an entanglement and interlinkage to previous crisis mitigation measures, particularly NPM-inspired outsourcing, cutback policies, privatization, and de-professionalization of the local welfare state. Despite Sweden’s financial resilience after the 2008/09 financial downturn, the pandemic’s complexities brought to the forefront public concerns about the state’s ability in crisis resilience and management. These concerns had also been fueled and intensified during the refugee crisis of 2015/16 which had left deep traces in Swedish administration and politics (see Oehlert and Kuhlmann Citation2024), resulting in decreasing institutional trust, disenchantment with politics, societal polarization, and political populism. The permissive pandemic governance, by contrast, was seen by some as partially counteracting (though not stopping) this trend, by way of safeguarding traditional values of Sweden’s political culture, keeping society open, and refraining from repressive measures.

England’s local governance faced intensified challenges amid Brexit and following fiscal austerity, affecting pandemic management. The fiscal strain only intensified as austerity measures were rolled out, culminating in a stark 26% reduction in local governmental financial resources between 2010/11 and 2020/21 (NAO, Citation2021: 16). The UK’s turbulent Brexit journey imposed another layer of complexity and led to an institutional crisis. This confluence of challenges set a context wherein the centralized pandemic response, pursued by London, often seemed to overshadow local governments and inadvertently deepen the regional disparities, revealing systemic vulnerabilities. The typical muddling-through approach, often intensified by prior solutions, mirrored the chaotic orchestration observed during the Brexit negotiations. Much of the management, especially in spring 2020, reflected an absence of structured consultations, a deviation from standardized procedures, and a pronounced top-down approach led by the Prime Minister. In essence, the UK’s polycrisis dynamics during the pandemic, interlaced with fiscal, political, and institutional challenges, underscore the essential need for harmonized central-local relations for effective crisis management.

6. Comparison and discussion

Regarding the institutional designs of crisis governance, a striking similarity across all scrutinized countries is the nonuse of constitutional emergency regulations during the pandemic, which formally existed in all countries of our sample (except in Sweden). The classic constitutional regulations (mostly defense cases and natural disasters) have not proved sufficient in times of polycrisis. Instead, governments preferred secondary legislation as the legal basis for pandemic management because it opened up a larger scope of executive flexibility. Furthermore, specific legal constructs to declare a pandemic emergency were introduced across the countries (Germany, France, and Poland), allowing for exceptional restrictions during critical periods.

Especially at the beginning of the pandemic, these regulations and orders were predominantly passed (e.g. in Germany and France) by the executive without parliamentary consultation. While in some countries (France, England, and Poland), the respective regulations were drafted, enacted, and executed primarily by central government actors with only supportive actions by sub-national bodies, in others (Germany and Sweden), the sub-national level was key in executing in administering crisis legislation. In Sweden and Germany, the central or federal government assumed only a consultative role in giving recommendations to sub-national governments, without the power of imposing restrictions on them. However, while in Germany all Länder passed legally binding “Corona orders” implemented by local governments, Sweden did without these types of binding regulations, thus leaving a high degree of discretion to local government (and citizens) in coping with the crisis.

Regarding our two key dimensions of task allocation (centralized/decentralized) and intergovernmental relations (coordinated/disjointed), our analysis has revealed a considerable degree of variation across the countries with some cases showing a decentralized pattern (Germany and Sweden), while others operated more centralized (France, England, and Poland). However, in some cases, the predominant institutional design changed over time, e.g. moving from a pronouncedly centralist to a more decentralized collaborative setting (as, for instance, in Poland) or from a rather disconnected toward a more coordinated pattern of intergovernmental relations (e.g. Sweden). In the German federal system, interestingly, we see ups and downs of centralization and decentralization throughout the pandemic with a centralizing overall tendency and increasing intensity of intergovernmental coordination. Finally, it is striking that in some cases (e.g. Poland and England) formal legal competencies in crisis management granted to local governments did not correspond to their actual activities. In the Polish case, local activities in crisis mitigation went beyond the competencies formally attributed to local governments. In England, by contrast, local governments were not enabled by the central government to execute the crisis management tasks legally allocated to them, as the sub-national levels were largely sidelined, despite their formal powers in crisis governance. In Germany and Sweden, finally, we observed a fairly well-fitting constellation of local governments’ formal and de facto competencies in pandemic management. We observed mismatches between formal legal competencies and actual activities of local governments, with some exceeding (e.g. Poland) and others not meeting their legally defined roles (England and France). summarizes our main findings about our dependent variable (institutional designs) from a country-comparative perspective, focusing on task allocation on the one hand and intergovernmental coordination on the other.

Figure 1. Institutional design variants of pandemic governance: task allocation and intergovernmental coordination.

Source: Own compilation.

Polycrisis dynamics across our sample reveal both commonalities and distinct differences. While the economic and financial crises led to fiscal challenges characterized by budgetary constraints in four of the studied countries, Poland was an exception, as its continued economic growth after the financial crisis alleviated budgetary pressures. All countries responded to the economic and fiscal crises by mitigation measures largely inspired by the NPM reform principles directed at privatization, outsourcing, delegation, and functional disaggregation, not least in the health and care sectors. These trends had serious impacts on crisis preparedness. Above all in France, where the public health sector already operated under a crisis mode before the pandemic, the cutback measures turned out to be “fatal remedies” to mitigate acute crises.

Besides the austerity-pandemic dynamics, our country analyses revealed a migration-pandemic dynamic stemming from managing the refugee crisis in parallel or subsequently to the pandemic crisis. In the final phase of the pandemic, the influx of refugees because of the Russian war against the Ukraine rose sharply for the first time since 2016 and once again became a challenge, especially for local governments. This type of entanglement applied in particular to Germany and Poland, where some local governments’ crisis taskforces were once again set up and other mitigation measures were re-used for multiple purposes related to pandemic and migration management. The pandemic-migration dynamic appeared to be less pertinent, however, in the UK, where the migration issue was less pressing, in Sweden, where the pandemic management was generally less interventionist, and in France, where local governments were functionally sidelined in the pandemic.

Finally, three cases of our sample were most affected by an entanglement of pandemic management and previous or ongoing institutional and societal crises. For one, this applies to Poland, where the authoritarian government tried to use the pandemic crisis to consolidate its power and further weaken democratic institutions. Furthermore, in the UK, a truly existential institutional crisis regarding its intergovernmental relations and the position of local governments has been increasingly hollowed out within a system of austerity localism and central government distrust toward local authorities (see Laffin and Diamond, Citation2023). Moreover, Brexit demonstrates that the deficits in intergovernmental relations and the personnel commitment of the public sector affected the British pandemic management. Especially in France, the pandemic interfered with a comprehensive social and political crisis, which started long before the pandemic and weakened the preparedness to this crisis. One expression of this crisis was the gilets jaunes movement, an influential country-wide opposition to pension reform and the health system restructuring plans. Furthermore, some presidential projects reformed intergovernmental relations, heavily restricting the competencies of local governments.

Our analysis revealed that institutional path-dependencies and administrative traditions significantly influenced pandemic responses, highlighting variations in crisis governance. Some temporal centralizing tendencies during the crisis notwithstanding, Germany’s institutional design of crisis governance followed the historical path of decentralized task allocation, local discretion, and administrative federalism/localism. Furthermore, drawing on the tradition of cooperative federalism and highly entangled inter-administrative relations, crisis governance was marked by intense collaboration across jurisdictions and levels of government contributing to mitigating conflicts and tensions in the intergovernmental setting. Crisis governance in France reflects the traditionally centralized character of Napoleonic-style political and administrative systems within which local governments hardly play a role. Looking at Sweden, the unique institutional imprints of a distinctly decentralized welfare state granting a key role to local authorities in managing crises is a clear reflection of the historically ingrained Nordic administrative profile.

Yet, from an historic-institutionalist perspective it is striking that there were also some deviations from established institutional paths, as particularly evident in the cases of Poland (involvement of local governments) and England (centralist intervention). Additionally, the example of France demonstrated that institutional reforms undertaken in the meantime, particularly the decades of effort to strengthen local governments by way of decentralization, seemed to have been completely overlooked during the pandemic. Instead, old patterns of Jacobin-Napoleonic state intervention and centralistic control resurfaced, some of which had been thought to be long overcome. At the same time, this disregard for achieved administrative decentralization successes (as seen in France), as well as the general ignorance toward local authorities during crises (as observed in Poland and England), led to intense conflicts within the multi-level system, prompting efforts for increased consultation and coordination (Poland).

7. Conclusions and limitations

Our analysis has shown a huge variance in institutional designs shaped by country-specific administrative cultures and profiles. The degree of de-/centralization and the intensity of coordination or decoupling across levels of government show significant country differences. The administrative cultures of the countries under scrutiny had a strong impact on the institutional design chosen for mitigating the pandemic. Centralized administrative systems (France and England) tended to adopt a top-down approach in pandemic governance, limiting local flexibility. By contrast, decentralized administrative systems (Germany and Sweden) have been revealed as being more prone to differential crisis responses and bottom-up activities. They have also been less affected by an entanglement of pandemic governance and synchronous institutional crises. Poland with its decentralized unitary state, is closer to the latter, except for a democratic crisis initialized by the rise of the PiS regime.

However, the functional strength and capacities of local governments do not explain a country’s crisis governance design. Even in those cases where local governments possessed enough capacities and discretion to fulfill crisis-related tasks in the intergovernmental setting, central governments did not always trust them and refrained from involving local governments in crisis management (UK, Poland, and partly France). In Germany, by contrast, which started with a high degree of decentralization and coordination in the intergovernmental setting, saw an overall centralizing tendency. Thus, the role of local governments in crisis governance does not exclusively depend on their legally defined competencies, but on their actual – often pragmatic, locally tailor-made and differential - interventions in mitigating a crisis.

Our findings underscore the interconnectedness of various crises and their broad impacts on local crisis management in the studied countries. Previous policy failures have, in some cases, diminished the resilience of local institutions, affecting their readiness for current and future crises. Conversely, successful solutions from past crises serve as valuable starting points for addressing subsequent ones. Despite challenges, there are instances of learning from past crises, enabling more agile and effective responses from public authorities in new crises. Thus, on the one hand, there is evidence of a positive relationship between previous and subsequent crisis responses. On the other hand, crisis entanglement has also become visible in the negative long-term impacts of mitigation measures taken by governments in response to previous crises. For instance, neoliberal reforms, cutback policies, and NPM measures initiated by many governments as responses to previous economic and fiscal crises significantly impaired pandemic preparedness, particularly regarding the health and care sectors (Germany, Sweden, England). The pandemic also intensified ongoing socio-political and institutional crises, as evidenced in France (gilets jaunes movement) and Poland (democratic backsliding), while in the UK, Brexit added considerable strain to crisis governance during the pandemic.

The pandemic has revealed several problems in administrative action at national, regional, and local levels that need to be overcome. Despite significant variations in pandemic crisis management across the countries we analyzed, some general recommendations for practitioners and policymakers can be identified. First, the new polycrisis situation necessitates the consideration of an increased number of crises, disasters, and transformations in strategic crisis management planning, moving toward all-hazard management. In this context, enhancing internal administrative cooperation is crucial. Additionally, there is a need for a more robust data foundation and more tailored preparations for crises to meet the challenges posed by the polycrisis. Second, our analysis revealed that in all countries studied, there were significant issues with the coordination and collaboration on specific actions during the pandemic across different administrative levels and from a cross-departmental perspective. Future polycrisis management should therefore also include the improvement of communication structures between public actors. Notably, our analysis underscores the critical role of local government associations in facilitating cooperation and coordination, particularly with central authorities. These organizations have proven instrumental in bridging gaps between various administrative levels and require more attention to bolster their effectiveness in future crises.

Our analysis has provided the first empirical insights into local polycrises governance, institutional design variants, and explanatory factors. However, a major limitation of our study is that we were only able to identify a potential explanatory link between administrative cultures and institutional designs of crisis governance. A precise empirical verification of this, based on a larger number of cases, could be explored in future studies. In addition, a limitation to our causal model of administrative cultures and historical path dependencies as decisive explanatory factors is that other potential explanatory factors are not taken into account. This is another area where further research is needed. Furthermore, there is a research gap regarding the effectiveness and impacts of different polycrises governance systems. This is of particular importance, as institutional reactions to other types of intertwined crises, such as climate change, cyberattacks, wars, and their effects will become increasingly salient in future polycrises governance.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (67.5 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In our study, we concentrate on England, leaving all other parts of the UK aside, as the process of devolution differs.

References

- Andersson, Staffan, and Nicholas Aylott. 2023. “An Exceptional Case: Sweden and the Pandem-ic.” In The Political Economy of Global Responses to COVID-19, edited by Alan W. Cafruny and Leila Simona Talani, 75–101. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-23914-4_5.

- Ansell, Christopher, Eva Sørensen, and Jacob Torfing. 2021. “The COVID-19 Pandemic as a Game Changer for Public Administration and Leadership? The Need for Robust Governance Responses to Turbulent Problems.” Public Management Review 23 (7): 949–960. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1820272.

- Ansell, Christopher, Eva Sørensen, and Jacob Torfing. 2022. “Public Administration and Politics Meet Turbulence: The Search for Robust Governance Responses.” Public Administration 101 (1): 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12874.

- Askim, Jostein, and Tomas Bergström. 2022. “Between Lockdown and Calm down. Comparing the COVID-19 Responses of Norway and Sweden.” Local Government Studies 48 (2): 291–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2021.1964477.

- Bauer, Michael W., Jana Otto, and Rahel Schomaker. 2022. “Kriseninternes Lernen “Und „Krisenübergreifendes Lernen “in Der Deutschen Kommunalverwaltung.” Zeitschrift Für Politikwissenschaft 32 (4): 787–804. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41358-022-00323-5.

- Bauquet, Nicolas. 2020. “L’action publique face à la crise du Covid-19.” Institut Montaigne. https://www.institutmontaigne.org/publications/laction-publique-face-la-crise-du-covid-19.

- Benamouzig, Daniel. 2023. France: From Centralization to Defiance, 359–369. Springer eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14145-4_30.

- Bengtsson, Rikard, and Douglas Brommesson. 2022. “Institutional Trust and Emergency Preparedness: Perceptions of Covid 19 Crisis Management in Sweden.” Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 30 (4): 481–491. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12391.

- Boin, Arjen, Paul ‘t Hart, Eric Stern, and Bengt Sundelius. 2016. The Politics of Crisis Management. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316339756.

- Broadhurst, Kate, and N. F. Gray. 2022. “Understanding Resilient Places: Multi-Level Governance in Times of Crisis.” Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit 37 (1–2): 84–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/02690942221100101.

- Christensen, Tom., Ole Andreas Danielsen, Per Lægreid, and Lise H. Rykkja. 2016. “Comparing Coordination Structures for Crisis Management in Six Countries.” Public Administration 94 (2): 316–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12186.

- Diamond, Patrick, and Martin Laffin. 2022. “The United Kingdom and the Pandemic: Problems of Central Control and Coordination.” Local Government Studies 48 (2): 211–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2021.1997744.

- Du Boys, Céline, and Marius Bertolucci. 2022. “Gouvernance Multi-Niveaux de La Crise de La Covid-19 En France, Quels Échecs et Réussites?” Gestion et Management Public 9N° 4 (4): 49–55. https://doi.org/10.3917/gmp.094.0049.

- Du Boys, Céline, Marius Bertolucci, and Robert Fouchet. 2022. “French Inter-Governmental Relations during the Covid-19 Crisis: Between Hyper-Centralism and Local Horizontal Cooperation.” Local Government Studies 48 (2): 251–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2021.1958786.

- Du Boys, Céline, Jean-Michel Eymeri-Douzans, Christophe Alaux, and Khaled Sabouné. 2020. “France and COVID-19: A Centralized and Bureaucratic Crisis Management vs Reactive Local Institutions.” HAL (Le Centre Pour La Communication Scientifique Directe). https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03541455.

- Gawłowski, Robert. 2022. “Intergovernmental Relations during the COVID-19 Crisis in Poland.” Institutiones Administrationis 2 (2): 88–98. https://doi.org/10.54201/iajas.v2i2.32.

- Graf, Franziska, Alexa Lenz, and Steffen Eckhard. 2023. “Ready, Set, Crisis – Transitioning to Crisis Mode in Local Public Administration.” Public Management Review 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2023.2242851.

- Hassenteufel, Patrick. 2020. “Handling the COVID-19 Crisis in France: Paradoxes of a Centralized State-Led Health System.” European Policy Analysis 6 (2): 170–179. https://doi.org/10.1002/epa2.1104.

- Hegele, Yvonne, and Johanna Schnabel. 2021. “Federalism and the Management of the COVID-19 Crisis: Centralisation, Decentralisation and (Non-)Coordination.” West European Politics 44 (5–6): 1052–1076. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1873529.

- Henig, David, and Daniel M. Knight. 2023. “Polycrisis: Prompts for an Emerging Worldview.” Anthropology Today 39 (2): 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8322.12793.

- Jaraczewski, Jakub. 2021. “An Emergency by Any Other Name? Measures against the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland.” Verfassungsblog. https://doi.org/10.17176/20200424-165029-0.

- Joyce, Paul. 2020. “Public Governance, Agility and Pandemics: A Case Study of the UK Response to COVID-19.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 87 (3): 536–555. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852320983406.

- Kersten, Jens, and Stephan Rixen. 2020. Der Verfassungsstaat in Der Corona-Krise. München: C.H. Beck.

- King, Jeff, and Byrom Natalie. 2021. “United Kingdom: Legal Response to Covid-19.” The Oxford Compendium of National Legal Responses to Covid-19, edited by Jeff King and Octavio Ferraz. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/law-occ19/e17.013.17.

- Kuhlmann, Sabine, Benoît Paul Dumas, and Moritz Heuberger. 2022. The Capacity of Local Governments in Europe. Springer eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-07962-7.

- Kuhlmann, Sabine, and Hellmut Wollmann. 2019. Introduction to Comparative Public Administration: Administrative Systems and Reforms in Europe. 2nd ed. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Kuhlmann, Sabine, and Jochen Franzke. 2022. “Multi-Level Responses to COVID-19: Crisis Coordination in Germany from an Intergovernmental Perspective.” Local Government Studies 48 (2): 312–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2021.1904398.

- Kuhlmann, Sabine, Jochen Franzke, Benoît Paul Dumas, and Moritz Heuberger. 2023. Regierungs- Und Verwaltungshandeln in Der Coronakrise: Fallstudie Deutschland. Potsdam, Germany: Universitätsverlag Potsdam.

- Kuhlmann, Sabine, Mikael Hellström, Ulf Ramberg, and Renate Reiter. 2021. “Tracing Divergence in Crisis Governance: Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic in France, Germany and Sweden Compared.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 87 (3): 556–575. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852320979359.

- Laffin, Martin, and Patrick Diamond. 2023. “Intergovernmental Relations in the UK and England: Crisis and Policy Stasis.” New Perspectives on Inter-Governmental Relations: Crisis and Reform, edited by Sabine Kuhlmann, Martin Laffin, Ellen Wayenberg, and Tomas Bergström. London: Palgrave Macmillan (Forthcoming).

- Lipiński, Artur. 2021. Poland: ‘If We Don’t Elect the President, the Country Will Plunge into Chaos, 115–129. Springer eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66011-6_9.

- Makowski, Grzegorz. 2023. “Analyse: Der Staat Unter Der Regierung Von Recht Und Gerechtigkeit – Ein Staat Des Zentralismus, Etatismus Und Der "Grand Corruption.” Polen-Analysen Nr (311): 2–9. https://doi.org/10.31205/PA.311.01.

- Martin, Ciaran, Hester Kan, and Maximillian Fink. 2023. “Crisis Preparation in the Age of Long Emergencies. A Summary.” Blavatnik School of Government. https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/crisis-preparation-age-long-emergencies-summary.

- Mattsson Titti, Ana Nordberg, and Martina Axmin. 2021. “Sweden: Legal Response to Covid-19.” The Oxford Compendium of National Legal Responses to Covid-19. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/law-occ19/e12.013.12.

- Mayring, Philipp. 2015. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken. Weinheim: Beltz.

- National Audit Office (NAO). 2021. “Local Government Finance in the Pandemic. Report.” https://www.nao.org.uk/reports/local-government-finance-in-the-pandemic/.

- OECD. 2020. “The Territorial Impact of COVID-19: Managing the Crisis across Levels of Government.” OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (Covid-19). Paris, France: OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/d3e314e1-en.

- Oehlert, Franziska, and Sabine Kuhlmann. 2024. “Inter-Administrative Relations in Migrant Integration: Germany, Sweden, and France Compared.” In New Perspectives on Intergovernmental Relations: Crisis and Response, edited by Sabine Kuhlmann, Martin Laffin, Ellen Wayenberg, and Tomas Bergström. London: Palgrave Macmillan (Forthcoming).

- Olofsson, Tobias, Shai Mulinari, Maria Hedlund, Åsa Knaggård, and Andreas Vilhelmsson. 2022. “The Making of a Swedish Strategy: How Organizational Culture Shaped the Public Health Agency’s Pandemic Response.” SSM. Qualitative Research in Health 2: 100082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100082.

- Peters, B. Guy. 2011. Institutional Theory in Political Science: The New Institutionalism. 3rd ed. London: Continuum.

- Petridou, Evangelia. 2020. “Politics and Administration in Times of Crisis: Explaining the Swedish Response to the COVID-19 Crisis.” European Policy Analysis 6 (2): 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/epa2.1095.

- Pöhler, Jana, Michael W. Bauer, Rahel M. Schomaker, and Veronika Ruf. 2020. “Kommunen und COVID-19: Ergebnisse einer Befragung von Mitarbeiter*innen deutscher Kommunalverwaltungen im April 2020.” In WITI-Berichte Speyerer Arbeitshefte Nr. 239. Speyer: WITI - Wissens- und Ideentransfer für Innovation in der öffentlichen Verwaltung.

- Sienkiewicz, Mariusz, and Katarzyna Kuć-Czajkowska. 2022. “The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Local Government Units in Poland.” In Local Government and the COVID-19 Pandemic. A Global Perspective, edited by C. Nunes Silva, 429–450. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Steinmo, Sven, Kathleen Thelen, and Frank Longstreth. 1992. Structuring Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511528125.

- ‘t Hart, Paul, and Arjen Boin. 2001. “Between Crisis and Normalcy: The Long Shadow of Post-Crisis Politics.” In Managing Crises: Threats, Dilemmas, Opportunities, edited by Uriel Rosenthal, Arjen Boin, and Louise Comfort, 28–46. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

- Thomas, Alex, and Rhys Clyne. 2021. “Responding to Shocks: 10 Lessons for Government.” Institute for Government. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/responding_shocks_lessons_covid_brexit.pdf

- Vampa, Davide. 2021. “COVID-19 and Territorial Policy Dynamics in Western Europe: Comparing France, Spain, Italy, Germany, and the United Kingdom.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 51 (4): 601–626. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjab017.

- Waldhoff, Christian. 2021. “Der Bundesstaat in der Pandemie.” Neue Juristische Wochen-schrift 38: 2772–2777.

- Weinheimer, Hans-Peter. 2022. “Die Corona-Pandemie und die föderale Kompetenzor-dnung.” In Politik zwischen Macht und Ohnmacht: Studien zur Inneren Sicherheit, edited by Hans-Jürgen Lange. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-35393-3_6.

- Winblad, Ulrika, Anna-Karin Swenning, and Douglas Spangler. 2021. “Soft Law and Individual Responsibility: A Review of the Swedish Policy Response to COVID-19.” Health Economics, Policy, and Law 17 (1): 48–61. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1744133121000256.

- Wollmann, Hellmut. 2003. “Evaluation in Public-Sector Reform. Cheltenham and Northampton.” In Evaluation in Public Sector Reform: Towards a ‘Third Wave’ of Evaluation, edited by Hellmut Wollmann, 1–11. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.